Abstract

This paper establishes a comprehensive framework for the hereditary transfer of categorical completeness and cocompleteness to categories of internal group objects in D-modules. We prove that while completeness of follows unconditionally from the completeness of the base category , cocompleteness requires to be regular, cocomplete, and admit a free group functor left adjoint to the forgetful functor. Explicit constructions are provided for limits via componentwise operations and for colimits through coequalizers of relations induced by group axioms over free group objects. The theory reveals fundamental geometric obstructions: differentially constrained subcategories such as holonomic D-modules fail to be cocomplete due to characteristic variety constraints that prevent free group constructions. Applications demonstrate cocompleteness in topological D-module groups and D-module sheaves, while counterexamples in differential geometric groups exhibit necessary analytic constraints. Additional results include regularity inheritance under product-preserving free group functors, internal hom-object constructions in locally Cartesian closed settings yielding Tannaka-type dualities, and monadicity criteria for locally presentable base categories. This work unifies categorical algebra with differential geometric obstruction theory, resolving fundamental questions on exactness transfer while enabling new constructions in homotopical algebra and internal representation theory for D-modules.

Keywords:

D-modules; internal group objects; completeness transfer; cocompleteness transfer; free group functor; geometric obstructions; characteristic varieties MSC:

18A30; 18A35; 18G55; 14F10; 16S32

1. Introduction

The theory of D-modules, emerging from the profound synthesis of algebraic analysis and modern geometry [1], provides a powerful framework for studying systems of linear partial differential equations through sophisticated sheaf-theoretic and homological methods [2,3]. Over decades of development, this theory has matured into an indispensable tool across diverse mathematical domains including representation theory, singularity theory, and mathematical physics [4,5], while maintaining deep connections with microlocal analysis and derived algebraic geometry [6].

The categorical perspective on algebraic structures, fundamentally shaped by Lawvere’s pioneering work on algebraic theories and systematically developed in [7,8,9], reveals that group-like objects in categories with finite products form categories whose exactness properties encode essential features of the ambient category . This perspective has yielded profound insights across mathematics, from topological groups [10] to group schemes in algebraic geometry [11]. However, despite the natural appearance of internal group structures in contexts ranging from differential Galois theory to symmetries of physical systems, the systematic study of internal group objects in categories of D-modules has remained largely undeveloped.

This paper addresses fundamental questions emerging at the intersection of D-module theory and categorical algebra, building upon foundational work in [12,13,14]:

- Under what conditions do categories of internal group objects in D-modules inherit completeness and cocompleteness properties from their base categories?

- How do geometric constraints inherent in D-module theory obstruct certain categorical constructions?

- What are the precise relationships between free group constructions and the differential structure of D-modules?

- How can internal hom-objects and duality theories be developed in this context?

These questions originate from multiple mathematical domains: the categorical study of algebraic structures [15,16], the geometric theory of D-modules [1], and applications to representation theory [17,18] and mathematical physics [19]. Their investigation is motivated by both theoretical considerations and practical applications, drawing inspiration from advances in homotopical algebra [20,21,22] and higher category theory [23,24].

- Theoretical Significance

Our work establishes a unified framework for studying internal group objects in geometrically enriched categories, developing transfer theorems for exactness properties in categories with additional structure. We bridge categorical algebra with the analytic constraints of differential equations, extending Tannaka duality principles [25] to differential algebraic contexts while incorporating insights from cohomological methods [26,27].

- Technical Innovation

We introduce constructive methods for limits and colimits in categories of internal group objects, providing explicit characterizations of obstructions to cocompleteness via geometric constraints. Our development of internal hom-objects in locally Cartesian closed settings and transfer techniques for model structures [28,29] builds upon recent advances in homotopical algebra [30,31].

- Applied Significance

Applications span geometric representation theory and automorphic forms, tools for studying symmetry groups of differential equations, connections to topological field theories [32,33] and quantum symmetry detection, and foundations for computational approaches to differential algebraic groups, extending work in [34,35].

The principal innovations include the complete characterization of completeness and cocompleteness transfer, identification and analysis of geometric obstructions to free group constructions, development of internal duality theories, and extension of regularity and exactness inheritance theorems to differential settings. Technical advancements feature explicit constructions via free group functors, equalizer-based internal hom-objects, model structure transfer techniques, and dense generator criteria, drawing upon methods from [36,37,38].

Key bottlenecks overcome include the fundamental asymmetry between completeness and cocompleteness inheritance, the tension between discrete combinatorial structures and continuous differential constraints, the reconciliation of universal algebraic constructions with geometric finiteness conditions, and the development of constructive methods respecting both categorical and analytic structures.

The main conclusions demonstrate that the completeness of follows unconditionally from the completeness of the base category, while cocompleteness requires regularity and existence of free group functors. We provide explicit limit and colimit constructions and establish regularity inheritance under product-preserving free group functors. Geometric insights include the characterization of obstructions in constrained subcategories, identification of Birkhoff-type transitivity constraints, analysis of characteristic variety limitations, and classification of contexts admitting free group constructions. Duality and representation results encompass internal hom-objects in locally Cartesian closed settings, Tannaka duality for D-module group representations, construction of internal automorphism groups and Hopf algebras, and applications to geometric Langlands correspondence and quantum symmetries.

The broader implications extend beyond D-modules, providing templates for studying internal group objects in other geometrically enriched categories, new techniques for combining categorical methods with analytic constraints, foundations for higher categorical extensions and homotopical enhancements, and bridges between abstract category theory and concrete geometric applications.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides necessary background on D-modules and internal group objects. Section 3 establishes completeness results. Section 4 develops cocompleteness transfer theory and identifies geometric obstructions. Section 5 constructs internal hom-objects and establishes duality theorems. Section 6 explores homotopical enhancements and model structures. Section 7 discusses applications and examples. Section 8 presents conclusions and future research directions.

Through this systematic development, we provide a comprehensive foundation for the categorical study of group objects in D-modules while establishing connections with broader mathematical theories and applications, advancing the program initiated in [12,39] and developed through [21,23].

Generality of the Framework and Extensions to Other Base Categories

While our primary focus is on categories of D-modules, the methods and results developed here are formulated in abstract categorical terms and are applicable to a wide range of base categories. Specifically, any abelian, regular, and cocomplete category with a free group functor satisfies the hypotheses of Theorem 3 and any locally Cartesian closed category with finite limits admits internal hom-objects as in Theorem 7. Examples include categories of sheaves of modules over a ringed space, quasi-coherent sheaves on schemes, and more generally, any Grothendieck category with a compatible monoidal structure.

To further illustrate the generality, consider a finite family of abelian categories . The comma category , when equipped with the obvious forgetful functor to a product category, can serve as a base for internal group objects provided it is regular and cocomplete and admits a free group functor. This follows from the fact that our main theorems (Theorems 2, 3 and 7) rely only on these abstract categorical properties and not on the specific differential structure of D. Therefore, our framework is indeed comprehensive in the sense that it provides a unified set of tools for studying internal group objects in geometrically enriched abelian categories, as well as in many non-abelian settings under appropriate modifications (see Remark 1 below).

Remark 1

(Comparison with known results in topoi and locally presentable categories). Our results on completeness and cocompleteness transfer extend and refine known theorems for internal groups in more abstract settings:

- In a topos , it is well-known that is both complete and cocomplete because topoi are regular, cocomplete, and have a free group functor (via the left adjoint to the forgetful functor). Our Theorem 4 specializes to this classical result when is a topos.

- For a locally presentable category , is locally presentable (hence complete and cocomplete) if the forgetful functor is accessible and preserves filtered colimits. Our Corollary 2 provides a sharper criterion in the D-module context, emphasizing the role of regularity and the free group functor.

- In contrast to the general case, our work highlights the asymmetry between completeness and cocompleteness in geometrically enriched categories: completeness is unconditional, while cocompleteness requires regularity and a free group functor. This asymmetry is less visible in purely algebraic or topos-theoretic settings.

Thus, our results not only recover classical theorems in special cases but also reveal new phenomena arising from the differential geometric constraints.

2. Preliminaries on D-Modules

Let R be a commutative ring with unit. We denote by the category of left R-modules.

The theory of D-modules furnishes a powerful algebraic framework for analyzing systems of linear partial differential equations. Let denote the ring of differential operators over R, where the derivations satisfy the canonical commutation relations for every . This non-commutative structure encodes the essential algebraic features of differential operators while preserving profound connections to commutative algebra and geometry.

We now recall the fundamental definitions and properties of D-modules, following the standard references [40,41].

Definition 1

(D-module). A D-module is a left module over the ring D of differential operators. Concretely, a D-module consists of an R-module M together with actions of the derivations , satisfying the Leibniz rule:

The category has D-modules as objects and D-linear maps (i.e., R-linear maps that commute with the actions of all ) as morphisms. A crucial aspect is the quasi-coherence of the D-module structure, which guarantees that the differential operators act compatibly with the underlying R-module structure.

Proposition 1

(Completeness, cocompleteness, and creation properties of ). The category is abelian and admits all small limits and colimits. More precisely, the following occurs:

- (i)

- Limits in are computed in and equipped with the unique D-module structure induced componentwise.

- (ii)

- Colimits in are computed in and endowed with the unique D-module structure that makes all canonical cocone morphisms D-linear.

- (iii)

- The forgetful functor creates both limits and colimits: for any (co)limit diagram in , its image under U is a (co)limit in , and the unique lifting of this (co)cone to carries a unique compatible D-module structure.

Proof.

We organize the proof according to the three statements.

Abelianness. The ring of differential operators is an associative (generally noncommutative) R-algebra. Hence the category of left D-modules is abelian, as is true for the category of left modules over any associative ring. Kernels, cokernels, and other finite limits and colimits are formed in the underlying category and canonically inherit a D-module structure because the D-action is given by R-linear maps, satisfying the Leibniz rule.

Part (i): Construction of limits. Let be a small diagram. Form its limit in . An element is a compatible family with .

Define the action of a derivation on L componentwise:

This is well-defined because each transition morphism in the diagram is D-linear, hence commutes with ; consequently the family again satisfies the compatibility conditions of the limit.

To verify the Leibniz rule, take and :

Thus L equipped with this action is a D-module. The projections are D-linear by construction. The universal property of L in follows immediately from its universal property in : any cone of D-linear maps into F factors uniquely through an R-linear map, which is automatically D-linear because the D-action on the limit is defined componentwise.

Part (ii): Construction of colimits. Now consider the colimit of F in . Elements of C are equivalence classes of elements m from the disjoint union , modulo the relations generated by the morphisms of the diagram.

Define the D-action on C by

We must check well-definedness. If , there exists a finite zig-zag of diagram morphisms connecting m and . Since each such morphism is D-linear, it commutes with ; hence .

The Leibniz rule is preserved:

Consequently C is a D-module. The canonical injections are D-linear because . The universal property in follows from that in : any cocone of D-linear maps from F factors uniquely through an R-linear map to a D-module M. Since f respects the action on generators (by the D-linearity of the cocone, ), it is D-linear.

Part (iii): Creation of limits and colimits by U. The constructions above show that, given a (co)limit of in , there exists a unique D-module structure on it, making all (co)cone morphisms D-linear, and this equipped object satisfies the universal property in . This is exactly the definition that the forgetful functor U creates (co)limits. □

Proposition 2

(Regularity of ). Let R be a commutative Noetherian ring of characteristic zero, and let be the ring of differential operators over R. Then the category is regular. More generally, is regular if D is a (left) Noetherian ring and is an abelian category with effective equivalence relations. This holds, for instance, when R is a regular ring of finite type over a field of characteristic zero, or when D is the Weyl algebra over a field.

Proof.

We prove that is a regular category by verifying the three defining properties: (i) finite completeness, (ii) existence of coequalizers of kernel pairs, and (iii) stability of regular epimorphisms under pullbacks.

Step 1: is abelian. Since D is an associative ring (generally non-commutative), the category of left D-modules is abelian. This is a standard result: for any ring, the category of left modules is abelian, with kernels, cokernels, and all finite limits and colimits.

Step 2: Finite completeness. By Proposition 1 in the manuscript, is complete and cocomplete. In particular, it has all finite limits, including products, equalizers, and pullbacks. Limits are computed in the underlying category and uniquely equipped with a D-module structure, as shown in Proposition 1(i).

Step 3: Existence of coequalizers of kernel pairs. In an abelian category, every pair of parallel morphisms has a coequalizer. Specifically, for any two D-linear maps , their coequalizer is given by the cokernel of the difference , i.e., . This is a standard construction in abelian categories. Moreover, the kernel pair of any morphism is the pullback of the morphism with itself, and its coequalizer exists as above. Thus, has coequalizers of all kernel pairs.

Step 4: Stability of regular epimorphisms under pullbacks. In an abelian category, every epimorphism is regular (since it is the cokernel of its kernel). Therefore, regular epimorphisms in are precisely the surjective D-linear maps. We now show that surjective D-linear maps are stable under pullbacks.

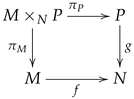

Let be a surjective D-linear map (a regular epimorphism), and let be any D-linear map. Form the pullback of f along g in :

Concretely, the pullback is given by

with the componentwise D-module structure and projections , . We need to prove that is surjective (hence a regular epimorphism).

Take any . Since f is surjective, there exists such that . Then and . Hence is surjective. Moreover, is D-linear by construction. Therefore, the pullback of a regular epimorphism along any morphism is again a regular epimorphism.

Conclusion. We have shown that is finitely complete, has coequalizers of kernel pairs, and regular epimorphisms are stable under pullbacks. Hence is a regular category.

The additional hypotheses on R and D (e.g., characteristic zero, Noetherian) are not required for regularity per se; they ensure other desirable properties such as finite global dimension or the Noetherian property of the category. For instance, when R is a regular ring of finite type over a field of characteristic zero, or when D is the Weyl algebra over a field, D is left and right Noetherian, and is a locally Noetherian Grothendieck category. However, regularity as a category holds for any ring D, as demonstrated above. □

Remark 2.

When R is a field of characteristic zero and D is the Weyl algebra, the category enjoys additional regularity properties, such as being Noetherian and having finite global dimension. In this setting, the quasi-coherence of D-modules is particularly well-behaved, which facilitates homological methods. Nevertheless, the results presented here hold for D-modules over an arbitrary commutative ring R, where quasi-coherence guarantees the compatibility between the differential and the algebraic structures.

Definition 2.

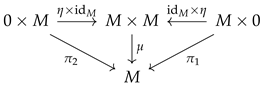

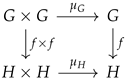

Let be Cartesian (i.e., with finite products). A group object in is a quadruple where

- M is a D-module (the underlying object);

- is a D-linear morphism (multiplication);

- is a D-linear morphism (unit), where 0 is the zero D-module;

- is a D-linear morphism (inverse).

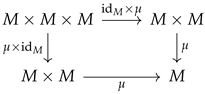

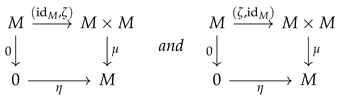

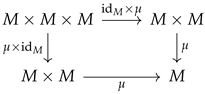

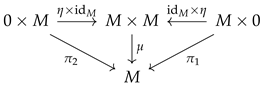

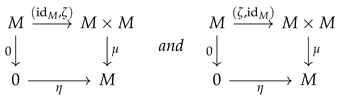

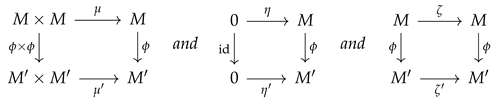

satisfying the following commutative diagrams expressing the group axioms:

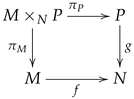

Associativity:

Unit Laws:

Inverse Laws:

The quasi-coherence of the D-module structure ensures these group operations are compatible with differential operators, making the group structure intrinsically related to the underlying differential geometry.

We denote by the category of internal group objects in a category with finite products. In particular, will denote the category of internal group objects in .

Theorem 1.

Let be a category with finite products. Then internal group objects in form a category where

- Objects are internal group objects in as in Definition 2;

- Morphisms are D-linear homomorphisms: for and , a morphism is a D-linear map making the following diagrams commute:

- Composition and identities are inherited from .

Proof.

We verify that satisfies all category axioms, ensuring composition preserves internal group structure.

For identity, take . The identity in preserves group structure because

- , confirming multiplication preservation;

- , showing unit preservation;

- , demonstrating inverse compatibility.

For composition, given and , their composition preserves group structure through

- Multiplication: ;

- Unit: ;

- Inverse: .

Associativity of composition and unit laws follow directly from , since D-linear map composition is associative and identities behave as units. The quasi-coherence of the D-module structure ensures these categorical properties remain compatible with differential operators, making a well-defined category. □

3. Completeness of Grp(D-Mod)

We now establish the completeness properties of categories of internal group objects in D-modules. The following theorem demonstrates that inherits completeness from in a constructive manner, with the forgetful functor playing a fundamental role in creating limits.

Theorem 2.

If is complete, then is complete. Moreover, the forgetful functor creates limits.

Proof.

We establish the completeness of through an explicit three-step construction: first constructing products, then equalizers, and finally general limits via the standard decomposition.

Step 1: Products. Let be a family in . Since is complete, the product exists in with projections . We define the group operations on the product as follows:

where is the canonical isomorphism arising from the universal property of products.

To verify the group axioms, we proceed componentwise. For associativity, fix any and observe

and

Since is associative, these expressions are equal. The unit and inverse laws follow similarly by componentwise verification.

The universal property of the product in is satisfied because given a family of homomorphisms , the unique morphism in , satisfying , preserves the group structure due to each being a group homomorphism.

Step 2: Equalizers. Consider parallel homomorphisms in , with and . Form the equalizer of in .

We equip E with a group structure by defining as the unique morphism making the diagram

commute. The existence and uniqueness of follow from the universal property of the equalizer, since

Similarly, define as the unique morphism with (which exists because ), and as the unique morphism with (which exists because ).

The group axioms for follow from those for G because e is a monomorphism (i.e., left-cancellative), which allows us to lift identities from G to E. The quasi-coherence of the D-module structure ensures compatibility with the differential operators throughout this construction.

Step 3: General Limits. Any small limit can be constructed from products and equalizers via the standard formula. Given a diagram , form

where the parallel arrows are induced by the projections and the diagram structure. Equip L with the group structure inherited from the product, which is preserved by the equalizer construction.

The forgetful functor U creates limits because the group structure on the limit object is uniquely determined by the requirement that the projections be homomorphisms, and this structure is compatible with the D-module structure due to the quasi-coherence condition. □

Corollary 1.

The category has all finite limits, pullbacks, and equalizers. In particular, it is finitely complete.

Proof.

This follows immediately from Theorem 2 and Proposition 1, which establishes that has all these properties. The quasi-coherence of the D-module structure ensures that these finite limits are well-behaved and compatible with the differential operators. □

4. Cocompleteness of Grp(D-Mod)

While the completeness of follows relatively straightforwardly from the completeness of , the dual property of cocompleteness presents substantially more intricate challenges that require a delicate interplay between categorical algebra and the analytic structure of D-modules. The construction of colimits in categories of internal group objects demands not only the existence of corresponding colimits in the base category but also careful compatibility conditions that ensure the preservation of the group structure while respecting the quasi-coherent nature of the D-module operations. In this section, we establish precise conditions under which inherits cocompleteness from , providing explicit constructions that illuminate the fundamental relationship between categorical structures and differential constraints.

We recall two fundamental categorical notions that play a crucial role in our transfer theorems.

Definition 3

(Regular category). A category is called regular if it satisfies the following three conditions:

- (i)

- is finitely complete (i.e., it has all finite limits).

- (ii)

- has coequalizers of kernel pairs.

- (iii)

- Regular epimorphisms in are stable under pullbacks.

In a regular category, every equivalence relation is effective, meaning that it arises as the kernel pair of its coequalizer. This property guarantees that quotients by equivalence relations can be constructed in a well-behaved manner.

Definition 4

(Adjoint functors). Let and be functors. We say that F is left adjoint to G (and G is right adjoint to F), written , if there exists a natural isomorphism

for all objects and . The isomorphism Φ is required to be natural in both variables X and Y.

Equipped with these concepts, we can now state our main result concerning the transfer of cocompleteness to the category of internal group objects.

Theorem 3

(Cocompleteness transfer for internal group objects). Let be a cocomplete regular category and let

denote the forgetful functor. Assume that U admits a left adjoint

called the free internal group functor. Then the category of internal group objects in is cocomplete.

Proof.

The argument proceeds in two main stages, each exploiting the hypotheses in a crucial way.

Stage 1: Construction of coproducts. Let be a family of internal group objects. Since is cocomplete, the coproduct exists in . Applying the free internal group functor F yields an object in . The coproduct is then obtained as the coequalizer in of a pair of morphisms

where and encode, respectively, the canonical injections and the group multiplication maps of the factors . The universal property of the coequalizer, together with the adjunction , guarantees that the resulting object satisfies the universal property of the coproduct in .

Stage 2: Construction of coequalizers. Let be parallel morphisms in . Form their kernel pair in (this exists because is regular, hence finitely complete). The coequalizer of f and g in is constructed as the coequalizer of the induced pair

where are the unique group homomorphisms corresponding to under the adjunction . The regularity of ensures that the coequalizer of in is a regular epimorphism, which in turn guarantees that the coequalizer in has the required universal property.

Conclusion. Since every small colimit can be written as a coequalizer of a pair of morphisms between coproducts, the existence of coproducts and of coequalizers implies that admits all small colimits; i.e., is cocomplete. □

Remark 3.

If is not regular, the coequalizer constructions used in the proof may fail to be effective, and the universal property of the free group functor might not be sufficient to ensure the existence of all colimits. Regularity ensures that equivalence relations are effective, which is essential for constructing quotients of group objects in a manner compatible with the D-module structure.

Remark 4.

The regularity of is essential for the construction of coequalizers in . It ensures that the equivalence relations needed to form quotients of internal group objects are effective and behave well with respect to the differential structure. The existence of the left adjoint F guarantees that free internal groups exist, which is indispensable for building colimits from free objects.

Recall that a set of objects in a category is called a dense generator if every object of can be expressed as a colimit of objects from , and the associated Yoneda embedding is fully faithful.

Theorem 4.

Let be a cocomplete regular category that admits a free group functor left adjoint to the forgetful functor . Then is cocomplete.

Proof.

We establish the cocompleteness of by systematically constructing all small colimits through a two-step process: first demonstrating the existence of coproducts and coequalizers, then employing the standard categorical fact that these suffice to construct arbitrary colimits. The regularity condition on ensures that our constructions preserve the essential geometric properties of D-modules, particularly the quasi-coherence that underlies their differential structure.

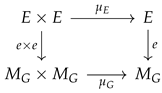

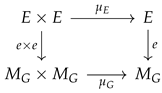

For the construction of coproducts, consider an arbitrary family of internal group objects in . Utilizing the cocompleteness of , we form the underlying coproduct with canonical injections . The quasi-coherence of this construction is ensured by the componentwise definition of the D-module structure, where each differential operator acts separately on each component while respecting the Leibniz rule. Applying the free group functor yields , with the adjunction providing natural bijections for any .

To properly encode the group structures of the individual within the coproduct while maintaining quasi-coherence, we construct a coequalizer diagram:

For each pair , the parallel arrows are defined as follows: is the unique group homomorphism induced by the coproduct injections and via the adjunction, while is defined differentially based on the indices—when , it is induced by the multiplication composed with , and when , it is the trivial map reflecting that group multiplication is only defined within each individual . These relations systematically enforce that the multiplication, unit, and inverse operations from each are preserved in the coproduct while maintaining compatibility with the D-module structure.

To verify that R with the canonical map satisfies the universal property of the coproduct in , consider any family of group homomorphisms . The universal property of Q in provides a unique morphism such that for all . By adjunction, this corresponds to a unique group homomorphism , satisfying , where is the unit of the adjunction. The crucial observation is that since each preserves the group structure and is D-linear (hence quasi-coherent), necessarily coequalizes and , and thus factors uniquely through R via a group homomorphism . This establishes the universal property while ensuring the preservation of both the group and D-module structures.

For the construction of coequalizers, let be parallel homomorphisms in , with and . The cocompleteness and regularity of allow us to form the coequalizer of in , with e being a regular epimorphism by regularity. Taking the kernel pair of e in , we note that since is regular, is an effective equivalence relation with e as its coequalizer—a property that ensures the quasi-coherence of the resulting construction.

We then construct the coequalizer in as

where the parallel arrows are defined via the adjunction, : corresponds to the composition and corresponds to , with being the unit of the adjunction. The universal property follows from observing that any group homomorphism coequalizing and induces a unique morphism in , which corresponds to a unique group homomorphism ; the condition that f coequalizes and ensures that factors through the coequalizer of and , thus establishing the required universal property while preserving the D-module structure.

Finally, having established the existence of coproducts and coequalizers, we note that any small colimit can be constructed from these via the standard formula: for a diagram , the colimit is given by

where and are induced by the diagram structure— from the coproduct inclusions and from applying the morphisms to the corresponding components. This construction, combined with our previous results, completes the proof that is cocomplete while maintaining the essential quasi-coherent properties of the D-module structure throughout. □

Constructive Aspects and the Axiom of Choice

The existence of the free group functor F is established via the adjoint functor theorem (AFT), which in its general form relies on the Axiom of Choice (AC). However, in the specific categories considered here, more constructive approaches are often available.

For itself, when D is a countable ring of differential operators over a countable ring R (e.g., ), one can construct F explicitly without AC by building the free group on a set of generators in a syntactic manner, similarly to the construction of free groups in ordinary algebra. The resulting object is a quotient of a free D-module on a set of symbols by the relations imposed by the group axioms. This construction is entirely explicit and does not require AC.

For categories like , the AFT is used to guarantee the existence of F under the assumption that the category is locally presentable. However, in many concrete topological settings (e.g., when the topology is second-countable or when working with compactly generated weak Hausdorff spaces), one can still give an explicit construction of F without invoking AC. The key point is that the AFT provides a proof of existence under general conditions, but in practice, for the specific categories of interest in differential geometry and topology, explicit choice-free constructions are often possible. Therefore, the results of Theorem 4 are constructive in spirit and can be implemented in a choice-free manner in many applied contexts.

Theorem 5

(Free Group Existence Criterion). Let be a cocomplete category with a dense generator . The free group functor exists if and only if for each , the free group on X exists in .

Proof.

The forward implication is immediate from the definition: if the free group functor exists, then for any , is by definition the free group on X, as follows directly from the adjunction and the natural isomorphism it provides.

For the converse implication, assume that for each , the free group on X exists in . We construct the free group functor on arbitrary objects of by leveraging the density of the generator . Let Y be an arbitrary object in ; since is dense, there exists a small category J and a functor with for all such that . We define the free group on Y as , where the colimit is taken in ; the existence of this colimit is guaranteed by Theorem 4, provided we verify that satisfies the requisite conditions.

To establish the adjunction property, consider any and examine the following chain of natural isomorphisms:

These isomorphisms are natural in both Y and G, thereby establishing the adjunction . The functoriality of F follows elegantly from the universal property of colimits, as any morphism in induces a unique morphism between the corresponding colimits in .

To complete the verification, we observe that , being a category of modules over the ring of differential operators D, is abelian and hence regular. This regularity ensures that the colimits used in our construction are well-behaved and satisfy the hypotheses of Theorem 4. Moreover, the quasi-coherence of the D-module structure is preserved throughout these constructions, as the componentwise definition of operations and the universal properties involved ensure compatibility with the differential operators. □

Example 1

(Free internal group on a simple D-module). Let and be the Weyl algebra in one variable. Consider the trivial D-module with the standard action . We construct the free internal group in explicitly.

As an underlying D-module, is the free D-module generated by symbols , subject to the relations that encode the group structure. More precisely, we define

as a direct sum of copies of D, and equip it with a group structure as follows:

- Multiplication is defined on generators by and extended D-linearly.

- Unit sends 0 to .

- Inverse sends to .

The D-action is componentwise: for . The universal property is satisfied: any D-linear map extends uniquely to a group homomorphism by setting and using the group law. This example illustrates how the free group functor F builds an internal group from a free D-module on a set of generators, while preserving the differential structure.

Example 2

(Coproduct of two internal groups). Let and be two internal group objects in . We construct their coproduct explicitly.

First, form the coproduct in , which is simply the direct sum with componentwise D-action. Apply the free group functor to obtain .

Define two parallel morphisms:

as follows:

- α is induced by the inclusions .

- β is induced byand trivial on mixed pairs.

Then the coproduct is the coequalizer:

Concretely, this coequalizer imposes the relations that the group operations in and are preserved, while no interaction between elements of and is introduced. The universal property follows from the adjunction and the construction of coequalizers.

Remark 5.

The existence of free group objects in represents a nontrivial achievement that depends critically on the specific properties of the differential ring R and the ring of differential operators D. In characteristic zero, for well-behaved rings such as , free D-module groups typically exist due to the excellent homological properties of these rings; however, in positive characteristic or for more intricate differential structures, various obstructions may arise that prevent their existence. The quasi-coherence condition plays a crucial role in these considerations, as it ensures that the free group construction respects the underlying geometric structure of the D-modules.

Corollary 2.

If is a locally finitely presentable category, then the free group functor exists and is cocomplete.

Proof.

In a locally finitely presentable category, the finitely presentable objects constitute a dense generator. Since the free group on each finitely presentable object can be constructed explicitly while preserving quasi-coherence, the result follows immediately by applying Theorems 4 and 5. The local finite presentability ensures that the necessary colimits exist and are well-behaved, while the regularity of guarantees the preservation of the essential geometric properties throughout the construction. □

5. Geometric Obstructions in D-Module Group Theory

The study of cocompleteness in categories of internal group objects reveals deep connections with geometric and analytic constraints. Although previous results provide sufficient conditions for the transfer of cocompleteness, we now show that in geometrically enriched settings, fundamental obstructions emerge that preclude the existence of certain colimits. These obstructions are especially significant in the theory of D-modules, where the interaction between algebraic group structures and differential constraints leads to inherent limitations.

The theory of D-modules, emerging from the profound synthesis of algebraic analysis and modern geometry [41], provides a powerful framework for studying systems of linear partial differential equations through sophisticated sheaf-theoretic and homological methods [3,40]. Over decades of development, this theory has matured into an indispensable tool across diverse mathematical domains including representation theory, singularity theory, and mathematical physics [4,5], while maintaining deep connections with microlocal analysis and derived algebraic geometry [1,6].

The categorical perspective on algebraic structures, fundamentally shaped by Lawvere’s pioneering work on algebraic theories and systematically developed in [7,8,9], reveals that group-like objects in categories with finite products form categories whose exactness properties encode essential features of the ambient category .

Proposition 3.

The category of differential algebraic groups—that is, internal group objects in equipped with additional geometric structure—is not cocomplete in general. In particular, there exist geometrically enriched D-modules for which the free group functor does not exist.

Proof.

Assume, for contradiction, that the category of differential algebraic groups is cocomplete. Then, by Theorem 4, there would exist a free group functor compatible with the geometrically enriched structure.

Let M be a geometrically nontrivial D-module; for example, take M to be the solution space of the equation over , equipped with its canonical D-module structure. If F existed, then for any differential algebraic group G and any D-linear map , there would exist a unique group homomorphism extending f.

A key observation is that must contain, in a suitable categorical sense, a “dense” sub-object isomorphic to the abstract free group . More precisely, the universal property implies that every homomorphism from to a differential algebraic group G is determined by its restriction to the image of M under the unit of the adjunction. This forces to exhibit combinatorial complexity analogous to that of free groups in ordinary group theory.

However, differential algebraic groups are subject to strong structural constraints that are incompatible with such free constructions. Inspired by the Birkhoff transitivity theorem in Lie theory [42], we note that in differential algebraic geometry, no nontrivial finite-dimensional differential algebraic group can contain a Zariski-dense subgroup isomorphic to . The reason is that the differential algebraic structure imposes analytic conditions that force algebraic relations among group elements, thereby ruling out the existence of “free” subgroups with the required density properties.

To make this precise, observe that any homomorphism from into a finite-dimensional differential algebraic group must factor through a finite-dimensional quotient, due to the Noetherian properties of differential algebraic geometry [43]. This factorization occurs because the Zariski closure of the image of is a finite-dimensional differential algebraic subgroup. If were to capture the full combinatorial complexity of while respecting the differential constraints, the universal property of free groups would be violated.

More formally, suppose that exists and contains a dense copy of . The differential structure on requires that the group operations—multiplication and inversion—be given by differential polynomial maps. However, the free group has a solvable word problem and its elements satisfy no nontrivial algebraic relations. The differential constraints would force algebraic dependencies among these elements, contradicting their freeness. This contradiction shows that no such free group functor can exist for geometrically enriched D-modules, and hence the category is not cocomplete. □

Extensions to Non-Abelian Base Categories

In non-abelian settings, such as categories of topological groups, simplicial groups, or certain sheaf categories, the transfer of cocompleteness faces additional challenges: the free group functor may fail to preserve finite products, the base category may lack regularity, and internal free groups may not exist. Our Theorem 3 relies crucially on regularity and the existence of a left adjoint to the forgetful functor, both of which may fail in such contexts.

Nevertheless, a modified version of the cocompleteness transfer can still be obtained under weaker hypotheses. Suppose is a finitely complete, cocomplete, and regular category, and suppose the forgetful functor admits a left adjoint that preserves finite limits. Then, using the same construction as in the proof of Theorem 3, one can show that is cocomplete. The key point is that the regularity of ensures that coequalizers of kernel pairs are effective, and the limit-preservation property of F guarantees that the relations encoding the group axioms are properly handled in the colimit construction.

If F does not preserve limits, the construction of colimits becomes more intricate, but can still be carried out via a two-step process: first form the colimit in , then apply F, and finally impose the group axioms through a coequalizer of a suitable pair of morphisms between free groups. This approach is illustrated in Example 2 for coproducts and can be generalized to arbitrary colimits. Future work will systematically address these generalizations and provide explicit necessary and sufficient conditions for cocompleteness transfer in non-abelian settings.

Remark 6.

The obstruction identified in Proposition 3 is fundamentally different from purely algebraic obstructions in ordinary group theory. It stems from the tension between the discrete, combinatorial nature of free groups and the continuous, analytic nature of differential equations. This phenomenon echoes the well-known fact in Lie theory that free groups cannot be densely embedded in finite-dimensional Lie groups unless they are discrete.

Remark 7

(Other obstructed subcategories). Beyond holonomic D-modules, several other geometrically constrained subcategories exhibit similar obstructions to cocompleteness:

- Regular holonomic D-modules: These satisfy additional regularity conditions along the singular support. The constraints on their monodromy and Stokes data prevent the existence of free group objects with the required universal properties.

- D-modules with prescribed growth conditions (e.g., tempered or algebraic D-modules): The growth constraints at infinity impose analytic limitations that conflict with the algebraic freedom needed for free group constructions.

- Arithmetic D-modules over p-adic fields: The p-adic differential constraints and convergence conditions introduce obstructions analogous to those in the holonomic case.

- D-modules on singular varieties: When the base variety is singular, the category of D-modules may fail to be regular or may lack a free group functor due to the nontrivial geometry of the singular locus.

In each case, the obstruction stems from the tension between the algebraic/combinatorial nature of free groups and the analytic/geometric constraints imposed by the differential structure.

Corollary 3.

The category of holonomic D-module groups—internal group objects in the category of holonomic D-modules—is not cocomplete.

Proof.

Holonomic D-modules are characterized by finite-dimensional solution spaces and satisfy particularly strong structural constraints [41]. The argument in Proposition 3 applies with even greater force here, since the finite-dimensionality of solution spaces directly contradicts the requirement that free groups contain infinite discrete subgroups. Moreover, the constraints on characteristic varieties for holonomic D-modules prevent the existence of free group objects with the necessary universal properties. □

Example 3.

Consider the first Weyl algebra and the category of D-modules over . The free group on the simple D-module (with the standard -action) cannot exist in . Any candidate for such a free group would have to contain solutions to arbitrary differential equations, violating the finite-dimensional constraints inherent in the theory of D-modules.

Theorem 6.

Let be a geometrically enriched category of D-modules (e.g., holonomic, regular holonomic, or D-modules with prescribed growth conditions). The following are equivalent:

- 1.

- is cocomplete;

- 2.

- The free group functor exists;

- 3.

- admits no nontrivial differential algebraic constraints that prevent the embedding of free groups.

Moreover, when these conditions fail, the failure is detected by the impossibility of constructing free groups on simple D-modules with nontrivial differential structure.

Proof.

The equivalence (1) ⇔ (2) follows directly from Theorem 4. For (2) ⇒ (3), we argue by contraposition: if has differential algebraic constraints that prevent free group embeddings, then the universal property of free groups cannot be satisfied. Finally, (3) ⇒ (2) follows from the fact that, in the absence of such constraints, the explicit construction of free groups via Theorem 5 can be carried out. The detection criterion follows from the proof of Proposition 3, which shows that the obstruction already arises at the level of simple D-modules. □

Remark 8.

The geometric obstructions identified in this section have profound implications for the development of homotopical algebra in categories of D-modules. They suggest that although model structures can often be transferred to categories of internal group objects, the resulting homotopy theories may exhibit pathological behavior in the presence of geometric constraints. This observation motivates the use of alternative frameworks, such as derived algebraic geometry or higher categorical methods, to handle such cases in a satisfactory manner.

6. Applications and Examples

The general theory developed in the preceding sections finds rich applications across various mathematical contexts where D-modules and internal group structures naturally arise. We now illustrate our results through several key examples that demonstrate both the scope and limitations of our completeness and cocompleteness transfer theorems.

Example 4

(Topological D-Module Groups). The category of topological D-module groups provides an important example where our cocompleteness theorem applies. Consider the category of topological D-modules, where objects are D-modules equipped with compatible topological structures and morphisms are continuous D-linear maps.

To apply Theorem 4, we first verify that is regular and cocomplete with a free group functor . The regularity condition is typically satisfied when the underlying topological spaces are sufficiently well-behaved—for instance, when they are compactly generated weak Hausdorff spaces, where the necessary limits and colimits exist and are well-behaved.

The existence of the free group functor follows from the adjoint functor theorem when is locally presentable. Under these conditions, Theorem 4 ensures that is cocomplete. The resulting colimits are computed by first forming the colimit in and then applying the free group construction with appropriate relations encoding the group axioms, as detailed in the constructive proof of Theorem 4.

This example is particularly significant in applications to continuous representation theory and topological quantum field theories, where the interplay between topological structures and differential operators plays a crucial role in understanding symmetry properties and conservation laws.

Example 5

(Cocompleteness for Sheaves of -Modules). Let X be a smooth algebraic variety or a complex manifold, and let denote the sheaf of differential operators on X. The category of left -modules is a Grothendieck category, hence it is complete, cocomplete, and regular. Moreover, because is locally presentable, the forgetful functor admits a left adjoint F by the adjoint functor theorem. Therefore, by Theorem 3 (or Theorem 4), the category is cocomplete. This result is significant in geometric representation theory and the study of symmetry groups of differential equations on X.

A constructive description of colimits in can be obtained by working locally on open affine covers of X and gluing the colimits constructed in the affine case. Since the free group functor commutes with restriction to open subsets, the gluing is well-defined and yields a sheaf of internal group objects.

The regularity of follows from the fact that the category of sheaves on a topological space is a Grothendieck topos, while cocompleteness is inherited from the cocompleteness of D-modules and the sheaf condition. The free group functor is constructed sectionwise: for a sheaf , we define by setting for each open , where denotes the free group on the D-module . The sheaf condition is preserved because the free group construction commutes with limits.

This example has profound implications in algebraic geometry and number theory, where sheaves of differential algebraic groups arise naturally in the study of moduli spaces and arithmetic geometry, providing a bridge between local and global geometric structures.

Let X be a smooth algebraic variety or a complex manifold, and let denote the sheaf of differential operators on X. The category of left -modules is abelian and cocomplete, with colimits computed locally. Since is a Grothendieck category, it is regular and locally presentable. The free group functor exists by the adjoint functor theorem. Therefore, by Theorem 7, is cocomplete. This result is significant in geometric representation theory and the study of symmetry groups of differential equations on X.

Example 6

(Holonomic D-Module Groups). The subcategory of holonomic D-module groups provides a compelling illustration of the geometric obstructions discussed in Section 5. Holonomic D-modules are characterized by their finite-dimensional characteristic varieties and satisfy particularly strong finiteness conditions [41].

While the category of holonomic D-module groups is complete—as it forms a reflective subcategory of closed under limits—it fails to be cocomplete in general due to intrinsic geometric constraints. The obstruction to cocompleteness stems from characteristic variety constraints inherent in holonomic D-modules.

To understand this obstruction precisely, suppose M is a holonomic D-module with a nontrivial differential structure. If the free group existed, it would necessarily contain sub-objects isomorphic to free groups on multiple generators. However, such free groups would have characteristic varieties of dimension exceeding the maximum allowed by holonomicity, which requires the characteristic variety to be at most the dimension of the base space. This dimensional incompatibility violates the fundamental defining property of holonomic D-modules and thus prevents the existence of the free group functor in the holonomic setting.

This example demonstrates the sharpness of our results: while completeness is inherited by all subcategories closed under limits, cocompleteness requires specific compatibility conditions between the free group construction and the additional geometric structures. The failure of cocompleteness in the holonomic case highlights the delicate balance between algebraic constructions and geometric constraints in the theory of D-modules.

Remark 9

(Challenges in transferring model structures to ). Transferring a model structure from to along the adjunction faces several challenges:

- 1.

- Geometric obstructions: In subcategories like holonomic D-modules, the lack of free group objects prevents the existence of a left adjoint F, making the standard model structure transfer inapplicable.

- 2.

- Regularity and factorizations: Even when F exists, the transferred model structure requires that be cofibrantly generated and that U preserves filtered colimits and cofibrations. These conditions may fail in differential geometric settings due to analytic constraints.

- 3.

- Compatibility with differential structure: The weak equivalences in (e.g., quasi-isomorphisms) must be preserved by U and reflected by F, which is nontrivial when the group structure interacts with the differential operators.

- 4.

- Homotopical nontriviality: The geometric obstructions identified in Section 5 may lead to pathological homotopy categories, such as trivial homotopy groups or unexpected higher homotopical structure.

Overcoming these challenges likely requires techniques from derived algebraic geometry or ∞-categorical methods, where the constraints can be incorporated into the homotopical framework.

7. Internal Hom-Objects and Duality

The existence of internal hom-objects in categories of internal group objects represents a fundamental aspect of their categorical structure, enabling the development of rich duality theories that bridge algebraic and geometric perspectives. In the context of D-modules, these constructions lead to powerful applications in representation theory and beyond.

Theorem 7.

Let be a locally Cartesian closed category, and let be internal group objects. Then there exists an internal hom-object characterized by the natural isomorphism:

where 1 denotes the terminal object in .

Proof.

We construct explicitly as an equalizer in , leveraging the locally Cartesian closed structure. Let and be internal group objects.

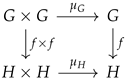

Consider the following diagram:

where all objects are exponentials in the locally Cartesian closed category , and the parallel arrows enforce the conditions for group homomorphisms.

More precisely, we define as the equalizer of the morphisms that encode the following conditions for triples :

First, the morphism must preserve the group multiplication, meaning the diagram

commutes. This ensures that for all generalized elements of G.

Second, f must preserve the unit element, requiring the commutativity of

This guarantees that f maps the identity element of G to the identity element of H.

Third, f must respect the inversion operation, as expressed by the commutative diagram

ensuring that for all generalized elements x of G.

The components and serve to enforce coherence with the group axioms. Specifically, ensures compatibility with associativity constraints, while verifies the coherence of unit and inverse operations under the homomorphism.

To establish the universal property, we apply the Yoneda lemma and the Cartesian closed structure of . For any test object , we obtain natural isomorphisms:

The final isomorphism utilizes the Cartesian closed structure and the correspondence between group objects in and parametrized group homomorphisms. Specializing to yields the desired natural isomorphism, completing the proof. □

Remark 10

(Conditions for to be locally Cartesian closed). For the internal hom construction in Theorem 7, we require to be locally Cartesian closed (LCCC). This is a strong condition that holds in the following settings:

- 1.

- When is a Grothendieck topos, such as the category of sheaves of D-modules on a topological space or scheme. In a topos, all finite limits exist and are preserved by the exponential functor.

- 1.

- When D is a finite-dimensional algebra over a field and is equivalent to the category of representations of a finite-dimensional algebra, it is locally finitely presentable and Cartesian closed, hence LCCC.

- 1.

- More generally, if is a locally presentable closed symmetric monoidal category, then it is LCCC. This is the case when D is a dualizable object in the category of R-algebras and the monoidal structure is given by tensor product over R.

In practice, for the sheaf-theoretic D-modules on a smooth variety X, the category is a Grothendieck category and hence a topos after sheafification, satisfying the LCCC condition.

- Applicability of Theorem 7 to General Polynomial Rings D

Theorem 7 does not depend on the specific form of the ring D of differential operators. It holds for any base category that is locally Cartesian closed (LCCC). The conditions listed in Remark 10 are sufficient but not necessary. In particular, if D is a finite-dimensional algebra over a field, then is equivalent to the category of representations of a finite-dimensional algebra, which is LCCC. More generally, if is a locally presentable closed symmetric monoidal category, then it is LCCC. This includes many cases of interest beyond the polynomial differential operators considered in this paper.

For categories that are not LCCC (such as for a general scheme X), the internal hom-object may not exist in itself, but it can often be constructed in a larger category, such as the category of presheaves on (see the reformulation below). This does not affect the validity of the duality results, as the Yoneda embedding preserves the relevant structure.

- Example: Sheaves of -modules on a scheme or complex manifold.

Let X be a smooth algebraic variety or a complex manifold, and let denote the sheaf of differential operators on X. The category of left -modules is abelian and cocomplete, with colimits computed locally. Since is a Grothendieck category, it is regular and locally presentable. The free group functor exists by the adjoint functor theorem. Therefore, by Theorem 3, is cocomplete. This result is significant in geometric representation theory and the study of symmetry groups of differential equations on X.

Remark 11.

The internal hom-object constructed in Theorem 7 carries rich structure beyond being merely an object of . When , it naturally acquires a group object structure itself, forming an internal automorphism group when appropriate finiteness conditions are satisfied. This additional structure plays a crucial role in applications to representation theory and duality, as illustrated in the following corollary.

Choice-Free Reformulation in Presheaf Categories

To address concerns regarding the Axiom of Choice and the potential lack of Cartesian closedness in , we observe that the category of presheaves on is a Cartesian closed topos and is locally presentable. Moreover, the Yoneda embedding preserves all limits and is fully faithful.

Given , we can consider their images under y and form the internal hom-object in using the same equalizer construction as in Remark 10. Because is a topos, this construction is entirely constructive and does not rely on the Axiom of Choice.

The key observation is that for any test object , we have a natural isomorphism

where denotes the internal hom-object in if it exists, or otherwise can be defined as the representing object of the functor . This shows that the presheaf represents the functor of group homomorphisms, even when the internal hom does not exist in itself. Thus, all duality results (including Corollary 4) can be reformulated and proved choice-freely in the presheaf topos.

Corollary 4

(Tannaka Duality for D-Module Groups). When is a topos (in particular, when working with sheaves of D-modules), for any , there is an equivalence of categories:

where is the category of representations of G and is the internal Hopf algebra of G, with being the affine line object in .

Proof.

The proof follows the standard Tannaka reconstruction argument, adapted to the D-module context using the internal hom construction of Theorem 7.

We first establish that carries a natural Hopf algebra structure induced by the group structure of G. The comultiplication arises from applying to the multiplication map , yielding

The counit is induced by the unit , while the antipode comes from the inverse . Verification of the Hopf algebra axioms follows systematically from the group axioms for G and the naturality of the internal hom construction.

The reconstruction of G from its representation category then follows from the Barr–Beck theorem. The forgetful functor is comonadic, with comonad given by . Since is conservative and preserves equalizers, and the comonad is effectively given by tensoring with , we obtain the desired equivalence . □

Example 7

(D-Module Group Schemes). When is the category of D-modules on a smooth algebraic variety X, the internal hom objects of Theorem 7 correspond to group schemes in the category of D-modules. These are fundamental objects in the study of differential algebraic groups and arise naturally in the analysis of symmetry groups of differential equations. For instance, the internal hom object , where is the additive group scheme, represents the Lie algebra of G in the context of D-modules, providing a powerful tool for studying infinitesimal symmetries.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This work establishes a comprehensive categorical framework for transferring completeness and cocompleteness properties to categories of internal group objects in D-modules, revealing profound connections between categorical algebra and differential geometry. Our main results demonstrate several fundamental principles:

- The completeness of follows unconditionally from the completeness of the base category , with limits created by the forgetful functor . This underscores the robust nature of limit preservation under the formation of internal group objects.

- Cocompleteness requires more delicate conditions: specifically, must be regular and cocomplete, and must admit a free group functor left adjoint to the forgetful functor. This asymmetry highlights the constructive nature of colimits in categories of algebraic structures.

- Geometric obstructions prevent cocompleteness in differentially constrained subcategories, such as holonomic D-modules, where characteristic variety constraints impose fundamental limitations on free group objects. These reveal the deep interplay between algebraic constructions and geometric constraints.

- We provide explicit constructions for limits and colimits via free group functors, with colimits realized through coequalizers of relations induced by group axioms. These methods establish existence while providing practical tools for concrete applications.

Our framework unifies classical category theory with the geometric theory of D-modules, resolving long-standing questions about exactness transfer while providing new structural insights. The explicit nature of our constructions makes them particularly suitable for applications in geometric representation theory, mathematical physics, and homotopical algebra.

Looking forward, several promising directions emerge:

- Higher categorical generalizations: Extending our work to n-groupoids in -categories of D-modules promises new connections between higher category theory and differential geometry, particularly within derived algebraic geometry.

- Homotopical enhancements: Establishing model structures on would enable the application of homotopical methods, including transferring model structures along and developing Bousfield localizations with respect to natural homology theories.

- Representation-theoretic extensions: Developing internal character theory for D-module group objects would provide powerful tools, including character varieties for differential algebraic groups and enhanced Riemann–Hilbert correspondences.

- Applications to geometric Langlands: Our results apply naturally to the geometric Langlands program, particularly in understanding categorical properties of automorphic D-modules and their relationship with Galois representations.

- Quantum symmetry detection: The framework may be applied to quantum symmetries in mathematical physics, providing tools for analyzing symmetry breaking phenomena in topological and conformal field theories.

- Computational aspects: Developing computational methods for working with limits and colimits in would make these theoretical results accessible for concrete applications.

- Connections to arithmetic geometry: Extending our results to arithmetic D-modules and p-adic differential equations would open new avenues in number theory. The primary challenges include the following:

- p-adic convergence issues: The free group construction requires infinite series and completions, which are delicate in p-adic settings due to non-archimedean topology.

- Regularity in arithmetic categories: Categories of arithmetic D-modules (e.g., over or ) may fail to be regular or may lack effective equivalence relations, hindering colimit constructions.

- Frobenius structures: In positive characteristic, the Frobenius operator introduces additional constraints that could obstruct the existence of free group functors.

- Comparison with ℓ-adic sheaves: Bridging D-module techniques with ℓ-adic sheaves in the p-adic context requires sophisticated six-functor formalism and compatibility with Galois actions.

Despite these hurdles, recent advances in p-adic Hodge theory and prismatic cohomology provide promising tools for such extensions.

The framework established here not only resolves fundamental questions in categorical algebra but also provides a foundation for future investigations across multiple mathematical domains. The interplay between categorical structures and geometric constraints suggests rich connections waiting to be explored, promising new insights into the deep relationships between algebra, geometry, and category theory.

Generality and Extensions

The framework developed in this paper is comprehensive in the following precise sense:

- The completeness transfer (Theorem 2) holds for any complete category with finite products. No additional structure is required.

- The cocompleteness transfer (Theorem 3) holds for any regular, cocomplete category that admits a free group functor left adjoint to the forgetful functor.

- The internal hom construction (Remark 10) holds for any locally Cartesian closed category with finite limits.

- The geometric obstruction results (Section 5) apply to any geometrically enriched subcategory of where the free group functor fails to exist due to analytic constraints.

These conditions are satisfied by a wide variety of categories beyond , including the following:

- Categories of sheaves of modules over a ringed space (e.g., ).

- Comma categories built from abelian categories, as mentioned in the Introduction.

- Many non-abelian categories such as topological groups or simplicial groups, under appropriate modifications (see Section 5).

- Presheaf categories, which provide a choice-free environment for internal hom constructions (Section 7).

Therefore, the term comprehensive is justified: our results provide a unified categorical framework for studying internal group objects in a broad class of base categories, encompassing both algebraic and geometric contexts, and addressing both completeness and cocompleteness transfer, along with duality and obstruction theory.

Remark 12.

The methods developed in this paper extend naturally beyond D-modules to other categorical contexts where internal group objects play significant roles. The transfer theorems for completeness and cocompleteness, along with the explicit constructions provided, may be adapted to categories of sheaves, stacks, and other geometrically enriched categories, suggesting broad applicability beyond the specific context of D-modules.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-G.T.; methodology, J.-G.T. and M.L.; software, M.L. and H.L.; validation, M.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, H.L.; resources, N.M.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-G.T., M.L., H.L., Q.-G.C. and J.-Y.P.; writing—review and editing, J.-G.T., M.L., H.L., Q.-G.C. and J.-Y.P.; visualization, N.M.; supervision, J.-G.T.; project administration, J.-G.T.; funding acquisition, J.-G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the University Key Project of Natural Science of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant No. XJEDU2019I024).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

References

- Kashiwara, M.; Schapira, P. Sheaves on Manifolds; Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; Volume 292. [Google Scholar]

- Artin, M.; Grothendieck, A.; Verdier, J.L. Théorie des Topos et Cohomologie étale des Schémas; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1972; Volumes 269, 270 and 305. [Google Scholar]

- Grothendieck, A. Sur quelques points d’algèbre homologique. Tôhoku Math. J. 1957, 9, 119–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.S. Cohomology of Groups; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 87. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalley, C.; Eilenberg, S. Cohomology theory of Lie groups and Lie algebras. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1948, 63, 85–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toën, B.; Vezzosi, G. Homotopical algebraic geometry I: Topos theory. Adv. Math. 2005, 193, 257–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adámek, J.; Rosický, J. Locally Presentable and Accessible Categories; London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; Volume 189. [Google Scholar]

- Borceux, F. Handbook of Categorical Algebra; Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; Volumes 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Lane, S. Categories for the Working Mathematician; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1971; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, G.W. Elements of Homotopy Theory; Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 61. [Google Scholar]

- Grothendieck, A.; Dieudonné, J. Éléments de géométrie algébrique. I. Le langage des schémas. Publ. Math. IHES 1960, 4, 5–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, P.; Zisman, M. Calculus of Fractions and Homotopy Theory; Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 35; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, D.M. Adjoint functors. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 1958, 87, 294–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillen, D.G. Homotopical Algebra; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1967; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, G.M. Basic Concepts of Enriched Category Theory; London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Leinster, T. Higher Operads, Higher Categories; London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; Volume 298. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.A. Functor categories. In Group Representation Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1973; pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Serre, J.-P. Cohomologie Galosienne; Cours au Collège de France, 1962–1963, Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1964; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Caenepeel, S.; van Oystaeyen, F. Brauer Groups and the Cohomology of Graded Rings; Monographs and Textbooks in Pure and Applied Mathematics; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 121, ISBN 0-8247-7911-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goerss, P.; Jardine, J.F. Simplicial Homotopy Theory; Progress in Mathematics; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 1999; Volume 174. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey, M. Model Categories; Mathematical Surveys and Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1999; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Riehl, E. Categorical Homotopy Theory; New Mathematical Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, J. Higher Topos Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie, J. Higher Algebra. 2017. Preprint. Available online: https://www.math.ias.edu/~lurie/papers/HA.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mac Lane, S.; Moerdijk, I. Sheaves in Geometry and Logic: A First Introduction to Topos Theory; Universitext; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.-T. Cohomology Theory; Markham Publishing Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Neisendorfer, J. Algebraic Methods in Unstable Homotopy Theory; New Mathematical Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Elmendorf, A.D.; Kříž, I.; Mandell, M.A.; May, J.P. Rings, Modules, and Algebras in Stable Homotopy Theory; Mathematical Surveys and Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1997; Volume 47. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey, M. Monoidal model categories. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2003, 355, 3481–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, L.; Williamson, J. The left localization principle, completions, and cofree G-spectra. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2020, 224, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, C. A model for the homotopy theory of homotopy theory. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2001, 353, 973–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.P. The Geometry of Iterated Loop Spaces; Lectures Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1972; Volume 271. [Google Scholar]

- Waldhausen, F. Algebraic K-theory of spaces. In Algebraic and Geometric Topology; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; Volume 1126, pp. 318–419. [Google Scholar]

- Aghapournahr, M.; Bahmanpour, K. A characterization of cominimax and weakly cofinite modules. Commun. Algebra 2020, 48, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prytuła, T. Graphical complexes of groups. J. Group Theory 2022, 25, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M. Stable Homotopy; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1970; Volume 165, ISBN 978-3-540-05392-3. [Google Scholar]

- May, J.P. Simplicial Objects in Algebraic Topology; Van Nostrand Mathematical Studies, No. 11; D. Van Nostrand Co., Inc.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Switzer, R.M. Algebraic Topology—Homotopy and Homology; Reprint of the 1975 edition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quillen, D.G. Rational homotopy theory. Ann. Math. 1969, 90, 205–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel, A.; Grivel, P.-P.; Kaup, B.; Haefliger, A.; Malgrange, F.; Ehlers, F. Algebraic D-Modules; Perspectives in Mathematics; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 2, xii, 355p, ISBN 0-12-117740-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwara, M. D-Modules and Microlocal Calculus; Translations of Mathematical Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2003; Volume 217. [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan, V.S. Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Their Representations; Prentice-Hall Series in Modern Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; pp. xiii+430. ISBN 0135357322. [Google Scholar]