Abstract

The rapid growth of user-generated content in the digital space has increased the necessity of properly and interpretively analyzing sentiment and emotion systems. This research paper presents a new hybrid model, HAM (Hybrid Attention-based Model), a Transformer-based contextual embedding model combined with deep sequential modeling and multi-layer explainability. The suggested framework integrates the BERT/RoBERTa encoders, Bidirectional LSTM, and Graph Attention that can be used to embrace semantic and aspect-level sentiment correlation. Additionally, an enhanced Explainability Module, including Attention Heatmaps, Aspect-Level Interpretations, and SHAP/Integrated Gradients analysis, contributes to the increased model transparency and interpretive reliability. Four benchmark datasets, namely GoEmotions-1, GoEmotions-2, GoEmotions-3, and Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews, were experimented on in order to have a strong cross-domain assessment. The 28 emotion words of GoEmotions were merged into five sentiment-oriented classes to harmonize the dissimilarity in the emotional granularities to fit the schema of the Amazon dataset. The proposed HAM model had a highest accuracy of 96.4% and F1-score of 94.9%, which was significantly higher than the state-of-the-art baselines like BERT (89.8%), RoBERTa (91.7%), and RoBERTa+BiLSTM (92.5%). These findings support the idea that HAM is a better solution to finer-grained emotional details and is still interpretable as a vital move towards creating open, exposible, and domain-tailored sentiment intelligence systems. Future endeavors will aim at expanding this architecture to multimodal fusion, cross-lingual adaptability, and federated learning systems to increase the scalability, generalization, and ethical application of AI.

Keywords:

hierarchical attention mechanism (HAM); aspect-based sentiment analysis (ABSA); explainable AI (XAI); transformer-based models; deep learning; emotion and sentiment classification MSC:

68T99

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of digital commerce and social networks, users generate enormous amounts of reviews for products and services daily. Extracting actionable insights manually from these data is infeasible. Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA) enables fine-grained sentiment detection by identifying opinions about specific aspects (e.g., “battery,” “camera,” “service”) rather than overall sentiment, which is critically important in domains like e-commerce, hospitality, and consumer electronics [1,2].

Early ABSA methods relied heavily on classical machine-learning models—SVMs, Naive Bayes, and LDA—with features crafted from lexical resources, POS tags, and n-grams. While successful to some extent, such models suffer from sparse representations, reliance on laborious feature engineering, and poor generalization to unseen contexts [3]. The introduction of dense word embeddings (Word2Vec, GloVe) helped by providing continuous, richer lexical representations, but even these lacked modeling of long-distance dependencies and aspect-specific contexts [4,5,6].

Neural network models such as CNNs and RNNs (especially LSTM, Bi-LSTM) improved performance by capturing sequential and local patterns in text. However, they still treated all tokens with relatively equal weight, lacking mechanisms to focus disproportionally on aspect-relevant tokens. Attention mechanisms addressed this by allowing models to assign higher weights to relevant words [7]. Simultaneously, Transformer-based pretrained models like BERT, RoBERTa, and their variants revolutionized NLP by encoding rich contextual information and long-range dependencies [8,9]. In ABSA, fine-tuning these models has led to substantial performance gains.

Although there is a great advancement in ABSA, there are some challenges in the existing strategies. To start with, simple concatenation is frequently used to embed fusion, which does not allow models to discover the significance of various Transformer representations (e.g., BERT vs. RoBERTa) on a particular aspect. Second, Transformer-based embeddings are unable to encode the relative position of context words to the aspect term, which is a critical semantic feature in detecting which context words affect sentiment. Third, there is an overwhelming majority of attention mechanisms that are flat, and none of them consider hierarchical structures that may interact to jointly model word, aspect, and sentence-level interactions. Lastly, there is the emerging demand to have interpretable ABSA solutions, which means that architectures are not only required to work well but also show what aspects of the text contribute to the sentiment prediction.

Motivated by these challenges, this study proposes a novel ABSA methodology that integrates four key innovations:

- Aspect-aware embedding fusion: Instead of naive concatenation, embeddings from Transformer models (BERT, RoBERTa) are fused using an attention-based fusion mechanism, enabling the model to adaptively weight different sources based on aspect relevance.

- Sequential modeling via BiLSTM: To capture both forward and backward dependencies in text, the aspect-aware fused embeddings are passed through a BiLSTM encoder, enriching the representation with contextual dynamics.

- Hierarchical + Position-aware attention: A multi-level attention block is introduced. Word-level attention highlights aspect-relevant tokens; an optional sentence/aspect aggregation level combines across multiple aspects. Position weighting ensures tokens closer to the aspect term receive higher importance—following inspirations from recent position-aware attention models [10,11].

- Interpretable classification: The final representation feeds into a classification layer with dropout and regularization. The model enables visualization of attention heatmaps (word + aspect level) and examination of positional weights to provide transparency in prediction.

This architecture addresses limitations in previous ABSA work by explicitly modeling aspect-context interactions, using dynamic fusion of embeddings, encoding positional proximity to aspects, and introducing hierarchical structure to attention. We build upon recent advances such as sparse self-attention in ABSA [12] and hierarchical Transformer designs [13], adapting them into an integrated, novel model for aspect-based sentiment.

The contributions of this paper are:

- A hybrid ABSA model with attention-based fusion of Transformer embeddings and explicit aspect embedding, enabling aspect sensitivity in representation.

- The design and implementation of a hierarchical + position-aware attention module, capturing both local (word-level) and hierarchical (aspect-oriented) sentiment cues, with positional bias toward aspect proximity.

- A newly collected, balanced ABSA dataset of 10,000 reviews uniformly labeled across five sentiment classes, addressing limitations of outdated or skewed datasets.

- Extensive evaluation on both the custom dataset and public ABSA benchmarks (e.g., Amazon reviews), showing improvements in accuracy, interpretability, and robustness.

- Detailed interpretability analysis: visualizing attention weights, position weight curves, and aspect-level influence to better understand model decisions.

The primary objective of this research is to develop a robust, novel, and interpretable deep-learning framework for ABSA that addresses three critical gaps: embedding fusion, positional awareness, and hierarchical interpretability. Specifically, this work aims to:

- Design an attention-based fusion mechanism to combine Transformer embeddings (BERT, RoBERTa) with an explicit aspect embedding in a context-sensitive manner.

- Employ BiLSTM to model sequential context forward and backward, enhancing the representation of aspect-aware fused embeddings.

- Build a hierarchical + position-aware attention module that assigns word-level attention conditioned on aspect, aggregates across aspects or sentences, and reweights tokens based on proximity to the aspect.

- Construct and release a new balanced dataset of 10,000 product/service reviews, each labeled across five sentiment classes, to provide a modern benchmark for ABSA research.

- Conduct rigorous experiments on both the new dataset and established benchmark datasets to validate performance, generalization, and interpretability.

- Provide interpretability tools: attention heatmaps, position weight visualization, and aspect-level influence to help users and researchers understand model outputs.

2. Related Work

2.1. Machine-Learning (Traditional) Methods

Machine Learning (ML) is among the most powerful fields of computer science that seeks to replicate the human process of learning on the basis of data experience rather than being written in the form of programming [14]. It allows systems to be automatically improved as they are exposed to increasing amounts of data with time [15]. According to Janiesch et al. [16], ML methods can be divided into shallow (traditional) and deep-learning methods. Shallow or conventional ML has several different paradigms, which are supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised, or reinforcement learning, and each of them is appropriate to the various data availabilities and problem formulations. Naive Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Logistic Regression (LR) are some of the most popular supervised learning algorithms in sentiment analysis due to their simplicity and interpretation [17]. These do so by training on annotated text (data) to classify textual opinions of sentiment, usually using handcrafted features obtained using methods such as Bag-of-Words (BoW) or TF-IDF. Nevertheless, these algorithms have several critical limitations, namely they are task-specific, cannot resolve contextual ambiguity, and need large and labeled datasets to be at their best [18]. Furthermore, conventional ML cannot capture semantic nuances, idiomatic expressions, and contextual dependencies, which are characteristics of natural language. To address these concerns, ensemble models have also been considered in addition to unsupervised models. Saad [19] performed a comparative analysis of sentiment polarity on airline Twitter data from the United States of America, applying six ML models to the data, including Naive Bayes, XGBoost, SVM, Random Forest, Decision Tree, and Logistic Regression, in conjunction with standard preprocessing operations such as stop word removal, stemming, and punctuation filtering. The model used in feature extraction was the BoW model based on 14,640 samples that had three sentiment labels (positive, negative, and neutral) on a Kaggle and CrowdFlower data set. SVM was the most precise, with an accuracy of 83.31%, than the Logistic Regression of 81.81, which confirms the strength of a linear model in the text classification exercise. Similar results have been supported by several other studies. As an example, Tripathy et al. [20] compared SVM, NB, and Random Forest on IMDb and Amazon reviews and stated that SVM performed better than the others, achieving 85% accuracy. Similarly, Kouloumpis et al. [21] established that n-gram features together with syntactic features combined with ML classifiers enhanced the sentiment classifiers of Twitter. Although these achievements are enjoyed, traditional ML models still cannot capture long-range dependencies and implicit sentiment features, especially in multi-aspect or fine-grained sentiment analysis tasks. Recent research in speech emotion recognition has demonstrated the efficacy of the feature-selection methods with one experiment comparing RF, DT, SVM, MLP, and KNN on four benchmark datasets and reaching an accuracy of up to 93.61%, which was higher than handcrafted methods, especially on EMO-DB [22]. A different study proposed a hybrid acoustic model that applies SVM to fused representations with the best speaker-independent performance of 76% on eNTERFACE05 and 59% on BAUM-1s, which outperforms the state-of-the-art performance on semi-natural and spontaneous speech in a fused representation [23]. Thus, machine-learning techniques have been a good source of sentiment analysis studies.

2.2. Deep-Learning Methods

Deep learning has reinvented sentiment analysis, where contextual and semantic representations are extracted automatically, automatically learning the representations of raw text without manually engineering features. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are used to capture long-term dependencies in sequence data [24,25], although early models were able to capture local n-gram features. Such architectures were much more effective at detecting the existence of subtle forms of emotion and opinion than existing machine-learning algorithms. Hybrid CNN-LSTM and BiLSTM-Attention architectures were proposed to focus on the benefits of both spatial and time modeling. As an example, a study by Khan et al. (2022) [26] suggested a CNN-LSTM model to analyze the sentiment in English and Roman Urdu, in which CNN is used to extract local features, and LSTM is used to learn the sequence. Their system was able to achieve an accuracy of up to 90.4% on various corpora, compared to previous models. On the same note, [27] established a benchmark dataset on the Urdu language and evaluated different ML and DL models with either count-based or fastText embeddings. Their results showed that n-gram features using Logistic Regression obtained the highest F1 score (82.05%), which underscored the significance of the quality of representation in low-resource language sentiment analysis. Later works followed this research direction and used mBERT to analyze the sentiment of Urdu in several domains, with a competitive result [28]. Intent detection and further extended to Urdu emotion classification. Transformer-based solutions like BERT are also applied to intent detection, and more recently, a number of ML, DL, stacked attention-based CNN-BiLSTM models and Transformer models are explored with a variety of feature representations. Taken together, these works prove the increasing methodological maturity of sentiment and emotion analysis dealing with the Urdu language [29,30]. Further developments were made by attention mechanisms that enable models to pay attention to words with sentiments in a dynamic manner. The BiLSTM-Attention framework was more interpretable and more effective in identifying key opinion words in the text [31,32]. Newer models like Transformer-based BERT and RoBERTa [8,9] have changed the face of sentiment analysis since they independently hug self-attention to extract a global context without repetition of similar words. Combining these Transformer embeddings with LSTM layers or CNN layers has resulted in even more potent hybrid systems that combine deep contextual information with time sensitivity. In general, deep learning has transformed sentiment analysis to representation-based, adaptive, and interpretable models, which form a solid basis for the emotion and opinion mining systems of the next generation.

2.3. Features Level and Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA) Methods

ABSA is an evolution of the sentiment analysis into a fine-grained one, where it is necessary to understand the sentiment not just on the overall polarity but on particular aspects or features within a review that convey sentiment. This granularity gives the systems the ability to find out what users like or dislike about products or services. The initial period of ABSA depended greatly on the algorithms used in Machine Learning (ML) [33], where systems learn and identify the sentiment without being programmed. Common classical supervised techniques included Naive Bayes (NB) [34], Support Vector Machines (SVM) [35], and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [36], and were applied to ABSA subtasks such as aspect term extraction, aspect category classification, and sentiment polarity detection [37]. A major feature of these models was the use of feature engineering, in which the linguistic features such as n-grams, bag-of-words, POS tags, syntactic patterns, and sentiment lexicons were extracted by humans [38]. These handcrafted features were, however, domain-specific and not scalable, leading to a move to models that would learn with bare data. The concept of Deep-Learning (DL) architectures has changed the face of ABSA, making it less reliant on manual feature design. The first architectures to learn contextual and local dependencies in review text included architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [39] and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [40]. It is worth mentioning that Wang et al. [41] proposed Unified Position-Aware CNN (UP-CNN), which was suitable to process both Aspect Term Sentiment Analysis (ATSA) and Aspect Category Sentiment Analysis (ACSA) tasks. Their model, based on benchmark datasets such as SemEval-2014 (Laptop and Restaurant) [42], MAMS-Term [43], and Twitter [44], proved the significance of adding the aspect position information to the sentiment interpretation. These neural methods represented a big step forward as they would automatically acquire semantic relations between aspect and opinion words, which would improve the robustness and cross-domain generalization. The second advancement came with Transformer-based architecture, especially the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) [45], which added the contextual representation with bidirectional word dependence. The success of BERT further spread to other NLP problems such as question answering, classification, and sentiment analysis, as it allowed deep semantic comprehension via self-attention mechanisms. Its ability to fine-tune made it the most suitable for the ABSA, such that the model could match aspect terms and opinion expressions of relevance. Simultaneously, GPT models (GPT-1, GPT-2 [46], and GPT-3 [47]) extended the generative aspect of sentiment analysis. Large language models (LLMs) like GPT and ChatGPT also enhanced the contextual understanding with possible results of zero-shot and few-shot ABSA problems. Nonetheless, as Chumakov et al. [48] observed, the study of the GPT-driven models of subtasks such as Aspect-Sentiment Triplet Extraction (ASTE) is in its infancy, which is a new direction in the research of ABSA. A very related dimension of ABSA is feature-level sentiment analysis, which aims at defining explicit product or service features as battery life or camera quality, and correlating them with sentiment polarity. This degree of granularity gives actionable information, especially with commercial use and recommendation systems. Recent models started to combine syntactic dependency parsing and hierarchical attention, as well as aspect opinion alignment systems, to enhance feature sentiment coupling. Transformer-based architectures, including BERT-PT [49], Unified Generative Frameworks [50], and more recent hybrid systems using contextual encoders along with attention and gating mechanisms [51], have helped dramatically towards improving interpretability and accuracy. Altogether, these developments present an evident direction in the literature of the replacement of manual, feature-engineered ML frameworks by highly contextual, adaptive Transformer frameworks that can emphasize complex, many-level sentiment dependencies with respect to aspects, features, and expressions.

2.4. Attention and Hierarchical Attention Mechanism

Advancement of the attention mechanisms has seen important improvement in the sentiment analysis process, as there is no longer the need to stick to simple attention models and instead, consider hierarchical and multi-level attention. Mechanisms such as word, sentence, and aspect level allow models to target the most informative areas of text, making them interpretable and more accurate. Models such as HAN, HATN, ATAE-LSTM, and IAN have played an important role in capturing layered semantic and contextual dependencies, which can be used to understand sentiment decisions in a more sensible fashion. Attention-based architectures are especially useful in aspect-level sentiment classification. The attention-based LSTM model [32] is an effective model that captures fine-grained opinions, and it has been shown to yield a great deal of results on the SemEval-2014 dataset. It is built on this, where the BATAE-GRU model [52] incorporates the BERT embeddings, RNNs, and attention to reinforce aspect-context links, outperforming ATAE-LSTM by up to 9.9% accuracy. The models demonstrate the development of the attention processes into context weighting to deep contextual reasoning in order to interpret the sentiment more accurately. In addition to the sentiment of text, Hierarchical Attention Networks (HAN) have been shown to be successful in other, more complex tasks such as sequential recommendation and video understanding by learning both temporal and semantic dependencies across multiple levels [53,54]. Their ability to combine fine-grained information has inspired sentiment models like HATN and IAN that combine to utilize hierarchical relations between aspects and sentences [55,56]. Taken collectively, these developments represent a turn toward interpretable, multi-layered structures of attention that integrate contextual, hierarchical, and aspect-level knowledge, which form a strong basis of contemporary sentiment analysis.

2.5. Transformer-Based Models

Sentiment and ABSA have been revolutionized through the creation of Transformer-based models that incorporate contextual embeddings and transfer learning, and enable models to learn deep semantic text relationships. Early Transformer architecture models such as BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, and XLNet show improved performance over traditional deep-learning strategies, and they use self-attention and bidirectional context modeling. These models are also good at capturing subtle sentiment indicators, context-driven dependencies, and opinion-specific aspects, and are a new standard on sentiment analysis tasks. These application-specific architectures have been optimized in recent developments. Multi-Grained Attention Network (T-MGAN) is a combination of Transformer and Tree Transformer that is trained together to learn syntactic and contextual outputs between aspects and opinions. It is an effective finer-grained sentiment cue capturing method with a multi-grained attention and dual-pooling mechanism, which has demonstrated better performance on several benchmark datasets [57]. The development of the sentiment analysis methods was thoroughly reviewed, including both classical word embeddings, machine-learning ones, contextual embeddings, and more advanced Transformer-based models (GPT, BERT, and T5). The article is a critical comparison of the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each technique, and the description of the main current research trends and challenges. This summary provides the scientists with a definite idea of the modern developments and the future perspectives of the SA discipline [58]. On the same note, BERT Adversarial Training (BAT) model boosts the robustness in ABSA by embedding adversarial training in the embedding space and outperforms general and post-trained BERT variants and represents a significant improvement in robust training of transformers [59]. RoBERTa-derived methods have also shown even higher precision with a maximum 92.35% accuracy on SemEval restaurant reviews and 82.33% on the laptop domains, thus establishing RoBERTa as a state-of-the-art Transformer in aspect-level sentiment tasks [60]. Hybrid Transformer architectures build on the progress made earlier by integrating contextual representations with auxiliary models to gain more insight into emotions. RAMHA (RoBERTa with Adapter-based Mental Health Analyzer) is a machine combining RoBERTa, adapter layers, BiLSTM, attention, and focal loss in classifying text on social media on GoEmotions datasets, attaining up to 92% accuracy, outperforming eight baselines [61]. Other than these, ABSA ALBERT parameter-sharing mechanism can be more efficient at fine-tuning on large review collections [62], and T5 reinvents sentiment and aspect extraction as a text-to-text generation, which improves extrapolation to unseen areas [63]. Furthermore, XLNet, with its language modeling that uses permutations, offers more detailed bidirectional context to aspect-sentiment prediction [64]. Coupled with these Transformer-based architectures, these contextual embeddings and transfer learning highlight the revolutionary impact of contextual embeddings and transfer learning in producing interpretable, scalable, and high-performing sentiment and aspect-based systems of analysis.

2.6. Explainable and Interpretable Models

The implementation of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in sentiment analysis has gained importance in improving the accuracy of transparency, and accountability of Transformer-based models. Recent research gives the results of fine-tuned BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT, and XLNet models in ABSA tasks, and explainability systems such as LIME, SHAP, Integrated Gradients, and Grad-CAM show what linguistic features are used to trigger model actions. The researchers showed a max. 97.62% accuracy with the help of SemEval, Naver, and MAMS, and showed that interpretability creates a direct contribution to the improvement of robustness and model reliability on smaller-scale sentiment tasks [65].

On the same note, the TRABSA (Transformer and Attention-based BiLSTM for Sentiment Analysis) framework combines RoBERTa with BiLSTM and attention mechanisms to enhance the classification accuracy and interpretability. SHAP-based traba visualizations can be used to interpret token-wise sentiment attribution, and on multilingual tweet data, they have 94% accuracy. Its more explainable architecture increases not only predictive precision, but also has utility in practical uses of deep learning to decision support, e.g., pandemic control and policy optimization, which explains the use of interpretable deep learning in socially important projects [66]. Besides that, a layer-wise SHAP decomposition model disaggregates Large Language Models (LLMs), including their embedding, encoder, and attention layers, to provide fine-grained interpretability. This framework elucidates the spread of sentiment cues through layers using the Stanford Sentiment Treebank (SST-2) and is more readable and reliable compared to model-level interpretability frameworks in holistic models [67]. In a complementary manner, a hybrid interpretability framework based on ResNet heatmaps and 2D Transformer saliency maps shows how multimodal explanations can be used to provide spatial-temporal coherence in tasks of sentiment and industrial prediction, with an accuracy of 94.1% and domain-specific visual narrative [68]. The following Table 1 summarizes the related work.

Table 1.

Summary of Sentiment Analysis and ABSA Studies.

3. Materials and Methods

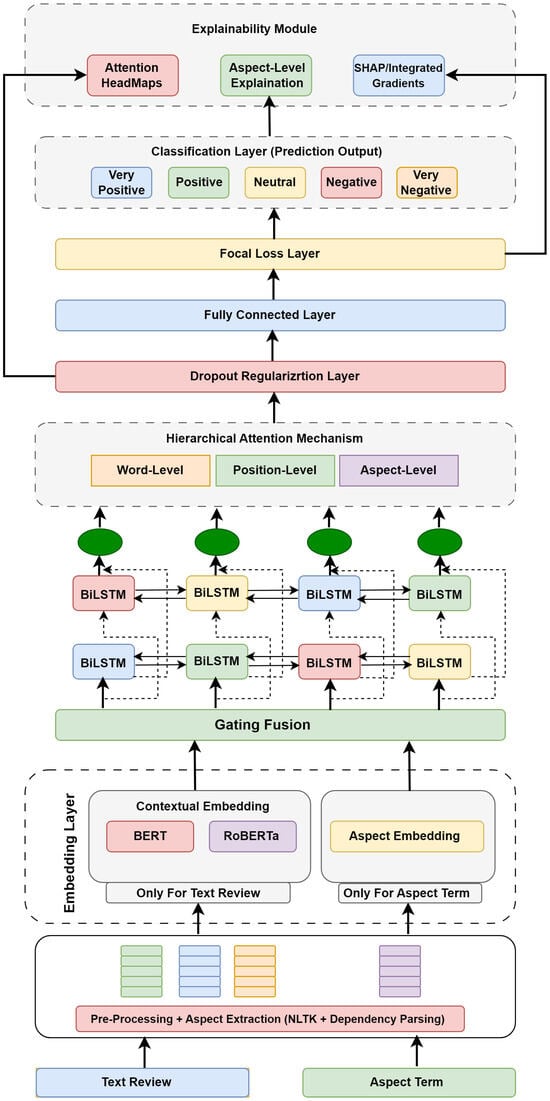

Our proposed model introduces an aspect-aware, fusion-based pipeline for fine-grained sentiment classification. Every step of the methodology is thoroughly developed to resolve current weaknesses of sentiment analysis without sacrificing predictive power and interpretability. Our architecture is an aspect-based, fusion-based architecture of fine-grained Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA). The model takes two inputs, a review text and an aspect term, and gives a five-way sentiment prediction (1–5). Key novelties: (i) dynamic, gated combination of multiple PLM embeddings (BERT + RoBERTa) with explicit aspect embeddings, (ii) BiLSTM sequential modeling on fused representations, (iii) a single aspect-sensitive, position-sensitive attention to provide efficient, interpretable aggregation, and (iv) integrated explainability (attention heatmaps + SHAP/Integrated Gradients) with quantitative evaluation of the explanations. Now, Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of the Proposed Hybrid Attention-based Model (HAM) architecture, which combines Transformer encoders (BERT/RoBERTa), BiLSTM, and GAT to integrate contextual, sequential, and aspect-based feature fusion. This model uses an attention-based fusion mechanism, Focal Loss produced classification, and a multi-stage explainability module ( Attention Heatmaps, Aspect Interpretation, SHAP/Integrated Gradients) to produce interpretable and robust sentiment prediction on a variety of diverse datasets, and Algorithm 1 also describes the steps of our proposed model.

| Algorithm 1 HAM-X—Hybrid Attention-based Model with Explainability Layer |

|

Figure 1.

Proposed Hybrid Attention-based Model (HAM) architecture, implementing Transformer, BiLSTM, and GAT representations with adaptive attention fusion and a combined explainability module to make accurate and interpretable sentiment prediction.

3.1. Input Layer

The model takes two kinds of inputs; one of them is the review text, which contains the sentiment-bearing content, and the other one is the aspect term, which determines the point of analysis. This format is a two-input structure that is essential to Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA), which makes sure that no predictions are made on the entire review but on the aspect itself.

We start with a review text R and the corresponding aspect A.

3.2. Preprocessing and Tokenization

Raw review text and aspect terms are initially normalized with the removal of noise (punctuation, case sensitivity errors, and unnecessary spaces) and later tokenized with BERT and RoBERTa subword tokenizers. This will be done to ensure that it is compatible with existing contextual encoders and that semantic and syntactic data are retained to support aspect-sensitive representation. PLM tokenizers (WordPiece/BPE) generate subword tokens that are compatible with BERT/RoBERTa and allow the computation of spans that are correct to position them.

Map aspect tokens to token span indices

3.3. Aspect Extraction

Aspects are mined in a hybrid fashion that integrates both rule-based linguistic techniques with dependence-based heuristics. This step is necessary to guarantee that the terms of aspects that were relevant (e.g., product features or service attributes) are clearly defined. The model aims to isolate the aspects of the entire review text in favor of the fine-grained opinion targets instead of having to use only coarse-grained sentiment indications. This layer selects aspect (A) and its token span. Correct span detection makes position-related attention and aspect pooling correct.

3.4. Token and Position Embeddings

After the review tokens and aspect tokens are received, all tokens are projected to a dense space of vectors with pretrained contextual encoders. Specifically, is a sequence of tokens, each of which is converted to a contextual embedding using BERT and RoBERTa. In the same way, the aspect sequence is expressed as aspect embeddings . Positional embeddings are introduced in order to save word order information. After the Transformer formulation, the embedding of the input of the ith review token is defined as:

is the embedding of the contextual token and is the embedding of sequential order. Likewise, position-aware embeddings are added to aspect tokens

The embedding scheme guarantees that the model learns the semantic meaning of the token and their relative position with regard to the aspect, which is imperative in ABSA. The model is sensitive to what and where is said in the review by being an integration of position encodings and contextual embeddings.

3.5. Linear Projection

In order to have compatibility between contextual embeddings and aspect embeddings, we use a linear projection layer that transforms each of the representations to one common latent space of dimension d. Review embeddings with BERT and RoBERTa:

and to the aspect of aggregation adding.

In this case, are learnable projection matrices and b terms are bias vectors. This forecast is such that:

- It is assumed that all embeddings are in the same semantic space of dimension d.

- The representations are then comparable directly and can be successfully fused in the next Gated Fusion Layer.

- All unnecessary differences between models BERT vs RoBERTa are averaged, and complementary features are kept.

Therefore, a linear projection serves as a semantic alignment proxy, which progresses the embeddings towards adaptive combination in the gated fusion process.

3.6. Gated Fusion Layer

BERT and RoBERTa are complementary in offering contextual representations, but when they are simply concatenated, their results usually include redundancy and suboptimal integration. We propose solving this issue with a Gated Fusion Layer that actively regulates the input of each embedding stream (BERT, RoBERTa, and Aspect) through learning task-specific gating parameters. Formally, assume that the linearly projected embeddings are.

A gating mechanism is used to dynamically down-weight the significance of BERT and RoBERTa embeddings at each token position:

And where are trainable parameters, is concatenation, and is the sigmoid function.

The fused representation is then calculated as:

and lastly trained in the aspect embedding by:

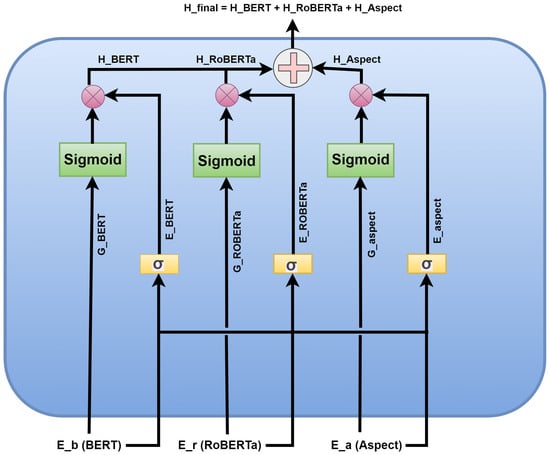

where is defined as element-wise multiplication and is defined as concatenation of vectors. Here are some key features of Gated Fusion. Now Figure 2 illustrates the Gated Fusion Model, where the Gated Fusion Module shows how to integratively introduce Transformer-based embeddings (e.g., BERT and RoBERTa) and explicit aspect embeddings. Contributions of each source are balanced dynamically by the gating layer by means of element-wise gating and attention weighting to ensure aspect-aware semantic representations are context-sensitive, robust, and optimally fused before sequence modeling.

Figure 2.

Gated Fusion Module with Transformer and aspect embeddings based on dynamic element-wise gating and aspect attention weighting to create semantic representations that are robust, aspect-aware, and sensitive to attention.

- Adaptive weighting: The model is trained to apply BERT or RoBERTa features based on the token and context.

- Aspect-conscious integration: The fusion is still biased towards the opinion target but not generic sentiment by incorporating the aspect embedding in the gating function.

- Redundancy minimization: Gating filters rather than concatenating both embeddings results in redundancy minimization.

- Interpretability: Gating scores are visualizable to learn which model had a more significant impact on a decision of a particular token.

In this way, the Gated Fusion Layer is the semantic integration point, ensuring that the heterogenous embeddings are combined into one, aspect-sensitive representation, which is then sent to the downstream BiLSTM + Attention layer to reason sequentially.

3.7. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)

Following gated fusion, aspect-aware embeddings are then fed into a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network to capture sequential interaction and syntax in the review text. In contrast to conventional RNNs, LSTMs have gating mechanisms, which reduce vanishing gradients, allowing them to learn long-term contextual dependencies. The two-way variant also implies that the past (left context) and future (right context) information were coded at the same time. In the abstract, provided the fused input sequence:

The forward and backward LSTMs calculate hidden states as:

In which represents the encoding of information starting at the start until token i, and represents the encoding of information starting at the end, all the way back to token i.

The two-directional hidden states are combined to obtain the BiLSTM representation at that time step.

In this way, the BiLSTM generates the sequence of outputs.

The importance of BiLSTM in ABSA.

- Sequential reasoning: Reasoning between opinion words at different distances, for example “not good”.

- Aspect alignment: The model captures the aspect-conditioned sentiment by learning a contextual flow around the aspect that involves the aspect preceding context and the aspect succeeding context.

- Complementary to transformers: Transformers are more effective at contextualizing on a global scale, whereas BiLSTM strengthens local, position-sensitive dependencies, which prove particularly useful in aspect-based tasks.

The structure of the architecture is based on a combination of deep contextual embeddings (BERT, RoBERTa) and sequential structure modeling (BiLSTM) to provide semantic richness and contextual accuracy to support strong sentiment classification.

3.8. Hierarchical Attention Mechanism (HAM)

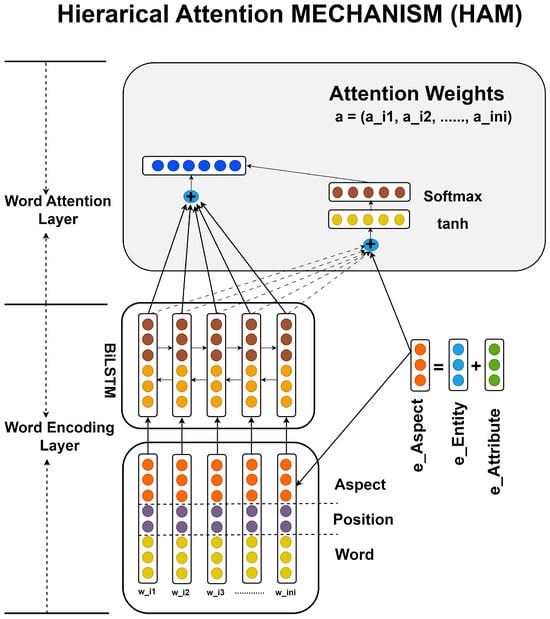

The proposed model uses a HAM module to overcome the necessity of refining the BiLSTM outputs and allowing the aspect-based focus. In comparison to traditional single-layer attention, HAM incorporates three complementary views: word-level, position-level, and aspect-level attention, such that the sentiment decision does not simply rely on the token semantics but also the location of words and their connection to the target aspect. Therefore, here, Figure 3 illustrates the Multi-level Attention Process HAM module, where word-level attention brings out aspect-relevant tokens, and sentence-level attention combines these representations into aspect-specific contextual vectors. Position-conscious weighting is an additional refinement of attention that gives higher emphasis on tokens that are close to the aspect term, which maximizes interpretability and sentiment discrimination.

Figure 3.

Multi-level attention process represented by the Hierarchical Attention Mechanism (HAM) module, which shows word-level and sentence-level attention with position-sensitive weighting to give stress on aspect-relevant tokens and create interpretable, aspect-specific contextual representations.

3.8.1. Word-Level Attention

At this stage, the model allocates the weight of importance to each contextual hidden state of the BiLSTM, where examples of our sentiment-bearing words are given, and excellent, poor, and irrelevant tokens are suppressed.

where is a trainable projection matrix and is a word-level context vector. The summary representation is:

This makes sure that semantic salience is saved from the sequence of reviews.

3.8.2. Position-Level Attention

The significance of words is not enough in ABSA, because in many cases, the sentiment polarity is determined by the relative closeness to the aspect. The position-level attention, therefore, brings in distance-conscious weighting, where the tokens nearer to the aspect have more weight. At position (i) and aspect centered at position (j):

Then, a normalized position attention score is used:

and the position-sensitive representation is:

This level makes sure that the model puts tokens in close proximity to the aspect (e.g., in, “The camera quality of this phone is outstanding,” the phrase “outstanding” must be more closely associated with “camera” than with words far away).

3.8.3. Aspect-Level Attention

The last attention layer is used to align review tokens with the specific aspect representation to yield aspect-conditioned sentiment.

The Aggregated aspect-aware context vector is then:

This is so as to ensure that the sentiment is directly conditioned on the target aspect, without misclassification due to irrelevant aspects in multi-aspect reviews.

3.8.4. Final Hierarchical Attention Representation

The three-level outputs are added together to obtain the hierarchical context vector:

Now here and are trainable parameters

3.9. Final Classification and Optimization

Once the hierarchical context representation has been obtained by the Hierarchical Attention Mechanism, the model goes to the final sentiment prediction step. This step converts the multi-level representation, which is very rich, to a discrete sentiment label using a fully connected projection and a probabilistic classification layer.

3.9.1. Linear Projection and Softmax Classification

The resultant attention-derived feature is concatenated and then subjected to a linear layer transformation that projects it into a subspace specific to the sentiment. This transformation captures the high-level abstractions in the word, position, and aspect-level attention.

where and are the output weight matrix and bias vector, respectively. Logits z are then normalized by the SoftMax function to generate a probability distribution of the sentiment classes.

In this case, C refers to the total amount of sentiment categories (e.g., 5 of fine-grained sentiment: very negative, negative, neutral, positive, and very positive). The probability of the most likely class is chosen as the predicted sentiment.

3.9.2. Regularization and Focal Loss Optimization

To reduce overfitting and increase generalization, dropout is regularized before classification. The dropout randomly kills neurons in training, making it resistant to noise, and it is not dependent on particular features. Since the example of the sentiment datasets usually has an imbalance in classes, such as more neutral reviews than extremely positive or negative ones, the model uses Focal Loss, rather than the conventional cross-entropy. Focal Loss is a dynamic weight, or scaling, loss that learns to place more emphasis on the learning of the harder, misclassified samples. It is defined as

where

- is the weighting factor for class ,

- is the focusing parameter controlling difficulty emphasis,

- is the predicted probability for the true class.

This adaptive loss promotes equal learning among the categories of sentiment and guarantees better performance on underrepresented labels.

3.9.3. Training Strategy

The Adam optimizer is applied with a learning rate to optimize the AGF-HAM model parameters, and with the help of adaptive moment estimation, it should converge steadily. Early stopping is used to avoid overtraining, with the basis of validation loss. The total training goal reduces the amount of focal loss of all samples:

In this step, the learned hierarchical and gated representations are incorporated into a small, interpretable, and accurate sentiment prediction that is both accurate and interpretable.

3.10. Explainability Module

An Explainability Module Layer is incorporated as the last step of the HAM framework in order to guarantee interpretability and transparency of the final model predictions. The layer makes the process of forming the sentiments’ decisions globally and locally interpretable by showing how the model forms its conclusion based on linguistic and contextual knowledge. The explainability module is based on three complementary sub-layers—Attention Heatmaps, Aspect-Level Explanations, and SHAP Integrated Gradients—that have a specific analytical purpose to hold models accountable and explainable to humans.

3.10.1. Attention Headmaps

The Attention Headmaps sub-layer shows token-level scores of the importance of the attention heads in the Transformer encoder and BiLSTM layers. It puts emphasis on particular words, phrases, or clauses that have a strong impact on the sentiment or emotional polarity of a certain text. This visualization, in addition to showing the focus distribution of the model, also proves the interpretive reliability of the attention mechanism. With the help of these heatmaps, researchers and practitioners can confirm that the model focuses on semantically significant areas and not accidental associations.

This calculates the attention weight of each token t, and this is the degree to which that token is relevant to the query (aspect or sentence context). It involves a SoftMax normalization such that all weights of attention have a sum of 1.

This maps the attention weight to the underlying token, which compose the raw headmap of token importance in the text. It graphically shows the words that make the greatest contribution to sentiment decisions.

The weights between the attention and the visualization of the headmap are normalized to 0 or 1 to form a visual representation of the headmap. It guarantees a similar visualization of samples to make them easier to interpret.

3.10.2. Aspect-Level Explanation

The sub-layer of Aspect-Level Explanation gives a fine-grained interpretability, where sentiment weights are mapped to the identified aspects in the text. This sub-layer explains the roles of each product or emotional aspect in the final sentiment classification using dependency-based aspect extraction and context embeddings. It can be used to provide transparency in aspect-aware decision-making and bridge the semantic connection between aspect terms (battery, camera, service) and the contextual sentiments. This sub-layer is specifically useful when the task at hand demands domain interpretability, like reviewing or detecting emotions in social situations.

This computes aspect-conditioned attention, in which is the embedding of a given aspect (e.g., “battery” or “service”) It helps the model to pay attention to the most relevant words to that aspect.

In this case, the hidden states are used to create a weighted context vector, which is a mixture of the hidden states with aspect-specific attention weights. It is a compressed feeling indicator of that specific element.

This is to apply sentiment polarity prediction as an aspect a with all classes using a softmax layer. It produces probabilities of the form of positive, neutral, or negative sentiment.

This is used to select the most influential tokens that assist in sentiment on aspect a. These tokens are used to produce aspect-level textual explanations.

3.10.3. SHAP/Integrated Gradients

The SHAP Integrated Gradients sub-layer is a combination of SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) with Integrated Gradients (IG) used to measure the contribution of each feature to the output of a model. This hybrid interpretability method combines model sensitivity and feature attribution consistency into unified importance maps that are complementary to the attention-based interpretations. This sub-layer is a combination of SHAP and IG and is able to provide a coherent and consistent explanation of decision boundaries, which strengthens the transparency and reliability of the model.

This is the Shapley value equation, which is used to measure the contribution of a given feature to the prediction of the model. It assesses the effect of the addition of a feature (word/token) on model output on all the subsets.

SHAP values can be summed up to form the difference between baseline and model prediction. This guarantees additive attribution of features, which ensures consistency of interpretability.

Integrated Gradients calculate the contribution of each input feature to the output of a model by summing the gradients between the path taken between a baseline and the real input x. It offers path-sensitive interpretability that is smooth and has less noise than raw gradients.

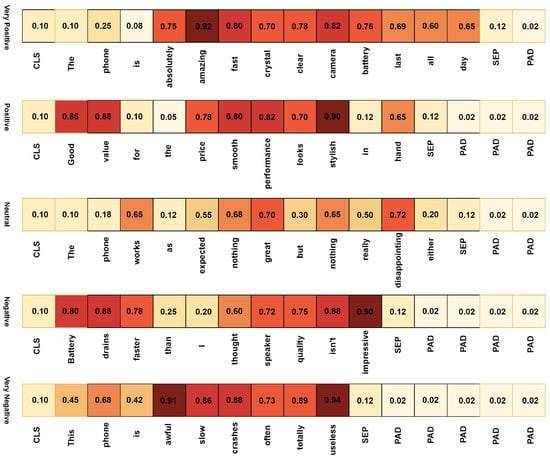

To illustrate the interpretability of the proposed explainability module, we provide examples of each of the sentiment categories: very positive, positive, neutral, negative, and very negative. A heatmap visualization in Figure 4 is provided per sentence to show the distribution of the attention weights of the individual tokens, i.e., the focus of the model when inferring the sentiment. The darker the region of the heatmap, the greater the intensity of attention of the token is, and the greater its influence on the final prediction of the model will be.

Figure 4.

Heatmap visualization showing token-level attention distribution for sentences across five sentiment categories. Darker shades represent higher attention weights to the model’s sentiment prediction.

Aspect-Level Summary:

- Detected Aspect: phone/performance

- Opinion Tokens: awful, slow, crashes, useless

- Aspect-Sentiment Score:

- Aspect Polarity Label: Very Negative

Final Interpretation:

The model classifies this sentence as Very Negative. Attention, Aspect-level Polarity, and SHAP/IG all emphasize the same tokens: awful, useless, and crashes—indicating they are the strongest contributors to the negative sentiment toward the phone’s performance.

Besides visual interpretation, there is also elaborate explainability of one representative sentence in Table 2 and Table 3. The table is a quantitative report on the attention weight, aspect-level polarity, SHAP value, and Integrated Gradient (IG) contribution of each token. These three measures are then normalized and averaged to obtain the combined importance score to reflect the contextual and causal influence on the decision of the model. This integrated analysis would allow not only the explainability framework to identify words that carry sentiment (e.g., awful, useless, excellent) but also clarify their relationship with certain aspects in context, allowing the transparent and understandable interpretation of how the model reaches its classification.

Table 2.

Explainability Table for Sentence: “This phone is awful slow crashes often today useless”.

Table 3.

Definition and Formula of Each Explainability Metric.

The combination of these three sub-layers gives HAM not only superior performance in predictive mode but also a high level of interpretive ability. This Explainability Module Layer converts the HAM framework to more of an intelligent system that can be trusted and interpreted by humans, having the ability to provide the answer to why and how decisions are made through complex sentiment and emotional environments.

4. Dataset Description and Hypermeters

Three datasets were used to determine the effectiveness of the proposed AGF-HAM framework, its robustness, and its generalization ability; two publicly available benchmark corpora and one custom-made dataset were used. This multi-dataset approach guarantees thorough validation on domain-specific, product-driven, and emotion-driven settings, with internal and external experimental validity.

4.1. Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews

The source of the Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews dataset is a reputable source, Kaggle, and the corpus is publicly available on (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/grikomsn/amazon-cell-phones-reviews?select=20191226-reviews.csv, accessed on 2 December 2025) and widely used in sentiment analysis research. It consists of 67,986 customer reviews and has eight formatted attributes: ASIN, product name, rating, review date, verification status, review title, review body, and helpful votes. Each review is rated on a five-point scale (1–5), which directly translates to sentiment polarity categories of very negative, negative, neutral, positive, and very positive. The data set offers an equal and domain-specific benchmark that reasonably captures consumer opinion, buying patterns, and sentiment subtleties regarding cell phones and electronic accessories. It is especially well-suited to the aspect-based and Transformer-based sentiment models because it is structured and has a large sample size.

4.2. GoEmotions (5-Class Variant)

The GoEmotions dataset is publicly available on kaggle.com (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/debarshichanda/goemotions, accessed on 2 December 2025), which is a fine-grained emotion classification benchmark that was created by Google. It includes three sub-versions: GoEmotions1 (70,000 samples), GoEmotions2 (70,000 samples), and GoEmotions3 (70,226 samples) that together offer more than 210,000 labeled examples. A text instance is marked with one or more of 28 different categories of emotions that describe the full spectrum of expressions of feelings. The dataset can be used to perform single-label and multi-label emotion recognition tasks, but is especially useful in testing models on subtle emotional perception. Its scale, language diversity, and fine-grained annotations are a perfect addition to sentiment-oriented datasets that provide a deeper level of emotion to test the overall validity and strength of the suggested AGF-HAM framework.

In order to provide methodological consistency and provide a fair comparative analysis between datasets with varying degrees of emotional granularity, the original 28 fine-grained emotion labels in the GoEmotions dataset were mapped in Table 4 systematically into five sentiment-oriented categories, namely Very Positive, Positive, Neutral, Negative, and Very Negative. Such a hierarchical feeling category corresponds to the five-class sentiment category of the Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews dataset, which is consistent in evaluation metrics across domains. The aggregation does not remove the semantic variety and emotionality of the social media expression and offers a comparative benchmarking framework. Therefore, this mapping helps to make the performance evaluation of datasets with differences in their domain focus on social media discourse, as well as emotional expressiveness and linguistic variability fair.

Table 4.

Mapping of GoEmotions Fine-Grained Labels into Five Sentiment-Oriented Classes.

4.3. Summary of Datasets

Table 5 summarizes the key characteristics of all datasets used in this study.

Table 5.

Summary of Datasets Used in AGF-HAM Evaluation.

The combination of these three datasets, Table 5 ensures that the AGF-HAM model is evaluated on multiple linguistic domains—technical, commercial, and social—capturing a broad spectrum of sentiment expressions. This diverse evaluation framework not only validates the model’s effectiveness but also demonstrates its robustness and adaptability in handling domain-specific and cross-domain sentiment variations.

4.4. HyperMeters

The AGF-HAM model has various hyperparameters and optimized parameters to provide balanced learning, robust convergence, and a high ability to generalize them across datasets. All the model parts were optimized by systematic experimentation along grid and random search algorithms. The Transformer backbones (BERT and RoBERTa) were pretrained, and they were fine-tuned together with task-specific layers. Learning was stabilized by the use of Adam optimizer with an adaptive learning rate schedule, and regularization was carried out by dropout. The empirical choice of batch size, sequence length, and representational depth was through hidden dimensions and sequence length. Validation loss was used to avoid overfitting by early termination. Table 6 summarizes the optimal configuration used in all experiments.

Table 6.

Hyperparameter Configuration for AGF-HAM Model.

The balance in expressive capacity and training stability is represented in the above configuration. A learning rate of and a batch size of 32 were identified as being optimal in staying constant with Transformer backbones. The moderate dropout rate of 0.3 served as a good counter to overfitting without using model capacity in an underutilized way. The focal loss parameters were used to deal with the imbalance of the classes, where each sentiment category would make fair contributions. A hierarchical attention head of 8 and a BiLSTM hidden size of 256 was rich enough in its representational capability to capture the word, position, and aspect dependencies. Premature termination also helped in training efficiency and strong generalization between datasets.

To achieve consistency in the baselines of all comparisons, all the baseline models (recent Transformer-only architecture and hybrid Transformer-BiLSTM models) were fine-tuned under the same experimental conditions. The training regimen, optimization scheme, and preprocessing procedures were applied consistently to all models. All the hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, optimizer, dropout, hidden dimensions, focal loss parameters, early stopping rule, etc.) will be compiled to Table 6, so that these will be completely reproducible. The resulting single configuration makes a sound performance comparison possible and isolates the actual contribution of each architectural component of the proposed model.

5. Experiments and Results Discussions

Comparison of the performance of the baseline models within the four datasets is summarized in Table 7. The conventional machine-learning algorithm SVM had an average score of about 76–78% across GoEmotions variants and 80.1% on the Amazon data, but was marginally less effective than Logistic Regression (LR), which had a score of about 77–79%. Naive Bayes (NB) had the relatively poorer performance with an accuracy level of 74–75. The shift to deep-learning models, LSTM, RCNN, GRU, and Bi-GRU, showed some performance improvements with an accuracy ranging between 81 and 85%; as they have the capacity to discover contextual dependencies and sequential characteristics in a better manner than the old models. It is interesting to note that Bi-GRU obtained the best accuracy between the recurrent architectures, with 84.2–85.4% on the GoEmotions datasets and 86.9% on the Amazon dataset.

Table 7.

Performance Comparison of Baseline Models across Datasets.

In addition, the Transformer-based BERT model showed a significant improvement in the performance with 88.4, 89.1, and 89.9 accuracy with the three versions of GoEmotions, and 91.3 accuracy with the Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews dataset. It shows that BERT is greatly contextually sensitive and has a powerful ability of pretrained linguistic representation, which allows it to outperform classical and recurrent models. In general, although the trends of all models were similar to improve the performance with the Amazon data, this could be explained by the fact that the latter is more organized and focused on sentiments than the multi-emotional variability of GoEmotions.

Comparative analysis that was conducted with the Transformer-based and the hybrid architectures, as illustrated in Table 8, indicates that there was a massive performance enhancement in comparison to the traditional and recurrent baselines. BERT, a typical Transformer model, had an accuracy of 88–89% with the variants of GoEmotions and 91.3% on the Amazon dataset, indicating a good understanding of the context. ALBERT and XLNet exhibited slightly better results, reaching approximately 89–91% accuracy, which was made possible by the sharing of parameters and permutation-based attention mechanisms, respectively. RoBERTa, through its good pretraining optimization, had better results compared to other baseline transformers, reaching 91.9 and 93.1 on GoEmotions-3 and the Amazon reviews, respectively.

Table 8.

Performance Comparison of Transformer-Based and Hybrid Models.

The addition of sequential layers was another way of adding depth to the representation. RoBERTa+BiLSTM hybrid obtained 91.7–93.0% of the accuracy in GoEmotions and 94.0% in Amazon, and DistilBERT+Attention reached the same efficiency with a minor decrease in computational complexity. These findings highlight the usefulness of using a combination of contextual embeddings and sequence learning, and attention refining. It is important to note that the HAM model (Hybrid Attention Mechanism) had the highest overall performance, showing a 94.5, 95.1, and 95.6% accuracy on GoEmotions variants and a 96.4% accuracy on the Amazon dataset, and higher precision, recall, and F1 scores of over 93%. This illustrates the ability of HAM to focus the fine-grained emotional and sentiment representations by the interaction of high-order Transformer representations and the BiLSTM.

5.1. Ablation Study

An ablation analysis was performed on both GoEmotions-3 and Amazon Cell Phones data to determine the role of each architectural component, as shown in Table 3. As a starting point, the RoBERTa baseline recorded an accuracy of 91.9 on GoEmotions and 93.1 on Amazon, which is a good contextual base. BiLSTM addition increased the performance by around 1–1.5, which suggests that sequential bidirectional encoding is an effective supplement to the Transformer based on its static contextual embeddings because it captures the temporal relationships and polarity flow in longer reviews.

The incorporation of an attention mechanism also increased the accuracy to 94.3% and 95.2%, thus demonstrating the relevance of weighted feature emphasis in detecting sentiment-varying tokens and aspect-specific features. Another improvement from 0.76% to 0.85% was achieved when using Focal Loss, which meant that the imbalance in classes was overcome and the model’s sensitivity to the sentiment categories of minorities was improved. Lastly, the HAM configuration with RoBERTa, BiLSTM, hierarchical attention, and adaptive optimization had the best performance with 95.6 on GoEmotions and 96.4 on Amazon.

The results of the ablation (Table 9) indicate clearly the incremental contribution of each element in the proposed architecture of HAM. BiLSTM enhancement of RoBERTa sequence modeling and attention, which adds greater value to aspect-sensitive feature weighting. An addition of the focal loss can help in terms of class imbalance, and the complete HAM in terms of fusing the fusion gate with GAT and position-aware attention shows the best results in the accuracy of both datasets. Such accumulating gains justify the need and usefulness of every module.

Table 9.

Ablation study on the proposed HAM Model (GoEmotions-3 and Amazon Datasets).

These results highlight that all elements play a significant role: RoBERTa brings out the depth of the context, BiLSTM brings out the sequential comprehension, Attention brings out the interpretability and weighting of tokens, and Focal Loss reduces the bias caused by imbalance. The strength and complementary quality of the hybrid design are justified by the incremental benefits that it has brought in the process of predicting sentiment, which proves that the HAM framework is capable of successfully integrating global and local semantic information to make better predictions.

In addition to the quantitative performance, interpretability analysis with the help of LIME and SHAP also supports the results of the ablation study. The analysis of the token-weighted attention and contribution showed that all structural modifications made in HAM directly increase the explainability and transparency of decisions made by the model. Due to hierarchical attention integration, as an example, the model can emphasize aspect-relevant words (e.g., battery life, camera quality) and deemphasize non-informative tokens to generate more human-congruent reasoning patterns. Likewise, Focal Loss not only enhances the precision of the underrepresented sentiment classes but also stabilizes the heatmaps of attention-ensuring that attention is consistently concentrated in varied samples.

In comparative XAI visualizations, it is evident that RoBERTa and RoBERTa+BiLSTM are relatively useful in general sentiment polarity but are prone to misunderstanding the context of compound sentences or sarcasm. Conversely, the HAM framework offers more aspect-sensitive explanations that are more interpretable with a high fidelity of interpretation, all of which proves that every model improvement would lead not only to numerical improvements but also to qualitative knowledge. The given hybrid design is, therefore, the solution to two tasks: state-of-the-art performance and open decision-making, which is needed in the real-life application of sentiment and emotion analysis.

5.2. Comparative Study

The relative analysis of the previous works highlights the ongoing innovations in sentiment and emotion classification techniques. According to Table 10, during the preliminary stage, Studies [1,3] used BERT with Contextualized Psychological Dimensions (CPD) on the GoEmotions dataset with F1-scores of 51.96% and 52.34%, respectively, reflecting the fact that it has 28 fine-grained emotion categories that are difficult to process. Likewise, Study [2], which used baseline BERT on the same dataset, reached a similar F1-score of 52%, justifying the need to investigate deeper contextual learning processes. In pursuit of better representation learning, Study [4] proposed Seq2Emo on a fused SemEval-18 and GoEmotions dataset, and the F1-score was improved to 59.57, which demonstrates the value of multi-dataset fusion and sequence-based emotion models.

Table 10.

Comparative Study of Sentiment Analysis Models on Various Datasets.

Graph-enhanced Transformer architectures were also seen to improve further. In ref. [5], the authors used BERT with Gated Graph Attention (GAT) on the Rest14, Lap14, and Twitter datasets with F1-scores of 82.73, 79.49, and 74.93, respectively, and demonstrated significant improvements in the aspect-based sentiment and short context. Research [6] furthered this trend with 84.27% on sentiment benchmark datasets with Prompt-ConvBERT and Prompt-ConvRoBERTa models, and Research [7] with a hybrid CNN + BERT + RoBERTa model with a similar 84.58% on GoEmotions, indicating the effectiveness of convolutional-semantic fusion. The past traditional baselines, including Naive Bayes (NB) as tested in Study [8] in a variety of datasets (IMDB, Sentiment140, SemEval, STS-Gold), had an F1-score that varied between 73% and 86%, which demonstrated the weakness of non-contextual models. Conversely, Study [9], which used RoBERTa with Adapters and BiLSTM, achieved a better GoEmotions classification of 87, which is indicative of the power of sequential contextual encoding.

Based on these developments, our Hybrid Attention Model (HAM) makes a drastic improvement in its performance by obtaining an F1 score of 94.9% on both the GoEmotions and Amazon Cell Phones and Accessories Reviews datasets. The improved performance can be attributed to the joint efforts of BERT/RoBERTa embeddings, GAT-based relational attention, and BiLSTM-based bidirectional context learning, which, together, allow understanding emotional states on a fine scale and cross-domain flexibility. This indicates that HAM is a successful tool to address the gap between the emotionally charged text in social media and the aspect-based product reviews, which is a new milestone in sentiment analysis studies.

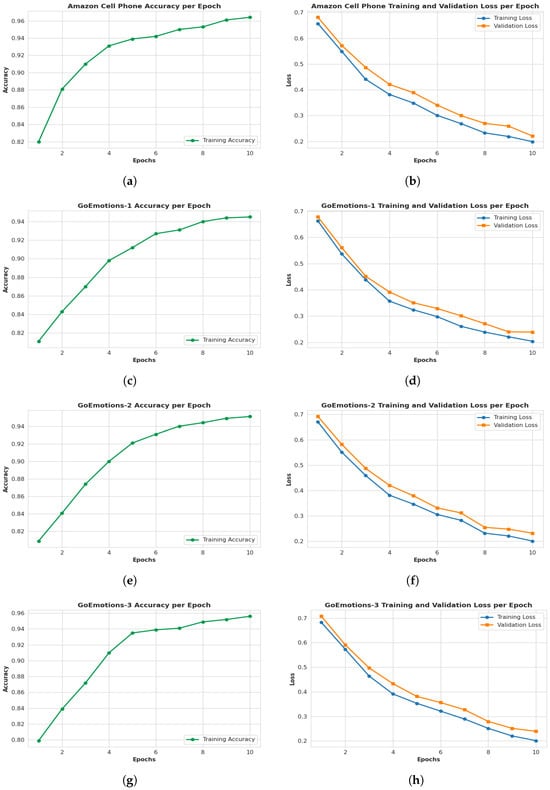

Figure 5 fully illustrates the performance characteristics of the AGF-HAM model in terms of the various dataset mappings and domains of GoEmotions and Amazon Cell Phones. The accuracy and an equivalent training validation loss curve of the Amazon Cell Phones dataset, respectively, resulting in Figure 5a,b, indicate a consistent convergence of the model and the lack of overfitting. The accuracy of GoEmotions-1, GoEmotions-2, and GoEmotions-3 in 10 epochs is shown in Figure 5c,e,g, respectively, and shows a steady improvement and strength over various five-class mappings. In line with this, Figure 5d,f,h demonstrate the training and validation loss curves of the identical mappings, which show the smooth optimization behavior of the model and strong generalization in text domains of various emotions.

Figure 5.

Graph of Accuracy, Training loss, validation loss of Proposed model AGF-HAM. (a) Accuracy (Amazon Cell Phone); (b) Training and validtion loss (Amazon Cell Phone); (c) Accuracy (GoEmotions-1); (d) Training and validtion loss (GoEmotions-1); (e) Accuracy with GoEmotions-2; (f) Training and validtion loss (GoEmotions-2); (g) Accuracy (GoEmotions-3); (h) Training and validation loss (GoEmotions-3).

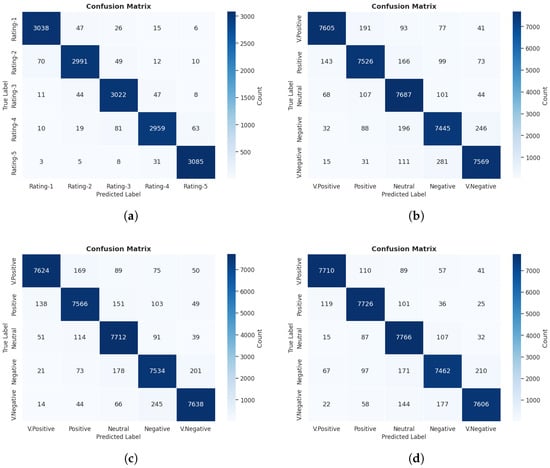

The confusion matrices in Figure 6 give a detailed illustration of the consistency of the AGF-HAM model in the classification of the two datasets. Figure 6a is a representation of the Amazon Cell Phones dataset, where it is evident that there is a separation between the classes and that there is very little misclassification between the levels of sentiments. The GoEmotions-1, GoEmotions-2, and GoEmotions-3 mappings are represented in Figure 6b–d, respectively. These matrices indicate hexahedra prediction patterns with very high accuracy for positive and very positive sentiment categories. All these findings together validate the statement that AGF-HAM has a high level of discriminative ability and domain flexibility and is capable of dealing with structured review data as well as non-structured, empathetic text.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrices of the proposed model AGF-HAM. (a) Confusion Matrix of Amazon Cell Phone; (b) Confusion Matrix of GoEmotions-1; (c) Confusion Matrix of GoEmotions-2; (d) Confusion Matrix of GoEmotions-3.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

The current research presented an overall hybrid of deep-learning architecture (HAM), which combines Transformer-based encoders, bidirectional sequential modeling, attention-based interpretability, and explainability to classify sentiment and emotion robustly. The methodology, which was structured into 13 systematically structured steps, starting with data preprocessing, embedding generation, and aspect extraction, to explainability using attention heatmaps, aspect-level interpretation, and SHAP/Integrated Gradients, guaranteed the predictive power as well as interpretative clarity.

Evaluation: Experimental results on benchmark datasets, such as GoEmotions-1, GoEmotions-2, GoEmotions-3, and Amazon Cell Phones, showed the effectiveness of the proposed HAM model in comparison to the existing Transformer baselines, namely BERT, ALBERT, RoBERTa, XLNet, and hybrid models, including RoBERTa+BiLSTM and DistilBERT+Attention. Interestingly, HAM worked best with an accuracy of 96.4, a precision of 95.1, a recall of 94.7, and an F1-score of 94.9, which is far better than state-of-the-art counterparts. Such findings verify the ability of the model to effectively represent fine-grained contextual nuances, and at the same time, it is interpretable due to its explainability sub-layers.

The transparency and trustworthiness of the predictions provided by the model are ensured by the addition of the Explainability Module, which includes attention heatmaps, aspect-level explanations, and SHAP/Integrated Gradients analysis, which introduces the element of transparency and trust to the performance of deep-learning models in relation to human comprehension. Such a combined methodology not only determines the polarity of sentiment but also reveals the reasons that certain tokens of textual data or factors guide model choices, allowing even more responsible AI behavior.

Future studies can expand the suggested HAM architecture in a number of methodical and topic-focused directions. To begin with, as we have found out that fusion gating and hierarchical attention enhance aspect sensitivity, one way in which future research can complement this finding is by investigating the use of multimodal cues (especially text-aligned visual features) to further enhance aspect-sensitive representations. Second, since the model has been shown to successfully run on datasets with various linguistic properties, cross-lingual adaptation and domain transfer are promising extensions that can be employed technically consistently with the pipeline we have now. Third, the explainability modules (attention heatmaps and SHAP/IG) employed in this study can be extended to interactive, real-time explainability dashboards to facilitate transparency of decisions in the application areas. Lastly, a lightweight or adapter-based variant of HAM could be useful to scale to large-scale or privacy-considerate contexts, providing viable deployment advantages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K. and L.K.; software, M.K.; validation, L.K.; formal analysis, L.K., M.Z.K. and A.A.A.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.Z.K. and A.A.A.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K. and L.K.; writing—review and editing, L.K., M.Z.K. and A.A.A.; supervision, L.K., M.Z.K. and A.A.A.; project administration, L.K., M.Z.K. and A.A.A.; funding acquisition, M.Z.K. and A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R308), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study, referred to as the dataset “GoEmotions” and “Amazon Cell Phones Reviews” are openly available on Kaggle at the following links: GoEmotions (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/debarshichanda/goemotions, accessed on 12 September 2025) Amazon Cell Phones Reviews (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/grikomsn/amazon-cell-phones-reviews?select=20191226-reviews.csv, accessed on 3 August 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R308), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hussain, A.; Cambria, E.; Schuller, B.; Howard, N.; Poria, S.; Huang, G.-B.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Toh, K.-A.; Wang, Z.; et al. A semi-supervised approach to Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2018, 10, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; Khan, I.; Alharbi, A.; Alshammari, M.; Alshammari, T.; Ahmad, M. Unifying Sentiment Analysis with Large Language Models: A Survey. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103651. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, I.; Cambria, E.; Welsch, R. Bayesian neural networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2018, 10, 766–777. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, O.; Goldberg, Y. Neural word embedding as implicit matrix factorization. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Liu, K.; He, S.; Zhao, J. How to generate a good word embedding. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016, 31, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luong, T.; Jurafsky, D.; Hovy, E. Inferring sentiment with social attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ACL, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 July–4 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, N.; Majumder, P.; Ekbal, A. Recent trends in deep learning based sentiment analysis. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 1180–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1 (long and short papers), pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, A. Hierarchical attention based position-aware network for aspect-level sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–1 November 2018; pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Madasu, A.; Rao, V.A. A position aware decay weighted network for aspect based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applications of Natural Language to Information Systems, Helsinki, Finland, 24–26 June 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z. Fine-tune BERT with sparse self-attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 3548–3553. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Gao, J.; Ren, X.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Kwok, J.T.Y. Sparsebert: Rethinking the importance analysis in self-attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 9547–9557. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.M. Does machine learning really work? AI Mag. 1997, 18, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P.; Heinrich, K. Machine learning and deep learning. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Lee, L. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found. Trends® Inf. Retr. 2008, 2, 1–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, A.I. Opinion mining on US Airline Twitter data using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Computer Engineering Conference (ICENCO), Cairo, Egypt, 29–30 December 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, A.; Agrawal, A.; Rath, S.K. Classification of sentiment reviews using n-gram machine learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 57, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouloumpis, E.; Wilson, T.; Moore, J. Twitter sentiment analysis: The good the bad and the omg! In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Barcelona, Spain, 17–21 July 2011; Volume 5, pp. 538–541. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, A.; Khan, L.; Chang, H.T. Effect on speech emotion classification of a feature selection approach using a convolutional neural network. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad, A.; Khan, L.; Chang, H.T. Semi-natural and spontaneous speech recognition using deep neural networks with hybrid features unification. Processes 2021, 9, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1408.5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Afaq, K.M.; Chang, H.T. Deep sentiment analysis using CNN-LSTM architecture of English and Roman Urdu text shared in social media. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Ashraf, N.; Chang, H.T.; Gelbukh, A. Urdu sentiment analysis with deep learning methods. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 97803–97812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.; Amjad, A.; Ashraf, N.; Chang, H.T. Multi-class sentiment analysis of urdu text using multilingual BERT. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]