Abstract

The paper is devoted to the modeling of nonlinear viscoelastic materials. The constitutive equations are considered in differential form via relations between strain, stress, and their derivatives in the Lagrangian description. The thermodynamic consistency is established by using the Clausius–Duhem inequality through a procedure that involves two uncommon features. Firstly, the entropy production is regarded as a positive-valued constitutive function per se. This view implies that the inequality is in fact an equation. Secondly, this statement of the second law is investigated by using an algebraic representation formula, thus arriving at quite general results for rate terms that are usually overlooked in thermodynamic analyses. Starting from strain-rate or stress-rate equations, the corresponding finite equations are derived. It then emerges that a greater generality of the constitutive equations of the classical models, such as those of Boltzmann and Maxwell, are obtained as special cases.

Keywords:

viscoelastic materials; constitutive rate-type equations; nonlinear models; thermodynamic consistency MSC:

74D05; 74C99; 74F05

1. Introduction

Viscoelasticity involves a wide domain of models of materials. In general, viscoelasticity is a property ascribed to materials whenever the mechanical response changes in time while the forces causing the deformation are removed. Furthermore, the relation between forces and deformation may be different between the loading and unloading processes, thus producing hysteresis. Accordingly, viscoelastic models are thought to involve both viscous and elastic characteristics, which in turn might be affected by the temperature. This quite general view is realized by a number of mathematical models.

As is frequent in the literature, models of viscoelasticity are set up with reference to rheological elements, mainly the Maxwell unit and the Kelvin–Voigt unit; see, e.g., [1] and [2] (Ch. 6). This results in a combination of (possibly tensorial) values of deformation, stress, and their time derivatives.

From a mathematical standpoint, viscoelasticity is modeled in different ways. A well-known description traces back to Boltzmann [3], whereby the stress at time t is affected by the strain at all times . Furthermore, the stress–strain relation was assumed to be linear. Based on the Boltzmann model, much research has been undertaken for constitutive models in terms of memory functionals [4,5,6] in the wide domain of continuum physics and with attention to thermodynamic restrictions, initial and boundary-value problems, minimum principles, and wave propagation.

So as to obtain mathematically more tractable models, and meanwhile to allow for nonlinear effects, lately, different approaches have been developed. They are formally in differential form, and usually called rate-type viscoelastic models, in that they are expressed by relations between stress, strain, and their derivatives at the same time. This avoids the use of integral-type models for which the account of nonlinearities would be quite involved (see, e.g., [7]).

Physically admissible models are required to be thermodynamically consistent in the sense that the constitutive equations have to satisfy the inequality arising from the second law. While the inequality appears to place severe restrictions on the constitutive functions, a recent approach of ours enables greater generality. This occurs for two reasons. First, the entropy production is viewed as a constitutive function per se. Secondly, an appropriate exploitation of the inequality allows for possibilities that usually do not arise. There are approaches to (linear) viscoelastic models where continuum thermodynamics is not considered merely because the existence of internal energy is not assumed.

This paper develops a systematic approach to the modeling of viscoelastic materials through thermodynamically consistent schemes involving strain and stress in differential forms. Owing to the generality of the approach, we are able to recover known models from the literature and, furthermore, to find nonlinear models characterized by free energy and entropy production.

The postulate on the second law of thermodynamics leads to the CD (Clausius–Duhem) inequality, where the entropy production is provided by a constitutive function. The thermodynamic consistency is meant as the compatibility of a set of constitutive assumptions with the CD inequality. The methodology for the analysis of the consistency involves finding proper unknowns (here, stress-rate or strain-rate) through the direct application of a representation formula to the CD inequality.

Notation

The body occupies a time-dependent region in the three-dimensional space. The position vector of a point in is denoted by . For any pair of vectors or tensors , the notations and denote the inner product. Cartesian coordinates are used, and then, in the suffix notation, , , the summation over the repeated indices can be understood. For any tensor , and denote the symmetric and skew-symmetric parts of . Also, is the space of symmetric tensors.

2. Balance Laws and Constitutive Equations

Let be the region occupied by the body in a reference configuration. Any point in is associated with the position vector relative to the chosen origin. The motion of the body is a function . We let ∇ and denote the gradient in and . Hence, is the deformation gradient in components . Let and be the mass density and the velocity fields at at time . The symbol denotes the velocity gradient, , while and .

Hereafter, a superposed dot denotes the total time derivative. For any function on , we evaluate as . Accordingly, the balance of mass and the equation of motion are expressed by

where is the Cauchy stress tensor and is the specific body force.

We assume the existence of a specific internal energy density so that is the total energy density per unit volume. The balance of energy leads to

where r is the heat supply, per unit mass, and is the flux vector.

Let be the absolute temperature and the specific entropy density. Letting be the entropy flux, we assume the balance of entropy in the form

where is the (rate of) entropy production. We let and r be arbitrarily provided time-dependent fields on . Hence, we say that a process is the set , on , of the quantities entering the balance equations and the constitutive relations.

The statement of the balance of energy in the form (1) is essential for the next developments. It is worth observing that there are approaches in continuum mechanics where the existence of an energy density is not assumed. A distinction is made between stored and dissipated energy; the dissipated energy is determined by a rate equation involving appropriate state variables (see, e.g., [8] and Refs. therein). Still, without any assumption about the internal energy, attention is confined to a relation between stress and deformation through a transform function [9,10], the transform function being possibly expressed by fractional derivatives.

2.1. Second Law of Thermodynamics

The balance of entropy is assumed to be non-negative. Hence, the second law is stated as follows.

Postulate 1.

For every process admissible in a body, the inequality

is valid at any internal point.

Letting

we regard as the extra-entropy flux [11]. Nonzero values of arise when nonlocal properties (higher-order gradients) are considered. For the present purposes, there is no loss of generality in taking . Since

then substitution of from (1) and using the free energy results in

As is standard in continuum thermodynamics [11,12,13], the requirement (2), or (3), results in restrictions on physically admissible constitutive models. The novelty of the present approach is that, beyond the entropy flux , the entropy production is also conceptually a constitutive function to be determined. Henceforth, we apply the statement (2) to the modeling of viscoelastic materials.

While the extra-entropy flux is generally associated with nonlocal effects, models of materials are characterized by the free energy and the entropy production . Before addressing the restrictions placed by (3) and the intrinsic connections with and , we introduce useful terminology for viscoelastic models.

2.2. Lagrangian Form of the Balance Laws

Owing to the coexistent elastic and viscous properties, viscoelasticity is described by relations involving stress, strain, and their derivatives. The occurrence of time derivatives makes the compatibility with the objectivity principle more involved, whereby the constitutive equations must be form-invariant under the group of Euclidean transformations ([14] (Section 1.13); [2] (Section 1.9)). This requirement is best satisfied by dealing within the Lagrangian description. Hence, we represent deformation and stress by using the red-Lagrange strain, , and the second Piola tensor, ,

together with the referential vectors, e.g., . All of them and the Jacobian are in fact invariant. Under SO(3), the time derivatives are also invariant. Using the identities

we have

Consequently, multiplying (3) by J and recalling that is the mass density in the reference configuration, we obtain the CD inequality in the form

3. Rate-Type Models for Thermo-Viscoelastic Solids

To save writing the dependence on the temperature and possibly the temperature gradient , it is understood here and not written. Since we are dealing with viscoelastic models, we split into two additive parts, namely

with the view that is the elastic stress and the dissipative stress.

Rate-type equations involve relations, or constitutive equations, among variables , and . So, the variables are not independent from one another and are subject to appropriate conditions. Often, the relations are assumed in implicit form [15], namely

As a natural example, the CD inequality (4) might eventually result in the reduced form

where , are tensor functions. Depending on the function , this scheme allows us to obtain models of viscoelastic or viscoplastic materials with hysteresis [2] (ch. 13). To illustrate possible types of rate equations, we now show how particular cases arise from the implicit form (6).

- Assume . Hence, we can express in terms of the remaining variables . The corresponding functionwhere is a tensor-valued function, can be viewed as a constitutive function for , thus allowing models of dissipative stress–strain-rate materials.

- Now let be independent of so that the condition is . If further , we can solve with respect to and obtain a constitutive equation in the formIf, furthermore, with a fourth-rank tensor-valued function, using (5), we can writeEquation (8) is in a strain-rate form and can be viewed as a generalization of the Kelvin–Voigt model.

- The dual form of (7) is obtained by assuming that . Hence, we obtain a constitutive function for , namelywhere is a tensor-valued function. Equation (9) may be viewed as a strain–stress-rate model. If, in particular, is independent of , namely , then we can view as describing a conservative deformation, as is the case for elastic solids.

- If is independent of and , then we can derive the constitutive equationThis form may be referred to as a stress-rate model and is convenient whenever we examine the deformation determined by a time-dependent stress.

4. Stress–Strain-Rate Models

Based on the decomposition of , we look for models described by equations of the form

To allow also for heat conduction, we let

be the variables for the constitutive functions

A possible dependence on is embodied in the dependence on .

The CD inequality (4) can be written in the form

The quantities , and occur linearly and can take arbitrary values. Hence, (11) holds only if

We let

and hence (11) simplifies to

Further restrictions follow by considering (10) and in the particular form

It follows that , such that

where is independent of and is independent of .

4.1. Solutions to (12)

We now look for solutions to (12) in the unknown function subject to

that is, as .

First, we determine the general form of on the assumption that . In this connection, we recall a representation formula [2] such that if the (second order) tensor satisfies

then

being an arbitrary tensor. In Equation (14), denotes the fourth-order identity tensor and ⊗ the dyadic tensor product. Now let and define

while is allowed to be a function of , and . Hence, by (12), with and , we have

This is a general formula for the stress-rate . Appropriate choices for , and lead to special models of stress-rate equations.

4.1.1. A Model for Damage and Fatigue

A rather general model arises by letting

where in order that . These assumptions simplify Equation (15) to

The function is usually assumed to be positive, which allows

to be viewed as a relaxation time. To integrate Equation (16), we proceed as follows. Let

Hence, Equation (16) provides

and then the integration on yields

Accordingly, it follows that

Then, letting and assuming

we obtain

Finally, if we introduce the reduced-time function

where is named the time-temperature shift factor, Equation (18) can be rewritten as

Note that depends on the past values of , so that (19) is a non-separable integral representation of (see, e.g., [16]) that is able to capture damage and fatigue effects; we mention [17] where a representation of the form (19) is used to describe damage in asphalt mixture. The thermodynamic consistency of (19) is proved in the more general case of (15), which allows for nonlinearities through and and any dependence, on the whole set of variables, through .

4.1.2. The Maxwell Fluid

Assume that and depend on and let the temperature be a known function of time. Then, and are known functions of time in that

Hence, Equation (18) takes the form

Equation (20) is in the form of the Boltzmann model for in terms of the present value and the history .

If and , introduced in (17), are constants, then Equation (16) simplifies to

which is just the classical Maxwell equation although in the Lagrangian formulation. The solution can be obtained directly by integration. Otherwise, we observe that and would be constant and then Equation (20) would read

whence, by an integration by parts, it follows

Since , then can be written in the form

where

It reduces to the well-known linear model [4,5] if , .

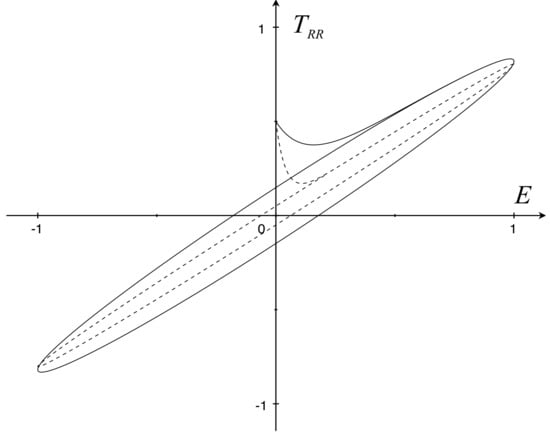

In the one-dimensional case, the differences between the linear and the nonlinear model are outlined by the following numerical simulations (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). In the first picture, we consider the linear one-dimensional model , where the evolution of is ruled by Equation (21). The resulting system

where describes the cycles in the plane at different frequencies of the oscillating strain.

Figure 1.

Stress–strain cycles at (solid) and (dashed) with , , and .

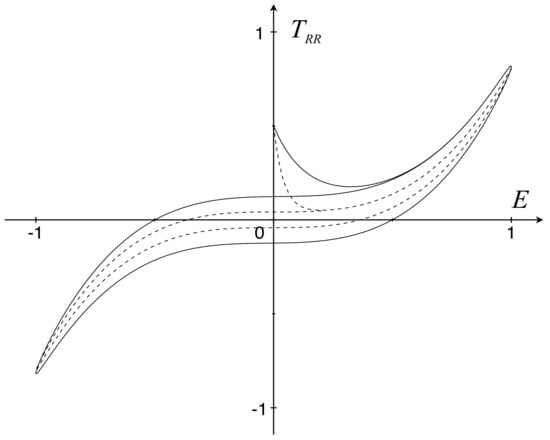

Figure 2.

Stress–straincycles at (solid) and (dashed) with , , and .

Figure 2 represents the cycles at different frequencies of the nonlinear model obtained by letting .

The resulting system

where describes the cycles in the plane at different frequencies of the oscillating strain.

It is of interest that Figure 1 and Figure 2 show a hysteretic evolution of the dependence . Systems (22) and (23) are rate-dependent, and this is made evident by the variation in the loop shape as the frequency changes. Indeed, as goes to 0 the loop narrows until it reaches the quasi-stationary regime . On the other hand, as the frequency increases, the loop becomes narrower and narrower, thus approaching the rate-independent property at high frequencies where . As a remark, the form of the loops associated with (23) is quite similar to the stress–strain curve occurring in foamed materials [2] (Section 13.7).

4.1.3. A Model for Bio-Soft Tissues

Consider one-dimensional settings and let , so too. Namely, materials with zero entropy production from the mechanical side are concerned. Furthermore, let depend on the strain E as well as on the temperature. Equation (16) then simplifies to

This type of rate equation is found to model the hypoelastic behavior of collagen fiber stress [18] if

for proper values of the positive parameters possibly dependent on . Assuming that these parameters are constant, upon integration, we obtain

where , .

In [18], the viscoelastic behavior of ligaments and tendons (bio-soft tissues) is determined by modeling collagen fibers and proteoglycan-rich matrix as a Maxwell-type system with two relaxation times, . By means of the following correspondence with our notations

the full model (Equation (15) in [18]) can be written in the form (see Equation (16))

where and

The positivity of for each value of E is guaranteed by the condition .

4.2. Solutions to (13)

Inequality (13) holds if is provided by a Fourier-like relation

with a positive definite second-order tensor; the dependence on the strain , in addition to the temperature , makes the model nonlinear. However, inequality (13) allows for more general solutions .

Letting , we apply the representation formula to (13). It follows that

where is any vector function of . If, e.g., we select , with positive definite, then Equation (26) becomes

Hence, consists of a part in the direction of and a part subject only to . This splitting is parameterized by the entropy production. Two interesting particular cases arise. Firstly, if , then the relation simplifies to Equation (25). Secondly, if , then

which is a Fourier-like relation with zero entropy production.

As a further example, let . Then, we have

This model shows that the deformation induces a transverse part of relative to ; the CD inequality is a constraint on the longitudinal part of while the transverse part is unconstrained.

5. Strain–Stress-Rate Models

We now consider a strain–stress-rate model in the explicit form

for definiteness, we select , rather than , as one of the variables. Accordingly, the set of variables is now

Again, we let and then consider the free energy

where is the elastic energy, say

Using instead of , we can write the CD inequality in the form

Computing the time derivative of and substituting, we have

The arbitrariness of , and implies that , , and . The remaining inequality is now examined by setting aside cross-coupling terms in the sense that is independent of and is independent of . Hence, the inequality (27) splits into

and again (13), where is the value of at .

We now apply the representation Formula (14) to Equation (28). Assume and define . Hence, by Equation (28), we obtain

where is a tensor function of . Equation (29) shows the general form of the function in terms of .

The simplest case follows by letting and (zero entropy production). Hence, we have

The integration of (30) on and the assumption yield

An integration by parts and the assumption result in

These results have some analogy with a class of quasi-linear viscoelastic materials [19] where the present value of is provided by the history of .

6. Strain-Rate Models

As a generalization of the Kelvin–Voigt constitutive equation, we now look for a function

Hence, we let

be the variables and the constitutive functions. The CD inequality becomes

The arbitrariness of implies that

The remaining inequality is

Although and might depend jointly on , for definiteness, we assume that

while is independent of . Hence, inequality (31) splits into two inequalities, namely

and again (13), where is the value of at and is the value of at . In light of (32), it follows from (33) that

6.1. Some Examples

Borrowing from [20], we now consider a model with application to human knee ligaments. Let and be functions satisfying the requirements in (34). Let

Hence, and are assigned the forms

where the parameters are allowed to depend on temperature. Furthermore, p is the standard pressure of the Eulerian description.

A nonlinear model is obtained by using the triples and of the main invariants of and , respectively. The requirement (34) is satisfied by letting

where and . In a more detailed form, we can assume

Otherwise, we might consider the representation

whence it follows that

In this case, the non-negative value of requires appropriate restrictions on .

Another class of unidimensional nonlinear strain-rate models has been proposed to describe the mechanical behavior of polymeric foams whose dynamic loading shows a dependence of the stress also on the strain-rate [2] (ch. 13.7). To include strain-rate effects, the dependence has been improved in the form [21]

where may depend on the temperature . The literature shows various forms of the functions , e.g.,

where are the pertinent positive parameters and is a reference strain-rate (frequently ).

6.2. Generalizations of the Kelvin–Voigt Model

A two-parameter class of constitutive equations is considered in [15] in the form

this equation is said to model a fluid if and an elastic solid if . For generality, we might regard strain-rate models as those characterized by relations in the Lagrangian form,

where . As we show in a while, significantly different relations arise depending on the choice of the (independent) variables.

For definiteness, here, we let be the variables. The exploitation of the CD inequality leads to

and the remaining inequality is (33). Assuming (34)1, we have

Since depends on , we look for as a function of the same variables, namely

(see the special case of item 3). We let and apply the representation Formula (14) to obtain

where is a tensor function of the variables . In particular, if we take , then it follows

A model describing a conservative strain evolution is obtained by assuming zero entropy production, . If , we can write Equation (37) in the form

Inasmuch as , we obtain the Kelvin–Voigt equation as an approximation of (37).

A more general constitutive equation in the form

is thermodynamically consistent. This is shown by substituting

in (36). It follows that

The right-hand side is the expected function , where , and are involved in a proper way. This is a nonlinear generalization of the Kelvin–Voigt type. However, if , then a model is obtained with zero entropy production.

If is a known function of time, then we can integrate (38) to obtain

which is again in the Boltzmann form with dependence on the histories of , and .

If instead we let be the variables, then, applying the representation formula to (34)2, it follows that

In the simple case

we have

6.3. Remarks about Alternative Strain-Rate Models

Within the strain-limiting elastic constitutive setting [22,23], the strain and the strain-rate are replaced by their linear approximations and . In this setting,

so that, if and are comparable, then we can take the approximation

Hence, assuming and , we recover the model investigated in [22].

7. Stress-Rate Models

Many experimental tests may be viewed as the investigation of the strain induced by a stress process. This warrants attention regarding stress-rate models, as is the case in [25,26]. Hence, we now address equations of the form

To examine the compatibility of the constitutive function (42) with the second law, we let

be the set of variables. Consistently, it is convenient to consider the Gibbs free energy

and observe that

Now, are provided by constitutive equations. Computation of and substitution in the CD inequality yield

The arbitrariness of implies that

and

For reasonable simplicity, we let be independent of . Hence, we let

both and being non-negative. Thus, it follows that

For definiteness, we consider (44) under the assumption

It follows that

and

A nonlinear dependence of on and can be assumed in the form

where and

8. Advantages and Disadvantages of Rate Equations

The constitutive equations of viscoelastic materials in the form of rate equations are advantageous in many respects. Relative to the Lagrangian description adopted in this paper, the dissipative properties of solids are modeled by equations involving the rates , most frequently through nonlinear dependencies on and . Nonlinear properties are then accounted for in a variety of ways, thus showing the flexibility of the approach. Furthermore, the thermodynamic consistency is established in a standard way by using the representation formula also in view of the constitutive property of the entropy production.

The nonlinearities possibly involved in the rate equations need not allow us to set the equations in the form of materials with fading memory. This shows the limited possibility of modeling through memory integrals, although increasing attention is focused on models with fractional derivatives [27,28,29].

It is worth mentioning that, so far, aging properties are described by memory functionals. In this connection, consider a four-rank tensor function on and, in the Eulerian description, we modify the Boltzmann model of viscoelastic behavior in the form

where and is the infinitesimal strain tensor. The function accounts for the memory through the second variable, s, and for aging through the first variable, t. This approach is developed in [30]. The aging effect on the viscoelastic property is also described by a memory integral through a rescaling of times [17,31], as illustrated above by Equation (19).

9. Conclusions

The modeling of viscoelastic or dissipative solids is often developed through memory functionals. The description through the Boltzmann functional for the stress in terms of the strain history is the best-known example in this sense. Yet, memory functionals make it more involved than any account of nonlinearity and affect compatibility with thermodynamics. That is why, alternatively, the thermodynamically consistent modeling of viscoelasticity is performed through rate-type equations whose best-known examples are those associated with rheological models.

This paper provides a general account of viscoelasticity through rate equations as relations between strain, stress, and their derivatives. To comply with the objectivity principle, we chose to follow the Lagrangian description and used as variables the Green–Lagrange strain and the second Piola stress , or and . Both and are invariant under Euclidean transformations and hence so are their time derivatives . The inspection of thermodynamic consistency leads to the analysis of inequalities like, e.g., . Equations (15), (29) and (38) describe general classes of viscoelastic models in rate-type form.

Two features, characteristic of this paper, are unusual in the literature. Firstly, the entropy production is regarded as provided by a constitutive function to be determined or chosen. Secondly, the use of a representation formula enables vector (or tensor) unknowns to comprise an arbitrary term, denoted by . Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 show that special selections of lead to qualitatively new constitutive equations. Furthermore, the constitutive rate equations thus determined have the remarkable advantage of being consistent with thermodynamics. The main outcome of this paper is that a simple, unique scheme, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics, leads to nonlinear models of various real materials (see Section 4.1, Section 6.1 and Section 6.3).

Although this has not been our concern here, it is worth mentioning that the same thermodynamic approach to equations involving and enables the modeling of hysteresis in viscoplastic materials, as shown, e.g., in [6]. Regarding possibilities for future work developments, we observe that modeling through rate equations is under investigation in connection with the transition processes.

Author Contributions

Investigation, conceptualization, writing, editing: A.M. and C.G. All authors have contributed substantially and equally to the work reported. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to this work has been developed under the auspices of Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica-Gruppo Nazionale di Fisica Matematica.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gutierrez-Lemini, D. Engineering Viscoelasticity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morro, A.; Giorgi, C. Mathematical Modelling of Continuum Physics; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Boltzmann, L. Zur Theorie der elastichen Nachwirkung. Sizber. Kaiserl. Akad. Wiss. Wien. Math.-Naturw. Kl. 1874, 70, 275–300. [Google Scholar]

- Leitman, M.J.; Fisher, G.M.C. The linear theory of viscoelasticity. In Encyclopedia of Physics; Truesdell, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1973; Volume VIa/3. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, M.; Morro, A. Mathematical Problems in Linear Viscoelasticity; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, C.; Morro, A. Materials with memory: Viscoelasticity and hysteresis. In 50+ Years of AIMETA. A Journey through Theoretical and Applied Mechanics in Italy; Rega, G., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 243–260. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, C.; Golden, M. Viscoelastic and electromagnetic materials with non-linear memory. Materials 2022, 15, 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanj, A.; He, F.; Breedveld, P.C. Energy-biased viscoelastic model: A physical approach for material anelastic behavior by the bond graph approach. Simulation 2020, 96, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Nagahama, H. Physically meaningful parameters of viscoelastic models based on the general functional form of the transfer functions. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Yao, D.; Xu, W. A new method for formulating linear viscoelastic models. Int. J. Engng. Sci. 2020, 156, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, I. Thermodynamics; Pitman: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Truesdell, C. Rational Thermodynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtin, M.E.; Fried, E.; Anand, L. The Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Continua; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eringen, A.C.; Suhubi, E.S. Elastodynamics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal, K.R. On implicit constitutive theories. Appl. Math. 2003, 48, 279–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, Y.C. Stress strain history relations of soft tissues in simple elongation. In Biomechanics, Its Foundations and Objectives; Fung, Y.C., Perrone, N., Anliker, M., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Schapery, R.A. On the characterization of nonlinear viscoelastic materials. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1969, 9, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Yun, G.; Narsu, B. A mathematical model for viscoelastic properties of biological soft tissues. Theory Biosci. 2022, 141, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliana, A.; Rajagopal, K.R.; Wineman, A.S. A new class of quasi-linear models for describing the nonlinear viscoelastic response of materials. Acta Mech. 2013, 224, 2169–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioletti, D.P.; Rakotomanana, L.R.; Benvenuti, J.-F.; Letvraz, P.-F. Viscoelastic constitutive law in large deformations: Application to human knee ligaments and tendons. J. Biomech. 1998, 31, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Ko, W.L.; Lindholm, U.S. Mechanical behavior of foamed materials under dynamic compression. J. Cell. Plast. 1974, 10, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, K.R.; Saccomandi, G. Circularly polarized wave propagation in a class of bodies defined by a new class of implicit constitutive relations. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2014, 65, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, Y. Viscoelasticity with limiting strain. Discr. Cont. Dyn. Syst. Ser. S 2021, 14, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, A.; Vanderby, R., Jr.; Lakes, R.S. Interrelation of creep and relaxation for nonlinearly viscoelastic materials: Application to ligament and metal. Rheol. Acta 2003, 42, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, H.A.; Şengül, Y. A thermodynamically-consistent stress rate type model of one-dimensional strain-limiting viscoelasticity. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2020, 71, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, E.; Şengül, Y. Stress-rate-type strain-limiting models for solids resulting from implicit constitutive theory. Adv. Cont. Discr. Mod. 2023, 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, M.; Giorgi, C.; Morro, A. Modelling of heat conduction via fractional derivatives. Heat Mass Transfer 2017, 53, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Generalized Memory: Fractional Calculus Approach. Fractal Fract. 2018, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandibur, O.; Garrappa, R.; Kaslik, E. Stability of Systems of Fractional-Order Differential Equations with Caputo Derivatives. Mathematics 2021, 9, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, M.; Giorgi, C.; Morro, A. Two approaches to aging and fatigue models in viscoelastic solids. Atti Accad. Peloritana Pericolanti 2019, 97, A7. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, T.; Kehrer, L.; Hirschberg, V.; Wilhelm, M.; Böhlke, T. Nonlinear Schapery viscoelastic material model for thermoplastic polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 52028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).