Abstract

Obtaining accurate estimates of the true probabilities of sporting events remains a long-standing problem in sports analytics. In this paper we propose a new domain-driven approach that infers true probabilities from betting odds. This task is not trivial, as betting odds are noisy because of bookmaker margins (vig), insider bets, and model imperfections. In this study, we present a novel approach that integrates estimates across multiple groups of betting markets to obtain more robust estimates of true probability. Our method takes market structure into account and constructs a constrained optimisation problem that is solved using the Dixon–Coles model of a football match. We compare our approach with a wide range of existing methods, using a large dataset of 359035 matches from more than 6000 leagues. The proposed method achieves the lowest log-loss and the best probability calibration among all tested approaches. It also performs the best in terms of expected profit convergence in Monte Carlo simulations, outperforming its competitors in terms of MSE and bias. This study contributes both to a new margin-removal (devig) method and provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of other known methods. Beyond football, this approach has potential applications in other sports with discrete scoring systems and potentially in other areas involving stochastic processes and market inference, such as prediction markets, finance, reliability engineering, and social prediction systems.

Keywords:

system identification; sports modelling; probability estimation; bookmaker odds; devigging methods; Dixon–Coles model; betting markets; predictive modelling MSC:

62P99

1. Introduction

Modern science and engineering relies heavily on mathematical modelling, allowing researchers to simulate processes and predict future outcomes. Sports modelling is no exception to this trend, due to its popularity and unpredictable nature. In recent decades, the problem of estimating true probabilities of match outcomes has attracted growing interest from scientists, quantitative analysts, and bookmakers. Moreover, for bookmakers, this is not just a theoretical task, it directly affects their profitability.

Bookmakers publish odds based on their views on fair probabilities, adjusted for profit margins and risk policies. Over time, with more new information and placed bets, these odds re-adjustments lead to more aggregated liquidity and more efficient markets. This process is sometimes also referred as “wisdom of the crowd” and fair price discovery. However, this process still requires some baseline estimate from a bookmaker. If a bookmaker undervalues the odds (i.e., overvalues implied probabilities too much), bettors will stop betting at that exact bookmaker and go looking for better odds from competitors. On the other hand, if a bookmaker offers overvalued odds that are too high relative to the true probabilities, skilled bettors will exploit such odds, resulting in possible losses for the bookmaker. Accurate probability estimations, therefore, are essential for setting competitive and profitable odds [1].

This dual pressure on bookmakers means that they must be accurate in their probability estimates used to create betting odds, which leads to an interesting inverse problem: can true probability estimates be inferred from betting odds? This problem is non-trivial due to the existence of bookmakers’ commissions (also known as overrounds, vig, and margins), different risk policies, existence of market insiders, and odds biases such as the favourite–longshot bias [2].

Over time, many methods have been proposed to obtain estimates of true probabilities from betting odds. These methods can be called “devig methods”, as they are trying to remove bookmakers’ margins to obtain estimates of true odds.

Early naive methods have been around since the earliest bookmakers appeared, but to achieve better results, more sophisticated models were created. These advanced methods include simple probabilistic normalisation [3], the Knowles–Woodland method [4], and the Shin method [5], which offer better ways to account for overrounds, presence of informed players, and risk-aversion policies of bookmakers.

Later developments include Rascher’s method [6], who developed closed-form solutions for two-outcome markets, and the method by Gandar et al. [7], who extended earlier normalisation methods. Some methods, such as the “odds ratio” approach [8], attempt to distribute bookmakers’ margins in a way that better captures biases in betting odds. There are also methods that are little known in the academic world, since these methods have not been published in peer-reviewed journals, such as the Jensen–Shannon divergence (JSD) method [9], developed by Christopher D. Long, which introduced the perspective of statistical noise reduction. Another method that has not been scientifically published is the Goto conversion, recently proposed by Kaito Goto [10], which uses empirical standard errors to correct for skewed odds and has resulted in over 10 gold-medal-winning solutions and 100 medal-winning solutions on Kaggle.

While a number of methods have been proposed, some issues in deriving estimates of true probabilities from betting odds still persist. For example, some methods can produce inconsistent probability spaces across different bet groups (i.e., probabilities that do not sum to one). In addition, all methods described above use odds from a mutually exclusive group of outcomes, without using the broader context of other available outcomes and their odds. While it might be useful in some cases of limited information, usually we are able to obtain betting odds from multiple groups at once.

In this paper, we propose a new domain-based approach that uses information from multiple outcome groups to obtain well-calibrated estimates of true probabilities of football match outcomes. This approach uses almost all available odds except exotic ones, not just a single group of mutually exclusive outcomes. By using more market groups, the proposed approach combines more underlying information with the corresponding smart-liquidity from different odds, resulting in more accurate probability estimates [11].

Moreover, usage of the domain model makes obtained probabilities consistent across different outcome groups, so that they do not contradict each other. To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe and apply such a domain-based identification approach to recover estimates of the true probability of football outcomes from betting odds.

We compared the performance of our method with a set of known methods on a large, purposely built dataset. Our results showed that even seemingly small differences in probability estimates can have significant long-term impact on the calibration of the method and the expected cumulative profit. This study contributes a new modelling method and a comparison of existing approaches in the context of a relatively big dataset with real betting data.

The main findings of this article include the following:

- 1.

- Description of a new devig method for estimating true probabilities of football match outcomes;

- 2.

- A comparative analysis of the known devig methods and the proposed method, showing that the latter method gives the best results in most experiments;

- 3.

- An example of the successful application of a domain model for the efficient regularisation and solution of an underdetermined system of equations.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 outlines materials and methods, including dataset, existing devig methods, and the proposed method with implementation details. Section 3 presents a comparison of all methods using different approaches and metrics, such as expected calibration error (ECE), log-loss, Brier score, and others. Section 4 gives a results discussion, mentioning known limitations and further plans. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper, summarising main findings and results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

This study uses a purposely built dataset that contains information about decimal pre-match odds for football matches observed at one of the largest European bookmakers. The dataset includes the following fields: match date, league name, team names, final score, and betting odds. A distinctive feature of this dataset is its scale: it covers over 359,035 matches and contains odds for over 3,182,000 outcomes, spanning the period from 1 January 2022 to 12 May 2025. This is significantly larger than most of the datasets used in previous studies related to sports modelling, and includes matches from both top and lower divisions, such as junior and semi-professional competitions. The raw dataset was saved as a collection of JSON files, using about 1.5 GB of disc space; later, it was converted into parquet file, containing only the post-processed fields described above, resulting in disc usage of 88 MB. Information about dataset availability can be found under related Data Availability Statement.

While most columns of the dataset are self-explanatory, the betting odds deserve special attention. They are represented as tuples, containing an internal outcome label (e.g., WIN__P1 for outcome “Home team will win”) and the corresponding decimal odds from the bookmaker website. Other formats such as American or fractional odds also exist, but they convey the same information [12]. In this study, we used decimal odds for simplicity.

Proper understanding of odds also requires knowing how potential winnings are calculated. In the event that the outcome condition comes true, the bookmaker pays the player an amount equal to his stake, multiplied by the odds related to that outcome. If the outcome condition does not come true, then the player’s bet loses and the bookmaker keeps the player’s original stake. For example, consider a bet on outcome “Over 2.5 goals” with decimal odds of 3.3 and stake of $5, then a final score of “3:1” yields a total payout of $16.5 ($5 × 3.3), while a score of “2:0” results in no return and a loss of the initial $5 stake. A formal description of all used betting types will be given in the next subsection.

While collecting this dataset, we tried to collect odds that were as close to the match start time as possible. This is based on empirical evidence (e.g., [13]) suggesting that the amount of information embedded in the odds increases as the start of a match approaches, due to higher liquidity and market activity.

Table 1 compares datasets used in this study with datasets from popular football modelling papers. In cases where exact match counts were not provided by authors, we estimated dataset size based on the mentioned number of seasons and leagues (such cases are marked with asterisks). While there may be minor imprecisions in such estimates, they do not affect the broader comparative context of the dataset sizes commonly used in the football modelling literature.

Table 1.

Comparison of datasets in previous studies.

2.2. Bet Types

In this section, the types of bets used in the study are formalised using set theory and indicator functions, as this is necessary for further modelling and proper understanding of the subject area.

Let us define the maximum possible number of goals scored by a single team in a match as , in order to work with finite instead of infinite sets. In theory, each team can score an infinite number of goals, but in practice, this is impossible due to physical limitations such as the fixed duration of a football match or the maximum running speed of a human. Furthermore, handling infinite sets is impractical from a computational standpoint. Taking this into account, we decided to artificially limit the maximum number of goals.

It is important to note that proper limitation of max team score results in virtually no loss of calculation accuracy, as a large number of goals is a very unlikely event, and the corresponding tail probabilities can be neglected, as they are close to zero. In our dataset, the maximum number of goals scored by one team was approximately 30, so we decided to choose as a safe enough margin to maintain accuracy.

Given above information, the set of possible values of the number of goals for a single team is defined as follows:

and the sample space of all possible final scores of the match is a Cartesian product:

where x and y denote the scored goals for the home and away teams, respectively.

The payout mechanism was described earlier: it depends on the bet amount, the odds themselves, and whether the associated outcome condition is satisfied. In the rest of the article, the bet size is treated as one abstract unit unless explicitly stated otherwise.

To simplify the following equations, let us define a subset of match outcomes that will result in a winning bet via an indicator function that returns 1 if the bet wins and 0 otherwise. This set of winning final scores is defined as follows:

For a better understanding, let us look at an example of such a set of winning final scores for the bet “Match will end in a draw”:

As can be seen, we are using indicator function to define . For all bet types used in this study, the conditions associated with their indicator functions are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bet types and their corresponding indicator function conditions (where x and y denote the scored goals for the home and away teams, respectively).

Other bet types exist, but we decided to exclude them as they are not so popular and harder to model. One example of such bets is so-called “push” or “void” totals and handicaps, another example is “Asian” totals and handicaps. To avoid these bets, the parameter P in all above bets must have the form of , where . Also, for totals and individual team totals, we additionally require , since the number of goals cannot be negative (while the handicap can be negative).

2.3. Established Methods for Calculating Implied Probabilities

This section reviews several methods for calculating estimates of true probabilities based on bookmakers’ betting odds. It is important to note that most of the methods described below are non-trivial. Many of them are formally presented in separate scientific articles, complete with motivation, derivation details, and proofs. A full analysis of each method is beyond the scope of this paper. We provide a concise overview of the core ideas and formulas used in the experiments. References are given when available; for unattributed heuristics, the reader should treat them as empirical or ad hoc methods rather than fully validated models.

All described methods assume a single group of mutually exclusive outcomes as input. Although most methods generalize to groups with multiple outcomes, in this study we worked only with groups containing two opposite outcomes. For clarity and convenience, for some methods, we presented only formulas describing groups with two outcomes, without generalising to multiple outcomes.

It is also possible that specific proprietary or less common heuristics have been omitted from the below list of methods. However, because all such methods share the objective of removing margins from a fixed set of mutually exclusive outcomes, they generally exhibit high correlation with the methods presented here. Consequently, we believe that inclusion of additional methods would not significantly alter the conclusions drawn in this study.

To help with intuition, here are some examples of groups with two mutually exclusive outcomes that are common in football betting:

- “Home team win” and “Draw or Away team win” (double chance);

- “Total goals under 2.5” and “Total goals over 2.5”;

- “Both teams to score—Yes” and “Both teams to score—No”;

- “Home team to win with handicap +1.5” and “Away team to win with handicap −1.5”;

- etc.

In all the methods described below, are the bookmaker’s decimal odds for outcome i. For groups with two outcomes, and are the decimal odds for the first and second outcomes in the same group.

2.3.1. Naive Inversion

The simplest method is based directly on the definition of decimal odds as the inverse of the probabilities. Assuming no bookmaker’s margin, we can calculate the probability estimate as follows:

This naive approach yields probabilities that sum to more than 100 %, indicating the presence of a bookmaker’s fee. In later results this method is denoted by naive.

2.3.2. Simple Normalisation

A common way to improve the naive approach is to normalise inverted odds, so that the obtained probabilities sum up exactly to 100 %, as required by the properties of mutually exclusive probabilities. For a group with two outcomes, adjusted probabilities are calculated as follows:

In later results this method is denoted as norm.

2.3.3. Knowles–Woodland Method

The Knowles–Woodland method [4] is one of the earliest formal models in economics of betting odds; it derives fair probabilities assuming zero expected bookmaker profit on symmetric bets:

In later results this method is denoted by knowles.

2.3.4. Gandar Modification

Gandar et al. [7] improved on the Knowles–Woodland approach by replacing the arithmetic averaging of and with a multiplicative term , which more accurately reflects fair probabilities in highly asymmetric markets. The resulting equations are as follows:

This method is denoted by Gandar.

2.3.5. Shin’s Insider Model and Rasher’s Closed-Form Solution

Another approach to bookmaker odds was proposed by Shin [5]. His model assumes the presence of informed bettors (insiders) who know the actual outcome of a match and place bets accordingly. A bookmaker, aware of the potential existence of such insiders, sets odds to maximise expected profit, taking into account the ratio of informed to uninformed participants.

Shin introduces a parameter , which represents the share of insider money in the market. For a market with two possible outcomes, the equilibrium probabilities are derived using the following equations:

In general, for markets with more than two outcomes, z must be estimated numerically, since the Shin model does not provide a simple explicit expression. However, Rascher [6] derived a closed-loop approximation of the Shin equilibrium, simplifying the calculations without need for iterative solution. His formula for a group with two outcomes can be represented as follows:

It has also been shown that for two-outcome markets, Rascher’s solution yields results equivalent to Shin’s original model, while being more computationally efficient and easier to implement [25].

In our paper, we use this simplified form and refer to it as Rascher.

2.3.6. Odds Ratio Method

As an alternative approach, Cheung [8] assumed that the odds ratio between the true and implied probabilities remains constant:

So that for a group with two outcomes:

We call this method ratio.

2.3.7. Proportional Margin Method

Bukhdahl [26] introduced the margin distribution heuristic, where he assumes that the margin applied by the bookmaker for each of the outcomes is proportional to the probability of the outcome. In other words, he tried to capture the favourite–longshot bias by removing unevenly applied bookmaker fees.

For n outcomes with a total overround , the true odds are as follows:

This method is denoted by prop.

2.3.8. Heuristic Balance Adjustment

A heuristic adjustment without proper attribution was also discovered in some legacy production code. The method appears to remove the entire bookmaker margin M from the raw implied probabilities and then re-normalise the odds so that they sum to 1. The probability formula is as follows:

where .

Conceptually, this adjustment can be interpreted as an attempt to eliminate linear bias in bookmakers’ beliefs. It assumes an unrealistic linear margin model and can lead to strange behaviour for extreme odds. Despite these theoretical shortcomings, the method has been found in real production code and appears to have been proven to be effective in practice.

For these reasons, we include it in our empirical comparisons for completeness, while noting that from a theoretical perspective, this method is inherently weak. We denote this method by balance.

2.3.9. Jensen–Shannon Distance (JSD)

Another approach was developed by Christopher D. Long [9] and is based on Jensen–Shannon Distance. The goal of this method is to balance the logarithmic discrepancy between the true and predicted probabilities. The method implies that devig correction preserves a symmetry in log-odds (logit) space, which is much closer to linear than probability space and better reflects how bookmaker margins are applied:

Then solve for and

This method is denoted as jsd.

2.3.10. Expected Information Gain (EIG) Heuristic

Another unattributed approach is based on Expected Information Gain and attempts to equalise the likelihood-based information content of the two outcomes. It is conceptually similar to the JSD method, but uses a simpler entropy-like likelihood score rather than full JSD. The idea is to adjust the odds so that the two outcomes have equal self-information under the devigged probabilities:

The result is denoted as eig.

2.3.11. Goto Conversion Method

The last method was described by Kaito Goto and it is called “Goto Conversion” [10]; this method adjusts each naive implied probability by a multiple of its standard error. This approach aims to account for the favourite–longshot bias by exploiting the proportionally wider standard errors implied for inverses of longshot odds and narrower ones for favourites.

Given a vector of odds , the corresponding naive implied probabilities and their standard errors are calculates as follows:

Finally, adjusted probabilities are obtained by shifting all proportionally to their standard errors:

This heuristic is denoted by goto.

2.4. A New Approach to Recovering True Probabilities

Despite using different ideas, all of the above methods rely on a single group of mutually exclusive outcomes to estimate true probabilities. They do so to evaluate the group’s probability overround and account for it.

In practice, however, we are usually able to observe multiple groups of mutually exclusive outcomes for any given event, rather than just one such group. So, usage of only one group leaves much of the available information untouched. This can lead to inaccurate or inconsistent probability estimates across different groups of outcomes.

To overcome this limitation, we propose a method for recovering estimates of true probabilities that simultaneously uses multiple groups of mutually exclusive outcomes. This approach aims to incorporate most of the available information, and it ensures consistency of estimates by using the domain model of a football match. The following sections describe motivations and methodology behind the proposed method.

2.4.1. Constructing a System of Equations

The first step in reconstructing estimates of true probabilities is to formulate a system of equations that captures as much relevant information as possible from the available betting odds.

We use the previously defined probability space of final scores: , where denotes the final score with x and y goals scored by the home and away teams, respectively. The value is chosen to constrain the score space and make it finite (e.g., , since observing more than 50 goals from one team is very unlikely in football, as was described earlier in Section 2.2).

Let:

- denote the set of all observed bets with known decimal odds corresponding to a single match;

- be an indicator function of bet , equal to 1 if outcome results in a win for a given bet, and 0 otherwise;

- , i.e., the set of outcomes for which the bet wins;

- be the unknown estimate of true probability for final score corresponding to a single match;

- be an estimate of the win probability for bet , obtained from the market odds of a mutually exclusive group of outcomes corresponding to a single match, using one of the methods described in the previous subsection.

Each bet imposes a linear constraint on the unknown goals distribution :

The complete system for a single match consists of these equations for each available bet:

where is the number of available bets of a single match.

Let denote the set of final scores, whose size is equal to the amount of unknown variables in the system:

In other words: If final score is known to be the winning condition of any bet used in the system of equations, then we have the related unknown variable .

However, as we use multiple groups of mutually exclusive outcomes, then each outcome is covered by at least one indicator function. Therefore, we have

and the number of unknowns in the system becomes

while the number of equations remains , and typically

It makes described system under-determined and requires additional assumptions to reconstruct the probability distribution. This is why we used domain knowledge to assume that the joint distribution of follows the Dixon and Coles model [21], which provides a parameterised approximation of football match results using correlation-corrected Poisson distribution. In the next section, we describe how this domain model can be used to solve the described system of equations.

2.4.2. Domain Model

The Dixon–Coles distribution [21] is defined by parameters vector and models the joint distribution of goals scored by two football teams as follows:

where the correction factor is evaluated as follows:

Here, and are the Poisson means for the average amount of goals scored by each team and is a dependency parameter that adjusts for the goals correlation of low-scoring pairs, such as , , , and .

Substituting this distribution into the previously described system of equations transforms it into a nonlinear system. However, this substitution also reduces the number of unknowns from large to just three, namely , and , so that the resulting system can potentially be solved.

This substitution imposes additional restrictions. The parameters and represent the expected number of goals scored by each team and therefore must be strictly positive, while must remain within the bounds that keep the all distribution probabilities between 0 % and 100 %.

Generally speaking, we do not necessarily need to use the Dixon–Coles model. Other domain models describing the distribution of football goals will work just as well. If other models are used, the entire logic described here will remain unchanged, and only the vector of parameters for the joint goal distribution will change. For the experiments in this article, we decided to focus on the most popular football model, the Dixon–Coles model, but the choice of the optimal domain model remains an open question and is beyond the scope of current research.

2.4.3. Solving the System of Equations

Given the nonlinear nature of the system, we applied a numerical optimisation method to find an approximate solution, minimising the sum of errors over all equations. To ensure the smoothness of the objective function, we minimised the sum of squared residuals. For constrained optimisation, we used the L-BFGS-B algorithm, which supports bound constraints on , and computes gradients using two-point finite differences.

The final objective function was defined as follows:

where , is the weight of each bet, and is the total weight.

Since the parameter space for is compact (closed and bounded) and the loss function is continuous, the existence of a minimiser follows from the Extreme Value Theorem [27]. The uniqueness of a minimiser, however, cannot be guaranteed: the solution depends entirely on probabilities derived from external bookmaker odds, for which we make no assumptions, so in inconsistent or degenerate cases, multiple minimisers or flat loss regions may occur.

In our experiments, we optimised the parameters for each match using the available bookmaker data, and removed a small fraction (less than 1%) of matches with particularly large fit errors, which were probably caused by rare errors on the side of betting data providers. Remaining data produced accurate probability estimates for tested bets (see Section 3). For practical deployment, users may consider running the optimisation from multiple initial points to assess solution stability. It may help to detect rare cases of convergence to local minima or poorly conditioned solutions.

Although uniqueness cannot be formally proven, we provide practical recommendations to increase robustness: while constructing a system, use a diverse set of bets that constrain both relative team strengths and total expected goals. For example, using only parameter-free bets for two equally strong teams leaves the system under-determined: any pair with similar values satisfies the constraints of equal strength, but yields unrealistic predictions for parameterised markets such as totals, team totals, or handicaps. The inclusion of additional markets with parameters such as “Total goals over/under 2.5” removes this ambiguity. These markets impose direct constraints on the sum of expected goals through the corresponding decimal odds, which, in combination with the condition of relative team strength, significantly narrows the admissible range of parameter values and makes it possible to obtain meaningful and accurate results from solving the system.

However, this example is not sufficient to guarantee global uniqueness for all possible cases: other forms of degeneracy may still occur, since bookmaker probabilities are external inputs, over which we have no control and make no assumptions. Thus, bet diversity mitigates one common source of non-uniqueness, but does not guarantee the mathematically strict uniqueness of solutions in general.

2.4.4. Choice of Method Components

At this point, it should be clear that we are not proposing a single method for removing bookmaker margins, but an entire family of methods. A specific method within this family is determined by the choice of the following components: the domain model of a football match used to obtain , the probability-estimation method used to obtain , the weighting function , and the loss function used to measure the discrepancies between and .

Numerous models of football matches exist, some of which are discussed in the papers listed in Table 1. Conservatively, about ten popular models could be used instead of . As for the method for estimating the underlying probability , we can choose from at least eleven different methods described earlier in Section 2.3. Weight and loss functions can take various forms, but for simplicity, we limit ourself to three types of weighting functions (constant, proportional to , proportional to ) and three loss functions (MSE, MAE, RMSE).

Even with these artificial limits, the resulting family contains roughly 1000 possible methods for removing bookmaker margins. Evaluating the properties of each method would require substantial computational resources, particularly with large datasets such as ours. Finding the optimal method therefore lies beyond the scope of this article, where we focus on describing the concept of this family of devig methods.

Nevertheless, a specific method must be selected for experimental verification. Our choice is guided by intuition and practical considerations rather than by formal mathematical criteria. Nevertheless, as the Section 3 shows, even this intuitively chosen method significantly outperforms existing devig approaches, highlighting the advantage of the proposed approach.

In all reported experiments we use the Dixon–Coles domain model to evaluate , the Knowles–Woodland method to estimate , constant bet weights, and MSE as the loss function.

More sophisticated alternatives could improve results of the model. For example, weighting bets proportional to may help to reduce the favourite–longshot bias, a well-known phenomenon in the betting market, where bookmakers tend to apply higher overrounds on unpopular “longshot” outcomes [2], but as noted earlier, exploring such extensions lies outside of the scope of the current research and could be addressed in future work.

2.4.5. Recovering the Probability

Once the parameters of the Dixon–Coles model are found, they can be used to calculate estimates of the true probability for any given bet, even for those bets that were not originally used in constructing the system of equations. This is achieved by using the same formulation that was used in constructing the system of equations:

Here, represents the probability of the match ending with a score of based on the Dixon–Coles model with parameters , , and , and is an indicator function to obtain winning outcomes associated with the bet, with denoting the set of these outcomes.

3. Results

Having developed a new approach of estimating true probabilities, we needed to evaluate its quality in comparison with existing methods. Since each match has already ended, we know their final scores. Using the final score and indicator functions described in Table 2, we can determine whether each of the 3,182,000 bets was a win or not. This information will help us determine the goodness of the probability estimates of each method, by comparing their behaviour across the entire dataset.

3.1. Calibration and Scoring Metrics

As discussed in [28], calibration is a critical property of probabilistic forecasts in betting applications. We evaluate calibration using the Expected Calibration Error (ECE), defined over M quantile-based bins constructed from predicted probabilities of each method. Let be the set of indices whose predictions fall into the m-th bin. The empirical accuracy and the mean predicted probability in each bin are as follows:

where is a binary value determining if the bet resulted in a win, and is a bet win probability obtained with the method for which we are evaluating the ECE.

The Expected Calibration Error for bins and samples is then computed as follows:

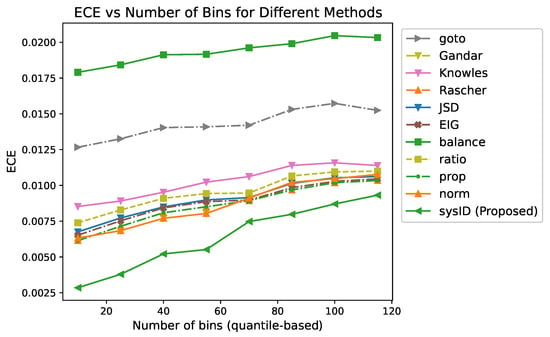

However, we found that the ECE estimates are unstable and highly sensitive to the number of bins used to partition the probability space. An example of this ECE instability is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of ECE instability with different numbers of bins for several methods, including the proposed method.

The proposed approach remained the most calibrated across all binnings, whereas several other methods exhibited overlapping ECE values and ranking instability depending on the number of bins. To address this issue, ECE was replaced with strictly correct scoring rules that provided unambiguous estimates without binning-related issues.

In particular, we employed two widely used metrics: Brier score (BS) and log-loss (LL). For a set of probability predictions and binary outcomes of related bets , these metrics are defined as

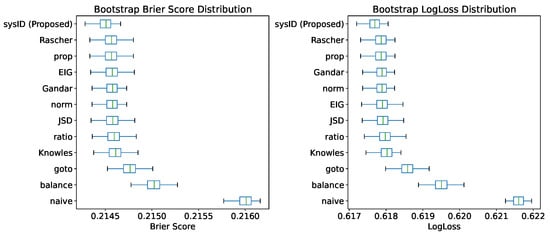

To obtain more robust estimates of methods performance, the bootstrap method was applied. For each method, we generated 100 bootstrap samples by drawing observations with replacement from the original dataset (with all bets from all matches) and computed both BS and LL on each resampled dataset. This procedure yielded empirical distributions of the scoring rules for every method, enabling a statistically sound comparison. The results are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of methods using the Brier score and log-loss for 100 bootstrap random samples with replacement with the size of the entire dataset. Lower values indicate better results.

Calibration curves are also often used to compare probabilistic classifiers (e.g., [29]), but suffer from the same binning sensitivity as ECE. Moreover, predicted probabilities produced by the examined methods were highly correlated (over 99%), resulting in nearly overlapping calibration curves that provided little visual insight.

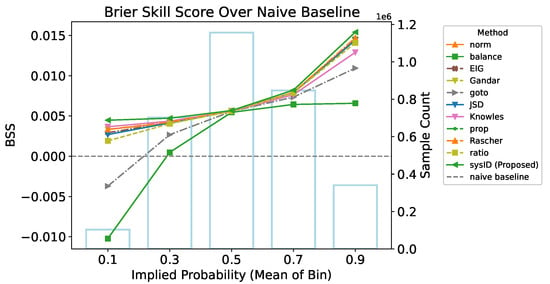

To address this issue, we evaluated performance using the Brier Skill Score (BSS) computed across probability bins, using the naive devig method as a reference baseline. For a given bin, let denote the Brier score of the evaluated method and the Brier score of the baseline. The Brier Skill Score is defined as follows:

A positive BSS indicates improvement over the baseline, whereas a negative value suggests inferior performance. The results from Figure 3 indicate that the proposed method consistently outperformed other methods in most or all bins, depending on the binning scheme. The most significant improvement can be observed at extreme probabilities, closer to 0 % and 100 %.

Figure 3.

Relative improvement in Brier score over the naive baseline method for different probability bins. The proposed method outperforms the others across all bins in the given binning (higher BSS is better).

3.2. Assessing Similarity of Methods Using MDS Projection

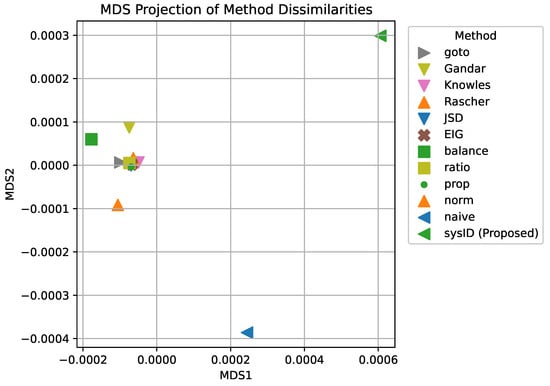

As noted earlier, the predicted probabilities between models exhibited statistically significant linear correlations exceeding 99 %, making it difficult to distinguish between models using traditional visual tools such as calibration curves. To better understand and visualise the subtle but important differences between methods, we employed a geometric approach based on pairwise dissimilarities.

Specifically, we computed a dissimilarity matrix using the correlation distance between the probability vectors of methods i and j. We then applied metric multidimensional scaling (Metric MDS) to embed this dissimilarity matrix into a two-dimensional space using the implementation provided in scikit-learn [30]. Metric MDS seeks a low-dimensional configuration of points whose pairwise Euclidean distances approximate the input dissimilarities by minimising a standard “stress” objective [31].

MDS preserves the structure of the dissimilarity matrix as accurately as possible, making it suitable for identifying global relationships between methods, in contrast to nonlinear methods such as t-SNE [32] or UMAP [33], which prioritise preserving local neighbourhoods. The resulting MDS projection (see Figure 4) provided an interpretable structure: devig methods located close to each other produce similar probability estimates, while those positioned further apart behave more differently.

Figure 4.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) projection of correlation distance-based forecasting methods.

As was shown in the MDS plot, the proposed method was clearly distinct from the group of most existing non-naive devig methods. This distinction confirms that the proposed method is not just a small improvement, but a qualitatively different approach to the reconstruction of true probabilities.

3.3. Monte Carlo Profit Simulation

While the previous experiments demonstrate clear improvements in calibration, the fundamental premise of this research is to recover the bookmaker’s implied true probabilities, because bookmakers are generally considered accurate estimators of true probabilities, so an important question remains: how closely do our proposed probabilities approximate the bookmaker’s internal estimates of true probabilities? To validate the closeness of our approximation, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the convergence of observed historical cumulative profit with the expected cumulative profit derived from each devig method.

Consider a hypothetical player with a fixed but unknown risk tolerance. For nearly certain bets with an implied probability of winning close to 100 %, the player bets one abstract unit, and for less probable outcomes, the bet size decreases proportionally to the risk level. Assuming the player uses a naive devig approach to risk assessment, the bet size with decimal odds will be set to abstract units, implying that high-risk bets receive smaller bet sizes.

We first evaluate the observed profit based on the historical match results within the dataset. Given the available data for each bet—its decimal odds , the bet size , and the actual match outcome —the profit change for each bet is calculated as follows:

where is an indicator function equal to 1 if the final score corresponds to a winning bet, and 0 otherwise.

The total cumulative profit across all bets in the dataset is as follows:

where B represents the set of all bets in the dataset.

However, the observed realised final scores of matches are only one of the possible realisations of uncertain events. To model this uncertainty and the inherent variance, we simulate alternative profit paths based on the estimates of true winning probabilities obtained from each devig method.

Suppose a bet is placed with a predicted probability . We sample a random variable and consider the bet to be a winner if and a loser otherwise. If the bet wins, the player recovers the stake (), multiplied by the decimal odds (netting a profit of ), otherwise the player will lose the original stake. Repeating this process for all bets and summing all the profit changes yields a single simulated trajectory of cumulative profit. By performing repeated iterations, we generate a distribution of simulated cumulative profits for a given method. Pseudo-code to obtain the distribution of possible cumulative profits for one of the devig methods is given in Algorithm 1.

Now we have observed cumulative profit based on bookmaker odds combined with historical match results, and distribution of possible cumulative profits for each method, which is based on bookmaker odds and related probabilities of each method. It is important to note that both the observed profit and the possible profits distribution depend on the payout sizes determined by the bookmaker odds and bets sizes.

Given the historical profit and, for each method m, a distribution of simulated profits , we computed the bias and mean squared error (MSE) as follows:

Since our goal is a relative comparison across methods, we also computed scaled versions of these metrics by normalising each value by the smallest value attained among all methods. Because bias can be either positive or negative, we report the absolute value of the scaled bias in the comparative plots.

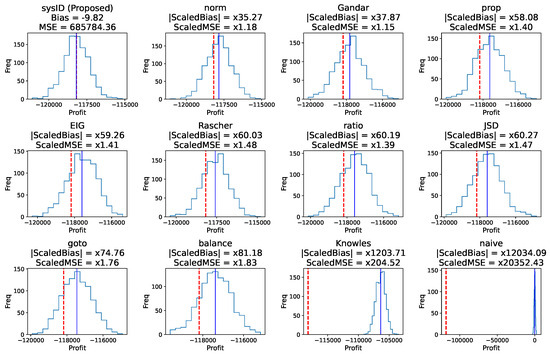

As shown in Figure 5, the proposed method is the best in terms of the smallest bias and MSE, indicating that its expected profit is the closest to the actual observed cumulative profit on a dataset of over three million bets. This suggests that our probability estimates closely approximate the internal probabilities used by the bookmaker when creating odds, effectively removing the margin to recover the implied true probabilities.

| Algorithm 1 Monte Carlo estimation of profits distribution |

|

Figure 5.

Monte Carlo simulations of the cumulative profit distribution based on the predicted probabilities. The dashed red line indicates the actual observed profit, while the solid blue line shows the expected profit of each method, as estimated via simulation. Lower bias and MSE indicate better performance. The plot title for the SysID method shows the estimated bias and MSE, while all other plots show biases and MSEs scaled to the SysID values, e.g., the Rascher method has an MSE 1.48 times greater than the MSE of the SysID.

Furthermore, we observe that both the actual historical profit and the expected profit of all non-naive methods are highly negative. This serves as evidence of bookmaker unfairness and existence of margins. In a perfectly fair market, the expected profit would approach zero, as can be seen in the subplot related to the naive devig method. However, because the bookmaker adds extra margins to fair probabilities, it reduces payout odds, making the player lose their money over a sufficient sample size.

A natural question them arises: if proposed probability estimates are highly accurate, can they be used to generate a profit against the bookmaker? The answer, in this specific context, is no. To generate a positive return on investment (ROI), one’s probability estimates must not only match the bookmaker’s accuracy but exceed it sufficiently to overcome the margin (typically 5–15%, depending on the certainty of bookmaker estimates and other factors). By design, the proposed approach seeks to recover the bookmaker’s estimate, rather than outperform it. Therefore, the best-case scenario is achieving parity with the bookmaker’s accuracy level, which still results in a negative expected value due to the non-zero margins.

4. Discussion

The experimental results showed that the proposed method had the best ECE, Brier score, and log-loss across other existing methods. The proposed method also showed the best results in Monte Carlo simulations of expected profit convergence to the historical profit. We attribute these improvements to the model’s ability to aggregate multiple market groups at the same time so that the proposed model effectively extracts latent information from all observed outcomes.

Despite its advantages, the model has certain limitations. In particular, we cannot strictly prove the existence of a unique minimum, and the proposed method cannot be reliably applied in cases with insufficient market data. In such scenarios, the resulting system of equations becomes under-determined and admits an infinite number of solutions. A simple “rule of thumb” can be used to minimise risk of such problems: for the approach to work effectively, the system must include both (i) standard bet types (e.g., match win outcomes, “both teams to score”, double chances) and (ii) parameterised bets (e.g., totals, handicaps, individual totals), which will reflect both the relative strength of the teams and the magnitude of the number of scored goals.

In addition, we observed a small proportion of cases (less than 1 % of the full dataset) where the system solution exhibited significant residual errors even when all the required markets were present. We simply discarded these data as outliers. These anomalies could be explained due to rare external errors on the side of betting data providers.

The proposed framework opens up several promising avenues for further improvement, as it describes not just one method, but the entire family of about 1000 or more devig methods. First, it can incorporate more complex match models such as the extended Dixon–Coles [22] model or other models. Second, the choice of the optimal method to evaluate , the bet weighting function , and loss function remains an open question and can be further optimised. In practice, the optimal choice may vary depending on the bookmaker, market types, and other factors.

Another extension involves combining data from multiple bookmakers to create a single system with enhanced coverage and predictive power. Theoretically, the belief fusion approach will allow us to create probabilities that are more accurate than the probabilities of each of the bookmakers used, which can lead to obtaining positive expected profit. However, this belief fusion approach also raises the problem of identifying appropriate weighting schemes across bookmakers, which also remains an open research question.

Finally, the generalisability of our method to other sports and stochastic systems represents an interesting topic for research. Many sports share discrete, event-driven scoring structures that lend themselves to Poisson-type domain models, which are conceptually very close to the Dixon–Coles distribution used in this research. Evidence exists for Poisson-based modelling in numerous sports, including hockey [34], basketball [35], handball [36], rugby [37], and water polo [38]. Consequently, these sports can be modelled in a manner similar to football, suggesting that our devig approach can be adapted with minimal modification, since the Dixon–Coles component can be readily replaced by an alternative domain model, as discussed in Section 2.4.2. Sports with more complex scoring rules, such as tennis or table tennis, may require significant structural adjustments to account for the dynamics of point-based sets, making the problem even more interesting.

In summary, our results support the feasibility of extracting well-calibrated probabilities from betting odds using a constraint-based optimisation approach combined with domain knowledge.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a new and more accurate method for recovering bookmakers’ implied estimates of true probabilities of football match outcomes based on bookmakers’ odds. This approach uses domain knowledge, in particular, the well-established Dixon–Coles model, to construct a system of equations that extracts well-calibrated probabilities from observed market odds.

In addition to the proposed methodology, we present a comprehensive review and comparison of multiple alternative devig approaches. To our knowledge, such an aggregation-based devig approach has not been published before, and we believe that it will be useful for both practitioners and researchers in the field of sports modelling.

All experiments were conducted using a custom-built dataset, which is significantly larger than the datasets typically used in comparable sports modelling studies. To support reproducibility and validation, we made the dataset and code used publicly available.

This paper also identifies several promising directions for future research, including improvements to the proposed modelling framework, such as improved error weighting strategies and extension to other sports and domains. We believe that these directions have potential not only for sports analytics, but also for broader applications in probabilistic modelling and market analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.K. (Artur Karimov) and D.B.; Data curation, A.K. (Artur Karimov) and D.B.; Formal analysis, D.K.; Funding acquisition, D.B.; Investigation, A.K. (Aleksandr Koshkin); Methodology, D.B.; Project administration, D.B.; Software, A.K. (Aleksandr Koshkin); Supervision, A.K. (Artur Karimov); Validation, D.K.; Visualisation, A.K. (Aleksandr Koshkin); Writing—original draft, A.K. (Aleksandr Koshkin); Writing—review and editing, D.K. and D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF), project 22-19-00573P.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset and code used are publicly available in the related Github repository https://github.com/cuamckuu/domain-driven-soccer-probs. URL accessed on 10 December 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lorig, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zou, B. Optimal bookmaking. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 295, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowberg, E.; Wolfers, J. Explaining the favorite–long shot bias: Is it risk-love or misperceptions? J. Political Econ. 2010, 118, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, R.D. The state of research on markets for sports betting and suggested future directions. J. Econ. Financ. 2005, 29, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, G.; Sherony, K.; Haupert, M. The demand for Major League Baseball: A test of the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis. Am. Econ. 1992, 36, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.S. Prices of state contingent claims with insider traders, and the favourite-longshot bias. Econ. J. 1992, 102, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascher, D.A. A test of the optimal positive production network externality in Major League Baseball. In Sports, Economics: Current Research; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gandar, J.M.; Zuber, R.A.; Johnson, R.S.; Dare, W. Re-examining the betting market on Major League Baseball games: Is there a reverse favourite-longshot bias? Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K. Fixed-Odds Betting and Traditional Odds. 2025. Available online: https://www.sportstradingnetwork.com/article/fixed-odds-betting-traditional-odds/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Long, C.D. The Jensen–Shannon Distance Method. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/implied/vignettes/introduction.html#the-jensenshannon-distance-method (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Kaito. Gambling Odds To Outcome Probabilities Conversion (Goto_Conversion). Version Released on 2023-08-25. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/gotoConversion/goto_conversion (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Chordia, T.; Roll, R.; Subrahmanyam, A. Liquidity and market efficiency. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 87, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortis, D. Betting Markets: Defining Odds Restrictions, Exploring Market Inefficiencies and Measuring Bookmaker Solvency. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gramm, M.; McKinney, C.N. The effect of late money on betting market efficiency. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2009, 16, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, D.; Ntzoufras, I. Bivariate Poisson and diagonal inflated bivariate Poisson regression models in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2005, 14, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, D.; Ntzoufras, I. Bayesian modelling of football outcomes: Using the Skellam’s distribution for the goal difference. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2009, 20, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, I.; Scarf, P. Modelling soccer matches using bivariate discrete distributions with general dependence structure. Stat. Neerl. 2007, 61, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshnakov, G.; Kharrat, T.; McHale, I.G. A Bivariate Weibull Count Model for Forecasting Association Football Scores. Int. J. Forecast. 2017, 33, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M.J. Modelling association football scores. Stat. Neerl. 1982, 36, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, R.; Ötting, M.; Karlis, D. Extending the Dixon and Coles model: An application to women’s football data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2025, 74, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, I.; Scarf, P. Modelling the dependence of goals scored by opposing teams in international soccer matches. Stat. Model. 2011, 11, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.J.; Coles, S.G. Modelling association football scores and inefficiencies in the football betting market. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1997, 46, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, M.; Dixon, M.; Ledford, A.; Robinson, M. Dynamic modelling and prediction of English Football League matches for betting. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D Stat. 2002, 51, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhough, J.; Birch, P.; Chapman, S.C.; Rowlands, G. Football goal distributions and extremal statistics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2002, 316, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.D.; McHale, I.G. Time varying ratings in association football: The all-time greatest team is. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2015, 178, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, J.P.; Depken, C.A.; Gandar, J.M. The conversion of money lines into win probabilities: Reconciliations and simplifications. J. Sport. Econ. 2018, 19, 990–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchdahl, J. Margin Weights Proportional to the Odds. Described in Buchdahl’s “Wisdom of the Crowd” Document and Referenced in the CRAN Implied Package Vignette. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/implied/vignettes/introduction.html#margin-weights-proportional-to-the-odds (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Andreescu, T.; Mortici, C.; Tetiva, M. The extreme value theorem. In Mathematical Bridges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C.; Joshi, A. Machine learning for sports betting: Should model selection be based on accuracy or calibration? Mach. Learn. Appl. 2024, 16, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Filho, T.; Song, H.; Perello-Nieto, M.; Santos-Rodriguez, R.; Kull, M.; Flach, P. Classifier calibration: A survey on how to assess and improve predicted class probabilities. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 3211–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Multidimensional scaling. In Visualization for Information Retrieval; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Maaten, L.v.d.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, P.; Šedivá, B.; Ťoupal, T. Modeling and prediction of ice hockey match results. J. Quant. Anal. Sport. 2014, 10, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, J.M.; de Saá Guerra, Y.; García-Manso, J.M.; Arriaza, E.; Valverde-Estévez, T. The Poisson model limits in NBA basketball: Complexity in team sports. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2016, 464, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, F. Ranking handball teams from statistical strength estimation. Comput. Stat. 2025, 40, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarf, P.; Parma, R.; McHale, I. On outcome uncertainty and scoring rates in sport: The case of international rugby union. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlis, D.; Ntzoufras, I. Analysis of sports data by using bivariate Poisson models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. D (Stat.) 2003, 52, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).