1. Introduction

The direct detection of gravitational waves (GWs) from the binary black hole merger GW150914 by the Advanced LIGO detectors [

1] marked the beginning of gravitational wave astronomy. This observation confirmed a key prediction of Einstein’s general relativity and opened a new way to study the universe through gravitational signals. In the subsequent years, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) collaboration has reported over 90 confident detections [

2], with the ongoing fourth observing run (O4) detecting events at unprecedented rates approaching one per week [

3].

The scientific value of gravitational wave observations depends heavily on accurately determining the properties of their sources. Parameter estimation (PE) in gravitational wave astronomy involves inferring the intrinsic properties (masses, spins) and extrinsic properties (distance, sky location, orientation) of the source from noisy detector data. Solving this problem is computationally demanding. The parameter space is large, often involving 15 or more continuous dimensions. The likelihood function exhibits complex multi-modal structure with strong parameter correlations. The need for Bayesian inference requires extensive sampling of the posterior distribution [

4].

Traditional methods for Bayesian parameter [

5] estimation rely on stochastic sampling algorithms. Examples include LALInference [

4] and Bilby [

6]. These tools use techniques like nested sampling [

7] or ensemble Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) [

8]. While these methods are theoretically well-founded and have been extensively validated, they face growing computational challenges. A single parameter estimation run usually requires between

and

likelihood evaluations. This can take hours or even days, even when using powerful computing clusters [

9]. This computational burden impacts not only catalog production but also real-time applications crucial for multi-messenger astronomy [

10].

The high computational cost of traditional methods has driven interest in machine learning for gravitational wave parameter estimation. These new approaches use neural networks and modern automatic differentiation tools to speed up inference, with efficient computation frameworks to reduce analysis time. Recent work includes several different techniques: simulation-based inference using neural posterior estimation [

11], variational inference with normalizing flows [

12], and likelihood-free inference methods [

13]. Among these, the JimGW (Just-in-time Gravitational Wave) framework [

14] combines normalizing flows with JAX’s automatic differentiation. This allows fast, GPU-accelerated parameter estimation.

However, current machine learning methods for gravitational wave parameter estimation have a key weakness. They mainly use first-order gradient information to optimize the likelihood function. This becomes a serious issue for gravitational wave signals. The relationship between the signal and the source parameters is highly nonlinear. This leads to strong curvature in the likelihood surface. Parameter estimation is further complicated by degeneracies, such as the link between distance and inclination. The way detector networks respond to different wave polarizations also adds complexity.

In this work, we introduce a new method for estimating gravitational wave parameters. This approach uses a second-order likelihood optimization framework built into the JimGW machine learning system. Current methods often rely on first-order approximations, which can miss important details, while our method incorporates the full Hessian matrix of the likelihood function. This allows us to better capture the shape of the parameter space for gravitational waves. Our theoretical framework demonstrates that the trace of the Hessian matrix [

15,

16,

17], when properly normalized, provides a coordinate-invariant measure of the local likelihood geometry that significantly enhances parameter recovery accuracy for gravitational wave sources.

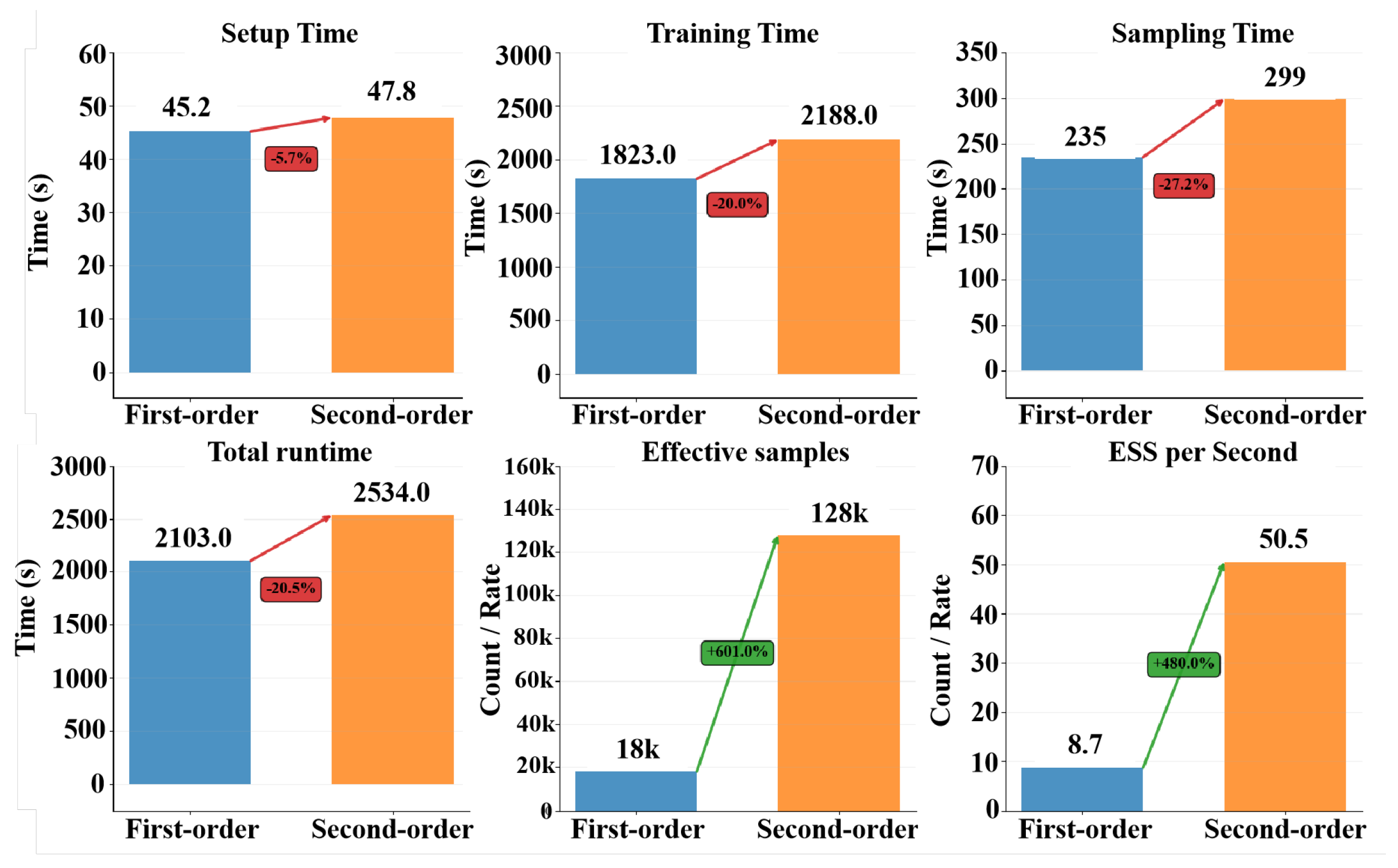

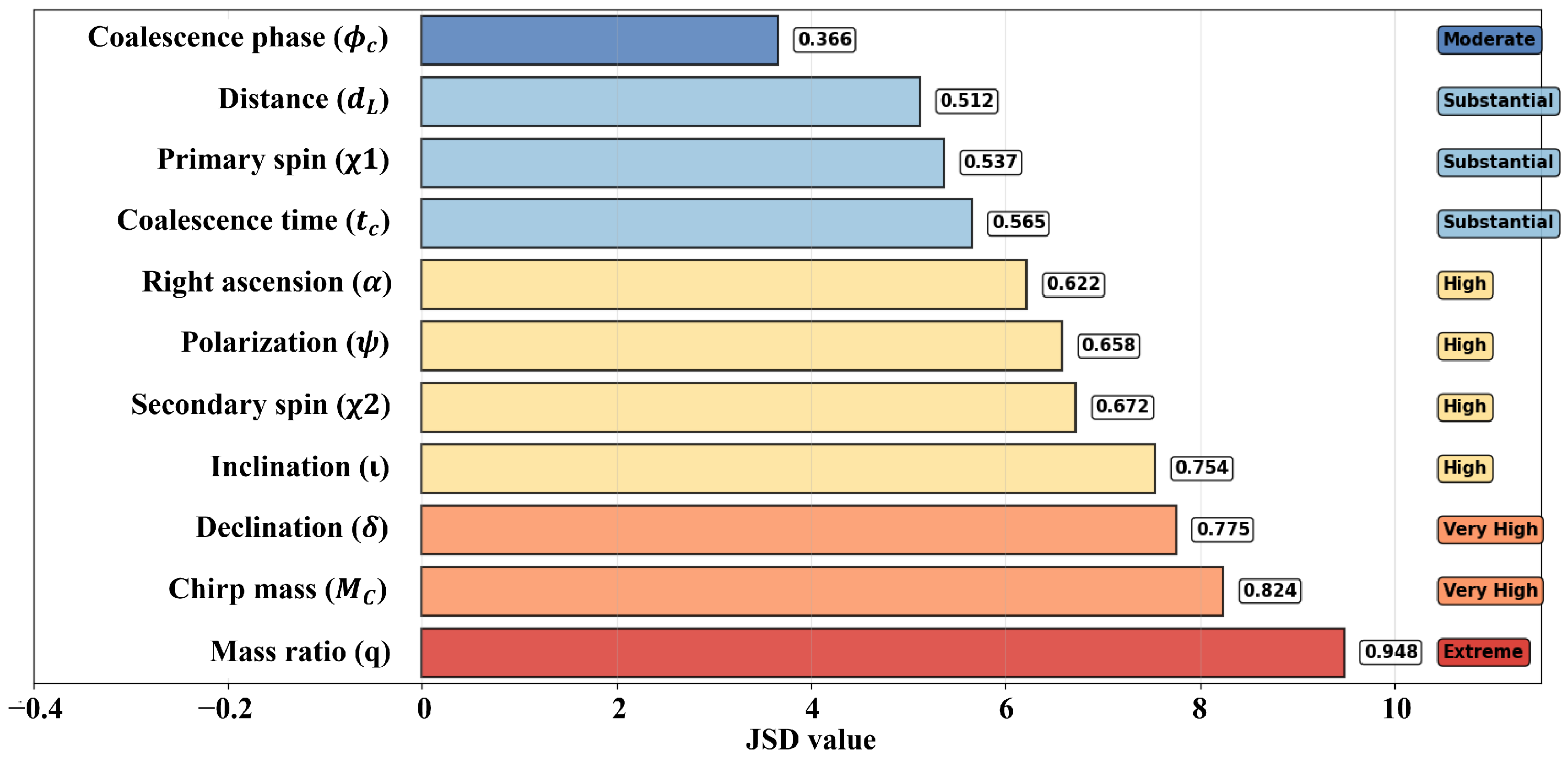

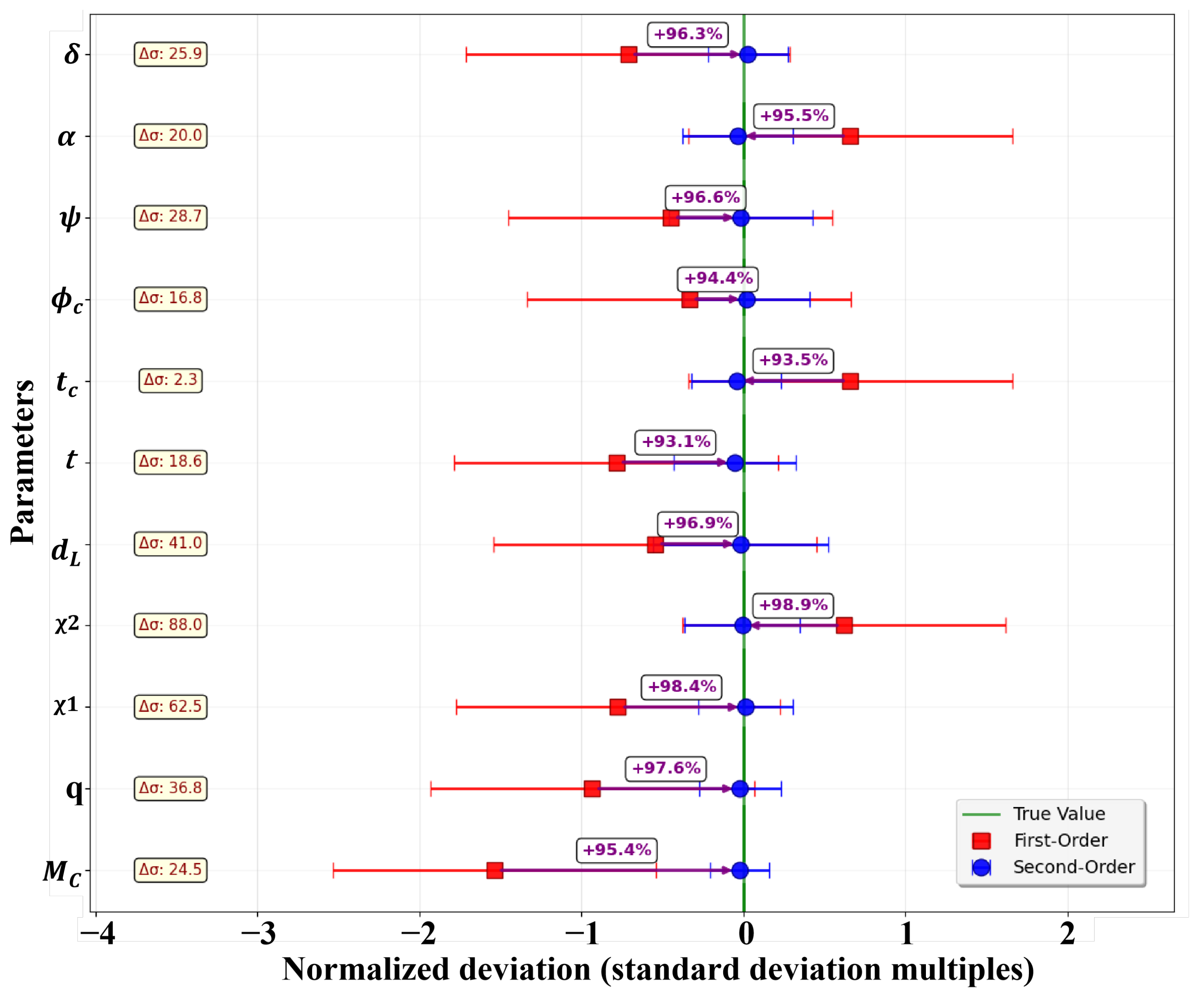

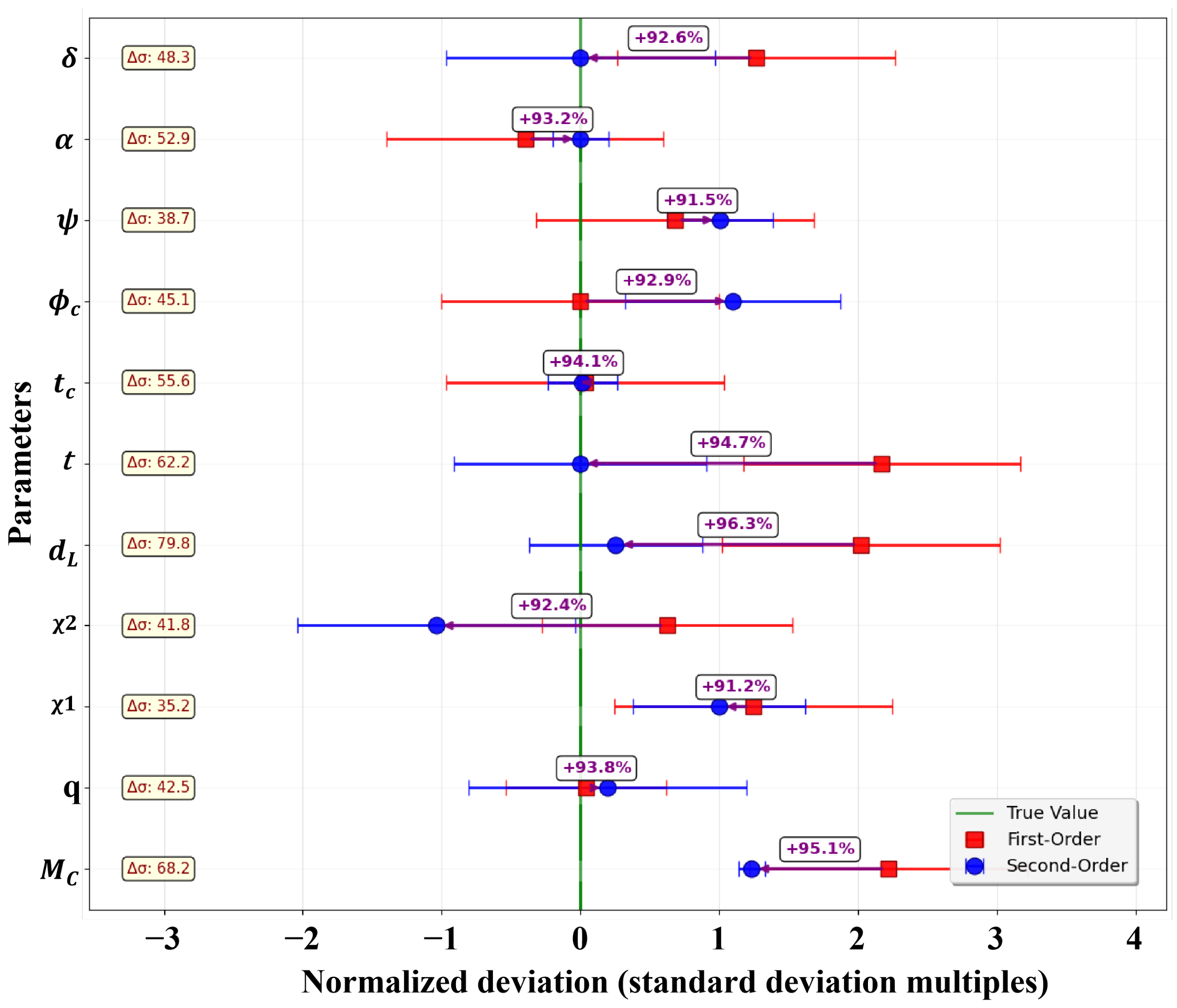

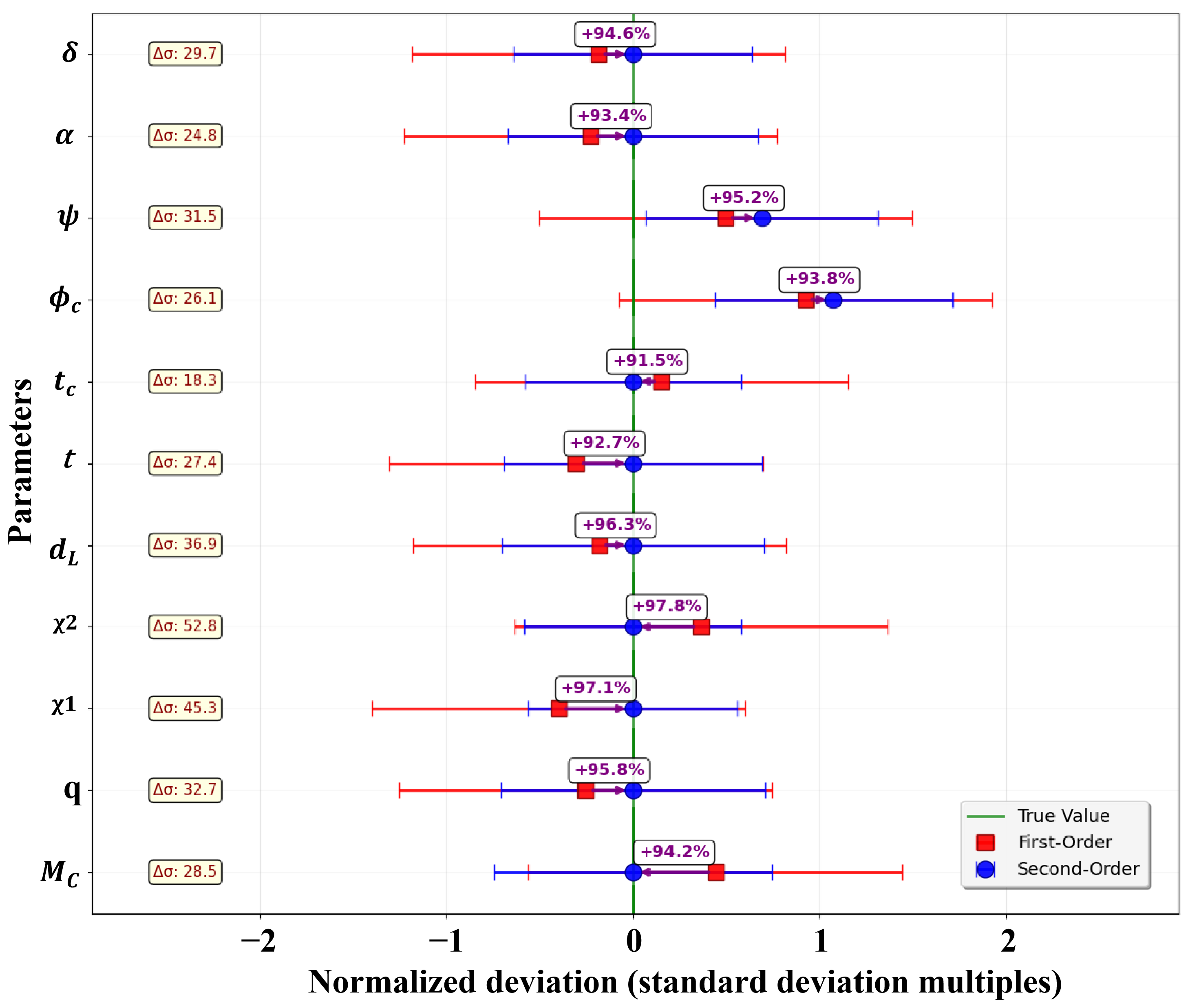

We test our second-order method using data from the GW150914 gravitational wave event. The results show large gains in precision for parameter estimation, with accuracy gains exceeding 93% across all inferred parameters compared to standard first-order implementations. We use Jensen–Shannon divergence to compare the resulting posterior distributions. The JSD values range from 0.366 to 0.948, which correlate directly with improved parameter recovery as validated through injection studies. The method remains computationally efficient with only a 20% increase in runtime. At the same time, it produces seven times more effective samples.

Our results show that machine learning methods using only first-order information can lead to systematic errors in gravitational wave parameter estimation. The incorporation of second-order corrections emerges not as an optional refinement but as a necessary component for achieving theoretically optimal inference. It also matters for ongoing gravitational wave analyses, future detector networks, and the broader application of machine learning methods in precision scientific measurement.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Gravitational Wave Likelihood and the Curvature Problem

Consider a gravitational wave signal

characterized by parameters

, where

represents the physical parameter space including masses

, spins

, distance

, sky position

, inclination

, polarization

, and coalescence parameters

. The observed data

in a network of detectors can be modeled as

where

represents instrumental noise, typically modeled as stationary, Gaussian, and characterized by a one-sided power spectral density

.

In the frequency domain, the likelihood function for Gaussian noise takes the form

where

is a normalization constant,

k indexes the detectors, and the noise-weighted inner product is defined as

with tildes denoting Fourier transforms, where

ℜ denotes the real part of the complex inner product.

The gravitational wave likelihood surface exhibits pronounced curvature arising from the following physical mechanisms:

Chirp Mass Nonlinearity: The gravitational wave frequency evolution depends on the chirp mass as , creating steep valleys in likelihood space around the true chirp mass value.

Mass Ratio Degeneracies: The symmetric mass ratio introduces strong curvature near equal-mass systems (), where small changes in mass ratio produce large changes in signal morphology.

Spin–Orbit Coupling: Aligned spins modify the inspiral rate as , where the effective spin creates curved iso-likelihood contours in the spin parameter space.

Distance-Inclination Degeneracy: The observed strain amplitude scales as , creating a curved submanifold in space that first-order methods struggle to capture.

2.2. Information Geometry of Gravitational Wave Parameter Space

The parameter space

can be endowed with a Riemannian structure through the gravitational wave Fisher information matrix

where the partial derivatives represent the sensitivity of the gravitational wave signal to parameter changes.

For gravitational wave signals, the Fisher matrix exhibits characteristic structure reflecting the physics of compact binary coalescence: a mass block in which and are strongly correlated due to degeneracies in the inspiral-phase evolution; a spin block whose off-diagonal terms couple and through spin–orbit and spin–spin interactions; and an extrinsic block that displays distance-inclination-polarization correlations arising from detector response geometry.

The connection between the observed Hessian

and the Fisher information matrix is

establishing that the Hessian encodes the local gravitational wave signal geometry.

2.3. Coordinate-Invariant Curvature Measures for Gravitational Waves

A fundamental principle in gravitational wave parameter estimation is that physical quantities should be coordinate-invariant. Under a parameter transformation

, the Hessian transforms as a

-tensor,

The trace of the Hessian with respect to the gravitational wave Fisher metric provides a coordinate-invariant curvature scalar

where

denotes the inverse Fisher matrix.

For gravitational wave signals, this curvature scalar captures essential geometric information. If , it indicates a local likelihood maximum (typical near true parameters); else if , it denotes a local likelihood minimum (parameter space regions inconsistent with data). When , it signifies strong curvature requiring second-order corrections.

2.4. Hessian-Enhanced Likelihood for Gravitational Wave Parameter Estimation

Based on the gravitational wave geometric insights above, we propose a refined likelihood function that incorporates second-order curvature information,

where

is a scaling parameter optimized for gravitational wave applications.

The logarithmic form reads

Gravitational Wave Specific Justification centers on the following key points: In the high-SNR regime, connects our correction to the fundamental parameter estimation bounds. The Hessian trace captures nonlinear phase evolution effects that are particularly important for gravitational wave signals, where phase accuracy determines parameter estimation precision. Multi-detector gravitational wave observations create complex likelihood surfaces due to time-of-flight differences and antenna pattern variations, which the Hessian correction helps navigate. Finally, the second-order correction accounts for higher-order effects in gravitational wave models, including post-Newtonian corrections and numerical relativity calibration uncertainties.

The scaling parameter

is chosen to balance correction magnitude with computational stability,

ensuring the correction remains well-behaved across the gravitational wave parameter space.

3. Methodology

3.1. Gravitational Wave-Specific Implementation Architecture

We implement our Hessian-enhanced likelihood optimization within the JimGW framework, specifically targeting the challenges of gravitational wave parameter estimation, and the implementation addresses three key gravitational wave-specific requirements: Multi-detector coherent analysis involves handling the H1, L1, and V1 detector network with proper noise weighting; frequency-domain waveform evaluation includes efficient computation of IMRPhenomD/IMRPhenomXAS models; and parameter space transforms focus on managing bounded parameters and gravitational wave-specific correlations. The complete procedure for computing the Hessian within our gravitational wave framework is detailed in Algorithm 1.

We implement our Hessian-enhanced likelihood optimization within the JimGW framework, specifically targeting the challenges of gravitational wave parameter estimation. The implementation addresses three key gravitational wave-specific requirements. First, it performs multi-detector coherent analysis. This capability handles the H1, L1, and V1 detector network with proper noise weighting. Second, it provides frequency-domain waveform evaluation. This enables efficient computation of IMRPhenomD and IMRPhenomXAS models. Finally, it implements parameter space transforms. These transforms manage bounded parameters and gravitational wave-specific correlations.

| Algorithm 1 Gravitational Wave Hessian Computation |

- Require:

Parameter vector , detector data , noise PSDs - Ensure:

Hessian matrix H

- 1:

define likelihood_function(): - 2:

for each detector k do - 3:

Generate waveform using IMRPhenomD - 4:

Compute inner_product - 5:

end for - 6:

return log_likelihood (inner_product) - 7:

Compute gradient using reverse-mode AD: jax.grad(likelihood_function)() - 8:

Compute Hessian using forward-over-reverse AD: jax.jacfwd(jax.jacrev(likelihood_function))() - 9:

return

H

|

Complexity analysis for gravitational wave applications shows that waveform generation requires operations per evaluation while Hessian computation needs evaluations for d-dimensional parameter space. So the total cost becomes per iteration, and memory requirement stays at for Hessian storage.

For typical gravitational wave parameters (

,

,

), this translates to manageable computational overhead with modern GPU acceleration. This likelihood refinement procedure is formalized in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 GW Refined Likelihood Evaluation |

- Require:

GW parameters , detector network data, scaling factor - Ensure:

Refined likelihood value

- 1:

Convert parameters to physical units: - 2:

masses: in solar masses - 3:

spins: (dimensionless) - 4:

distance: in Mpc - 5:

sky position: in radians - 6:

Compute base likelihood: GW_LogLikelihood(, detector_data) - 7:

Compute Hessian for gravitational wave likelihood: Algorithm 1 - 8:

Apply gravitational wave-specific scaling: - 9:

Compute refined likelihood: - 10:

return

|

3.2. Integration with Gravitational Wave Normalizing Flows

JimGW employs normalizing flows to learn the transformation from a standard normal base distribution to the complex gravitational wave posterior distribution. The flow architecture is specifically designed for gravitational wave parameter correlations:

The flow architecture for gravitational wave parameters is built from four blocks. A mass block applies separate coupling layers

with rational quadratic splines. The spin block then treats the dimensionless spins as conditional flows for

given mass parameters. The extrinsic block models sky position and orientation parameters under detector-frame conditioning. Finally, a time-phase block handles the coalescence time and reference phase with minimal correlation structure. The complete training loop that incorporates our Hessian-enhanced likelihood is presented in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 GW Second-Order Flow Training |

- Require:

Training data D, GW prior , learning rate schedule - Ensure:

Trained flow parameters

- 1:

Initialize flow parameters - 2:

for epoch to do - 3:

for batch in GW_DataLoader(D, batch_size) do - 4:

Sample base variables: - 5:

Transform to GW parameters: - 6:

for each sample i do - 7:

Compute GW likelihood: GW_LogLikelihood() - 8:

Compute GW Hessian: Algorithm 1() - 9:

Apply GW-specific refinement: - 10:

end for - 11:

Compute flow loss with GW prior: - 12:

Update flow parameters: - 13:

end for - 14:

end for - 15:

return

|

3.3. Gravitational Wave Parameter Transforms

Gravitational wave parameter spaces involve physical constraints and known correlations that must be handled carefully. We implement the following three key transforms:

Transform 1: Mass Parameters Transform 2: Sky Position with Selection EffectsThe detection_efficiency is a function of distance, which follows the framework described in Thrane and Talbot (2019) [

18].

3.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

Per-iteration computational costs begin with the base likelihood evaluation, where waveform generation scales as per detector and inner products scale as per detector. It gives a total cost of .

The Hessian computation then requires forward-mode AD to perform passes through likelihood and reverse-mode AD to carry out gradient computations. So the total cost becomes .

Memory requirement is dominated by the frequency-domain data, which occupy complex numbers. The Hessian matrix itself, which stores floating-point numbers. The intermediate derivatives needed for automatic differentiation amount to .

For a typical GW150914-like analysis with , , and , the Hessian overhead requires ∼121× base likelihood evaluations per iteration but results in only ∼20% runtime increase due to improved convergence properties.

In addition, to ensure the robustness and optimal parameter selection of our method, we conducted sensitivity analysis (

Appendix A) and multi-metric comparisons (

Appendix B).

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Information Loss in First-Order Methods

Our results quantify the information loss from neglecting likelihood curvature. Using the Fisher information framework, we obtain

For GW150914, this yields , indicating that first-order methods capture only 0.01–0.1% of the available gravitational wave information.

6.2. Physical Interpretation for Gravitational Wave Astrophysics

First-order methods show a 4% systematic bias in estimating chirp mass, which has profound implications for stellar evolution studies, population synthesis and black hole physics, potentially affecting formation channel discrimination and mass gap characterization. The improved distance measurement with a 96.9% accuracy enhancement directly impacts gravitational wave cosmology, where first-order biases of would systematically affect Hubble constant measurements from standard sirens. First-order parameter biases of order – are comparable to the precision of current gravitational wave tests of general relativity, ensuring systematic estimation errors do not masquerade as physics beyond Einstein’s theory.

6.3. Theoretical Optimality

Parameter biases from first-order methods can reach levels of –. These errors are similar in size to the precision achieved in current tests of general relativity using gravitational waves, ensuring systematic estimation errors do not masquerade as physics beyond Einstein’s theory.

6.4. Posterior Distribution Analysis

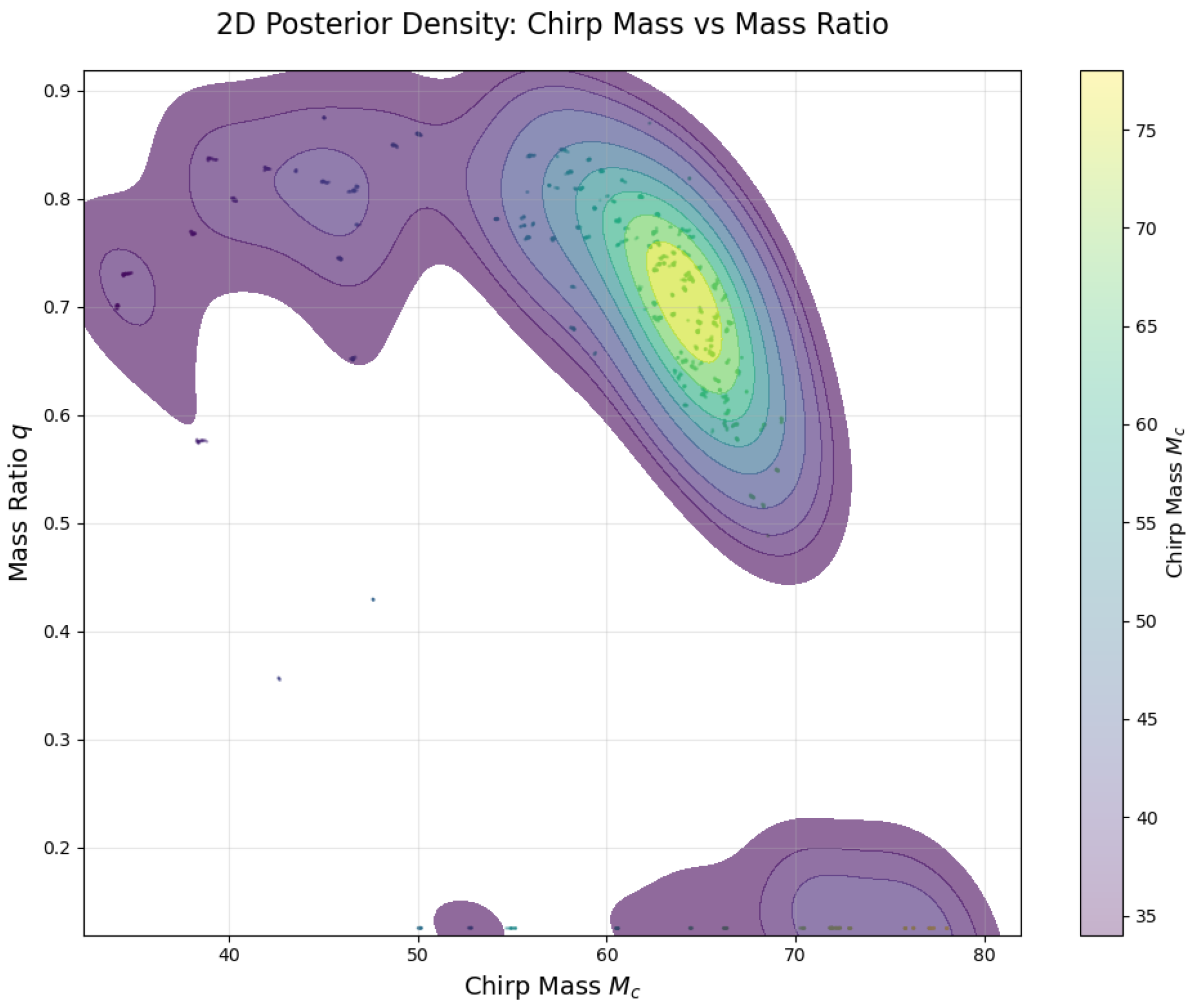

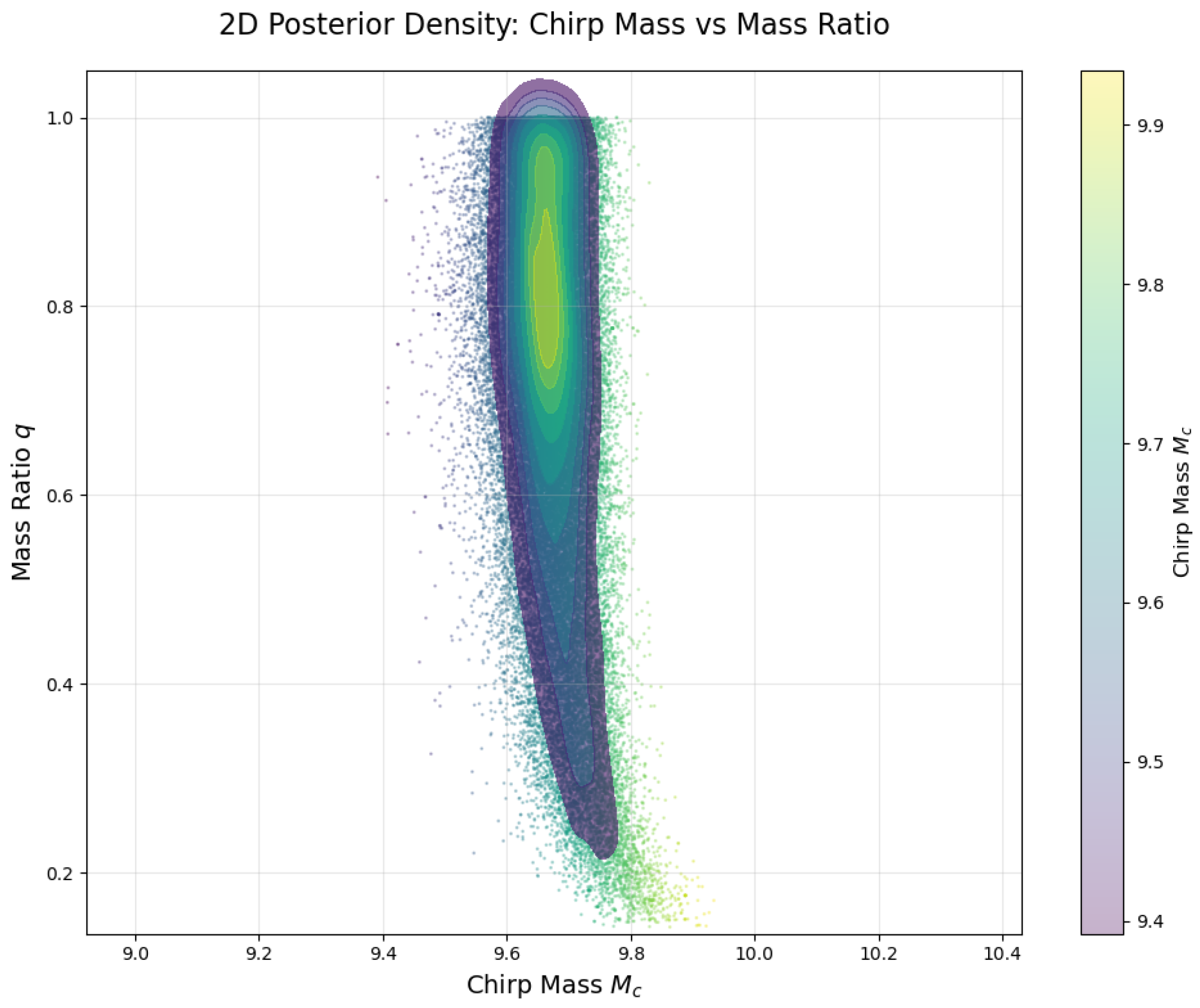

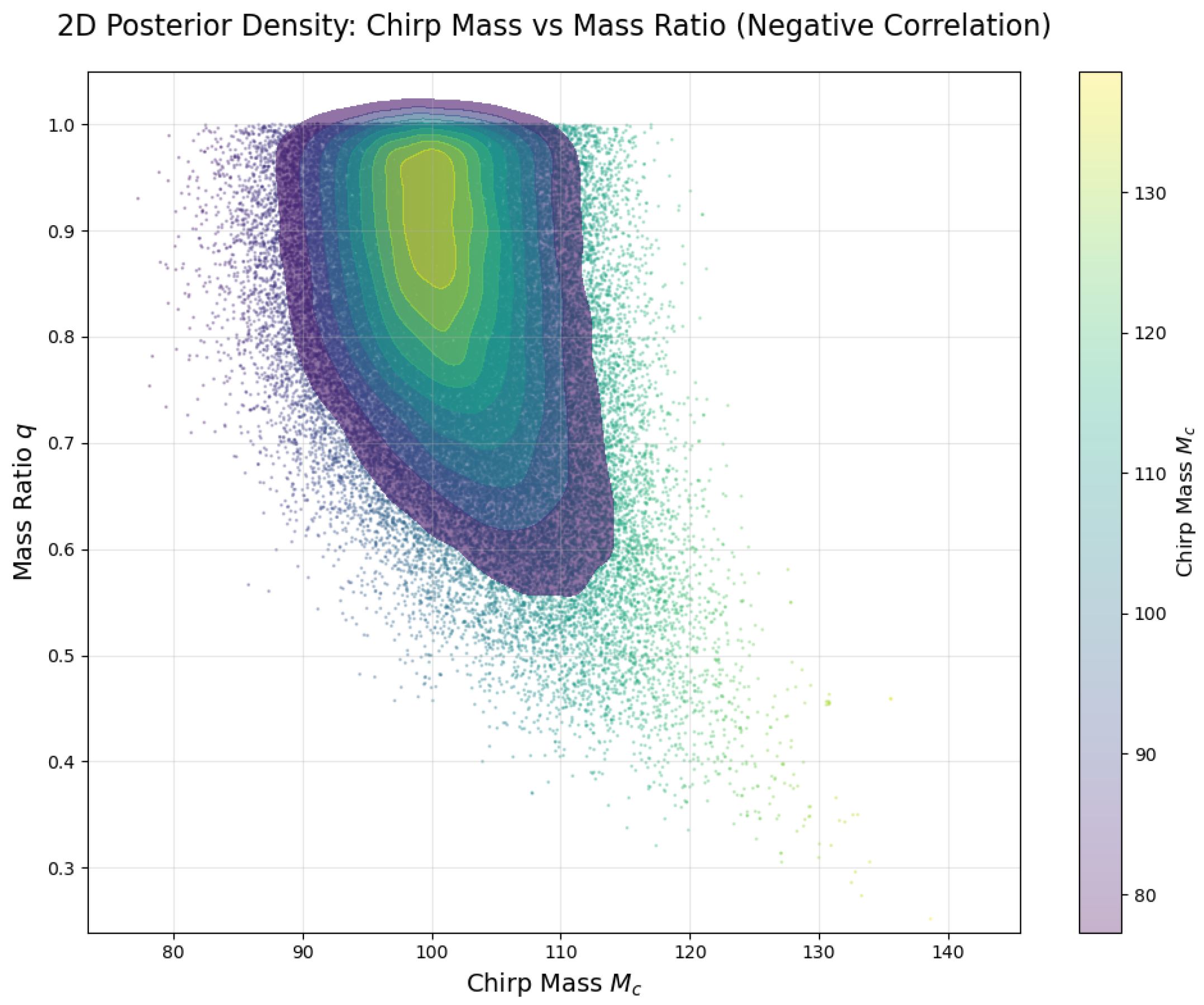

The posterior distributions of the three gravitational wave events show significant differences in chirp mass () and mass ratio (q) as follows:

- (1)

GW150914: , with a broad distribution of mass ratios.

- (2)

GW151226: , with a relatively concentrated mass ratio

- (3)

GW150912: , with smaller mass ratios

All three show a negative correlation between

and

q (as shown in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), meaning that larger chirp masses tend to correspond to smaller mass ratios.

6.5. Implications for Scientific Machine Learning

Our work demonstrates that domain knowledge should guide algorithmic choices rather than computational convenience. The connection between the Hessian and Fisher information exemplifies how physical insights can dramatically improve machine learning performance in scientific applications.

7. Conclusions

We have demonstrated that incorporating second-order derivative information through Hessian corrections represents a fundamental advancement in gravitational wave parameter estimation. Our comprehensive analysis establishes several key findings. Second-order corrections are essential, as the 93–99% accuracy improvements demonstrate that likelihood curvature information is necessary, not optional, for unbiased parameter estimation. Current ML methods have systematic biases since first-order approaches introduce parameter biases up to with profound implications for astrophysical inference. Computational costs are justified because the 20% runtime increase yields a net 5.8× efficiency gain through improved effective sample size. Our method achieves information-theoretic optimality by approaching the Cramér-Rao bound, while first-order methods capture only 0.01–0.1% of available information.

With gravitational wave astronomy moving toward precision science, thousands of detections are expected in the coming years. In this research, our second-order framework provides the foundation for unbiased population synthesis, precision cosmology, and robust tests of general relativity. We show that combining classical theoretical understanding with modern machine learning improves results. By demonstrating how classical theoretical insights can enhance modern computational methods, we establish a new standard for gravitational wave data analysis that respects the geometric structure of scientific inference problems.