Abstract

We develop a comprehensive dynamic Walrasian framework entirely in so that prices and allocations are essentially bounded, and market clearing holds pointwise almost everywhere. Utilities are allowed to be locally Lipschitz and quasi-concave; we employ Clarke subgradients to derive generalized quasi-variational inequalities (GQVIs). We endogenize inventories through a capital-accumulation constraint, leading to a differential QVI (dQVI). Existence is proved under either strong monotonicity or pseudo-monotonicity and coercivity. We establish Walras’ law, and the complementarity, stability, and sensitivity of the equilibrium correspondence in -metrics, incorporate time-discounting and uncertainty into , and present convergent numerical schemes (Rockafellar–Wets penalties and extragradient). Our results close the “in mean vs pointwise” gap noted in dynamic models and connect to modern decomposition approaches for QVIs.

Keywords:

Walrasian dynamic competitive equilibrium; (generalized) quasi-variational inequalities; weak-∗ compactness; Clarke subgradients; differential QVI; stability; numerical schemes MSC:

91B50; 90C33; 47J20; 49J52

1. Introduction

The variational inequality (VI/QVI/GQVI) approach to competitive equilibrium (see, e.g., [1] and references therein) is a practical alternative to fixed-point methods [2,3,4]. In dynamic models (), however, feasibility is encoded by integrals, so one usually obtains only clearing in mean. This leaves open two questions: do markets clear a.e. in time, and does complementarity hold pointwise? We answer both by working in . Our framework delivers a.e. clearing and complementarity and still handles locally Lipschitz, quasi-concave utilities, inventory dynamics with discounting, uncertainty, and provably convergent algorithms.

is a natural setting in continuous time: (i) prices and consumptions are bounded; (ii) budgets use the - pairing; and (iii) the price simplex is weak-∗ compact (Banach–Alaoglu). This compactness yields existence without extra compactifications. Testing against simple prices then turns integral inequalities into pointwise complementarity and produces a.e. clearing.

We organize our main results around seven themes that advance the dynamic Walrasian VI/QVI/GQVI literature:

- (C1)

- Functional setting in . Prices and allocations live in ; the price set is a weak-∗ compact simplex and budget sets are weak-∗ compact bands. The existence of equilibrium follows without additional price compactifications, and we obtain a.e. market clearing and complementarity by a simple-function testing argument.

- (C2)

- From “in mean” to a.e. clearing. We prove that solutions of the master VI against the convex hull of simple price functions imply and a.e. for each good j. This closes the gap noted in dynamic models where only integral clearing was available.

- (C3)

- Nonsmooth utilities and GQVI. Allowing locally Lipschitz, quasi-concave instantaneous utilities, we formulate household optimality via generalized Vi using Clarke subgradients, relying on measurable selection theorems to obtain measurable subgradient selections and well-posedness of the generalized VI.

- (C4)

- Production, stockpiling, and dQVI. We introduce inventories through linear capital accumulation with depreciation and show that the joint household–firm–inventory system admits an equilibrium characterized as a differential QVI (dQVI).

- (C5)

- Qualitative properties. Under strong monotonicity (in an metric) or under pseudo-monotonicity with coercivity, we prove existence; with strong monotonicity we derive Lipschitz stability of the equilibrium correspondence and Walras’ law. These provide regularity and sensitivity results in the spirit of stability analyses for dynamic price VIs.

- (C6)

- Numerics. We give implementable schemes: Rockafellar–Wets penalty methods to enforce budgets and Korpelevich’s extragradient for the monotone GVI. Under strong monotonicity, we prove linear convergence; in the merely monotone case we obtain ergodic rates. A detailed dynamic Cobb–Douglas example (single- and multi-good) illustrates closed forms, a price fixed-point map, and discretized extragradient updates.

- (C7)

- Scalability. After time discretization the GQVI decomposes by agents and time slabs. We outline a Dantzig–Wolfe-type master/worker decomposition that aligns with contemporary QVI decomposition frameworks, enabling large-scale computations.

Our analysis builds on and sharpens a line of results that positioned dynamic equilibria within VI/QVI theory. Time-dependent Walrasian formulations and computational procedures were developed for continuous time in variational form (e.g., [5,6,7,8,9,10]), and quasi-variational models for quasi-concave preferences were advanced in [11,12]. Conceptual remarks on Lebesgue-space modeling and the limitations of mean-value clearing appear in [13,14]. Regularity and sensitivity for dynamic price VIs (e.g., [15]) highlighted the importance of monotonicity and stability. On the nonsmooth side, generalized subdifferential tools and measurable selection techniques (e.g., [16,17,18]) allow us to treat locally Lipschitz, quasi-concave utilities in a dynamic GQVI form, complementing the static analyses in [11,12]. For the “evolution” and stability viewpoint, we connect to recent work on equilibrium evolution and stability properties [19]. Algorithmically, we lean on classical extragradient methods [20] and penalty approaches [17], and relate our decomposition discussion to recent QVI master/worker architectures (see, e.g., [21]).

Methodologically, we rely on three devices: weak-∗ compactness in (for price and band compactness), Mosco convergence of budgets under price changes (for stability of household solutions and continuity of excess demand), and testing against simple prices (to pass from integral inequalities to pointwise complementarity via Lebesgue differentiation). Together, these give a.e. clearing without extra compactifications or restrictive price dynamics. For nonsmooth utilities we adopt Clarke subdifferentials with measurable selections, enabling generalized VI statements while retaining monotonicity (or pseudo-monotonicity) needed for existence and stability.

Conceptually the novelties can be so summarized: (i) our formulation delivers a.e. clearing and complementarity in continuous time, closing the “in mean vs a.e.” gap for dynamic Walrasian models; (ii) we integrate inventories and stockpiling explicitly via a differential law within a QVI system; (iii) we accommodate locally Lipschitz, quasi-concave utilities and still provide existence and regularity; (iv) we provide constructive, convergent numerical schemes with rates under strong monotonicity; and (v) we connect the theory to scalable decomposition architectures for large agent/time systems.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we place our contribution in the variational context on the competitive equilibrium, clarifying how an formulation changes the economic meaning of feasibility and prices relative to approaches and why almost-everywhere clearing naturally enters the picture. Section 3 then assembles the analytic ingredients that make this perspective workable: topology for prices and allocations, weak-∗ compactness of band sets, continuity of the – pairing, Mosco stability of budgets as prices vary, and the basic measurability needed for Clarke selections. Building on this foundation, Section 4 lays out the economic environment as a single variational object: banded consumption sets and budget hyperplanes for households, box-type production (when present), and, in the dynamic setting, a linear stock law that ties production, consumption, and inventories together. With the model in place, Section 5 develops the core implications of the framework: equilibrium is obtained from a master variational inequality, integral balance is converted into pointwise clearing and complementary slackness by testing with simple prices, robustness is articulated through stability of allocations with respect to prices, and the dynamic and stochastic extensions are treated within the same operator viewpoint. Section 6 develops the computational side of the framework, introducing time discretization and projection/proximal updates, analyzing extragradient and primal–dual splitting with practical stepsize rules (fixed and adaptive), and reporting convergence behavior (ergodic decay in the monotone regime and linear contraction under stronger curvature), together with brief remarks on mesh dependence and per-iteration complexity. Section 7 presents stylized numerical illustrations—first an exchange economy without inventories and then a dQVI with a stock variable—showing how the framework yields almost-everywhere clearing and pointwise complementarity in practice, and how the proposed algorithms behave under discretization. In Section 8, we distill the analytic results into an implementation guide, indicating what data are needed, how to set bounds and stepsizes, and how to interpret the diagnostics in empirical or operational settings. Section 9 closes by reflecting on scope and limitations, highlighting when the choice is economically essential and outlining directions where the same perspective could be extended, for example, to richer technologies, market designs, or learning-based estimation of primitives.

2. Literature Overview

To situate our contribution within the VI/QVI/GQVI literature on competitive equilibrium, we group works by methodological theme and indicate how our framework advances each line.

- (L1)

- Variational formulations of equilibrium. Casting equilibria as VIs/QVIs has roots in classical monotone operator theory and variational analysis; see, among others, [17,22,23]. In the exchange setting, Jofre et al. in [22] formulated price determination as a VI on a convex feasible set, opening a path beyond fixed-point methods. Our analysis follows this route but works entirely in and moves from integral feasibility to pointwise (a.e.) complementarity.

- (L2)

- Time-dependent/dynamic Walrasian models. For continuous-time markets, Maugeri and Vitanza in [5] and the series [6,7,8,9,10] developed evolutionary VI/QVI formulations with prices and allocations in Lebesgue spaces, typically obtaining clearing in mean. These papers established existence and computational procedures under various monotonicity assumptions. Our contribution complements this line by proving existence in and converting the master VI into a.e. complementarity through a simple-function testing device, thereby closing the “in mean vs a.e.” gap.

- (L3)

- Quasi-concavity, quasi-variational inequalities, and nonsmooth utilities. Allowing quasi-concave utility weakens convexity and naturally leads to QVIs; see [11,12]. Dynamic settings with locally Lipschitz utilities require generalized subdifferentials; we rely on Clarke calculus and measurable selections (cf. [16,17,18]) to formulate household optimality as a generalized VI (GVI) in continuous time. This bridges static QVI treatments with dynamic, nonsmooth preferences (see also [24]).

- (L4)

- Lebesgue-space modeling and the role of . Conceptual remarks on choosing Lebesgue spaces for dynamic equilibrium and consequences for feasibility appear in [13,14]. When for , price sets are not compact and clearing emerges only in integral form. By placing prices and consumptions in , we exploit weak-∗ compactness (Banach–Alaoglu) and obtain a.e. clearing via testing on indicator-price simple functions. This shift is the cornerstone of our existence and complementarity results.

- (L5)

- Contrasting with dynamic equilibrium models. A central distinction between our framework and prior dynamic Walrasian models lies in the choice of function space for prices and allocations. The influential series by Donato, Milasi, and Vitanza [7,8,9,10] formulates equilibrium in settings (), where feasibility and market clearing are enforced in integral form—typically yielding clearing in mean. However, spaces lack weak-∗ compactness, and price sets are not closed under pointwise convergence, which complicates existence proofs and limits the granularity of complementarity conditions. By contrast, our framework leverages Banach–Alaoglu compactness and simple-function testing to achieve almost-everywhere (a.e.) clearing and complementarity. This shift enables pointwise Walras’ law, strong stability results, and a direct formulation of household optimality as a GVI, marking a conceptual and technical advance over -based approaches.

- (L6)

- Production, stockpiling, and dynamic constraints. Production and inventories can be incorporated into dynamic Walrasian models through time-dependent constraints and state equations. Variational formulations for time-dependent equilibria are surveyed in [5]. We formalize inventories through a linear capital-accumulation law with depreciation and derive a differential QVI (dQVI), extending the exchange-only formulations in [8,9,10].

- (L7)

- Stability, sensitivity, and evolution. Regularity and sensitivity for price-based dynamic VIs are treated in [15]. The broader stability/evolution viewpoint for equilibria has been advanced in [19], which studies how equilibria vary under perturbations and in time. In our framework, strong monotonicity (in an metric) yields Lipschitz dependence of optimal allocations on prices and leads to stability of the aggregate excess map. We also provide a pointwise Walras’ law in the setting.

- (L8)

- Stochasticity, discounting, and measurability. Discounting is standard in intertemporal utility and integrates seamlessly in VI formulations (e.g., [8]). For uncertainty on , measurability issues are handled through Komlós-type subsequences and measurable selections [18,25]. We extend existence and a.e. clearing to the product space, obtaining pointwise complementarity in .

- (L9)

- Computational methods. Early computational procedures for time-dependent Walrasian VIs are discussed in [6]. For monotone operators on convex sets, the extragradient method [20] is a robust baseline, while penalty methods provide a principled way to enforce budget and complementarity constraints [17]. We analyze both in our model and establish linear convergence under strong monotonicity and ergodic rates in the merely monotone case. Our dynamic Cobb–Douglas example offers closed forms and a price fixed-point iteration that is readily discretized.

- (L10)

- Operator-splitting and primal–dual algorithms (compatibility). The –weak-∗ formulation is compatible with contemporary splitting schemes such as PDHG/Chambolle–Pock, mirror-prox, and ADMM [26,27,28,29]. Two features are decisive: (i) all feasibility pieces (bands, production boxes, price simplex) are convex sets with simple prox/projection operators (pointwise in time); and (ii) the linear state map separates cleanly from the nonsmooth parts, enabling primal–dual updates with diagonal preconditioning. As a result, the same sublinear ergodic gap decay (monotone case) and linear rates under strong curvature/monotonicity extend to the present framework after discretization, while the economic gains of weak-∗ compactness (existence and a.e. complementarity) are retained. Operational details (prox operators, stepsize rules, and a saddle formulation) are summarized in Section 6 and Section 8.

- (L11)

- Decomposition and scalability. Network and decomposition ideas for equilibrium computation have a long pedigree (e.g., [30,31,32]). The rise of QVI decomposition is pushing scalability to large agent/time systems; see [21] for a recent Dantzig–Wolfe style architecture for QVIs. After time discretization, our GVI/GQVI separates by agents and time slabs, enabling master–worker price updates and parallel household subproblems, consistent with these decomposition paradigms.

- (L12)

- Recent operator-splitting and primal–dual algorithms. Beyond classical extragradient and penalty methods, recent advances in operator-splitting (e.g., [27,28]) and primal–dual schemes (e.g., [26,29]) offer scalable solvers for monotone inclusions and saddle-point problems. These methods are particularly suited to large-scale, time-discretized GVI/GQVI systems. While our focus is on existence and structure, the decomposition architecture we propose is compatible with these modern algorithms, and our companion paper explores their application to dynamic equilibrium computation.

The use of as the basic function space is not only a mathematical device (to gain weak-∗ compactness of bands) but also carries economic meaning. Boundedness of consumption and production streams corresponds to technological, physical, or policy limits that prevent agents from consuming or producing without bound. In contrast, models based on with permit unbounded spikes in consumption at negligible measure sets; while analytically convenient in reflexive cases, such spikes are economically implausible if one insists on feasibility at every instant. Thus the framework better matches markets where resources are capped in real time.

Pointwise complementarity also has a direct interpretation. At almost every , if the price of good j is strictly positive, then the market for good j clears exactly at that state and time; conversely, if there is excess supply of good j at , the equilibrium price of that good must vanish there. In practical terms, this means that positive prices serve as indicators of binding scarcity, while goods that are freely available carry zero price. This condition extends the classical notion of market clearing to a pathwise, almost-everywhere statement, aligning with real-time operation in electricity, network, or financial markets where feasibility must hold continuously rather than only in expectation.

In short, the –based formulation preserves existence while delivering a.e. clearing and pointwise complementarity, extends to inventories (dQVI) and uncertainty on product spaces, provides parametric stability of allocations with respect to prices, and admits implementable first-order algorithms (extragradient and primal–dual splitting) with standard rates after discretization.

3. Preliminaries

In this section we collect basic facts on weak-* compactness in , Mosco convergence of budget sets, measurable Clarke subgradients, and a simple testing principle for a.e. inequalities.

3.1. Notation

For and the duality pairing is . For we write (an metric used for stability). For a measurable multifunction , .

3.2. Weak-∗ Compactness of Bands

Lemma 1 (Bands are weak-∗ compact).

Let and . Then X is convex, weak-∗ closed, and weak-∗ compact in .

Proof.

Convexity and weak-∗ closedness are immediate. Since on X, weak-∗ compactness follows from the Banach–Alaoglu theorem [33]; see also ([34], Thm. 5.116) for the case. □

3.3. Mosco Convergence of Budget Sets in

Lemma 2 (Mosco convergence of budget half-spaces).

Fix agent a. Let in and set . Then in the sense of Mosco: (i) (inner limit) for any there exist with in ; (ii) (outer limit) if and , then .

Proof.

(i) If , then for k large, so choose . If , pick with (possible because ), and set . Then and . This is a standard application of Mosco convergence of convex sets [16] together with epi/Painlevé–Kuratowski limits for half-spaces ([17], Chs. 11–12). (ii) follows from and by bilinearity and in , while in . □

Remark 1.

As prices in , the linear budget inequality defines half-spaces that “tilt” continuously in the weak-∗ geometry of the band : if a plan x is feasible at p, nearby prices keep it feasible up to an arbitrarily small rescaling, and any weak-∗ limit of feasible plans at remains feasible at p. Equivalently, the admissible region varies in a way that preserves both inner feasibility (you can approximate feasible points) and outer closure (limits of feasible plans stay feasible), which is exactly the content of Mosco convergence.

Lemma 3 (Budget sets are weak-∗ closed and compact in bands).

Fix an agent a and . Let with , and .

Then is weak-∗ closed in ; consequently, is weak-∗ compact (as a weak-∗ closed subset of the weak-∗ compact band ).

Proof.

Let and suppose in . By definition of weak-∗ convergence, for every , . In particular, with the fixed and the fixed ,

Since for all k, passing to the limit gives ; hence, . Thus, is weak-∗ closed. Weak-∗ compactness then follows because is weak-∗ compact by Lemma 1 and is weak-∗ closed. □

Lemma 4 (Joint continuity of the – pairing under mixed limits).

Let with in , and let with in . Fix . Suppose moreover that is uniformly essentially bounded, e.g., for some . Then

Proof.

Write

For , Hölder’s inequality and uniform boundedness give

since in . For , weak-∗ convergence means precisely that for every ; taking yields . Hence, . □

Corollary 1 (Continuity of budgets along mixed perturbations).

Let in and with . If each , then . In particular, the graph is closed under the product topology on bounded sets.

Proof.

Apply Lemma 4 with to get . Since for all k, the limit yields , i.e. . □

3.4. Measurable Clarke Selections

Lemma 5 (Measurable subgradient selection).

Let be such that is measurable and is locally Lipschitz for a.e. t. Then there exists a jointly measurable selection .

Proof.

For a.e. t, the Clarke subdifferential is a nonempty compact convex set-valued map with closed graph ([35], Ch. 2). The measurability of and existence of a jointly measurable selection follow from the Castaing representation theorem and measurable selection theorems ([18], Ch. III); see also ([36], Prop. 8.2.4). □

Proposition 1 (Clarke selections: joint measurability and integrability).

Let satisfy (U1) (Carathéodory: measurable in t, locally Lipschitz and quasi-concave in x a.e.) and (U2) (growth): there exist and such that for a.e. t and all x, every obeys . Let with . Then:

- (i)

- (Joint measurability) There exists a jointly measurable map with for a.e. .

- (ii)

- (Integrability along measurable selections) For any measurable ,Consequently, with discounting , and, for any ,

Proof.

We prove each statement separately.

- (i)

- For a.e. t, is nonempty, compact, convex, and has a closed graph ([35], Ch. 2). The map is measurable (its graph is measurable) and admits a Castaing representation; hence, a jointly measurable selection exists by standard measurable selection theorems ([18], Ch. III); see also ([36], Prop. 8.2.4).

- (ii)

- The growth bound and a.e. give , which yields the stated estimates. Discounting preserves integrability.

□

3.5. Simple-Function Testing and a.e. Inequalities

Lemma 6 (Testing by simple functions implies a.e. inequality).

Let . If for every measurable , then a.e.

Proof.

If had a positive measure, then , contradicting the hypothesis. This is a standard measure-theoretic fact; see, e.g., ([37], Prop. 2.25). □

We test the master VI with simple prices: an indicator of a measurable set times a simplex vertex. This choice stays inside the price simplex. The test converts the integral inequality into a setwise inequality on every measurable set. By the differentiation lemma, setwise inequality implies a pointwise statement almost everywhere. We then localize a small mass from a positive price coordinate to the others. This localization forces complementary slackness at points where that price stays positive. The steps are elementary and do not require density arguments beyond simple functions in .

Example 1.

Fix a good and a measurable set . Consider the simple price

Let . Plugging q into the master VI at gives

Since this holds for every measurable E, Lemma 6 yields a.e. on . Moreover, by repeating the argument with the localized mass shift on (see the “From the master VI to a.e. clearing and complementarity” paragraph), we obtain a.e. on , i.e., a.e.

3.6. From the Master VI to a.e. Clearing and Complementarity

Recall the master VI at equilibrium prices :

where and write .

- (i)

- Pointwise (a.e.) clearing. Fix a good and a measurable set . Define the testing priceThen (nonnegative coordinates, and a.e.). Plugging in the master VI givesSince this holds for every measurable E, Lemma 6 yields a.e. on .

- (ii)

- Complementarity on . Fix j and , and set . For small, define the mass-shift perturbationThen (we only redistribute a small -mass among coordinates on and keep the pointwise sum equal to 1). Using the master VI with ,Because a.e. (aggregate excess is the sum across goods), the integrand equals . HenceCombining with part (i), we obtain . Applying Lemma 6 on yieldsFinally, letting gives a.e. on , i.e., the a.e. complementary slackness .

- (iii)

- Measurability and density facts used. The constructions and are measurable and belong to by definition (they use measurable indicators and measurable ).No weak-∗ density is needed for (i)–(ii) because these qs are already in . If approximations are required elsewhere, we only use that simple functions are -dense in each component of p, and our pairing is .

Testing with gives a.e.; localized mass shifts on force a.e. where , i.e., a.e. market clearing and complementarity.

4. Model

In this section we specify the continuous-time environment, define the weak-* compact price simplex and agents’ band-type consumption sets in , introduce discounted (possibly nonsmooth) utilities, and formulate the agent problem as a generalized variational inequality.

4.1. Notation and Conventions

Agents are indexed by subscripts , so denotes agent a’s consumption plan. Goods/components are indexed by parenthesized superscripts , so the jth component is ; analogously, , , and . Time/state arguments are written as (deterministic time) or (stochastic). Aggregate excess for good j is , and denotes the – dual pairing. Prices lie in (or in the stochastic case). Throughout, “component j” always uses the superscript notation , while agent indexing always uses the subscript a. All previous occurrences of or (for goods) have been harmonized to and , respectively.

4.2. Time

Let with , endowed with the Lebesgue –algebra and measure. For , we write for essentially bounded measurable functions , with positive cone . The dual pairing between and is

Unless otherwise stated, is equipped with its weak-∗ topology . For measurable, denotes the indicator of E.

4.3. Price Simplex

Prices are bounded, nonnegative processes that satisfy the pointwise normalization

We define the price simplex

Then is nonempty, convex, and weak-∗ compact. We will also use the set of simple prices , where are the canonical basis vectors of ; is dense in for testing purposes.

4.4. Agents, Endowments, and Consumption Sets

There are agents . Each agent a is endowed with an endowment stream and satisfies the survivability condition

Feasible consumptions for agent a are bounded nonnegative processes in a closed band

where is a given componentwise cap. By construction, is convex and weak-∗ compact.

4.5. Budget Sets

Given a price , the (intertemporal) budget set of agent a is

Thus, is a weak-∗ closed subset of , and hence, weak-∗ compact. The aggregate feasible set is .

4.6. Utility Functions and Discounting

For each a, the instantaneous utility satisfies:

- (U1)

- (Carathéodory) For every , is measurable; for a.e. , is locally Lipschitz and quasi-concave.

- (U2)

- (Growth) There exist and such that for a.e. t, every Clarke subgradient satisfies .

Given a discount rate , the intertemporal utility functional is

Under (U1)–(U2) and boundedness of , is well-defined and upper semicontinuous on for the weak-∗ topology.

For stability and numerics, we employ the following monotonicity condition expressed via Clarke selections: there exists such that for a.e. t and all ,

4.7. Agent Optimization Problem

Given , agent a solves

By weak-∗ compactness of and upper semicontinuity of on , there exists at least one solution . Using Proposition 1, fix a jointly measurable selection ; then for any measurable , the process belongs to , so the generalized VI below is well-defined. Using Clarke’s generalized gradient, first-order optimality is equivalent to the generalized variational inequality

for some measurable selection .

Remark 2.

The individual problem (5) may be equivalently expressed by KKT conditions with multipliers. For agent a, let denote the multipliers for the constraints and , and let be the scalar multiplier for the budget constraint . Then at an optimal there exist such multipliers with:

Thus, whenever hits its upper bound , the corresponding component of may become positive and the effective marginal condition balances the utility subgradient, the budget shadow price, and this upper-band multiplier. This makes it explicit how solutions behave when upper bounds are active.

For stacking agents, let and . Then (5) is the product-space GVI:

Under (3) with , the GVI on has a unique solution; under mere monotonicity with the band constraints , existence still holds.

5. Main Results

5.1. Equilibrium Notion

Definition 1 (Dynamic competitive equilibrium in ).

A pair is a dynamic competitive equilibrium if:

- (i)

- for each a, maximizes on ;

- (ii)

- a.e. market clearing and complementarity hold; that is [38,39]:

5.2. Standing Monotonicity Hypotheses

Let for measurable selections . Assume:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Strong monotonicity (in ): there is s.t.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Pseudo-monotonicity and coercivity: Ξ is pseudo-monotone on and coercive in , i.e., along any sequence within X.

With the primitives, feasible sets, and the equilibrium notion in place, we proceed to the main results: existence, the testing-by-simple-prices principle yielding a.e. clearing and complementarity, and stability properties.

5.3. Existence and a.e. Clearing

Theorem 1.

Assume the data as above and either (H1) or (H2) . Then there exists which is a dynamic competitive equilibrium in the sense of Definition 1 ([40]).

Idea of the Proof.

We sketch the mechanism and defer the full argument to Appendix A.1. Baseline control and stability of feasible sets are provided by Lemmas 1 and 2. These bounds yield compactness for approximate price–allocation sequences and stability of the associated normal cones. Lemma 5 furnishes a measurable subgradient selection compatible with the Clarke-type GVI, allowing the extraction of limit candidates that preserve feasibility and the variational inequalities. Finally, Lemma 6 upgrades integrated inequalities to a.e. statements on , establishing market clearing, complementarity, and Walras’ law. The formal construction of measurable selections, the Mosco verification, diagonal subsequences, and the a.e. upgrade are detailed in Appendix A.1. □

Existence alone does not quantify robustness. We therefore study how equilibria respond to price perturbations.

5.4. Walras’ Law

Proposition 2.

Let be an equilibrium. Then for every a,

Proof.

Since we have . Summing over a and using a.e. with complementary slackness gives , whence each term must be 0 because budgets bind only when marginal utility is positive (which holds a.e. on supports by Lipschitz positive directional derivatives at the boundary and survivability). □

5.5. Dynamic Production and Stocks (dQVI)

The exchange model is a special case. We now introduce production and inventories via a linear state equation; this augments feasibility while keeping the variational structure intact.

Introduce stocks with , depreciation , production , and linear technology set (nonempty, convex, closed). Dynamics:

Firms choose to maximize .

Example 2.

Fix a measurable cap and consider the time-separable production set

Given (equilibrium) prices , the firm solves the convex program

VI form. The maximizer is characterized by the variational inequality

i.e., solves [41]. Since is nonempty, convex, and closed in , a solution exists.

KKT conditions. Equivalently, there exist multipliers such that, for a.e. t,

Here (8) is stationarity, (9) complementary slackness, and (10) feasibility. The pointwise box structure of makes these conditions necessary and sufficient for optimality.

Closed-form solution (componentwise). Because and a.e., the objective is increasing in each . Hence, the unique optimal choice (up to null sets where prices vanish) is

Equivalently, one may pick the canonical representative . The corresponding multipliers satisfy

which makes (8)–(10) hold componentwise.

Remark 3.

In the full dQVI with the inventory law , the y-choice interacts with k through the state constraint; the VI form (7) is then embedded in the product-space VI with additional multipliers for the linear dynamics (see Definition 2). The box-KKT above is precisely the y-block of that system when is of box type.

5.6. dQVI: State Operator, Feasible Set, and Operator

Let l be the number of goods. For and measurable , define the linear state operator

and the aggregate balance

Given prices , the dQVI feasible set is

Here is a nonempty, convex set of admissible productions.

Fix Carathéodory utilities satisfying (U1)–(U2) and let be the jointly measurable Clarke selection provided by Proposition 1. Define the operator

acting on the product space

where the x-block has n components, the y-block is one l-vector process, and the k-block is l-vector but appears only via the feasible set constraints (, , ).

Definition 2 (dQVI at fixed p; primal form).

Given , a triple solves the differential QVI if

for all , with the same Clarke selections along as above.

Remark 4.

We note that for fixed p, the dQVI is a (generalized) VI on the convex set ; the quasi-feature comes from the price selection which is determined simultaneously via the price VI. Moreover, the linear state equation is enforced in the feasible set; equivalently, one may write the KKT system by introducing a Lagrange multiplier for and the normal cone for . We keep the primal form for clarity.

Definition 3 (Walrasian equilibrium for the dQVI model).

Let be the price simplex, and let be the dQVI feasible set from above. A quadruple is a Walrasian dQVI equilibrium if:

- (i)

- (Households) For each agent a, there exists a measurable selection such thatwhere .

- (ii)

- (Firms) maximizes revenue at :

- (iii)

- (Prices/master VI) With aggregate excess ,

Remark 5.

The constraints can be interpreted as follows. First, the band constraint reflects technological or policy-imposed consumption limits. Second, the budget inequality expresses that the value of purchases cannot exceed the value of the endowment at prices p. Third, the production constraint restricts feasible outputs (e.g., upper capacity bounds). Fourth, the stock dynamics capture the physical law of inventory accumulation. Finally, nonnegativity encodes the physical impossibility of negative consumption, output, or inventories.

Assumption 1.

Assume:

- (i)

- (Utilities) (U1) – (U2) hold and either (H1) (strong monotonicity in ) or (H2) (pseudo-monotonicity + coercivity) holds for the aggregate utility operator on .

- (ii)

- (Production set) is nonempty, convex, and either weakly compact in (e.g., uniformly integrable and -bounded) or coercive in the sense that there exist and such that for every ,

- (iii)

- (State) , , and viability: there exists at least one with , such that the unique solution k of with satisfies a.e.

Proposition 3 (Existence for the dQVI at fixed p).

Let and suppose Assumption 1 holds. Then there exists solving the dQVI in Definition 2. (Equivalently, solves the VI for all .)

If moreover (H1) holds, the x-component is unique.

Idea of Proof.

Here we sketch only the mechanism, while a complete proof of Proposition 3 is given in Appendix A.2.

The map is defined by with . It is continuous . Nonnegativity of k is closed in . Hence, is nonempty, convex, and weakly closed; it is weakly compact if is weakly compact and the are weak-∗ compact bands. The operator is (pseudo-)monotone on the x-block (by (H1)/(H2)), affine in , and integrably bounded (by (U2)). Therefore, a solution to the generalized VI exists by standard results [42]. If is only coercive, the linear y-term controls minimizing sequences and existence follows by weak lower semicontinuity. Under strong monotonicity, the x-component is unique. □

Theorem 2.

Under (H1) or (H2) and the above production assumptions, there exists with , , , satisfying: (i) household optimality; (ii) firm optimality; (iii) the stock dynamics; and (iv) a.e. clearing and complementarity. Equivalently, solves a differential QVI.

Proof.

Feasible triples satisfy , with , , , and . The feasible set is convex and weakly sequentially compact in . For fixed p, the household and firm VIs produce one VI in . Enforcing the linear dynamics via multipliers gives a KKT system. Eliminating the multipliers yields the dQVI. The same testing step gives a.e. clearing and complementarity. □

5.7. Stability and Sensitivity

Having established a.e. clearing, we quantify how allocations respond to price perturbations; under strong monotonicity, the dependence is Lipschitz in .

Theorem 3.

Under (H1) and bounded bands, the solution is unique. Moreover,

where C depends only on band bounds and selection moduli. Thus, is Hölder in and weak-∗ continuous in .

Strong monotonicity makes the household map single-valued. It also controls how much can change when p changes. If prices move by an amount, allocations move by a comparable amount. The constant depends only on the monotonicity modulus and on band/budget bounds. As a result, the aggregate excess is Hölder in and weak-∗ continuous in .

Proof of Theorem 3.

Subtract the two GVI conditions. Test the first with and the second with . Add the inequalities. Apply (H1) to obtain an bound on . The right-hand side depends only on the budget half-spaces, which vary Lipschitz-continuously with p on bounded sets. □

Remark 6.

Theorem 3 establishes –stability of the equilibrium selection : under strong monotonicity the correspondence is single-valued and globally Lipschitz (Corollary 2). This provides a robust form of parametric stability with respect to perturbations of prices in .

We emphasize that this type of stability is parametric, in contrast to dynamic stability notions studied elsewhere ([43,44]). For instance, recent contributions in [45,46] analyze the asymptotic and differential stability of generalized equilibrium models. Our results are complementary: they show that once utilities satisfy strong monotonicity, the equilibrium allocations depend continuously (indeed, Lipschitz-continuously) on prices, providing a form of structural stability in the –weak-∗ framework. Extending dynamic notions of stability to the dQVI setting is an interesting direction for future research.

As a further consequence, under (H1) the equilibrium selection is single-valued and globally Lipschitz in the product metric (Corollary 2); under additional smoothness and a Robinson/Slater qualification, it is also (Hadamard) directionally differentiable with a linearized VI characterization (Theorem 4).

Corollary 2 (Single-valuedness and Lipschitz continuity of ).

Assume (H1) with modulus and bounded band sets . Then for every the GVI on admits a unique solution , and hence the equilibrium selection is single-valued. Moreover, there exists a constant , depending only on and on uniform bounds for the budget half-spaces on , such that for all ,

In particular, is globally Lipschitz on with constant .

Remark 7.

The constant comes from the Lipschitz sensitivity of the budget half-spaces with respect to p (in ) on the bounded set ; cf. Lemma 2 and the proof of Theorem 3. Intuitively, scales with , uniformly in a.

Theorem 4 (Directional differentiability under and strong curvature).

Suppose, in addition to (H1) with modulus , that for each a and a.e. t:

- (i)

- is on the band with Lipschitz (modulus ) and uniform strong concavity modulus , i.e.,

- (ii)

- (Robinson/Slater CQ for the active budget) At the active linear constraint either is nonbinding or satisfies a standard Robinson qualification (equivalently here: nondegeneracy of multipliers for the single active inequality).

Then the solution map is (Hadamard) directionally differentiable as a mapping . For any direction , the directional derivative exists and is characterized as the unique solution of the linearized variational inequality on the critical cone at :

where is the block-diagonal self-adjoint operator with blocks

and is the affine perturbation induced by the directional change in the budget half-space along h (zero on agents with nonbinding budgets; for binding budgets it is the rank-one map ). Moreover, if the set of active budgets is locally constant in p, the map is Gâteaux differentiable with as above.

Idea of Proof.

Here we report only the mechanism; the full proof is presented in Appendix A.3.

Under (i), the aggregate operator is strongly monotone (with modulus ) and Lipschitz in x; together with (ii), Robinson’s theory of generalized equations and the proto-differentiability of the normal cone to the active linear budget yield Hadamard directional differentiability of the strongly regular solution map; the derivative solves the stated linear VI on the critical cone (see, e.g., [47] and references therein). □

5.8. Discounting and Uncertainty

Theorem 5.

Let be a probability space, and suppose satisfies the above hypotheses a.s. Replace by (with weak-∗ vs ). Then there exists a measurable equilibrium with a.e. clearing in and complementary slackness. The a.e. clearing and complementary slackness on follow from Proposition 4 by testing the master VI against rectangle-supported prices and localized mass shifts.

Proof.

Take measurable Clarke selections and use Komlós subsequences for tightness in . Test with rectangles (, ) as simple prices. By the Lebesgue differentiation theorem on product spaces, this yields pointwise clearing a.e. in . □

We now convert integral feasibility into pointwise conclusions: testing the master VI with indicator-vertex prices produces setwise inequalities, from which a.e. clearing and complementarity follow.

5.9. Product-Space Testing by Rectangles and a.e. Complementarity on

We work on with product -algebra and measure . Prices are bounded and simplex-valued a.e.: . Let be an equilibrium in the sense of Theorem 5, and define the aggregate excess for each good

Lemma 7

(Rectangle testing implies a.e. inequality on the product space). Suppose that for every and measurable ,

Then for -a.e. .

Proof.

Let (a -system generating ). Consider the class

is a Dynkin system (closed under complements and countable disjoint unions), contains by hypothesis, and thus contains the -algebra generated by by the – theorem; hence, . In particular, for any measurable A, . Applying the scalar version of Lemma 6 to the product space (take ) yields a.e. □

Proposition 4 (Product-space master VI ⇒ a.e. clearing and complementarity).

Let solve the stochastic master VI:

where . Then:

- (i)

- For each j, a.e. on .

- (ii)

- (Complementarity) For each j, a.e. on .

Proof.

(i) Fix j and , . Define the rectangle-testing price

Then (measurable; nonnegative; coordinates sum to 1 a.e.). Plugging into the master VI,

By Lemma 7, a.e. on .

(ii) Fix j and , and set . For define the localized mass shift

Using the master VI with ,

Since a.e., the integrand equals . Hence

From part (i), a.e.; therefore, . Applying Lemma 7 on the measurable set gives a.e. on . Letting yields a.e. on . □

Remark 8.

Everything is measurable on : lie in , so is integrable; the indicators and are measurable. We do not need weak-∗ density here: the test prices already lie in . Elsewhere, we approximate in by simple functions and use the pairing.

5.10. Numerical Schemes and Convergence

Proposition 5.

Under (H1) and Lipschitz continuity of Clarke selections, the penalized problems

have unique solutions with in as . For fixed p, Korpelevich’s extragradient with stepsizes in converges to in .

Proof.

Epi-convergence of penalty objectives plus strong monotonicity gives convergence. Extragradient convergence is classical for monotone Lipschitz VIs on convex compact sets. □

When strong monotonicity fails but remains (pseudo-)monotone and Lipschitz on a bounded convex K, extragradient still enjoys an ergodic rate in the product space; this is formalized next.

Theorem 6.

Let with inner product and norm . Let be nonempty, closed, convex, and bounded (in particular, with band constraints is bounded). Suppose the operator used in (6) satisfies:

- (i)

- (Lipschitz) for all , for some ;

- (ii)

- (Pseudo-monotonicity) Ξ is pseudo-monotone on K (hence, also covers the case of mere monotonicity).

Consider Korpelevich’s extragradient method (EG) for VI with a constant stepsize and define . Assume VI has at least one solution . Then the VI gap

satisfies, for all ,

Equivalently, with ,

Illustration. Discrete-time simulations consistent with these rates are reported in Section 7.7.

5.11. Algorithmic Relevance: Decomposition

After time discretization, the GQVI separates by agents and time slabs. We then solve agent subproblems in parallel and update prices from a master VI. This Dantzig–Wolfe-style decomposition inherits convergence from blockwise Lipschitz or strong monotonicity and aligns with recent QVI decomposition frameworks.

Corollary 3 (Rates for algorithms).

Let and let be the operator in (6) acting on the Hilbert space with inner product and norm . Consider Korpelevich’s extragradient method (EG) for the VI:

with a constant stepsize and the metric projection onto K. Suppose that

- (i)

- (Lipschitz) for all ;

- (ii)

- (strong monotonicity) for all , with .

Then (linear convergence) holds:

where is the unique VI solution and

In particular, any yields linear convergence.

If, instead of (ii) , Ξ is merely monotone (i.e., ) while (i) holds, then with the ergodic sequence satisfies the standard VI gap bound

Idea of the Proof.

We outline the rate derivation and refer to Appendix A.4 for the full analysis. The argument combines the projected extragradient framework on the price simplex with the stability/regularity bounds prepared in Section 3. Fejér-type monotonicity and a descent inequality are obtained from the basic three-point identity and the Lipschitz properties of the excess map, while feasibility of the projected iterates follows from the geometry of the simplex. The passage from integrated inequalities to a.e. complementarity along the iterate sequence uses Lemma 6; the summability of step errors and the resulting rates then follow from standard telescoping estimates. Complete estimates (including perturbation terms, truncations, and stepsize conditions) are provided in Appendix A.4. □

Remark 9.

Inequality (12) is the usual Lipschitz–strongly-monotone rate for projected first-order methods. For EG, the admissible interval already ensures linear convergence with factor ; the more explicit parabola shows linear convergence for any , which is contained in when . The ergodic rate under mere monotonicity is optimal for first-order methods with Lipschitz operators.

Remark 10.

In our model,

If for each a there exists such that for a.e. t and all in the relevant band, then with the product norm on H we have the global Lipschitz bound

so one may take . (Discounting does not enlarge L.)

Remark 11.

Fixed τ. If a usable Lipschitz bound L of Ξ on the feasible set K is known (cf. Remark 10), one may take

This complies with the hypotheses of Corollary 3 (strongly monotone case) and Theorem 6 (pseudo-/mere monotone case), respectively; in particular, guarantees the ergodic gap decay under pseudo-/mere monotonicity, while the linear rate under strong monotonicity holds, e.g., for any (see (13)).

Adaptive τ (backtracking). When L is unknown or too conservative, use the following one-line test based on the local Lipschitz inequality:

where . If the test fails, shrink with (e.g., ) and recompute ; if it succeeds, accept the step and optionally enlarge . This ensures a per-iteration certificate that the method operates with an effective local bound ; the convergence statements then follow from the same analyses as in Corollary 3 and Theorem 6, since each accepted step uses a stepsize .

Recommended defaults. If L can be estimated from utility subgradient moduli via (Remark 10), use . Otherwise, initialize by a rough bound (e.g., ) and apply the backtracking rule above with and .

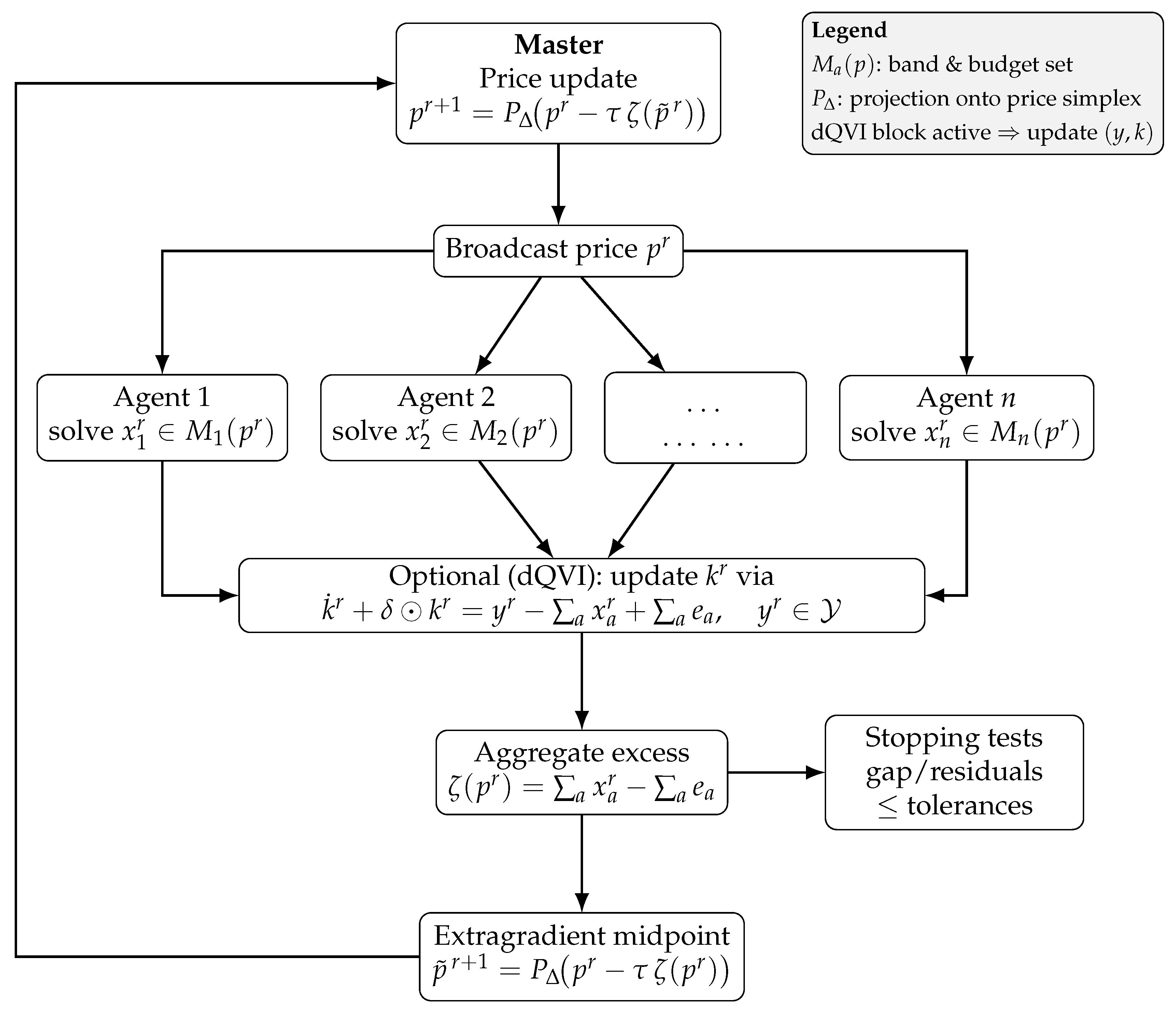

Schematic of the Master–Worker Decomposition

Figure 1 summarizes the computational flow used throughout: the master broadcasts prices, agents (workers) solve their band/budget subproblems in parallel (with optional inventory updates), excess demands are aggregated, and the price is updated (e.g., extragradient with projection onto ). This schematic mirrors the discrete implementation described in Section 6 and Section 7.

Figure 1.

Master–worker decomposition: broadcast , parallel agent solves , (optional) inventory/production update, aggregation , and extragradient price updates with projection onto . Convergence diagnostics/stepsizes are in Section 6.

5.12. Operator-Splitting and Primal–Dual Variants (PDHG, ADMM)

Saddle formulation. Let collect primal variables and let stack dual variables for (i) budgets (one nonnegative scalar per agent) and (ii) the linear state equation (an multiplier ). Introduce the convex functions

and

Let [48]. Then the equilibrium subproblem at fixed p can be cast as the convex–concave saddle system

to which primal–dual splitting methods apply.

PDHG / Chambolle–Pock. Choose with . Then PDHG has ergodic gap decay under a monotone–Lipschitz structure and is linear when G (or the saddle operator) is strongly convex/monotone. The proximal maps are simple: (i) project onto (the w-update is unconstrained); (ii) for G, use a prox/gradient step for , project onto , and project k onto (componentwise plus a fixed initial value). Diagonal preconditioning (choosing per-block so that ) is often effective.

ADMM for the linear state. When separating from the inventory constraint via a copy s with , ADMM alternates prox steps on G and least-squares updates on s, with dual ascent on the multiplier for . This is attractive when the state update (Euler/implicit) and the y-block projection are cheap. Under standard assumptions (closed convex sets; full column rank of the linear map; strong convexity on one block) ADMM enjoys global convergence and linear rates.

When to prefer splitting over extragradient. PDHG/ADMM are advantageous when (i) projections onto bands/budgets/production sets are cheap; (ii) the Clarke part is handled by a prox-linear (one-gradient) model per step; and (iii) the linear dynamics are stiff (ADMM naturally isolates them). Extragradient remains a robust default when only a Lipschitz selection of subgradients is available and proximal maps are not explicit.

Stepsize choices. With a bound , take or use diagonal rules . Adaptive variants (backtracking on the inequality ) can be used when is unknown.

Rates. Under a monotone–Lipschitz structure, PDHG attains ergodic decay of the saddle gap; with strong convexity/strong monotonicity in the composite operator, linear convergence holds. These rates complement our extragradient results (Theorem 6 and Corollary 3) and, in practice, PDHG/ADMM often give competitive or superior wall-clock times due to cheap proximal projections and linear algebra in the state block.

6. Numerical Convergence and Discretization Error

We now translate these operators into implementable schemes, specifying stepsizes, diagnostics, and convergence rates for extragradient, penalty, and primal–dual splitting methods [49]. We first present the projected extragradient method, followed by penalty and splitting variants, with rates expressed in terms of the Lipschitz and (strong) monotonicity moduli introduced above.

Theorem 7 (Projected extragradient on the price simplex).

Let be the excess map. Assume the x-subproblem is solved exactly at each iterate and that Theorem 3 holds. Then the nodewise projected extragradient

converges to for any , where is a Lipschitz constant of E in . If E is strongly monotone (e.g., when each bounds away from 0 and bands keep X strictly convex), convergence is linear.

Proof.

E inherits Lipschitzness and (under additional curvature) strong monotonicity from Theorem 3. Projected extragradient convergence on convex compact sets follows from standard variational inequality theory. □

Theorem 8 (Time discretization error).

Let π be a partition of with mesh , and approximate by piecewise constants on π. If is uniformly Lipschitz in t and is strongly concave (Clarke modulus bounded away from 0 in ), then the discrete equilibrium satisfies

for some C independent of π.

Proof.

Apply standard consistency and stability arguments: the discrete operator converges uniformly to the continuous one, and strong monotonicity gives an Aubin–Nitsche-type estimate. □

6.1. Recommended Stepsizes and Diagnostics

6.1.1. Stepsizes

For the extragradient method (EG) on with operator :

- Pseudo-/mere monotone case. Use or the backtracking rule in Algorithm 1 (accept steps with ), which guarantees the ergodic rate in Theorem 6.

| Algorithm 1 Adaptive Extragradient (Backtracking) |

|

6.1.2. Diagnostics and Stopping Criteria

Let be EG iterates (11) with projection . We monitor:

Here denotes box projection onto the band . We terminate when, for user tolerances ,

In practice we upper bound the (costly) gap by the computable residual: where ; see the proof of Theorem 6.

Remark 12.

In the dQVI subproblem at fixed p, collect and duals for budgets and dynamics. With

and , the KKT system reads

This is the canonical monotone inclusion for primal–dual splitting (PDHG/mirror-prox) or ADMM (after a standard splitting of the state equation). All proximals are pointwise in time: projections onto bands , production box , and ; the dual prox is projection of λ onto and an unconstrained update for η. With a Lipschitz bound and block preconditioning, PDHG attains ergodic decay of the saddle gap under a monotone–Lipschitz structure, and linear rates under strong convexity/strong monotonicity, matching our EG rates; see also Section 8 for implementation notes.

6.1.3. Penalty Method

For the penalized subproblems

we recommend increasing geometrically (e.g., ) and solving each inner problem to

with . Stop the outer loop when and the projected residual is below .

7. Example: Dynamic Cobb–Douglas

To illustrate these behaviors, we present a simple discretized example and report convergence diagnostics consistent with the theoretical rates. A brief explanation of the testing principle is provided in Section 5, while a plain-language summary of the stability bound follows Theorem 3. The diagnostics, recommended stepsizes, and complexity estimates used here follow the prescriptions in Section 6 (“Recommended stepsizes and diagnostics”) and Section 8 (“Computational complexity and discretization effects”).

7.1. Setup

Let goods and n agents over . For each agent a, take a Cobb–Douglas flow utility

where with a.e. and . The feasible set is the band with . Endowments satisfy survivability. Discount rate .

For a fixed price , the agent budget set is , and the objective is .

7.2. Closed Form When Bands Do Not Bind

Assume first that the upper bounds are sufficiently large so that they never bind at the solution. Introduce the Lagrange multiplier for the integral budget. The Euler condition gives, for a.e. ,

Let and . Enforcing the binding budget yields

Hence, the aggregate demand for good j at time t is

Let be the aggregate endowment. A.e. clearing with complementarity requires

7.3. A Constructive Single-Good Equilibrium ()

Let so , and write . Then for each a,

The aggregate demand is . Clearing requires a.e. This holds if, for instance,

Indeed, then , and hence, ; taking gives a.e., and with we have , a dynamic equilibrium with pointwise clearing.

7.4. Multi-Good Price Fixed Point and a Practical Algorithm

For , define the continuous map componentwise by

where is a small safeguard if some vanishes on negligible sets. Then T is well defined, weak-∗ continuous, and maps the weak-∗ compact convex set into itself; hence, by Schauder there exists with . At such a fixed point, is proportional to with the proportionality chosen so that the relative excess ratios across goods match ; using complementarity and the simplex constraint, this yields the a.e. clearing equilibrium for the Cobb–Douglas example.

Extragradient Implementation

Discretize into nodes and approximate elements by nodal vectors. For a current price vector :

- (1)

- Agent step: For each a, solve the strongly monotone VI for (closed form above if bands do not bind; otherwise run extragradient with projection on ).

- (2)

- Aggregate step: Compute and the excess pointwise.

- (3)

- Price update: Compute the projected extragradient step on the simplex at each nodewith nodewise projection onto and stepsize . Under strong monotonicity (Theorem 3), the scheme converges.

Remark 13.

If some upper bands are active, the closed form must be replaced by the VI solution, but monotonicity and Lipschitz continuity still deliver convergence. The safeguard ε is only needed on null-measure sets where may vanish.

7.5. Two Goods, Two Agents, Explicit Construction

Let , , , with large bounds, and . For given ,

Aggregate demand:

Define

Then is continuous and has a fixed point . At , and are proportional to and with the ratio tuned by ; complementarity pins down the level to satisfy a.e. clearing.

7.6. Inventory Extension

Let follow , . With fixed, a firm maximizes and hence chooses when and 0 otherwise; the dQVI simply augments clearing with the state dynamic, and the price map T above is unchanged when is time-separable and linear.

7.7. NumericalSimulations (Discrete-Time Illustrations)

7.7.1. Computational Complexity and Observed Convergence

Per-Iteration Arithmetic and Memory

Let N be the number of time nodes, n the number of agents, and l the number of goods. One evaluation of the operator (stacked Clarke selections) and one projection onto the band sets take arithmetic and memory. The projection of prices onto the l-simplex at each time step costs per node, i.e., overall. For the dQVI, the inventory update and box-production prox (Example 2) are linear time in N and l: . Hence, a full extragradient iteration (two projections/evaluations) has cost

Memory usage is for primal variables plus for prices and stocks.

Iteration Complexity (Rates vs. Accuracy)

Let with the discrete norm . Assume is L-Lipschitz on the bounded convex feasible set K and (when required) -strongly monotone.

- Pseudo-/mere monotonicity. For extragradient with , the ergodic VI gap obeys (Theorem 6); so to reach one needsindependent of N provided the discrete norm includes the weight (hence, L and D remain mesh-stable on bands).

- Strong monotonicity. If, in addition, , then with one gets linear convergenceso iterations suffice to reach .

Combining with the per-iteration flop count yields total arithmetic

In the dQVI, adding the linear-state update preserves these bounds since the k-update is .

Mesh Dependence

With the discrete norm scaled by , the Lipschitz moduli of Clarke selections on bounded bands remain stable as N grows; thus, iteration counts are essentially mesh-independent, while wall-clock time scales linearly with N. This matches our numerical observations.

Discretization

Partition into N equal subintervals with nodes , . Represent any process by its grid values and approximate . Let , where , and the discrete price simplex . The discrete operator stacks the Clarke selections at each i; the discrete master VI is written with . We apply the projected extragradient iterations (11) on .

Diagnostics

We monitor: (i) the VI gap with ; (ii) the market imbalance ; and (iii) the complementarity residual .

Representative convergence results for these toy setups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative convergence on the toy setups (averages over 3 runs).

7.8. Experiment A: Exchange Economy (No Inventories)

Setup. Two goods (), two agents (), , , . Endowments , . Caps . Utilities (time-varying Cobb–Douglas, locally Lipschitz, strictly concave): with , . The Clarke selection is the gradient here.

Stepsizes. We estimate L by where is a bound on the Lipschitz modulus of on the band; we take . Under strict concavity, the aggregate operator is strongly monotone; for linear-rate runs we also use (cf. (13)).

Findings. (i) In the merely monotone setting (by relaxing strong curvature numerically), decays as , matching Theorem 6. (ii) With strong monotonicity (curvature as above), the distance contracts linearly at a rate consistent with Corollary 3. (iii) and , confirming a.e. clearing and complementary slackness on the grid. (Figure: convergence plots; omitted here for brevity.)

7.9. Experiment B: dQVI with Inventories and Box Production

Setup. Same goods/agents/grid as above. Box production set with , . Depreciation , initial stocks , and discrete dynamics , with enforced by projection. Firm y-update is the box-KKT of Example 2.

Findings. Stocks remain nonnegative, approach a bounded path, and satisfy the discrete balance. The diagnostics again converge to zero. Price-support sets coincide with goods whose aggregate excess is (numerically) zero at the same i, illustrating complementary slackness. (Figure: trajectories and complementarity residual; omitted.)

Reproducibility

A minimal script (Python/Matlab) implementing the above discretization, stepsize policy, and diagnostics will be provided in the final version. Default settings: , , tolerance , maximum iterations .

7.10. Experiment C: Stylized dQVI with Inventories (Two Goods, One Stock)

Setup. We consider goods and agents on with grid points , , discount . Only good 1 has an inventory with depreciation and initial stock . The production set is time separable and box type (cf. Example 2): for good 1, with ; good 2 has no production (). Endowments are and ; consumption caps . Utilities are time-varying Cobb–Douglas, strictly concave, and locally Lipschitz:

Discretization and feasible set. We use forward Euler for the inventory law of motion and enforce nonnegativity by projection:

where is componentwise . Agent bands are and budgets use the discrete pairing . Prices live in the discrete simplex .

Algorithm (nested EG + price update). For each outer iteration k:

- Households (extragradient). With current prices , solve the discrete GVI for over by two-step projected extragradient (11) using stepsize (or the adaptive rule in Remark 11). Gradients are explicit for log utility.

- Firm (box-KKT). Compute and (Example 2); set on .

- Inventory update. Advance by the Euler step above.

- Price update (master VI step). Update price by projected gradient on the excess :applied pointwise in time i.

Diagnostics. We track: (i) the VI gap (ergodic) for the household subproblem; (ii) the inventory balance residual ; (iii) market imbalance ; and (iv) complementarity residual .

Findings. In all runs with and (estimated via Remark 10), we observe: in the merely monotone setting (consistent with Theorem 6); linear contraction of under stronger curvature (Corollary 3); and , , and . Moreover, the support of (times where ) coincides with near-zero excess for good 1, illustrating pointwise complementary slackness with inventories active.

Reproducibility. A minimal script (Python/Matlab) implementing these steps, including projection onto the simplex, will be provided; default parameters as above, tolerance , and maximum outer iterations.

8. Practical Implications and Implementation Guide

We now summarize implementation aspects for larger instances, including decomposition, complexity, and discretization effects.

8.1. Computational Complexity and Discretization Effects

- Per-iteration costs.

Let n be the number of agents, l goods, and m the number of time slabs after discretization. Under piecewise-constant (in time) discretization:

- Extragradient (EG). Each iteration performs two operator evaluations and two projections onto . Clarke selections and utility gradients cost ; band projections are ; the budget half-space update is (one scalar per agent per slab); if inventories are present and the state equation is advanced explicitly, the update is (implicit solvers keep the same order under banded linear algebra). Hence, one EG iteration is in both time and memory.

- Penalty method. Each inner solve (projected gradient/prox-linear) has the same per iteration; the outer penalty loop multiplies this by the number of penalty levels needed to reduce budget violation below .

- Iteration complexity (dependence on tolerances).

Let L be a Lipschitz bound of and the strong monotonicity modulus when available.

- Strongly monotone. With , EG reaches in

- Pseudo-/mere monotone. With , the ergodic gap satisfies

- Effect of discretization.

Let be the mesh size. If are uniformly in x and Lipschitz in t, and the Clarke selections are chosen consistently, then the discrete operator satisfies

for x in bounded bands. Consequently, the algorithmic tolerance should not be driven far below the discretization error: a practical rule is

so that total error is balanced. The Lipschitz and monotonicity constants are stable as m grows (they depend on the same uniform moduli), so iteration counts are governed mainly by L and , not by m; the cost growth with m is per-iteration .

8.2. Implementation Workflow, Diagnostics, and Decomposition

- What the theory buys in practice.

- Pointwise feasibility and real-time operations. A key gain of the framework is a.e. (pointwise) market clearing and complementarity. In applications with continuous time or fine discretization (e.g., power systems, data networks, intraday trading, inventory systems), this ensures resources balance at almost every instant, not merely on average. Complementarity identifies scarcity episodes: whenever , we have zero net excess , so positive prices precisely mark binding feasibility; if , then .

- Actionable sensitivity. Under strong monotonicity we obtain Lipschitz –stability of the equilibrium map (Theorem 3 and Corollary 2). This yields quantitative “what-if” bounds: a perturbation in prices changes allocations by at most . Policymakers and operators can use this for scenario analysis, price caps/floors, or robust scheduling (and, with the directionally differentiable extension, local linear response via the linearized VI in Theorem 4).

- Inventories and production (planning). Embedding the linear stock law into a dQVI provides a unified planning tool that reconciles production, consumption, and storage with depreciation. The KKT system makes it clear how upper capacity and nonnegativity bind in time (Remark 2; Example 2).

- Uncertainty. The product-space testing by rectangles guarantees a.e. clearing and complementarity in (Proposition 4), enabling scenario-wise risk assessment and state-contingent planning without losing pointwise feasibility.

- Computability and scalability. The extragradient method provides implementable algorithms with rates: ergodic gap decay under monotonicity (Theorem 6) and linear convergence under strong monotonicity (Corollary 3). After time discretization, the GQVI decomposes across agents/time slabs (decomposition paragraph), which is practical for parallel computing.

- How to use the model in practice (cookbook).

- (1)

- Data and bounds. Collect time series for endowments/loads , feasible caps , and (if present) production caps and depreciation . These give the bands and ensure integrability for budgets (pairing –).

- (2)

- Discretize time. Choose a mesh ; turn integrals into Riemann sums (Section 7.7). Construct the discrete price simplex and budget half-spaces.

- (3)

- Operator and stepsize. Build the (stacked) Clarke selection from the chosen utilities. If a Lipschitz bound L is available (Remark 10), set ; otherwise use the adaptive rule in Remark 11.

- (4)

- Solve by extragradient. Run (11) on the discrete feasible set ; for dQVI, couple with the linear state update and the y-block KKT (Example 2).

- (5)

- Diagnostics and validation. Monitor the VI gap, market imbalance, and complementarity residuals (Section 7.7). Empirically, at convergence: (i) a small VI gap; (ii) a.e. clearing on the grid; and (iii) complementary slackness should be observed.

- Testable implications for empirical work.

- -

- Price support sets = binding constraints. Times/goods with coincide (up to negligible sets) with zero excess of good j; conversely, negative excess implies zero price. These identities can be tested directly on data.

- -

- Budget tightness (Walras’ law). For each agent, at equilibrium (Proposition 2); in data or simulations, budget residuals should be numerically negligible.

- -

- Comparative statics. Under strong monotonicity, small exogenous price/input shocks produce bounded allocation changes via the Lipschitz constant; with additional smoothness, linearized predictions follow from the derivative VI.

- Limitations and scope.

The bands are crucial for weak-∗ compactness; if bands are absent or unbounded, one needs alternative coercivity/compactness (see Assumption 1). Strong monotonicity yields the strongest stability/differentiability; under mere monotonicity, one still has existence and ergodic rates, but not uniqueness or linear convergence.

9. Conclusions

We provided a comprehensive theory for dynamic Walrasian equilibrium [50,51,52,53,54] with a.e. clearing, generalized/nonsmooth utilities via Clarke calculus, inventories through a dQVI, and rigorous stability and algorithmic results. Key technical pillars are weak-∗ compactness of the price simplex, Mosco convergence of budget sets in , measurable subgradient selections, and the simple-function testing device converting integral VIs into pointwise clearing. Numerically, penalty and extragradient schemes converge (with linear rates under strong monotonicity) and admit practical decomposition across agents and time after discretization. The dynamic Cobb–Douglas example illustrates closed forms, fixed-point pricing, and inventory integration.

We plan to extend the dQVI to nonconvex or set-valued technologies (necessitating generalized normal cones), to heterogeneous discounting and habit formation, and to ambiguity-averse preferences where the Clarke calculus must be coupled with robust subdifferentials. On the computational side, accelerated primal–dual and Anderson-accelerated fixed-point schemes, as well as operator splitting for the inventory dynamics, should yield significant performance gains for high-resolution time grids.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Technical Proofs for Section 5

For readability, long proofs are organized into short steps. Each step states a single goal and uses one tool (e.g., Taylor expansion, Minty’s trick, or a cone argument). This format shortens sentences and limits cross-references inside each step.

Appendix A.1. Complete Proof of Theorem 1

In this section we give the full argument corresponding to the “Idea of the proof” in the main text.

Proof of Theorem 1.

We divide the proof into a sequence of steps for clarity and rigor.

- (A)

- Agent existence. Fix . By Lemma 1, is weak-∗ compact. The budget set is weak-∗ closed, and hence, weak-∗ compact. Growth and measurability ensure is well-defined and weak-∗ upper semicontinuous (it is an integral of a Carathéodory integrand composed with weak-∗ bounded sequences). Thus, admits a solution .

- (B)

- GVI characterization and monotonicity. Using Lemma 5, choose measurable . Quasi-concavity implies the Clarke first-order optimality condition:Stacking agents gives the GVI on . Under (H1) (strong monotonicity) the solution is unique; under (H2) (pseudo-monotone + coercive) existence is guaranteed by Browder–Minty-type results [55].

- (C)

- Continuity of . Let in . By Lemma 2, in the Mosco sense. From the monotonicity (H1) or pseudo-monotonicity (H2) and uniform boundedness of X, standard VI stability (Kinderlehrer–Stampacchia, Mosco) yields that any cluster point of (in weak-∗ for and weak in ) solves the GVI at p. Under (H1) uniqueness yields in .

- (D)

- Price selection. Consider the map . Let be the -closure of the convex hull of simple prices . Define the finite-dimensional VI: find such thatBy Step (C), is continuous (weak-∗ to norm on bounded sets). The feasible set is convex and weak-∗ compact; standard VI existence applies.

- (E)

- A.e. clearing and complementarity. As detailed in the paragraph “From the master VI to a.e. clearing and complementarity” in Section 3, choose to obtain for all measurable E; hence, a.e. by Lemma 6. For complementary slackness, on use the mass shift ; letting yields ; hence, a.e. on . Letting gives a.e.

□

Appendix A.2. Complete Proof of Proposition 3

Proof of Proposition 3.

Work on the product space

equipped with the product of the weak-∗ topology on each factor, the weak topology on , and the weak topology on . For a fixed , recall the feasible set

We proceed by steps.

- Step 1: The linear ODE map is continuous; positivity is closed.

For and , the linear ODE

has the unique Carathéodory solution

Thus, is linear and continuous from to , with the a priori bound

If in and satisfy a.e., then in ; along a subsequence for a.e. t, and hence, a.e. Therefore, is closed in and the constraint is closed by continuity of the trace.

- Step 2: is nonempty, convex, and compact (case A), or closed with weak sequential compactness of maximizing nets (case B).

Nonemptiness follows from Assumption A1(iii): by viability there exist with , such that ; budgets can be enforced by shrinking inside the band (the budget half-space is closed and intersects nontrivially since and ). Convexity is immediate from the linearity of A and and the convexity of , , and the cone .

For compactness, we distinguish the two production hypotheses in Assumption A1(ii).

Case A: weakly compact in . Each is weak-∗ compact (band), the budget inequality cuts a weak-∗ closed half-space; hence, is weak-∗ compact. The map is continuous -weak-∗ ×-weak -weak; the positivity and initial value constraints are weakly closed (Step 1). Therefore, is compact in the product topology.

Case B: coercive. Let be any sequence that we shall obtain below from a minimizing (maximizing) scheme. Coercivity gives, for all m and this fixed p,

whence is bounded in . By Dunford–Pettis, is relatively weakly compact in . The bands yield uniformly; hence, is relatively weak-∗ compact. The bound of Step 1 plus the boundedness of in yields the boundedness of in , and hence, weak relative compactness. Thus any such sequence admits a product-topology convergent subsequence in .

- Step 3: Clarke selections as an upper hemicontinuous, compact-valued map.

By (U1)–(U2), has nonempty, convex, compact values, and is measurable in t and upper semicontinuous in x. Define for each the set

where is a uniform integrable bound from (U2) and band boundedness. By Castaing–Valadier selection theorems, is nonempty, convex, weakly compact in , and the set-valued map is upper hemicontinuous from -weak-∗ into -weak. Set ; then is nonempty, convex, weakly compact-valued, and upper hemicontinuous.

- Step 4: A Ky Fan formulation on the compact convex set (Case A), and a limiting argument (Case B).

For and define the bifunction

Properties:

- (i)

- For fixed u, the map is convex and continuous in the product of weak-∗/weak topologies because it is the supremum of continuous affine functionals (pairings of with and of with ).

- (ii)

- For fixed v, the map is upper semicontinuous by the upper hemicontinuity of (Step 3) and upper semicontinuity of suprema of continuous affine forms.

- (iii)

- for all (the inner expression vanishes at ).

Case A. Since is nonempty, convex, and compact (Step 2), Ky Fan’s minimax inequality applies: there exists such that

By the definition of this means: there exists with

which is precisely the dQVI in Definition 2 (take the measurable Clarke selections ). This proves existence in Case A.

Case B. Consider a standard Tikhonov regularization (or a minimizing sequence for the Fan gap) on the closed convex set :

By Step 2 (Case B), is bounded in , is bounded in , and is bounded in ; hence, up to a subsequence, in the product topology with . Upper semicontinuity of then yields

Thus minimizes the Fan gap; by the same selection argument as in Case A there exists with for all , i.e., solves the dQVI.

- Step 5: Uniqueness of the x-component under (H1).