TFGCRN: Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Incomplete Traffic Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

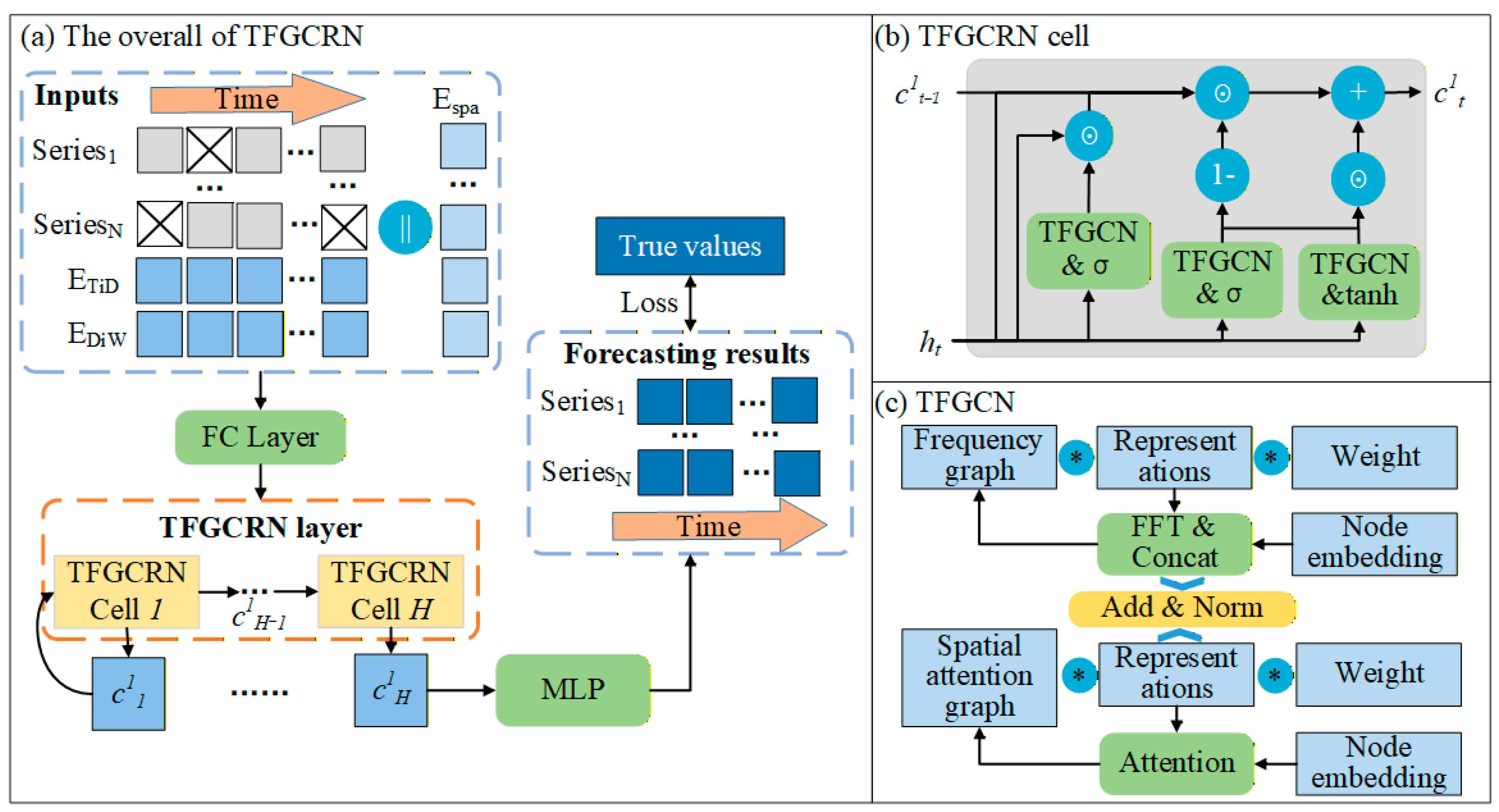

- To alleviate the adverse effects caused by missing values, this paper proposes the Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network (TFGCRN), which aims to dynamically reconstruct spatial–temporal dependencies from both global and local perspectives, thereby achieving improved performance in incomplete traffic forecasting.

- This paper proposes the Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Network (TFGCN) by leveraging the advantages of frequency and temporal information in capturing global and local spatial relationships. The TFGCN is used to replace all fully connected layers within the GRU, thereby recursively modeling spatial–temporal dependencies.

- Experiments on four real-world datasets demonstrate that TFGCRN outperforms ten mainstream baselines and adapts well to different missing rates, verifying its superiority and robustness.

2. Related Works

2.1. Classic Traffic Forecasting Model

2.2. Two-Stage Incomplete Traffic Forecasting Model

2.3. End-to-End Incomplete Traffic Forecasting Model

3. Methods

3.1. Preliminaries

3.2. Overall Framework

3.3. Spatial–Temporal Embedding

3.4. Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolution Network

3.5. TFGCRN Cell

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

- METR-LA: The dataset records traffic speeds measured by loop detectors installed throughout the Los Angeles County road network. It includes observations from 207 sensors collected between 1 March and 30 June 2012. Each sensor provides readings every five minutes, resulting in a total of 34,272 time points.

- PEMS-BAY: The dataset consists of traffic speed records obtained from the California Transportation Agencies (CalTrans) Performance Measurement System (PeMS). It includes measurements from 325 sensors collected between 1 January and 31 May 2017. Each time series was sampled every five minutes, resulting in a total of 52,116 time points.

- PEMS04: The dataset includes traffic flow information sourced from the CalTrans Performance Measurement System (PeMS). It comprises data from 307 sensors collected between 1 January and 28 February 2018. Each series is recorded at five-minute intervals, yielding a total of 16,992 time points.

- PEMS08: The dataset contains traffic flow data obtained from the CalTrans Performance Measurement System (PeMS). It includes observations from 170 sensors recorded between 1 July and 31 August 2018. Each time series was sampled every five minutes, producing a total of 17,833 time points.

4.2. Experimental Setup

- PatchTST + SAITS: The former employs patch encoding and a transformer to perform traffic time series forecasting, while the latter uses an attention mechanism to restore missing values in the data.

- DCRNN + GPT4TS: The former combines GCN and GRU to achieve traffic forecasting, while the latter uses Patch and GPT-2 to restore missing values.

- FourierGNN + GATGPT: The former replaces graph convolution with Fourier computation to perform traffic forecasting, while the latter combines GAT and GPT-2 to restore missing values.

- MTGNN + GRIN: The former combines graph learning and temporal convolutional networks to achieve traffic forecasting, while the latter Employs Graph Convolutional Networks for data recovery.

- LGnet: It combines memory unit components to enhance the performance of recurrent neural networks in incomplete traffic forecasting.

- GC-VRNN: It integrates multi-space GCN with conditional variational RNN to achieve incomplete traffic forecasting.

- RIHGCN: It combines graph convolutions constructed from geographic distances and historical similarity with a bidirectional recurrent imputation mechanism and LSTM to enable incomplete traffic forecasting.

- GSTAE: It proposes a graph-based spatial–temporal autoencoder that follows an encoder–decoder structure for incomplete traffic forecasting.

- BiTGraph: It employs the biased temporal convolution graph neural network to effectively achieve incomplete traffic forecasting.

- GinAR+: It integrates interpolation attention, adaptive graph convolution, and simple recurrent units to achieve incomplete traffic forecasting.

- In this paper, following mainstream benchmarks [77], all datasets are divided proportionally into training sets, validation sets, and test sets.

- Following mainstream-related works [78], both the historical observation length and the future forecasting length of the model are set to 12, and the evaluation metric is the average performance over the 12-step forecasting.

- This paper is primarily conducted under the classic random-missing setting [79]. Since the distribution of missing values is not fixed, the experimental results can better demonstrate the robustness of the model. The missing rates are set to 25%, 50%, and 75%. All missing values are uniformly set to zero using a random masking approach.

- Currently, most mainstream baselines conduct experiments directly on the datasets used in this paper without additional data cleaning. To ensure a fair comparison, and considering that real-world data naturally contain missing values, we did not perform extra data cleaning so as to better evaluate the model’s performance in realistic settings.

- To ensure stability and robustness, five different random seeds are used for each missing rate, and the final results are reported as the average of the repeated experiments. All models were tested in five repeated trials to ensure their stability and the reproducibility of the experimental results.

4.3. Main Results

- The forecasting performance of two-stage models is significantly lower than that of end-to-end models, which verifies the value of the end-to-end forecasting framework in the field of incomplete traffic forecasting. The main reason is that two-stage models inevitably suffer from error accumulation, which in turn limits the full exploitation of spatial–temporal dependencies in forecasting models.

- Graph-based end-to-end models achieve better experimental results mainly because graph convolution can effectively model the spatial relationships among different time series, thereby enhancing the modeling of spatiotemporal dependencies and ensuring accurate incomplete traffic forecasting.

- The proposed TFGCRN achieves the best experimental results across all datasets. First, the spatial–temporal embedding mitigates the adverse effects of missing values by introducing additional information. Second, TFGCN leverages both the frequency graph and spatial attention graph to ensure accurate modeling of spatial relationships from global and local perspectives. Finally, by integrating TFGCN into the GRU, the model realizes recursive modeling of spatial–temporal dependencies. Therefore, TFGCRN demonstrates excellent performance in incomplete traffic forecasting tasks.

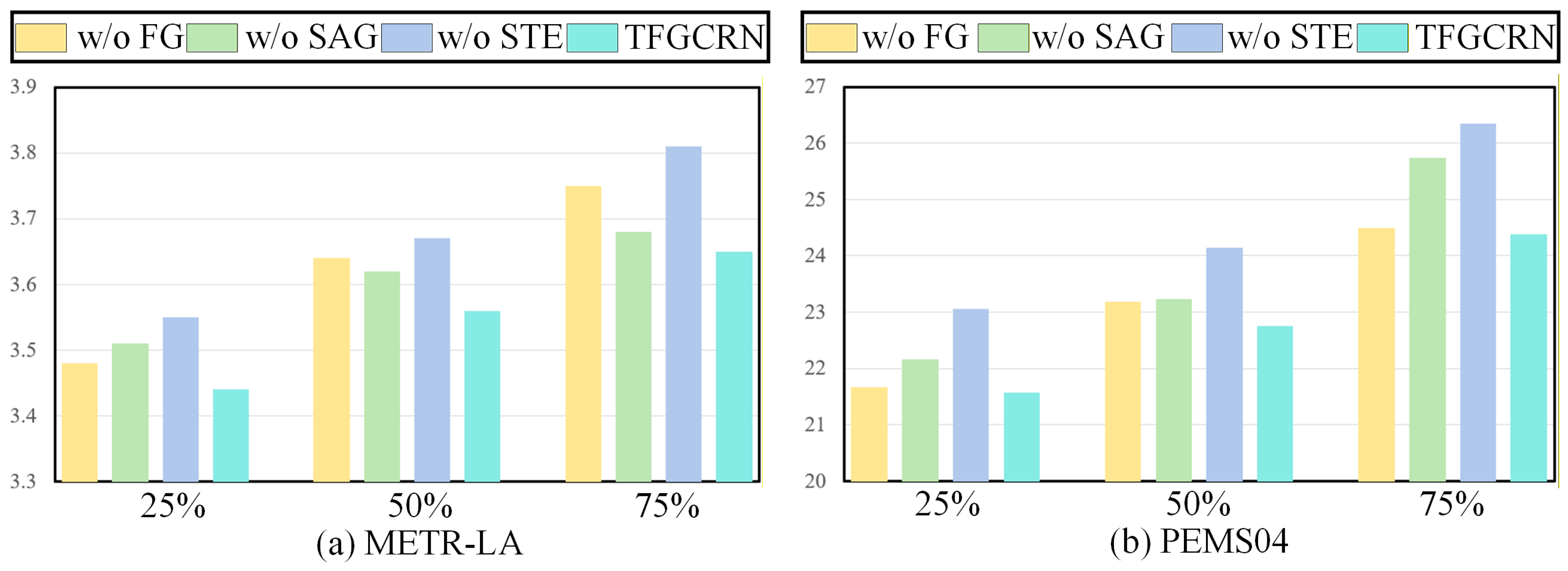

4.4. Ablation Experiment

- The frequency graph has a significant impact when the missing rate is high. This is mainly because, when the missing rate is large, global information helps the model better analyze spatial–temporal dependencies.

- The spatial attention graph has a significant impact when the missing rate is low. This is mainly because, when the missing rate is small, the model can better model spatial dependencies by leveraging local information.

- The spatial–temporal embedding is beneficial to the experimental results under different missing rates. This indirectly confirms that additional spatiotemporal knowledge helps prevent the model from forcing the use of zero values to mine spatial–temporal information, thereby ensuring forecasting accuracy.

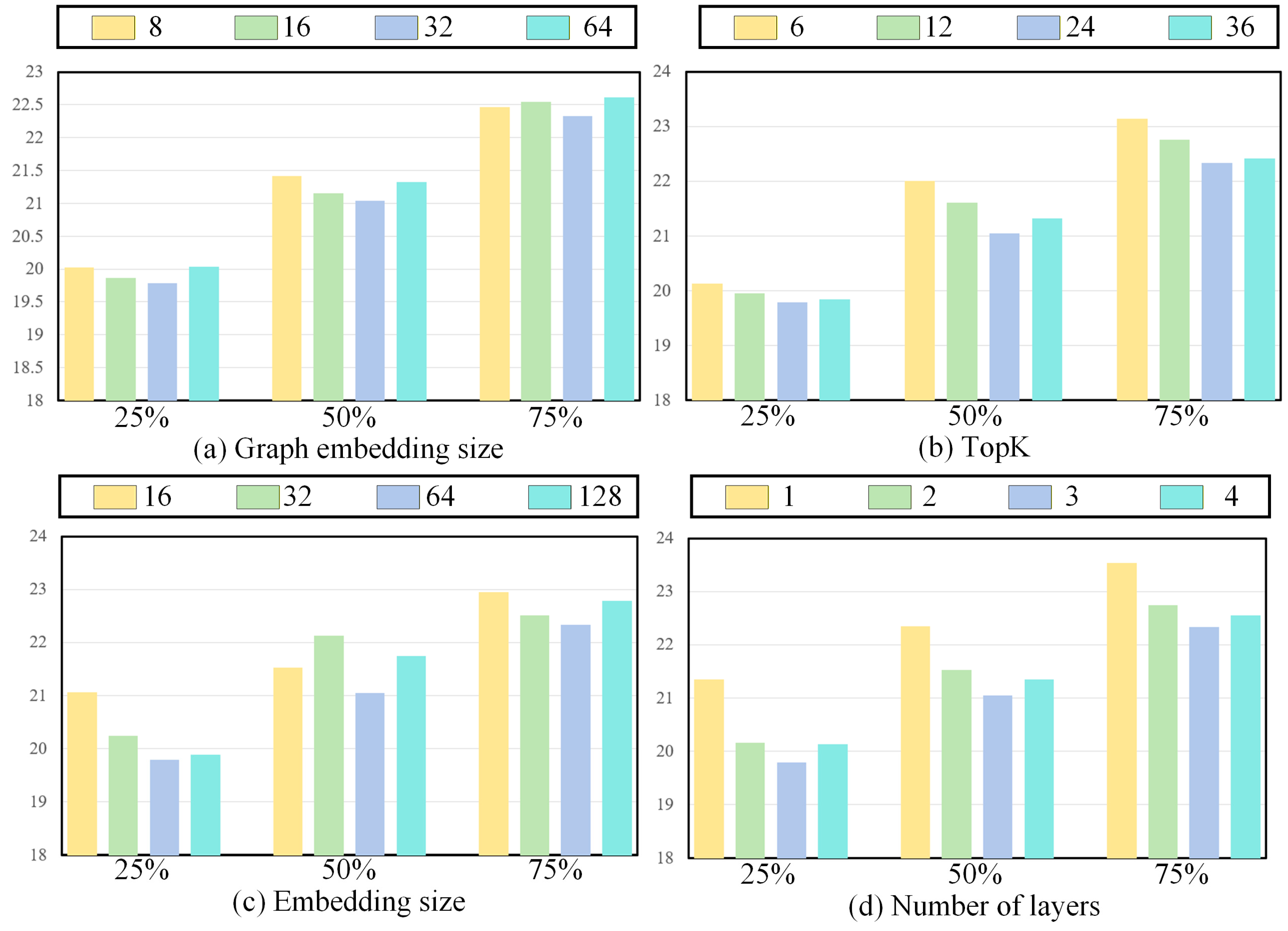

4.5. Hyperparameter Analysis

- The impact of the graph embedding size on the experimental results is minimal, primarily because TGCRN can generate relatively accurate graph structures with a small number of parameters, ensuring the accuracy of spatial relationships.

- The number of TopK can be increased appropriately, as it allows for a more comprehensive reflection of spatial relationships.

- The embedding size is an important hyperparameter and should not be too large. A larger embedding size may lead to overfitting, which in turn affects forecasting accuracy.

- The number of layers plays a crucial role in forecasting performance. Too few layers may fail to adequately capture and analyze data characteristics, while too many layers can lead to overfitting and other issues.

4.6. Component Replacement Experiment

- Replacing the spatial attention graph with multi-head attention or graph attention both leads to a clear decline in prediction performance, which demonstrates the stability and effectiveness of incorporating node embeddings, node identity information, and attention-based graph structures.

- Replacing the FFN with DTW does not significantly improve prediction performance, mainly because DTW focuses on local pattern alignment, whereas FFT emphasizes global analysis. In the context of incomplete traffic time series, modeling spatial relationships from a global perspective is more crucial.

- LSTM performs worse than GRU, mainly because a lighter GRU structure can better avoid the noise introduced by missing values along the temporal dimension, thereby improving prediction performance.

- The strategy of fusing graph structures by stacking them before layer normalization yields better prediction results, mainly because this approach preserves the differences between the graph structures and thus provides more comprehensive spatial information.

- Using two separate TFGCNs to model and leads to better experimental results, mainly because applying graph convolutions with different parameters to these two distinct representations helps capture more complete spatial relationships.

- The performance of masked attention is not satisfactory. On the one hand, removing spatiotemporal embeddings leads to a significant drop in prediction accuracy; on the other hand, masking spatial relationships may cause the model to overlook important information propagation pathways, thereby limiting its predictive performance.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| STGNN | Spatial–Temporal Graph Neural Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

References

- Yu, F.; Mi, X.; Yu, C.; Jiang, Y. Distributed Traffic Signal Control Model for Accurate Policy Learning Under Dynamic Traffic Flow: A Graph Forecast-State Vector Driven Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 13573–13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Men, Q. Performance Analysis of Switch Buffer Management Policy for Mixed-Critical Traffic in Time-Sensitive Networks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Yang, Y.-X.; Li, Y.-F.; Yu, C.-Q. Hourly traffic flow forecasting using a new hybrid modelling method. J. Cent. South Univ. 2022, 29, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, P.; Liu, X.; Yu, C.; Yan, G.; Xiang, Q.; Mi, X. A new ensemble deep graph reinforcement learning network for spatio-temporal traffic volume forecasting in a freeway network. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 123, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Kuldeep, S.A.; Rafa, S.J.; Fazal, J.; Hoque, M.; Liu, G.; Gandomi, A.H. Enhancement of traffic forecasting through graph neural network-based information fusion techniques. Inf. Fusion 2024, 110, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, Q.; Lu, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, N. A FIG-IWOA-BiGRU Model for Bus Passenger Flow Fluctuation Trend and Spatial Prediction. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.-C.; Wu, K.-T.; Lin, H.-T.C.; Lin, S. MixModel: A Hybrid TimesNet–Informer Architecture with 11-Dimensional Time Features for Enhanced Traffic Flow Forecasting. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xian, K.; Wen, H.; Bai, S.; Xu, H.; Yu, Y. PathGen-LLM: A Large Language Model for Dynamic Path Generation in Complex Transportation Networks. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Qian, T.; Sun, T.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y. Spatial-temporal large models: A super hub linking multiple scientific areas with artificial intelligence. Innovation 2025, 6, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Cao, X.; Jensen, C.S. Decoupled dynamic spatial-temporal graph neural network for traffic forecasting. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2022, 15, 2733–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, H. Charging strategies optimization for lithium-ion battery: Heterogeneous ensemble surrogate model-assisted advanced multi-objective optimization algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 342, 120170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; An, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, F. Selective Learning for Deep Time Series Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.25207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y. Pre-training Enhanced Spatial-temporal Graph Neural Network for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 1567–1577. [Google Scholar]

- Chengqing, Y.; Guangxi, Y.; Chengming, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xiwei, M. A multi-factor driven spatiotemporal wind power prediction model based on ensemble deep graph attention reinforcement learning networks. Energy 2023, 263, 126034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, S.; Gopal, D.; Logeshwaran, J.; Ramya, N.; Salau, A.O. Multi-Model Traffic Forecasting in Smart Cities using Graph Neural Networks and Transformer-based Multi-Source Visual Fusion for Intelligent Transportation Management. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2024, 22, 518–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Meng, L.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Lan, L.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. From Concrete to Abstract: Multi-View Clustering on Relational Knowledge. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 9043–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Shao, Z.; Sun, T.; Wu, L.; Xu, Y. DSformer: A Double Sampling Transformer for Multivariate Time Series Long-term Prediction. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 3062–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Afandizadeh, S.; Abdolahi, S.; Mirzahossein, H. Deep learning algorithms for traffic forecasting: A comprehensive review and comparison with classical ones. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024, 9981657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yan, G.; Yu, C.; Mi, X. Attention mechanism is useful in spatio-temporal wind speed prediction: Evidence from China. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Yi, S.; Yuan, J.; Xiao, Z.; Luo, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M. COOL: A Conjoint Perspective on Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Network for Traffic Forecasting. Inf. Fusion 2024, 107, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alghayadh, F.Y.; Ahanger, T.A.; Soni, M.; Viriyasitavat, W.; Berdieva, U.; Byeon, H. Deep learning model for efficient traffic forecasting in intelligent transportation systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 14673–14686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Suo, Q.; Jia, X.; Zhang, A.; Su, L. Heterogeneous Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolution Network for Traffic Forecasting with Missing Values. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 41st International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 July 2021; pp. 707–717. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Jiang, R.; Du, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, X.; Tsang, I.W. Disentangling Structured Components: Towards Adaptive, Interpretable and Scalable Time Series Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 3783–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.; Raghuveer, A.; Saket, R.; Nandy, J.; Ravindran, B. Multi-variate time series forecasting on variable subsets. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Yu, C.; Liu, X.; Yan, G.; Yu, F.; Shang, P. A dynamic ensemble deep deterministic policy gradient recursive network for spatiotemporal traffic speed forecasting in an urban road network. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 129, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarim, A.S.; Al-Malaise Al-Ghamdi, A.S.; Ragab, M. Ensemble Learning-based Algorithms for Traffic Flow Prediction in Smart Traffic Systems. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 13090–13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, W. Fusing visual quantified features for heterogeneous traffic flow prediction. Promet-Traffic Transp. 2024, 36, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Xu, W. Scalable prediction of heterogeneous traffic flow with enhanced non-periodic feature modeling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 294, 128847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Shen, G. A Comprehensive Survey on Traffic Missing Data Imputation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19252–19275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Samon, T.; Vellandurai, A.; Kumar, V. TA-SAITS: Time Aware-Self Attention based Imputation of Time Series algorithm for Partially Observable Multi-Variate Time Series. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Jacksonville, FL, USA, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 2228–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Niu, P.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. One fits all: Power general time series analysis by pretrained lm. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 43322–43355. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X. Frequency-aware generative models for multivariate time series imputation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 52595–52623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, A.; Marisca, I.; Alippi, C. Filling the G_ap_s: Multivariate Time Series Imputation by Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 25 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marisca, I.; Cini, A.; Alippi, C. Learning to reconstruct missing data from spatiotemporal graphs with sparse observations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 32069–32082. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.U.; Tadepalli, P.; Fern, A. Self-attention-based Diffusion Model for Time-series Imputation in Partial Blackout Scenarios. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 17564–17572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouedi, O.; Le, V.A.; Piamrat, K.; Ji, Y. Deep Learning on Network Traffic Prediction: Recent Advances, Analysis, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, F.; Shao, Z.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; An, Z.; Xu, Y. LightWeather: Harnessing Absolute Positional Encoding to Efficient and Scalable Global Weather Forecasting. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.09695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Xie, H.; Zuo, W.; Ren, J. Spatio-temporal filter adaptive network for video deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2482–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Lü, J.; Liu, K.; Zhu, A.; Snoussi, H.; Zhang, B. Synchronous Spatiotemporal Graph Transformer: A New Framework for Traffic Data Prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 10589–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, C.; Wu, H.; Duan, Z.; Yan, G. A new hybrid ensemble deep reinforcement learning model for wind speed short term forecasting. Energy 2020, 202, 117794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wei, W.; Xu, Y. Spatial-Temporal Identity: A Simple yet Effective Baseline for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–22 October 2022; pp. 4454–4458. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Dong, Z.; Jiang, R.; Deng, J.; Deng, J.; Chen, Q.; Song, X. Spatio-Temporal Adaptive Embedding Makes Vanilla Transformer SOTA for Traffic Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 4125–4129. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Sun, T.; Yao, D.; Xu, Y. MGSFformer: A Multi-Granularity Spatiotemporal Fusion Transformer for air quality prediction. Inf. Fusion 2025, 113, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Shen, G.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, Z.; Tang, T.; Kong, X.; Tolba, A.; Alfarraj, O. A transformer-based approach for traffic prediction with fusion spatiotemporal attention. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 329, 114466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ye, H.; Ying, Z.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W. Dynamic trend fusion module for traffic flow prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 174, 112979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qin, M.; He, Y.; Mi, X.; Yu, C. A new multi-data-driven spatiotemporal PM2.5 forecasting model based on an ensemble graph reinforcement learning convolutional network. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 101197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Meng, L.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X.; He, K. MGKsite: Multi-Modal Knowledge-Driven Site Selection via Intra and Inter-Modal Graph Fusion. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 1722–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A. Dynamic graph convolutional networks with Temporal representation learning for traffic flow prediction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Feng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, H. Hybrid spatial–temporal graph neural network for traffic forecasting. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 102978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Han, X.; Wen, S.; Tian, T. Spatiotemporal interactive learning dynamic adaptive graph convolutional network for traffic forecasting. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 311, 113115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rasouli, S.; Wong, M.; Feng, T.; Huang, T. RT-GCN: Gaussian-based spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for robust traffic prediction. Inf. Fusion 2024, 102, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, F.; Sun, T.; Yu, C.; Fang, Y.; Jin, G.; An, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qu, X.; Xu, Y. HUTFormer: Hierarchical U-Net transformer for long-term traffic forecasting. Commun. Transp. Res. 2025, 5, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, H.; Berry, R. Vision-LLMs for Spatiotemporal Traffic Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.11282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zeitouni, K.; Taher, Y.; Garcia-Rodriguez, S. Graph convolutional networks for traffic forecasting with missing values. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 37, 913–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikram, P.; Das, S.; Biswas, A. Dynamic attention aggregated missing spatial–temporal data imputation for traffic speed prediction. Neurocomputing 2024, 607, 128441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Yang, C.; Shao, Z.; Sun, T.; Qian, T.; Wei, W.; An, Z.; Xu, Y. Merlin: Multi-View Representation Learning for Robust Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Unfixed Missing Rates. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V.2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 3633–3644. [Google Scholar]

- Marisca, I.; Alippi, C.; Bianchi, F.M. Graph-based Forecasting with Missing Data through Spatiotemporal Downsampling. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; pp. 34846–34865. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, C.; Fu, Y.; Qian, T.; Xu, B.; Diao, B.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, X. BLAST: Balanced Sampling Time Series Corpus for Universal Forecasting Models. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V.2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 2502–2513. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, T.; Xu, Y. BasicTS: An Open Source Fair Multivariate Time Series Prediction Benchmark. In Proceedings of the Benchmarking, Measuring, and Optimizing, Sanya, China, 3–5 December 2023; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Shao, Z.; Yu, C.; Fu, Y.; An, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, X. ARIES: Relation Assessment and Model Recommendation for Deep Time Series Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.06060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Peng, L.; Ge, X. Spatio-temporal graph neural networks for missing data completion in traffic prediction. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 1057–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, Z.; Sun, T.; Yu, C.; Xu, Y.; Wang, F. Clustering-property matters: A cluster-aware network for large scale multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 4340–4344. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Sha, H.; Huang, J. STGNN-TTE: Travel time estimation via spatial–temporal graph neural network. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 126, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, C.; Yim, S.; Yoo, S.; Jung, C.; Yeon, H.; Jang, Y. V-DCRNN: Virtual Network-Based Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network for Estimating Unobserved Traffic Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 10336–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Cao, Z.; Wang, F. Dynamic Frequency Domain Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Forecasting. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 5245–5249. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A Time Series is Worth 64 Words: Long-term Forecasting with Transformers. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Côté, D.; Liu, Y. SAITS: Self-attention-based imputation for time series. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 219, 119619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, R.; Shahabi, C.; Liu, Y. Diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network: Data-driven traffic forecasting. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.01926. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, K.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, W.; He, H.; Hu, L.; Wang, P.; An, N.; Cao, L.; Niu, Z. FourierGNN: Rethinking multivariate time series forecasting from a pure graph perspective. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 69638–69660. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, G. Gatgpt: A pre-trained large language model with graph attention network for spatiotemporal imputation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Long, G.; Jiang, J.; Chang, X.; Zhang, C. Connecting the Dots: Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 753–763. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Yao, H.; Sun, Y.; Aggarwal, C.; Mitra, P.; Wang, S. Joint Modeling of Local and Global Temporal Dynamics for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting with Missing Values. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 5956–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bazarjani, A.; Chi, H.-G.; Choi, C.; Fu, Y. Uncovering the missing pattern: Unified framework towards trajectory imputation and prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 9632–9643. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Ye, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, J.J.Q. Traffic Prediction With Missing Data: A Multi-Task Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 4189–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Li, Z. Biased temporal convolution graph network for time series forecasting with missing values. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Shao, Z.; Qian, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, W.; An, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y. GinAR+: A Robust End-to-End Framework for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting With Missing Values. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 4635–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Wei, W.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, D.; Sun, T.; Jin, G.; Cao, X.; et al. Exploring Progress in Multivariate Time Series Forecasting: Comprehensive Benchmarking and Heterogeneity Analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, F.; Shao, Z.; Qian, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, W.; Xu, Y. GinAR: An End-To-End Multivariate Time Series Forecasting Model Suitable for Variable Missing. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 3989–4000. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, H.; Li, J.; Liang, Z.; Zheng, G.; Shi, B.; Wei, H. Uncertainty-aware Traffic Prediction under Missing Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Shanghai, China, 1–4 December 2023; pp. 1223–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, H. Multi-step electric vehicles charging loads forecasting: An autoformer variant with feature extraction, frequency enhancement, and error correction blocks. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, H.; Lv, X. Lithium-ion batteries remaining useful life prediction via Fourier-mixed window attention enhanced Informer with decomposition and adaptive error correction strategy. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Liu, H.; Lv, X. MetaGNSDformer: Meta-learning enhanced gated non-stationary informer with frequency-aware attention for point-interval remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 69, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Applying Machine Learning on Big Data With Apache Spark. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 53377–53393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Datasets | METR-LA | PEMS-BAY | PEMS04 | PEMS08 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variates | 207 | 325 | 307 | 170 |

| Timesteps | 34,272 | 52,116 | 16,992 | 17,833 |

| Granularity | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min | 5 min |

| Datasets | Models | Missing Rate 25% | Missing Rate 50% | Missing Rate 75% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | MAPE | MAE | MAPE | MAE | MAPE | ||

| METR-LA | PatchTST + SAITS | 3.83 | 10.95 | 3.94 | 11.23 | 4.08 | 11.94 |

| DCRNN + GPT4TS | 3.68 | 10.24 | 3.81 | 10.84 | 3.96 | 11.25 | |

| FourierGNN + GATGPT | 3.70 | 10.31 | 3.84 | 10.91 | 3.97 | 11.44 | |

| MTGNN + GRIN | 3.63 | 10.15 | 3.75 | 10.79 | 3.91 | 11.24 | |

| LGnet | 3.76 | 10.78 | 3.88 | 11.15 | 4.01 | 11.71 | |

| GC-VRNN | 3.62 | 9.97 | 3.71 | 10.48 | 3.85 | 11.14 | |

| RIHGCN | 3.57 | 9.94 | 3.66 | 10.41 | 3.77 | 10.87 | |

| GSTAE | 3.55 | 9.92 | 3.67 | 10.39 | 3.79 | 10.92 | |

| BiTGraph | 3.54 | 9.88 | 3.62 | 10.36 | 3.71 | 10.73 | |

| GinAR+ | 3.51 | 9.83 | 3.59 | 10.23 | 3.67 | 10.58 | |

| TFGCRN | 3.44 | 9.73 | 3.56 | 9.92 | 3.65 | 10.51 | |

| PEMS-BAY | PatchTST + SAITS | 2.34 | 5.45 | 2.49 | 5.81 | 2.81 | 7.06 |

| DCRNN + GPT4TS | 2.23 | 5.24 | 2.37 | 5.61 | 2.59 | 6.28 | |

| FourierGNN + GATGPT | 2.27 | 5.28 | 2.40 | 5.68 | 2.64 | 6.35 | |

| MTGNN + GRIN | 2.21 | 5.23 | 2.35 | 5.63 | 2.58 | 6.25 | |

| LGnet | 2.31 | 5.39 | 2.45 | 5.71 | 2.71 | 6.44 | |

| GC-VRNN | 2.17 | 5.17 | 2.31 | 5.52 | 2.55 | 6.11 | |

| RIHGCN | 2.07 | 4.92 | 2.35 | 5.67 | 2.62 | 6.32 | |

| GSTAE | 2.12 | 5.08 | 2.34 | 5.61 | 2.59 | 6.27 | |

| BiTGraph | 2.08 | 4.96 | 2.30 | 5.43 | 2.51 | 6.07 | |

| GinAR+ | 2.05 | 4.85 | 2.25 | 5.37 | 2.49 | 5.94 | |

| TFGCRN | 2.01 | 4.82 | 2.19 | 5.28 | 2.36 | 5.88 | |

| Datasets | Models | Missing Rate 25% | Missing Rate 50% | Missing Rate 75% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | MAPE | MAE | MAPE | MAE | MAPE | ||

| PEMS04 | PatchTST + SAITS | 24.37 | 17.45 | 26.04 | 18.17 | 27.23 | 18.67 |

| DCRNN + GPT4TS | 23.17 | 17.04 | 25.38 | 17.41 | 26.84 | 18.45 | |

| FourierGNN + GATGPT | 22.98 | 16.61 | 25.31 | 17.55 | 26.67 | 18.30 | |

| MTGNN + GRIN | 23.06 | 16.64 | 25.32 | 17.38 | 26.73 | 18.22 | |

| LGnet | 23.73 | 17.22 | 25.59 | 17.64 | 27.04 | 18.53 | |

| GC-VRNN | 22.81 | 16.52 | 24.33 | 17.13 | 26.43 | 17.59 | |

| RIHGCN | 23.45 | 17.06 | 25.17 | 17.38 | 26.75 | 18.02 | |

| GSTAE | 22.67 | 16.48 | 24.27 | 17.04 | 26.07 | 17.51 | |

| BiTGraph | 22.49 | 16.31 | 23.73 | 16.92 | 25.98 | 17.45 | |

| GinAR+ | 22.32 | 16.05 | 23.41 | 16.86 | 25.72 | 17.26 | |

| TFGCRN | 21.58 | 15.47 | 22.76 | 16.54 | 24.38 | 17.15 | |

| PEMS08 | PatchTST + SAITS | 21.43 | 13.79 | 22.18 | 14.25 | 25.06 | 16.42 |

| DCRNN + GPT4TS | 20.64 | 13.56 | 21.96 | 14.03 | 24.58 | 15.79 | |

| FourierGNN + GATGPT | 20.77 | 13.45 | 21.91 | 14.08 | 24.89 | 15.85 | |

| MTGNN + GRIN | 20.59 | 13.34 | 21.78 | 13.98 | 24.51 | 15.68 | |

| LGnet | 21.51 | 13.85 | 22.14 | 14.31 | 24.95 | 16.26 | |

| GC-VRNN | 20.42 | 13.21 | 21.67 | 13.91 | 23.45 | 15.06 | |

| RIHGCN | 20.53 | 13.31 | 21.71 | 14.08 | 23.51 | 15.34 | |

| GSTAE | 20.62 | 13.39 | 21.83 | 14.12 | 23.79 | 15.63 | |

| BiTGraph | 20.21 | 13.04 | 21.59 | 13.82 | 23.06 | 14.79 | |

| GinAR+ | 20.03 | 12.97 | 21.55 | 13.75 | 22.93 | 14.52 | |

| TFGCRN | 19.79 | 12.75 | 21.04 | 13.52 | 22.33 | 14.38 | |

| Datasets | Models | Missing Rate 25% | Missing Rate 50% | Missing Rate 75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEMS-BAY | w/o STE | 2.23 | 2.46 | 2.62 |

| w/o EN | 2.07 | 2.24 | 2.43 | |

| w/o temporal embedding | 2.09 | 2.31 | 2.54 | |

| w/o spatial embedding | 2.12 | 2.28 | 2.47 | |

| TFGCRN | 2.01 | 2.19 | 2.36 | |

| PEMS08 | w/o STE | 22.17 | 23.42 | 25.08 |

| w/o EN | 20.16 | 21.77 | 23.35 | |

| w/o temporal embedding | 21.36 | 22.65 | 24.02 | |

| w/o spatial embedding | 21.54 | 22.52 | 23.47 | |

| TFGCRN | 19.79 | 21.04 | 22.33 |

| Config | Values |

|---|---|

| optimizer | Adam [82] |

| learning rate | 0.002 |

| weight decay | 0.0001 |

| embedding size | 64 |

| graph embedding size | 64 |

| number of layers | 3 |

| TopK | 24 |

| dropout | 0.15 |

| learning rate schedule | MultiStepLR |

| clip gradient normalization | 5 |

| milestone | [1, 5, 25, 50, 75, 100] |

| discount coefficient | 0.5 |

| batch size | 32 |

| epoch | 101 |

| Datasets | Models | Missing Rate 25% | Missing Rate 50% | Missing Rate 75% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEMS-BAY | Multi-head attention | 2.15 | 2.34 | 2.54 |

| Mask attention | 2.19 | 2.41 | 2.63 | |

| Graph attention | 2.13 | 2.33 | 2.52 | |

| DTW | 2.04 | 2.22 | 2.41 | |

| Two FLN | 2.07 | 2.25 | 2.45 | |

| Single TFGCN | 2.08 | 2.27 | 2.46 | |

| LSTM | 2.05 | 2.24 | 2.42 | |

| TFGCRN | 2.01 | 2.19 | 2.36 | |

| PEMS08 | Multi-head attention | 21.21 | 22.65 | 23.92 |

| Mask attention | 21.57 | 23.06 | 24.31 | |

| Graph attention | 21.03 | 22.34 | 23.66 | |

| DTW | 20.17 | 21.56 | 22.85 | |

| Two FLN | 20.11 | 21.62 | 22.90 | |

| Single TFGCN | 20.58 | 22.01 | 23.37 | |

| LSTM | 20.04 | 21.43 | 22.79 | |

| TFGCRN | 19.79 | 21.04 | 22.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Feng, T. TFGCRN: Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Incomplete Traffic Forecasting. Mathematics 2025, 13, 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244003

Hu J, Feng T. TFGCRN: Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Incomplete Traffic Forecasting. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jiazhan, and Tao Feng. 2025. "TFGCRN: Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Incomplete Traffic Forecasting" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244003

APA StyleHu, J., & Feng, T. (2025). TFGCRN: Temporal–Frequency Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network for Incomplete Traffic Forecasting. Mathematics, 13(24), 4003. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13244003