Abstract

We consider the evolution of a finite population constituted by susceptible and infectious individuals and compare several time-inhomogeneous deterministic models with their stochastic counterpart based on finite birth processes. For these processes, we determine the explicit expressions of the transition probabilities and of the first-passage time densities. For time-homogeneous finite birth processes, the behavior of the mean and the variance of the first-passage time density is also analyzed. Moreover, the approximate duration until the entire population is infected is obtained for a large population size.

Keywords:

population growth models; probability distribution of the number of infections; duration of the epidemic; first-passage time density; asymptotic behaviors MSC:

60J27; 60J28; 60J35; 60J80; 92D25

1. Introduction

We consider a “closed” population of a total constant size N. This population is divided into two qualitatively distinct regions and , types or compartments, and we assume that only one-way migration from to can occur and that, at time , there are individuals in and j individuals in . We denote by the number of individuals in the region at time , with , so that individuals at time have migrated from to . The growth of the population in can be described using a finite birth process, the birth of an individual in the region being due to the migration of an individual from . The average time required for all individuals to migrate from to the region is a significative parameter to analyze. The stochastic processes that describe the evolution of a population in which the individuals can only be born are discussed, for instance, in Bailey [1], Bharucha-Reid [2], Cox and Miller [3], and Taylor and Karlin [4].

In epidemiology, compartment models are known as “epidemic models” and are often applied to the mathematical modeling of infectious diseases (cf. Allen [5,6], Dailey and Gani [7]). The simplest compartment models assume an individual can be in one of only two states, either susceptible (S) or infectious (I). For , we denote by the number of susceptible individuals, by the number of individuals infected, and by N the total population size, where is constant. It is assumed that there are no removals of, no immunities to, and no recoveries from infection. The susceptible individuals become infected through contact with infectious individuals.

A compartmental model with two states can be described with ordinary differential equations in the deterministic dynamics and via finite birth processes in the stochastic approach, which is more realistic but more complicated to analyze. Such models try to predict how a disease spreads, the total number infected, the duration of an epidemic and allow for estimating the various epidemiological parameters. Not all diseases are accurately described by a model with only two states, but a two-state model is useful in describing some classes of micro-parasitic infections to which individuals never acquire a long-lasting immunity and, over the course of the epidemic, everyone eventually becomes infected. An example of a two-state epidemic model is the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Since HSV is a viral infection, it is transmitted via skin to skin contact with infected areas. This form of disease is difficult to control because many individuals who are infected unknowingly spread the disease. The antivirals can help reduce the severity and frequency between breakouts, but there is no cure, so the infected population continues to grow indefinitely. Another example of such a disease is the Cytomegalovirus (CMV), that has the ability to remain latent within the human host.

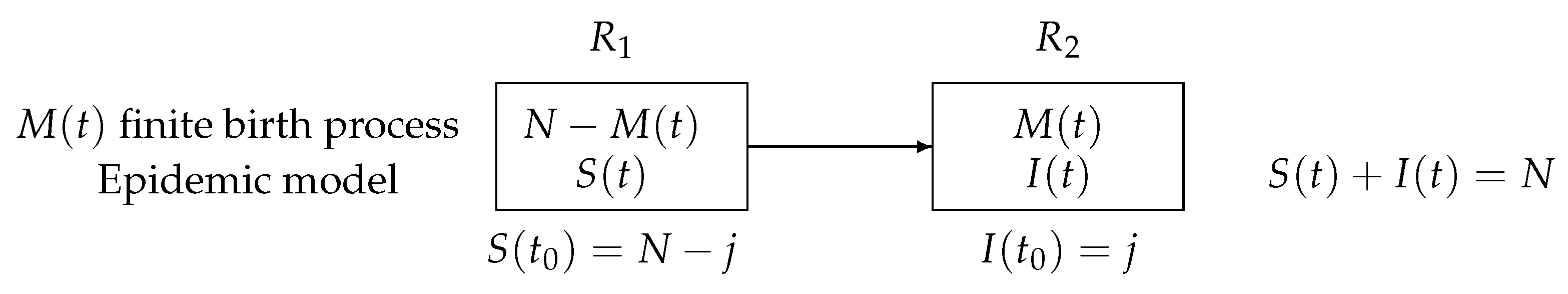

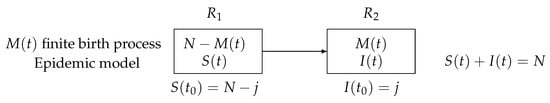

In Figure 1, a schematic compartmental representation with two states is given.

Figure 1.

A schematic compartmental representation with two states: susceptible and infectious.

Discrepancies are often observed between the real data and theoretical predictions due to more or less intense environmental fluctuations. One way to overcome this problem is to consider a stochastic approach to the phenomenon. Both deterministic and stochastic models can be used to capture the dynamic of infection in the population and are alternate viewpoints on the same phenomenon, offering complementary insights. The predictions in the deterministic models are determined entirely by their initial conditions, the set of underlying differential equations, and the input intensity functions. The model, based on a system of ordinary differential equations, can be thought of as a deterministic skeleton of any corresponding stochastic model. Starting with a family of ordinary differential equations, which describes a dynamical system, one can arrive at a variety of corresponding stochastic models by interpreting some or all the deterministic rates as stochastic rates. The approach based on continuous-time Markov chains is preferable to the one based on stochastic differential equations, because the former preserves the discrete values of the population. In our study, the number of infected individuals in the population is described using a finite birth process (see, for instance, Bailey [1,8], Cox and Miller [3], and Taylor and Karlin [4]). Recent developments in mathematical modeling, with applications in the transmission of infection in population dynamics, are investigated and analyzed in studies by Anggriani et al. [9], Joseph et al. [10], and Jose et al. [11,12].

In two-state stochastic epidemic models, the main purpose of the study is to determine the probability distribution of the number of infected individuals as a function of time, to determine the expected duration until the infected population size reaches N, and to obtain some asymptotic approximations for large N.

Plan of the Paper

In Section 2, we revisit a variety of time-inhomogeneous (TNH) deterministic epidemic models with two states, either susceptible (S) or infectious (I). We study the growth of the infected population and we determine the deterministic time required until individuals of the population are infected. In Section 3, we consider the TNH finite birth process with birth intensity functions for and we determine the transition probabilities for when the birth intensity functions are all distinct, and in the case in which they are not necessarily distinct. The general expression of the first-passage time (FPT) probability density function (pdf) is obtained for . Moreover, the FPT mean and the FPT variance are explicitly evaluated for the time-homogenous (TH) birth process. In Section 4, we take into account the flexible finite birth process in which . For this process, we determine the partial differential equations for the probability generating function (PGF) and for the cumulant generating function (CGF). Moreover, the asymptotic behavior of the mean size of the population is analyzed for large N. Special attention is dedicated to the FPT densities and to the FPT moments for the TNH-binomial birth process , TNH-quadratic birth process , and TNH-SI birth process . In Section 5, we consider the stochastic hyper-logistic birth process in which , with . The FPT pdf and the FPT moments are studied for different choices of the parameter . For the TH-binomial, TH-quadratic, TH-SI, and TH-hyper-logistic birth processes, the numerical results show that the deterministic time required until individuals of the population are infected is always included in the interval , where denotes the average of the FPT from j to k. Various numerical computations are performed with MATHEMATICA to analyze the role played by the parameters.

2. Deterministic Epidemic Models with Two States

We consider some deterministic epidemic models with two states, either susceptible (S) or infectious (I).

2.1. Flexible Birth Model

The following is a flexible two-state epidemic model:

with for , where , , and the transmission intensity function is a positive, bounded, and continuous function of t. The replacement of into (1) leads to the flexible growth curve for , described with the following differential equation:

whose solution for is as follows:

where

Indeed, by making the change of variable in (2), one obtains the differential equation ; by solving this last equation and recalling the performed change of variable, one is led to (3). Since , with , is an increasing function of t, if , at the end, every individual of the population becomes infected, i.e., . Moreover, if for all t, one has the following:

- If , no inflection point exists;

- If , a unique inflection point in (3) exists that occurs at the levelwhen , otherwise no inflection point exists.

The time until the infected population size reaches N is infinite, because N is approached asymptotically. To obtain an estimate of the time required until individuals of the population are infected, we solve the equation . For the flexible model with , by virtue of (3), one has the following:

We remark that the flexible model includes the Bass model, which is used in marketing and forecasting to describe the diffusion of new products, services, or innovations. The Bass model can be expressed mathematically as follows (cf. Mahajan et al. [13], Guidolin and Manfredi [14]):

with and , where is the number of adopters at time t, N is the potential market size (the total number of potential adopters), is the coefficient of innovation (the rate at which early adopters adopt the product), and is the coefficient of imitation (the rate at which late adopters adopt the product). Indeed, by choosing , , and , Equation (2) identifies with the Bass differential Equation (6).

There are three special cases of the flexible model obtainable by choosing appropriately the parameters and : the binomial model, quadratic model, and SI model.

2.1.1. Binomial Birth Model

2.1.2. Quadratic Birth Model

2.1.3. SI Birth Model

For and in (1), one obtains the SI model

with for . Equation (11) leads to the Verhulst logistic growth curve for described with the following differential equation:

the solution of which is

In the Verhulst logistic model (12), if , the inflection point occurs at the level when .

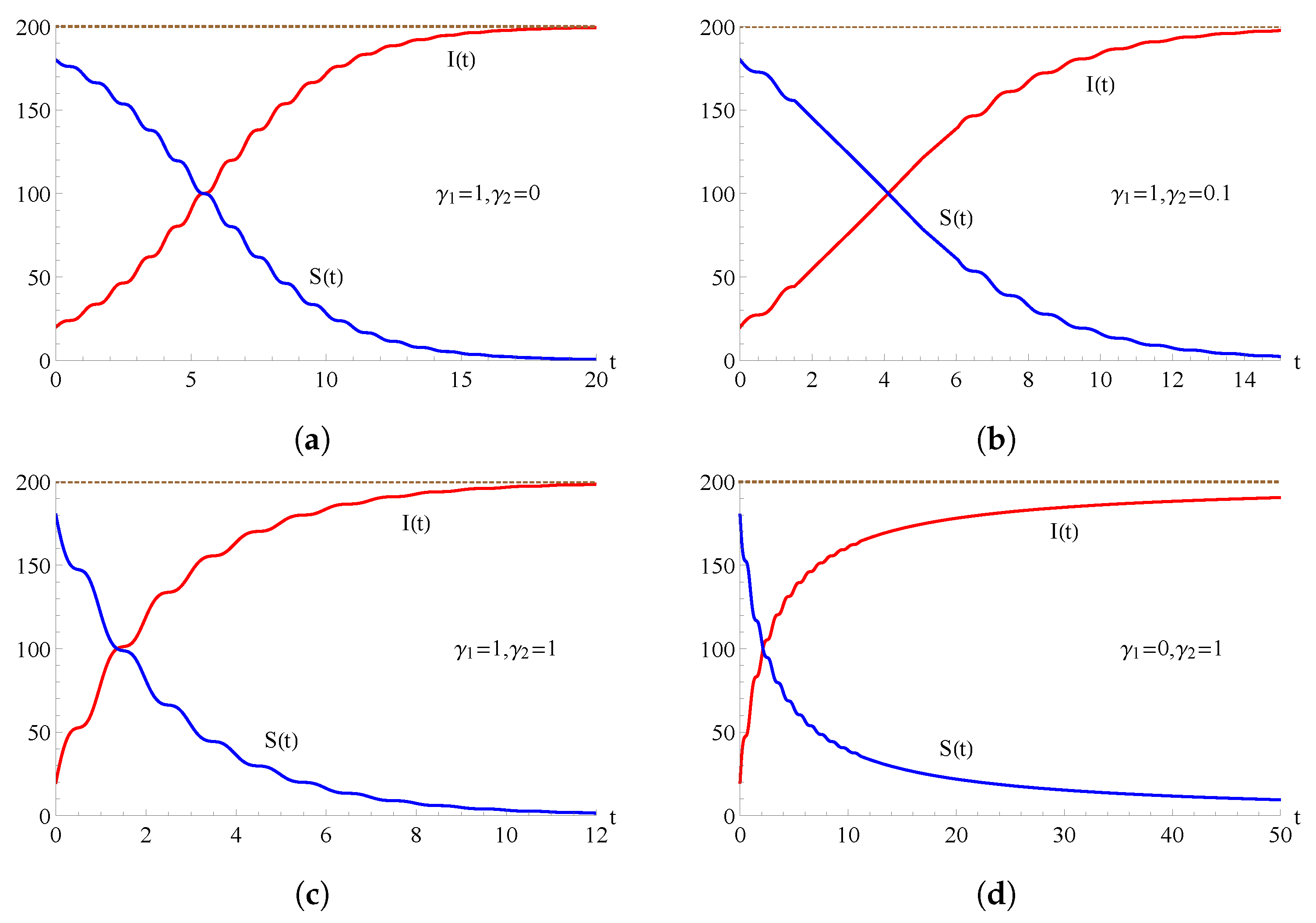

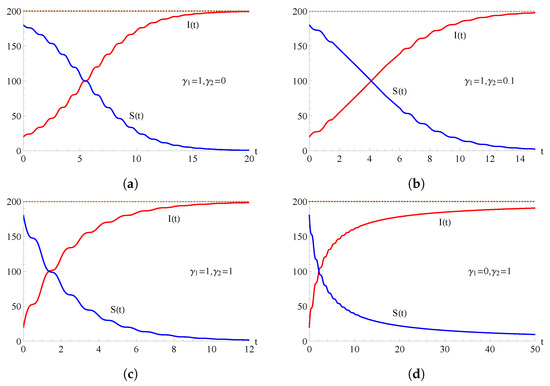

In Figure 2, we consider the flexible two-state epidemic model (1) with ; the curves and are plotted as functions of t for , , , and for some choices of the parameters and . Figure 2a refers to the SI epidemic model, Figure 2c relates to the binomial epidemic model, and Figure 2d puts emphasis on the quadratic epidemic model.

Figure 2.

For the flexible model with , the population of the infected (red curve) and of the susceptible (blue curve) are plotted as functions of t for , , , and for some choices of the parameters and . In (a) , in (b) , in (c) and in (d) .

In Table 1, for the binomial, SI, and quadratic models, the duration until individuals of a population are infected is indicated for , , , and various choices of . The values of in Table 1 are obtained from (5) by setting for the binomial model, , for the SI model, and , for the quadratic model.

Table 1.

The duration , given in (5), is indicated for , , , and various choices of .

2.2. General Finite Birth Models

In two-state epidemic models, it is often realistic to introduce an interaction term of the form , where the dependence on the number of infected individuals occurs via a nonlinear bounded function (cf. Dong et al. [15]).

with for . In particular, if , with , , , one obtains the flexible growth curve (3) for .

Hyper-Logistic Birth Model

If in (13), with , one obtains the hyper-logistic model described by the differential equation for

whose solution is as follows (cf. Turner et al. [16], Anguelov et al. [17], and Albano et al. [18]):

Indeed, by performing the change of variable in (14), one has the differential equation ; by solving this last equation and recalling the considered change of variable, one obtains (15). In particular, when the hyper-logistic growth curve (15) converges to the Verhulst logistic growth curve (12), being

Moreover, when , Equation (15) identifies the quadratic growth curve (10).

The hyper-logistic model, defined using Equation (14), helps to overcome the major limitation of the Verhulst logistic model: the inflexibility of the inflection point. Specifically, in the Verhulst logistic model, the inflection point is fixed at , whereas, in the hyper-logistic curve (15), with and for all t, the inflection point occurs at the level when and it does not exist otherwise. Moreover, for the hyper-logistic model with , the duration until individuals of a population are infected is

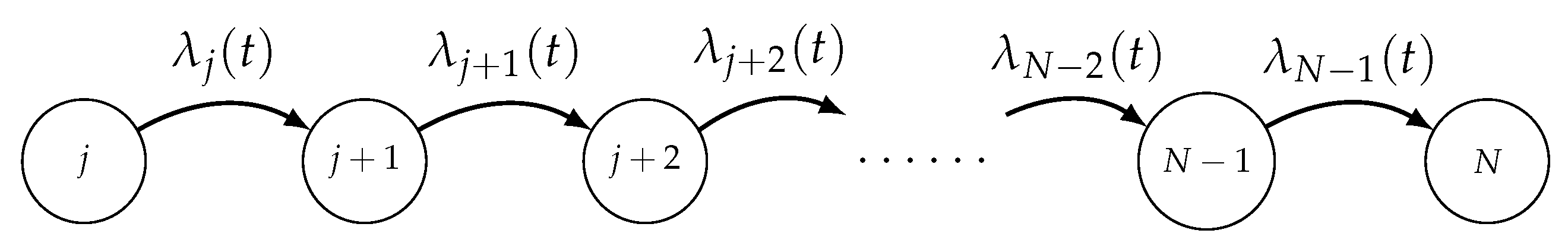

In Figure 3, we consider the hyper-logistic two-state epidemic model with ; the curves and are plotted as functions of t for , , , and for some choices of the parameter p.

Figure 3.

For the hyper-logistic model with , the population of the infected (red curve) and of the susceptible (blue curve) are plotted as functions of t for , , , and for some choices of the parameter p. In (a) and in (b) .

In Table 2, for the hyper-logistic model, the duration , given in (16), is indicated for , , , and various choices of and p.

Table 2.

For the hyper-logistic model, the duration is listed for , , , and various choices of and p.

As highlighted in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the intersection of the two curves at the level represents an equilibrium where the numbers of susceptible individuals and infected individuals are equal. After the equilibrium point, the population includes more infected individuals and fewer susceptible individuals. This trend continues until, ultimately, every individual is included in the infectious population so that, ultimately, the whole population becomes infected.

We remark that the hyper-logistic differential Equation (14) is a special case of the Blumberg growth model

where and are shape parameters. The Blumberg growth model (17) is an extension of the Verhulst logistic growth equation and is used to describe several demographic, economic, ecological, and biological models (cf. Blumberg [19], Rocha and Aleixo [20]). By setting and in (17), we obtain the hyper-logistic growth differential Equation (14).

We note that, in all the deterministic models previously considered, the results are as follows:

- The form of the transmission intensity function has a significant impact on the population dynamics of the infected and of the susceptible ;

- is an increasing function of t and is a decreasing function of t;

- If , at the end, all individuals of the population are infected, i.e., ;

- The time T until the infected population size reaches N, i.e., , is actually infinite because N is approached asymptotically;

- The duration until individuals of a population are infected provides a measure of the growth time of the infection in the epidemic model.

3. The Stochastic Finite Birth Process

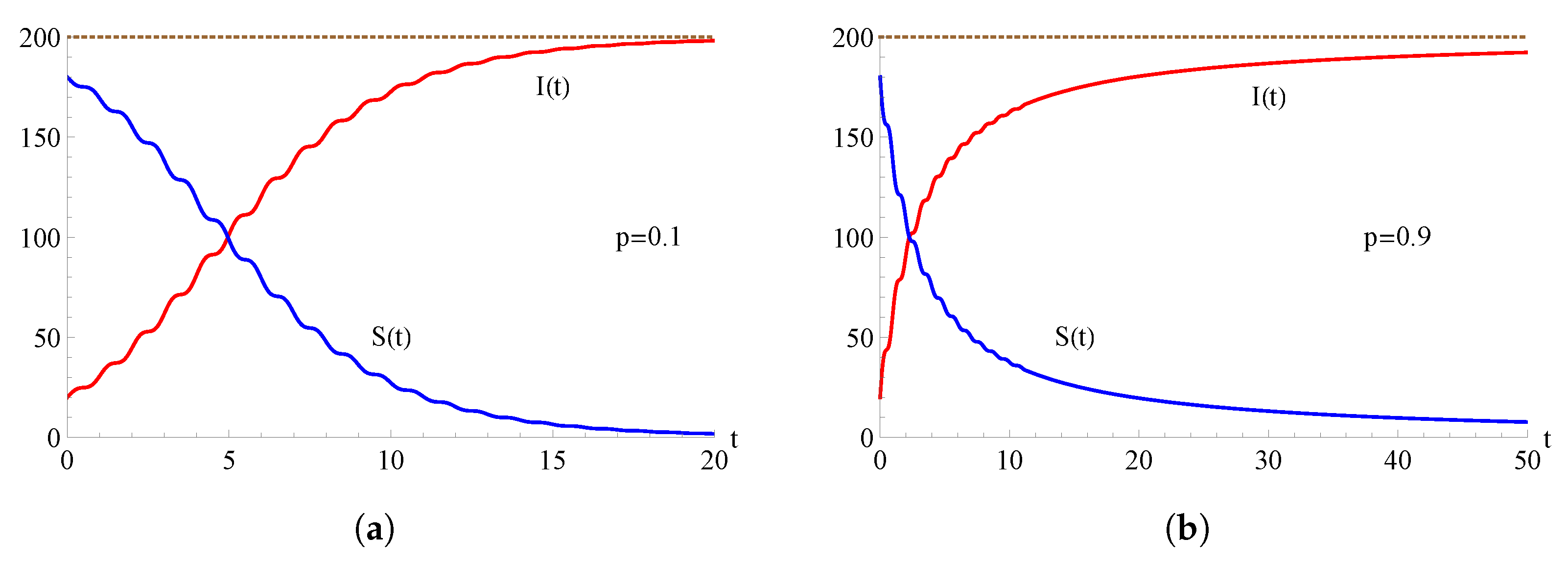

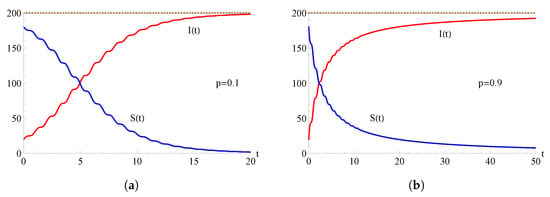

Let be a TNH finite birth process having state-space , , with birth intensity functions , where N denotes the constant total population size (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The state diagram of the TNH finite birth process .

To reach the size n from its initial size j, the population goes from j to , then from to , …, at end from to n, in this precise order.

In epidemiology, the process describes the number of infected individuals and represents the number of susceptible individuals at time t. Once infected, and with no treatment, individuals stay infected and remain in contact with the susceptible population.

For the finite birth process , we assume that the births at time t occur with intensity functions given by

where depends on the state n of the system (number of infected individuals) and where is a positive, bounded, and continuous function of t. In Equation (18), the dependence of on t defines the type of process. If is constant for all t, the process is TH, whereas if is a function of t, then the process is TNH. In a study by Faddy and Fenlon [21], stochastic models based on TH finite birth processes of type (18) are constructed to describe the invasion in parasite–host systems and various forms for the birth (invasion) rates are proposed. Marrec et al. [22] describe the population growth as a stochastic birth process and compare the average size of the population with the solution obtained via the deterministic approach.

For , let

be the transition probabilities of . They satisfy the Kolmogorov forward equations:

with the initial condition , where is the Kronecker delta function. For the TNH finite birth process , with birth intensity functions (18), one has . Moreover, from the first equation in (19), one obtains the following:

where is defined in (4).

To determine the transition probabilities of , we consider the TH finite birth process obtained from by setting in (18) and we denote by the transition probabilities of . From (19), we note that

with . Therefore, we now focus on the evaluation of the transition probabilities of .

We denote by the Laplace transform (LT) of the transition probability :

Taking the LT in (19) with and , and recalling the initial condition, one has the following:

Solving Equation (22) using consecutive iterations, one finds the following:

By taking the inverse LT in the first equation in (23), one has so that, by virtue of (21), one obtains (20). Moreover, for , the determination of the inverse Laplace transforms of via (23) can be obtained by focusing on the sequence of rates and on the multiplicity of the roots of the denominators. Then, via (21), one can derive the required probabilities of .

Following this approach, we now determine the transition probabilities for the birth process under the assumption that the birth intensity functions are all distinct.

Proposition 1.

For the TNH finite birth process , if the birth intensity functions , defined in (18), are all distinct, i.e., if

this results in the following:

where, for one has the following:

and .

Proof.

Since (24) holds, a partial fraction expansion of the right-hand side of (23) then yields the following:

where the coefficients

When , by comparing (27) with the first of (23), one has , whereas Equation (26) follows from (23) and (28) for . In particular, for one has

Hence, by taking the inverse Laplace transform of (27), one obtains the following (cf. Erdèlyi et al. [23], p. 232, n. 20):

from which, due to (21), Equation (25) follows. □

Under the assumptions of Proposition 1, if from (25) one has and for .

For a TH finite birth process , the results of Proposition 1 are in agreement with those given in the study of Bharucha-Reid [2], p. 185, for .

We now determine the transition probabilities for the process under the assumption that the birth intensity functions are not necessarily distinct. To this aim, for fixed j and n, with , we consider the sequence of birth rates and we denote by the distinct values of the sequence and we indicate by their respective multiplicities, with and .

Proposition 2.

Let j, n and N be fixed parameters, with . For the TNH finite birth process , with intensity functions defined in (18), this results in the following:

where for and one has the following:

Proof.

We suppose that j, n, and N are fixed parameters, with . To determine the inverse LT of , given in (23), we consider the polynomial of degree in s

that appears in the denominator of the right-hand side of (23). For fixed j and n, by taking into account the distinct roots and their multiplicity, the polynomial (31) can be also be written as follows:

Therefore, from (23), one has the following:

Since the degree (zero) of polynomial at the numerator in (32) is less than , taking the inverse Laplace transform of (32), for one obtains the following (cf. Erdèlyi et al. [23], p. 232, n. 21):

with given in (30). Hence, recalling (21), Equation (29) follows. □

Remark 1.

First-Passage Time

For the TNH finite birth process , with birth intensity functions (18), let

be the FPT random variable from the initial state j to the state , and we denote by

the pdf of . For one has the following (cf. Giorno and Nobile [24,25]):

Equation (33) has a simple interpretation. Indeed, can be obtained by taking into account the probability of those realizations that reach the state at time t starting from j, and then with probability reach k in the interval . We note that, if , the FPT through k starting from j is a sure event.

For the process , with birth intensity functions (18), the r-th FPT conditional moment is as follows:

In particular, provides the pdf of the time in which all individuals in the population become infected starting from j infected individuals at time and are the related conditional moments. Moreover, if , by virtue of (20), the average of the FPT from to N can be obtained from (34):

4. Stochastic Flexible Finite Birth Process

The stochastic process , with intensities functions , given in (18), includes the TNH flexible birth process characterized by

where , and . The flexible birth process constitutes the stochastic counterpart of the deterministic model of infected population growth discussed in Section 2.

For the flexible birth process , we consider the PGF

Making use of (19) and (37), we note that is the solution of the partial differential equation

with the initial condition . Moreover, the CGF , with , of the TNH-flexible birth process is a solution of the partial differential equation

with the initial condition . Then, the conditional average and the conditional variance of can be obtained from as follows:

From (39) and (40), we note that, for the flexible birth process , the first two conditional moments satisfy the partial differential equation

The solutions of (38) and of (39) are generally difficult to obtain, with the exception of the case , in which the Equations (38) and (39) reduce to first-order partial differential equations.

The following proposition allows for determining the asymptotic behavior of the conditional mean for TNH-flexible birth process as the total size N diverges.

Proposition 3.

For the NTH-flexible birth process , one has the following:

Proof.

From (41), recalling (39) and (40), one has the following:

with the initial condition . To solve Equation (43), we consider the TH flexible birth process obtained from by setting and denote by

From (43), for , one obtains the Riccati differential equation

with the initial condition . Since is a particular solution of (44), by taking the change of variable , one obtains the homogeneous linear differential equation:

Solving this equation and applying the inverse transformation , one has the following:

Since, from (21), one has , Equation (42) follows from (45). □

From (3), for the deterministic flexible model, one also obtains . Hence, the deterministic solution of the flexible model and the condition mean of the TNH-flexible birth process have the same asymptotic behavior as , i.e.,

Some special cases of the TNH-flexible finite birth process used in epidemiology are indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Special cases of TNH-flexible finite birth processes .

In particular, by setting in (37), describes the binomial birth process; moreover, and in (37), and gives the quadratic birth process. Finally, when and in (37), identifies with the SI birth process. In the remaining part of this section, we analyze these birth processes.

4.1. Binomial Birth Process

Let be a TNH-binomial birth process having birth intensity functions for . In this case, in (18) we set .

We note that the TNH-binomial birth process is obtainable from the Prendiville process, with birth intensity functions for and death intensity functions for , by setting . The Prendiville process is considered in studies by Giorno et al. [26], Zheng [27], Giorno and Nobile [28], and Usov et al. [29].

Proposition 4.

For the TNH-binomial birth process , one has the following:

Proof.

The result (46) can be obtained following two different approaches: by using the PGF or via Proposition 1.

The conditional mean and variance of the binomial birth process are as follows:

We note that, by setting , the deterministic solution (8) of the binomial model for the infected population identifies with the average (49) of the binomial birth process . Moreover, if , the conditional mean approaches N and the conditional variance go to zero as t increases.

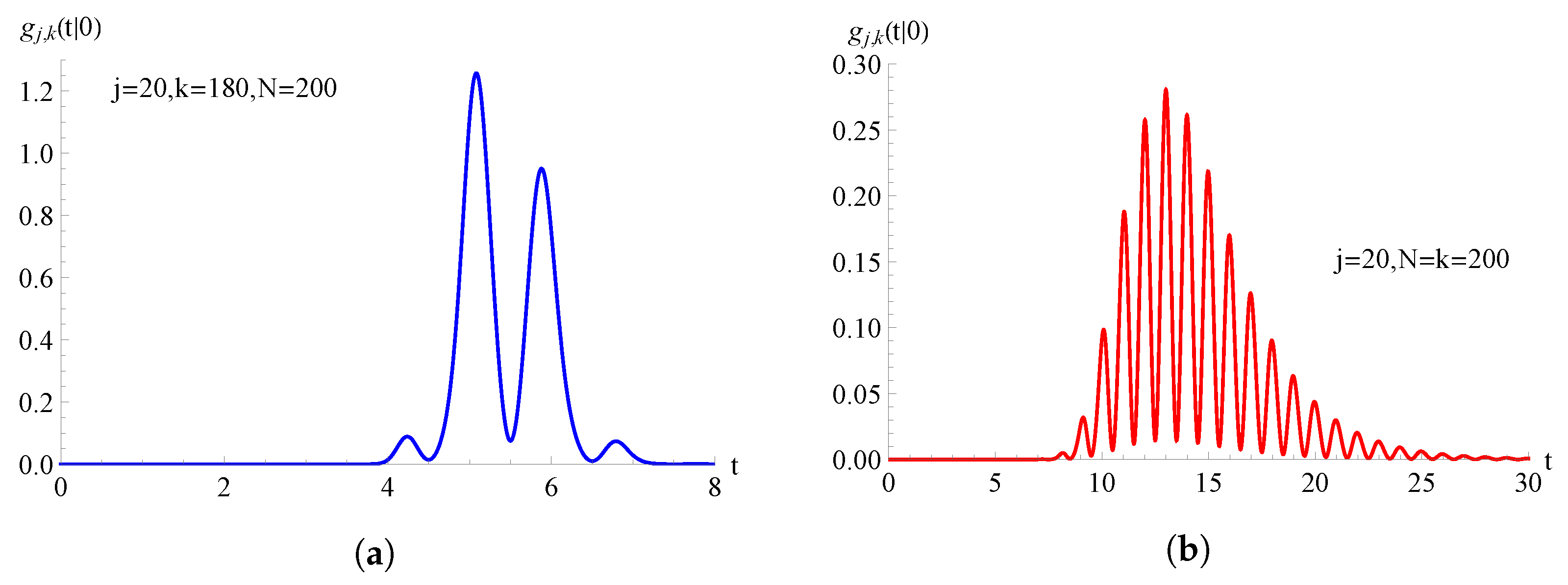

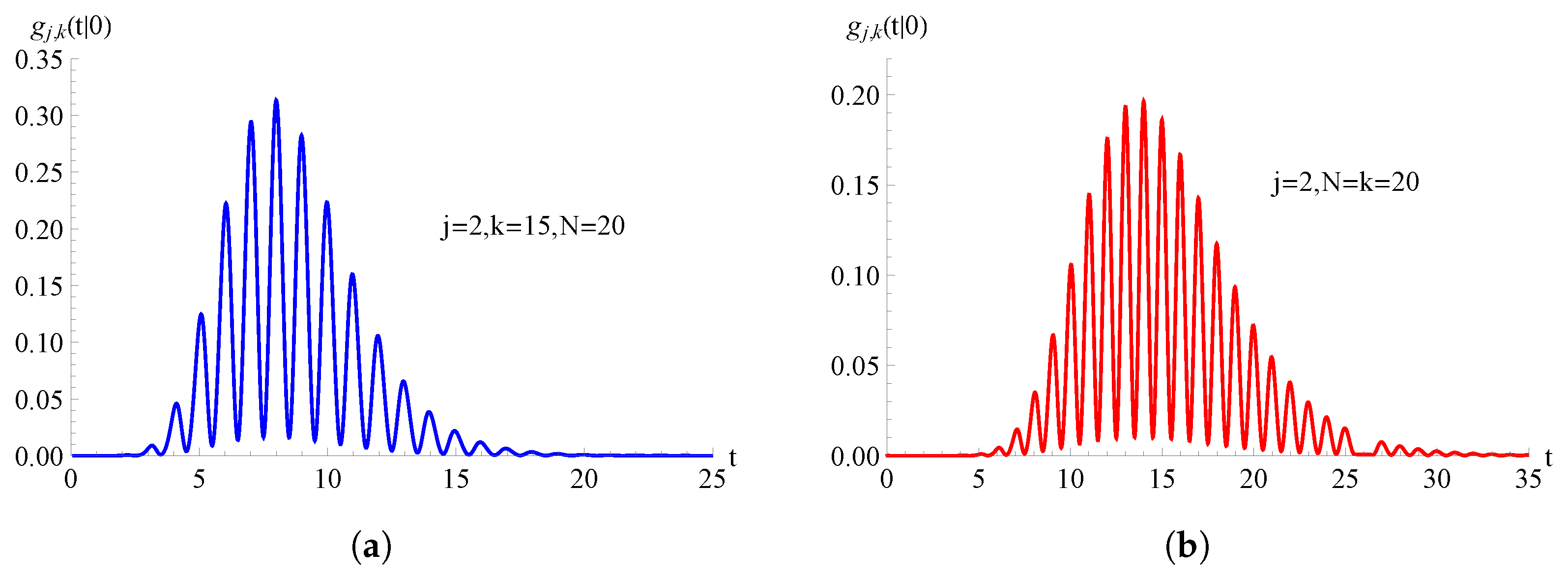

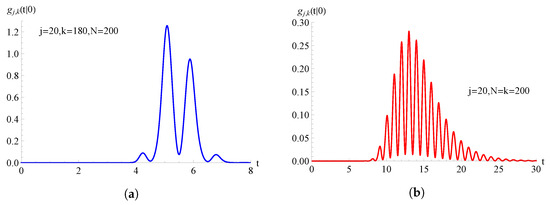

In Figure 5, we consider the TNH-binomial birth process having , with ; the FPT pdf , given in (50), is plotted as a function of t for , , and for on the left and on the right.

Figure 5.

For the TNH-binomial birth process with , the FPT pdf is plotted as a function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

Remarks on the FPT Mean and Variance for the TH-Binomial Birth Process

For the TH-binomial birth process, with and , substituting into (36), one has the following:

In Table 4, the mean , the variance , and the coefficient of variation of the FPT for the TH-binomial process are listed for , , , and for some choices of k. As shown in Table 4, the average time required for the entire population to become infected is .

Table 4.

For the TH-binomial birth process, with , the mean, the variance, and the coefficient of variation of the FPT are listed for , , , and for different values of k.

For the TH-binomial birth process, now we are interested in the behavior of the mean and the variance of for large population size. For this purpose, we denote by

the generalized harmonic numbers and we assume that for . In particular, by setting in (52), one obtains the harmonic numbers .

For large population size, and can be approximated using the following identities:

where is the Euler–Mascheroni constant and denotes the Riemann zeta function (cf. Abramowitz and Stegun [30], p. 807). Hence, recalling (51) and using (53), for large population size, the following approximations hold:

being . We note that, for the TH-binomial birth process, admits a finite limit as :

In Table 5, the deterministic time , given in (5) with , the mean , the mean , and the variance , given in (51), and the asymptotic behaviors and , given in (54), are listed for , , and for increasing values of N. We observe a sufficient agreement between the values of , obtained via the deterministic binomial model, and the values of , derived using the stochastic binomial birth process. Furthermore, a good agreement exists between the exact values of the FPT means and variances and their approximate values as N increases.

Table 5.

For the TH-binomial birth process, with , the deterministic time , given in (5) with , the mean of , the mean and the variance of , and their asymptotic behaviors are listed for , , and for different values of N.

4.2. Quadratic Birth Process

Let be a TNH-quadratic birth process having birth intensity functions for . In this case, in (18) we set .

Proposition 5.

For the TNH-quadratic birth process , one has the following:

Proof.

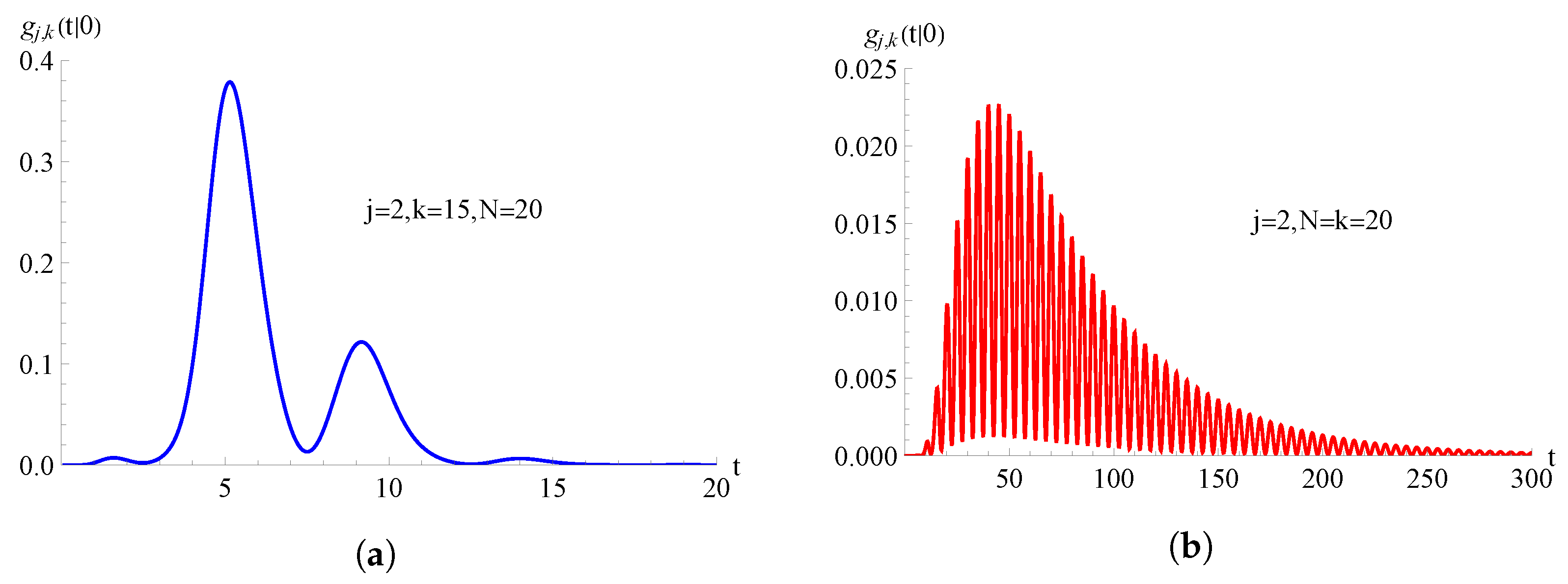

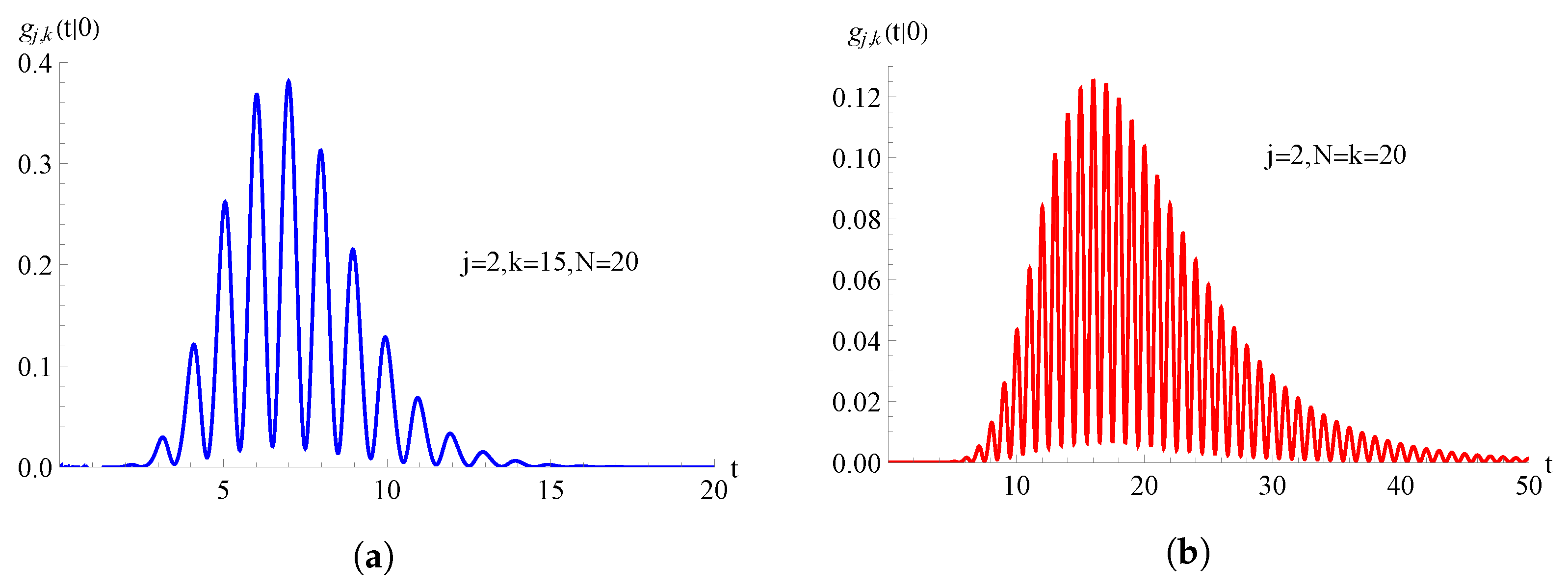

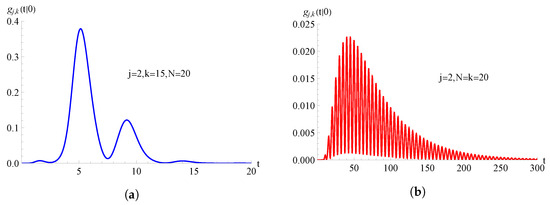

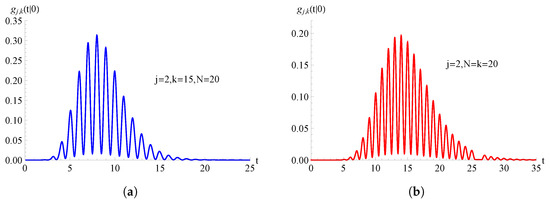

In Figure 6, we consider the TNH-quadratic birth process with , with ; the FPT pdf , given in (58), is plotted as a function of t for , , and for on the left and on the right.

Figure 6.

For the TNH-quadratic birth process with , with , the FPT pdf is plotted as function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

Remarks on the FPT Mean and Variance for TH-Quadratic Birth Process

For the TH-quadratic birth process, with and , substituting into (36), one has

In Table 6, the mean , the variance , and the coefficient of variation of the FPT for the TH-quadratic birth process are listed for , , , and for some choices of k. As shown in Table 6, the average time required for the entire population to become infected is .

Table 6.

For the TH-quadratic birth process, with , the mean, the variance, and the coefficient of variation of the FPT are listed for , , , and for different values of k.

By comparing the results of Table 4 and Table 6, we note that the averages and the variances of the FPT for the TH-quadratic birth process are greater than those obtained for the TH-binomial birth process.

For the TH-quadratic birth process, we now take into account the behavior of the mean and the variance of for large values of N. Recalling (59), for large population size, the following approximations hold:

where (53) has been used with and . Differently from the binomial birth process, for the quadratic birth process, the variance does not admit a finite limit and N increases.

In Table 7, the deterministic time , given in (5) with and , the mean , the mean , and the variance , given in (59), and the asymptotic behaviors and , given in (60), are listed for , , and for increasing values of N. We observe a substantial discrepancy between the values of , obtained via the deterministic quadratic model, and the values of , derived using the stochastic quadratic birth process. Instead, an excellent agreement exists between the exact values of the FPT means and variances and their approximate values as N increases.

Table 7.

For the TH-quadratic birth process, with , the deterministic time , given in (5) with and , the mean of , the mean and the variance of , and their asymptotic behaviors are listed for , . and for different values of N.

4.3. SI Birth Process

Let be a TNH-SI birth process with birth intensity functions for . In this case, in (18), we set . The TH-SI birth process, with , is considered in studies by Allen [5] and Bailey [1,8,31]. The TNH-SI birth process, with and total population size , is also taken in account in the study of Yang and Chiang [32,33].

For the SI birth process, considerable efforts are required to obtain general expressions of the transition probabilities and of the FPT densities . In particular, for the TH-SI birth process, in which and , it is necessary to determine the inverse LT of (23), that is

where, due to (31),

is a polynomial in s of degree , that depends on j, n, and N. For fixed j, n, and N, the roots of (62) can all be different or some of them are repeated twice. We remark that two roots and , with and , are equal if and only if . In the sequel, if the root of polynomial (62) is of single multiplicity, we define the coefficient

whereas, if is of multiplicity two, we consider the coefficients:

To determine the inverse LT of (61), we distinguish two cases: and .

4.3.1. Case

Proposition 6.

For the TNH-SI birth process , the following results hold:

- For one has the following:

- For , the result is as follows:

Proof.

We assume that . For , , one has , so that . Hence, the roots of polynomial (62) are all distinct for . The assumptions of Proposition 1 are satisfied, with .

Under the assumptions of Proposition 6, by virtue of (33), the FPT pdf of the TNH-SI birth process can be obtained. Indeed, from (65), for and one has the following:

whereas for and one obtains the following:

In Figure 7, we consider the TNH-SI birth process with . In Figure 7a, the FPT pdf , given in (70), is plotted as a function of t for , with , , and . Instead, in Figure 7b, the FPT pdf , given in (71), is plotted as a function of t for , with , , and .

Figure 7.

For the TNH-SI birth process with , the FPT pdf is plotted as a function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

4.3.2. Case

Let j, n, and N be fixed values, with . When , it is necessary to distinguish the following cases:

- and (see Proposition 7);

- , and is odd (see Proposition 8);

- , and is even (see Proposition 9).

Proposition 7.

Let j, n, and N be fixed values, with and . For the TNH-SI birth process, the result is as follows:

- If , one has the following:

- If , one obtains the following:

Proof.

When j, n, and N are fixed values, with and , all the roots of the polynomial (62) have single multiplicity. Indeed, for each pair of distinct roots, and , of (62), it results in , so that . From (63), for one has the following:

whereas for one obtains the following:

Hence, taking the inverse LT of (61), for j, n, and N fixed, with and , one obtains

so that, by virtue of (21), Equations (72) and (73) follow. □

Note that (72) is in agreement with the result in the study of Yang and Chiang [32] for , , when the total population size is equal to and .

Under the assumptions of Proposition 7, recalling (33), the FPT pdf of the TNH-SI birth process can be obtained in the case and . Indeed, by virtue of (72), and one has the following:

whereas, for and , by using (73), one obtains the following:

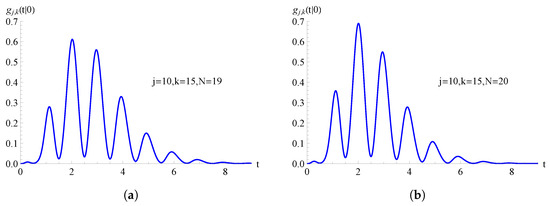

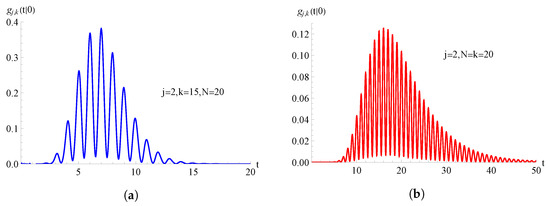

In Figure 8, we consider the TNH-SI birth process with . In Figure 8a, the FPT pdf , given in (74), is plotted as a function of t for , , and . Instead, in Figure 8b, the FPT pdf , given in (75), is plotted as a function of t for , , and .

Figure 8.

For the TNH-SI birth process with , the FPT pdf is plotted as function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

Proposition 8.

Proof.

Let and N be fixed values, with , , and odd. The polynomial (62) has roots of multiplicity two and one root of single multiplicity. From (62), one has the following:

We note that, if , one has for . Instead, , it results in for . Moreover, if , we have for . Therefore, recalling (77) and making use of Proposition 2, Equation (76) follows. □

Proposition 9.

Proof.

Let , , and even. The cardinality of and of is . If , in the polynomial (62) there are roots of multiplicity two and two roots of single multiplicity. Instead, if , the roots of polynomial (62) all have multiplicity two. Indeed, in a fixed root , with , there always exists another equal root with , being . From (62), one has the following:

with and defined in (79). Therefore, recalling (80) and making use of Proposition 2, Equation (78) follows. □

We remark that, due to (61), for the TH-SI birth process, the following function in Mathematica

immediately gives the symbolic inverse LT of , with .

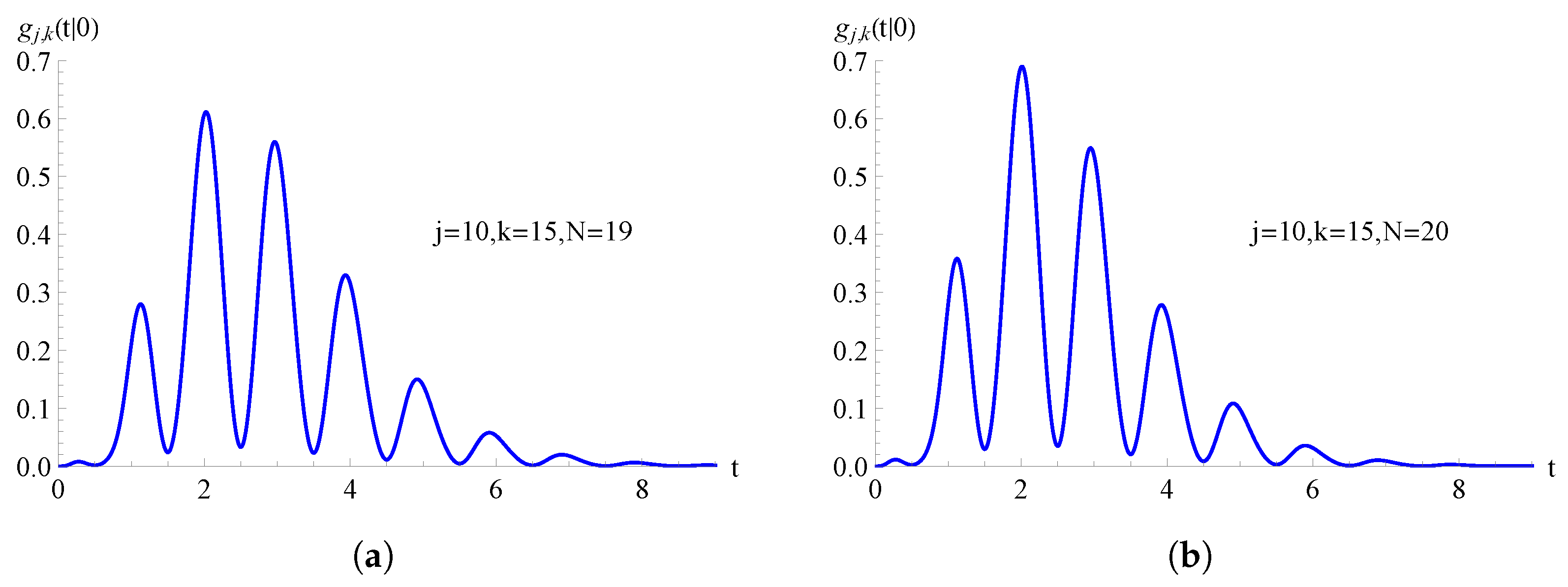

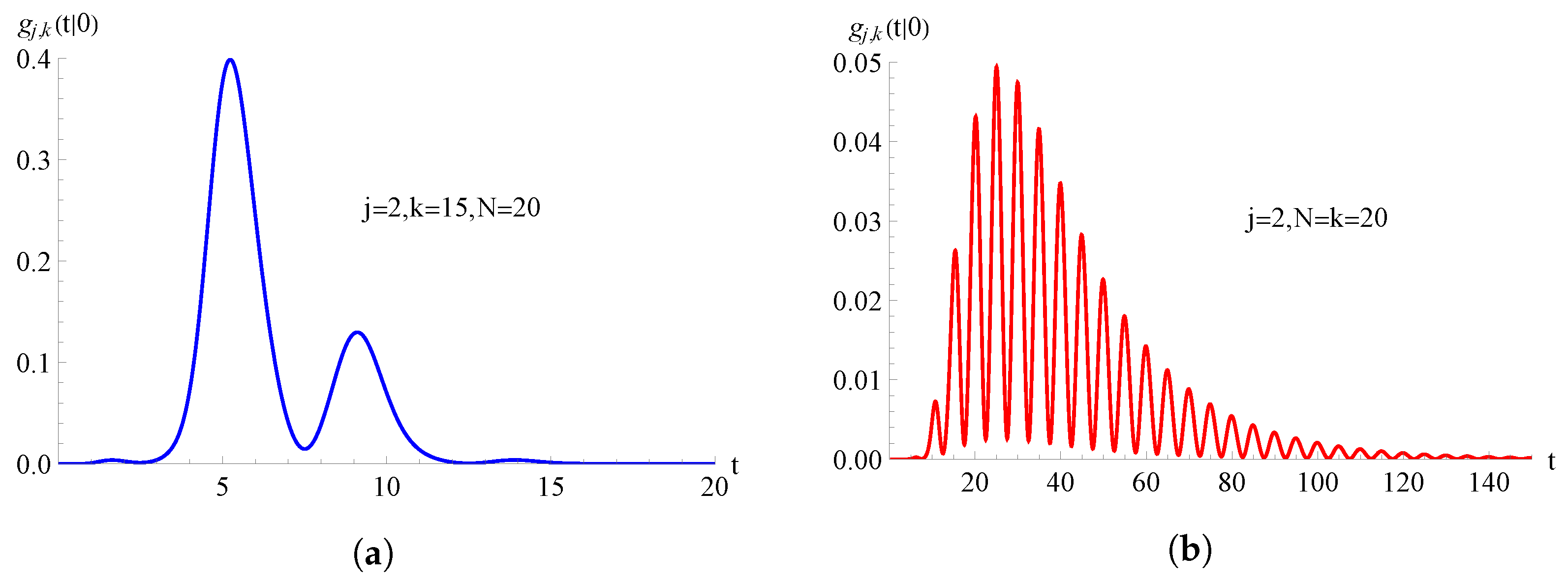

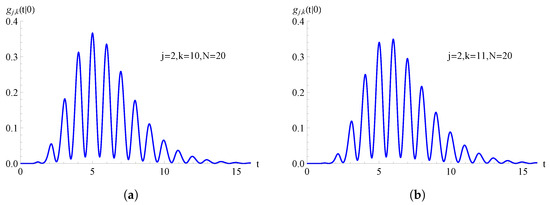

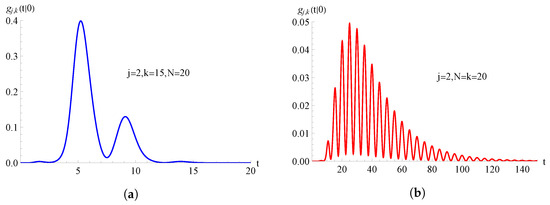

For the TNH-SI birth process with , in Figure 9 we plot the FPT pdf as a function of t for , , and . In these cases, the probabilities have been obtained making use of relation (21) and of the inverse LT of Mathematica.

Figure 9.

For the TNH-SI birth process with , the FPT pdf is plotted as function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

Remarks on the FPT Mean and Variance for the TH-SI Birth Process

For the TH-SI birth process, with and , substituting into (36), one has

In Table 8, the mean , the variance , and the coefficient of variation of the FPT for the TH-SI birth process are listed for , , , and for some choices of k. As shown in Table 8, the average time required for the entire population to become infected is .

Table 8.

For the TH-SI birth process, with , the mean, the variance, and the coefficient of variation of the FPT are listed for , , , and for different values of k.

For the TH-SI birth process, we consider the behavior of the mean and the variance of for large population size. By virtue of (81), for large N, the following approximations hold:

where (53) has been used with . Similarly to the binomial birth process, the variance of has a finite limit for :

In Table 9, the deterministic time , given in (5) with and , the mean , the mean , and the variance , given in (81), and their asymptotic behaviors and , given in (82), are listed for , , and for increasing values of N. As for the binomial birth process, we observe a sufficient agreement between the values of , obtained via the deterministic SI model, and the values of , derived using the stochastic SI birth process. Furthermore, a good agreement exists between the exact values of the FPT means and variances and their approximate values as N increases.

Table 9.

For the TH-SI birth process, with , the deterministic time , given in (5) with and , the mean of , the mean and the variance of , and their asymptotic behaviors are listed for , , and for different values of N.

5. Stochastic Hyper-Logistic Birth Process

Let be a TNH-hyper-logistic birth process, having birth intensity functions , with and . In this case, in (18), we set . Note that the hyper-logistic birth process identifies with the SI birth process when and it becomes the quadratic birth process by setting . Hence, in the sequel, we assume that .

Proposition 10.

For the TNH-hyper-logistic birth process , with , one has the following:

Proof.

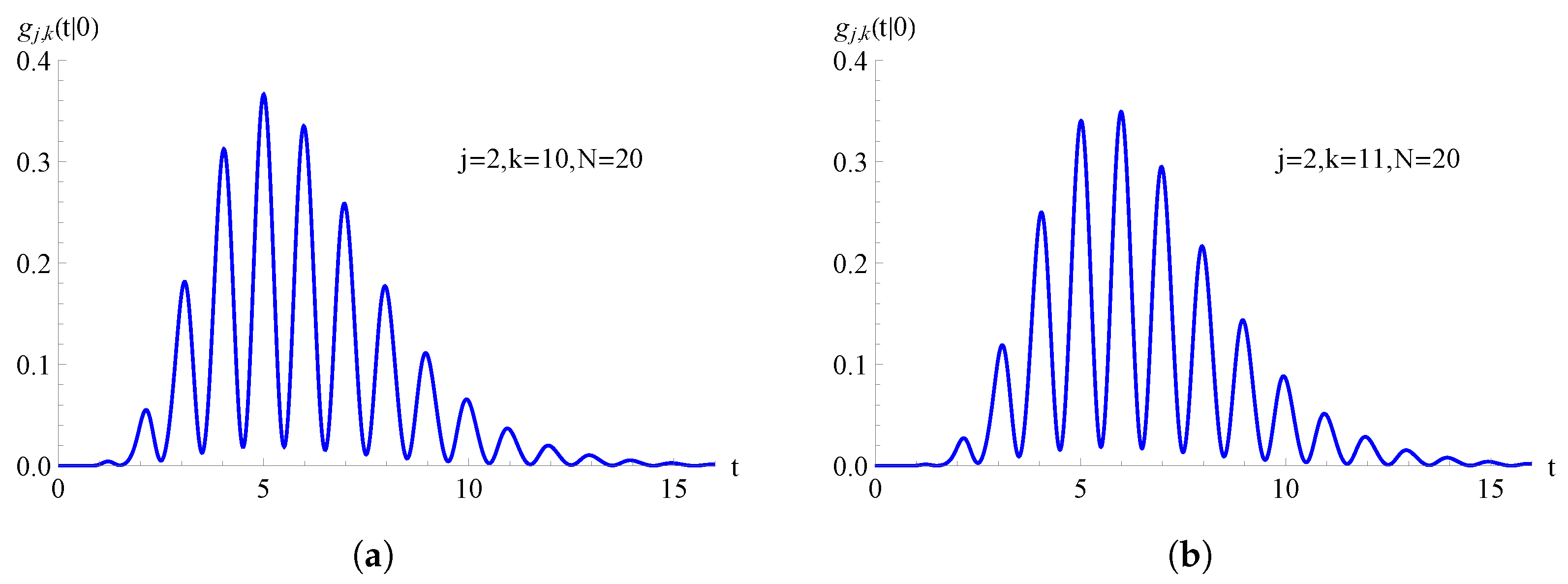

In Figure 10, we consider the TNH-hyper-logistic birth process with and , with ; the FPT pdf , given in (84), is plotted as function of t for , , and for on the left and on the right.

Figure 10.

For the TNH-hyper-logistic birth process with and , the FPT pdf is plotted as function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

In Figure 11, we consider the TNH-hyper-logistic birth process with and , with ; the FPT pdf , given in (84), is plotted as a function of t for , , and for on the left and on the right.

Figure 11.

For the TNH-hyper-logistic birth process with , , with , the FPT pdf is plotted as function of t for and . In (a) and in (b) .

Remarks on the FPT Mean and Variance for the TH-Hyper-Logistic Birth Process

For the TH-hyper-logistic birth process, with and , substituting into (36), for one has the following:

In Table 10, the mean , the variance , and the coefficient of variation of the FPT for the TH-hyper-logistic birth process are listed for , , , and for different values of k, with (on the left) and (on the right). As shown in Table 10, the average time required for the entire population to become infected is if and when .

Table 10.

For the TH-hyper-logistic birth process, with the mean, the variance, and the coefficient of variation of the FPT are listed for , , , and for different values of p and k.

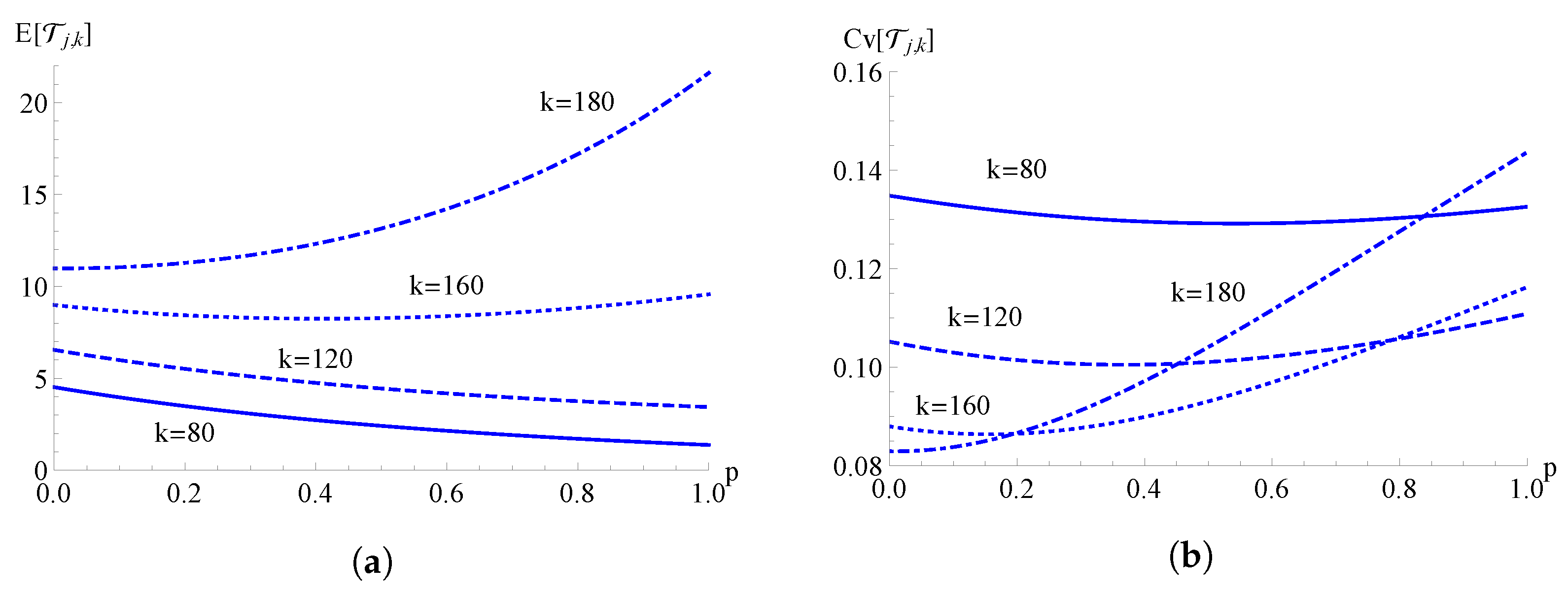

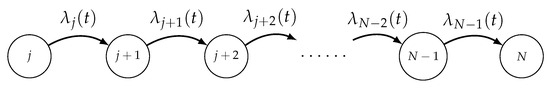

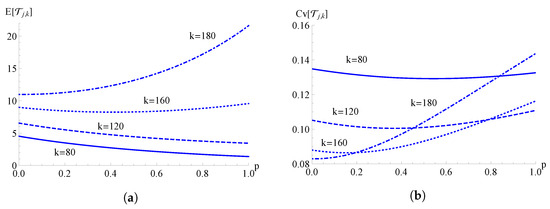

In Figure 12, the mean and the coefficient of variation of the FPT for the TH-hyper-logistic birth process are plotted as functions of for , , , and for different values of k. We note that the behavior of the FPT mean and of the FPT coefficient of variation as a function of p depends on .

Figure 12.

For the TH-hyper-logistic birth process, the mean in (a) and the coefficient of variation in (b) of the FPT are plotted as functions of for , , , and for different values of k.

In Table 11, the deterministic time , given in (16), the mean and the mean , given in (85), are listed for , , and for increasing values of N, with (on the left) and (on the right). We note that, as shown for the TH-binomial, in the TH-quadratic and TH-SI process, even for the TH-hyper-logistic birth processes, the deterministic time is always included in the interval .

Table 11.

For the TH-hyper-logistic birth process, the deterministic time , given in (16), the mean of and of are listed for , , and for different values of p and N.

6. Results and Discussion

In this paper, we have considered a finite population of total size N in which an individual can be in one of two states, either susceptible (S) or infectious (I). Specifically, we have described the growth of the infected population, making use of deterministic dynamics via stochastic birth processes. In the deterministic epidemic models with two states, we have introduced the transmission intensity function and an interaction term of the form , where the dependence on the number of infected individuals occurs via a linear or nonlinear bounded function . In the flexible model , with , , . Special cases of the flexible model are the binomial model , the quadratic model , and the SI model . The SI model leads to the Verhulst logistic growth curve for . Instead, in the hyper-logistic model , with . In general, the intensity function , the parameters and in the flexible model, and the parameter p in the hyper-logistic model must be estimated by using real data related to the infection under consideration. We have analyzed the following TNH deterministic models and the corresponding stochastic finite birth processes: flexible, binomial, quadratic, SI, and hyper-logistic. We have determined the probability distribution of the number of infected individuals as a function of time, the expected duration until the infected population size reaches N, and we have obtained some asymptotic approximations for large values of N.

The study, carried out on deterministic and stochastic models, highlighted the following results:

- In the deterministic model, if , at the end, all individuals of the population are infected, i.e., . In the stochastic finite birth process, describing the infected population, the state N is an absorbing boundary, so that if the process reaches the absorbing state in finite mean time.

- For the finite birth processes , we have determined the transition probabilities since their knowledge allows us to obtain the FPT densities and related moments.

- For the binomial birth process, the conditional mean identifies with the deterministic solution of the deterministic binomial birth model.

- For the flexible birth process, we have proved that for large N, with .

- In the TH-deterministic model, we have calculated the duration required until individuals of a population are infected. Such parameters have been compared with the FPT averages and of the related finite birth process. Numerical computations have shown that the deterministic time is always included in the interval . We have observed a substantial discrepancy between the values of of the deterministic quadratic model and the average values in the quadratic birth process.

- For the TH-binomial, TH-quadratic, and TH-SI birth processes, we have obtained some asymptotic behaviors of the mean and variance of for large N. Specifically, for large N one has the following:

- -

- For the TH-binomial birth process, grows as , whereas the admits a finite limit as N increases;

- -

- For the TH-quadratic birth process, grows linearly with N, whereas the grows quadratically with N;

- -

- For the TH-SI birth process, grows as and the admits a finite limit as N increases.

- For the TH-hyper-logistic birth process, we have studied the behavior of the mean and coefficient of variation of FPT as functions of for various choices of the state k, with ; for k near to the initial state j, is a decreasing function of p, whereas for k near to N the mean, is an increasing function of p.

The results obtained can help in choosing a suitable model to study real data and make predictions on the possible developments of the epidemics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and A.G.N.; methodology, V.G. and A.G.N.; validation, V.G. and A.G.N.; formal analysis, V.G. and A.G.N.; investigation, V.G. and A.G.N.; supervision, V.G. and A.G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is partially supported by PRIN 2022, the project “Anomalous Phenomena on Regular and Irregular Domains: Approximating Complexity for the Applied Sciences”, and PRIN 2022 PNRR, the project “Stochastic Models in Biomathematics and Applications”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are members of the research group GNCS of INdAM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FPT | First-passage time |

| TNH | Time inhomogeneous |

| TH | Time homogeneous |

| LT | Laplace transform |

| Probability density function | |

| PGF | Probability generating function |

| CGF | Cumulant generating function |

References

- Bailey, N.T.J. The Elements of Stochastic Processes with Applications to the Natural Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bharucha-Reid, A.T. Elements of the Theory of Markov Processes and Their Applications; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.R.; Miller, H.D. The Theory of Stochastic Processes; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H.M.; Karlin, S. An Introduction to Stochastic Modeling; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.J.S. An Introduction to Stochastic Processes with Applications to Biology; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.J.S. Stochastic Population and Epidemic Models. Persistence and Extinction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dailey, D.J.; Gani, J. Epidemic Modelling: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N.T.J. The Mathematical Theory of Epidemics; Charles Griffin and Co. Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Anggriani, N.; Panigoro, H.S.; Rahmi, E.; Peter, O.J.; Jose, S.A. A predator-prey model with additive Allee effect and intraspecific competition on predator involving Atangana-Balenu-Caputo derivative. Results Physic 2023, 49, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.; Ramachandran, R.; Alzabut, J.; Jose, S.A.; Khan, H. A fractional-order density-dependent mathematical model to find the better strain of Wolbachia. Symmetry 2023, 15, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.A.; Raja, R.; Dianavinnarasi, J.; Baleanu, D.; Jirawattanapanit, A. Mathematical modeling of chickenpox in Phuket: Efficacy of precautionary measures and bifurcation analysis. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 84, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.A.; Raja, R.; Omede, B.I.; Agarwal, R.P.; Alzabut, J.; Cao, J.; Balas, V.E. Mathematical modeling on co-infection: Transmission dynamics of Zika virus and Dengue fever. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 4879–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, V.; Muller, E.; Bass, F.M. New product diffusion models in marketing: A review and direction for research. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidolin, M.; Manfredi, P. Innovation Diffusion Processes: Concepts, Models, and Predictions. Annu. Rev. Stat. Its Appl. 2023, 10, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, G. Analysis on a diffusive SI epidemic model with logistic source and saturation infection mechanism. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2022, 45, 1111–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.E.; Bradley, E.L.; Kirk, K.A.; Pruitt, K.M. A theory of growth. Math. Biosci. 1976, 29, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelov, R.; Kyurkchiev, N.; Markov, S. Some properties of the Blumberg’s hyper-log-logistic curve. BioMath 2018, 7, 1807317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, G.; Giorno, V.; Román-Román, P.; Torrez-Ruiz, F. Study of a general growth model. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 107, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, A.A. Logistic growth rate functions. J. Theor. Biol. 1968, 21, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, J.L.; Aleixo, S.M. Dynamical analysis in growth models: Blumberg’s equation. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst.-Ser. B 2013, 18, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faddy, M.J.; Fenlon, J.S. Stochastic modelling of the invasion process of nematodes in fly larvae. Appl. Statist. 1999, 48, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrec, L.; Bank, C.; Bertrand, T. Solving the stochastic dynamics of population growth. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, E10295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdèlyi, A.; Magnus, W.; Oberthettinger, F.; Tricomi, F.G. Tables of Integral Transforms; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1954; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Giorno, V.; Nobile, A.G. First-passage times and related moments for continuous-time birth-death chains. Ric. Di Mat. 2019, 68, 629–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorno, V.; Nobile, A.G. On some integral equations for the evaluation of first-passage-time densities of time-inhomogeneous birth-death processes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 422, 126993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorno, V.; Negri, C.; Nobile, A.G. A solvable model for a finite-capacity queueing system. J. Appl. Probab. 1985, 22, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q. Note on the non-homogeneous Prendiville process. Math. Biosci. 1998, 148, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorno, V.; Nobile, A.G. A time-inhomogeneous Prendiville model with failures and repairs. Mathematics 2022, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usov, I.; Satin, Y.; Zeifman, A.; Korolev, V. Ergodicity bounds and limiting characteristics for a modified Prendiville model. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1972.

- Bailey, N.T.J. The simple stochastic epidemic: A complete solution in terms of known functions. Biometrika 1963, 50, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.L.; Chiang, C.L. A time dependent simple stochastic epidemic. In Proceedings of the Sixth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Vol IV: Biology and Health; Le Cam, L.M., Neyman,, J., Scott,, E.L., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Chiang, C.L. On Interarrival times in simple stochastic epidemic models. J. Appl. Probab. 1982, 19, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).