Abstract

The complex analytic continuation can be developed to enable the Gauss-Krüger projection to be non-zonal and non-singular in polar regions. The series expansion of the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection in terms of third flattening has been derived by using a computer algebra system, leading to a substantial simplification of the final formulas without compromising accuracy compared with the series expansion in terms of eccentricity. Therefore, the non-zonal formulas of the Gauss-Krüger projection in term of third flattening have been expressed, and the non-zonal and the non-singular formulas of the Gauss-Krüger projection has been derived by the conformal colatitude. With respect to the mapping of 4 high-latitude regions (Finland, Sweden, Norway and Alaska) and its isopleth map, it was verified that the non-zonal and the non-singular algorithm of the Gauss-Krüger projection had high precision and minimal distortion in polar regions. The method presented a meaningful supplement to the existing Gauss–Krüger projection family.

Keywords:

Gauss-Krüger projection; polar regions; non-zonal and non-singular; computer algebra system MSC:

86A30

1. Introduction

Polar regions have garnered increasing international attention due to their significant commercial, scientific, and strategic importance. With the ongoing impact of global warming, the reduction of sea ice and iceberg threats in the Arctic has facilitated the emergence of Arctic sea routes connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. These routes are anticipated to become vital maritime corridors with substantial economic and strategic value [1]. Similarly, the Antarctic region possesses abundant natural resources, further underscoring the global interest in polar areas. The selection of an appropriate map projection is critical for supporting marine science and engineering [2]. While the Transverse Mercator and Gnomonic projections are commonly used in polar regions, they typically assume a spherical Earth model. Thus, there is a clear need for accurate projection methods that incorporate the ellipsoidal nature of the Earth’s surface [3,4].

The Gauss-Krüger projection is a widely employed conformal projection, extensively used in large-scale topographic mapping due to its high accuracy [5]. It projects a reference ellipsoid onto a plane where the equator and central meridian remain straight lines, and scale remains constant along the central meridian. All other meridians and parallels are represented as complex curves, maintaining right-angle intersections [6]. However, the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection is generally limited to narrow zones—typically within 3–6° of a central meridian—to maintain millimeter-level accuracy. This zonal approach is cumbersome for practical applications, particularly in polar regions where the projection exhibits a singularity at the poles.

Significant advancements have been made in the development of the Gauss-Krüger projection. Although Gauss provided limited details of his original work, later contributions by Schreiber [7,8] and Krüger [9] refined the theoretical foundations. Karney [10] extended Krüger’s series expansions to the 8th order, achieving high-precision results. To overcome zonal limitations, Li [11] introduced a complex-number formulation of the Gauss-Krüger projection, which provides simplicity and accuracy over a broad longitudinal range. However, this method still suffers from a singularity in the isometric latitude at the poles. Similarly, Guo [12] advanced the projection but did not provide a systematic solution for polar regions.

With the growing importance of polar studies in fields such as navigation, remote sensing, marine science and engineering [13,14,15], there is a pressing need for a conformal projection that is both singularity-free and applicable to ellipsoidal models. Many existing polar projections assume a spherical Earth or rely on complex ellipsoid-to-sphere transformations, which can be computationally intensive and less accurate [16,17].

Computer algebra systems have become indispensable in modern geodesy for deriving high-order series expansions and simplifying complex symbolic expressions [18,19,20]. Using software such as Mathematica, it is possible to develop high-precision formulations that would be infeasible through manual calculation alone. In this study, we leverage computer algebra to derive non-singular, non-zonal formulas for the Gauss-Krüger projection in polar regions based on ellipsoidal parameters.

Building on the foundation of previous work [21], this paper provides a systematic analysis of the limitations inherent in the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection and evaluates the practical utility of the proposed formulas. We reevaluate the series expansions using both eccentricity () and third flattening (), demonstrating that the series expansions with respect to third flattening yield simpler coefficients without sacrificing accuracy. By introducing the concept of complex conformal colatitude, we derive a non-singular formulation valid even at the poles. The resulting method is implemented using computer algebra, enabling cartography and navigation in polar regions. This approach offers a practical and accurate solution for marine and polar applications, providing significant value for mid- to high-latitude countries and regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamentals of the Ellipsoid and the Traditional Gauss-Krüger Projection

In geodetic science, the reference ellipsoid is defined as a mathematical surface generated by rotating an ellipse about its minor axis. This biaxial ellipsoid is characterized by its semi-major axis and semi-minor axis , where . These fundamental parameters give rise to the following key geometric constants:

These constants are derived from the fundamental parameters () and are interrelated through the following defining equations:

Generally, the Gauss-Krüger projection can be expressed in the reference ellipsoid. Within this framework, the planar coordinates () of a given point on the ellipsoid at geodetic latitude are formally defined as functions of the longitude difference () from the central meridian (), expressed through a real power series expansion in :

where the meridian distance (), the radius of curvature in the prime vertical (), the auxiliary functions and are defined as follows:

It is worth noting that although third flattening has been presented much earlier in 1837 by the German geodetic shcolar Friedrich Bessel [22], the systematic application was historically constrained by manual calculation. Now it has actively been incorporated into various geodetic problems [23,24], which has demonstrated that reformulating classical expressions with third flattening leads to notably simpler coefficient structures. Therefore, the meridian distance () with respect to the third flattening can be obtained as follows:

A comparative analysis reveals a significant advantage of series expansions based on third flattening () over those using the eccentricity (). The coefficients in the -based expansions are markedly simpler, with several higher-order terms vanishing entirely, leading to a substantial simplification of the final formulas without compromising accuracy. Specifically, certain coefficients originally reaching 7-digit values are now reduced to 4 or even single-digit values. Furthermore, 9 high-order terms are eliminated, resulting in a simple, compact, and computationally efficient expression.

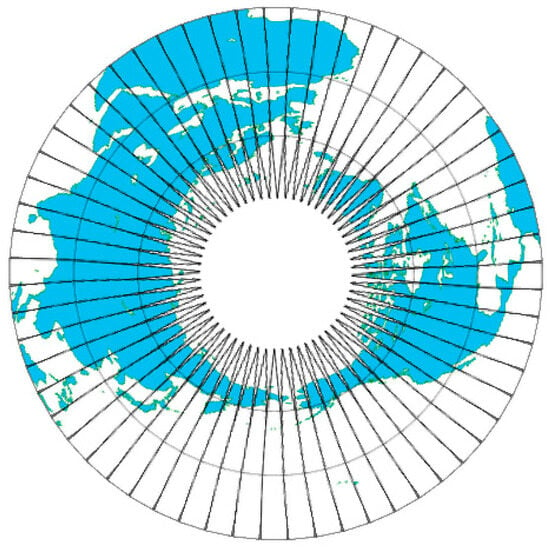

The Gauss-Krüger real power series expansions have been developed by Xiong (1988) [25]. While the methodological approach differs from Gauss’s original technique, Xiong’s work provides valuable insight into the application of Taylor’s theorem for this purpose. However, a fundamental limitation of this traditional projection is exposed in polar regions. As illustrated in Figure 1, the Gauss-Krüger mapping is effectively broken at high latitudes due to its zonal and iterative formulation.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the discontinuity and singularity in the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection at the pole: the land (blue) and sea (white) at the pole were magnified.

This breakdown directly leads to the projection’s severely limited utility for polar applications. Consequently, despite its millimeter-level accuracy in narrow bands at lower latitudes, the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection is unsuitable for polar navigation and cannot be effectively applied in the Earth’s polar regions.

The limitations of the traditional Gauss-Krüger projection can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Singularity at the Pole: The projection contains terms that become undefined (singular) at the pole, specifically where the term tan (B) tends to infinity as the geodetic latitude B approaches 90°.

- (2)

- Zonal Inconvenience: The formulation is inherently zonal, requiring distinct calculations for regions typically less than 6° wide on either side of a central meridian, as the series is expanded in terms of the longitude difference (l)

- (3)

- Fragmented Polar Mapping: The projection yields a discontinuous and fragmented map in polar regions, making it impractical and unreliable for navigation and charting purposes near the poles.

- (4)

- Computational Inefficiency: The formulas necessitate the separate calculation of latitude and longitude, resulting in a less efficient computational process compared to unified methods.

In contrast to the traditional Gauss–Krüger projection, the methodology presented in this paper adopts the pole as the projection center, resulting in a unique and consistent origin for polar mapping. This approach is characterized by its non-zonal applicability and the elimination of singularities at the pole, addressing fundamental limitations of the conventional zonal formulation. As illustrated in Figure 2, the proposed projection adheres to the fundamental principle of the Gauss–Krüger framework, which is centered on the pole, while significantly reducing distortion in polar regions.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss-Krüger projection: the model utilizes geodetic latitude (), the longitude difference (), the geocentric latitude (), and the conformal latitude () for calculation.

The geometric configuration shown above underscores the continuity and uniformity of the coordinate system across the polar area, enabling seamless integration of geodetic data without the discontinuities inherent in the traditional zonal approach. This structural advantage is particularly vital for applications requiring consistent spatial referencing in high-latitude environments.

2.2. A Formulation of the Gauss-Krüger Projection by Complex Function

The non-iterative complex formulation of the Gauss-Krüger projection has been derived from the complex isometric latitude , which serves as an analytic extension of the conventional real variable. The projection coordinates are then obtained through a direct functional relationship with the complex conformal latitude , leading to the following expression:

where the complex isometric latitude w is defined by

The complex isometric latitude, , is an analytic function in the complex plane, satisfies the Cauchy-Riemann conditions within the geodetic latitude of the reference ellipsoid, then the isometric latitude can be defined by:

The straightforward procedures expressed by new formulas reveal the mapping procedures and intrinsic properties of the Gauss-Krüger projection. However, a critical limitation arises in polar regions. When the geodetic latitude approaches 90°, the isometric latitude becomes singular. This singularity is consequently inherited by Equations (17) and (19), rendering them invalid and thus preventing the direct application of this formulation at the poles.

We should note that, following the same rigorous methodology, the complex function of the Gauss-Krüger projection can be expressed in term of third flattening:

A notable advantage of the series expansion in term of third flattening is the simplicity of its coefficients. The elimination of certain term coefficients significantly streamlines the resulting formulas. Specifically, certain coefficients originally reaching 8-digit values are now reduced to 3 or even single-digit values. Furthermore, 3 high-order terms are eliminated, resulting in a simple, compact, and computationally efficient expression. This concise expression of the Gauss-Krüger projection provides the foundation for solving singularity problems.

2.3. A Non-Zonal and Non-Singular Formulation of the Gauss-Krüger Projection for Polar Regions

To address this singularity in polar regions, a fundamental reparameterization is required. Following Equation (21), the meridian distance is expressed as a function of the conformal latitude , measuring from the equator to a given point.

where the coefficients are identical to those defined in Equation (22), thus avoiding redundancy in their repeated specification here.

The conformal latitude is formally defined by the following relation:

The conformal colatitude is therefore defined in terms of the conformal latitude as follows:

Substituting the expression for from Equation (25) into Equation (23) yields a definition of the meridian distance in terms of the new variable:

Substitution of Equation (24) into Equation (25) yields the expression for the conformal colatitude:

By applying the following mathematical identities:

Equation (24) may be expressed in the equivalent form:

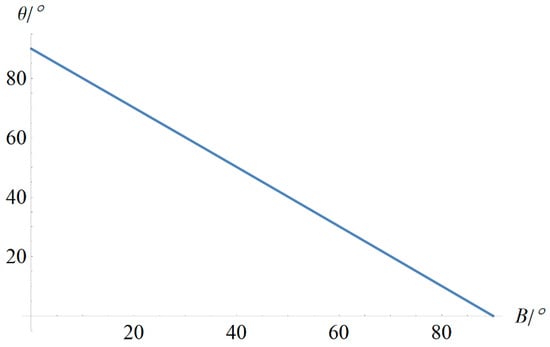

The substitution of Equation (28) into Equation (27) reveals a key insight: when the geodetic latitude = 90°, the conformal colatitude equals 0, thereby eliminating the mathematical singularity that occurs at the pole in the traditional formulation. This is further illustrated in Figure 3, which plots the variation of the conformal colatitude against the geodetic latitude. The curve confirms that is a monotonically decreasing function of over the entire geodically, meaningful range from −90° to 90°, and exhibits no singular behavior. Thus, the introduction of the conformal colatitude successfully resolves the long-standing singularity problem that has limited the polar application of the Gauss-Krüger projection.

Figure 3.

The functional dependence of the conformal colatitude θ on the geodetic latitude B.

Building upon the foundation of the complex-variable formulation for the Gauss-Krüger projection, we can naturally extend this methodology to derive a non-singular solution for the polar case:

The complex formulas for the non-singular formulation are obtained by substituting Equation (30) into Equation (26) and replacing the meridian distance . In this formulation, and represent the abscissa and ordinate of the Gauss-Krüger projection, respectively. To center the map on the North Pole, a coordinate translation is performed. This involves subtracting a constant value. Specifically, it is a value of one-quarter of the meridian distance () from the -axis ordinate. This operation effectively shifts the origin of the coordinate system from the equator to the North Pole. The purpose of this adjustment is purely for cartographic convenience in polar representation. This adjustment leads to the final definition of the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss-Krüger projection:

where the coefficients are identical to those defined in Equation (22).

The proposed formulation adheres to the fundamental rules of the Gauss-Krüger projection, as verified below:

- (1)

- Satisfaction of the first rule: When the longitude difference l = 0°, the central meridian remains as straight.

- (2)

- Satisfaction of the second rule: The formulation is derived using complex function theory. The coordinate functions satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations within the principal value range, being single-valued and analytic. This mathematically guarantees that the projection is conformal, thereby satisfying the second rule.

- (3)

- Satisfaction of the third rule: When l = 0°, the scale along the central meridian is 1.

3. Analysis and Application

The proposed non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection is the product of a rigorous mathematical derivation, the correctness of which can be verified through multiple mathematical examples. While numerous advancements have been made to the Gauss–Krüger projection, many existing methods rely on iterative or zonal computations, which increase complexity and limit practical utility. In contrast, the simple, explicit formulas of the present method enable straightforward implementation within a computer algebra system, offering significant practical value for geodetic and cartographic applications.

Many conventional map projections for polar regions are constructed on a spherical reference surface for simplicity. However, such approaches are inherently less rigorous than those based on an ellipsoidal model. The non-zonal, non-singular formulation derived in this work is strictly ellipsoidal, which traditionally posed considerable challenges for manual computation and mapping. Although some ellipsoidal projections are easier to map, they are often unsuitable for precise geodetic work. This tension is now resolved through the application of a computer algebra system. The computations presented herein were performed with respect to the GRS80 reference ellipsoid.

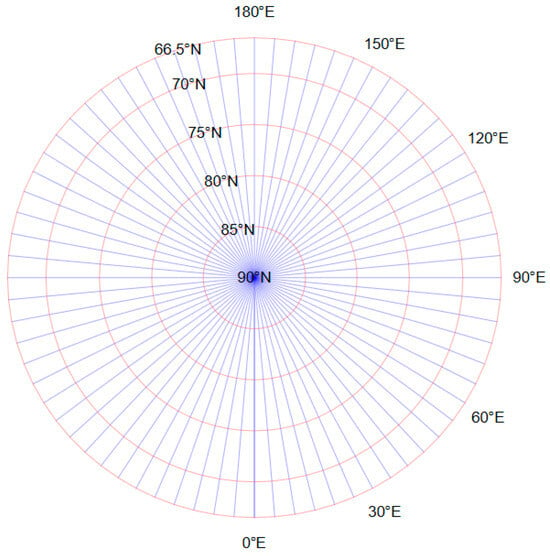

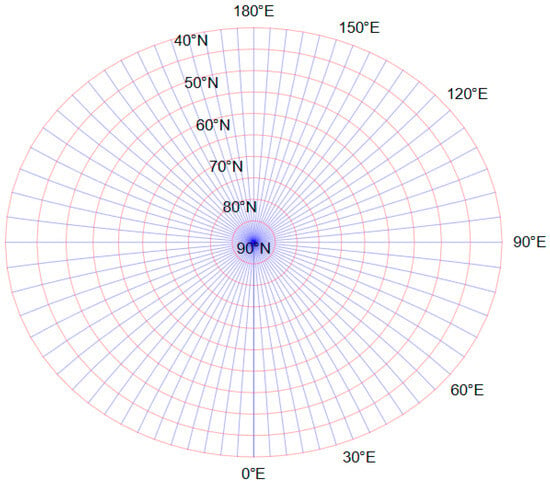

The graticule generated by the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection is visually presented in Figure 4, which illustrates the arrangement of meridians and parallels in polar regions. In the figure, parallels are depicted in red, while meridians are shown in blue.

Figure 4.

Graticule geometry of the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss-Krüger projection in polar regions: parallels (red) and meridians (blue).

Owing to the minimal scale distortion characteristic of the projection in polar areas, the parallels appear as approximately circular arcs, and the meridians exhibit near-straight trajectories radiating from the pole. A more detailed examination of mid-high latitude regions, as provided in Figure 5, reveals the nuanced behavior of the graticule: while parallels maintain their curved nature, meridians only remain perfectly straight along the central meridian (0°) and its anti-meridian (±180°), adopting curved profiles at other longitudes.

Figure 5.

Graticule geometry of the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss-Krüger projection in mid-high latitude regions: parallels (red) and meridians (blue).

This geometric representation marks a significant departure from conventional mappings where the pole may be distorted into a linear feature. Instead, the proposed projection preserves the topological integrity of polar regions, enabling mathematically rigorous ellipsoid-based cartography. The ability to faithfully represent polar geometry holds considerable importance for precision-dependent activities such as polar navigation and scientific research, providing a reliable spatial reference framework for high-latitude applications.

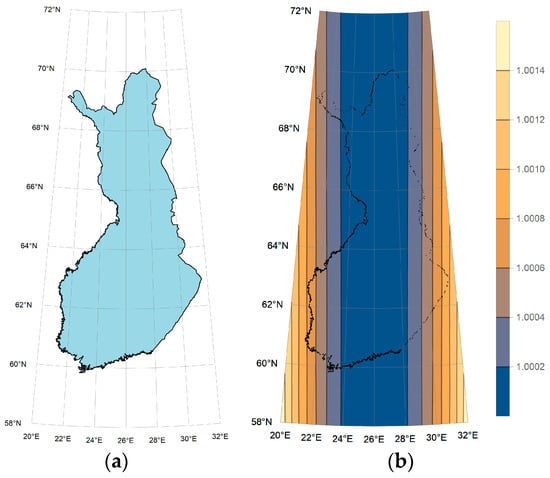

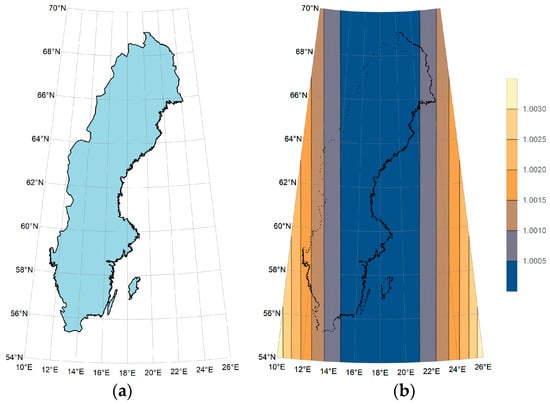

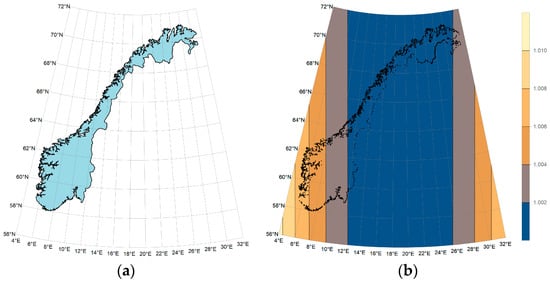

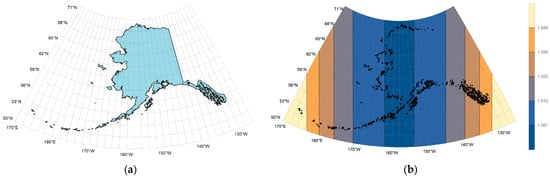

The practical utility of the non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection is demonstrated through its application to four high-latitude regions: Finland, Sweden, Norway, and the state of Alaska. As depicted in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9a, each region is mapped with central meridians appropriately selected to minimize distortion for each area.

Figure 6.

The mapping of Finland and its isopleth map of the length ratio in the nonzonal and non-singular GK projection (the central meridian: 26° E): (a) the mapping of Finland; (b) the isopleth map of the length ratio.

Figure 7.

The mapping of Sweden and its isopleth map of the length ratio in the non-zonal and non-singular GK projection (the central meridian: 18° E): (a) the mapping of Sweden; (b) the isopleth map of the length ratio.

Figure 8.

The mapping of Norway and its isopleth map of the length ratio in the non-zonal and non-singular GK projection (the central meridian: 18° E): (a) the mapping of Norway; (b) the isopleth map of the length ratio.

Figure 9.

The mapping of Alaska and its isopleth map of the length ratio in the non-zonal and non-singular GK projection (the central meridian: 18° E): (a) the mapping of Alaska; (b) the isopleth map of the length ratio.

In the cases of Finland and Sweden, which have relatively limited east–west extent, the non-zonal and non-singular projection produces outcomes nearly identical to those of the traditional zonal Gauss–Krüger projection. Geodetic analysis confirms that the length distortion remains very small throughout both countries. For Finland, the maximum length ratio is 1.0014, with most regions exhibiting a length ratio below 1.0002, as shown in Figure 6b. Similarly, Sweden experiences a maximum length ratio of 1.003, while the majority of its territory maintains a ratio below 1.0005 (Figure 7b).

Notably, the projection overcomes the zonal limitations inherent in the traditional Gauss–Krüger approach while retaining a length ratio within 1.001 across most of the national territories of Finland and Sweden. This combination of zonal flexibility and minimal distortion offers significant value for mapping and geospatial applications in high-latitude countries.

The proposed non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection effectively addresses a key limitation of traditional zonal methods when applied to regions with large longitudinal extents, such as Norway and the state of Alaska. Due to their significant east–west span—with Alaska even crossing the eastern and western hemispheres—and high latitudes, the conventional zonal Gauss–Krüger projection fails to provide continuous and accurate mapping, as its segmentation leads to discontinuities and scale inconsistencies. The challenge is resolved by the non-zonal formulation introduced in this study. As illustrated in Figure 8a and Figure 9a, the projection seamlessly accommodates large longitudinal ranges without splitting the region into multiple zones, thus maintaining mapping continuity and conformality.

Despite Norway’s considerable east–west extent, the length distortion remains well controlled. As shown in Figure 8b, most of the country exhibits a length ratio below 1.002, with the maximum value not exceeding 1.008. Similarly, in Alaska—a region of exceptional longitudinal spread—the length ratio is generally kept at or below 1.01 across most of the area (Figure 9b), making the projection particularly suitable for small-scale mapping applications where zonal boundaries would otherwise introduce significant practical complications. The capability of this projection to maintain low distortion over large longitudinal intervals while avoiding zonal discontinuities highlights its cartographic value for mapping extensive high-latitude regions, fulfilling critical demands in both scientific and operational contexts.

Computer algebra systems have gained extensive adoption in modern geodesy, particularly for solving complex geodetic problems and performing coordinate transformations with high symbolic and numerical accuracy. However, their application remains notably underutilized in the development and analysis of new map projections—a domain that still heavily relies on traditional, often iterative and zonal, methods. Consequently, many practical geodetic and cartographic tasks, such as the computation of great circle routes in navigation, continue to depend on conventional projections that may introduce limitations in flexibility, accuracy, or computational efficiency.

This study demonstrates how computer algebra can significantly streamline the construction and optimization of map projections. By enabling the analytic derivation, simplification, and high-order expansion of projection equations, such systems facilitate the development of closed-form and computationally efficient solutions.

The non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection presented herein exemplifies this approach. It serves as a scientifically robust and practical reference for numerous applications—especially in marine science and engineering across high-latitude regions. Furthermore, its methodological relevance and accuracy extend to mid-latitude countries, underscoring the broad utility and transformative potential of computer-algebraic methods in advancing cartographic science.

4. Conclusions

This study has established a mathematically rigorous framework for a non-zonal and non-singular Gauss–Krüger projection suitable for polar regions. By reformulating the projection using conformal latitude and conformal colatitude, the inherent singularity at the poles has been effectively resolved. The resulting formulation allows for seamless application in high-latitude areas, overcoming a fundamental limitation of traditional zonal approaches. As a summary, we highlight the major conclusions here:

- (1)

- These series expansions of the Gauss–Krüger projection in term of third flattening yield significantly simpler coefficient structures while maintaining computational accuracy, thereby streamlining the projection equations without compromising precision. In parallel, a comprehensive derivation of the non-zonal and non-singular formulas in polar regions was conducted, based on the framework of third flattening parameter system.

- (2)

- This computer algebra system was instrumental not only in the derivation and simplification of high-order series but also in enabling the practical visualization and direct application of the method. The projection’s robustness and performance were rigorously validated through case studies of 4 high-latitude regions, including Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Alaska. The results demonstrate the method’s capability to maintain smaller distortion even across areas with large longitudinal extents, such as Alaska, which spans the eastern and western hemispheres.

- (3)

- Compared to the traditional Gauss–Krüger projection, the complex function of the Gauss–Krüger projection provides a non-zonal and non-singular solution for ellipsoid-based mapping in polar environments, with relevance to polar navigation, marine science and engineering in high-latitude countries. Furthermore, its methodological framework offers substantial value for mid-latitude regions, presenting a meaningful supplement to the existing Gauss–Krüger projection family.

Author Contributions

Deduction and the computer algebra analysis, D.Z. and S.B.; Analysis of results: D.Z. and W.L.; Formulas of the ellipsoid: Z.W. and D.Z.; Nonzonal formulas: D.Z.; writing, D.Z. and S.B.; All authors approved the final manuscript and contributed to the design and interpretation, as well as review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 42174051 and No. 42430101; the Opening Fund of Key Laboratory of Geological Survey and Evaluation of Ministry of Education under Grant No. GLAB2024ZR05 and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Data Availability Statement

This study focuses on refining the zonal and singular problem, and does not use third-party data, and the date used in the analysis of the results is the dataset that comes with Mathematica.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Scacchia, E.; Casalbore, D.; Gamberi, F.; Spatola, D.; Bianchini, M.; Chiocci, F. Shallow-Water Submarine Landslide Susceptibility Map: The Example in a Sector of Capo d’Orlando Continental Margin (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palikaris, A.; Mavraeidopoulos, A. Electronic navigational charts: International standards and map projections. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abee, M. The spread of the mercator projection in western european and united states cartography. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization 2021, 56, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Gnomonic projection of the surface of an ellipsoid. J. Navig. 1997, 50, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, J.; Grafarend, E. The oblique Mercator projection of the ellipsoid of revolution IE a 2, b. J. Geod. 1995, 70, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, R.E.; Hunter, M.N.; Karney, C.F.F. The gauss-krüger projection. In Proceedings of the 23rd Victorian Regional Survey Conference, Warrnambool, Australia, 10–12 September 2010; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, O. Theorie der Projectionsmethode der Hannoverschen Landesvermessung; Hahn: Berlin, Germany, 1866. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, O. Die Konforame Doppelprojektion der Trigonometrischen Abteilung der Königl. Preussischen Landesaufnahme–Formeln und Tafeln; Hanh: Berlin, Germany, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, L. Konforme Abbildung des Erdellipsoids in der Ebene; Royal Prussian Geodetic Institute: Potsdam, Germany, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, C. Transverse Mercator with an accuracy of a few nanometers. J. Geod. 2011, 85, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Bian, S. Optimization of complex function expansions for Gauss-Krüger projections. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.C.; Shen, W.B.; Ning, J.S. Development of Lee’s exact method for Gauss–Krüger projection. J. Geod. 2020, 94, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, B.; Su, F. A Study on the Spatial Morphological Evolution and Driving Factors of Coral Islands and Reefs in the South China Sea Based on Multi-Source Satellite Imagery. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, W.; Jiao, H. A Novel COLREGs-Based Automatic Berthing Scheme for Autonomous Surface Vessels. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Huang, Z.; Wang, P.; Xu, Z.; Kong, D. A Low-Complexity Path-Planning Algorithm for Multiple USVs in Task Planning Based on the Visibility Graph Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Solera, M.; Otero, J. Simple and highly accurate formulas for the computation of Transverse Mercator coordinates from longitude and isometric latitude. J. Geod. 2009, 83, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Solera, M.; Otero, J. Global optimization of the Gauss conformal mappings of an ellipsoid to a sphere. J. Geod. 2010, 84, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafarend, E.; Syffus, R. Mixed cylindric map projections of the ellipsoid of revolution. J. Geod. 1997, 71, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafarend, E.; Syffus, R. The Hammer projection of the ellipsoid of revolution (azimuthal, transverse, rescaled equiareal). J. Geod. 1997, 71, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafarend, E.; Syffus, R. The optimal Mercator projection and the optimal polycylindric projection of conformal type–case-study Indonesia. J. Geod. 1998, 72, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bian, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, Y. Nonzonal expressions of Gauss-Krüger projection in polar regions. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 3, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessel, F.W. Bestimmung der Axen des elliptischen Rotationssphäroids, welches den vorhandenen Messungen von Meridianbögen der Erde am meisten entspricht. Astron. Nachrichten 1837, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, C. Algorithms for geodesics. J. Geod. 2013, 87, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, C. On auxiliary latitudes. Surv. Rev. 2024, 56, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J. Ellipsoid Geodesy; Chinese People’s Liberation Army Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.