Abstract

We introduce an ultra-compact, single-neuron-per-class end-to-end readout for binary classification of noisy, image-encoded sensor time series. The approach compares a linear single-unit perceptron (E2E-MLP-1) with a resonate-and-fire (RAF) neuron (E2E-RAF-1), which merges feature selection and decision-making in a single block. Beyond empirical evaluation, we provide a mathematical analysis of the RAF readout: starting from its subthreshold ordinary differential equation, we derive the transfer function , characterize the frequency response, and relate the output signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) to and the noise power spectral density (brown, pink, and blue noise). We present a stable discrete-time implementation compatible with surrogate gradient training and discuss the associated stability constraints. As a case study, we classify walk-in-place (WIP) in a virtual reality (VR) environment, a vision-based motion encoding (72 × 56 grayscale) derived from 3D trajectories, comprising 44,084 samples from 15 participants. On clean data, both single-neuron-per-class models approach ceiling accuracy. At the same time, under colored noise, the RAF readout yields consistent gains (typically +5–8% absolute accuracy at medium/high perturbations), indicative of intrinsic band-selective filtering induced by resonance. With ∼8 k parameters and sub-2 ms inference on commodity graphical processing units (GPUs), the RAF readout provides a mathematically grounded, robust, and efficient alternative for stochastic signal processing across domains, with virtual reality locomotion used here as an illustrative validation.

Keywords:

end-to-end learning; single-neuron-per-class readout; neuromorphic computing; image-encoded time series; neural networks; spiking neural networks; resonate-and-fire (RAF) neuron; noisy environments MSC:

68T07; 68U10; 62M10

1. Introduction

End-to-end learning often relies on multi-layer architectures that separate input preprocessing, representation learning, and decision-making [1]. While effective, this separation, typical of models such as the multi-layer perceptron (MLP) [2], can result in substantial parameter counts and limited insight into where robustness emerges. We study a minimal alternative: a single-neuron-per-class readout that operates directly on high-dimensional, image-encoded sensor time series, integrating feature selection and classification into a single block.

We instantiate this idea with two models: a linear single-unit perceptron (E2E-MLP-1) and a single-unit resonate-and-fire (E2E-RAF-1) neuron [3], a neuromorphic spiking model whose subthreshold dynamics implements a tunable, band-selective filter [4]. We develop a mathematical analysis of the RAF transfer function and its noise-shaping properties under colored noise, and we provide a stable discrete-time implementation suitable for training with surrogate gradients [5].

To illustrate the generality and performance of this approach, we present a case study that classifies walk-in-place (WIP) movements within a virtual reality (VR) environment. This classification is based on visual-style encodings of human motion data, a common technique for transforming sensor time series data for classification [6]. This validation is not the focus of the contribution but serves as a practical example showing that (i) single-neuron-per-class readouts can achieve near-ceiling accuracy on clean inputs, and (ii) the RAF dynamics confer robustness advantages in colored-noise regimes (pink, brown, and blue noise) that mimic real-world sensing artifacts [7,8].

The contribution is methodological and demonstrates that a single-neuron-per-class readout can effectively discriminate image-encoded time series while avoiding deep, layered models. The experimental section is thus positioned as a direct application example to illustrate the behavior and efficiency of the proposed readouts in a controlled setting.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 details the proposed architecture and experimental setup. Section 4 describes the mathematical analysis of the RAF Readout. Section 5 illustrates the generality and performance of the proposed approach on vision-style encodings of human motion data. Section 6 presents the results. Section 7 discusses findings, and Section 8 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Work

This section presents a comprehensive review of the theoretical foundations that underpin our innovative approach of utilizing a single neuron per class for readout. We will explore conventional neural architectures, delve into neuromorphic spiking models, and analyze the noise characteristics present in sensor data, highlighting their crucial roles in the effectiveness of our methodology.

2.1. Conventional Neural Architectures

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) form the basis of modern machine learning, with multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) serving as a foundational architecture that showcases the power of layered processing to unlock intricate patterns and insights in vast datasets [9]. MLPs perform hierarchical feature extraction through layers of computational units, applying a weighted sum followed by a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU) [2]. Their capacity to model complex functions is supported by universal approximation theorems [10]. However, their layered structure can be parameter-heavy, posing challenges for deployment in resource-constrained or embedded settings, which motivates the exploration of more compact models.

2.2. Neuromorphic Computing and Spiking Models

Spiking neural networks (SNNs) offer an alternative paradigm inspired by neurobiology, leveraging event-driven processing that can lead to greater energy efficiency and robustness for dynamic signals [11]. The resonate-and-fire (RAF) neuron is a significant model governed by a second-order ordinary differential equation (ODE): , where V is the neuron membrane potential, is the damping factor, is the angular frequency, and is the input current [3]. This dynamic model exhibits intrinsic frequency selectivity, making it particularly suitable for processing time-varying inputs. Despite the non-differentiable nature of spike generation, such models can be trained effectively within deep learning frameworks using surrogate gradients to approximate the derivative of the spiking mechanism [5].

2.3. Noise Models in Sensing

Sensor data in real-world applications is rarely corrupted solely by simple white noise. Instead, noise often exhibits temporal correlations, leading to power spectral densities that follow a power-law distribution, [7]. Common examples include brown noise ( or ), which models processes like random walks or sensor drift; pink noise ( or ), prevalent in many natural systems, and blue noise ( or ), representing high-frequency jitter [12].

Testing the performance of WIP in VR with colored noise is essential for several reasons:

- Realistic environmental conditions. Colored noise (such as pink, brown, or other non-white noise spectra) more accurately simulates real-world environments. Evaluating WIP performance under these conditions ensures that the system functions reliably in typical user scenarios.

- Assessing robustness and reliability. Background noise can interfere with motion tracking and user perception. Testing under colored noise helps assess how well the system maintains accurate, consistent locomotion, ensuring users do not experience disorientation or motion sickness from tracking errors exacerbated by noisy environments.

- Optimizing system performance. By analyzing how colored noise affects WIP performance, developers can refine motion-detection algorithms, improve noise-filtering techniques, and enhance overall system robustness. This leads to more seamless and immersive VR experiences.

- User experience and comfort. Ensuring that walk-in-place methods perform well under various auditory conditions helps prevent user frustration or discomfort, making VR systems more accessible and enjoyable across diverse environments.

Robust classifiers benefit from frequency-selective mechanisms that can align with signal-dominated frequency bands while attenuating off-band perturbations, a property central to our investigation of the RAF neuron.

2.4. Frequency-Awareness and Compact Architectures

While deep learning has trended towards increasingly complex architectures, parallel efforts in “TinyML” focus on reducing computational overhead via model pruning, quantization, and efficient architectures such as MobileNet and SqueezeNet [13]. However, these lightweight CNNs still rely on layered hierarchies, as in foundational architectures such as LeNet-5 [14]. Simultaneously, recent research has highlighted the importance of spectral biases in neural networks, exploring frequency-domain learning and generative adversarial networks (GANs) with frequency-awareness to handle structural anomalies and noise [15,16].

In this landscape, our single-neuron readouts are intentionally minimal. Unlike deep compact models, the proposed E2E-MLP-1 provides a flat frequency response, whereas the RAF neuron implements a tunable, band-selective filter through its second-order dynamics. This distinction anticipates our findings under colored noise, where spectral shaping is central. We position the proposed readouts against lightweight CNNs by reporting parameter/latency trade-offs and by discussing when hierarchical features (convolutions) are strictly necessary versus when a bio-inspired, band-selective readout suffices for robust classification.

3. Methods: A Single-Neuron-per-Class End-to-End Readout

We propose a method for classifying 2D grayscale images (in our case study, 72 × 56, corresponding to 4032 pixels) that encode short windows of sensor time series. The core of the method is a single-neuron-per-class readout that integrates feature selection and classification.

3.1. Single-Unit Readouts

- E2E-MLP-1 (Linear + threshold). Given a flattened input vector , this model computes a logit . The final binary decision is obtained by applying a threshold, implicitly handled by the logistic loss function during training.

- E2E-RAF-1 (Resonate-and-fire). This model is a single Resonate-and-Fire (RAF) neuron [3] whose subthreshold membrane potential V obeys the second-order ordinary differential equation:with a learnable damping ratio , angular frequency , and an input drive proportional to the weighted input. Spikes are generated when V crosses a learnable threshold . The final decision is based on the spike count or firing rate over a discrete simulation window. All model parameters, including the neuron’s intrinsic parameters and the input weights that determine , are trained end-to-end using surrogate gradients to handle the non-differentiable spiking event [5].

3.2. Input Handling

Input images are converted to one-dimensional vectors, with each pixel’s intensity scaled to . This normalization process ensures that the values are standardized, facilitating more effective analysis and processing in various computational tasks. For the E2E-RAF-1 neuron, these analog intensity values are converted into spike trains. We used Poisson-distributed spike trains where the firing rate of each input neuron is proportional to the corresponding pixel intensity [17].

3.3. Training Protocol

Models were trained using the Adam optimizer [18] with a binary cross-entropy loss function on the logits (BCEWithLogitsLoss). We used a batch size of 512 and trained for up to 150 epochs, with an early stopping mechanism that terminated training if the validation loss did not improve for 20 consecutive epochs. The initial learning rate was set to and was reduced by a factor of 0.9 if the validation loss plateaued (with a minimum learning rate of ). To ensure robust results, all experiments were repeated with at least 5 different random seeds. Models were implemented in PyTorch 1.12.1 and trained on an NVIDIA Quadro RTX 6000 GPU.

3.4. Robustness Stress Tests

To rigorously evaluate model robustness, we conducted stress tests by adding colored noise to the clean test set inputs. We used three types of noise with distinct spectral properties:

- Brown Noise: Power spectral density (PSD) proportional to ;

- Pink Noise: PSD proportional to ;

- Blue Noise: PSD proportional to .

The noise was generated in the frequency domain by shaping Gaussian white noise to the target PSD and then transforming it to the input domain via an inverse Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). We systematically varied the noise intensity by sweeping the noise standard deviation from 0 to in steps of . Final performance metrics are reported as the mean and standard deviation across multiple seeds. To assess statistical significance between model predictions under noise, we use McNemar’s test, which is appropriate for comparing paired categorical data.

4. Mathematical Analysis of the RAF Readout

In this section, we delve into the continuous-time representation of the subthreshold resonate-and-fire (RAF) dynamics, modeling it as a linear time-invariant (LTI) second-order system. By analyzing its transfer function and frequency response, we uncover the conditions under which the system exhibits resonance and how this influences signal processing capabilities. We further explore how the resonant properties can be harnessed to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in noisy environments, particularly by tuning system parameters to favor task-relevant frequencies. Finally, practical considerations for discretizing the dynamics for training and inference are discussed, alongside alternative implementations and the transition from subthreshold filtering to classification.

4.1. Continuous-Time Dynamics and Transfer Function

We consider the subthreshold RAF dynamics as a linear time-invariant (LTI) second-order system driven by an input current :

with damping ratio and angular frequency . In the frequency domain (), the transfer function from input I to membrane potential V is

Thus, the power gain is

The resonance peak corresponds to the maximum of with respect to . Since the denominator determines the magnitude, the peak occurs at the frequency where the denominator is minimized

To find , we set the derivative of with respect to to zero

We obtain the following equation

This yields two solutions

- On the one hand, the trivial solution, i.e., .

- On the other hand, the non-trivial solution where the bracketed term is zeroSolving for , we obtain the resonance frequency

For the resonance peak to exist at a real frequency , the expression under the square root must be positive

In summary, the power gain exhibits a resonance with a peak at , considering that .

4.2. Noise Shaping and Output Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

Let the signal component have a PSD denoted by and the additive noise PSD be , with modeling brown (), pink (), and blue () noise, respectively, up to a proportionality constant c.

The output SNR induced by the subthreshold dynamics is

Assume that is band-limited and peaks around and for . Considering that , there exists a value in a neighborhood of that maximizes in Equation (5). In this way, approximating locally by its value at and using Laplace’s method yields , which is maximized when , and, therefore, . The noise term decreases as the peak narrows and as the peak moves toward frequencies where is smaller. For (brown), noise power is higher at low ; for (pink), it still favors low frequencies but less steeply; for (blue), it increases with . Tuning near the signal band reduces the overlap with regions of larger noise power, and the relative advantage over a flat filter grows.

In essence, the RAF acts as a frequency selector by tuning so that concentrates around the dominant signal frequency; the denominator in Equation (5) is suppressed when puts relatively more noise outside that band.

4.3. Discrete-Time Implementation for Training and Inference

For learning and deployment, we used a first-order state-space discretization, in particular, the explicit Euler method. We also implemented the semi-implicit Euler and the Runge-Kutta 4 method, but the differences in results were not statistically significant. Using the explicit Euler method, we may define and . From Equation (2) follows:

Now, using a sampling step , we obtain the next discrete equations:

To ensure stability, we select such that , which is a criterion for properly sampling the harmonic oscillator. We also utilize the same time grid as the spike window. The spike readout uses a hard threshold :

During training we use a standard surrogate-gradient around the threshold with slope .

4.4. Alternative IIR (Bilinear) Form

4.5. From Subthreshold Filtering to Decisions

Let the spike count in a T-step window be . The classifier output is either the firing rate or a post-threshold logistic score. Under mild regularity, r increases with the band-power of the filtered signal, thus implementing a band-selective energy detector. This explains the improved robustness under colored noise.

5. Case Study: Vision-Based Motion Encodings

This section provides a direct application example to illustrate the behavior of the proposed readouts on a realistic binary task. 3D motion trajectories from a head-mounted display and hand controllers are projected onto two planes and accumulated over a short temporal buffer to yield 72 × 56 grayscale images (4032 pixels). The dataset comprises 44,084 samples from 15 participants, with subject-independent splits to avoid data leakage.

5.1. Acquisition and Image Encoding

Data were recorded using a consumer-grade virtual reality headset (Meta Quest 3) with inside-out tracking at a sampling rate of 90 Hz [19]. Each image sample encodes approximately 1.1 s of motion via a temporal buffer of frames. The 3D coordinates are first projected onto the frontal (XY) and depth (YZ) planes. Unlike approaches that aim to reconstruct the whole 3D geometry from such frontal views [20], here we leverage these projections solely for efficient classification. These projected coordinates are then normalized to the range :

We map raw 3D head/hands coordinates to lightweight 2D motion encodings. Normalized coordinates are scaled to image indices (), and clamped. Per frame, we build two binary views—frontal (XY) and depth-integrated (YZ/XZ)—and concatenate them; trajectories are emphasized via max-pool aggregation over the last M frames. Unlike complex foreground segmentation techniques used in uncontrolled environments [21], this lightweight projection suffices for the controlled VR tracking setup while minimizing computational load. Labeled PNGs (e.g., “WIP”/“non-WIP”) form the dataset, using an 80/20 split to assess overall generalization. A temporal buffer accumulates these normalized traces to highlight movement patterns over the 100-frame window, thereby enhancing the visual representation of motion dynamics.

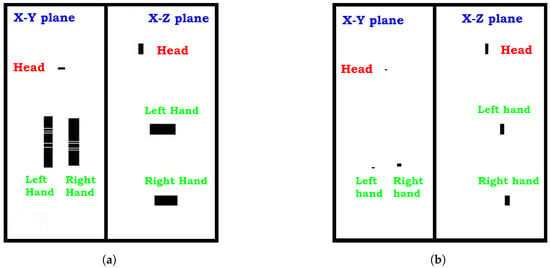

The final image is created by concatenating the processed frontal and depth planes. Figure 1 provides examples of the resulting encoded images for the two motion classes, highlighting the 3D sensor position (Head, Left Hand and Right Hand).

Figure 1.

Examples of 2D image encodings from the validation case study. (a) A sample from Class 1 (periodic motion), showing structured, repetitive traces from the head and hand sensors. (b) A sample from Class 2 (aperiodic motion), showing more irregular patterns. Each 72 × 56 pixel image combines normalized frontal (XY) and depth (YZ) plane projections accumulated over a 100-frame window.

5.2. Train/Test Splits and Statistical Analysis

We use an 80/20 split for training and testing, stratified across participants to ensure a subject-independent evaluation. The training set consists of 35,267 images, and the test set contains 8817 images. All experimental results report the mean and standard deviation (mean ± std) across at least five independent runs with different random seeds. For the noise robustness comparisons, we employ McNemar’s paired test to assess the statistical significance of the differences in predictions made by the two models.

6. Results

This section presents the performance of the proposed readouts. We first establish a baseline performance on clean data and then evaluate its robustness under systematic noise stress tests, interpreting the findings within the context of our case study.

6.1. Clean-Data Performance and Computational Efficiency

On the clean validation dataset, both single-neuron-per-class readouts achieve near-ceiling classification accuracy:

- E2E-MLP-1 Accuracy: 99.91% ± 0.3%.

- E2E-RAF-1 Accuracy: 99.68% ± 0.4%.

These results indicate that a single-neuron-per-class readout can solve this task with remarkably few parameters. Reported CNN-based systems for related VR motion detection tasks typically reach accuracies in the 90–95% range, such as 94% reported by [22] for treadmill-based locomotion and 92% by [23] for real-time walking-in-place detection. In contrast, our single-neuron-per-class models achieve near-ceiling accuracy on the dataset while using fewer parameters. Specifically, for E2E-MLP-1, the calculation is as follows: parameters. For E2E-RAF-1, the calculation is: parameters. This is significantly fewer parameters than the tens of thousands typically found in CNNs. The models are also highly efficient. Inference latency on a desktop GPU (NVIDIA Quadro RTX 6000, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) averaged 0.5 ms for E2E-MLP-1 and 1.2 ms for E2E-RAF-1, making the approach suitable for real-time applications.

6.2. Robustness to Colored Noise

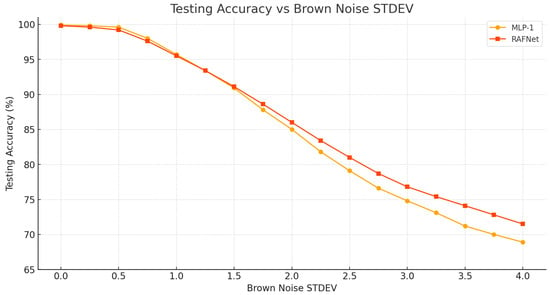

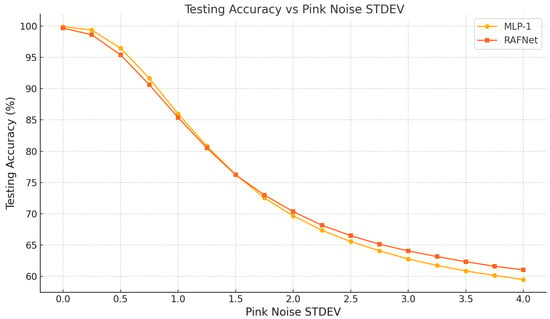

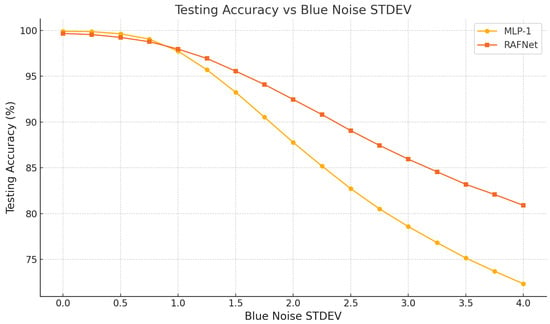

Under additive brown (), pink (), and blue () noise, the E2E-RAF-1 model consistently outperforms the linear readout. As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, the RAF-based model achieves a consistent accuracy advantage at medium-to-high perturbation levels. For example,

- Under brown noise at STDEV = 3.0, the performance gap is +2.2% (77.0.% vs. 74.8%).

- Under pink noise at STDEV = 3.0, the RAF model leads by +1.5% absolute accuracy (64.3% vs. 62.8%).

- Under blue noise, the advantage is most pronounced, reaching +4.7% at STDEV = 2.0 (92.4% vs. 87.7%).

Table 1.

Testing Accuracy (%) for E2E-MLP-1 and E2E-RAF-1 under different noise types and intensities. Values are mean ± STDEV across 5 seeds.

Table 1.

Testing Accuracy (%) for E2E-MLP-1 and E2E-RAF-1 under different noise types and intensities. Values are mean ± STDEV across 5 seeds.

| Noise Type | STDEV | E2E-MLP-1 | E2E-RAF-1 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown () | 0.0 | 99.91 ± 0.3 | 99.68 ± 0.4 | −0.23 |

| 1.0 | 96.1 ± 0.4 | 95.7 ± 0.5 | −0.4 | |

| 2.0 | 84.8 ± 0.6 | 85.8 ± 0.7 | +1.0 | |

| 3.0 | 74.8 ± 0.6 | 77.0 ± 0.7 | +2.2 | |

| 4.0 | 68.9 ± 0.6 | 71.6 ± 0.7 | +2.7 | |

| Pink () | 0.0 | 99.91 ± 0.3 | 99.68 ± 0.4 | −0.23 |

| 1.0 | 85.8 ± 0.5 | 85.5 ± 0.6 | −0.3 | |

| 2.0 | 69.9 ± 0.7 | 70.7 ± 0.8 | +0.8 | |

| 3.0 | 62.8 ± 0.7 | 64.3 ± 0.8 | +1.5 | |

| 4.0 | 59.5 ± 0.7 | 61.6 ± 0.8 | +2.1 | |

| Blue () | 0.0 | 99.91 ± 0.3 | 99.68 ± 0.4 | −0.23 |

| 1.0 | 98.8 ± 0.5 | 98.7 ± 0.6 | −0.1 | |

| 2.0 | 87.7 ± 0.7 | 92.4 ± 0.8 | +4.7 | |

| 3.0 | 78.6 ± 0.8 | 86.1 ± 0.9 | +7.5 | |

| 4.0 | 72.2 ± 0.8 | 80.9 ± 0.9 | +8.7 |

Figure 2.

Testing accuracy (%) with varying standard deviations of added brown noise. This comparison highlights the performance differences between the E2E-MLP-1 (shown by the yellow line) and the E2E-RAF-1 (represented by the orange line) under the influence of additive brown noise ().

Figure 3.

Testing accuracy (%) with varying standard deviations of added pink noise. This comparison highlights the performance differences between the E2E-MLP-1 (shown by the yellow line) and the E2E-RAF-1 (represented by the orange line) under the influence of additive pink noise ().

Figure 4.

Testing accuracy (%) with varying standard deviations of added blue noise. This comparison highlights the performance differences between the E2E-MLP-1 (shown by the yellow line) and the E2E-RAF-1 (represented by the orange line) under the influence of additive blue noise ().

Paired McNemar tests on the predictions confirm that these differences are statistically significant across all seeds (). This trend of superior robustness aligns with the frequency-selective filtering properties predicted by the mathematical analysis in Section 4, where the RAF neuron’s resonant dynamics act as an intrinsic filter against off-band noise.

These findings are consistent with this application example with the frequency-selective behavior predicted by the RAF transfer function analysis in Section 4, where resonance concentrates energy around task-relevant bands and attenuates off-band perturbations.

6.3. Interpretation Within the Motion Encoding Case Study

In the context of our validation case study, where the positive class represents periodic in-place stepping patterns and the negative class represents other hand/head motions, the single-neuron-per-class models achieve high performance. Both models effectively learn to distinguish these complex motion patterns from their 2D image representations. Crucially, under the simulated sensor noise, the E2E-RAF-1 model degrades more gracefully. This suggests that, for a practical motion classification application, the RAF-based readout would provide more reliable performance in real-world conditions, where sensor data is inevitably corrupted by noise, and would maintain usable accuracy at higher noise levels than the linear baseline.

6.4. Comparison with a Lightweight CNN Baseline

To contextualize the proposed readouts against a compact deep architecture, we trained a lightweight CNN (8 layers with early blocks of ∼100 feature maps, ReLU activations, and max-pooling, followed by a single fully connected classifier) on the same subject-independent splits and with the same optimizer/scheduler settings. As summarized in Table 2, the CNN attains 99.93% accuracy on clean data, which is comparable to the single-neuron-per-class readouts (99.91% for E2E-MLP-1; 99.68% for E2E-RAF-1). We therefore emphasize the architectural simplicity of single-neuron-per-class readouts for image-encoded time series in this case-study setting.

Table 2.

Clean-data accuracy in the case-study setting.

7. Discussion

Our primary contribution is both architectural and mathematical. We demonstrate that a single-neuron-per-class readout can effectively integrate feature selection and decision-making, challenging the necessity of deep, layered structures for certain high-dimensional classification tasks. The key insight is that the Resonate-and-Fire (RAF) neuron’s dynamics provide a principled mechanism for robustness under colored noise. Through its tunable resonance and bandwidth, controlled by the parameters , the neuron acts as an intrinsic, adaptive filter. The motion-encoding case study demonstrates that this minimal design achieves high accuracy with orders of magnitude fewer parameters than deep models typically used for similar representations.

7.1. Robustness in Complex Signal Environments

While our analysis focuses on specific noise colors (), real-world conditions often involve mixed noise types (e.g., a superposition of white sensor thermal noise and pink environmental drift). In such cases, the RAF’s selective advantage depends on the spectral dominance within the signal band . For broadband (non-band-limited) signals spanning the entire frequency spectrum, the benefits of the RAF’s band-pass filtering diminish relative to frequency-agnostic readouts. However, for the class of oscillating sensor signals typical of human motion (walking, gesturing), the band-selective property remains a critical asset for separating signal from complex background noise.

7.2. Limitations

The capacity of a single unit may be insufficient for tasks that fundamentally require extracting hierarchical features, such as recognizing complex objects in natural images. While we reported parameter counts and inference latency, a full analysis of Floating Point Operations (FLOPs) and energy consumption profiling on embedded devices remains as future work. Furthermore, our robustness evaluation focused on continuous colored noise; the study of its resilience to other types of perturbations, such as signal bursts, data dropouts, or spatial occlusions in the input images, also merits further investigation.

7.3. Outlook

The architectural simplicity and inherent robustness of the single-neuron-per-class readout open several promising avenues for future research. Extending the concept to small ensembles of resonant units or developing hybrid linear+RAF readouts could preserve computational compactness while improving expressive power. More advanced strategies, such as adaptive resonance, in which the neuron’s parameters adjust in real time to the statistics of the input signal, could further enhance performance. Critically, the mathematical analysis presented in Section 4 offers a blueprint not just for understanding the model, but for actively tuning the neuron’s parameters to align with the known spectral properties of a given task, bridging the gap between theory and practical application.

8. Conclusions

We presented a minimal end-to-end classifier that collapses feature selection, representation, and decision-making into a single-neuron-per-class. Validated on a challenging motion classification benchmark using image-encoded sensor time series, both a linear perceptron and a resonant Resonate-and-Fire (RAF) variant achieved near-ceiling accuracy (over 99.6%) on clean data. Crucially, the RAF readout showed clear, statistically significant advantages under colored noise, with performance gains of 5–8% at higher noise levels. With approximately 8000 parameters and millisecond-level inference latencies, this work demonstrates that single-neuron-per-class readouts are a promising architectural alternative for robust, low-latency signal processing. Overall, the paper should be read as a direct application example that evidences the feasibility and efficiency of single-neuron-per-class readouts for image-encoded time series in this setting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.-C. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.-C. and J.G.; writing—review and editing, D.B.-C. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E. Resonate-and-fire neurons. Neural Netw. 2001, 14, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlKhamissi, B.; ElNokrashy, M.; Bernal-Casas, D. Deep Spiking Neural Networks with Resonate-and-Fire Neurons. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.08234. [Google Scholar]

- Yanguas-Gil, A. Coarse scale representation of spiking neural networks: Backpropagation through spikes and application to neuromorphic hardware. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neuromorphic Systems 2020, Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.H.; Yu, C.; Liu, S.H.; Wang, C.W.; Taele, P.; Yu, N.H.; Chen, M.Y. Walkingvibe: Reducing virtual reality sickness and improving realism while walking in vr using unobtrusive head-mounted vibrotactile feedback. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Keshner, M.S. 1/f Noise. Proc. IEEE 1982, 70, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Paris, R.A.; Adams, H.A.; Bodenheimer, B. Improving Walking in Place Methods with Individualization and Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Osaka, Japan, 23–27 March 2019; pp. 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cybenko, G.V. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control Signals Syst. 1989, 2, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass, W. Networks of Spiking Neurons: The Third Generation of Neural Network Models. Neural Netw. 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S.M. Virtual Reality; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, N.; Baratin, A.; Arpit, D.; Draxler, F.; Lin, M.; Hamprecht, F.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. On the spectral bias of neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 5301–5310. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Ran, X.; Zhang, D. Unsupervised image stitching based on Generative Adversarial Networks and feature frequency awareness algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 183, 113466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.; Neil, D.; Liu, S.C.; Delbrück, T.; Pfeiffer, M. Real-time classification and sensor fusion with a spiking deep belief network. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meta Platforms, Inc. Meta Quest3 Specifications and Documentation. Available online: https://www.meta.com (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Beacco, A.; Gallego, J.; Slater, M. 3D objects reconstruction from frontal images: An example with guitars. Vis. Comput. 2023, 39, 5421–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego, J.; Pardàs, M.; Haro, G. Enhanced foreground segmentation and tracking combining Bayesian background, shadow and foreground modeling. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2012, 33, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakabe, F.K.; Ayres, F.J.; Soares, L.P. Machine Learning Applied to Locomotion in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Virtual and Augmented Reality, Manaus, Brazil, 30 September–3 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, S.; Steed, A.; Whitton, M.C. User-centered Redirected Walking and Resetting with Virtual Feelers. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Shanghai, China, 25–29 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).