1. Introduction

Fractional calculus is a branch of mathematics that extends the classic ideas of differentiation and integration by allowing the order of operation to be a non-integer value. Unlike conventional integer-order operators, fractional operators provide the extra degree of freedom required for the exact description of systems whose dynamics are not well expressed by traditional models. During the past ten years, there has been an increasing interest in fractional calculus because of its strong capability in modeling complex real-world phenomena with inherent memory, hereditary characteristics, and anomalous diffusion behaviors. Refs. [

1,

2] represent a further generalization.

Some recent works [

3,

4] illustrate that fractional-order systems are powerful tools in analyzing and simulating a wide variety of physical, biological, and engineering processes. These systems allow better modeling flexibility and precision in those processes where the present state depends not only on current conditions but also on the system’s historical evolution. Such memory-driven dynamics and long-range temporal correlations are at the heart of many applications in viscoelastic materials, biological tissues, epidemiological spread, electrochemical systems, and chaotic dynamical processes [

5,

6]. In this respect, fractional calculus has become one of the most promising and effective approaches to dealing with complex dynamical behaviors that standard integer-order models are unable to reproduce.

One of fractional-order dynamical systems’ most intriguing and remarkable characteristics is their possibility to present chaotic behavior. This property has become fundamental in several practical applications, such as secure communications, cryptographic schemes, advanced signal processing techniques, and mathematical modeling of complex biological processes [

7,

8,

9].

Variable-order fractional derivatives represent a further generalization of the traditional modeling framework, since the differentiation order varies in time, space, or system state. Such dynamic ability yields variable-order models capable of naturally including changing memory effects and non-stationary hereditary behavior throughout the system evolution. For these reasons, variable-order fractional formulations are exceptionally suitable for correctly describing real-world processes from engineering, biological systems, and physical sciences, whose system properties or memory intensity vary over operating conditions [

10,

11,

12]. Compared to systems with constant fractional order, variable-order systems manifest additional modeling flexibility, enabling the modeling of highly complex, time-varying, and irregular patterns—as well as their evolving chaotic dynamics—with far more realism and accuracy [

13,

14]. Therefore, variable-order fractional calculus has come to play an important role as a powerful and indispensable tool of analysis in the study of nonlinear systems that possess dynamic memory, long-range dependence, and complex internal interactions [

15].

In

Table 1, the abbreviations are as follows: Constant Fractional Dynamical System (FDS), Variable Fractional Dynamical System (VFDS), Lyapunov Exponents (LY), Time-Series Analysis (TSER), Novel Chaos (NChaos), Symmetry Analysis (SA), Numerical Simulation (NSIM), Stability Analysis (SAN), Phase Portrait (PHPR), and Bifurcation Analysis (BIF).

The

Figure 1 abstract summarizes the key components of the fractional-order Genesio–Tesi system analysis in this paper. In particular, the central model is analyzed by means of dynamical analysis, investigation of stability, and divergence behavior to provide insight into how fractional dynamics affect the evolution of the system. We have conducted a comparison between constant-order and variable-order formulations, focusing on their influence on numerical solutions and transient responses. In general, from a chaotic perspective, the approach utilizes time series, bifurcation diagrams, and Lyapunov exponents to identify regions of instability and to quantify the complexity of the system. It follows that new patterns of chaos appear, driven by variable-order effects, and in-depth insight into the system’s ability to switch from stable to highly irregular states is attained. Altogether, the scheme in this figure reflects how the use of fractional-order modeling improves understanding of nonlinear behavior within the Genesio–Tesi system and its potential applications to wider chaotic dynamics.

The solution of fractional-order systems unveils their stability characteristics, bifurcation structures, and chaotic behaviors. Some of these fractional-order jerk chaotic models have attracted much interest in the last years due to their rich dynamical features and intensified behaviors for applications in secure communications, signal processing, and control engineering [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This work aims to enhance the understanding of both constant-order and variable-order dynamics, providing new insights into chaos and stability that will increase their potential for real-world applications.

Variable-order fractional systems offer a robust framework for modeling processes whose memory or hereditary traits change over time or space [

22]. This type of model has worked well in a number of real-world situations. For example, viscoelastic materials show memory that changes with age, meaning that the stress–strain relationship changes as the material gets worse [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In anomalous diffusion, the spatial variation of the diffusion order is due to the heterogeneity of porous media [

27,

28]. In biological and epidemiological systems, the strength of memory related to immunity or reinfection may fluctuate over time, rendering variable-order operators more realistic than constant-order ones [

29,

30]. Many engineering control systems also show adaptive memory because of changes in temperature or wear and tear on parts [

31]. These examples show how important it is to study variable-order fractional systems and why they are useful for advanced dynamical analysis.

The major contribution of this work is the comparative study of fractional-order Genesio-Tesi systems by both constant-order and variable-order derivatives. Therefore, this investigation will provide new insights into how variations in fractional order can lead to chaotic dynamics, stability characteristics, and the relationships between bifurcations. In particular, for the first time, this study demonstrates how variable-order behavior enhances our understanding of the impact of time-varying memory effects on the chaotic response of the system, in contrast to previous studies. Variable-order models have demonstrated promise and complement the capabilities of fractional systems, including applications in secure communications, encryption, signal processing, and control. Such a method allows the modeling of more complicated real-life phenomena that naturally exhibit long-memory effects, based on numerical testing and computational analysis. The Fractional Genesio-Tesi system is described in the following way:

subject to initial conditions:

where

,

,

, and

.

The fractional-order Genesio–Tesi system provides a robust analytical tool for examining chaotic dynamics, distinguished by its sensitivity and a more complex nonlinear architecture. Specifically, it demonstrates an improved capacity, relative to the conventional model, to account for memory effects.

The system is governed by the variable-order fractional derivative

, where

denotes the time-dependent order of differentiation. The variable-order fractional Genesio–Tesi system is then described as:

subject to initial conditions:

, where

,

,

, and

.

A key benefit of variable-order derivatives lies in their capacity to offer greater adaptability when modeling systems whose behavior is subject to temporal variation. Unlike the constant-order derivatives, which impose a static memory effect, variable-order formulations enable the memory to evolve in response to the system’s state or external influences. This dynamic adjustment can enhance stability, reduce undesired chaotic responses, and improve adaptability. In summary, such capabilities make variable-order models especially useful in secure communications, signal processing, encryption, and also in engineering or biological systems whose degree of nonlocality evolves with time.

In this work, we perform a comparative study of chaotic dynamics of the fractional-order Genesio–Tesi system for constant-order and variable-order cases. As a modern development, variable-order fractional derivatives allow time or state dependence for the order, which offers a deep insight into how fractional dynamics modifies stability and predictability and induces chaos. Applications of these comparisons in view of more practical modeling, where the memory effect evolves over time, are underlined for variable-order systems that model complex real-world phenomena.

3. Fractional System Algorithms and Their Formulas

In this part, we present the definition and an efficient numerical method for approximating solutions of models with the Liouville-Caputo derivative. In practice, where speed or numerical stability is not in jeopardy, simple schemes such as the Euler method are preferred because of their simplicity in implementation and low computation overhead. Yet, for higher accuracy and when computational power allows it, advanced techniques give superior results in approximating the fractional derivatives, such as the Lagrange two-step interpolation method. These methods therefore effectively bring a balance between accuracy and computational effort, hence being particularly useful in fractional-order analyses that require high precision.

Definition 1 ([

34]).

The Liouville–Caputo (LC) fractional derivative of a function with a constant fractional order is given bywhere the operator is expressed as a convolution between the first derivative of G and a power-law kernel. Definition 2 ([

21]).

The variable-order Liouville–Caputo (LCV) fractional derivative of a function , whose fractional order depends on time, is defined byThis operator generalizes the classical LC derivative by allowing the order of differentiation to evolve with time. Remark 1. It should be noted that the normalization term is itself time-dependent because the fractional order varies with t. Consequently, the Gamma function inherits this temporal variation, i.e., . Using the functional identity , the evolution of is governed directly by the evolution of the order function . This implies that the kernel adapts dynamically in time, modifying the weighting of past states in the integral as changes. Therefore, the LCV operator reflects a variable memory effect controlled by the temporal behaviour of .

Since for the interval , the argument of the Gamma function satisfies , for the range given, the Gamma function is well known to be finite, positive, and free of singularities, since it has no poles on . Hence, is strictly non-zero for all admissible values of , ensuring that the normalization term in the LCV operator is always well defined. This property ensures that the kernel does not introduce numerical or analytical singularities due to the Gamma function itself. Thus, the variable-order Liouville–Caputo derivative possesses stability and mathematical coherence during the process of within the interval .

The smoothness of is essential for the well-posedness and stability of the variable-order fractional derivative. If is continuous and Lipschitz continuous, the kernel varies smoothly, ensuring stable and physically meaningful simulations. Abrupt or discontinuous variations in could lead to singular behavior in the kernel and numerical instability.

This part presents the numerical approximation of solutions, following the approaches outlined in [

17,

19,

21], for systems governed by the Caputo fractional operator. The system under consideration is as follows:

where

denotes one of the fractional-order derivatives introduced in Definition 2, and

represents the initial condition. The time interval

is divided into uniform subintervals with step length

; let

be the numerical approximation of

at

.

3.1. Constant-Order Case

Following the computational procedure given in [

17], the fractional differential Equation (

12) can be expressed as

where

. Evaluating (

13) at

yields

Subtracting (

15) from (

14) gives

Applying Lagrange polynomial interpolation to approximate the integral term leads to the discrete update formula

For the 3D Caputo fractional dynamical model, the component-wise numerical updates read

where

3.2. Variable-Order Case

where

denotes the variable-order fractional derivative with order

depending on time

t.

For the variable-order Caputo derivative, and following the numerical strategy in [

19], we can rewrite (

19) as

Approximating

within each

by a two-point Lagrange interpolant and integrating yields the discrete update scheme

For the variable-order 3D system, the scheme becomes

where

4. Numerical Simulation

In this section, we consider the variable-order cases in the following form to demonstrate three kinds of realistic memory behavior in fractional dynamical systems: Case 1: , Case 2: , and Case 3: . It can be seen that the first two cases add smooth periodic changes to the fractional order, which allows the system to switch slowly between areas of weaker and stronger memory. This models the oscillatory environments or cyclic influences that are often encountered. Case 1 uses a cosine modulation for symmetric changes around the mean, while Case 2 uses a sine modulation with just a bit higher amplitude to test the sensitivity to periodic perturbations with phase shift. Case 3 utilizes a hyperbolic tangent function to introduce a nonperiodic transition of the fractional order. The functions modeled by such a hyperbolic tangent are similar to those including memory variation from one regime to another, as in adaptation or learning, or the accumulation of long-term processes. This technique allows the full evaluation of different types of variable-order law influences, such as periodic, phase-shifted, and transitional, on stability, divergence, and chaotic dynamics onset in the fractional Genesio–Tesi system.

4.1. Chaos Analysis

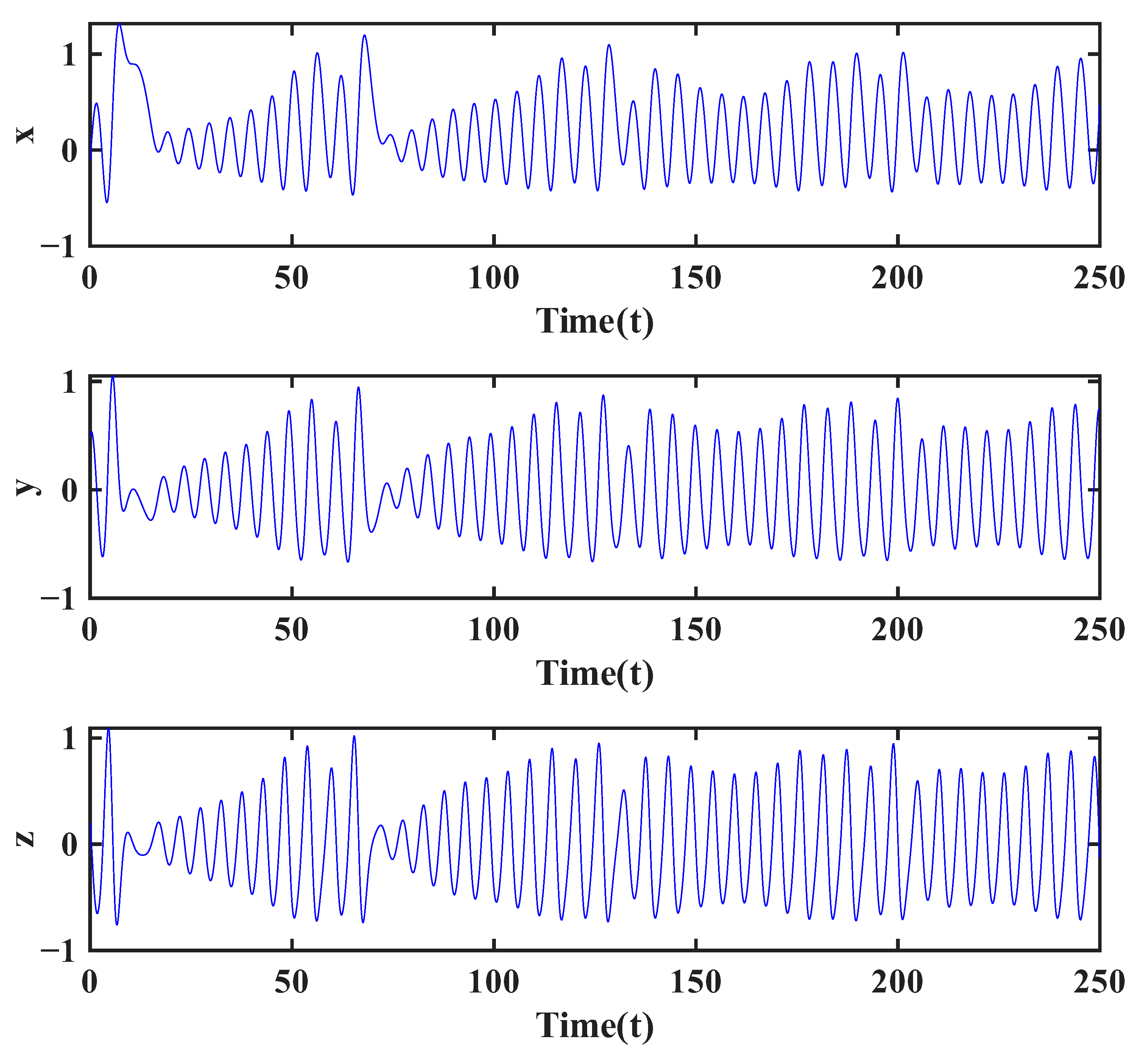

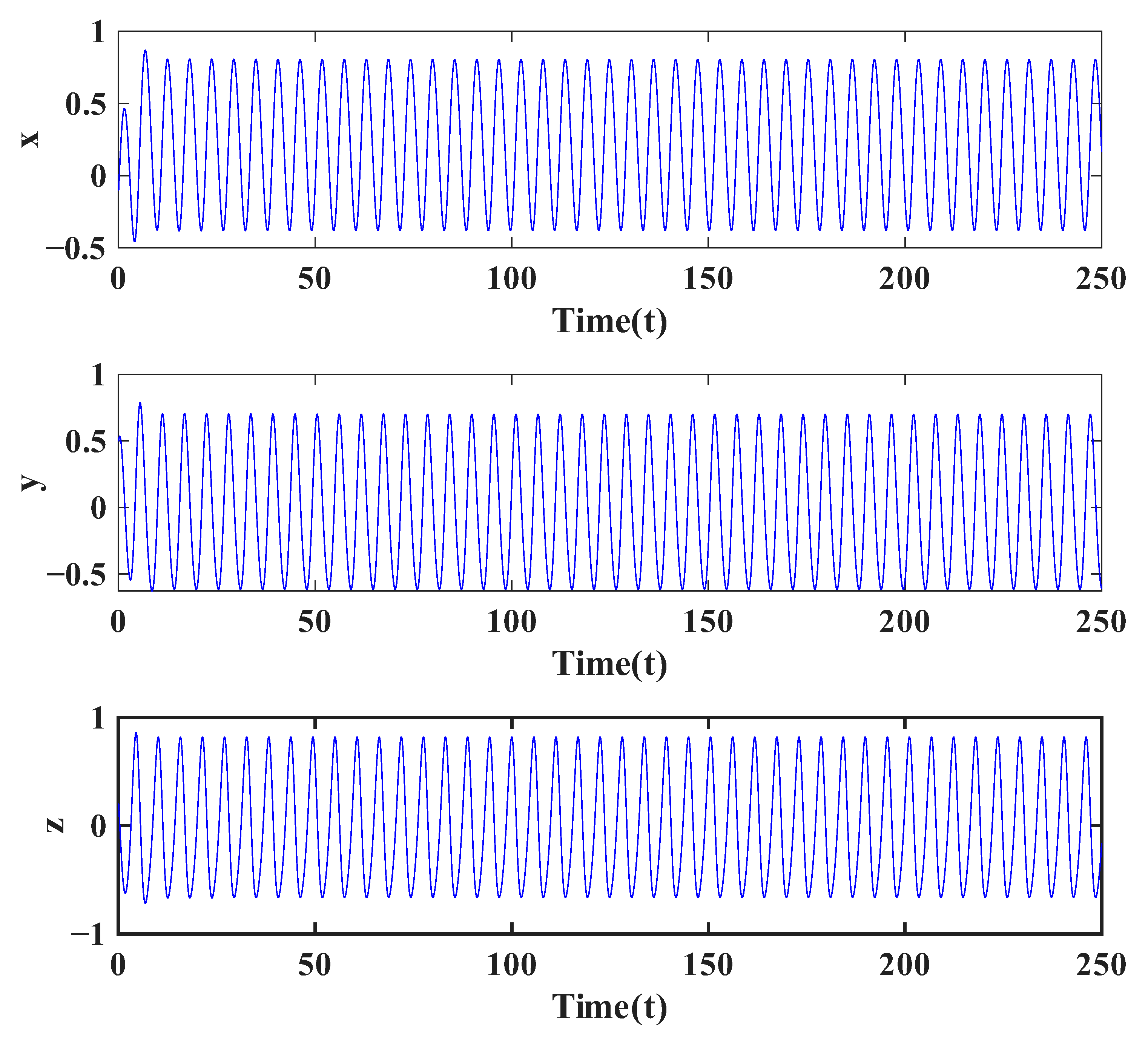

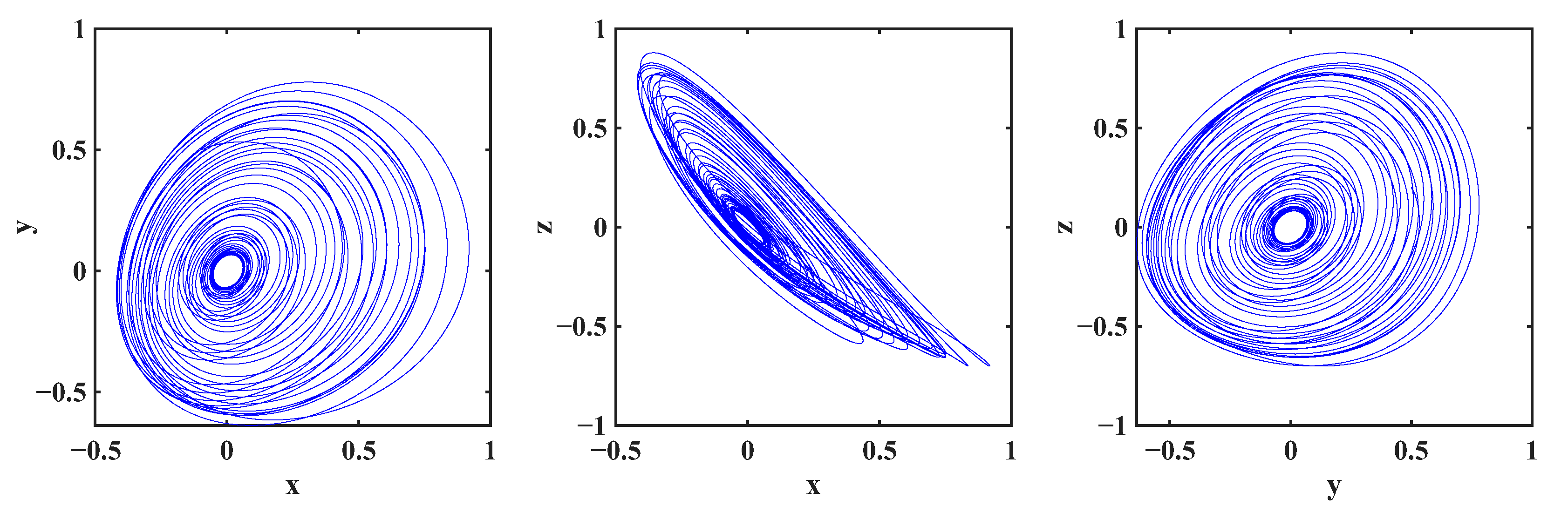

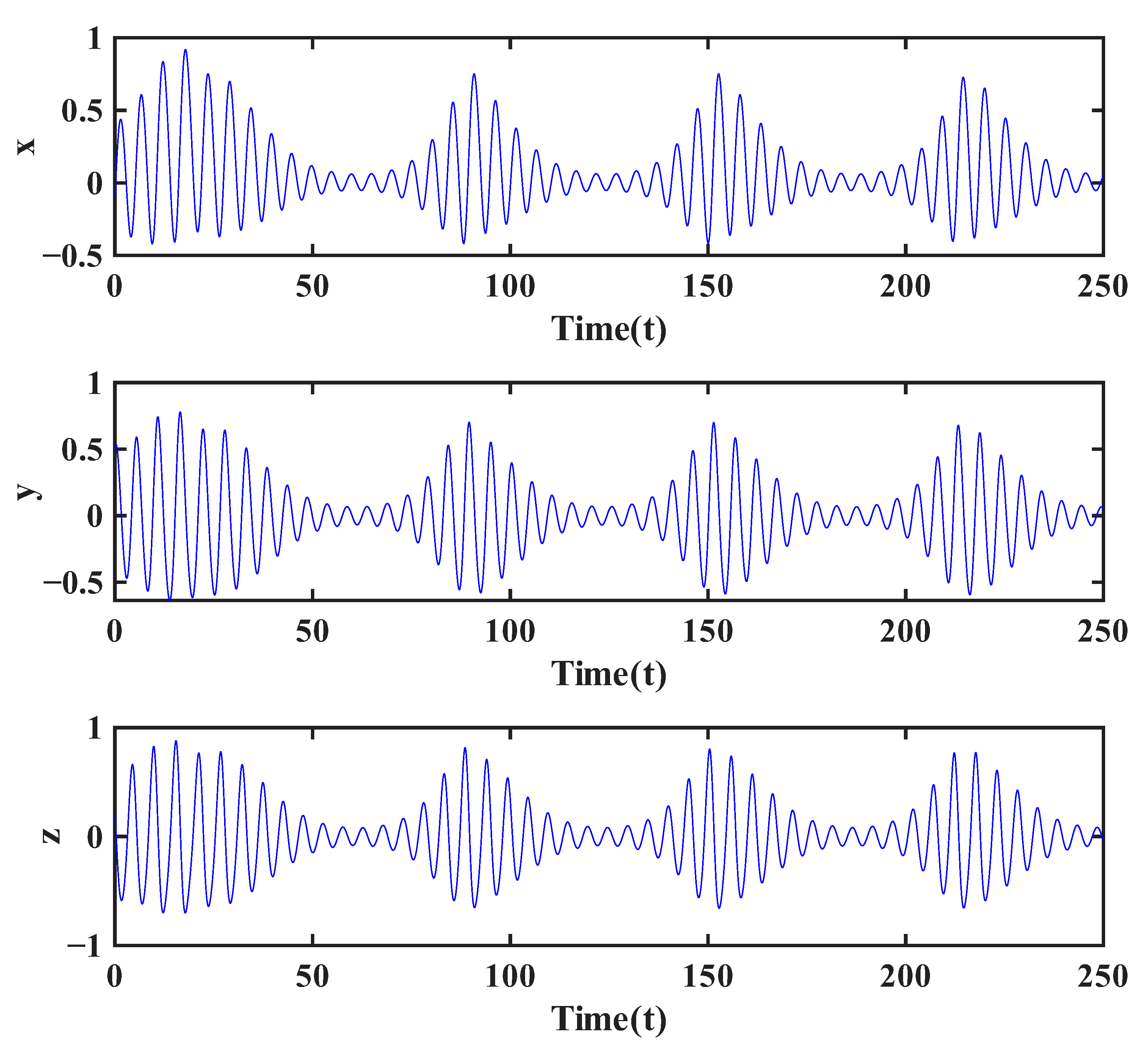

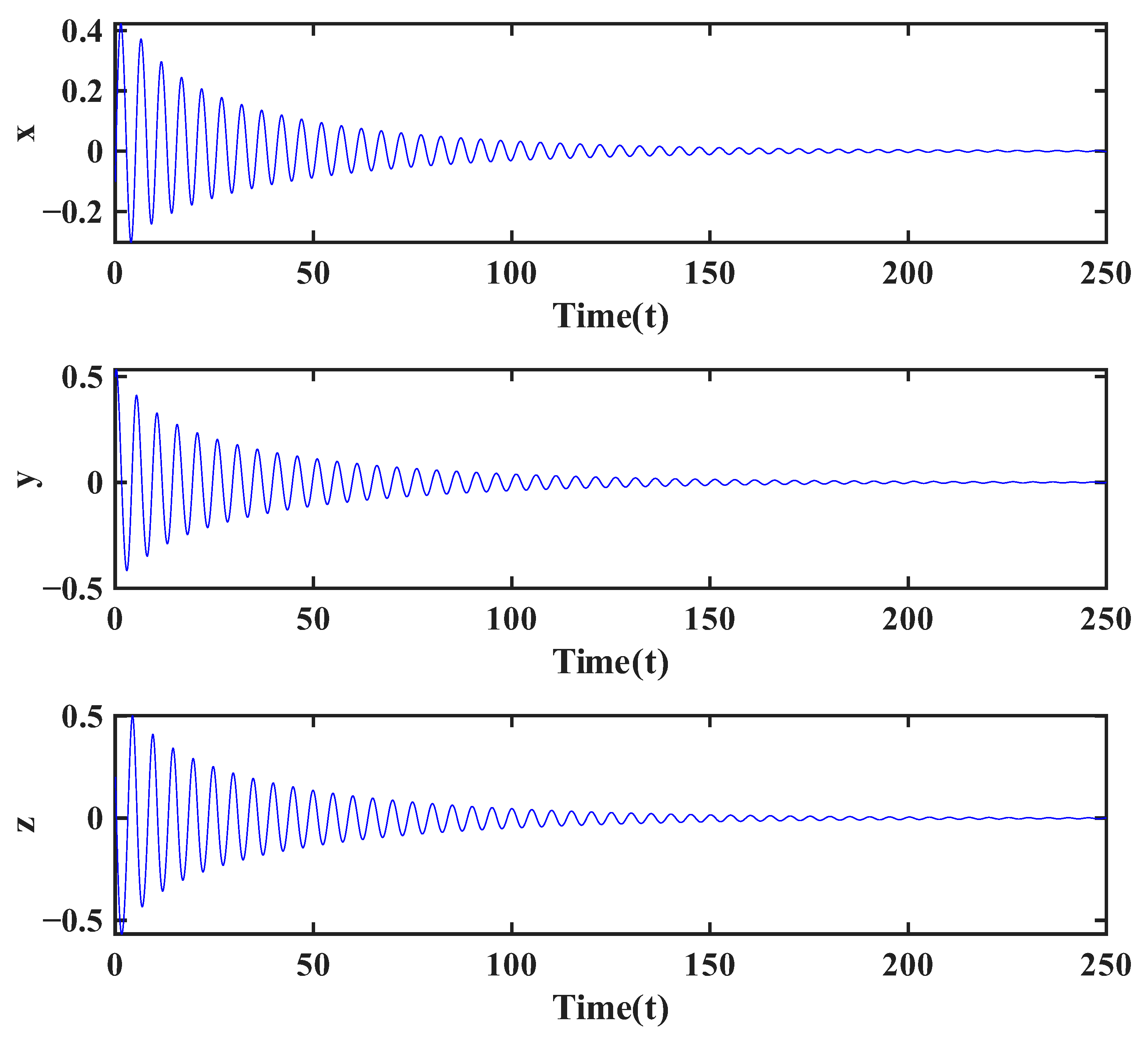

Numerical simulations in

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 present a compelling comparison of the system dynamics for constant and time-varying fractional orders

; one can see that the same pattern in all three cases is that the introduction of time-varying component

drastically changes the behavior of the system by inducing more complicated dynamics. Thus, in Case 1 (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), a system that exhibits stable periodic behavior for constant

is driven into a fully chaotic regime by time-varying

. In a similar way, Case 3 (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) demonstrates the transformation of the simple periodic limit cycle at

to the complex chaotic attractor under the action of

. Finally, in Case 2 (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), it can be seen that the time-varying order may

destabilize an asymptotically stable equilibrium point. The system, which demonstrates damped oscillations converging to zero for constant

, is instead forced into a chaotic motion by

. All of these findings collectively point to the variability in the fractional order as a strong factor that induces and sustains chaos in systems that would otherwise be stable or periodic.

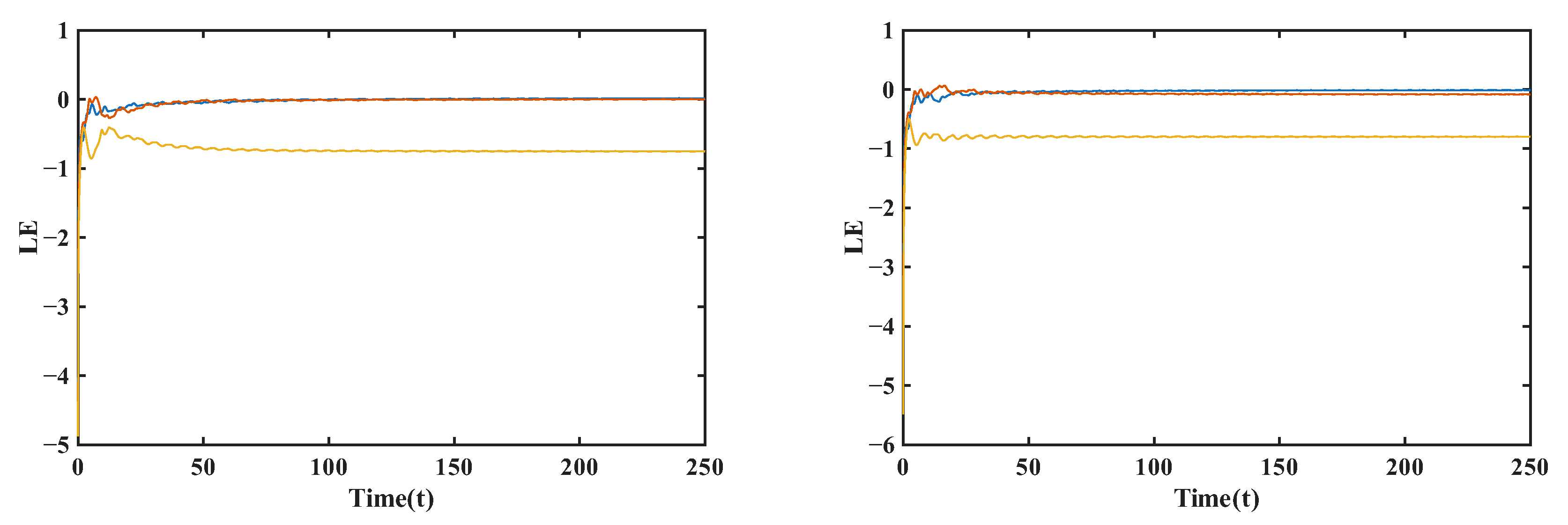

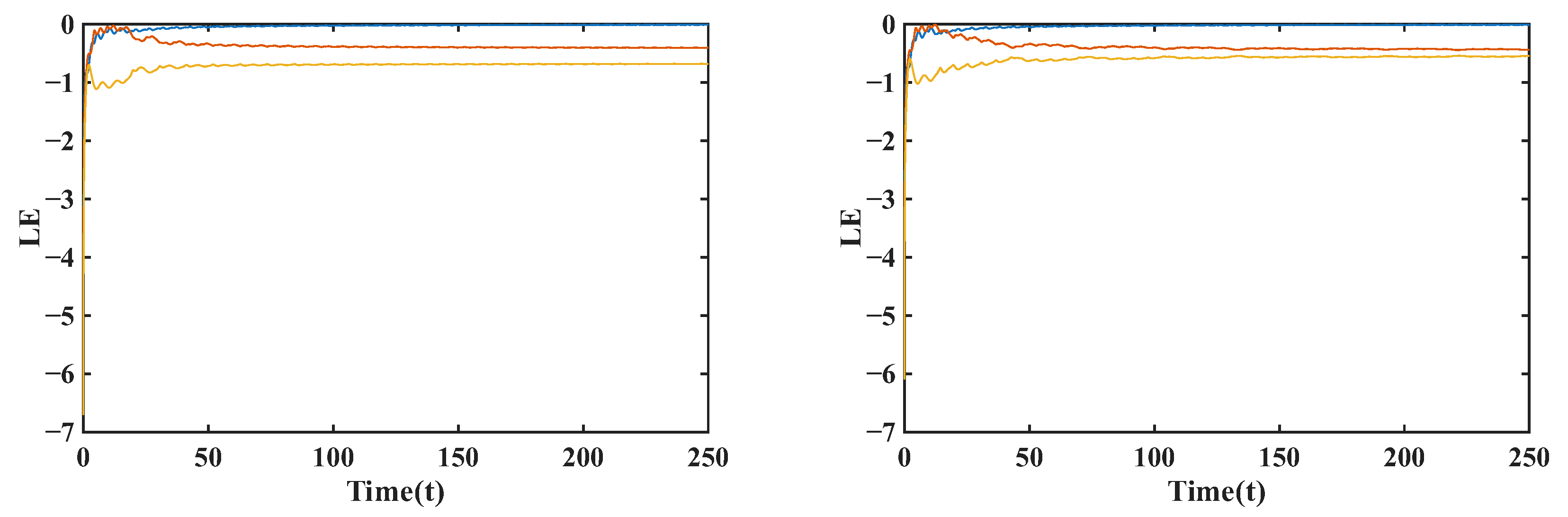

4.2. Lyapunov Exponent

In

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19, Lyapunov exponent (LE) time series are used to evaluate the effect of time-varying versus constant fractional orders on the stability of the system. For all the cases studied—namely

with constant

,

with constant

, and

with constant

—the largest Lyapunov exponent converges to a strictly negative value after an initial transient, confirming that the system remains nonchaotic and asymptotically stable. The presence of a slowly time-varying fractional order impacts only the transient behavior of LEs by introducing mild oscillations or longer settling times, while the long-term values are practically identical to those obtained with constant-order simulations. This evidences that the qualitative stability of the system is robust against small enough, smooth variations in

, and that such variations mainly impact short-term memory effects without causing bifurcations or chaotic transitions.

Empirical evidence from the time-varying variable-order (VO) fractional system, as can be seen in

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, demonstrates an important and new aspect of this complex dynamic: the

form of the time-dependent variable-order function directly dictates the morphology and dynamical laws of the resulting chaotic attractor. This goes beyond the general observation that VO is able to induce chaos. More precisely, it can be observed that the smooth boundary-approaching transition, defined by

, generates a unique chaotic structure which is quasi-periodic,

Figure 16, unlike the classical two-scroll attractors emerging from periodic modulations. Thus, this shows that novel chaotic mechanisms are inherently generated by nonlinear order variations, giving a deeper insight into how the time-evolution of fractional memory shapes the system dynamics, confirming the inherent dynamical richness of VO systems.

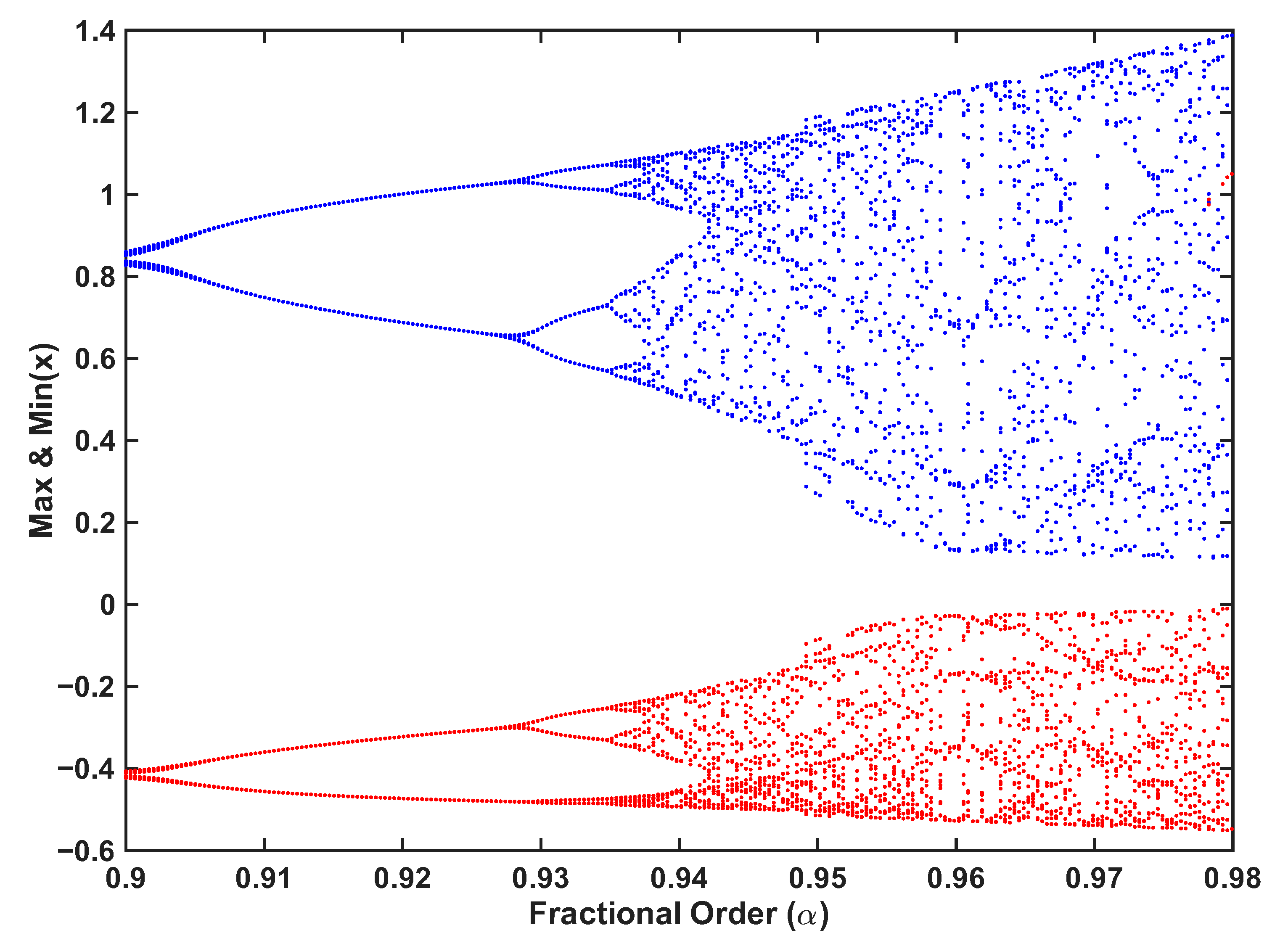

4.3. Bifurcation Anlysis

Figure 20 shows the bifurcation behavior of the considered fractional-order system for the fractional order

. The diagram depicts the long-term maximum (blue) and minimum (red) values of the state variable

x extracted after transient dynamics have been discarded. Clearly, fractional differentiation order directly influences the qualitative behavior of the system, especially the transition between regular and chaotic regimes.

For values of close to , the system has a stable periodic orbit where maxima and minima collapse into single branches, indicating low sensitivity to initial conditions and dominance of stable limit-cycle behavior. Increasing toward approximately , the branches start to split. This splitting of branches signals the onset of a period-doubling cascade. Successive doublings are a classical route to chaos and reflect the gradual loss of stability as the memory effect—controlled by the fractional order—becomes weaker.

For values of beyond approximately , the diagram fills up rapidly, and points along both the blue and red branches become very scattered. Such a structure is typical for chaotic attractors and thus verifies that the system becomes fully chaotic. Convergence to periodic cycles does not occur in this range, but trajectories exhibit a strong sensitivity with respect to variations in the parameter and initial conditions. Overlapping clusters bear evidence for various coexisting oscillatory modes, as usually happens in fractional-order nonlinear systems.

While increases towards , the chaotic band expands further vertically, with both the maxima and the minima having taken on larger values within a wider range. Stretching of the chaotic band further means an amplification of the amplitudes of oscillations, and hence the enhancement of chaotic intensity. Asymmetry in the system dynamics reflects the fact that nonlinear feedback terms act differently upon positive and negative excursions of the state variable.

5. Numerical Solutions

The numerical comparisons in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 illustrate the impact of variable-order fractional dynamics on the system response compared with the respective constant-order counterparts. In the first case, with the order oscillating as

, the differences between the solution at constant order

and the one at variable order

are small but visible, especially for larger

t. This situation is consonant with the modest periodic variation in

, causing minor adjustments of the trajectory without changing the overall pattern of the system. In the second case, given by

, the fluctuation in fractional order is smoother and of smaller amplitude. This results in a closer match between the constant and variable-order outputs, particularly in the initial time period. As

t increases, the differences become more noticeable, but they are still limited because of the smooth sinusoidal change in

. The largest difference is seen in the third case, where the order increases according to the nonlinear function

. This function quickly drives the system towards a higher effective memory as

t increases. Consequently, a substantial disparity emerges between the constant and variable-order solutions, especially for

, where the variable-order model’s corresponding values of the states are visibly amplified or attenuated. Overall, the three scenarios unequivocally illustrate that the magnitude and nature of the divergence between constant and variable-order dynamics are directly contingent upon the specific form of

: smooth, low-amplitude fluctuations lead to minor deviations, periodic variations induce a moderate oscillatory effect, and monotonic nonlinear growth engenders substantial alterations in the system’s behavior, thereby highlighting the enhanced sensitivity of fractional systems to time-varying memory effects.

6. Discussion

This comparative study between the constant-order and variable-order formulations of the fractional Genesio-Tesi system offers substantial information about how fractional operators can influence nonlinear chaotic dynamics. The numerical results clearly show that the location of stability boundaries, transient responses, and long-term behavior depend strongly on whether the fractional order is fixed or allowed to vary with time.

Thus, in the constant-order model, the use of Matignon’s stability criterion provides a clear, analytical threshold for the onset of instability. For constant fractional order, necessary and sufficient conditions for local asymptotic stability are provided by the spectrum of eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix. As a matter of fact, for either decreasing fractional order or system parameters out of the stability domain, the theoretical prediction agrees well with numerical simulations, supported by all the phase portraits and the sign of the largest Lyapunov exponent, confirming the transition toward oscillatory or chaotic behavior. Therefore, for the constant-order formulation, stability regions can be identified both analytically and numerically.

While the variable-order formulation introduces one more level of dynamical richness, since Matignon’s criterion cannot be applied directly in cases where the differentiation order changes with time, the stability analysis must rely entirely on numerical indicators. Time-series analysis, Lyapunov exponents, and phase-space trajectories demonstrate that orders changing in time intensify the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions and amplify irregular oscillations: transient chaos is stronger, divergence intervals are longer, and the structure of attractors is more complex. Such behavior underlines that memory effects in systems of variable order are not stationary but evolve with time, which influences the rate at which information about the past affects the current state. This kind of dynamic modulation of memory creates a more complex route to chaos than the constant-order case.

Another important finding is that the variable-order system displays wider regions of chaotic motion across the parameter space. Bifurcation diagrams suggest that parameter intervals that remain stable under constant-order dynamics become chaotic once the order starts to vary. This suggests that variable-order derivatives serve as an intrinsic source of dynamical excitation, effectively enriching the nonlinear response of the system. Such behavior is of particular relevance for understanding real processes where the memory strength of the system is inherently non-uniform, including biological systems, viscoelastic materials, and adaptive control mechanisms.

The study is oriented toward theoretical and numerical analyses; the results provide good ground for further explorations of possible applications that might arise in the future. For example, the increased chaoticity of the variable-order model might be useful in the construction of high-entropy signal generators, synchronization schemes, or robust encryption algorithms. Given that such applications are beyond the scope of this paper, the dynamical properties presented here suggest that fractional-order and variable-order formulations might enable further research into secure communication or nonlinear control strategies. These options will be left for future studies, as the work at hand is confined to the mathematical characterization and numerical exploration of the dynamics of the system. The comparison shows, in general, that constant-order fractional systems are still well-described using classical stability tools, but for variable-order systems, a completely numerical approach has to be taken because direct analytical conditions of stability are lacking. Inclusion of time-varying fractional orders significantly enhances dynamical complexity, changes the stability landscape, and enriches chaotic behavior. These conclusions make for a more profound understanding of fractional nonlinear systems and strengthen the role of variable-order FC for the purpose of modeling real dynamical processes.