Abstract

The Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT) is a widely used reversible data compression method, forming the foundation of various compression algorithms and indexing structures. Prior research has analyzed the sensitivity of compression methods and repetitiveness measures to single-character edits, particularly in binary alphabets. However, the impact of such modifications on the compression efficiency of the bijective variant of BWT (BBWT) remains largely unexplored. This study extends previous work by examining the compression sensitivity of both BWT and BBWT when applied to larger alphabets, including alphabet reordering. We establish theoretical bounds on the increase in compression size due to character modifications in structured sequences such as Fibonacci words. Our devised lower bounds put the sensitivity of BBWT on the same scale as of BWT, with compression size changes exhibiting logarithmic multiplicative growth and square-root additive growth patterns depending on the edit type and the input data. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of repetitiveness measures.

Keywords:

lossless data compression; Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT); bijective BWT (BBWT); compression sensitivity; string transformations; Fibonacci words; Lyndon factorization; compression efficiency analysis MSC:

68P30

1. Introduction

The Burrows–Wheeler transform (BWT) [1] has attracted great attention in interdisciplinary fields such as lossless data compression and text indexing. It lies at the heart of compression algorithms like bzip2 and text indexing data structures such as the FM-index [2]. By compressing single character runs of the BWT, we obtain a compressed but reversible transformation, which can be augmented with techniques akin to the FM-index to give rise to compressed text indices [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Because of its reversible nature, the BWT is also used in bioinformatics applications such as sequence alignment and genome assembly [9,10]. Workshops (e.g., [11,12]) and books (e.g., [13]) have been dedicated exclusively to the BWT and its applications.

Given word T of length n, the BWT of T is a permutation of its characters. In detail, we sort all cyclic conjugates of T lexicographically and concatenate the last characters of these conjugates to form the BWT of T. The BWT is a reversible transformation by application of the so-called Gessel–Reutenauer transform [14].

Among various variants of the BWT (e.g., [15,16,17,18,19]), the bijective BWT (BBWT) [20] can be considered as one of the well-perceived ones that is a word isomorphism. A word isomorphism maps a word to another word injectively, and each word is a unique image of another word. For instance, this is not the case for the BWT, whether we add additional information such as an artificial delimiter (known as the $ character) or a starting position, cf. [21,22,23].

In this article, we focus on the run-length compression of the BWT and the BBWT: run-length compression is usually the first step in the compression pipeline of the BWT and its variants. In addition, compressed text indices such as the r-index [4] store the BWT in a run-length compressed form. The run-length compression of word T is the number of maximal runs of equal characters in T. For instance, the word can be written in an exponential notation as and therefore has eight runs. We denote the run-length compression of word T by . Given word T, we define the following two repetitiveness measures:

- and

- .

In this article, we investigate the sensitivity of the BWT and the BBWT to single-character edits. This means that we analyze how the run-length compression of the BWT and the BBWT changes when we modify a single character of the input word. Previous research has shown that the run-length compression of the BWT is sensitive to single-character edits in binary alphabets [24]. Here, we extend this research to larger alphabets and analyze the sensitivity of the BBWT to single-character edits. Research on compression sensitivity is not a new topic, of which we are aware. We present following related work.

2. Related Work and Contribution

The sensitivity [25] of a repetitiveness measure m is the maximum difference in the sizes of for word T and for a single-character edited word . Sensitivity measures the robustness of a repetitiveness measure against small changes in the input word introduced by various sources of input (source code changes, biological sequencing errors, typos, etc.). Akagi et al. [25] reviewed known results that directly imply a sensitivity for repetitiveness measures such as for Lempel–Ziv 78 [26] or the BWT [24]. Additionally, they offered and improved upper and lower bounds on the multiplicative sensitivity of various compressors and measures including the Lempel–Ziv dictionary compressors [27,28] and the smallest string attractors [29].

In detail, for two words and , we let denote the edit distance between and . We define the additive sensitivity and multiplicative sensitivity of a repetitiveness measure by

- , and

- .

The sensitivity has been studied for lexparse [30] by Nakashima et al. [31] and for the size of the compact directed acyclic word graph [32] by Fujimaru et al. [33]. In particular, Giuliani et al. [24] showed that and .

Our contribution. In this article, we show identical results for the BBWT, confirming that it is also sensitive to single-character edits. Concretely, we establish that with Theorem 5 and with Lemma 47. In detail, we obtain the asymptotically same results regarding :

- in Theorem 5 for deletion,

- in Theorem 6 and Theorem 7 for substituting a character with a smaller or larger one, respectively, and

- in Theorem 8 and Theorem 9 for insertion of or a strictly smaller character #, respectively.

We also obtain the asymptotically same results regarding :

- in Theorem 10 for deletion,

- in Theorem 12 for inserting a large character, and

- in Theorem 11 and Theorem 13 for substituting a character with a smaller or larger one, respectively.

Additionally, we broaden the study of the sensitivity of the BWT by allowing larger alphabets (Theorem 2) and alphabet reordering (Theorem 4), obtaining the same asymptotic complexities as reported by Giuliani et al. [24].

Since our major contribution is on the BBWT, we also briefly review known results related to it.

BBWT. Since its inception [20], the BBWT has been studied under various aspects. We are aware of construction algorithms (cf. [34] or [35] and the references therein), indexes [35] based on the BBWT, studies about the relationship of and r [36], and of the reverse of T [37].

3. Preliminaries

In this section, we provide the necessary definitions and terminology used throughout the paper. A list of symbols is given in Table 1.

Words. We let be a finite and ordered alphabet with cardinality . The elements of are called characters. A word over is a finite sequence of characters from . The order of the alphabet induces the lexicographic order on words, which we also denote by .

We denote the length of W by , with being the unique word of length 0. We denote the set of words of length n by , and represent the set of all words on by . Given word , we define its reverse by . If for words , then are, respectively, a prefix, a subword, and a suffix of W. We call word a conjugate of W if and only if there is integer such that . In this case, we write . In particular, . We call word U a circular factor of word W if it is a prefix of for some ; in this case, we call i (the starting position of) an occurrence of U. If we can express word W as for word V and integer , then we call W a power, otherwise we call W primitive. Finally, W is primitive if and only if it has distinct conjugates.

Given two words , the longest common prefix of V and W, denoted , is the unique word U such that U is a prefix of both V and W, and if neither of the two words is a prefix of the other.

The Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT). We define the BWT of word W based on its conjugates. For that, we define two concepts, an order and a list of conjugates sorted in that order. First, the omega-order [16] of two words T and S as follows: if either or and . Here, denotes the infinite word obtained by concatenating word S an infinite number of times. The omega-order coincides with the lexicographic order if neither of two words is a proper prefix of the other but may differ otherwise. Second, we let be the list of sorted conjugates of word W in omega-order.

Now, we can define the Burrows–Wheeler Transform (BWT) [1] of the word W, denoted by , as the word obtained by reading the last character of each conjugate in .

For instance, the BWT of word is . By construction, it follows that W and are conjugates if and only if . We denote by the number of runs in the BWT of word W. For example, .

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols introduced in this article.

Table 1.

Definitions of symbols introduced in this article.

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| r | run length of the BWT |

| ρ | run length of the bijective BWT |

| n | length |

| k | index |

| # | a character lexicographically smaller than |

| a character lexicographically larger than | |

| kth Fibonacci word | |

| kth Fibonacci number | |

| kth central word | |

| kth Lyndon Fibonacci word | |

| kth Fibonacci word deleting its last character | |

| kth Fibonacci Lyndon word deleting its last character | |

| deleting its last character | |

| deleting the last character | |

| Lyndon word of | |

| deleting its last character | |

| deleting its last character | |

| changed into | |

| changed into | |

| changed into | |

| subword of BWT(W) corresponding to the range of contiguous conjugates prefixed by W | |

| subword of BWT(W) applied to a specific edit operation | |

| the list of lexicographically sorted conjugates of word W |

Lyndon Words. A word is called a Lyndon word if it is lexicographically strictly smaller than all of its conjugates [38]. In particular, a Lyndon word must be primitive. Each primitive word S has exactly one conjugate that is Lyndon. We denote this conjugate by and call it the Lyndon conjugate of S. The Lyndon factorization [39] of word W is a unique factorization of W into Lyndon words. In detail, it decomposes word W into a list of Lyndon words such that , where and . By construction, word S is Lyndon if and only if its Lyndon factorization consists of only one factor, i.e., S itself. We denote the multiset of Lyndon factors in the Lyndon factorization of S by . As an example, we consider . The Lyndon factorization of is . We have .

Bijective BWT (BBWT). The Bijective BWT (BBWT) [20] of word T is the word obtained by sorting all conjugates of the Lyndon factors in the multiset in -order and then concatenating the last character of each sorted conjugate. For example, the BBWT of the word is . In this article, we denote as the compression ratio of BBWT, which means . For instance, .

Fibonacci Words. Fibonacci words are so-called standard words ([40], Section 10.1), which are defined as follows. , , for every . For all , , where are the Fibonacci numbers , defined by the recurrence for . Since Fibonacci numbers grow exponentially in k, we have . We also introduce so-called central words [41] for , which are palindromes defined by equation for all . The central words and are palindromes. In particular, . The recursive structure of words and is also known [42]:

- and

- .

We study Fibonacci words in this article because they have the minimal number of BWT runs among binary words. This is because Mantaci et al. [43] have shown that the BWT of a binary word has exactly two runs if and only if it is a conjugate of a standard word or a conjugate of a power of a standard word. Further, there is rich literature (e.g., [44,45,46]) about Fibonacci words and their rotations.

4. Multiplicative Sensitivity of by

As a startup, we follow the steps of (Giuliani et al. [24], Section 3), who studied a family of Fibonacci word-related words for which they could observe a multiplicative sensitivity of for the number of character runs in the BWT. We here show a similar result, but use a new character (#) instead of one already appearing in the binary word. To facilitate notation, we write < for when sorting conjugates. We build our proofs on the insights from the following results from the literature.

Lemma 1.

(Remark 11 from [16]). All conjugates of a word have the same BWT.

Lemma 2.

(Proposition 4 of [24]). We let be a word that removes the last character of , then .

Lemma 3.

(Lemma 7 of [24]). is the smallest conjugate in .

Lemma 4.

We let be a Lyndon word of that contains at least two distinct characters and let # be a character that does not occur in v. Then, .

Proof .

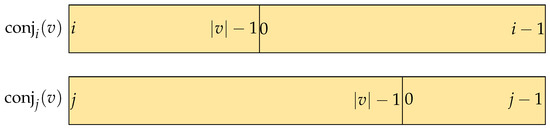

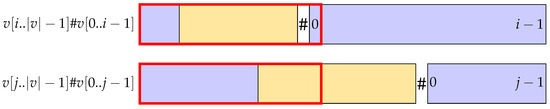

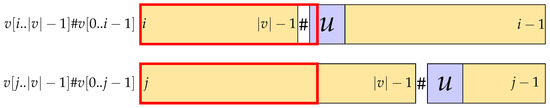

We refer to from Lemma 3 as v here if only . The conjugates of v with index i and j are , , respectively. Also, we set the lexicographic order between two conjugates as ; thus, . We prove this separately in two cases, where Figure 1 sketches the setting.

Figure 1.

Sketch of the setting considered in the proof of Lemma 4.

- Case 1:

- |lcp()| < min();

- Case 2:

- |lcp()| > min().

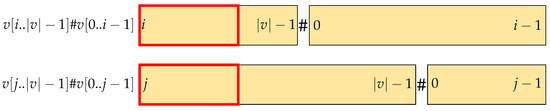

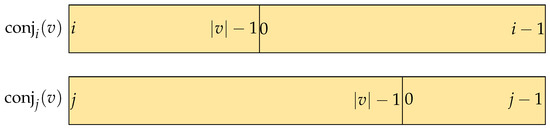

The red rectangle in Figure 2 is an example of a common prefix of and . In Case 1, it is , meaning that the character of in position |lcp()|+1 is smaller than in the one in the same position in . Thus, inserting # in position does not change the lexicographic order between and . The order is preserved.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the first case in Lemma 4. Inserting # does not change the lexicographic order between and .

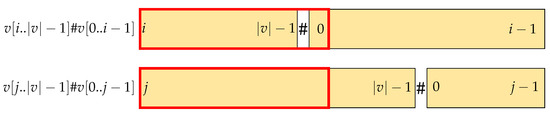

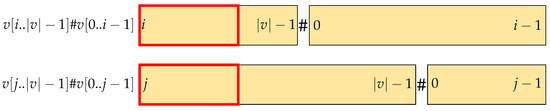

The red rectangle in Figure 3 depicting the longest common prefix of the two strings in question is longer than |lcp()|. In Case 2, it must be , which means . When it is , then , meaning that # appears first in . As a result, , which contradicts . Thus, in Case 2, we only consider when it is , as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the second case in Lemma 4.

Furthermore, we distinguish the second case between two subcases: We let u be unique circular factor which is smaller than all the other circular factors having the same length in v.

- Case 2 (a):

- when u is a prefix of ;

- Case 2 (b):

- when is a prefix of u.

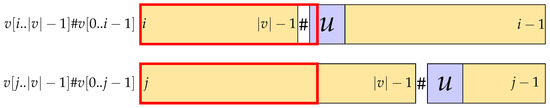

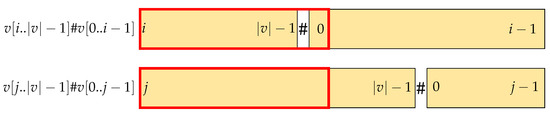

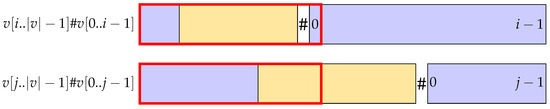

When it is Case 2 (a), u appears only in the prefix of . Thus, the first difference between and lies within the unique occurrence of u. The situation is depicted at Figure 4. After inserting the #, becomes , creating factor at position , which is not only unique but also smallest among other factors of length in v. Any factor that appears in the same position in is greater than . Thus, the order is preserved.

Figure 4.

Illustration of Case 2 (a) in Lemma 4. Inserting # in does not affect lexicographic order between and .

In Case 2 (a), u is the smallest prefix which appears only once in . v is a Lyndon word; thus, , it is also the smallest factor in v. However, in Case 2 (b), u is longer than . We sketch the situation in Figure 5, where we visualize u with a purple rectangle. Therefore, must appear more than twice in u. If appears only once, u is analogous with . Also, from , there must be a difference in . Moreover, since v is primitive, v cannot be expressed in the form for word Z and a integer . The first distinct character between is within . We assume otherwise that there is no mismatching character pair with and the prefix of , which is . Since , also has a smallest prefix and it contradicts with v, which is one and only Lyndon word. Moreover, becomes , thus contradicting its primitivity.

Figure 5.

Illustration of Case 2 (b) in Lemma 4.

In this way, after inserting a #, the analogous behavior of Case 2 (a) is observed.

The order of original conjugates of v is preserved with respect to the original BWT according to the cases above. Thus, the only difference in inserting # in v occurs in conjugates of and . On the one hand, we observe that is now the smallest among all conjugates of , and it ends with the last character of v. On the other hand, becomes the second smallest conjugate and ends with #. Hence, we have BWT() = , which concludes the proof. □

Theorem 1.

We let be the Fibonacci word of even order , and . We let be the word that results from substituting a by a # at position . Then, .

Proof.

We let . From Lemma 2, . And by Lemma 3, we know that is the smallest conjugate among . By Lemma 4, we have . More precisely, it is since is the smallest conjugate in and is the second smallest conjugate. The relative order among the conjugates of coincides with that of the conjugates of , using the same argument as in the proof of Lemma 4. This means that to obtain , it suffices to insert a # between the first two s in . Since , we obtain the claim. □

5. Additive Sensitivity of by

In Section 4, we presented a word such that substituting one of its characters by #, which is strictly lexicographically smaller than all its characters, resulted in a logarithmic multiplicative increase in the number of runs r in the BWT. We now follow (Giuliani et al. [24], Section 4), who presented a family of words where a single edit can produce an additive increase of in r. Like before, we want to study the sensitivity when introducing a new character (#) in Section 5.1 or additionally when inverting the order of the alphabet in Section 5.2.

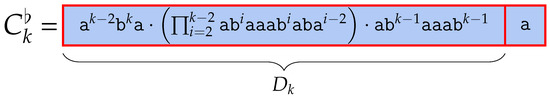

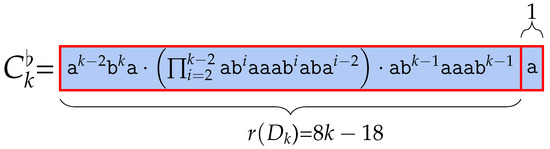

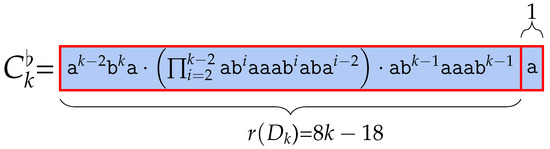

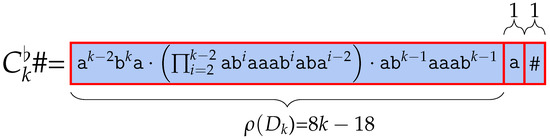

Definition 1.

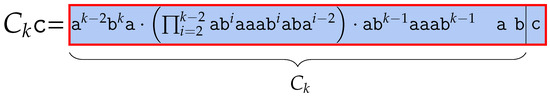

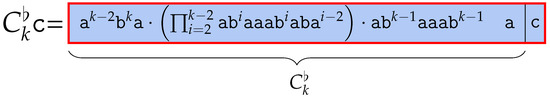

For any , we let and for all , and . Then,

The length of these words is

Thus, . is

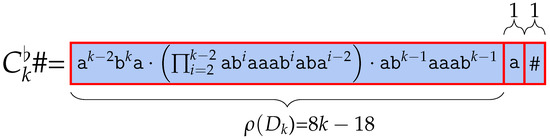

We append #, which is lexicographically smaller than character at the last part of and name the resulting word .

Also, , with its characters and swapped, is defined as , which is

To characterize the BWT of words , and , we partition each of the BWT conjugates , , into distinct groups of consecutive conjugates having identical prefixes and define the subword of BWT() corresponding to each of these prefixes.

Given , we denote by the subword of BWT corresponding to the range of contiguous conjugates prefixed by X. We omit the second parameter of when it is clear from the context. is the concatenation of the last characters of conjugates with prefix X. For example, when X is , there are two conjugates starting with the prefix which are and ; thus, () of is .

Lemma 5.

In Proposition 28 of [24], it is already known that .

5.1. BWT of After Substituting a Character

The lemmas presented below characterize the BWT of after certain modifications have been applied. Rather than deriving the entire structure of the BWT from scratch, we analyze how replacing a character affects either the relative order or the final character of the conjugates of . We let be the list of lexicographically sorted conjugates of the word .

Lemma 6.

.

Proof.

The first conjugate in is . Since the lexicographic order of # is smaller than all other characters, a conjugate starting with # is smaller than every conjugate starting with . # can be obtained by the last character of , which is preceded by a . □

Lemma 7.

= for all .

Proof.

Given integer , the conjugates of starting with are

In , a prefix can only be obtained by concatenation of the suffix of , with the prefix of or the prefix of of if . Note that all these conjugates end with an , with the exception of the conjugate starting with , since this is where the unique occurrence of can be found. □

Lemma 8.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

In , the conjugates that start with can be obtained for all from the concatenation of the suffix from with or with if . If , concatenation of the suffix of with the prefix of also makes . Also, we can sort the conjugates with following order: . All conjugates of end with a and if , of concatenated with or if also ends with . On the other hand, ends with . □

Lemma 9.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

Each of the conjugates starting with from Lemma 8 induces a conjugate starting with , obtained by shifting on the left one character . It follows that all of these conjugates end with an . The other conjugates that start with are those obtained by concatenating the suffix of with the prefix of which ends with . □

Lemma 10.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with the prefix are

For all two distinct integers with , we have . Thus, the first conjugate in the lexicographic order starting with is the one followed by the longest . The smallest of these conjugates can be found from the suffix of , followed by the suffix of for all taken in decreasing order.

By construction of , for all , these conjugates must end in a . The remaining conjugates starting with are exactly those of either or , for all , or . The conjugates can be obtained by shifting on the left one character from the conjugates starting with from Lemma 9, with the exception of one starting with since it ends with a , and the other starting with which ends with #, while the other conjugates end with an . □

Lemma 11.

for all .

Proof.

The conjugate in starting with for all is . This conjugate can be obtained by a suffix of , and is always preceded by a . □

Lemma 12.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

We have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal character runs of in . Then, for all ,

- Case 1:

- one run of in and

- Case 2:

- two runs in .

For Case 1, we have one conjugate starting with for each . Since each run of within each word of is of length of at least 2, all conjugates in (1) end with . For Case 2, for all we can distinguish between two subcases, based on where starts:

- Case 2 (a):

- from the first run of in , which is when or if . Since has at least 2 runs, conjugates with prefix (2.1) always end with .

- Case 2 (b):

- from run for all , and . Each conjugate of Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters to the right in each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, these conjugates end with an .

Observe that only for Case 2 (b) we have conjugates starting with . Hence, the first conjugate in the lexicographic order is the one starting with , followed by those starting with .

Among the remaining conjugates, those that have the prefix start with from Case 2 (b) or from Case 2 (a). Thus, we can sort them according to lexicographic order. Then, the remaining conjugates, which start with , are obtained by only. Finally, let us focus on the conjugates from Case 2 (a), which start with . These conjugates are sorted according to the length of the runs of s following the common prefix , similarly to the sorting of conjugates from Case 2 (b). The last conjugate left is the one starting with from Case 2 (b). Since is lexicographically greater than all other cases, this is the greatest conjugate of starting with and we can conclude our claim. □

Lemma 13.

for all .

Proof.

The conjugates starting with with integer in are

All runs of of length at least appear in either

- Case 1:

- or

- Case 2:

- for all .

Let us consider these two cases separately. For all , the conjugate starting within has prefix . For all , the conjugate starting within has prefix , and for , we have the conjugate with prefix . By construction, we have all the conjugates from Case 1 sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words with respect to the length of the run by obtained by .

The conjugates covered by Case 2 are sorted according to the decreasing length of the run of , following the common prefix . Only when the run of is exactly i long, its conjugate ends with . Thus, the conjugates ending with an are those starting with and , which have prefixes and . □

Lemma 14.

.

Proof.

The two conjugates in which start with are

The conjugates with the prefix start with or . These conjugates have prefixes of and , respectively. One can see that these conjugates taken in this order are already sorted, and both conjugates end with . □

Lemma 15.

.

Proof.

The last conjugate in is . The last conjugate in lexicographic order starts with , and since the run of is maximal, it ends with , and the claim follows. □

In conclusion, we define the above theorem.

Theorem 2.

for every .

Proof.

The BWT of the is BWT() =. We refer to Table 2. Moreover, which has more runs than , cf. Lemma 5.

Table 2.

Classification of the number of runs obtain in Theorem 2. The total number of runs is .

The lexicographic order of # is lower than an , and a conjugate starting with # is smaller than any conjugate starting with . Moreover, every conjugate in is smaller than every one in , for every . In addition, every conjugate contributing a character to is smaller than a conjugate contributing a character to for every . And with a conjugate starting with , the number is smaller than that of . Since we considered all the disjoint ranges of conjugates of based on their common prefix, the word BWT() is . With the structure of BWT(), we can derive its number of runs. The words and have runs: we start with 1 run from = which is merged by = . And concatenating them up to adds 2 new runs each. , (), () have , 3, 5 runs, respectively. However, the boundaries between and () are merged by an ; therefore, has 2 runs. has 1 run, followed by which makes 7 runs. Then, and () repeat, making 1 and 3 runs until thus makes runs. adds 1 run. Also, adds 1 run and is the last run since does not add new runs, since it consists only of a that merges with the previous one. Altogether, we have , and the claim holds. The main difference in the runs of and occurs from the prefix beginning with that concatenates with , repeating for , while repeats only . Thus, it makes additive runs of .

Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and , Table 7 . The first column partitions conjugates by common prefixes and names the common prefix shared by all conjugates in a partition. The second column shows the remaining part of the respective conjugate followed by the prefix of its partition. The remaining part of a conjugate decides its relative order inside its partition. The BWT column shows the last character of each conjugate. □

Table 3.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 2, Part 1.

Table 4.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 2, Part 2.

Table 5.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 2, Part 3.

Table 6.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 2, Part 4.

Table 7.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 2, Part 5.

5.2. BWT of After Substituting a Character

In this subsection, we consider the word , where we swapped with in . The following series of lemmas characterize the subword of BWT() using for each range we consider.

Lemma 16.

.

Proof.

The first conjugate in is The first conjugate in lexicographic order must start with the longest run of s. By the definition of , the longest run of has length k, which is obtained by of , which is preceded by a . □

Lemma 17.

for all .

Proof.

With integer , the conjugates starting with in are

For all , the factor of can only be obtained for all , from from , or from , and if , from . We can sort the conjugate according to the lexicographic order. Note that all these conjugates end with , with the exception of the conjugate starting with obtained by and ending with . □

Lemma 18.

.

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with are

We have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal (circular) runs of in . Then, for all , we have three cases.

- Case 1:

- one run of in ,

- Case 2:

- two runs in in ,

- Case 3:

- one run in .

For Case 1, we have one conjugate starting with , for each . Since each run of within each word of is of length at least 2, all conjugates in Case 1 end in . For Case 2, for all , we can distinguish between two sub-cases based on where starts.

- Case 2 (a):

- from the first run of in , starting with , if , or ,

- Case 2 (b):

- from the second run in , starting with , if , or .

Similarly to Case 1, each conjugate for Case 2 (a), ends with . Each conjugate in Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters on the right in each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, all these conjugates end with .

For Case 3, the conjugate starting with in has as a prefix and is preceded by . Observe that only for Case 2 (b), we have one conjugate that starts with obtained by and it is the first conjugate in the lexicographic order of . Then, the conjugates start with followed by from Case 2 (a).

Among the remaining conjugates, those with the prefix start with from Case 2 (b) or from Case 3. Then, among the left conjugates, the conjugate with the prefix from Case 2 (a), for all , or from Case 2 (b) follows. The last remaining conjugates have the prefix for or , which can be obtained by Case 2 (b). Since is greater than all other conjugates, it is the greatest conjugate of starting with and we conclude this proof. □

Lemma 19.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in that start with are

For integer i, we can see that is lexicographically smaller than . Thus, the first conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is the one followed by the longest run of , and it can be found by of , followed by conjugates starting with of and of for all taken in decreasing order. By construction of , for , these conjugates must end with a . Otherwise, for , conjugates also end with , with the exception of a conjugate starting with , since it is preceded by an from . The remaining conjugates starting with are exactly those conjugates that have the prefix of the suffix if or . All of these conjugates end with , since they are preceded by . □

Lemma 20.

.

Proof.

The conjugates starting with in are

These conjugates are obtained by following four cases.

- Case 1:

- concatenating suffix of with for all ,

- Case 2:

- concatenating suffix of with for all ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating suffix of with ,

- Case 4:

- concatenating suffix of with .

The first conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is the one followed by the longest run of . The smallest of these conjugates can be found by Case 3, concatenation of the suffix of with . We can directly observe that holds for every integer . Thus, the next conjugate will have the prefix from Case 1 and from Case 2 repeating in decreasing order. Since of Case 1 and of Case 3 is preceded by a , those end with a . On the other hand, precedes for all until appears since it precedes an . Lastly, conjugates with the prefix and by Case 1 end with a . The greatest lexicographic conjugate is from Case 4 as it has the smallest runs of which is two and ends with .

We can sort all of these conjugates according to the order of the words in

□

Lemma 21.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

Some of the conjugates starting with can be obtained by two cases.

- Case 1:

- from the concatenation of the suffix of with a prefix of of for allor if ;

- Case 1:

- from the concatenation of the suffix of with prefix of for all .

Thus, all conjugates starting with are sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in All conjugates starting with for all or in Case 1 end with . Otherwise, conjugates starting with of Case 1 or for all of Case 2 end with . □

Lemma 22.

for all .

Proof.

All runs of of length of a range appear only by concatenating suffix of with prefix of for all in decreasing order. All of these conjugates end with a , with the exception of a conjugate which ends with an since suffix precedes an . Hence, the last conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is within and since the run of is maximal it ends with , and the claim follows. □

The following theorem presents the shape of the BWT of .

Theorem 3.

Table 8.

Classification of the number of runs obtained in Theorem 3. The total number of runs is .

Proof.

Let us put the result from Lemma 16 to Lemma 22 together. Every conjugate of contributing a character to is smaller than a conjugate contributing a character to , for every . Symmetrically, every conjugate in is greater than every conjugate in , when . Since we considered all the disjoint ranges of conjugates of based on their common prefix, the word is the BWT of .

With the structure of BWT(), we can derive its number of runs. The word has exactly runs: we start with 1 run from but it is merged by a from . Then, concatenating each up to adds 3 runs each. However, the boundaries between these words merge because appears continuously. Thus, each for makes 2 runs each. By counting, we observe that runs 7 times. The remaining part of the BWT, that is, has runs: the word , has 4 runs, but the first merges with a from , so we only charge 3 runs for this word. Then, and add 4 and runs, respectively. Finally, runs for 2 until . The word does not add new runs, as it consists only of an that merges with the previous one. Altogether, we have , and the claim holds. □

The following lemmas describe the BWT of after applying one specific edit operation. is a word obtained by replacing the last character of with , where is lexicographically larger than . The number of runs in the BWT of can be derived by comparing the BWT of to the BWT of , for which we explicitly counted the number of runs, so we omit these parts of the proof using , which is a list of lexicographically sorted conjugates of word . Substituting the last character with in also increases the number of runs by .

Lemma 23.

.

Proof.

The first conjugate in starts with . The first conjugate in lexicographic order must start with the longest run of . By the definition of , the longest run of is obtained by suffix of , preceded by a . □

Lemma 24.

for all .

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with the prefix for are

For every integer , the conjugates in starting with can only be obtained from two cases:

- Case 1:

- of for all ,

- Case 2:

- of for all .

We can sort these conjugates according to the lexicographic order of . Note that all these conjugates end with an , with the exception of the conjugate starting with and , since these are the only places where the occurrence of can be found. □

Lemma 25.

for all .

Proof.

The only conjugate in starting with for all has a prefix of . For all two distinct integers with , we have . Also, since the lexicographic order of a word in is , it is also clear that . The conjugates starting with are obtained from from and since the length of is k, all conjugates with with end with . □

Lemma 26.

.

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with are

We have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal runs of in . Then, for all , we have two cases.

- Case 1:

- one run in obtained by concatenating suffix of with , for each , and

- Case 3:

- two runs in .

For Case 1, since each run of within each word of is of length of at least 2, all conjugates in Case 1 end with an .

For Case 2, for all , we can distinguish between two sub-cases, based on where starts, if either

- Case 2 (a):

- from the first in or

- Case 2 (b):

- from the second in .

For Case 2 (a), we can see that these conjugates are of the type if or . Similarly to Case 1, each conjugate for Case 2 (a) ends with . Each conjugate in Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters on the right each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, all of these conjugates end with a and have prefix of type , if or . All these conjugates end with a since is preceded by . Observe that only for Item Case 2 (b), we have conjugates starting with which is . Hence, it is the first conjugate in lexicographic order, followed by those starting with from Item Case 2 (a) and these conjugates start with .

Next, conjugates with a prefix of which is from Case 2 (b) follow, then those having prefix either start with for all from Case 1 follow in decreasing order. Then, from Case 2 (b) and , , from Case 1 follow.

The remaining conjugates are those which start with a prefix of for , which are obtained by if or , from Case 2 (b). These conjugates are sorted according to the length of the run of following the common prefix. Then, the result is

□

Lemma 27.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with the prefix are

There are many occurrences of a conjugate starting with the prefix , and it occurs in three parts.

- Case 1:

- one run of in , for all ,

- Case 1:

- two runs from , for all ,

- Case 1:

- one run from .

The conjugates in Case 1 start with for all . Since if only , the conjugates are sorted in decreasing order. All conjugates for end with a , except for conjugates with prefix since it is preceded by .

In Case 2, we can distinguish between two sub-cases based on where starts:

- Case 2 (a):

- first run of from the prefix of ,

- Case 2 (b):

- from the second run of in .

The conjugates in Case 2 (a) are the type of , if or . All of these conjugates are preceded by , thus ending with . The conjugates in Case 2 (b) start from if or and end with an .

In Case 3, only one conjugate can be found by a prefix of , which ends with .

Observe that only for Case 3 we have a conjugate with the longest run of after . Hence, the first conjugate in lexicographic order is from Case 3. It is followed by . All of these conjugates end with a .

Among the remaining conjugates, those having prefix either start with from Case 2 (a) or from Case 1. Then, the remaining conjugates with prefix are those starting with from Case 2 (a) or from Case 1. Lastly, conjugates from Case 2 (b) follow, which are for all or . All of these conjugates end with an .

We prove our claim by sorting lexicographically the conjugates in

□

Lemma 28.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with prefix are

The smallest conjugate with prefix can be obtained by three cases.

- Case 1:

- concatenating suffix of with ,

- Case 2:

- concatenation of suffix of with if or ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating suffix of with , for all .

The conjugates in Case 1 and Case 3 end with . Also, conjugates from Case 2 end with with an exception of a conjugate starting with since it is preceded by an . We conclude this proof by sorting lexicographically the conjugates in

□

Lemma 29.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with the prefix are

Analogously to Lemma 28, the conjugates starting with can be obtained from three cases.

- Case 1:

- concatenating suffix of with ,

- Case 2:

- concatenation of suffix of with if or ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating a suffix of with , for all .

The conjugate in Case 1 is the smallest conjugate starting with since it has a longest run of and ends with a . In addition, the conjugates of Case 3 end with a since are preceded by an . In Case 2, all the conjugates end with with an exception of a conjugate starting with since it is preceded by an . We can sort these conjugates by

□

Lemma 30.

for all .

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with prefix for all are

Observe that the only conjugates with the prefix for start with concatenating either to or if . One can see that these conjugates taken in this order are already sorted, and all conjugates end with a , with the exception of a conjugate starting with , since it is preceded by an , therefore ending with an . We have all conjugates ordered according to the lexicographic order of the words in. This concludes our proof. □

Lemma 31.

.

Proof.

The only conjugate in that starts with prefix is . Since is lexicographically larger than other characters such as , , it is the biggest conjugate in , and it ends with an . □

The following theorem puts the lemmas above together.

Theorem 4.

Table 9.

Classification of the number of runs obtain in Theorem 4. The total number of runs is .

Proof.

Every conjugate contributing a character to is smaller than a conjugate contributing a character to for every . By symmetry, every conjugate contributing a character to is greater than each conjugate contributing a character to for every . With the structure of the BWT of , we can easily derive its number of runs. has exactly runs: we start from 1 run from but it is merged with . and add 2 runs. Then, concatenating each and for all in a decreasing order, we add 3 and 1 runs each, which results in runs. By counting, we observe that adds 7 and 1 runs, respectively.

The word has exactly 5, 3, runs each, but since the boundaries between and merge, the first of does not count, turning into . The remaining part of BWT, that is, has runs: we start by concatenating each up to , which adds 2 runs each. The last does not add new runs, as it consists only of an that merges with the previous one. Altogether, we have , and the claim holds.

The main difference between and comes from that is concatenated with for , which repeats , while repeats only, making more runs. Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 describe the scheme of the BWT of word . We have ) = . From Definition 1, we have . Thus, . □

Table 10.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 4, Part 1.

Table 11.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 4, Part 2.

Table 12.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 4, Part 3.

Table 13.

Lexicographically sorted conjugates of studied in Theorem 4, Part 4.

6. Multiplicative Sensitivity of by

Recall that . In this section, we return our attention to Fibonacci words. Similar to Section 4, we use them to construct a family of words with a multiplicative sensitivity of for the number of runs in the BBWT. Before that, we start with some helpful lemmas known in the literature.

Lemma 32.

([41], Lemma 3). The th Fibonacci word is . The Lyndon conjugate of the Fibonacci word is .

Lemma 33.

([37], Lemma 6). We let be the Lyndon conjugate of the Fibonacci word . Then, r(BBWT())= 2.

Lemma 34.

([41], Lemma 8). If , then the Lyndon conjugate of is a prefix or a suffix of . If , then its Lyndon conjugate is a prefix of ; and if , then its Lyndon conjugate is a suffix of .

The next lemma addresses the extended Burrows–Wheeler transform [16], which takes a subset of steps from the BBWT by expecting the input to be a set of primitive words (i.e., the Lyndon factors in case of the BBWT). We translate the following known result to the BBWT:

Lemma 35.

(Corollary 4 of [47]). We let be a conjugate-free set of primitive words and let be the number of runs of its extended Burrows–Wheeler transform. Then, .

Corollary 1.

We let be the Lyndon factors of word T, then .

In what follows, we establish a lower bound on the multiplicative sensitivity of with the Lyndon conjugates of Fibonacci words by leveraging Corollary 1.

6.1. Editing the Last Position of

We start with deleting the last character of , which directly leads to the following insight.

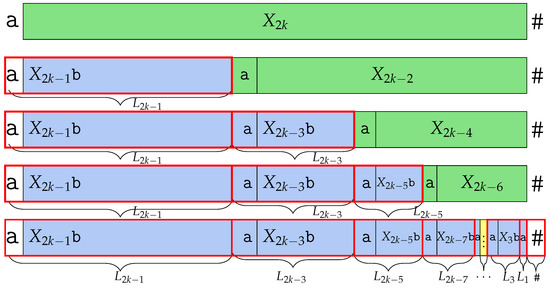

Theorem 5.

.

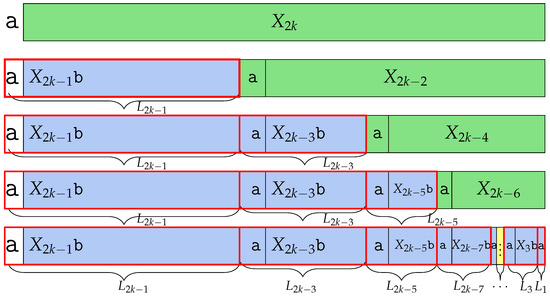

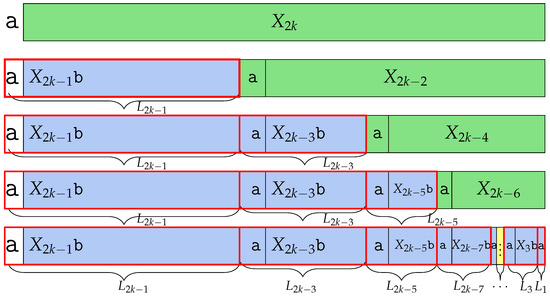

Proof.

is not a Lyndon word; therefore, its Lyndon is factorized and has more than one factor. According to Lemma 34, the Lyndon word of the Fibonacci word is . The central word is , so the Lyndon word of is . refers to , which is and the suffix is .

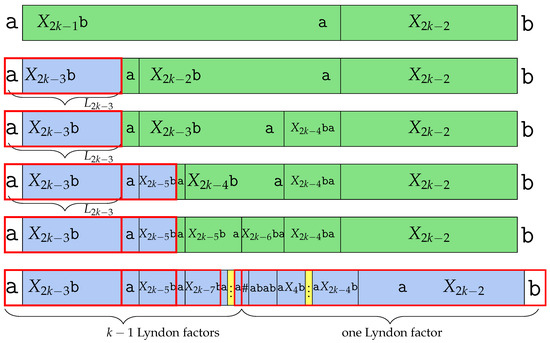

However, by deleting the last character , becomes , meaning that does not exist. Thus, we can say that is one of the Lyndon factors, since it is not followed by . The remaining part of is . The same as , central word can be divided as ; thus, . We can find Lyndon factor in the prefix. The remaining part is , which is not a Lyndon word, same as above, so is Lyndon factorized and makes as a prefix, and the remaining makes as a prefix. And finally, is divided as , where is . Therefore, ’s Lyndon factor is for and the last remaining part is the Lyndon word itself. Thus, has Lyndon factors for every and as a Lyndon factor. The number of the Lyndon factor is k, which we depict in Figure 6. □

Figure 6.

Factorization of into Lyndon factors studied in the proof of Theorem 5. has k Lyndon factors.

By Lemma 33 and Theorem 5, we conclude that the multiplicative sensitivity for deleting the last character of is .

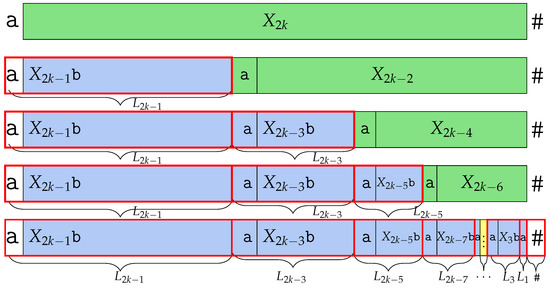

Theorem 6.

We let be the word obtained by substituting the last character of by #. Then,

Proof.

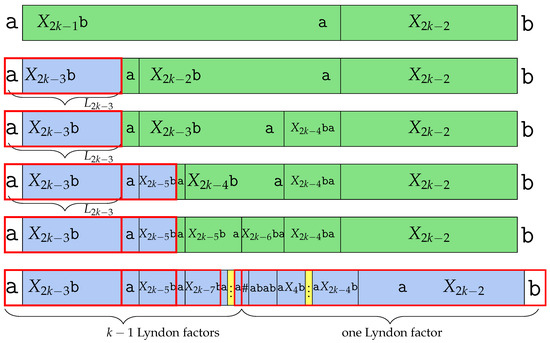

Since # is lexicographically smaller than , is not a Lyndon word; it makes Lyndon factors. Since # is smaller than both and , # is a Lyndon word. In addition, is Lyndon factorized as Theorem 5, which produces Lyndon factors for and the last Lyndon factor . makes one more Lyndon factor, which is #, which therefore makes a number of Lyndon factors. We depict the Lyndon factorization in Figure 7. □

Figure 7.

Factorization of into Lyndon factors studied in the proof of Theorem 6. has Lyndon factors.

By Lemma 33 and Theorem 6, we conclude that the multiplicative sensitivity for substituting the last character of is . We observe a similar result when substituting the last character with a larger character instead of a smaller one (#).

Theorem 7.

.

Proof.

The lexicographic order between , , and is . Recall that makes for , and as a Lyndon factor. In , is in position ; therefore, it does not affect anything until the last Lyndon factor . is the Lyndon word itself because . Therefore, makes a k number of Lyndon factors, shown in Figure 8. □

Figure 8.

Factorization of into Lyndon factors studied in the proof of Theorem 7. has k Lyndon factors.

6.2. Insertions at Specific Locations

According to Corollary 1, is lower bounded by the number of distinct Lyndon factors. After editing at any position, we can still find consecutive Lyndon conjugates of lower order which can merge to a higher order. For instance, merge into , which can decrease the number of the Lyndon factor. Also, merge into . Our idea is to avoid consecutive Fibonacci Lyndon conjugates so that they do not merge because doing so avoids a decrease in a number of distinct Lyndon factors. Now, we consider editing the specific location of Fibonacci Lyndon conjugates, also resulting in an increase in runs. The following theorems describe the bijective BWT of after some specific edit operations are applied.

Theorem 8.

We let be a Fibonacci Lyndon conjugate. By inserting at position α in , ρ is at least k.

Proof.

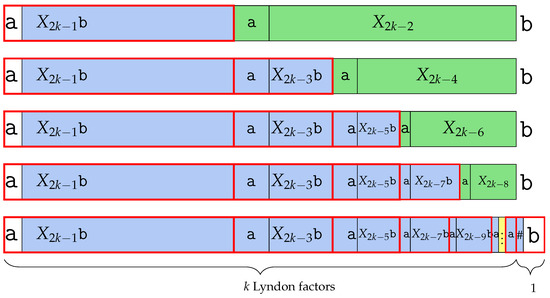

We let be the number of additions of odd Fibonacci numbers . Recall that the Fibonacci word with has the Lyndon conjugate . Further, . Thus, we start with . To obtain many distinct Lyndon factors, we aim to produce Lyndon factors that are not consecutive. Knowing , merges with into , so it is best to divide . divides into . In this case, it is best to add as a new Lyndon factor since it is smallest among those Lyndon factors that are not consecutive with , the same as ; divides into , and we add as a Lyndon factor. divides into as we add as a Lyndon factor. The addition of Lyndon factors of for continues until appears since is the second smallest Lyndon factor in Fibonacci. Thus, we need as the last Lyndon factor and it is obtained by inserting a # in , dividing into . Since # is lexicographically smaller than any words from right to #, the right words become the Lyndon factor. Thus, we can obtain k Lyndon factors by inserting # in : factors from and one from # concatenated with the remaining words. And this is shown in Figure 9. □

Figure 9.

Inserting # at position in considered in the proof in Theorem 8.

By Lemma 33 and Theorem 8, we conclude that the multiplicative sensitivity for inserting a character into is . In the same way, we can also insert the special character # to observe a similar behavior:

Theorem 9.

We let be a Fibonacci Lyndon conjugate. By inserting # at position in , ρ is at least .

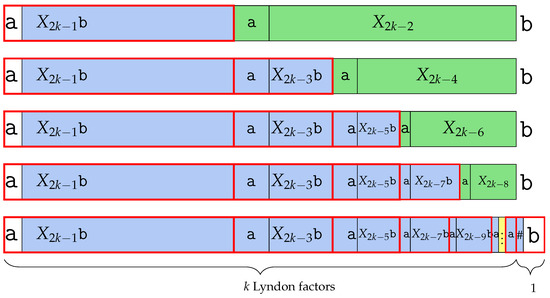

Proof.

Unlike Theorem 8, we can obtain some Lyndon factors on the right side of , adding as a Lyndon factor. We divide into and obtain . Further, we divide into , making . We divide and can obtain Lyndon factors such as . Lastly, divides into , but since is , the last Lyndon factor obtained here is . To make more Lyndon factors, we can add # between and , turning into , adding 2 Lyndon factors which are and . Thus, we can obtain Lyndon factors here: k factors by and one from . We visualize the Lyndon factorization in Figure 10. □

Figure 10.

Insertion of # at position in increases by at least the number of distinct Lyndon factors studied in Theorem 9.

7. Additive Sensitivity of by

Here, we study the additive sensitivity of with an approach similar to Section 5. In what follows, we establish that the additive sensitivity of is at least . To that end, we again make use of the word . Recall that .

Lemma 36.

The Lyndon conjugate of is .

Proof.

The Lyndon conjugate of starts with the longest runs of , which can be obtained by concatenating suffix of with prefix of . Therefore, . □

Lemma 37.

= .

Proof.

According to Lemma 1, all conjugates have the same BWT, thus . Also, since is a Lyndon word, . □

Recall that the runs in the BBWT and BWT are the same if the input word is Lyndon, cf. Lemma 1. Thus, we can leverage BWT computation if the input word is Lyndon since we can obtain the number of runs in the same way as in Section 5 by using for word W. In this section, we focus on three variations of the word : deleting its last character and substituting its last character with or #.

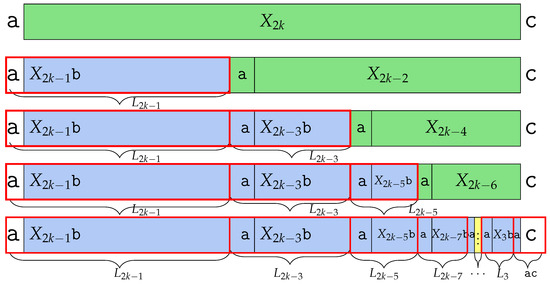

7.1. Deletions and Edits of with a Character Smaller than

Recall that . Thus, , which is obtained by deleting the last character , is . Recall that the Lyndon conjugate of is the strictly smallest conjugate of all conjugates of . Since we obtain the longest runs of s from a conjugate of by concatenating the last with , cannot be a Lyndon word. In fact, it has two Lyndon factors, which are , and we refer to both Lyndon factors as (first factor) and from now on. Figure 11 shows the Lyndon factorization. Since is 1, the only thing left to check is . In , we made a slight modification to the subword . In fact, was changed to , which we call in this section. Since is a Lyndon word, we determine using with the BWT as we did before.

Figure 11.

Introducing from studied in Section 7.1. is the first Lyndon factor of .

Lemma 38.

.

Proof.

The only conjugate in starting with prefix is . The first conjugate in lexicographic order must start with the longest run of . By the definition of , the longest run of has length , and it is obtained by concatenating suffix with prefix of that is preceded by (otherwise, we could extend the sequence of characters). □

Lemma 39.

, for all .

Proof.

With integer , the conjugates in starting with are

For all , the factor can only be obtained from the concatenation of suffix from ,

- with the prefix of for a or

- with the prefix of , if .

We can sort these conjugates according to the lexicographic order of . All these conjugates end with an , with the exception of the conjugate starting with , since has a unique occurrence of . □

Lemma 40.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

The above conjugates are obtained in the following cases.

- Case 1:

- by concatenating the suffix of with the prefix of , if only ,

- Case 2:

- by concatenating the suffix of , with the prefix of , for all or with if ,

- Case 3:

- by concatenating the suffix of with the prefix of .

All these conjugates starting with are sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in The conjugates starting either with , for all in Case 1 or Case 3, end with an . On the other hand, conjugates of Case 2 or in Case 1 end with a . □

Lemma 41.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

Each of the cases from Case 1 to Case 3 in Lemma 40 induces a conjugate starting with , obtained by shifting on the left character . It follows that all of these conjugates end with . The other two conjugates that start with an are obtained by

- concatenating the suffix of with the prefix of or

- concatenating suffix of to the prefix of .

In both cases, the obtained conjugates end with . We conclude this proof by sorting lexicographically the conjugates in □

Lemma 42.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

The above conjugates are obtained in the following cases.

- Case 1:

- for all ,

- Case 2:

- prefix of , for all ,

- Case 3:

- from , for all or from ,

- Case 4:

- from .

For two distinct integers with , we have . Thus, the first conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is the one followed by the longest run of s. The smallest of these conjugates can be found by concatenating the suffix with the prefix of from Case 3. Then, the remaining conjugates in Case 3 which are of for all follow in decreasing order. By construction of , for all , these conjugates must end with a . Note that the remaining cases are obtained by shifting the character from the conjugates starting with from Lemma 41 with the exception of the character starting with . It follows that the latter ends with a , while all the other conjugates end with . □

Lemma 43.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

The conjugates above are obtained by following cases.

- Case 1:

- suffix of concatenating with for all or if ,

- Case 2:

- runs in for all ,

- Case 3:

- suffix from concatenating with ,

- Case 4:

- of concatenating with .

We have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal runs of s in . For Case 1, we have one conjugate starting with for all or . Since each run of s within each word from is of length of at least 2, all conjugates of Case 1 end with .

For Case 2, for all , we can distinguish two subcases based on where starts:

- Case 2 (a):

- the first run of in , which has a type of for all ,

- Case 2 (b):

- the second run of in , which has a type of for all .

- For Case 2 (a), we can see that these conjugates start with if . Similarly to Case 1, each conjugate for Case 2 (a) ends with a . Each conjugate in Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters on the right each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, all of these conjugates end with an and have prefixes of the type , if .

- For Case 3, the conjugate starting with in has as a prefix, and it is preceded by a .

- Lastly, for Case 4, the conjugates start with concatenating with which ends with a .

- Observe that only for Case 4 and Case 2 (b) we have conjugates starting with . Hence, the first conjugate in lexicographic order is the one from Case 4 starting with , followed by those from Case 2 (b) which are .

Among the remaining conjugates, those having prefix either start with from Case 2 (b) and from Case 1 starting with for all or if . We can sort them according to the order of the words in

Then, the remaining conjugates with prefix are those starting with from Case 3 and from Case 2 (b). Finally, let us focus on the conjugates from Case 2 (a). These conjugates are sorted according to the length of the run of s following the common prefix . The last conjugate left is the one starting with from Case 2 (b). Since this conjugate is greater than each conjugate considered in Case 2 (a), this is the greatest conjugate of starting with and the thesis follows. □

Lemma 44.

for all .

Proof.

With integer , the conjugates in starting with the prefix are

- Case 1:

- concatenating of with for all or with if only ,

- Case 2:

- concatenating of with if only ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating of with ,

- Case 4:

- concatenating with .

We consider these four cases separately. For all , the conjugate starting within has a prefix of or (Case 1). For all , the conjugates starting within have a prefix of (Case 2). In addition, conjugate starting within a word in Case 3 has a prefix of . Finally, the conjugates starting with starts with (Case 4). By construction, we can see that first we have all the conjugates first from Case 3 and then from Case 1 sorted according to the lexicographic order into ; then, we have the conjugate from Case 4, then Case 2 sorted according to the decreasing length of the run of s following the common prefix . Moreover, we note that only when the run of s is exactly of length , the conjugate ends with . Thus, only the conjugates ending with an are those starting within and . □

Lemma 45.

β()= .

Proof.

There are three conjugates in starting with prefix . These conjugates are

Observe that the only conjugates with prefix have the prefixes, respectively, of , , and . One can see that these conjugates taken in this order are already sorted, and only the conjugate starting within ends with , while the other two have . □

Lemma 46.

.

Proof.

The last conjugate in with prefix is . Finally, the only occurrence of is within . Hence, the last conjugate in lexicographic order starts with , and since the run of ’ is maximal, it ends with an , and the thesis follows. □

We summarize the above lemmas as follows.

Lemma 47.

For integer, , cf. Table 14. The BWT of the word is given by .

Table 14.

Classification of the number of runs obtain in Lemma 47. The total number of runs is .

Proof.

Every conjugate of is smaller than each conjugate of for every . Symmetrically, every conjugate of is greater than any conjugate of , for every . Since we considered all the disjoint ranges of conjugates of based on their common prefix, the word is the BWT of .

With the structure of , we can easily derive its number of runs. The word has exactly runs. We start with 2 runs from and then, concatenating each up to adds 2 new runs each. By counting, we observe that have , 4, 4. The boundaries between these words do not yet merge. The word has exactly 8 runs. The remaining part of the BWT, that is, , has runs. Concatenating each to adds 4 new runs each. The word adds only one run by , as it contains an that merges with the previous one. Finally, adds one run. Altogether, we have , and the claim holds. □

Using Lemma 47 above, we can finally obtain the runs of .

Theorem 10.

.

Proof.

. The Lyndon conjugate of is the smallest conjugate starting with the longest runs of , thus it is the one starting with . Therefore, it is obvious that is not a Lyndon word, then it is Lyndon factorized by an and the residual which is . Figure 12 depicts the Lyndon factorization of . Since the lexicographic order between and is , the runs of add one run because the first conjugate of from Lemma 38 ends with a . Therefore, . □

Figure 12.

Lyndon factorization of . We obtain by knowing the number of runs of both its Lyndon factors and where these conjugates are sorted in the BBWT. The analysis is in the proof of Theorem 10.

With Lemma 37 and Theorem 10, we determine that the additive sensitivity of for is when deleting the last character.

Theorem 11.

#)= .

Proof.

# = #. is Lyndon factorized into three parts, which are , and #, because the lexicographic order of is lower than , and moreover # is smaller than both and . Therefore, the . We show a sketch in Figure 13. □

Figure 13.

Lyndon factorization of . Compared to Figure 12, we have one additional Lyndon factor. The analysis is in proof of Theorem 11.

With Lemma 37 and Theorem 11, we obtain that the additive sensitivity of for is when substituting the last character.

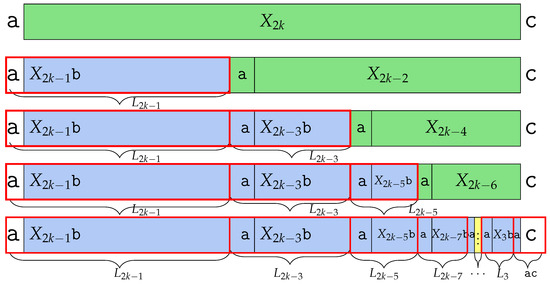

7.2. Editing with a Character Larger than

Now, we consider the editing operation with a character that is lexicographically larger than any character in . In this part, we consider two edit operations that add in the last part of , and substitute the last character of into .

7.2.1. Appending to

Now, we prove that adding to , i.e., becomes , also adds in runs in BBWT. . We illustrate in Figure 14. Similar to Section 7.1, we slightly modify to . In this section, we call this modified subword . The lexicographic order of is larger than any words in . Thus, is a Lyndon word itself. Recall that the runs of a Lyndon word are the same in both the BWT or the BBWT, so we obtain by using BWT with the same way we did in previous lemmas.

Figure 14.

Introducing the Lyndon word studied in Section 7.2.

Lemma 48.

.

Proof.

The first conjugate in is . The first conjugate must start with the longest run of s. In , the longest run of has a length of which is a prefix of itself, and it is obtained by concatenating the suffix of with , and it is preceded by a . □

Lemma 49.

for all .

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with for are

For all , the factor can only be obtained, for all , from the concatenation of the suffix of with prefix of , if or from the concatenation with of with prefix of . We can sort these conjugates according to the lexicographic order of . Note that all these conjugates end with an , with the exception of the conjugate starting with , since it is here the only occurrence of can be found. □

Lemma 50.

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with are

Similarly to Lemma 49, can be obtained from concatenation of the suffix of , with the prefix of , if , or concatenating of with prefix of . On the other hand, there are more conjugates from concatenating suffix of to the prefix of , for all , or with if . All the conjugates starting with are sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in . Note that all the conjugates starting either with , for all , or with , end with . On the other hand, the conjugates starting either with or with , for all or , end with . □

Lemma 51.

.

Proof.

The conjugates starting with in are

Each of the conjugates starting with from Lemma 50 induces a conjugate starting with , obtained by shifting one character on the left . It follows that all of these conjugates end with . The other conjugates starting with are the ones obtained by concatenating the suffix of and the prefix of , and the one obtained by concatenating the suffix of and the prefix of . Moreover, both conjugates end with a . We conclude this proof by sorting lexicographically the conjugates in . □

Lemma 52.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with are

For all two distinct integers with , we have . Thus, the first conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is the one followed by the longest run of s. The smallest of these conjugates can be found by concatenating the suffix of with , followed by the suffix of concatenated with , for all , taken in decreasing order. By construction of , for all , these conjugates all end with a . The remaining conjugates starting with are exactly those conjugates that have as prefix either or , for all , , or . Note that all of these conjugates are obtained by shifting one character on the left from the conjugates starting with from Lemma 51, with the exception of one starting with . It follows that the latter ends with a , while all the other conjugates end with . Finally, the conjugate starting with the prefix follows, which ends with . □

Lemma 53.

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with are

We have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal runs of in . We have four cases.

- Case 1:

- one run of s in , for all ,

- Case 2:

- two runs in for all ,

- Case 3:

- one run of in ,

- Case 4:

- one run of in .

For Case 1, we have one conjugate starting with , for each , or . Since each run of s within each word from is of length of at least 2, all conjugates in Case 1 end with a .

For Case 2 and all , we can distinguish between two subcases based on where starts:

- Case 2 (a):

- a first run of in , which has a type of for all ,

- Case 2 (b):

- a second run of in , which has a type of for all .

- For Case 2 (a), we can see that these conjugates are of the type , for . Analogously to Case 1, each conjugates for Case 2 (a) end with a . Each conjugate in Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters on the right each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, all of these conjugates end with an and have prefixes of the type , for all .

- For Case 3, the conjugate starting with in has as prefix, and it is preceded by a .

- Finally, in Case 4, there is one run of , having a prefix of , ending with .

- Only for Case 2 (b) we have conjugates starting with . Hence, the first conjugate in lexicographic order is the one starting with , followed by those .

Among the remaining conjugates, those having prefix either start with from Case 2 (b) or from Case 1, for all or if . We can sort these conjugates by following the order of . Then, the remaining conjugates with prefix are those starting with from Case 3 and from Case 2 (b). Finally, we focus on the conjugates from Case 2 (a). These conjugates are sorted according to the length of the run of s following the common prefix . The last two conjugates left are one starting with from Case 2 (b), and the one from Case 4, which is . These two conjugates are already sorted. Since these conjugates are greater than other conjugates, these are the greatest conjugates of starting with . □

Lemma 54.

for all .

Proof.

With integer , conjugates in with prefix are

With integer , these conjugates are obtained in the following cases.

- Case 1:

- concatenating of with , for all or with if ,

- Case 2:

- concatenating of with for all ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating of with ,

- Case 4:

- concatenating of with .

We consider the four cases separately. For all , the conjugate starting within (Case 1) has as prefix if or if . Also, when , the conjugate starting within (Case 2) has the prefix of . In addition, the conjugate starting within (Case 3) has as prefix . Finally, the conjugate that begins within (Case 4) has a prefix of . By construction, we can see that all the conjugates from Case 1 are sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in ; then, we have the conjugate from Case 3. Following, we have the conjugate from Case 2, sorted according to the decreasing length of the run of s following the common prefix . Finally, the conjugate of Case 4 follows. Moreover, we note that only when the run of s is exactly of length i ends the conjugate with an . Thus, only conjugates ending with an are those starting within and , i.e., those with prefixes and . □

Lemma 55.

) = .

Proof.

In , the conjugates with prefix are

Observe that the only conjugates with prefix start within , and . These conjugates have prefixes of, respectively, . One can see that these conjugates taken in this order are already sorted, and only the conjugate starting within ends with , while the other two have . □

Lemma 56.

) = .

Proof.

In , the conjugate with prefix is . The only occurrence of is within . Since the run of s is maximal, it ends with . □

Lemma 57.

.

Proof.

In , the conjugate starting with is . The only occurrence of is in , preceded by an . □

Lemma 58.

.

Proof.

In , the last conjugate is since is biggest character in . The only occurrence of is in the last character of . Hence, the last conjugate in lexicographic order starts with . Since is preceded by , the conjugate contributes a to the BWT. □

The following theorem puts the above lemmas together.

Theorem 12.

, cf. Table 15. It holds that .

Table 15.

Classification of the number of runs obtain in Theorem 12. The total number of runs is .

Proof.

Every conjugate of is smaller than any conjugate of , for all . Symmetrically, every conjugate of is greater than any conjugate of , for every . Since we considered all the disjoint ranges of conjugates of based on their common prefix, is the BBWT and BWT of .

With the structure of BWT(), we can easily derive its number of runs. The word has exactly runs: we start with 1 run from , and then concatenating each from to adds 2 runs each. By counting, we observe that , have , 4, 5 runs, respectively. The boundaries between these words do not merge. The word has exactly 8 runs. The remaining parts of the BWT have runs: we start adding 4 runs each by concatenating each to . And adds 3 runs. On the other hand, the words and do not add new runs, as they consist only of an that merges with the previous one. For the last element, adds one run. Altogether, we have , and the claim holds. □

With Lemma 37 and Theorem 12, we obtain that the additive sensitivity of for is when appending a character.

7.2.2. Substituting the Last Position of with

Here, we focus on the word that we obtain by substituting the last character of with , which is lexicographically larger than any character in . See Figure 15 for a visualization. The same as Section 7.2.1, changes to and we refer to it as below. According to its definition, = . Recall from the proof of Theorem 10 that is not a Lyndon factor. The Lyndon factors of are and . There, we prove that the run of is . We start with the first observation that is a Lyndon word.

Figure 15.

Introducing the Lyndon word studied in Section 7.2.2.

Lemma 59.

is a Lyndon word.

Proof.

The longest run of has a length of , which is a prefix of itself having prefix . Thus, is a Lyndon word. □

Thus, we prove using the as we did above.

Lemma 60.

Proof.

The first conjugate in is . The first conjugate in lexicographic order must start with the longest run of s. By the definition of , the longest run of has length , and it is obtained by concatenating the suffix of with , which is preceded by a . □

Lemma 61.

for all .

Proof.

All conjugates in starting with the prefix for any are given below.

For all , the factor can only be obtained, for all , by concatenating the suffix of , with the prefix ab of , or by concatenating suffix of with the prefix of . We can sort these conjugates according to the lexicographic order of . Note that all these conjugates end with an , with the exception of the conjugate starting with , since it is here the only occurrence of can be found. □

Lemma 62.

.

Proof.

The conjugates in starting with the prefix are

These conjugates are obtained from the following cases.

- Case 1:

- concatenating suffix of with prefix of , for all or with if ,

- Case 2:

- concatenating suffix of with prefix of for all ,

- Case 3:

- concatenating suffix of with prefix of .

All these conjugates starting with are sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in . Note that all the conjugates starting either with , for all of Case 2, or Case 3 end with . On the other hand, the conjugates starting either with of Case 2 or Case 1 end with a . □

Lemma 63.

Proof.

The conjugates in that starts with the prefix are

Each of the conjugates starting with from Lemma 62 induces a conjugate starting with , obtained by shifting one character on the left . It follows that all of these conjugates end with . The other conjugates starting with are the ones obtained by concatenating suffix of with of , and another is obtained by concatenating suffix of with of . Moreover, both conjugates end with a . We prove our claim by sorting the conjugates according to the lexicographic order of the words in . □

Lemma 64.

.

Proof.

In , the conjugates which start with prefix are

For all two distinct integers with , we have . Thus, the first conjugate in lexicographic order starting with is the one which is followed by the longest run of s. The smallest of these conjugates can be found by concatenating the suffix of with the prefix of , followed by the suffix of concatenated with the prefix of , for all all taken in decreasing order. By construction of , for all , these conjugates must end with a . The remaining conjugates starting with are exactly those conjugates having as prefix either for all and for all or and . Note that all of these conjugates are obtained by shifting one character on the left from the conjugates starting with from Lemma 63, with the exception of one starting with . It follows that the latter ends with a , while all the other conjugates end with an . □

Lemma 65.

Proof.

In , the conjugate that starts with prefix is . The lexicographic order of is larger than or , so the prefix is also larger than the prefix . is obtained from , preceded by a . □

Lemma 66.

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with the prefix are

One can notice that we have as many circular occurrences of as the number of maximal runs of s in . The conjugates are obtained from the cases below.

- Case 1:

- one run of s in , for all ,

- Case 2:

- two runs in for all ,

- Case 3:

- one run in ,

- Case 4:

- one run in .

For Case 1, we have one conjugate starting with for each . Since each run of s within each word from is of length of at least 2, all conjugates in Case 1 end with a .

For Case 2, with integer , we can distinguish between two subcases based on where starts:

- Case 2 (a):

- a first run of in , which has a prefix of for all ,

- Case 2 (b):

- a second run of in , which has a prefix of for all .

- Similarly to Case 1, all the conjugates in Case 2 (a) end with a .

- Each conjugate in Case 2 (b) is obtained by shifting two characters on the right each conjugate in Case 2 (a). Therefore, all of these conjugates end with an .

- For Case 3, the conjugate starting with in has as a prefix, and it is preceded by a .

- For Case 4, in has as a prefix, and it is preceded by a .

- Observe that only for Case 2 (b) we have conjugates starting with . Hence, the first conjugate in lexicographic order is the one starting with followed by .

- Among the remaining conjugates, those having prefix either start with from Case 2 (b) or from Case 1 for all . Thus, we can sort them according to the order of the words in . Then, the remaining conjugates with prefix are those starting with from Case 3 and from Case 2 (b).

Finally, we focus on the conjugates from Case 2 (a). These conjugates are sorted according to the length of the run of s following the common prefix . The last conjugates left are the one starting with from Case 2 (b). and the one starting with from Case 4. These conjugates are lexicographically organized and are greater than any other cases, and therefore we analyzed all conjugates. □

Lemma 67.

for all .

Proof.

In , the conjugates starting with for all are

All runs of s of length of at least are obtained from the cases below.

- Case 1:

- suffix in , for all

- Case 2:

- in for all ,

- Case 3:

- in ,

- Case 4:

- in .

- Consider the four cases separately. The conjugate starting within (Case 1) has as prefix if only or if .

- And for all , the conjugate starting within (Case 2) has as prefix .

- In addition, the conjugate starting within (Case 3) has as prefix .

- Finally, the conjugate that begins within (Case 4) has as prefix .

By construction, we have all the conjugates from Case 1 sorted according to the lexicographic order of the words in ; then, we have the conjugate from Case 3. Then, the conjugates of Case 2 are sorted according to the decreasing length of the run of s following the common prefix . Finally, the conjugate of Case 4 follows. Moreover, note that only when the run of s is exactly of length i the conjugate ends with an . Thus, only the conjugates ending with an are those starting within and , i.e., those with prefix and . □

Lemma 68.

Proof.

In , there are exactly three conjugates that start with prefix . These are

Observe that the only conjugates with prefix start within , , and . These conjugates have prefixes of, respectively, , , . One can see that these conjugates taken in this order are already sorted, and only the conjugate starting within ends with , while the other two end with . □

Lemma 69.

Proof.

In , only one conjugate starts with a prefix of and it is . The only occurrence of is within , preceded by . □

Lemma 70.

Proof.

The last conjugate in that starts with prefix is . The last conjugate in lexicographic order that starts with occurs in . Since is preceded by an , it ends with . □

The following theorem puts the above lemmas together.

Theorem 13.

, cf. Table 16. The BBWT of is BBWT() = .

Table 16.

Classification of the number of runs obtained in Theorem 13. The total number of runs is .

Proof.

Every conjugate contributing a character to is smaller than any conjugate of , for all . Symmetrically, every conjugate contributing a character to is greater than any conjugate of , for every . Since we considered all the disjoint ranges of conjugates of based on their common prefix, is the BBWT and BWT of .

With the structure of BWT(), we can easily derive its number of runs. The word has exactly runs: we start with 1 run from , and then concatenating each from to adds 2 runs each. By counting, we observe that and contribute , 4, and 4 runs, respectively. The boundaries between these words do not merge. The conjugates in and contribute with 1 and 8 runs each. The remaining parts of the BWT contribute runs: we start adding 4 runs each by concatenating each to . And adds 3 runs. and do not add new runs, as they consist only of an that merges with the previous one. The last part contributes one run. In total, we have , and the claim holds. □

8. Conclusions