Abstract

The pervasiveness of offensive language on social media emphasizes the necessity of automated systems for identifying and categorizing content. To ensure a more secure online environment and improve communication, effective identification and categorization of this content is essential. However, existing research encounters challenges such as limited datasets and biased model performance, hindering progress in this domain. To address these challenges, this research presents a comprehensive framework that simplifies the utilization of support vector machines (SVM), random forest (RF) and artificial neural networks (ANN). The proposed methodology yields notable gains in offensive language detection, automatic categorization of offensiveness, and offense target identification tasks by utilizing the Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID). The simulation results indicate that SVM performs exceptionally well, exhibiting excellent accuracy scores (77%, 88%, and 68%), precision scores (76%, 87%, and 67%), F1 scores (57%, 88%, and 68%), and recall rates (45%, 88%, and 68%), proving to be practically successful in identifying and moderating offensive content on social media. By applying sophisticated preprocessing and meticulous hyperparameter tuning, our model outperforms some earlier research in detecting and categorizing offensive language tasks.

Keywords:

machine learning; offensive language detection; offensive language categorization; offensive target identification; SVM; random forest; ANN; OLID MSC:

68T50; 68U15

1. Introduction

The pervasiveness of offensive language on social media sites (62.6% users of the world’s population [1]) such as Twitter [2], Facebook [3], and Instagram [4] presents severe obstacles in online communication. In an effort to promote safer online environments, governments and social media companies are actively looking for robust automated solutions to identify and remove hate speech and offensive content. With advancements in machine learning and linguistic analysis, offensive language detection has a bright future ahead of it. The goal is to increase the efficiency and accuracy of identifying different types of offensive language. Training systems to identify offensive content so that it can be eliminated or categorized for human review is one of the most popular approaches.

However, the dynamic nature of language [5], the volume of content [6,7], and the ethical issues around bias and censorship [8] make it more difficult to identify offensive language on social media. Because offensive content is so widespread, it is fundamentally difficult to identify and classify it, necessitating the urgent need for innovative technological solutions. Furthermore, in this engineering dilemma, poorly written text, faint paralinguistic hints, and the unrestrained spread of hate speech provide formidable challenges to automated detection methods.

As a result of study into the issue of offensive language detection on social media, much cutting-edge research has emerged to handle this complex problem. Such research can be broadly categorized into a number of groups according to the methodologies and objectives. A subset of studies concentrates on the application of deep learning architectures, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and ensemble classifiers. These models have demonstrated exceptional effectiveness in detecting offensive language with respect to recall rates and precision. The use of capsule networks with emoji information by Ranasinghe et al. [9] and the ensemble classifier of the recurrent neural network (RNN) model approach by Georgios et al. [10] are a couple instances of advancements in utilizing sophisticated neural network structures for enhanced detection accuracy. A different subset of research addresses advancements in datasets to address challenges including class imbalance and dataset scarcity. Zampieri et al. in [11,12], for instance, established the Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID) and SOLID dataset to facilitate in fine-grained annotation and larger-scale training for offensive language identification. Notably, despite the great contributions they bring to the field, these efforts are constrained by factors such as possible annotation noise and dataset representation. Conversely, Huang et al. [13] investigated the unique challenges related to detecting offensive language in Dravidian languages by utilizing a combination of Tf-Idf algorithms, CNN blocks, and multilingual BERT models. Although their work emphasizes the need for customized methods for diverse linguistic contexts, it stumbles into issues with code-mixing and sophisticated dataset preprocessing. Furthermore, Georgios et al.’s study [10] highlights how effectively RNN model ensemble classifiers recognize offensive words, such as racism and sexism; however, it falls short of offering a comprehensive examination of dataset biases and scalability issues. Similar to this, Abarna et al. [14] introduce a unique approach for detecting cyber harassment using Word2vec (word2vec 0.11.1), FastText (fasttext 0.9.2), and Bi-LSTM (TensorFlow 2.8.0) models.Although it exhibits more efficiently, it has limitations with dataset imbalance and scalability. Each of these papers highlights both the ongoing challenges and advancements in the field of offensive language detection, while also offering distinctive insights into the broader discourse. The challenge of identifying hate speech on social media is a complex one that requires holistic solutions. While recent studies, such as the study by Kovács et al. [15], have made progress in improving the efficiency of hate speech detection by incorporating external resources and sophisticated neural network architectures, important areas such as bias handling, conventional definitions of hate speech, and sophisticated text processing techniques are still not well studied. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of offensive language detection research, where the state of the art is always being advanced by developments in machine learning methods and dataset curation.

In this study, we investigate different approaches to the problem of offensive type and targeted post detection on social media to address cyberbullying or cyber-aggression. In order to detect and categorize offensive language on social media posts, our proposed solution leverages machine learning algorithms, especially support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF) and deep learning (ANN). With the utilization of the Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID) and by implementing three distinct subtasks, our goal is to identify and categorize offensive content accurately on tweet posts/messages. Our approach involves extensive data preprocessing, including text normalization and feature extraction using TF-IDF vectorization, to transform raw social media data into a format suitable for machine learning models. We employ SVM, RF, and ANN algorithms, optimizing hyperparameters to enhance model performance in offensive language detection.

The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive approach to offensive language detection and targets, addressing multiple subtasks (offensive language detection, automatic categorization of offensiveness, and offense target identification) using machine learning techniques. We achieve robust and scalable offensive content classification by integrating advanced preprocessing and optimization techniques. The main contributions of this research are outlined as follows:

- By utilizing different text processing techniques, machine learning, and deep learning algorithms, we detected offensive social media content and the content’s target.

- We applied data preprocessing techniques, including text normalization, word tokenization, word lemmatization, and mathematical vectorization of words utilizing TF-IDF, to raw social media data. These techniques significantly improve the model’s performance in offensive language detection and classification.

- The research conducts a comprehensive simulation study and mathematical analysis comparing machine learning models, notably support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF) and artificial neural network (ANN), using the OLID dataset, with SVM demonstrating superior performance across multiple offensive language detection subtasks on social media, achieving higher accuracy scores, F1 scores, and recall rates for offensive language detection, automatic categorization of offensiveness, and offense target identification, respectively.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 (Related Works) presents relevant studies of the OLID dataset and different models for detecting and categorizing offensive text, along with their contributions and limitations. Section 3 (Methodology) discusses this study’s overall process and procedure in detail. Firstly, we include a flow diagram to describe the overall architecture of this study. Then, we discuss the dataset, the procedure for dataset preprocessing, machine learning algorithms, evaluation criteria, and different techniques used in this study. Additionally, in Section 4, we describe the results with other relevant evaluation metrics and provide the necessary analysis with some visual data. We also compare the performance of different models and some significant approaches used in this study. Lastly, in Section 5 (Conclusions), we summarize the whole research, essential techniques, achieved results, and future plans for this study.

2. Related Works

Several studies have been conducted to detect and analyze offensive text. In this section, we briefly summarize some of the studies and their approaches to detecting offensive text on social media platforms.

Recognizing hate speech on social media is crucial to countering its negative impacts on vulnerable populations and society. This is a complicated task because hate speech can travel around freely, nonverbal clues are often used, and badly written language is frequently seen in social media posts. It is also challenging to define hate speech precisely, which makes it more difficult to compile extensive datasets for study. Addressing this, in study [11], Zampieri et al. present the findings from SemEval-2019 Task 6, which introduced the Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID) to identify and classify offensive language on social media. Over 14,000 English tweets are included in this task-specific dataset, which has been annotated with a fine-grained three-layer scheme for offensive content. There were three subtasks: identifying offensive language, offense type categorization, and identifying offense targets. The objective of Subtask A, “offensive language identification,” was for participants to identify offensive and non-offensive posts by categorizing language content and labeling it as “not offensive” or “offensive”. The best-performing model obtained an approximate F1 score of 0.829. In Subtask B, automated offense type classification was carried out by participants, who distinguished between untargeted profanity (UNT) and targeted insults (TIN) in posts deemed offensive in Subtask A. The top model obtained an F1 score of approximately 0.755. Participants in Subtask C, offense target identification, labeled offensive posts with targets like individuals (IND), groups (GRP), or other entities (OTH). For this job, the best F1 score obtained was roughly 0.66. More than 800 teams signed up for the study [11], and 115 of them submitted their findings. Prominent among the best-performing systems were deep learning models such as BERT. The frequency of inappropriate language on social media and the need for automatic filtering to safeguard human annotators are highlighted in the paper [11]. It ends with recommendations for more research, such as tackling class imbalance and growing the dataset. The hierarchical annotation methodology of the OLID dataset is designed to facilitate research in offensive language detection tasks.

However, there are limitations to OLID dataset [11], including a small and constrained dataset and shortcomings with class imbalance. There are many datasets that can be used to train a model to detect offensive language. SOLID [12] is one dataset that addresses the limitations of the OLID dataset; it includes over 9 million English tweets that have been annotated for offensive language. It was created without the need for laborious annotation through the use of a semi-supervised technique, and, to guarantee a representative sample, it was gathered from a diverse set of randomly selected tweets. Additionally, a democratic co-training strategy was used to annotate the dataset. This approach has been demonstrated to enhance classifier performance. The SOLID dataset does, however, have limitations. Since Twitter was the source of the data, it might not be representative of other social media platforms or online communities. Furthermore, since a democratic co-training approach was used to annotate the dataset, some noise or inaccuracies have been introduced into the annotations.

The difficulty of detecting hate speech on social media is discussed in the study by Kovács et al., 2021 [15], with a special emphasis on data scarcity in relation to the HASOC 2019 task [16]. Their primary contribution consists of investigating ways to improve hate speech detection efficiency by utilizing external resources. By analyzing the effects of limited training data and the efficacy of utilizing unlabeled data, similarly labeled corpora, and pretrained word representations, they expand on earlier research. With the incorporation of external resources, their proposed deep neural network (DNN) model, which combines convolutional and recurrent layers, achieves a macro F1 score of 0.63 on the HASOC 2019 corpus, indicating noteworthy improvements. Paper [15]’s applicability to other hate speech detection datasets is, however, limited, and the discussion mostly concentrates on data scarcity, ignoring other crucial elements like bias handling, traditionally accepted definitions of hate speech, and conventional text processing methods like stemming and pos tagging. Furthermore, efforts to mitigate bias and handling unbalanced data—two crucial factors in hate speech detection research—are not fully covered in the paper [15].

Huang et al., 2021 [13] explores the issue of offensive language identification within Dravidian languages, with a particular focus on Malayalam, Kannada, and Tamil social media comments. For classification tasks utilizing given datasets, the authors combine the Tf-Idf algorithm, multilingual BERT model, and CNN block. They highlight the negative effects of offensive language on social media and propose solutions to problems caused by code-mixing and special symbols in the data. The article [13] acknowledges its shortcomings and discusses the need for modifications to handle data imbalance issues, optimize classifiers for different language datasets, and prevent overfitting. The authors hope to encourage more research in this area by offering their recommendations for future improvement, which include improving data preparation techniques and taking code-mixing advances into account. However, there are a number of significant drawbacks, such as a lack of discussion of potential biases in the datasets used, a lack of analysis on the ethical implications of implementing such automated systems on social media, a lack of attention to the computational resources required, and an inadequate comparison with existing models. There is also a lack of examination of generalizability to other languages or platforms. Furthermore, due to the complexities of code-mixed language, the team faced difficulties preprocessing the data, such as tokenization and normalization, as well as dealing with class imbalance in the dataset.

The study by Ranasinghe et al., 2019 [9] offers a novel approach that makes use of capsule networks supplemented with emoji information in order to detect objectionable remarks on social media. In offensive language identification tasks, it outperforms earlier models, surpassing the SemEval-2019 Task 6 baseline in particular. Paper [9] demonstrates state-of-the-art outcomes using capsule networks, which are less common in NLP, and emphasizes the necessity of integrating emoji expertise for increased accuracy. The authors state their aim to investigate this architecture in more NLP applications and highlight the promise of capsule networks as a language-independent solution that may be used for a wide range of languages. Nevertheless, the study [9] does not include a thorough investigation of the system’s scalability or possible problems with scaling to additional social media platforms or larger datasets.

In paper [14], Abarna et al. introduce a systematic cyber harassment detection method utilizing FastText and Word2vec models, augmented by bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) models and part-of-speech (POS) tags. Despite challenges like dataset imbalance, the model demonstrates superior performance in precision, recall, accuracy, and F1 score compared with existing methods. Through the analysis of text lexical meaning and word order, it outperforms conventional classifiers, showcasing its practical relevance. Post COVID-19 lockdowns, the study [14] underscores the urgency for efficient cyber harassment detection. In conclusion, the proposed model offers a potent tool for accurately identifying cyberbullying instances and discerning user intent on social media platforms.

In study [10], an ensemble classifier of recurrent neural network (RNN) models is used to present a unique method for hate speech identification in tweets. The model greatly improves its effectiveness in classifying foul language by adding user-related information. With an astounding F-score of 0.9295, evaluation criteria including precision, recall, and F-score show how much better the suggested method is than current techniques. Interestingly, the model performs exceptionally well in identifying sexism, surpassing the performance of other algorithms such as FastText and demonstrating the efficacy of RNNs in this field. Nevertheless, the study [10] has drawbacks, such as the need for a larger dataset to represent the richness and diversity of abusive language, computational restrictions, and a lack of investigation into potential biases in the dataset. Notwithstanding these limitations, the incorporation of user behaviour data is essential for enhancing the accuracy of classification, highlighting the need for taking these aspects into account in hate speech detection tasks. In summary, the research conducted by [10] highlights the capability of deep learning models, specifically ensemble classifiers, to precisely detect and handle derogatory language on social networking sites such as Twitter.

Singh et al.’s paper [17] uses a variety of machine learning and deep learning models to identify violent behaviour in Hindi–English code-mixed social media discourse. Even with challenges including dataset homogeneity and data noise, the study uses a convolutional neural network (CNN) to achieve a noteworthy prediction accuracy of 73.2%. Notably, the research [17] underscores the necessity of adopting nuanced methodologies for identifying aggression, which extends beyond mere explicit language cues. Its pragmatic implications extend to the exploration of a wide array of social media content, complemented by the provision of accessible datasets and model resources for future inquiry. In conclusion, while the CNN model exhibits promising efficacy, the quest for a more diverse corpus of social media discourse remains imperative for further refining predictive outcomes.

Paper [18] introduces the Marathi Offensive Language Dataset v.2.0 (MOLD 2.0) and SeMOLD for offensive language identification in Marathi, addressing the scarcity of research in low-resource languages. Leveraging transfer learning from English and Hindi, the study [18] achieves significant performance improvements in Marathi offensive language detection tasks. However, limitations include the neglect of other languages and potential biases in annotations. While the feasibility of identifying offensive posts in Marathi is demonstrated, ethical considerations are not extensively discussed. Overall, the research [18] contributes to advancing offensive language identification in low-resource languages like Marathi, paving the way for further exploration in this field.

In study [19], Zhang et al. explores offensive language identification on Twitter using deep learning models, showcasing the effectiveness of convolutional neural networks and bidirectional LSTMs. Despite limitations such as heuristic reliance due to dataset constraints, it provides insights into model performance enhancement strategies and dataset analysis. Methodologically, it combines deep learning techniques for general offensive language identification with heuristic-based methods for targeted offense detection. The study [19] demonstrates competitive macro F1 scores, omitting details about the competition, and focuses on the practical implications of the proposed approaches.

Chen and his team in [20] delve into the intricacies of lexical syntactic feature (LSF) architecture for detecting offensive content and identifying potentially offensive users on social media, primarily focusing on adolescent online safety. It outperforms existing methods in offensive content detection, achieving high precision and recall rates. However, it primarily addresses the sentence and user levels of offensive language detection, lacking broader context detection across platforms or multimedia content. While effective, the LSF architecture may still face challenges in handling nuanced or context-dependent offensive language. Paper [20] also lacks detailed insights into the specific machine learning algorithms used for classifying users’ offensiveness levels and does not extensively discuss potential biases or ethical considerations in automated detection systems’ implementation. Nonetheless, the LSF framework in [20] shows promise for efficient deployment on social media platforms, indicating significant advancements in offensive language detection.

Paper [21] uses emotion-aware shared encoder models to improve the detection of abusive content. It uses emotional features in multi-task learning to improve hate speech detection and marginally improve foul language classification. The performance increases are limited by the imbalance in the dataset, but the multi-task models outperform the single-task models, lowering false positive errors. The paper highlights the potential of multi-task learning and emotional features to improve the detection of abusive language on social media platforms. The study uses the Davidson dataset for hate and offensive speech and the GoEmotion corpora, integrating emotional features with BERT and mBERT models. The inclusion of emotional knowledge aids in better identification of hate speech and offensive language, making the model more robust and effective in practical applications. The shared encoder boosts model efficiency and generalization, improving overall classification accuracy by 3%.

The research in [22] presents a technique that uses phrase vector embedding for better performance in detecting hate speech in code-mixed Tamil on social media. When coupled with phrase-based BiGRU, the hierarchical attention network model produced a high macro-F1 score of 0.93, outperforming previous models in terms of accuracy and macro-F1 scores. Although the unbalanced dataset had an impact on performance, focal loss models outperformed categorical loss models. The study highlights the value of creating automatic hate lexicons for various hate speech categories as well as the potential of phrase vector representations to improve hate speech identification. Future research will examine hate speech in more detail as well as the effects of phrase representations. The detection and categorization of hate speech on social media platforms is greatly advanced by this research.

Much research has already been conducted on offensive text detection on social media platforms. However, Table 1 summarizes the contributions and limitations of different studies.

Table 1.

Summary of contributions and limitations in different studies.

3. Methodology

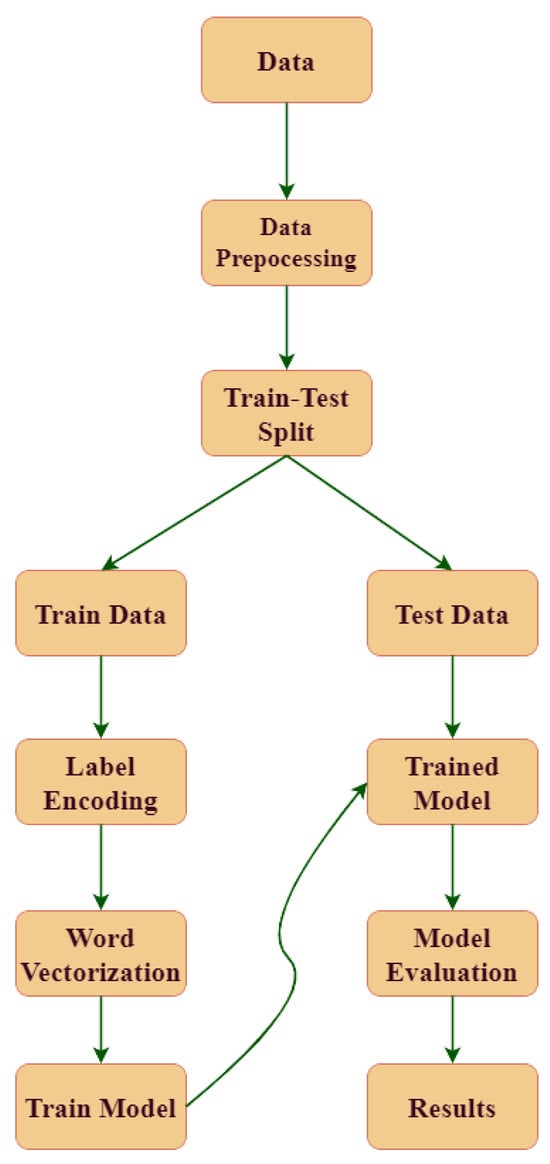

Utilizing a machine learning-based classifier, our goal is to identify and categorize objectionable phrases on social media. Our research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms in classifying tweets as offensive or not, identifying the types of crimes, and identifying the intended recipients of offenses. The flow diagram for our proposed technique is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the proposed architecture.

3.1. Data Description

This research uses a publicly available dataset named the Offensive Language Identification Dataset (OLID) [23]. In Table 2, we populated five random tweets from the dataset for better visibility and understanding of the OLID dataset. This dataset contains 13,240 annotated English tweets. The annotated tweets are labeled with the following three subtasks.

Table 2.

Five random tweets from the OLID dataset.

- subtask_a: offensive language detection.

- subtask_b: categorization of offensive language.

- subtask_c: offensive language target identification.

In subtask_a, which focuses on offensive language detection, OLID consists of three columns. The first column, “id”, serves as a unique identifier for each tweet in the dataset. The second column, “tweet”, contains the actual text of the tweets. The third column, “subtask_a”, is essential for this subtask as it holds labels indicating whether a tweet is offensive, with values like “OFF” for offensive and “NOT” for not-offensive.

- -

- Not offensive: this post does not contain offense or profanity.

- -

- Offensive: this post contains offensive language or a targeted offense

Subtask_b, the automatic categorization of offensiveness, follows a similar structure. It includes “id” for tweet identification, “tweet” for the tweet text, and “subtask_b” for categorizing offensive tweets into two categories: untargeted profanity (UNT) and targeted insults (TIN).

- -

- Targeted insults and threats: a post containing an insult or threat to an individual, a group, or others.

- -

- Untargeted: a post containing non-targeted profanity and swearing.

Subtask_c, offense target identification, also uses "id" and "tweet" columns for tweet identification and content, respectively. The third column, "subtask_c," is unique to subtask_c and specifies the specific target, such as individual (IND), group (GRP), or other (OTH).

- -

- Individual: the target of the offensive post is an individual (a famous person, a named individual, or an unnamed person interacting in the conversation).

- -

- Group: the target of the offensive post is a group of people considered as a unity due to the same ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, political affiliation, religious belief, or something else.

- -

- Other: the target of the offensive post does not belong to any of the previous two categories (e.g., an organization, a situation, an event, or an issue)

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

We made a number of changes to the original dataset during the data preprocessing phase in order to convert the raw data into a format that NLP models could interpret. In the ’tweet’ column of the dataset, we removed any missing values. Next, we converted every word to lowercase. Python treats “dog” and “DOG" differently, so this was necessary. The next step was word tokenization, which divides a text stream into meaningful components known as tokens, such as words, phrases, and symbols. The token list is used as input for additional processing. Lastly, WordNetLemmatizer needed Pos-tags [24] in order to determine the word’s type (default: noun), whether it is a verb, adjective, or noun. Common English stopwords that do not have much meaning were removed. We completed all of the procedures outlined above in order to prepare a dataset for subtask-a, which involves determining whether or not a tweet is offensive.

For subtasks b and c (offense types and offense target), we have drop rows that are not offensive, and others are the same as subtask-a.

3.3. Train–Test Split

During the train–test split, we divided the dataset into a training set and a test set in a 70:30 ratio. This means 70% of the data was allocated to the training set, while the remaining 30% was assigned to the test set. After the splitting, the training set had 2713 instances, and the test set consisted of 1163 data samples.

3.4. Label Encoding

In order to convert categorical data of the string type in the dataset into numerical values that the model can comprehend, the label encodes the target variable. For the subtask_a, we gave the labels “offensive” (1) and “not-offensive” (0). Similarly, for subtask_b, we labelled “targeted insults and threats” or TIN as 1 and “untargeted” or UNT as 0. Lastly, we labelled “individual” as 1, “group” as 2, and “other” as 3 for subtask_c.

3.5. Word Vectorization

Machine learning algorithms can interpret text more effectively thanks to word vectorization, which converts textual input into numerical vectors. To convert textual input into vectors that models can comprehend, there are a number of word vectorization approaches. In this study, TF-IDF was chosen for its effectiveness in text classification and categorization [25]. “TF-IDF,” which stands for “term frequency-inverse document frequency,” is the acronym for the factors that determine the scores assigned to each word in the resulting vectors. TF-IDF balances term frequency within documents against their rarity across the corpus, highlighting relevant and distinctive terms. This is crucial for detecting offensive language, because it is important to recognize and identify significant terms and important phrases. In contrast to bag-of-words (BoW) [26], which assigns equal weight to every word, TF-IDF gives features greater significance by lowering the weight of common words.

Despite their ability to capture complex semantic relationships in text, neural embeddings such as Word2Vec [27] and Doc2Vec [28] necessitate large and extensive amounts of data as well as computational resources. However, TF-IDF is less computationally intensive and efficient with smaller datasets, which makes it feasible for our study, considering the complexity and boundary-sensitive nature of offensive language detection. In order to fine-tune our models and guarantee reliable offense detection and classification, we need to be able to clearly grasp the significance of each feature, which is made possible by the interpretability and simplicity of TF-IDF vectors.

Term Frequency summarizes how often a word appears within a document.

Inverse Document Frequency downscales words that appear often across documents.

In Equations (1) and (2), w is a word, d is a document, and D is the corpus, N = D.

TF-IDF builds a vocabulary of words that it has learned from the corpus data, and it will assign a unique integer number to each of these words. There will be a maximum of 5000 uncommon words/features as we have set the parameter max_features = 5000.

Finally, we will transform Train_X & Test_X to vectorized Train_X_Tfidf & Test_X_Tfidf for training and testing. These dataframes will now contain a list of unique integer numbers and their associated importance, as calculated by TF-IDF.

3.6. Model Training

The model was trained using machine learning algorithms on the given training dataset. The complex relationships and patterns between the features and the labels that go with them had to be understood by these algorithms. Random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and artificial neural network (ANN) were three of the methods used. We experimented with different parameter configurations to fine-tune the hyperparameters, and finally chose the ones that produced the best-predicted accuracy in order to improve the model’s performance (listed in the Table 3).

Table 3.

Hyperparameters used in RF, SVM, and deep learning algorithms.

3.6.1. Random Forest (RF)

By averaging the predictions of an ensemble of decision trees, this model combines several subsets and improves accuracy for both classification and regression tasks. Compared with a single decision tree, its ensemble approach decreases issues like overfitting and boosts generalization. In addition, it can manage big datasets, offer a feature importance estimate, and keep high accuracy [29]. Because we utilized the hyperparameter n_estimators = 100, there will be 100 decision trees in the random forest.

3.6.2. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

The support vector machine (SVM) makes use of the concept of a hyperplane that maximizes the margin from the closest data points [30]. The hyperplane’s foundation is made up of the support vectors, or data points. The derivation of the hyperplane is influenced by these important data points, also referred to as support vectors. This hyperplane is established by using methods such as Manhattan distance, cosine similarity, and others, which guarantee the largest possible margin. In the end, the hyperplane makes a distinction between several classes.

The regularization parameter (c = 1.0) was employed, managing the compromise between optimizing the margin and reducing the classification error. The SVM’s decision boundary type is specified by the linear kernel, and degree = 3 denotes a cubic polynomial. Finally, gamma controls the kernel’s width; smaller values make the edge more flexible, while larger values make it more rigid.

3.6.3. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

The artificial neural network (ANN) is a deep learning-based computational model that mimics the human brain’s nerve cells. Training data pass through neurons/nodes, and the weights of nodes adjust accordingly. Each neuron contains an activation function to process the data and non-linear relationship between inputs. The network has three major layers—input, hidden, and output. In this network, all nodes or neurons are fully connected in two consecutive layers. We used a total of four sets of layers—one input layer, two hidden layers, and one output layer. We experimentally used different hyperparameters for optimal scores with low computational costs for each subtask.

In the input layer, we used the ReLU activation function with 128 dense layers. We used two sets of hidden layers in the network with multiple activation and dense layers. Finally, in the output layer, we used the sigmoid activation function with one dense layer. In addition, we also used other hyperparameters, such as optimizer-adam, ten epochs, batch size 32, etc.

3.7. Pseudocode

In Table 4, we explain the pseudocode for the proposed model’s architecture in detail. We built the model using Python (version 3.10.12) and different frameworks using Google Colab. We used frameworks like WordNetLemmatizer and TfidfVectorizer for data preprocessing, and random forest and support vector machine for training the model.

Table 4.

Pseudocode for proposed architecture.

3.8. Model Evaluation

During the model evaluation phase, we evaluated our machine learning models’ performance by utilizing several widely used measures, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Regardless of class, accuracy measures how accurate the model’s predictions are overall. It offers an evaluation of the general performance of the model.

Precision measures the percentage of predictions made by the model that are correct.

Recall measures the percentage of relevant data points that the model correctly identifies.

Finally, the harmonic mean of precision and recall is the F1 score.

In Equations (4)–(6), TP represents true positives, TN represents true negatives, FP represents false positives, and FN represents false negatives.

4. Result and Analysis

The results obtained from different models are presented in Table 5. The performance of the machine learning models were evaluated for subtasks a, b, and c using precision, recall, and F1 scores. We additionally utilized accuracy as a criterion to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the models.

Table 5.

Results obtained from models for subtask_a, subtask_b, and subtask_c.

The evaluation results for offensive language identification (subtask A) in tweets are shown in Table 5, where it is evident that the support vector machine (SVM) performed better than the random forest (RF) and artificial neural network (ANN) in multiple evaluation metrics. RF and SVM exhibited high accuracy, which was 77%, and ANN scored 73%. In terms of precision, SVM performed better than other algorithms, and ANN showed a high F1 score for subtask_a, which was 58%.

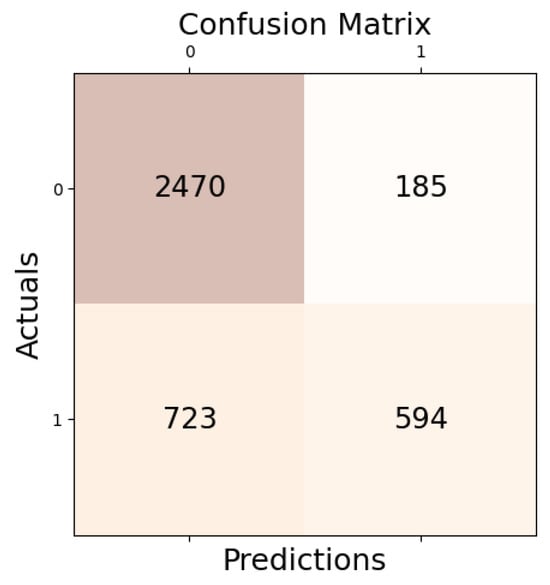

The confusion matrix of the SVM model for subtask A is shown in Figure 2. The superior performance of SVM over RF and ANN in accuracy and precision can be attributed to SVM’s ability to effectively identify relevant instances (true positives—594 and true negatives—2470) at the expense of misclassifying some non-relevant instances (false positives—185). This equilibrium is in line with the nature of offensive language identification, where it is essential to correctly identify offending tweets (maximizing recall), even at the cost of incorrectly classifying some non-offensive tweets as offensive (lowering precision).

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix of SVM for subtask_a.

The evaluation findings show that both the random forest (RF) and support vector machine (SVM) models performed admirably for offense type classification (subtask B), based on Table 5. But the ANN performance was not up to mark compared with RF and SVM. SVM achieved an 88% recall, F1 score, and accuracy, and 87% precision, which were the best scores. Random forest (RF) demonstrated an impressive performance with 87% accuracy, F1 score, recall, and precision. ANN achieved a very low F1 score (22%) and considerable accuracy (85%) compared with SVM.

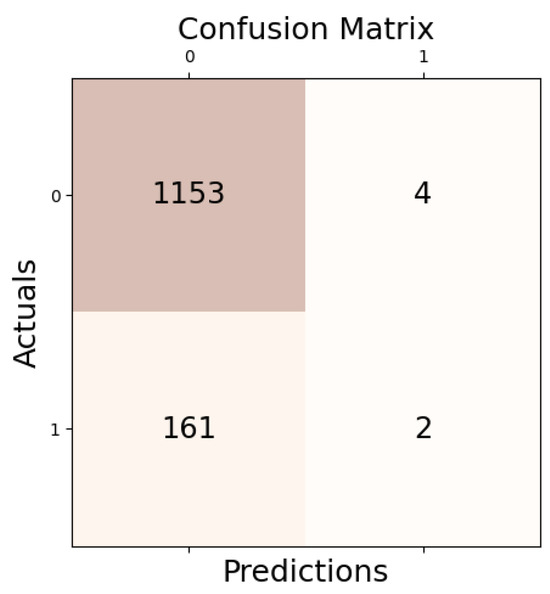

In subtask B, a thorough evaluation of the model’s performance in differentiating between targeted insults (TIN) and untargeted profanity (UNT) in offensive posts identified in subtask A was conducted by utilizing the micro average (averaging the total true positives, false negatives, and false positives) to calculate precision, recall, and F1 score. This approach provides a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance, particularly in jobs where a unified perspective across all classes is required or if there are class imbalances. RF and SVM demonstrated excellent performance; however, SVM slightly outperformed RF in all criteria, indicating consistent and dependable classification abilities for offense type classification. In support of the model’s high accuracy and F1 score, the SVM model’s confusion matrix for subtask B (Figure 3) offers more proof of the model’s effectiveness in offense type categorization.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix of SVM for subtask_b.

The evaluation results for the offense target identification subtask (C) are summarized in Table 5. The random forest (RF) and support vector machine (SVM) models demonstrated competitive performance in this challenge. Notably, the SVM model showed better precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy than the RF model. However, ANN scores are not as good as SVM.

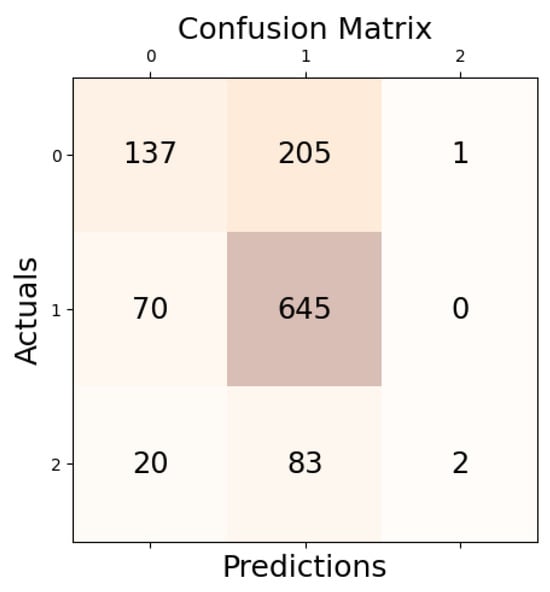

In subtask C, which involved identifying offensive targets, the micro average approach was also utilized to calculate precision, recall, and F1 score by averaging the total number of true positives, false negatives, and false positives. From Table 5, results show that the SVM model performed marginally better than the RF and ANN. SVM showed a well-balanced approach to target recognition, with an accuracy and F1 score of 68%.

A comprehensive analysis of the SVM model’s performance in subtask C can be found in the confusion matrix (Figure 4). This matrix highlights even more how well the SVM can pinpoint the precise individuals or groups that offensive information in tweets is intended for. The model’s consistent effectiveness in offense target identification is demonstrated by its strong F1 score and accuracy.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix of SVM for subtask_c.

We used effective text-processing techniques like TF-IDF to minimize computational cost and find only important words in the dataset. Later, we used RF, SVM, and ANN to analyze those important words further and determine whether they were offensive with other subtasks. This simple architecture exhibited remarkable performance yet was computationally efficient compared with the existing benchmark model. Relevant benchmark models are based on deep learning architecture and require high computational efficiency. However, we detected offensive posts using machine learning algorithms and texting processing techniques, while achieving outstanding performance and maintaining computational costs.

The superior performance of SVM over RF and ANN can be attributed to several factors. Regarding situations where distinct classes need to be defined, SVM stands out in our context, separating offensive (OFF) from non-offensive (NOT), untargeted profanity (UNT) from targeted insults (TIN), and targets such as individuals (IND), groups (GRP), and other entities (OTH) in tweets. Support vectors are crucial data points that define these boundaries, and SVM efficiently finds them, enabling a more precise and nuanced classification. Additionally, SVM’s ability to handle high-dimensional spaces and non-linear relationships through kernel functions, coupled with optimal parameter tuning (e.g., regularization parameter and kernel type), contributed to its enhanced discriminatory power in this task compared with RF’s ensemble approach based on decision trees. On the other hand, ANN requires a large dataset for better performance, and OLID is a medium-sized dataset. We also tried different combinations of ANN’s hyperparameters for optimal results. SVM proved to be the superior model in this study, considering offensive language detection’s complex and boundary-sensitive nature.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have proposed a comprehensive framework for the detection and categorization of offensive language on social media utilizing machine learning techniques, specifically support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and artificial neural network (ANN). Our methodology addresses multiple subtasks, including offensive language detection, automatic categorization of offensiveness, and offence target identification, by leveraging novel data preparation techniques and optimizing the model. Through our work with the OLID dataset, we have shown the efficacy and robustness of SVM in offensive language identification across a wide range of subtasks. SVM specifically outperformed RF in terms of accuracy, F1 score, and recall rate, and outperformed ANN in terms of accuracy and precision, proving that it can effectively identify offending information while taking a balanced approach. For example, SVM obtained 77%, 88%, and 68% accuracy scores, 76%, 87%, and 67% precision scores, with F1 values of 57%, 88%, and 68% for offensive language detection, automatic categorization of offensiveness, and offence target identification, respectively. The success of this methodology, which combines cutting-edge data preprocessing techniques, including TF-IDF vectorization, word tokenization, and text normalization, is demonstrated by this study. Our model outperformed prior benchmarks in related research’s offensive language recognition, offensiveness classification, and offense target identification tasks by integrating advanced preprocessing with careful hyperparameter tuning. Our study further emphasizes the significance of machine learning techniques in developing a safer and more inclusive digital world. With careful hyperparameter adjustment, the SVM, RF, and ANN algorithms demonstrate how useful they may be in social media content moderation scenarios. Moving forward, our future research directions focus on mitigating dataset biases, examining more ensemble techniques’ neural networks, and investigating the applicability of our methodology for multilingual languages and social media networks. By integrating these technologies, we aim to contribute to the ongoing efforts towards creating safer and more respectful digital communities.

Author Contributions

M.N.H., K.S.S. and T.T.P. worked on conceptualization, prepared the original draft, visualization, and project administration part of this research. The other elements such as the methodology created by M.N.H.; investigation done by K.S.S.; T.T.P. accumulates resources; data curation by T.T.P. and K.S.S. However, this whole research was supervised by J.U. and funding was acquired by J.A. and A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number 445-9-958.

Data Availability Statement

This study used a publicly available dataset named OLID. https://sites.google.com/site/offensevalsharedtask/olid, accessed on 10 April 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Petrosyan, A. Internet and Social Media Users in the World 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Musil, S. Twitter Rolls out Refined Prompts to Combat Harmful Language. Available online: https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/twitter-rolls-out-refined-prompts-to-combat-harmful-language/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Rosen, G. Hate Speech Prevalence Has Dropped by Almost 50% on Facebook. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2021/10/hate-speech-prevalence-dropped-facebook/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Perez, S. In the Wake of Recent Racist Attacks, Instagram Rolls out More Anti-Abuse Features. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2021/08/11/in-the-wake-of-recent-racist-attacks-instagram-rolls-out-more-anti-abuse-features/ (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Abbasova, M. Language of social media: An investigation of the changes that soft media has imposed on language use. In Proceedings of the 9th International Research Conference on Education, Language and Literature, Tbilisi, GA, USA, 3–4 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zachlod, C.; Samuel, O.; Ochsner, A.; Werthmüller, S. Analytics of social media data—State of characteristics and application. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1064–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, A.M.K.; Gunasekeran, D.V. Social Media Big Data: The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly (Un)truths. Front. Big Data 2021, 4, 623794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feezell, J.T.; Conroy, M.; Gomez-Aguinaga, B.; Wagner, J.K. Who Gets Flagged? An Experiment on Censorship and Bias in Social Media Reporting. PS Political Sci. Politics 2023, 56, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.; Ranasinghe, T. Emoji Powered Capsule Network to Detect Type and Target of Offensive Posts in Social Media. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing (RANLP 2019), Varna, Bulgaria, 2–4 September 2019; Mitkov, R., Angelova, G., Eds.; INCOMA Ltd.: London, UK, 2019; pp. 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsilis, G.K.; Ramampiaro, H.; Langseth, H. Effective hate-speech detection in Twitter data using recurrent neural networks. Appl. Intell. 2018, 48, 4730–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Malmasi, S.; Nakov, P.; Rosenthal, S.; Farra, N.; Kumar, R. SemEval-2019 Task 6: Identifying and Categorizing Offensive Language in Social Media (OffensEval). In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–7 June 2019; May, J., Shutova, E., Herbelot, A., Zhu, X., Apidianaki, M., Mohammad, S.M., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.; Atanasova, P.; Karadzhov, G.; Zampieri, M.; Nakov, P. SOLID: A Large-Scale Semi-Supervised Dataset for Offensive Language Identification. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, Online, 1–6 August 2021; Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Bai, Y. HUB@DravidianLangTech-EACL2021: Identify and Classify Offensive Text in Multilingual Code Mixing in Social Media. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Speech and Language Technologies for Dravidian Languages, Kyiv, Ukraine, 19 April 2021; Chakravarthi, B.R., Priyadharshini, R., Kumar M, A., Krishnamurthy, P., Sherly, E., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Abarna, S.; Sheeba, J.; Jayasrilakshmi, S.; Devaneyan, S.P. Identification of cyber harassment and intention of target users on social media platforms. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, G.; Alonso, P.; Saini, R. Challenges of Hate Speech Detection in Social Media. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Saini, R.; Kovács, G. TheNorth at HASOC 2019: Hate Speech Detection in Social Media Data. In Proceedings of the Working Notes of FIRE 2019—Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation, Kolkata, India, 12–15 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Varshney, A.; Akhtar, S.S.; Vijay, D.; Shrivastava, M. Aggression Detection on Social Media Text Using Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Abusive Language Online (ALW2), Brussels, Belgium, 31 October 2018; Fišer, D., Huang, R., Prabhakaran, V., Voigt, R., Waseem, Z., Wernimont, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Ranasinghe, T.; Chaudhari, M.; Gaikwad, S.; Krishna, P.; Nene, M.; Paygude, S. Predicting the Type and Target of Offensive Social Media Posts in Marathi. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mahata, D.; Shahid, S.; Mehnaz, L.; Anand, S.; Singla, Y.; Shah, R.R.; Uppal, K. Identifying Offensive Posts and Targeted Offense from Twitter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.09072. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, S.; Xu, H. Detecting Offensive Language in Social Media to Protect Adolescent Online Safety. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2012 International Confernece on Social Computing, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 3–5 September 2012; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnassri, K.; Rajapaksha, P.; Farahbakhsh, R.; Crespi, N. Hate Speech and Offensive Language Detection Using an Emotion-Aware Shared Encoder. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications, Rome, Italy, 28 May–1 June 2023; pp. 2852–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, V.S.; Kannimuthu, S.; Madasamy, A.K. The Effect of Phrase Vector Embedding in Explainable Hierarchical Attention-Based Tamil Code-Mixed Hate Speech and Intent Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 11316–11329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, M.; Malmasi, S.; Nakov, P.; Rosenthal, S.; Farra, N.; Kumar, R. Predicting the type and target of offensive posts in social media. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.09666. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, L.; Padro, L.; Rodriguez, H. A machine learning approach to POS tagging. Mach. Learn. 2000, 39, 59–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani, D.E.; Patasik, I. Performance comparison of tf-idf and word2vec models for emotion text classification. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2021, 10, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qader, W.A.; Ameen, M.M.; Ahmed, B.I. An Overview of Bag of Words;Importance, Implementation, Applications, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Engineering Conference (IEC), Erbil, Iraq, 23–25 June 2019; pp. 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S. Research on the Improved Word2Vec Optimization Strategy Based on Statistical Language Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems (ISPDS), Xi’an, China, 14–16 August 2020; pp. 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, H.B.; Tilki, S.; Jamil, A.; Ali Hameed, A. Deep Learning-Based Classification of News Texts Using Doc2Vec Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 1st International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics (CAIDA), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 6–7 April 2021; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonlau, M.; Zou, R.Y. The random forest algorithm for statistical learning. Stata J. 2020, 20, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.; Iqbal, N.; Ahmad, R.; Kim, D.H. WR-SVM model based on the margin radius approach for solving the minimum enclosing ball problem in support vector machine classification. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).