Abstract

The exponential growth of scientific literature demands scalable methods to evaluate large-language-model outputs beyond surface-level fluency. We present a two-phase framework that separates generation from evaluation: a retrieval-augmented generation system first produces candidate abstracts, which are then embedded into semantic co-occurrence graphs and assessed using seven robustness metrics from complex network theory. Two experiments were conducted. The first varied model, embedding and prompt configurations, achieved results showing clear differences in performance; the best family combined gemma-2b-it, a prompt inspired by chain-of-Thought reasoning, and all-mpnet-base-v2, achieving the highest graph-based robustness. The second experiment refined the temperature setting for this family, identifying as optimal, which stabilized results (sd ) and improved robustness relative to retrieval baselines (, ). While human evaluation was limited to a small set of abstracts, the results revealed a partial convergence between graph-based robustness and expert judgments of coherence and importance. Our approach contrasts with methods like GraphRAG and establishes a reproducible, model-agnostic pathway for the scalable quality control of LLM-generated scientific content.

MSC:

68R10

1. Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) increasingly generate scientific text, including structured outputs such as abstracts. However, evaluating the semantic quality of these machine-generated abstracts remains a significant challenge. Standard metrics like ROUGE, BERTScore, or factual consistency checks often focus on local similarity or correctness, but they do not assess whether a generated abstract meaningfully integrates into the broader discourse of a scientific field.

Scientific writing exhibits distinct co-occurrence patterns of terms, which reflect the conceptual organization of knowledge within a domain [1]. For example, specific technical terms tend to appear together in abstracts belonging to the same subfield, and their co-occurrence structures form a semantic network that implicitly encodes the field’s knowledge space. When a new abstract aligns well with the field, its terms should naturally fit into this existing network; conversely, poorly integrated or semantically inconsistent abstracts exhibit anomalous patterns.

We leverage this insight by proposing a network-based evaluation method: we assess how well a generated abstract integrates into a semantic co-occurrence network constructed from a representative corpus of scientific documents. A well-constructed abstract typically exhibits a conceptual network of terms and relationships that is coherent (a well-connected core of ideas), resilient to the loss terms (not reliant on a single “hinge” word), efficient (with key ideas reached in a few steps), and balanced (without fragmentations or thematic “islands”). By embedding the abstract into the semantic network and analyzing global and local graph properties via robustness metrics such as spectral radius and efficiency, we obtain holistic signals of its semantic coherence, topical relevance, and alignment with the field.

Our approach builds upon prior work in which co-occurrence networks were used to distinguish human-written from machine-generated text [1]. We extend this idea to scientific abstracts and, critically, we propose a two-phase pipeline that deliberately separates generation from evaluation. In our framework, the LLM produces an abstract without any graph constraints, after which the text is evaluated by measuring how well it integrates into a semantic network of authentic documents. This design contrasts directly with methods such as GraphRAG [2,3], which inject graph structure during the generation process itself. By decoupling the two phases, our contribution is not to improve generation quality per se but to provide an interpretable and reproducible evaluation layer that captures semantic coherence beyond standard similarity metrics.

This methodology is inspired by ideas from scientometrics and educational technology. In scientometrics, bibliometric networks are used to assess the novelty or impact of research outputs by analyzing their position within citation networks [4]. Similarly, in educational settings, student-generated concept maps viewed as graphs are evaluated via network metrics to gauge understanding [5]. By analogy, we treat the LLM-generated abstract as a node in the semantic network whose structural role reveals its integration and potential contribution to the knowledge space.

Our study contrasts with alternatives that directly extract structured knowledge (e.g., triples or concept graphs) from generated text. While such methods focus on factual consistency, they may overlook the emergent semantic coherence of the text as a whole. In contrast, our network-based evaluation explicitly targets semantic integration: we ask whether the generated abstract fits naturally within the body of retrieved knowledge.

In this paper, we present our two-phase evaluation framework and demonstrate its application to LLM-generated scientific abstracts. We show that network-based metrics provide complementary insights beyond traditional text similarity measures, offering a promising direction for the holistic evaluation of machine-generated scientific content.

Despite these advances, important gaps remain in the literature. Existing similarity-based metrics such as ROUGE, BERTScore, or factuality checks assess local overlap but do not capture global semantic integration [6,7,8]. GraphRAG approaches [3], in turn, embed graph structure into the generation process, yet there is no reproducible framework that leverages graphs as external, post-generation evaluators [9]. Moreover, little evidence exists as to whether graph-theoretic robustness metrics align with human expert judgments of coherence and importance [8,9]. These gaps motivate the following research questions and hypotheses.

To make our objectives explicit, we formulate the following research questions:

- RQ1: Can graph-theoretic robustness metrics capture the semantic coherence of abstracts generated via retrieval-augmented generation (RAG)?

- RQ2:Is there an observable alignment, even if partial, between these graph-based metrics and human expert judgments of coherence and importance?

These questions guide our empirical analysis and provide a concrete basis for testing the contribution of graph-theoretic evaluation in comparison to existing textual metrics.

Based on these research questions, we propose the following hypotheses:

- H1: Abstracts with higher graph-theoretic robustness (e.g., global efficiency, spectral radius, algebraic connectivity) will be perceived by experts as more semantically coherent.

- H2: The configuration that maximizes robustness metrics will also correspond to higher levels of human agreement on coherence and importance.

These hypotheses connect our graph-based evaluation framework to human judgments, establishing testable claims that extend beyond standard similarity metrics.

- Main contributions.

- We propose a two-phase framework that separates generation from evaluation, in which a simple retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) system produces scientific abstracts, and their semantic coherence is assessed independently using graph-theoretic analysis.

- Each abstract is modeled as a semantic co-occurrence network, characterized through seven robustness metrics (e.g., global efficiency, spectral radius, algebraic connectivity), providing interpretable fingerprints of thematic coherence.

- We conduct a comprehensive experimental study across multiple LLMs, embeddings, and prompting strategies, showing that optimal configurations maximize graph robustness while also yielding higher human inter-rater agreement (weighted ).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the background and related work. Section 3 introduces the proposed framework, methodology, and experimental setup. Section 4 presents the results and analysis, highlighting the main findings. Section 5 concludes the study and outlines limitations and directions for future research. Appendix A provides additional information.

2. State of the Art

This section reviews the current landscape in RAG and complex graph-based methods for text analysis and evaluation.

2.1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation

RAG enhances LLMs by integrating external retrieval mechanisms, enabling more accurate and context-aware text generation [10]. A RAG system typically uses a retriever to fetch relevant documents from an external source, followed by a generator (e.g., a seq2seq model) that conditions its output on both the original query and the retrieved content [11]. This approach mitigates issues like hallucinations and fixed knowledge limitations in standalone LLMs [12].

RAG has been successfully applied to tasks such as open-domain question answering [13], knowledge-grounded dialogue [14], fact-based summarization [2], and specialized domains like clinical report generation [11,15]. By incorporating structured data from knowledge graphs (KGs), RAG systems can further improve factual grounding and relevance [16].

In our context, RAG is used to generate scientific abstracts from retrieved literature, and only after generation do we evaluate the text within a network of related documents. This post-generation stance contrasts with GraphRAG [17], for which a corpus-level graph is constructed and then used during retrieval and summarization to steer what is generated. In GraphRAG, the graph is part of the generation mechanism, whereas here, the graph serves as an external evaluator of semantic fit and coherence. The two lines of work are, therefore, complementary: GraphRAG aims to improve generation by structuring context, while our approach focuses on lightweight, model-agnostic quality control after the fact.

2.2. Complex Graph Networks

Complex networks, characterized by properties like a small-world structure [18] and heterogeneous degree distributions, have long been used to represent semantic relationships in language data [19]. In text analysis, nodes may represent words, concepts, or documents, while edges capture semantic relations such as co-occurrence or similarity.

Semantic and document-level networks can be constructed by linking nodes based on shared keywords or embedding-based similarity (e.g., cosine similarity using TF–IDF or SciBERT vectors) [20]. These graphs reveal topical clusters and central concepts, providing insights into the semantic organization of a corpus.

Recent frameworks classify LLM–KG integration into the following: (i) KG-enhanced LLMs (injecting KG knowledge during training/inference), (ii) LLM-augmented KGs (using LLMs to expand or refine KGs), and (iii) synergized models combining both [21].

Our approach diverges by using RAG to generate content first and only then incorporating it into a complex semantic graph for analysis [22].

2.3. Semantic Graphs for Post-Generation Evaluation

Graph-based representations provide a unified lens to assess whether a machine-generated abstract is coherent in itself and well aligned with related literature. We consider two complementary levels reported in prior work. At the document level, abstracts are nodes and edges reflect conceptual overlap, yielding a corpus network where well-integrated texts form dense neighborhoods and outliers remain weakly connected [23,24,25]. At the word level, each abstract induces a co-occurrence network whose topology has long been linked to linguistic structure (small-world, scale-free patterns) and textual quality [26,27,28]. Early evidence showed that graph metrics can distinguish generated from human text [1], and subsequent variants enriched co-occurrence graphs with embedding-based edges and pruning backbones to improve discriminability and interpretability [29,30,31,32].

Methodological refinements across this literature converge on a few robust defaults. For co-occurrence graphs, short sliding windows (2–5 tokens) capture syntagmatic relations, while sentence/document windows capture broader topical links; dependency contexts offer a syntactic alternative [33,34]. To mitigate frequency bias, association measures such as PMI/PPMI (or NPMI) are commonly preferred over raw counts [35,36]. On the corpus side, similarity thresholds or statistical backbones retain salient ties and reduce noise [30]. Together, these choices support graph metrics, e.g., efficiency, connectivity, conductance, spectral radius/gap, as informative summary statistics of semantic organization.

In line with a post-generation stance, we use word-level co-occurrence graphs to obtain a within-abstract structural fingerprint and compare it against the reference profile induced via the N retrieved documents (document level providing the contextual baseline). This synthesis leverages the strengths of both views: document networks indicate alignment/outlierness in the literature, while co-occurrence topology captures internal semantic organization. Our results show that configurations yielding robust word-level topology also align better with expert judgments, supporting graph metrics as model-agnostic proxies for thematic coherence in RAG-generated abstracts.

3. Methodology

This section describes the methodological framework adopted in this study, detailing the data sources, processing pipeline, and evaluation procedures. The objective is to provide a transparent and reproducible account of how RAG was combined with complex network analysis to assess the structural and semantic quality of generated abstracts. We first describe the data collection process and the construction of the experimental corpus. Next, we outline the end-to-end pipeline, including embedding generation, retrieval, and LLM summarization. The subsequent subsections explain how co-occurrence graphs were built, which network metrics were selected, and how they were used to quantify robustness and coherence. Finally, we present the design of the experimental setup and the expert-based evaluation protocol, establishing a systematic foundation for comparing model configurations and interpreting results. All experiments were executed on a dedicated server equipped with 128 GiB of RAM, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 (16 GiB VRAM), and a 1 TB SSD; complete hardware and software specifications are provided in Table A2.

3.1. Data Collection

A scientific document corpus was constructed using metadata exported from the Scopus database [37]. The query used for data retrieval was as follows and is presented in Listing 1.

| Listing 1. The query targets documents containing the phrase “mineral processing” in the title, abstract, or keywords (TITLE-ABS-KEY), restricted to open-access publications (OA, “all”). |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY (mineral processing) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”)) |

The following metadata fields from the exported CSV were used:

- 1.

- Title:document title.

- 2.

- DOI (digital object identifier): unique and persistent document identifier.

- 3.

- Abstract: summary of the document’s content.

To refine the dataset, a filter was applied to include only open access publications. This ensures that all documents are readily accessible, promoting transparency and reproducibility.

3.2. Pipeline

The pipeline (see Figure 1) begins with the ingestion of metadata exported from Scopus. Each abstract and the user’s query are converted into high-dimensional vectors using a pretrained embedding model (see Section 3.2.1); these vectors are indexed in a vector database to enable efficient semantic retrieval. The query embedding retrieves the N most similar abstracts, and both the abstracts and the original query are subsequently inserted into a prompt template. This prompt is then sent to an instruction-tuned LLM, which returns a Proposed Document (synthetic summary) and the list of the N retrieved abstracts.

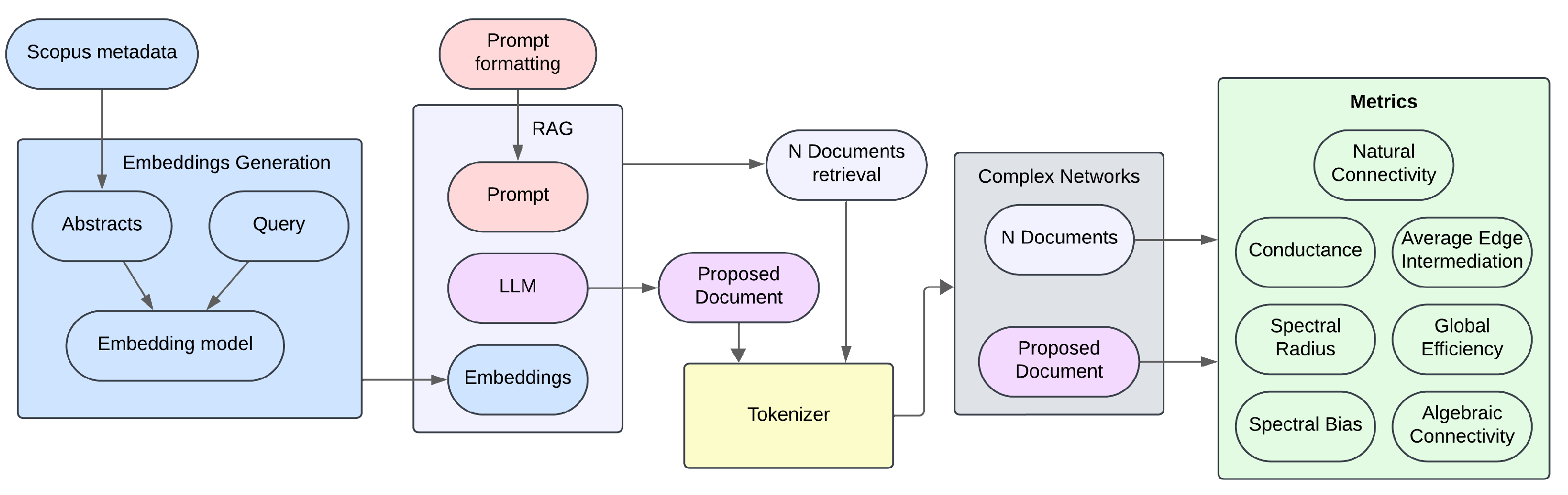

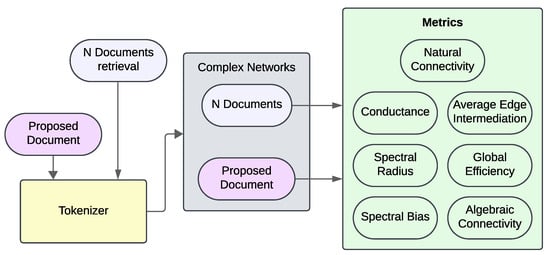

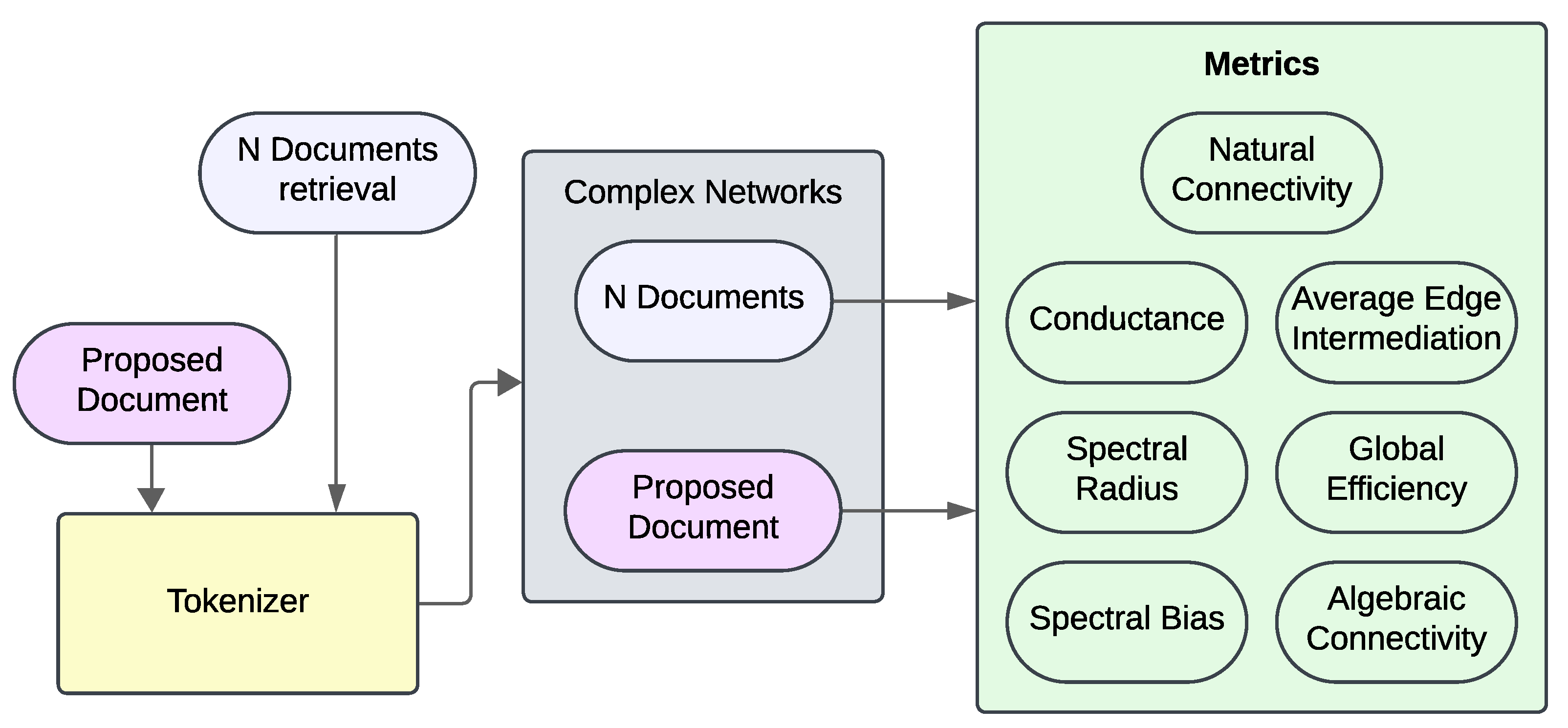

Figure 1.

Full pipeline of the RAG system used in this study. The process begins with metadata extraction from Scopus and embedding generation, followed by the retrieval of the top N most similar abstracts, the synthesis of a proposed abstract using an LLM, and the subsequent construction of co-occurrence networks. Seven structural metrics are computed on each graph to compare the semantics of the generated summary with those of the source abstracts.

Before network modeling, each text (the N abstracts and the proposed summary) is normalized, stripped of punctuation and stopwords, and tokenized while preserving original word order, ensuring consistency in graph construction. A word co-occurrence graph is then generated for each text using a sliding window of size three (see Section 3.3); the resulting set comprises N graphs from the source abstracts plus one for the proposed summary.

Seven metrics are computed on each graph to capture robustness, efficiency, and connectivity: natural connectivity, conductance [38], spectral radius, spectral gap, average edge betweenness, global efficiency, and algebraic connectivity. This intentionally simple RAG design minimizes tunable components and preserves end-to-end traceability, facilitating the reproducibility and interpretability of results.

As part of our two-phase evaluation framework, we employ a simple RAG system (simple/naive RAG) [39] as the text generation component. The choice of a simple RAG system is intentional: the goal of this work is not to optimize the generation process itself but to assess the semantic quality of the resulting abstracts through complex network metrics. While more advanced RAG architectures exist, incorporating multi-stage pipelines, sophisticated reasoning, and enhanced retrieval techniques, this study does not aim to improve RAG performance per se but, rather, to use it as a means for generating abstracts to be evaluated via network-based analysis.

3.2.1. Embedding Generation

The first stage, referred to as embedding generation (Figure A1), involves transforming the textual content of the abstracts into high-dimensional numerical vector representations. Given hardware constraints that prioritized heavier LLMs for later stages, we opted for comparatively smaller and more efficient embedding models.

Two main models from Hugging Face were selected:

- sentence-transformers/all-mpnet-base-v2: A small and efficient model designed primarily for information retrieval and short text clustering (384 tokens) in English. It produces 768-dimensional embeddings. This model was chosen for its strong balance between performance and size, making it suitable for resource-constrained environments [40].

- dunzhang/stella_en_400M_v5: A relatively small model with 400 million parameters, based on Alibaba-NLP/gte-Qwen2-1.5B-instruct and trained using Matryoshka Representation Learning (MRL) [41]. It supports English texts up to 512 tokens and generates 1024-dimensional embeddings. This model offers high-quality representations without the computational burden of larger models [42].

The resulting vector representations are indexed and stored in a vector database to enable fast and efficient retrieval in the subsequent stages of the system [43,44].

3.2.2. RAG

The second stage corresponds to the RAG system (Figure A1). The process begins when a user submits a query (see Listing 2). This query is transformed into an embedding using the same model employed in the previous stage. The resulting query embedding is used to search the vector database and retrieve the top N abstracts most semantically similar to the query.

| Listing 2. Example query submitted to an LLM within the RAG system. This prompt poses a question to the LLM, which generates an answer in the form of an abstract. |

| (“What are tailings, and how do environmental, chemical, and geotechnical factors influence sustainable tailings management in mineral processing operations?”) |

Based on these similarity scores, the top N abstracts most similar to the query are selected and passed to the LLM, which generates a proposed abstract. The resulting set of abstracts (the N retrieved and the generated one) is then passed to the next stage of the pipeline for graph construction and metric computation.

3.2.3. Large Language Models

Three instruction-tuned language models (instruct models) were selected. These models are optimized to understand and execute specific commands or queries, making them well suited for tasks such as answer generation in RAG systems:

- meta-llama/Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct: Part of Meta’s Llama family, this 3-billion-parameter (3B) model is designed to follow instructions. Its relatively small size makes it efficient for deployment in resource-constrained environments without significantly compromising response quality in focused tasks [45].

- Qwen/Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct: Developed by Alibaba Cloud, this 3B model is also instruction-tuned. Qwen is known for its strong performance across a variety of language tasks, often outperforming larger models. Its inclusion enables a direct comparison with Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, given their similar size and purpose, which is useful for evaluating the performance of different LLM architectures within the same parameter class [46,47].

- google/gemma-2b-it: This Google model, with 2 billion parameters, is the most size-comparable instruct version within the Gemma family. Built upon the same research as the Gemini models, Gemma is designed to be lightweight and efficient, making it suitable for local or resource-limited deployments. Despite its smaller size, it performs competitively on reasoning and well-scoped generation tasks [48].

To evaluate each model’s summarization capabilities, three prompts were designed with increasing levels of complexity and specificity (full prompt texts are available in Table A1). Each prompt represents a different prompting strategy to examine how instruction formulation affects output quality [49,50,51].

- Prompt A: This prompt employs the most direct and basic strategy, known as zero-shot prompting. It provides only the retrieved abstracts and a clear instruction to generate a new abstract. The aim is to establish a performance baseline by assessing the model’s inherent ability to synthesize information without additional guidance. It serves as the control condition against which more advanced techniques are compared.

- Prompt B: This version introduces the instruction “take your time before answering.” It is inspired by Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, which aims to improve reasoning by encouraging the model to reflect before generating an answer [52]. The prompt implicitly guides the model to (1) identify key points, (2) organize them logically, and (3) synthesize a coherent summary. Known as Zero-shot-CoT, this approach enhances fidelity and structure without requiring exemplars, simply by reformulating the instruction to promote deliberate processing [53].

- Prompt C: This prompt uses a role-assignment strategy, instructing the model to act as a “postdoctoral researcher.” The goal is to align the model’s output with an expert-level tone, terminology, and analytical perspective [54]. By adopting this role, the model is expected not only to summarize content but to do so with the rigor, structure, and stylistic conventions of academic discourse. This strategy provides deep contextual framing to elicit more sophisticated and domain-appropriate outputs [55].

Finally, the texts of the N retrieved abstracts, along with the original user query, are formatted using one of the three defined prompts. This structured prompt is submitted to the LLM, which returns two outputs: (1) a Proposed Abstract, synthesizing the relevant information, and (2) the set of N retrieved abstracts.

3.3. Complex Network Construction

3.3.1. Text Preprocessing

After retrieving the N abstracts along with the one generated via the LLM, each abstract underwent a preprocessing stage. All text was lowercased, punctuation was removed, and the content was split into words using spaces as delimiters. Each term was thus treated as an independent token while preserving the original word order. Subsequently, low-informative terms were removed using the stopword list provided via nltk [56]. An inherent limitation of this preprocessing approach is that it treats each lexical item as a single node, disregarding potential polysemy or domain-specific sense variations. In highly specialized contexts, the same term may carry distinct meanings (e.g., “flotation” in chemistry versus process engineering), potentially distorting co-occurrence patterns. While this effect is partly mitigated by using domain-restricted corpora, explicit sense disambiguation remains an open challenge addressed in the Limitations section. Several recent studies propose methods to mitigate this issue through word sense induction [57], multi-sense embeddings [58], or sense-linked representations based on nearest-neighbor similarity [59].

3.3.2. Complex Network

Following preprocessing, a complex network was constructed for each abstract using the networkx library [60]. Each network is represented as an undirected weighted graph, , where V is the set of nodes corresponding to the words in the text, is the set of edges generated using a sliding window over the text, and is a weight function indicating the frequency of co-occurrence for each connected word pair. The sliding window size is three, meaning each word connects to the following two. Since there is only one edge between any pair of nodes, and , repeated co-occurrences increment the corresponding edge weight w [61].

It was observed that punctuation introduced artificial breaks in the word sequence, leading to fragmented or disconnected graphs. To prevent this, punctuation was removed prior to network construction. Punctuation was removed prior to network construction to avoid artificial breaks in the word sequence that would lead to fragmented or disconnected graphs. This preprocessing choice was adopted to ensure consistent construction of co-occurrence networks, although no formal statistical validation against randomized baselines was conducted.

After constructing the graphs, corresponding to the N retrieved abstracts and the one generated via the LLM, a set of structural metrics was computed to characterize the semantic organization of each text. These included natural connectivity, global efficiency, conductance, spectral radius, and other topological properties relevant to semantic network analysis.

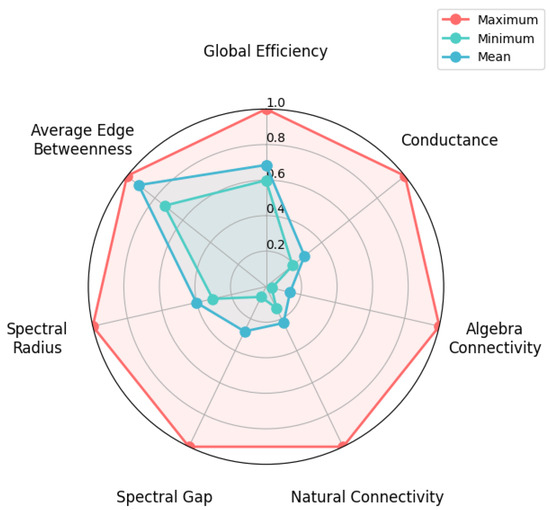

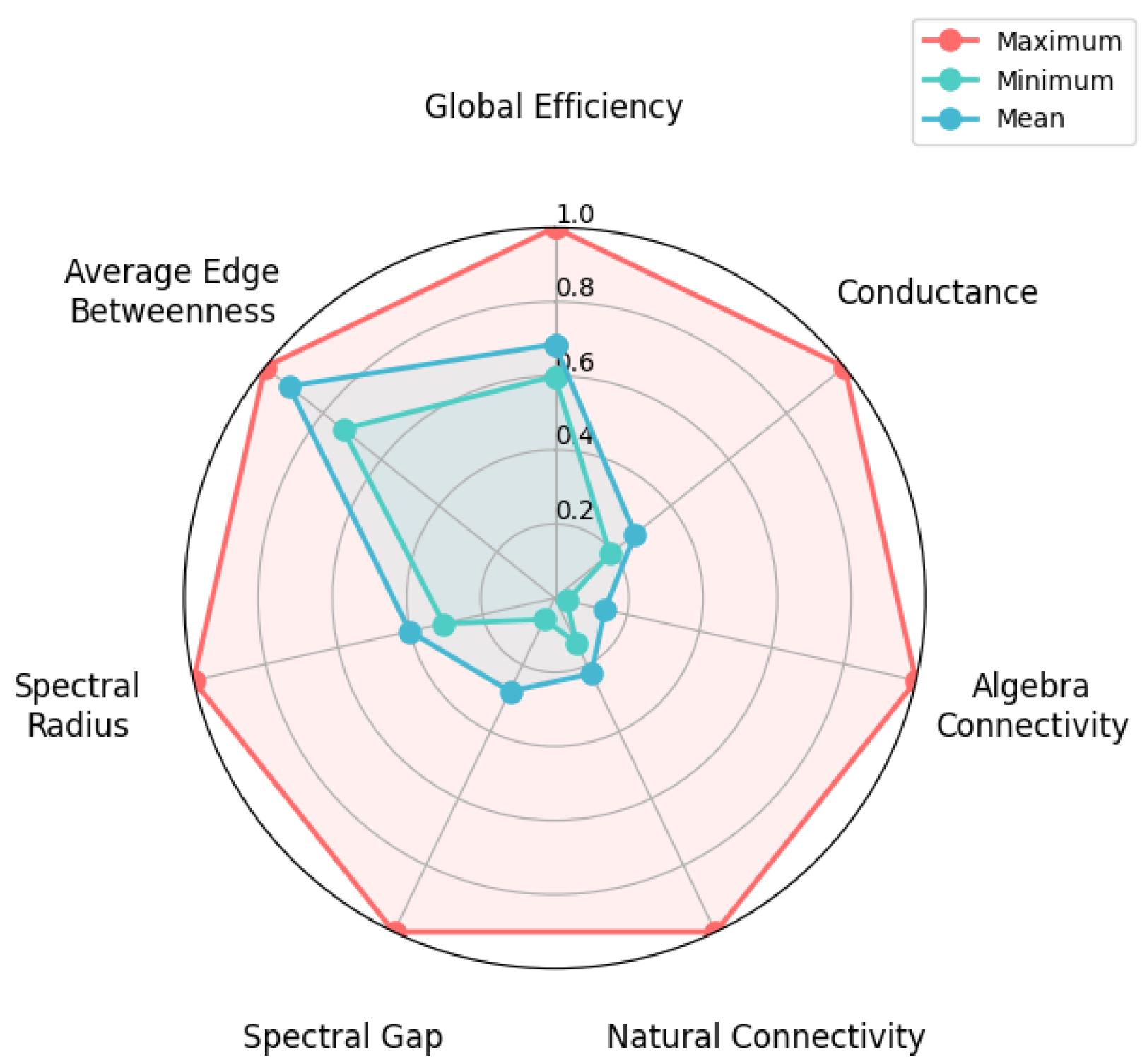

3.4. Structural Evaluation of the Generated Abstract

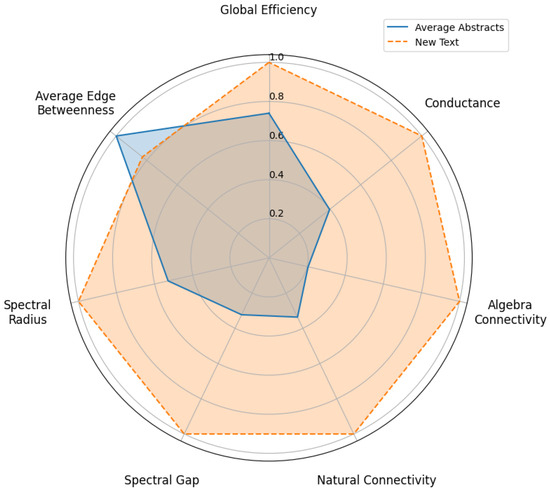

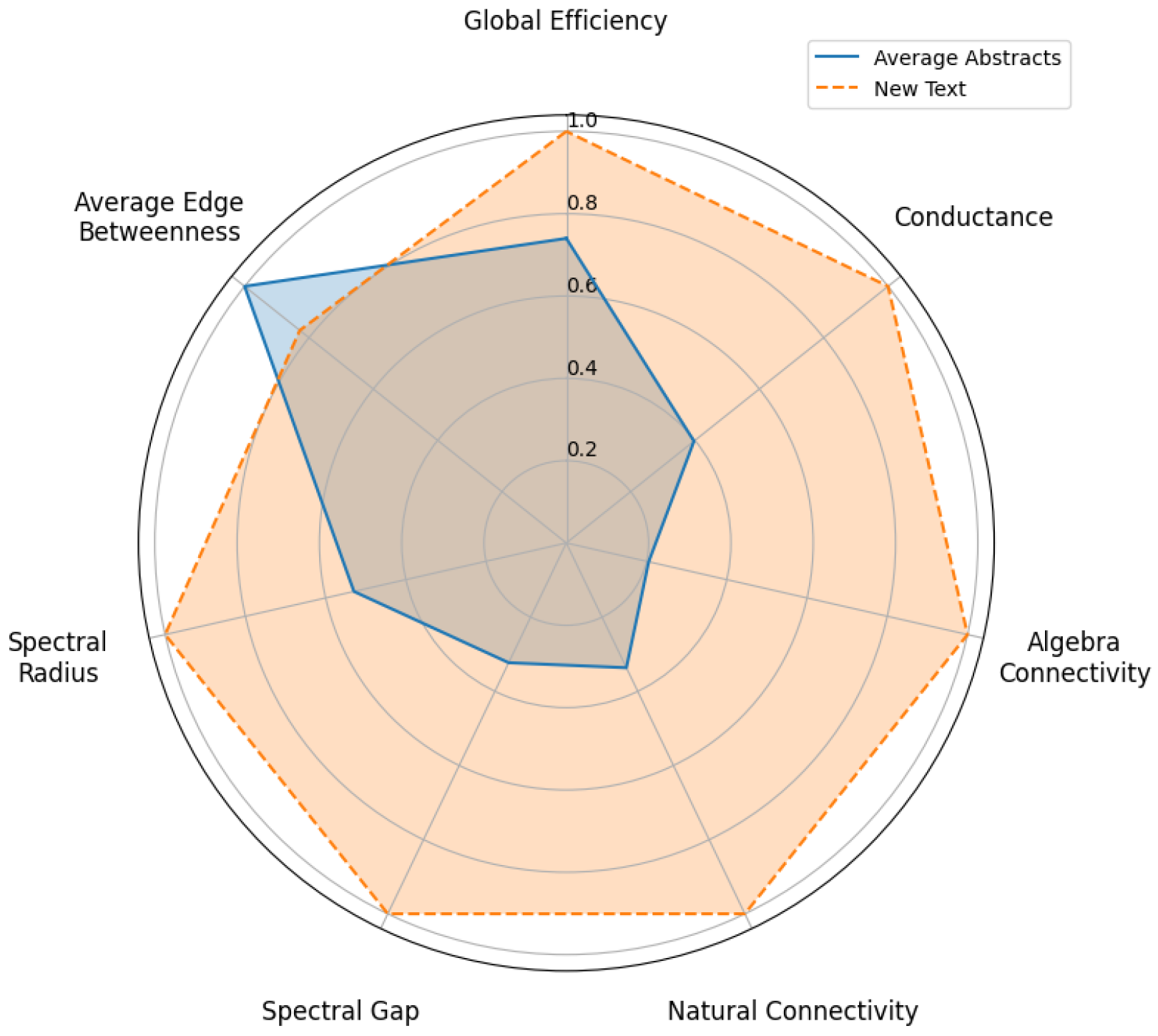

To evaluate the abstract generated via the LLM, the average structural behavior of the original corpus was used as reference. Specifically, the average vector of structural metrics from the N graphs corresponding to the RAG-retrieved abstracts was computed. This average vector represents a typical structural profile against which the new abstract was compared.

Both the average vector and the metrics of the generated abstract were plotted in a radar chart, enabling a clear visualization of structural differences. To establish a quantitative criterion, the area enclosed in each radar plot curve was calculated.

The decision on the relevance of the generated abstract was based on comparing these areas: if the area corresponding to the generated abstract exceeded that of the corpus average, the text was considered structurally improved and thematically valuable. Otherwise, it was discarded for lacking a significant contribution. This procedure ensures an objective evaluation based on the topological properties of individual semantic networks.

3.5. Robustness Metrics for Graphs

All robustness metrics were computed using the networkx (v3.4.2) Python library, relying on NumPy linear algebra routines for spectral and Laplacian calculations. Implementations follow the formulations listed in Table 1, ensuring transparency and reproducibility across experiments.

Table 1.

Summary of structural robustness metrics used in this study, including definitions, references, and implementation details.

We did not compute the modularity indicator Q in this study. Introducing a community-detection step would have required additional modeling decisions (algorithm selection and hyperparameter tuning) not applied elsewhere in our pipeline, thereby reducing comparability and reproducibility across configurations.

In order to quantify the impact of integrating new text into review graphs, we implemented robustness measures that fall into three categories, depending on whether they utilize the graph itself, its adjacency matrix, or its Laplacian matrix. The adjacency matrix A of G is defined as a binary matrix , where if vertex and are adjacent, and otherwise. Consequently, A is a real symmetric matrix with eigenvalues ; the set is known as the spectrum of A, with corresponding eigenvectors . The Laplacian matrix L of G is defined as , where D is the diagonal matrix of vertex degrees. This is, if ; if i is adjacent to j; and otherwise, with being the degree of vertex i. Since both D and A are symmetric with real eigenvalues and an orthogonal eigenbasis, L is positive semi-definite and its eigenvalues are non-negative, with the smallest eigenvalue always being 0. Therefore, the eigenvalues of L can be ordered as , and the set is called the spectrum of L.

In this work, we implement global efficiency and the inverse of average edge betweenness (1/AEB), hereafter referred to simply as edge betweenness for readability, in the first category; spectral gap, natural connectivity and spectral radius in the second; and effective conductance and algebraic connectivity in the third. The use of the inverse of AEB ensures that all metrics follow the same convention: an increase in the value corresponds to higher robustness.

These metrics provide different lenses on the role and impact of the generated abstract in the semantic graph. Local metrics like edge betweenness (on edges to the new node) and effective conductance (of cuts involving the node) tell us about the position of the abstract: whether it is a critical connector, an outlier, or well assimilated. Global metrics like spectral radius, algebraic connectivity, and global efficiency tell us about the overall network structure and how the abstract might be influencing the integrity and connectivity of the knowledge network. For example, a well-integrated abstract might slightly raise global efficiency (by providing useful links) and not drastically lower effective conductance of any cluster, whereas a spurious abstract might stick out as a node that, if removed, hardly changes global metrics but by itself forms a low-effective conductance component. By evaluating these, researchers can quantitatively assess the quality and relevance of a generated abstract: a good abstract in this sense is one that nestles into the graph much like a real abstract would—connecting to relevant neighbors in appropriate ways, without introducing odd network structures.

3.6. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the system, an experiment was designed combining different embedding models, LLMs, and prompting strategies. Model selection prioritized computational efficiency, aiming for feasible execution in a resource-constrained hardware environment.

The models and prompts used in this study are organized as follows: two embedding models, three LLMs, and three prompt types, resulting in multiple combinations for experimentation.

3.7. Evaluation of Thematic Coherence and Importance of RAG-Generated Abstracts

In this study, we evaluate the thematic coherence and relevance of the abstracts generated through the RAG process by conducting a survey with two independent reviewers (R1 and R2). The evaluation focuses on two core dimensions: meaningfulness and importance, each rated on a three-level ordinal scale: high, medium, or low.

Meaningfulness refers to how well each AI-generated abstract accurately captures and represents key concepts within the domain. It reflects both the conceptual depth and contextual relevance of the abstract within the broader area of knowledge.

Importance assesses the perceived significance of each generated abstract, based on its potential impact, influence, or critical role in advancing research within the area of knowledge. It reflects the degree to which the content of the abstract is considered valuable and relevant to the expert community.

To quantify the level of agreement between the two reviewers on these assessments, we employ Cohen’s statistic in its weighted form. Cohen’s kappa is a statistical measure of inter-rater reliability that corrects for chance agreement. Its general formulation is as follows:

where represents the proportion of observed agreement, and denotes the proportion of agreement expected by chance. The resulting value ranges from to 1: a of 1 indicates perfect agreement, a of 0 corresponds to chance-level agreement, and negative values indicate systematic disagreement.

Because the rating scales used in this study are ordinal (e.g., Not Meaningful, Moderately Meaningful, Clearly Meaningful), we apply the linearly weighted version of Cohen’s kappa [68]. In this version, disagreements are penalized proportionally to the distance between categories: a mismatch between adjacent categories (e.g., Not Meaningful vs. Moderately Meaningful) is considered less severe than a mismatch between distant categories (e.g., Not Meaningful vs. Clearly Meaningful). This weighting scheme provides a more nuanced and appropriate evaluation of consensus for ordinal data.

3.8. Experimental Design

Two experiments were defined: the first aimed at finding the best model parameter combination using a fixed LLM temperature of (see Table 2). This baseline value was selected because it represents a standard default in several LLMs, ensuring fair and replicable comparisons across models. Moreover, prior work has shown that performance differences between and are not statistically significant [69], which validates as a neutral starting point. The second experiment then focused on determining the optimal LLM temperature for the best combination identified.

Table 2.

Experimental configuration: each component defines a distinct dimension of model parametrization (see Table A1 for prompts).

- The first component represents the selected LLM architecture included in the study.

- The second component indicates the prompt type used, i.e., the textual input strategy guiding model generation. Variants are described in Table A1.

- The third component refers to the embedding model employed for the vector representation of text, used in retrieval or semantic comparison stages.

- The temperature applied during generation, controlling the model’s randomness. The scale ranges from deterministic (low-temperature) to more stochastic (high-temperature) values.

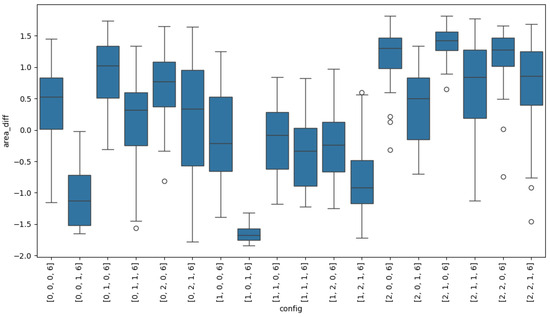

For the first experiment, 31 iterations were conducted to evaluate the behavior of each prompt, LLM, and embedding combination. The main objective was to assess the normality of results for each configuration and identify which showed the greatest favorable area difference for the proposed abstract compared to the average of the retrieved abstracts. In this case, all combinations of LLM, prompt, and embedding model were studied, with temperature , the default for the models used, and a benchmark for later temperature comparisons.

Once the best combination was identified, the second experiment analyzed the same results as in Experiment 1 but for the combinations , where the subscript best indicates the parameters of the best combination found in Experiment 1.

3.9. Metric Quantification

For the presentation of results in tables, a quantification approach based on the difference between the metric of the proposed abstract and the average metric of the retrieved abstracts was used. The formulas employed are as follows:

3.9.1. Difference for a Specific Metric

Let be the metric obtained from the proposed abstract and the metric of the i-th retrieved abstract, where . The difference for a specific metric in iteration j, denoted , is defined as follows:

To compare parameter configurations, a radar chart visualizing multiple metrics is used. Given n metrics for a configuration, with normalized values for and corresponding angles in the radar chart, the area A is computed by adapting the polygon area formula for vertices’ coordinates:

where

- are the normalized metric values;

- are the angles assigned to each metric, uniformly distributed around a circle (0 to radians);

- For the last point (), and to close the polygon.

The metrics considered are those described in Section 3.5. In the specific context of the RAG pipeline, two configurations are compared: the average metrics of the N elements retrieved via RAG, and the metrics of the abstract generated via RAG.

The complete procedure follows these steps: for each configuration, the metric values are computed; metric values are normalized to a common scale (typically between 0 and 1) to allow fair comparison in the radar chart; angles corresponding to each metric are evenly distributed around a circle; Equation (3) is applied to the normalized metric values for both configurations, yielding the area values for retrieved abstracts (area_avg) and the generated abstract (area_new); finally, the area difference, calculated as area_new−area_avg provides a quantitative measure of overall performance difference between the RAG-generated abstract and the average of retrieved elements. A larger area for the generated abstract may indicate better performance across the considered metrics.

This approach allows a holistic evaluation of configurations, where a larger area generally reflects superior performance across diverse metrics. The radar chart visualization complements this analysis by highlighting specific strengths and weaknesses of each configuration relative to individual metrics.

3.9.2. Design of Kruskal–Wallis Tests

For each configuration, the Kruskal–Wallis test compared the distribution of area differences obtained across the 31 independent iterations of the generated abstract against the corresponding distributions of the retrieved abstracts. Thus, each group consisted of 31 samples, one per iteration. In Experiment 1, this procedure was applied separately for each LLM–prompt–embedding combination at fixed temperature . In Experiment 2, the same procedure was used to compare the 31 samples obtained under each value of (0.1 to 1.0) for the best-performing configuration. Explicitly stating the group structure clarifies that the p-values reflect non-parametric comparisons across repeated runs, with per group.

4. Results

4.1. Experiment 1

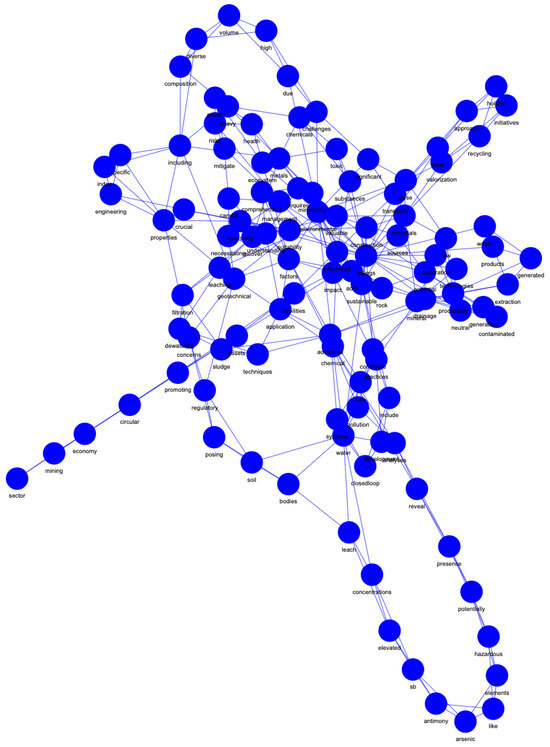

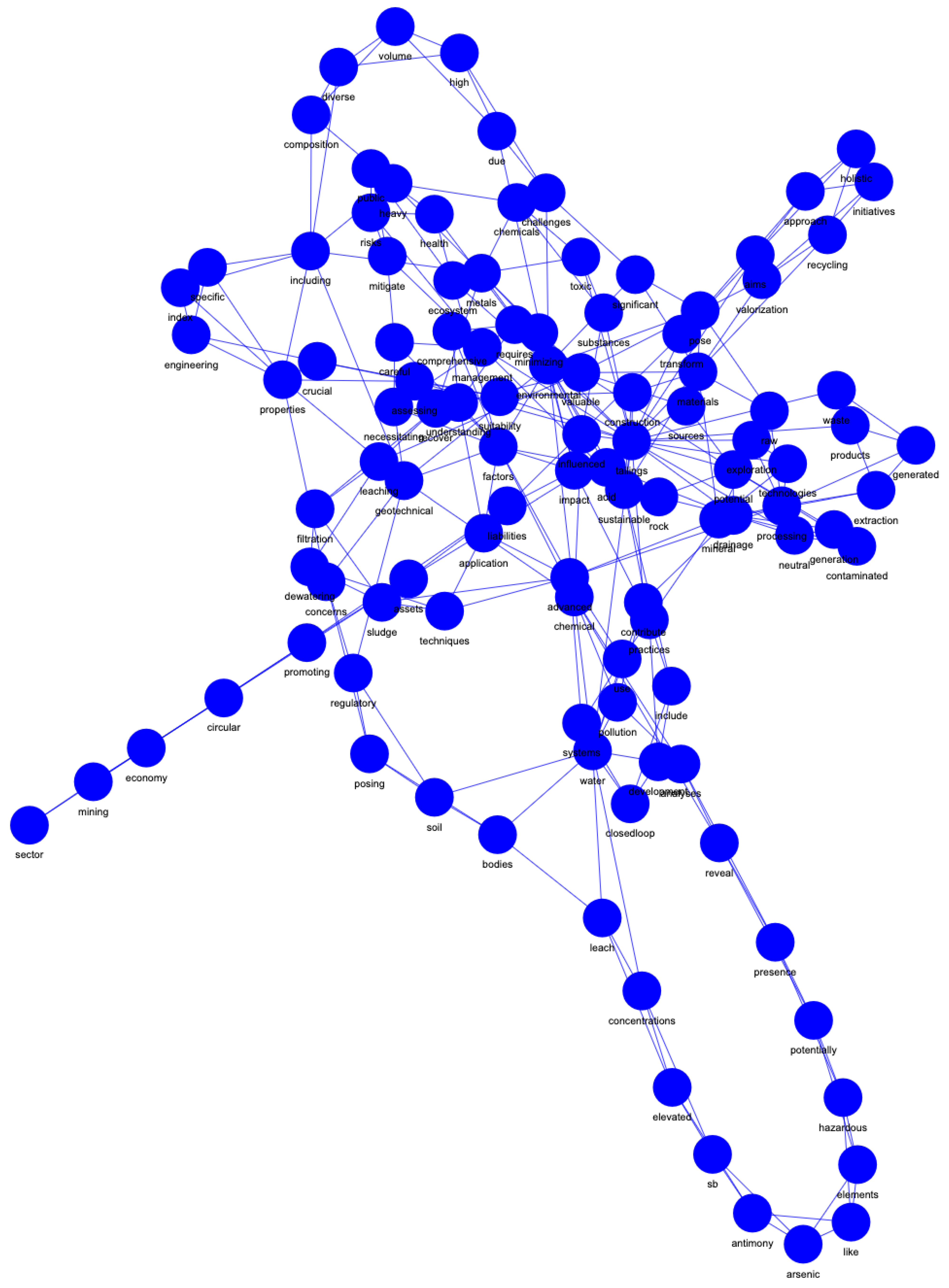

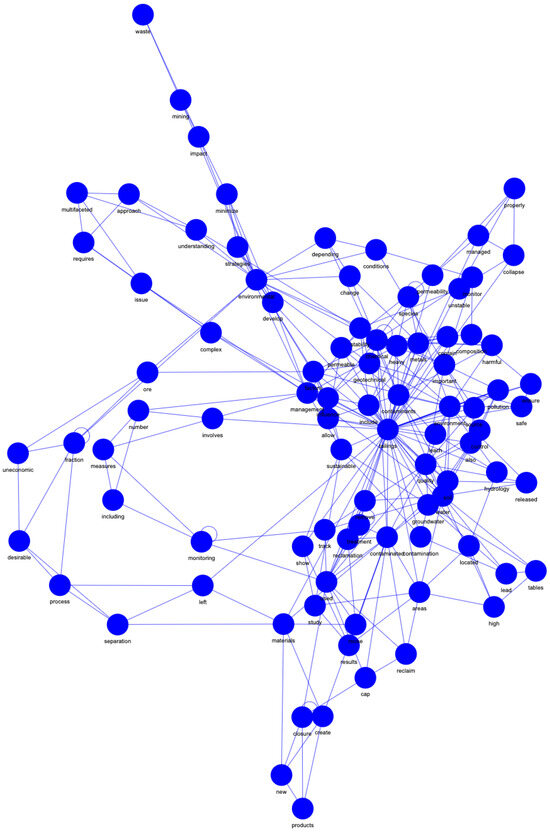

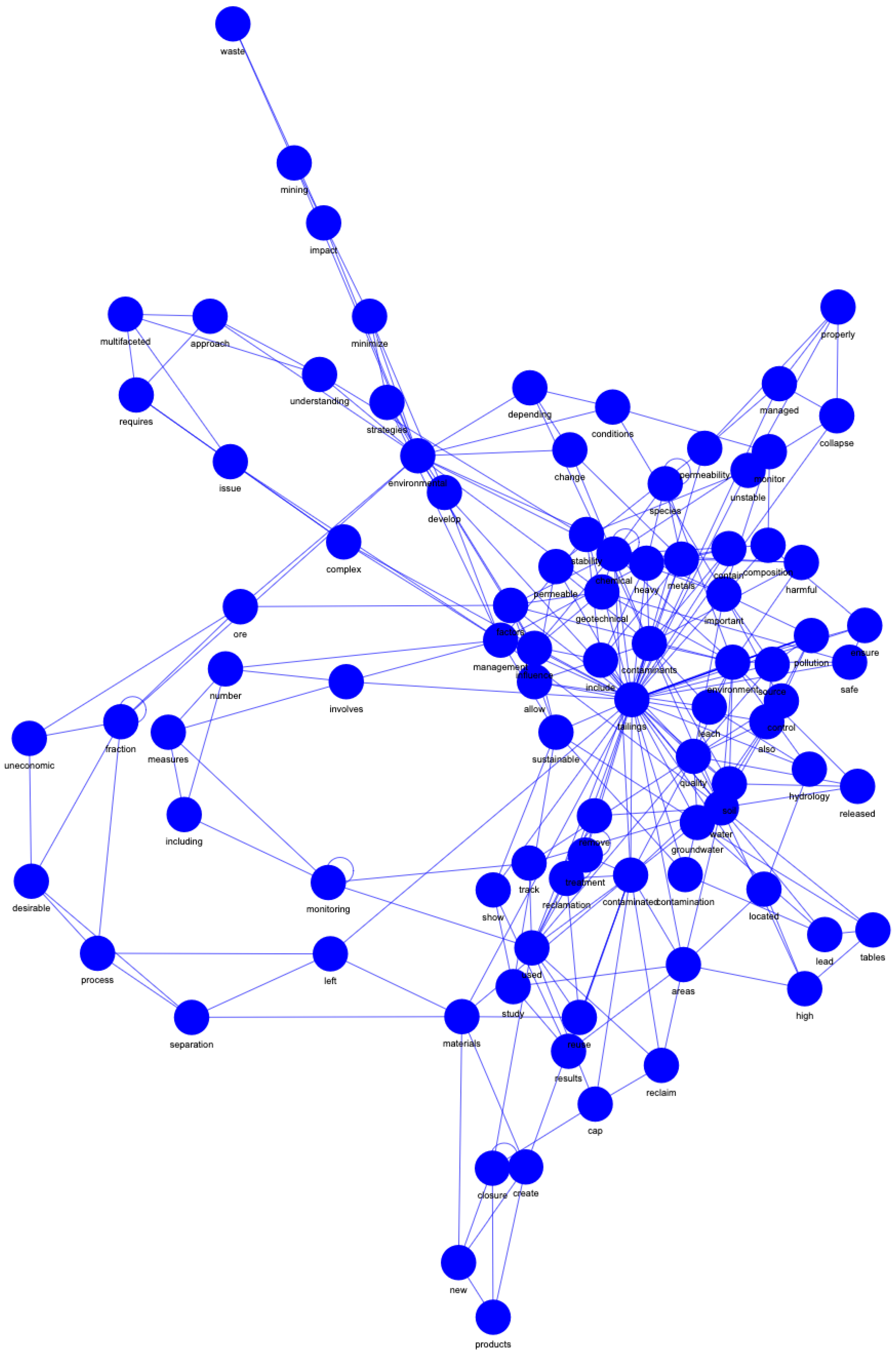

This first experiment aims to identify the optimal configuration of a large language model (LLM), prompt, and embedding model for generating abstracts with superior structural robustness. The evaluation is conducted by comparing a graph representation of the generated abstract against the average of graph representations from a set of retrieved abstracts. Figure A3 shows an example of a graph generated from an abstract proposal generated by the LLM. The analysis unfolds in four stages: first, a consolidated metric based on the area of a radar chart of graph properties is examined to provide a high-level performance overview. Second, individual graph metrics are analyzed to understand the specific structural differences. Third, the normality of the data is tested to determine the appropriate statistical methods. Finally, statistical significance tests are performed to validate that the observed differences between configurations are not due to random chance, ultimately leading to the selection of the most effective combination for subsequent experiments.

4.1.1. Analysis of Graphical Robustness Metrics Experiment 1

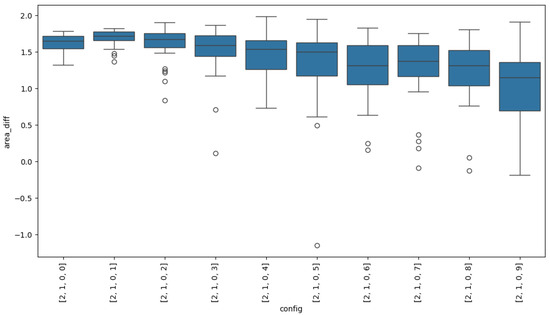

Table 3 shows the consolidated results of the area difference between the graph of the generated abstract and the average of the graphs of the retrieved abstracts.

Table 3.

Area difference between the radar chart of the generated abstract’s metrics and the average radar chart of the retrieved abstracts, grouped by LLM. Positive values indicate that the generated abstract has, on average, a larger radar area than the retrieved abstracts; negative values indicate a smaller area. Reported for each prompt–embedding configuration are the mean, standard deviation (std), minimum (min), maximum (max), and median. Embedding models all-mpnet-base-v2 and stella_en_400M_v5 are abbreviated as mpnet and stella, respectively. Bold values indicate either the highest metric values highlighting best or most consistent performance cases.

Configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2 exhibits the best overall performance, with the highest mean value (1.4004), highest median (1.4205), and crucially, the highest minimum value (0.6530). This indicates that, in all iterations, this configuration consistently produced graphs with metric areas superior to those of the retrieved graphs. Furthermore, its low standard deviation (0.2514) reinforces the stability of this result. Conversely, configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt A and all-mpnet-base-v2 attained the highest individual maximum value (1.8170), albeit with a slightly lower mean and greater variability.

At the opposite end, configuration Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct, Prompt A and stella_en_400M_v5 show the poorest performance, with the lowest mean (−1.6515) and median (−1.6707). Notably, it has the lowest standard deviation (0.1285) among all configurations, indicating that it consistently generates graphs with metric areas below those of the retrieved graphs.

4.1.2. Metrics Experiment 1

Table 4 presents the obtained values expressed as mean ± standard deviation for each evaluated configuration. Based on these experimental results, the configuration consisting of gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, and all-mpnet-base-v2 demonstrated superior performance. This configuration stands out for achieving the highest number of maximum values across the analyzed metrics, justifying its selection for the second experiment.

Table 4.

Comparison of graph metrics for all configurations with temperature . The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the difference between the metrics of the generated abstract and the average metrics of the retrieved abstracts across 31 iterations. Maximum values for each metric are bold. Embedding models all-mpnet-base-v2 and stella_en_400M_v5 are abbreviated as mpnet and stella, respectively. The symbol ↑ indicates that the metric improves as its value increases.

Configuration Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, Prompt A and stella_en_400M_v5, despite having the largest area, does not improve all metrics. In fact, it achieves the highest value in AEB_mean (0.0625), indicating a significant increase in edge betweenness. However, it shows the largest decreases in global efficiency (GE_mean of −0.0606), spectral radius (SR_mean of −0.2657), and natural connectivity (NC_mean of −0.0823). This suggests that the large area results from a less cohesive graph structure, but with more critical information bridges.

In contrast, configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2, which had the smaller area, exhibits the opposite and notably positive behavior in robustness metrics. It obtains the highest mean values in global efficiency (GE_mean of 0.0528), spectral radius (SR_mean of 0.1794), spectral gap (SG_mean of 0.0154), and natural connectivity (NC_mean of 0.04847). Its only negative metric is AEB_mean (−0.0586), the lowest among all configurations. This indicates that this configuration produces highly robust, efficient, and densely connected graphs, where the importance of individual “bridges” is reduced.

Maximizing the radar area does not necessarily translate into improvements across all robustness metrics. Configuration Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, Prompt A and stella_en_400M_v5 attains a large area at the cost of overall efficiency and connectivity, whereas configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2 generates structurally stronger graphs, despite a lower total metric area.

4.1.3. Normality of the Data Experiment 1

Table 5 presents the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test, used to assess the normality of the distributions for the variables area_avg and area_new. The null hypothesis () assumes that the data follow a normal distribution, with a significance level set to .

Table 5.

Shapiro–Wilk test results for data normality.

As shown in the table, the p-values for area_avg () and area_new () are far below 0.05. Given these extremely low values, the null hypothesis is rejected for both variables. This indicates that neither area_avg nor area_new follow a normal distribution. The non-normality of the data supports the use of non-parametric statistical tests, such as the Kruskal–Wallis test, to compare configurations, as these methods do not assume any specific data distribution.

4.1.4. Statistical Significance Experiment 1

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test shown in Table 6 indicate that a significant number of configurations exhibit statistically significant differences in their median area differences. This is evidenced by p-values below , leading to the conclusion that the observed differences in performance across configurations are not due to chance.

Table 6.

Kruskal–Wallis test results for three LLMs: Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct, Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, and gemma-2b-it, evaluated with a fixed temperature, (fourth component ). Each row corresponds to a specific combination of prompt (A, B, or C) and embedding model (all-mpnet-base-v2 or stella_en_400M_v5). The table reports the Kruskal–Wallis H statistic, associated p-value, and whether the result is statistically significant at for the comparison between the generated abstract’s metrics and the metrics of the retrieved abstracts. Additionally, the rank-biserial correlation is calculated as an effect size, and a bootstrapped confidence interval for the difference in medians is provided, offering a robust measure of the magnitude and precision of the observed difference between groups. Bold values indicate the highest H statistic observed within each LLM group, highlighting the configurations with the strongest evidence of group differences.

In particular, configurations Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, Prompt A and stella_en_400M_v5, and gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, and all-mpnet-base-v2 show extremely low p-values (some on the order of ), indicating highly significant differences in their performance. These findings support the claim that the chosen configuration has a real impact on the area difference of the radar metric profiles.

These results validate the presence of significant differences in the mean area differences across most evaluated configurations, confirming that the improvements observed in configurations such as gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2 are not random but represent statistically validated superior performance.

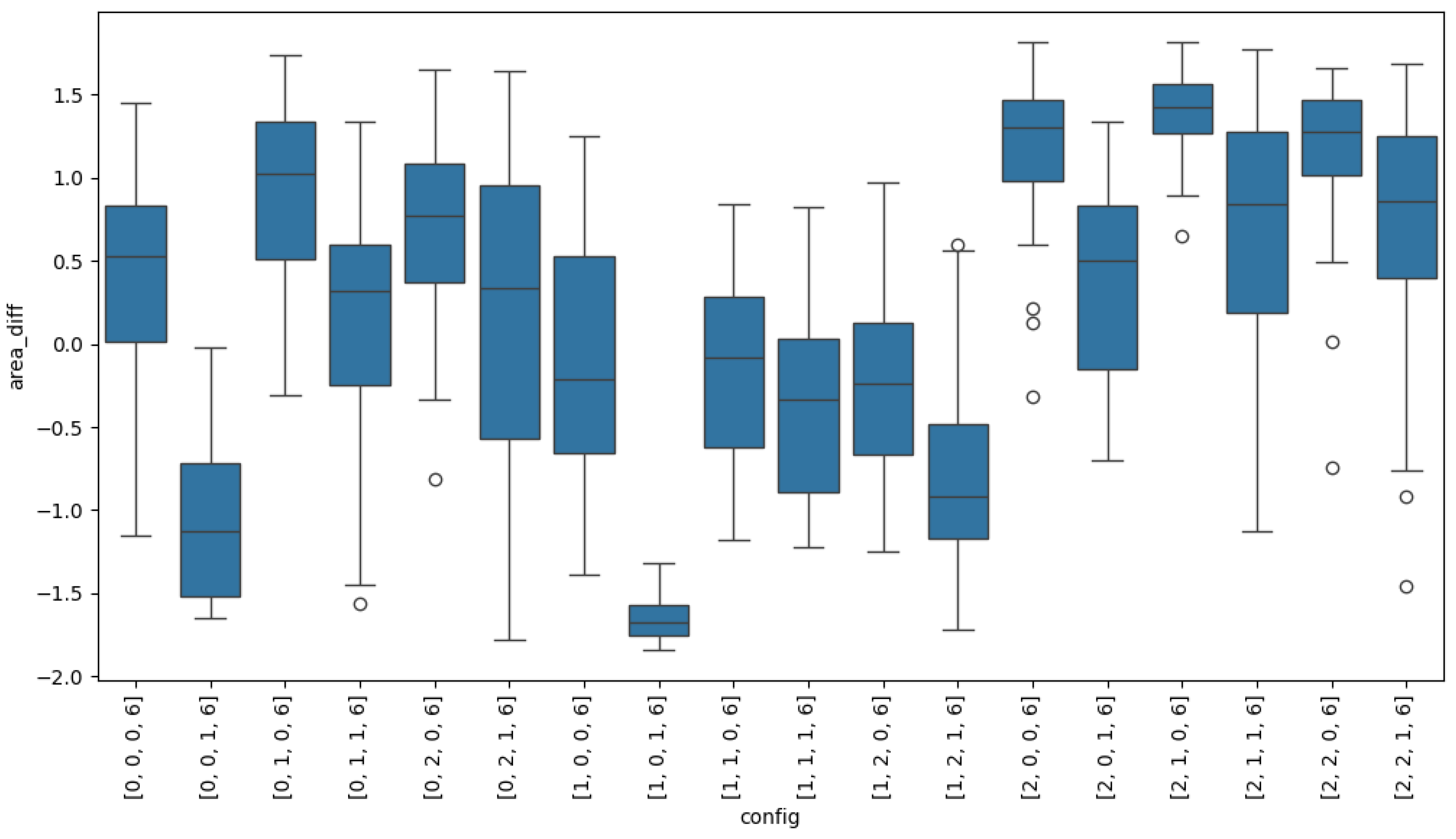

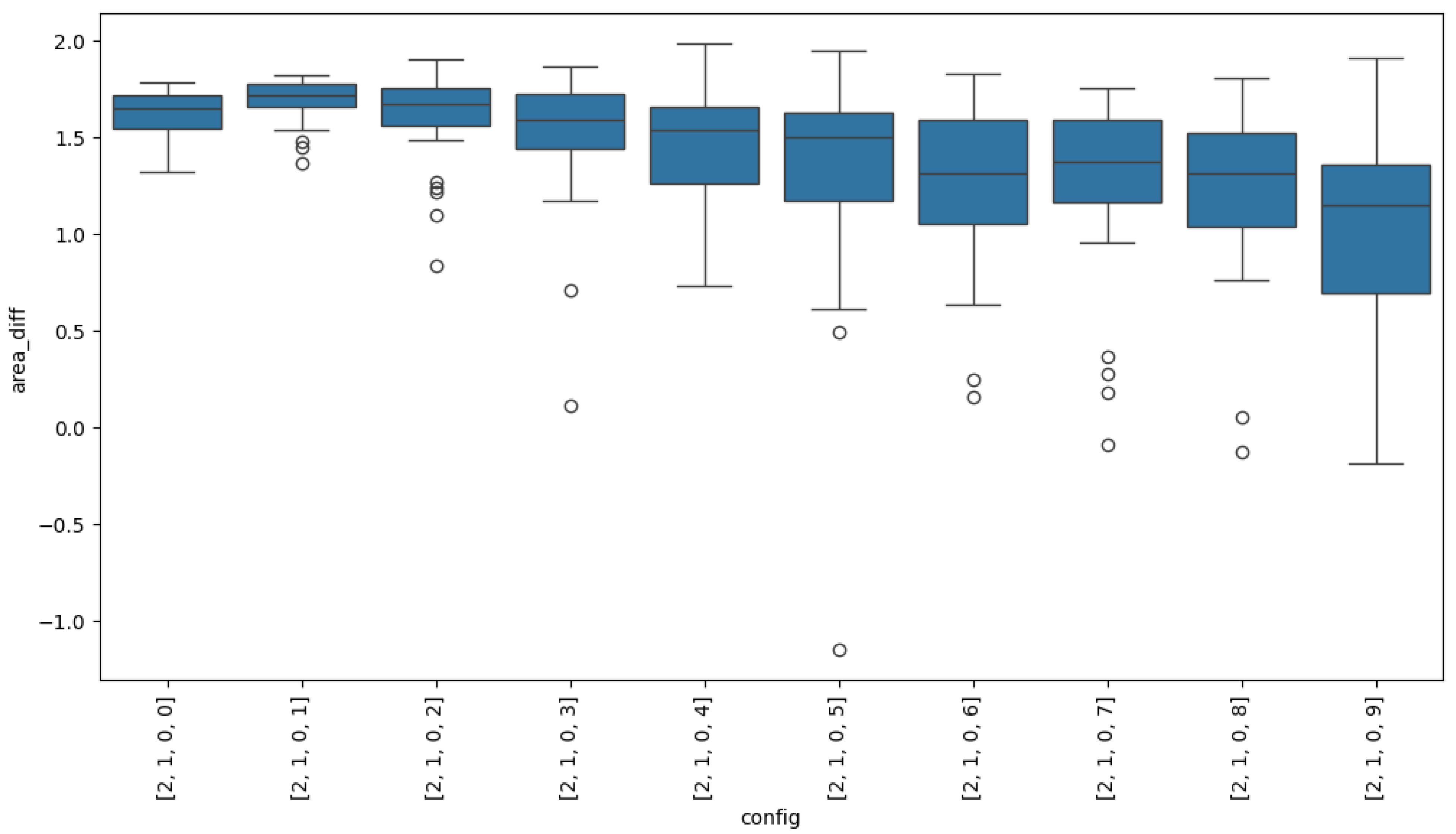

4.2. Experiment 2

Building on the findings from the first experiment, this second experiment focuses on fine-tuning the best-performing configuration: gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, and all-mpnet-base-v2. The primary objective is to determine the optimal temperature () setting by systematically varying its value from 0.1 to 1.0. The impact of this hyperparameter on the quality of generated abstracts is assessed using the same methodology as before. Figure A4 shows one of the graphs created from one of the proposals generated via the optimal combination identified in the previous experiment. This involves analyzing the consolidated radar chart area, examining individual graph robustness metrics, and performing statistical tests to validate the significance of the results. The goal is to identify the temperature that maximizes the structural robustness and consistency of the generated graphs, thereby finalizing the optimal configuration for the system.

4.2.1. Graph Robustness Metrics Analysis Experiment 2

Table 7 presents the consolidated results of the area difference between the graph of the generated abstract and the average graph of the retrieved abstracts, evaluated under different temperature values for configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2.

Table 7.

Results of the area difference between the radar metric graph of the generated abstract and the average of the retrieved abstracts for each configuration. Reported values include the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. Bold values denote the highest performance metrics across temperature settings, highlighting the configuration () that achieved the best overall results in mean, consistency (std), and central tendency (median).

Temperature exhibits the best overall performance, achieving the highest mean (1.6871), the highest median (1.7186), and a relatively high minimum value (1.3676), indicating consistently superior performance. Its standard deviation (0.1177) is also the lowest among the configurations with high mean values, further reinforcing the stability of its results. In contrast, temperature achieved the highest individual max value (1.9828), though with a slightly lower mean and greater variability.

At the opposite end, temperature shows the weakest performance, with the lowest mean (1.0463) and median (1.1453). It also presents a notably low minimum value (−0.1907), suggesting that, in some iterations, it generated graphs with metric areas smaller than those of the retrieved abstracts.

4.2.2. Metrics Experiment 2

Values of global efficiency (), spectral radius (), spectral gap (), and natural connectivity ().

Average edge betweenness () and cut effective conductance involving the newly added node ().

With the optimal combination of LLM, prompt, and embedding identified from the initial experiment, we proceeded to the second experiment. The results of this phase are presented in Table 8, which compares the metrics for configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2 across different values for the temperature.

Table 8.

Comparison of graph metrics for temperatures to for the configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, and all-mpnet-base-v2. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the difference between the metrics of the generated abstract and the average metrics of the retrieved abstracts across 31 iterations. Maximum values for each metric are bold. The symbol ↑ indicates that the metric improves as its value increases.

The analysis of these data reveals that temperature 1 (equivalent to a value of ) yields the most favorable results. Similar to the previous experiment, the configuration that achieves the highest values for global efficiency, spectral radius, spectral gap, natural connectivity, algebraic connectivity, and effective conductance (specifically, temperature ) does not coincide with the one that obtains the maximum value in average edge betweenness. Despite this divergence, temperature stands out for its greater robustness compared to the other evaluated configurations. Therefore, the final configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2 and a temperature of is considered optimal due to its superior overall performance.

4.2.3. Normality of the Data Experiment 2

Table 9 reports the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test used to assess the normality of the distributions for the variables area_avg and area_new. The null hypothesis () assumes that the data are normally distributed.

Table 9.

Shapiro-Wilk test results for assessing data normality.

The p-values for both area_avg and area_new are substantially below the significance level of , indicating strong evidence against the null hypothesis. Therefore, normality is rejected for both variables.

4.2.4. Statistical Significance Experiment 2

Table 10 shows the results of the Kruskal–Wallis test, which was employed to determine whether statistically significant differences exist in the medians of area differences across all temperatures. The result is statistically significant at

Table 10.

Results of the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test evaluating whether the area-difference distributions significantly differ across the 31 iterations for each temperature. Fixed configuration: gemma-2b-it, Prompt B and all-mpnet-base-v2. The table reports the Kruskal–Wallis H statistic, associated p-value, and whether the result is statistically significant at for the comparison between the generated abstract’s metrics and the metrics of the retrieved abstracts. Additionally, the rank-biserial correlation is calculated as an effect size, and a bootstrapped confidence interval for the difference in medians is provided, offering a robust measure of the magnitude and precision of the observed difference between groups. Bold value indicate the highest H statistic observed within each , highlighting the configurations with the strongest evidence of group differences.

The Kruskal–Wallis test results indicate that the temperature parameter significantly affects the performance of the fixed configuration (gemma, Prompt B, mpnet). While the setting with temperature achieved the highest H statistic (26.0081) and the lowest p-value (), the configuration with temperature also showed a statistically significant effect () and, as reported in Table 7, delivered more balanced results in terms of mean (1.6101) and median (1.6683) area differences, with a moderate standard deviation (0.2434). This combination of statistical significance and stable central tendency values led to the selection of temperature for subsequent experiments, prioritizing robustness and consistency over marginal gains in mean performance.

4.3. Expert Evaluation: Meaningfulness & Importance

The analysis of expert ratings was conducted considering both exact agreement and Cohen’s statistic in its linearly weighted form, complemented with additional indicators to better characterize the nature of disagreements.

For Meaningfulness, the proportion of exact agreement between reviewers reached 70%. The unweighted was 0.47, but the linearly weighted version decreased to 0.26, reflecting that most discrepancies occurred between adjacent categories (e.g., Moderately Meaningful vs. Clearly Meaningful), rather than across extreme categories. According to the Landis–Koch scale, this value corresponds to a “fair” level of agreement. Importantly, no systematic bias was detected in the ratings: both reviewers exhibited similar tendencies in their category usage, and the marginal distributions were statistically comparable (, ). This pattern suggests that, although perfect consensus was not achieved, the evaluations of Meaningfulness were relatively consistent and stable across raters.

For Importance, the exact agreement was lower, at 60%. Both unweighted and linearly weighted values converged to 0.05, indicating only “slight” agreement. Again, no systematic bias was observed between reviewers, and their category distributions were nearly identical. However, the marginal symmetry test could not be applied due to zero expected frequencies in some cells, which represents a methodological limitation and restricts stronger statistical conclusions in this dimension. The low highlights that judgments of Importance were notably more heterogeneous, suggesting that experts may apply more subjective or context-dependent criteria when assessing this dimension.

These differences can be better understood through the concept of boundary objects [70]. Boundary objects are artifacts that, while shared across communities, are interpreted differently according to disciplinary perspectives. In our case, experts from construction, electronics, computer science, and fire safety naturally emphasized distinct evaluative criteria, which reduced the probability of high Kappa agreement. This interdisciplinary heterogeneity does not invalidate the consensus but highlights its practical usefulness despite lower statistical alignment.

Taken together, these findings indicate that experts reached a moderate and more stable alignment when judging the Meaningfulness of generated abstracts, while their agreement on Importance was considerably weaker and more variable. This asymmetry between dimensions underscores the relative ease of converging on whether an abstract adequately conveys domain concepts, compared to evaluating its potential impact or relevance, which appears inherently more subjective.

Convergent Validity with Expert Judgments

Since human agreement values were computed globally across the 10 abstracts, a direct item-level correlation with graph metrics is not feasible. Instead, we examined the alignment between graph performance across temperatures and the expert evaluation results. As shown in Table 8, temperature 0.2 consistently achieved the highest values in key robustness metrics (Global Efficiency, Spectral Radius, Spectral Gap, Natural Connectivity, Algebraic Connectivity, and Conductance). This configuration also corresponded to the setting used in expert evaluation, where raters reached fair agreement on Meaningfulness () and slight agreement on Importance ().

Although formal correlation coefficients cannot be computed without item-level data, the convergence between the graph-optimal configuration and the expert-derived consensus provides indirect evidence that structural properties of the semantic graphs capture aspects of thematic coherence perceived by human raters.

4.4. Synthesis of Findings

Integrating the results from retrieval performance, graph analysis, and expert evaluation, we identify three convergent findings. First, the embedding–LLM–prompt combination corresponding to configuration gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, all-mpnet-base-v2 and provided the best retrieval scores while maintaining a lower computational cost. Second, this configuration also maximized key topological robustness metrics, including global efficiency and natural connectivity, indicating that the resulting semantic graphs are structurally resilient and cohesive. Third, under this same configuration, human raters achieved the highest level of consensus observed in the study, with fair agreement on Meaningfulness and slight agreement on Importance.

These convergent findings suggest that both algorithmic performance and human perception of coherence benefit from the same set of modeling choices, strengthening the case for using graph-theoretic measures as proxies for thematic quality in retrieval-augmented generation.

Nonetheless, limitations remain. The analysis was constrained due to the fixed co-occurrence window used to construct the graphs, the relatively small sample size of expert evaluations (10 abstracts), and the domain specificity of the corpus, which may limit generalization. Future work should expand the evaluation to larger datasets, explore dynamic co-occurrence definitions, and validate across other knowledge domains.

4.5. Discussion

The present study highlights both the potential and the limitations of using graph-based metrics as semantic proxies in the evaluation of RAG pipelines. While results indicate that measures such as global efficiency and spectral radius align with expert perceptions of thematic coherence, the approach is not without caveats. Agreement on Importance was low, suggesting that structural graph metrics primarily capture aspects of coherence and connectedness, rather than subjective notions of significance or impact. This finding is consistent with the notion of boundary objects [70], where thematic clusters preserve a shared identity across fields but remain open to multiple interpretations. This helps explain why graph-theoretic robustness aligns with coherence but cannot substitute for evaluative dimensions such as novelty, factual accuracy, or subjective importance.

These results allow us to explicitly revisit our research questions. Regarding RQ1, our experiments showed that graph-theoretic robustness metrics effectively captured the semantic coherence of RAG-generated abstracts: the optimal configuration (gemma-2b-it, Prompt B, all-mpnet-base-v2, ) consistently achieved superior values in global efficiency, spectral radius, and natural connectivity compared to retrieved baselines, confirming H1. With respect to RQ2, the findings revealed only partial alignment between graph-based metrics and human expert judgments. While coherence ratings converged with robustness values (Cohen’s ), perceived importance exhibited weaker consensus (). This partial convergence supports H2 only in part, indicating that robustness metrics are reliable indicators of coherence but less effective for capturing subjective evaluations of significance.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that our framework directly addresses the gaps identified in the introduction: (i) it moves beyond surface-level similarity metrics (e.g., ROUGE, BERTScore) by targeting global semantic integration, (ii) it provides a reproducible, model-agnostic method that leverages graphs as external post-generation evaluators, and (iii) it offers the first systematic evidence, albeit partial, of alignment between robustness metrics and expert judgments. In doing so, the study advances the field by positioning graph-theoretic evaluation as a scalable complement to traditional metrics in RAG pipelines.

Adopting the ontological distinction between ML and AI with LLM-based generation understood as a data-driven, inductive ML process clarifies the ethical implications of ML-generated scientific text, namely accountability, transparency, and sustainability [71]. Within this framing, a model-agnostic, post-generation evaluation layer is valuable because it (i) enables accountability by decoupling quality control from the generator and attributing contributions across retrieval and prompting; (ii) increases transparency via interpretable, graph-based indicators of global semantic integration; and (iii) supports sustainability through compute-light monitoring (no additional LLM passes), aligning with recent calls for energy-efficient ML practice [71]. This positioning underscores that graph-theoretic robustness is best viewed as a governance and QA instrument that complements, rather than replaces, human judgment and task-specific metrics.

In complex networks derived from linguistic or conceptual data, polysemy and synonymy pose significant challenges, as a single node or word may carry different meanings depending on context. Implementing community detection represents a promising strategy to address this issue: by partitioning the network into densely connected modules, such algorithms can isolate distinct semantic contexts, allowing polysemous terms to be interpreted according to their local community membership. Although this mechanism has not yet been incorporated into the present framework, it constitutes a clear direction for future work. Moreover, domain-specific jargon and overlapping terminology can further distort semantic graphs, as multiple senses of a single term may generate misleading links. Community detection, combined with word-sense disambiguation techniques [57,72], could therefore help disentangle these effects, enhancing the accuracy and interpretability of graph-based evaluations.

In terms of transferability, these methods are promising but require careful validation. For instance, in highly specialized domains such as battery materials processing, differences in terminology density, jargon, and corpus heterogeneity could alter both the graph structure and the interpretability of metrics. Extending the approach beyond the current domain will require calibration of thresholds, embeddings, and graph construction parameters.

The results carry implications for the design of automatic evaluation frameworks in RAG. Graph metrics could complement traditional IR measures (recall, precision) by providing a structural signal of thematic coherence. Such integration could reduce reliance on costly human evaluation and enable continuous monitoring of system outputs.

In closing, it is worth clarifying why graph-theoretic metrics were adopted alongside conventional NLP measures. While lexical- or embedding-based scores (e.g., ROUGE, BERTScore, MoverScore) remain useful for capturing local similarity, they do not reveal whether a generated abstract integrates coherently into the broader semantic structure of its domain. Graph metrics add precisely this complementary perspective: by quantifying global efficiency, connectivity, and resilience, they assess structural integration at the corpus level. Thus, our motivation was not to replace established metrics but to extend them with a scalable, model-agnostic layer that targets global semantic coherence.

4.6. Limitations

In the following, we discuss the limitations of our approach. The graphs were built using a fixed co-occurrence window of size three, chosen as a reasonable balance between local and broader contexts. Although an ablation with confirmed that overall trends are stable, certain metrics remain sensitive to window size, meaning that results partly depend on this design choice. Another limitation is that we did not apply formal statistical null models (e.g., permutation-based or randomized graph baselines) to assess whether observed robustness values significantly depart from chance. While we performed non-parametric tests across configurations (Shapiro–Wilk and Kruskal–Wallis), these comparisons do not establish a null distribution for robustness metrics. Incorporating such baselines would strengthen claims about the statistical significance of improvements, and it remains a critical step for future studies.

In addition, comparisons with textual metrics such as BERTScore, MoverScore, and factuality checks suggest that graph metrics add complementary information, yet the integration of these measures was only exploratory. Predictive modeling was also limited: a simple ridge regression on graph metrics indicated explanatory capacity for reviewer agreement, but the small number of abstracts constrains generalizability. Importantly, graph metrics were not computed for the exact set of abstracts rated by human experts, which prevented item-level correlations. This choice was deliberate: with only two reviewers and ten abstracts, such correlations would be statistically fragile. We, therefore, restricted the analysis to configuration-level comparisons while noting that with additional reviewers and a larger set of abstracts, more direct correlations could be carried out in future work. The study carries a risk of post hoc interpretation since the “best” configuration was first selected using graph metrics and only afterward compared to human consensus. The observed convergence should, therefore, be seen as preliminary evidence, not a confirmatory result.

4.7. Future Work

Future directions include the following: (i) scaling up the analysis to larger expert-evaluated datasets to enable item-level correlations between human judgments and graph metrics; (ii) experimenting with alternative embeddings and graph construction strategies (e.g., dynamic co-occurrence windows, dependency-based edges); (iii) extending the evaluation across diverse domains to test robustness and transferability; (iv) developing hybrid evaluation pipelines that combine retrieval accuracy, graph-theoretic metrics, and limited human oversight. Another promising avenue is the integration of predictive modeling (e.g., ridge regression, random forests) to assess the relative importance of graph metrics in explaining expert consensus. (v) Implementing community detection within the complex network component to identify clusters of related concepts and mitigate the influence of polysemous terms; (vi) investigating scaling laws or providing data that allow extrapolation of the observed robustness patterns to substantially larger (e.g., 7B–70B) or smaller models, in order to determine whether such behaviors scale linearly or exhibit different dynamics; (vii) implementing statistical null models, such as permutation-based tests or random graph ensembles, to generate baseline distributions of robustness metrics, thereby enabling formal p-value estimation and strengthening the statistical interpretation of observed improvements; and (viii) incorporating explicit word-sense disambiguation or multi-sense embeddings prior to graph construction [57,58,59], allowing each lexical node to represent a distinct semantic meaning and reducing the impact of polysemy or domain-specific jargon on the resulting network topology.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that semantic graph metrics provide robust and interpretable signals of thematic coherence in RAG-generated scientific abstracts. By deliberately decoupling generation from evaluation, the proposed two-phase framework shifts the focus from improving output fluency to assessing integration into the semantic network of authentic literature. Across multiple LLM–embedding–prompt configurations, we identified an optimal setting (gemma-2b-it with Prompt B, mpnet embeddings, and ) that consistently maximized both retrieval performance and graph robustness metrics. Importantly, this same configuration also yielded the highest expert agreement, offering indirect but convergent evidence that graph-based fingerprints capture aspects of coherence recognized by human evaluators. In relation to our research questions, the study confirms that robustness metrics can effectively capture semantic coherence in RAG-generated abstracts (RQ1) while also showing partial but meaningful convergence with expert evaluation of coherence and importance (RQ2). This directly addresses the gap identified in prior literature, where standard metrics fall short of capturing holistic semantic integration.

Beyond individual metrics, exploratory comparisons with textual baselines (BERTScore, MoverScore, factuality) suggest that graph metrics add complementary information, rather than duplicating lexical similarity. However, the study did not include formal statistical null models (e.g., permutation-based baselines), which we recognize as an important limitation and a necessary step for future replications.

Nevertheless, conclusions should be regarded as preliminary: the human evaluation was limited to ten abstracts and two raters, and correlations could not be established at the item level. Still, the observed alignment at the configuration level provides a reproducible proof-of-concept that semantic graph metrics can act as reliable quality indicators for RAG pipelines. Future work should expand the pool of evaluators and domains, explore hybrid aggregation schemes, and test whether embedding-augmented graphs further strengthen the link between algorithmic scores and human judgment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G., F.A.L. and W.P.; methodology, B.G., W.P., F.A.L., C.M., C.A. and H.A.-C.; validation, F.A.L., W.P. and H.A.-C.; formal analysis, B.G., C.A. and C.M.; investigation, B.G. and W.P.; resources, C.A.; data curation, C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.G., C.M. and C.A.; writing—review and editing, B.G., W.P., F.A.L., C.M., C.A. and H.A.-C.; visualization, B.G., C.M. and C.A.; supervision, F.A.L., W.P., and H.A.-C.; project administration, B.G.; funding acquisition, F.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID, Chile) through the Fondecyt Regular Program, grant number 1231283. The work of Bady Gana was supported by ANID Doctorado Nacional 2024–21240115.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in “Scopus paper metadata” at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14721946.

Acknowledgments

Bady Gana and Freddy Lucay are supported by Beca INF-PUCV.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol | Description |

| A | Adjacency matrix of graph G |

| Area of the radar polygon (for configuration comparison) | |

| Effective conductance of G | |

| D | Degree matrix of G |

| Metric difference at iteration j | |

| Mean of differences across iterations | |

| Shortest-path length between nodes i and j | |

| E | Edge set of G |

| Global efficiency of G | |

| G | Graph (semantic co-occurrence network) |

| H | Kruskal–Wallis test statistic |

| L | Graph Laplacian, |

| N | Number of retrieved abstracts |

| n | Number of nodes (context: graph or embedding dimension) |

| Effective graph resistance | |

| Query and document embedding vectors | |

| Euclidean norms of u and v | |

| V | Vertex set of G |

| Cosine similarity | |

| Dot-product similarity | |

| Average edge betweenness in G | |

| Natural connectivity of G | |

| Cohen’s kappa (inter-rater agreement) | |

| Spectral gap () | |

| Algebraic connectivity (Fiedler value) | |

| Spectral radius | |

| Standard deviation | |

| LLM temperature | |

| Angle for metric i in the radar chart | |

| Acronym | Description |

| BERTScore | BERT-based semantic similarity metric |

| CoT | Chain-of-thought (prompting) |

| CSV | Comma-separated value |

| DOI | Digital object identifier |

| KG | Knowledge graph |

| LLM | Large language model |

| MRL | Matryoshka representation learning |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| NPMI | Normalized pointwise mutual information |

| OA | Open access |

| PMI | Pointwise mutual information |

| PPMI | Positive pointwise mutual information |

| RAG | Retrieval-augmented generation |

| ROUGE | Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation |

| SciBERT | Pretrained language model for scientific text |

| TF–IDF | Term frequency–inverse document frequency |

Appendix A

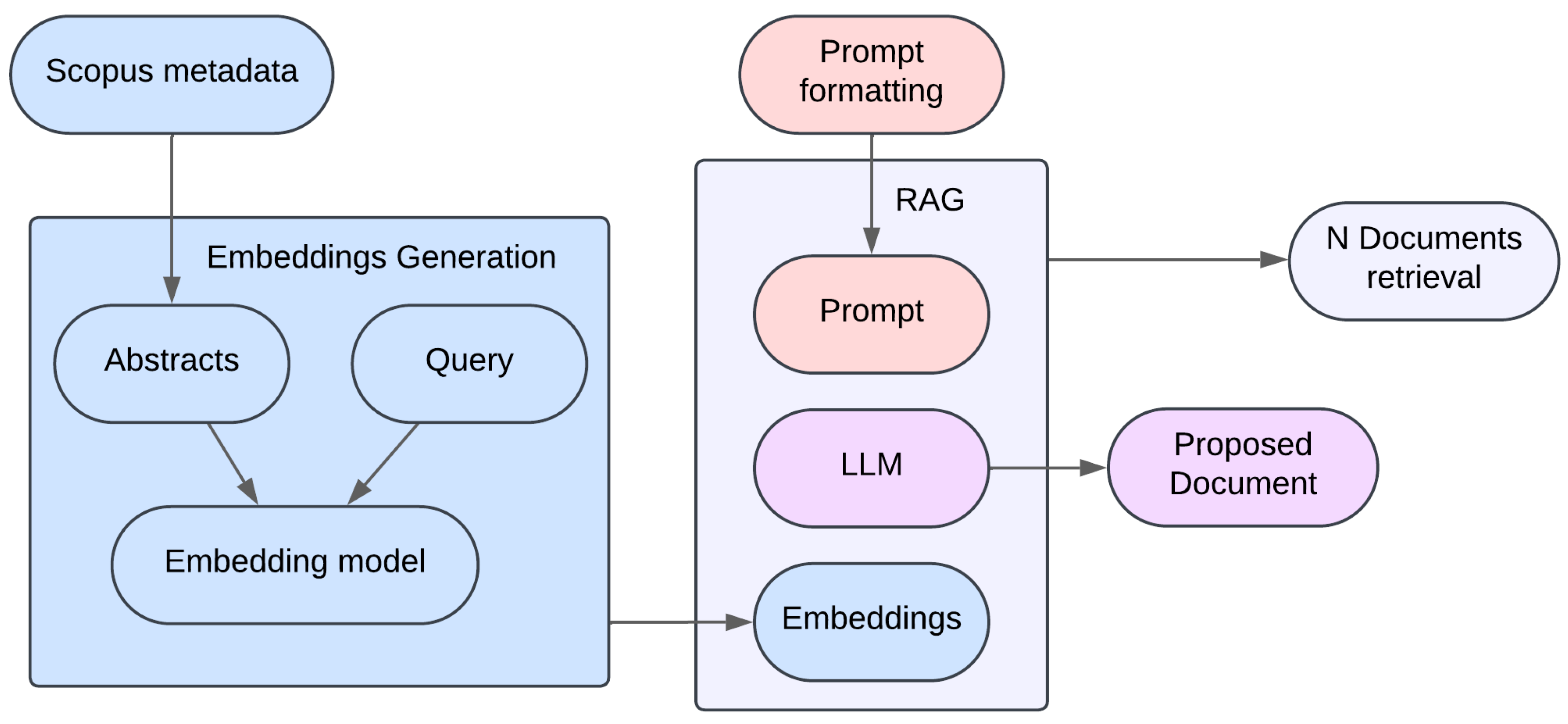

The proposed methodology is based on a RAG architecture for the synthesis of academic documents. The workflow, illustrated in Figure A1, consists of two main stages: the generation of vector representations (embeddings) and the text generation process conditioned on retrieved information.

The retrieval of the N most relevant abstracts is based on the vector similarity between the user query, u, and each abstract, v, in the database. Two similarity metrics were used, depending on the embedding model:

- Dot score, used with all-mpnet-base-v2, which produces normalized embeddings.

- Cosine similarity, used with other models that require prior normalization [73].

Figure A1.

RAG pipeline. The diagram illustrates a workflow that starts with the ingestion of Scopus metadata for embedding generation. These embeddings are used in an RAG system that, given a query, retrieves relevant abstracts, generates a new proposed abstract via an LLM, and outputs both the N relevant abstracts and the proposed summary.

Figure A1.

RAG pipeline. The diagram illustrates a workflow that starts with the ingestion of Scopus metadata for embedding generation. These embeddings are used in an RAG system that, given a query, retrieves relevant abstracts, generates a new proposed abstract via an LLM, and outputs both the N relevant abstracts and the proposed summary.

Figure A2.

Pipeline for the construction and analysis of complex networks. The diagram shows the process flow, starting with the retrieval of abstracts via RAG and the LLM model. These abstracts are then preprocessed and transformed into semantic co-occurrence networks (complex networks), on which various structural metrics are computed to assess the robustness and internal organization of each text.

Figure A2.

Pipeline for the construction and analysis of complex networks. The diagram shows the process flow, starting with the retrieval of abstracts via RAG and the LLM model. These abstracts are then preprocessed and transformed into semantic co-occurrence networks (complex networks), on which various structural metrics are computed to assess the robustness and internal organization of each text.

- Metrics

- 1.

- Global efficiency (): The efficiency between two vertices, i and j, is defined as for all , where is the shortest path length between vertices i and j. The global efficiency of a graph G is denoted as and is calculated as the average of the efficiencies over all pairs of vertices:This measure captures the overall information flow efficiency of the network, as proposed by Latora and Marchiori [62].

- 2.

- Average edge betweenness (): This measure is defined as the number of shortest paths that pass through an edge e out of the total possible shortest paths:where is the number of shortest paths between s and t that pass through e, and is the total number of shortest paths between s and t. The smaller the average edge betweenness, the more robust the graph since the shortest paths are more evenly distributed across each edge, rather than relying on a few central edges [63].

- 3.

- Spectral gap (): This metric evaluates the efficiency with which information can flow through various routes in a graph. It is computed as the difference between the two largest eigenvalues of the graph . A large indicates a robust graph in which information can readily traverse alternative paths, suggesting minimal bottlenecks or weak links [64].

- 4.

- Natural connectivity (): Natural connectivity can be interpreted as the “average eigenvalue” of the adjacency matrix , and it is defined as follows:It effectively measures the redundancy of pathways through the weighted count of closed walks. This metric is closely linked to the graph’s overall topology and its dynamics [65]. In simpler terms, a higher natural connectivity indicates the presence of more alternative paths, enhancing the graph’s robustness against disruptions.

- 5.