Optimal Decision-Making for Annuity Insurance Under the Perspective of Disability Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Construction and Solution of a Multi-Period Life-Cycle Model Based on Disability Risk

2.1. Theoretical Preparation: Dynamic Programming Algorithm

- (1)

- Deterministic transition: or

- (2)

- Stochastically ,

- (1)

- Optimal substructure: any sub-policy of an overall optimal policy must itself be optimal for its corresponding starting state.

- (2)

- Markov property: the evolution of future states depends only on the current state and decision , and is independent of the historical path.

2.2. Model Design

- (1)

- Consumption lower bound (the minimum subsistence level);

- (2)

- Consumption upper boundwhere is the minimum subsistence level at time , is the labor income at time , represents the assets at time , and is the disability cost at time . If the individual becomes disabled before retirement, then until the person recovers or retires, reflecting the loss of labor income due to disability;

- (3)

- Asset accumulation equation

2.3. Model Solution

- (1)

- Parameter Setting and Initialization

- (2)

- Backward induction (from to )

- (3)

- Handle the death state.

- (4)

- Forward simulation.

2.4. The Core of the Multi-Period Life-Cycle Model Based on Disability Risk

2.4.1. Optimal Annuity Purchase Decision

2.4.2. The Endogenous Characterization Mechanism of Disability Risk

- (1)

- Financial constraint effect: The disabled state triggers disability-related health costs (which directly deplete current assets ) and potential income loss (caused by disability before retirement), both of which jointly reduce the disposable resources available for consumption and annuity premium payments.

- (2)

- State transition randomness: The health state evolves stochastically according to an age-dependent transition probability matrix

3. Empirical Analysis of Optimal Annuity Insurance Decisions for the Middle-Aged Population

3.1. Definition of Core Concepts

- (1)

- Middle-aged and elderly population. Based on the World Health Organization’s age classification standards and China’s gradually delayed retirement policy (to be implemented from 2025), individuals aged above 45 are defined as entering middle age, with above 65 as the starting point for old age and retirement.

- (2)

- Annuity insurance. This specifically refers to individual annuity insurance products within the personal pension security system.

- (3)

- Health status. According to the Activity of Daily Living Scale (ADL), individual health status is divided into four discrete levels: healthy (no impairment in either the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (PSMS) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), mildly disabled (1–2 impairments in only one of the two abilities), severely disabled (surviving but not falling into the above two categories), and deceased.

3.2. Data Resource

3.2.1. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS)

3.2.2. China Household Finance Survey (CHFS)

3.2.3. Data Integration and Application

- (1)

- Health state transition probabilities: based on CHARLS panel data from 2018 to 2020, two-year health state transition probabilities were calculated by age group and then converted into five-year probability matrices, which serve as the core parameters of the life-cycle model.

- (2)

- Income–asset relationship modeling: using CHFS 2019 data, a log–linear regression model of income and assets for individuals aged 46 years is constructed to estimate the income trajectories of individuals with different initial asset levels.

3.3. Income–Asset Model

3.3.1. Design of the Log–Log Linear Income–Asset Regression Model

3.3.2. Estimated Coefficients for the Log–Log Linear Regression Model of Income and Assets

3.4. Parameter Setting

3.4.1. Probability of Health State Transition

- (1)

- The probability of remaining healthy decreases with age. In the 46–55 age group, the probability of healthy males remaining healthy is 86.13%, and for females, it is 75.47%. By ages 76–85, these probabilities decline significantly to 39.33% for males and 35.83% for females, indicating a marked reduction in the ability to maintain health with advancing age.

- (2)

- Disability states show a “downward trend”. The probability of transitioning from “mildly disabled” to “severely disabled” is notable across all age groups (e.g., 12.48% for males and 20.29% for females aged 56–65). In contrast, reverse transitions (from severely disabled to mildly disabled or healthy) are highly unlikely, reflecting the irreversible nature of disability progression.

- (3)

- The mortality risk increases significantly with age and disability severity. The five-year mortality probability for healthy individuals is less than 2% in the 46–55 age group, while for the severely disabled, it is 6.17% for males and 4.77% for females during the same period. By ages 76–85, the mortality probability for severely disabled males rises sharply to 46.87%, and for females, to 29.97%, indicating a strong correlation between disability severity and mortality risk.

- (4)

- Gender differences are evident in disability transitions. Females generally show a survival advantage when healthy or mildly disabled. Moreover, under severe disability, their mortality risk is typically lower than that of males in the same age group. For example, among severely disabled individuals aged 76–85, the mortality probability for females (29.97%) is significantly lower than for males (46.87%).

3.4.2. Utility Function

3.4.3. Other Parameters

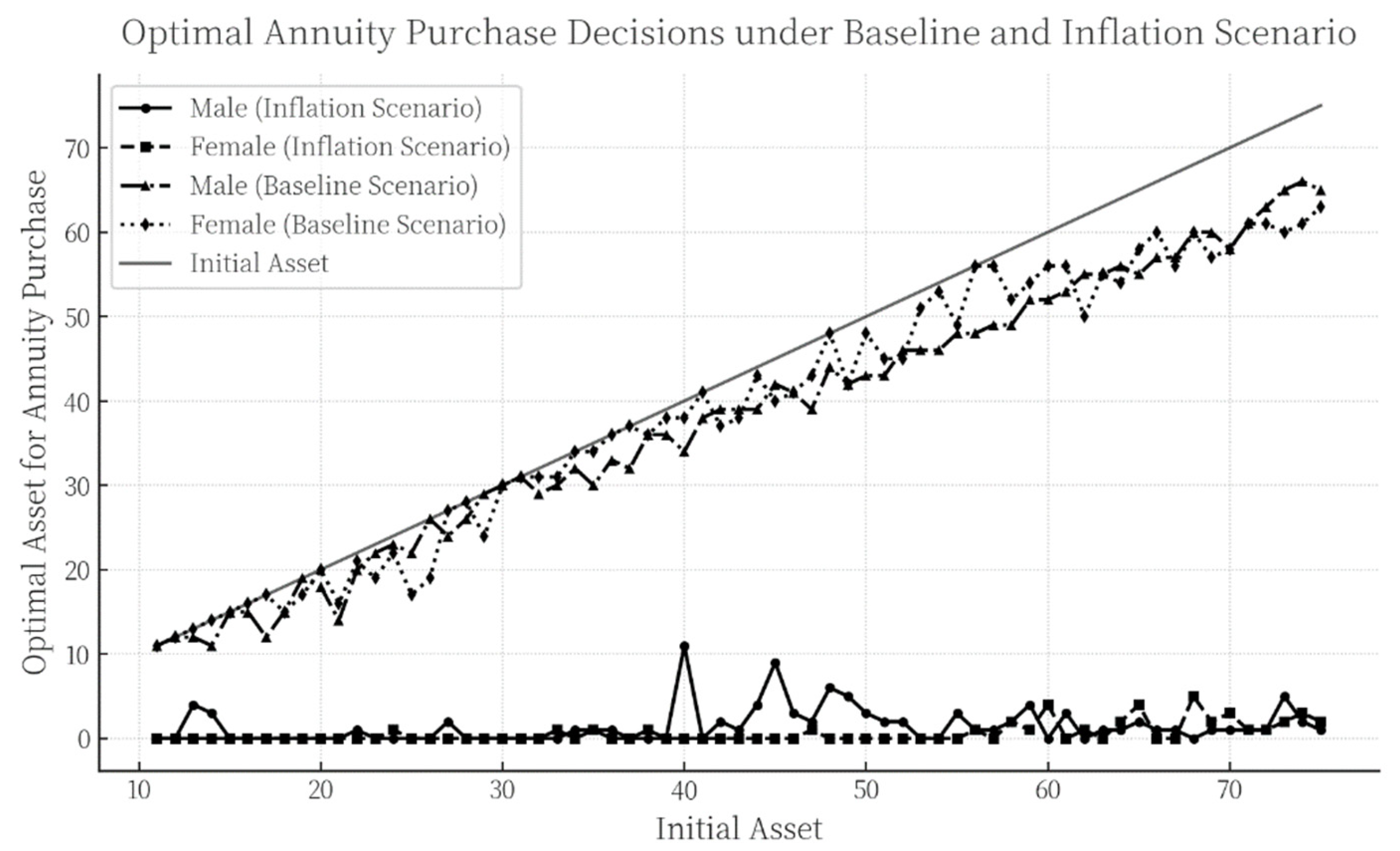

4. Empirical Results of Optimal Annuity Purchase Decisions for the Middle-Aged Group

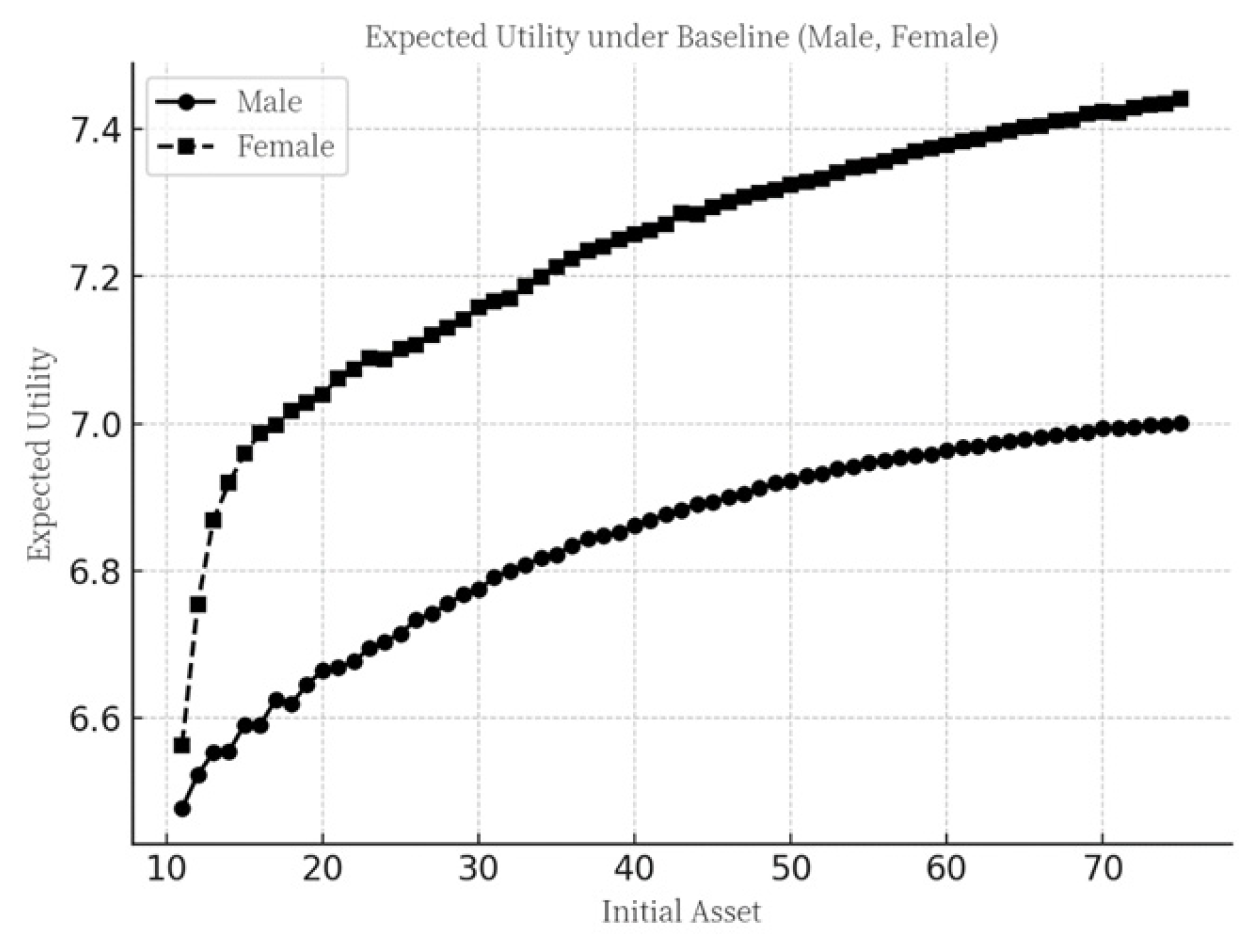

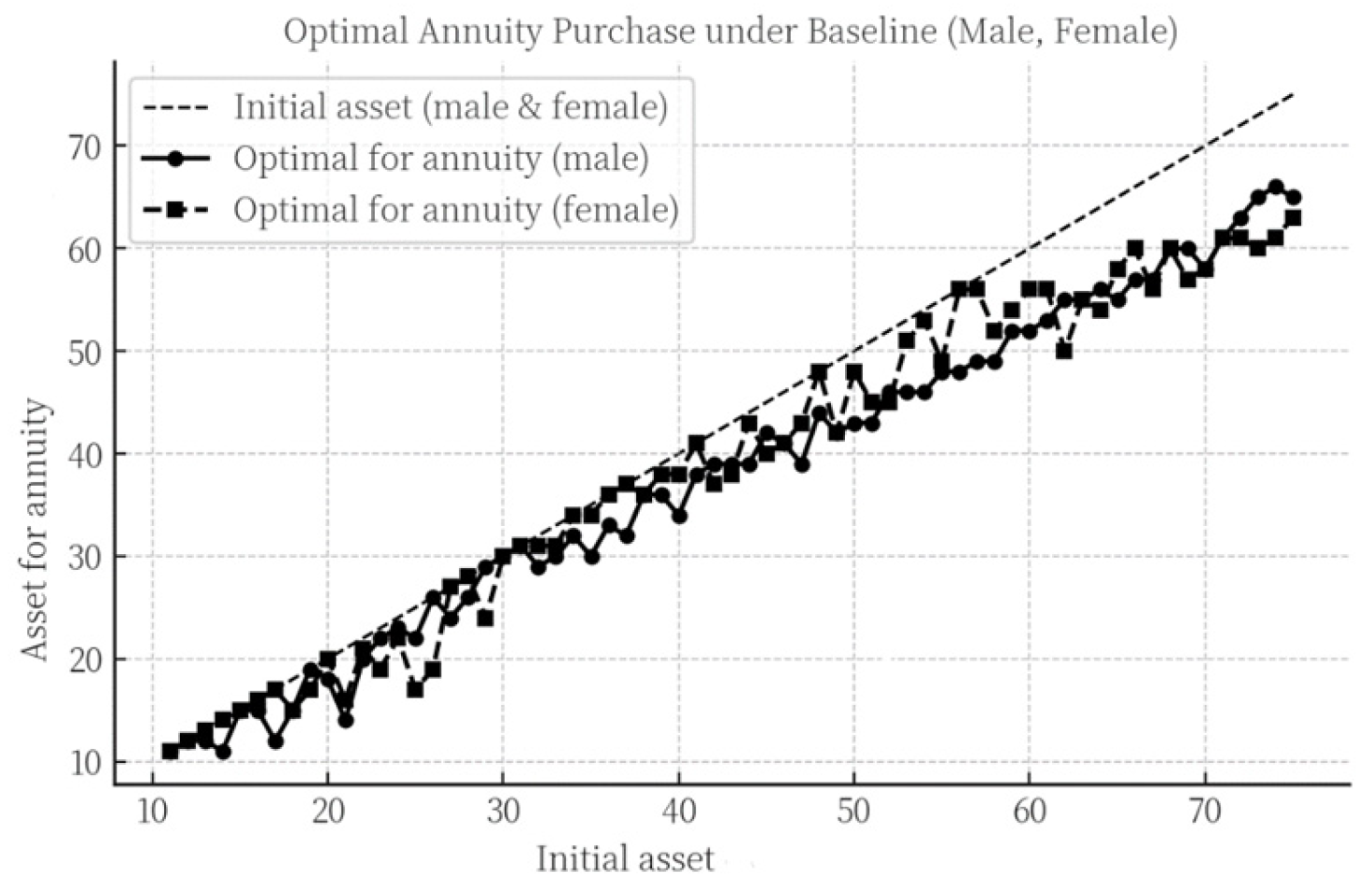

4.1. Baseline Scenario

4.1.1. Annuity Purchase Decisions Under the Baseline Scenario

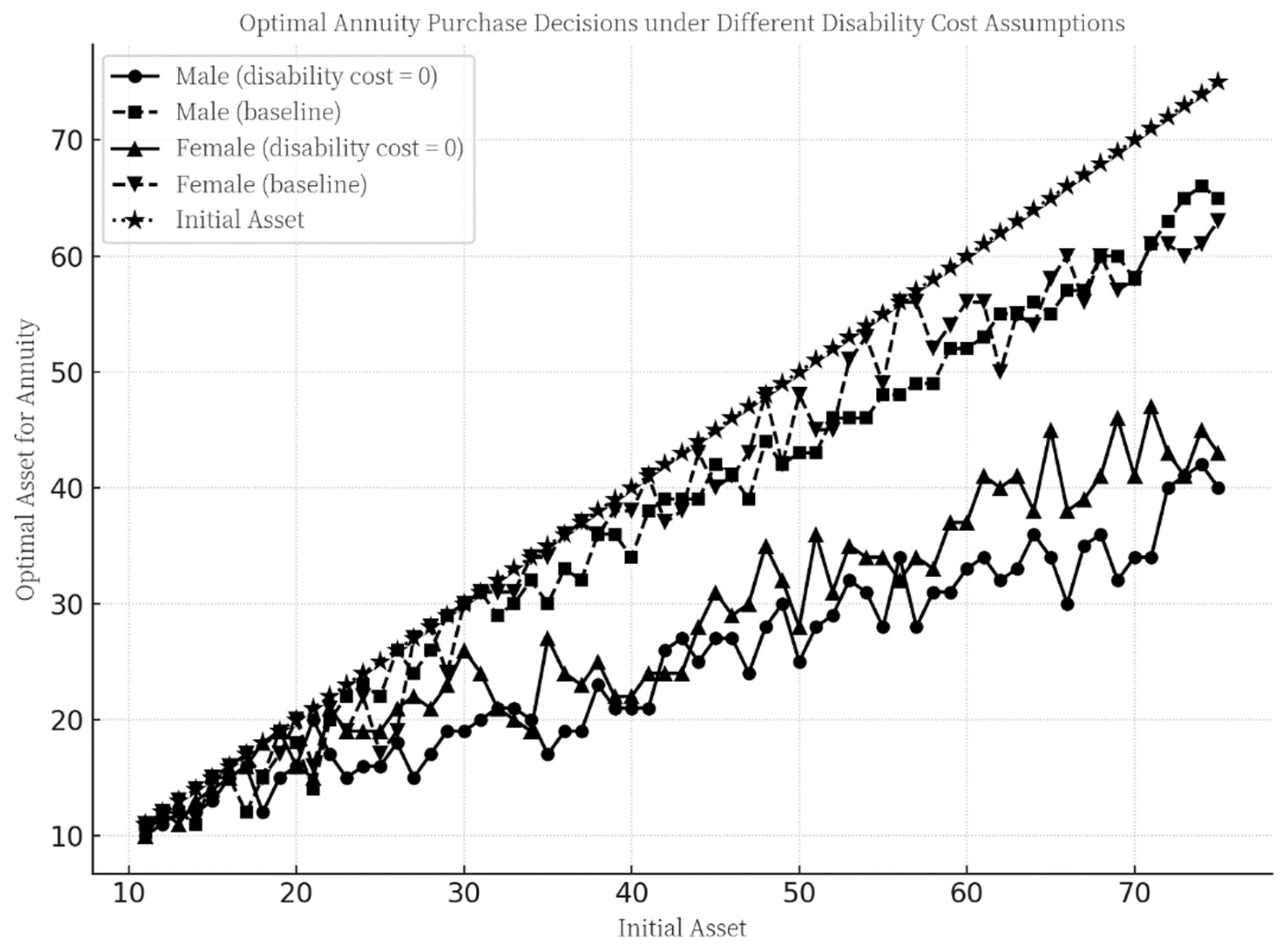

4.1.2. Impact of Disability-Related Health Costs on Annuity Purchase Decisions Under the Baseline Scenario

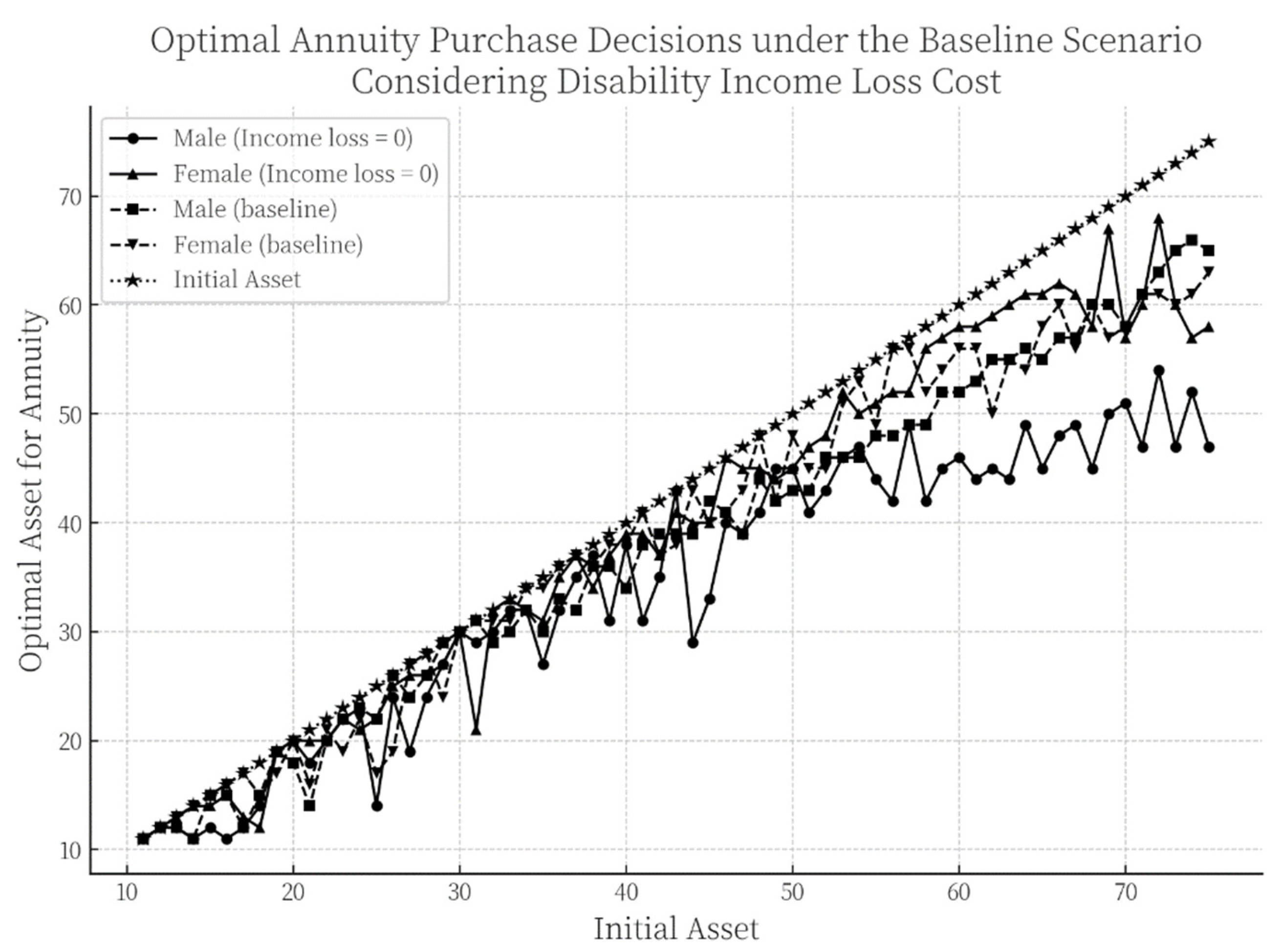

4.1.3. The Impact of Disability-Related Income Loss on Annuity Purchase Decisions Under the Baseline Scenario

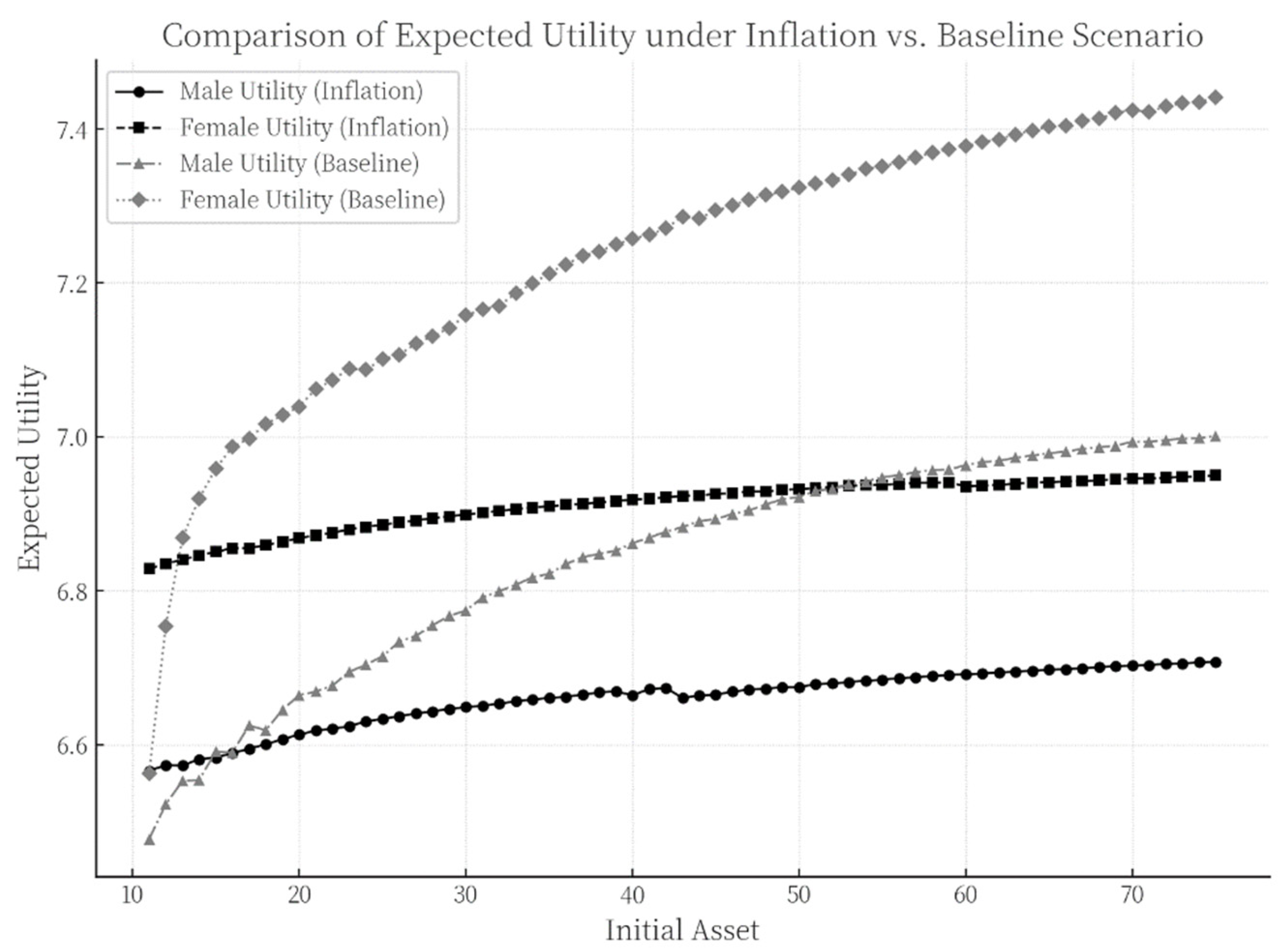

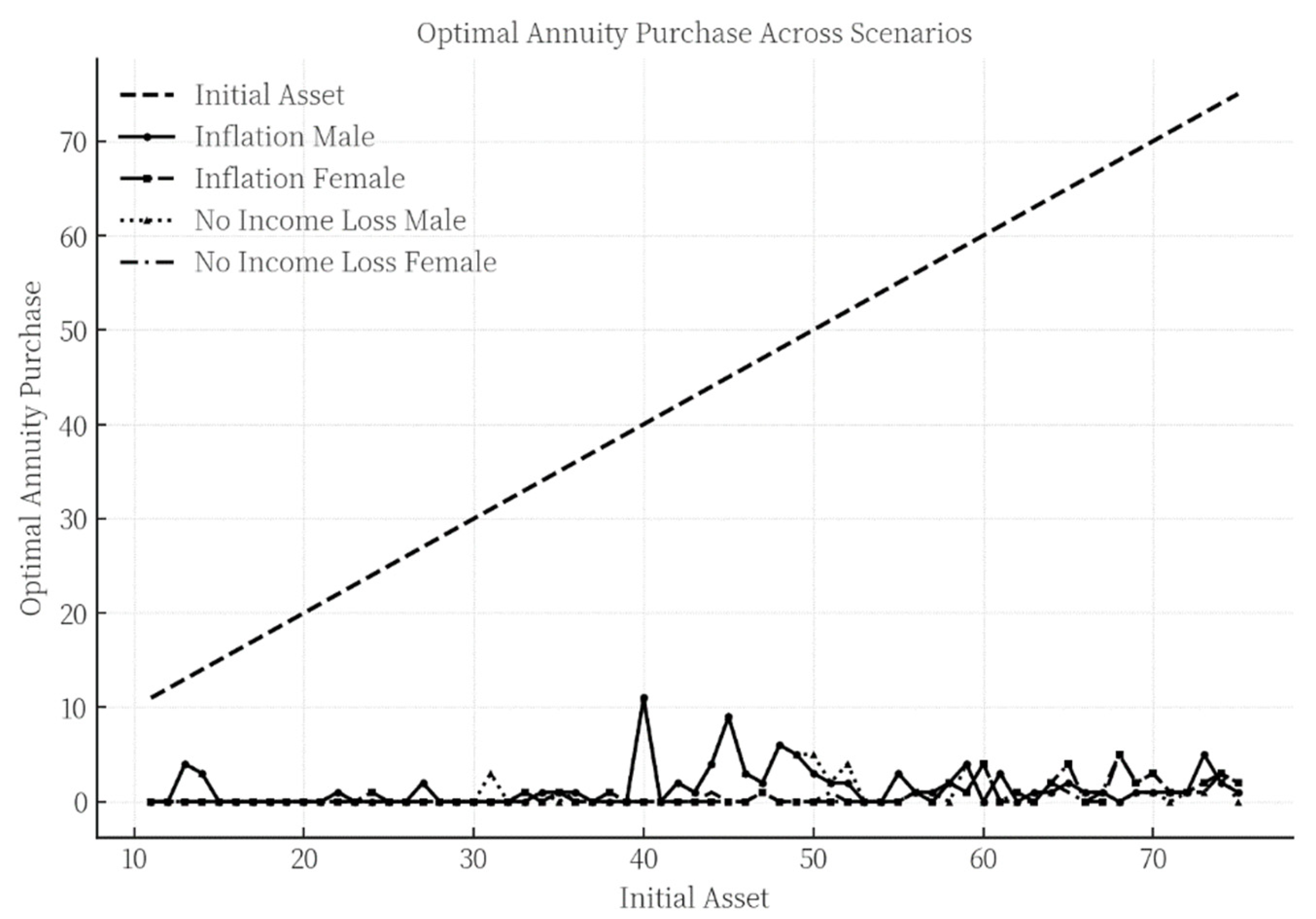

4.2. Model Extension Under Inflation Scenario

4.2.1. Annuity Purchase Decisions Under a Dual-Inflation Scenario

- (1)

- The growth rate of disability-related health costs substantially exceeds both the general inflation rate and the annuity yield. This implies that even if individuals invest in annuities, the returns are insufficient to hedge against the financial risks posed by high future health expenditures. With continuously rising medical costs—particularly in the context of a rapidly aging population—the need for health protection becomes increasingly urgent. While annuities can provide certain financial security, their protective effect is limited in the face of rapidly escalating health expenses. Consequently, individuals tend to prioritize allocating resources to mitigate potential disability risks, thereby reducing investment in annuities to avoid future financial distress caused by high health costs.

- (2)

- The annuity yield offers only a limited advantage over the inflation rate, making it difficult for annuity products to provide additional compensatory expected utility to purchasers. This further diminishes individuals’ willingness to purchase annuity insurance.

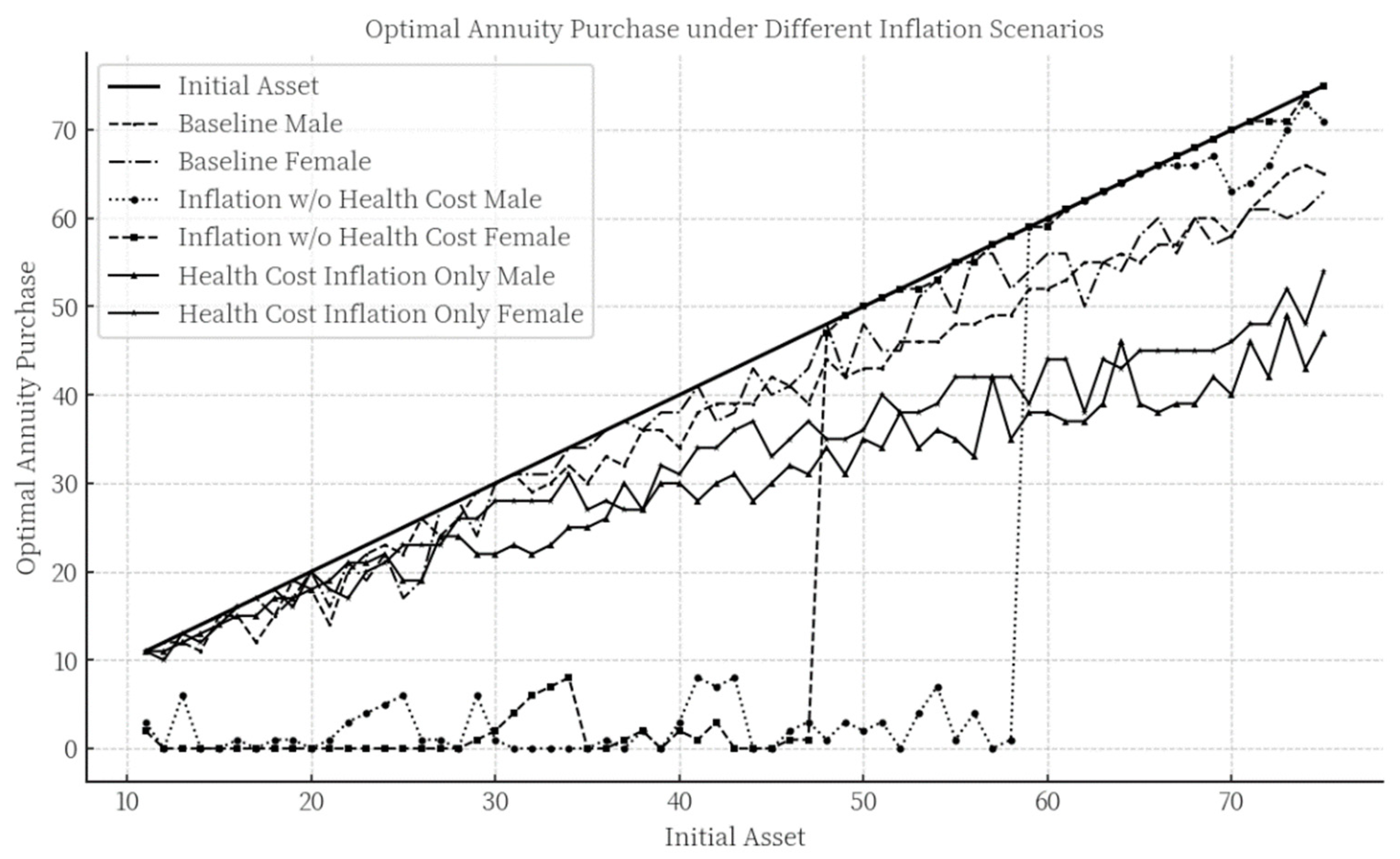

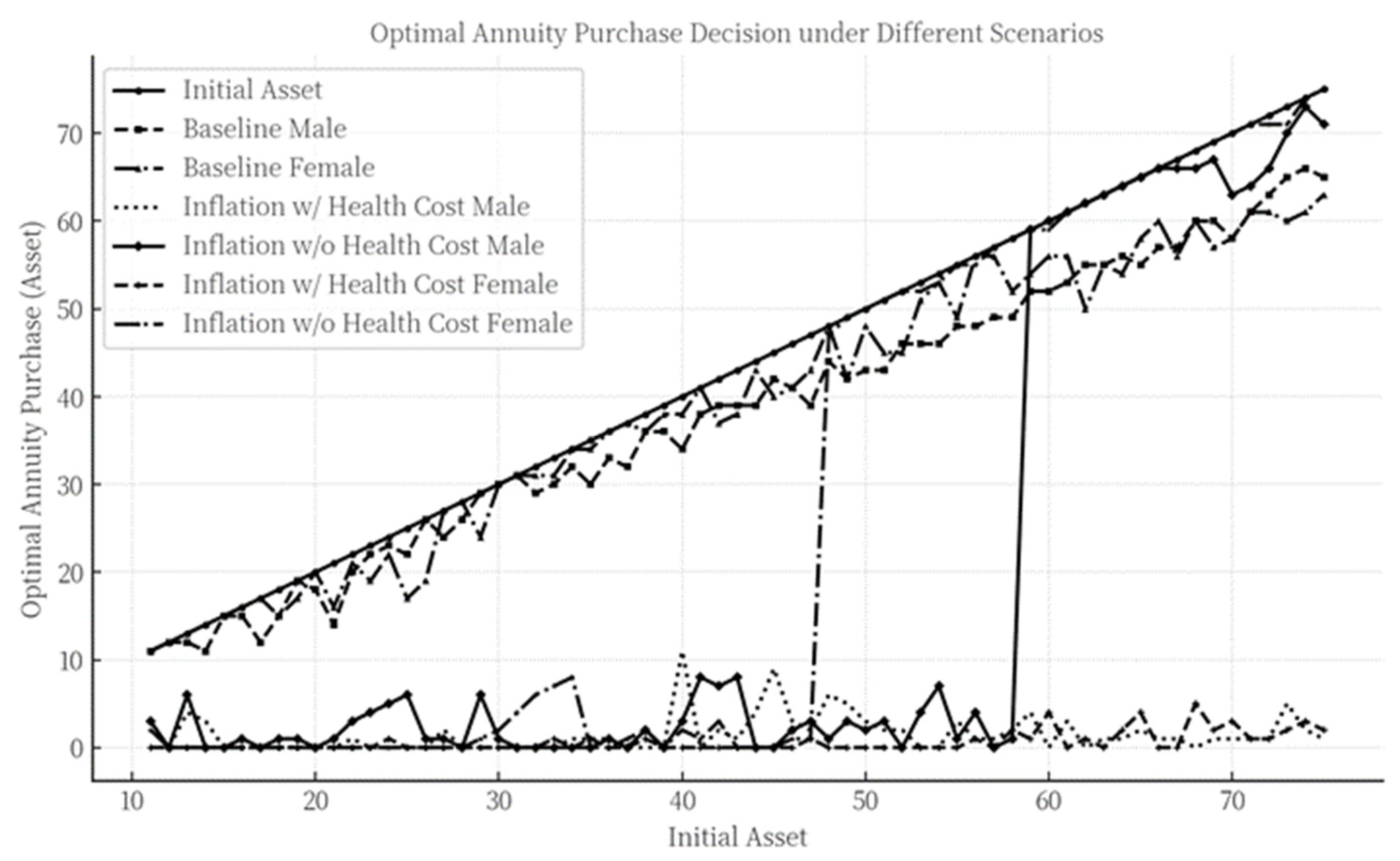

4.2.2. Optimal Annuity Purchase Decisions Under a Single-Inflation Scenario

4.2.3. The Impact of Disability-Related Health Costs on Annuity Purchase Decisions Under Inflation Scenarios

4.2.4. The Impact of Disability-Related Income Loss on Annuity Purchase Decisions Under Inflation Scenarios

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations for Optimizing Annuity Products

5.2.1. Differentiated Product Design to Meet Layered Needs

5.2.2. Institutional Contingency Plans for Zero Inflation Scenarios

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 1061 | 38,740.07 | 50,581.55 | 10,000.44 | 726,434.4 |

| Initial Assets | 1061 | 451,589.8 | 761,636.3 | 10,069.67 | 8,623,458 |

| Variables | Estimated Coefficients | Standard Deviation | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3122366 | 0.0140144 | 0.000 | |

| Constant | 6.431887 | 0.1720796 | 0.000 |

| Two-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 46–55 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly Disabled | Severely Disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.9034 | 0.8261 | 0.0654 | 0.1196 | 0.0254 | 0.0519 | 0.0058 | 0.0024 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.6875 | 0.5855 | 0.1875 | 0.2565 | 0.1094 | 0.1554 | 0.0156 | 0.0026 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.3784 | 0.3267 | 0.2072 | 0.1633 | 0.3784 | 0.4821 | 0.0360 | 0.0279 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Two-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 56–65 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.8254 | 0.7613 | 0.1138 | 0.1528 | 0.0487 | 0.0790 | 0.0121 | 0.0069 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.5841 | 0.5000 | 0.2389 | 0.2857 | 0.1327 | 0.2068 | 0.0442 | 0.0075 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.2137 | 0.2121 | 0.1694 | 0.2283 | 0.5282 | 0.5313 | 0.0887 | 0.0283 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Two-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 66–75 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.7547 | 0.6596 | 0.1541 | 0.1974 | 0.0621 | 0.1238 | 0.0292 | 0.0192 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.4645 | 0.4357 | 0.2663 | 0.2946 | 0.2041 | 0.2448 | 0.0651 | 0.0249 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.1311 | 0.1621 | 0.1860 | 0.1971 | 0.5427 | 0.5838 | 0.1402 | 0.0571 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Two-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 76–85 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.6082 | 0.5652 | 0.1881 | 0.2174 | 0.1285 | 0.1696 | 0.0752 | 0.0478 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.2973 | 0.3086 | 0.3108 | 0.3025 | 0.2905 | 0.3333 | 0.1014 | 0.0556 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.1415 | 0.1051 | 0.1317 | 0.1797 | 0.4585 | 0.5593 | 0.2683 | 0.1559 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Five-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 46–55 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly Disabled | Severely Disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.8613 | 0.7547 | 0.0785 | 0.1404 | 0.0433 | 0.0963 | 0.0169 | 0.0085 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.8075 | 0.6996 | 0.0927 | 0.1512 | 0.0686 | 0.1370 | 0.0312 | 0.0122 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.6912 | 0.5783 | 0.1193 | 0.1535 | 0.1278 | 0.2205 | 0.0617 | 0.0477 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Five-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 56–65 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.7364 | 0.6477 | 0.1308 | 0.1821 | 0.0905 | 0.1499 | 0.0422 | 0.0203 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.6524 | 0.5755 | 0.1359 | 0.1969 | 0.1248 | 0.2029 | 0.0868 | 0.0247 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.4411 | 0.4417 | 0.1431 | 0.2091 | 0.2490 | 0.2953 | 0.1668 | 0.0539 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Five-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 66–75 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.6131 | 0.5074 | 0.1681 | 0.2117 | 0.1264 | 0.2236 | 0.0924 | 0.0573 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.4961 | 0.4484 | 0.1688 | 0.2128 | 0.1831 | 0.2693 | 0.1520 | 0.0695 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.2934 | 0.3226 | 0.1587 | 0.2017 | 0.2801 | 0.3597 | 0.2678 | 0.1161 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Five-Year Health State Transition Probability Matrix for Ages 76–85 | |||||||||

| Terminal | Healthy | Mildly disabled | Severely disabled | Death | |||||

| Initial | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Healthy | 0.3933 | 0.3583 | 0.1794 | 0.2107 | 0.2003 | 0.2817 | 0.2269 | 0.1494 | |

| Mildly disabled | 0.3015 | 0.2887 | 0.1685 | 0.2039 | 0.2377 | 0.3277 | 0.2923 | 0.1797 | |

| Severely disabled | 0.1942 | 0.1880 | 0.1194 | 0.1698 | 0.2177 | 0.3425 | 0.4687 | 0.2997 | |

| Death | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

References

- Yaari, M.E. Uncertain lifetime, life insurance, and the theory of the consumer. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1965, 32, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaus, S. Annuities make a comeback. J. Pension Benefits Issues Adm. 2005, 12, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Inkmann, J.; Lopes, P.; Michaelides, A. How deep is the annuity market participation puzzle? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 279–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F.; Brumberg, R. Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-Section Data. In Post-Keynesian Economics; Kurihara, K.K., Ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1954; pp. 388–436. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, P.A. Lifetime Portfolio Selection by Dynamic Stochastic Programming. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1969, 51, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.C. Lifetime Portfolio Selection: The Continuous-Time Case. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1969, 51, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.C. Optimum Consumption and Portfolio Rules in a Continuous-Time Model. J. Econ. Theory 1971, 3, 373–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourinchas, P.-O.; Parker, J.A. Consumption over the Life Cycle. Econometrica 2002, 70, 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, R.G.; Skinner, J.; Zeldes, S.P. Precautionary saving and social insurance. J. Political Econ. 1995, 103, 360–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O.S.; Poterba, J.; Warshawsky, M.; Brown, J. New Evidence on the Money’s Worth of Individual Annuities. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 1299–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardi, M.; French, E.; Jones, J.B. Why do the elderly save? The role of medical expenses. J. Political Econ. 2010, 118, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, F.D. Dependents and the Demand for Life Insurance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1989, 79, 452–467. [Google Scholar]

- Reichling, F.; Smetters, K. Optimal annuitization with stochastic mortality and correlated medical costs. J. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3273–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peijnenburg, K.; Nijman, T.; Werker, B.J.M. Health cost risk: A potential solution to the annuity puzzle. Econ. J. 2017, 127, 1598–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.Z.; Fan, C. The impact of health risks on annuity demand among the elderly in China. Insur. Stud. 2020, 9, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yogo, M. Portfolio Choice in Retirement: Health risk and the demand for annuities, housing, and risky assets. J. Monet. Econ. 2016, 80, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timo, R.L.; Frederik, T.S. Displaced, disliked and misunderstood: A systematic review of the reasons for low uptake of long-term care insurance and life annuities. J. Econ. Ageing 2020, 17, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.D.; Zhou, H.H.; Zhu, Y.M.; Chen, P.W. Longevity and health: A verification based on a state-transition probability model. Stat. Res. 2022, 39, 134–146. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pang, G.; Warshawsky, M. Optimizing the equity-bond-annuity portfolio in retirement: The impact of uncertain health expenses. Insur. Math. Econ. 2010, 46, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.; Brockett, P.L.; Golden, L.L.; Zhu, W. Health state transitions and longevity effects on retirees’ optimal annuitization. J. Risk Insur. 2017, 84, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koijen, R.S.J.; Van Nieuwerburgh, S.; Yogo, M. Health and mortality delta: Assessing the welfare cost of household insurance choice. J. Financ. 2016, 71, 957–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambel, C.; Kraft, H.; Schendel, L.S.; Steffensen, M. Life insurance demand under health shock risk. J. Risk Insur. 2017, 84, 1171–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameriks, J.; Briggs, J.; Caplin, A.; Shapiro, M.D.; Tonetti, C. Long-term-care utility and late-in-life saving. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 2375–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambel, C. Health shock risk, critical illness insurance, and housing services. Insur. Math. Econ. 2020, 91, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Fu, D.S.; Ge, C.J. A dynamic optimization simulation of consumption and investment behavior over the life cycle of Chinese residents. J. Financ. Res. 2006, 21–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.C.; Sun, E.W.; Yu, M.T. Optimal decision of dynamic wealth allocation with life insurance for mitigating health risk under market incompleteness. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 300, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.P. China Aging Report. Dev. Res. 2023, 40, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, P.; Yang, H.Q.; Huang, X.Y. Optimal allocation of personal insurance under health risks. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 32, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. The theory of dynamic programming. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1954, 60, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.D. The method of endogenous gridpoints for solving dynamic stochastic optimization problems. Econ. Lett. 2006, 91, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Deng, R.H. Analysis of the impact of health risk and longevity risk on residents’ optimal annuity and long-term care insurance decisions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Insurance and Risk Management (CICIRM 2023), Guangzhou, China, 12–15 July 2023; pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.J.; Wang, J.Y. Pricing of long-term care insurance based on a Markov Model. Insur. Stud. 2018, 10, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Storesletten, K.; Zilibotti, F. Growing like China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 196–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, C.R.; Wang, W. Excess sensitivity of Chinese household consumption under habit formation: An analysis based on interprovincial dynamic panel data from 1995 to 2005. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2008, 25, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Sun, L.; Yuan, X. Optimal Decision-Making for Annuity Insurance Under the Perspective of Disability Risk. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203290

Xu Z, Sun L, Yuan X. Optimal Decision-Making for Annuity Insurance Under the Perspective of Disability Risk. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203290

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ziran, Lufei Sun, and Xiang Yuan. 2025. "Optimal Decision-Making for Annuity Insurance Under the Perspective of Disability Risk" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203290

APA StyleXu, Z., Sun, L., & Yuan, X. (2025). Optimal Decision-Making for Annuity Insurance Under the Perspective of Disability Risk. Mathematics, 13(20), 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203290