Abstract

With the fast development of the 5G technology and IoV, a vehicle has become a smart device with communication, computing, and storage capabilities. However, the limited on-board storage and computing resources often cause large latency for task processing and result in degradation of system QoS as well as user QoE. In the meantime, to build the environmentally harmonious transportation system and green city, the energy consumption of data processing has become a new concern in vehicles. Moreover, due to the fast movement of IoV, traditional GSI-based methods face the dilemma of information uncertainty and are no longer applicable. To address these challenges, we propose a T2VC model. To deal with information uncertainty and dynamic offloading due to the mobility of vehicles, we propose a MAB-based QEVA-UCB solution to minimize the system cost expressed as the sum of weighted latency and power consumption. QEVA-UCB takes into account several related factors such as the task property, task arrival queue, offloading decision as well as the vehicle mobility, and selects the optimal location for offloading tasks to minimize the system cost with latency energy awareness and conflict awareness. Extensive simulations verify that, compared with other benchmark methods, our approach can learn and make the task offloading decision faster and more accurately for both latency-sensitive and energy-sensitive vehicle users. Moreover, it has superior performance in terms of system cost and learning regret.

Keywords:

multi-tier vehicular computing; cost minimization; queue of energy volatility-awareness; reinforcement learning; MAB MSC:

94A05

1. Introduction

With the fast development of 5G technology [1,2] and IoV [3], the vehicle has become a smart device with communication, computing, and storage capabilities. However, the limited on-board storage and computing resources often cause large latency for local task processing and result in degradation of system QoS as well as user QoE, which can hardly satisfy the latency-sensitive and computation-intensive demands of VUs for real-time application like online entertainment. To this end, VUs may offload tasks for MCC or MEC that provide service and cloud computing capabilities at the edge of the mobile network to relieve their own computational burden [4]. However, the edge server such as the BS needs to serve a huge number of mobile users simultaneously and cannot always provide timely response to VUs. Using RSUs to replace BSs is a feasible solution, but the implementation of massive arrangement of RSUs is costly. For example, installing RSU in only one US city costs about USD 18.63 billion, and the annual maintenance cost is approximately USD 1.1 billion [5,6]. Papers [7,8] propose to use PCRSUs, making it an alternative to RSUs. Moreover, driving vehicles around the VU with a similar trajectory may share idle computing and storage resources, forming the VCEC [9,10]. As a result, MTVC via BS, PCRSU, CDV, and VU local computing is emerging as a new paradigm for latency-sensitive and computation-intensive task processing in IoV. Notably, CDVs can provide idle computing resources by sharing redundant capabilities of vehicles with similar trajectories, while ESs ensure reliable queue length broadcasting through periodic feedback and channel verification to support accurate offloading decisions.

In the meantime, to build the environmentally harmonious transportation system and green city, the energy consumption of vehicle has become a great concern. Since task offloading may both save energy for VU and satisfy latency-sensitive as well as computation-intensive demands, how to strategically select the task processing location is a key issue. Note that the ES candidates for task offloading in IoV change over time due to the movement of both VU and VCEC edge servers. Thus, the GSI such as CSI and available server resource is uncertain for VU, resulting in traditional GSI-based offloading methods that are no longer applicable. Additionally, there is a pressing need for research into the problem of task conflict resolution in MTVC systems. Fortunately, a learning-based approach can be leveraged to give the solution [11].

To tackle the aforementioned challenges, in this paper we propose a T2VC model for IoV to minimize the system cost denoted by the sum weighted latency and power consumption. Due to the information uncertainty and dynamic offloading issues, a MAB-based QEVA-UCB solution for jointly optimizing system latency and energy consumption is proposed. QEVA-UCB takes into account several related factors, such as the task property, task arrival queue, offloading decision as well as the vehicle mobility, and selects the optimal location for offloading tasks to minimize the system cost with latency energy awareness and conflict awareness.

The contributions of this paper are as summarized as follows:

- We first propose the T2VC model for IoV, which systematically integrates three-tier edge servers (BS, CDV, PCRSU) and VU local computing. This comprehensive integration is rarely fully considered in existing MAB-based offloading frameworks. Arriving tasks are cached in a FIFO queue, and we formulate the problem of minimizing weighted latency and power consumption. The model targets the high-dynamic and CSI information uncertainty in IoV, where traditional GSI-based methods fail.

- We propose the QEVA-UCB solution based on MAB reinforcement learning. Unlike existing MAB-based offloading approaches, it integrates queue state awareness and energy volatility perception. It also comprehensively incorporates vehicle mobility and task offloading conflicts. We use Lyapunov optimization [12,13,14] to decouple long-term energy constraints and short-term decision making—a key consideration ignored by most existing MAB methods. Theoretical analysis verifies that QEVA-UCB has an upper bound for system cost.

- Extensive simulations are conducted to compare the proposed strategy with the naive UCB method, MV-UCB method, the ALTO method, and the optimal method. Results demonstrate that our approach can learn and make the task offloading decision faster and more accurately for both latency-sensitive and energy-sensitive VUs. Moreover, it has superior performance in terms of system cost and learning regret.

The rest of this paper is organized in such a manner. Section 2 presents related works. Section 3 introduces the system model of T2VC. Section 4 presents the task offloading problem and the constraints. QEVA-UCB algorithm and simulation results are given in Section 5 and Section 6. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

The literature on vehicular networks is vast. In paper [15], Liu et al. chose the single-layer MEC to offload tasks to edge nodes. Tang et al. of paper [16] considered offloading tasks to RSUs deployed on roadside, which could reduce task completion latency to a large extent. With the development of on-board storage and computing capability, vehicles can possess spare resources to help surrounding neighbors in a V2V manner. In paper [9], Hou et al. stated that vehicles travelling in the same direction could provide service to each other. Furthermore, in paper [17], Jiang et al. proposed a two-layer IoV model, considering that VUs might offload tasks to the BS or to the surrounding CDV. In paper [18], Tang et al. applied both RSU and travelling vehicles to act as edge servers and proposed a greedy heuristic based scheduling strategy to perform the tasks among vehicular fog computing. Additionally, in paper [19], Braga Reis et al. proposed the use of parked vehicles to gradually replace costly RSUs for passing VUs. However, none of the aforementioned works systematically consider all possible edge server candidates, i.e., BS, CDV, and PCRSU, which are included in our proposed T2VC model.

Many works have focused on task offloading and resource allocation in wireless communication system. In paper [20], Liu et al. respectively designed three algorithms based on heuristic search, reconstruction linearization and semi-definite relaxation to solve the problem of edge nodes selection, offloading sorting and task allocation for the URLLC MEC system. It realized the balance between latency and complexity. In paper [21], X. Hou et al. proposed the concept of EC-SDIoV to better utilize heterogeneous edge computing resources in variable IoV environments and to meet system latency constraints while ensuring reliability. In paper [22], Bute et al. proposed a distributed task offloading scheme that selected nearby vehicles with free computing resource to process tasks in a parallel manner. The proposed scheme could achieve good performance in terms of latency. In paper [23], Cai et al. studied the task offloading in fog-enabled internet of things networks, where Lyapunov optimization was leveraged to get the optimal results. In paper [24] Eltoweissy et al. designed two greedy heuristic methods to optimize the average response time while satisfying the long-term energy constraint. In paper [25], Tout et al. studied a cost-effective MEC-based method for offloading decision making to minimize processing/memory resource as well as energy. However, the above works mainly utilize traditional optimization methods to solve the task offloading problem while ignoring the high-dynamic characteristics of IoV. Due to the continuous changes in network status and information uncertainty, it is difficult to obtain an optimal solution.

The UCB reinforcement learning method is able to obtain fast convergence for offloading decision making under information uncertainty [26,27,28], which is especially suitable for IoV systems. In paper [29], Zhu et al. adopted the MAB to minimize computational latency for fog-enabled networks. And in paper [30], Sun et al. proposed a MAB-based task offloading strategy to optimize the vehicular cloud computing system latency. In paper [31], Gao et al. designed a learning-assisted green offloading method using the MAB approach to ensure that system energy consumption was within a bound. However, the aforementioned works ignore the long-term queue delay constraint, resulting in unrealistic practical execution. In paper [32], Qin et al. utilized vehicle association to reduce the overall energy consumption of IoV with long term constraint awareness. However, the objective is only to minimize the power consumption. Moreover, the offloading architecture did not take the multi-tier vehicular computing into consideration and was not comprehensive.

3. System Model

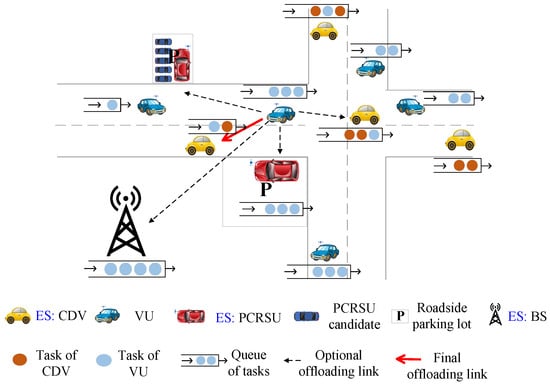

We consider a T2VC model for IoV in an urban scenario. As shown in Figure 1, there are three types of edge server, i.e., one BS server , multiple CDV servers and PCRSU servers , denoted by the set . F CDV server vehicles within the communication range of VU V are denoted by . P PCRSU server cars are represented by . Each task of VU can be either processed locally or offloaded to the surrounding ESs (In this paper, the VU sends task request to neighbor ESs when its resource is unable to complete the task processing, in which case it lacks resource to serve other vehicles and will reject service requests from others.). Arriving tasks in the system are cached in a FIFO queue.

Figure 1.

System model.

We use a time-slot model, where T discrete slots make up the overall time period, represented by . In each slot, the VU determines whether a task is offloaded to at most one ES. Thus, task splitting offloading to more than one ES is out of the scope of this paper. Assume there are totally periods with starting time as well as ending time , during which the available ES candidates for task offloading in the T2VC system remain unchanged. Then, the duration of each period can be expressed as .

There are four types of locations for task processing: (1) local execution, (2) offloading to a CDV server , (3) offloading to a PCRSU , (4) offloading to the nearby BS , which can be represented by :

Thus, task offloading decision of the VU can be expressed as follows:

where k indicates the offloading type, and denotes the specific location under this type. For example, means that V offloads the task to the 8th CDV server in slot t. represents local processing and corresponding setting .

3.1. Latency Model

We consider three types of latency in T2VC, namely, task transmission latency, queuing latency and processing latency. Transmission latency is the time interval of task transmission from VU to ES, queuing latency is the task waiting time in the VU/ES queue, and processing latency is the task processing time at the server side. For local processing tasks, system latency consists of queuing time and local processing time, while, for offloading tasks, it includes all the three.

In the tth slot, the allocated CPU frequency to the task of VU is denoted by , where the computational capacity of the VU is , while the computational capacity of the other three ESs are expressed as , and , respectively. Assume each task has different input data size, and the ratio of output data to input data is the same [29]. Thus, let (We set as a fixed value to simplify the analysis of offloading latency and energy consumption. Heterogeneous vehicular applications can be adapted by adjusting , which does not affect the algorithm’s core logic). Define the computational latency as follows:

where is a binary variable; i.e., if the task is processed locally; otherwise, . is the calculation intensity in CPU cycles per bit, indicating the CPU cycles required to calculate one bit of input data. and are the computational resource available in slot t at the VU and ES side, respectively.

The channel gain can be calculated by , where is the attenuation factor, and l is the distance between ES and VU [33]. Thus, the uplink task transmission latency is expressed as follows:

where is the bandwidth for uplink transmission from VU to ES in time slot t, denotes the transmission power, is the channel gain for uplink transmission from VU to ES in time slot t and represents the noise power. Since value of k in is different, the transmission latency might be CDV latency , PCRSU latency , or BS latency .

Similarly, assume that the size of the downlink output data is . The downlink transmission latency is expressed as follows:

where is the bandwidth for downlink transmission from ES to VU in time slot t, is the transmission power, and is the channel gain. The downlink transmission latency might also be divided into three categories.

Let and , respectively, denote the queue length of the ES and VU in time slot t, which is broadcasted by ES at the beginning of each time slot [30]. Then the corresponding queuing latency can be expressed as follows:

where is the time required to wait for 1 bit data in the processing queue.

Therefore, the total latency of a task for VU in time slot t can be expressed as follows:

In practice, VU does not know the edge server’s real-time remaining computing resource information. Moreover, since vehicles are moving over time, system CSI is also unavailable and changes rapidly.

3.2. Energy Consumption Model

If processing locally, only the computing energy consumption of the VU is considered. If task is offloaded, the system energy consumption comes mainly from the transmission power of VU and the computing power at the ES side.

For local processing, the energy consumption in time slot t can be expressed as follows:

where represents the power consumption per CPU cycle.

For task offloading, the energy consumption can be expressed as follows:

where denotes the power consumption per CPU cycle of ES s, and denotes the energy for VU to transmit 1-bit data to ES s.

Thus, the total energy consumption in slot t can be expressed as follows:

Therefore, the system cost can be expressed as follows:

where is the transmission latency weight.

4. Problem Formulation and Decomposition

In this paper, the objective function is to minimize the sum weighted latency and power consumption of the T2VC system, constrained by the long-term average energy budget, which can be expressed as follows:

where (12b) denotes that the upper bound of the longer-term average system energy consumption can not exceed the maximum constraint. (12c) and (12d) are VU’s QoS requirements. (12e), (12f), and (12g) indicate that tasks can be processed locally or offloaded to at most one ES.

5. QEVA-UCB Solution for T2VC Task Offloading and Resource Optimization

5.1. Energy Budget Based on Virtual Queue Technology

For the offloading decision process, the long-term time-averaged energy consumption constraint in Equation (12b) is coupled with short-term offloading decision making, making P1 challenging to solve. Thus, in this subsection, a virtual queue is introduced to transform (12b) into the stability constraint of the virtual queue, which is applied to address the vehicle energy constraint.

The virtual queue is updated as follows:

where .

According to the study of [31], if the stability of the queue is guaranteed, the energy consumption constraint can be satisfied. Then, Lyapunov optimization can be leveraged and Lyapunov function is expressed as the half of the sum of squares of :

where is the vector of all virtual queue backlog in time slot t.

Define the corresponding Lyapunov drift as follows:

the size of indicates the variation in the queue between two nearby time slots.

Redefine the system cost function as follows:

where is an adjustable positive parameter.

On the basis of the study of [13,14], if , the queue will become larger, and the cost of selecting it as ES becomes higher. Therefore, it will no longer be selected for offloading afterwards. Furthermore, if is smaller than other virtual queues, then VU prefers to process the task locally to reduce the energy consumption.

5.2. QEVA-UCB Algorithm

To tackle problem (16), we propose the QEVA-UCB algorithm for jointly optimizing system latency and energy consumption.

It can be seen from Equation (9) that the energy consumption of the system is determined by and the offloading location. Once the task-related parameter, for example, the size of input data, is determined, the task latency for different offloading decision can be calculated, then the system energy consumption is also determined, accordingly. Therefore, in this paper, we mainly focus on the learning to obtain the minimal system latency. The principle of the QEVA-UCB algorithm is shown below.

Firstly, VU connects with the newly joining ES for task offloading, and let [30]. Then, the transmission latency is updated based on its local information as follows:

where is the average latency in previous time slots, and the second term is the one-sided confidence interval. The latency estimation in (17) deviates from standard UCB to adapt to IoV’s dynamic nature. Its design strictly follows UCB’s exploration–exploitation framework. is the exploration preference, which is a constant. is the normalized distance between ES and VU (IoV task offloading latency is inherently dependent on transmission distance. Integrating normalized distance into the exploration term scales the exploration intensity based on transmission overhead, which is consistent with UCB’s goal of balancing performance stability and exploration efficiency). is the distance weight factor; it quantifies how ES-VU distance influences the algorithm’s candidate selection. Adjusting helps the algorithm prioritize ESs with more suitable distances. A smaller will increase the algorithm’s emphasis on distance, therefore choosing the ES with shorter distance. is the normalized input data size. is the normalized computational intensity ( and follow UCB’s reward-scaling principle. They unify the units of task-related variables, avoiding exploration bias caused by large differences in data size or computation intensity between heterogeneous tasks. This design is derived from the task-aware optimization logic of UCB variants, which is essential for adapting UCB to edge computing scenarios with diverse tasks). indicates the time slot when the ES first appears, which guarantees the volatility-awareness of our solution. is the number of times the location L is selected for task processing before the time slot t.

VU always offloads tasks to location L with the minimum system cost, which is calculated by the following:

The above process is summarized in Algorithm 1. It learns and selects the location with the lowest system cost for task offloading.

Algorithm 1 consists of two phases: the learning phase and the decision-making phase. In the learning phase, the computational intensity and exploration preference are first initialized (Line 5). If a new ES enters the VU’s communication range, VU will offload its task to the new ES at least once to obtain the corresponding system latency (Line 6–9). In the offloading decision-making phase stage, VU updates the system latency of each time slot according to the previous learning results (Line 11) and calculates the energy consumption for each offloading position (Line 12). Then, VU calculates according to Equation (16) (line 13) and selects the optimal location with the lowest cost for task offloading (Line 14). Lastly, VU updates , according to Equations (18) and (19) (line 15).

where is a vector of all virtual queueing backlogs in time slot t. . is a positive constant satisfying such that is also in the feasible domain.

| Algorithm 1 QEVA-UCB Algorithm |

|

Theorem 1.

For each vehicle and edge server, the average energy should be less than its maximum energy limit included in vector indicating that the QEVA-UCB algorithm satisfies the time average energy constraint (12b). Then, the following results can be obtained:

The proofs are given in Appendix A. For the proposed QEVA-UCB algorithm, the learning regret is defined as the expected cost gap between the learned strategy and the optimal strategy, calculated by the following:

Theorem 2.

Algorithm 1 has the upper bounded learning regret of

Proof of Theorem 2.

Details are given in Appendix B. □

5.3. Complexity and Convergence

In this paper, the complexity of our proposed QEVA-UCB algorithm can be calculated as follows. In Line 6 the computational complexity of calculating the latency function of all ES candidates is , where the number of ES candidate in time slot t is N. The complexity of updating the offloading number is . The computational complexity of calculating the energy consumption of all ES candidates in Line 12 is , and the task offloading decision made in Line 14 is a minimum-seeking problem, with a complexity of . The complexity of updating the empirical bit offloading latency is . Therefore, the total computational complexity of running QEVA-UCB to offload one task is . Assume that there are totally M tasks required to be offloaded in the T2VC system. Since VU offloads the tasks independently, the total complexity is for each slot. From Theorem 2, we can see that there is an upper bound to the learning regret of the QEVA-UCB algorithm, and it will eventually converge to the optimal value through learning.

6. Simulation Results

For the simulation part, there are T = 2000 time slots, divided equally into four periods, each of which consists of 500 slots. The system consists of one VU, three CDVs, two PCRSUs and one BS. The distance weight = 1 [34]. All results are averaged over 10 independent runs to account for randomness from task arrival, channel conditions, and ES mobility. We consider two types of VU, i.e., latency-sensitive VU and energy-efficient VU, respectively. The former prioritizes task completion timeliness, so we set to make latency the dominant factor in system cost. The latter focuses on minimizing energy consumption, so is adopted to emphasize energy efficiency. The adjustable parameter , which is appropriate here as it balances the trade-off between system cost and long-term energy constraints under the specific simulation parameters including energy budget, task properties and ES characteristics. The exploration preference is chosen to balance exploration of new ES candidates and exploitation of known optimal locations, adapting to the dynamic IoV environment. During every time slot t, is the power consumption per CPU cycle, which is sampled from distribution Unif J/cycle. is the power consumption per CPU cycle of ES, which is sampled from distribution Unif J/cycle. is the energy for VU to transmit 1-bit data to ES, which is sampled from distribution Unif ( J/bit. The energy budget is set as = 200 J [31]. Other parameters are shown in Table 1. Note that we adopt simulations instead of physical experiments to verify the proposed method, as simulations allow precise control of dynamic variables and fair algorithm comparisons, which are more practical for validating theoretical models in multi-tier vehicular computing. Physical experiments would involve high costs for deploying real-world ESs and VUs, and it is challenging to stably replicate the dynamic IoV environment.

Table 1.

Primary simulation parameters.

The QEVA-UCB approach is compared to the following six methods.

- 1.

- UCB method [35]: Traditional/naive upper confidence bound method.

- 2.

- R-UCB method: Range-awareness is added to the traditional UCB algorithm.

- 3.

- MV-UCB method [34]: ES occurrence-awareness is added to the traditional UCB algorithm.

- 4.

- ALTO method [30]: Task load-awareness and ES occurrence-awareness are enhanced to the traditional UCB algorithm.

- 5.

- TR-UCB method: Task load-awareness and range-awareness are added to the traditional UCB algorithm.

- 6.

- Optimal method: For each time slot, VU selects the ES location with the lowest system cost for task processing. The optimal method is an oracle baseline with perfect real-time CSI and full ES state information. It makes offloading decisions without CSI uncertainty, providing a theoretical upper bound to evaluate the performance gap of practical algorithms.

To ensure fair comparison, all benchmark methods (naive UCB, MV-UCB, ALTO, and optimal) are implemented under identical system assumptions. Specifically, they share the same T2VC model structure, task arrival rules, ES computational capabilities and deployment ranges, energy budget limits, and communication channel parameters. No additional advantages or constraints are imposed on any method, guaranteeing the validity of performance comparisons.

6.1. Volatility of ES Candidates

In this subsection, in order to observe the impact of system volatility caused by vehicle mobility, three variables are fixed, i.e., input data Mbits, output data Mbits, CPU cycles/bit. New ES arrives and old ES leaves the communication range during each time period. The availability of ES candidate is shown in Table 2, where ✓ means ES is available, and × means ES is not available. Since ES processes tasks one by one, all computing resources are used, and the rest tasks are cached in the FIFO queue at each node.

Table 2.

Volatility of ES Candidates.

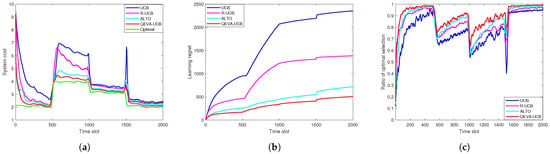

Figure 2 shows the latency-sensitive VU performance versus ES candidate volatility. It can be seen from Figure 2a that, for our learning-based method, due to the beginning of exploration, the system cost starts from more than 9. However, with the increasing of time, it finally converges to near optimal result of 2. Note that, there are some fluctuations when . This is because ES candidate varies in these three time slots, and VU needs to restart to explore the better offloading decision. The alternating rise and fall of fluctuations stem from the differences in adding or removing ES candidates, the cost rises when two ES candidates was removed in slot 501, and it decreases when ES candidates was added in slot 1001 and 1501. A similar situation also occurred in Figure 3a. It can also be seen that our proposed solution converges to the optimal value faster than other benchmark methods, due to the fact that it considers both the ES occurrence and the real-time distance between VU and each offloading candidate. Figure 2b shows that our proposed approach has smaller regret value compared with other methods due to the same reason. Figure 2c shows the ratio of the optimal ES selection, which is denoted by the ratio of the number of optimal decision to the total number of choice up to the tth time slot. It can be seen that, compared with other methods, our QEVA-UCB algorithm can make more accurate offloading decisions of a more than 95% optimal ES selection ratio within each ES fluctuation time.

Figure 2.

Latency-sensitive VU performance versus ES candidate volatility: (a) System cost. (b) Learning regret. (c) Ratio of optimal selection.

Figure 3.

Energy-efficient VU performance versus ES candidate volatility: (a) System cost. (b) Learning regret. (c) Ratio of optimal selection.

Figure 3 shows the energy-efficient VU performance versus ES candidate volatility. It can be seen from Figure 3a that, for our learning-based method, due to the beginning of exploration, the system cost starts from more than 20. However, with the increasing time, it finally converges to a near optimal result of 5. Note that there are some fluctuations when . This is due to the fact that the ES candidate varies in these three time slots, and VU needs to restart to explore the better offloading decision. It also verifies that our approach converges faster than other benchmark methods, due to the fact that it considers the data size, ES fluctuation, and the real-time distance between VU and each offloading candidate. Compared to our solution, the UCB algorithm converges slowly in the first two periods and is unable to learn the optimal offloading strategy because it cannot identify the fluctuation characteristics of ES. Figure 3b shows that our proposed approach has smaller regret value compared with other methods. Figure 3c shows the ratio of the optimal ES selection, and it can be observed that the QEVA-UCB algorithm is able to make more accurate decisions than other learning algorithms, which verifies that QEVA-UCB can effectively reduce the system cost of energy-efficient VU in case of ES volatility.

6.2. Data Size Influence

In this subsection, we assume that there is no ES volatility in each time slot and evaluate the learning performance under different data size. Some parameters are as follows: input data Mbits, output data Mbits, computing intensity CPU cycles/bit. Due to random arriving data size, the data volume processed in each time slot changes dynamically.

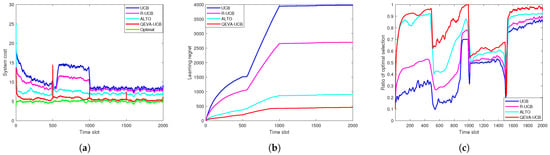

Figure 4 shows the latency-sensitive VU performance with random data size. It can be observed from Figure 4a that the system cost of the QEVA-UCB algorithm finally converges to about 3, which is near-optimal. Figure 4b shows that the our approach has the smallest learning regret. With the increase in time, the learning regret of QEVA-UCB gradually stabilizes and obtains superior behavior. Figure 4c shows the ratio of optimal selection. It can be seen that QEVA-UCB always has the best performance due to the fact that it can adjust the offloading decision according to the real-time data size and queue backlog. For example, the optimal ES selection ratio of QEVA-UCB is nearly two times higher than UCB.

Figure 4.

Latency-sensitive VU performance with random data size: (a) System cost. (b) Learning regret. (c) Ratio of optimal selection.

The energy-efficient VU performance with random data size is shown in Figure 5. It can be observed from Figure 5a that, compared with other methods, QEVA-UCB performance is near-optimal. From Figure 5b it can be seen that QEVA-UCB has the smallest learning regret. For example, it can reduce the regret value by 30% compared to the ALTO algorithm. Figure 5c shows that the learning effect for energy-efficient VU is not as good as that of the latency-sensitive VU. However, the selection accuracy of our approach is still higher than other algorithms. Compared with the UCB algorithm, the optimal ES selection ratio is increased by 50%.

Figure 5.

Energy-efficient VU performance with random data size: (a) System cost. (b) Learning regret. (c) Ratio of optimal selection.

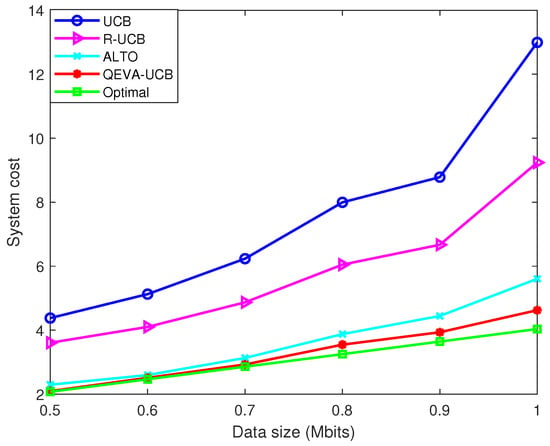

Figure 6 takes the latency-sensitive VU for instance and gives the system performance versus the change in data size. It shows that the system cost gradually grows as data size increases. However, since the QEVA-UCB algorithm is data size-aware, the system cost is the closest to the optimal method. In particular, when the data size is 1 Mbits, the system cost of our approach can be reduced by 20%, 125% and 300% compared to the ALTO, R-UCB and naive UCB algorithm, respectively.

Figure 6.

System cost versus the change in data size (taking latency-sensitive VU for instance).

6.3. Overall Performance of QEVA-UCB

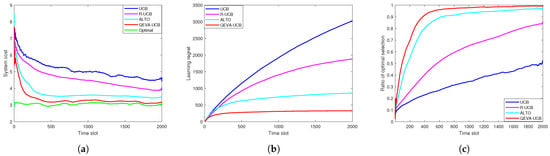

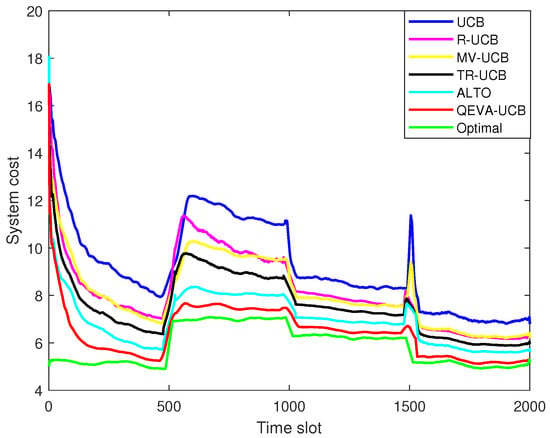

As can be seen from Figure 7, the QEVA-UCB algorithm is able to learn the optimal offloading policy faster than others when both ES candidate and task data size are volatile. This is because QEVA-UCB takes into account the task property, task arrival queue, offloading decision as well as vehicle mobility comprehensively. Therefore, in the T2VC system, it can still maintain the minimum system cost despite the fluctuation of task size and ES candidate. Specifically, in the second period, compared to the MV-UCB algorithm, the QEVA-UCB algorithm reduces the system cost by about 20%.

Figure 7.

Overall performance of QEVA-UCB (taking latency-sensitive VU for instance).

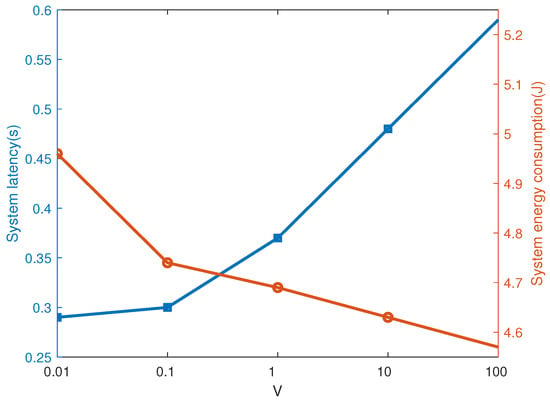

Figure 8 shows the impact of . The system power consumption decreases, and the system latency increases as grows up. The reason lies in that, as increases, the algorithm focuses more on the energy consumption rather than the latency. In this paper, is chosen for simulation in order to achieve a balance between system cost and energy constraint.

Figure 8.

Impact of .

7. Conclusions

In this paper, the T2VC model is proposed for the IoV system, and the QEVA-UCB algorithm is designed to cope with the high-dynamic and CSI information uncertainty issue. To avoid task arrival conflicts, we further introduce the task queuing policy. Under the constraints of energy conditions, the system cost denoted by the sum weighted latency and power consumption is minimized. Theoretical analysis and simulations confirm that QEVA-UCB, by integrating queue state awareness, energy volatility perception, and vehicle mobility adaptation, can make faster and more accurate offloading decisions for both latency-sensitive and energy-efficient VUs. It outperforms existing MAB-based approaches in system cost and learning regret, providing a practical solution for multi-tier vehicular computing task offloading. A key limitation of this work is its focus on a single VU scenario without considering multi-VU resource competition. Additionally, extreme network conditions like sudden communication interruptions are not fully addressed. In future work, we will extend the model to multi-VU scenarios and integrate anti-interference mechanisms to enhance practicality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W., Y.X. and Y.Z.; methodology, M.L.; software, H.H.; validation, S.W., Y.X. and D.L.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, M.L.; resources, D.L.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.X.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, H.H.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by China Southern Power Grid Company Limited technology project, grant number 074900KC24110001. The APC was funded by China Southern Power Grid Company Limited.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions, since the data involving the privacy of Hainan Power Grid Co., Ltd. and their customers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their respective institutions for their support during the research work.

Conflicts of Interest

Shijun Weng, Yigang Xing, Yaoshan Zhang were employed by Hainan Power Grid Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| QoE | Quality of Experience |

| GSI | Global State Information |

| T2VC | Three-Tier edge server-based Vehicular Computing |

| MAB | Multi-Armed Bandit |

| QEVA-UCB | Queue of Energy Volatility-Aware Upper Confidence Bound |

| VUs | Vehicle Users |

| MCC | Mobile Cloud Computing |

| MEC | Mobile Edge Computing |

| BS | Base Station |

| RSUs | Roadside Units |

| PCRSUs | Parked Cars to act as Roadside Units |

| VCEC | Vehicle Collaborative Edge Computing |

| MTVC | Multi-Tier Vehicular Computing |

| CDV | Collaborative Driving Vehicle |

| ES | Edge Server |

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| FIFO | First In First Out |

| MV-UCB | Matching-based Volatile Upper Confidence Bound |

| ALTO | Adaptive Learning-based Task Offloading |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| URLLC | Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communications |

| EC-SDIoV | Edge-Computing-aided Software-Defined networking IoV |

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 1

Once satisfying the time-averaged energy constraint, the queue will be strongly stable. The Lyapunov function is defined as follows:

in which is vector of all virtual queue backlogs in tth slot.

The corresponding Lyapunov drift is

According to the queue updating equation in Equation (13), we have

where .

According to Formula (16), the above formula can be simplified as follows:

where existence constant , so that () is in the feasible region. Define as the VU task offloading strategy that yields a feasible solution within , and is the energy consumption corresponding to strategy ; then, we have . Formula (A4) can be simplified as follows:

Because the policy has nothing to do with the virtual queue , we can delete the condition , and Formula (A5) can be written as

To get expectation of Equation (A6), we have

We sum the inequalities for time period T and divide both sides by T to take the average. Then, the result is obtained according to and :

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 2

The regret of this paper under the decision of the QEVA-UCB algorithm can be written as follows:

where is the expected learning regret for time slot t. . is the cost of the system under the optimal strategy.

where is a weighted sum of the Lyapunov drift and the conditional expectation of regret within a time slot .

We take the expectation for both sides of the inequality, sum over T time slots and divide both sides by . Then, the following is obtained:

The upper bound for solving Equation (A10) is equivalent to solving (A12). Thus, we have

in which, indicates the number of times for non-optimal task processing location selected, is the non-optimal task processing position time latency, and is the optimal task processing position time latency.

Defining functions , i.e. if z is true; otherwise, . Assume that the number of times for non-optimal choice is at least M. For the selected task processing location L, its confidence interval is no greater than that of the optimal location. So Equation (A13) can be simplified as follows:

The confidence interval is . There exists at least one pair satisfying the inequality. So we can simplify the formula to

If holds, then one of the below three requirements must be satisfied.

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- ;

- 3.

- .

The Chernoff–Hoeffding inequality can be applied to calculate the chance of occurrence of situation (1):

Similarly, the probability of case (2) is the following:

In this paper, the probability of case (3) is 0 by choosing M; that is, . Taking the square of the formula, we have

According to Equation (A14), it can be written as follows:

where the last inequality is due to that , , and as . Subsequently, according to Equations (A13) and (A20), can be expressed as follows:

As a result, an upper bound exists for the system regret :

References

- Qin, P.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Geng, S. Content Service Oriented Resource Allocation for Space-Air-Ground Integrated 6G Networks: A Three-Sided Cyclic Matching Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Feng, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z. Joint 3D-Location Planning and Resource Allocation for XAPS-Enabled C-NOMA in 6G Heterogeneous Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 10594–10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, J.; Lei, T.; Wang, S. Architecture and Key Technologies for Internet of Vehicles: A Survey. J. Commun. Inf. Netw. 2017, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Eldarrat, F.; Alqahtani, H.; Reznik, A.; de Foy, X.; Zhang, Y. Mobile Edge Cloud System: Architectures, Challenges, and Approaches. IEEE Syst. J. 2018, 12, 2495–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Hill, C.J.; Garrett, J.K.; Rajbhandari, R.; Rajbhandari, R. National Connected Vehicle Field Infrastructure Footprint Analysis: Deployment Scenarios; American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; He, H.; Zhao, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Efficient Resource Allocation with Context-Awareness for Parked Car Road Side Unit-Based Internet of Vehicles. J. Commun. 2022, 43, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, A.B.; Sargento, S.; Tonguz, O.K. Parked Cars are Excellent Roadside Units. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 18, 2490–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Fu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z. Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation for Parked-Cars-Based Cellular-V2V Heterogeneous Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 3046–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, D.; Jin, D.; Chen, S. Vehicular Fog Computing: A Viewpoint of Vehicles as the Infrastructures. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 3860–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukerche, A.; Soto, V. An Efficient Mobility-Oriented Retrieval Protocol for Computation Offloading in Vehicular Edge Multi-Access Network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 2675–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, T.; Ni, W.; Wang, X. Multi-Agent Multi-Armed Bandit Learning for Online Management of Edge-Assisted Computing. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2021, 69, 8188–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, J. Lyapunov-based Dynamic Computation Offloading Optimization in Heterogeneous Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Product Compliance Engineering-Asia (ISPCE-ASIA), Guangzhou, China, 4–6 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, M.J. Stochastic Network Optimization with Application to Communication and Queueing Systems; Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–211. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, P.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, M. Optimal Task Offloading and Resource Allocation for C-NOMA Heterogeneous Air-Ground Integrated Power Internet of Things Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 9276–9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, Y. A Task Oriented Computation Offloading Algorithm for Intelligent Vehicle Network with Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 180491–180502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zhu, C.; Wu, H.; Li, Q.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Toward Response Time Minimization Considering Energy Consumption in Caching-Assisted Vehicular Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 5051–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Q-Learning Based Task Offloading and Resource Allocation Scheme for Internet of Vehicles. Proceedings of 2020 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC), Chongqing, China, 9–11 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Wei, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Jia, W. Mobile Vehicles as Fog Nodes for Latency Optimization in Smart Cities. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 9364–9375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.B.; Sargento, S.; Tonguz, O.K. Smarter Cities With Parked Cars as Roadside Units. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 2338–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q. Offloading Schemes in Mobile Edge Computing for Ultra-Reliable Low Latency Communications. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 12825–12837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Ren, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, W.; Ren, Y.; Chen, K.C.; Zhang, H. Reliable Computation Offloading for Edge-Computing-Enabled Soft-ware-Defined IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 7097–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bute, M.S.; Fan, P.; Zhang, L.; Abbas, F. An Efficient Distributed Task Offloading Scheme for Vehicular Edge Computing Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 13149–13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Yang, F.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X. JOTE: Joint Offloading of Tasks and Energy in Fog-Enabled IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 3067–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olariu, S.; Eltoweissy, M.; Younis, M. Towards Autonomous Vehicular Clouds. ICST Trans. Mob. Commun. Appl. 2011, 11, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tout, H.; Mourad, A.; Kara, N.; Talhi, C. Multi-Persona Mobility: Joint Cost-Effective and Resource-Aware Mobile-Edge Computation Offloading. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2021, 29, 1408–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Gao, Y. An Optimal Algorithm for the Stochastic Bandits while Knowing the Near-Optimal Mean Reward. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Shen, C. Multi-Player Multi-Armed Bandits with Collision-Dependent Reward Distributions. IEEE Trans. Sign. Process. 2021, 69, 4385–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ye, Z.; Pei, Y.; Liang, Y.-C.; Niyato, D. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Task Offloading in UAV-assisted Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 6949–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, T.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X. BLOT: Bandit Learning-Based Offloading of Tasks in Fog-Enabled Networks. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2019, 30, 2636–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, X.; Song, J.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Niu, Z. Adaptive Learning-Based Task Offloading for Vehicular Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 3061–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Huang, X.; Shao, Z.; Yang, Y. An Integration of Online Learning and Online Control for Green Offloading in Fog-Assisted IoT Systems. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2021, 5, 1632–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Fu, Y.; Tang, G.; Zhao, X.; Geng, S. Learning Based Energy Efficient Task Offloading for Vehicular Collaborative Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 8398–8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, M.; Steinmetz, E.; Wymeersch, H. Vehicle-to-vehicle communications with urban intersection path loss models. In Proceedings of the IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Liao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ai, B.; Guizani, M. Reliable Task Offloading for Vehicular Fog Computing Under Information Asymmetry and Information Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 8322–8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, P.; Cesa-Bianchi, N.; Fischer, P. Finite-time Analysis of the Multiarmed Bandit Problem. Mach. Learn. 2002, 47, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.