Abstract

A class of partial differential equations with random noise is employed to model the pipe acoustic system. A high-precision compact differential scheme is constructed for its solution. To ensure numerical stability, a buffer layer technique is applied to absorb outgoing waves. The propagation of acoustic waves under different modes is simulated. Furthermore, a specific numerical example is provided, and the results show good agreement with theoretical analysis.

MSC:

65Z05

1. Introduction

Stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs) are widely used to model complex phenomena in fields such as mechanics, engineering, physics, and finance. In SPDEs, randomness originates in the coefficients or the forcing terms, thereby rendering the solutions stochastic [1,2,3]. Since explicit solutions to SPDEs are seldom obtainable, numerical methods have attracted considerable attention [4,5,6,7]. Among these, the compact finite difference scheme is a high-accuracy numerical method known for its excellent resolution, and it is widely employed for solving partial differential equations [8,9,10,11].

The study of sound propagation in pipes has important engineering applications. As an acoustic wave propagates along a pipe, it is reflected at the wall, creating secondary sound sources. These reflected waves then interfere with the primary radiated sound field in the fluid, forming a complex acoustic environment. Therefore, accurate prediction of this process requires high-precision numerical methods together with carefully formulated boundary conditions [12,13,14].

The treatment of boundary conditions is a critical issue in computational aeroacoustics. An effective boundary must allow acoustic energy to propagate out of the computational domain without spurious reflection. Theoretically, the domain should be infinite, but in practice it must be truncated. Therefore, non-reflective conditions must be imposed at the far-field boundaries [15]. Common techniques include the transition region method, the characteristic analysis method, and the asymptotic solution method. Another important class of boundaries involves prescribed energy input, such as sound waves emitted from a solid surface. Acoustic sources generated by mechanical vibration or transmitted through an open surface can be modeled as a pulsating mass flow [16].

In this paper, a pipeline acoustic system is modeled by a class of stochastic partial differential equations. A high-precision compact difference scheme is constructed for its numerical solution. Non-reflective boundary conditions are implemented using a buffer layer technique, and the propagation of acoustic waves under different modal excitations is simulated.

2. The Model

It can be considered that the density fluctuation in acoustic phenomena is small, and the fluid velocity fluctuation related to wave propagation is also small. The motion of sound waves can be described by linearizing the basic equations of fluid motion, and acoustics is concerned with the propagation of sound waves in air with little viscosity and heat conduction [17]. However, aeroacoustics mainly discusses the small disturbance in the air, and the spatial gradient of this small disturbance will not be greater than the flow disturbance itself. Therefore, the fluid motion can be described by the Euler equations. Based on the above assumptions, the acoustic field can be modeled by solving the following Linearized Euler Equations [18]:

where .

Let

Substituting these into the Euler equations and then expanding and simplifying, while neglecting the higher-order terms, we obtain the Linearized Euler Equations for an inhomogeneous flow field.

The equation in its conservation form is as follows,

where

where U represents flow variable and represent the flux. H represents the interaction term including the mean flow gradient effect, and represents the random sound source term in the flow field. represents the standard Gauss White noise, represents noise intensity, satisfy and , represents Dirac-Delta function. and represent the amplitude and frequency of the pressure fluctuation, respectively, and represents an adjustable parameter.

Acoustic waves propagate inside a cylindrical pipe in the form of distinct acoustic modes. Therefore, a section at the pipe entrance can be designated as a buffer layer. Within this layer, the acoustic quantity in the pipeline can be calculated and solved in terms of acoustic modes. The resulting modal solution then serves as the inlet condition, which may include stochastic components, for the Linearized Euler Equations. This approach allows the simulation of sound propagation, both inside and outside the pipe, under different modal excitations. In the circumferential direction, acoustic fluctuations are expanded in Fourier series. For instance, the pressure fluctuation is expressed as . Consequently, the Linearized Euler Equations can be written in the following complex form,

Each physical quantity in the pipe can be expressed by cylindrical coordinate . The fluctuating quantities are defined as follows: is the pressure fluctuation, is the density fluctuation, and are the velocity fluctuations in the axial, radial, and circumferential directions, respectively. The integer m denotes the circumferential mode number, and n denotes the radial mode number. represents radius of inner boundary of circular pipe ( in case of cylindrical pipe), and represents radius of outer boundary of circular pipe. For each pipe mode , the real part of the fluctuation is as follows,

where A is the amplitude of the pressure fluctuation, is the m-order Bessel function of the first kind, is the m-order Bessel function of the second kind, is the dimensionless frequency, is the axial wave number, is the radial wave number, and the expression of is given by,

Given the rigidity of the pipe wall, the radial velocity fluctuation at the boundary is zero, that is, . Therefore,

then,

The radial wave number of each mode can be obtained by iterative method, while the axial wave number can be directly solved by the following formula,

3. Numerical Discretization

3.1. Spatial Discretization

In this paper, a tridiagonal high-order compact difference scheme is employed,

where represents sound field variables, represents the spatial first derivative of the function , and i represent the grid step size and grid number, respectively, and represent the undetermined coefficients. While these coefficients can be determined by matching Taylor series expansions on both sides of the equation, this approach only ensures the formal order of accuracy, not necessarily the magnitude of the numerical error for a given grid resolution. To better analyze and optimize the scheme’s performance across all resolvable wavelengths, this work determines the coefficients by analyzing the scheme in wavenumber space via Fourier analysis.

By applying Fourier transform to the above equation, the following equation can be obtained,

where k represents the wave number. For analysis on a discrete grid, we introduce the dimensionless wavenumber , corresponding to the range for all waves resolvable on the grid.

where represents the actual quantized wavenumber of the difference scheme. The deviation between the actual quantized wavenumber and the accurate quantized wavenumber is the main reason for the numerical dispersion. Therefore, to preserve the dispersion relation as closely as possible, should approximate .

In this paper, the central compact difference scheme with sixth order accuracy is used

where, .

For the boundary treatment of the compact difference scheme, a biased stencil is employed, which has an accuracy one order lower than the interior scheme.

Compared to traditional finite difference schemes like central differencing, compact difference schemes can deliver higher-order accuracy while requiring fewer grid points. The effective accuracy of traditional schemes degrades rapidly in high-wavenumber, or equivalently, short-wavelength regions. In contrast, compact schemes maintain high spectral resolution and excellent accuracy even at high wavenumbers, particularly when their coefficients are optimized. Furthermore, for problems involving rich multi-scale physics such as turbulence and acoustic waves, compact difference schemes can capture small-scale structures accurately with fewer grid points, thereby lowering the required grid density. This significantly reduces the required scale of the computational grid. For transient problems solved using explicit time-stepping, the time step size is constrained. Although compact schemes do not raise the intrinsic stability limit, they enhance computational efficiency by enabling accurate simulations on coarser grids. From a physical perspective, coarser grids permit larger time steps, thereby reducing the number of time steps needed to achieve the same total simulation time.

The application of compact difference schemes relies on two key underlying assumptions: (1) The computational grid must be uniform. This is because the coefficients of compact schemes are derived by performing a Taylor series expansion at a single reference point and setting the truncation errors of all orders to zero. This derivation process strongly depends on the assumption of constant grid spacing. If the grid is non-uniform, the rate of change in grid spacing is introduced into the Taylor expansion, making the derivation of coefficients extremely complex and preventing the formulation of a simple linear relationship with constant coefficients. (2) The function must be sufficiently smooth, meaning it should possess continuous higher-order derivatives, within the region where the compact scheme is applied. Otherwise, if the function contains discontinuities such as shock waves, sharp gradients, or small-scale noise, the high-order scheme may induce spurious numerical oscillations. These oscillations can then propagate throughout the entire computational domain via implicit coupling, contaminating the global solution.

3.2. Time Discretization

We employ a fourth-order, low-dispersion Runge–Kutta method for time discretization.

where represents the forward time step, n represents time iteration step.

4. Non-Reflective Boundary Conditions

In engineering simulation, the actual physical domain is infinite, whereas the computational domain of simulation is usually limited. This makes the treatment of boundary conditions crucial. For noise simulation, stricter far-field boundary conditions are required: a non-reflective condition must be imposed to ensure that small acoustic disturbances exit the domain with minimal or no reflection. An effective non-reflective boundary condition is therefore essential. The far-field boundary condition not only needs to make the average flow flow smoothly out of the boundary, but also can make the sound wave do not produce non physical reflection on the boundary. If the boundary conditions are not handled properly, the non physical parasitic errors will return to the computational domain, which may lead to serious errors in the noise simulation results [19,20].

A buffer zone is established outside the computational domain. By gradually modifying the governing equations within this zone to damp outgoing waves, an absorbing boundary condition is effectively implemented, which is a well-established technique that has proven successful over decades of development. In this paper, three virtual grid layers are added in addition to the grid of the calculation area. A symmetric seven-point stencil is applied at all interior points. For points on the virtual grid layers, an asymmetric seven-point stencil is constructed. This allows spatial derivatives to be computed at the boundary with formalism and accuracy analogous to the interior scheme. At a non-reflective boundary, where acoustic waves propagate outward, the asymmetric stencil is oriented to match the wave propagation direction. This alignment ensures numerical stability, provided there are no strong incoming reflections from outside the computational domain [21].

In the buffer zone, the outgoing wave is gradually damped by the attenuation function . To ensure a smooth transition, is set to zero at the interface with the main computational domain, allowing waves to enter the buffer zone without distortion. The function then increases continuously and smoothly from the interface to the outer boundary, where it reaches its maximum value. This design ensures that the wave amplitude is effectively reduced to near zero at the outer boundary, thereby minimizing spurious reflections. The specific form of the attenuation function used in this work is given below.

The explicit decay solution variable after each time step iteration is as follows,

where is the solution vector after each iteration time step. Attenuation factor achieves a smooth transition through the following form,

where L represents the width of the buffer zone, x represents the distance from the inner boundary to the inner of the buffer zone, and and determine the shape of the attenuation function by manual setting. For the linearized Euler equations, the buffer zone serves to absorb outgoing waves, gradually reducing their amplitude to minimize spurious reflections.

5. Numerical Example

A section at the pipeline entrance is designated as a buffer layer. Within this layer, the acoustic field is decomposed and computed based on the acoustic modes described above. It is used as the random sound source input of the linear Euler equation to calculate the propagation of sound waves in different modes inside and outside the pipeline.

The computational grid uses a two-dimensional Cartesian grid with a computational domain of , the number of cell is 30,800, the pipeline region is and the thickness of the pipeline is considered uniform, the pipeline material is steel with a density of . The Mach number of the flow inside the pipeline is 0.45, so there is a strong shear layer at the outlet of the pipe. The shear layer not only affects the sound propagation path, but also affects the sound pressure amplitude in the process of sound propagation. When the sound wave propagates through the shear layer, it will produce refraction loss. At the same time, due to the refraction, the sound diffuses after passing through the shear layer. In order to maintain the conservation of energy, the sound energy per unit area decreases, resulting in the change of sound pressure amplitude in the sound field.

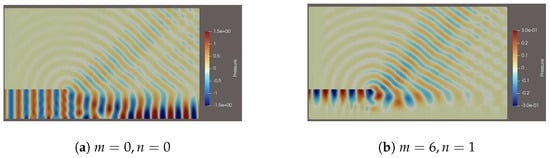

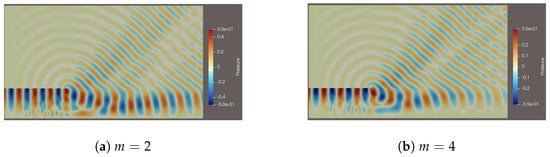

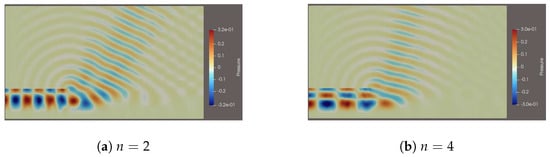

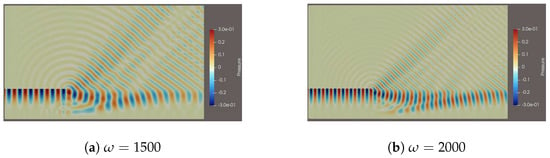

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the simulation results of noise under different parameters, the units of x and y coordinates are m, and the cross-section of the pipeline wall is not displayed. The results demonstrate that the acoustic wave attenuation is zero in the process of propagation from the outer boundary of the calculation domain to the outer boundary of the buffer layer. Further, there is no reflection at the boundary of the calculation domain, which indicates that the absorbing boundary condition in this paper successfully avoids the numerical pseudo waves reflected from the boundary. In addition, it can be seen that the sound propagation in the pipeline exhibits the following characteristics: (1) When the sound mode is , the sound only propagates in the axial direction in the form of plane wave, and there is no change in the sound distribution on the cross section of the pipeline. (2) In other acoustic modes, the sound not only changes along the axial direction of the pipe, but also has different distribution in the cross section. (3) As m increases, the propagation of sound waves in circumferential direction becomes more complex. (4) As n increases, the propagation of sound waves in radial direction becomes more complex. (5) As increases, the pulsation frequency of sound waves in both the circumferential and radial directions significantly increases. (6) The presence of the shear layer causes refraction of the plane wave near the layer, altering the direction of sound propagation.

Figure 1.

Calculation results of different pipe modals ().

Figure 2.

Calculation results of different pipe modals ().

Figure 3.

Calculation results of different pipe modals ().

Figure 4.

Calculation results of different pipe modals (m = 6, n = 1).

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have modeled the acoustic system of a cylindrical pipe using a class of partial differential equations with random noise and simulated the propagation of its acoustic modes. The main contributions are summarized as follows. Firstly, a PDE-based acoustic model for cylindrical pipes that incorporates random noise sources is developed. Secondly, a high-precision sound field simulation is achieved using a compact spatial discretization scheme combined with a high-order temporal discretization scheme, justified by the small magnitude of typical pressure fluctuations. Furthermore, spurious numerical reflections from boundaries are effectively suppressed by a buffer-layer technique. In addition, the calculated acoustic modal propagation shows good agreement with theoretical analysis. Finally, a compact difference scheme formulated for uniform grids is presented, which can be extended in future work to variable–coefficient schemes suitable for non-uniform grids or curvilinear coordinates.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and L.L.; Methodology, X.C. and L.L.; Software, X.C.; Validation, X.C. and L.L.; Formal analysis, X.C. and L.L.; Investigation, X.C. and L.L.; Resources, X.C. and L.L.; Data curation, X.C.; Writing—original draft, X.C.; Writing—review & editing, L.L. and S.Z.; Visualization, S.Z.; Supervision, L.L.; Project administration, L.L.; Funding acquisition, X.C. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12101021 and No. 12301341). The authors would like to thank the funding from the Beijing Municipal Education Commission for the Emerging Interdisciplinary Platform for Digital Business at Beijing Technology and Business University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mendes, R.V. Stochastic Solutions and Singular Partial Differential Equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2023, 125, 107406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q. Kernel-based learning methods for stochastic partial differential equations. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2024, 169, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahri, M. Barycentric Interpolation of Interface Solution for Solving Stochastic Partial Differential Equations on Non-Overlapping Subdomains with Additive Multi-Noises. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2018, 95, 645–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.P.; Zhao, W.; Li, H.R. A Structure-Preserving Reduced-Order Finite Difference Approach for a Class of Semilinear Stochastic Partial Differential Equations Driven by White Noise. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2025, 552, 129807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.Y. Convolutional Neural Network Based Simulation and Analysis for Backward Stochastic Partial Differential Equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 2022, 119, 21–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzonetto, S.; Salimova, D. Existence, Uniqueness, and Numerical Approximations for Stochastic Burgers Equations. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2020, 38, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.G.; Wu, J. Probabilistic Approach for Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations and Stochastic Partial Differential Equations with Neumann Boundary Conditions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2019, 477, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Mehra, M. Compact Filtering as a Regularization Technique for a Backward Heat Conduction Problem. Appl. Numer. Math. 2020, 153, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vo, L.; Wang, G. Higher Order Time Discretization Method for a Class of Semilinear Stochastic Partial Differential Equations with Multiplicative Noise. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 437, 115442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Zhang, P. A Reduced High-order Compact Finite Difference Scheme Based on Proper Orthogonal Decomposition Technique for KdV Equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 339, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.S.; Mehra, M. A Numerical Study of Asian Option with High-order Compact Finite Difference Scheme. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 57, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.L.; Xie, S.S.; Liang, D.; Fu, K. High Order Compact Block-Centered Finite Difference Schemes for Elliptic and Parabolic Problems. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 87, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.T.; Xu, R.M. An Optimal Compact Sixth-order Finite Difference Scheme for the Helmholtz Equation. Comput. Math. Appl. 2018, 75, 2520–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.H. Compact Difference Schemes for a Class of Space-time Fractional Differential Equations. Eng. Lett. 2019, 27, 269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Ji, L.C.; Zhou, L.; Sun, S.J. Effect of Blended Blade Tip and Winglet on Aerodynamic and Aeroacoustic Performances of a Diagonal Fan. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.Y.; Salama, C.A.T. New-Superjunction LDMOST with N-buffer Layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2006, 53, 1909–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.R.; Vogt, D.M.; Fischer, M.; Phillipsen, B.A. On the Far-field Boundary Condition Treatment in the Framework of Aeromechanical Computations Using ANSYS CFX. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A-J. Power Energy 2021, 235, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Q.; Cai, X.H. Lagrangian Stochastic Simulation of Atmospheric Dispersion from Sources near the Ground. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2014, 25, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Lin, P.; Wang, X.T.; Yu, T.F. Buffering Effect of Overlying Sand Layer Technology for Dealing with Rockfall Disaster in Tunnels and a Case Study. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04020127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, M.H.; Chen, C.L.; Jang, S.L. Study of Shallow Trench Isolation Technology with a Poly-Si Sidewall Buffer Layer. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2008, 23, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, L.; Falletta, S.; Ferrari, M.; Scuderi, L. CVEM-BEM Coupling for the Simulation of Time-Domain Wave Fields Scattered by Obstacles with Complex Geometries. Comput. Methods Appl. Math. 2023, 23, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.