Decoding Mouse Visual Tasks via Hierarchical Neural-Information Gradients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Hierarchical Processing in/for the Mouse Visual System

2.2. Fine-Coarse-Grained and Graph-Based Methods for Brain Network Decoding

2.3. Hippocampal Roles and Our Presented Work in Visual Decoding and Beyond

3. Method

3.1. Pre-Knowledge

3.1.1. Mapper Algorithm

3.1.2. Maximum Likelihood Estimate for PCA (ada-PCA)

3.1.3. Random Baseline in Mouse Visual Classification

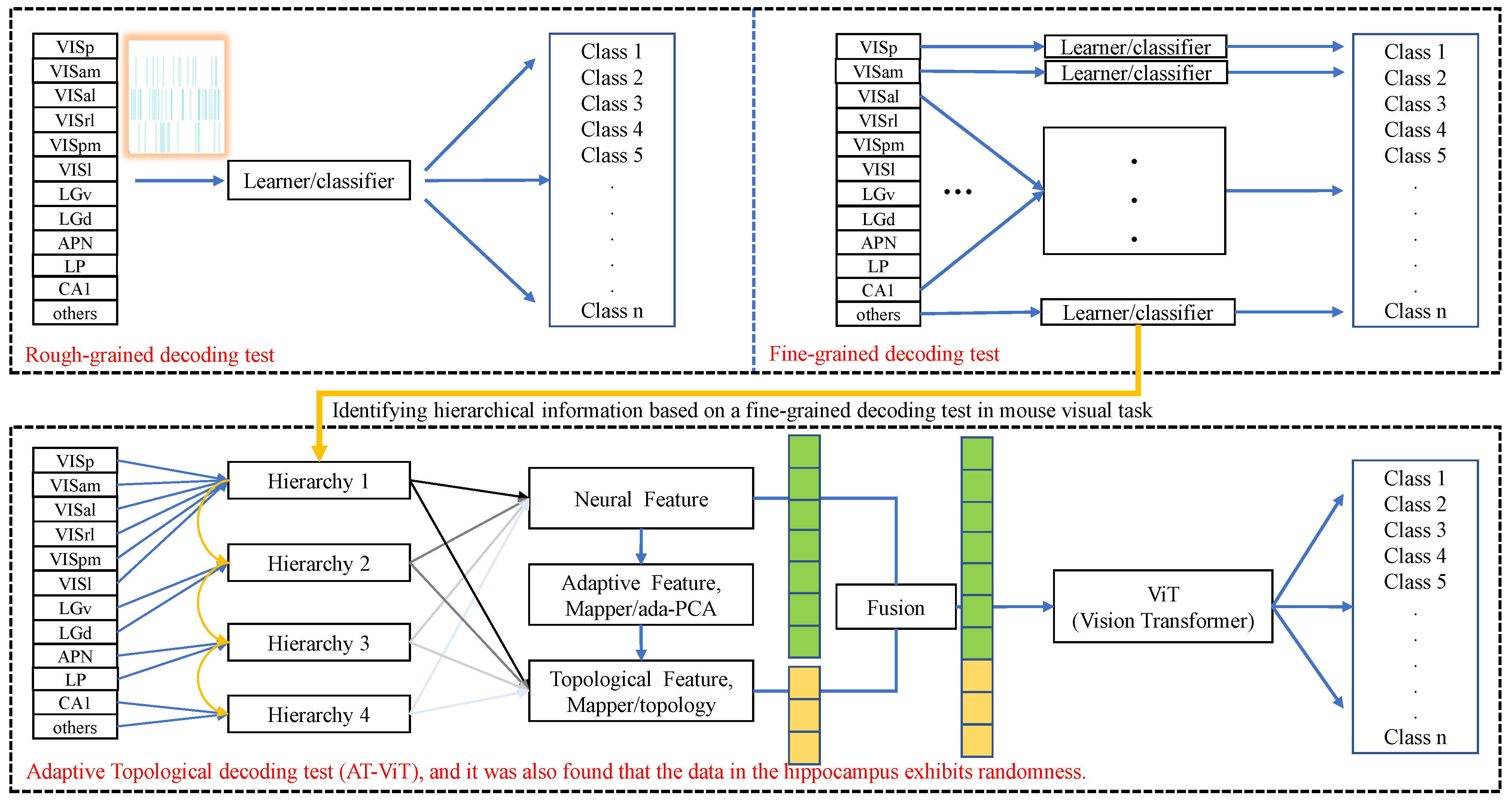

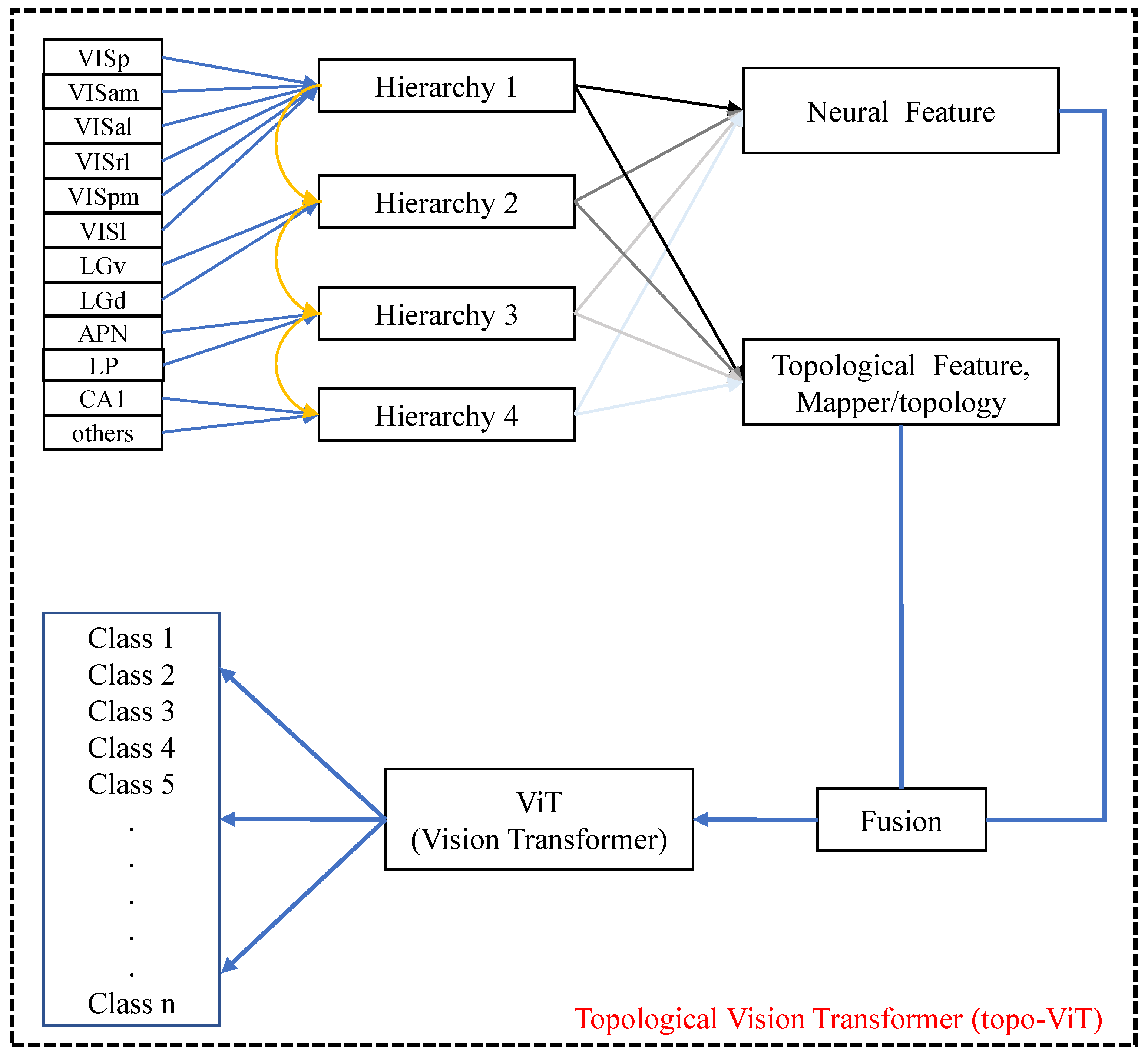

3.2. Adaptive Topology Vision Transformer (AT-ViT)

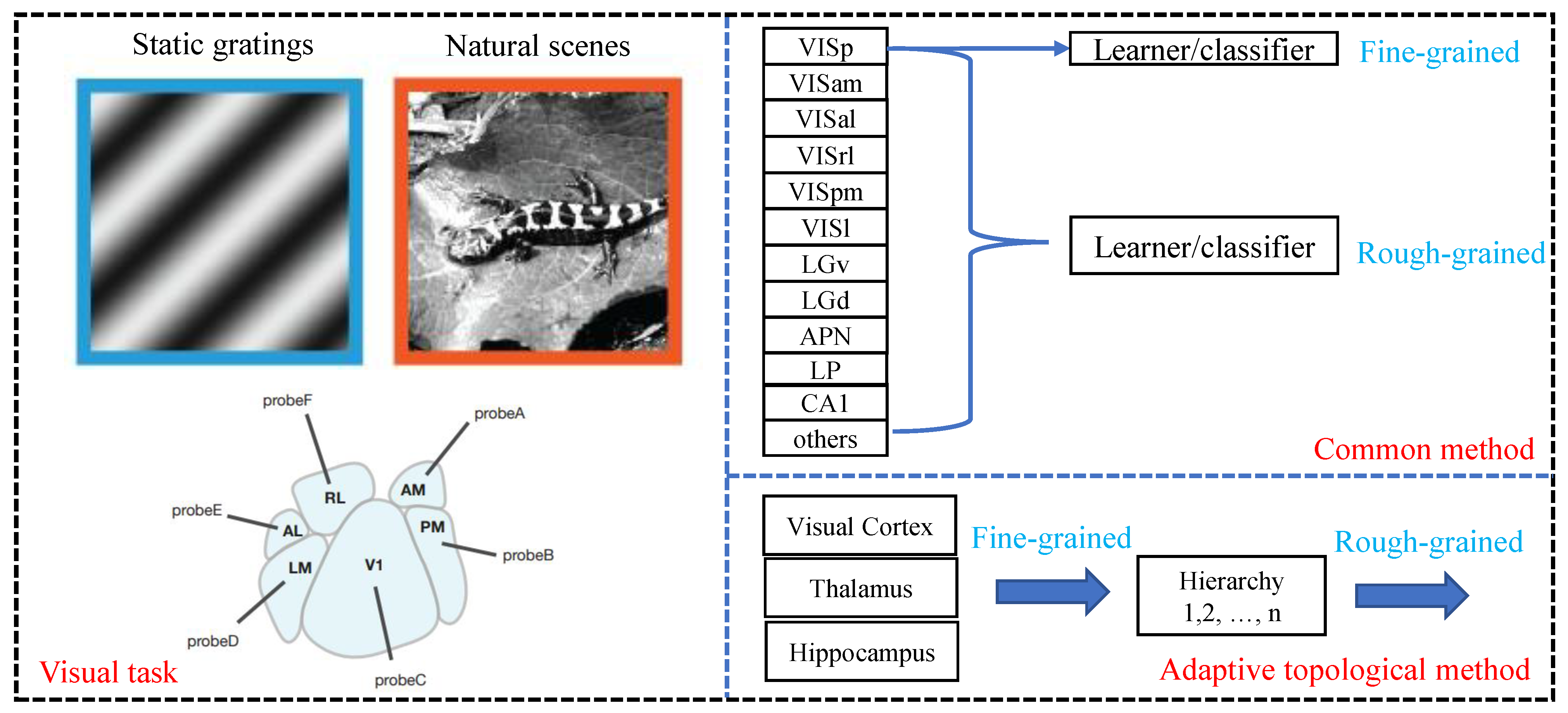

3.2.1. Coarse-Grained Decoding Tests

3.2.2. Fine-Grained Decoding Tests

3.2.3. Adaptive Topological Decoding

3.2.4. Quantitative Construction of the Information Hierarchy

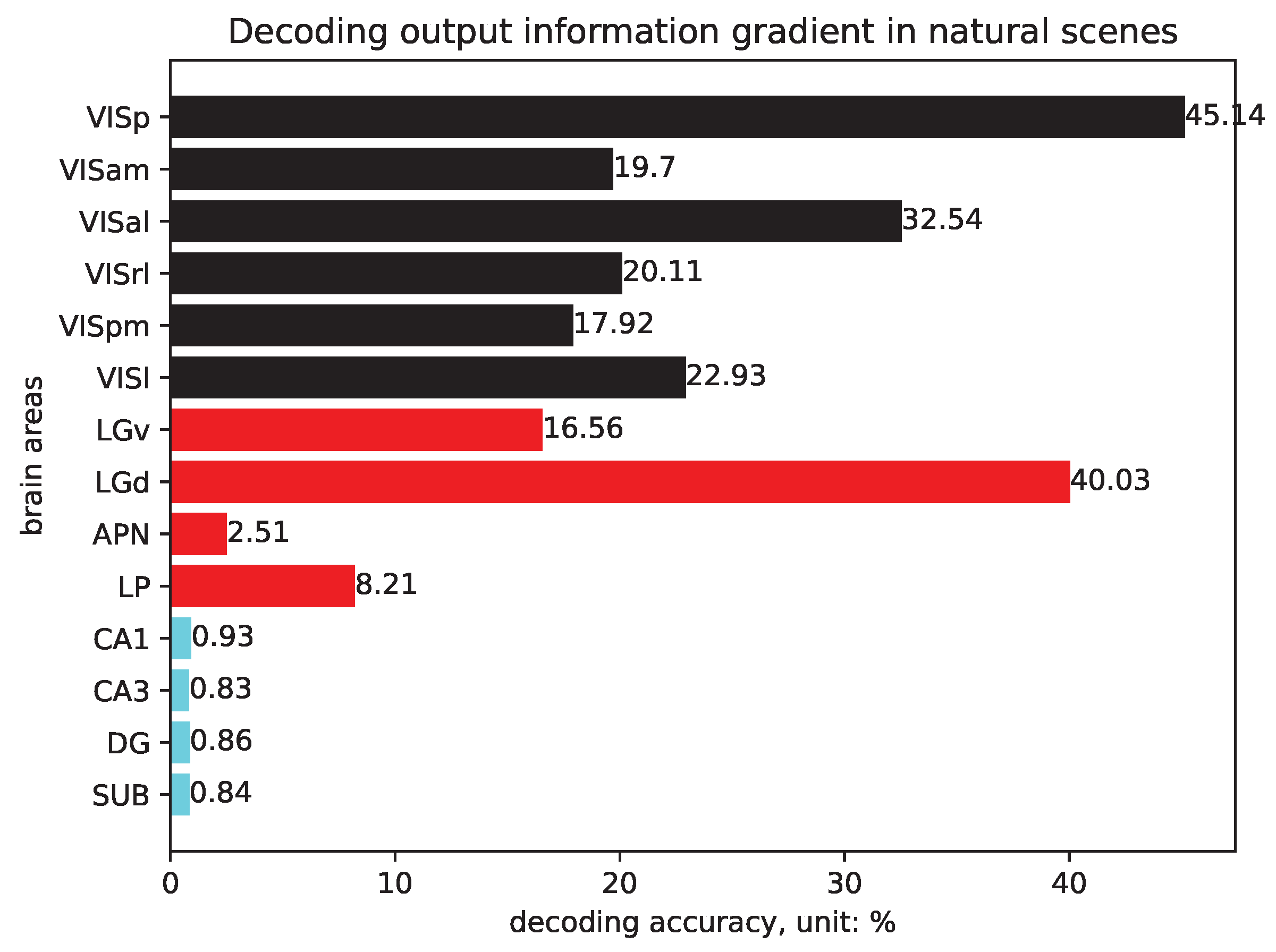

- For each session s and each brain area r, train an SVM and compute classification accuracy .

- For each area r, compute its cross-session average accuracywhere S is the number of sessions.

- Compute the normalized information scorewhere is the random baseline, and VISp consistently shows the highest .

- Sort all recorded areas by in descending order.

- Group them into n cumulative hierarchies using fixed relative thresholds . Hierarchy 1 contains areas with . Each higher hierarchy n () cumulatively includes all areas from lower hierarchies plus the new areas falling into the corresponding interval.

| Algorithm 1 AT-ViT Algorithm. |

Input: brain’s visual data Parameter: , , , , 1 × 10−3, , , . Output: AT-ViT model M

|

3.3. Algorithms and Listings

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset and Metric

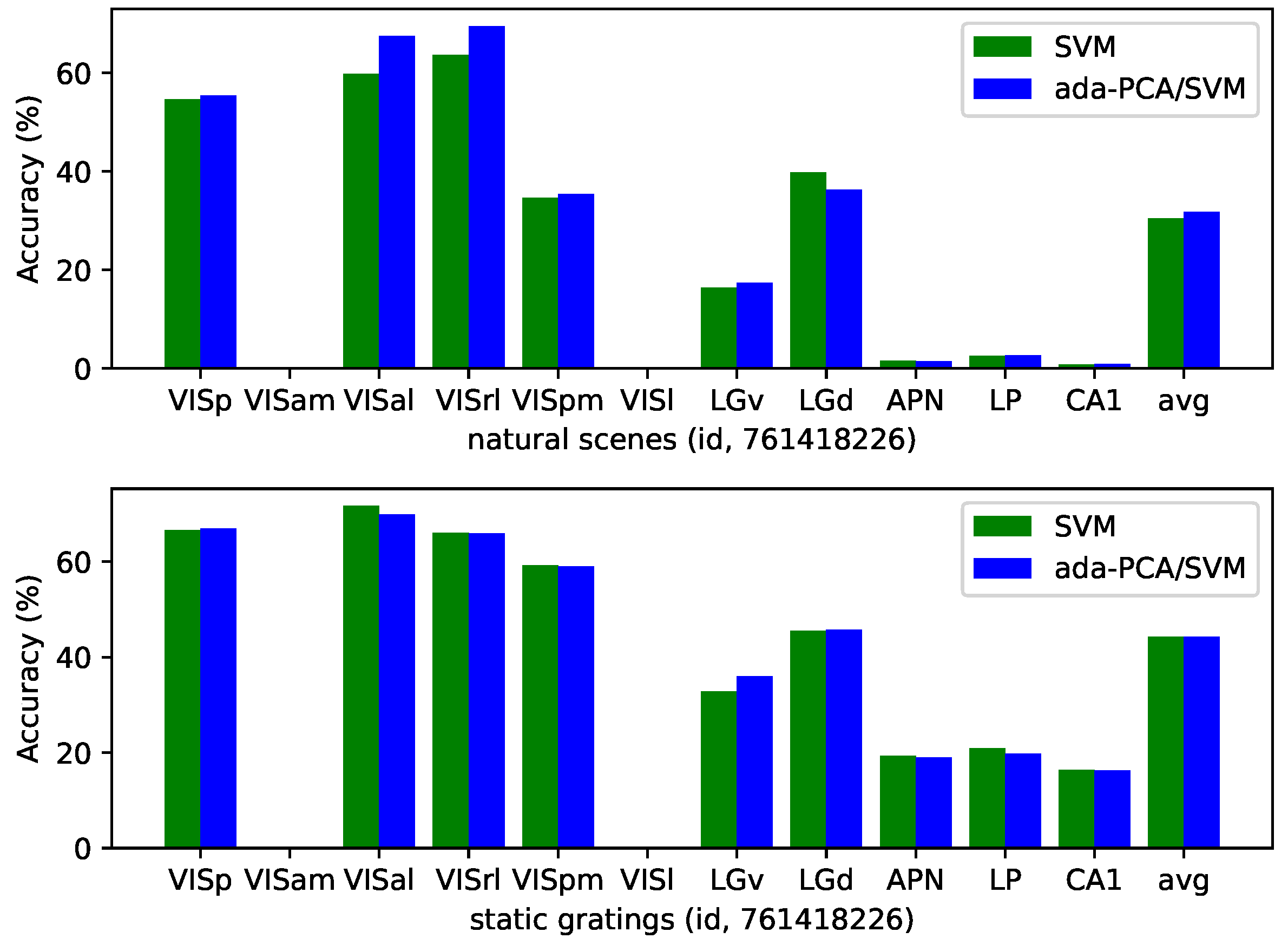

4.2. ada-PCA/SVM Decoding in Visual Tasks

4.3. Fine-Grained Decoding Tests in Visual Tasks

4.4. Brain Hierarchy Setting and Experiment

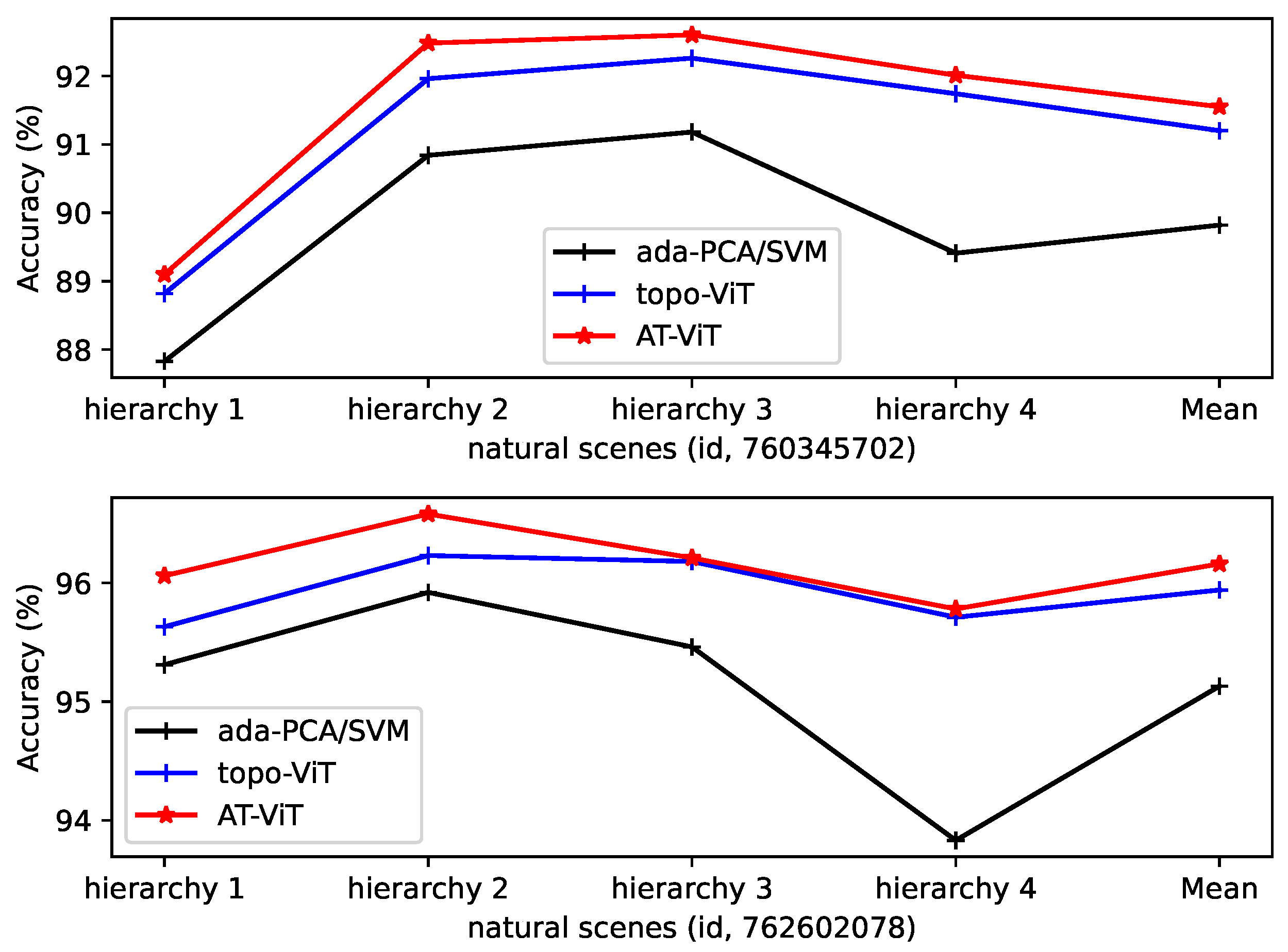

4.5. Decoding and Analyzing in Hierarchical Information Gradients

| Session_id (ada-PCA/SVM) | Hierarchy 1 | Hierarchy 2 | Hierarchy 3 | Hierarchy 4 | Mean (nat_Scenes/Static_Gra) ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 760345702 | 87.83/83.19 | 90.84/84.77 | 91.18/84.65 | 89.41/82.24 | 89.82 (0%)/83.71 (0%) |

| 762602078 | 95.31/85.21 | 95.92/85.42 | 95.46/84.11 | 93.83/82.06 | 95.13 (0%)/84.20 (0%) |

| session_id (topo-ViT) | |||||

| 760345702 | 88.82/84.23 | 91.96/86.49 | 92.26/87.07 | 91.74/85.32 | 91.20 (1.54%)/85.78 (2.47%) |

| 762602078 | 95.63/87.43 | 96.23/86.84 | 96.18/86.98 | 95.71/86.53 | 95.94 (0.85%)/86.95 (3.27%) |

| session_id (AT-ViT) | |||||

| 760345702 | 89.10/84.51 | 92.48/86.04 | 92.60/86.57 | 92.01/85.97 | 91.55 (1.93%)/85.77 (2.46%) |

| 762602078 | 96.06/87.20 | 96.58/87.44 | 96.21/87.12 | 95.78/86.26 | 96.16 (1.08%)/87.01 (3.34%) |

5. Discussion

5.1. The Proposed Model and Its Theoretical Discussion

5.2. Reinterpreting the Role of Hippocampal Signals in Visual Decoding

5.3. Generalizability and Broader Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Beech, P.; Yin, Z.; Jia, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, J.K. Decoding dynamic visual scenes across the brain hierarchy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubel, D.; Wiesel, T. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat’s visual cortex. J. Physiol. 1962, 160, 106–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, F.; Gregory, K.M.; Blanks, R.H.I.; Giolli, R.A. Projections from visual areas of the cerebral cortex to pretectal nuclear complex, terminal accessory optic nuclei, and superior colliculus in macaque monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995, 363, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giber, K.; Slézia, A.; Bokor, H.; Bodor, Á.L.; Ludányi, A.; Katona, I.; Acsády, L. Heterogeneous output pathways link the anterior pretectal nucleus with the zona incerta and the thalamus in rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007, 506, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk-Browne, N.B. The Hippocampus as a Visual Area Organized by Space and Time: A Spatiotemporal Similarity Hypothesis. Vis. Res. 2019, 165, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Dai, W.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Sun, X.; Wang, G.; Li, L.; et al. Nonuniform and pathway-specific laminar processing of spatial frequencies in the primary visual cortex of primates. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Dai, W.; Yang, Y.; Han, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, D. Laminar Subnetworks of Response Suppression in Macaque Primary Visual Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 7436–7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Dai, W.; Yang, G.; Han, C.; Wu, Y.; Xing, D. Coding strategy for surface luminance switches in the primary visual cortex of the awake monkey. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamanlis, D.; Schreyer, H.M.; Gollisch, T. Retinal Encoding of Natural Scenes. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2022, 8, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, K.H.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z. Neural Encoding and Decoding with Deep Learning for Dynamic Natural Vision. Cereb. Cortex 2018, 28, 4136–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ma, S.; Huang, T.; Liu, J.K. Reconstruction of natural visual scenes from neural spikes with deep neural networks. Neural Netw. 2020, 125, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Dong, P.; Kim, C.M.; Jang, H. Decoding Neural Responses in Mouse Visual Cortex through a Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary, 14–19 July 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wu, X. Multi-Scale Spatio-Temporal Fusion With Adaptive Brain Topology Learning for fMRI Based Neural Decoding. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegle, J.; Jia, X.; Durand, S.; Gale, S.; Bennett, C.; Graddis, N.; Heller, G.; Ramirez, T.; Choi, H.; Luviano, J.; et al. Survey of spiking in the mouse visual system reveals functional hierarchy. Nature 2021, 592, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Mihalas, S.; Hirokawa, K.E.; Whitesell, J.D.; Choi, H.; Bernard, A.; Bohn, P.; Caldejon, S.; Casal, L.; Cho, A.; et al. Hierarchical organization of cortical and thalamic connectivity. Nature 2019, 575, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.D.; Wang, Q.; Ji, W.; Meier, A.M.; Kennedy, H.; Knoblauch, K.; Burkhalter, A. Hierarchical and nonhierarchical features of the mouse visual cortical network. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 106–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, S.A.; Sinz, F.H.; Muhammad, T.; Froudarakis, E.; Cobos, E.; Walker, E.Y.; Reimer, J.; Bethge, M.; Tolias, A.; Ecker, A.S. How Well Do Deep Neural Networks Trained on Object Recognition Characterize the Mouse Visual System? In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz, N.A.; Zatka-Haas, P.; Carandini, M.; Harris, K.D. Distributed coding of choice, action and engagement across the mouse brain. Nature 2019, 576, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turishcheva, P.; Fahey, P.G.; Vystrčilová, M.; Hansel, L.; Froebe, R.; Ponder, K.; Qiu, Y.; Willeke, K.F.; Bashiri, M.; Baikulov, R.; et al. Retrospective for the Dynamic Sensorium Competition for predicting large-scale mouse primary visual cortex activity from videos. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Globerson, A., Mackey, L., Belgrave, D., Fan, A., Paquet, U., Tomczak, J., Zhang, C., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 118907–118929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudelt, L.; Marx, D.G.; Spitzner, F.P.; Cramer, B.; Zierenberg, J.; Priesemann, V. Signatures of hierarchical temporal processing in the mouse visual system. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Margrie, T.W.; Clopath, C. Movie reconstruction from mouse visual cortex activity. eLife 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. A dynamic graph convolutional neural network framework reveals new insights into connectome dysfunctions in ADHD. NeuroImage 2022, 246, 118774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. Classification of Brain Disorders in rs-fMRI via Local-to-Global Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2023, 42, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Ye, J.C.; Kim, J.J. Learning Dynamic Graph Representation of Brain Connectome with Spatio-Temporal Attention. In Proceedings of the 34rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021), Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 4314–4327. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gazzar, A.; Thomas, R.M.; van Wingen, G. Dynamic adaptive spatio-temporal graph convolution for fMRI modelling. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging: 4th International Workshop, Strasbourg, France, 27 September 2021; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Dai, W.; Zhu, Y.; Kan, X.; Gu, A.A.; Lukemire, J.; Zhan, L.; He, L.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C. BrainGB: A Benchmark for Brain Network Analysis with Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wei, X.; Carlisle, N.B.; Keller, C.J.; Oathes, D.J.; Fonzo, G.A.; Zhang, Y. Deep graph learning of multimodal brain networks defines treatment-predictive signatures in major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 3963–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livezey, J.A.; Glaser, J.I. Deep learning approaches for neural decoding across architectures and recording modalities. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1577–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemla, R.; Basu, J. Hippocampal function in rodents. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017, 43, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Q.Q. Plugging in to Human Memory: Advantages, Challenges, and Insights from Human Single-Neuron Recordings. Cell 2019, 179, 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Mémoli, F.; Carlsson, G.E. Topological methods for the analysis of high dimensional data sets and 3d object recognition. Eurograph. Symp. Point-Based Graph. 2007, 2, 90. [Google Scholar]

- van Veen, H.J.; Saul, N.; Eargle, D.; Mangham, S.W. Kepler Mapper: A flexible Python implementation of the Mapper algorithm. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1802.03426v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minka, T.P. Automatic Choice of Dimensionality for PCA. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 13, Denver, CO, USA, 1–2 December 2000; pp. 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, R.E.; Raftery, A.E. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995, 90, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D. Probable networks and plausible predictions-a review of practical Bayesian methods for supervised neural networks. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 1995, 6, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, T.; Dai, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Xing, D. Neuronal representation of visual working memory content in the primate primary visual cortex. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| id (nat) | VISp | VISam | VISal | VISrl | VISpm | VISl | LGv | LGd | APN | LP | CA1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 761418226 | 54.69 | – | 59.85 | 63.71 | 34.62 | – | 16.44 | 39.78 | 1.60 | 2.52 | 0.81 |

| 763673393 | 46.67 | 32.03 | – | 16.17 | – | 12.18 | 0.62 | 66.29 | 5.11 | 2.44 | 0.79 |

| 773418906 | 30.94 | 10.17 | 43.26 | 9.19 | – | – | – | – | 3.18 | – | 0.76 |

| 791319847 | 51.70 | 19.75 | 20.96 | 17.50 | 12.64 | 16.87 | 11.73 | 2.98 | – | 2.07 | 0.97 |

| 797828357 | 32.17 | 7.12 | 3.72 | 5.60 | 6.50 | 14.67 | – | – | 3.38 | 8.07 | 0.74 |

| 798911424 | 49.53 | 21.65 | 42.77 | 16.55 | – | 39.56 | 37.45 | – | 0.82 | 19.53 | 1.71 |

| 799864342 | 50.29 | 27.48 | 24.66 | 12.08 | – | 31.36 | – | 51.08 | 0.94 | 14.62 | 0.76 |

| avg | 45.14 | 19.70 | 32.54 | 20.11 | 17.92 | 22.93 | 16.56 | 40.03 | 2.51 | 8.21 | 0.93 |

| std | 8.88 | 8.81 | 18.22 | 18.25 | 12.07 | 10.66 | 13.36 | 23.37 | 1.53 | 6.74 | 0.32 |

| avg-ref | 44.36 | 18.92 | 31.76 | 19.33 | 17.14 | 22.15 | 15.78 | 39.25 | 1.73 | 7.43 | 0.15 |

| 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.003 | |

| 761418226 | 66.60 | – | 71.72 | 66.00 | 59.19 | – | 32.80 | 45.51 | 19.29 | 20.96 | 16.36 |

| 763673393 | 60.88 | 52.02 | – | 43.60 | – | 31.49 | 14.80 | 60.67 | 25.99 | 19.71 | 14.83 |

| 773418906 | 54.69 | 36.89 | 63.27 | 32.72 | – | – | – | – | 20.31 | – | 16.21 |

| 791319847 | 65.15 | 51.99 | 42.23 | 59.29 | 38.44 | 41.76 | 31.72 | 18.49 | – | 20.72 | 16.82 |

| 797828357 | 48.98 | 36.87 | 23.35 | 31.17 | 25.59 | 31.99 | – | – | 22.95 | 21.50 | 16.85 |

| 798911424 | 65.83 | 60.16 | 68.74 | 43.61 | – | 58.40 | 47.17 | – | 16.66 | 34.33 | 20.29 |

| 799864342 | 69.80 | 48.08 | 60.16 | 56.48 | – | 58.86 | – | 53.52 | 16.83 | 37.71 | 17.30 |

| avg | 61.70 | 47.67 | 54.91 | 47.55 | 41.07 | 44.50 | 31.62 | 44.55 | 20.34 | 25.82 | 16.95 |

| std | 6.87 | 8.43 | 16.97 | 12.41 | 13.84 | 12.11 | 11.47 | 15.97 | 3.31 | 7.30 | 1.54 |

| avg-ref | 45.03 | 31.00 | 38.24 | 30.88 | 24.40 | 27.83 | 14.95 | 27.88 | 3.67 | 9.15 | 0.28 |

| 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.006 |

| Hierarchy n, Id | VISp | VISam | VISal | VISrl | VISpm | VISl | LGv | LGd | APN | LP | CA1 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 760345702 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 762602078 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, J.; Feng, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, J. Decoding Mouse Visual Tasks via Hierarchical Neural-Information Gradients. Mathematics 2026, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010031

Feng J, Feng X, Luo Y, Li J. Decoding Mouse Visual Tasks via Hierarchical Neural-Information Gradients. Mathematics. 2026; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Jingyi, Xiang Feng, Yong Luo, and Jing Li. 2026. "Decoding Mouse Visual Tasks via Hierarchical Neural-Information Gradients" Mathematics 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010031

APA StyleFeng, J., Feng, X., Luo, Y., & Li, J. (2026). Decoding Mouse Visual Tasks via Hierarchical Neural-Information Gradients. Mathematics, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/math14010031