Abstract

This paper is devoted to the investigation of the proper strict efficient solutions to a set optimization problem with a partial set order relation. Firstly, the notion of proper strict efficient solution defined by the Minkowski difference is introduced, and it is worth mentioning that the introduced strict efficiency is different from those in the existing literature. Secondly, a class of generalized contingent derivatives for set-valued maps is proposed, which are characterized in terms of a set criterion. Finally, the necessary and sufficient optimality conditions and a scalarization theorem for proper strict efficiency are established. Some concrete examples are given to illustrate the obtained results.

Keywords:

set optimization; proper strict efficiency; Minkowski difference; generalized derivative; optimality conditions MSC:

90C46

1. Introduction

Set optimization is a primary approach to addressing set-valued optimization problems and has been widely studied in uncertain multi-objective programming [1], optimality conditions [2], and higher-order derivatives [3,4]. Kuroiwa [5] pointed out that there is a lack of a total order relationship between sets, so it is necessary to introduce some set order relations to enable the comparison between two sets. Currently, Jahn [6] has already summarized some order relations, including the upper set order relation, lower set order relation, minmax set order relation, and others. However, the order relations presented in [6] are preorder relations. To address this, Karaman et al. [7] defined a kind of partial set order relation using the Minkowski difference.

Strict efficiency is an important concept for optimization problems, and it has been applied in sensitivity analysis [8] and convergence analysis of algorithms [9]. Because of the wide applications of strict efficiency, many authors have been interested in extending it to the set-valued maps. For example, Flores [10] developed a kind of strict local efficient solutions and obtained optimality conditions for a set-valued optimization problem; Mohamed [11] proposed the concept of directional strict efficiency and established its optimality for a set-valued equilibrium problem; Another strict efficiency associated with preference mappings was presented in [12], and its higher-order optimality theorems for a set-valued optimization problem were obtained. For more details on strict efficiency, see [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Recently, Huerga et al. [19] presented the notion of Henig proper strict efficient solution for a set optimization problem with a lower set order relation and investigated some of its properties. Motivated by [19], this paper attempts to introduce a class of proper strict efficient solutions for a set optimization problem related to the partial set order relation and establish its optimality conditions.

The derivative and its generalization are powerful tools to establish optimality conditions for set optimization problems. For instance, Yao [3] introduced the notion of generalized radial derivative and used it to derive second-order optimality conditions for a set optimization problem with a lower set order relation; Yu [4] applied a kind of higher-order radial derivative to establish optimality theorems for a constrained set optimization problem with respect to a weak lower set order relation. Our purpose is to give a class of generalized contingent derivatives of set-valued maps and employ them to construct optimality conditions for a set optimization problem associated with the partial set order relation. Further, Khushboo et al. [20] established a scalarization theorem for the partial set order relation using the oriented distance. This paper aims to obtain the corresponding scalarization results via a different function.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 recalls some basic notions, definitions, and lemmas needed in the sequel. Section 3 introduces the concept of a proper strict efficient solution for a set optimization problem and discusses some of its properties. Section 4 gives a kind of generalized contingent derivative defined by a set criterion and utilizes it to establish necessary and sufficient optimality conditions for proper strict efficient solution. Finally, a scalarization theorem is obtained in Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

Let Y be two normed spaces, and let and be the set of natural numbers and n-dimensional Euclidean space, respectively. stands for the open ball with center and radius , and

Let be a nonempty subset; , , and denote the interior, the convex hull, and the complement of E, respectively; and let the cone generated by E be . The tangent cone of set E at is given by (see [21])

Given a set-valued map , we denote the domain, graph, epigraph, and profile map of F, respectively, by

Throughout the paper, let be a nonempty pointed closed convex cone, and let denote the family of all nonempty bounded subsets in Y. For , the algebraic sum and Minkowski difference of A and B are defined by [7]

Lemma 1

([2,7]). Let and Then the following assertions hold:

(i) ;

(ii) ;

(iii) ;

(iv) .

Next, we recall a partial set order relation defined by the Minkowski difference.

Definition 1

([7]). Let be arbitrary chosen sets. The partial set order relation with respect to K, denoted by , is defined as

3. Proper Strict Efficiency

Let be a set-valued map and be a nonempty subset. We consider the following Set Optimization Problem

It is always assumed that is nonempty for all in the paper.

Definition 2

([20]). In problem (SOP), is called a -efficient solution, denoted by , if there is no such that and , that is,

Next, we introduce two concepts of strict efficient solutions related to for problem (SOP).

Definition 3.

In problem (SOP),

(i) is called a strict -efficient solution, denoted by , if for all , i.e.,

(ii) is called a proper strict -efficient solution, denoted by , if there exists such that

Here is an example to illustrate the concepts of Definition 3.

Example 1.

In problem (SOP), let , , , and

Let , it yields . Since

we obtain is a strict -efficient solution. In addition, there exists such that

Thus, is also a proper strict -efficient solution.

Remark 1.

(i) In terms of form, Definition 3 (ii) of this paper differs from those in [10]. If , it follows from Lemma 1 (iv) that . Then, Definition 3 (ii) reduces to the strict efficient solution in [10].

(ii) In terms of applicability, Definition 3 (i) of this paper is distinct from those in [19]. In [19], is called the strict -Henig proper solution of problem (SOP) if there is no such that , that is,

where H is a pointed closed convex cone and . An example is given below to illustrate the validity of Remark 1 (ii).

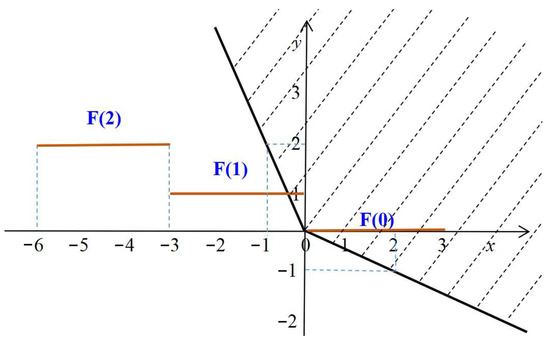

Example 2.

In problem (SOP), let , , , , and

Let , there exists such that

Hence, is a proper strict -efficient solution.

However, as seen in Figure 1, there exists such that

Thus, is not a strict -Henig proper solution.

Figure 1.

Illustrations of and H.

Remark 2.

In problem (SOP), if is single-valued, then . The proper strict -efficient solution becomes the following form

In this case, it is also different from the Henig proper minimal solution defined in literature [19]. A point is called a Henig proper minimal solution of problem (SOP) if there exists such that

where H is a pointed closed convex cone and . This fact can be illustrated by the following two examples.

Example 3.

In problem (SOP), let , , , , and . Define

Take , we derive . Due to

we conclude is a Henig proper minimal solution.

However, for any , there exists such that

Consequently, is not a proper strict -efficient solution.

Example 4.

In problem (SOP), let , , , , and

Let , then . For all , there exists such that

Hence, is a proper strict -efficient solution.

However, there exists such that

Thus, is not a Henig proper minimal solution.

Some properties of the proper strict -efficient solution are listed below.

Lemma 2.

In problem (SOP), the following statements hold:

(i) ;

(ii) If , then and ;

(iii) ;

(iv) .

Proof.

(i) Firstly, we prove . Let , then there exists such that

Suppose that , there exists such that

This means that there exists such that

Since and , one has

Consequently, we conclude

which contradicts Equation (4). Therefore, holds.

Now, we verify . Take , it holds

Assume that , then there exists such that

If , it yields , which contradicts . Hence, there exists such that . This is a contradiction to Equation (5). Consequently, holds.

(ii) It follows from Definition 3 that the proof is obvious.

(iii) Assume that , there exists such that

Since K is a pointed closed convex cone, we get . Combined with Equation (6), hence,

This indicates that .

Next, we testify holds. Let , then there exists such that

This indicates that for any and any

Suppose that , then there exists such that for any

This means that there exist and such that . Since

and K is a convex cone, we have . Therefore, there exist , and such that

which contradicts Equation (7). This implies that . Hence, is true.

(iv) Let . By Definition 3, one has

Since K is a pointed closed convex cone, we have . Hence,

which implies that . This shows that holds.

Conversely, if , then

Assume that , there exists such that

Hence, there exists such that . Since

and K is a convex cone, one has . Thus, there exists such that

which contradicts Equation (9). Hence, we have , that is, . This shows that holds. □

In some practical problems, in order to make a rapid and effective decision, people prefer to acquire a smaller decision set. By Lemma 2 (i), it yields . This implies that the solution sets and are two refinements of the solution set . Therefore, it is of practical significance and value to explore the solution sets and . The following Example 5 is provided to illustrate this fact.

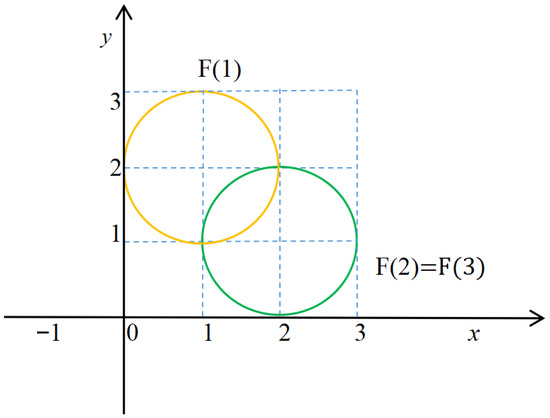

Example 5.

In problem (SOP), let , , and . Define

As seen in Figure 2, since

we get . In this case, a decision-maker does not know how to make the choice.

Figure 2.

Illustrations of .

However, we claim . Indeed, since

it leads to

Thus, . But, if take or , we have

Consequently, . Furthermore, due to

we get . But, when , for all , there exists such that

Thus, .

In literature [10], it has been pointed out that the notation denotes the set of all cluster points of sequences with and . Next, we present an equivalent characterization of proper strict -efficient solution, which will play a crucial role in the proof of optimality conditions in Section 4.

Proposition 1.

In problem (SOP), let . if and only if

Proof.

Suppose that Equation (10) is not true. Then there exist , such that and

This means that for any , there exists , for all , we have , and . Therefore,

Since K is a pointed closed convex cone, we get . Thus,

Since , according to Lemma 2 (iii), we derive . Consequently, there exists such that

Let , then there exists such that for all and

This contradicts Equation (11).

Conversely. Assume that . It follows from Lemma 2 (iii) that . Thus, for any , there exists such that

This means that there exists such that

Hence, for any , there exist , such that

Particularly, take , then , that is,

Thus, we conclude

which contradicts Equation (10). This completes the proof. □

4. Optimality Conditions

This section aims to introduce a class of generalized contingent derivatives and apply them to establish necessary and sufficient optimality conditions for the proper strict -efficient solution of problem (SOP). Before that, we give the notion of a generalized contingent cone.

Definition 4.

Let . The generalized contingent cone of S on W is defined by

Remark 3.

(i) It is obvious that if , then .

(ii) Due to , then Equation (12) can be equivalently expressed as

(iii) If is single-valued and , then the generalized contingent cone reduces to the contingent cone in literature [21], that is, Equation (1).

Next, we give an example of a generalized contingent cone.

Example 6.

Let and . By a simple calculation, we have and .

Lemma 3.

Let . The following statements hold:

(i) If , then ;

(ii) .

Proof.

(i) For any , by Definition 4, there exist , such that , , that is,

Since , by means of Equation (13), we have

According to Remark 3, then . By the arbitrariness of d, hence, holds.

(ii) For any , there exist , such that , , that is,

Due to and , we derive from Equation (14) that

which means that and by Remark 3. Thus, the conclusion is valid. □

Based on the above generalized contingent cone, we now introduce the concepts of generalized contingent derivative and generalized contingent epiderivative.

Definition 5.

Let be a set-valued map, and .

(i) The generalized contingent derivative of F at is the set-valued map defined by

(ii) The generalized contingent epiderivative of F at is the set-valued map defined by

Here is an example of a generalized contingent derivative.

Example 7.

Let , be given by

It is clear that . For any , we get . Indeed, assume that , then there exist , , such that

Hence, we have , that is,

This implies that .

Remark 4.

(i) By Remark 3 (i), it yields that if , then .

(ii) It is clear that and for all .

(iii) If is single-valued, then the generalized contingent derivative reduces to the contingent derivative in literature [21], i.e.,

Further, since , by the above definitions, it is clear that . However, is not necessarily true. The following example justifies this fact.

Example 8.

Let , and

Then . Take , for any , we have

Thus, .

Next, two necessary optimality conditions of proper strict -efficient solution are established by using the above generalized derivatives.

Theorem 1.

In problem (SOP), let . If , then

Proof.

Theorem 2.

In problem (SOP), let . If , then

Proof.

If , according to Lemma 2 (iii), we derive . Thus, there exists such that

That is,

By a similar method to Theorem 1, we can obtain the corresponding result. □

Next, we give a lemma, which will play an important role in the proof of sufficient condition.

Lemma 4.

In problem (SOP), let and . Then

Proof.

The necessity is obvious since K is a cone.

Next, we prove sufficiency. Suppose that . Then there exists such that . This implies that there exist , and such that . This is equivalent to

Since , for any , and , we have . According to , we have

Note that K is a convex cone and , consequently,

that is,

Hence, we get , which contradicts Equation (16). The proof is completed. □

Now, we present a sufficient optimality condition for the proper strict -efficient solution.

Theorem 3.

In problem (SOP), let X be finite-dimensional, and . If

then, .

Proof.

Remark 5.

It is worth noting that the proof of the sufficient optimality condition in Theorem 3 does not require any assumptions of convexity and compactness; in this case, it is different from the results of the literatures [19,22].

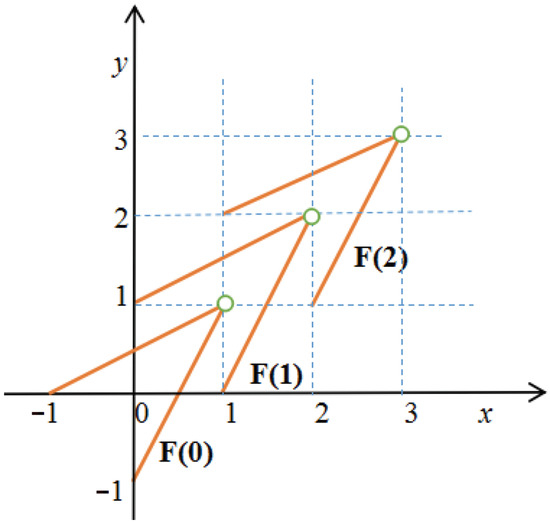

We give an example to explain that Theorem 3 holds even if the map F is not convex and compact.

Example 9.

In problem (SOP), let , , , and

As seen in Figure 3, it is clear that F is not convex and compact on . Let , then . By a direct calculation, we have , and for all . Thus,

Figure 3.

Illustrations of .

In addition, for all , there exists such that

Hence, is a proper strict -efficient solution of problem (SOP).

5. Scalarization

Throughout this section, let . In literature [7], a scalar function is defined as follows:

The following lemmas summarize some properties of the function .

Lemma 5

([7]). Let . The following assertions hold:

(i) ;

(ii) If is nonempty, then ;

(iii) If is compact and K is closed, then .

Lemma 6.

Let , and be nonempty. Then .

Proof.

It follows from Equation (19) and Lemma 1 that

□

Let . Considering the following scalar problem

Definition 6.

A point is called proper strict minimizer solution of problem (P), denoted by , if there exists a such that

Next, we present a relationship between the proper strict -efficient solution of problem (SOP) and the proper strict minimizer solution of problem (P).

Theorem 4.

Let and be nonempty and compact for all . Then .

Proof.

Firstly, we prove holds. Assume that , but , then there exists such that for any

Since , and is an open set, then 0 is an interior point of . According to the definition of interior points, there exists such that the neighborhood . Furthermore, due to , we conclude that . For any , then

Since K is a convex cone, we get

Together with Equation (20), one has

This is equivalent to

Hence,

According to Lemma 5 (iii), we have

By Lemma 6, it holds

Thus,

Note that , we obtain

which contradicts .

We give an example to illustrate Theorem 4.

Example 10.

In problem (SOP), let , , , and

Then . Let , there exists such that

Thus, . Now, we testify . Indeed, take , , due to and

we get from Definition 6 that .

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have introduced the notion of proper strict efficient solution for a set optimization problem with a partial set order relation and emphasized that this proper strict efficient solution differs from those defined in the literature [10,19]; the corresponding results have been summarized in Remarks 1 and 2. We have also proposed a class of generalized contingent derivatives, different from the literature [21]; they are given by set criteria, not vector criteria. Finally, two necessary optimality conditions, a sufficient optimality condition, and a scalarization theorem for proper strict efficient solution are established.

It is worth mentioning that the results obtained in the paper do not need any assumptions of convexity and compactness, which are distinct from the conclusions in the literature [19,22]. On the other hand, our sufficient optimality condition holds only in finite-dimensional spaces, and it will be interesting to continue to explore the case in infinite-dimensional spaces.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H.; Validation, G.Y.; Writing—original draft, W.H.; Funding acquisition, G.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Ningxia Province of China (No. 2023AAC02053), the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant (No. 12361062), and the Youth Talent Cultivation Project of North Minzu University (No. 2024QNPY18).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Han, W.Y.; Yu, G.L. Optimality and error bound for set optimization with application to uncertain multi-objective programming. J. Glob. Optim. 2024, 88, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.Y.; Yu, G.L. Directional derivatives in set optimization with the set order defined by Minkowski difference. Optimization 2025, 74, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Li, S.J. Second-order optimality conditions for set optimization using coradiant sets. Optim. Lett. 2020, 14, 2073–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.L. Optimality conditions in set optimization employing higher-order radial derivatives. Appl. Math.—J. Chin. Univ. 2017, 32, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroiwa, D. Some duality theorems of set-valued optimization with natural criteria. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Nonlinear Analysis and Convex Analysis; World Scientific: Singapore, 1999; Volume 17, pp. 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, J.; Ha, T. New Order Relations in Set Optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2011, 148, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, E.; Soyertem, M.; Güvenc, İ.T.; Tozkan, D. Partial order relations on family of sets and scalarizations for set optimization. Positivity 2018, 22, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrion, R.; Outrata, J. A subdifferential condition for calmness of multifunctions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2001, 258, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.V.; Ferris, M.C. Weak sharp minima in mathematical programming. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1993, 31, 1340–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Bazán, F.; Jiménez, B. Strict efficiency in set-valued optimization. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2009, 48, 881–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Marius, D.; Hassan, R. Strict directional solutions in vectorial problems: Necessary optimality conditions. J. Global Optim. 2022, 82, 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Anna, M.; Marcin, S. Higher-Order optimality conditions in set-valued optimization with respect to general preference mappings. Set Valued Var. Anal. 2022, 30, 975–993. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Yu, G.L. Higher-Order Radial Hadamard Directional Derivatives and Applications to Set-Valued Equilibrium Problems. Asia-Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 41, 2450006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.V.; Hang, D.D. Second-order optimality conditions in locally Lipschitz multiobjective fractional programming problem with inequality constraints. Optimization 2023, 72, 1171–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Yu, G.L. Higher-order optimality conditions with separated derivatives and sensitivity analysis for set-valued optimization. RAIRO-Oper. Res. 2024, 58, 3049–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, B. Strict minimality conditions in nondifferentiable multiobjective programming. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2003, 116, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amahroq, T.; Daida, I.; Syam, A. Optimality conditions for sharp minimality of order γ in set-valued optimization. Le Matematiche 2018, 73, 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarczuk, E.M. Weak sharp efficiency and growth condition for vector-valued functions with applications. Optimization 2004, 53, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerga, L.; Jiménez, B.; Novo, V. New Notions of Proper Efficiency in Set Optimization with the Set Criterion. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2022, 195, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushboo; Lalitha, C.S. Scalarizations for a set optimization problem using generalized oriented distance function. Positivity 2019, 23, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, J.P.; Frankowska, H. Contingent derivatives of set-valued maps and existence of solutions to nonlinear inclusions and differential inclusions. Adv. Math. Suppl. Stud. 1980, 159–229. [Google Scholar]

- Corley, H.W. Optimality conditions for maximizations of set-valued functions. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1988, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.