Abstract

With the growth of network scale and the sophistication of cyberattacks, traditional learning-based traffic analysis methods struggle to maintain generalization. While Large Language Model (LLM)-based approaches offer improved generalization, they suffer from low training and inference efficiency on consumer-grade GPU platforms—typical in resource-constrained deployment scenarios. As a result, existing LLM-based methods often rely on small-parameter models, which limit their effectiveness. To overcome these limitations, we propose to use a large-parameter LLM-based algorithm for network traffic analysis that enhances both generalization and performance. We further introduce two key techniques to enable practical deployment and improve efficiency on consumer-grade GPUs: (a) a traffic-to-text mapping strategy that allows LLMs to process raw network traffic, coupled with a LoRA-based fine-tuning mechanism to improve adaptability across downstream tasks while reducing training overhead; and (b) a sparsity-aware inference acceleration mechanism that employs a hot–cold neuron allocation strategy to alleviate hardware bottlenecks and predicts inactive neurons to skip redundant computations. Experimental results on a consumer-grade NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU show that our method outperforms existing LLM-based approaches by 6–8% in accuracy across various network traffic analysis tasks, benefiting from the adoption of large-parameter models. Furthermore, our approach achieves up to a 4.07× improvement in inference efficiency compared with llama.cpp, demonstrating both the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed design for real-world network traffic analysis applications.

Keywords:

network security; network traffic analysis; large language model; LoRA fine-tuning; sparsity-aware acceleration MSC:

68T05

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the continuous expansion of network scale and the increasing sophistication of attack techniques, network traffic analysis has become a cornerstone of cybersecurity defense systems. Traffic analysis not only enables the effective distinction between benign communications and malicious attacks, but also plays a critical role in intrusion detection, malware identification, and anomalous behavior tracking. However, with the diversification of attack methods, traditional approaches based on feature engineering or shallow models have gradually revealed their limitations when confronting complex and dynamic network environments [1,2].

Researchers have proposed a variety of deep learning-based approaches [3,4] to network traffic analysis. These approaches can automatically extract traffic features and have achieved promising results in tasks such as traffic classification and malicious activity detection. Nevertheless, most existing models are trained for single tasks or specific scenarios, resulting in limited generalization capabilities. They struggle to achieve cross-task adaptability and cross-scenario transferability. This problem is particularly pronounced in practical applications, often leading to a significant decline in model performance outside the training environment.

The recent development of Large Language Models (LLMs) offers new opportunities to overcome these limitations. Pretrained on massive corpora, LLMs exhibit strong contextual modeling and knowledge transfer capabilities, which endow them with remarkable generalization across diverse tasks and scenarios [5]. Existing studies such as TrafficLLM [6] have attempted to introduce LLMs into traffic analysis. By transforming raw traffic into an input format that LLMs can process, TrafficLLM effectively bridges the modality gap between traffic data and natural language, enabling the model to demonstrate strong contextual modeling and knowledge transfer capabilities across multiple tasks and scenarios. Nevertheless, it still relies on small-scale language models, which are significantly smaller than mainstream general-purpose LLMs with tens or even hundreds of billions of parameters. Due to these limitations in model size and computational resources, it struggles to maintain stable semantic understanding and generalization in complex attack scenarios, leading to inconsistent detection performance under varying data distributions.

To further enhance adaptability and generalization, this study considers adopting a larger 30B-parameter language model. However, in scenarios such as cybersecurity, which have strict requirements for real-time performance and efficiency, its deployment faces two major bottlenecks. The primary bottleneck is inference efficiency. Blindly increasing the model parameter scale is accompanied by higher memory requirements, as well as more complex computation scheduling, significantly increasing single-instance inference latency. This high latency severely restricts throughput in multi-turn or high-concurrency scenarios, greatly limiting the practical deployment and application efficiency of large models. To address this challenge, existing inference frameworks (e.g., llama.cpp [7]) in hardware-constrained scenarios typically adopt a layer-by-layer splitting strategy based on hybrid offloading, allocating computation between the GPU and CPU at the Transformer layer level. While this strategy is simple in design and reduces cross-device data transfer overhead to some extent, it still has serious flaws. On one hand, it causes a severe locality mismatch problem: GPU memory capacity limitations result in most layers being stored on the CPU, which in turn forces the slower CPU to undertake the primary computational tasks, ultimately causing significant inference latency. On the other hand, this layer-by-layer splitting is a coarse-grained resource scheduling strategy. It ignores the significant differences in computational requirements and memory access patterns among different operational units within the same layer, thus making it impossible to achieve fine-grained scheduling and failing to fully leverage the GPU’s computational advantages.

In addition to the severe inference challenge, there is also an extra parameter burden during the model’s fine-tuning and adaptation phase: existing methods rely on inserting learnable prompt embeddings into each layer of the model, causing the number of parameters that need to be fine-tuned to grow linearly with the increase in model layers. This strategy not only greatly increases the training burden but also introduces additional computational and latency overhead during the inference phase.

To address the above issues, this paper extends and optimizes TrafficLLM by proposing an efficient and flexible LLM training and inference framework for network traffic analysis. During the training/fine-tuning stage, we design a mapping mechanism that transforms raw traffic information into natural language-like sequences acceptable to LLMs. On the preprocessed data, a LLM tokenizer is further trained in the traffic domain, enabling the model to better capture and represent traffic semantics. In addition, we adopt the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique to perform low-rank optimization on model weights, allowing the model to maintain its original performance while substantially reducing the number of parameters that need to be loaded during inference. This effectively alleviates the memory and computational burden of TrafficLLM during real-time inference.

In the deployment stage, to address the performance bottlenecks and resource constraints commonly encountered when deploying large-scale models, we further propose an efficient acceleration mechanism based on LLM sparsity. Specifically, neuron activation statistics are collected to divide weights into frequently activated “hot neurons”, which are assigned to the GPU, and infrequently activated “cold neurons”, which are placed on the CPU. In addition, an adaptive sparsity predictor forecasts the subset of neurons expected to be activated for the current input. The inference engine then computes only these neurons, skipping the majority of inactive ones and significantly reducing computational overhead. Through this mechanism, our framework enables efficient large-scale LLM inference under constrained GPU resources and substantially accelerates traffic analysis tasks.

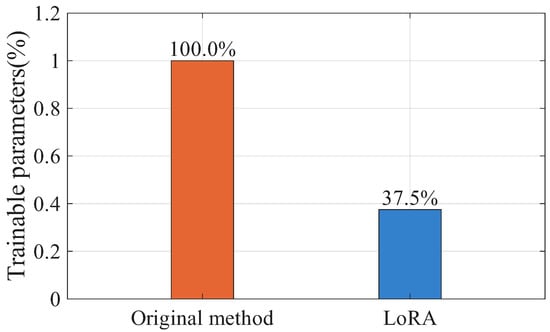

Performance evaluations demonstrate that, compared with TrafficLLM, our model achieves substantial improvements in both accuracy and generalization capability. Experiments conducted on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 show that: (1) our method consistently achieves over 80% accuracy across all downstream tasks, outperforming other LLM-based approaches by 5–10% for network traffic analysis; (2) in the training stage, our method updates only 37.5% of the trainable parameters required by the original method [6], yet achieves comparable performance, improving parameter efficiency and reducing overall training time by approximately 15%; and (3) in the inference stage, our method achieves up to 4.07× speedup over the baseline llama.cpp (commit: 0a2a384, accessed on 2 September 2025) implementation and further demonstrates strong scalability in GPU–CPU hybrid loading environments. We also conduct experiments on an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin (NVIDIA Corporeation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an embedded GPU, achieving performance comparable to that on the A6000 (NVIDIA Corporeation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) These results fully validate the feasibility and efficiency of our traffic adaptation and inference acceleration strategy in real-world network traffic analysis scenarios, offering new directions for the practical application of LLMs in cybersecurity.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

- We introduce a LoRA-based fine-tuning strategy that effectively reduces the number of trainable parameters while preserving model performance, enabling efficient adaptation of large-scale LLMs to traffic analysis tasks.

- We design a hybrid hot–cold neuron inference mechanism for LLM-based network traffic analyzer that allocates most computations to the GPU to fully exploit its parallel capability, while a lightweight activation predictor forecasts neuron activity in advance to reduce redundant computation and improve overall efficiency.

- We conduct comprehensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets, showing that the proposed framework achieves up to 4.07 times acceleration compared to the llama.cpp implementation while maintaining over 80% accuracy, demonstrating its feasibility in real-world network security applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Large Language Models

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) such as GPT [8], LLaMA [9], and ChatGLM [10] have demonstrated remarkable generality and transferability in natural language understanding and generation tasks. These models, leveraging massive parameters and powerful representation learning capabilities, can achieve high performance across diverse downstream tasks. Even with only a few examples or prompts (few-shot), they can rapidly adapt to new task requirements. Furthermore, LLMs exhibit inherent adaptability to multi-modal inputs, complex contextual information, and task diversity, making them widely applicable in natural language processing, question answering, and reasoning tasks.

However, the enormous scale of LLMs, typically ranging from billions to hundreds of billions of parameters, results in very high computational demands when adapting LLMs to specific domains and tasks. To alleviate this issue, researchers have proposed various parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) methods. For example, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [11] introduces low-rank matrices to approximate parameter updates, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters. Such approaches maintain model performance while drastically lowering fine-tuning costs, enabling efficient deployment of large LLMs across diverse downstream tasks.

With the success of PEFT, the use of LLMs has gradually expanded beyond traditional natural language processing toward domain-specific applications. In the field of network security and management, researchers have begun exploring how to leverage LLMs to handle tasks such as network log analysis [12] and intelligent operations and maintenance (O&M) [13]. These studies demonstrate the potential of LLMs in understanding and reasoning over complex network-related textual data. Nevertheless, research applying LLMs directly to raw network traffic remains extremely limited. Our study is therefore motivated by this critical gap and aims to explore how LLMs can be efficiently adapted for network traffic analysis.

Meanwhile, LLM has advanced to the implementation in distributed systems. Examples include using Federated Learning (FL) to coordinate vehicles with limited computing capabilities in Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) [14], or using blockchain to ensure trust in distributed edge deployments [15]. While this “cross-node” paradigm is valid, our work focuses on the challenge of running the model on a single node.

2.2. Network Traffic Analysis

Early network traffic analysis mainly relied on manually crafted rule-based detection mechanisms. Although these methods were interpretable, they were highly dependent on expert knowledge and had poor generalization when dealing with encrypted or unknown threats. To improve automation, researchers turned to machine learning [2,16]. However, these methods became highly dependent on manually crafted statistical features. Subsequently, deep learning (DL) techniques [3,4] addressed the feature engineering challenge with their end-to-end learning capabilities, automatically extracting features from raw data. However, DL models introduced their own fundamental limitations: a heavy reliance on large-scale, costly labeled data, and high coupling between the model and the task, which limits generalization to new scenarios.

To address these issues of data dependency and poor generalization, before the rise of the LLM paradigm, some studies (e.g., ET-BERT [17] and PERT [18]) attempted to use architectures based on Pre-trained Language Models (PLMs) to process traffic data. However, these models suffer from numerous limitations: first, their parameter scale is typically small (e.g., less than 1B), lacking the surprising emergent abilities characteristic of large models that provide strong generalization [19]; second, they primarily rely on high-cost pre-training from scratch and cannot inherit the general knowledge of existing LLMs as the fine-tuning paradigm can, and they exhibit limited capabilities in generalizing to unseen traffic [20].

In this frontier area, TrafficLLM [6] stands out as one of the few seminal works specifically addressing the aforementioned challenges. This method explicitly points out the limitations of general-purpose LLMs and innovatively proposes a “traffic-domain tokenization” scheme designed specifically for heterogeneous raw traffic. TrafficLLM further employs a dual-stage fine-tuning framework, aiming to learn a “general traffic representation” that can effectively handle downstream traffic detection and generation tasks. Compared to earlier BERT-like models, TrafficLLM demonstrates clearly superior performance in both model scale and its representation methods for traffic. Critically, the method excels in generalization, effectively identifying unseen traffic and overcoming the limitations of traditional methods when facing dynamically changing network environments (such as distribution shift).

Nevertheless, it still relies on small-scale language models, which are significantly smaller than mainstream general-purpose LLMs with tens or even hundreds of billions of parameters. Due to these limitations in model size and computational resources, it struggles to maintain stable semantic understanding and generalization in complex attack scenarios, leading to inconsistent detection performance under varying data distributions. This presents a critical trade-off: while adopting a massive-scale LLM could solve these performance issues, deploying such large language models also introduces enormous hardware costs and inference latency. Our study is therefore based on TrafficLLM’s modality-adaptation framework, aiming to improve upon it by addressing this exact challenge: developing an efficient inference system to enable a massive-scale LLM for real-time traffic analysis on consumer-grade hardware.

2.3. LLM Deployment in Resource-Constrained Environment

As the parameter scale of Transformer-based architectures grows exponentially, the inference and deployment overhead of LLMs has become a primary obstacle to their application in resource-constrained environments. To address this challenge, research paths have primarily diverged into several main categories.

In the area of static model compression, researchers have revisited and enhanced traditional compression techniques to better adapt them to the architectural characteristics and inference demands of LLMs, achieving promising results in inference acceleration and energy efficiency optimization [21]. Pruning techniques aim to remove redundant parameters or structures; for instance, LLM-Pruner [22] focuses on structured pruning, while SparseGPT [23] implements efficient unstructured sparsity. Quantization techniques, in turn, reduce overhead by lowering numerical precision, encompassing post-training quantization (PTQ), as represented by LLM-FP4 [24], and quantization-aware training (QAT), as represented by LLM-QAT [25]. Additionally, Knowledge Distillation achieves compression by training small student models (e.g., MINILLM [26] and LaMini-LM [27] to mimic the output distribution of large teacher models.

However, these compression techniques designed for LLMs face their own tradeoffs in application: for example, QAT and knowledge distillation require high retraining costs, while PTQ and pruning must strike a balance between compression ratio and model performance. More critically, when the model scale is extremely large (e.g., 30B or 70B), static compression techniques alone are often insufficient to adapt the model to consumer-grade hardware with extremely limited VRAM.

Dynamic inference systems are another key approach for efficient LLM deployment. For example, vLLM [28] significantly reduces memory fragmentation by efficiently managing the key-value (KV) cache, while TensorRT-LLM [29] minimizes computation latency through operator fusion and on-the-fly batching. Both aim to maximize throughput and GPU utilization. Although they are very effective, their design largely relies on the model weights fully fitting into GPU memory, which makes them difficult to apply when the model size far exceeds the capacity of consumer-grade GPUs.

To address the VRAM bottleneck, llama.cpp [7] provides a hybrid execution solution, offloading model layers between the CPU and GPU. This heterogeneous deployment capability has made it popular on consumer-grade hardware. However, this “layer-by-layer splitting” offloading strategy is too coarse-grained: it fails to consider the differences in overhead among various computational units within a layer during splitting, leading to the slower CPU bearing the primary computational load. This prevents the full utilization of the heterogeneous hardware, ultimately resulting in high inference latency.

In summary, existing approaches fail to provide an efficient, single-node solution for deploying massive-scale LLMs on consumer-grade hardware. Static compression is often insufficient, and high-throughput systems like vLLM are inapplicable. While llama.cpp introduces the correct concept (hybrid execution), its coarse-grained strategy creates a critical performance bottleneck.

Our research aims to address this specific gap. We draw inspiration from the hybrid CPU/GPU execution model, but propose a novel, fine-grained allocation strategy to overcome the limitations of layer-based splitting. We apply this framework to the domain of network traffic analysis, a field where efficiently deploying powerful, large-scale models on consumer-grade hardware is a critical, yet largely unsolved, challenge.

3. Overall Framework

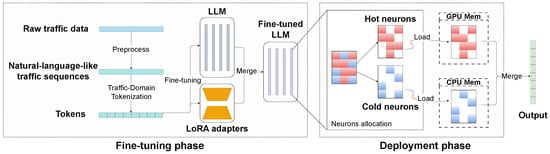

We propose an efficient LLM-based framework for network traffic analysis, consisting of two primary stages: the fine-tuning phase and the deployment phase. This framework is designed to address the challenges of applying LLMs with massive parameters in traffic analysis scenarios, fully leveraging their strong generalization ability across diverse tasks while enabling lightweight deployment and efficient inference under limited hardware conditions. It extracts traffic patterns from raw pcap packets and maps them to a natural language-like LLM input format. Correspondingly, the framework’s output is also generated in human-readable natural language, generated token by token, that clearly states the analysis result for the input traffic. It then uses the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique for efficient fine-tuning with domain knowledge. During inference, neurons are distributed across CPU and GPU based on activation, with an adaptive predictor skipping inactive neurons, reducing hardware costs and accelerating 30B-scale LLM traffic analysis. We present an overview of the architecture in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System Architecture.

Fine-tuning phase. To bridge the modality gap between natural language and heterogeneous traffic data, we preprocess raw traffic data in pcap format according to specific analysis task and design a traffic-to-text mapping mechanism and an instruction-based modeling approach to achieve semantic representation of raw network traffic, enabling the LLM to understand and process traffic features in a more natural way. At the same time, we train a domain-specific tokenizer tailored to the characteristics of network traffic data, which significantly improves the model’s encoding efficiency and representational capability in traffic-related tasks. Subsequently, LoRA technique is introduced for fine-tuning of LLMs. Compared with the original method in TrafficLLM [6], where inserting prefix vectors into each layer increases the number of trainable parameters linearly, LoRA introduces trainable low-rank decomposition parameters into the weight matrices, substantially reducing the required parameters for fine-tuning. This design preserves model performance while effectively mitigating computational load and latency during inference, enabling higher efficiency in practical deployment.

Deployment phase. To reduce hardware resource consumption and improve inference efficiency, we leverages hybrid inference across both GPU and CPU to support the deployment of large-scale LLMs on consumer-grade GPUs. Concretely, in the offline phase, we divide the model’s neurons into hot and cold subsets according to their activation patterns under different input samples, forming a flexible GPU–CPU hybrid allocation strategy. The frequently activated neurons are kept on the GPU while the infrequently activated neurons are mapped to the CPU to take advantage of its parallelism. in the online phase, we introduce a dynamic activation prediction mechanism that adaptively identifies the neurons actually activated by the current input during inference, thereby skipping redundant computation on inactive neurons. Through these optimizations, the proposed framework achieves efficient large-model inference in resource-constrained environments while maintaining accuracy, significantly reducing computational redundancy and hardware energy consumption.

4. Fine-Tuning for LLMs

4.1. Input Modality Adaptation

Most machine learning or deep learning methods transform raw network traffic into structured feature vectors or low-dimensional embeddings for downstream analysis, thereby preserving the semantic information and field correlations within the original data. However, when applying LLMs to traffic analysis tasks, such processing often leads to an input modality mismatch. Since LLMs are fundamentally designed around natural language, their inputs are expected to be text sequences with linguistic characteristics rather than abstract embedding vectors. This discrepancy makes it difficult for LLMs to interpret traffic data represented in purely structured forms.

To address this issue, our framework follows the modality adaptation strategy of TrafficLLM. First, we adjust the input data format. Our process begins with raw network traffic in pcap format, rather than relying on any pre-computed statistical metrics. The core idea is to convert this raw packet data into sequences closer to natural language to match the input characteristics of LLMs. From this raw input, each network packet is thoroughly parsed, allowing us to extract header fields and payload contents. Each field name is paired with its corresponding value along with the associated protocol semantics, and organized in a “field: value” format. These elements are then concatenated in protocol-layer order to generate a structurally complete and semantically explicit packet description resembling natural language. This approach better preserves both the semantic and structural features of traffic data, transforming traffic inputs into a modality more familiar to LLMs, which facilitates modeling and understanding by LLMs. Correspondingly, at the output stage, LLMs also generate human-readable natural language rather than traditional class indices. During inference, the models output tokens one by one in an auto-regressive fashion. These tokens ultimately converge into a semantically complete phrase or sentence that clearly states the analysis and discrimination result for the input traffic, thereby achieving stronger human readability.

Building upon this, we employ traffic-domain tokenization, using the preprocessed traffic sequences to train a specialized tokenizer. Since vanilla LLMs have rarely encountered traffic data, the domain-specific tokenizer serves as an extension and supplement to the general tokenizer. By leveraging frequency statistics derived from traffic data, the tokenizer effectively preserves the semantics of field names, thereby reducing the modality gap when processing heterogeneous data and enhancing the model’s generalization ability across diverse tasks and scenarios.

Furthermore, to fully leverage the advantages of prompt engineering, users can design task-specific prompts according to downstream requirements. By specifying tasks, desired outputs, or analysis objectives in natural language, prompts help the model not only better interpret the semantics embedded in the input data but also perform analyses in a more task-oriented manner.

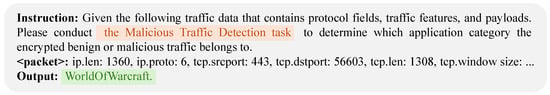

In constructing the final model input, task-specific prompts are placed before the natural language representation of traffic data, together forming a complete input sequence. This input design provides task-related context while preserving the full richness of the original traffic information. This enables the model to first acquire task background knowledge and then integrate it with the raw data for analysis. Consequently, it effectively guides the model to generate expected analytical results without compromising the original traffic semantics and allows LLMs to better understand and process diverse network traffic analysis tasks, further leveraging their powerful generalization and expressive capabilities. An example of the transformed final input and the LLM output is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

An example of the transformed final input and the LLM output.

4.2. Low-Rank Adaptation

To address the parameter growth and deployment complexity introduced by learnable prompt embeddings during the fine-tuning and deployment stages of TrafficLLM, this study adopts Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) for parameter-efficient fine-tuning of the pretrained LLM. In TrafficLLM, task adaptation is achieved by inserting learnable prompt vectors into each layer of the model. As the number of layers increases, the total amount of such prompt vectors grows linearly, and during inference, they must be loaded and processed as additional inputs, which increases both storage and runtime overhead. In contrast, LoRA injects low-rank increments only into selected linear transformations, thereby significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters and simplifying the deployment process without altering the original model architecture.

Formally, let be the input sequence, and let be the hidden state at position i. The output logits are obtained through a linear projection:

where denotes the output projection matrix, V is the vocabulary size, and d is the hidden dimension.

The training loss adopts the Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) form, defined as:

where is the number of samples in a batch, and denotes the sequence length of the n-th sample.

When LoRA is applied, the model parameters are decomposed as

where represents the frozen pretrained weights, and denotes the low-rank update introduced by LoRA. For a single weight matrix to be adapted, , LoRA expresses its increment as

where and , with rank .

The overall optimization objective is to solve only for the low-rank parameters:

The primary advantage of this formulation is a significant reduction in trainable parameters. Let L be the number of model layers, d be the hidden dimension, and p be the effective prompt length for the original method in TrafficLLM. The number of trainable parameters for that method scales with the number of layers, approximately . In contrast, for LoRA, if we adapt k weight matrices per layer (e.g., for the query, key, and value projections) with a rank r, the total trainable parameters is approximately . Given that k (matrices per layer) and the rank r are typically very small (e.g., 8 or 16), the number of trainable parameters in LoRA is often orders of magnitude smaller than in the original prompt-based method while achieving comparable performance.

This reduction is critical, as it means only a few megabytes of weights need to be stored and loaded per task, rather than a large set of layer-dependent prompt vectors. In addition to this significant parameter reduction, LoRA also offers greater flexibility compared to the original fine-tuning method in TrafficLLM. In practice, task-specific selective insertion strategies can be applied: one approach embeds LoRA modules in the initial layers to reduce training complexity while retaining core feature modeling capacity; another approach introduces LoRA in cross-attention layers, which contain the largest number of parameters and computational costs, thereby concentrating optimization on critical components without modifying the entire model architecture redundantly. These strategies further reduce the number of trainable parameters, lowering both training and inference costs, and making the model more suitable for deployment in resource-constrained environments. This enables rapid and cost-effective adaptation of LLMs to downstream traffic analysis tasks.

5. Inference Acceleration for LLMs

5.1. Neuron-Level Inference Optimization

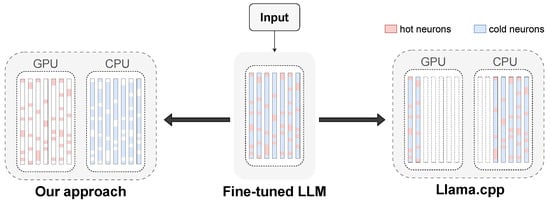

We move beyond layer-based partitioning to focus on finer-grained structural features at the neuron level. Considering that attention layers are computation-intensive and have high bandwidth requirements, they are more suitable for deployment on GPUs. Conversely, while feedforward network (FFN) layers possess huge parameters, their communication overhead is relatively low and their computational rules are straightforward. This allows them to leverage the high cache depth and SIMD instruction sets of modern CPUs for acceleration, making them more valuable for offloading in resource-constrained environments. However, directly offloading the entire FFN layer to the CPU still creates a performance bottleneck. Further analysis indicates that the ReLU activation function in the OPT model induces significant sparsity: some neurons exhibit high-frequency activation, while others remain in a low-activity state for extended periods. Consequently, neurons can be further categorized as “hot neurons” and “cold neurons” based on their activation patterns. Hot neurons exhibit high activation frequencies, significantly impacting inference latency and model performance, making them ideal for deployment on GPUs. Conversely, cold neurons rarely participate in computations and can be offloaded to CPUs. Figure 3 illustrates the structural comparison between this fine-grained allocation strategy and the layer-based approach of llama.cpp.

Figure 3.

Layer-based allocation of llama.cpp vs. fine-grained allocation of our approach.

Offline Neuron Allocation: To better adapt LLMs to network traffic analysis, we analyze neuron activations on traffic-related datasets to capture domain characteristics and derive a more suitable neuron allocation strategy. Inspired by PowerInfer [30], we designed and implemented an offline analyzer to systematically monitor and record the internal activation behavior of the LLM during inference. The analyzer first loads network traffic samples that have been preprocessed into a natural language-like format, and then invokes the inference interface of the LLM to perform forward propagation and compute layer-wise outputs. To accurately capture neuron-level dynamics, monitoring probes are inserted after each block within every Transformer layer. These probes do not modify the model’s computational logic but act as hooks that capture the activation values of each neuron during forward propagation. After obtaining the activation values, the probe module determines whether a neuron is activated based on a predefined threshold and maintains a neuron information table. This table assigns a unique index to each neuron and records its cumulative activation frequency across the entire dataset, providing an intuitive representation of the neuron activation patterns within network traffic domain data.

Based on these statistics, we define the Neuron Impact Factor (NIF) as the activation frequency of a neuron over the traffic datasets. Higher NIF values indicate greater importance for traffic analysis tasks. The optimization goal is to maximize the total NIF of neurons allocated to the GPU, subject to several constraints. First, the total number of GPU activations must be constrained by the available graphics memory capacity. Second, each layer must retain a minimum proportion of GPU neurons to preserve computational continuity and avoid excessive CPU–GPU communication. We model this problem using Integer Linear Programming (ILP). To address the slow solution time of ILP due to an excessive number of decision variables, we introduce a neural batch aggregation strategy: neurons with similar NIF values are grouped into batches of 256, and allocation decisions are made at the batch level. This reduces the number of decision variables from hundreds of thousands at the neuron level to only thousands at the batch level, enabling the ILP problem to be solved within seconds and greatly improving efficiency.

Online Neuron Activation: Building upon this foundation, we further design an online neuron activation predictor to reduce dynamic redundancy during inference. The ReLU activation function produces a large number of zero outputs, resulting in far fewer neurons being effectively involved in computation than the theoretical maximum. Since this sparsity is highly context-dependent, the activation state of neurons dynamically varies with the input, making it necessary to determine neuron activity in real time during inference. To address this, we propose an online prediction mechanism that dynamically estimates the activation state of neurons, performing forward computation only for neurons predicted as active while skipping those predicted as inactive.

However, in resource-constrained local deployments, predictor design must balance accuracy and complexity. Analysis and experiments show that FFN modules exhibit varying predictability across Transformer layers. Using uniform-sized predictors leads to two problems: underfitting for complex layers and wasted resources for simple ones. To overcome this, we ultimately propose an iterative adjustment-based non-uniform predictor architecture that independently customizes predictors of varying sizes for each Transformer layer. Each MLP predictor adopts a simple three-layer structure: inputs are projected onto the hidden dimension via a fully connected mapping, undergo ReLU activation, and are then mapped to the output dimension. Since the input and output dimensions are determined by the network architecture, the size of the hidden layer becomes the key adjustable factor. During training, the predictor is first pre-trained on a large-scale general dataset, dynamically adjusting the hidden dimension based on recall. It is then fine-tuned on the traffic dataset to mitigate overfitting and enhance domain adaptability. Through iterative optimization, predictor complexity is gradually refined until convergence is achieved within the desired accuracy and resource bounds. With this differentiated configuration strategy, the total parameter size of all predictors is constrained, ensuring predictive accuracy while significantly reducing inference resource consumption.

5.2. Hybrid GPU–CPU Execution

As described above, we implement a GPU–CPU hybrid execution model. Before handling user requests, the system leverages the neuron allocation strategy generated in the offline analysis phase: frequently activated hot neurons are preloaded into GPU memory, while less frequently activated cold neurons are stored in CPU memory. Upon receiving an input, the online predictor identifies potentially active neurons in each layer and skips inactive ones. If a target neuron has been preloaded into GPU memory, its computation is performed on the GPU; otherwise, the CPU executes it. It is worth noting that neurons labeled as “hot” in the offline phase are not guaranteed to be active at runtime—some may still remain inactive depending on the specific input. As a result, this mechanism enables rational distribution of computation between GPU and CPU, maintaining the model’s representational power while significantly reducing both computational load and memory footprint. Ultimately, this achieves efficient large-scale LLM inference under resource-constrained environments.

During inference, the FFN layer is split into two parallel computation branches, with the GPU and CPU each processing their assigned subsets of neurons. The system creates two types of executors (implemented with pthreads) to coordinate tasks on both devices. The GPU executor launches CUDA kernels (e.g., via cudaLaunchKernel) to perform dense computations in parallel, thereby leveraging the massive parallelism of GPUs. Meanwhile, the CPU executor schedules multi-core resources, dynamically adjusting the number of threads according to the workload, and computes the low-activation neurons in parallel to maximize CPU resource utilization.

In multi-device parallel computing, the integration and synchronization of cross-device results are critical challenges. The system unifies all merging operations on the GPU side for two primary reasons. First, the activation tensors processed by the GPU are typically computationally intensive and large in scale. Merging them on the CPU would necessitate extensive intermediate result transfers and significantly increase communication overhead. Second, merging operations inherently involve large-scale tensor concatenation and accumulation, exhibiting high parallelism that aligns well with GPU architecture characteristics. Therefore, performing merging within the GPU not only minimizes cross-device data movement but also enhances overall execution efficiency. This approach allows the GPU to shoulder more load during the merging phase, with the CPU providing auxiliary support only when necessary.

To correctly implement cross-device result integration, two dedicated merge points are introduced in each FFN layer, positioned after the Up/Gate and Down matrix multiplications, respectively. The first merge point consolidates partial results from GPU and CPU after the Up/Gate stage, thereby providing consistent input for subsequent activation and tensor transformation, while preserving data dependencies. The second merge point is triggered after the Down stage to concatenate and combine results from both devices into the final output that conforms to the original FFN structure, which is then forwarded to the next layer. These merge points ensure both data consistency and dependency correctness, while also enforcing proper execution ordering, because subsequent computations cannot be triggered until the current merging completes.

Furthermore, to reduce synchronization overhead and prevent idle GPU waiting, we introduce a selective synchronization mechanism. If no active neurons are assigned to the CPU in a given stage, the CPU’s computation and synchronization are automatically bypassed, allowing the GPU to proceed directly to the next stage. This mechanism effectively reduces idle delays and enhances overall inference efficiency, enabling the hybrid execution model to maintain high resource utilization and execution performance across varying load distributions.

6. Evaluation

6.1. Experimental Setup

Hardware Environment. To evaluate the generalization ability of the proposed method under different hardware configurations, we conducted experiments on the following PC setup: an Intel Xeon Gold 5122 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (8 physical cores, 16 threads, 3.6 GHz base frequency), 125 GB DDR4 system memory (bandwidth ≈ 102 GB/s), an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (48 GB VRAM, 768 GB/s memory bandwidth), and a PCIe 4.0 interface (bandwidth 64 GB/s).

Model Configuration. We employed the OPT-30B model for all experiments. Model parameters were stored in FP16 precision, while intermediate activations were computed in FP32 precision, which is consistent with the standard practices adopted in recent LLM studies [31,32]. Our LoRA configuration used a rank (r) of 16 and a scaling factor alpha () of 32. We applied LoRA modules to the query, key, and value matrices within all Transformer blocks. A dropout rate of 0.1 was set for the LoRA layers. To further evaluate the model’s adaptability and inference performance in real-world consumer-grade GPU scenarios, we also tested a version of the model quantized to INT8. To solve the ILP problem specified in Section 5.1, we use the cvxopt library.

Datasets. For the training of LLMs, we selected two representative public network traffic analysis datasets: USTC-TFC-2016 [33] and ISCX-VPN-2016 [34], corresponding to the tasks of malicious traffic detection and VPN traffic detection, respectively. The former covers 10 categories of common malicious traffic as well as benign application traffic. Each category contains preprocessed traffic fragments, making it suitable for malicious traffic detection and classification tasks. The latter dataset was constructed based on a detailed analysis of VPN and non-VPN network traffic. It was collected by simulating various network activities in a controlled environment, including web browsing, file transfer, and video streaming. During data collection, VPN and non-VPN traffic were transmitted through separate network paths to ensure the diversity and representativeness of the data. Together, these two datasets cover typical traffic analysis scenarios and facilitate the evaluation of cross-task generalization.

For the training of the predictor, we employed the C4 dataset [35], sampling 8000 data points for pretraining the predictor. Subsequently, the predictor was further adapted on task-specific traffic datasets, allowing it to better handle diverse types of traffic inputs.

Baseline Systems. For cross-scenario generalization, we compare our system against the 6B-scale LLM of TrafficLLM [6] to assess the potential advantages of larger models in terms of generalization. Previous attempts at related tasks had not yet utilized models of this scale. For inference efficiency, we compared against the state-of-the-art local inference framework llama.cpp, to evaluate improvements in inference speed and resource consumption. It is worth noting that, since llama.cpp does not natively support the OPT architecture, we extended its implementation to ensure compatibility.

Metrics. We evaluate the proposed method from two perspectives: (1) Cross-scenario generalization capability. The model performance is evaluated on various downstream tasks using Accuracy (AC), weighted Precision (PR), weighted Recall (RC), and weighted F1-score (F1) as the main evaluation metrics. To ensure reliability, all experiments are conducted on 5 independent test sets, and the average performance is reported; (2) Inference efficiency. We focus on end-to-end generation speed in low-latency scenarios, quantified by tokens per second (tokens/s). Specifically, this metric is defined as the total number of tokens generated divided by the elapsed time between the output of the first token and the completion of the last token. It should be noted that the adaptive mechanism introduced in constructing the sparsity predictor to reduce additional computational overhead, the delay introduced in the token processing stage is almost negligible compared to the case without the predictor.

6.2. Experimental Results

6.2.1. Cross-Scenario Generalization Capability

Table 1 provides a comprehensive comparison of the performance achieved by different algorithms. To verify that our fine-tuning strategy improves efficiency without introducing accuracy degradation, we first compare OPT-6.7B with LoRa fine-tuning with TrafficLLM (they have comparable number of parameters). Without deployment-side acceleration, the two models demonstrated nearly identical performance across tasks, indicating that the proposed fine-tuning strategy does not compromise accuracy.

Table 1.

Performance of different models on USTC-TFC-2016 and ISCX-VPN-2016.

Building upon this, we further compare OPT-30B (i.e., our proposed large-parameter LLM) with OPT-6.7B. We implement two version of OPT-30B without/with the inference acceleration implementation. Results show that both OPT-30B variants achieve around 80% cross-task accuracy and consistently outperform OPT-6.7B in accuracy by 6–8%, confirming the clear generalization advantage of larger-scale models in downstream tasks.

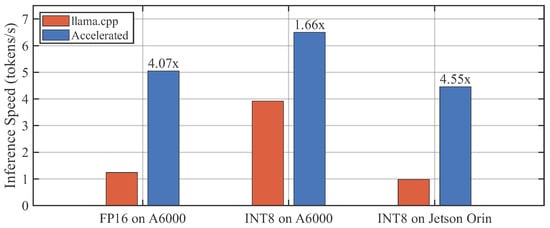

6.2.2. End-to-End Inference Acceleration

Figure 4 illustrates the inference speeds of our proposed approach and the llama.cpp baseline across different platforms and precision settings. We conducted evaluations on both a consumer-grade GPU (i.e., NVIDIA RTX A6000) and an embedded GPU (i.e., NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin).

Figure 4.

Inference speed comparison across different platforms and precision settings.

On the A6000, we first consider the FP16-precision performance. Additionally, considering that both high-performance and embedded scenarios typically employ quantized models to reduce computational and storage overhead at an acceptable level of accuracy loss, and that modern GPUs offer better support for quantized inference, we further quantized the model to INT8 format. This INT8 version was then evaluated on both the A6000 and the Jetson to better simulate real-world deployment conditions.

In terms of the FP16-precision OPT-30B model on the NVIDIA RTX A6000, the optimized inference engine achieves an average generation speed of 5.05 tokens/s, yielding a 4.07× speedup over the llama.cpp baseline.

We then evaluated the INT8 quantized version on the A6000. After quantization, the reduced model size allows the llama.cpp baseline to perform full-GPU inference, which significantly improves its baseline performance. Consequently, the relative acceleration gain of our method decreases in this full-GPU scenario. Nonetheless, the introduction of the predictor mechanism (that reduces computation by predicating active neurons) still ensures our engine maintains a performance advantage. Under INT8 quantization, our proposed inference engine achieves an average generation speed of 6.50 tokens/s on downstream tasks, surpassing the FP16 version. Despite the improved speed, the results in Table 1 show that this quantization introduces only a minor loss in accuracy.

To further validate the method’s portability in a highly resource-constrained scenario, the INT8 model was also evaluated on the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin, an embedded GPU platform. The results show that, despite the limited computational resources of the embedded device, the optimized inference framework achieves a comparable acceleration ratio to that on the RTX A6000, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness and portability in resource-constrained environments.

6.2.3. Ablation Study

The ablation study in this work is conducted from two perspectives: data modality adaptation and inference acceleration.

For data modality adaptation, we replace the complete natural language-like traffic data with two alternative formats: natural language-like data containing only key fields, and raw hexadecimal traffic data. This setting is designed to evaluate the impact of different input preprocessing strategies on model performance. As shown in Table 2, experimental results demonstrate that the model suffers varying degrees of performance degradation after replacing the input modality. This indicates that transforming complete traffic data fields into natural language-like formats, which are more familiar to LLMs, helps preserve semantic integrity and enables the model to better adapt to complex real-world traffic scenarios, thus providing a more robust foundation for downstream tasks.

Table 2.

The Impact of Different Input Preprocessing Strategies on Model Performance. Raw, NL-like (Key Fields), and NL-like (Complete) refer to hexadecimal traffic data, natural language-like traffic data containing only key fields, and natural language-like traffic data containing all available fields, respectively.

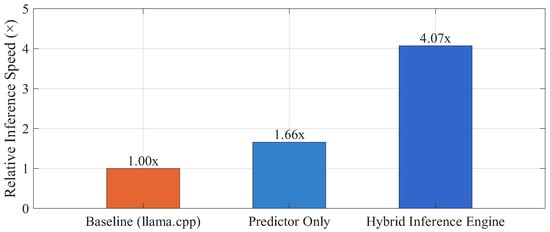

For performance breakdown of inference acceleration, we progressively introduce optimization mechanisms to evaluate their contribution. First, we integrate the predictor into the baseline system (llama.cpp), allowing the model to compute only the activated neurons while still allocating computation at the layer level (i.e., each layer is entirely executed on either GPU or CPU). Under this setting, the OPT-30B model achieves a 1.66× speedup, mainly due to skipping redundant computations on inactive neurons. Further, we introduce a hybrid inference engine on top of this setting, which allows neurons within the same layer to be distributed and computed across GPU and CPU in parallel according to their activation frequency. This mechanism significantly improves GPU utilization and, through optimized GPU–CPU communication and load balancing, achieves a more substantial acceleration of 4.07×. These results demonstrate the efficiency of the hybrid inference engine under constrained hardware resources and provide a feasible pathway for deploying large-scale LLMs in practical scenarios. Figure 5 presents the experimental results for these two stages, showing the speedup achieved at each step of optimization.

Figure 5.

Performance breakdown for each component of our method.

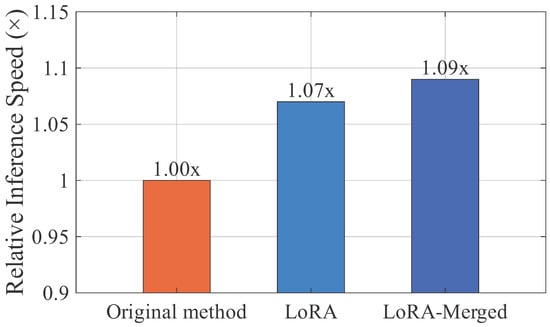

In addition, to further verify the effectiveness of the proposed fine-tuning method, we conducted a comparative analysis between the original and improved approaches. Experimental results show that, under the same model configuration, the improved fine-tuning method achieves approximately a 9% improvement in inference efficiency, confirming its advantage in low-latency scenarios. Even without merging the adapter weights, the low-rank adaptation mechanism of LoRA performs computation only on low-dimensional supplements to the original weights, resulting in about a 7% improvement in inference efficiency. In contrast, the original method inserts prefix vectors into each layer, which must be provided as additional inputs during inference. This introduces notable computational and memory overhead for larger models, increases deployment complexity, and reduces inference efficiency. Figure 6 shows the relative inference speed comparison between the original and improved fine-tuning strategies, highlighting the acceleration achieved by LoRA. Furthermore, As shown in Figure 7, LoRA updates only 37.5% of the trainable parameters required by the original method, yet achieves comparable performance, improving parameter efficiency and reducing overall training time by approximately 15%. In summary, the modified fine-tuning approach maintains model performance while significantly improving fine-tuning efficiency and providing lower-latency, lower-overhead inference.

Figure 6.

Relative inference speed comparison of different fine-tuning strategies.

Figure 7.

Trainable parameters comparison of different fine-tuning strategies.

6.2.4. Predictor Overhead

We also evaluated the accuracy error introduced by the online predictor during inference, as shown in Table 3. The results indicate that the predictor inevitably introduces a small amount of error in neuron activation prediction, leading to slight deviations in the inference results. However, in terms of overall performance, the introduction of the predictor effectively skips a large number of unnecessary neuron computations, substantially reducing computational redundancy during inference. Therefore, even with a small amount of prediction error, the speedup benefits brought by the predictor remain significant, providing feasible support for the efficient deployment of large-scale models under resource-constrained environments.

Table 3.

Impact of the online predictor on model performance.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes a method integrating LLM adaptation modeling with inference acceleration to address the accuracy and efficiency challenges of network traffic analysis in complex environments. The approach designs a traffic-to-text mapping and instruction-based modeling strategy, combines parameter-efficient fine-tuning (LoRA), and employs hot–cold neuron partitioning with dynamic prediction for GPU–CPU hybrid inference. Experimental results show that the proposed method significantly improves inference efficiency with minimal accuracy loss, demonstrating strong adaptability in resource-constrained settings and feasibility for consumer-grade deployment. This not only overcomes the bottlenecks of high cost and low efficiency in applying LLMs to network security, but also validates their feasibility and advantages in network traffic analysis tasks. Future research may further explore more efficient neuron selection strategies and assess adaptability on larger-scale and more diverse traffic datasets, thus promoting the deployment of LLMs in real-world network security defense systems.

Author Contributions

X.W.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation; Z.W.: resources, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; D.C.: software, validation, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation; L.Y.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the science and technology project of State Grid Corporation of China: Research on Key Technologies and Equipment Development for Cybersecurity Protection of Power Monitoring Systems under the New Situation (Grant No. 5700-202417382A-3-2-ZX).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the respective public repositories. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: USTC-TFC-2016: https://github.com/davidyslu/USTC-TFC2016.git (accessed on 19 March 2025); ISCX-VPN-2016: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/vpn.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xinsheng Wei is employed by the company Nanjing NARI Information and Communication Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China. Author Zhihua Wang is employed by the company State Grid Shanghai Electric Power Company, Shanghai, China. The authors declare that this study received funding partially from the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Ede, T.V.; Bortolameotti, R.; Continella, A.; Ren, J.; Dubois, D.J.; Lindorfer, M.; Choffnes, D.R.; van Steen, M.; Peter, A. FlowPrint: Semi-Supervised Mobile-App Fingerprinting on Encrypted Network Traffic. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2020, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2020; The Internet Society: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, V.F.; Spolaor, R.; Conti, M.; Martinovic, I. Robust Smartphone App Identification via Encrypted Network Traffic Analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, L.; Xiong, G.; Cao, Z.; Li, Z. FS-Net: A Flow Sequence Network For Encrypted Traffic Classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, INFOCOM 2019, Paris, France, 29 April–2 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Xu, K.; Du, X. Accurate Decentralized Application Identification via Encrypted Traffic Analysis Using Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 2367–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, T.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Chen, M.; Yin, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. TrafficLLM: Enhancing Large Language Models for Network Traffic Analysis with Generic Traffic Representation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerganov, G. ggerganov/llama.cpp: Port of Facebook’s LLaMA model in C/C++. GitHub Repository. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ggerganov/llama.cpp (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Liu, X.; Du, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lai, H.; Ding, M.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, W.; Xia, X.; et al. GLM-130B: An Open Bilingual Pre-trained Model. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023; OpenReview.net: Alameda, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2022, Virtual Event, 25–29 April 2022; OpenReview.net: Alameda, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, V.; Landauer, M.; Wurzenberger, M.; Skopik, F.; Rauber, A. SoK: LLM-based Log Parsing. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.04877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Kiran, M.; Ebling, D.; Breen, J. OFCnetLLM: Large Language Model for Network Monitoring and Alertness. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Shi, L.; Ding, M.; Nguyen, D.C.; Tan, W.; Weng, J.; Han, Z. Federated Learning in Intelligent Transportation Systems: Recent Applications and Open Problems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 3259–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Shi, L.; Wei, K.; Mei, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J. When MoE Meets Blockchain: A Trustworthy Distributed Framework of Large Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.; Danezis, G. k-fingerprinting: A Robust Scalable Website Fingerprinting Technique. In Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 16, Austin, TX, USA, 10–12 August 2016; Holz, T., Savage, S., Eds.; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 1187–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Xiong, G.; Gou, G.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Yu, J. ET-BERT: A Contextualized Datagram Representation with Pre-training Transformers for Encrypted Traffic Classification. In Proceedings of the WWW ’22: The ACM Web Conference 2022, Virtual Event, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; Laforest, F., Troncy, R., Simperl, E., Agarwal, D., Gionis, A., Herman, I., Médini, L., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y.; Yang, Z.G.; Chen, X.N. PERT: Payload Encoding Representation from Transformer for Encrypted Traffic Classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 ITU Kaleidoscope: Industry-Driven Digital Transformation, Kaleidoscope, Ha Noi, Vietnam, 7–11 December 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; Bosma, M.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; et al. Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Li, Q.; Xu, K. Detecting Unknown Encrypted Malicious Traffic in Real Time via Flow Interaction Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, NDSS 2023, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 February–3 March 2023; The Internet Society: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, W. A Survey on Model Compression for Large Language Models. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 1556–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Fang, G.; Wang, X. LLM-Pruner: On the Structural Pruning of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, NeurIPS 2023, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frantar, E.; Alistarh, D. SparseGPT: Massive Language Models Can be Accurately Pruned in One-Shot. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2023, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 10323–10337. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Dong, P.; Cheng, K. LLM-FP4: 4-Bit Floating-Point Quantized Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Oguz, B.; Zhao, C.; Chang, E.; Stock, P.; Mehdad, Y.; Shi, Y.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Chandra, V. LLM-QAT: Data-Free Quantization Aware Training for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, Virtual Meeting, 11–16 August 2024; Ku, L., Martins, A., Srikumar, V., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Huang, M. MiniLLM: Knowledge Distillation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Waheed, A.; Zhang, C.; Abdul-Mageed, M.; Aji, A.F. LaMini-LM: A Diverse Herd of Distilled Models from Large-Scale Instructions. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), St. Julian’s, Malta, 17–22 March 2024; pp. 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yu, C.H.; Gonzalez, J.; Zhang, H.; Stoica, I. Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention. In Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, SOSP 2023, Koblenz, Germany, 23–26 October 2023; Flinn, J., Seltzer, M.I., Druschel, P., Kaufmann, A., Mace, J., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA TensorRT-LLM: A Library for Optimizing Large Language Model Inference. GitHub Repository. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/NVIDIA/TensorRT-LLM (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Song, Y.; Mi, Z.; Xie, H.; Chen, H. PowerInfer: Fast Large Language Model Serving with a Consumer-grade GPU. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 30th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, SOSP 2024, Austin, TX, USA, 4–6 November 2024; Witchel, E., Rossbach, C.J., Arpaci-Dusseau, A.C., Keeton, K., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantar, E.; Ashkboos, S.; Hoefler, T.; Alistarh, D. GPTQ: Accurate Post-Training Quantization for Generative Pre-trained Transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.17323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Jeong, J.S.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Chun, B. Orca: A Distributed Serving System for Transformer-Based Generative Models. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, OSDI 2022, Carlsbad, CA, USA, 11–13 July 2022; Aguilera, M.K., Weatherspoon, H., Eds.; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 521–538. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Zeng, X.; Ye, X.; Sheng, Y. Malware traffic classification using convolutional neural network for representation learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Networking, ICOIN 2017, Da Nang, Vietnam, 11–13 January 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper-Gil, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of Encrypted and VPN Traffic using Time-related Features. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, ICISSP 2016, Rome, Italy, 19–21 February 2016; Camp, O., Furnell, S., Mori, P., Eds.; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2016; pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 140:1–140:67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).