Abstract

The factors restricting the large-scale deployment of smart vehicular networks include application service placement/migration, mobility management, network congestion, and latency. Current vehicular networks are striving to optimize network performance through decentralized framework deployments. Specifically, the urban-level execution of current network deployments often fails to achieve the quality of service required by smart cities. To address these issues, we have proposed a vehicular edge–fog computing (VEFC)-enabled adaptive area-based traffic management (AABTM) architecture. Our design divides the urban area into multiple microzones for distributed control. These microzones are equipped with roadside units for real-time collection of vehicular information. We also propose (1) a vehicle mobility management (VMM) scheme to facilitate seamless service migration during vehicular movement; (2) a dynamic vehicular clustering (DVC) approach for the dynamic clustering of distributed network nodes to enhance service delivery; and (3) a dynamic microservice assignment (DMA) algorithm to ensure efficient resource-aware microservice placement/migration. We have evaluated the proposed schemes on different scales. The proposed schemes provide a significant improvement in vital network parameters. AABTM achieves reductions of 86.4% in latency, 53.3% in network consumption, 6.2% in energy usage, and 48.3% in execution cost, while DMA-clustering reduces network consumption by 59.2%, energy usage by 5%, and execution cost by 38.4% compared to traditional cloud-based urban traffic management frameworks. This research highlights the potential of utilizing distributed frameworks for real-time traffic management in next-generation smart vehicular networks.

Keywords:

internet of vehicles; vehicular communication; dynamic clustering; load balancing; fog computing MSC:

68M14; 68M20

1. Introduction

With the rapid pace of urbanization and the continuous growth in vehicle ownership, traffic congestion and road accidents have become critical challenges in the development of smart cities [1,2]. These issues limit the smooth flow of traffic and lead to significant consequences, including longer travel times, increased driver stress, higher fuel consumption, and elevated emissions. Moreover, the inefficient traffic framework poses serious threats during emergencies, where delays can have life-threatening impacts [3]. For these reasons, the deployment of intelligent transportation systems (ITS) is an essential requirement to ensure safe, flexible, and sustainable urban mobility [4].

In earlier studies, several cloud-based ITS frameworks were proposed to address traffic management [5]. However, centralized cloud architectures face inherent challenges: (1) high latency, as large volumes of real-time traffic data must be transmitted over wide-area networks; (2) limited support for mobility, since vehicles are highly dynamic, and traditional clouds struggle to serve moving terminals efficiently; and (3) low scalability, as heterogeneous vehicular infrastructures such as vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs), mobile nodes, and road side units (RSUs) are difficult to manage in a purely centralized system [6,7].

To overcome these challenges, researchers have introduced decentralized frameworks based on fog and edge computing paradigms [8]. A fog-enabled architecture shifts computing and storage functions from the centralized cloud to the network edge [9]. Although fog computing has less capacity than cloud computing, it significantly reduces the latency by processing data closer to vehicles [10]. The internet of vehicles (IoV) enables real-time communication between vehicles and roadside infrastructure through vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) links. The RSUs act as communication hubs, providing traffic information, supporting vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication, and connecting vehicles with fog and cloud resources [11]. In vehicular edge–fog computing (VEFC) networks, vehicles equipped with on-board units (OBUs) function as mobile edge devices, while fog servers deployed as RSUs are responsible for collecting, processing, and storing real-time traffic information [12]. This distributed architecture improves the interaction efficiency via V2V and vehicle-to-RSU (V2R) communication, thereby enhancing the responsiveness and effectiveness of ITS [13].

There exist two categories of congestion control: (1) predictive and (2) reactive. Predictive schemes use historical or real-time traffic data to forecast congestion. The reactive ones respond after congestion occurs. Qi et al. [14] proposed an accident message attenuation model to reduce congestion caused by accidents and later designed a two-level intersection control strategy using additional warning lights [15]. The reactive solutions are effective for handling traffic issues at a local scale, but they are not valuable for implementing across the entire urban network.

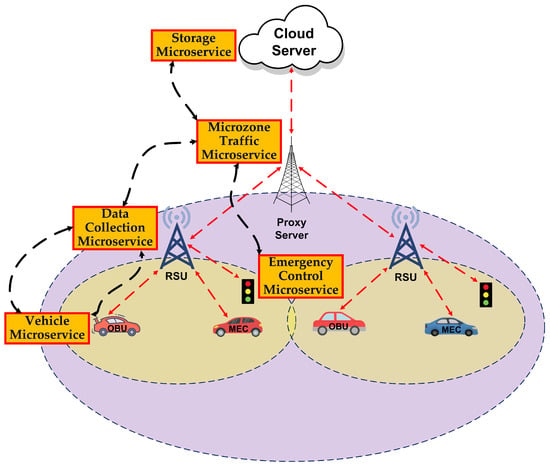

Despite notable progress in ITS, existing frameworks largely rely on centralized processing, which limits the scalability and responsiveness in dynamic vehicular environments. In addition, the existing distributed frameworks face several challenges, including limited scalability, unstable service migration, a lack of coordinated area-based control, and weak microservice orchestration across heterogeneous nodes. These limitations restrict real-time implementation across large-scale deployments, motivating the design of an adaptive area-based approach. Therefore, for the efficient implementation of vehicular management, we proposed a grid-based management approach that divides the urban area into manageable regions. These regions are coordinated through a four-tier architecture, enabling localized reactive control while ensuring overall system integration, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Adaptive area-based traffic management framework.

In this paper, we propose an adaptive area-based traffic management architecture that ensures efficient vehicular management. Key contributions are summarized as follows:

- In Section 3.1, we present a decentralized vehicle management framework that segments an urban region into multiple operational areas, each managed by the respective proxy servers via RSUs.

- In Section 3.2, we employed a microservice-based application approach for implementing the proposed distributed framework. The proposed application design enables dynamic placement and scaling [16] of application modules across multiple network nodes. Moreover, this approach enables the integration of various modular strategies in the system.

- In Section 4.2, a mobility management algorithm is presented for the provision of the efficient migration of services while considering the position and speed of the vehicle, along with the availability of RSUs. Correspondingly, the selection of intermediate nodes to facilitate service migration in the absence of RSUs is also considered.

- In Section 4.3, a dynamic vehicular clustering algorithm is presented that groups the RSUs based on proximity, communication range, and latency, to ensure efficient, low-latency, and reliable V2I communication.

- In Section 4.4, a dynamic microservice assignment algorithm is presented that effectively places microservices according to the location and resource availability.

- In Section 6, we evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed schemes on multiple scales on the EUA dataset. Our evaluation demonstrates enhanced performance with significant improvements in latency, network consumption, execution cost, and energy efficiency, as compared to existing schemes.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the literature related to advanced traffic management schemes. Section 3 proposes a novel adaptive area-based vehicular management framework. Section 4 presents the schemes designed for the effective management of the vehicular network. Section 5 defines the simulation setup organized for evaluation of the proposed schemes. Section 6 presents the results of the multiscale evaluations performed using the proposed approaches. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

Several recent studies have proposed decentralized frameworks incorporating fog/edge computing architectures for the effective implementation of vehicular networks. The centralized platforms often hinder the real-time processing of vehicular information due to their cloud-centric resource provision. The authors of [17] implemented a fog-enabled decentralized framework that provides resources in a decentralized manner. The framework provides a significant reduction in delay, as compared to cloud-based platforms. They deployed a cloud platform for storing traffic information. The deployed platform is favorable in providing low-latency smart traffic solutions. Its large-scale deployment faces challenges like scalability, resource management, and privacy [18], due to the dependence on resource-constrained fog nodes.

In [19], a fog computing-based multi-agent management approach is adopted for implementing a traffic management system. The system effectively provides traffic light adjustment through Q-learning-based processing of real-time information. It also provides dynamic adaptations that respond to varying traffic volumes, offering significant improvements compared to traditional traffic control systems. Additionally, the study proposes a security protocol to maintain data integrity during vehicle-to-traffic light communication, thereby addressing flaws in conventional systems. However, although the proposed system represents progress in smart city traffic management, its design lacks area-based control, which makes its large-scale implementation face control challenges.

In recent research, edge computing has made a major contribution to the field of intelligent traffic management systems (ITMS) and especially in predicting traffic congestion. In [20], a congestion prediction system is proposed that combines the use of fuzzy logic with hybrid approaches to predict and control congestion in real time. The solution takes advantage of edge computing to perform local processing, therefore, decreasing the latency and providing faster decision-making processes. However, the large-scale implementation is restricted, due to the high traffic data that has to pass through several hops before accessing the cloud architecture. The reliance on expert guidance for configuring the fuzzy logic system also creates constraints in terms of flexibility and the ease of large-scale implementation. In spite of these limitations, the suggested scheme outperforms traditional centralized schemes in terms of delay and accuracy.

The authors in [21] proposed a novel fog-enabled traffic light management strategy (TLMS), which reduces vehicle waiting times at intersections and improves traffic flow. Through fog resources, this strategy facilitates the real-time processing of information collected through the V2I links. The system achieves a 45% reduction in delay. The dependency on cloud and fog nodes limits the large-scale implementation of the framework, and the lack of microservice management limits the scalable implementation. This work is a significant contribution towards the efficient deployment of traffic management, illustrating the effectiveness of a distributed architecture for real-time vehicle management.

The recent studies have shown the importance of adaptive microservice management schemes for the implementation of efficient VANETs. Conventional clustering algorithms are unable to tackle issues related to the dynamic nature of vehicular networks. For advanced vehicular networks, a robust software-defined vehicular fog computing (SDFC) framework is presented in [13] that effectively manages the network through adaptive cluster formation and resource utilization. The proposed framework also incorporates a load-balancing scheme to manage traffic-based load assignment. The scheme has limitations related to large-scale implementation, controller placement, and disruptions from mobile network handovers.

A multi-layered traffic scheme for a situation-aware vehicular management framework is presented in [22] that enables real-time information processing through the utilization of fog/cloud resources. The system predicts traffic-related situations through logistic regression and artificial neural networks. The proposed framework enhances adaptive traffic signal control and optimizes vehicle routing. The high cost hinders the large-scale implementation of this framework. A hybrid fog/edge-enabled approach for task-aware processing is presented in [23]. This approach provides reduced latency and improved network utilization through dynamic clustering and load balancing.

A fog-enabled smart navigation system of emergency vehicles (SNSEV) for real-time data analysis and processing is presented in [24]. SNSEV enhances the response time by dynamically adjusting traffic lights and giving emergency vehicles priority routes, causing a significant improvement in the safety and welfare of people in cities. The approach also has various benefits, such as making decisions in real time, managing dynamic traffic flow, and prioritization. The recent smart traffic management frameworks are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of recent intelligent traffic management frameworks.

Most of the existing work on ITS is focused on localized vehicle management [25], congestion control [26], and real-time monitoring [27]. These schemes achieved reduced latency and improved throughput, but they lack adaptive area-based management. Most of the frameworks designed so far are monolithic in nature, restricting their large-scale deployment. The mobile nature of vehicular networks requires a seamless migration of tasks and heterogeneous infrastructures for effective resource management. Effective balancing of loads among multiple network nodes requires the dynamic clustering of devices for efficient vehicular network deployment. In addition, recent proposed frameworks lack integration of real-world datasets in their evaluations, restricting their applicability in dynamic urban environments. To address these issues, we have proposed an adaptive area-based segmentation of the urban traffic network for better information processing. In addition, we have proposed multiple schemes to effectively manage mobility, clustering, and service migration to efficiently manage vehicular traffic. Our proposed schemes are evaluated on multiple scales with different vehicular loads to ensure reliable and scalable deployments. Table 2 presents the limitations of the previous studies, summarizes their key features, and describes the novelty of the proposed architecture.

Table 2.

Comparison with existing surveys in autonomous driving and vehicular AI systems.

Existing studies provide valuable insights into fog/edge-enabled traffic management; however, they generally lack area-based control, do not support seamless microservice migration, and provide limited scalability due to static clustering or centralized decision-making. Moreover, most frameworks rely on simulated or synthetic datasets, limiting their real-world applicability. These gaps motivate our adaptive area-based architecture, which integrates mobility-aware service migration, dynamic clustering, and distributed microservice orchestration to overcome these limitations.

3. System Architecture

The urban traffic management approach has to deal with city-wide vehicular traffic control. To achieve efficient management, the large urban area is partitioned into multiple areas, each controlled by a dedicated control unit. The proposed VEFC-enabled area-based traffic management scheme is explained in this section.

3.1. Adaptive Area-Based Traffic Management Framework

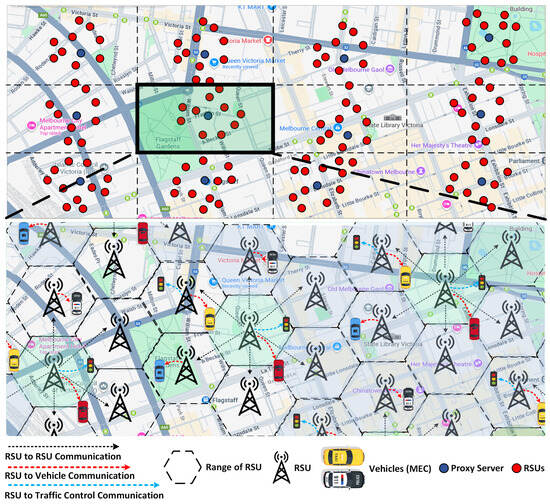

In this section, we present an area-based traffic management framework that leverages the VEFC paradigm within the Internet of Vehicles. The proposed framework divides the urban region into multiple microzones and assigns a proxy server to each microzone. Multiple fog nodes assigned to each microzone act as RSUs, processing real-time roadside information collected from vehicles and infrastructure. The cloud server resides at the uppermost tier of the hierarchy, providing centralized coordination and control. The smart vehicles moving across these regions are mobile edge nodes with OBUs enabling V2V and V2I communication. Figure 2 illustrates microzones with RSUs denoted in red, proxy servers in blue, and vehicular movement in the Melbourne Central Business District. For each vehicle in the scenario, different datasets are generated for each vehicle to generate mobility positions in their desired microzone. The proposed approach is based on four layers as described below:

Figure 2.

Microzone-wise distribution of the urban area and movement of vehicles in Melbourne Central Business District.

- Cloud Layer: This is the uppermost layer of the proposed architecture, containing the cloud server, the most resourceful entity of the architecture. The cloud server is responsible for the processing of the tasks requiring resources not available at the lower layers. The cloud server stores historical traffic information for predictive analysis to forecast congestion. All the microzones are connected to this layer for the overall management of the urban area.

- Proxy layer: This layer consists of multiple proxy servers, with each proxy server acting as a supervisory head to each microzone. The purpose of the proxy server is to manage traffic within its designated microzone. For effective vehicular management and the seamless exchange of traffic information, all proxy servers are interconnected with each other. Moreover, all proxy servers are connected to the centralized cloud server for the execution of tasks requiring extra resources.

- RSU Layer: This layer comprises fog nodes acting as RSUs in the proposed framework. These RSUs are responsible for the collection and processing of vehicular information. For real-time traffic management, multiple RSUs are assigned to each microzone. All the RSUs are associated with the proxy server of the microzone. Similarly, they are also interconnected and are utilized for the calculation of the shortest path between multiple network components.

- Traffic Layer: This layer consists of all the traffic monitoring equipment and vehicles. The vehicles in the network are equipped with OBUs and act as a mobile edge computing (MEC) node. The nodes present in this layer are utilized for the transmission and reception of real-time vehicular information for efficient traffic management. Additionally, it executes the commands received from fog and proxy servers to manage the traffic flow.

In each microzone, there exist multiple RSUs for the collection of vehicular information. These RSUs communicate with vehicles and traffic control units for real-time traffic control. Each microzone is assigned to a proxy server. The proxy server is responsible for cooperating with the RSUs residing in the microzone for the collection and processing of vehicular information. All proxy servers are interconnected to share information for efficient traffic management. The cloud server at the top of the hierarchical structure is responsible for the collection of information from proxy servers. The cloud resources are utilized for global traffic analysis and decision support. This hierarchical design enhances microscopic models at the RSU level with macroscopic integration through proxy and cloud coordination, thereby improving scalability, reducing latency, and enabling adaptive traffic control across the entire urban network.

The RSUs within each management area collect detailed vehicular information from OBUs on individual roads and lanes. In the proposed framework, we divide the urban area into several microzones. We completely utilize the benefits of distributed computing. We have adopted a modular application approach, consisting of several microservices. The details of the application model are described in the next section.

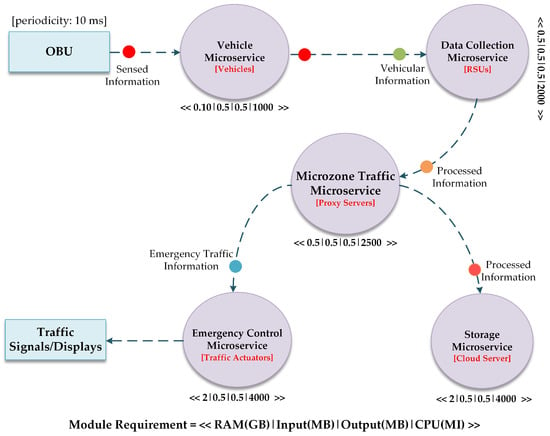

3.2. Application Model

The directed acyclic graph (DAG) of the deployed application is shown in Figure 3. The DAG contains multiple vertices that represent microservices, and edges denote the data dependencies between these modules. The proposed framework consists of five key microservices that are specified below:

Figure 3.

Directed acyclic graph of the deployed intelligent traffic management application.

- Storage Microservice: This module is responsible for storing the information requiring long-term usage. In smart traffic control environments, the critical traffic information, e.g., historical traffic data, accidents, etc., is needed for predictive traffic schemes and forensic analysis.

- Microzone Traffic Microservice: This microservice is initially placed at proxy servers to process the traffic information of the assigned area. This module requires more processing resources, as it applies advanced artificial intelligence techniques on the acquired information for real-time traffic management. Moreover, the proxy servers not only have to process the allocated microzone information but also have to coordinate with other areas for efficient traffic management. This microservice is also responsible for the transmission of signals to the Emergency Control Module as per requirements.

- Data Collection Microservice: This module is initially assigned to the fog nodes working as RSUs. This microservice preprocesses the real-time traffic information gathered from the smart vehicles. These modules preprocess that information and forward the outcomes to the Microzone Traffic Microservice and Vehicle Microservice.

- Vehicle Microservice: This microservice is placed on the smart vehicles as an OBU to collect and exchange real-time vehicular and traffic information with nearby vehicles (i.e., V2V) and roadside infrastructure (i.e., V2I). This module interacts with the Data Collection Microservice at the RSUs to ensure the real-time exchange of safety messages, congestion information, and emergency alerts.

- Emergency Control Microservice: This microservice is placed on different actuators to display information about traffic incidents or accidents, identifying traffic disruptions such as accidents or road closures.

All microservices are responsible for the complete execution of the deployed application. They coordinate with each other to provide effective vehicular management. These latency-sensitive modules are to be deployed on distributed nodes to avoid delayed responses. Only the storage module, requiring high resources, is to be placed on the cloud server.

4. Methodology

This work adopts a multi-tier VEFC architecture (Section 3) and a modular application model to support mobility-aware latency-sensitive traffic management. Our methodology first defines the system entities and the mathematical model, after which three schemes are executed across different network nodes. Together, these schemes operate as a unified workflow that maintains low-latency operation under dynamic vehicular conditions. The evaluation logic follows two scenarios using the EUA dataset and the iFogSim2 platform, enabling the multi-scale validation of scalability, resource use, and microservice orchestration efficiency.

4.1. Mathematical Model

This section defines the mathematical model for the architecture, on which we have executed the proposed algorithms for the efficient deployment of the vehicular network. Our model contains a set of smart vehicles, RSUs, proxy servers, and a cloud server, as described in the previous section. Equation (1) defines the position of a vehicle at time t, and the instantaneous speed of the vehicle is defined by Equation (2).

The RSUs are at a fixed location in the architecture. Each RSU f has a fixed position . The Euclidean distance between vehicle i and RSU f is defined by Equation (3), which is implicitly used in different functions of the proposed algorithms.

The internal functions used in the pseudo-code are modeled as follows:

- returns the coverage radius of an RSU f, denoted as .

- returns the communication range of RSU f, denoted as .

- returns the current load (e.g., number of active services/sessions).

- returns the maximum admissible load .

- returns the latency between vehicle i and RSU .

- returns the remaining resource vectors = .

4.1.1. Mobility Management Conditions

The proposed mobility management algorithm decides whether to keep a service at the current RSU , migrate it to the nearest RSU , or migrate it to a proxy, based on the coverage and load constraints, as defined by Equations (4) and (5).

In Algorithm 1, the conditions at Steps 10–15 implement the following logic: if the nearest RSU satisfies (4) and (5), the call is triggered; otherwise, if (5) is violated for the nearest RSU, the service is migrated to a proxy server (), having more resources for service execution. These rules minimize the service disruption by keeping the vehicle inside coverage while avoiding overloaded RSUs.

| Algorithm 1 Vehicle mobility management |

|

4.1.2. Clustering Conditions

The proposed clustering algorithm groups RSUs into dynamic clusters around a vehicle to ensure feasible and low-latency V2I connectivity. For vehicle i, the internal variables in Algorithm 2 correspond to

- ← =

- ← the maximum admissible communication distance

- ← the latency threshold.

RSU becomes a cluster member of vehicle i if it is within communication range and satisfies a latency bound, as given in Equation (6).

The internal function in Steps 12–16 of Algorithm 2 evaluates the first inequality in (6), while computes . The pruning step (Steps 20–28) removes RSUs that violate ≤ . Hence, DVC realizes a latency- and range-constrained clustering around the vehicle.

| Algorithm 2 Dynamic vehicular clustering (DVC) algorithm |

|

4.1.3. Microservice Placement Constraints

Equation (7) defines the demand vector of each microservice m in the microservice placement algorithm. F is a set of hierarchical network nodes (fog, proxy, cloud) extracted from the application DAG. The ordered list of application microservices that must be placed (Vehicle, Data Collection, Microzone Traffic, Emergency Control, Storage) is defined by a.

Each candidate node f (RSU, proxy, or cloud) exposes an available vector . The internal function is satisfied if and only if the resource-feasibility inequalities defined in Equation (8) are satisfied.

Step 11–17 and 24–28 of Algorithm 3 use (8) to decide whether to place a module or to search the cluster members for an eligible node. When a microservice cannot be placed along the direct leaf-to-root path P, DMA explores nearby cluster members and then higher-tier nodes, always respecting (8). This realizes a distributed resource-constrained placement and migration policy.

| Algorithm 3 Dynamic microservice assignment (DMA) algorithm |

|

4.1.4. Latency and Cost-Oriented Objective

The overall design objective of the three algorithms is to reduce the end-to-end latency and network usage while keeping the execution cost moderate. Let S denote the set of active service control loops (Vehicle → Data Collection → Microzone Traffic → Emergency Control/Storage). For a given deployment (i.e., chosen RSUs, proxy, and cloud nodes for all microservices), we denote

- : end-to-end delay of loop sS;

- : network usage for loops s;

- : execution cost for loop s.

Equation (9) defines the simplified multi-objective cost function with weighing factors , , ≥ 0. The VMM, DVC, and DMA algorithms act as distributed heuristics that enforce constraints (4)–(8) while implicitly driving the system towards low values of the composite objective (9). The improvement reported in the latency, network consumption, energy usage, and execution cost compared to the centralized and edgeward baselines is therefore consistent with this formal objective.

4.2. Vehicle Mobility Management Algorithm

Vehicle movement is an important factor to be considered while designing modern vehicular management systems. Their frequent position change impacts the RSU selection procedure. The vehicle mobility management (VMM) algorithm presented in this research provides an efficient service migration, depicted in Algorithm 1. The available RSUs, along with the position and speed of the vehicles, are crucial parameters considered by the VMM scheme for smooth mobility management. The designed approach is also responsible for the smooth service migration and intermediate node selection in the absence of RSU availability. The VMM approach optimizes the network performance through effective connectivity management between the infrastructure and vehicles.

The VMM uses several variables, namely, represents the vehicle’s current location containing Cartesian coordinates (x, y); represents the current speed of vehicles; represents the nearest RSU available to the vehicles; represents the vehicles currently connected RSU; is the coverage area of RSU in meters; specifies the RSU’s communication radius; describes the present load on the assigned RSU; and ensures that RSU does not exceed its capacity. The VMM monitors vehicular movement to determine whether the service migration is required. Service migration occurs whenever the nearest RSU differs from the currently assigned RSU, even if the current RSU is not fully loaded. This ensures that the vehicle always connects to the most geographically suitable RSU, maintaining optimal V2I communication and reducing handover delay. Migration to the proxy server is only triggered when the current RSU is overloaded. The algorithm inspects vehicles, controls the connectivity of RSUs, and redirects services to the proxy server in case of RSU congestion, limiting the effect on the network and energy.

4.3. Dynamic Vehicular Clustering Algorithm

For optimum network management, improved communication between network components plays an important role. In the proposed vehicular framework, the RSUs are resource-constrained devices, and their clustering presents an effective way to optimize architectural efficiency. The proposed dynamic vehicular clustering (DVC) algorithm is presented below, which groups the RSUs on the basis of their location, range, and offered latency. This clustering ensures efficient and reliable V2I communication in vehicular networks.

The algorithm is initialized by collecting information related to vehicle location, assigned RSU, neighboring RSUs, communication range of vehicle, and latency threshold (Steps 2–6). The algorithm utilizes this information for accurate clustering and location prediction. In steps 7–10, the algorithm calculates the distance between vehicles and the neighboring RSUs by using the vehicle’s Cartesian coordinates. After that, identification of appropriate RSUs that fall within the range of the vehicle and addition of these RSUs to the list of cluster members (CMs) are performed in steps 11 to 17. Moreover, the algorithm also manages CMs through the active removal of RSUs offering latency more than the threshold. Finally, the list of CMs is finalized along with their corresponding latencies to ensure an efficient RSU selection process for communication purposes. The algorithms guarantee optimum network performance through real-time V2I connectivity. In cases where RSUs are overburdened, the traffic load is transferred to proxy servers to ensure seamless and efficient vehicular management.

4.4. Dynamic Microservice Assignment Algorithm

Microservices are independent modules placed on network devices for performing specific tasks. The proposed distributed application design allows the migration of modules between various nodes. The dynamic microservice assignment (DMA) scheme utilizes the service discovery function of iFogSim2 [28] for the discovery and placement of required modules on different distributed network nodes. The MicroservicesController class manages the load balancing and microservice placement. The DMA scheme ensures the effective placement of microservices. The proposed scheme takes into account the resource availability and location of nodes during module assignment. It allocates services to nodes that have enough resources or to cluster members that are close to each other to facilitate efficient placement. Service discovery information is also updated by the algorithm, and this guarantees smooth orchestration. The DMA algorithm is given below.

To evaluate the performance of our proposed schemes, we conducted experiments using the iFogSim2 simulator, that provides built-in support for mobility, dynamic clustering, and microservice orchestration. These capabilities directly align with the schemes proposed in this work. iFogSim2 extends the original iFogSim with modular components for service migration, distributed cluster formation, and microservice management and provides realistic modeling of heterogeneous fog/edge hierarchies and dataset integration. In our study, iFogSim2 is configured conceptually to mirror the VEFC architecture: vehicles operate as mobile edge entities, RSUs map to fog gateways, proxy servers represent tier-1 network nodes, and microservice modules are deployed according to the proposed mobility scheme. The simulator’s mobility models (directional and random) and clustering engine are enabled to support the proposed schemes. The EUA dataset–based spatial configurations are imported through the ’DataParser’ module, allowing us to evaluate the proposed framework under realistic mobility, resource heterogeneity, and service-migration conditions.

5. Simulation Setup

The independent and scalable nature of the microservices is the key characteristic to adopt the modular approach for decentralized applications. To horizontally scale among multiple microservice instances, load balancing and scheduling policies can benefit from the dynamic clustering of the edge/fog nodes [29]. All the evaluations are performed by incorporating the EUA dataset [30]. In our evaluations, we have implemented two different scenarios. The first scenario compared the proposed adaptive area-based traffic management (AABTM) framework with the traditional centralized framework. In the second scenario, we have evaluated our proposed DMA-clustering approach with the Edgeward placement approach defined below:

- Edgeward: this placement technique only considers the vertical scalability of application modules without taking fog node clustering and horizontal scalability-based load balancing into consideration [31].

- DMA-clustering: this approach makes use of both the dynamic vehicular clustering (DVC) algorithm [32] and the dynamic microservice assignment (DMA) scheme.

The EUA dataset contains real-world spatial information for communication infrastructure in major Australian cities, including RSU coordinates, elevation profiles, and physical separation between nodes. These values directly reflect realistic deployment constraints used by the Australian Communications and Media Authority. Vehicular positions in our simulations follow mobility distributions derived from the EUA spatial grid to ensure realistic road-network density and RSU coverage patterns. This strengthens the fidelity and applicability of our results. To ensure reproducible and statistically robust evaluation, each simulation configuration was executed for 20 independent runs using different random seeds for mobility traces, vehicle positions, and microservice-placement events The results are reported as mean values with 95% confidence intervals. The results include these confidence intervals as error bars.

5.1. Scenario 1

This scenario is designed to assess the performance improvement offered by the proposed AABTM architecture over centralized implementation. The simulation environment for scenario 1 is aligned with the EUA dataset, having 118 RSUs positioned at 12 different microzones across the Melbourne Central Business District. In all simulations, the proxy server (tier-1 nodes) is connected to the cloud server (tier-0 nodes), with a varying number of vehicles with randomly generated locations. The specifications of the devices used in the evaluations are described in Table 3. The specifications are expressed in Million Instructions Per Second (MIPS) for processing speed, while energy parameters are given in Mega Joules (MJ). The duration of all the simulations performed is 20,000 s. The specifications of the microservices deployed during the evaluations are described in Table 4. The scenario is evaluated with a variable number of vehicles (10–34). The results of multiple simulations illustrate that the proposed scheme outperforms the centralized urban traffic management approach against various vital network metrics. The proposed decentralized microzone-based architectural approach achieves a significant reduction in average latency and network consumption. Further results are discussed in the subsequent subsections.

Table 3.

Simulation parameters used during the evaluations.

Table 4.

Specifications of the microservices placed during the evaluations.

5.2. Scenario 2

To evaluate the proposed policies in an adaptive area-based framework, we performed multiple simulations using the same parameters as described in Table 3 and Table 4. In all our evaluations, we have divided the large urban area into three/multiple management units called microzones, with one proxy server per microzone. Each microzone contains thirteen fog nodes as RSUs for processing traffic information. We have performed simulations with a varying number of vehicles (from 10 to 60). The dynamic vehicular clustering (DVC) algorithm, along with the dynamic microservice assignment (DMA) algorithm, called DMA-clustering, is employed to manage communication, energy consumption, network load, and execution costs for the vehicles.

6. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the evaluations performed on multiple scales for both scenarios.

6.1. Results for Scenario 1

The following subsections briefly present the key performance outcomes observed under Scenario 1.

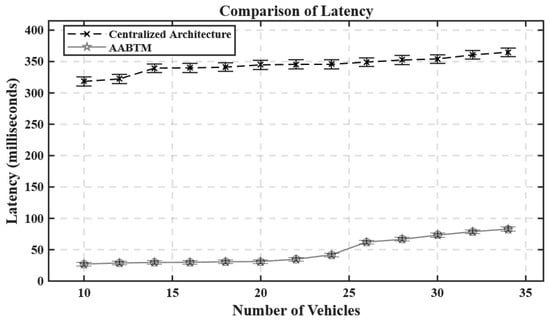

6.1.1. Latency

We evaluated the proposed vehicle management scheme against the traditional centralized urban traffic management architecture under varying vehicular traffic load conditions. The average delay is considered in the control loop, which in our case consists of Vehicle → Data Collection → Microzone Traffic → Emergency Control/Storage. Since this loop is highly latency-sensitive, a lower delay reflects more efficient deployment. The proposed scheme significantly reduces the delay by dividing the urban traffic load across different microzones and providing information processing near the network edge, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Latency comparison between the proposed and traditional ITS architectures.

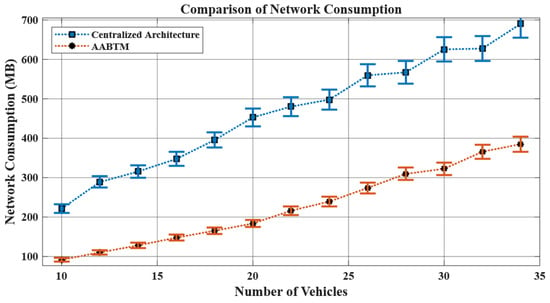

6.1.2. Network Usage

The distribution of the urban vehicular information load across various resource-constrained distributed nodes reduces the burden on the network. As compared to the centralized processing, the distributed network nodes only have to process the information of their relevant microzone, thus providing a significant reduction in network utilization, as shown in Figure 5. Additionally, processing near the vehicular infrastructure also reduces the unnecessary data transfer between tiers; therefore, it is a suitable choice for large-scale deployment and reliable network performance.

Figure 5.

Network consumption during the proposed and traditional deployments.

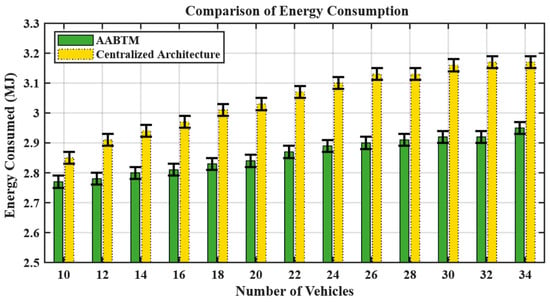

6.1.3. Energy Consumption

Figure 6 illustrates the energy consumed across different evaluations performed under different traffic conditions. The results show that energy usage depends on the number of microservices running on each tier. The proposed adaptive area-based deployment provides enough resources per area to minimize the recursive processing requests to upper tiers, providing a significant reduction in energy consumption.

Figure 6.

Energy consumption during the traditional and proposed framework.

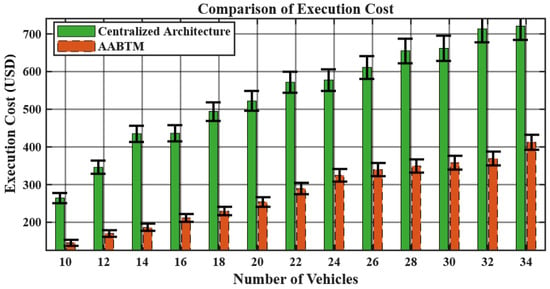

6.1.4. Execution Cost

The distribution of the urban traffic load into multiple units reduces the processing load on the network devices. This distribution of resources throughout the network and provision of processing near the network edge reduces the burden on the network. In the AABTM framework, most of the processing is performed through the distributed fog/edge nodes. This distributed provision of processing near the edge significantly reduces the execution cost. In a distributed architecture, network nodes only have to process the information of their relevant microzone, thus providing a significant reduction in processing cost, as shown in Figure 7. Additionally, processing near the vehicular infrastructure also reduces the unnecessary transfer of information between tiers; therefore, it is a suitable choice for large-scale deployment and reliable network performance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of execution cost.

6.2. Results for Scenario 2

The following subsections briefly present the key performance outcomes observed under Scenario 2.

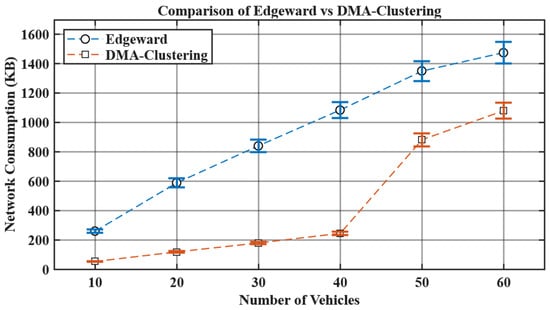

6.2.1. Network Utilization

In vehicular edge/fog computing, network usage is a critical metric for evaluating system performance. With an increase in the number of vehicles, the amount of information exchange between vehicles, RSUs, and the cloud grows instantaneously. This information surge can lead to network congestion, service interruptions, and increased latency, particularly in high-density traffic scenarios. Incorporation of DMA-clustering helps to localize communications and optimize the data flow. The provision of information processing at the network edge, efficient microservice migration, and reduction in the unnecessary information transmissions to the cloud server significantly reduce the network congestion, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of network consumption.

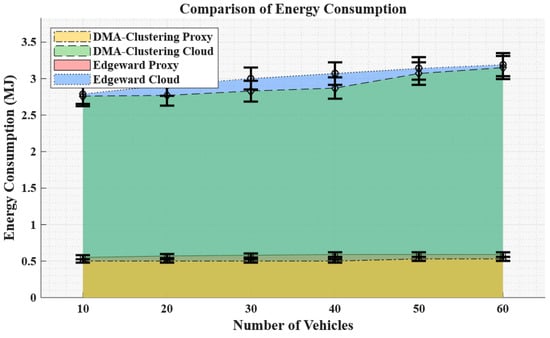

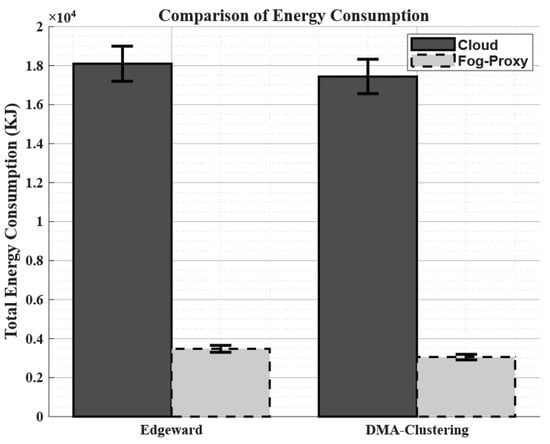

6.2.2. Energy Consumption

The energy consumption of a system is a significant factor in evaluating the efficiency of a modular system and depends on the applied microservice placement approach. Figure 9 illustrates that incorporating the DMA-clustering approach provides reduced energy consumption as compared to the Edgward placement. The cloud server and proxy nodes consume less energy while incorporating the DMA-clustering approach as compared to the Edgeward placement.

Figure 9.

Energy consumption at different network nodes.

Figure 10 illustrates the overall reduction in energy utilization through the incorporation of the DMA-clustering strategy. This reduction is due to the efficient assignment and migration of microservices throughout the cluster. The proposed approach optimizes the network scalability and ensures a gradual increase in energy consumption with an increase in the vehicular load. The proposed approach provides an efficient and scalable solution for the implementation of a traffic management system.

Figure 10.

Total energy consumption comparison between Edgeward and DMA-clustering.

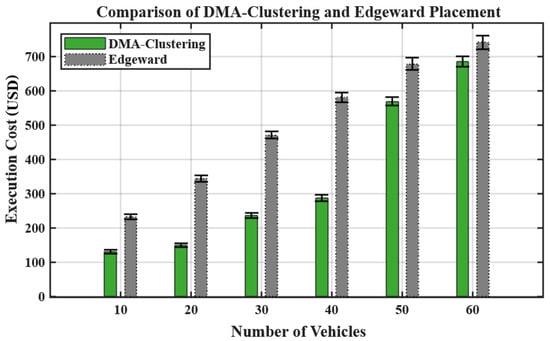

6.2.3. Execution Cost

With an increase in vehicular traffic, there is an increase in the execution cost, as shown in Figure 11. The DMA-clustering approach efficiently manages the cluster formation and task allocation to ensure that processing loads are balanced and there is a controlled growth of execution cost rather than exponentially. Furthermore, this approach enhances the efficiency of the network through localizing communications and reducing reliance on a centralized infrastructure.

Figure 11.

Execution cost during the traditional and proposed framework.

The incorporation of DMA-clustering dynamically adjusts the communication, energy consumption, network, and microservice allocation for efficient real-time traffic management. This results in an improved network performance, making the system scalable, cost-efficient, and well-suited for dynamic vehicular environments. As compared to Edgeward placement, the DMA-clustering achieves an average reduction of 59.2% in network consumption. Moreover, a 5% reduction in energy consumption and a 38.39% reduction in execution cost are also observed.

Table 5 presents the performance comparison between proposed schemes.

Table 5.

Performance comparison between proposed schemes.

7. Conclusions

In this research, we have implemented an adaptive area-based traffic management framework for efficient vehicular management. The employed framework divides the metropolitan area into smart zones that are supervised using a decentralized computing approach. We proposed a mobility management scheme for seamless service migration between the RSUs, considering the location and speed of vehicles. Then, we proposed a dynamic clustering algorithm that groups the RSUs based on proximity, communication range, and offered latency to ensure efficient and reliable V2I communication. Finally, we presented a dynamic microservice assignment scheme that ensures the effective placement of microservices, according to the availability of resources and the location of network nodes. We have evaluated the proposed schemes on multiple scales, incorporating the EUA Dataset, containing location information for the edge/fog nodes deployed across different regions of major cities in Australia. The results illustrate that the proposed framework significantly outperforms traditional vehicular architectures in terms of various performance metrics. The proposed AABTM and DMA-clustering schemes significantly improve the implementation of an intelligent vehicular management system through the provision of a scalable and efficient architecture. The proposed schemes provide significant improvement in vital network parameters. AABTM achieves reductions of 86.4% in latency, 53.3% in network consumption, 6.2% in energy usage, and 48.3% in execution cost, while DMA-clustering reduces network consumption by 59.2%, energy usage by 5%, and execution cost by 38.4% compared to traditional cloud-based urban traffic management frameworks.

7.1. Limitations

This study operates under several simplifying assumptions that may limit full real-world generalization. The infrastructure model assumes fixed RSU placements, stable connectivity, and uniform computing resources within each microzone, which may not reflect heterogeneous city deployments. The evaluation relies on simulation using iFogSim2 and the EUA dataset, which provide realistic spatial constraints but do not capture dynamic traffic behaviors, wireless interference, or failure scenarios. The mathematical modeling also simplifies the latency and cost components, omitting congestion effects and fine-grained mobility variability. These constraints indicate that additional validation using integrated mobility simulators and field-level datasets is required to fully assess the deployment-scale performance.

7.2. Future Directions

The framework shows strong improvements but is limited by simplified iFogSim2 simulations, controlled experimental conditions, and EUA data that do not reflect real-world variability. These constraints indicate the need for future field validation using diverse datasets and resilience-focused designs. We have planned to integrate a complete mobility simulator (SUMO/Veins) with our VEFC architecture to enable more realistic traffic-flow modeling, vehicular trajectories, and mobility-aware validation. Our future work will be focused on the design of lightweight machine learning-based approaches for module placement and migration. Additionally, more robust algorithms will be developed for large-scale vehicular systems for reliability [33,34], scalability, and adaptability. We aim to apply federated learning for secure privacy-preserving decisions in the future, using distributed machine learning modules in iFogSim, and use autonomous agent coordination through multi-agent fog controllers to improve the resilience in multi-tier vehicular fog migration. Future work can focus on further improving the scalability of the proposed framework by exploring the integration of more sophisticated machine learning algorithms for real-time traffic prediction and congestion management. We also plan on integrating vehicle location prediction models [35] to improve the performance of mobility management and resource allocation. Moreover, in the future, we plan to conduct a more detailed analysis of real-world deployment costs, communication overhead, and large-scale scalability to further validate the practicality of the microzone architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.H.; methodology, S.R.H.; software, S.R.H.; validation, S.R.H.; formal analysis, S.R.H. and A.M.; investigation, S.R.H. and A.M.; resources, A.M.; data curation, S.R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.H.; visualization, S.R.H.; project administration, S.R.H.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Musa, A.A.; Malami, S.I.; Alanazi, F.; Ounaies, W.; Alshammari, M.; Haruna, S.I. Sustainable traffic management for smart cities using internet-of-things-oriented intelligent transportation systems (ITS): Challenges and recommendations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, F.; Rehman, S.U.; Choi, A. Vision-AQ: Explainable Multi-Modal Deep Learning for Air Pollution Classification in Smart Cities. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, A.; Al Abdouli, K.M.; Badshah, A. Emerging Computing Tools for Emergency Management: Applications, Limitations and Future Prospects. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2025, 6, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzio, E.; Drożdż, W.; Kolon, M. The Role of Intelligent Transport Systems and Smart Technologies in Urban Traffic Management in Polish Smart Cities. Energies 2025, 18, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X. The Key Technologies of New Generation Urban Traffic Control System Review and Prospect: Case by China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Lazarova-Molnar, S.; Jawhar, I. Applications of integrated IoT-fog-cloud systems to smart cities: A survey. Electronics 2021, 10, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.; Sheldon, F.T. IoT–Cloud Integration Security: A Survey of Challenges, Solutions, and Directions. Electronics 2025, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.R.; Ahmad, I.; Ahmad, S.; Alfaify, A.; Shafiq, M. Remote pain monitoring using fog computing for e-healthcare: An efficient architecture. Sensors 2020, 20, 6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.R.; Rashad, M.; Goundar, S. Cloud computing to fog computing: A paradigm shift. In Edge Computing—Technology, Management and Integration; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.R.; Rehman, A.U.; Alsharabi, N.; Arain, S.; Quddus, A.; Hamam, H. Design of load-aware resource allocation for heterogeneous fog computing systems. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerna, A.; Bitam, S.; Calafate, C.T. Roadside unit deployment in internet of vehicles systems: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Kim, B.; Lin, C.W.; Shiraishi, S.; Xie, J.; Han, Z. Architectural design alternatives based on cloud/edge/fog computing for connected vehicles. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 2349–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, A.; Mondal, K.K.; Das, D.; Buyya, R. Clouds on the road: A software-defined fog computing framework for intelligent resource management in vehicular ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 12778–12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Luan, W. A dynamic road incident information delivery strategy to reduce urban traffic congestion. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2018, 5, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Luan, W. A two-level traffic light control strategy for preventing incident-based urban traffic congestion. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 19, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Xu, W.; Zhang, L.; Cao, B.; Tang, M.; Yang, Q. Location-Aware Dynamic Scaling of Microservices in Mobile Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 4288–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, S.; Madda, R.B.; Patan, R.; Jiao, P.; Barri, K.; Alavi, A.H. Internet of things-based fog and cloud computing technology for smart traffic monitoring. Internet Things 2021, 14, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Patni, S.; Hwang, S.O. A Comprehensive Analysis of Privacy-Preserving Solutions Developed for IoT-Based Systems and Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, H. Intelligent traffic light under fog computing platform in data control of real-time traffic flow. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 4461–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishk, A.M.; Badawy, M.; Ali, H.A.; Saleh, A.I. A new traffic congestion prediction strategy (TCPS) based on edge computing. Clust. Comput. 2022, 25, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamel, S.A.; Saleh, A.I.; Ali, H.A. A fog-based Traffic Light Management Strategy (TLMS) based on fuzzy inference engine. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 2187–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahil; Sood, S.K.; Chang, V. Fog-Cloud-IoT centric collaborative framework for machine learning-based situation-aware traffic management in urban spaces. Computing 2024, 106, 1193–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Atawi, A.A. Enhancing data management and real-time decision making with IoT, cloud, and fog computing. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. 2024, 14, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, F.M.; Gamel, S.A. Smart navigation system for emergency vehicles (SNSEV): Utilizing fog and cloud computing technology for real-time traffic management. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 15547–15571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, G.A.; Mitchell, P.D.; Henson, B. Localization of AUVs for Ship Hull Inspection: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 77468–77480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Deb, S.; Goswami, A.K.; Al Mansur, A.; Ustun, T.S. Congestion management in distribution system integrating plug-in electric vehicles: A review. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2025, 43, 01445987251348673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, M. Internet of Things-enabled unmanned aerial vehicles for real-time traffic mobility analysis in smart cities. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, R.; Pallewatta, S.; Goudarzi, M.; Buyya, R. iFogSim2: An extended iFogSim simulator for mobility, clustering, and microservice management in edge and fog computing environments. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 190, 111351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.T.; Chandrasekaran, K. Straddling the crevasse: A review of microservice software architecture foundations and recent advancements. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2019, 49, 1448–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Cui, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Deng, S.; Jin, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y. A game-theoretical approach for user allocation in edge computing environment. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2019, 31, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Vahid Dastjerdi, A.; Ghosh, S.K.; Buyya, R. iFogSim: A toolkit for modeling and simulation of resource management techniques in the Internet of Things, Edge and Fog computing environments. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2017, 47, 1275–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutiq, M.; Sellami, L.; Alaya, B. Dynamic Vehicular Clustering Enhancing Video on Demand Services Over Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 3493–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behura, A.; Kumar, A.; Jain, P.K. A comparative performance analysis of vehicular routing protocols in intelligent transportation systems. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Macêdo, A.R.L.; Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; da Costa, K.A.P.; Acharya, K.; Song, H.; Guizani, M.; De Albuquerque, V.H.C. Quantum AI-Enhanced IoT-Fog Communication: A Survey from Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Muhammad, A.; Mehmood, F.; Song, W.C. Enhancing vehicle location prediction accuracy with road-aware rectification for multi-access edge computing applications. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).