Abstract

Predictive process monitoring estimates the future behaviour of running process instances based on historical event logs, with typical tasks including next-activity prediction, remaining-time estimation, and risk assessment. Existing recurrent and Transformer-based models achieve strong accuracy on individual logs but transfer poorly across processes and underuse the rich graph structure of event data. This paper introduces ProcessGFM, a domain-specific graph pretraining prototype for predictive process monitoring on event graphs. ProcessGFM employs a hierarchical graph neural architecture that jointly encodes event-level, case-level, and resource-level structure and is pretrained in a self-supervised manner on multiple benchmark logs using masked activity reconstruction, temporal order consistency, and pseudo-labelled outcome prediction. A multi-task prediction head and an adversarial domain alignment module adapt the pretrained backbone to downstream tasks and stabilise cross-log generalisation. On the BPI 2012, 2017, and 2019 logs, ProcessGFM improves next-activity accuracy by 2.7 to 4.5 percentage points over the best graph baseline, reaching up to 89.6% accuracy and 87.1% macro-F1. For remaining-time prediction, it attains mean absolute errors between 0.84 and 2.11 days, reducing error by 11.7% to 18.2% relative to the strongest graph baseline. For case-level risk prediction, it achieves area-under-the-curve scores between 0.907 and 0.934 and raises precision at 10% recall by 6.7 to 8.1 percentage points. Cross-log transfer experiments show that ProcessGFM retains between about 90% and 96% of its in-domain next-activity accuracy when applied zero-shot to a different log. Attention-based analysis highlights critical subgraphs that can be projected back to Petri net fragments, providing interpretable links between structural patterns, resource handovers, and late cases.

Keywords:

predictive process monitoring; process mining; graph neural networks; graph representation learning; event logs; remaining time prediction; risk prediction; domain adaptation; self-supervised learning MSC:

68T0; 68T09; 68Q85

1. Introduction

Information systems in finance, healthcare, manufacturing, and public administration continuously record detailed execution logs of business processes. Process mining has emerged as a discipline that extracts insights from these event logs to discover process models, analyse conformance, and support operational decision making. Predictive process monitoring extends this paradigm by learning models that anticipate the future behaviour of running cases. Typical objectives include predicting which activity will occur next, how much time remains until completion, or whether a case will violate a service-level agreement or lead to an undesired outcome, such as breaching service-level agreements or triggering undesired exception cases [1,2,3].

Early predictive process monitoring methods relied on hand-crafted features extracted from traces and traditional machine learning models. Subsequent work introduced recurrent neural networks, particularly LSTMs and GRUs, which substantially improved next-activity and remaining-time prediction by encoding prefixes of event sequences [4,5,6]. More recent approaches adopt Transformer architectures and sophisticated positional encodings to handle long and complex traces [7]. In parallel, researchers have started to exploit the graph structure of processes. This includes graph neural networks defined on Petri net place graphs, directly follows graphs, and object-centric event graphs [8]. These models show that graph structure carries complementary information beyond textual activity labels and timestamps.

Despite this progress, three important limitations remain. First, most predictive monitoring models are trained and evaluated on a single event log. They tend to overfit to the idiosyncrasies of a single process and do not generalise well to different processes, even when they belong to the same organisation or domain [9]. Second, existing graph-based models are typically small and task-specific. They are designed to solve either next-activity prediction or remaining-time prediction on one log, and they do not exploit the possibility of pretraining across multiple logs. Third, even when graph structure is used, most methods rely on simple representations such as directly follows graphs and do not fully capture the joint interactions between events, cases, and resources [10,11].

At the same time, the broader graph learning community has started to explore graph foundation models, which are large graph neural backbones pretrained on heterogeneous graphs with self-supervised objectives and later adapted to diverse tasks [12,13]. Such models have demonstrated strong transfer performance in recommendation, molecular property prediction, and knowledge graphs, and surveys now classify them as a new generation of representation learning for structured data [14,15]. However, graph foundation models have not yet been systematically explored in the context of process mining and predictive monitoring. This gap suggests a natural research question: can one develop a domain-specific graph foundation model that pretrains on multiple event logs and generalises across predictive process monitoring tasks?

This paper answers this question by introducing ProcessGFM, a domain-specific graph pretraining prototype tailored to predictive process monitoring on event graphs. ProcessGFM adopts a hierarchical architecture that jointly encodes event-level, case-level, and resource-level structure. It is pretrained with self-supervised objectives that are specific to event logs and then adapted through a multi-task prediction head to next-activity prediction, remaining time regression, and risk classification. An adversarial domain alignment module encourages the model to learn process-agnostic representations that transfer across logs. Extensive experiments on three BPI Challenge logs demonstrate that ProcessGFM achieves consistent improvements over strong baselines and maintains a high level of performance in cross-log scenarios.

The main contributions of this work are as follows.

- We introduce a domain-specific graph pretraining prototype for predictive process monitoring. The model performs multi-log self-supervised pretraining and supports several downstream prediction tasks within a unified backbone, but its scale is intentionally moderate (four public logs) compared with universal graph foundation models [16].

- We develop a hierarchical graph representation that jointly models events, cases, and resources, complemented by temporal encodings that respect both control-flow structure and time-dependent behaviour.

- We design a multi-task adaptation mechanism together with an adversarial domain alignment module. These components jointly promote strong predictive performance and enhance robustness when transferring across heterogeneous event logs.

- We provide a comprehensive empirical study on real-life event logs, including detailed ablation experiments and interpretability analysis in which high-attention subgraphs are projected back to process models to expose behavioural bottlenecks.

2. Related Work

Related work falls into three strands: predictive process monitoring, graph-based process mining, and graph foundation models.

Predictive process monitoring combines process mining with predictive analytics. Early studies extracted features from running traces and trained classical classifiers and regressors to predict the next activity or the remaining time [17,18]. Later, recurrent models such as LSTM networks and gated recurrent units were used to encode prefixes, leading to higher accuracy in both next-activity and remaining-time tasks [4,19]. More recent studies explore convolutional and Transformer-based architectures and sophisticated positional encodings along the trace [7,20,21,22]. These methods, however, almost always treat each trace as a linear sequence, with limited structural information beyond positional indices.

Graph-based process mining attempts to incorporate the concurrent and branching nature of processes. Graph convolutional networks have been applied to place graphs derived from Petri nets to interpret recurrent models and to assist in process discovery [23,24]. Directly follows graphs have been used as input to graph neural networks for predictive tasks and process discovery, with recent work exploring different variants of the underlying graph representation [25,26,27,28]. Object-centric predictive monitoring represents event logs as heterogeneous graphs linking events, cases, and objects and uses graph attention networks to encode these relations [29]. Heterogeneous graph neural networks have also been proposed for explainable predictive monitoring, where attention weights highlight critical activity and resource combinations [30]. Related work on heterogeneous graph contrastive learning further emphasises multi-scale, attribute-aware views [31], which is conceptually aligned with our use of multiple structural signals but tailored to event graphs and control-flow- and outcome-specific objectives. These models show the benefit of graph structure but remain limited to single logs and specific tasks.

Graph foundation models aim to bring the success of large pretrained models to the graph domain. Surveys distinguish between universal, task-specific, and domain-specific graph foundation models and analyse their backbone architectures, pretraining tasks, and adaptation mechanisms [16]. Pretraining strategies include masked node and edge prediction, contrastive learning across graph views, subgraph prediction, motif prediction, and structural encoding [32,33]. Tutorial articles discuss the challenges of structural alignment, scalability, and evaluation across heterogeneous graphs [34]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has introduced a graph foundation model specialised for predictive process monitoring on event graphs. Existing graph-based process mining methods either focus on process discovery or predictive tasks on a single log and do not exploit cross-log pretraining. Following the taxonomy of Liu et al. [16], ProcessGFM should therefore be viewed as a domain-specific graph pretraining prototype rather than a universal graph foundation model: it focuses on predictive process monitoring, is pretrained on a small number of business-process logs, and is evaluated on a restricted set of tasks.

3. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

An event log is a finite collection of traces that record the execution of a business process. We denote an event log by

where each trace corresponds to a single process instance or case.

Each trace is represented as a finite sequence of events

with as the length of case i. Every event is described by a tuple of attributes

where is the activity label, is the timestamp, is the resource identifier, and collects additional numerical or categorical attributes [35].

Here we explicitly distinguish between “activity” and “event”. An activity denotes a process-level action type (i.e., a categorical label in the activity set ), while an event is a concrete execution instance of an activity within a specific case, associated with a timestamp, a resource, and optional attributes. Thus, multiple events across different cases (or within the same case) may share the same activity label. In other words, activity is the type-level concept, whereas event is the instance-level record.

For a fixed trace , we define the prefix of length k as

The next activity label associated with this prefix is

and the remaining time of the case at prefix is defined as

Risk labels are defined at the case level by a binary variable , indicating whether case will lead to an undesired outcome. For simplicity, every prefix inherits the eventual outcome of its case so that . In order to exploit structural information, we construct for each log L a heterogeneous event graph

where V is the set of nodes, is the set of directed edges, assigns node types, and assigns edge types. We consider three node types,

where denotes event nodes, case nodes, and resource nodes. For each event , we create an event node ; for each case , a case node ; and for each resource r, a resource node .

Edges encode control-flow, case membership, and organisational relations. Control-flow edges connect successive events within a trace, case membership edges connect events to their case, and resource assignment edges connect events to their executing resources. Organisational edges connect resources that collaborate on the same case within a fixed time window . We write the full edge set as

where the four subsets correspond to these relations. Edge types are determined by membership in these subsets via .

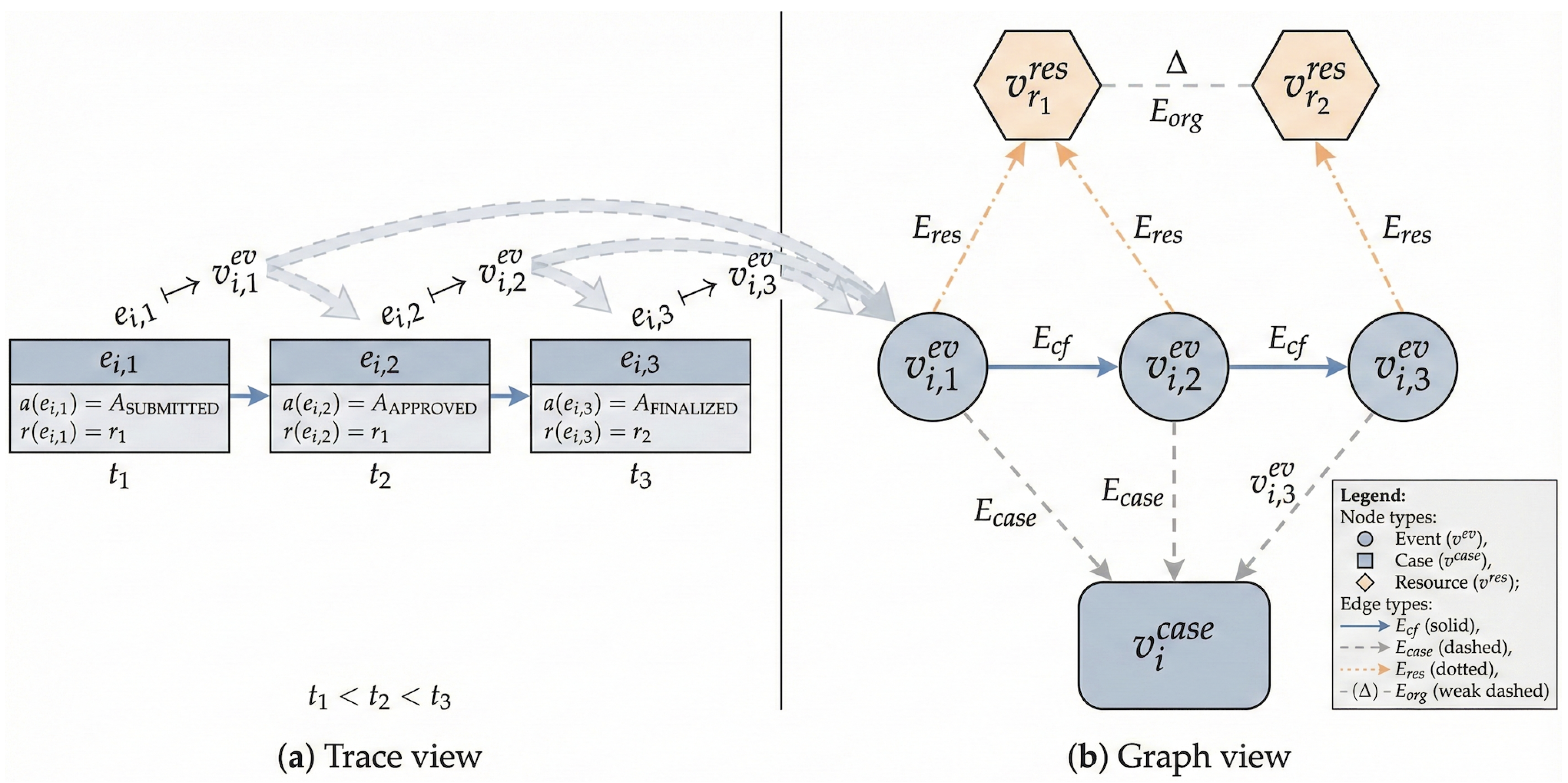

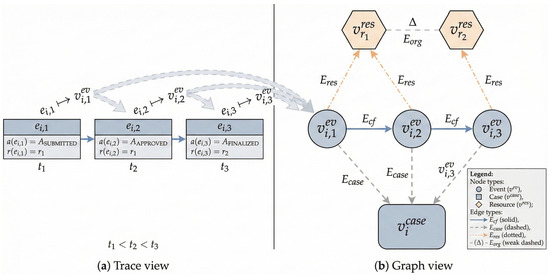

Example 1

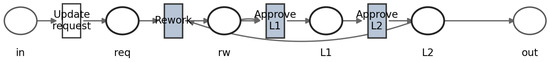

(Trace-to-graph construction). Consider a trace from BPI2012 with activities , , and . We create three event nodes , , , one case node , and one resource node for each distinct resource r executing any of these events. Control-flow edges connect successive events, i.e., and . Case membership edges link each event to its case, for , and resource assignment edges connect events to their executor, . If two resources r and co-occur in the same case within a time window Δ, we additionally add organisational edges . Figure 1 provides a schematic illustration of this trace-to-graph construction.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of Example 1. (a) A sample trace prefix with three events. (b) The corresponding heterogeneous event graph construction, showing event, case, and resource nodes, as well as control-flow, case membership, resource assignment, and organisational edges. For clarity, the schematic example uses a short trace; the same construction rules apply to full-length traces in all logs.

For a prefix of trace , we define the induced prefix subgraph

where contains the case node , the event nodes for , the corresponding resource nodes, and all edges between these nodes inherited from G.

The predictive process monitoring tasks considered in this work can be formulated as learning conditional distributions over labels given prefix subgraphs. The next-activity prediction problem is to approximate

the remaining time prediction problem is to approximate

and the risk prediction problem is to approximate

We are given a finite collection of event logs

with corresponding event graphs for . Our goal is to learn a single parameterised backbone mapping

which assigns to every prefix subgraph a representation vector . On top of this backbone, a collection of task-specific heads

defines composite predictors , , and . In addition to minimising prediction error on individual logs, we require that the backbone generalises across logs, in the sense that its performance under domain shifts between and remains stable when evaluated on prefixes from not seen during fine-tuning.

4. The ProcessGFM Model

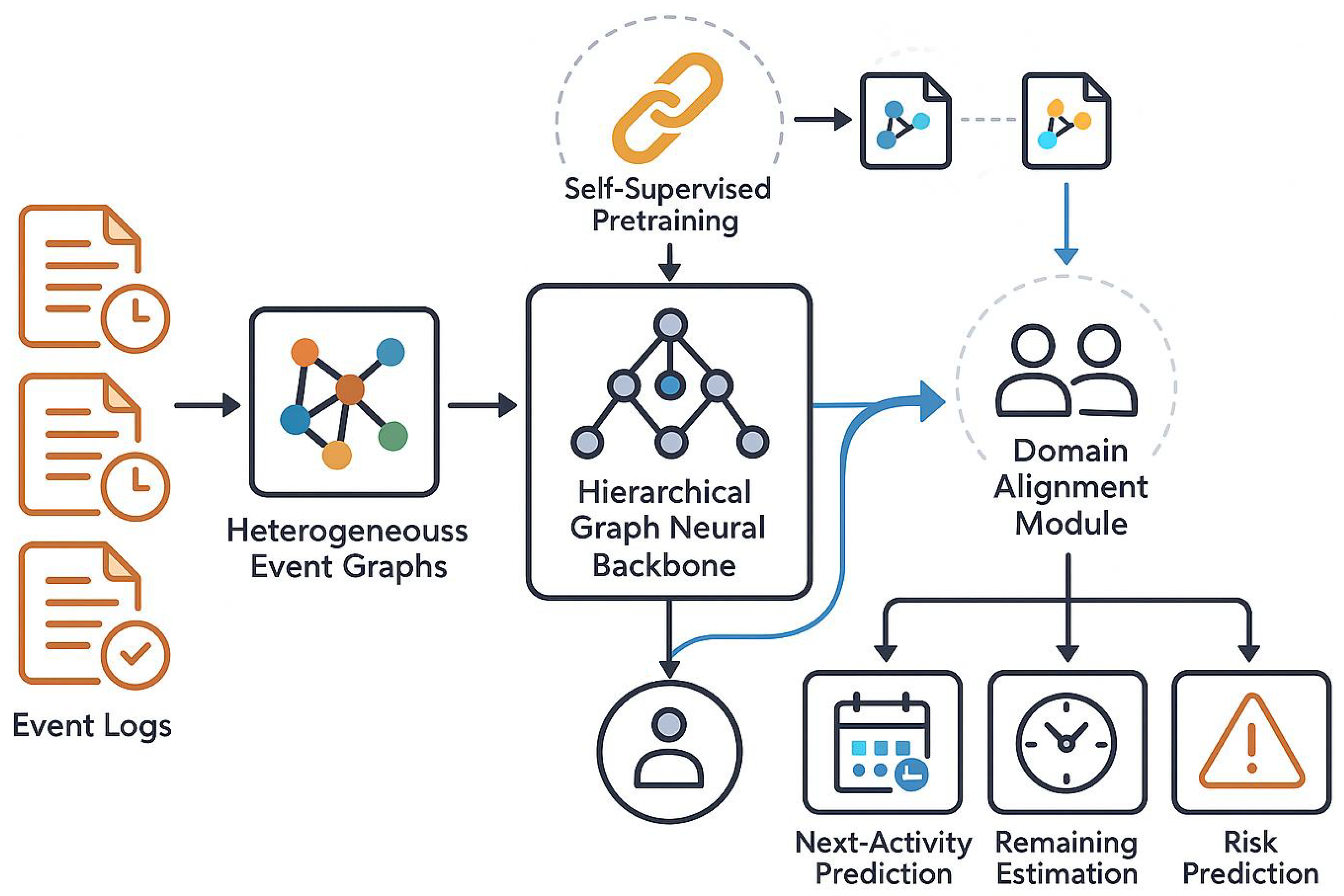

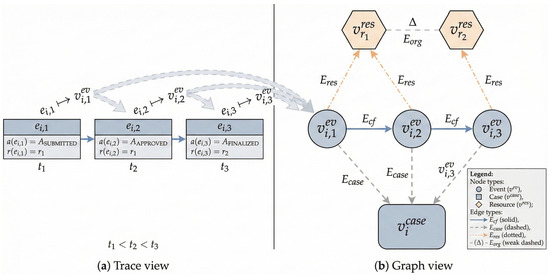

This section describes the ProcessGFM architecture, its self-supervised pretraining objectives, the multi-task adaptation mechanism, and the domain alignment module. An overview of the framework is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the ProcessGFM framework. Event logs are transformed into heterogeneous event graphs, which are processed by a hierarchical graph neural backbone. Self-supervised pretraining on multiple logs produces a pretrained graph backbone. Task-specific heads and a domain alignment module adapt the backbone to next-activity prediction, remaining time estimation, and risk prediction.

4.1. Hierarchical Graph Backbone

For each node in an event graph G, we construct an initial feature vector by concatenating type-specific embeddings and numerical attributes and projecting them to a common dimension. Formally, we use a type-dependent embedding function

and set

where contains the raw attributes of node v and is its initial hidden representation.

The hierarchical backbone consists of L stacked message-passing layers. At layer , each node v aggregates messages from its neighbourhood. Let denote the set of in-neighbours of v, and let be an edge feature vector associated with edge . The unnormalised attention coefficient from node u to node v at layer ℓ is defined as

where and are type-specific weight matrices, is a shared edge weight matrix, is a nonlinearity, is an edge-type-specific attention vector, and denotes concatenation.

The normalised attention coefficient is obtained through a softmax over the neighbourhood:

The aggregated message at node v is then

The updated hidden state of node v is computed via a residual transformation and normalisation,

where is a type-specific projection and is a nonlinear activation function.

After L layers, we obtain final node representations for all nodes. For a prefix subgraph , we construct a prefix-level representation by aggregating the representations of the case node and the event nodes corresponding to the prefix . Let

denote this set of nodes. We define attention weights on as

where is a learned query vector. The prefix representation is then

and serves as the shared foundation representation for all downstream predictive tasks.

4.2. Self-Supervised Pretraining

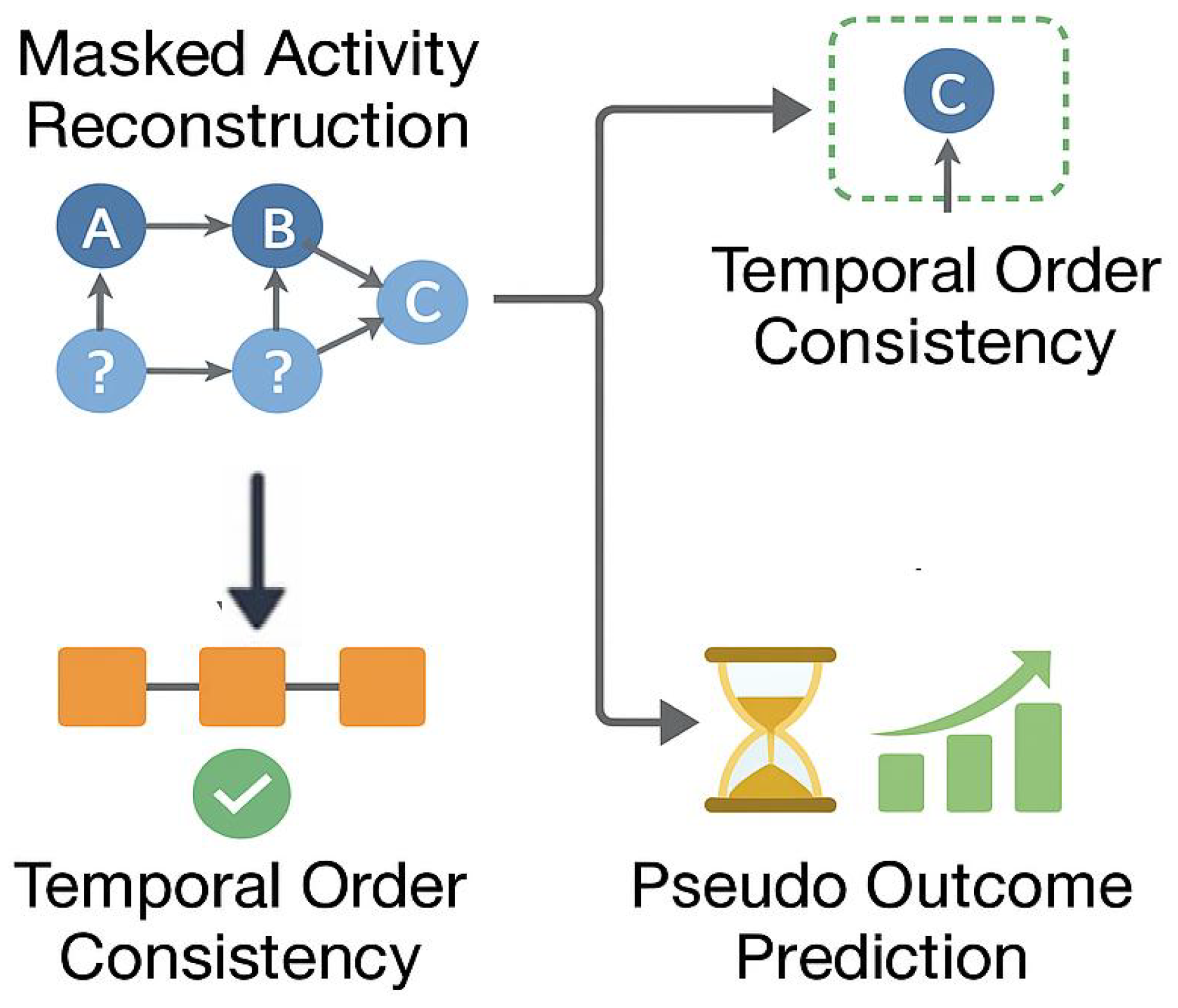

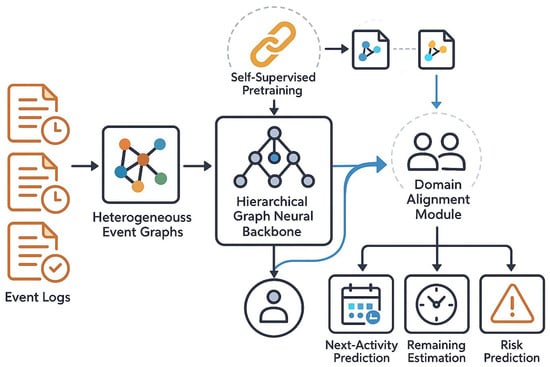

The backbone parameters are initialised through self-supervised pretraining on all logs in , using three complementary objectives. Figure 3 summarises these pretraining tasks.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the self-supervised pretraining tasks in ProcessGFM. Masked activity reconstruction randomly masks event labels and predicts them from the graph context. Temporal order consistency determines whether sampled subsequences respect the original temporal order. Pseudo outcome prediction uses coarse-grained efficiency labels derived from case duration and performance indicators.

For masked activity reconstruction, we select for each graph G a random subset of event nodes and replace their activity labels by a special mask token. Let denote the original activity label of event node v. The masked activity loss is the cross-entropy

where denotes the graph with masked labels and is induced by a softmax layer applied to node representations.

For temporal order consistency and pseudo outcome prediction, we adopt analogous cross-entropy objectives defined on subsequences and case-level representations, respectively. Denoting their losses by and , the overall pretraining objective is a weighted sum

with non-negative weights . Minimising over all logs in yields a backbone that captures control-flow regularities, temporal constraints, and coarse outcome information.

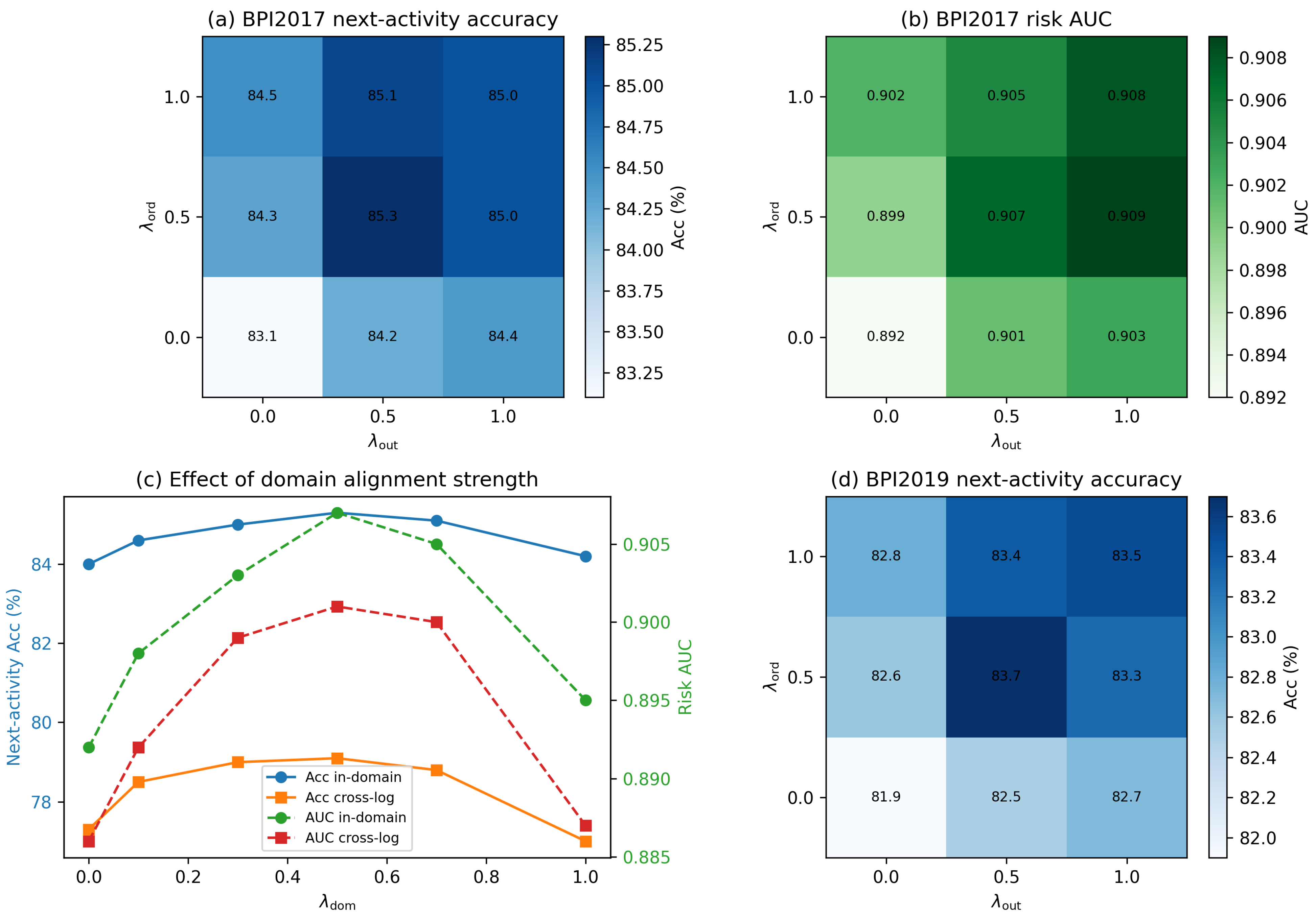

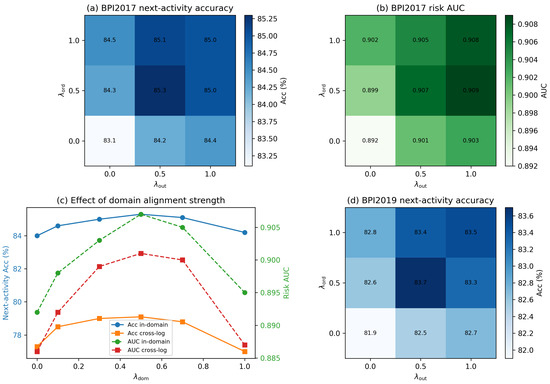

The weights are chosen to balance these three sources of supervision. To assess how sensitive ProcessGFM is to this choice, we performed a small grid search over while fixing and evaluated next-activity accuracy, remaining-time MAE, and risk AUC on BPI2017 and BPI2019; detailed values are reported in Table A8 and Table A9 in Appendix B. Variants that use only masked activity reconstruction consistently underperform variants that also include temporal order or pseudo-outcome objectives, confirming that all three tasks contribute a complementary signal. The configuration , which we use in all other experiments, achieves a favourable trade-off between the three downstream metrics on both logs, while neighbouring settings such as or yield very similar results. This indicates that ProcessGFM is not overly sensitive to moderate changes in the pretraining loss weights.

4.3. Multi-Task Prediction Head

After pretraining, the backbone is adapted to predictive monitoring tasks by attaching a multi-task head to the prefix representations . The next-activity predictor maps to a probability distribution over the activity set :

where and are activity-specific parameters. The risk predictor outputs a probability

where , , and is the logistic function. Remaining time is predicted by an affine mapping in , which we denote by .

Given a set of labelled prefixes , we define task-specific losses , , and based on cross-entropy and mean absolute error. The total multi-task adaptation loss is

with non-negative weights that control the relative importance of the tasks.

4.4. Domain Alignment

Event logs from different organisations and domains may have disjoint activity labels, distinct control-flow structures, and heterogeneous resource behaviours. To encourage the backbone to learn representations that are robust under such domain shifts, ProcessGFM employs an adversarial domain alignment module.

For every prefix from log , we associate a domain label . A domain classifier maps the prefix representation to a probability distribution over domains:

where and are domain-specific parameters and denotes the collection of these parameters. The domain classification loss is the average cross-entropy between and .

Domain alignment is achieved by solving the minimax problem

where controls the strength of alignment. In practice, this objective is implemented via a gradient reversal layer that multiplies the gradient of with respect to by during backpropagation, thereby encouraging the backbone to produce representations that are informative for the predictive tasks while being as invariant as possible with respect to the domain labels.

To analyse the stability of adversarial domain alignment, we varied the alignment strength on BPI2017 and evaluated both in-domain performance and cross-log transfer to BPI2019; full numerical results are provided in Table A10 in Appendix B. Values in the range – were numerically stable and consistently improved cross-log robustness over , with providing the best trade-off between task performance and invariance. For larger values (e.g., ) we observed oscillations in the domain loss and a slight degradation of downstream metrics, which is consistent with known issues in minimax training. In all experiments, we therefore fix , use a smaller learning rate for the domain classifier, and apply gradient clipping to ensure stable training.

5. Datasets and Experimental Setup

We evaluate ProcessGFM on three real-life event logs from the BPI Challenges and on a synthetic hospital log used in prior work on predictive monitoring benchmarks [36]. Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of these logs.

Table 1.

Overview of event logs used in this study. Duration is measured from the first to the last event in the log.

The BPI2012 log records a loan application process at a Dutch financial institution and has been widely used in predictive monitoring experiments [36,37]. The BPI2017 log describes loan offers in an updated information system of the same institution [35]. The BPI2019 log captures the purchase order handling process at a multinational coatings and paints company and is notable for its larger number of cases and events. The hospital log simulates patient flows in a medium-sized hospital and is taken from an existing benchmark suite [36].

Across all logs, the resulting heterogeneous event graphs are extremely sparse: the overall directed edge density is on the order of . Each event node has on average between 5.0 and 5.7 incident edges, reflecting incoming and outgoing control-flow links, case membership, resource assignment, and a small number of organisational edges. These statistics confirm that the graphs remain tractable in size despite the large number of events and that sparsity can be exploited by graph neural network architectures. Table 2 summarises the corresponding node and edge counts for these heterogeneous event graphs.

Table 2.

Graph statistics for the heterogeneous event graphs derived from each log.

For each log, we follow standard practice and split cases into training, validation, and test sets in proportions 70%, 10%, and 20%. Prefixes are generated by cutting each trace at every event except the last and using the next event as the target for next-activity prediction. Remaining time is defined as the difference in hours between the timestamp of the last event and the last observed event in the prefix. Risk labels are derived from trace-level outcomes: cases exceeding the 80th percentile of completion time or marked as undesirable according to domain attributes are labelled as high risk.

We pretrain ProcessGFM on the union of all four logs using full traces and the three self-supervised objectives for all in-domain experiments. For the leave-one-log-out cross-log experiments, we additionally train separate backbones where the eventual test log is excluded from the pretraining corpus. Pretraining runs for 50 epochs with early stopping based on validation loss on a held-out subset of prefixes. For adaptation, we fine-tune separate multi-task heads and domain classifiers for each log while keeping the backbone shared. Training uses the Adam optimiser with a learning rate of for the heads and for the backbone, mini-batches of 64 prefixes, and a maximum prefix length of 100 events.

As baselines, we consider a strong LSTM model, a Transformer with positional trace encoding, a gated graph sequence neural network (GGSNN) defined on directly follows graphs, and a heterogeneous graph neural network for predictive monitoring inspired by recent work on explainable PPM [30,38,39,40,41]. All baselines are tuned to reach competitive performance on validation data. To make comparison fair, all models have between 3 and 6 million trainable parameters.

Hyperparameters for all models are selected via validation-based random search. For each baseline and for ProcessGFM, we sample between 24 and 32 configurations from predefined ranges (hidden dimension , number of layers , dropout , and learning rate ) on BPI2012 and select the configuration with the best average validation performance across next-activity and remaining-time tasks. The same configuration is then reused on the other logs without further tuning. We also observe that moderate variations around the selected configuration (e.g., layers or hidden units) change all metrics by less than 1.5 percentage points, which suggests that our conclusions are robust to reasonable hyperparameter choices.

Table 3 reports model sizes and training time. ProcessGFM has a larger backbone and requires a one-time pretraining cost, but fine-tuning time per log remains comparable to that of single-log graph baselines.

Table 3.

Model sizes and training cost. Pretraining time is measured on a single GPU equivalent.

6. Results and Analysis

This section presents quantitative results for next-activity prediction, remaining-time prediction, and risk prediction, followed by cross-log transfer experiments, ablation studies, and qualitative interpretability analysis.

6.1. Next-Activity Prediction

Table 4 summarises next-activity prediction performance. We report accuracy and macro-F1 on the test sets of each log.

Table 4.

Next-activity prediction performance on test sets. Best results per column are in bold.

ProcessGFM achieves the best performance on all three logs, with substantial improvements over the strongest baseline. On BPI2012, it improves accuracy by 2.7 percentage points and macro-F1 by 3.9 points compared with the HeteroGNN PPM model. On BPI2017, the gains are 3.8 and 4.3 points, and on BPI2019 they are 4.5 and 5.7 points. Gains in macro-F1 are particularly important because they indicate better performance on less frequent activities, which are often the most critical from an operational perspective.

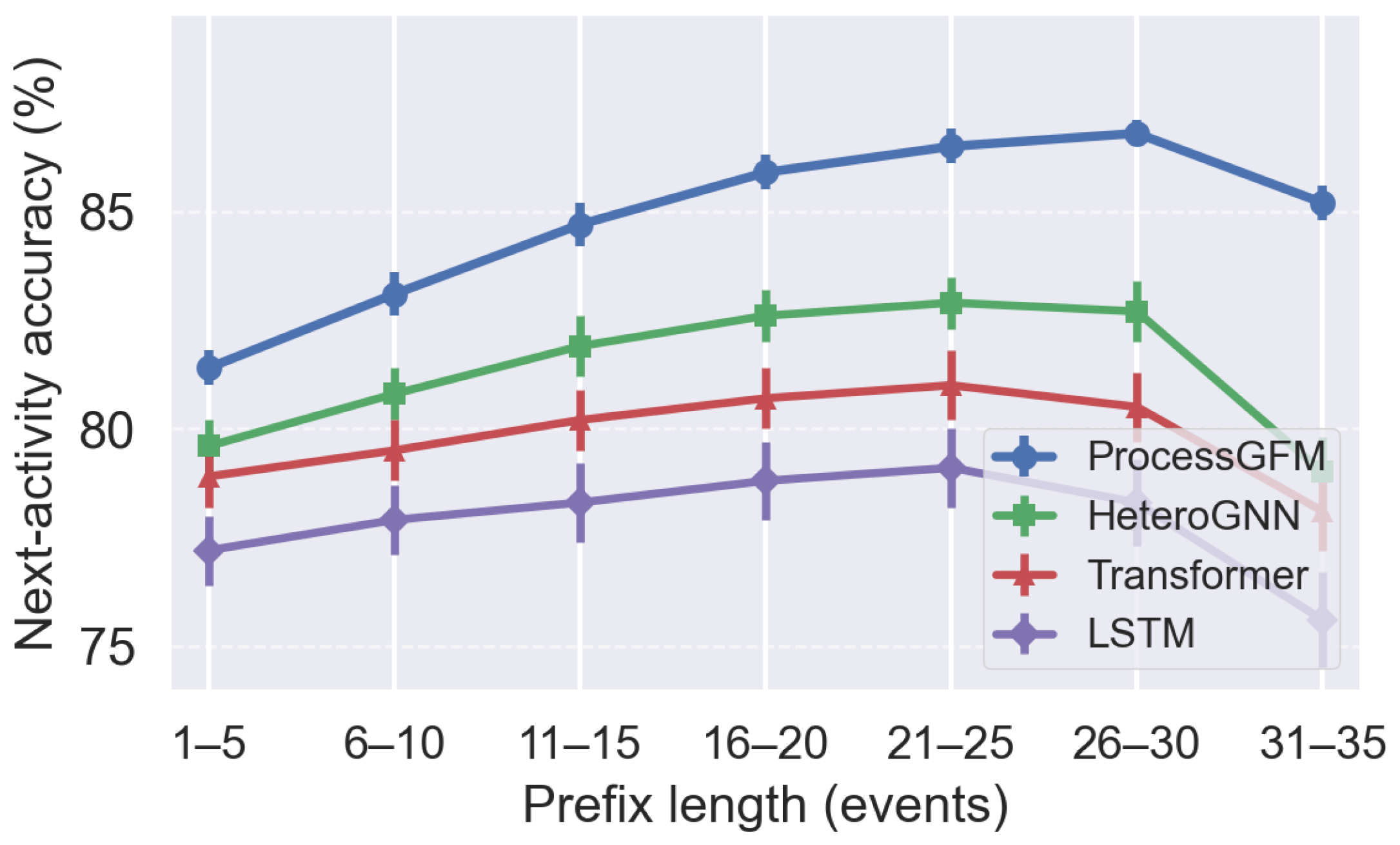

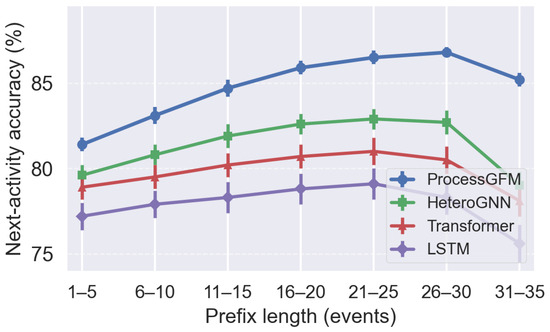

Figure 4 illustrates how accuracy evolves with prefix length on BPI2017. For each model, prefixes are grouped by length into intervals of five events, and average accuracy is reported. At short prefixes, sequence-based models perform comparatively well because the control-flow structure is simple. As prefixes grow longer and the process becomes more complex, ProcessGFM maintains a higher accuracy than all baselines, with a gap of up to 8.2 percentage points at prefixes between 30 and 35 events. This behaviour confirms that the hierarchical graph backbone preserves useful information in long traces.

Figure 4.

Next-activity accuracy as a function of prefix length on BPI2017. Prefix lengths are binned into intervals of five events.

6.2. Remaining-Time Prediction

Table 5 reports remaining-time prediction results. We use mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE), measured in days, together with the coefficient of determination . Table 6 reports remaining-time prediction on BPI2019 and Hospital.

Table 5.

Remaining time prediction performance. Lower MAE and RMSE are better; higher is better.

Table 6.

Remaining time prediction performance on BPI2019 and the hospital log.

Table 5 and Table 6 show that across all logs, ProcessGFM yields the lowest MAE and RMSE and the highest . On BPI2012, it reduces MAE by 0.28 days compared with HeteroGNN PPM, corresponding to a relative reduction of 18.2%. On BPI2017, the reduction is 15.2%; on BPI2019, it is 11.7%; and on the hospital log, it is 14.6%. These improvements are consistent with the intuition that remaining-time prediction benefits from jointly modelling control-flow, resources, and temporal attributes in a graph.

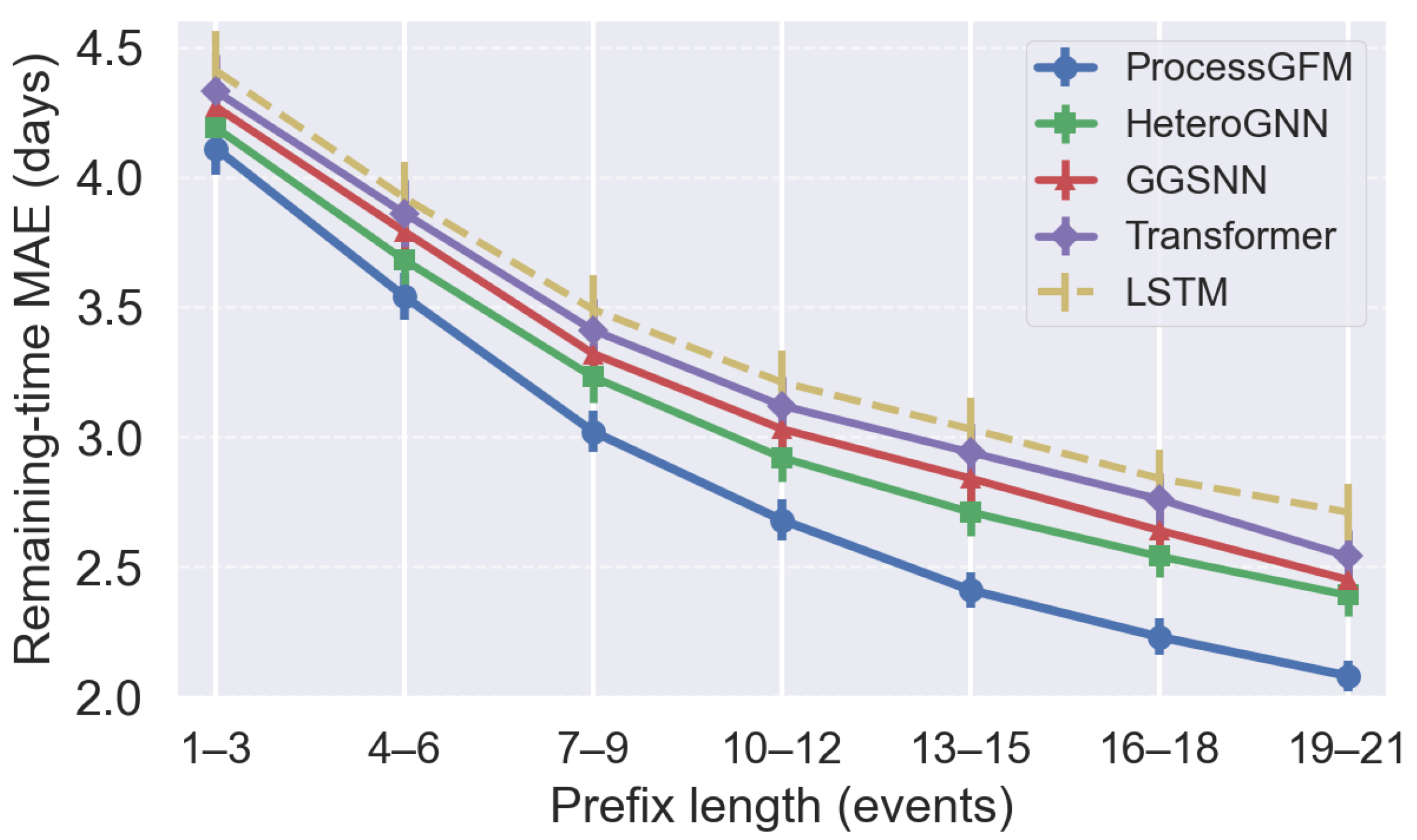

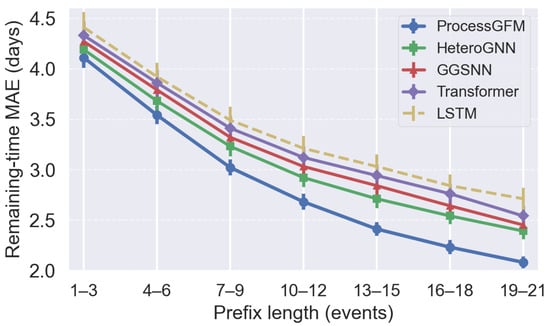

Figure 5 plots MAE as a function of prefix length for BPI2019. At very short prefixes, uncertainty is inherently high and all models show similar MAE. As more events are observed, ProcessGFM reduces MAE more quickly than baselines, converging to roughly two days of average error near completion, while sequence models remain above 2.4 days.

Figure 5.

Remaining-time MAE as a function of prefix length on BPI2019.

6.3. Risk Prediction

We next consider case-level risk prediction. Table 7 shows area under the ROC curve (AUC), F1-score, and precision at 10% recall (P@10%) for identifying high-risk cases.

Table 7.

Risk prediction performance. P@10% is precision at 10% recall.

Table 7 and Table 8 show that ProcessGFM delivers the highest AUC and F1 across all logs. The most pronounced improvement is in P@10%, which measures the precision of the top fraction of cases flagged as high risk. On BPI2012, ProcessGFM raises P@10% from 82.7% to 89.4%, and on BPI2019 from 79.8% to 87.9%. These gains are particularly relevant in operational settings where only a small proportion of cases can be inspected manually.

Table 8.

Risk prediction performance on BPI2019 and the hospital log.

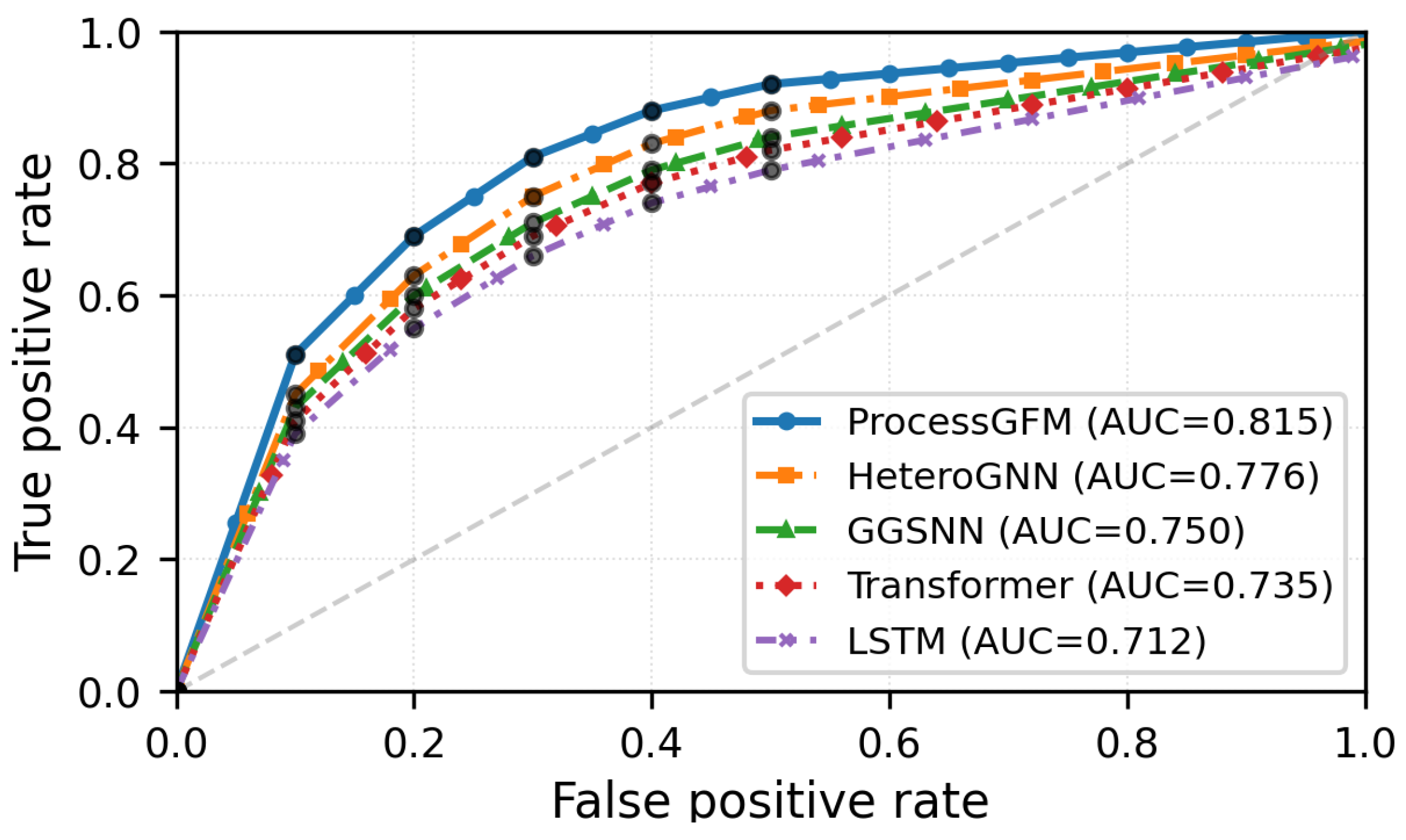

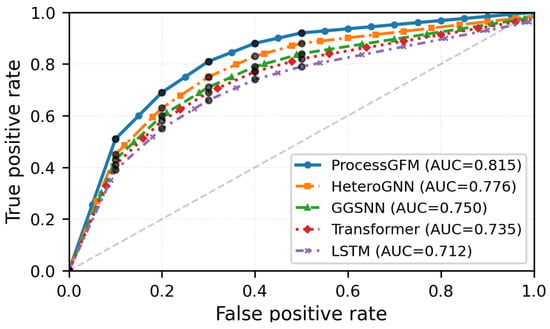

Figure 6 plots ROC curves for BPI2017, showing a consistent improvement in the true positive rate across the full range of false positive rates. The area under the ProcessGFM curve is 0.907 compared with 0.871 for the strongest baseline.

Figure 6.

ROC curves for risk prediction on BPI2017.

6.4. Cross-Log Transfer

To assess cross-log transfer, we simulate a setting where a model is fine-tuned on one log and evaluated without further adaptation on another. Table 9 reports next-activity accuracy for four pairs of logs. For each pair, the row indicates the training log and the column the test log.

Table 9.

Leave-one-log-out cross-log next-activity accuracy. For each test log (column), the backbone is pretrained only on the remaining three logs, excluding the test log from pretraining.

In this leave-one-log-out setup, the ProcessGFM backbone is pretrained only on the three logs that are different from the eventual test log. ProcessGFM retains between 92% and 96% of its in-domain next-activity accuracy when evaluated zero-shot on a different log (e.g., 79.1% vs. 83.7% when transferring from BPI2017 to BPI2019), whereas the HeteroGNN baseline often falls below 85% of its in-domain performance. These results indicate that the self-supervised pretraining and adversarial domain alignment help the backbone capture patterns that are stable across processes. We further report cross-log remaining-time and risk prediction when training on BPI2017 and testing on BPI2019 in Table A5, where ProcessGFM exhibits a smaller degradation than the HeteroGNN baseline.

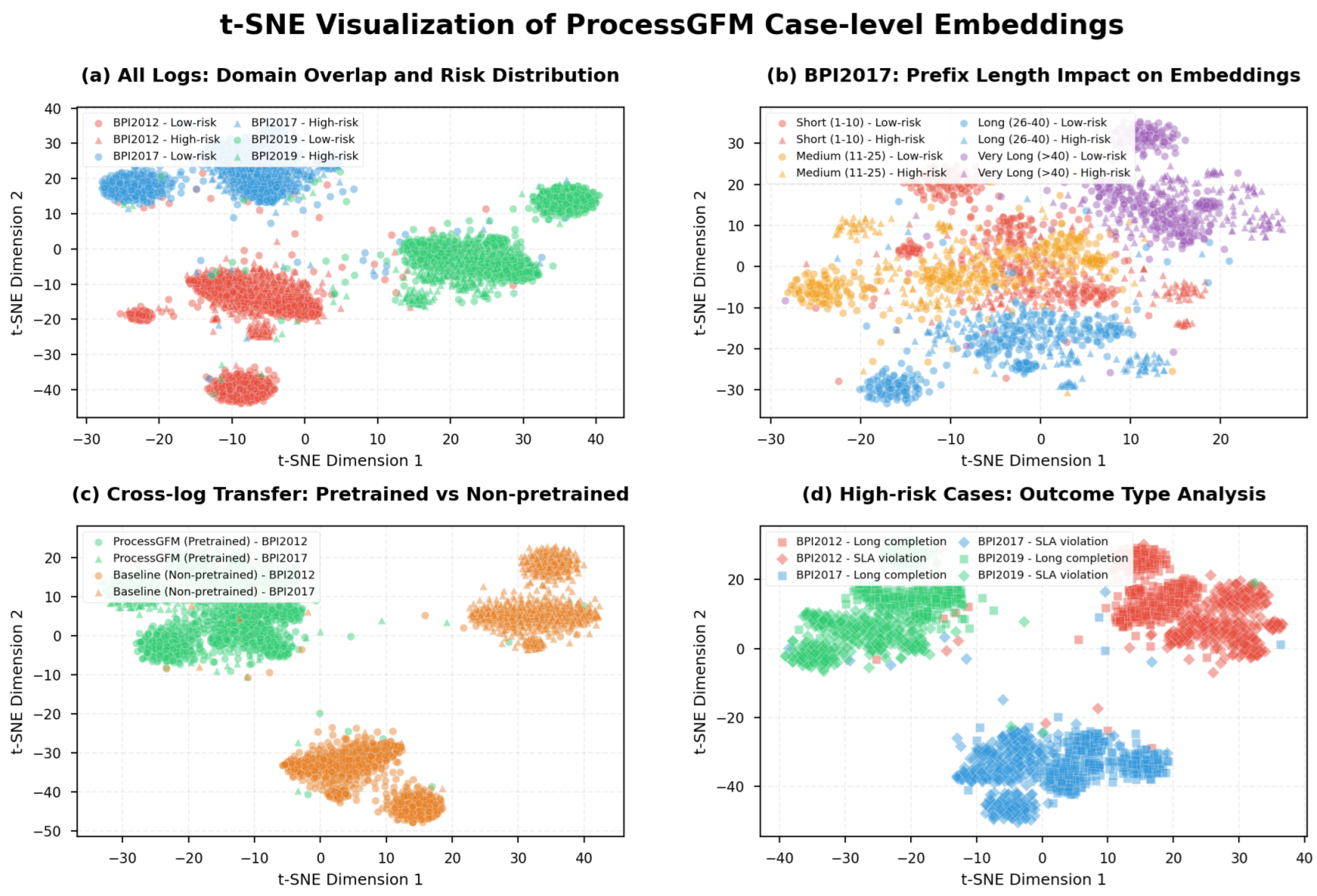

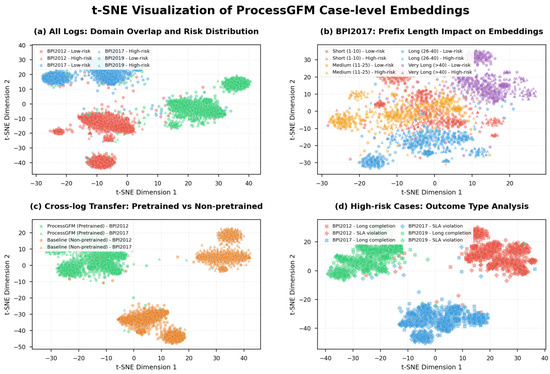

Figure 7 provides an additional perspective by visualising case-level embeddings from ProcessGFM using two-dimensional t-SNE. Embeddings from BPI2012, BPI2017, and BPI2019 are plotted together and coloured by log. The clusters for different logs partially overlap, and within each log, high-risk and low-risk cases form discernible subclusters, suggesting that the backbone organises cases in a way that reflects both domain and outcome while preserving common structure.

Figure 7.

t-SNE projection of case-level embeddings produced by ProcessGFM for a sample of 2000 cases from each log. Points are coloured by log and shaped by risk label.

6.5. Effect of Pretraining Corpus Size

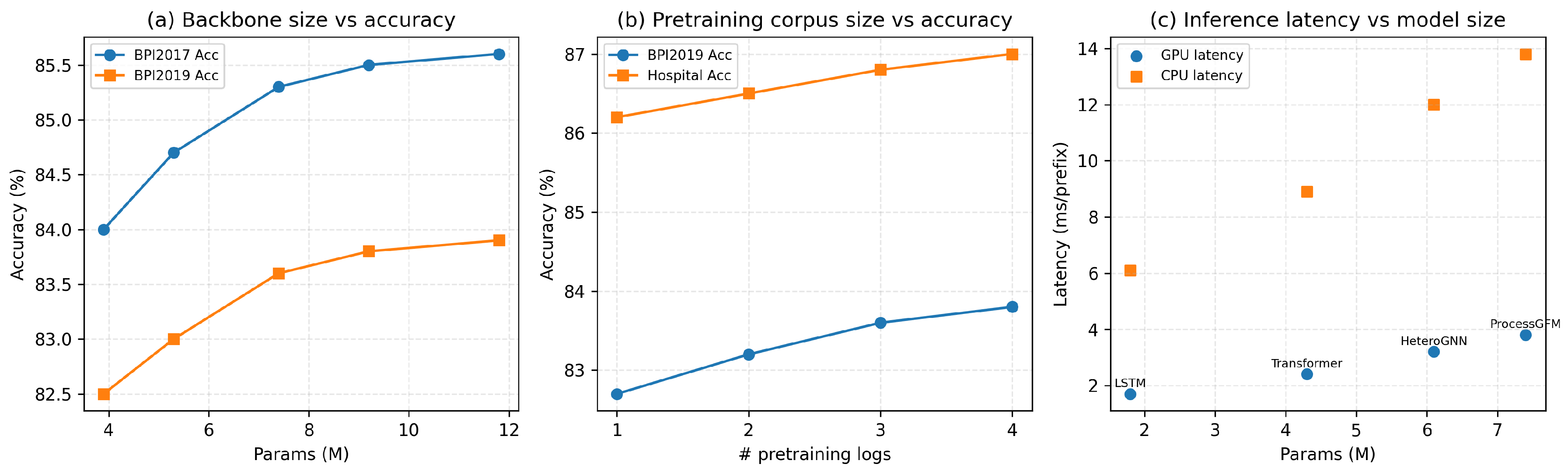

To investigate how the size of the pretraining corpus influences downstream performance, we compare four configurations. In , the backbone is pretrained only on BPI2017; in , it is pretrained on BPI2012 and BPI2017; in , it is pretrained on BPI2012, BPI2017, and BPI2019; and in , it is pretrained on all four logs (our default setting). In all cases, the same multi-task head and fine-tuning procedure are used on BPI2019 and the hospital log.

Enlarging the pretraining corpus yields consistent but moderate gains in downstream accuracy on both BPI2019 and Hospital. Increasing the number of logs from one to three leads to a clear improvement, while adding the fourth log brings additional but smaller gains, suggesting a saturating scaling curve. This behaviour is in line with the intuition that pretraining on a broader set of processes provides more robust graph representations, while also illustrating that our study operates at a moderate scale compared with universal graph foundation models trained on orders of magnitude more graphs. Complete scores, including AUC values, are reported in Table A7 in the appendix.

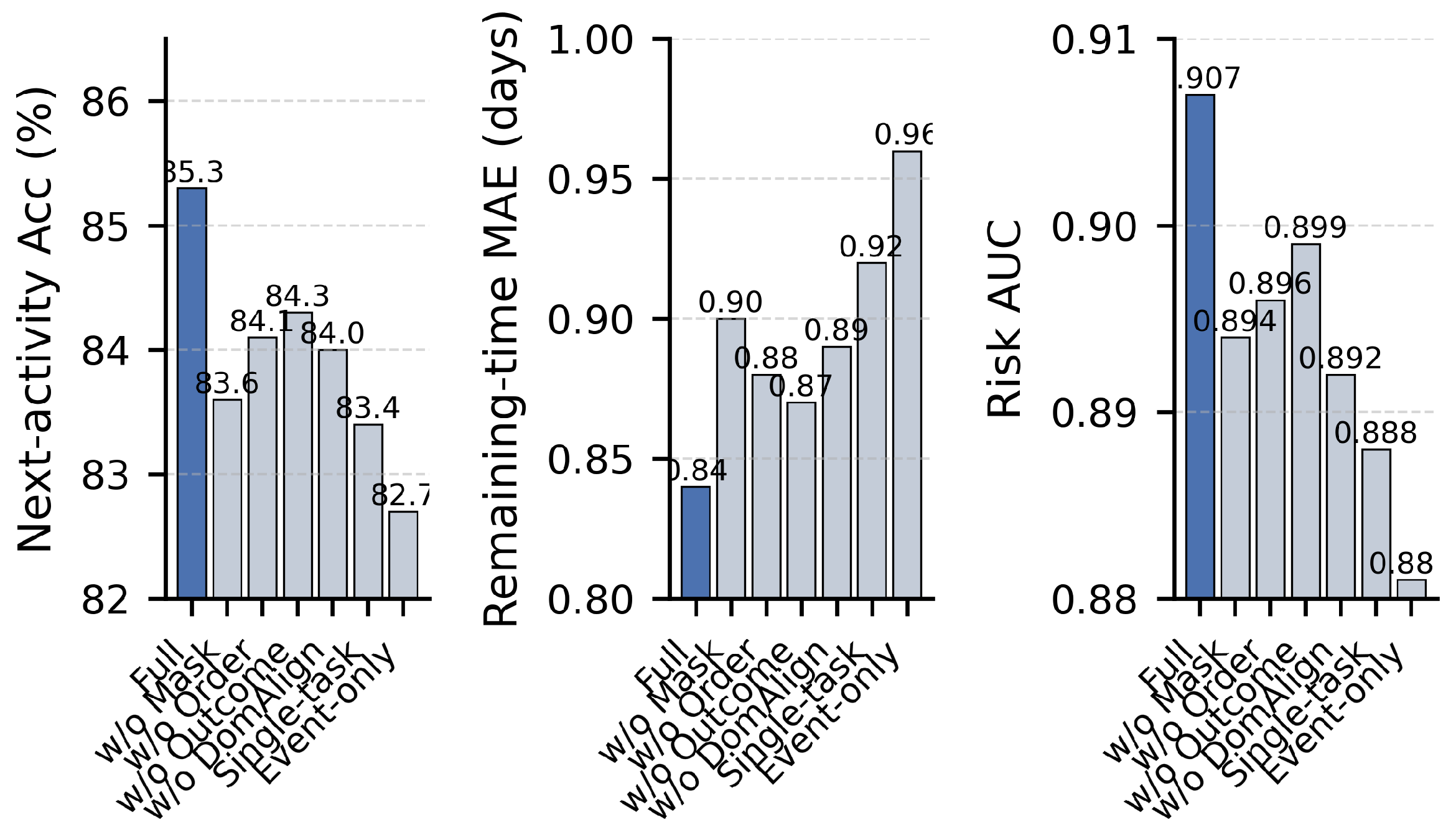

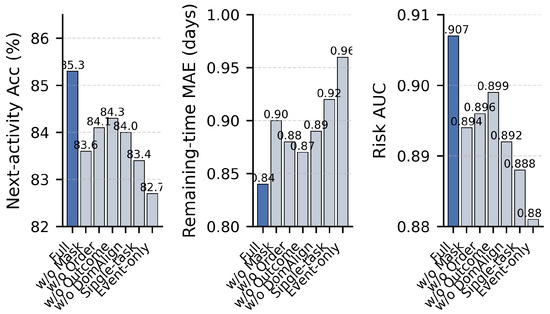

6.6. Ablation Study

To understand the contribution of each component of ProcessGFM, we conduct an ablation study on BPI2017. Table 10 reports next-activity accuracy, remaining-time MAE, and risk AUC for variants where we remove one component at a time.

Table 10.

Ablation study on BPI2017. “Full” denotes the complete ProcessGFM model.

Removing any self-supervised objective degrades performance. Masked activity reconstruction appears particularly important for next-activity accuracy, while temporal order consistency and pseudo outcome prediction mainly benefit remaining-time and risk prediction. Eliminating the domain alignment module reduces cross-log transfer performance even more strongly than in-domain metrics. Using separate single-task heads instead of a multi-task head also harms all three tasks, confirming that shared representations help. The largest drop occurs when removing case and resource nodes and using an event-only graph, which emphasises the value of the hierarchical representation.

In addition to these component-wise ablations, we analyse how the strength of the self-supervised objectives affects downstream performance by varying the pretraining loss weights. Full numerical values are listed in Table A8 and Table A9 in Appendix B. Using only masked activity reconstruction yields the weakest results, while adding either temporal order or pseudo-outcome prediction clearly improves all three metrics. The configuration provides a strong overall trade-off and coincides with the best or near-best performance across tasks, but neighbouring settings such as and differ by at most about one percentage point in accuracy and by less than 0.05 days in MAE. This pattern suggests that all three self-supervised tasks are beneficial and that ProcessGFM is robust to moderate variations in their relative weighting.

Our sensitivity analysis indicates that ProcessGFM remains robust to moderate variations of the pretraining and alignment weights, suggesting that a simple manual setting is feasible for the current multi-log benchmark. However, manual selection may still be suboptimal when transferring to unseen processes with different control-flow complexity, resource heterogeneity, or outcome characteristics. A promising direction is to develop adaptive hyperparameter tuning mechanisms that automatically balance heterogeneous self-supervised objectives and domain alignment during training, for example via gradient- or uncertainty-aware loss balancing and stage-wise curricula. Such adaptive loss balancing has shown benefits in related structured learning settings and may be particularly valuable for event-graph pretraining with diverse logs [42,43].

Figure 8 visualises the ablation results as a bar chart with three panels for the three metrics. The full model consistently achieves the best scores, while the event-only variant is notably weaker.

Figure 8.

Ablation study visualisation for BPI2017.

Figure 9 complements Figure 8 by visualising how the self-supervised loss weights and domain alignment strength affect next-activity accuracy, remaining-time MAE, and risk AUC on BPI2017 and BPI2019.

Figure 9.

Hyperparameter sensitivity and stability. Subplot (a) shows BPI2017 next-activity accuracy as a function of and ; (b) shows the corresponding risk AUC; (c) plots the effect of on in-domain and cross-log performance between BPI2017 and BPI2019; and (d) replicates the accuracy heatmap on BPI2019.

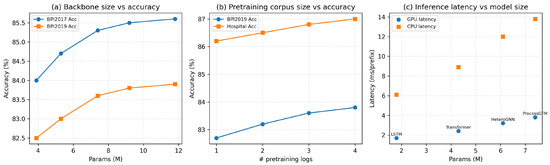

6.7. Backbone Size and Training Cost

We further examine how the size of the ProcessGFM backbone affects performance and computational cost. Figure 10a plots next-activity accuracy on BPI2017 and BPI2019 as a function of the number of parameters for a family of backbones ranging from 3.9 M to 11.8 M parameters. As the model grows from Small to Large, accuracy on both logs increases monotonically but with diminishing marginal gains, while pretraining time grows almost linearly, indicating a clear trade-off between performance and efficiency. Complete numerical results, including MAE and AUC values, are reported in Table A6 in Appendix B.

Figure 10.

Trade-off between model scale, pretraining corpus size, and inference efficiency. Subplot (a) shows the effect of ProcessGFM backbone size on BPI2017 and BPI2019 next-activity accuracy. Subplot (b) illustrates how the number of logs used for self-supervised pretraining affects downstream accuracy on BPI2019 and the Hospital log. Subplot (c) compares GPU and CPU inference latency for different model types and parameter budgets.

6.8. Inference Cost and Deployability

We also measure the inference latency of all models on BPI2019. Figure 10c relates GPU and CPU latency to the parameter budget for LSTM, Transformer, HeteroGNN and ProcessGFM. As expected, the LSTM baseline is the fastest with the smallest parameter budget, while ProcessGFM occupies the upper-right corner of the plot with the highest accuracy but still moderate GPU latency around 3.8 ms per prefix. On CPU, latency increases for all models but remains within a range that is compatible with near real-time monitoring. Detailed GPU/CPU latencies and throughput are reported in Table A4 in Appendix B. In all cases, heterogeneous graphs are constructed offline from the event logs; for streaming scenarios, the graph can be updated incrementally as events arrive, so graph construction is not on the critical path of online prediction.

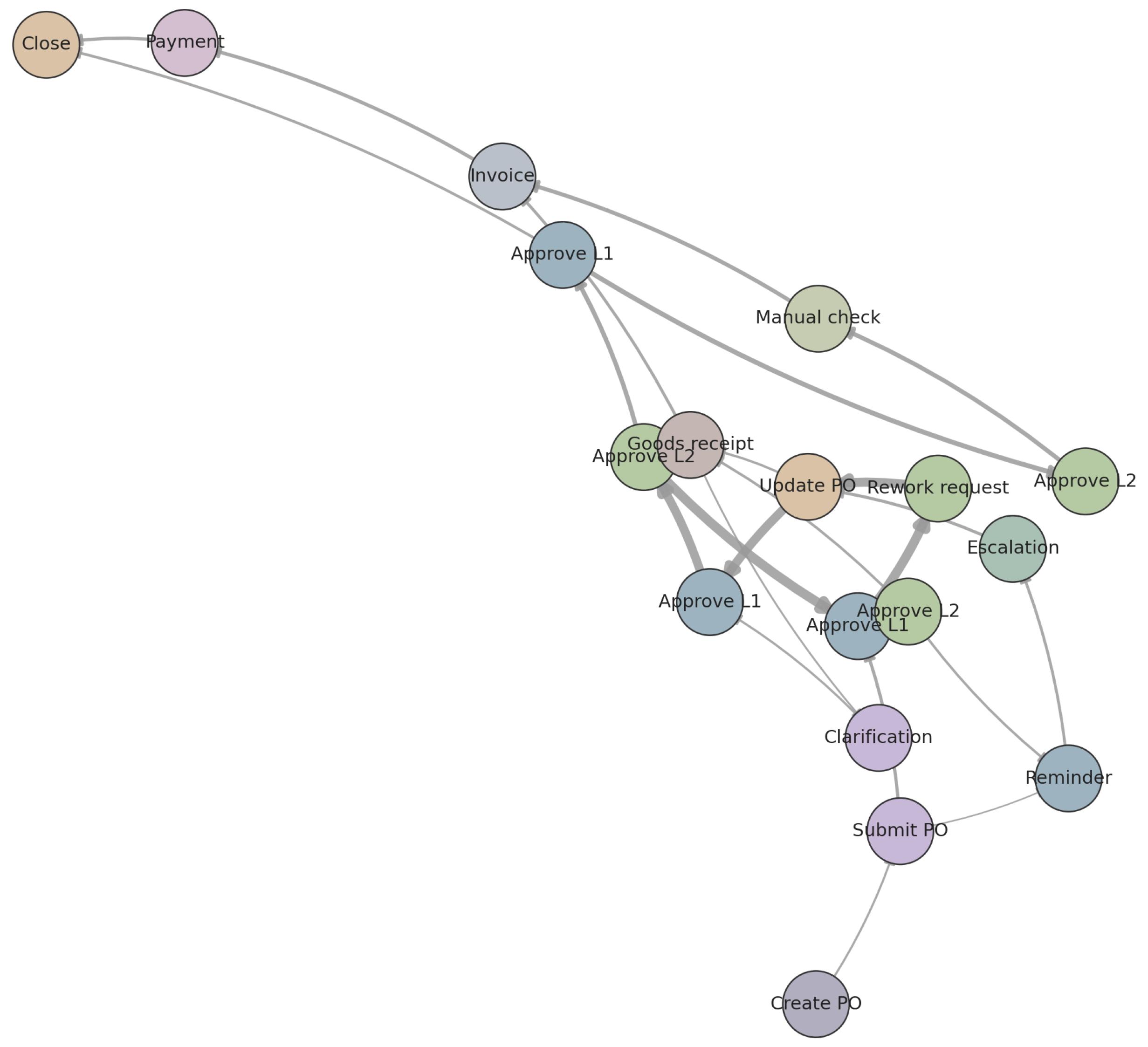

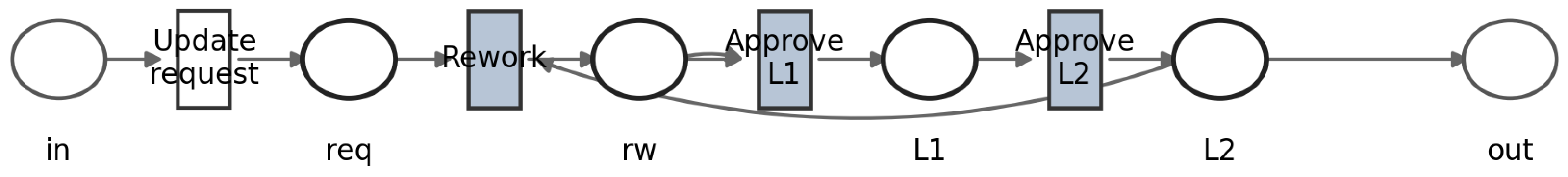

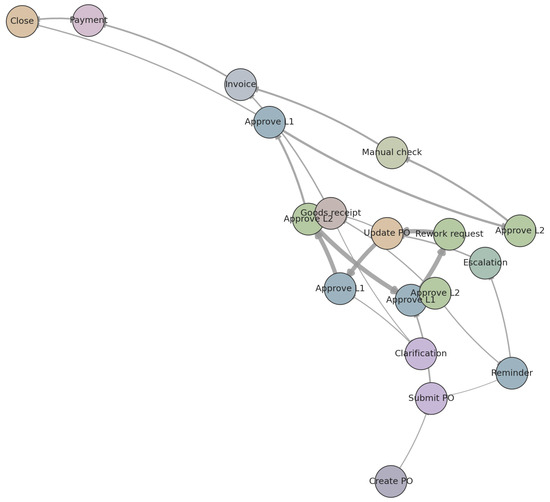

6.9. Interpretability and Case Study

To illustrate how ProcessGFM links graph patterns to predictions, we examine a late case from BPI2019 with a completion time in the 95th percentile. Figure 11 shows the subgraph induced by this case in a directly follows graph, with node colours indicating activity types and edge thickness proportional to attention weights assigned by ProcessGFM during remaining-time prediction. The model focuses on a sequence of repeated change and approval activities involving the same resource cluster, which corresponds to a rework loop identified in process discovery [23].

Figure 11.

Subgraph of the directly follows graph for a late case in BPI2019. Node colours represent activities, and edge thickness corresponds to normalised attention weights from ProcessGFM.

Mapping high-attention edges back to Petri net fragments reveals that the model concentrates on transitions known to cause bottlenecks. Figure 12 displays a Petri net fragment with highlighted transitions and places. This correspondence suggests that the attention mechanism learns to identify structural causes of delay and supports explanation to process analysts.

Figure 12.

Petri net fragment corresponding to the subgraph in Figure 11. Transitions mapped from high-attention edges are shaded, and incident places are outlined. Quantitative analysis shows that paths traversing this fragment have an average remaining time of 5.8 days compared with 2.3 days for other paths.

7. Discussion

The experiments demonstrate that ProcessGFM achieves consistent improvements over strong baselines across three predictive monitoring tasks and multiple real-life event logs. The gains are larger for complex logs with many activities, long traces, and heterogeneous resources, which aligns with the intuition that graph structure and cross-log pretraining deliver greater benefits when event behaviour is highly variable. The results also suggest that large graph pretraining models can meaningfully shift process mining from log-specific architectures toward more unified graph-based representations capable of supporting broad generalisation.

From a methodological perspective, several observations emerge. First, domain-specific self-supervised pretraining tasks that exploit both control-flow dependencies and temporal regularities clearly strengthen downstream performance. The three objectives employed in ProcessGFM contribute complementary information: masked activity reconstruction captures local behavioural patterns, temporal order consistency enforces sensitivity to execution constraints, and pseudo-labelled outcomes encourage global case-level discrimination. Their combined effect indicates that the structure of event logs is sufficiently rich to support large-scale representation learning beyond traditional token-level objectives, and the loss-weight sensitivity analysis in Figure 9a,b,d (with full numerical values in Table A8 and Table A9 in Appendix B) shows that these benefits are stable across a reasonable range of pretraining weight configurations. Second, modelling events, cases, and resources within a single hierarchical graph proves advantageous. This design allows the backbone to integrate short-range event transitions with longer-range case evolution and contextualise them through resource interactions, producing embeddings that are not easily replicated by models confined to a single representational layer. The ablation study shows that removing any of these components degrades performance, with the largest impact observed when the model is restricted to event-only graphs.

Domain alignment strengthens cross-log robustness even when differences in activity vocabularies or organisational structures are substantial. By discouraging the backbone from encoding log-specific artefacts, the adversarial module improves stability across logs and reduces the need for per-log fine-tuning. This is particularly relevant in practical deployments where organisations may wish to train a model once and reuse it across multiple processes.

Despite these strengths, several limitations remain. The experimental logs, while diverse, are all derived from structured administrative processes with relatively clear control-flow patterns. It is plausible that more irregular settings such as customer service interactions, object-centric manufacturing logs, or multi-entity event streams may pose additional challenges, especially where entities are loosely coupled or events occur asynchronously.

Furthermore, while the pretraining corpus spans multiple years of public benchmarks, its scale remains modest compared with emerging graph foundation models trained on millions of graphs. Incorporating larger corpora, including semi-synthetic or augmented data, may enable further gains and better capture rare behavioural patterns. The pretraining scale ablation in Table A7 and the hyperparameter study in Figure 9 indicate that enlarging the corpus from one to four logs yields consistent but gradual improvements and that performance is stable across a reasonable range of self-supervised and alignment weights, which supports viewing ProcessGFM as a moderate-scale, domain-specific prototype rather than a universal model. Another limitation concerns interpretability. Attention-based visualisation provides a useful indication of which subgraphs influence model predictions, yet these explanations remain heuristic and depend on internal weighting mechanisms. Integrating the learned graph representations with formal conformance checking, structural simplification, or region-based process discovery could lead to more rigorous, semantically grounded interpretability. Finally, although ProcessGFM performs well on zero-shot transfer across similar domains, entirely new processes with radically different vocabularies or execution cultures may still require adaptation strategies tailored to open-world settings.

An additional asymmetry arises when considering the synthetic Hospital log. ProcessGFM attains strong in-domain risk prediction performance on both BPI2019 (AUC 0.912) and Hospital (0.921), yet transferring from the real BPI2019 log to Hospital yields a slightly lower AUC (0.894) than transferring in the opposite direction (0.902; Table A3). We attribute this behaviour to the “clean” and simplified control-flow of the synthetic benchmark, which does not fully reflect the noise, exceptional behaviour, and irregular resource usage patterns present in the real logs. Representations learned from real logs must account for such irregularities and therefore do not align perfectly with the more regular synthetic behaviour, whereas representations learned on the synthetic log focus on generic patterns that still carry over to real logs. The domain alignment module mitigates, but does not completely remove, this distribution shift, which we consider an interesting direction for future work on robustness across synthetic and real-world benchmarks.

Overall, the findings suggest that ProcessGFM represents a meaningful step toward more general, transferable, and structurally aware predictive monitoring models. The results indicate that combining hierarchical graph reasoning, targeted self-supervision, and domain alignment offers a viable pathway for future research aiming to bridge the gap between traditional process modelling and modern graph representation learning. In addition, adaptive loss balancing and automated hyperparameter scheduling may further reduce manual tuning and improve robustness across processes with heterogeneous control-flow structure and outcome distributions.

8. Conclusions

This paper has introduced ProcessGFM, a domain-specific graph pretraining prototype for predictive process monitoring on event graphs. The model combines a hierarchical graph backbone that integrates event-level, case-level, and resource-level information with self-supervised pretraining, multi-task adaptation, and adversarial domain alignment. Evaluations on three BPI logs and a hospital log show that ProcessGFM improves next-activity prediction, remaining-time estimation, and risk classification compared with strong sequence-based and graph-based baselines. It also demonstrates robust cross-log transfer and provides interpretable insights by highlighting process fragments associated with delay and risk.

Future work includes extending ProcessGFM to object-centric event logs and multi-process settings, integrating text attributes through joint training with language models, and exploring more scalable pretraining regimes inspired by universal graph foundation models. Another promising direction is to couple ProcessGFM with automated process improvement techniques, where the model not only predicts outcomes but also suggests interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and J.L.; methodology, Y.H. and Z.T.; software, X.Z. and Y.L.; validation, Y.H., J.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, Y.H., J.L. and Z.T.; investigation, Y.H. and J.L.; resources, Z.T. and Z.L.; data curation, Y.L. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., Y.L., Z.T. and Z.L.; visualization, X.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, Z.T. and Z.L.; project administration, Z.T. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 20BJL122).

Data Availability Statement

The BPI Challenge 2012, 2017 and 2019 event logs used in this study are openly available from 4TU.ResearchData under the persistent DOIs https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:3926db30-f712-4394-aebc-75976070e91f, https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:5f3067df-f10b-45da-b98b-86ae4c7a310b and https://doi.org/10.4121/uuid:d06aff4b-79f0-45e6-8ec8-e19730c248f1, respectively. The hospital event log used for additional experiments is publicly available through the real-world XES event log collection at https://www.tf-pm.org/resources/xes-standard/about-xes/event-logs (accessed on 9 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Implementation Details

All models are implemented in PyTorch (2.9.0) and PyTorch Geometric (2.6), and trained on a single GPU-class device. For ProcessGFM, we use eight message-passing layers with hidden dimension 128, three attention heads per relation type, and dropout rate 0.2. Self-supervised loss weights are set to 1.0 for masked activity reconstruction, 0.5 for temporal order consistency, and 0.5 for pseudo outcome prediction. During pretraining, we mask 15% of event activities and shuffle subsequences of length between four and eight events.

Baselines are implemented following publicly available benchmark code for predictive monitoring [36]. The LSTM model uses two layers with hidden dimension 128. The Transformer model uses four encoder layers with eight attention heads and positional trace encoding. The GGSNN operates on directly follows graphs constructed from each log. The HeteroGNN PPM baseline uses event, case, and resource nodes but without cross-log pretraining or domain alignment.

Table A1.

Hyperparameter search ranges and selected values for ProcessGFM. # denotes the number of message-passing layers.

Table A1.

Hyperparameter search ranges and selected values for ProcessGFM. # denotes the number of message-passing layers.

| Hyperparameter | Values Tried | Selected Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hidden dimension | 128 | |

| Number of message-passing layers | 8 | |

| Dropout rate | 0.2 | |

| Backbone learning rate | ||

| Head learning rate | ||

| Batch size | 64 |

Appendix B. Additional Metrics

Table A2 reports macro recall and macro precision for next-activity prediction on the three BPI logs. These metrics complement the macro-F1 scores in Table 4.

Table A2.

Macro recall and macro precision for next-activity prediction.

Table A2.

Macro recall and macro precision for next-activity prediction.

| BPI2012 | BPI2017 | BPI2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Macro Rec (%) | Macro Prec (%) | Macro Rec (%) | Macro Prec (%) | Macro Rec (%) | Macro Prec (%) |

| LSTM baseline | 79.4 | 80.8 | 73.7 | 75.5 | 70.5 | 72.0 |

| Transformer baseline | 80.9 | 82.1 | 75.9 | 77.9 | 72.9 | 74.3 |

| GGSNN (DFG) | 81.5 | 82.6 | 76.4 | 78.1 | 73.3 | 74.7 |

| HeteroGNN PPM | 82.7 | 83.7 | 77.2 | 79.0 | 74.5 | 75.8 |

| ProcessGFM (ours) | 86.3 | 87.9 | 81.6 | 83.2 | 79.7 | 81.9 |

Table A3.

Cross-log risk prediction AUC between real logs and the synthetic Hospital log.

Table A3.

Cross-log risk prediction AUC between real logs and the synthetic Hospital log.

| Train\Test | BPI2019 | Hospital | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPI2019 (in-domain) | 0.912 | – | ProcessGFM |

| Hospital (in-domain) | – | 0.921 | ProcessGFM |

| BPI2019 → Hospital | – | 0.894 | real-to-synthetic |

| Hospital → BPI2019 | 0.902 | – | synthetic-to-real |

Table A4.

Inference cost on BPI2019. Latency is averaged over 10,000 prefixes with batch size 256. Graph construction is performed offline.

Table A4.

Inference cost on BPI2019. Latency is averaged over 10,000 prefixes with batch size 256. Graph construction is performed offline.

| Model | GPU Latency (ms/Prefix) | GPU Prefixes/s | CPU Latency (ms/Prefix) | CPU Prefixes/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM baseline | 1.7 | 588 | 6.1 | 164 |

| Transformer baseline | 2.4 | 417 | 8.9 | 112 |

| HeteroGNN PPM | 3.2 | 312 | 12.0 | 83 |

| ProcessGFM (ours) | 3.8 | 263 | 13.8 | 72 |

| Graph construction (offline) | ≈42 s (entire log) | ≈42 s (entire log) | ||

Table A5.

Cross-log remaining-time and risk prediction when training on BPI2017 and testing on BPI2019.

Table A5.

Cross-log remaining-time and risk prediction when training on BPI2017 and testing on BPI2019.

| Model | MAE (In-Domain) | MAE (Cross-Log) | Risk AUC (In-Domain) | Risk AUC (Cross-Log) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeteroGNN PPM | 2.39 | 2.65 | 0.862 | 0.842 |

| ProcessGFM | 2.11 | 2.28 | 0.912 | 0.901 |

Table A6.

Effect of ProcessGFM backbone size on performance and training cost (complete results corresponding to Figure 10a).

Table A6.

Effect of ProcessGFM backbone size on performance and training cost (complete results corresponding to Figure 10a).

| Config | Params (M) | Pretrain (h) | BPI2017 Acc (%) | BPI2017 MAE | BPI2017 AUC | BPI2019 Acc (%) | BPI2019 MAE | BPI2019 AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96, 6 layers | 6.4 | 5.3 | 84.0 | 0.88 | 0.900 | 82.4 | 2.19 | 0.905 |

| 128, 8 layers | 8.7 | 7.5 | 85.3 | 0.84 | 0.907 | 83.7 | 2.11 | 0.912 |

| 160, 10 layers | 11.2 | 10.1 | 85.5 | 0.83 | 0.909 | 83.9 | 2.08 | 0.913 |

Table A7.

Effect of pretraining corpus size on downstream performance (complete results corresponding to Figure 10b).

Table A7.

Effect of pretraining corpus size on downstream performance (complete results corresponding to Figure 10b).

| Setting | BPI2019 Acc (%) | BPI2019 AUC | Hospital Acc (%) | Hospital AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1: BPI2017 only | 82.7 | 0.896 | 86.2 | 0.911 |

| P2: BPI2012+2017 | 83.2 | 0.900 | 86.5 | 0.913 |

| P3: BPI2012+2017+2019 | 83.6 | 0.903 | 86.8 | 0.915 |

| P4: BPI2012+2017+2019+Hospital (synt.) | 83.8 | 0.904 | 87.0 | 0.916 |

Table A8.

Sensitivity of self-supervised loss weights on BPI2017.

Table A8.

Sensitivity of self-supervised loss weights on BPI2017.

| Acc (%) | MAE (Days) | Risk AUC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 83.1 | 0.91 | 0.892 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 84.3 | 0.88 | 0.899 |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 84.2 | 0.87 | 0.901 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 85.3 | 0.84 | 0.907 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 85.1 | 0.85 | 0.905 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 85.0 | 0.83 | 0.909 |

Table A9.

Sensitivity of self-supervised loss weights on BPI2019.

Table A9.

Sensitivity of self-supervised loss weights on BPI2019.

| Acc (%) | MAE (Days) | Risk AUC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 81.9 | 2.26 | 0.894 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 82.6 | 2.21 | 0.901 |

| 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 82.5 | 2.18 | 0.904 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 83.7 | 2.11 | 0.912 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 83.4 | 2.13 | 0.910 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 83.3 | 2.07 | 0.915 |

Table A10.

Effect of domain alignment strength on BPI2017 and cross-log transfer to BPI2019.

Table A10.

Effect of domain alignment strength on BPI2017 and cross-log transfer to BPI2019.

| (%) | (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 84.0 | 0.892 | 77.3 | 0.886 |

| 0.1 | 84.6 | 0.898 | 78.5 | 0.892 |

| 0.3 | 85.0 | 0.903 | 79.0 | 0.899 |

| 0.5 | 85.3 | 0.907 | 79.1 | 0.901 |

| 0.7 | 85.1 | 0.905 | 78.8 | 0.900 |

| 1.0 | 84.2 | 0.895 | 77.0 | 0.887 |

Appendix C. Dataset Splits

Table A11 shows the number of cases in the training, validation, and test splits for each log.

Table A11.

Number of cases per split for each log.

Table A11.

Number of cases per split for each log.

| Log | Train | Validation | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPI2012 | 9161 | 1309 | 2 617 |

| BPI2017 | 22,056 | 3151 | 6302 |

| BPI2019 | 176,213 | 25,173 | 50,348 |

| Hospital | 7000 | 1000 | 2000 |

References

- Chapela-Campa, D.; Dumas, M. From Process Mining to Augmented Process Execution. Softw. Syst. Model. 2023, 22, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo, P.; Comuzzi, M.; De Weerdt, J.; Di Francescomarino, C.; Maggi, F.M. Predictive Process Monitoring: Concepts, Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Process Sci. 2024, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; van der Aalst, W.M. Action-Oriented Process Mining: Bridging the Gap between Insights and Actions. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibakhshi, A.; Hassannayebi, E. Towards an Enhanced next Activity Prediction Using Attention Based Neural Networks. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, W.; Guo, N.; Song, R.; Gu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zeng, Q. Comparative Evaluation of Encoding Techniques for Workflow Process Remaining Time Prediction for Cloud Applications. J. Cloud Comput. 2025, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeperkorn, J.; vanden Broucke, S.; De Weerdt, J. Can Recurrent Neural Networks Learn Process Model Structure? J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2023, 61, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, H.; Metsis, V. Positional Encoding in Transformer-Based Time Series Models: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemans, S.J.; van Zelst, S.J.; Lu, X. Partial-Order-Based Process Mining: A Survey and Outlook. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2023, 65, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliferis, C.; Simon, G. Overfitting, Underfitting and General Model Overconfidence and under-Performance Pitfalls and Best Practices in Machine Learning and AI. In Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care and Medical Sciences: Best Practices and Pitfalls; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 477–524. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshraftar, S.; An, A. A Survey on Graph Representation Learning Methods. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Saad, M. An Approach to Capturing and Reusing Tacit Design Knowledge Using Relational Learning for Knowledge Graphs. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Mai, N.T.; Liu, W. Adaptive Knowledge Assessment via Symmetric Hierarchical Bayesian Neural Networks with Graph Symmetry-Aware Concept Dependencies. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Yin, D.; Shi, C. Graph Foundation Models for Recommendation: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S. Deep Learning Methods for Molecular Representation and Property Prediction. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, T.; Liu, P.; Ren, Z. Impact of Domain Knowledge and Multi-Modality on Intelligent Molecular Property Prediction: A Systematic Survey. Big Data Min. Anal. 2024, 7, 858–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Lu, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Bai, T.; Fang, Y.; Sun, L.; Yu, P.S.; et al. Towards Graph Foundation Models: A Survey and Beyond. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.; Tjurin, P.; Niemelä, M.; Jämsä, T.; Farrahi, V. Machine-Learning Models for Activity Class Prediction: A Comparative Study of Feature Selection and Classification Algorithms. Gait Posture 2021, 89, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Foumani, N.; Miller, L.; Tan, C.W.; Webb, G.I.; Forestier, G.; Salehi, M. Deep Learning for Time Series Classification and Extrinsic Regression: A Current Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, B.R.; vanden Broucke, S.; De Weerdt, J. A Direct Data Aware LSTM Neural Network Architecture for Complete Remaining Trace and Runtime Prediction. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 2330–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, C.; Dossena, M.; Leonardi, G.; Montani, S. Structural Positional Encoding for Knowledge Integration in Transformer-Based Medical Process Monitoring and Trace Classification. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, Y.; Men, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zou, S. Valorization of Alkali–Thermal Activated Red Mud for High-Performance Geopolymer: Performance Evaluation and Environmental Effects. Buildings 2025, 15, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foumani, N.M.; Tan, C.W.; Webb, G.I.; Salehi, M. Improving Position Encoding of Transformers for Multivariate Time Series Classification. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 38, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, D.; Menkovski, V.; Fahland, D. Process Discovery Using Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Process Mining (ICPM), Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 31 October–4 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Xu, D.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y. Graph Convolutional Network Soft Sensor for Process Quality Prediction. J. Process Control 2023, 123, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Stark, H.; Jegelka, S.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Graph Neural Networks. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Gao, X. Utilisation of Bayer red mud for high-performance geopolymer: Competitive roles of different activators. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, R.; Hu, Q.; Ding, S.X. Interaction-Aware Graph Neural Networks for Fault Diagnosis of Complex Industrial Processes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 6015–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q. Capturing Structural Evolution in Financial Markets with Graph Neural Time Series Models. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Digital Economy, Kunming, China, 18–20 July 2025; pp. 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leoni, M.; Volpato, P. Global Predictive Monitoring of Object-Centric Processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Process Management, Seville, Spain, 31 August–5 September 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquadibisceglie, V.; Scaringi, R.; Appice, A.; Castellano, G.; Malerba, D. PROPHET: Explainable Predictive Process Monitoring with Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2024, 17, 4111–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y. Incorporating Attributes and Multi-Scale Structures for Heterogeneous Graph Contrastive Learning. Inf. Fusion 2025, 122, 103220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, Z.; Subramonian, A.; Sun, Y. Motif-Driven Contrastive Learning of Graph Representations. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 4063–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, R.; Sun, W.; Chen, L.; Tian, S.; Zhu, L.; Meng, C.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, W. What’s behind the Mask: Understanding Masked Graph Modeling for Graph Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 1268–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, R.; Yuan, G.; Zhu, M.; Meng, F.; Ma, H.; Qiao, S. Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks Analysis: A Survey of Techniques, Evaluations and Applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 8003–8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdekis, A.; Kerasiotis, A.; Kotsias, S.; Theodoropoulou, G.; Miaoulis, G.; Ghazanfarpour, D. Modelling and Predictive Monitoring of Business Processes under Uncertainty with Reinforcement Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weytjens, H.; De Weerdt, J. Creating Unbiased Public Benchmark Datasets with Data Leakage Prevention for Predictive Process Monitoring. In Business Process Management Workshops;Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Marrella, A., Weber, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 436, pp. 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciani, A.; Bernardi, M.L.; Cimitile, M.; Marrella, A. Enhancing next Activity Prediction in Process Mining with Retrieval-Augmented Generation. Inf. Syst. 2026, 137, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, N.; Verenich, I.; La Rosa, M.; Dumas, M. Predictive Business Process Monitoring with LSTM Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advanced Information Systems Engineering (CAiSE 2017), Essen, Germany, 12–16 June 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10253, pp. 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicani, A.; Ceci, M. Positional Trace Encoding for next Activity Prediction in Event Logs. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 294, 113544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzierl, S. Exploring Gated Graph Sequence Neural Networks for Predicting next Process Activities. In Business Process Management Workshops;Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Marrella, A., Weber, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 436, pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, W.; Comuzzi, M.; Di Francescomarino, C.; Ghidini, C.; Lee, S.; Maggi, F.M.; Nolte, A. Explainable Predictive Process Monitoring: A User Evaluation. Process Sci. 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y. Hierarchy-Consistent Learning and Adaptive Loss Balancing for Hierarchical Multi-Label Classification. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 10–14 November 2025; pp. 1190–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Zhao, S.; Tang, H.; Zheng, X.; Sun, L.; Luo, Y. Next Point of Interest Recommendation Based on Graph Structure and Sequential Pattern. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).