Abstract

In this study, we introduced a novel graph product derived from the standard Cartesian product and investigated its structural properties, with a particular emphasis on its independence number and spectral characteristics in relation to identical neighbor structures. A key finding is that the spectrum of this newly defined product graph consists entirely of integral eigenvalues, a significant property with applications in chemistry, network theory, and combinatorial optimization. We defined vertices as the vertices having an identical set of neighbors and classified graphs containing such vertices as graphs. Furthermore, we introduced the Cartesian product for these graphs. To formally characterize the relationships between vertices, we constructed an matrix, where an entry is 1 if the corresponding pair of vertices are vertices and 0 otherwise. Utilizing this matrix, we established that the spectrum of the Cartesian product consists exclusively of integral eigenvalues. This finding enhances our understanding of graph spectra and their relation to structural properties.

Keywords:

CNS graph; DNS graph; CNS matrix; independence number; CNS spectrum; CNS energy; CNS Cartesian product of graphs MSC:

05C75; 05C69; 05C50

1. Introduction

In graph theory, two fundamental concepts that provide valuable insights into a graph’s structure are its spectrum and independence number. The spectrum of a graph, derived from the eigenvalues of its adjacency matrix, serves as a powerful tool for analyzing key properties such as connectivity, robustness, and structural patterns [1]. By capturing how vertices and edges interact through these eigenvalues, the spectrum offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the behavior of complex networks.

Another essential concept in graph theory is the independent set and the independence number, both of which have numerous applications [2]. A subset S of the vertex set of a graph G is called an independent (or stable) set if no two vertices are adjacent in G. The largest independent sets in G are referred to as -sets. The independence number, denoted as , represents the size of the largest independent set in the graph. The study of independent sets and the independence number is crucial for understanding graph properties such as sparsity, connectivity, and optimization potential in various practical applications [3]. Moreover, ref. [4] provides a relatively straightforward method to estimate upper and lower bounds for the independence number in terms of the graph spectrum.

Spectral graph theory [5] explores the relationship between graph properties and the spectrum of various graph matrices. By examining the eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix [6,7], it is possible to derive significant structural properties of the graph. For instance, the second-largest eigenvalue provides insights into the graph’s expansion and randomness properties, while the smallest eigenvalue is closely related to the independence number and chromatic number. The Cauchy eigenvalue interlacing theorem further reveals information about graph substructures, making the spectrum a useful invariant in graph analysis.

Graph theory provides a foundational framework for analyzing and understanding complex systems characterized by interconnected elements. A central concept in this framework is that of common neighbors [8], which encapsulates the immediate connections between vertices and plays a crucial role in studying structural relationships within a graph.

To lay the groundwork for our study, we build upon the concept of twin vertices [9] in a graph G. Twin vertices are pairs of vertices a and b that have exactly the same neighbors, meaning both are connected to the same set of other vertices without any differences in their connections. This concept plays a crucial role in identifying structural similarities within a graph.

In this paper, we introduce the concept of vertices, which generalizes twin vertices, and apply the equivalence relation they establish to define sets within a graph. These sets provide a deeper understanding of the graph’s structure by grouping together vertices that share similar connection patterns. This generalization enables a more comprehensive characterization of the newly defined Cartesian product.

A key approach to quantifying the relationship between neighboring vertices in a graph is through the matrix. This matrix systematically represents the identical neighbors shared among pairs of vertices, offering valuable insights into the structural patterns and connectivity dynamics within the graph.

In this study, we explored the Cartesian product, a method of combining two graphs to analyze how their neighborhood relationships interact. Our primary focus is on examining the adjacency spectrum of the resulting product graph using the matrix. Additionally, we investigate how the vertices with identical neighbors in the factor graphs influence the independence number of the product graph.

The study of the vertices in a graph and its spectral properties has significant implications across multiple domains, including structural engineering [10], deep learning [11], and optimization [12]. The cable dome structure is an advanced prestressed space system that utilizes a network of cables and compression elements to achieve high structural efficiency, expansive spans, and an aesthetically appealing design. Its importance [10] in modern architecture and engineering makes it a preferred solution for large-scale public buildings, including stadiums, exhibition halls, terminals, and transportation hubs. A key spectral property of such graphs is that the largest eigenvalue of the adjacency matrix of this graph is directly associated with maximum force transmission within the structure and determines its load-bearing efficiency and structural stability.

Deep learning models such as Transformers [11] process long-range dependencies in student performance data. Similarly, graph neural networks (GNNs) leverage spectral properties to model complex dependencies in educational and networked systems. The phenomenon of emergent abilities in GNNs, where performance dramatically improves beyond a certain scale [13], is closely tied to spectral properties. In particular, the largest eigenvalue of the adjacency matrix influences long-range learning dependencies in GNNs.

A physics-informed neural network (PINN)-based resilience framework for multi-state systems (MSS) [14] and the concept of a service function chain (SFC) [15] share graph-based modeling, stability analysis, and adaptive optimization, making them relevant across engineering, network resilience, and AI-driven forecasting. The discounted infinite horizon optimal control problem for stochastic learning networks (SLN) [12] is also deeply connected to spectral graph theory, particularly through Markov decision processes (MDPs) and value iteration.

Our objective is to understand how identical neighborhoods impact the spectrum and independence number of the Cartesian product. Understanding these properties is crucial for applications in structural engineering, deep learning, network resilience, and optimization. Through this study, we bridge graph theoretical concepts with real-world applications, enhancing our ability to design more efficient, stable, and scalable systems across multiple domains. To achieve this, we analyze undirected graphs represented by , where V is the set of vertices and E is the set of edges. A crucial metric in this investigation is the concept of graph energy, as defined in the literature [16]. This metric, denoted by , is calculated as the sum of the absolute eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix of G, providing a quantitative measure of the graph’s structural properties.

By incorporating the energy metric into our analysis, we aim to gain deeper insights into how common neighborhoods influence the organization of complex systems represented by the Cartesian product of graphs. Through the examination of the adjacency spectrum, we seek to identify significant patterns that reveal the underlying structural properties and interconnectedness within these intricate networks. Ultimately, this investigation aims to bridge theoretical concepts with practical applications, enhancing our understanding of graph dynamics and their real-world implications.

2. Preliminaries

In graph theory, the study of product graphs offers valuable insights into the structural properties and interactions of complex systems. A product graph is formed by combining two or more graphs, leading to new structures with unique characteristics. One such product is the Cartesian product, which has been extensively studied [17] for its role in various applications, including network design, computer science, and chemistry.

In this work, we introduce a new type of product graph inspired by the Cartesian product, that focuses on the concept of identical neighbors. We refer to this new construction as the Cartesian product. The idea of vertices with identical neighbors, referred to as vertices, plays a critical role in understanding relationships between vertices, as vertices with identical neighbors exhibit a high level of structural similarity within a graph. These vertices form the foundation of the newly defined product graph.

This research bridges theoretical graph concepts with practical applications, providing a framework for understanding how identical neighborhoods and the resulting spectrum can impact various fields, such as network design, protein folding, and stability analysis in complex systems. Through the concept of the Cartesian product, we aim to offer a novel perspective on graph dynamics and their underlying mathematical structures. Before proceeding further, let us discuss some fundamental terminologies:

Definition 1

([18]). Let G be a graph with vertex set V and edge set E. The neighborhood of a vertex is the set of all neighbors of v. i.e., .

Definition 2

([19,20]). The spectrum S(G) of an undirected graph G of order n is defined as the non-increasing sequence of the n real eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix of G. It has been found that certain graphs have an integral spectrum, i.e., each eigenvalue is an integer. Such graphs are called integral graphs. If are distinct eigenvalues of a graph G with corresponding multiplicities , then the spectrum of G denoted as is represented as .

Definition 3

([21]). The nullity of a graph G is the multiplicity of the eigenvalue zero in the spectrum of G.

Definition 4

([22]). If a graph has eigenvalue 0, then it is called a singular graph; otherwise, it is called a nonsingular graph.

Definition 5.

Let G be a graph with vertices. Then two vertices : are vertices if .

Definition 6

([9]). Let be a graph. Two vertices (a and b) are twin vertices in G if and only if they have the same neighborhood. In addition, if the edge belongs to E, a and b are called true twins; otherwise, they are called false twins.

Definition 7.

Let G be a graph with vertex set . The vertices with the same neighborhood are called vertices. The pair of vertices are false twins [9], and the presence of such vertices makes a graph . A graph G is said to be a graph if it contains at least one pair of vertices. A graph that is not a graph is called a graph.

Definition 8.

matrix of a finite graph G with vertex set is an matrix denoted as , defined by , where

Definition 9.

The set of all eigenvalues of the matrix of a graph G is called the spectrum of G. The sum of absolute values of these eigenvalues is called energy of the graph and is denoted as .

Also, the spectral radius is defined as the largest absolute value of the eigenvalues in the spectrum.

Definition 10.

The multiplicity of the eigenvalue 0 in the spectrum of a graph is called nullity and is denoted as .

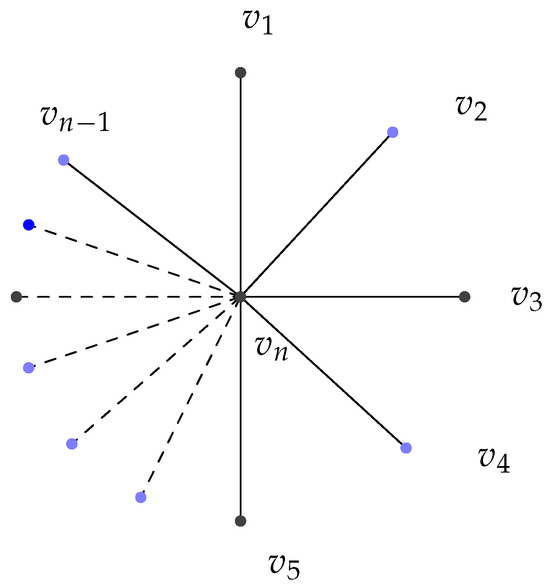

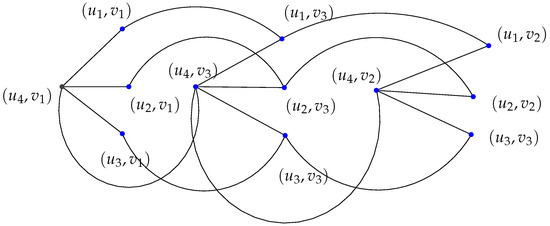

Example 1.

Consider the graph in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

.

Here, are vertices. Hence, the Star graph is a graph.

Now, matrix is , where is the matrix of order with all entries being 1.

The eigenvalues of [6] are with multiplicity and with multiplicity 1.

Hence, the spectrum of is .

So the energy, , and nullity, .

Remark 1.

The concept “Common Neighborhood” partitions the vertex set of a graph G into disjoint sets so that we can introduce the following definition.

Definition 11.

Let be a graph and be a vertex of G. Then CN set corresponding to v is denoted by or simply and is defined as .

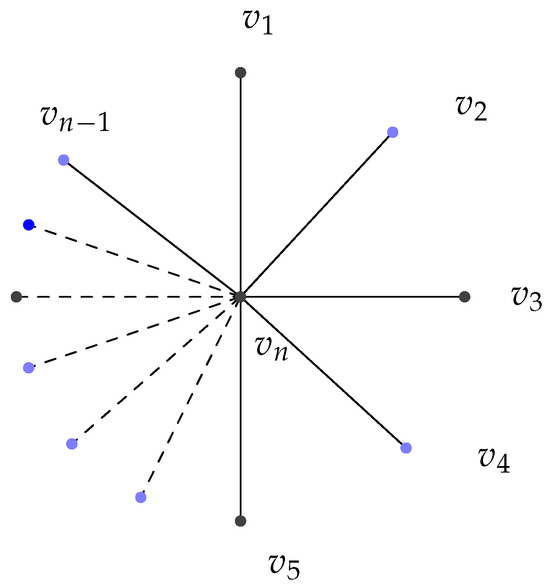

Example 2.

Consider the cycle graph shown in Figure 2, then , which is also the CN set for . Similarly, the CN set for and is . Hence, has two CN sets-

Figure 2.

.

Also, in Example 1, the CN sets are .

Definition 12.

A vertex whose CN set is a singleton is called a DN vertex. A CN set containing two elements is referred to as a Binary CN set.

In the Example 1, is a DN vertex, whereas in Example 2, the graph contains no DN vertices.

In Example 2, the sets (both have as neighbors) and (both have as neighbors) are binary CN sets.

Definition 13

([23]). Let A be an matrix and B be a matrix. The Kronecker product, denoted by , is an matrix, defined as where each entry of A is multiplied by the entire matrix B.

Theorem 1

([23]). The spectrum of the Kronecker product of two matrices A and B consists of the pairwise product of the eigenvalues of A and B.

Definition 14

([24]). If A is an matrix and B is an matrix, then the Kronecker sum of A and B is defined as: , where and are the identity matrices of order m and n, respectively, and ⊗ denotes the Kronecker product.

Theorem 2

([24]). The spectrum of the Kronecker sum of two matrices A and B consists of the pairwise sum of the eigenvalues of A and B. This means that if are the eigenvalues of A and are the eigenvalues of B, then the eigenvalues of the Kronecker sum are given by:

3. Spectrum of Graphs

In this section, we evaluated the spectrum of graphs and used this analysis to achieve our ultimate goal: determining the adjacency spectrum of the Cartesian product of two graphs.

Theorem 3.

Let G be a graph. Then spectrum of G contains only integral values.

Proof.

Consider a graph G with sets of sizes , where each . Then we can label the vertices of G in such a way that the matrix of G has a structure of block matrices with non-zero entries occurring only in k diagonal blocks and is given by . Here, denotes an all-one’s square matrix of size , while signifies the identity matrix of size .

The eigenvalues of the matrix , ref. [19] are characterized by two distinct values: with multiplicity , and with multiplicity 1. Hence, the non-zero elements in the spectrum of G are tabulated as

| Eigenvalue | −1 | −1 | …… | −1 | …… | |||

| Multiplicity | …… | 1 | 1 | …… | 1 |

Now, if the graph G has some DN vertices, then the CN set corresponding to these vertices will be singleton, and the diagonal block corresponding to the CN set will be a zero matrix of order 1; therefore, the eigenvalues corresponding to these DN vertices are 0. If G has r number of DN vertices and k number of CN sets with (where each ) elements, then the spectrum of G consists of the following eigenvalues:

- •

- 0 with multiplicity r (equal to the number of DN vertices).

- •

- −1 with multiplicity .

- •

- , each with multiplicity 1.

Also, if G has n number of vertices, then .

Hence, the spectrum of G is .

Clearly, all these values are integers. Hence, the proof is complete. □

Remark 2.

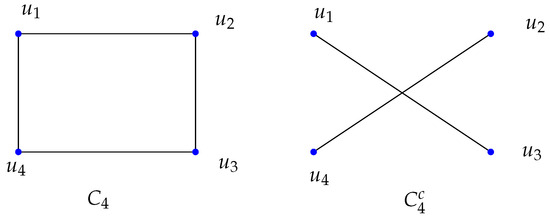

The complement of a graph is not necessarily , and the complement of a graph may indeed be . An example is given below.

Example 3.

For instance, consider Figure 3, where is a graph, but its complement shown is not.

Figure 3.

is but is not.

Theorem 4.

If a graph with n vertices has k number of CN sets with cardinality where each and r number of DN vertices, then energy of G is .

Proof.

Clearly, . Theorem 3 gives the eigenvalues and hence the energy of G

□

Theorem 5.

The nullity of a graph G is exactly the number of vertices in G.

Proof.

By Theorem 3, the multiplicity of the eigenvalue 0 is exactly the number of DN vertices for a graph. Hence the nullity is the number of DN vertices in G. □

4. Cartesian Product

The Cartesian product is a novel graph product operation that extends the traditional Cartesian product of graphs by incorporating the concept of common neighbors. The Cartesian product focuses on the common neighbors of vertices to provide a new perspective on how vertices in different graphs can be connected. In the traditional Cartesian product of two graphs, the vertices of the resulting graph are formed by combining the vertices of the original graphs, and edges are established based on the adjacency relations in the original graphs. However, the Cartesian product introduces a twist: the adjacency of vertices in the product graph is determined not only by the original graph’s adjacency relations but also by the common neighborhood structure within each graph.

Definition 15.

Let and be two graphs. Then the Cartesian product of and is denoted by and has as its vertex set. Two vertices and are adjacent if and only if

- and are vertices in .

or

- are vertices in and .

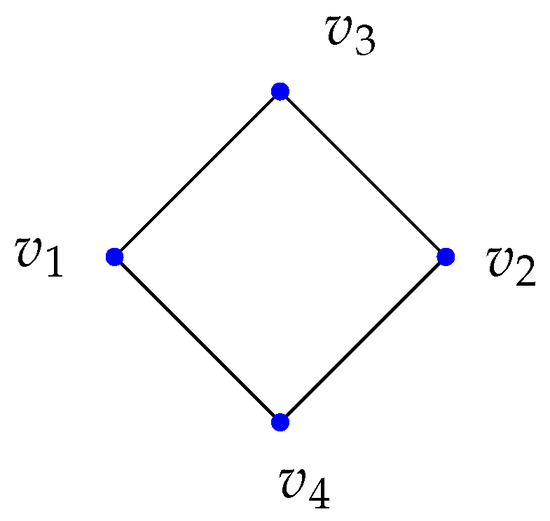

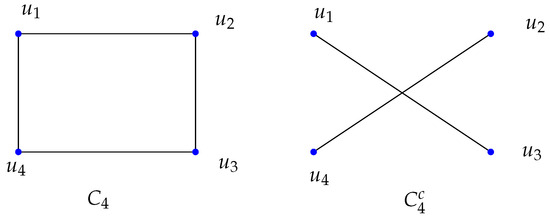

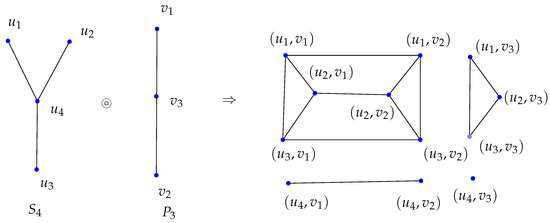

The Cartesian product of and is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

.

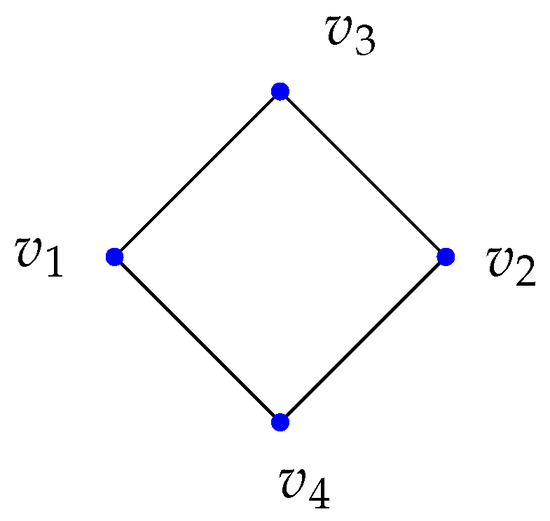

The standard Cartesian product of and is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

.

The Cartesian product focuses on pairs of veritices (false twins), making it a subset of the complement of the standard Cartesian product of the same graphs.

5. Properties of Cartesian Product

In this section, we explore and identify some fundamental properties of the Cartesian product graph that are shared with standard graph products [18]. These properties provide insights into the behavior and characteristics of the graph, contributing to a deeper understanding of its structure and potential applications.

- If are two graphs of order and respectively, then the order of is .This result follows from the fact that the vertex set of is the cross product of Here, and are of order , respectively, and hence the order of is .

- If are any two graphs, then .To explain this symmetry, let and be the vertex sets of and , respectively. Then the vertex set of is the Cartesian product, and that of is . According to the definition of Cartesian product, the connectivity between the vertices is preserved in the same manner for both and . Hence, .

- If and are any three graphs, then .To demonstrate this property, consider the vertex set of , then the vertex set for and is . According to the definition of Cartesian product, the connectivity between the vertices will be preserved in same manner for both and . Hence, .

- If are any two graphs with and vertices, respectively, then is a null graph with vertices.Given and are two graphs. Hence, it has no vertices. But two vertices and are adjacent in if and only if either or (not both) are vertices in or , respectively. Being that and are graphs, there are no such cases. Hence, has no edges and becomes a null graph.

6. More About the Cartesian Product

In this section, we examine the critical role of binary CN sets in identifying the Cartesian product as a graph. These binary CN sets are crucial for preserving the defining traits of a graph within the product structure. Furthermore, we note that the newly formed product graph also inherits binary CN sets, which significantly impact both its structure and spectral characteristics. This analysis offers valuable insights into how binary CN sets shape the overall behavior of the Cartesian product.

Theorem 6.

If and are two graphs, each having at least one binary CN set, then is also a graph.

Proof.

Let be a binary CN set of and be a binary CN set of . Then, the vertices in form a CN set because they share common neighbors, namely . Hence, is a graph. □

Theorem 7.

If and are two graphs, each having at least one binary CN set, then the Cartesian product will contain at least two binary CN sets.

Proof.

Let be a binary CN set of and be a binary CN set of . Then, the vertices and in have identical neighbors as , and the vertices and also have identical neighbors . Thus, the two binary CN sets of are and . □

Theorem 8.

Let and be two graphs with and vertices, respectively. Also, assume that the number of CN sets of and are and , respectively, with all the CN sets of and having more than one element being binary. Then energy of is . Moreover, the nullity of is .

Proof.

The matrix of is a block matrix where the diagonal blocks are given by , where is a matrix with all elements equal to 1 and is the identity matrix of order 2. The characteristic polynomial of is , and all other blocks in the matrix are zero matrices. Therefore, the spectrum of is so that the nullity of is . And energy is . □

Theorem 9.

If and are two graphs with no binary CN sets, then is a graph.

Proof.

Let be an arbitrary CN set of and let be an arbitrary CN set of . Now, consider the vertices of . Since are vertices in , the neighborhood of contains ; the neighborhood of contains for and has no self loops. Hence, no vertices in have identical neighbors. Therefore, is a graph. □

Theorem 10.

If and are two graphs, then is also a graph.

Proof.

Given that and are graphs. Therefore, and have no vertices. By definition, has no edges. Therefore, is a null graph and is a graph. □

Theorem 11.

If is a graph and is a graph, then is also a graph.

Proof.

Let be vertices of and be an arbitrary vertex of Then are adjacent in Since is a graph, there does not exists a vertex in such that and have common neighbors. Thus, we cannot make the vertices and adjacent in . Hence, the vertices and have no common neighbors. Therefore, there do not exist any vertices in . □

Theorem 12.

If is a vertex of , then neighbors of in is .

Proof.

By the definition of , two vertices and are adjacent if:

- and are vertices in , or

- are vertices in and .

Therefore, to determine the neighbors of a vertex , we need to consider:

- all vertices in the set of u in , excluding u itself, and

- all vertices in the set of v in , excluding v itself.

Thus, the neighborhood of in is given by:

.

Hence the proof is complete. □

Corollary 1.

If and are two graphs with and vertices, respectively, the number of edges in the product graph is given by

where are the collections of all CN sets of , respectively, which are not singletons, and denotes the number of vertices in each CN set .

Proof.

By the Theorem 12, the number of edges drawn from the vertex in is the total of times number of ways of selecting two elements from the CN set of v in and times the number of ways of selecting two elements from the CN set of u in

Number of edges in □

Corollary 2.

If u and v are two DN vertices of and , respectively, then is an isolated vertex in .

Proof.

Since u and v are DN vertices of and , respectively, and . By the Theorem 11, the neighborhood of in , .

Hence, is an isolated vertex in . □

Corollary 3.

The number of isolated vertices in is given by the product of number of DN vertices in and the number of DN vertices in .

Proof.

If u and v are DN vertices of and , respectively, then by the above corollary, , is an isolated vertex in . Hence, the number of isolated vertices in is the product of the number of DN vertices in and the number of DN vertices in . □

Corollary 4.

If the graphs and have and DN vertices, respectively, and contain and binary CN sets, then the components of contain path of length 2.

Proof.

Let be arbitrary DN vertices of and , respectively. Also, let be a binary CN set of and respectively. Then, in the graph , the pairs and are adjacent. Since is a binary CN set, no other edges exist between and , forming a path of length 2. Similarly, the pairs form a path of length 2. Since the graphs have DN vertices and binary CN sets, the components of consist of path of length 2. □

Theorem 13.

The Cartesian product of two arbitrary graphs will always result in a disconnected graph.

Proof.

We know that the Cartesian product of two graphs always results in a null graph and is therefore disconnected.

Next, consider the Cartesian product of a graph and a trivial graph. In this case also, the distinct CN sets of the graph corresponds to distinct components, and hence, the Cartesian product graph is disconnected. Now, consider a graph , which is a graph with CN sets , and a graph with vertex set . In the Cartesian product , vertices of the form and , where and , are adjacent if and only if and belong to the same CN set of . However, if and belong to different CN sets, the vertices and are not adjacent. As a result, there are components in , confirming that the product graph is disconnected.

Next, consider two graphs, and , with CN sets and , respectively, where at least one of the sets contains more than one element. Vertices of the form and , where and , are adjacent if and only if and belong to the same CN set of . Similarly, vertices like and are adjacent if and only if and belong to the same CN set of . Hence there are components in . Therefore, the product graph is also disconnected. □

Corollary 5.

If and are two graphs with and CN sets, respectively, then has components.

Corollary 6.

If graph has CN sets with elements, and graph has CN sets with elements, then the number of isomorphic components with elements is .

7. Independence Number of the Cartesian Product Graph

In graph theory, the independence number of a graph is a fundamental measure that captures the largest set of mutually nonadjacent vertices, known as an independent set. This number plays a critical role in understanding the structure and behavior of graphs, particularly in terms of their sparsity, connectivity, and combinatorial properties.

For the Cartesian product, understanding the independence number becomes especially important. The independent set in this graph consists of vertex pairs that are mutually nonadjacent, determined by their shared neighbor relationships within the individual graphs. Investigating the independence number of these product graphs provides important structural insights, such as the nature of disjoint components and how they interconnect.

Here, we investigate how the independence number is affected by the interplay between the CN sets of the input graphs and and how this number reflects the overall organization of the product graph. By studying the independence number in the context of the Cartesian product, we aim to deepen our understanding of the graph’s structural properties and their potential applications in various fields such as network theory, optimization, and computational biology.

Theorem 14.

Let and be two graphs with CN sets in and in . The independence number of the Cartesian product of these two graphs is given by , where denote the number of vertices in each CN set .

Proof.

Given that and are two graphs with and CN sets, respectively. We will prove that the independent set constructed in the following way for the Cartesian product is a maximum independent set. The independent set is constructed by considering the CN sets of and . If two distinct vertices in and in belong to the same CN set of and , respectively, then by the definition of the Cartesian product, the vertices and ) are nonadjacent in a component of . Since and have and CN sets, respectively, by Corollary 6, the graph has components. To construct an independent set, we take the union of nonadjacent vertices from each component.

Now, consider an arbitrary component of , formed by the CN sets from and from .

- If (say), then is the independent set for .

- If i.e., , then is the independent set for .

- If i.e., , then is the independent set for .

Since we have selected mutually nonadjacent vertices, the set formed is indeed an independent set. Furthermore, it is an independent set that contains the largest possible number of vertices. In other words, no independent set in the graph has more vertices than this one. Therefore, the maximum independent set for the component formed by contains elements.

Thus, the maximum independent set of is the disjoint union of the largest independent sets from each component of . The size of the independent set we have constructed is the largest possible, as it fully utilizes the capacity of mutually nonadjacent vertices from each component. Additionally, if we attempt to add any further vertex pairs to this set, at least one of them would be adjacent to a vertex in the constructed independent set, violating its independence. Hence, the independence number of is . □

8. Main Results on Cartesian Product

This section focuses on the primary goal of our work. We conducted a detailed analysis to identify the adjacency spectrum of the Cartesian product, which is a crucial aspect of understanding the graph’s structural properties. By examining the eigenvalues of the adjacency matrix, we were able to determine the spectrum, which reveals how the vertices of the graph are connected and how these connections influence the overall behavior of the graph.

Theorem 15.

If is a graph with vertices and is a graph with vertices, then the adjacency matrix of is given by

i.e., the Kronecker sum of and .

Proof.

Let be the vertices of and be the vertices of . The adjacency matrix of can be constructed using block matrices as given in Table 1:

Table 1.

The adjacency matrix of as block matrices.

Each block in the diagonal are determined by the CN sets of . The diagonal blocks are exactly the matrix and the non-diagonal blocks are nonzero in the place where 1 occurs in the matrix and in such blocks the diagonal elements have only entry as 1 and is determined by vertices of .

Hence, the adjacency matrix of is given by

□

Corollary 7.

The eigenvalues of is the pairwise sum of spectrum of and .

Corollary 8.

Let and be two graphs with and number of DN vertices. Also, if has CN sets of order and has CN sets of order , then

- (i)

- the nullity of is .

- (ii)

- the distinct eigenvalues of are

- (iii)

- If or or both have no DN vertices, then is non-singular.

Proof.

The eigenvalues of are given as follows:

| Eigenvalue | 0 | …… | …… | ||||||

| Multiplicity | …… | 1 | 1 | …… | 1 |

The eigenvalues of are as follows:

| Eigenvalue | 0 | …… | …… | ||||||

| Multiplicity | …… | 1 | 1 | …… | 1 |

If and have and vertices, respectively, then and . Also, the eigenvalues of are the pairwise sums of the spectra of and , resulting in the eigenvalues of , as shown in the following Table 2:

Table 2.

The eigenvalues of .

□

Theorem 16.

Let and be two graphs with and vertices, respectively, with and number of DN vertices. Also, has CN sets of order and has CN sets of order . Then, the energy of is

.

Proof.

By the above corollary, we get energy of by adding all the eigenvalues.

□

If and are two graphs, then energy of is always even.

Corollary 9.

If and are two graphs with no DN vertices, then the energy of is a multiple of 4.

9. Open Problems on the Symmetry of Cartesian Product Graphs

9.1. Open Problem 1: Characterization of Automorphism Groups of the Cartesian Product

Given the automorphism groups and , determine the structure of in the context of the Cartesian product.

- Under what conditions does decompose as a direct or semi-direct product of and ?

- What are necessary and sufficient conditions for to be isomorphic to in the Cartesian product setting?

9.2. Open Problem 2: Vertex-Transitivity of the Cartesian Product Graph

If and are vertex-transitive, does it follow that is vertex-transitive under the Cartesian product?

- Identify graph-theoretic properties of and that guarantee vertex-transitivity of .

- Are there counterexamples where both and are vertex-transitive, but is not in the Cartesian product framework?

9.3. Open Problem 3: Edge-Transitivity and Arc-Transitivity in the Cartesian Product

Under what conditions is edge-transitive or arc-transitive in the Cartesian product, given that and possess these properties?

- Develop criteria for when edge-transitivity or arc-transitivity is preserved under the Cartesian product operation.

- Investigate whether symmetry-breaking phenomena can occur, leading to cases where has fewer symmetry properties than and .

9.4. Open Problem 4: Relationship Between Symmetric Graphs and Their Cartesian Product

If and are symmetric graphs (i.e., arc-transitive and vertex-transitive), is necessarily symmetric in the Cartesian product?

- Are there additional symmetry conditions required for the Cartesian product graph to be arc-transitive?

- Can the classification of known symmetric graphs be extended to include their Cartesian product graphs?

10. Conclusions and Future Scope

In this paper, we introduced and examined the concept of the Cartesian product of graphs, with a focus on how identical neighbor structures impact both the spectrum and independence number of the graph. By analyzing the adjacency spectrum using the matrix and considering the influence of vertices with identical neighbors, we gained deeper insights into the interplay between graph structure and its spectral properties. The study further highlighted the effects of these identical neighbors on the independence number, illustrating the strong connection between spectral characteristics and the structural components of complex networks. To advance this exploration, we defined a matrix based on the neighborhood relationships of vertices within a graph. By applying the matrices of two graphs, we determined the adjacency matrix for their Cartesian product. Our analysis revealed that the Cartesian product of graphs, where vertices have identical neighborhoods comprising two elements, consistently results in integral graphs. Additionally, we observed that the energy of these graphs is always an even number. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the spectral properties of graphs generated by the Cartesian product, with potential implications for the analysis and behavior of complex networks across various domains. Study of vertices opens multiple avenues for future research. It can provide new insights into graph classification and optimization. Additionally, extending these concepts to weighted graphs and directed networks may enhance their applicability in areas like network resilience, social network analysis, and bioinformatics. The spectral characteristics of graphs can contribute to machine learning frameworks and AI-driven learning systems.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.A.B., S.K.G., E.M.E., M.K. and T.D.A.; Validation, S.K.G.; Formal analysis, S.A.B., S.K.G., E.M.E. and M.K.; Investigation, S.A.B., S.K.G., M.K. and T.D.A.; Writing—original draft, S.A.B., S.K.G., E.M.E., M.K. and T.D.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.B., S.K.G., E.M.E., M.K. and T.D.A.; Visualization, S.A.B.; Project administration, T.D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was funded by Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia under grant number: 25UQU4361068GSSR01.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4361068GSSR01.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors hereby declare that there is no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Nica, B. A brief introduction to spectral graph theory. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.08072. [Google Scholar]

- Brešar, B.; Zmazek, B. On the independence graph of a graph. Discret. Math. 2003, 272, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Shen, D. Data-driven graph construction and graph learning: A review. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. On eigenvalues and colorings of graphs. In Selected Papers of Alan J Hoffman: With Commentary; World Scientific: River Edge, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 407–419. [Google Scholar]

- Spielman, D.A. Spectral graph theory and its applications. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS’07), Providence, RI, USA, 21–23 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilf, H.S. Spectral bounds for the clique and independence numbers of graphs. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 1986, 40, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, A.E.; Haemers, W.H. Spectra of Graphs; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzeh, A.S.M.A.; Iranmanesh, A.; Hossein-Zadeh, S.; Hosseinzadeh, M.A.; Gutman, I.V.A.N. On common neighborhood graphs ii. Iran. J. Math. Chem. 2018, 9, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, R.; Noyer, C.; Raynaud, O. Twins vertices in hypergraphs. Electron. Notes Discret. Math. 2006, 27, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, S.; Li, W. Study on prestress distribution and structural performance of heptagonal six-five-strut alternated cable dome with inner hole. Structures 2024, 65, 106724. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, A.L.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L. Optimizing multi label student performance prediction with GNN-TINet: A contextual multidimensional deep learning framework. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314823. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Shen, T. A finite convergence criterion for the discounted optimal control of stochastic logical networks. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 63, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, Z.; Xin, H.; Wei, W. Scaling graph neural networks for large-scale power systems analysis: Empirical laws for emergent abilities. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 7445–7448. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Zio, E.; Yang, Z.; Xiang, Q.; Fan, L.; He, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Su, H.; Zhang, J. A systematic resilience assessment framework for multi-state systems based on physics-informed neural network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 257, 110866. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Cao, X. Provably efficient service function chain embedding and protection in edge networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2024, 33, 178–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, I. The energy of a graph. Ber. Math.-Statist. Sekt. Forsch. Graz. 1978, 103, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barik, S.; Kalita, D.; Pati, S.; Sahoo, G. Spectra of graphs resulting from various graph operations and products: A survey. Spec. Matrices 2018, 6, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Ranganathan, K. A Textbook of Graph Theory; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harary, F.; Schwenk, A.J. Which Graphs Have Integral Spectra? Graphs and Combinatorics; Bari, R., Harary, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1974; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, D.M.; Doob, M.; Sachs, H. Spectra of Graphs: Theory and Application; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 413. [Google Scholar]

- Borovicanin, B.; Gutman, I. Nullity of graphs. Zborruk Rad. 2008, 13, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, A.; Gauci, J.B.; Sciriha, I. Non-Singular graphs with a Singular Deck. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 202, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Y.; Steeb, W.H. Matrix Calculus, Kronecker Product and Tensor Product: A Practical Approach to Linear Algebra, Multilinear Algebra and Tensor Calculus with Software Implementations; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, R.A.; Johnson, C.R. Matrix Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).