Abstract

Hybrid microgrids struggle to manage electricity due to renewable source, storage, and load demand variability. This paper proposes a centralized controller employing hybrid deep learning and evolutionary optimization to overcome these issues. Solar panels, BESS, EVs, dynamic loads, steady loads, and a switching main grid make up the hybrid microgrid. To capture spatial and temporal patterns, a centralized controller uses a deep learning model with a CNN–LSTM architecture. The imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) optimizes neural network hyperparameters for more accurate controller outputs. The controller controls grid switching, voltage source converter power, and EV reference current. R2 values of 0.9602, 0.9512, and 0.9618 show reliable controller output predictions. A typical test case, low sunshine, and no EV or BESS initial charging are validation situations. Its constant power flow, uncertainty management, and adaptability make this controller better than others. Even with intermittent energy and limited storage capacity, the ICA-optimized hybrid deep learning controller stabilized smart-grids.

Keywords:

hybrid microgrid; power management; CNN–LSTM; imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA); renewable energy integration; centralized controller MSC:

68T07; 68T01; 68T05; 68T27

1. Introduction

Electrical power may be generated, stored, and distributed via a microgrid (MG). It demonstrates a revolutionary approach in the contemporary energy sector for the generation and consumption of energy. The goal of these systems is to provide a steady supply of electrical power [1,2]. The incorporation of renewable energy sources and the promotion of island mode are also aims of this approach. The use of renewable energy makes the construction of MGs more feasible. By lowering emissions of greenhouse gases, these devices also contribute to the promotion of sustainability [3,4].

It is possible for MG systems to function independently or in conjunction with the main grid, which positions them as more reliable than grid systems [5,6]. It is becoming increasingly difficult to operate the distribution grid as a result of the proliferation of photovoltaic (PV) systems, wind turbines, battery energy storage systems (BESSs), and electric vehicles (EVs). These technologies have made the traditional techniques less efficient. Considering that the rapid incorporation of distributed energy sources has resulted in the system becoming less dependable and efficient, it is therefore necessary to develop new methods of regulating and operating it. When it comes to the management and governance of energy resources, the MG is strong [7]. MGs’ transmission and distribution costs are cheaper, its carbon footprint is smaller, and its reliability is higher. Additionally, they are more effective due to the fact that they utilize real-time retail market pricing. Due to the use of renewable energy and the decentralization of power networks, the concept of the grid has undergone significant transformations. MGs generate, store, and consume energy for residential use on a relatively small scale. They play a significant role in the development of energy systems that are respectful of the environment and can adapt to changes. Prosumers, who generate and use energy, contribute to ensuring that the supply and demand in MGs are in a correct balance. Due to the presence of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power, the makeup of the energy mix is unpredictable and is constantly varying. It is necessary to have improved control mechanisms to achieve good power management. Traditional power generation has been hampered in its ability to supply electricity with the necessary amount of energy because of the ongoing energy crisis.

Renewable energy sources have been the subject of intensive study over the last few decades due to their reputation for being less harmful to the environment. Energy storage systems are integrated to reduce the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources. Moreover, further optimization of demand-side management is necessary to reduce overall energy consumption [8,9].

Renewable energy sources have considerably short operating hours. Therefore, MGs depend heavily on energy storage systems for isolated operation. Battery storage technologies help MGs to manage power generation uncertainty and increase their dependability. Additionally, BESSs are effective for cost control and volatility management [10,11]. In general, energy storage technologies provide significant opportunities for MGs to store excess energy for later utilization, leading to improved reliability [12,13]. Consequently, energy storage devices are essential to MGs since they facilitate self-sufficiency by accumulating surplus energy and utilization during peak demand.

Similarly, EVs provide sustainable mobility while also operating as energy storage units when connected to a MG [14,15]. During power shortages, EVs can take part in demand response programs and provide power [16]. EVs’ charging and discharging require effective management in order to achieve MG goals, considering EVs’ owners’ needs [17].

Distributed energy resources have complicated MGs, emphasizing the importance of power management for ensuring stability, trustworthiness, and cost-effectiveness. Even in the absence of a grid, centralized controllers regulate distributed energy resources to stabilize the system and balance supply and demand. A smart centralized power management system handles cost optimization, demand fluctuation, and intermittency, simplifying decision-making.

To address optimal power flow disturbances in DC MG systems, the author of [18] suggested a distributed control algorithm. The semi-definite relaxation method forms the basis of this algorithm. A mathematical equation was provided to demonstrate the control system’s accuracy and an IEEE-30 bus system was applied to test the proposed method. The system’s performance was verified by applying an equivalent design to several bus systems.

In order to handle real-time communication within the network, conventional algorithm-based approaches require multiple controllers. The author in [19] employed a power management method based on real-time optimal power flows for reducing the number of controllers in DC MGs. The technique was validated theoretically, and it has the capacity to make the controller appropriate for real-time optimization. Simulation outcomes verified the proposed model, which were conducted in a 30-bus DC MG system.

The author implemented a control approach using a 415V AC bus in islanded mode in [20]. Energy was supplied to the grid by a PV system and a battery storage system. This model employed voltage source converters (VSCs) linked to the batteries and the solar PV panels. The model was evaluated in different scenarios; however, the suggested approach ignored abnormal conditions in the battery state of charge or solar irradiance. Fast active power balancing was employed in [21]. In order to reach the target voltage and maintain the improved SoC, the model incorporates a buck–boost converter. The model was evaluated in one parallel and six series batteries using MATLAB.

The author of [22] studied current source inverters and their potential challenges in MGs. To control the voltage fluctuation, a front-end converter was employed. Despite the incorporation of DC–DC converters, the power system continued to exhibit inefficiencies. In order to preserve high current boosting with fewer components, a split-source current-type inverter was suggested. This approach was evaluated in different power systems. The results demonstrated that the controller effectively regulated the system’s dynamic behavior.

Controlling power systems requires a robust and rapid response controller. In order to regulate the reference voltage and current effectively, the system’s dynamic behavior must be considered for selecting a controller. In [23], a multi-stage PD controller, together with a 1 + PI controller, was employed to control DC–DC buck converters. The results indicate that the suggested method exhibited superior performance in closed-loop systems.

A particular approach for reducing power system fluctuation is the optimal power flow algorithm. In order to provide the system’s optimal power flow, the author in [24] suggested a branch power model, and this technology consistently resolved systemic issues throughout evaluation on an IEEE-14 DC bus system. However, the validation of this approach was carried out in hybrid MG systems.

Researchers in [25] developed an effective power management approach to reduce low-frequency power and current fluctuations, including centralized and decentralized controllers for current sharing. The results confirm that the system characteristics ensure optimal power flow in islanded mode. The system’s dynamic behavior was examined under several circumstances. The multi-source MG simulations confirmed the effectiveness of this approach. Fundamentally, power systems rely on inverters, which convert DC power from DC energy sources into AC. One of the most popular types of converters utilized in MG systems is the IGBT [26]. In order to identify when the IGBT switch fails and to manage the VSC, a discrete wavelet transform generator is applied in this study. However, there was limited insight into the effect of this approach on the power system.

The microgrid proposed in ref. [27] includes wind turbines, microturbines, and energy storage. This study proposes a structure for power management and employs a CNN-BLSTM deep learning model integrated with principal component analysis for wind turbine power generation forecasting. The performance of the system is evaluated by real data, but the lack of real-time energy management and the consideration of other uncertainties beyond wind turbines remain gaps. Voltage/frequency regulation is a challenge for microgrids, and the authors in ref. [28] proposed an operational structure to address it. In order to directly estimate controller coefficients from system component inputs, it employs a hierarchical deep learning recurrent convolutional neural network (HDL-RCNN). This model enables data-driven optimization of V/F regulation. The proposed technique is evaluated in the MATLAB/Simulink and compared with other approaches, such as fractional-order PID (FOPID). Improved methods for locating, categorizing, and microgrid fault detection are proposed in ref. [29]. For better high-impedance defect detection, this study combines differential protection with SVM-CNN. Multiple signal decomposition techniques, K-fold validation, and sensitivity analysis are used to assess the approach in Opal-RT. The accuracy it achieves is up to 100% and it works well.

In order to enhance energy management in the smart solar microgrid, a recent study [30] proposed an optimized CNN-LSTM model for load prediction. While a CNN may obtain key features from the input data, a LSTM provides more accurate predictions. The finding indicates that this hybrid model achieved superior results compared to single architectures such as GRU, CNN, LSTM, or Bi-LSTM. The authors in ref. [31] employed a combination of LSTM and one-dimensional CNN islanding detection in microgrids. Cost-effectiveness and lower complexity are some of advantages of 1D architectures compared to two-dimensional CNNs. The input data includes current and voltage harmonic at PCC. In order to evaluate the performance of this model, more than 4000 cases were analyzed by simulation. The results indicated that the proposed model achieved 100% accuracy in islanding detection.

Despite significant progress in microgrid research, most existing studies have relied on standard frameworks and heuristic rule-based schemes, which are unable to simultaneously address the stochastic nature of renewable generation, storage dynamics, and fluctuating loads. Although recent works have begun to apply intelligent and deep learning-based controllers, these are frequently limited by simplified architectures, manual hyperparameter selection, or validation only under restricted operating conditions and a lack of real-time performance evaluation. To bridge these gaps, the present study introduces a centralized CNN–LSTM controller optimized by ICA, which jointly captures spatial–temporal patterns and fine-tunes hyperparameters for higher accuracy. Unlike earlier works, the proposed framework is validated across diverse, challenging scenarios and evaluated under real-time operational conditions, thereby offering a more resilient and comprehensive solution for hybrid MG power management.

2. Proposed MG Model

MGs include energy sources, energy storage systems, and loads which operate on a small scale for power supply. A growing number of MGs will likely be linked to distribution networks as a result of technological advancements. Promoting the high integration of renewable energy, boosting power supply reliability, increasing efficiency, and providing islanding functionality are the primary goals of MGs. Three distinct types of MGs exist according to their technical design, which are AC, DC, or hybrid (AC/DC). Since the main power grid is AC and has well-established control and protection mechanisms, AC MGs are the preferred and most frequently utilized design. In this kind of model, a DC to AC converter is required for DC sources, energy storage systems, and DC loads. However, there are some challenges in this model, such as synchronization complexity and harmonic content. DC energy sources can connect to DC loads directly in the DC MG model. In this architecture, power converters are not required because the main bus is DC. In contrast to AC models, frequency and phase synchronization are not essential in DC MGs. Additionally, these models provide easy control and enhance the dependability of the system [32]. Considering that the main grid is AC, the AC MG architecture remains more desirable despite the advantages of DC models. Moreover, a lot of converters are needed for the individual usage of AC or DC MG models because of the integration of multiple energy sources, loads, and energy storage systems. Therefore, a hybrid AC/DC microgrid, which uses both types of networks, is the most effective solution [33]. Because of the interconnection of AC and DC models in hybrid MGs via converters and buses, these networks can make use of the best features of both types of architecture at the same time. Since there are fewer conversion steps required for the direct integration of components in hybrid models, the total cost is lowered, and efficiency is increased. Moreover, hybrid MGs provide a number of benefits, including higher transmission capacity, lower harmonic content, high power quality, and improved system dependability and stability [34].

MG Components

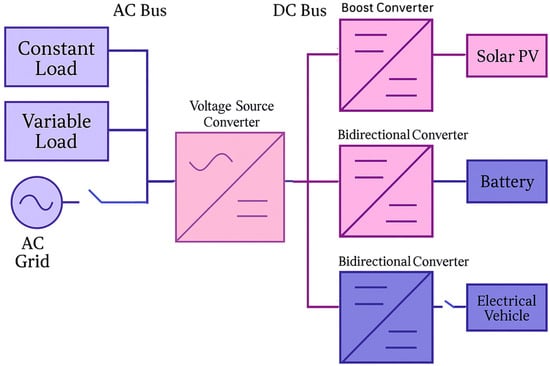

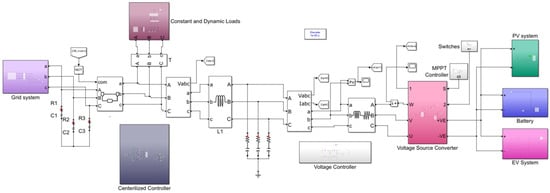

This study proposed a hybrid MG system, as shown in Figure 1. The DC components consist of PV panels, BESSs, and EVs, with the latter two serving as energy storage systems. These DC energy sources are connected to AC components, which are the main grid and loads. DC and AC buses are linked via a voltage source converter.

Figure 1.

Proposed hybrid microgrid architecture.

This model was implemented in MATLAB, which is presented in Appendix A. The system’s nominal values are shown in Table 1. The PV system is the DC energy source, which provides power to the MG in this model. The power generated by each module is represented in Equation (1), which is largely governed by solar irradiance. In this equation, P_PV, SI, and P_(PV,max) are the power output of a solar module, the current irradiance level, and maximum power of the module. The impact of temperature was ignored in this study. The total power generated by the PV system is shown in Equation (2), where the N_(parallel) and N_(series) are the number of parallel strings and the number of modules connected in series within each string, respectively. In order to increase the total power generated by the PV system, the number of panels should be expanded [35]. Table 2 presents the specifications of the PV system setup.

Table 1.

Nominal values.

Table 2.

PV system specifications.

BESSs and EVs include a lithium-ion battery. This battery has been widely used because of its effectiveness and power density [36,37]. The battery specifications are presented in Table 3. Moreover, this MG consists of a dynamic load fluctuating between 5000 W and 10,000 W, as well as a constant load of 8000 W.

Table 3.

Battery specifications.

3. Centralized Controller

3.1. ICA-Optimized CNN–LSTM Controller

In order to manage power flow efficiently in the proposed model, a centralized controller is implemented. This controller integrates a convolutional neural network (CNN) with a long short-term memory (LSTM) network. This hybrid architecture improves decision-making by combining spatial feature extraction with temporal sequence learning. The input data includes time, solar irradiation, BESS and EV states of charge (SoC), EV connection status, and load power. The major goal is to manage the grid switch, voltage source converter (VSC) power, and EV reference current in the MG. During islanded operation, VSC power is actively controlled using prediction values, leading to the control of energy flow and maintenance of the AC-DC balance. Precise prediction lowers imbalances and improves efficiency. Predicting the EV reference current aids in determining the optimal timing and amount of charge or discharge to minimize system instability. The ICA tunes CNN and LSTM hyperparameters to increase network accuracy. This optimizer was chosen for its ability to rapidly explore complicated, high-dimensional regions without being stuck in a local minimum. In contrast to gradient-based optimizers, ICA balances exploration and exploitation through a population-based evolutionary process. This makes it useful for adjusting several interdependent hyperparameters. This trait is critical in hybrid deep learning models such as CNN-LSTM, which have convolutional and recurrent components with different parameter sensitivities. The proposed controller uses ICA to stabilize parameter optimization, which makes it more accurate and generalizable than traditional methods.

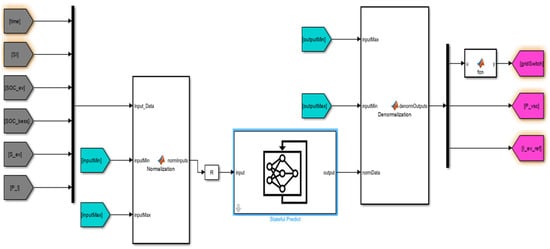

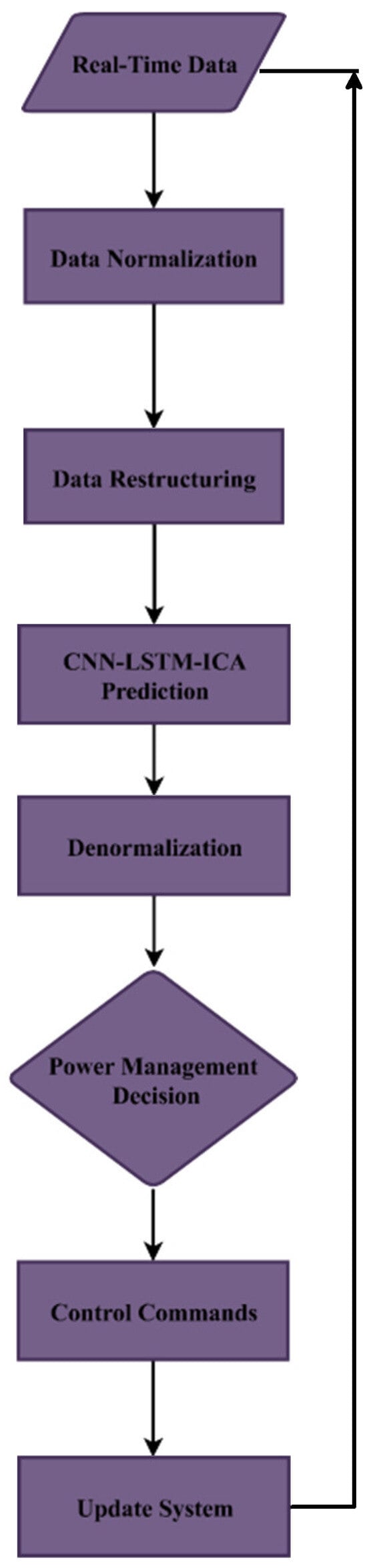

Figure 2 shows the centralized controller and its functionalities. In order to achieve feature scaling, input data and anticipated results were normalized and denormalized. The simulation lasted 2.4 s, representing 24 h. While other population-based techniques such as PSO, GA, or DE can also be used for hyperparameter optimization, ICA provides several advantages that align well with the characteristics of the CNN–LSTM architecture. The search space formed by the learning rate, dropout rate, convolutional filter size, number of filters, and LSTM units is continuous, high-dimensional, and strongly non-convex. ICA’s assimilation–revolution steps maintain diversity and prevent early stagnation, while the empire competition mechanism offers a stronger global search capability than PSO, which can prematurely converge around a single global leader. These properties make ICA more robust in navigating complex deep learning loss surfaces, enabling it to discover stable hyperparameter sets for hybrid CNN–LSTM models. This is reflected in the superior R2 values obtained by the proposed CNN–LSTM–ICA controller.

Figure 2.

ICA-optimized CNN-LSTM controller.

3.2. CNN Principles

CNNs are a type of feedforward architecture that employs convolutional transformations to systematically extract hierarchical representations and underlying relationships from time-series data [38]. The convolutional layer extracts spatial information from the input using convolutional kernels, and multiple kernels collaborate to create feature maps. The three major components of this network are the convolutional layer, the pooling layer, and the fully connected layer. The first layer is a feature extractor. It examines the input using learnable kernels that act as filters, identifying spatial patterns, as indicated in Equation (3).

In this formulation, denotes the j-th output feature map of the m-th convolutional layer, whereas indicates the i-th output feature map from the preceding (m − 1)-th layer. Mj comprises the set of input mappings utilized in the computation of . The learnable parameter specifies the weight of the convolutional kernel linking the i-th input to the j-th output. The convolution operation is denoted by ⊙. Each output map has an extra bias term . Finally, the rectified linear unit (ReLU) function, denoted as f, is employed to introduce non-linearity.

The pooling layer in CNNs compresses feature representations by down sampling the convolutional outputs and computing the average or maximum value, as illustrated in Equation (4). In this context, max(.) denotes the max-pooling subsampling operation, and represents the bias for the j-th unit in the m-th layer.

Convolutional neural networks conclude with a fully connected layer. Equation (5) illustrates the integration of high-level features from the convolutional and pooling layers to obtain the final outputs. This methodology uses as the output from the m-th CNN layer and as the input vector from the (m − 1)-th layer. The weight matrix governs interactions between layers. It maintains their learnable input–output linkages [39].

3.3. LSTM Framework

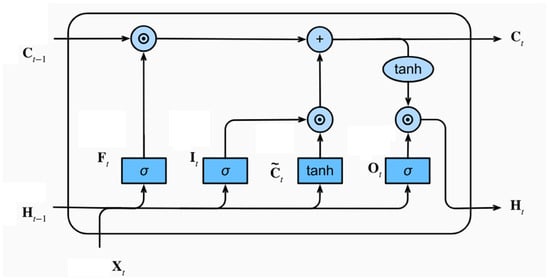

LSTM is a type of recurrent neural network (RNN). It addresses the gradient vanishing problem in RNNs with the implementation of a forget gate. It is capable of learning and recalling both short- and long-term information, rendering it advantageous for time-series data. Figure 3 illustrates the LSTM unit. Each memory cell possesses three gates: forget, input, and output. The forget gate regulates the extent to which knowledge from the previous stage may be utilized in the present. By utilizing the outputs from the preceding stage () and the inputs from the present stage (), it is possible to formulate the transfer function, as presented in Equation (6). The weight and bias coefficients are denoted as and respectively, with an activation function represented by σ(⋅).

Figure 3.

LSTM cell architecture.

The LSTM input gate, via a sigmoid function, controls how much new information is retained, as shown in Equation (7). The candidate cell state is computed in Equation (8). This term reflects the prospective information that can be incorporated at the current time step.

The cell state is updated according to Equation (9), which illustrates the integration of past information with newly generated content. The output gate is defined by Equation (10), which governs the extent to which the cell state is revealed as output at the current time step.

Finally, the hidden state is obtained as where the output gate modulates the portion of the cell state conveyed as the hidden state, described in Equation (11) [40].

3.4. Imperialist Competitive Algorithm

Imperialist competition inspired the formation of the ICA, a new multi-objective algorithm. The initial population’s elements are countries, classified as empires with the best fitness values and colonies. The fitness of the parameters is determined through competition among empires. Weak empires fall apart, while powerful ones take control of weak empires’ colonies. Eventually, the level of competition rises to the point where there is only one empire. The algorithm begins with the initialization of empires, where the countries represent candidate solutions, which are multi-variable arrays, and the aim is to optimize these variables. Equation (12) expresses the initial population and objective function. Nvar and p_iare the variable’s number and the amount of the ith variable. The objective function determines fitness, as defined in Equation (13). Countries with better fitness are selected as empires, and others are considered colonies.

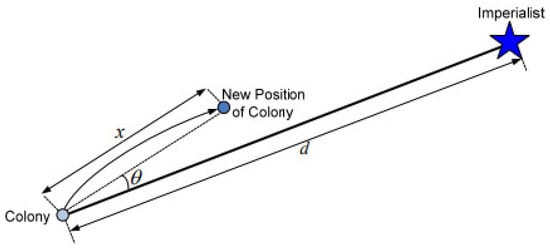

Assimilation is one of the main elements of this algorithm, performed after the segregation of colonies across imperialists. In this step, colonies move toward their related empire, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Assimilation of the Imperialist Competitive Algorithm.

The empires assimilate the colonies toward themselves based on their power, as described by Equations (14) and (15), where x, β, d, ϴ, and Υ are the colony’s movement, a constant (commonly set to 2), distance between colony and empire, deviation, and approximately π/4, respectively.

Whenever a colony gains a better position than the empire during assimilation, the positions will be exchanged between the colony and imperialist. An empire’s total power is determined by its power and its colonies.

According to Equation (16), 〖T.C〗_n is the empire’s total cost and ξ is a positive parameter (typically 0.1) that indicates the influence of the colonies. The strength of weaker empires gradually declines during imperialist competition and disappears over time. Finally, this algorithm converges into a state where only the most powerful empire remains, and it is the optimal solution of the objective function [41].

3.5. Integrated Network Configuration

The dataset used for training was obtained from the OPF algorithm presented in [42]. Each of the six inputs (time, solar irradiance, SoC of BESSs and EVs, EV switch status, and load power (constant and dynamic loads)) and three outputs (grid switch, VSC power, and EV reference current) of the controller contains 4655 samples collected at a 0.0016 s interval. The data underwent preprocessing procedures before training, including cleaning to remove illogical data, normalizing using min-max scaling to provide more stable training, and reshaping to accommodate the CNN-LSTM architecture. The dataset was divided into training, validation, and testing subsets to ensure accurate evaluation of the model.

The min-max normalization method is applied to normalize data, providing a comparable range for all parameters in order to facilitate effective network training. Equation (17) describes this approach [43], where minimum and maximum values are presented by min(x) and max(x) in the vector x.

After normalization, the data was randomly divided into three areas: training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%). Each sample might be interpreted as a one-step sequence by the CNN-LSTM architecture’s sequence input layer. Optimized values for the main learning hyperparameters were determined using the imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) illustrated in Table 4. The validation mean squared error (MSE) for each possible configuration was determined after training a temporary network. MATLAB R2024a was used in this study. The training configuration is described in Table 5 in detail. No early stopping or learning rate scheduling was utilized.

Table 4.

Optimized CNN–LSTM hyperparameters via ICA.

Table 5.

Finalized configuration.

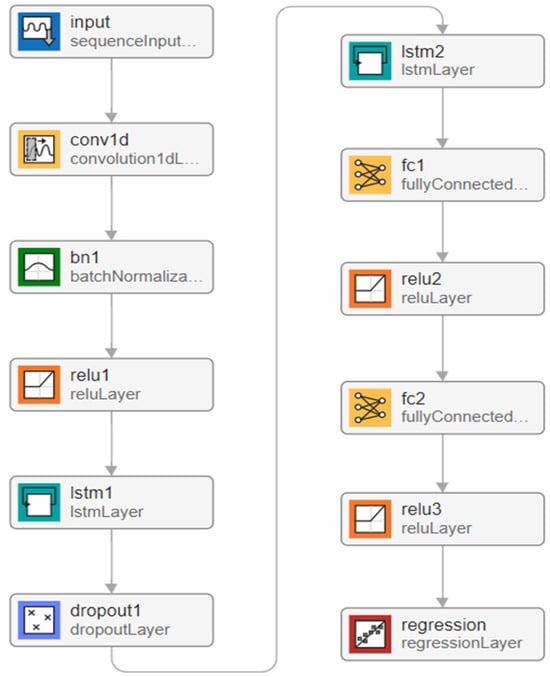

In this study, a hybrid CNN–LSTM model was employed as the centralized controller, and its hyperparameters were optimized using the ICA. The architecture begins with a sequence input layer that feeds into a 1D convolutional layer (conv1d) to extract local spatial features from the multivariate time-series signals. This is followed by a batch normalization layer (bn1) to stabilize learning and a ReLU activation layer (relu1) to introduce non-linearity. The first LSTM layer (lstm1) subsequently processes these features to capture temporal dependencies, and a dropout layer (dropout1) is applied to prevent overfitting. The output is passed to a second LSTM layer (lstm2) for deeper temporal feature learning, followed by two fully connected layers (fc1, fc2) interleaved with ReLU activations (relu2, relu3) to model complex non-linear mappings. Finally, a regression layer produces the network’s output for continuous prediction tasks. Figure 5 illustrates the layer structure of the proposed model.

Figure 5.

Layer structure.

The optimization process focused on the main learning parameters, including the number of LSTM units, learning rate, dropout rate, mini-batch size, as well as the convolutional filter size and number of filters, which were considered as candidate solutions (countries). These solutions were repeatedly refined by the ICA through assimilation and revolution processes, modeled as competition among empires, in order to achieve more optimal parameters. The fitness of each configuration was evaluated using the validation loss, measured by the mean squared error (MSE) [44], as presented in Equation (18), where Y_i, X_i, and m are the predicted validation output from the trained CNN–LSTM, actual validation output, and number of samples in the validation set, respectively.

3.6. Assessment Measure

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed centralized controller, the performance of three successive model developments was assessed: CNN, CNN–LSTM, and CNN–LSTM optimized with ICA. One of the evaluation metrics employed was the coefficient of determination (R2), which quantifies the goodness of fit between the actual and forecasted outputs of the MG system. The controller had three outputs; therefore, R2 values were computed individually for each output across all models to guarantee uniformity. R2 is an appropriate metric as it assesses the precision of the predicted values in relation to actual trends, irrespective of output magnitude. Error-based metrics such as RMSE or MAE reflect discrepancies, and R2 provides a reliable comparison of the controller’s three outputs. Equation (19) shows the formulation of R2, which was employed to quantitatively evaluate the forecasting accuracy [45], where Yk and are the actual and predicted values. is the mean of the actual N values.

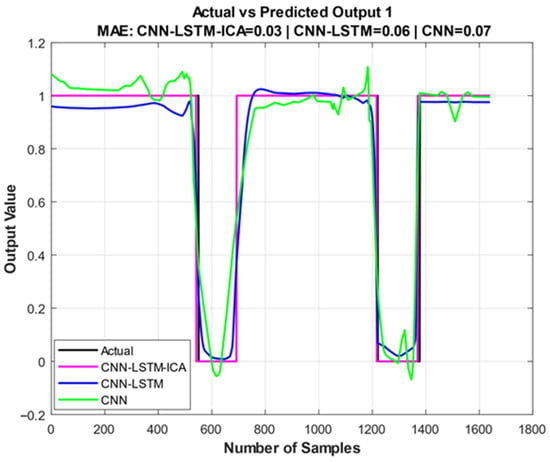

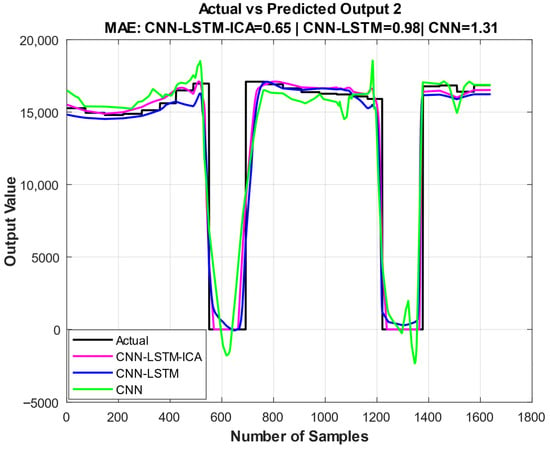

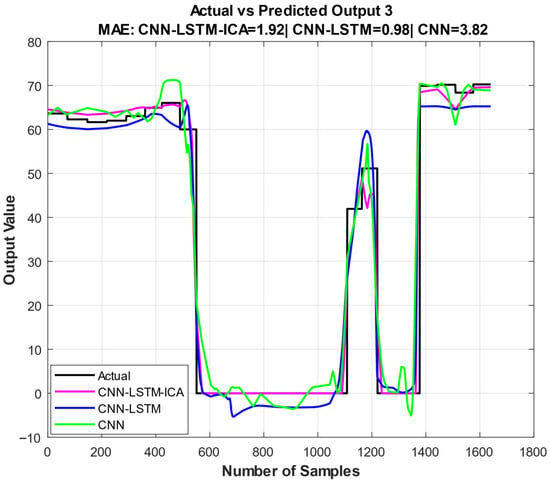

Table 6 presents the evaluation metrics of the three models for the controller outputs, where R2 ranges from 0 to 1 and values closer to 1 indicate higher prediction accuracy. As shown, the CNN–LSTM–ICA model achieves the highest R2 values across all outputs, confirming its superiority over the baseline CNN and CNN–LSTM models. Furthermore, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the actual and anticipated values for outputs 1–3 compared to each other, and clearly demonstrate the progressive improvement of the proposed model.

Table 6.

Evaluation metrics of the three models for the controller outputs.

Figure 6.

Actual data versus models’ predictions (Output 1).

Figure 7.

Actual data versus models’ predictions (Output 2).

Figure 8.

Actual data versus models’ predictions (Output 3).

3.7. Power Management

The trained CNN-LSTM-ICA model was employed as a centralized controller in the MG, predicting and regulating critical elements such as the operational state of the main grid switch, the VSC’s supplied power, and the EV’s reference current to achieve optimal power management. It governs the output power of the VSC, the charging and discharging current of the EV, and the connection to the utility grid.

Simulink’s local control loop converts expected outputs into real-time control actions for the controller. A simulated three-phase breaker regulates the primary grid connection of the MG, with the anticipated grid switch status directing its functionality. A PI controller modifies the VSC modulation index according to forecasted power to deliver exact power output. The existing control loop obtains the reference current from a buck–boost converter to facilitate the charging and discharging of the electric vehicle battery. The accuracy of the CNN-LSTM-ICA model’s predictions in real-time operation is ensured by these control loops.

A decision logic unit ultimately optimizes the power flow according to these forecasts. To maintain system stability, the main grid switch is turned on when a power deficiency is detected. While the EV reference current regulates the bidirectional flow with the EV battery, the VSC reference power determines how much energy is converted to maintain power balance between the AC and DC interfaces. The controller continuously improves its predictions and decision-making through a monitoring loop, where control signals are sent to the microgrid components and real-time data is fed back into the model. Improved microgrid resilience, optimized energy consumption, and cost-effectiveness are all outcomes of this adaptive control strategy, and the flowchart is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Centralized controller flowchart.

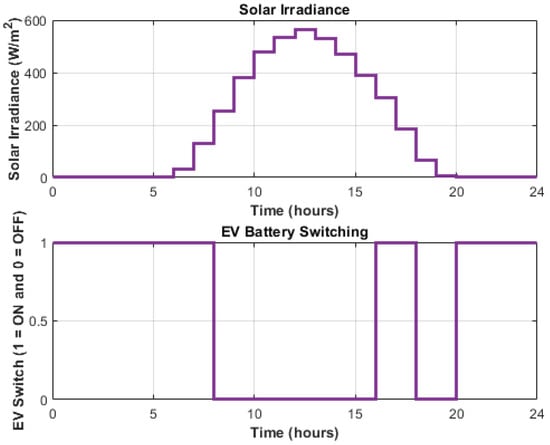

4. MG Mode Functionalities

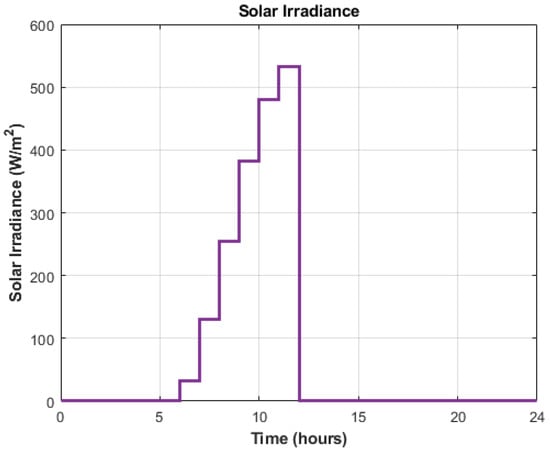

In the proposed MG, several interconnected elements operate together to ensure reliable power management. The total load is composed of both constant and dynamic parts, with the latter varying throughout the day. Solar panels provide electricity during daylight hours to meet this requirement. To ensure voltage and power regulation, the photovoltaic units are deactivated in grid-connected mode and electricity is supplied only by the main grid. The BESS is essential for stability. It releases energy while the MG is functioning independently. When the MG is linked to the grid, the BESS recharges from the photovoltaic system but does not produce power. The EV charges and discharges similarly to the BESS, except when it is intentionally disconnected. Figure 10 illustrates the solar radiation and the EV connection status. This figure exhibits a staircase structure due to the hourly data collection. The MG can be connected to the main grid by the grid switch. The switch is typically open to allow local resources such as the PV system, BESS, and EV to supply the MG’s demand; it closes when the MG output power is inadequate.

Figure 10.

Solar irradiation and EV connection status.

In islanded mode, the MG relies solely on local sources to supply demand. The generated power is defined in Equation (20).

denotes the power of the PV system while and represent the powers of the BESS and EV, respectively. and indicate the states of charge of the BESS and EV. The BESS and EV can only produce electricity when their states of charge exceed zero. Positive values indicate charging by the PV system, whilst negative values signify discharging for providing power to the loads. This bidirectional method enables energy storage and utilization as required, enhancing energy management. Equation (21) expresses the total load demand.

The dynamic load is represented by , the constant load by , and the losses associated with the VSC are denoted by . The power balance is presented in Equation (22).

The MG can operate independently via the PV system. The BESS and EV discharge to supply the load, as long as ≥ 0. If is less than 0, local generation cannot meet the load. The main grid makes up the gap, and the PV system charges the BESS and EV. The EV does not actively exchange power when disconnected, operating only through the reference signal provided by the controller.

The CNN-LSTM-ICA controller forecasts the grid switch status, VSC power, and EV reference current to manage these dynamics. The switching logic enables the system to transition seamlessly between the isolated and grid-connected modes. The controller activates the switch when net power is negative. The connection to the primary grid prevents the DC sources from supplying power to the load. The switch is deactivated when net power is zero or positive, as shown in Equation (23).

VSC power is forecasted to regulate flow and balance the AC/DC sides in islanded mode, where accurate prediction prevents imbalances and enhances efficiency. In grid-connected mode, it remains zero, as expressed in Equation (24).

Predicting the EV reference current is essential for deciding charge–discharge timing and magnitude, thereby avoiding instability. It is illustrated in Equation (25).

is determined by the following two equations for the respective operating modes.

Grid-connected operation:

Isolated operation:

5. Simulation Outcomes

MATLAB/Simulink was employed to model and evaluate the MG controlled by the CNN–LSTM–ICA centralized controller. The performance of the proposed controller was analyzed under three operating scenarios: (1) normal operating condition, (2) solar irradiance drop scenario, and (3) BESS and EV with 0% initial SoC. The controller outputs and the power of the MG components are illustrated for each case in this section. In addition, the grid system voltage, DC bus voltage, and VSC current are presented. Subsequently, this section provides the results and analysis for each operating scenario.

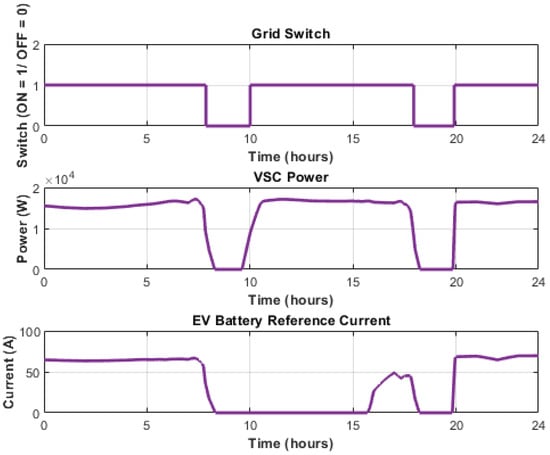

5.1. Normal Operating Condition

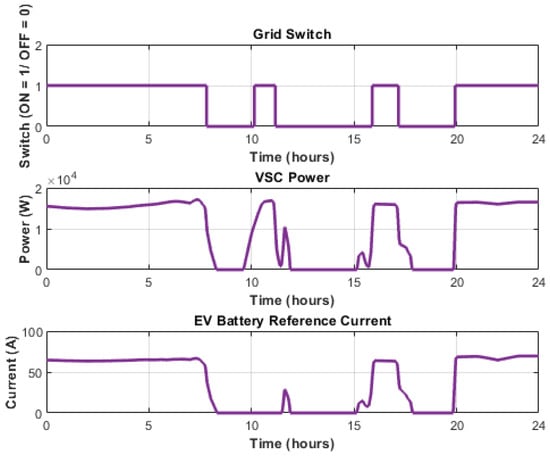

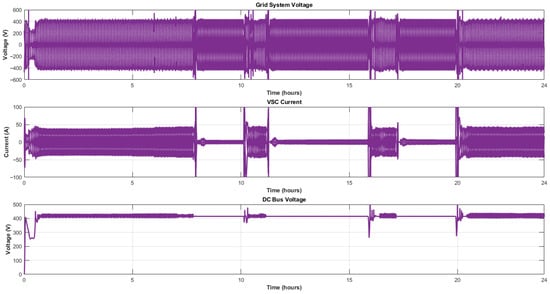

In the first scenario, the grid switch takes the value of 1 in three-time intervals, representing the isolated mode of operation, while it is 0 in the remaining periods, indicating grid-connected operation. When the grid switch is not connected, the VSC provides power. The reference current of the EV battery remains active during isolated periods to sustain the system and diminishes to zero when the main grid supplies the microgrid or when the EV is not connected to the MG. These variations demonstrate the influence of operational mode on power distribution and battery usage. The controller outputs for this condition are depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Centralized controller outputs (normal operating condition).

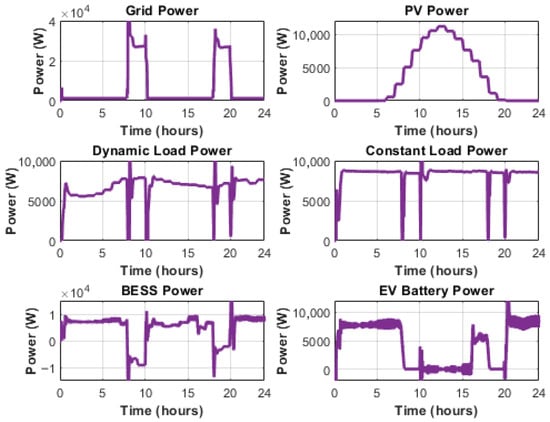

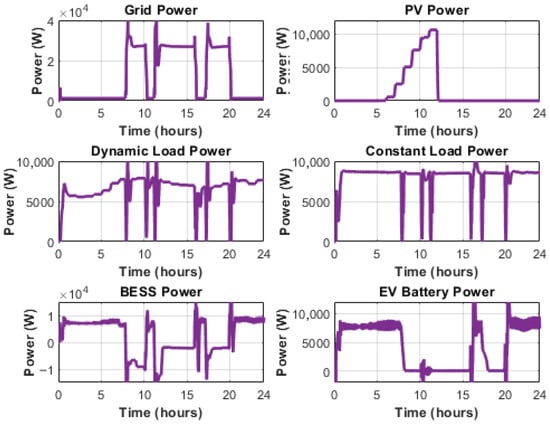

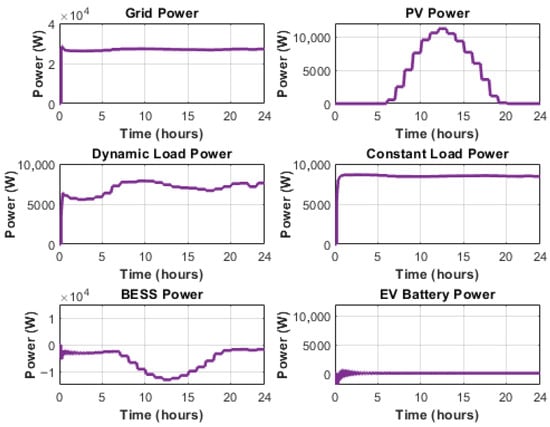

The MG parts’ power variations over 24 h are illustrated in Figure 12. The grid power is drawn only when the MG is in grid-connected mode; otherwise, it is zero. The PV system generates power based on the solar profile, with the greatest around noon and none at night. Dynamic load demand is continuous and variable. The BESS charges and discharges based on power balance. EVs charge from the PV system when the grid is connected to the MG, otherwise it provides power.

Figure 12.

Power of MG components (normal operating condition).

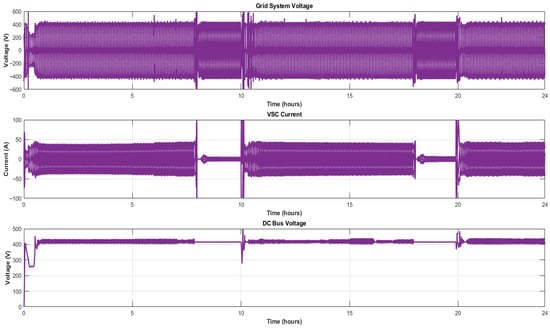

The grid system voltage, VSC current, and DC bus voltage are shown in Figure 13. The grid system’s voltage is around 400 V; however, it experiences minor fluctuations during the transition between operational modes. The VSC current varies with the switching mode. It provides energy in the isolated mode but diminishes to nearly zero in grid-connected mode, according to the controller. The DC bus voltage remains at around 400 V throughout the day, demonstrating minor fluctuations during transition modes. Activating and deactivating the switch induces transient voltage fluctuations that promptly stabilize. These results demonstrate that the proposed control system maintains stable bus voltage and VSC performance under grid fluctuations

Figure 13.

Performance of grid voltage, VSC current, and DC bus voltage (normal operating condition).

5.2. Solar Irradiance Drop Scenario

The sunlight availability influences whether the grid switch will be on or off. In this scenario, radiation from the sun begins to rise in the morning, reaching its peak right before noon, and then drops to zero. This leads to a considerable drop in the amount of electricity generated by solar cells. As a result, the amount of electricity produced by the PV system declines, forcing the MG to rely more and more on the main grid to meet its needs. VSC power increases while the system is disconnected from the grid and reduces when the system is in connected mode. According to the EV reference current, the EV battery supports the system in some isolated intervals but remains inactive in others, depending on connection status and demand balance. Figure 14 and Figure 15 depict both the solar irradiance profile and the controller’s outputs.

Figure 14.

Atypical SI.

Figure 15.

Centralized controller outputs (solar irradiance drop scenario).

According to Figure 16, the PV output drops abruptly at midday, creating a sudden power imbalance. The grid, BESS, and EV battery powers respond accordingly: the grid supports during connected periods, while in isolated intervals, the BESS and EV supply power to stabilize the system. The BESS alternates between charging and discharging, and the EV contributes selectively based on availability, while the dynamic load varies throughout the day.

Figure 16.

Power of MG components (solar irradiance drop scenario).

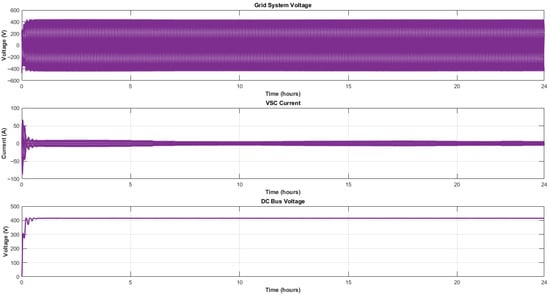

The grid voltage exhibits stable operation but undergoes brief oscillations during mode transitions. The VSC current shows active contribution when the system operates in isolated mode, and at other times it is minimal. The DC bus voltage maintains stability at around 400 V, with short-lived deviations at switching points, as shown in Figure 17. These patterns demonstrate the controller’s adaptability in managing voltage and current dynamics under changing grid conditions.

Figure 17.

Performance of grid voltage, VSC current, and DC bus voltage (solar irradiance drop scenario).

5.3. BESS and EV with 0% Initial SoC

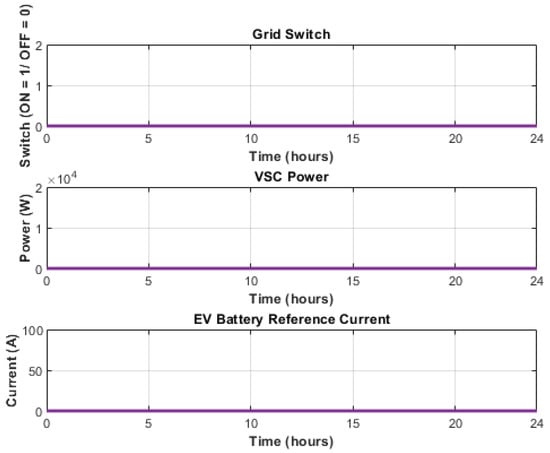

In the third situation, when the BESS and EV start with 0% charge, the MG relies on the main grid to satisfy all of its demand throughout the 24 h period, as shown in Figure 18. The grid switch remains at 0, which means that the MG is connected to the main grid. Since the VSC power and EV battery reference current are not used, they remain inactive.

Figure 18.

Centralized controller outputs (BESS and EV with 0% initial SoC).

Figure 19 shows that the main grid satisfies demand completely during the day. In this scenario, the PV system does not contribute to the power supply. There is no fluctuation in constant or dynamic loads because there is no mode transition. Both the BESS and EV start at 0% SoC and neither can provide positive power. For steady and flexible power distribution, the initial SoC must be above a specific threshold. As there is no switching or mode change, the voltage and current remain constant during operation without ripple or fluctuation, as shown in Figure 20.

Figure 19.

Power of MG components (BESS and EV with 0% initial SoC).

Figure 20.

Performance of grid voltage, VSC current, and DC bus voltage (BESS and EV with 0% initial SoC).

For achieving stable performance in multi-output microgrid management, ICA is superior to PSO and GA because it explores higher-dimensional search spaces more effectively, avoids premature convergence, and converges on near-globally optimum hyperparameters more rapidly. LSTMs excel at discovering the long-term temporal dependencies related to renewable fluctuations, battery dynamics, and load variations, and CNNs excel at discovering spatial correlations in multi-sensor microgrid data. Therefore, we chose the CNN-LSTM architecture instead of standalone CNNs, LSTMs, or transformer-based structures. Predictions are made more accurate and resilient in the face of uncertainty by this structure.

This work focused on a microgrid utilizing a single type of renewable energy, which limits the generalizability of the proposed controller to more diverse or larger systems. Future research will evaluate the controller’s performance in different operational contexts and in larger microgrids. Expanding the approach to include multiple renewable energy sources, testing with additional datasets, and exploring a dual-strategy optimization framework will enhance the flexibility, robustness, and cost-effectiveness of the system.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a centralized controller based on CNN-LSTM, optimized with the imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA), to enhance power management in a hybrid microgrid comprising photovoltaic panels, a BESS and EV, dynamic loads, and constant loads interfaced with the main grid via a switching mechanism. The controller regulates the primary grid switch, voltage source converter power, and EV reference current using spatial and temporal learning. Utilizing ICA for hyperparameter optimization yielded highly accurate results for the model. The R2 values for grid switch status, VSC power, and EV reference current were 0.9602, 0.9512, and 0.9618, respectively.

The recommended controller was tested in three scenarios: ordinary operation, low solar irradiation, and a BESS and EV without an initial charge. The system maintained electricity flows in all conditions, decreasing fluctuations and ensuring reliability. The simulation results demonstrated that the ICA-optimized CNN–LSTM controller exhibits better performance than normal controllers, especially when coping with renewable energy availability and storage system limits. This research suggests using evolutionary algorithm-tuned deep learning controllers to improve microgrid adaptability, accuracy, and robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and A.U.; methodology, P.B. and A.U.; software, P.B. and A.U.; validation, P.B. and A.U.; formal analysis, A.U.; investigation, P.B. and A.U.; resources, P.B. and A.U.; data curation, P.B. and A.U.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B. and A.U.; writing—review and editing, P.B. and A.U.; visualization: P.B. and A.U.; supervision, A.U.; project administration, A.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the Institute of Graduate Studies in Istanbul, Aydın University, for its support and collaboration throughout this study, which is much appreciated. This work was completed thanks to its academic and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1 presents the proposed model simulation.

Figure A1.

Simulation of the proposed model.

References

- Dinata, N.F.P.; Ramli, M.A.M.; Jambak, M.I.; Sidik, M.A.B.; Alqahtani, M.M. Designing an optimal microgrid control system using deep reinforcement learning: A systematic review. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 51, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agupugo, C.P.; Tochukwu, M.F.C.; Ogunmoye, K.A.; Mosha, A.S.; Sabbih, F. Review of Smart Microgrid Platform Integrating AI and Deep Reinforcement Learning for Sustainable Energy Management. Int. J. Future Eng. Innov. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Dong, W.; Lv, Z.; Gu, Y.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P. Hybrid microgrid many-objective sizing optimization with fuzzy decision. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 2702–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Hu, J.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ghosh, B.K. A distributed economic dispatch strategy for power–water networks. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2021, 9, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Cai, Y.; Li, X. Process arrangement and multi-aspect study of a novel environmentally-friendly multigeneration plant relying on a geothermal-based plant combined with the goswami cycle booted by kalina and desalination cycles. Energy 2024, 299, 131381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, M.A.; Nallathambi, K.; Vishnuram, P.; Rathore, R.S.; Bajaj, M.; Rida, I.; Alkhayyat, A. A novel technological review on fast charging infrastructure for electrical vehicles: Challenges, solutions, and future research directions. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 82, 260–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lund, P.D. Peer-to-peer energy sharing and trading of renewable energy in smart communities─trading pricing models, decision-making and agent-based collaboration. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadega, P.A.; Sun, Y.; Akindeji, K.T. A modified droop control technique for accurate power-sharing of a resilient stand-alone micro-grid. In Proceedings of the 2023 31st Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference (SAUPEC), Johannesburg, South Africa, 24–26 January 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Thirumalai, M.; Hariharan, R.; Yuvaraj, T.; Prabaharan, N. Optimizing distribution system resilience in extreme weather using prosumer-centric microgrids with integrated distributed energy resources and battery electric vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Haider, Z.M.; Malik, F.H.; Almasoudi, F.M.; Alatawi, K.S.S.; Bhutta, M.S. A comprehensive review of microgrid energy management strategies considering electric vehicles, energy storage systems, and AI techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari-Heris, M.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Razzaghi, R. A bi-level framework for optimal energy management of electrical energy storage units in power systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 216141–216150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, J. An initialization-free distributed algorithm for dynamic economic dispatch problems in microgrid: Modeling, optimization and analysis. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 34, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.A.; Jyothi, B.; Rathore, R.S.; Singh, A.R.; Kumar, B.H.; Bajaj, M. A novel framework for enhancing the power quality of electrical vehicle battery charging based on a modified Ferdowsi Converter. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2394–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yanrong, C.; Hai, T.; Ren, G.; Wenhuan, W. DGNet: An adaptive lightweight defect detection model for new energy vehicle battery current collector. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 29815–29830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaroual, M.; Hermann, D.T.; Ouassaid, M.; Bajaj, M.; Maaroufi, M.; Alsaif, F.; Alsulamy, S. Optimal solution of peer-to-peer and peer-to-grid trading strategy sharing between prosumers with grid-connected photovoltaic/wind turbine/battery storage systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 6747936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Varghese, G.T.; Mohanty, S.; Kolluru, V.R.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L.; Misak, S. Energy management and power quality improvement of microgrid system through modified water wave optimization. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6020–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Mohammed, A.N.; Mishra, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Selim, A.; Bajaj, M.; Rihan, M.; Kamel, S. Optimal real-time tuning of autonomous distributed power systems using modern techniques. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1055845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbabak, H.; Alsafasfeh, Q.; Su, W. A distributed consensus-based algorithm for optimal power flow in DC distribution grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, H. Distributed Real-time Optimal Power Flow Strategy for DC Microgrid Under Stochastic Communication Networks. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 11, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Narayanan, V.; Singh, B.; Panigrahi, B.K. Multiple voltage source converters based microgrid with solar photovoltaic array and battery storage. E-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 7, 100408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, G. An efficient buck-boost converter for fast active balancing of lithium-ion battery packs in electric vehicle applications. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109429. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Moneim, M.G.; Hamad, M.S.; Abdel-Khalik, A.S.; Hamdy, R.R.; Hamdan, E.; Ahmed, S. Analysis and control of split-source current-type inverter for grid-connected applications. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 96, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Rahnama, A.; Takorabet, N.; Thounthong, P.; Bizon, N. Designing a multi-stage PD (1 + PI) controller for DC–DC buck converter. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Nasir, M.; Schulz, N.N. An optimal neighborhood energy sharing scheme applied to islanded DC microgrids for cooperative rural electrification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 116956–116966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheradmandi, M.; Hamzeh, M.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. A hybrid power sharing control to enhance the small signal stability in DC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 1826–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Das, A.; Medikondu, N.R.; Almawgani, A.H.; Alhawari, A.R.; Das, S. Wavelet-based rapid identification of IGBT switch breakdown in voltage source converter. Microelectron. Reliab. 2024, 152, 115283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Jokar, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Kavousi Fard, A.; Dabbaghjamanesh, M.; Karimi, M. A Deep Learning-to-learning Based Control system for renewable microgrids. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2025, 19, e12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, N.; Dowlatabadi, M.; Sabzevari, K. A hierarchical deep learning approach to optimizing voltage and frequency control in networked microgrid systems. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Cano, A.; Benavides, D.; Jurado, F. Fault analysis in clustered microgrids utilizing SVM-CNN and differential protection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 112031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, T.N.; Cho, M.Y.; Thanh, P.N. Hourly load prediction based feature selection scheme and hybrid CNN-LSTM method for building’s smart solar microgrid. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcanli, A.K.; Baysal, M. Islanding detection in microgrid using deep learning based on 1D CNN and CNN-LSTM networks. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 32, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismail, F.S. A critical review on DC microgrids voltage control and power management. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30345–30361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Sattar, H.; Hassan, M.H.; Vera, D.; Jurado, F.; Kamel, S. Maximizing hybrid microgrid system performance: A comparative analysis and optimization using a gradient pelican algorithm. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.R.; Sarker, S.; Halim, M.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Haque, A. A Comprehensive Review of Techno-Economic Perspective of AC/DC Hybrid Microgrid. Control Syst. Optim. Lett. 2024, 2, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnayak, S.K.; Choudhury, S.; Nayak, N.; Bagarty, D.P.; Biswabandhya, M. Maximum power tracking & harmonic reduction on grid PV system using chaotic gravitational search algorithm based MPPT controller. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Smart Power System and Sustainable Energy (CISPSSE), Keonjhar, India, 29–31 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Phogat, P.; Dey, S.; Wan, M. Powering the sustainable future: A review of emerging battery technologies and their environmental impact. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 3266–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzen, J.; Lakshmipathy, S.; Kapahi, A.; Kraft, S.; DiDomizio, M. Lithium ion battery energy storage systems (BESS) hazards. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 81, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Coimbra, C.F. Hybrid solar irradiance nowcasting and forecasting with the SCOPE method and convolutional neural networks. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, T.; Wang, H.; Tahir, M.; Zhang, Y. Wind and solar power forecasting based on hybrid CNN-ABiLSTM, CNN-transformer-MLP models. Renew. Energy 2025, 239, 122055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Peng, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, W. Dynamic fusion LSTM-Transformer for prediction in energy harvesting from human motions. Energy 2025, 327, 136192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.C.; Prusty, U.C.; Prusty, R.C.; Panda, S. Imperialist competitive algorithm optimized cascade controller for load frequency control of multi-microgrid system. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2025, 47, 5538–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khujaev, A.; Uğurenver, A. Centralized controller-based on optimal power flow (OPF) algorithm for power management in microgrid systems. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2025, 43, 2279–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao-Van, K.; Minh, T.C.; Tan, H.M. Prediction of heart failure using voting ensemble learning models and novel data normalization techniques. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 110888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghojoghi, E.; Farsangi, M.A.E.; Mansouri, H.; Rashedi, E. Prediction and minimization of blasting flyrock distance, using deep neural networks and gravitational search algorithm, JAYA, and multi-verse optimization algorithms. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, A.; Kissaoui, M.; Bahatti, L.; Raihani, A.; Errakkas, K.; Atifi, Y. Efficient Day-Ahead Energy Forecasting for Microgrids Using LSTM Optimized by Grey Wolf Algorithm. E-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 13, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).