Abstract

The abundance of publicly available data on the internet within the e-marketing domain is consistently expanding. A significant portion of this data revolve around consumers’ perceptions and opinions regarding the goods or services of organizations, making it valuable for market intelligence collectors in marketing, customer relationship management, and customer retention. Sentiment analysis serves as a tool for examining customer sentiment, marketing initiatives, and product appraisals. This valuable information can inform decisions related to future product and service development, marketing campaigns, and customer service enhancements. In social media, predicting ratings is commonly employed to anticipate product ratings based on user reviews. Our study provides an extensive benchmark comparison of different deep learning models, including convolutional neural networks (CNN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), and bi-directional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM). These models are evaluated using various word embedding techniques, such as bi-directional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) and its derivatives, FastText, and Word2Vec. The evaluation encompasses two setups: 5-class versus 3-class. This paper focuses on sentiment analysis using neural network-based models for consumer sentiment prediction by evaluating and contrasting their performance indicators on a dataset of reviews of different products from customers of an online women’s clothes retailer.

Keywords:

artificial intelligence; sentiment analysis/rating; natural language processing; deep learning; transformers; product reviews MSC:

68T50

1. Introduction

Currently, the internet is the finest way for any business to find out what the general public thinks of its goods and services. Many buyers will make a decision about a product after reading a few reviews. Reviews are generated on a daily basis, and managing and analyzing such a large volume of data can be challenging. The surge in online shopping has been particularly pronounced, especially during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, prompting numerous countries to impose stay at home orders. With so many physical retail outlets closing and worries about COVID-19 spreading, online shopping has taken over as the primary way that customers make their purchases. Soliciting customer feedback through textual reviews and ratings has become a common practice among online retailers [1,2]. These reviews, abundant on online platforms and social media, play a crucial role in shaping customer purchasing decisions and offering valuable insights to sellers. Sentiment analysis provides a quick and easy way to categorize reviews, which provides merchants and customers with insightful information about what customers are saying about products and services [3,4].

Sentiment analysis typically involves determining the sentiment bias (positive, neutral, or negative) of textual information. This helps improve decision-making processes in a variety of areas, including finance and stock markets, digital payment services [3], retail, and products, among others. Scientists studying sentiment analysis based on text communication also often attempt to determine sentiment ratings using a 1–5 or 10-point scale, with higher scores indicating more positive feedback. There are indications that there are many machine learning algorithms that are often used for sentiment analysis, but deep learning has become more popular in recent years and has shown promising results. Additionally, researchers have explored various word embedding approaches, including popular approaches such as Word2Vec and advanced transformer-based pre-trained models such as bi-directional encoder representations from transformers (BERT). These advanced models have demonstrated higher performance in text classification. However, as discussed in Section 2.2, there is a significant gap in research on deep learning algorithms, especially those that investigate and compare alternative embedding strategies. This gap exists in both English and non-English datasets. Moreover, a recent review shows that there is a lack of research on data augmentation strategies in supervised deep learning systems to improve prediction accuracy [4]. This technique is commonly used as a regularization technique to synthesize new data from existing data and is widely used in image processing, but its application to text data establishes standard rules for automation. This is limited to some exceptions as it is difficult to do so. Conversion of text data maintains the quality of annotations.

When consumers need to decide whether to buy a product or service, they are confronted with a profusion of user reviews, making the effort of reading and analyzing them all time-consuming. Similarly, firms who want to collect public input, sell their products, identify new prospects, forecast sales patterns, or maintain their reputation have the issue of dealing with a large number of accumulated consumer reviews. Sentiment analysis technologies provide a solution by allowing for the examination of large amounts of data and the extraction of consumer sentiment. This analysis helps both customers and companies achieve their objectives [4]. Sentiment analysis is a branch of computer science that focuses on processing text to extract opinion data, evaluating people’s viewpoints as transmitted through written language.

Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining or emotion AI, is a natural language processing (NLP) technique that determines whether input is positive, neutral, or negative [5]. This approach is often used in conjunction with text data for companies to monitor brand and product insights derived from customer feedback and gain insights into consumer preferences. The main difficulty for e-commerce companies is understanding consumer preferences, including which products they are likely to recommend.

The proposed study aims to address the following research question: How can advanced deep learning models and transformer-based techniques be effectively utilized to improve sentiment analysis for predicting product reviews in e-commerce recommendation systems?

The study specifically targets sentiment analysis within the e-commerce sector, examining consumer reviews to predict product ratings. This focus aims to enhance the understanding of accurately capturing and utilizing consumer sentiment for recommendation systems. The research provides a detailed benchmark comparison of various deep learning models, including CNN, RNN, and Bi-LSTM, using different word embedding techniques like FastText, Word2Vec, and BERT and its derivatives. Additionally, it compares different machine learning models such as Naïve Bayes, Support Vector Machine, Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, and Random Forest. This benchmarking is crucial for identifying the most effective models for sentiment analysis in the e-commerce context.

The proposed study surpasses the current state-of-the-art in several ways:

Advanced Embedding Techniques: While previous studies have utilized traditional word embeddings, this study incorporates the latest transformer-based models like BERT, which have demonstrated superior performance in various NLP tasks. The inclusion of BERT and its derivatives signifies a substantial advancement in embedding techniques for sentiment analysis.

Comprehensive Model Comparison: Unlike prior research that often concentrates on a single model or a limited set of models, this study offers a comprehensive comparison of multiple deep learning models, providing a broader perspective on their relative performance and applicability.

Practical Application Focus: The research not only assesses models in isolation but also explores their integration into practical recommendation systems, delivering valuable insights for e-commerce platforms aiming to implement these advanced techniques.

2. Background and Related Work

Sentiment analysis holds immense significance across various sectors like business, government, and education. Particularly noteworthy is the considerable research directed towards integrating sentiment analysis into recommender systems. This section initiates with furnishing background details and scrutinizing the existing literature to offer a contemporary outlook on the integration of sentiment analysis within recommender systems.

2.1. Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis employs natural language processing (NLP), rule-based techniques, and machine learning algorithms to automatically discern emotional tones. Sentiment analysis extraction operates at three levels: sentence level, document level, and aspect or feature level. Information pertaining to the subject is gathered, and all pertinent subjective elements are automatically identified. The objective is to ascertain whether the user-provided content expresses positive, neutral, or negative sentiments.

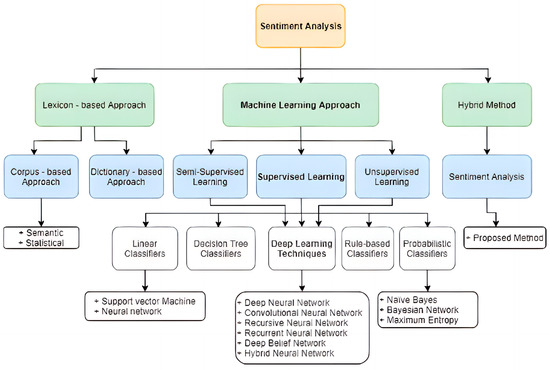

Currently, sentiment analysis employs three methods [6]: hybrid, machine learning, and lexicon-based approaches. Dictionary-based and corpus-based techniques fall under the category of dictionary-based methods [7], which were among the initial approaches used in sentiment classification. Both traditional and deep learning approaches are encompassed in machine learning-based strategies [8] recommended for sentiment analysis. Hybrid approaches [9] combine lexicon-based techniques and machine learning, often incorporating sentiment lexicons significantly. Figure 1 depicts a taxonomy of sentiment analysis methods based on deep learning.

Figure 1.

Taxonomy of sentiment analysis methods [9].

Sentiment analysis can be categorized into various forms depending on the nature and extent of the analysis. Here are several typical types:

- Binary Sentiment Analysis: Positive/negative sentiment. Binary sentiment analysis divides text into positive or negative groups. This approach is used in tasks such as assessing sentiment in product reviews, where the goal is to evaluate whether the expressed attitude is good or negative.

- Ternary Sentiment Analysis: Sentiment: positive, negative, neutral. This style of literature is divided into three different categories: positive, negative, and neutral. This is useful when a more nuanced attitude is required or when a large number of texts express a neutral opinion.

- Multi-Class Sentiment Analysis: Includes multiple sentiment categories. Unlike the three-category approach, multi-class sentiment analysis divides text into several sentiment categories. Sentiment can be categorized as very positive, positive, neutral, negative, or very negative. This strategy allows for a more extensive and sophisticated study of sentiment.

While sentiment analysis is a useful method for understanding public opinion, it faces various obstacles and complexities:

- Ambiguity and situation: Language is inherently ambiguous, and the same words or phrases can have different meanings depending on the situation. Sentences such as “I’m dying of laughter” or “This movie is wicked” provide difficulties in interpretation without context.

- Sarcasm and Irony: Detecting sarcasm, irony, and other forms of figurative language is a significant challenge for sentiment analysis models. This issue arises because the sentiment expressed frequently contradicts the actual meaning of the words.

- Negation: Negations can drastically change the sentiment of a statement. For example, “not bad” is positive while “not good” is negative. Understanding the influence of negations is critical for conducting proper sentiment analysis.

- Emoticons and emojis: Individuals often utilize emojis and emoticons to convey emotions, and these symbols can pose challenges for models to accurately interpret.

- Slang and Informal Language: Sentiment analysis methods may struggle with slang, informal language, and expressions unique to a certain community or subculture. These expressions may not be present in the training data.

Sentiment analysis is also called opinion mining, and provides various advantages and finds applications across diverse domains:

Business and Market Intelligence:

- Product Feedback: sentiment analysis may help organizations collect client feedback via reviews, social media, and polls, providing insights into how their products or services are regarded.

- Competitor Analysis: companies can use sentiment analysis to examine the sentiment surrounding their competitors, identifying their strengths and flaws.

Market Research:

By analyzing sentiment in market discussions, firms can gain useful insights into market trends and client preferences.

Customer Support and Engagement:

- Real-time Feedback: sentiment analysis technologies can actively monitor social media and customer service channels to detect and handle client issues and sentiments.

- Chatbots: integrating sentiment analysis into chatbots allows them to better understand and respond to client emotions and wants.

Brand Reputation Management:

- Crisis Management: brands can use sentiment analysis to detect and address possible PR disasters on social media and news channels.

- Brand Monitoring: this tool helps firms track how their brand is perceived over time and across locations.

Product Development:

- Feature Prioritization: analyzing consumer sentiment allows organizations to prioritize product innovations and upgrades based on customer value.

- Innovation: sentiment analysis helps to discover developing trends and client requests, which can provide significant assistance for innovation efforts.

Financial Services:

- Stock Market Prediction: sentiment analysis of news items and social media discussions can anticipate stock market trends.

- Risk Management: analyzing sentiment in financial reports and news helps to estimate market sentiment and risk.

2.2. Recommendation Systems

A recommender system is largely used to evaluate consumers’ interests, habits, and preferences while selecting a certain product or service. This information comes from a variety of sources, including the user’s buying history [8]. These data are then used to estimate if the user would purchase the same product or a comparable product variety in the future. Filtering technology is used to improve the algorithm in this regard [9]. When a product is purchased, it is given a ranking, and data are processed by analyzing the ranked products and the user list [9]. Some algorithms assign weights to products, and then select the highest-ranked or most-weighted products from the list to recommend to the consumer.

Recommendation systems were developed to address the issue of information overload in a variety of fields, including e-commerce, entertainment, and content platforms. Users frequently demand assistance accessing large catalogs of products, movies, music, articles, and other content. The goal is to help people discover relevant and tailored items or material based on their choices, interests, and previous behavior. Recommendation systems have the capability to generate personalized suggestions by analyzing individual user preferences through data such as browsing history, purchase history, reviews, and interactions.

Recommender systems strive to provide tailored recommendations for products or services, enriching decision-making in the expansive landscape of internet information. Across three fundamental domains—business, government, and education—a plethora of systems has emerged, encompassing eight categories: e-government, e-business, e-commerce/e-shopping, e-library, e-learning, e-tourism, e-resource services, and e-group activities [10]. Particularly in e-commerce, these systems often propose additional products for customers to explore from a vast array, with filtering methods enhancing the presentation of personalized options [10]. The most prevalent techniques for recommender systems can be classified into three categories: content-based, collaborative filtering (CF), and hybrid systems [10]. The application of these strategies varies depending on the type of social media data utilized.

In the realm of machine learning and natural language processing (NLP), various types of recommendation systems are commonly employed. Here are some key types:

- Content-Based Filtering: This technique suggests products based on the user’s past choices or actions. To generate recommendations, it assesses an object’s qualities or attributes and contrasts them with the user’s profile or past. A movie recommendation system might, for instance, make recommendations for similar movies based on the plot, performers, or genre.

- Collaborative Filtering: Products are suggested according to the preferences and actions of other users who have similar tastes. It finds patterns and similarities in user behavior, like ratings and purchases, and suggests products that people with similar interests have found enjoyable. This approach is based more on user behavior than item features.

- Hybrid Approaches: To increase suggestion accuracy, hybrid recommendation systems include a number of methods. In addition to conventional machine learning algorithms, these systems might employ collaborative and content-based filtering techniques to offer more detailed and varied recommendations.

- Matrix factorization: This is a technique that breaks down user-item interaction matrices to uncover latent components or attributes. Examples include singular value decomposition (SVD) and alternating least squares (ALS). By capturing underlying trends, these systems may forecast missing ratings and then recommend things.

- Deep Learning-Based Methods: Neural networks and other deep learning models can be applied to enhance the performance of recommendation systems. These models can produce more precise recommendations by incorporating complex patterns and representations from huge datasets. For recommendation tasks, methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are employed.

- Techniques Based on Natural Language Processing (NLP): Recommendation systems have the capability to utilize natural language processing (NLP) techniques such as sentiment analysis, text classification, or topic modeling to extract insights from textual inputs. Algorithms based on NLP, which can interpret user reviews, feedback, or product descriptions, can subsequently offer recommendations based on sentiment analysis or linguistic resemblance.

2.3. Related Work

In recent times, several opinion mining and sentiment analysis studies of reviews have been conducted. In order to provide more context, Ref. [11] used 91.9% accuracy in RNN-based Word2Vec embedding for sentiment analysis on reviews taken from the Indonesian Traveloka website. With accuracy scores of 85.8%, 80.5%, and 90.6%, respectively, Hameed and Garcia-Zapirain [12] used Bi-LSTM to assess three datasets: Movie Review, ImDB, and Stanford Sentiment Treebank (SST2). They came to the conclusion that Bi-LSTM showed promise for sentiment analysis tasks and was computationally efficient. Similar to this, Xu and associates [13] used a similar strategy to extract sentiments from Chinese hotel reviews by combining Word2Vec with Bi-LSTM, LSTM, RNN, and CNN. Bi-LSTM was the best-performing model, achieving an F-score of 92%. On the other hand, Ref. [11] used Word2Vec and term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) to examine CNN, RNN, and deep neural networks (DNN) over 13 different datasets. According to their research, using Word2Vec improved model performance in every statistic. Furthermore, the most efficient model was found to be RNN with Word2Vec, despite requiring more processing power than the other models.

Several research teams [10,11,13] have proposed methods for combining sentiment analysis into recommender systems. SVM, CNN, RNN, and DNN are all methods that can be used for sentiment analysis. The literature also includes studies that improve sentiment analysis in reviews by using sophisticated embedding techniques like BERT and its variants. For example, Ref. [12] improved sentiment analysis for product reviews utilizing BERT CNN and found that, in terms of F-score outcomes, BERT-CNN (84.3%) performed better than individual BERT (82%) and CNN (70.9%) alone. In a similar vein, Ref. [13] presented SenBERT-CNN, a BERT and CNN integration tool for assessing reviews from mobile phone shop JD.com. CNN was used to extract complex textual elements. The results showed that, with a rate of 95.7%, BERT-CNN outperformed LSTM, BERT, and CNN in terms of accuracy. In a different study [13], neural network (NN) models were used to predict drug ratings that included reviews with a scale of 0 to 10 that represented patients’ satisfaction levels. The authors investigated two scenarios using different NN models, including BERT-LSTM. The results showed that, despite a noticeably longer training period, BERT-LSTM functioned optimally in the 3-class format, producing an average F-score of 82.37%. Additional research demonstrates the higher accuracy of BERT by examining several NN models using BERT for a movie review dataset [11]. Additionally, Ref. [13] used BERT to analyze sentiment on Twitter, turning informal language into formal text in order to train BERT.

This study will use unique feature extraction methods and deep learning algorithms for sentiment analysis, using BERT’s strengths. The purpose is to include sentiments into recommendation algorithms as supplemental feedback, improving the effectiveness and reliability of recommender systems.

3. Proposed Methodology

The e-commerce business has grown in popularity, removing the necessity for physical order taking from individual clients. Companies create online platforms to directly offer products to end users, allowing customers to easily place orders through the website. Amazon, Flipkart, Myntra, Paytm, and Snapdeal are some of the most well-known e-commerce behemoths.

In today’s fast changing technology landscape, any company joining the e-commerce sector must quickly grow and establish itself as a vital player. This is especially important given the rivalry from established market giants such as Amazon and Flipkart. Leading organizations, such as Amazon, use numerous recommendation algorithms to provide individualized ideas to customers. For example, item–item collaborative filtering is used, resulting in high-quality real-time recommendations. This system functions as an information filtering tool, attempting to predict user preferences and ratings.

This project aims to improve the Amazon customer experience by using customer input to generate personalized suggestions. The technology learns about users’ preferences by analyzing reviews, which helps them choose products that are matched to their tastes. The goal is to reimagine how customers explore and engage with Amazon’s vast product offering by combining machine learning and natural language processing.

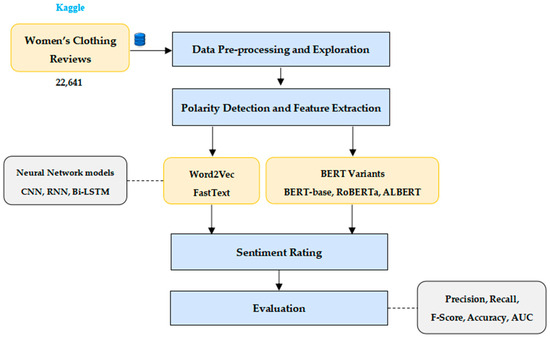

The goal of the project’s sentiment analysis is to identify whether or not a product is recommended. Several machine learning algorithms have been used to improve prediction accuracy. Logistic regression, support vector machine (SVM), naive Bayes, Ada Boosting, CatBoost, random forest, and XGBoost are examples of conventional machine learning methods used in categorization. In addition, deep learning techniques including the BERT algorithm have been implemented. The dataset used is from Woman Clothing Reviews, which is available on Kaggle. The steps used to analyze the data are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overall proposed methodology.

3.1. Dataset Description

The dataset consists of 22,641 rows and 10 column variables, with each row including a written comment and extra customer information. Each row is a customer review and includes the following variables of feature information:

- Clothing ID: An integer category variable that designates the precise item under examination.

- Age: The age of the reviewer is represented as a positive integer variable.

- Title: A string variable containing the review’s title.

- Review Text: A text variable containing the review’s body.

- Rating: A positive ordinal integer variable, with a range of 1 (worst) to 5 (best), that indicates the client’s product score.

- Recommended IND: A binary variable that indicates if the customer recommends the product (1 = recommended, 0 = not recommended).

- Number of Positive Comments: A positive number signifying how many other consumers thought this review was good.

- Division Name: A categorical name that represents the product’s highest-level division.

- Department Name: A classification name designating the department of products.

- Class Name: Identifies the product class.

3.2. Data Pre-Processing and Exploration

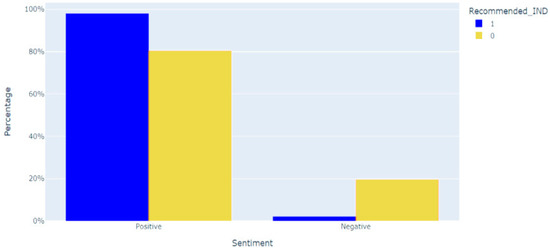

Canonicalization, a process that involves converting text to lowercase, stripping leading and trailing spaces, digits, punctuation, and stop words (common English words lacking significant contextual information such as ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’, etc.), was employed in typical natural language processing tasks. Following this, tokenization, which divides sentences into individual words, and lemmatization, which reduces words to their base forms, were applied. To ensure consistent matrix dimensions, index encoding and zero padding were implemented using the Keras 2.7.1 package. The distribution of the target variable “Recommend_IND” indicated an imbalanced dataset, with a substantial majority of consumers recommending purchased products (over 80%). Additionally, a new variable called “Text_Length,” representing the length of each remark, was introduced, and its relationship with the target variable was explored. Moreover, the correlation between the target variable and the “Rating” variable was illustrated. Pre-processing tasks were conducted using commonly used Python 3.7 libraries such as NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit) and RE (Regular Expression) [13].

3.3. Polarity Detection and Feature Extraction

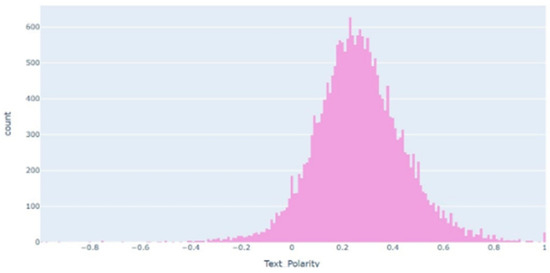

Following data pre-processing, the filtered review texts, summaries, and adjectives extracted from the reviews are used to determine the polarity of the reviews. The Python module TextBlob [14] makes it easier to anticipate sentiment polarities. Polarity is a floating value that lies in the interval [−1, 1] where 1 signifies positive feedbacks and −1 a negative one [15]. The distribution of the polarity score in the customers’ reviews is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Where the majority of the comments are situated on the positive side of the graph [0, 1]. Table 1 depicts the textual reviews and polarity determined by TextBlob.

Figure 3.

Percentage of sentiments in relation to the target variable bar plot.

Figure 4.

Reviews text polarity bar plot.

Table 1.

Polarity and sentiment dataset for textual reviews.

Features are quantifiable properties or dimensions that are processed by algorithms; feature extraction is the process of converting processed texts into formats that are instructive. The prediction models used in sentiment analysis are generally the foundation of feature extraction techniques. Word embedding vector representations of particular words were used as extracted features in this investigation, using a variety of techniques:

- Word2Vec: a trained model that creates an embedded vector for every word in a text by identifying word associations in a corpus.

- FastText: a Word2Vec plugin that breaks down words into n-grams, or smaller units, like “application” into “app,” with the goal of teaching word morphology. Every word in the text is converted by the model into a bag of embedded vectors.

Polysemous words might provide difficulties when using Word2Vec and FastText since they always assign the same embedding vector, regardless of context. Researchers have been using transformer-based embeddings, such as BERT and its derivatives, to address this problem. Word contexts from BooksCorpus and Wikipedia were used to pre-train models like BERT, and the resulting embeddings were then used in classifiers to make predictions. These models have demonstrated state of the art performance in natural language processing tasks by providing contextualized word embeddings.

The bidirectional transformer used in the BERT-based model has been pre-trained on large amounts of unlabeled textual data to provide a language representation that can be tailored to different classification tasks. One noteworthy variation is RoBERTa, which Facebook unveiled. It is an improved version of BERT with increased processing power and expanded prediction capabilities that can handle larger amounts of data. Furthermore, ALBERT, a condensed and effective BERT variant that is far smaller than BERT, was created by Google and Toyota. In particular, two variants of a BERT-based model, RoBERTa and ALBERT, were studied in this work.

3.4. Description of the Models Used for Sentiment Analysis

3.4.1. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

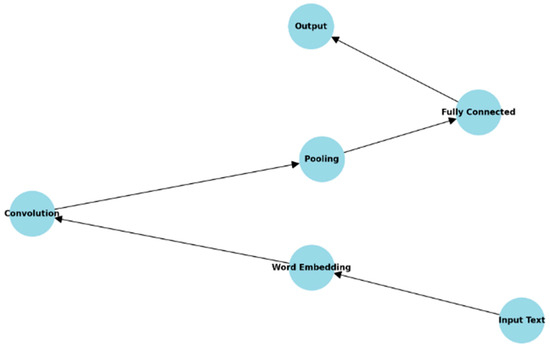

CNNs capture local dependencies in the text, making them effective for identifying specific phrases or word combinations that indicate sentiment. Figure 5 presents the CNN architecture.

Figure 5.

CNN architecture.

- Architecture:

Input Layer: Takes in the word embeddings of the text.

Convolutional Layers: Apply filters to capture local dependencies in the text.

Pooling Layers: Reduce dimensionality and retain important features.

Fully Connected Layers: Classify the sentiment based on the extracted features.

3.4.2. Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

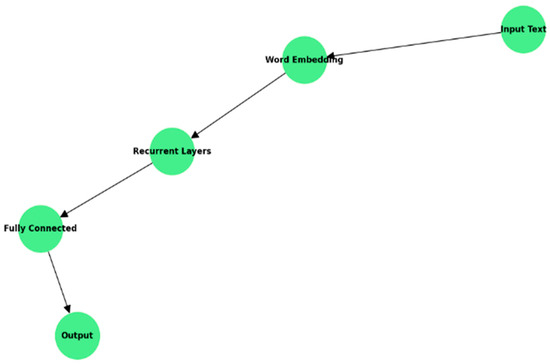

RNNs are designed to handle sequential data by maintaining a hidden state that captures information from previous time steps. This is particularly useful for sentiment analysis as it considers the order of words in a sentence. Figure 6 presents the RNN architecture.

Figure 6.

RNN architecture.

- Architecture:

Input Layer: Takes in the word embeddings.

Recurrent Layers: Process the text sequentially, updating the hidden state at each step.

Fully Connected Layers: Use the final hidden state to classify the sentiment classification.

3.4.3. Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM)

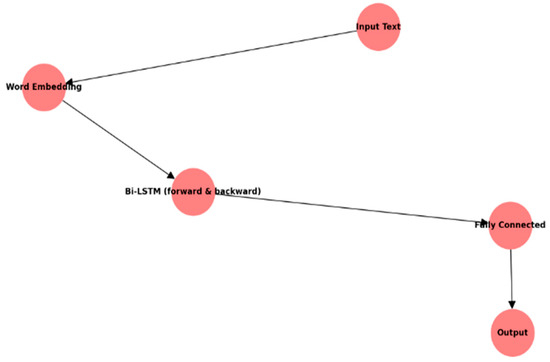

Bi-LSTM networks are an extension of RNNs that can capture dependencies from both past and future contexts by processing the sequence in both directions. Figure 7 presents the Bi-LSTM architecture.

Figure 7.

Bi-LSTM architecture.

- Architecture:

Input Layer: Takes in the word embeddings.

Bi-LSTM Layers: Process the text in both forward and backward directions.

Fully Connected Layers: Use the concatenated hidden states to classify the sentiment.

3.4.4. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

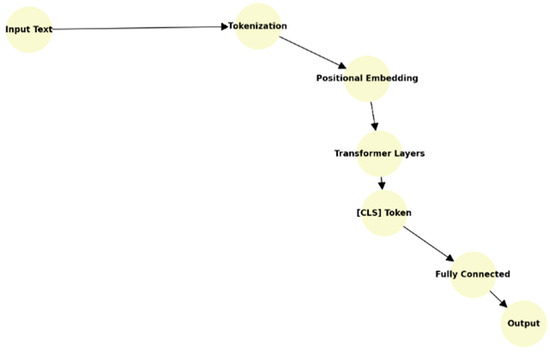

BERT is a transformer-based model that uses self-attention mechanisms to capture contextual relationships between words in a sentence. It processes the entire text simultaneously rather than sequentially, which allows it to capture long-range dependencies. Figure 8 presents the BERT architecture.

Figure 8.

BERT architecture.

- Architecture:

Input Layer: Takes in tokenized text along with positional embeddings.

Transformer Layers: Use self-attention to capture contextual information.

Output Layer: The final hidden state of the (CLS) token is used for classification.

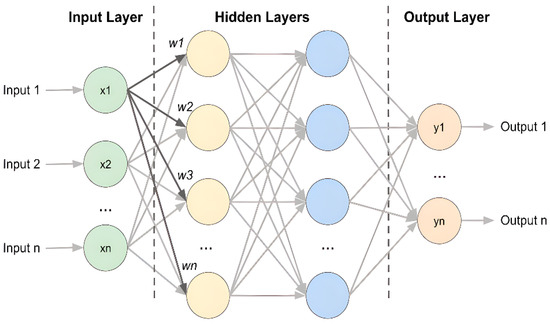

3.5. Sentiment Analysis Review Predictions with Deep Learning Models

The academic literature outlines three prominent neural network (NN) algorithms: convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) networks. These NN architectures consist of artificial neurons organized in layers, including input (predictors), output (predictions), and hidden layers. In a feed-forward multilayer NN model (illustrated in Figure 9), each layer receives input from previous layers, integrating them through adaptive weights adjusted during training [15]. Each neuron is assigned an activation function, with common choices including tangent sigmoid, logarithmic sigmoid, and Softmax functions [15].

Figure 9.

Weibull distribution of all filler concentrations.

RNN is a type of NN particularly skilled at modeling and predicting sequence data. It addresses long-term dependencies among words in a text corpus and utilizes word-based vectors. By leveraging its internal memory, RNN processes sequential data, enabling the network to retain information from previous processing stages [16]. For this study, an LSTM layer with 256 units, a 0.3 dropout rate, and a 0.001 learning rate were employed. Softmax was utilized as the activation function, transforming a vector of values into a probability distribution.

Contrary to common belief, convolution, pooling, and fully connected layers constitute the three fundamental layers utilized by CNNs to capture spatial hierarchies of information. The fully connected layer consolidates the features extracted from the preceding two layers to produce the final output. As these features become more complex in a hierarchical manner, algorithms can be employed to enhance their configurations. In our approach, we employed window sizes of 3, 4, and 5 words for the vectors, alongside a linear rectification unit (ReLU) as the activation function, to construct a convolution layer comprising 256 filters. Furthermore, a kernel regularizes with a dropout rate of 0.3 and an L1 regularization penalty of 0.01 were included.

In contrast, the Bi-LSTM represents an advancement over traditional RNNs, capable of processing textual input while preserving the semantic context preceding and following it. This is achieved through the utilization of recurrently connected memory blocks and bidirectional LSTM units, each equipped with three gates: an output gate regulating memory cell output, a forget gate determining the duration of information retention in memory, and an input gate managing information entry [17]. For the Bi-LSTM model, we incorporated two distinct types of dense layers: one comprising 64 units with ReLU as the activation function, and another encompassing 3 and 5 classes with Softmax as the activation function. Additionally, the BiLSTM model underwent constant drop out regularization at a rate of 0.3.

3.6. Machine Learning Models

It is vital to keep in mind that, in order to assess classical machine learning algorithms’ performance in comparison to deep learning models, we also carried out additional evaluations. In particular, we chose the support vector machine (SVM), naive Bayes, random forest, logistic regression, and decision tree—five well-known machine learning algorithms that are frequently used in sentiment analysis research.

A popular probabilistic technique for classification tasks, naive Bayes requires little training data and is widely used. The probability derived from the class with the maximum posterior is provided [18,19]. SVM, on the other hand, is well-known for its efficacy with high-dimensional datasets and seeks to determine the ideal hyperplane for classification, even though it takes a long time to locate the ideal kernel functions [20].

The decision tree is a powerful classification technique that uses ‘if–then’ rule-based structures to describe links between attributes and targets in a tree structure [21]. Compared to other machine learning methods, it can handle big datasets with relative ease; nonetheless, it may have instability problems, as small variations in training samples can lead to considerable variations in classification outcomes [22]. The random forest algorithm, which is well known for its classification accuracy without experiencing overfitting issues, is an improvement over the decision tree. The random forest algorithm produces several distinct trees and then aggregates the decisions made by each of these separate trees to arrive at a final forecast [23]. Finally, the boosting strategy enhances classification performance by combining weak classifiers. Research indicates that this method performs better than other machine learning algorithms, including SVM and decision tree [24].

3.7. Evaluation

All of the models were evaluated using the common performance metrics for classification issues, which are as follows:

Precision: this metric calculates the ratio of true positive outcomes to the total positive predictions made by the model (true positives and false positives) (Equation (1)).

Recall: this measures the percentage of true positive instances correctly identified by the model (Equation (2) [25]).

F-score: The F-score represents the harmonic mean of recall and precision, with values ranging from 0 to 1. A higher F-score indicates better model performance. The formula to calculate the F-score is as follows (Equation (3)):

Accuracy: this metric evaluates the ratio of correct predictions to the total number of cases examined, as depicted in Equation (4), where FN denotes false negatives, FP represents false positives, TN signifies true negatives, and TP indicates true positives [26].

AUC-ROC (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve): The AUC-ROC score signifies the area beneath the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve [27]. Similar to the F1-score, the AUC ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating superior performance [28]. The ROC curve visually represents the relationship between sensitivity (true positive rate) and 1-specificity (false positive rate) [29].

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

The experiments conducted to evaluate the suitability of the suggested sentiment analysis method for forecasting product evaluations within the framework of e-commerce recommendations are described in this part. Two well-known datasets were used in this process. The results of these tests are shown and explained in the section that follows.

4.1. Experiment

The following scenarios and configurations were used during the experiments:

Based on the labeling, there were two different experiment setups:

- 3-class: Combining ratings 1 and 2 indicated negative sentiment, 3 indicated neutral emotion, and combining ratings 4 and 5 indicated positive sentiment [30].

- 5-class: This corresponds to the original rating system, which consisted of five categories: 1 denoting extremely negative, 2 representing negative, 3 indicating neutral, 4 signifying positive, and 5 denoting extremely positive [31].

The experiment scenarios encompass the following:

- Utilization of RNN, CNN, and Bi-LSTM models with Word2Vec and FastText embeddings on the dataset.

- Assessment of BERT variants (including BERT, RoBERTa, and ALBERT) in both 5-class and 3-class configurations.

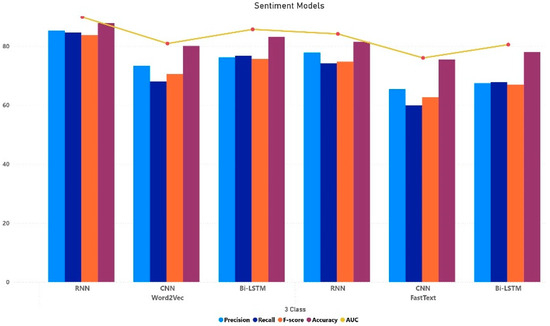

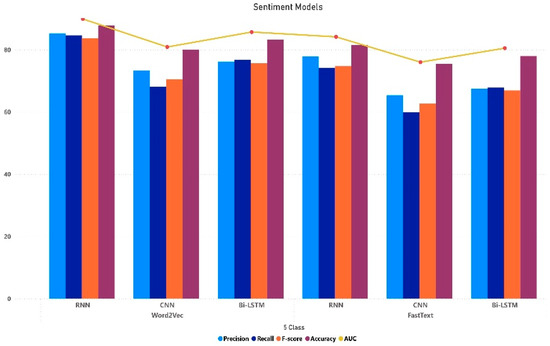

4.2. Neural Network-Based Models Using Word2Vec and FastText Embeddings

The results of all the neural network models’ trials using Word2Vec and FastText methods with the dataset in 5- and 3-class configurations are shown in Table 2 and Figure 10 and Figure 11. This was carried out in order to assess how well the various neural network models performed in relation to the two-word embedding methods and class configurations.

Table 2.

Performance of neural network models as percentages (%) on the dataset: Word2Vec versus FastText.

Figure 10.

Sentiment performance of NN models using Word2Vec and FastText in 3-class scenario.

Figure 11.

Sentiment performance of NN models using Word2Vec ans FastText in 5-class scenario.

Overall, regardless of arrangement, it is clear that Bi-LSTM based on Word2Vec consistently performed better than other neural network models, with RNN coming in close second. Using Word2Vec for both settings, the dataset results showed a continuous pattern where RNN was shown to be the better model. This is consistent with findings from other studies [32,33] that found the best model for sentiment classification was an RNN utilizing Word2Vec.

This stands in contrast to the findings of [34], which declared CNN-Word2Vec to be the best model. Research utilizing RNNs has generally found that word embedding methods yield more accurate prediction models than other methods like TF-IDF [35].

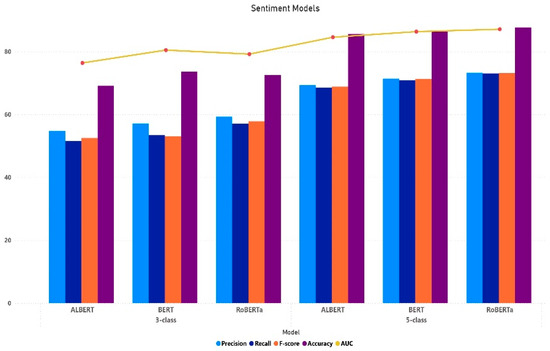

4.3. BERT Variants for Sentiment Review Prediction

The performance results for the BERT variations are shown in Table 3 and Figure 12, which shows a pattern that consistently favors RoBERTa in our dataset and configurations. In addition, it is evident that the 3-class design exhibits better prediction performance than the 5-class setup. This pattern is consistent with the findings from the neural network models (Table 2), maybe as a result of more accurate categorization when working with fewer classes/categories. Similar results were seen in [35], where the authors observed that their 3-class arrangement had a higher F-score than their 10-class setup.

Table 3.

Performance of BERT models as percentages (%) on the dataset: 5-class versus 3-class setups.

Figure 12.

Sentiment performance of BERT models.

In our dataset, the performance of BERT variants was comparable to that of neural network models, although their metric scores were slightly lower. Among the three variants, RoBERTa exhibited the best results, albeit only marginally better than BERT’s. This observation is consistent with a prior study [36], which indicated that RoBERTa outperformed BERT across various natural language processing tasks, achieving performance improvements of up to 20%. However, another study [37] found that BERT outperformed RoBERTa in a sentiment analysis task. The authors of that study attributed this discrepancy to differences in the quality of data and features utilized in their analysis [38].

Following the findings of Section 4.2, RNN-Word2Vec was identified as the optimal model using the 3-class setup and an augmented dataset [39]. Consequently, all subsequent experiments were conducted using Word2Vec and the 3-class setup on our dataset.

4.4. Ensemble Neural Network Models for Sentiment Rating Prediction

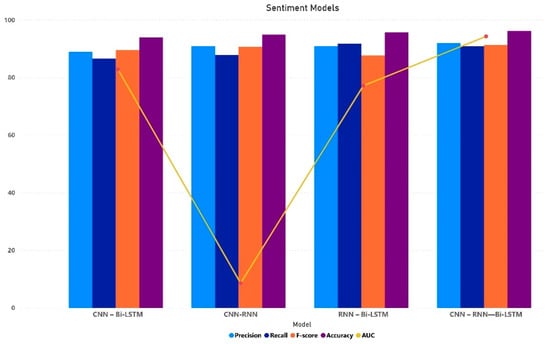

The findings for ensemble models employing Word2Vec and the optimal dataset configuration—specifically, the 3-class setting—are presented in Table 4 and Figure 13. The objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of the individual neural network models reported in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 against the ensemble models in terms of sentiment review prediction, without modifying any citations, references, or inline citations.

Table 4.

Performance of ensemble models as percentages (%) on the dataset.

Figure 13.

Sentiment performance of ensemble models.

According to the information provided in Table 2, our study demonstrates that all ensemble models exhibit superior performance compared to their individual neural network counterparts. Specifically, the CNN-RNN-Bi-LSTM model achieved the highest accuracy rate of 96.2%, along with an F-score of 91.3%. It is worth noting that this trend aligns with previous research findings, which have consistently shown that multimodal techniques tend to outperform individual models, regardless of the datasets used [40,41].

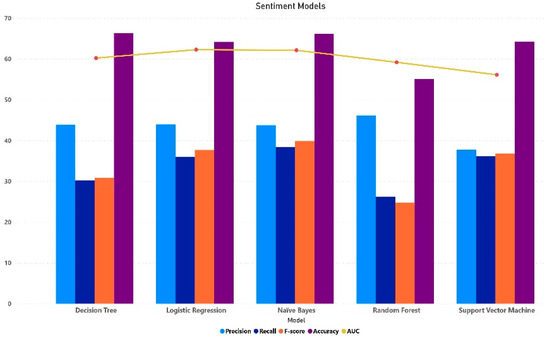

4.5. Machine Learning Models for Sentiment Prediction

Lastly, we applied the same configuration as in Section 4.3 with multiple machine learning models, as indicated in Table 5 and Figure 14, to test our findings against the machine learning approach. Compared to the deep learning models, all the models showed at least a 22% difference in accuracy outcomes, indicating poor performance.

Table 5.

Performance for the machine learning models in percentage (%).

Figure 14.

Sentiment performance of machine learning models.

The study indicates that, in comparison to the traditional machine learning approach, the more robust deep learning models are more appropriate for performing sentiment rating predictions based on these findings.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Our research contributes to the field of online customer review analysis by employing multiple deep learning algorithms and various embedding strategies [41]. Our findings indicate that all prediction models exhibit improved performance when utilizing fewer, more precisely calibrated classes, as demonstrated by the results of our 3-class versus 5-class comparison. Additionally, we discovered that while Word2Vec outperformed FastText in the context of context-free embeddings, the differences between the two were not significant. Notably, RoBERTa achieved the most promising outcomes, surpassing both BERT and ALBERT [42]. Our study also highlights the benefits of ensemble models over solo models. The results of our research were generated using only American English, adhering to its spelling, specific terms, and phrases.

This study has several limitations that are worth noting. For one, the accuracy of the predictions could have been affected by the fact that the dataset used was not thoroughly screened for spam or fraudulent reviews [43]. Therefore, it may be necessary to include an extra step in the pre-processing stage that involves the automated detection of spam and fraudulent reviews. Additionally, the study’s focus is limited to English reviews, which restricts the applicability of the proposed models and conclusions in multilingual settings. This limitation is significant since internet users come from diverse linguistic backgrounds and frequently communicate in languages other than English, such as Chinese, Spanish, and others [43].

We experimented using popular neural network models and other embedding strategies, such as the more sophisticated BERT and its variations. On the other hand, other strategies might be investigated, including lexicon integration, which can be paired with neural network and BERT-variant models, like lexicon-enhanced BERT and lexicon-RNN. It is also important to note that the percentage of polysemous words in BERT was not taken into consideration in this study, despite the fact that this is a factor that has been examined in many other research projects [44]. According to these studies, representations generated from BERT may capture a word’s degree of polysemy and sense partition ability. It would be interesting to investigate this further in the future by accounting for the percentage of polysemous words for BERT variations.

Therefore, future research endeavors may investigate optimization strategies or investigate substitute ensemble boosting methodologies in order to augment the predictive capabilities of models [45]. Additionally, anticipating review ratings based on real-time data and apps may be a compelling and important direction, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic’s substantial impact on the worldwide buying environment and the spike in popularity of online shopping.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B.; methodology, O.B.; software, O.B.; validation, A.B. and M.B.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, M.B.; resources, O.B.; data curation, O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.; writing—review and editing, O.B.; visualization, O.B.; supervision, M.B.; project administration, O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in our study is sourced from the Women’s Clothing E-Commerce Reviews dataset available on Kaggle, data and codes sources: https://github.com/oumaima-bl/Sentiment-Analysis-Predicting-Product-Reviews-for-E-commerce-Recommendation-using-Deep-Learning.git (accessed on 23 June 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Liu, D.; Bian, Y. Customer preferences extraction for air purifiers based on fine-grained sentiment analysis of online reviews. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 228, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, Y. Constructing a semantic graph with depression symptoms extraction from twitter. In Proceedings of the 16th IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Siena Tuscany, Italy, 9–11 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, N.R.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Mondal, M.R.H.; Islam, M. Bangla text sentiment analysis using supervised machine learning with extended lexicon dictionary. Nat. Lang. Process. Res. 2021, 1, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Chang, S.T. Exploring customer sentiment regarding online retail services: A topicbased approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Pan, Z.; Xia, R. E-commerce product review sentiment classification based on a Naïve Bayes continuous learning framework. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.I.; Ahmed, K.; Karim, R. Word Cloud and Sentiment Analysis of Amazon Earphones Reviews with R Programming Language. Inform. Econ. 2020, 24, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.; Lok, P.Y.; Rahim, H.A. A semi-supervised approach in detecting sentiment and emotion based on digital payment reviews. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 3795–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Sherratt, R.S. Sentiment analysis for E commerce product reviews in Chinese based on sentiment lexicon and deep learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 23522–23530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosia, A.E.; Coelho, G.P.; Silva, A.E. Investment strategies applied to the Brazilian stock market: A methodology based on sentiment analysis with deep learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 184, 115470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zad, S.; Heidari, M.; Jones, J.H.; Uzuner, O. A survey on concept level sentiment analysis techniques of textual data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 May 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 0285–0291. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, N.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H. A hybrid model integrating deep learning with investor sentiment analysis for stock price prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 178, 115019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikhosrokiani, P.; Pourya Asl, M. (Eds.) Handbook of Research on Opinion Mining and Text Analytics on Literary Works and Social Media; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Zhan, J. Sentiment analysis using product review data. J. Big Data 2015, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, P. Feature specific sentiment analysis for product reviews. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Text Processing and Computational Linguistics, New Delhi, India, 11–17 March 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 475–487. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Jha, C.K.; Sharan, A.; Vaish, V. Sentiment analysis of financial news using unsupervised approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 167, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Han, R.; Tse, M.; Ali, M.H.; Hu, J. A social media analytic framework for improving operations and service management: A study of the retail pharmacy industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taparia, A.; Bagla, T. Sentiment analysis: Predicting product reviews’ ratings using online customer reviews. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Fung, J.S.; Murtaza, M.; Rahman, A.; Walia, P.; Obande, D.; Verma, A.R. A sentiment analysis of the Black Lives Matter movement using Twitter. STEM Fellowsh. J. 2022, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colón-Ruiz, C.; Segura-Bedmar, I. Comparing deep learning architectures for sentiment analysis on drug reviews. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 110, 103539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munikar, M.; Shakya, S.; Shrestha, A. Fine-grained sentiment classification using BERT. In Proceedings of the 2019 Artificial Intelligence for Transforming Business and Society (AITB), Kathmandu, Nepal, 5 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Shi, Z.; Dong, Z.; Pang, C.; Zhang, B. Sentiment analysis of online product reviews based on SenBERT-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics (ICMLC), Adelaide, Australia, 2–15 July 2020; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pota, M.; Ventura, M.; Catelli, R.; Esposito, M. An effective BERT-based pipeline for twitter sentiment analysis: A case study in ITALIAN. Sensors 2021, 21, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qurat, T.A.; Mubashir, A.; Amna, R.; Amna, N.; Muhammad, K.; Babar, H.; Rehman, A. Sentiment Analysis Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Furht, B. Text data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, Z.; Lina, Y.; Aixin, S. Deep Learning based Recommender System: A Survey and New Perspectives. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2017, 52, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S. Contextual augmentation: Data augmentation bywords with paradigmatic relations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; Volume 2, pp. 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.T.; Nguyen-Thi, T.A. A review: Preprocessing techniques and data augmentation for sentiment analysis. Comput. Soc. Netw. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, M.E.; Bouri, E.; Azoury, N. The determinants of the U.S. consumer sentiment: Linear and nonlinear models. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.R.; Pandey, M.; Rautaray, S. Topic-level sentiment analysis of social media data using deep learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 108, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjali, M.; Kasri, M.; Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 226, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, T.U.; Saber, N.N.; Shah, F.M. Sentiment analysis on large scale Amazon product reviews. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Innovative Research and Development (ICIRD), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–12 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.; Lee, L.; Vaithyanathan, S. Thumbs up? Sentiment classification using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the ACL-02 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing-Volume 10, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–7 July 2002; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, W.; Balakrishnan, V. Improving sentiment scoring mechanism: A case study on airline services. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 1578–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, N.; Seo, H.; Song, M. Developing a supervised learning-based social media business sentiment index. J. Supercomput. 2019, 76, 3882–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabha, M.I.; Srikanth, G.U. Survey of Sentiment Analysis Using Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Innovations in Information and Communication Technology (ICIICT), Chennai, India, 25–26 April 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandhula, T.; Pabboju, S.; Gugalotu, N. Predicting the customer’s opinion on amazon products using selective memory architecture-based convolutional neural network. J. Supercomput. 2019, 76, 5923–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabet, S.; Tedmori, S.; Al-Smadi, M. Enhancing Arabic aspect-based sentiment analysis using deep learning models. Comput. Speech Lang. 2021, 69, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupa, K.; Ayutthaya, T.S. Thai sentiment analysis with deep learning techniques: A comparative study based on word embedding POS-tag, sentic features. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasari, L.; Setyanto, A. Sentiment analysis using recurrent neural network. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1471, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. Sentiment classification using a single-layered BiLSTM model. IEEE Access 2021, 8, 73992–74001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, X.; Yu, Z.; Wu, X. Sentiment analysis of comment texts based on BiLSTM. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 51522–51532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellar, O.; Baina, A.; Bellafkih, M. Application of Machine Learning to Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision (AICV2023), Marrakesh, Morocco, 5–7 March 2023; Hassanien, A.E., Haqiq, A., Azar, A.T., Santosh, K.C., Jabbar, M.A., Słowik, A., Subashini, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellar, O.; Baina, A.; Bellafkih, M. Sentiment Analysis of Tweets on Social Issues Using Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Digital Age & Technological Advances for Sustainable Development (ICDATA), Casablanca, Morocco, 3–5 May 2023; pp. 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumaima, B.; Amine, B.; Mostafa, B. Deep Learning or Traditional Methods for Sentiment Analysis: A Review. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7. SCA 2023; Ben Ahmed, M., Boudhir, A.A., El Meouche, R., Karaș, İ.R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).