Abstract

This paper addresses the tracking control problem for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems subject to full state constraints, actuator faults, and backlash-like hysteresis. An adaptive finite-time control strategy is proposed, using radial basis function neural networks to approximate unknown system dynamics. By integrating barrier Lyapunov functions with a backstepping design, the method guarantees semi-global practical finite-time stability of all closed-loop signals. The strategy ensures that all states remain within prescribed limits while achieving accurate tracking of the reference signal in finite time. The effectiveness and superiority of the proposed approach are demonstrated through simulations, including a numerical example and a rigid robot manipulator system, with comparisons to existing methods highlighting its advantages.

Keywords:

nonlinear systems; backlash-like hysteresis; actuator faults; full state constraints; finite-time stability MSC:

93C10; 93C40; 37N35

1. Introduction

In practical engineering applications, stochastic disturbances are a common challenge that can significantly compromise system stability. The presence of higher-order Hessian terms in the stochastic differentiation of Lyapunov functions further increases the complexity of controller design for stochastic nonlinear systems [1,2,3,4]. Compared to deterministic nonlinear systems, this complexity makes the design of effective controllers for stochastic systems more demanding. Recently, the study of stochastic nonlinear systems has attracted considerable attention, and adaptive backstepping methods, initially developed for deterministic systems, have been extended to stochastic scenarios [5,6,7]. For example, a globally adaptive control approach has been proposed for stochastic nonlinear time-delay systems subject to disturbances, ensuring robust performance despite temporal delays and random perturbations [8]. Additionally, an adaptive output-feedback strategy based on dynamic surface control has been developed to handle stochastic nonlinear systems with unmodeled dynamics in both state and input, providing effective control even under unmodeled uncertainties [9]. Moreover, an adaptive control method using output feedback has been presented for stochastic nonlinear systems with dynamic uncertainties, guaranteeing stable and accurate tracking performance despite system uncertainties [10].

However, existing methods are primarily designed for systems in which the nonlinearities are either precisely known or can be linearly parameterized. Such approaches are often inadequate when dealing with stochastic systems that exhibit structured uncertainties. To overcome these limitations, various adaptive fuzzy or neural network-based backstepping control methods have been developed [11]. These methods combine the backstepping design with fuzzy logic systems or neural networks, thereby improving their applicability to stochastic nonlinear systems [12,13]. For example, a recent study proposed an adaptive fuzzy control technique specifically for stochastic nonlinear systems, effectively handling challenges such as dead zones and unmodeled dynamics to ensure robust system performance [14]. Additionally, an event-based dynamic output-feedback adaptive fuzzy control approach has been developed, which utilizes event-triggered mechanisms to improve control efficiency and maintain system stability in the presence of uncertainties [15]. Furthermore, for stochastic nonlinear systems with multiple time-varying delays and input saturation, an adaptive neural control strategy has been introduced, providing effective control by addressing the complications caused by time-varying delays and input saturation [16].

Despite recent advances in control theory, many practical systems, such as rolling mills, biochemical processes, and pendulum dynamics, exhibit nonlinear behaviors that do not conform to standard affine models [17]. In these systems, traditional methods that assume a linear relationship between inputs and state variables are limited, especially in pure-feedback nonlinear systems where the direct use of state variables as control signals is not feasible. This limitation has motivated significant research into methods capable of effectively controlling nonaffine pure-feedback nonlinear systems [18,19]. To address these challenges, several innovative control strategies have been proposed. For instance, event-triggered adaptive fuzzy tracking control has been developed to manage systems with multiple constraints while ensuring accurate tracking performance and system stability [20]. Neural network-based adaptive control methods have also been introduced to handle issues such as time-varying delays and dead-zone inputs in stochastic nonlinear systems, thereby improving robustness and overall performance [21]. Additionally, a fuzzy adaptive tracking control approach has been proposed for constrained nonlinear switched stochastic pure-feedback systems, using fuzzy logic to handle constraints effectively and demonstrating enhanced robustness under varying operating conditions [22]. These developments underscore the ongoing efforts to design specialized control solutions that can manage the complexities present in nonaffine pure-feedback nonlinear systems across a wide range of practical applications.

Adaptive fuzzy and neural network-based backstepping control methods have made significant progress, but they often assume ideal conditions for all system components [23]. In practice, components such as actuators, sensors, and processors may fail unexpectedly during operation [24,25]. Addressing these challenges requires the development of fault-tolerant control strategies to ensure system reliability and safety under adverse conditions. Recent studies have focused on adaptive fuzzy backstepping approaches to handle uncertainties and actuator faults in nonlinear systems [26,27]. For stochastic nonlinear systems with nonstrict-feedback dynamics and actuator faults, adaptive fuzzy tracking control methods have been proposed to maintain accurate tracking performance and ensure system stability [28]. Strategies have also been developed to manage systems with output constraints and actuator faults, aiming to achieve robust control performance despite these limitations [29]. In scenarios involving nonlinear systems affected by Markovian actuator failures and stochastic disturbances, adaptive fault-tolerant stabilization methods have been introduced, providing effective stabilization in the presence of unpredictable actuator failures and noise through adaptive techniques [30]. Furthermore, for large-scale nonlinear systems facing actuator faults and output constraints, adaptive fuzzy fault-tolerant control strategies have been designed, utilizing fuzzy logic to ensure reliable and effective control in complex operational environments [31]. These developments highlight ongoing efforts to design control methodologies capable of mitigating the impact of faults and uncertainties, thereby enhancing the reliability and performance of nonlinear systems in practical applications.

Moreover, in practical engineering applications, control performance can be significantly influenced by hysteresis, a common nonlinearity present in various devices and systems, including electronic relay circuits, military systems, and mechanical actuators [32]. Hysteresis nonlinearities can severely limit system performance, making the development of effective control strategies to address these issues an active area of research. Studying the control of nonlinear systems with hysteresis inputs is crucial for achieving high-performance standards [33,34]. For instance, an adaptive output dynamic feedback control method has been proposed for nonaffine pure-feedback time-delay systems with backlash-like hysteresis [35]. This method effectively manages the challenges posed by nonlinear dynamics and unknown hysteresis effects, ensuring robust control performance. For uncertain nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis, an adaptive prescribed performance tracking control strategy has been developed [36], achieving the desired tracking performance despite uncertainties and hysteresis through adaptive control techniques. Additionally, an event-triggered adaptive fuzzy control approach has been introduced for stochastic nonlinear systems with unmeasured states and unknown backlash-like hysteresis [37]. This method combines fuzzy logic and event-triggered mechanisms to handle uncertainties and unmeasured states effectively, providing robust control performance.

Traditional control strategies typically aim for asymptotic stability, where the closed-loop system response converges over an infinite time horizon. However, in practical applications, finite-time convergence is often a critical performance requirement [38,39,40,41]. Finite-time control offers several advantages, including rapid response, high convergence accuracy, and robust disturbance rejection, making it a highly relevant and promising area of research. Significant progress has been made in this field, demonstrating its importance and potential in practical control applications [42,43,44]. For instance, an observer-based adaptive fuzzy finite-time control design with prescribed performance has been proposed for switched pure-feedback nonlinear systems [45]. This approach integrates fuzzy logic and adaptive techniques within an observer framework to achieve finite-time control objectives with guaranteed performance. In addition, a fuzzy adaptive finite-time output-feedback control strategy has been developed for stochastic nonlinear systems [46], focusing on compensating stochastic disturbances while ensuring finite-time convergence and enhancing robustness in uncertain environments. Observer-based finite-time control methods have also been applied to stochastic nonstrict-feedback nonlinear systems [47], addressing the challenges associated with nonstrict-feedback structures and stochastic disturbances while achieving stable and robust finite-time control performance.

The control approaches discussed above often neglect the consideration of state constraints, which limits their applicability in the tracking control of nonlinear stochastic systems. In industrial control applications, ensuring compliance with safety specifications requires careful management of various state constraints. Violating these constraints can degrade system performance or even cause significant safety hazards, highlighting the critical importance of incorporating state constraints into controller design [48,49,50,51]. To address this challenge, several effective control strategies have been developed, including model predictive control, data-driven control algorithms, and enhanced prescribed performance control methods. Recently, barrier Lyapunov functions (BLFs) have received growing attention for handling state constraints due to their simplicity and effectiveness [52,53,54,55]. For time-varying state-constrained nonlinear stochastic systems, adaptive neural network control strategies have been proposed to manage input saturation while enforcing state constraints [56]. These approaches leverage neural networks to adaptively handle dynamic state constraints in the presence of stochastic uncertainties and input limitations. Additionally, adaptive finite-time control strategies using command filters have been developed for stochastic nonlinear systems with time-varying full-state constraints and input saturation [57]. By integrating command filtering with adaptive neural networks, these methods achieve finite-time control objectives while addressing dynamic constraints and asymmetric saturation effects. In the context of non-triangular high-order nonlinear stochastic systems, adaptive fuzzy control techniques have been employed to handle asymmetric output constraints [58], using fuzzy logic to regulate complex high-order dynamics and ensure effective control performance despite the presence of output constraints.

Based on the discussion above, it is evident that existing finite-time control schemes largely focus on deterministic nonlinear systems and do not adequately address the complexities inherent in stochastic nonlinear systems, particularly those involving actuator faults, full state constraints, and backlash-like hysteresis. This work aims to fill this gap by investigating the use of neural networks in adaptive finite-time control design for pure-feedback stochastic systems. The presence of actuator faults and backlash-like hysteresis poses significant practical challenges that have not been thoroughly explored in previous studies. The motivation for this research stems from the critical need to develop robust control strategies capable of effectively handling these challenges in real-world applications, thereby enhancing system reliability and performance under adverse conditions. To address state constraints, this study incorporates barrier Lyapunov functions (BLFs) to enforce constraints and ensure that all system states remain within predefined safe regions. This approach significantly improves the practical applicability of finite-time control strategies for stochastic nonlinear systems and represents an important contribution to the field. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- (i)

- Compared with the existing studies [29,32], this work develops an adaptive finite-time control framework for stochastic pure-feedback nonlinear systems while simultaneously addressing several practical challenges, including actuator faults, full state constraints, backlash-like hysteresis, and stochastic disturbances. Most existing studies consider only a subset of these issues, whereas the proposed method incorporates all of them within a unified design. This integrated treatment enhances the reliability of the control scheme in realistic environments where multiple uncertainties can occur concurrently.

- (ii)

- In contrast to earlier works [13,19,29] that primarily concentrate on enforcing output constraints using barrier Lyapunov functions (BLFs), this paper extends the constraint-handling capability to full system states. By embedding BLF techniques into a recursive backstepping structure, the proposed controller guarantees that every system state remains strictly within predefined bounds throughout the entire operation. This development is particularly important for safety-critical applications. Furthermore, the controller ensures finite-time convergence, closed-loop stability, and accurate tracking of the reference signal. Comprehensive simulation results validate the effectiveness of the approach under various fault and disturbance conditions.

- (iii)

- The proposed method adopts the norm of the neural-network weight vector as the adaptive parameter instead of estimating individual weight components. This strategy significantly reduces the number of adaptive parameters, simplifies the computational burden, and improves robustness against parameter variations. As a result, the control design becomes more compact and better suited for real-time engineering applications.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the system and provides preliminary information. In Section 3, the stability analysis and details of the adaptive finite-time controller are discussed extensively. Section 4 presents two simulation examples to illustrate the effectiveness of the theoretical results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the article.

Notations. In this study, we consistently use the following notations: denotes the set of real numbers; refers to the n-dimensional real space; y indicates the system output; u represents the system input; v is the actual control input; for denotes the system state vector; and represents the Euclidean norm of the vector X.

2. Problem Formulation and Preliminaries

Consider stochastic pure-feedback nonlinear systems described by [59]

where the state vector and system output are represented by and , respectively. A r-dimensional standard Brownian motion is denoted by w, which is defined on a complete probability space , where the sample space is , the sigma-field is , the filtration is and the probability measure is P. Unknown smooth nonlinear functions are and . The system input u experiences actuator faults and backlash-like hysteresis.

In this study, each system state is required to remain within the set depicted below

where represents the constant with .

Define , .

By applying the mean value theorem [60], there exist and such that

where lies between 0 and , and lies between 0 and u.

Then system (1) is equivalent to

The system input u is susceptible to actuator faults, where the model for an undetectable fault is described in [39] as

where denotes the actuation effectiveness, and represents an uncontrollable additive actuation fault. The input is subject to backlash-like hysteresis, which is represented as follows [26]:

where constants , c, and satisfy . Following an approach [26], one has

with

where and represent the initial conditions of u and v. The function is bounded such that

- Control Objective.

The aim of this paper is to develop an adaptive finite-time controller for stochastic nonlinear systems (1) in pure-feedback form. The designed controller ensures that within the closed-loop system all signals remain bounded and that the system output y closely follows a specified reference signal , while all system states stay within the constraint boundaries.

Assumption 1

([50]). The signs of are known, and ∃ constants and ensuring . Adopting for simplicity.

Assumption 2

([50]). The reference signal satisfies , and its ith time derivative is bounded by for where are positive constants.

Assumption 3

([39]). Both and are bounded time-varying unknown functions. In particular, and exist constants such that and .

Lemma 1

([50]). For all , , one has

Remark 1.

Assumptions 1–3 are necessary to ensure the feasibility, stability, and performance of the proposed control design. Specifically, Assumption 1 represents a controllability condition for the system (4), ensuring that the control gain functions have known signs and are bounded away from zero and from above, which guarantees that the control input can effectively influence the system dynamics [50]. Assumption 2 ensures that the reference signal and its derivatives are bounded, which is required for the recursive backstepping design and barrier Lyapunov function formulation, allowing all system states to remain within prescribed limits while achieving accurate tracking [50]. Assumption 3 characterizes actuator faults and uncertainties, where denotes the actuation effectiveness and represents an uncontrollable additive actuation fault. This assumption allows the controller to compensate for faults and uncertainties, ensuring stable operation and desired performance under partial actuator failures and disturbances [39]. These assumptions are explicitly applied in the controller design and stability analysis throughout the paper.

Remark 2.

Previous research [1] primarily focused on adaptive control techniques tailored for stochastic nonlinear systems structured in strict feedback form rather than pure feedback form. Recent advancements, exemplified by the BLF-based control approach for pure feedback stochastic nonlinear systems [59], have effectively achieved uniformly bounded tracking control. However, these methods have not comprehensively addressed the integration of state constraints into their frameworks. In prior research [46,47], finite-time control schemes for nonlinear stochastic systems have been introduced but faced challenges in fully incorporating comprehensive state constraints into their control strategies. This paper proposes a novel approach using barrier Lyapunov functions (BLFs) and neural networks for finite-time control, specifically to address the complexities of stochastic pure feedback nonlinear systems with state constraints.

2.1. Theory of Neural Network Approximation

As stated in [32], the RBFNNs used in this work will approximate any continuous function .

where the number of nodes in the neural network is indicated by , the weight vector is and the basis function vector is with each selected as the Gaussian function

where the length of the Gaussian function is and the center of the receptive field is . With an arbitrary degree of precision, the neural network may estimate any continuous function over a compact set as

where the approximation error satisfying for some small is represented by and denotes the ideal constant weight vector.

2.2. Stochastic Finite-Time Theory

Consider the following stochastic nonlinear system as [50]

where is a r-dimensional standard Brownian motion, and denotes the state vector of the system, and represent the local Lipschitz functions.

Definition 1

([47]). Define the differential operator for a positive function , which is twice continuously differentiable on , with respect to the system (14) as

where denotes the matrix trace.

Definition 2

([50]). For every initial condition , the equilibrium point of system (14) achieves semiglobal practical finite-time stability (SGPFS) in probability if there exists a positive ϵ and a finite settling time such that

Lemma 2

([47]). For every , , and positive constants , one has

Lemma 3

([27]). For every , one has

where , , , and .

Lemma 4

([50]). For system (14), if there exists a twice continuously differentiable function , positive constants , , , and two functions , such that

Then the stochastic nonlinear system (14) achieves SGPFS. Specifically, for all , define and let . Then, the time required for to reach the set is bounded by ; hence, for all , holds.

3. Controller Design and Stability Analysis

The upcoming sections propose an adaptive tracking control approach for stochastic nonlinear systems (1) using the backstepping technique and barrier Lyapunov function (BLF) in a recursive manner. The design process involves n steps. Steps 1 through focus on designing virtual controllers for . In Step n, the real controller v is formulated. The backstepping design procedure initiates with the following coordinate transformation:

where is the system output, is the desired signal, are the state variables of the system, and represents the virtual controller.

Step 1: By using (4) and (20), one has

Consider a Lyapunov function candidate as

where with is the estimation of , and ,

From (10) and (11), one has

Now formulated the nonlinear unknown function as

According to the RBFNN approximation in (13), the function can be approximated as

where denotes the ideal weight vector with and represents the input vector.

From (24) and (25), (23) can be written as

By employing Lemma 3, one has

with , , and being the design parameters.

The virtual controller can be designed as

with being the positive design parameter.

Since , we have

By using (27) to (31) into (26) gives

From Lemma 3, we have

By using (33) into (32), one has

Step (): From (4) and (20), one has

where

Take the following Lyapunov function candidate as

where and represents the estimation of , and .

By employing (35) and (37), becomes

Now formulated the nonlinear unknown function as

According to the RBFNN approximation in (13), the function can be approximated as

where signifies the optimal weight vector with and represents the input vector with .

By employing (39) and (40), (38) becomes

By utilizing Lemma 3, one has

with , , and being the constants.

The virtual controller can be formulated as

with being the positive design parameter.

As , one has

By using (42)–(46) into (41) gives

In accordance with the derivation steps mentioned earlier, is expressed as

By using (48) into (47), one has

By employing Lemma 3, we have

By employing (50) into (49), we have

Step : Based on the relationships described in (4), (5), (7), and (20), we can deduce the following

with

Take the following Lyapunov function candidate as

with and being the estimation of , and .

By using (52) into (54), we have

By applying (9), Lemma 3, Assumptions 1 and 3, we obtain

By using (56) and (57) into (55), we have

Now, formulated the nonlinear unknown function as

According to the RBFNN approximation in (13), the function can be approximated as

where denotes the input vector with , and signifies the optimal weight vector with and .

By employing (59) and (60) into (58), we have

By using Lemma 3, we have

with , , and being the constants.

Now, formulate the real controller v as

with being the positive design parameter.

By using (65) and Assumption 3, we can derive

By using (62)–(66) into (61), one has

In accordance with the derivation steps mentioned earlier, is expressed as

By using (68) into (67), we have

The formulation of adaptation laws is as follows:

with being the positive design parameters.

By employing (70) into (69), one has

Theorem 1.

Considering the pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear system (1) with integrated actuator faults and backlash-like hysteresis, and under Assumptions 1–3 along with the inclusion of virtual controllers (30), (45), real controller (65), and adaptive laws (70), we guarantee the boundedness of all system variables. Additionally, the tracking error converges to zero in finite time, ensuring that all state variables remain within their specified boundaries.

Proof.

Utilizing Lemma 3, one can deduce

By applying (72) to (71), we obtain

It can be demonstrated using Lemma 1 that , which implies holds for . Thus, it follows

Let , , , and . From Lemma 2, one can derive

Moreover, we have

By using (76) into (74), we have

Let

Then, utilizing Lemma 2, (77) can be expressed as

Let , where and . From Lemma 4, for all ,

which implies that the closed-loop systems are SGPFS.

Given that and considering , it follows that . By defining and , we obtain . Since , , , and are all bounded, it follows that is also bounded with . Considering , it consequently holds that . Defining and results in . Similarly, for , it follows that . Therefore, all state constraints are satisfied, completing the proof. □

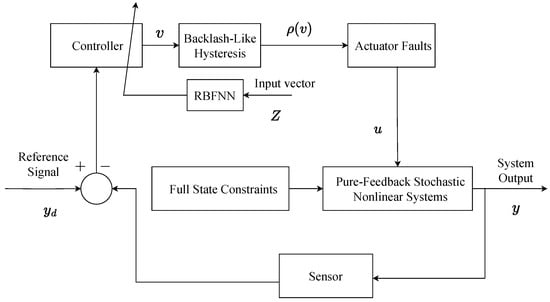

Figure 1 illustrates the block diagram of the proposed control methodology. This diagram visually represents the structure and interaction of various components within the control scheme.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the proposed control method.

Remark 3.

While existing literature extensively covers methods for achieving full state constraints in infinite-time tracking control problems [32,36], practical industrial systems often require achieving control objectives within finite time. This paper addresses this gap by detailing an adaptive finite-time control approach for stochastic nonlinear systems. The method accommodates full state constraints, actuator faults, and backlash-like hysteresis, enhancing its applicability to real-world industrial settings.

Remark 4.

From (30), (45), and (65), it is observed that the estimation of the neural network weight vector’s norm is prioritized over tracking the complete weight vector itself. This strategic use of adaptive law (70) ensures that only n parameters need updating across the entire system. As a result, this approach substantially minimizes the online computational load required by the controller.

Remark 5.

Theorem 1 indicates that the tracking error is influenced by the parameters and . Reducing while increasing and can result in smaller tracking errors, improving the system’s tracking performance. However, increasing and or decreasing also leads to higher control energy consumption. Therefore, careful selection of these design parameters is crucial to achieve a proper balance between tracking accuracy and control efficiency. In practical implementation, the parameters are determined through a systematic trial and error procedure. Initially, moderate values of , , and are chosen and the system is simulated. Based on the observed tracking performance and control energy, the parameters are iteratively adjusted. This process is repeated until satisfactory tracking accuracy is obtained while maintaining reasonable control effort, ensuring the controller performs effectively under the given system constraints and uncertainties.

Remark 6.

The proposed adaptive finite-time control scheme has strong application value in practical engineering systems where reliability and safety are essential. The ability to handle actuator faults, backlash-like hysteresis, stochastic disturbances, and full state constraints simultaneously makes the method suitable for multi-agent coordination, robotic manipulators, autonomous vehicles, and other safety-critical systems. In such applications, ensuring that all system states remain within prescribed bounds while achieving fast and accurate tracking is crucial for maintaining stable and safe operation.

4. Simulation Results

To illustrate the efficacy and reliability of the proposed control strategy, a numerical example and a practical example involving a rigid robot manipulator are presented in this section.

Example 1.

Consider the pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear system as

where and are the state variables with , , y is the system output, and u is the system output. The control objective is for the system output y to track the reference signal .

The model of actuator fault (4) is taken as

where , and . The parameter of the backlash-like hysteresis (5) are chosen as , , and .

The virtual controller , real controller v, and the adaptive law are chosen as

The initial condition are set as , . The design parameters are , , , , , , , , .

The RBF neural networks are set up as follows: consists of 49 nodes evenly spread across the interval with a width of two, while includes 343 nodes uniformly distributed over with the width 2.

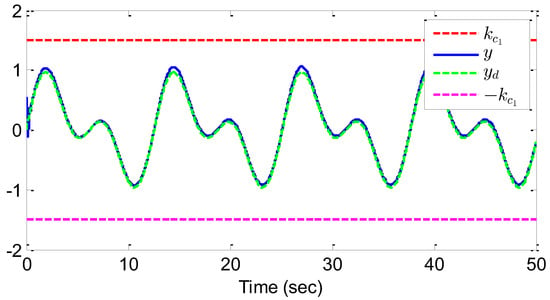

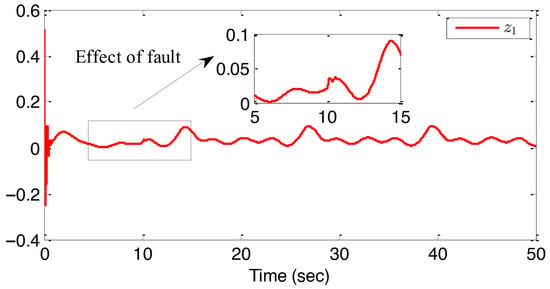

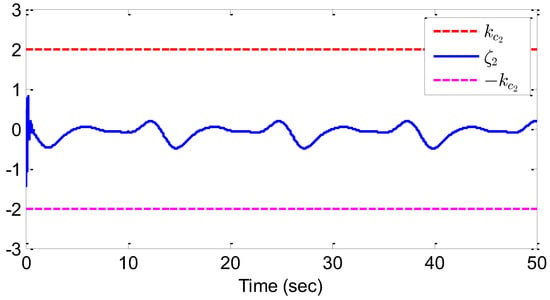

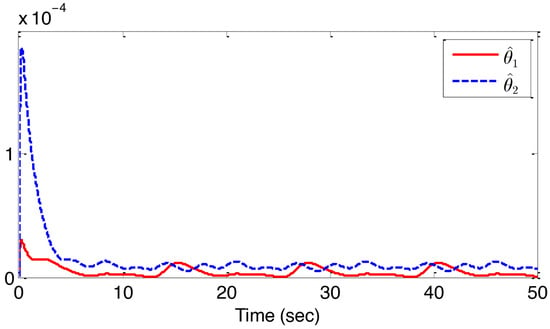

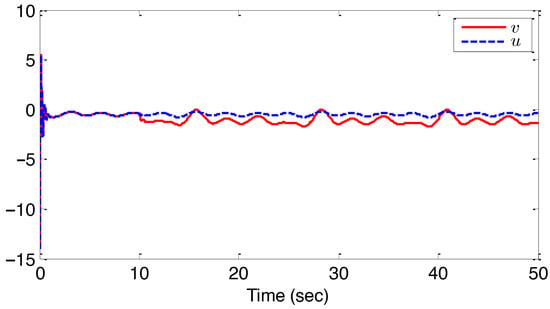

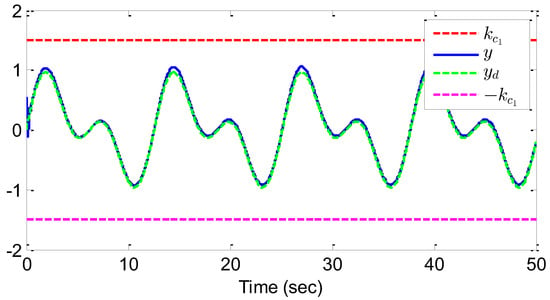

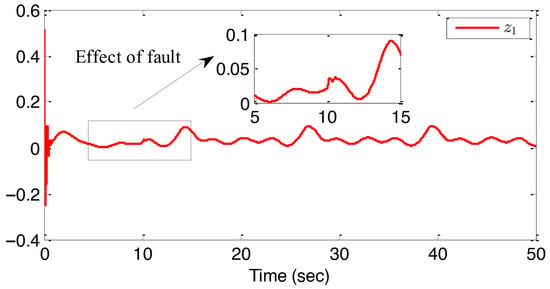

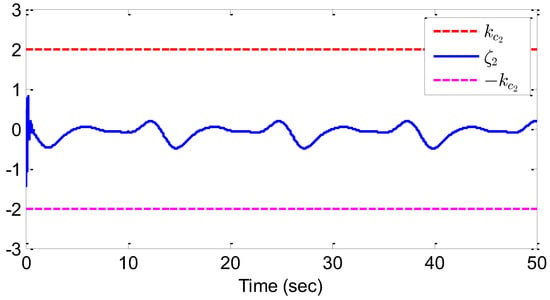

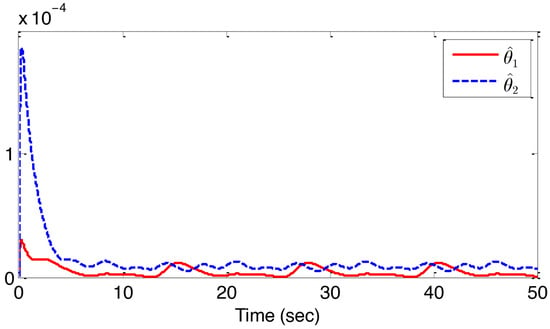

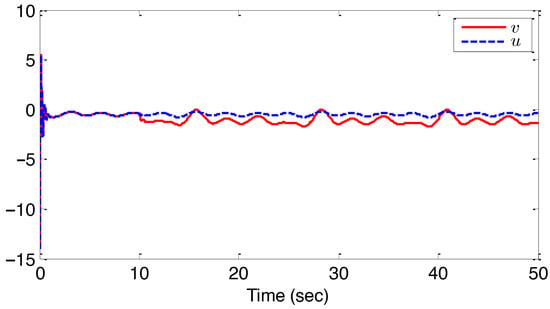

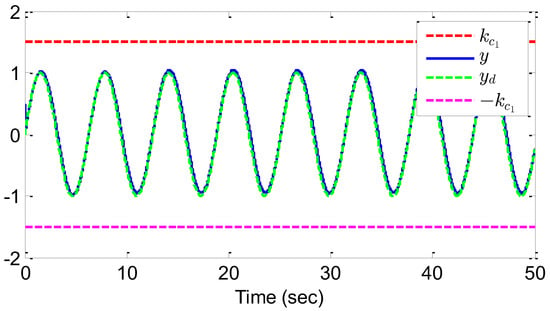

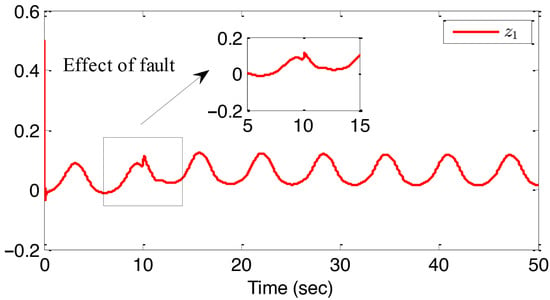

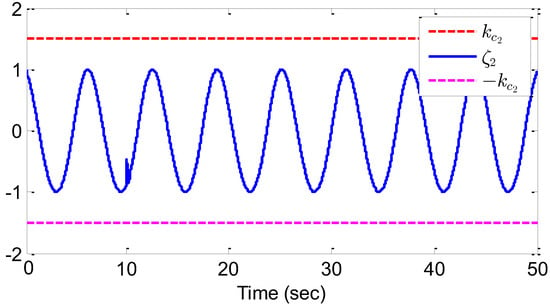

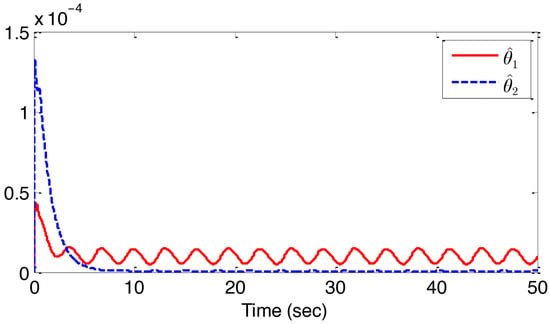

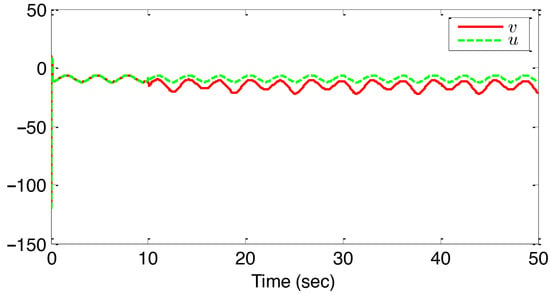

The results from Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 highlight important observations. Figure 2 shows how the output y closely tracks the expected signal within a finite time, while ensuring all states remain within their specified bounds. Figure 3 details the tracking error between the output and the reference signal. In Figure 4, the state adheres to its defined constraints. Figure 5 illustrates the stabilization of the adaptive parameters and . Finally, Figure 6 presents the behavior of both the actual control input v and the system input u. These figures collectively demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed control method in maintaining system variables within bounds and achieving convergence in tracking error.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of y and for example 1.

Figure 3.

The response of the tracking error for example 1.

Figure 4.

The response of the state variable for example 1.

Figure 5.

Trajectories of the adaptive laws , for example 1.

Figure 6.

Control input v and system input u for example 1.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed finite-time adaptive control scheme, a comparison is made with the existing adaptive control method reported in [48]. The performance metrics used for the comparison are defined as follows [60]:

where M represents the total number of sampling points. The indexes are calculated over the simulation period from 0 to 50 s with a sampling interval of 0.01 s. Table 1 presents a detailed comparison of the proposed method with the existing method reported in [48]. It is evident that the proposed finite-time adaptive control scheme achieves smaller output tracking errors and comparable or reduced control effort compared to the existing method. This demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed strategy in ensuring accurate tracking while maintaining efficient control input.

Table 1.

Performance comparison between the proposed method and the existing method [48] for example 1.

The improved performance of the proposed method can be attributed to the integration of finite-time adaptive control with barrier Lyapunov functions, which enforces state constraints and accelerates convergence of the tracking error. By contrast, the existing method in [48] relies on conventional adaptive control, which does not explicitly guarantee finite-time convergence or effectively handle state constraints. Consequently, the proposed strategy not only achieves faster and more accurate tracking but also maintains all system states within predefined safe bounds, highlighting its practical advantages in stochastic nonlinear systems with actuator faults and hysteresis.

Example 2.

To further substantiate the efficacy of the proposed approach, we examine a practical scenario involving a rigid robot manipulator system affected by stochastic disturbances [18]. The system dynamics are governed by

where and denote the state variables, y represents the system output, and u is the actual control input. Specifically, and correspond to the angular position and relative angular velocity of the manipulator, respectively. Parameters , , r, and denote the load mass, gravitational constant, length of the manipulator, and represents the inertia coefficient. Given the presence of stochastic disturbances inherent in practical rigid robot manipulator systems, the system (89) is adjusted as follows:

where and are the state variables, with , , y is the system output, and u is the system output. The control objective is for the system output y to track the reference signal .

The model of actuator fault (4) is taken as

where , and . The parameter of the backlash-like hysteresis (5) are chosen as , , and .

The virtual controller , real controller v, and the adaptive law are chosen as

The initial conditions are set as and . The design parameters are , , , , , , , , and . The RBF neural networks are configured as follows: consists of 49 nodes evenly distributed across the interval with a width of 2, while includes 343 nodes uniformly spread over with a width of 2.

The simulation results, depicted in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, highlight several significant findings. Figure 7 illustrates the accurate tracking of the output y with the desired signal within a finite time, ensuring all states remain within their specified limits. Figure 8 presents the tracking error between the output and the reference signal. In Figure 9, the state is shown to adhere to its designated constraints. Figure 10 demonstrates the rapid stabilization of the adaptive parameters and . Finally, Figure 11 provides an overview of the actual control input v alongside the system input u. Together, these figures collectively affirm the effectiveness of the proposed control method in maintaining bounded system variables and achieving convergence in tracking error.

Figure 7.

Trajectories of y and for example 2.

Figure 8.

The response of the tracking error for example 2.

Figure 9.

The response of the state variable for example 2.

Figure 10.

Trajectories of the adaptive laws , for example 2.

Figure 11.

Control input v and system input u for example 2.

Similar to the Example 1, performance indexes are used to compare the effectiveness of the proposed finite-time adaptive control method with the existing traditional adaptive control scheme reported in [48]. Table 2 presents the comparison results. The proposed finite-time adaptive control method achieves smaller tracking errors while maintaining comparable control effort relative to the traditional adaptive control scheme. These results demonstrate that the proposed strategy provides faster convergence and improved accuracy, while effectively handling system uncertainties and constraints.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between the proposed method and the existing method [48] for example 2.

The superior performance of the proposed method arises from the integration of finite-time adaptive control with barrier Lyapunov functions, which ensures rapid tracking and enforces state constraints. In contrast, the traditional method does not explicitly guarantee finite-time convergence or fully enforce state constraints, which accounts for the observed differences in performance.

Remark 7.

The feasibility of Theorem 1 is guaranteed by the design of the virtual and real controllers along with the adaptive laws, which ensure that all state variables remain within prescribed boundaries and that the tracking error converges in finite time. The controller parameters can be chosen systematically using a trial-and-error procedure or by following the stability analysis guidelines. The practical applicability of Theorem 1 is further illustrated through simulations, including a numerical example and a rigid robot manipulator system. The results demonstrate that the proposed controller can be effectively implemented, confirming the feasibility of Theorem 1 in both theoretical and practical scenarios.

Remark 8.

The proposed adaptive finite-time control methodology can be potentially extended to other classes of nonlinear systems. For instance, it can be applied to networked multi-agent systems using pinning-based neural control with self-regulation intermediate event-triggered mechanisms [61], as well as to multiple networked mechanical systems employing event-based adaptive sliding-mode containment control under parameter uncertainties [62]. The key design principles, including adaptive neural network approximation, barrier Lyapunov functions, and finite-time backstepping, provide a systematic framework to ensure stability, handle state constraints, and achieve accurate tracking in these more complex scenarios. Therefore, the proposed approach demonstrates flexibility and applicability beyond the stochastic pure-feedback nonlinear systems considered in this study.

5. Conclusions

This article presents an adaptive finite-time control method for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems subject to actuator faults, full state constraints, and backlash-like hysteresis. The proposed approach employs RBFNNs to approximate unknown system functions. By integrating the Barrier Lyapunov Function with the backstepping technique, the method ensures semiglobal practical finite-time stability of all signals in the closed-loop system, maintaining system states within predefined boundaries and enabling the output to track the reference signal efficiently within finite time. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed control scheme. Compared to the existing adaptive control method [48], the proposed strategy achieves lower tracking errors and reduced control effort, as reflected in Table 1 and Table 2. For instance, the output tracking index and control input index indicate a significant improvement, highlighting the capability of the method to handle actuator faults, hysteresis, and state constraints effectively. These quantitative comparisons clearly confirm the superior performance and reliability of the proposed control approach. The insights from this study suggest several directions for further research. Future work can focus on addressing input quantization effects and extending the control methodology to achieve fixed-time stability for stochastic nonlinear systems. Additionally, applying the proposed strategy to more complex practical systems, such as multi-degree-of-freedom robotic manipulators or networked cyber–physical systems, can validate its scalability and robustness. Integration of advanced learning-based estimation and optimization techniques may further improve performance under uncertainties and external disturbances, offering a pathway to develop more practical and resilient control strategies in related research areas.

Author Contributions

M.K.: Writing—original draft, Supervision; P.M.: Writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2025-FC-01002).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, S.; Huang, J. Decentralized adaptive event-triggered fault-tolerant cooperative control of multiple unmanned aerial vehicles and unmanned ground vehicles with prescribed performance under denial-of-service attacks. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, M.; Krichen, M.; Alhazmi, H.; Mercorelli, P. Neural network-based finite-time control for stochastic nonlinear systems with input dead-zone and saturation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 17369–17379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, M. Neural network-based adaptive fault-tolerant control for nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis and unmodeled dynamics. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2025, 141, 108478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Command-filtered Nussbaum design for nonlinear systems with unknown control direction and input constraints. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xing, L.; Sun, L. Fixed-time command-filtered control for nonlinear systems with mismatched disturbances. Mathematics 2024, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.Y.; Chang, X.H. Adaptive fault-tolerant tracking control for continuous-time interval type-2 fuzzy systems. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yu, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Ou, L.; Zhou, L. Event-triggered adaptive optimal tracking control for nonlinear stochastic systems with dynamic state constraints. ISA Trans. 2023, 139, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Xie, X.J. Global adaptive stabilization and tracking control for high-order stochastic nonlinear systems with time-varying delays. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2018, 63, 2928–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, J.; Yi, Y. Adaptive output feedback dynamic surface control of stochastic nonlinear systems with state and input unmodeled dynamics. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2016, 30, 864–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xia, X. Adaptive output feedback tracking control of stochastic nonlinear systems with dynamic uncertainties. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2015, 25, 1282–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.P.; Lai, G. Adaptive neural control of a class of stochastic nonlinear uncertain systems with guaranteed transient performance. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 50, 2971–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Chen, C.P.; Tong, S. A novel adaptive NN prescribed performance control for stochastic nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 3196–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Su, S.F.; Wu, Y.; Xia, J. Novel adaptive fuzzy control for output constrained stochastic nonstrict-feedback nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, W. Adaptive fuzzy control of stochastic nonlinear systems with fuzzy dead zones and unmodeled dynamics. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2018, 50, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Li, K.; Guan, X. Event-based dynamic output feedback adaptive fuzzy control for stochastic nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 26, 3004–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Jiao, T.; Wei, Y.; Song, G.; Chu, Y. Adaptive neural control of stochastic nonlinear systems with multiple time-varying delays and input saturation. Neural Comput. Appl. 2014, 25, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghlache, S.; Ghellab, M.Z.; Djerioui, A.; Bouderah, B.; Benkhoris, M.F. Adaptive fuzzy fast terminal sliding mode control for inverted pendulum-cart system with actuator faults. Math. Comput. Simul. 2023, 210, 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.Y.; Wu, L.B.; Zhao, N.N.; Gao, C. Event-triggered adaptive prescribed performance control for a class of pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with input saturation constraints. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2020, 51, 2238–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Dong, X.; Yang, F. Adaptive neural control for stochastic pure-feedback non-linear time-delay systems with output constraint and asymmetric input saturation. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017, 11, 2288–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, M.; Qiu, J.; Gao, H. Event-triggered adaptive fuzzy tracking control for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with multiple constraints. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, T.; Feng, G.; Zhao, R.; Shan, Q. Neural network-based adaptive control for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with time-varying delays and dead-zone input. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 5317–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Shahnazi, R.; Haghani, A. Fuzzy adaptive tracking control of constrained nonlinear switched stochastic pure-feedback systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yu, H. Event-triggered adaptive tracking for constrained multi-agent systems with saturated inputs and actuator faults. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 225, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, M.; Krichen, M.; Alhazmi, H.; Mercorelli, P. Neural network-based adaptive fault-tolerant control for strict-feedback nonlinear systems with input dead zone and saturation. J. Franklin Inst. 2025, 362, 107471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Sun, K.; Tong, S. Adaptive asymptotic tracking control of uncertain fractional-order nonlinear systems with unknown control coefficients and actuator faults. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2024, 182, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, M. Neural networks-based adaptive fault-tolerant control for stochastic nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis and actuator faults. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 70, 1995–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrat, M. Adaptive fault-tolerant control for a class of nonstrict-feedback nonlinear systems with unmodeled dynamics and dead-zone output using multi-dimensional Taylor networks. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 13289–13306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, W. Adaptive fuzzy tracking control for a class of nonstrict-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 50, 3456–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Adaptive fault tolerant tracking control for a class of stochastic nonlinear systems with output constraint and actuator faults. Syst. Control Lett. 2017, 107, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Liu, B.; Wang, W.; Wen, C. Adaptive fault-tolerant stabilization for nonlinear systems with Markovian jumping actuator failures and stochastic noises. Automatica 2015, 51, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Tong, S. Adaptive fuzzy output-constrained fault-tolerant control of nonlinear stochastic large-scale systems with actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2017, 47, 2362–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharrat, M.; Krichen, M.; Alkhalifa, L.; Gasmi, K. Neural networks-based adaptive command filter control for nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis and its application to single link robot manipulator. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Wu, Y. Adaptive asymptotic tracking control for stochastic nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2022, 35, 1824–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, P.; Lim, C.C. Event-triggered adaptive leaderless consensus control for nonlinear multi-agent systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2021, 31, 7409–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, S. Adaptive output dynamic feedback control for nonaffine pure-feedback time delay system with unknown backlash-like hysteresis. J. Franklin Inst. 2024, 361, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, S.L.; Zhou, Y.F.; Han, Y.Q.; Wang, W.W.; Zhou, Q.H. Adaptive prescribed performance tracking control for uncertain nonlinear systems with unknown backlash-like hysteresis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2024, 238, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, C. Event-triggered adaptive fuzzy control for stochastic nonlinear systems with unmeasured states and unknown backlash-like hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Li, T. Fixed-time command-filtered composite adaptive neural fault-tolerant control for strict-feedback nonlinear systems. ISA Trans. 2024, 145, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.P. Adaptive finite-time control of stochastic nonlinear systems with actuator failures. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2019, 374, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Chu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z. Adaptive finite-time control for stochastic nonlinear systems subject to unknown covariance noise. J. Franklin Inst. 2018, 355, 2645–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, K.; Zhang, H. Adaptive finite-time tracking control of nonlinear systems with dynamics uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 5737–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wu, H.; Cao, J. Finite-time synchronization of impulsive stochastic systems with DoS attacks via dynamic event-triggered control. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 219, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Karimi, H.R.; Fu, Y. Event-triggered robust fuzzy adaptive finite-time control of nonlinear systems with prescribed performance. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 1460–1471. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Q. Adaptive fuzzy finite-time control for nonstrict-feedback nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 10420–10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Alkhateeb, A.F. Observer-based adaptive fuzzy finite-time control design with prescribed performance for switched pure-feedback nonlinear systems. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 69481–69491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, P.X. Fuzzy adaptive finite-time output feedback control of stochastic nonlinear systems. ISA Trans. 2022, 125, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, F. Observer-based finite-time control of stochastic non-strict-feedback nonlinear systems. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2021, 19, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Lu, S.; Tong, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, C.P.; Li, D.J. Adaptive control-based barrier Lyapunov functions for a class of stochastic nonlinear systems with full state constraints. Automatica 2018, 87, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.B.; Park, J.H.; Xie, X.P.; Gao, C.; Zhao, N.N. Fuzzy adaptive event-triggered control for a class of uncertain nonaffine nonlinear systems with full state constraints. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y. Neural network adaptive finite-time control of stochastic nonlinear systems with full state constraints. Asian J. Control 2021, 23, 1728–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishro, A.; Shahrokhi, M.; Mohit, M. Adaptive neural quantized control for fractional-order full-state constrained non-strict feedback systems subject to input fault and nonlinearity. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 166, 112977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Zeng, P. Adaptive finite-time neural network control for nonlinear stochastic systems with state constraints. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 215, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Meng, R.; Li, K.; Ning, P. Dynamic event-based adaptive finite-time tracking control for nonlinear stochastic systems under state constraints. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 7201–7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.B.; Park, J.H.; Xie, X.P.; Zhao, N.N. Adaptive fuzzy tracking control for a class of uncertain switched nonlinear systems with full-state constraints and input saturations. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 51, 6054–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouari, F.; Ibeas, A.; Boulkroune, A.; Jinde, C.A.O.; Arefi, M.M. Neural network controller design for fractional-order systems with input nonlinearities and asymmetric time-varying Pseudo-state constraints. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 144, 110742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wen, G. Adaptive neural network control for time-varying state constrained nonlinear stochastic systems with input saturation. Inf. Sci. 2020, 527, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, B.; Zong, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, X. Command filter-based adaptive neural finite-time control for stochastic nonlinear systems with time-varying full-state constraints and asymmetric input saturation. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2022, 53, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Ding, S.; Park, J.H.; Ma, L. Adaptive fuzzy control for nontriangular stochastic high-order nonlinear systems subject to asymmetric output constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 52, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, K.; Lin, C. Robust adaptive fuzzy tracking control for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with input constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2013, 43, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Zhang, W. Adaptive fuzzy control for pure-feedback stochastic nonlinear systems with unknown dead zone outputs. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2018, 49, 2981–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Liu, Z.; Liang, H.; Li, H. Pinning-based neural control for multiagent systems with self-regulation intermediate event-triggered method. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 7252–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, D.; Wu, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, H.; Shi, Y. Event-based adaptive sliding-mode containment control for multiple networked mechanical systems with parameter uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.