Abstract

This paper investigates the construction method of pandiagonal magic cube. First, we define a pandiagonal Latin cube. According to this definition, the cube can be constructed by simple methods. After designing a set of orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes, the corresponding order pandiagonal magic cube can be constructed. In addition, we give the algebraic conditions of the universal diagonal Latin cube orthogonality and the strict theoretical proof. Based on the proposed method, it can be shown that at least pandiagonal magic cubes of order n is formed through a pandiagonal Latin cube. Moreover, our method is easy to implement by computer program.

MSC:

05B15

1. Introduction

A square matrix of order n, composed of continuous natural numbers from 1 to , is called the magic square of order n if the sums of elements in each row, column and diagonal are the same. This sum is called magic sum, and it is equal to [1]. Magic square is one of the important research objects of combinatorial design. It is applied in the fields of image processing, computer science, and cryptography [2,3,4]. The study of magic squares can be traced back to ancient China. The “Luoshu” discovered 4000 years ago is a magic square of order three [5]. Thereafter, there has been a lot of research on magic squares, and magic squares in these studies have different characteristics [6,7,8]. If the sums of the numbers on each pandiagonal are the same in a magic square, this magic square is called pandiagonal magic square. The so-called pandiagonal refers to the “broken diagonal” paralleled to the diagonal, and wrap round at the edges of the square [9,10]. For example, let a magic square be , then , , ⋯, , are elements of a pandiagonal. There are also other pandiagonals. After extending a magic square to the three-dimensional, a magic cube is obtained. An integer magic cube of order n is a three-dimensional array which consists of the numbers , with each section and six diagonal planes being magic squares. Previous studies have given the construction methods of concrete magic cubes with various characteristics [11,12,13]. If every cross section, every diagonal and every pandiagonal of the magic cube is a pandiagonal magic square, it is called a pandiagonal magic cube. The relevant concepts are strictly defined below.

An integer cube of order n is a three-dimensional array which consists of the numbers 1, 2, ⋯, . Matrices , , are called cross sections. In particular, , , are called surfaces. Similarly, matrices , , , , , are called diagonal planes.

Definition 1.

An integer cube is called a pandiagonal magic cube, if all of its cross sections and diagonal planes are pandiagonal magic squares.

The concept of pandiagonal magic square can be found in [6,7,8,14]. Because a line parallel to an edge of an integer cube is a row or a column of a cross section, a great diagonal is a diagonal of a diagonal plane, so that a pandiagonal magic cube is certainly a magic cube [15].

The studies of magic squares and magic cubes have made relatively rich achievements. Cammann and Andrews introduced the early research results of magic squares and magic cubes [12,16]. Abe put forward 23 questions about magic squares, involving basic magic squares, pandiagonal magic squares, sparse magic squares, anti-magic squares, etc., which promoted the study of magic squares [17]. Loly et al. [18], Lee et al. [19], Nordgren et al. [20], and Hou et al. [21] discussed the algebraic properties of magic squares. Trenkler proposed an algorithm for making magic cubes [22]. However, the study on pandiagonal magic cubes is rare.

In this paper, we will study the existence and construction of pandiagonal magic cubes of order n based on the pandiagonal magic square idea in [6]. The following is the outline of this paper. First, a three-dimensional auxiliary cube is defined and its properties are discussed. Then, based on the discussion of Latin cube and pandiagonal Latin cube, the design method of the pandiagonal Latin cube is given. At the same time, we give the necessary and sufficient conditions for the orthogonality of three pandiagonal Latin cubes. Finally, by using the orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes, the construction method of pandiagonal magic cubes is obtained. In addition, we give a method to find another two pandiagonal Latin cubes orthogonal to one known pandiagonal Latin cube.

2. Auxiliary Cube and Its Properties

In this section, the definition and properties of the auxiliary cube are shown.

Definition 2.

A cube which consists of consecutive integers from 1 to is called an Auxiliary Cube (hereafter written as Aux Cube) if it satisfies the following conditions:

(1) The top surface is an auxiliary matrix [6], namely satisfies

(2) The cross sections and satisfy

where is independent of i and j.

The preceding conditions (1) and (2) are equivalent to the fact that each cross section is an auxiliary matrix [6].

Let

then is called Natural Auxiliary Cube. Clearly, by interchanging two parallel cross sections of an Aux Cube A, we can form other Aux Cubes. A is an Aux Cube if, and only if, A can be obtained from Natural Aux Cube through finite interchanges of parallel cross sections in succession. Because there are permutations of , we can create Aux Cubes from Natural Aux Cube by interchanging parallel cross sections.

Lemma 1.

Let A be an Aux Cube of order n, then the sum of any n entries in different rows, different columns and different levels is the same. Namely, if , , , are all permutations of , then

Proof.

Assume

Then we have

Suppose that

are n entries in different rows, different columns, and different levels of A. This is equivalent to the fact that “”, “”, “” are all permutations of . The sum of these entries is given by

The last three terms are independent of “”, “”, “”. This completes the proof. □

Let A be an Aux Cube. From Lemma 1, a pandiagonal magic cube can be obtained by adjusting the entries of A so that its each row, each column and each pandiagonal of its each cross section and each diagonal plane consists of entries in distinct rows, distinct columns and distinct levels of A, respectively.

Definition 3.

The integer cube A of order n consisting of is said to be a pandiagonal Latin cube if all of its cross sections and diagonal planes are pandiagonal Latin squares [6].

Definition 4.

A set of pandiagonal Latin cubes , , is called orthogonal if entries of the cube

run through all ordered three-tuples to [8,23].

For an integer cube , its entries have three subscripts i, j and k. The set of first integers, i.e., i’s, form another integer cube, and similarly for the second and third ones. It is not difficult to understand the following fact. If is an Aux Cube, , , are orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes. Define as

Then B is a pandiagonal magic cube. Therefore, we can construct a pandiagonal magic cube as follows. First, construct a set of orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes, and join them into a cube of 3-tuples, and then change entries into entries of some auxiliary cube so that the subscripts are these three-tuples. This provides a pandiagonal magic cube.

If we use the first, second and third subscripts of each element in a pandiagonal magic cube to form a number cube in the original order, respectively, three orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes can be obtained.

In this paper, we will use a transformation , whose definition can be found in [6]. Let be a permutation of . is a square matrix such that the first row is

and the second row is

By using the same rule, we form third row, and so on, to obtain , which is written as

For example, is given by

3. Special Case: A Pandiagonal Magic Cube of Order 11

In this section, an example of a pandiagonal magic cube of order 11 is revealed.

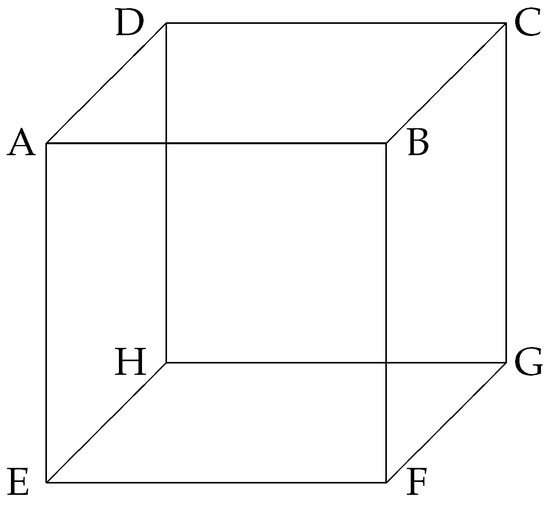

First, we construct a pandiagonal Latin cube of order 11. Let Figure 1 represent the integer cube. Let the first row of top surface, namely be

Figure 1.

A Integer Cube.

From [6], in order that is a pandiagonal Latin square, it suffices to select some k, , such that (because is a prime number). Let k = 7, i.e., let the back surface be :

Then take s, , , for example, . Apply to each row of to obtain 11 horizontal cross sections. They form the integer cube -, the top surface of which is :

The second cross section under the top surface is :

etc. We denote the cube - as , since the above cube is constructed by and .

Now, we turn to prove that the cube is a pandiagonal Latin cube of order 11. First, it should be noted that cross sections parallel to the top surface are all pandiagonal Latin squares. The back surface is also a pandiagonal Latin square. It follows from symmetry of the top and back surfaces that cross sections parallel to back surface are also pandiagonal Latin squares. We have to prove that cross sections parallel to and the six diagonal planes are pandiagonal magic squares. The surface is given by

This is just right . Similarly, we can prove that all cross sections parallel to are created through applying to some column of top surface. Thus they are all pandiagonal Latin squares. The diagonal plane is given by

which is , a pandiagonal Latin square. The diagonal plane is

We see that the above square is , a pandiagonal Latin square. The diagonal planes , , , and are, respectively, given by

They are all pandiagonal Latin squares.

The preceding facts make clear that the cube is a pandiagonal Latin cube.

By the same method, we can construct and . It can be shown that they are all pandiagonal Latin cubes, and that , , are orthogonal.

Now we construct cube of three-tuple , where , , . For example, the top surface of L is given by

By using this cube of 3-tuple L, we construct the integer cube with

Then C is a pandiagonal magic cube which is shown in Appendix A.

4. Main Results and Their Proofs

Our purpose is for any integer n to derive existence conditions of pandiagonal magic cubes of order n and to study a construction method by using the approach developed in Section 3. First, we construct three orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes, and then join them into a cube of ordered three-tuples. By replacing elements of the cube into elements of some auxiliary cube, we obtain a pandiagonal magic cube.

Let be any permutation of . Without loss of generality let it just be . Otherwise, it suffices to prove the result for first, then change j into . Since this transformation changes a permutation of into another permutation of , the following discussion is valid in general.

Taking as an edge, we construct an integer cube - as follows (see Figure 1). Assume , . Let the back plane be . Apply to each row of to obtain n horizontal cross sections. They form the integer cube -. Denote it by or briefly .

Now let us study sufficient conditions such that is a pandiagonal Latin cube. By using the same method as in Section 3, we easily follows that parallel cross sections of the cube have identical generating transformation for some t. Sections parallel to pandiagonal sections of also have identical generating transformation for some . Therefore it suffices to find conditions, such that , , , and six diagonal sections are pandiagonal Latin squares. For pandiagonal Latin squares, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let n and k be integers with . Then is a pandiagonal Latin square of order n if, and only if,

Here, means that i and j are mutually prime, namely, the maximum common factor of i and j is equal to 1.

When n is a prime number, the proof of this theorem can be found in [6]. The proof of general situation requires the following two preliminary facts.

Lemma 2.

If the first column of is a permutation of , so is every column of .

Proof.

We regard an element of as itself modulo n, then (j is an integer. We choose representative elements of congruence group of modulo n as . Hereafter suppose just so). Consider numbers in the bracket [ ]. Since

it is clear that if 1, , ⋯, is a permutation of , so are i, , ⋯, (, 2, ⋯, n). This proves the Lemma. □

Lemma 3.

If some diagonal of is a permutation of , so is each pandiagonal which is parallel to the diagonal. If some pandiagonal of is a permutation of , so is each pandiagonal which is parallel to the pandiagonal.

Proof.

Since , we can substitute i for for some j. The following are the first n rows of

From the generating rule, we see that the first n columns just form . Since , , the last n columns also form . Hence the line from to is a diagonal. The line from to stands for the pandiagonal , and the line from to stands for the pandiagonal . Since is a diagonal, are all pandiagonals which parallel to line . Thus, if one of them is a permutation of , then so are others. The proof for pandiagonals which are parallel to diagonal is the same. This completes the proof of Lemma 3. □

(Proof of Theorem 1).

Sufficiency. Suppose the conditions hold. From Lemmas 2 and 3, it suffices to prove that the first column and two diagonals are permutations of . From the definition of , its first column is

i.e., the difference of two successive elements is . Since , if , the first column is a permutation of .

Similarly, the difference of two elements of the diagonal starting from is . It follows at once from that the diagonal is a permutation of . Similar proof is applicable to another diagonal because and .

Necessity. Suppose one of the conditions does not hold. For example, let . So there exists integers p and q, such that , , . Thus the first column of is . Since , the pth element is equal to the first element. This implies that the first column is not a permutation of , which is a contradiction. The other cases are treated similarly. This completes the proof of Theorem 1. □

The following is one of the main theorems of this paper.

Theorem 2.

Let , . Suppose that the following conditions are satisfied

(1) , , ;

(2) , , ;

(3) , , ;

(4) , , .

Then the preceding is a pandiagonal Latin cube, where is a permutation of , and vice versa.

Proof.

We show that the conditions – are necessary and sufficient so that each surface and each diagonal section is a pandiagonal Latin square.

Because the surface is , is a necessary and sufficient condition such that is a pandiagonal Latin square. Similarly, is a necessary and sufficient condition such that is a pandiagonal Latin square.

The left surface is given by

From Theorem 1, in order that this surface be a pandiagonal Latin square, necessary and sufficient conditions are

These are included in –.

The diagonal section is . It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

These are exactly conditions in .

The diagonal section is given by

i.e.,

It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

i.e.,

These conditions are also included in –.

The diagonal section is

In order that this section be a pandiagonal Latin square, necessary and sufficient conditions are

i.e.,

These conditions are included in –.

The diagonal section is

It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

i.e.,

These conditions are also included in –.

The diagonal section is

It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

These conditions are also included in –.

The diagonal section is

It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

This is the condition .

The diagonal section is

It is a pandiagonal Latin square if, and only if,

These conditions are included in –. The proof is completed. □

Remark 1.

We observe that if is a pandiagonal Latin cube, so is . Since conditions – of Theorem 2 are symmetric with respect to s, k.

Corollary 1.

Let n be a prime number. Then if

are satisfied, is a pandiagonal Latin cube.

Proof.

Immediate from Theorem 2. □

Now we give the second main theorem of this paper.

Theorem 3.

Suppose are pandiagonal Latin cubes. They are orthogonal if, and only if, the determinant

and n are coprime, i.e., .

Proof.

Without loss of generality it suffices to prove that if, and only if, number 1, which is on the common vertex of , cannot appear on another common place. Indeed, if 1 appears again on common place , then there are relations

Thus there exist integers , such that

This is a system of linear equations for . The determinant of coefficient matrix is

From cyclic group theory [24], if, and only if, there is a unique solution of system (1) with , , . Since is a solution, there is no other solution. The proof is complete. □

From this theorem we obtain the following result.

Corollary 2.

Let be three pandiagonal Latin cubes of order n. In order that they are orthogonal, two necessary conditions are

Not all of are the same;

Not all of are the same.

We prove . If , then

It is not coprime with n. The proof of is similar.

The following theorem give a method of generating orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes from a given pandiagonal Latin cube.

Theorem 4.

Suppose is a pandiagonal Latin cube. Choose integers α, β, , , such that

Then are orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes.

Proof.

The proof is performed in five steps. Steps (a) to (d) show that is a pandiagonal Latin cube. Step (e) shows that are orthogonal. For convenience we denote , by , , respectively.

(a) We prove of Theorem 2, i.e.,

1. If , i.e., and n have a common factor d which is larger than 1:

where p and q are positive integer, . Substituting (4) into (2) yields

i.e.,

This can be written as

This means d is a common factor of and n, i.e., . This contradicts assumptions. Thus, the relation is true.

2. If , then there is which is a common factor of and n. So we obtain

Therefore, . This contradicts assumptions, so that we have .

3. If , then there exists an integer , such that

So . This is a contradiction. Thus .

(b) We prove of Theorem 2, i.e.,

1. If , then there exists which is a common factor of and n:

This means . This is a contradiction. So .

2. If , then there exists which is a common factor of and n:

This means d is a factor of number 1, a contradiction. So .

3. If , then and n have a common factor :

So . This is a contradiction. Thus .

(c) We prove of Theorem 2, i.e.,

1. If , then there exists which is a common factor of and n:

By applying (3), we obtain

This means . This is a contradiction. So .

2. If , then there exists which is a common factor of and n:

Because of (3), this can be written as

i.e.,

This means . This contradicts the assumption. So .

3. If , then there exists which is a common factor of and n such that

Because of (3), this can be written as

i.e.,

This means . This contradicts assumption. So .

(d) We prove of Theorem 2, i.e.,

1. If , then and n have a common factor :

From (3), we obtain

So . This is a contradiction. Thus .

2. If , then and n have a common factor :

Using (3), we obtain

So . This is a contradiction. Thus .

3. If , then and n have a common factor :

It follows from (3) that

So . This is a contradiction. Thus .

(a), (b), (c), and (d) above show that satisfy the conditions of Theorem 2, so that is a pandiagonal magic cube. Now we have three pandiagonal magic cubes .

(e) We now turn to prove the orthogonality of . First, construct three determinants:

From assumptions of (2), (3), we have . Therefore, we obtain

Note that , so . Because is a pandiagonal Latin square (third condition (2) and first condition (4) in Theorem 2), . Compounded with , we have , so . From Theorem 3 it follows that are orthogonal. This completes the proof. □

The following theorem give another method to construct orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes.

Theorem 5.

Suppose , . If the conditions

(1) ;

(2) ;

(3) , ;

(4)

are satisfied, then , , , are all pandiagonal Latin cubes and three of them are orthogonal.

Proof.

For or , the conditions of Theorem 2 are satisfied. Then , , , are all pandiagonal Latin cubes.

In addition,

and n are coprime if, and only if, . However, this is true because , , .

Hence from Theorem 3, any three of them are orthogonal. This completes the proof. □

Now, we can construct a pandiagonal magic cube by using Natural Aux Cube. We obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 6.

Let be orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes. Construct integers cube , where

Then C is a pandiagonal magic cube.

Proof.

Consider any section or diagonal S of C. According to the properties of pandiagonal Latin cubes, take the complete permutation of on any row, column or pandiagonal line of S. When adding the elements of C on such a row, column, or pandiagonal, there is

They are all equal to magic sum, so C is a pandiagonal magic cube. □

If a set of orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes is given, we can construct 6 pandiagonal magic squares. This is because there exist six arrangements of three pandiagonal Latin squares and there are permutations of .

Next, we give some examples of satisfying the Theorems and Corollaries.

Example 1.

For n = 11, computer studies show that there exist 23 pandiagonal Latin cubes which satisfy the conditions of Corollary 1, and there are 9870 orthogonal sets. For example, three orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cube sets are , , .

Example 2.

Suppose n = 143.

Let , , , , , .

Then they satisfy the conditions of Theorem 3.

Example 3.

For n = 121, let

, , , .

, , ,

, , ,

These are three sets of parameters such that orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes satisfy the conditions of Theorem 4.

5. Further Property

The pandiagonal magic cube considered in the foregoing sections has further interesting properties.

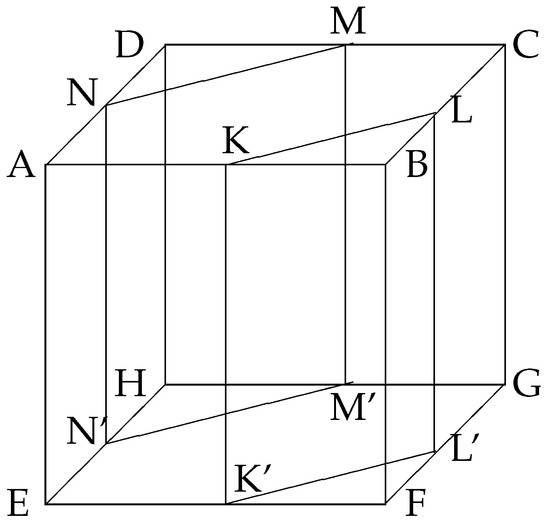

Let - in Figure 2 be an integer cube, and - be a pandiagonal line on the top surface . Using two planes which are parallel to the edge , we can cut - into three parts. Let cross sections be and . Through parallel translation, we obtain a square matrix (or ), which is called a pandiagonal plane. There are six sets of such planes, where each set has n pandiagonal planes which are parallel to each other.

Figure 2.

The Integer Cube--.

A pandiagonal plane of a pandiagonal magic cube is also a pandiagonal magic square. In fact, let us begin with a pandiagonal Latin cube. Let - be a pandiagonal Latin cube, then its each pandiagonal plane has the same generating transformation with the diagonal plane parallel to itself. For example, the diagonal plane of of Section 3 is given by

A pandiagonal plane parallel to is

They are all generated by . This fact can be proved in general. Because of this and the fact that all of diagonal planes are pandiagonal magic squares, pandiagonal planes are all pandiagonal magic squares for a pandiagonal magic cube.

As an example, in Appendix B, we give a set of pandiagonal planes of the pandiagonal magic cube shown in Appendix A. They are cross sections of another pandiagonal magic cube. In other words, if is a pandiagonal magic cube, then (here [ ] expresses modulo n, we define that [0] = n) is also a pandiagonal magic cube. Similarly, , , , , are all pandiagonal magic cubes. Appendix B shows .

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have defined a kind of magic cube called pandiagonal magic cube, whose cross sections and diagonal planes are pandiagonal magic squares. We have given a construction method for this pandiagonal magic cube. First, we construct three orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes, join them into a cube of three-tuples, and then replace entries by entries of some auxiliary cube so that the subscripts are these three-tuple. The last cube is a pandiagonal magic cube. If we have a pandiagonal Latin cube, Theorems 4 and 5 tell us how to construct a set of orthogonal pandiagonal Latin cubes. Some examples are also included. The construction method of pandiagonal magic cubes proposed in this paper can be extended to higher dimensions.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, F.L.; Writing—review and editing, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The following are the sections of the pandiagonal magic cube generated by , and .

Appendix B

The following is a set of pandiagonal planes of the pandiagonal magic cube in Appendix A. They form another pandiagonal magic cube.

References

- Sesiano, J. Magic Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy, G.; Mani, K. Add-on security model for public-key cryptosystem based on magic square implementation. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–22 October 2009; Volume 1, pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Loly, P.D. Franklin squares: A chapter in the scientific studies of magical squares. Complex Syst. Champaign 2007, 17, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Ollerenshaw, K.; Bree, D. Most-perfect pandiagonal magic squares. Math. Today Bull. Inst. Math. Its Appl. 1998, 34, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Swetz, F.J.; Luo, R. Legacy of the Luoshu. Aust. Math. Soc. 2008, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Fucheng, L. Construction of Pandiagonal Magic Squarey of Odd Order. Chin. J. Eng. 1992, 14, 594–598. [Google Scholar]

- Fucheng, L. Pandiagonal Magic Squares. Chin. J. Eng. 2001, 23, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell, A.D.; Denes, J. Latin Squares and Their Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.X.; Lu, Z.W. Pandiagonal magic squares. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 1995, 959, 388–391. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wu, D.; Pan, F. A construction for doubly pandiagonal magic squares. Discret. Math. 2012, 312, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, W.H.; Jacoby, O. Magic Cubes: New Recreations; Courier Corporation: Chelmsford, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, W.S. Magic Squares and Cubes; Open Court Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1917. [Google Scholar]

- Trenkler, M. A construction of magic cubes. Math. Gaz. 2000, 84, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candy, A.L. Construction, Classification and Census of Magic Squares of Order Five; Edwards Brothers: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, A.; Li, S.Y.R. Magic cubes and Prouhet sequences. Am. Math. Mon. 1977, 84, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammann, S. The evolution of magic squares in China. J. Am. Orient. Soc. 1960, 80, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, G. Unsolved problems on magic squares. Discret. Math. 1994, 127, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loly, P.; Cameron, I.; Trump, W.; Schindel, D. Magic square spectra. Linear Algebra Appl. 2009, 430, 2659–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Z.; Love, E.; Narayan, S.K.; Wascher, E.; Webster, J.D. On nonsingular regular magic squares of odd order. Linear Algebra Appl. 2012, 437, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, R.P. On properties of special magic square matrices. Linear Algebra Appl. 2012, 437, 2009–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houa, X.D.; Lecuonab, A.G.; Mullenc, G.L.; Sellersd, J.A. On the dimension of the space of magic squares over a field. Linear Algebra Appl. 2013, 438, 3463–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkler, M. An algorithm for making magic cubes. π ME J. 2005, 12, 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Arkin, J.; Hoggatt, V.E.; Straus, E.G. Systems of magic Latin k-cubes. Can. J. Math. 1976, 28, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, T.W. Algebra; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).