Abstract

The author has just published a theory on first-order differential equations that accounts for the phase-lag and amplification-factor calculations using explicit, implicit, and backward differentiation multistep methods. Eliminating the phase-lag and amplification-factor derivatives, his presentation delves into how the techniques’ effectiveness changes. The theory for determining the phase lag and amplification factor, initially established for explicit multistep techniques, will be extended to the Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae in this work. The effect of the derivatives of these variables on the efficiency of these calculations will be studied. The novel discovered approach’s symplectic form will be considered next. The discussion of numerical experiment findings and some conclusions on the existing methodologies will conclude in this section.

Keywords:

numerical solution; initial value problems (IVPs); open Newton–Cotes; phase-fitting; amplification-fitting; derivative of the phase lag; derivative of the amplification factor; multistep methods MSC:

65L05; 65L06

1. Introduction

The following kind of equation or set of equations:

can be found in several scientific disciplines, including nanotechnology, chemistry, electronics, materials science, astrophysics, and physics. To learn more about the category of equations that have periodic and/or oscillatory solutions, look to the references [1,2].

Many attempts have been undertaken in the last twenty years to find the numerical solution to the given problem or set of equations (for examples, see [3,4,5,6,7], and the related works). If you want to know more about the methods used to solve Equation (1) with solutions that show oscillating behavior, like Quinlan and Tremaine’s [5], have a look at [3,4] and the other works referenced. The numerical techniques that have been published to solve (1) have certain characteristics, the most notable of which is that they usually are multistep or hybrid algorithms. Also, most of these methods were created to solve second-order differential equations numerically. The following research theoretical frameworks are covered, along with the references for each:

- Runge–Kutta and Runge–Kutta–Nyström methods with minimal phase lag, as well as exponentially fitted, trigonometrically fitted, phase-fitted, and amplification-fitted variations in these methods (see [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]).

- Amplification-fitted multistep methods, multistep methods with minimal phase lag, phase-fitted methods and methods that are trigonometrically or exponentially fitted (see [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]).

The theory for constructing first-order IVPs utilizing multistep processes with minimal phase lag or phase-fitted approaches was recently established by Simos and published in [25,26].

To be more precise, he created a theory to compute the phase lag and amplification factor of explicit multistep methods for first-order IVPs [25], as well as of backward differentiation formulae [26]. Saadat et al. [27] have also proposed a theory on the subject of backward differentiation formulae () for second-order IVPs with oscillating solutions. Specifically, methods are notoriously implicit and designed for stiff problems. Both the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted methods may be used for integration intervals that are very lengthy. was the largest integration area for any of the cases in the research [27]. In the range , , or , it would be interesting to see how the given techniques behave. Also, in [28] Saadat et al. developed sixth-order closed Newton–Cotes amplification-fitted methods. The developed methods are closed, i.e., implicit but the intervals of integration used in their examples by the authors are between and . It will be interesting to see the behavior of these methods for intervals or bigger. Also, they are only amplification-fitted with eliminated first and second-order derivatives of the amplification factor. It will be interesting to see the behavior of this method for phase-fitted cases or phase-fitted and amplification-fitted cases with eliminated derivatives of the phase lag and amplification factor.

We will explore Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae (ONCDF) and develop efficient algorithms for this kind of explicit multistep techniques by using the theory that has been developed for first-order IVPs [25]. We will also test how ONCDF performs with first-order IVPs when taking into account vanished phase lag and amplification-factor derivatives.

Here is how the paper is structured:

- Section 2 laid the groundwork for the theory that determines the phase lag and amplification factor of Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae (ONCDF). Since these approaches are part of a particular class of explicit multistep procedures, the theory given in [25] will be used as a basis for developing the general theory. The direct equations for the phase-lag and amplification-factor computations will be generated here.

- Section 3 presents the strategies to reduce or vanish the phase lag and the amplification factor and the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor.

- Section 4 introduces the Open Newton–Cotes differential method that will be used to examine.

- Section 5 investigates the amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of sixth algebraic order with a phase lag of order six.

- Section 6 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order Six.

- Section 7 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order six with vanished the first derivative of the amplification factor.

- Section 8 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order six with the eliminated first derivative of the phase lag.

- Section 9 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order six with the eliminated first derivative of the phase lag and the first derivative of the amplification factor.

- Section 10 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order five with the eliminated first and second derivatives of the amplification factor.

- Section 11 investigates the phase-fitted and amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method of algebraic order four with the eliminated first and second derivatives of the phase lag.

- Section 12 investigates the Open Newton–Cotes differential methods as symplectic integrators.

- Section 13 presents the numerical results.

- Our conclusions are detailed in Section 14.

2. The Theory

2.1. Open Newton–Cotes Differential Techniques: Direct Formulae for Computing the Phase Lag and Amplification Factor

The theory presented in the papers [25,26] laid the groundwork for the direct formulae used to calculate the phase lag and amplification factor of the Newton–Cotes differential methods.

We examine the general version of the Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae:

Based on the problems described in reference (1), we may use the scalar test equation that follows to examine the phase lag and amplification factor of the explicit multistep methods (2).

where h is the step size of the integration, and .

To obtain the solution to the above problem, you may apply the following formula:

The characteristic equation which is associated with the difference equation found in (7) is given by:

Definition 1.

Considering that the theoretical solution of the scalar test Equation (3) for is , which can also be written as (refer to (6)), and that the numerical solution of the scalar test Equation (3) for is , we can define the phase lag as follows:

If and is an approximation value of V derived by the numerical solution, and , then the phase lag order is q.

Considering the following:

we obtain:

To understand the relationship given in the Formula (11), you must use the following lemmas.

Lemma 1.

These relations are true:

For the proof, see [25].

Lemma 2.

This relation holds:

For the proof, see [25].

The possibility of dividing the link (16) into two halves is clearly plausible. Real and Imaginary.

2.1.1. The Real Part

The real part gives:

The above Formula (17) gives:

The phase lag of the Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae may be directly calculated using this formula. In the following sections, we will explain how to obtain the phase lag of the procedure (2).

2.1.2. The Imaginary Part

The imaginary part gives:

The relation (19) gives:

The amplification factor of the Open Newton–Cotes differential methods may be directly calculated using the above direct formula. The process of calculating the amplification factor of the technique (2) will be detailed in the parts that follow.

Definition 2.

The method that has vanished phase lag is called the phase-fitted algorithm.

Definition 3.

The method where the amplification factor is eliminated is called the amplification-fitted.

2.2. The Derivatives of the Phase Lag and Amplification Factor and Their Role on the Effectiveness of Open Newton–Cotes Differential Methods

To eliminate the phase-lag and amplification-factor derivatives, we use the following procedure:

- Differentiation on V is performed on the formulas that were derived in the previous step.

- We ask that the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor, which were calculated in the previous steps, be adjusted to zero.

The derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor may be calculated using the formulae provided in Appendix A. To create these procedures, the Formulae (18) and (20) were differentiated on the set V.

3. Strategies to Reduce or Vanish the Phase Lag and the Amplification Factor and the Derivatives of the Phase Lag and the Amplification Factor

This paper will provide strategies for reducing or vanishing the phase lag, the amplification factor, as well as the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor for the Open Newton–Cotes differential methods.

More specifically, we will be outlining strategies for

- Minimization of the phase lag;

- Vanishing the phase lag;

- Vanishing the amplification factor;

- Vanishing the derivative of the phase lag;

- Vanishing the derivative of the amplification factor;

- Vanishing the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor.

We note here that all the above strategies contain an amplification-fitted Open Newton–Cotes differential method.

4. Open Newton–Cotes Differential Methods

We will provide an Open Newton–Cotes differential approach as a basis for the strategies to vanish phase lag, amplification factor, phase-lag derivatives, and amplification-factor derivatives.

We will examine the following version of the Open Newton–Cotes differential method:

When the following conditions occur:

we have the known Open Newton–Cotes differential approach of sixth algebraic order, which will be referred to as the Classical Case from here on.

The Classical Case has a local truncation error () given by:

where is the j-th derivative of Y.

5. Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Sixth Algebraic Order with Phase Lag of Order Six

Taking into account the procedure (21) with:

5.1. A Strategy for Minimizing the Phase Lag

This is the process that reduces the phase lag:

- Vanishing the amplification factor.

- Execute the phase-lag computation using the coefficient derived from the preceding stage.

- The previously found phase lag is extended by using the Taylor series.

- Find the set of equations that minimizes the phase lag.

- Define the coefficients solving the system of equations of the previous step.

The following is the result of using the aforementioned strategy:

5.2. Vanishing the Amplification Factor

By using the approach (21) with coefficients provided by (26), we are able to obtain the following result from the direct formula for computing the amplification factor (20):

where the amplification factor is represented by and

Seeking to have the amplification factor vanish or to have yields:

where

The following is achieved by combining the coefficients from (26) with the direct formula for computing the phase lag from (18), as well as the coefficient from (30):

where:

and represents the phase lag.

The following might be obtained by applying the Taylor series to the expansion of the Formula (31):

where are given in Appendix B.

Reducing the phase lag to its minimum value yields the following set of equations:

where

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

We mention that may be expressed as a Taylor series expansion:

Remark 1.

The above method is a second algebraic order Open Newton–Cotes differential method which was not efficient results in the problems where we have applied it.

6. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six

We take into account the procedure (21) with:

The following outcome is obtained by using the direct formulae for the computation of the phase lag and amplification factor (18) and (20), respectively:

where

and stands for the amplification factor, while is the phase lag.

By demanding that the phase lag and amplification factor vanish, or and , we manage to obtain the following:

where:

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

7. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with Vanished the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

We take into account the procedure (21) with:

Strategy for the Eliminating the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

- The given formula’s first derivative, , is computed.

- We are requesting that the formula from the preceding step be zero, namely .

The following formulae are obtained by applying the direct formulae of the phase lag and amplification factor mentioned earlier (see Formulae (18) and (20)):

where

and stands for the amplification factor, while is the phase lag.

The following outcome is produced by taking the derivative of the amplification factor:

where stands for the derivative of the amplification factor, and are given in the Appendix C.

By demanding that the phase lag, amplification factor and the derivative of the amplification factor vanish, or , , and , we manage to obtain the following:

where the formulae are in Appendix D.

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, and is the first derivative of the amplification factor.

8. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with the Eliminated First Derivative of the Phase Lag

Strategy for the Eliminating the First Derivative of the Phase Lag

- The phase lag formula’s first derivative, , is computed.

- We are requesting that the formula from the preceding step be zero, namely .

By applying the direct formulae of the phase lag and amplification factor mentioned earlier (see Formulae (18) and (20)) to the method (55), we obtain Formulae (56) and (57).

The following outcome is produced by taking the derivative of the phase lag:

where

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, and is the first derivative of the phase lag.

By demanding that the phase lag, amplification factor and the derivative of the phase lag vanish, or , , and , we manage to obtain the following:

where the formulae are in Appendix E.

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, and is the first derivative of the phase lag.

9. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with the Eliminated First Derivative of the Phase Lag and the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

We take into account the procedure (21) with:

Strategy for the Elimination of the First Derivative of the Phase Lag and the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

- We determine , which is the first derivative of the formula given above.

- We determine , which is the first derivative of the formula given above.

- For the preceding stages, we are requesting that the equations be zero, meaning that and .

Based on the above strategy, we obtain the following:

where the formulae are in Appendix F, and is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the phase lag, and is the first derivative of the amplification factor.

By demanding that the phase lag, amplification factor, the derivative of the phase lag vanish, the derivative of the amplification factor vanishes or , , , and , we manage to obtain the following:

where the formulae are given in Appendix G.

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the phase lag, and is the first derivative of the amplification factor.

10. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Five with the Eliminated First and Second Derivatives of the Amplification Factor

Strategy for the Elimination of the First and Second Derivatives of the Amplification Factor

- We determine and , which is the first and second derivatives of the formula given above.

- For the preceding stages, we are requesting that the equations be zero, meaning that , and .

Based on the above strategy, we obtain the following:

where the formulae are in Appendix H, and is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the amplification factor, and is the second derivative of the amplification factor.

By demanding that the phase lag, amplification factor, and the first and second derivatives of the amplification factor vanish or , , , and , we manage to obtain the following:

where the formulae are given in Appendix I.

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the amplification factor, and is the second derivative of the amplification factor.

11. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Four with the Eliminated First and Second Derivatives of the Phase Lag

Strategy for the Elimination of the First and Second Derivatives of the Phase Lag

- We determine and , which is the first and second derivatives of the formula given above.

- For the preceding stages, we are requesting that the equations be zero, meaning that , and .

Based on the above strategy, we obtain the following:

where the formulae are in Appendix K, and is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the phase lag, and is the second derivative of the phase lag.

By demanding that the phase lag, amplification factor, and the first and second derivatives of the phase lag vanish or , , , and , we manage to obtain the following:

where the formulae are given in Appendix L.

When these formulae are subjected to the Taylor series, the outcome is as follows:

The features of this cutting-edge algorithm are as follows:

where is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, is the first derivative of the phase lag, and is the second derivative of the phase lag.

Remark 2.

Based on Table 1, it is easy to see that for all the produced methods are equivalent to the classical Open Newton–Cotes formula of sixth algebraic order.

Table 1.

Methods developed and presented in Section 4, Section 5, Section 6, Section 7, Section 8, Section 9, Section 10 and Section 11.

Table 1.

Methods developed and presented in Section 4, Section 5, Section 6, Section 7, Section 8, Section 9, Section 10 and Section 11.

| Method | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical—Section 4 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Section 5 | + … | 0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Section 6 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Section 7 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | |

| Section 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | |

| Section 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| Section 10 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | |

| Section 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - |

Where:

and is the phase lag, is the amplification factor, , , , and .

12. Open Newton–Cotes Differential Methods as Symplectic Integrators

Let us consider the Hamilton’s equations of motion which are linear in position q and momentum p

where is a constant scalar or matrix.

Let us consider the following discrete scheme:

where is the discretization’s transformation matrix, and , , , and are permutations of a finite difference method’s coefficients for which is applied to an integration interval . The following is the form of the -step approximation to the solution if the finite difference approach is constantly used to the integration interval , which is split into N equal intervals of size h (the integration step):

The matrix

is the transformation matrix of the discretization. Based on the above, the discrete transformation can be written as:

Definition 4.

A discrete scheme is a symplectic scheme if the transformation matrix Λ is symplectic.

Definition 5.

A matrix K is symplectic if where

Remark 3.

The product of symplectic matrices is also symplectic.

Based on the above remark, we have:

Remark 4.

The transformation matrix Λ is symplectic if every matrix is symplectic.

Thus, if every matrix is symplectic, then the discrete scheme (121) is symplectic.

Let us consider the Open Newton–Cotes differential scheme (21) which we study in this paper. We can rewrite this scheme as follows:

Application of the above method to the Hamilton’s equations of motion (117) leads to the following formulae:

where .

- Step 1

Considering the relations mentioned in [29]:

We carry out the following:

- We apply the above relations for .

- We solve the resulting system of equations for and .

The above algorithm leads us to:

- Step 2

We carry out the following:

- We solve the resulting system of equations and .

The above algorithm leads us to:

Step 3

We solve the resulting system of equations and .

The above algorithm leads us to:

Step 4

We solve the resulting system of equations and .

The above algorithm leads us to:

- Step 5

Now, we carry out the following:

- We substitute and from the Step 1 above;

- We solve the resulting system to obtain and ;

- We substitute and from the Step 1 above;

- We solve the resulting system to obtain and ;

- We substitute and from the Step 1 above;

- We solve the resulting system to obtain and ;

The above algorithm leads us to:

The above equations can be written as:

The above formulae give the following:

The above relation gives:

where

For the matrix given above we have:

where J is given by (120), and

where are given in the Appendix L.

Based on Definition 5, in order the above matrix to be symplectic, must be equal 1.

We will examine how the Open Newton–Cotes differential schemes which have been produced in this paper fit on the above theory.

12.1. Classical Open Newton–Cotes Formula (21) with Coefficients Given by (22)

Application of the classical method to the above theory and taking the Taylor series expansion for leads to:

12.2. Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Sixth Algebraic Order with Phase Lag of Order Six

Applying the method from Equation (39) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.3. Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Sixth Algebraic Order with Phase Lag of Order Six

Applying the method from Equation (54) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.4. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with Vanished the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

Applying the method from Equation (67) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.5. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with the Eliminated First Derivative of the Phase Lag

Applying the method from Equation (76) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.6. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Six with the Eliminated First Derivative of the Phase Lag and the First Derivative of the Amplification Factor

Applying the method from Equation (90) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.7. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Five with the Eliminated First and Second Derivatives of the Amplification Factor

Applying the method from Equation (103) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

12.8. Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes Differential Method of Algebraic Order Four with the Eliminated First and Second Derivatives of the Phase Lag

Applying the method from Equation (116) to the previously stated theory and obtaining by the Taylor series expansion results in:

Based on the above Formulae (150)–(157), it is easy for one to see that the variable is near to 1 for all the developed methods. How near to 1 can be, is dependent from the value of , i.e., from the problem, and from the step length of the integration. So, under the above conditions, all the developed methods are almost symplectic integrators.

13. Numerical Results

13.1. Problem of Stiefel and Bettis

The following nearly periodic orbit problem was studied by Stiefel and Bettis [30] and is taken into account here:

The exact solution is

For this problem, we use .

The problem (158) has numerical solutions for 100,000 that have been determined by using the corresponding methods:

- The Open Newton–Cotes scheme presented in Section 4 (Classical Case), which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. I;

- The Runge–Kutta Dormand and Prince fourth order method [14], which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. II;

- The Runge–Kutta Dormand and Prince fifth order method [14], which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. III;

- The Runge–Kutta Fehlberg fourth order method [31], which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. IV;

- The Runge–Kutta Fehlberg fifth order method [31], which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. V;

- The Runge–Kutta Cash and Karp fifth order method [32], which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. VI;

- The Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with phase lag of order 6, which is developed in Section 5, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. VII;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with vanished the first derivative of the amplification factor which is developed in Section 7, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. VIII;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with vanished the first derivative of the phase lag which is developed in Section 8, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. IX;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme which is developed in Section 6, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. X;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with vanished the first and second derivatives of the amplification factor which is developed in Section 10, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. XI;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with vanished the first and second derivatives of the phase lag which is developed in Section 11, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. XII;

- The Phase-Fitted and Amplification-Fitted Open Newton–Cotes scheme with vanished the first derivative of the phase lag and the first derivative of the amplification factor which is developed in Section 9, and which is mentioned as Comput. Meth. XIII.

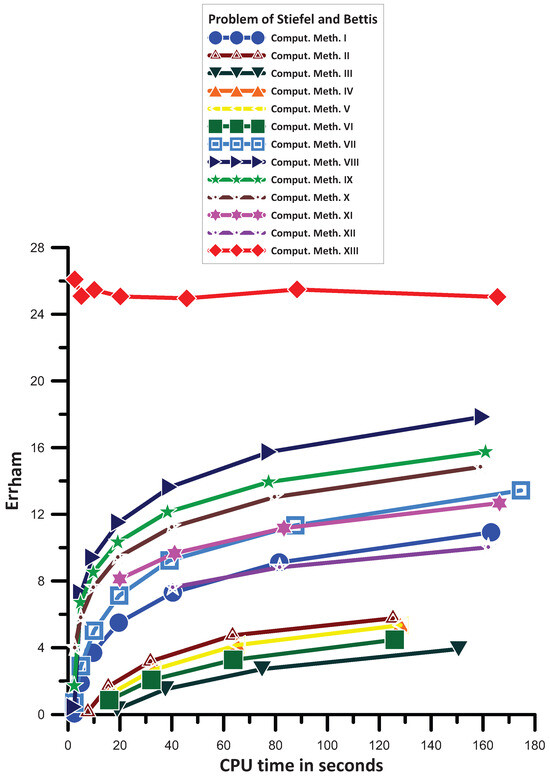

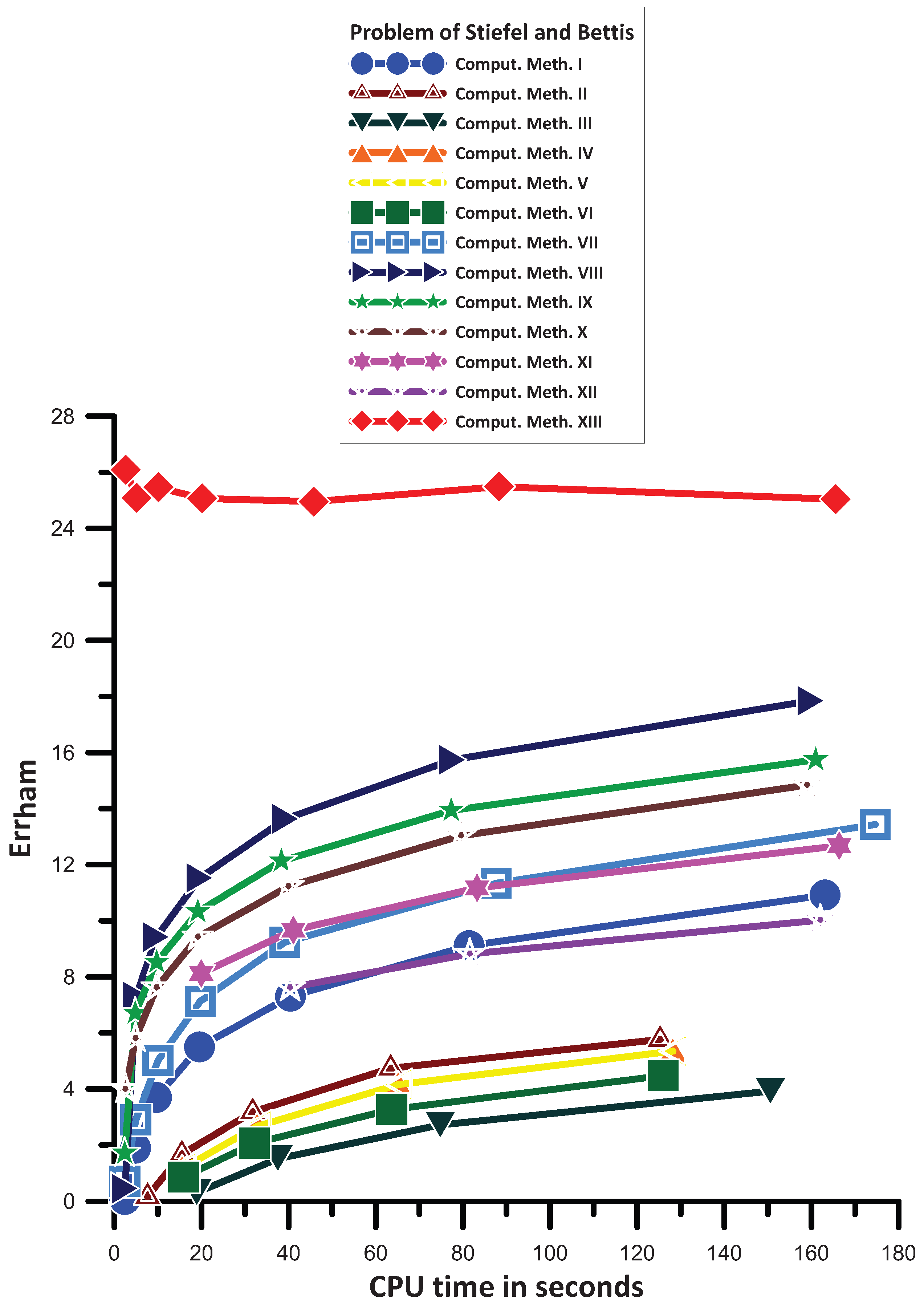

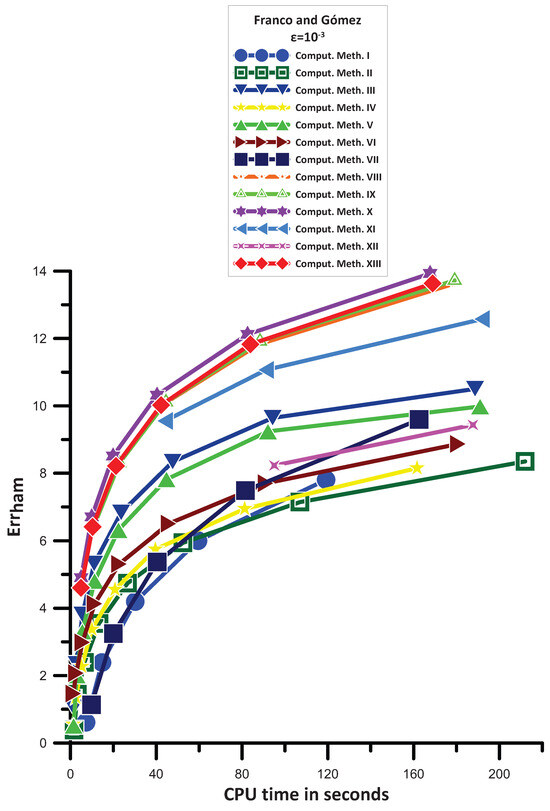

Figure 1 displays the maximum absolute error of the solutions derived from the Stiefel and Bettis [30] problem using each of the numerical techniques previously described.

Figure 1 provides the data that enable us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. VI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III.

- Comput. Meth. IV is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI.

- Comput. Meth. IV has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. V.

- Comput. Meth. II is more efficient than Comput. Meth. IV.

- Comput. Meth. XII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. II.

- Comput. Meth. I is more efficient than Comput. Meth. XII for big step sizes and has generally the same behavior with Comput. Meth. XII for small stepsizes.

- Comput. Meth. VII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. I.

- Comput. Meth. XI has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. X is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. IX is more efficient than Comput. Meth. X.

- Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. IX.

- Finally, Comput. Meth. XIII is the most efficient one.

Figure 1.

Numerical results for the problem of Stiefel and Bettis [30].

Figure 1.

Numerical results for the problem of Stiefel and Bettis [30].

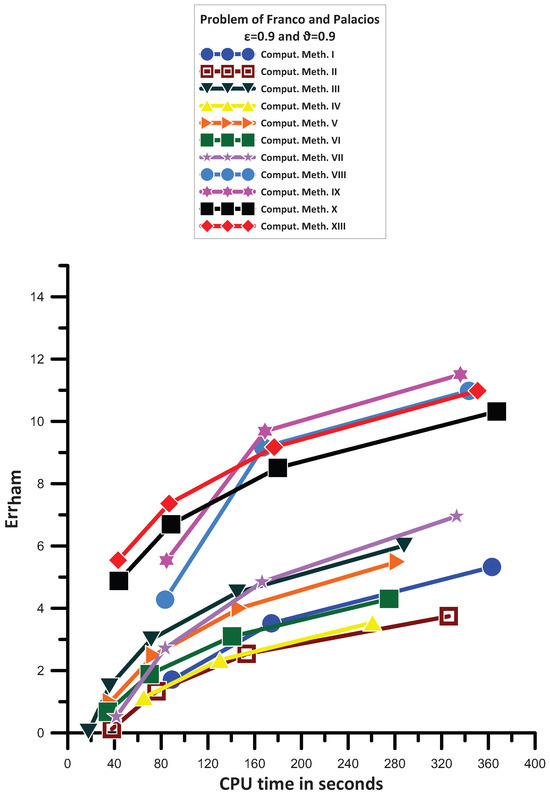

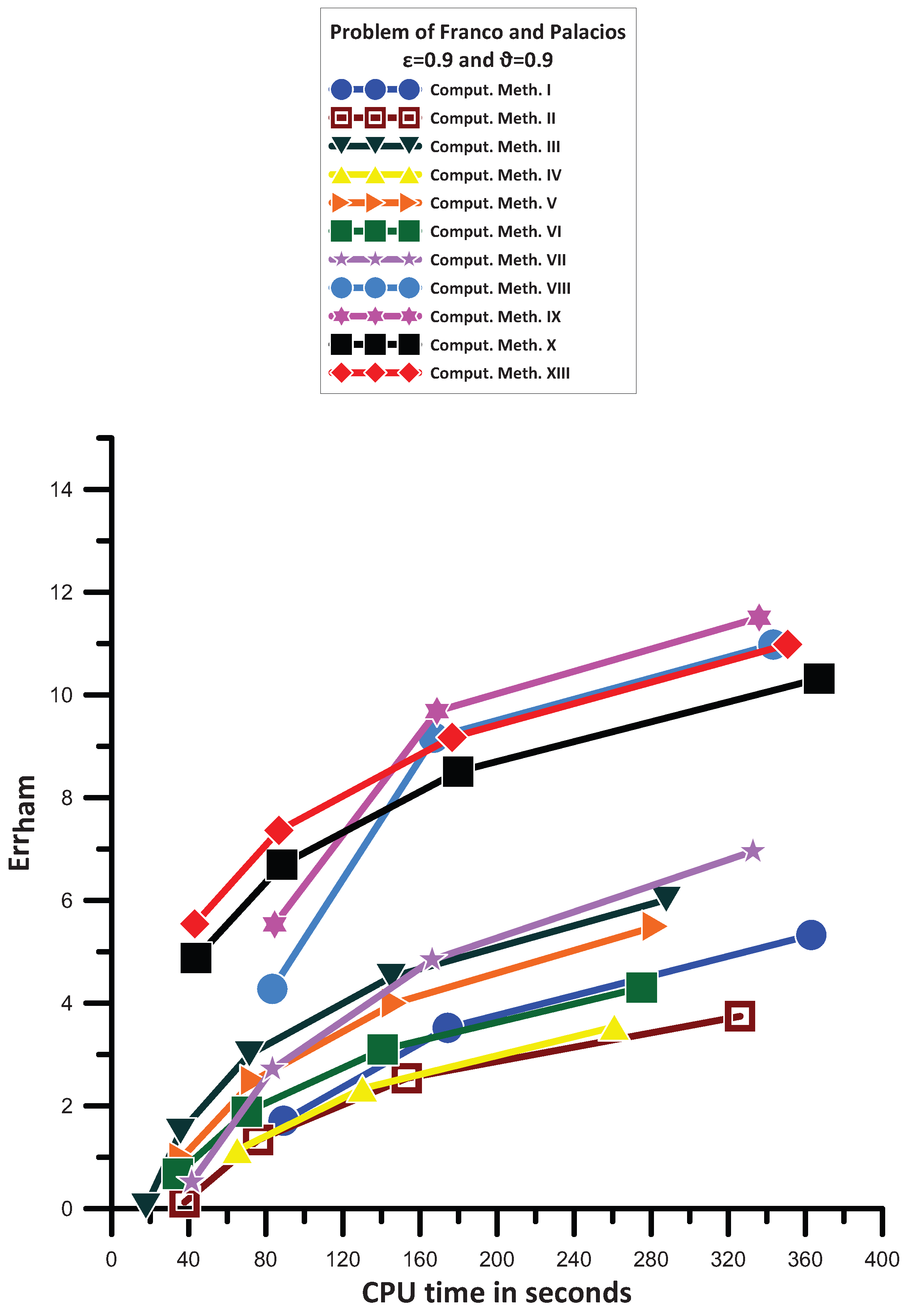

13.2. Problem of Franco and Palacios [33]

The following problem was examined by Franco and Palacios [33] and is taken into account here:

The exact solution is

where and . For this problem, we use .

We have discovered the numerical solution to the system of Equation (160) for 1,000,000 by using the procedures described in Section 12.1.

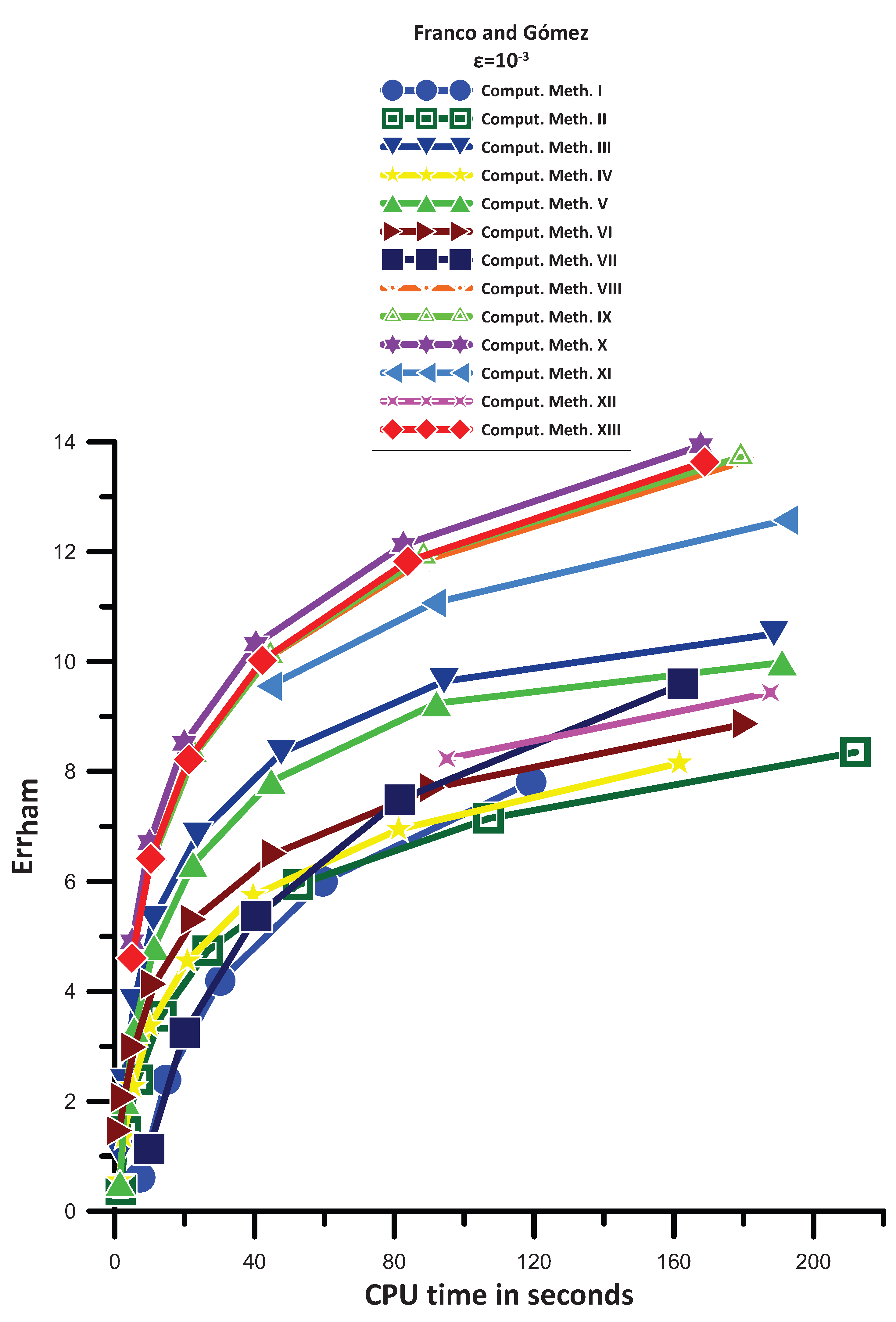

Figure 2 provides the data that enable us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. XI and Comput. Meth. XII are not convergent for the CPU time used in this example.

- Comput. Meth. II has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. IV.

- Comput. Meth. I is more efficient than Comput. Meth. II.

- Comput. Meth. VI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. I for big step sizes while for small step sized has the same, generally, behavior.

- Comput. Meth. V is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI.

- Comput. Meth. III is more efficient than Comput. Meth. V.

- Comput. Meth. VII has a mixed behavior. For big stepsizes is less efficient than Comput. Meth. VI. For medium stepsizes is less efficient than Comput. Meth. III. For small step sizes is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III.

- Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III and Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. X is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VIII for big step sizes. For small step sizes Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. X.

- Comput. Meth. XIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. X and for small step sizes has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. VIII.

- Comput. Meth. IX has a mixed behavior. For big stepsizes is less efficient than Comput. Meth. X. For medium stepsizes is less efficient than Comput. Meth. XIII and more efficient than Comput. Meth. X. For small step sizes is the most efficient one.

Figure 2.

Numerical results for the problem of Franco and Palacios [33].

Figure 2.

Numerical results for the problem of Franco and Palacios [33].

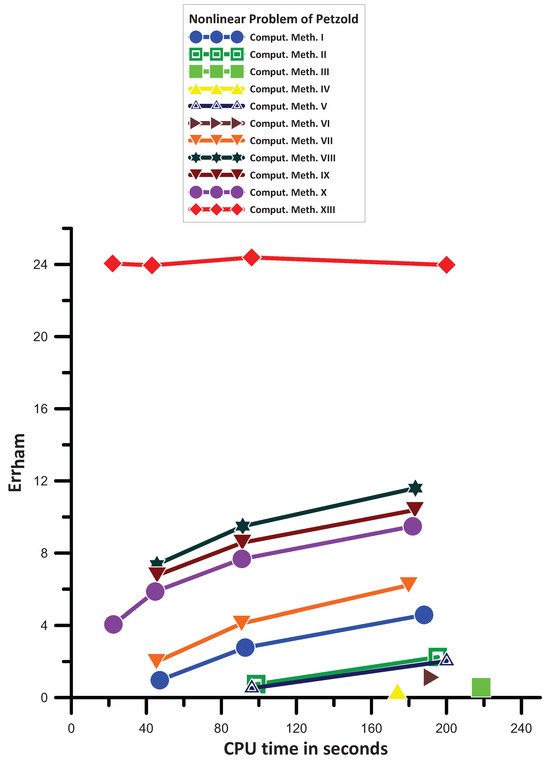

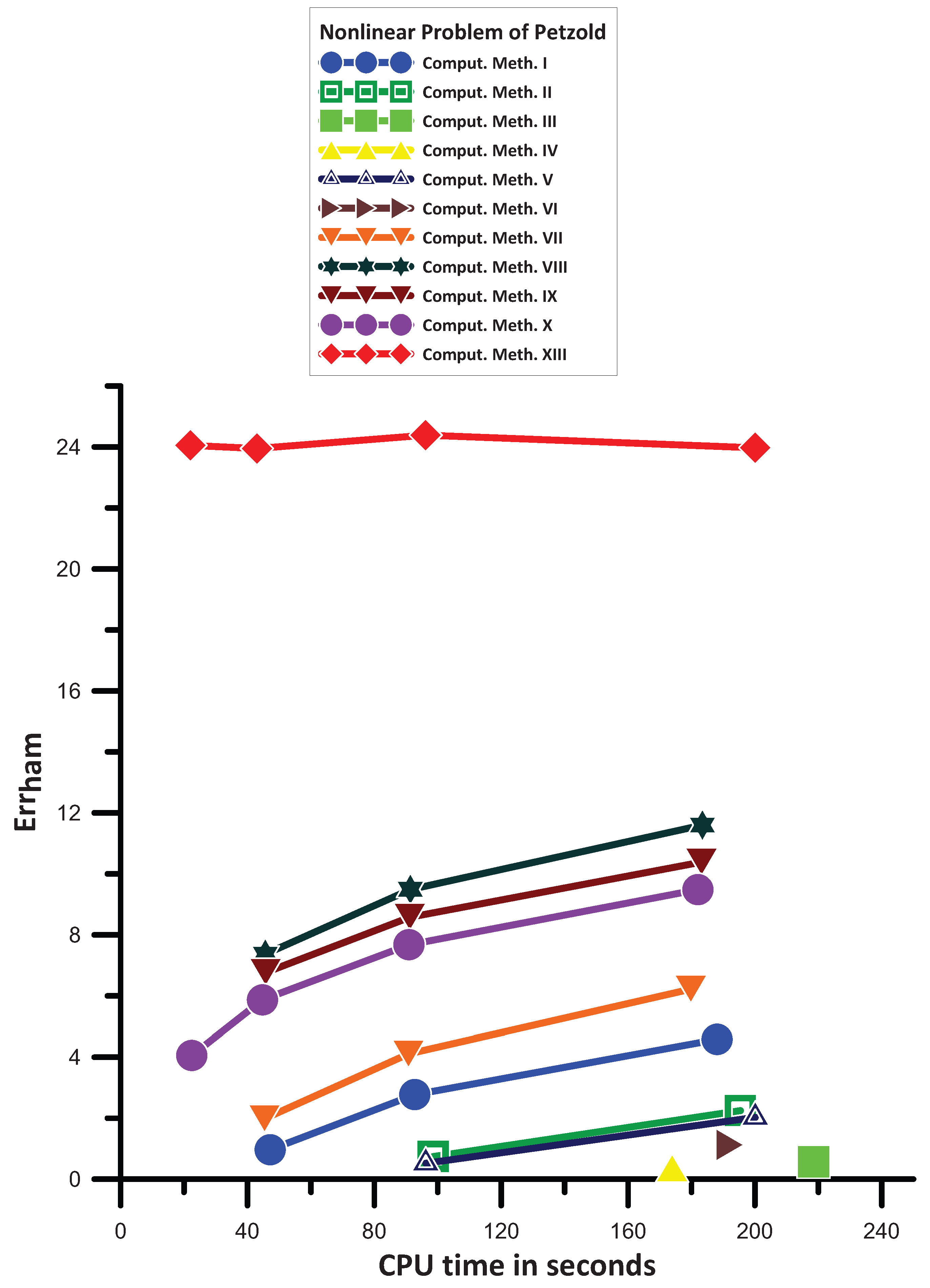

13.3. Nonlinear Problem of Petzold [34]

The following nonlinear problem was examined by Petzold [34] and is taken into account here:

The exact solution is

where , . For this problem, we use .

We have discovered the numerical solution to the system of Equation (162) for by using the procedures described in Section 13.1.

Figure 3 provides the data that enable us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. XI and Comput. Meth. XII are not convergent for the CPU time used in this example.

- Comput. Meth. III has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. IV.

- Comput. Meth. VI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III.

- Comput. Meth. V is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI.

- Comput. Meth. II is more efficient than Comput. Meth. V.

- Comput. Meth. I is more efficient than Comput. Meth. II.

- Comput. Meth. VII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. I.

- Comput. Meth. X is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. IX is more efficient than Comput. Meth. X.

- Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. IX.

- Finally, Comput. Meth. XIII is the most efficient one.

Figure 3.

Numerical results for the nonlinear problem of [34].

Figure 3.

Numerical results for the nonlinear problem of [34].

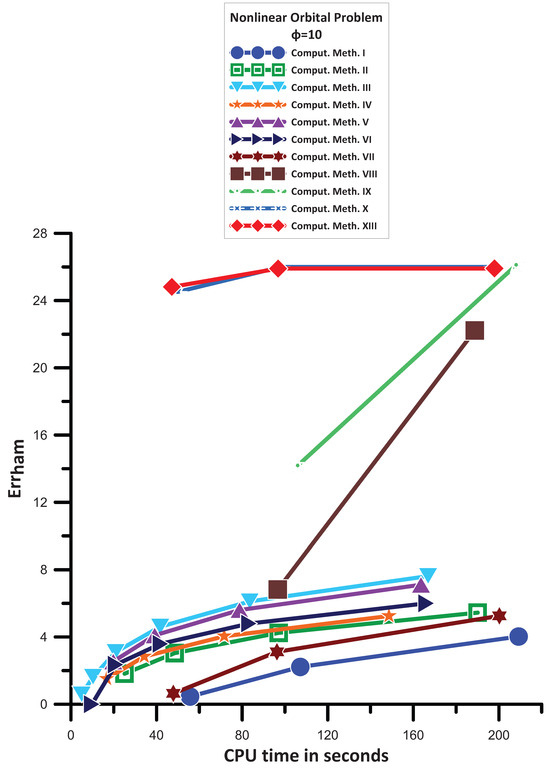

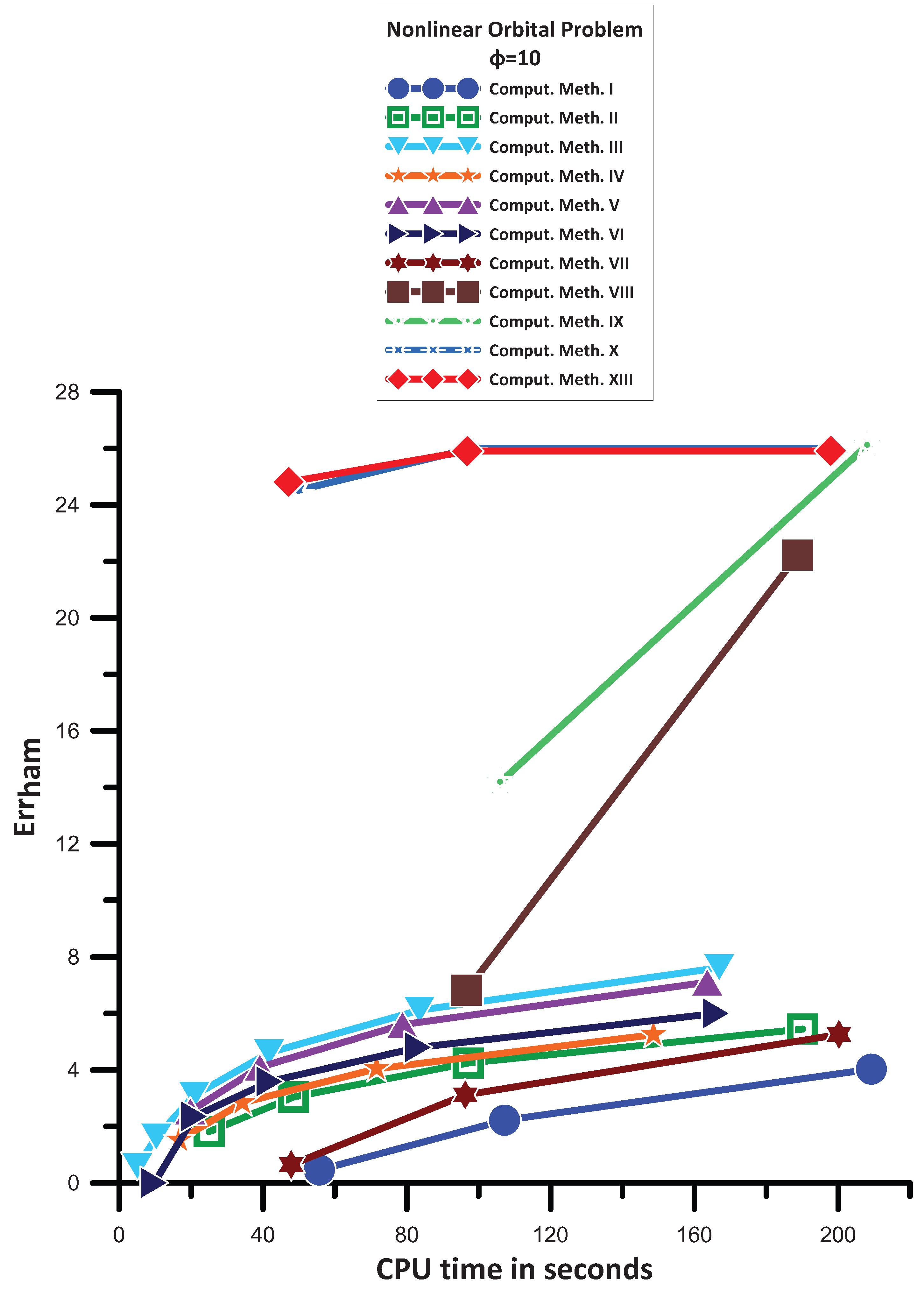

13.4. A Nonlinear Orbital Problem [35]

The following nonlinear orbital problem was examined by Simos in [35] and is taken into account here:

The exact solution is

where . For this problem, we use .

We have discovered the numerical solution to the system of Equation (165) for 100,000 by using the procedures described in Section 13.1.

Figure 4 provides the data that enable us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. XI and Comput. Meth. XII are not convergent for the CPU time used in this example.

- Comput. Meth. VII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. I.

- Comput. Meth. II is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. IV is more efficient than Comput. Meth. II.

- Comput. Meth. VI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. IV.

- Comput. Meth. V is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI.

- Comput. Meth. III is more efficient than Comput. Meth. V.

- Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III.

- Comput. Meth. IX is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VIII.

- Comput. Meth. X has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. XIII. Finally, Comput. Meth. XIII and Comput. Meth. X are the most efficient ones.

Figure 4.

Numerical results for the nonlinear orbital problem of [35].

Figure 4.

Numerical results for the nonlinear orbital problem of [35].

13.5. Problem of Franco and Gómez [36]

Franco and Gómez [36] investigated the following problem, which we take into consideration:

The exact solution is

where . For this problem, we use .

Using the techniques outlined in Section 13.1, the numerical solution to the system of Equation (160) has been found for 1,000,000.

The information in Figure 5 allows us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. II is more efficient than Comput. Meth. I. For small step sizes, Comput. Meth. II is less efficient than Comput. Meth. I.

- Comput. Meth. IV is more efficient than Comput. Meth. II. For small step sizes Comput. Meth. IV is less efficient than Comput. Meth. I.

- Comput. Meth. VII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. IV.

- Comput. Meth. VI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VII. For small step sizes Comput. Meth. VI is less efficient than Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. XII has a mixed behavior. For bigger stepsizes is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI and Comput. Meth. VII. For smaller step sizes is less efficient than Comput. Meth. VII and more efficient than Comput. Meth. VI.

- Comput. Meth. V is more efficient than Comput. Meth. VII.

- Comput. Meth. III is more efficient than Comput. Meth. V.

- Comput. Meth. XI is more efficient than Comput. Meth. III.

- Comput. Meth. VIII is more efficient than Comput. Meth. XI.

- Comput. Meth. IX has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. VIII.

- Comput. Meth. XIII has the same, generally, behavior with Comput. Meth. IX. Consequently, Comput. Meth. VIII, Comput. Meth. IX, and Comput. Meth. XIII have the same, generally, behavior.

- Finally, Comput. Meth. X is the most efficient one.

Figure 5.

Numerical results for the semi–linear problem of Franco and Gómez [36].

Figure 5.

Numerical results for the semi–linear problem of Franco and Gómez [36].

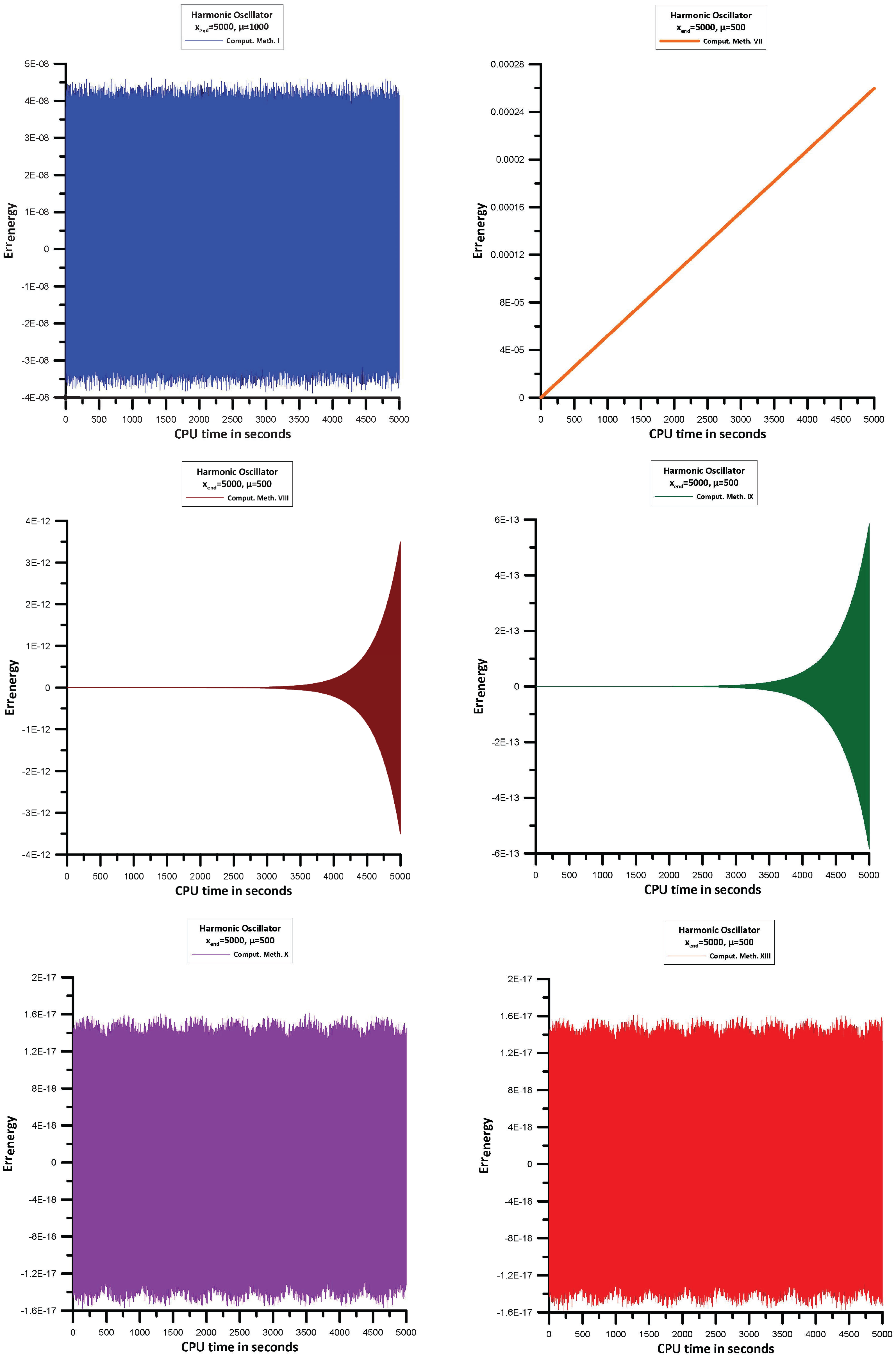

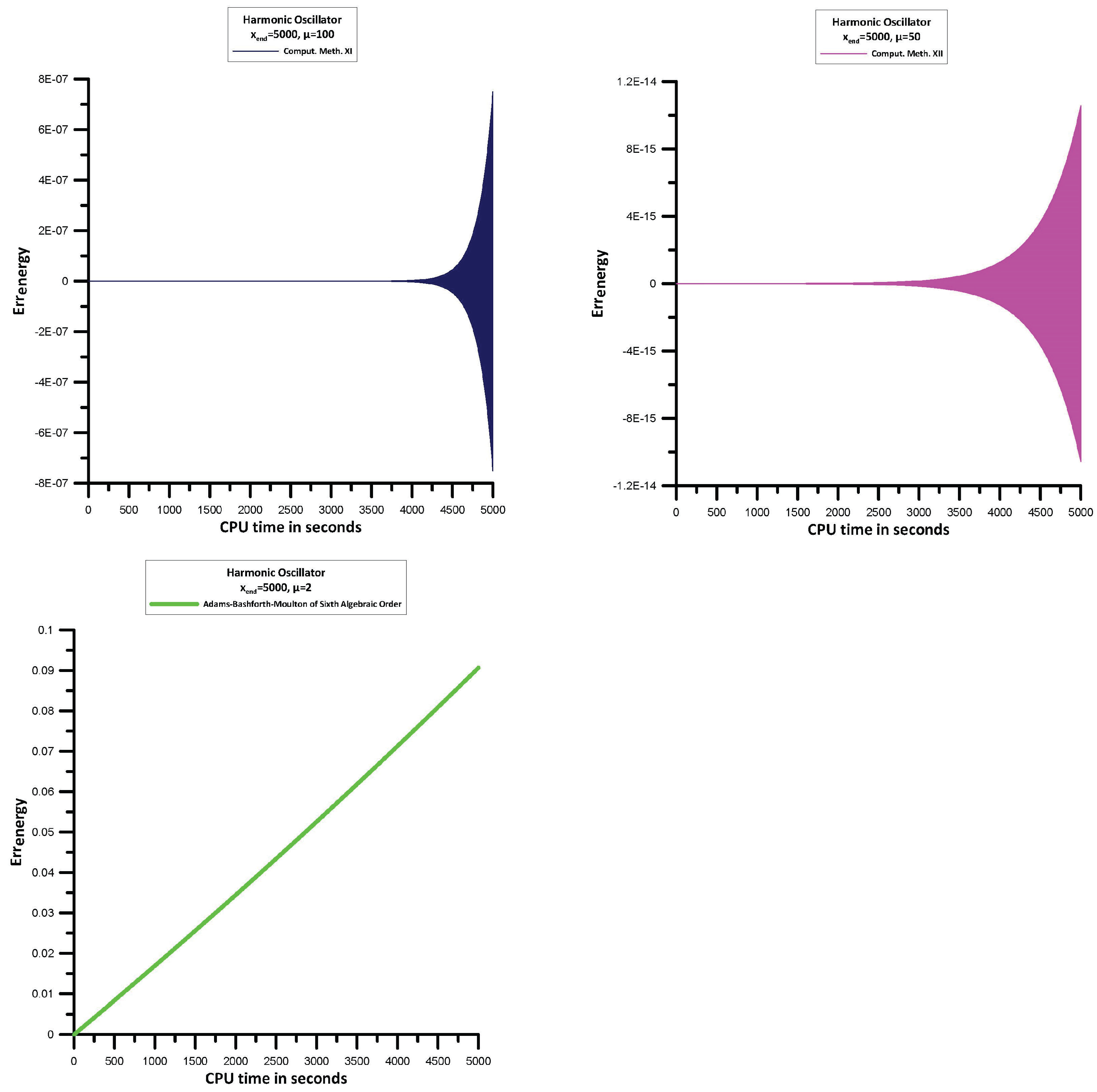

13.6. Hamilton’s Equations of Motion (117)

Let us consider the Hamilton’s equations of motion which are linear in position q and momentum p which are given by Equation (117).

The initial conditions are given by:

The analytical solution of the above problem is given by:

The Hamiltonian (or energy) of this system is given by:

Using the techniques outlined in Section 13.1, we will find the errors of the Hamiltonian:

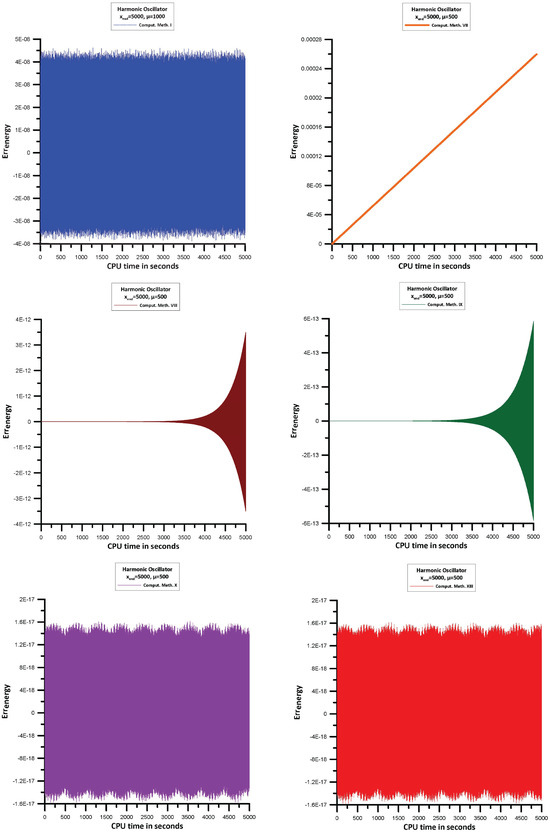

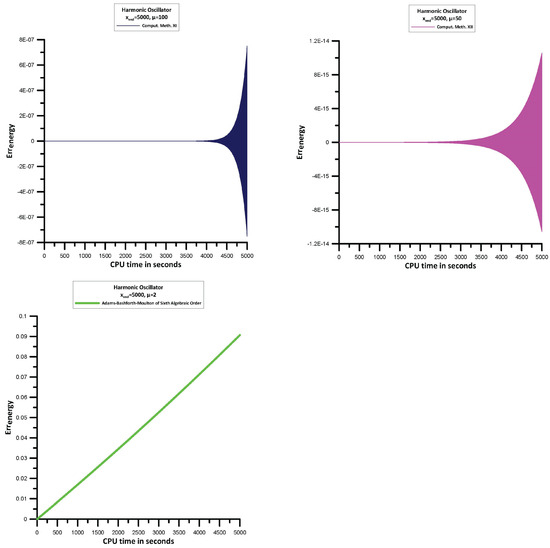

For the Comput. Meth. I, VII, VIII, IX, X, XIII, , while for the Comput. Meth. XI, , and for the Comput. Meth. XII, . This is because for , Comput. Meth. XI and Comput. Meth. XII are divergent.

The information in Figure 6 allows us to see the following:

- Comput. Meth. I, Comput. Meth. VIII, Comput. Meth. IX, Comput. Meth. X, Comput. Meth. XI, Comput. Meth. XII, and Comput. Meth. XIII behave like symplectic integrators.

- From the above methods Comput. Meth. X, and Comput. Meth. XIII are the most efficient ones.

- Comput. Meth. VII is not behave like symplectic integrator and is the less efficient one.

- For comparison purposes we present also the results for the Adams-Bashforth-Moulton sixth algebraic order method which is not behave like symplectic integrator.

Figure 6.

Maximum error in the Hamiltonian (171).

Figure 6.

Maximum error in the Hamiltonian (171).

13.7. High-Order Ordinary Differential Equations and Partial Differential Equations

Before trying to solve systems of high-order ordinary differential equations using the newly discovered techniques, remember that there are well-established procedures for reducing them to first-order differential equations. In this context, there are several methods that may be used, as stated by Boyce et al. [37], including modifying the variables, adding new variables, re-constructing the system with new variables for each derivative, and similar approaches.

Before discussing the recently implemented methods, it is important to note that there are existing approaches, such as the characteristics method (refer to [38]), that may be used to simplify a system of PDEs into a set of first-order differential equations.

13.8. Determination of the Parameter for Every Problem

The efficiency of newly created frequency-dependent algorithms is evaluated by determining the optimal value of the parameter . For a lot of issues, this option is laid out in the problem model. The parameter may be determined by using methods proposed in previous works for situations where this is challenging (see [39,40] for references).

14. Conclusions

We developed direct formulae for the computation of the phase lag and amplification factor of the Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae (ONCDF) based on the theory and methodologies for the proofs of the relevant formulae in our previous paper [25]. Our primary goal in carrying out this research was to find a technique that minimizes or vanishes the phase lag and amplification factor to ONCDF. After removing the phase-lag and amplification-factor derivatives, we also examined how the efficiency of the previously described techniques altered. In light of the above, we went on to describe many effective ways of developing procedures that make use of the phase lag and/or amplification factor and its derivatives. Specifically, we came up with the following approaches:

- Strategy for the vanishing of the amplification factor.

- Strategy for the vanishing of the amplification factor and minimization of the phase lag.

- Strategy for the vanishing of the phase lag and vanishing of the amplification factor.

- Strategy for the vanishing of the phase lag and vanishing of the amplification factor together with vanishing of the derivatives of the phase lag.

- Strategy for the vanishing of the phase lag and vanishing of the amplification factor together with vanishing of the derivatives of the amplification factor.

- Strategy for the vanishing of the phase lag and vanishing of the amplification factor together with the vanishing of the derivatives of the phase lag and the vanishing of the amplification factor.

The most efficient methods, according to our theoretical and numerical results, are those whose coefficients are defined with the requirement of vanishing the phase lag and the amplification factor, and with the requirement of vanishing the phase lag and the amplification factor, along with the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor.

Multiple Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae (ONCDF) were created by following the processes stated before. The foundation of our technique is the Open Newton–Cotes Differential Formulae (ONCDF) of sixth algebraic order.

To gauge their efficacy, the aforementioned methods were put to the test on a range of problems with oscillating solutions.

Here is a comment on the evolution of numerical approaches derived from the numerical results: A “symmetric way” is required for the vanishing of the derivatives of the phase lag and the amplification factor; that is, when a derivative of the phase lag has vanished, the corresponding derivative of the amplification factor must also vanish.

All calculations adhered to the IEEE Standard 754 and were executed on a personal computer featuring an x86–64 compatible architecture and utilizing a quadruple precision arithmetic data type consisting of 64 bits.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Direct Formulae for the Computation of the Derivatives of the Phase Lag and the Amplification Factor

Appendix A.1. Direct Formula for the Derivative of the Phase Lag

Appendix A.2. Direct Formula for the Derivative of the Amplification Factor

Appendix B. Formulae Pari, i = 5(1)7

Appendix C. Formulae Par18, Par19, Par20 and Par21

Appendix D. Formulae Parq, q = 18(1)20

Appendix E. Formulae Parp, p = 22(1)24

Appendix F. Formulae Parν, ν = 25(1)29

Appendix G. Formulae Parμ, μ = 30(1)33

Appendix H. Formulae Parυ, υ = 34(1)40

Appendix I. Formulae Parτ, τ = 41(1)45

Appendix J. Formulae Parφ, φ = 46(1)50

Appendix K. Formulae Parψ, ψ = 51(1)58

Appendix L. Formulae Park, k = 59, 60

References

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, F.M. Quantum Mechanics; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Rice, S. (Eds.) New Methods in Computational Quantum Mechanics. In Advances in Chemical Physics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; Volume 93. [Google Scholar]

- Simos, T.E. Numerical Solution of Ordinary Differential Equations with Periodical Solution. Doctoral Dissertation, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 1990. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Ixaru, L.G. Numerical Methods for Differential Equations and Applications; Reidel: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; Lancaster, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, G.D.; Tremaine, S. Symmetric multistep methods for the numerical integration of planetary orbits. Astron. J. 1990, 100, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyche, T. Chebyshevian multistep methods for ordinary differential equations. Numer. Math. 1972, 10, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konguetsof, A.; Simos, T.E. On the construction of Exponentially Fitted Methods for the Numerical Solution of the Schrödinger Equation. J. Comput. Meth. Sci. Eng. 2001, 1, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormand, J.R.; El-Mikkawy, M.E.A.; Prince, P.J. Families of Runge–Kutta-Nyström formulae. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 1987, 7, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.M.; Gomez, I. Some procedures for the construction of high-order exponentially fitted Runge–Kutta-Nyström Methods of explicit type. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013, 184, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.M.; Gomez, I. Accuracy and linear Stability of RKN Methods for solving second-order stiff problems. Appl. Numer. Math. 2009, 59, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.K.; Senu, N.; Ahmadian, A.; Ibrahim, S.N.I. Efficient Frequency-Dependent Coefficients of Explicit Improved Two-Derivative Runge–Kutta Type Methods for Solving Third- Order IVPs. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 843–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.J.; Fu, S.H.; Zhou, T.C.; Xiu, C. Exponentially fitted and trigonometrically fitted implicit RKN methods for solving y" = f (t, y). J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 68, 1449–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.L.; Yang, Y.P.; You, X. An explicit trigonometrically fitted Runge–Kutta method for stiff and oscillatory problems with two frequencies. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2020, 97, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormand, J.R.; Prince, P.J. A family of embedded Runge–Kutta formulae. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1980, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, M.M.; Rao, P.S. A Noumerov-Type Method with Minimal Phase-Lag for the Integration of 2nd Order Periodic Initial-Value Problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1984, 11, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ixaru, L.G.; Rizea, M. A Numerov-like scheme for the numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation in the deep continuum spectrum of energies. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1980, 19, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptis, A.D.; Allison, A.C. Exponential-fitting Methods for the numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1978, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Dai, Y.; Wu, D. An improved trigonometrically fitted P-stable Obrechkoff Method for periodic initial-value problems. Proc. R. Soc.-Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 461, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z. A P-stable eighteenth-order six-Step Method for periodic initial value problems. Int. J. Mod. Phys. 2007, 18, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Khalsaraei, M.M. A new family of explicit linear two-step singularly P-stable Obrechkoff methods for the numerical solution of second-order IVPs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 376, 125116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulganiy, R.I.; Ramos, H.; Okunuga, S.A.; Majid, Z.A. A trigonometrically fitted intra-step block Falkner method for the direct integration of second-order delay differential equations with oscillatory solutions. Afr. Mat. 2023, 34, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Senu, N.; Ahmadian, A.; Ibrahim, S.N.I. High-order exponentially fitted and trigonometrically fitted explicit two-derivative Runge–Kutta-type methods for solving third-order oscillatory problems. Math. Sci. 2022, 16, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.L.; Huang, T.; You, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, B. Two-frequency trigonometrically fitted and symmetric linear multi-step methods for second-order oscillators. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 392, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.; Neta, B. Trigonometrically Fitted Methods: A Review. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. A New Methodology for the Development of Efficient Multistep Methods for First-Order IVPs with Oscillating Solutions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. A New Methodology for the Development of Efficient Multistep Methods for First-Order IVPs with Oscillating Solutions IV: The Case of the Backward Differentiation Formulae. Axioms 2024, 13, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, H.; Kiyadeh, S.H.H.; Karim, R.G.; Safaie, A. Family of phase fitted 3-step second-order BDF methods for solving periodic and orbital quantum chemistry problems. J. Math. Chem. 2024, 62, 1223–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, H.; Kiyadeh, S.H.H.; Safaie, A.; Karim, R.G.; Khodadosti, F. A new amplification-fitting approach in Newton–Cotes rules to tackling the high-frequency IVPs. Appl. Numer. Math. 2025, 207, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhao, X.; Tang, Y. Numerical methods with a high order of accuracy applied in the quantum system. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 2275–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, E.; Bettis, D.G. Stabilization of Cowell’s Method. Numer. Math. 1969, 13, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehlberg, E. Classical Fifth-, Sixth-, Seventh-, and Eighth-Order Runge–Kutta Formulas with Stepsize Control; NASA Technical Report 287; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1968. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19680027281/downloads/19680027281.pdf (accessed on 10 December 1997).

- Cash, J.R.; Karp, A.H. A variable order Runge–Kutta method for initial value problems with rapidly varying right-hand sides. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1990, 16, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.M.; Palacios, M. High-order P-stable multistep methods. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1990, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, L.R. An efficient numerical method for highly oscillatory ordinary differential equations. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1981, 18, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. New Open Modified Newton Cotes Type Formulae as Multilayer Symplectic Integrators. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Gómez, I. Trigonometrically fitted nonuliear two-step methods for solving second order oscillatory IVPs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 232, 643–657. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, W.E.; DiPrima, R.C.; Meade, D.B. Elementary Differential Equations and Boundary Value Problems, 11th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L.C. Partial Differential Equations: Second Edition; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2010; Chapter 3; pp. 91–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, H.; Vigo-Aguiar, J. On the frequency choice in trigonometrically fitted methods. Appl. Math. Lett. 2010, 23, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ixaru, L.G.; Berghe, G.V.; Meyer, H.D. Frequency evaluation in exponential fitting multistep algorithms for ODEs. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2002, 140, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).