Abstract

The construction of rational absolute nodal coordinate formulation (RANCF) elements is usually based on a linear transformation of non-uniform rational B-spline (NURBS) geometry. However, this linear transformation can lead to property transfer issues, which greatly reduce the modeling efficiency, especially for conic sections. To overcome this limitation, we first analyze the geometric constraints of conic sections and derive a unique defining equation in rational parametric form. A corresponding degree-elevation formula is also obtained. Using these results, we propose a direct definition method for RANCF elements that explicitly exploits the analytic properties of conic sections. The method provides fast and accurate expressions for the nodal coordinates and weights, and thus enables efficient modeling of RANCF elements for conic-section configurations. We also mitigate the arbitrariness in element definition by introducing, for the first time, the concept of a mapping factor K, which characterizes the mapping between the physical space and the parameter space. Based on this mapping factor, we establish a parameterization procedure for RANCF conic-section elements. An evaluation criterion for K is further proposed and used to define the optimal mapping factor Kopt, which yields an optimal parameterization and allows the construction of Kopt elements. Numerical examples demonstrate that, in large-deformation analyses of flexible systems, the proposed elements can achieve a given accuracy with fewer elements than conventional approaches.

Keywords:

rational absolute nodal coordinate formulation; conic section element; weights; mapping relationship; parameterization MSC:

37M05

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Finite element analysis based on the Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation (ANCF) has undergone decades of development, and its theoretical framework and practical applications have gradually matured [1,2,3,4]. Compared with conventional finite element methods, the ANCF approach offers a series of remarkable advantages. In its system dynamic equations, the mass matrix remains constant, and the corresponding Coriolis and centrifugal terms vanish, with the main nonlinearities arising from the elastic terms [5,6,7,8]. These features endow ANCF with unique potential in the dynamic analysis of structures undergoing large deformations. Since its introduction, the method has attracted continuous attention [9,10,11].

With continuous advances in science and technology, fields such as flexible robotics, vehicle engineering, aerospace structures, and biomedicine are progressively moving toward lightweight, flexible, high-speed, and high-precision designs. Correspondingly, conic sections offer unique advantages in complex surface modeling, stress and wave-field control, and multiphysics coupling problems. Therefore, they play an important role in structural design and performance analysis. However, when applying conventional ANCF to complex curves, limitations remain in terms of geometric accuracy and computational efficiency, making it difficult to fully meet the demands of complex engineering problems [12,13,14]. To address this issue, rational interpolation shape functions need to be introduced to represent curve geometry more accurately and avoid linear approximation errors. This, in turn, enables the development of novel rational absolute nodal coordinate formulation elements and further extends the advantages and applications of ANCF in flexible multibody dynamics [15,16,17].

1.2. Articulation of the Research Problem Relevant to This Investigation

To achieve accurate descriptions of complex curve geometries, Sanborn proposed the Rational Absolute Nodal Coordinate Formulation (RANCF) element [18]. Compared with conventional ANCF elements, RANCF provides better convergence in the dynamic analysis of flexible bodies and enables effective integration of computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided analysis (CAA) through exact linear transformations with Non-Uniform Rational B-Spline (NURBS) geometries [19,20]. However, the construction of RANCF elements relies on the linear transformation of NURBS geometries, which inevitably increases modeling complexity. Moreover, the characteristics of the elements are constrained by the inherent properties of NURBS, thereby limiting their flexibility in applications involving specific curve geometries. As the most fundamental family of quadratic curves, conic sections exhibit smooth curvature distributions and concise parameterization, allowing them to preserve geometric fidelity while avoiding the complexity of NURBS representations. Thus, constructing RANCF elements directly from conic sections provides a feasible approach to enhance the applicability and modeling efficiency of RANCF.

In addition to challenges in geometric representation, RANCF elements also exhibit arbitrariness at the definition level. Due to the introduction of weights, the same geometric configuration may correspond to multiple element definitions, which essentially stem from the non-uniform mapping between physical space and parameter space. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate this mapping mechanism and propose corresponding evaluation criteria to promote the standardization and parameterization of RANCF element definitions. To this end, this paper proposes a direct construction method for RANCF elements based on conic sections and investigates the problem from the perspective of the mapping between physical space and parameter space. The aim is to resolve the non-uniqueness in element definition and to provide methodological support for high-precision modeling of flexible multibody systems with complex curve geometries.

1.3. Review of Related Studies

ANCF was first introduced by Shabana in 1996 [1]. By employing absolute coordinates and position gradients to describe flexible body deformation, ANCF effectively addressed the modeling challenges of large deformation and nonlinear problems in multibody system dynamics, significantly improving modeling accuracy and efficiency. It has been widely applied in fields such as flexible robotics [21,22], vehicle engineering [15,23], aerospace structures [24,25], and biomedicine [26]. At present, ANCF has been integrated into both commercial and open-source software [27], and its influence continues to grow. However, because ANCF employs polynomial interpolation functions, the representation of quadratic curves, such as arcs and conics, typically necessitates additional elements for accurate approximation. This not only introduces fitting errors but also demands significant mesh refinement in large-scale simulations to reduce geometric approximation errors. Against this background, Sanborn proposed the RANCF element [18].

By introducing denominator polynomials and weights to construct rational interpolation functions, RANCF significantly improves geometric modeling accuracy and enhances the flexibility of element description. Within a prescribed error tolerance, RANCF can achieve target accuracy with fewer elements, thereby reducing computational cost and storage requirements. In recent years, RANCF has received increasing attention. Based on the endpoint and derivative properties of Bézier curves, Yu et al. [28] established a linear transformation between ANCF one-dimensional beam elements and Bézier curves. In subsequent research [29], NURBS curves were transformed into RANCF cable elements through linear mapping, with discussions on continuity control and mesh refinement. Guo et al. [30] developed rational Bézier planar beam elements capable of accurately representing quadratic curves. Yu, Pappalardo, and others [31,32] compared RANCF with conventional approaches for thin-plate elements, demonstrating the advantages of RANCF in surface modeling. Ma et al. [33,34] further proposed four-node three-dimensional RANCF plate elements, eight-node solid elements, and three-dimensional fluid elements, validating their superior convergence properties. Ding et al. [35] developed a variable-length ALE-RANCF method, combining ALE-ANCF with RANCF to achieve the exact representation of rational cubic Bézier curves. Overall, the construction of existing RANCF elements primarily depends on the linear transformation from NURBS basis functions, control points, and weights to RANCF nodal vectors [36,37,38].

Nevertheless, NURBS control points and weights lack intuitive correspondence with geometric parameters, resulting in inefficient parameter-iterative numerical optimization, which is unfavorable for large-scale engineering applications. Moreover, existing transformations mainly focus on geometric accuracy, while the treatment of gradient continuity and mechanical coupling relies on additional constraints and nodal configurations [39,40]. To ensure gradient continuity, it is often necessary to adjust NURBS knot multiplicity before transformation or introduce extra constraint equations afterward, further increasing modeling complexity [41]. Consequently, developing RANCF elements directly defined by geometric parameters has become an urgent issue. Some attempts have already been made in this direction. Zhang et al. [20] proposed a RANCF arc section element based on geometric parameters, and Shi et al. [42] further provided precise subdivision methods for arc section elements in physical space. These studies offer valuable insights into the direct definition of RANCF elements.

However, while arc section elements address the exact representation of circles, other quadratic curves such as parabolas, ellipses, and hyperbolas still require approximate discretization, which compromises analytical precision. This deviates from the original intention of RANCF to achieve high-fidelity modeling of complex curve geometries, and therefore can only serve as a transitional solution. By contrast, conic sections, as the most fundamental quadratic family, possess smooth curvature distributions and simple parameterization, and can degenerate into straight lines under specific conditions. Thus, they provide a more systematic and comprehensive foundation for modeling complex curve geometries. The development of RANCF elements based on conic sections is not only essentially different from arc section elements in methodology, but also better aligned with the original intention of RANCF to accurately describe complex curve geometries. Furthermore, current research lacks systematic quantitative evaluation criteria and consistency measures for the mapping between parameter and physical spaces, which is of great significance for the standardization and evaluation of RANCF elements.

In addition to ANCF- and RANCF-based formulations, there is also a substantial body of work on isogeometric analysis (IGA) [43,44], as well as closely related NURBS-enhanced finite element methods (NEFEM) [45], in which NURBS or other rational spline spaces are used to represent the geometry (and, in IGA, also the solution field) within a unified framework. In particular, NURBS are able to exactly represent all conic sections and are widely employed in CAD-based IGA formulations for the structural analysis of beams, shells, and other curved components, while NEFEM uses NURBS descriptions of curved boundaries (such as circular arcs) in combination with standard polynomial shape functions in the interior of the elements. These approaches typically construct global NURBS patches or spline curves and perform analysis directly on the resulting spline space, with geometric refinement realized through knot insertion and degree elevation. Although such methods provide excellent geometric fidelity and high-order continuity, they usually do not introduce an explicit element-level geometric parameter to control the mapping between the parametric and physical spaces, nor do they address, at the finite-element level, the arbitrariness associated with the choice of nodal weights as in RANCF-type elements.

1.4. Scope and Significance of This Research

The advantage of RANCF elements lies in their capability to model complex curve geometries. To overcome the reliance on NURBS-based linear transformations in RANCF element construction, this study proposes a direct definition method for RANCF elements based on conic sections. In RANCF analysis, this method enables the direct definition of conic sections, together with standardized, parameterized, and evaluation criteria.

The proposed approach exploits the analytical properties of conic sections to define RANCF elements, simplifying the adjustment of continuity conditions between elements and the application of constraint equations during preprocessing. Compared with NURBS-based approaches that rely on a linear mapping between the element and the underlying NURBS geometry, the present method is not constrained by the intrinsic features of the NURBS representation, such as the control polygon, knot vector, and weight distribution. At the same time, it simplifies the preprocessing required for engineering implementation, reduces the discretization effort, and improves the overall modeling efficiency. In NURBS-based curve joining, equal weights at connection points and specific continuity conditions are usually required. By introducing standardized RANCF conic section elements, this study proposes their explicit definition and formulation, thereby simplifying continuity enforcement across elements.

Unlike RANCF arc section elements, RANCF conic section elements can represent arbitrary quadratic curves and their degenerate forms, with arc section elements being only a special case. Although standardization reduces subjectivity, the element definition still depends on the relationship between weights and nodal coordinates, leading to differences in mapping between physical and parameter spaces across different definitions. To address this issue, this study introduces, for the first time, the concept of a mapping factor and proposes a parameterization scheme for standardized RANCF conic section elements, together with evaluation criteria. By employing optimized standardized RANCF conic section elements, fewer meshes are required to achieve the same error tolerance, and convergence is faster. This provides a practical option for large-scale or complex models.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A direct definition method for RANCF conic section elements is proposed based on the analytical properties of conic sections, together with the derivation of nodal vector formulations.

- (2)

- Standardization criteria for RANCF conic section elements are introduced, which in most cases eliminate the need for additional constraint equations during preprocessing, thereby improving efficiency.

- (3)

- A parameterization method for standardized RANCF conic section elements is proposed, in which the concept of a mapping factor K is introduced for the first time, together with its corresponding parameterization framework.

- (4)

- The influence of K on element weights, shape functions, and gradients is systematically analyzed, and the concept of an optimal mapping factor Kopt is introduced to identify the most effective standardized RANCF conic section element.

Finally, numerical examples of planar and spatial pendulums, together with the free and resonant forced vibrations of an initially curved elliptical-arc cable, are presented to validate the feasibility and accuracy of the proposed method. Comparisons with ANCF results further demonstrate its advantages in terms of both accuracy and efficiency. Moreover, the standardized RANCF conic-section element enhances the theoretical foundation of the RANCF methodology and lays a solid basis for its application in flexible multibody dynamics and engineering practice.

1.5. Paper Outline

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the geometric description and definitions of conic sections, discusses their geometric constraints, and derives the unique rational parametric representation and the corresponding degree-elevation formulas. Section 3 presents the direct definition of standardized RANCF conic section elements based on the intuitive geometric characteristics of conics, together with the expressions of weights and nodal coordinates. Section 4 describes the parameterization method and evaluation criteria for standardized RANCF conic section elements. Section 5 develops the dynamic equations of the proposed elements. Section 6 provides numerical examples and analyses to validate the proposed method. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the core contributions of this work.

2. Rational Parametric Representation of Conic Sections

2.1. Unique Definition of Conic Sections in Rational Parametric Form

For any planar conic, an implicit representation is typically used in analytic geometry, as shown in Equation (1):

Equation (1) involves six coefficients, A, B, C, D, E, and F, of which five are independent. Therefore, any planar conic can be uniquely defined by five constraints. However, the implicit representation depends on the choice of coordinate system, and its coefficients have no straightforward geometric interpretation; thus, the implicit form is often inconvenient in practice.

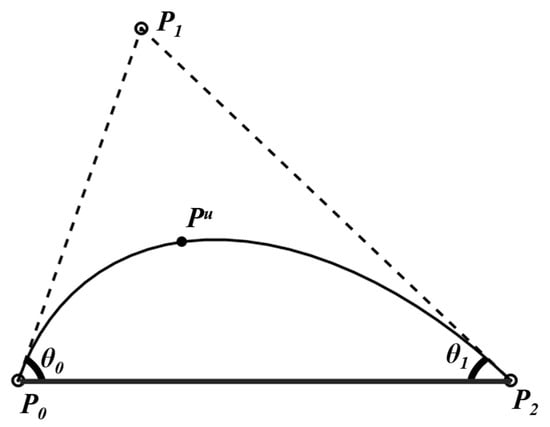

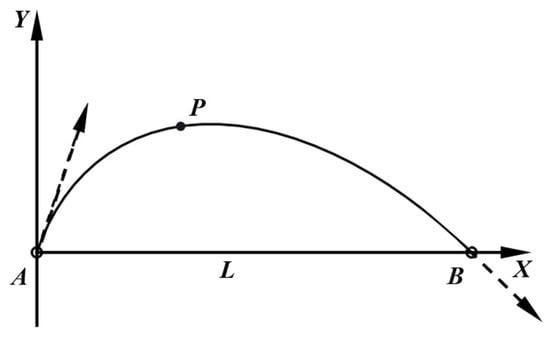

A coordinate-independent description of conic sections in a two-dimensional plane, as illustrated in Figure 1, is constructed. The following conditions are introduced:

Figure 1.

Description of a conic section in the plane.

- (1)

- The endpoints of the conic are P0, P1 ∈.

- (2)

- The angles between the tangents at P0 and P2 and the chord of the conic are θ0 and θ1, with θ0 < 90° and θ1 < 90°.

- (3)

- An arbitrary point Pu lies on the conic, with Pu ≠ P0, Pu ≠ P2, and Pu ∈.

By definition, the intersection of the tangents at P0 and P2 is P1. Suppose P0 = (x0, y0) and P2 = (x2, y2). Then P1 = (x1, y1) can be expressed as:

Under the given conditions, the rational parametric form of the quadratic conic shown in Figure 1 can be expressed as in Equation (3):

where u ∈ [0, 1] denotes the parameter; r(u) is the position vector, and ωi ∈ (i = 0, 1, 2) are the weights.

Equation (3) provides an exact representation of any conic in the plane and is independent of the choice of coordinate system. Equation (3) conforms to the quadratic rational Bézier form. By the properties of quadratic rational Bézier curves, the weights ωi satisfy the constraint in Equation (4).

where κ denotes the shape-invariant factor.

From Equation (4), the weights ωi constitute a non-unique parameter set, whereas κ uniquely characterizes the shape. The non-uniqueness of the weight set ωi complicates the unique definition of an arbitrary planar conic. By setting ω0 = ω2 = 1, Equation (3) becomes the standard rational parametric representation of a conic. In this case, because κ is unique, Equation (4) yields a unique expression for ω2.

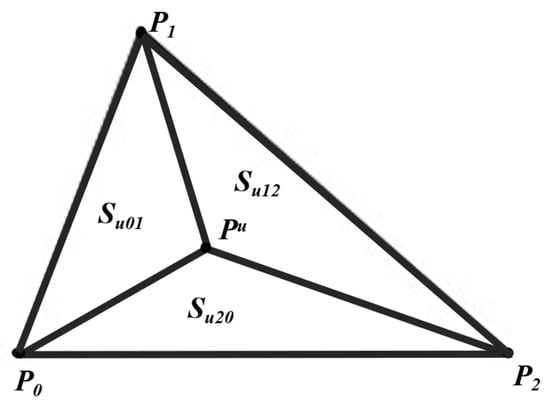

To obtain the expression for ω2 from the given conditions, P0, P1, and P2 are connected pairwise to form ΔP0P1P2, referred to as the convex-hull triangle, with Pu located inside ΔP0P1P2. Then, Pu is connected to P0, P1, and P2 to form ΔPuP0P1, ΔPuP1P2, and ΔPuP2P0, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the construction of the barycentric coordinates of point Pu with respect to the convex hull triangle ΔP0P1P2.

For a point Pu inside ΔP0P1P2, its barycentric coordinates with respect to ΔP0P1P2 are given in Equation (5).

where λ0, λ1, λ2 ∈ denote the barycentric coordinate parameters and satisfy λ0 + λ1 + λ2 = 1; λ0, λ1, λ2 are computed by Equation (6).

where S012, Su12, Su01 and Su20 denote the signed areas of ΔP0P1P2, ΔPuP1P2, ΔPuP0P1, and ΔPuP2P0, respectively.

Substituting Pu and ω0 = ω2 =1 into Equation (3) yields:

where denotes the parameter value in the parametric space corresponding to Pu and is unknown.

Aligning Equations (5) and (7) yields the following proportional relations:

Dividing 1 − λ0 − λ2 by λ2 yields:

Bringing ω1 to the left-hand side and rearranging gives:

Dividing λ2 by λ0 yields:

Substituting Equation (11) into Equation (10) eliminates the unknown parameter ; rearranging yields the following expression of ω1 in terms of the barycentric coordinates λ0, λ1, λ2 of Pu:

For Equation (12), the barycentric parameters λ0, λ1, λ2 depend on the choice of the point Pu on an arbitrary planar conic. Nevertheless, regardless of the point Pu chosen on the conic, the same weight ω1 is obtained. Substituting Equation (12) together with ω0 = ω2 = 1 into Equation (3) yields the unique form of Equation (13). Therefore, given the endpoints P0 and P2, the angles θ0 and θ1 between the tangents at P0 and P2 and the conic, and any point Pu on the conic, the quadratic rational parametric equation of the conic is uniquely determined.

2.2. Degree Elevation Method of Conic Sections Defined by Rational Parametric Equations

It follows from Section 2.1 that the unique defining equation of a conic section in rational parametric form is given as follows:

where λi satisfies λi = λi(u) (i = 0, 1, 2). For Equation (13), when the parameter is set to with , substituting into Equation (13) yields a point on the conic. Substituting into Equation (6) gives its barycentric coordinates and with respect to ΔP0P1P2. Equation (13) conforms to the quadratic rational Bézier form. By properties of rational Bézier curves, a higher-degree rational Bézier curve has sufficient freedom to represent or approximate any lower-degree rational Bézier curve. Therefore, via degree elevation, the cubic rational Bézier parametric equation in Equation (14) can be used to represent the conic defined by Equation (13).

where u ∈ [0, 1] denotes the parameter of the cubic rational Bézier curve; r(u) is the position vector; denotes the weights after degree elevation.; and Qi denotes the control points after degree elevation.

By applying the degree-elevation and weight-transformation formulas of rational Bézier curves to Equation (14), the weights of the conic represented by Equation (15) are obtained as:

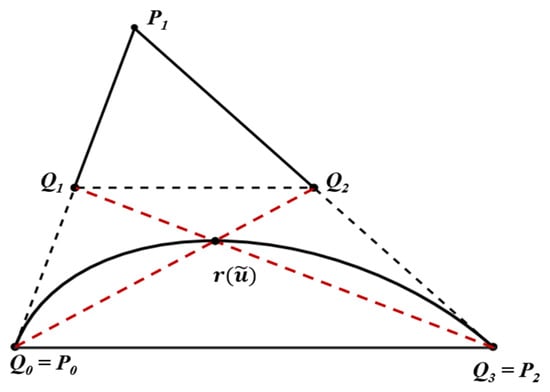

The Qi can be constructed on the basis of Figure 1 using the construction derived from the projection relation of rational Bézier curves. The intersection of the line through P0 and with the line through P1 and P2 gives the interior control point Q2 of the cubic rational Bézier conic. Likewise, the intersection of the line through P2 and with the line through P0 and P1 gives the interior control point Q1 of the standard-form cubic rational Bézier conic. The expressions for Q1 and Q2 follow the same principles as the computation of P1 in Section 2.1. After degree elevation, the endpoints remain unchanged, with Q0 = P0 and Q3 = P2, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of constructing Qi using the projection relation in degree elevation.

Substituting the obtained weights and control points into Equation (14) yields the degree-elevated representation of the conic in rational parametric form. The degree-elevated representation is not unique: as varies, changes, which in turn yields different Q1, Q2, and the corresponding weights. RANCF is obtained by conversion from a cubic Bézier form. Converting Equation (14) to the RANCF enables a direct definition of the RANCF conic section element; moreover, by varying , a geometry-invariant parameterization of the RANCF conic section element is achieved.

3. Construction Method of RANCF Conic Section Elements

3.1. RANCF Cable Element

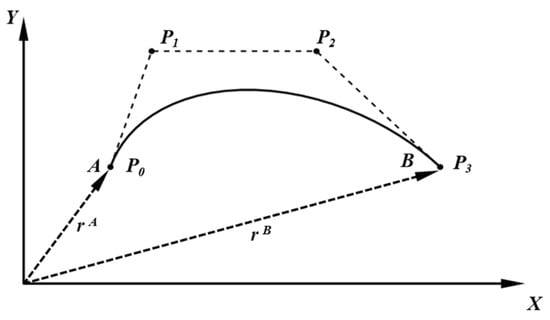

The basis functions of the rational Bézier curve are recast as finite element shape functions, and its control points are assigned to the nodal coordinates of the RANCF element. This transformation converts the geometric representation into a finite element formulation with mechanical meaning, thereby enabling the construction of the RANCF element. Figure 4 depicts the connection between the RANCF element and the rational Bézier curve.

Figure 4.

Relationship between rational Bézier curves and RANCF.

The RANCF element inherits the weights of the rational Bézier curve and thus the non-uniqueness of the weight-parameter set. The non-uniqueness allows the same geometry to be discretized using multiple element definitions in RANCF modeling; while this offers flexibility, it also introduces arbitrariness in element definition. Such arbitrariness can reduce geometric fidelity, cause inconsistencies in simulation results, and impair reproducibility and computational efficiency. The standard RANCF element is derived from the conventional RANCF element via a unified construction strategy and a parameterized representation. This standardization markedly reduces subjectivity in modeling, improves consistency, generality, and numerical stability, and lays the groundwork for engineering applications of RANCF.

For a conventional RANCF element, the displacement field is given by:

where Sr(ξ) is the element shape-function matrix expressed in the parametric coordinate ξ with ξ; e(t) is the vector of element nodal coordinates, consisting of absolute position coordinates and gradient coordinates; and t denotes time.

This paper focuses solely on cable elements. For the RANCF cable element, Sr(u) can be computed using Equations (17)–(20).

where I denotes the 3 × 3 identity matrix; l is the element length; are the weights of the RANCF element; and are the binomial coefficients of the cubic Bernstein basis; Bi,3(ξ) denotes the cubic Bézier (Bernstein) basis functions, while Ri,3(ξ) denotes the corresponding rational basis functions.

As shown in Figure 4, for the RANCF cable element, the element nodal coordinate vector e(t) consists of the global position coordinates and of the two end nodes and the gradient coordinates and , collectively forming the nodal DOFs, where x is the material coordinate; the expression of e(t) is given in Equation (21).

where and are given by the global coordinates of points A and B; and are computed by the following equations.

For Equation (16), when , the element is defined as the standard RANCF cable element. During element assembly, the standard RANCF cable element does not require weight adjustments at shared nodes, enabling convenient and efficient enforcement of inter-element continuity.

3.2. Standard RANCF Conic Section Element

In engineering practice, the construction and representation of free-form curves, particularly quadratic ones, are extensively employed. Among these, conic sections, including ellipses, hyperbolas, and parabolas, are of significant theoretical and practical importance. Therefore, establishing a unified, computationally tractable standard representation of conic sections is of great significance for finite element modeling and multibody system dynamics analysis.

This section presents a method for defining conic sections based on the standard RANCF cable element, achieving geometric accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency and structural continuity. To ensure generality and simplicity of the derivation, a local planar coordinate system is introduced, as shown in Figure 5. In practical problems, the following intuitive geometric parameters are readily available: the chord length, the tangent directions at the two endpoints, and an interior point on the curve distinct from the endpoints. Within this coordinate system, a unified parametric expression of the standard RANCF conic section element is derived.

Figure 5.

Local coordinate system for the standard RANCF conic section.

From Figure 5, the chord length of the conic is L, yielding the endpoint coordinates and . From the tangent directions at the endpoints, the angles between the endpoint tangents and the chord are θ0 and θ1, respectively. An interior point on the curve, distinct from the endpoints, has coordinates . As established in Section 2, the conic shown in Figure 5 admits a unique quadratic rational parametric representation given by:

where ; ; ; ; is derived from Equation (12):

Choose any , substituting into Equation (23) yields a point on the curve. Following Section 2.2, Equation (23) is degree-elevated to obtain a cubic rational parametric representation of the conic. The resulting cubic rational parametric equation satisfies the conversion relation in Section 3.1 between the standard RANCF cable element and the rational Bézier curve. By applying the construction principle of the standardized RANCF cable element in Section 3.1, the cubic rational parametric form is transformed into a standard RANCF cable element, which leads to the formulation of the standardized RANCF conic section element. This element, referred to as the standard RANCF conic section element, provides the following nodal-coordinate representation for the conic in Figure 5:

where L denotes the chord length; l denotes the element length, which for a general conic section is usually computed numerically; and are derived from Equation (15):

In practical applications, the standard RANCF conic section element constructed in the 2D local coordinate system of Figure 5 can be transformed to the 3D global coordinate system using a homogeneous spatial transformation matrix, thereby facilitating the construction of the spatial standard RANCF conic section element.

4. Selection of RANCF Conic Section Elements

4.1. Arbitrariness Problem in RANCF Element Definition

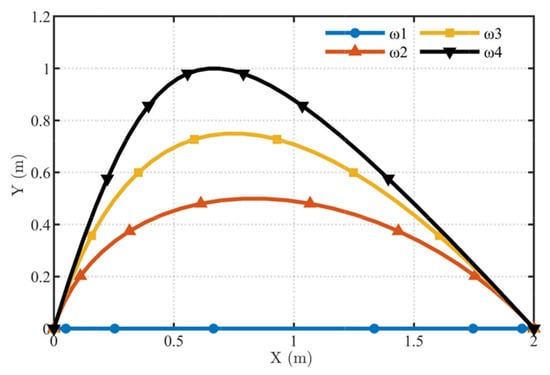

In RANCF, the introduction of a weight-parameter set brings weight coefficients into the definition of the element nodal coordinates. For identical nodal coordinates, using different weight sets leads to geometric distortion. As shown in Figure 6, four standard RANCF conic section elements produce different geometries when assigned different weight sets. In the special case where the interior weight equals 1, the curve reduces to a straight line.

Figure 6.

Geometric configurations corresponding to different weight sets.

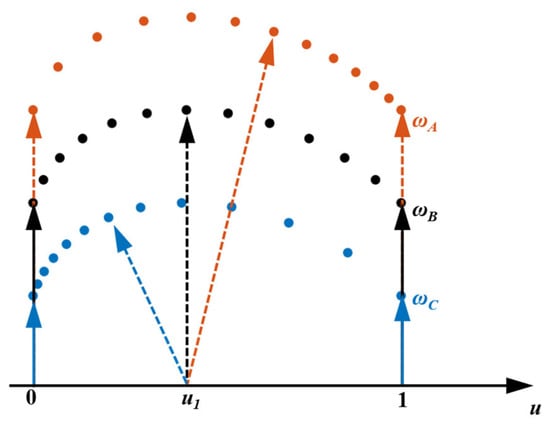

Similarly, standard RANCF conic section elements with different weight assignments can represent the same geometric configuration. As shown in Figure 7, three weight sets that satisfy the definition of the standard RANCF conic section element yield the same geometric description. This leads to diversity and arbitrariness in the definition of RANCF elements. For standard RANCF conic section elements that describe the same geometry but are defined by different weight sets, the displacement field prescribed by RANCF reveals different mappings between the parametric and physical spaces, as illustrated in Figure 7. For such elements, the mapping between the parametric and physical spaces coincides at the endpoint parameters 0 and 1. However, at an interior parameter , the mapping between the parametric and physical spaces differs substantially across definitions.

Figure 7.

Mapping between the parameter and physical spaces for RANCF elements with different definitions.

4.2. Mapping Factor of RANCF Conic Section Elements

The displacement field of the standard RANCF conic section element is given in Equation (27), where ξ ∈ [0, 1] denotes the parametric domain.

As shown in Section 3.2, the definition of the standard RANCF conic section element depends on the parameter value in Equation (23) corresponding to an interior point on the conic distinct from the endpoints. Different values of affect the mapping from the parametric coordinate ξ to the physical space r(ξ) of the standard RANCF conic section element. Therefore, we define the parameter as the mapping factor of the standard RANCF conic section element, denoted by K, with K ∈ (0,1). K can be used to characterize the mapping from ξ to r(ξ) and to parameterize the standard RANCF conic section element. Chávez-Pichardo et al. revisit the general planar conic equation and develop an invariant-based framework centered on the conic radical R [46], which enables purely algebraic, angle-free reduction of quadratics with mixed terms and provides a unified basis for conic classification in analytic geometry. In contrast, the parameter K introduced in the present work is not a geometric invariant of the conic itself, but rather a parametric quantity associated with the choice of element-level parameterization. Despite its parametric nature, K admits a clear geometric interpretation: it quantifies the distribution of the parametric coordinate along the conic segment and thereby directly controls the local stretching and compression of the mapping between the parametric domain and the physical curve. As implied by the definition in Section 3.2, different values of K influence not only the element weights but, through these weights, also alter the element shape functions and their gradients. Since an explicit analytical relation between K and the weights, shape functions, and gradients cannot be established, we investigate their trends numerically. It should be noted that, unlike traditional parameterization strategies (such as chord-length or centripetal parameterizations), the mapping factor K is an explicit element-level parameter that directly controls the mapping between the parameter space and the physical curve.

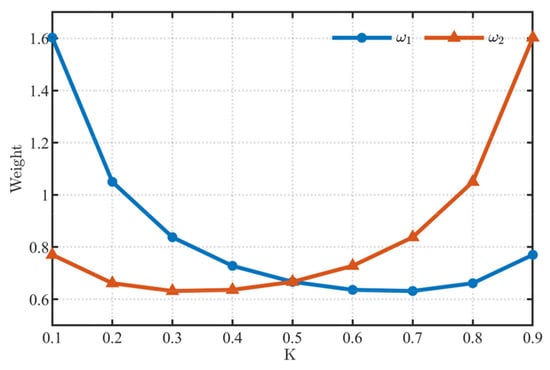

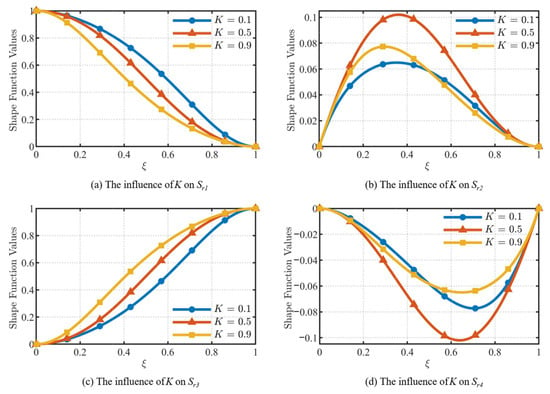

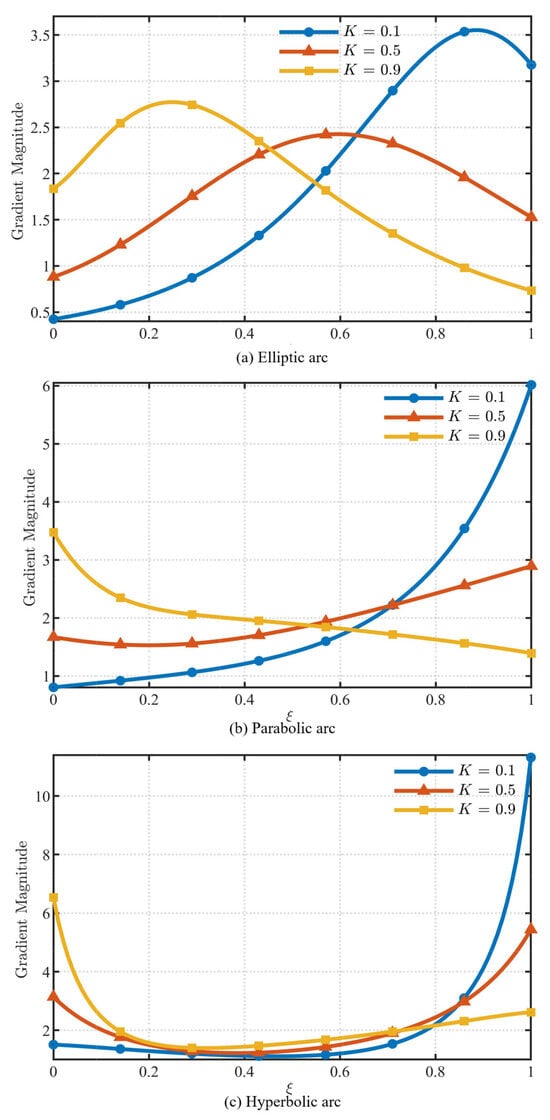

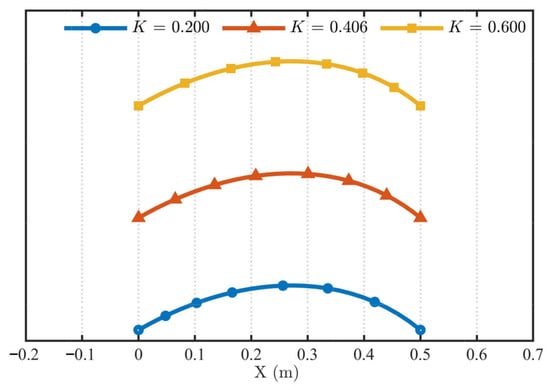

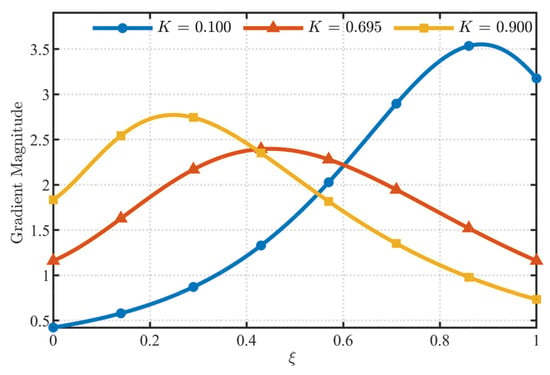

Figure 8 shows how K affects the weights under a fixed initial geometric configuration. For the standardized RANCF conic section element defined in this paper, the endpoint weights satisfy ω0 = ω3 = 1 and remain unchanged across different element definitions. As K increases, the interior weight ω1 first decreases sharply and then increases gradually. For the interior weight ω2, as K increases, it first decreases gradually and then increases markedly, indicating a nonmonotonic dependence of the interior weights on K. When K = 0.5, the interior weights are equal, i.e., ω1 = ω2. From the shape-function formulas of the standard RANCF cable element in Section 3.1, K affects the shape functions by altering the interior weights. Figure 9 illustrates how K influences the shape functions under the same fixed geometry. For the shape functions Sr1 and Sr3, as K increases, Sr1 decreases gradually, whereas Sr3 increases gradually. For Sr2 and Sr4, at intermediate values of K, Sr2 tends to be larger while Sr4 tends to be smaller. Both exhibit nonmonotonic behavior. The influence of K on the weights and shape functions does not have a direct physical interpretation. Its physical implication manifests through the effect on the gradient of the RANCF element’s nodal-coordinate field. Figure 10 shows, for elliptical (θ0 = 30°, θ1 = 60°, L = 0.5 m, X = 0.219 m, Y = 0.072 m), parabolic (θ0 = 30°, θ1 = 60°, L = 0.5 m, X = 0.196 m, Y = 0.108 m), and hyperbolic (θ0 = 30°, θ1 = 60°, L = 0.5 m, X = 0.159 m, Y = 0.144 m) configurations, how the choice of K affects the gradient magnitude at arbitrary points of the standard RANCF conic section element. It is observed that for intermediate K, the gradient varies less across the parametric domain, yielding the most uniform gradient distribution. Therefore, the relationship between the gradient ratio and K is established to be unimodal.

Figure 8.

Influence of K on the weights.

Figure 9.

Influence of K on the shape functions.

Figure 10.

Influence of K on the gradients for different geometric configurations.

4.3. Optimal Standard RANCF Conic Section Element

For a RANCF element, the internal gradient parameter is obtained by differentiating the global position vector with respect to the material coordinate. Defining the element length as l and , the element-wise gradient is given by:

The gradient magnitude reflects the element’s internal stretch and compression. For a RANCF element, an ideal state is defined when the internal gradient is uniform and identical everywhere, i.e., constant for any ξ. However, the introduction of rational weights in RANCF means that different element definitions for the same geometry can yield different internal gradients. Accordingly, a gradient ratio is introduced to evaluate the parameter K of the standard RANCF conic section element [20], as given in Equation (29).

where denotes the maximum gradient magnitude over the element, and denotes the minimum gradient magnitude.

From Equation (29), when the gradient ratio equals 1, the ideal state is attained. This corresponds to a proportional partition between the parametric and physical spaces of the conic, i.e., arc-length parameterization. However, because RANCF elements use a rational polynomial representation, the arc length cannot be used directly. Therefore, when the value computed from Equation (29) approaches 1, the element is deemed to be in the ideal state. The factor K serves to parameterize the standard RANCF conic section element and to reflect the mapping from the parametric coordinate ξ to the physical space . When the result of Equation (29) approaches 1, the corresponding K is termed the optimal mapping factor, denoted Kopt. The standard RANCF conic section element associated with Kopt is referred to as the Kopt -element. Since K is the sole control variable for parameterization and the function relating K to the gradient ratio is unimodal, Kopt can be located efficiently.

5. Equations of Motion of RANCF Conic Section Elements

With a fixed value of K, the weights within the conic section element are constant. The same rational interpolation shape functions are thus obtained, ensuring accurate representation of the described geometry. Using large-strain theory to formulate the elastic forces, the large-deformation and finite-rotation analyses of the standard RANCF conic section element are equivalent to those of the standardized RANCF cable element.

Because the shape functions of the standard RANCF conic section element can accurately describe rigid-body deformation and motion, the global position vector r can be obtained from them and the element nodal coordinates. Differentiating r with respect to time t yields the velocity vector at any point in the element as:

With constant weights, a continuum-mechanics formulation is adopted. In the expression, the shape-function matrix Sr is time-invariant . Therefore, it can be written in the following form:

The variation of the position vector is given by:

Furthermore, the acceleration vector at an arbitrary point on the centerline is:

These kinematic relations will be used to determine the inertia and elastic forces of the RANCF conic section element.

5.1. Mass Matrix of RANCF Conic Section Elements

The kinetic energy of the element is given by:

where ρ denotes the material mass density of the element and V is the element volume. Since the element nodal velocity vector is constant over the entire integration domain, this can be further written as:

where M is the element mass matrix, given by:

For the standard RANCF conic section element, once K is specified, the shape functions are uniquely determined. The mass matrix of the standard RANCF conic section element depends only on material density and geometric size; it inherits the same advantages as ANCF, yielding a constant mass matrix with no Coriolis or centrifugal terms. Therefore, during numerical integration it typically needs to be evaluated only once, greatly improving computational efficiency.

5.2. Elastic Forces of RANCF Conic Section Elements

RANCF is a further extension of ANCF and likewise does not employ a floating nodal frame. It uses continuum mechanics to describe element deformation and to obtain the elastic force vector and the stiffness matrix. Because the conic section element has a curved-beam initial configuration, initial stress relief must be accounted for when formulating the elastic force vector and the stiffness matrix.

Taking the partial derivative of the strain energy of the standard RANCF conic section element with respect to the element nodal coordinates e yields the elastic force expression, as given in Equation (36).

where denotes the Green–Lagrange strain; κ is the curvature computed by Equation (37); e0 is the initial nodal coordinate vector; κ0 is the initial curvature; E is Young’s modulus; A is the cross-sectional area; l is the element length; and I is the second moment of area.

5.3. Generalized Forces of RANCF Conic Section Elements

When external forces act on the standard RANCF conic section element, the dot product of the external force F and the virtual displacement gives the virtual work . The virtual work of the external forces can be expressed as:

Consequently, the generalized forces corresponding to the generalized coordinates of the standard RANCF conic section element are given by:

In the numerical examples, gravity is applied as the external load, and the corresponding generalized gravitational force is derived below. For the standard RANCF conic section element, during motion, the gravitational force G acting on an infinitesimal element volume at any point is given by:

where ρ denotes the material mass density of the element, and g is the gravitational acceleration.

The generalized gravitational force over the entire standard RANCF conic section element is given by:

6. Examples and Result

The definition and parameterization method of the standard RANCF conic-section element proposed in this study enable the direct construction of standard RANCF conic-section elements using intuitive geometric parameters of conic sections, while the parameterization and evaluation are achieved through the mapping factor K. To verify the definition and parameterization method of the standard RANCF conic-section element, numerical analyses are carried out on a planar pendulum of an elliptical-arc cable, on the free and forced vibrations of an initially curved elliptical-arc cable, and on a flexible elliptical-arc cable spatial pendulum.

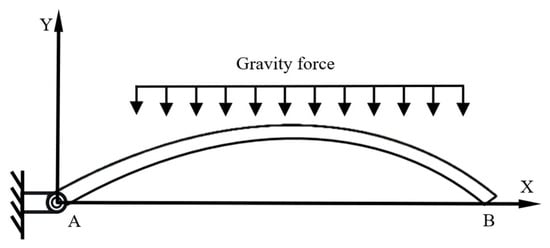

6.1. Planar Pendulum with an Elliptical-Arc Cable

The first example is a planar pendulum with an elliptical-arc cable, shown in Figure 11. The geometric parameters are θ0 = 30°, θ0 = 40°, L = 0.5 m; the elliptical arc passes through the point with coordinates X = 0.315 m, Y = 0.077 m. The cable has a circular cross-section with radius 0.02 m, and point A is hinged. Since RANCF is widely used in flexible multibody dynamics, flexible material parameters are adopted. The density is 6000 kg/m3 and the Young’s modulus is 2 × 106 N/m2. The elliptical-arc cable is released under gravity only, and the straight-line distance AB is monitored. The system is discretized using standard RANCF conic section elements. From Equation (27), Kopt = 0.406 is obtained for Figure 11; K = 0.2 and K = 0.6 are chosen for comparison. Accordingly, the pendulum is discretized using three standard RANCF conic section element definitions (with these K values), and their convergence is compared.

Figure 11.

Schematic of the planar pendulum with an elliptical-arc cable.

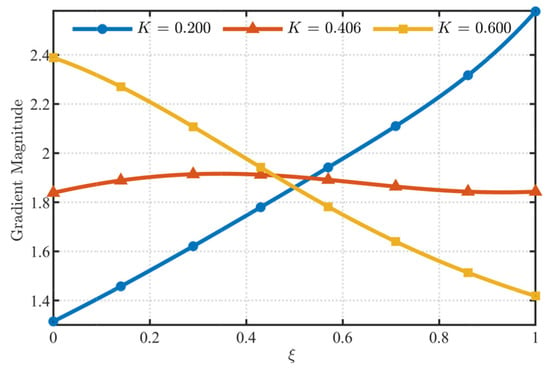

Figure 12 and Figure 13 present the gradient curves and parameter distributions of RANCF conic section elements for different values of K. From Figure 12 and Figure 13, it is observed that at K = 0.406 the corresponding RANCF conic section element exhibits the smallest variation in the gradient curve and a more uniform distribution of parameter points than the other two definitions. Furthermore, the computed gradient ratios for K = 0.2, K = 0.406, and K = 0.6 are 1.96, 1.04, and 1.68, respectively. It can be seen that the gradient ratio at K = 0.406 is closest to 1.

Figure 12.

Gradient curves for Example 1.

Figure 13.

Parameter distributions for Example 1.

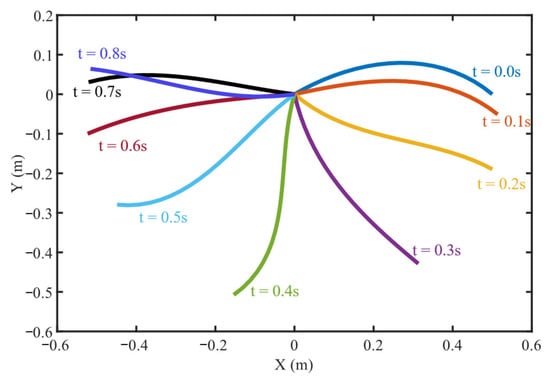

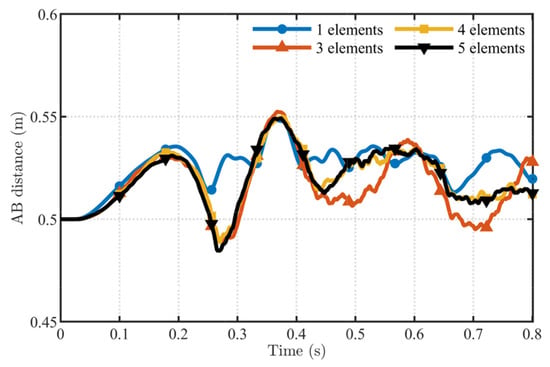

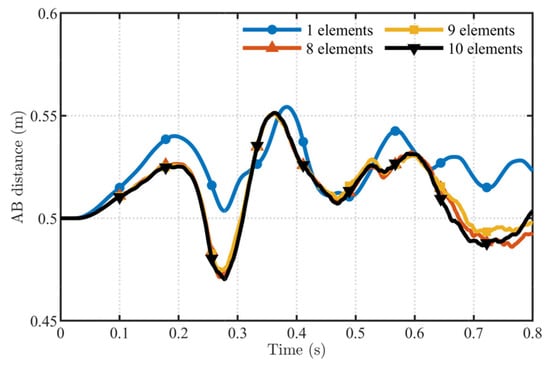

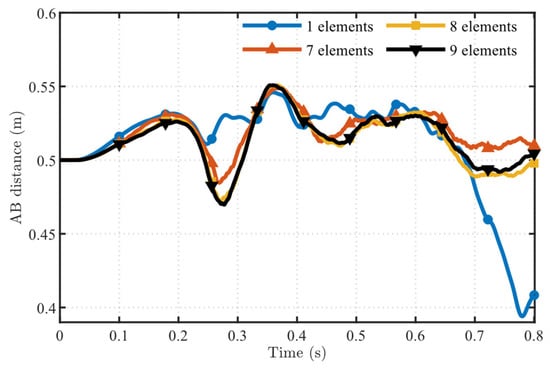

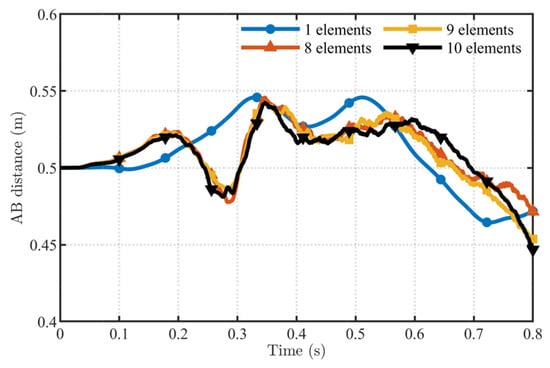

Figure 14 presents the cable configurations at different times when simulated with the optimal RANCF conic section element. Figure 15 shows the variation of the straight-line distance AB between the endpoints in Figure 11 as the cable deforms under gravity. Figure 15 reports the results obtained using the optimally parameterized RANCF conic section element. Figure 16 and Figure 17, respectively, show the convergence of the solutions obtained with the standard RANCF conic section element for K = 0.2 and K = 0.6.

Figure 14.

Cable configurations at different times for Example 1.

Figure 15.

Convergence assessment for Kopt = 0.406.

Figure 16.

Convergence assessment for K = 0.2.

Figure 17.

Convergence assessment for K = 0.6.

The variations of the straight-line distance AB for the three RANCF elements are shown in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17. It can be observed that, as the number of elements increases, the curves depicting the change of the endpoint distance AB become increasingly close. This demonstrates the convergence of the RANCF conic section element. As seen from the comparisons in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, the optimally parameterized RANCF element converges faster than the non-optimal parameterizations. Element definitions that exhibit non-uniform distributions of parameter points require more elements to achieve convergence.

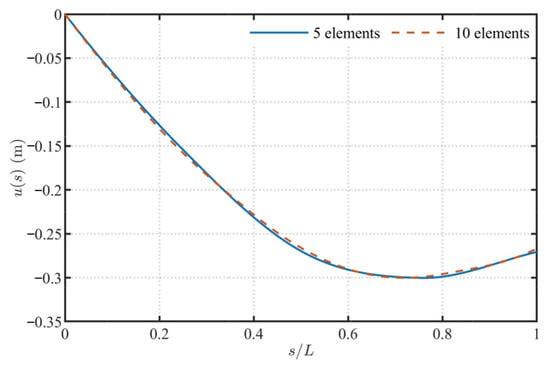

To examine the mesh sensitivity of the proposed element in spatial discretization, a mesh refinement study is carried out for the same gravity-loaded elliptical cable with K = 0.406. Only the number of elements is varied, and two discretizations with 5 and 10 elements are compared. In the computations, the solution obtained with 10 elements is taken as the reference, and its vertical centerline displacement (deflection) is denoted by uz(10)(s), whereas the solution with 5 elements is denoted by uz(5)(s).

Figure 18 shows the distribution of the vertical centerline displacement uz(s) along the arc length at the intermediate time t = 0.5 s, where the results of the two meshes are compared. It can be seen that the two curves almost exactly coincide over the entire arc length interval [0, L]. In the region near the clamped end, the displacements obtained with the two meshes are nearly indistinguishable. In the middle region, the two curves still essentially overlap, and only very small deviations appear at a few sampling points. In the region near the free end where the deflection reaches its maximum, visible but still very small differences arise between the two meshes. In contrast to a comparison based only on the displacements at the endpoints, Figure 18 presents the full field displacement distribution along the entire arc length, which clearly shows that the influence of mesh refinement on the global response is very limited.

Figure 18.

Distribution of the vertical centerline displacement of the elliptical arc cable along the normalized arc length for different meshes (ne = 5 relative to the reference mesh ne = 10).

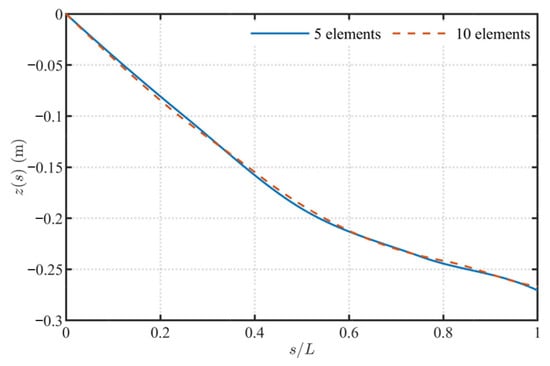

Figure 19 shows the distribution of the absolute centerline position z(s) along the arc length at the same time instant. From the figure, it can be observed that the two curves are likewise in very close agreement over the entire arc length, and the overall sagging profile and curvature variation of the beam almost coincide, with only slight differences of the order of 10−3 near the free end. The comparison between Figure 18 and Figure 19 indicates that the proposed element yields full field distributions of both the displacement field and the geometry that are in good agreement for different meshes. Not only do the endpoint responses remain stable, but the shape and curvature distributions along the entire arc length also converge rapidly with mesh refinement.

Figure 19.

Distribution of the centerline position of the elliptical arc cable along the normalized arc length for different meshes (ne = 5 relative to the reference mesh ne = 10).

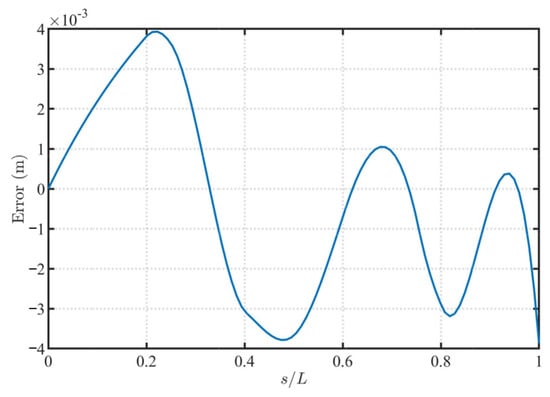

To quantitatively assess the effect of mesh refinement, the error of the mesh with 5 elements with respect to the reference solution is evaluated along the arc length, and the L2 and L∞ norms are used as measures. The error measures are defined by the following expressions:

where denotes the L2 norm of the deflection error of the 5 element mesh with respect to the 10 element reference mesh along the arc length, which characterizes the global average error level; is the L∞ norm of the maximum pointwise error along the arc length, which reflects the worst point error of the 5 element mesh relative to the reference solution.

Figure 20 shows the distribution of the discretization error along the arc length. It can be observed that the error curve is smooth and free of numerical oscillations, and its magnitude remains on the order of 4 × 10−3, which is much smaller than the maximum vertical displacement of the beam. Numerical integration shows that = 0.00173 and = 0.00393, and the corresponding relative errors are 1% and 1.3%, respectively. Hence, in the sense of the entire arc length, the average deflection error of the mesh with 5 elements is about 1%, and the maximum deflection error at any point is about 1.3%. In summary, the proposed element exhibits low sensitivity to mesh discretization in this example. Using only 5 elements already yields a full field response that is in very good agreement with the reference mesh. Since the spatial discretizations adopted in the subsequent examples are at least of the same order as the mesh used in this section, the numerical results reported in this work can be regarded as essentially mesh independent in space.

Figure 20.

Distribution of the centerline deflection error of the elliptical arc cable along the normalized arc length for different meshes (ne = 5 relative to the reference mesh ne = 10).

Figure 21 presents the analysis results of the ANCF finite element model. A comparison with the ANCF method further verifies the accuracy of the standard RANCF conic section element.

Figure 21.

Convergence assessment of ANCF finite elements.

To quantify the convergence behaviour, an absolute error tolerance of ε = 1.0 × 10−3 m is adopted for the discrete error of the tip position. This tolerance is much smaller than the characteristic displacement scale of the problem and therefore represents a relatively strict accuracy requirement. For this error tolerance, the proposed Kopt-element requires only 5 elements to satisfy the criterion, whereas the elements with K = 0.2 and K = 0.6 require 7 and 10 elements, respectively. Under the same tolerance, the standard ANCF element needs 9 elements. For comparison, under the same error tolerance, a conventional finite element model based on Euler–Bernoulli beam elements requires 13 elements. These results demonstrate that the Kopt-element achieves the prescribed accuracy with significantly fewer elements than both the non-optimal choices of K and the standard ANCF.

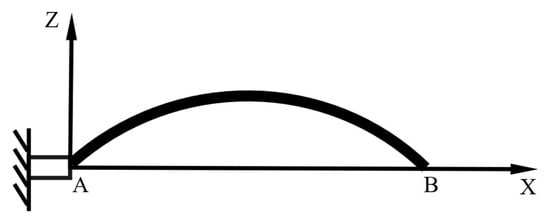

6.2. Spatial Pendulum with a Flexible Elliptical-Arc Cable

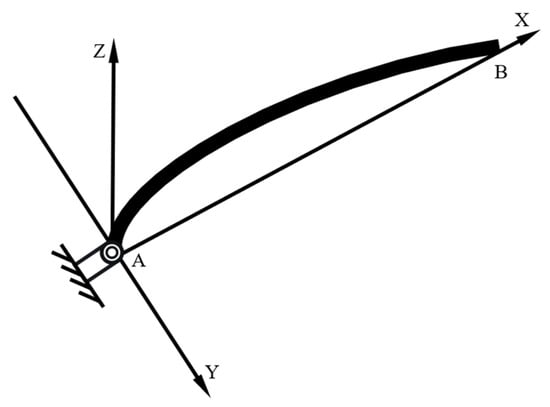

The second example in this study is the spatial pendulum with a flexible elliptical-arc cable shown in Figure 22. Its initial configuration lies in the X–Z plane, with , , m. After fixing the coordinates, the elliptical arc is specified to pass through the point (X, Y) = (0.264 m, 0.069 m). The cable has a circular cross-section with radius 0.02 m. Flexible material parameters are used: density 6000 kg/m3 and Young’s modulus 2 × 106 N/m2. The flexible elliptical-arc cable is released under gravity only, and the variation of the straight-line distance AB is monitored. The semicircular pendulum in Figure 19 is discretized using standard RANCF conic section elements. From Equation (27), is obtained for Figure 19; K = 0.1 is chosen for comparison.

Figure 22.

Schematic of the spatial pendulum with a flexible elliptical-arc cable.

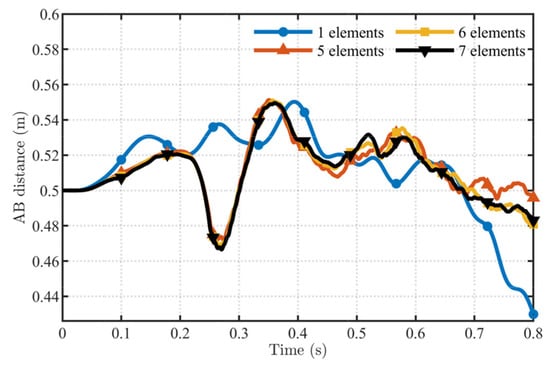

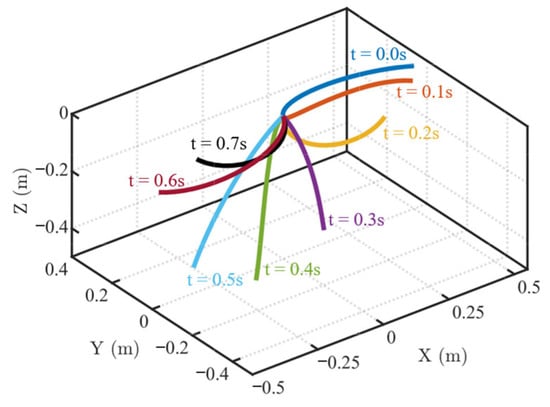

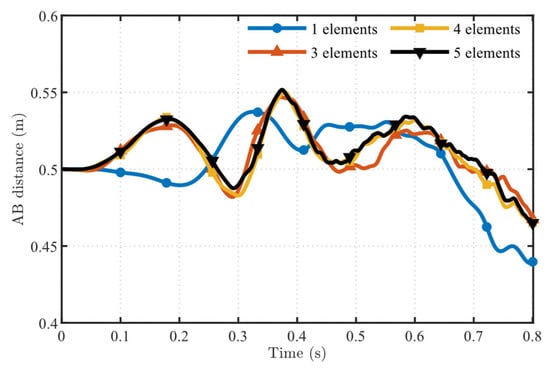

Figure 23 presents the cable configurations at different times when simulated with the optimally parameterized RANCF conic section element. Figure 24 shows the variation of the straight-line distance AB between the endpoints in Figure 22 as the cable deforms under gravity. Figure 24 reports the convergence results obtained using the optimally parameterized RANCF conic section element.

Figure 23.

Cable configurations at different times for Example 2.

Figure 24.

Convergence assessment plot for Kopt = 0.695.

Figure 25 shows the gradient curves of the RANCF conic section element for different values of K. From Figure 25, the element with K = 0.695 exhibits the smallest variation in the gradient curve among the three definitions, which correspondingly yields a more uniform distribution of parameter points.

Figure 25.

Gradient curves for Example 2.

Figure 26 presents the convergence results obtained with the RANCF conic section element at K = 0.1, compared against the optimal parameterization. It can be observed that, as the number of elements increases, the curves depicting the change of the straight-line distance AB between the endpoints become increasingly close, demonstrating the convergence of the RANCF conic section element. From the comparison of the two convergence plots, it is evident that, for three-dimensional large-deformation problems, the optimally parameterized RANCF conic section element attains higher accuracy with fewer elements than its non-optimal counterpart.

Figure 26.

Convergence assessment plot for K = 0.1.

6.3. Free and Forced Vibration Analysis of an Elliptical-Arc Cable

To further evaluate the applicability of the proposed element under complex dynamic conditions, this section considers the dynamic response under free vibration and end harmonic loading. This example involves pronounced geometric nonlinearity and represents a typical case in flexible multibody dynamics. The parameters are specified as θ0 = 30°, θ1 = 30°, and L = 0.5 m, and a point on the elliptical arc is given by the coordinates X = 0.25 m and Y = 0.067 m. The cable has a circular cross-section with radius 0.03 m, is clamped at point A, and has a density of 6000 kg/m3 and a Young’s modulus of 2 × 107 N/m2. The damping is modeled in the form of mass-proportional damping:

where cdamp denotes a dimensionless proportional coefficient used to control the damping magnitude.

The planar pendulum of the elliptical-arc cable shown in Figure 11 is discretized using the standard RANCF conic-section element, and the corresponding optimal value Kopt for Figure 27 is obtained as 0.5 from Equation (29).

Figure 27.

Schematic of the oscillator with a flexible elliptical arc cable.

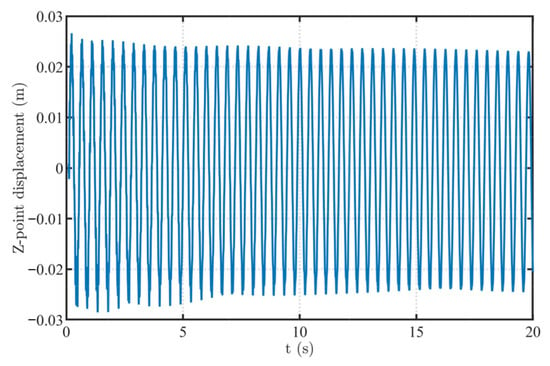

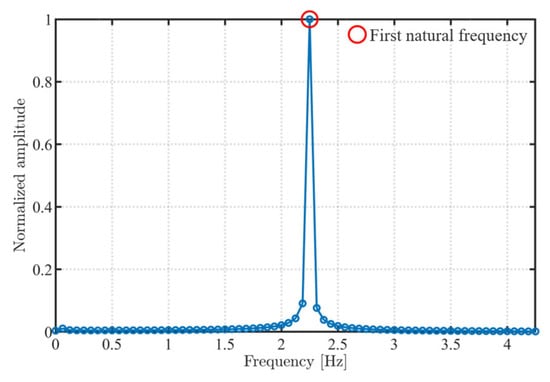

A free vibration analysis of the elliptical-arc beam is first performed without external load, with only a small initial velocity perturbation applied to the z-direction degree of freedom at the free end and all other degrees of freedom set to zero. To facilitate frequency identification, cdamp is set to 0. Figure 28 shows the time history of the z-direction displacement at the free end, where the response is approximately a single-frequency sinusoidal vibration with a slowly varying envelope.

Figure 28.

Time history of the z-direction displacement at the free end of the elliptical cable under free vibration (small initial perturbation, no external load).

After detrending the displacement time history at the free end and performing a fast Fourier transform (FFT), a clear dominant peak is obtained, as shown in Figure 29. The corresponding first numerical natural frequency is f1num = 2.2497 Hz. To assess the validity of this result, it is compared with a straight cantilever beam that has the same chord length and cross-sectional parameters. The first analytical circular frequency of the straight cantilever beam is f1num = 1.94 Hz. The first numerical frequency in this example differs from the analytical frequency of the straight beam with the same chord length by about 16 percent in relative terms. The elliptical cable exhibits an “arching effect”, and its tangent stiffness is higher than that of a straight beam with the same span in the sense of small-amplitude linearization, which increases the equivalent bending frequency. This level of deviation is acceptable for strongly geometrically nonlinear curved beam problems, which indicates that the proposed element can reasonably capture the first bending mode characteristics of the elliptical cable.

Figure 29.

Normalized frequency spectrum of the z-direction displacement at the free end of the elliptical cable under free vibration.

Based on the first numerical natural frequency of the elliptical cable, the near-resonant response under an end harmonic load is further investigated. The damping coefficient is set to cdamp = 0.5, which corresponds to a damping ratio of about 1.8 percent for the first mode. The concentrated harmonic load applied in the Z direction at the free end of the elliptical cable is given by:

In this expression, F0 denotes the amplitude of the harmonic excitation and is set to 0.1 N. ω denotes the circular frequency. f1num is taken as the excitation frequency and is chosen as the identified first numerical natural frequency, that is f = f1num.

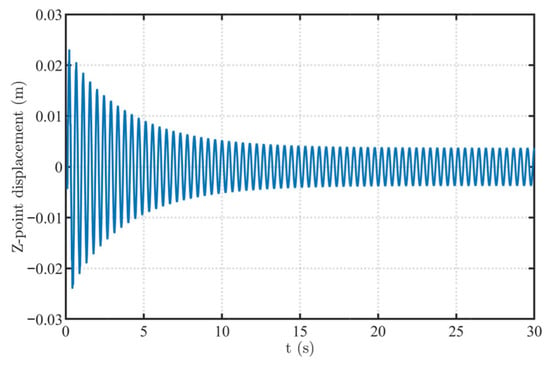

Figure 30 presents the time history of the displacement in the z direction at the free end under this harmonic load. It can be seen that there is a distinct transient phase in the initial stage of the response, which reflects the gradual decay of the free vibration component induced by the initial conditions due to damping. Subsequently, the system enters a steady response stage, where the amplitude remains nearly constant within about ±0.02 m and the vibration period is essentially equal to 1/f1num.

Figure 30.

Time history of the z-direction displacement at the free end of the elliptical cable under near-resonant harmonic excitation.

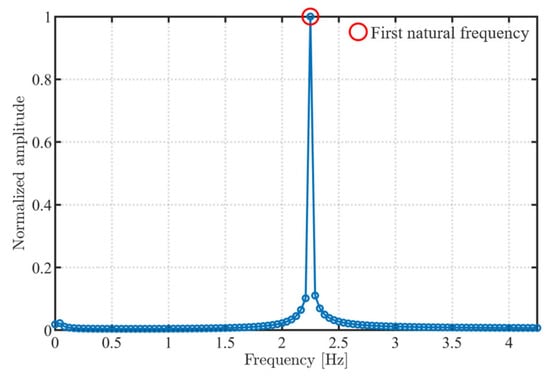

Applying FFT to the displacement time history in the steady stage yields an amplitude spectrum with a single pronounced dominant peak at 2.25 Hz, as shown in Figure 31. The location of this peak agrees very well with the first frequency obtained from free vibration and with the external excitation frequency, which indicates that the numerical model can accurately reproduce the dynamic response of the elliptical cable under near resonant harmonic loading.

Figure 31.

Normalized frequency spectrum of the z-direction displacement at the free end of the elliptical cable under near-resonant harmonic excitation.

In summary, the free vibration and resonant forced vibration examples of the elliptical-arc cable in this section show that the proposed element can reasonably predict the first natural frequency of flexible beam structures with initial curvature. In addition, the element provides stable and physically reasonable time-domain responses and frequency-domain characteristics under near resonant excitation, which further confirms its applicability in flexible multibody dynamic analysis.

7. Conclusions

This study proposes a direct definition method for RANCF elements for quadratic curves, together with the associated parameterization and optimal evaluation criteria. The method directly defines RANCF elements through the analytical properties of conic sections and systematically resolves the dependence of RANCF element construction on the linear transformation of NURBS. This approach effectively enhances both the applicability and efficiency of the direct definition method for RANCF elements.

First, the geometric constraints of conic sections are analyzed, and the unique rational parametric representation and degree-elevation formulas are derived. Subsequently, standardized RANCF conic section elements are established, and explicit formulations for nodal coordinates and weights are obtained based on the geometric characteristics of conics. Furthermore, the concept of the mapping factor K is introduced to characterize the mapping between parameter space and physical space, and parameterization of standardized RANCF conic section elements is achieved through K. Finally, by analyzing the influence of K on weights, shape functions, and gradients of standardized RANCF conic section elements, it is found that the functions formed by K with weights and shape functions exhibit non-monotonicity, while the relation between K and gradient ratios shows a unimodal property. Based on this, the concept of the optimal mapping factor Kopt is proposed to select the best standardized RANCF conic section elements, referred to as the Kopt-element. This scheme effectively suppresses the arbitrariness in element definition and significantly improves computational efficiency.

To evaluate the performance of the Kopt-element, numerical simulations are carried out using standardized RANCF conic-section elements defined with different values of K. The results show that the Kopt-element requires fewer elements to achieve a prescribed accuracy threshold, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed method. Furthermore, to verify the accuracy of the element and demonstrate its potential in flexible multibody dynamics, comparisons with ANCF results under the same conditions reveal high consistency within the prescribed accuracy threshold. As representative applications, the three-dimensional elliptical pendulum illustrates the applicability of the element under large deformations, while the free and resonant forced vibrations of an elliptical-arc cable show that the proposed element can reasonably predict the first natural frequency of initially curved flexible beam-like structures. In addition, under near-resonant excitation, the element provides stable and physically meaningful time- and frequency-domain responses, further confirming its suitability for flexible multibody dynamic analyses.

The outcomes of this study hold both theoretical and practical significance. From a theoretical perspective, the mapping factor K helps to reveal the relationship between the parameter space and the physical space in rational absolute nodal coordinate elements and clarifies the source of non-uniqueness in element definitions. From a practical perspective, it enables fast and accurate modeling and large-deformation dynamic analysis of flexible multibody systems with complex curve geometries in engineering fields such as flexible robotics, vehicle dynamics, and aerospace structures. From an engineering point of view, we recommend using the optimized mapping factor Kopt in practical applications and avoiding very small or very large values of K, as they tend to deteriorate the quality of the mapping and the conditioning of the element matrices. In addition, these results provide a solid theoretical foundation and practical guidelines for the broad dissemination and application of the RANCF methodology in engineering practice. It should be noted that the present formulation is currently limited to one-dimensional RANCF conic elements, and the extension to shell or solid elements on conic surfaces, as well as a more systematic study of the conditioning and dynamic effects associated with extreme values of the mapping factor K, will be addressed in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, M.S.; validation, Y.L., M.S.; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; visualization, M.L.; supervision, P.L.; project administration, P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Henan Provincial R & D Plan Joint Fund (No. 225101610072); the Independent Research Project of State Key Laboratory of Green Building in west China (No. LSZZ202209).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and helpful suggestions, which have greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Shabana, A.A. An absolute nodal coordinates formulation for the large rotation and deformation analysis of flexible bodies. In Technical Report MBS96-1-UIC; University of Illinois at Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shabana, A.A.; Hussien, H.A.; Escalona, J.L. Application of the absolute nodal coordinate formulation to large rotation and large deformation problems. J. Mech. Des. 1998, 120, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htun, T.Z.; Suzuki, H.; García-Vallejo, D. Dynamic modeling of a radially multilayered tether cable for a remotely-operated underwater vehicle (ROV) based on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation (ANCF). Mech. Mach. Theory 2020, 153, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Wang, Z.M. Vibration analysis of radial tire using the 3D rotating hyperelastic composite REF based on ANCF. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 126, 206–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzeri, M.; Shabana, A.A. Development of simple models for the elastic forces in the absolute nodal coordinate formulation. J. Sound Vib. 2000, 235, 539–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.L.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H.Y. Advances in dynamic modeling and optimization of flexible multibody systems. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2019, 51, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, A.M.; Shabana, A.A. A non-incremental finite element procedure for the analysis of large deformation of plates and shells in mechanical system applications. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2003, 9, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A.; Eldeeb, A.E. Motion and shape control of soft robots and materials. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 104, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Zhong, H.Z. Spatial weak form quadrature beam elements based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 181, 105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.T.; Tang, L.L.; Liu, J.Y. Dynamic modeling and analysis for inflatable mechanisms considering adhesion and rolling frictional contact. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 184, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.J.; Gong, Y.Z. An enhanced absolute nodal coordinate formulation for efficient modeling and analysis of long torsion-free cable structures. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 123, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Sugiyama, H. Numerical convergence of finite element solutions of nonrational B-spline element and absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 67, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, A.; Shabana, A.A.; Sanchez-Rebollo, C. Comparison between ANCF and B-spline surfaces. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2013, 30, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, A.A. Use of B-spline surface to model large-deformation continuum plates: Procedure and applications. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 72, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Integration of computer-aided design and analysis: Application to multibody vehicle systems. Int. J. Veh. Perform. 2019, 3, 300–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. An overview of the ANCF approach, justifications for its use, implementation issues, and future research directions. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2023, 58, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Shabana, A.A. Rational finite elements and flexible body dynamics. J. Vib. Acoust. 2010, 132, 041007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanborn, G.G.; Shabana, A.A. A rational finite element method based on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2009, 58, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanborn, G.G.; Shabana, A.A. On the integration of computer aided design and analysis using the finite element absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2009, 22, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.S.; Liu, M.L. Construction method for circular arc elements in rational absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 203, 105811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Continuum-based geometry/analysis approach for flexible and soft robotic systems. Soft Robot. 2018, 5, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liao, W.H. Dynamic modeling of a fish tail actuated by IPMC actuator based on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.G.; Tinsley, B.; Shabana, A.A. Integration of geometry and analysis for vehicle system applications: Continuum-based leaf spring and tire assembly. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 11, 031011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, W.H. Dynamics analysis of planar rigid-flexible coupling deployable solar array system with multiple revolute clearance joints. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 117, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Chung, J. Dynamic analysis of a tethered satellite system for space debris capture. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 94, 2391–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guo, J.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. Dynamic modeling of three-dimensional muscle wrapping based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 13073–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H. Dynamic modeling, simulation and design of smart membrane systems driven by soft actuators of multilayer dielectric elastomers. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 102, 1463–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lan, P.; Lu, N. A piecewise beam element based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 77, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, P.; Yu, Z.Q.; Du, L.; Lu, N.L. Integration of non-uniform rational B-splines geometry and rational absolute nodal coordinates formulation finite element analysis. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2014, 27, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, D. A novel Bézier planar beam modeling method based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 141, 115922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.Q.; Shabana, A.A. Mixed-coordinate ANCF rectangular plate finite element. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2015, 10, 061003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, C.M.; Yu, Z.Q.; Zhang, X.S.; Shabana, A.A. Rational ANCF thin plate finite element. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2016, 11, 031003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wei, C.; Sun, J.; Liu, B. Modeling method and application of rational finite element based on absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2018, 31, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wei, C.; Ma, C.; Zhao, Y. Modeling and verification of a RANCF fluid element based on cubic rational Bézier volume. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 15, 041005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.S.; Ouyang, B. A variable-length rational finite element based on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation. Machines 2022, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstmayr, J.; Sugiyama, H.; Mikkola, A. Review on the absolute nodal coordinate formulation for large deformation analysis of multibody systems. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 8, 031016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Liu, C.; Tian, Q.; Hu, H.Y. Three new triangular shell elements of ANCF represented by Bézier triangles. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2015, 35, 321–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Makihara, K.; Sugiyama, H. Recent advances in the absolute nodal coordinate formulation: Literature review from 2012 to 2020. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 17, 080803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Definition of ANCF finite elements. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dynam. 2015, 10, 054506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, R.; Wei, C.; Zhao, Y. A new absolute nodal coordinate formulation of solid element with continuity condition and viscosity model. Int. J. Simul. Syst. Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 10.1–10.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A.; Hamed, A.M.; Mohamed, A.N.A. Use of B-spline in the finite element analysis: Comparison with ANCF geometry. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2012, 7, 011008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lan, P. Subdivision method for rational ANCF circular elements. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.J.R.; Cottrell, J.A. Isogeometric analysis: CAD, finite elements, NURBS, exact geometry and mesh refinement. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 4135–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, A.; Gantner, G.; Giannelli, C.; Praetorius, D. Mathematical foundations of adaptive isogeometric analysis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4479–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, M.; Santi, G.M.; Sevilla, R.; Liverani, A.; Petrinic, N. NURBS-enhanced finite element method (NEFEM) on quadrilateral meshes. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2024, 231, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Pichardo, M.; López-Barrientos, J.D.; Perea-Flores, S. Scrutinizing the General Conic Equation. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).