Abstract

The reliability of large-scale networks can be compromised by various factors such as natural disasters, human-induced incidents such as hacker attacks, bomb attacks, or even meteorite impacts, which can lead to failures in scope of processors or links. Therefore, ensuring fault tolerance in the interconnection network is vital to maintaining system reliability. The n-dimensional folded hypercube network structure, denoted as , is constructed by adding an edge between every pair of vertices with complementary addresses from an n-dimensional hypercube, . Notably, exhibits distinct characteristics based on the dimensionality: it is bipartite for odd integers and non-bipartite for even integers . Recently, in terms of the issue of how performs in communication under regional or widespread destruction, we mentioned that in , even when a pair of adjacent vertices encounter errors, any fault-free edge can still be embedded in cycles of various lengths. Additionally, even when the smallest communication ring experiences errors, it is still possible to embed cycles of any length. The smallest communication ring in is observed to be the four-cycle ring. In order to further investigate the communication capabilities of , we further discuss whether every fault-free edge will still be a part of every communication ring with different lengths when the smallest communication ring is compromised in . In this study, we consider a fault-free edge and as the set of faulty extreme vertices for any four cycles in . Our research focuses on investigating the cycle-embedding properties in , where the fault-free edges play a significant role. The following properties are demonstrated: (1) For in , every even length cycle with a length ranging from contains a fault-free edge e; (2) For every even in , every odd length cycle with a length ranging from contains a fault-free edge . These findings provide insights into the cycle-embedding capabilities of , specifically in the context of fault tolerance when considering certain sets of faulty vertices.

MSC:

05C38

1. Introduction

In multiprocessor systems, processors communicate with each other through an interconnection network. A wide variety of network topologies have been proposed, among which the n-dimensional hypercube stands out due to its symmetry, recursive structure, regularity, strong connectivity, small diameter, low degree, and low edge complexity [1]. Currently, many transformed or expanded topological structures of have been developed for research and exploration. The reason is that these topologies possess numerous excellent characteristics, such as regularity, symmetry, low degree, and a graph diameter that is almost only half of that of a hypercube. Therefore, each of them has its own research value. However, among the various topological structures with variations of , folded hypercubes contain complement edges, which are obtained by adding an edge to each pair of vertices that are farthest apart in . Since have more edges than , can not be classified as hypercube-like structures and can not develop the generally fault-tolerant Hamiltonian property. Therefore, serve as the network topology for our study. Moreover, has been shown to improve the performance of in multiple measurements [2]. Additionally, are distinguished from other recursive and bipartite graph structures. The uniqueness of lies in the fact that when their dimensions are odd, they are bipartite graphs, while they are not bipartite in even dimensions. Therefore, when investigating cycle embeddings, it is often necessary to separately consider odd-dimensional and even-dimensional aspects. Based on these superiorities make widely used in parallel computing systems.

In real-world networks, faults in edges and/or vertices are inevitable. Therefore, the evaluation of fault-tolerant problems in has been widely studied in the literature [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Recently, the issue of how performs in communication under adverse conditions such as natural disasters or human-inflicted damage, which can result in regional or widespread destruction, including earthquakes, meteorite impacts, or bombings, has been raised. For example, in our previous works, we mentioned that in , even when a pair of adjacent vertices encounter errors, any fault-free edge can still be embedded in cycles of various lengths [10]. Additionally, even when the smallest communication ring experiences errors, it is still possible to embed cycles of any length [9]. The smallest communication ring in is observed to be the four-cycle ring. In order to further investigate the communication capabilities of , we further discuss whether every fault-free edge will still be a part of every communication ring with different lengths when the smallest communication ring is compromised in . This paper addresses this question by studying fault-free edges and the scope faulty set of faulty extreme vertices of any four-cycle ring in . The main results obtained are: (1) for , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of every even length from 4 to in ; (2) for every even , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of every odd length from to in .

2. Preliminaries

The graph terminology used in this paper is based on the definitions provided in [11] when utilizing a graph to model the network. Let us take into account a graph which is finite, where and denote the sets of vertices and edges of , respectively.

Consider a graph with sets and representing faulty edges and faulty vertices, respectively. Here, is a subset of and is a subset of . The subgraph obtained after removing and from is denoted by . Typically, removing a set of vertices also means removing all edges connected to the set of vertices. A path is a sequence of adjacent vertices where each vertex is distinct. The path may include a subpath, represented as , where . The length of the path is denoted as , which is equivalent to the number of edges in . A cycle in is a sequence of vertices where , and all vertices are distinct. Additionally, any two consecutive vertices in the cycle are adjacent.

Consider the graph , where n is a positive integer. This graph has vertices, each of which is labeled with an n-bit binary string, ranging from to n, denoted as where is either 0 or 1 and . The edges of connect vertices that differ in exactly one bit position. In other words, an edge exists if and only if and have different labels in exactly one position , where , and is obtained from by flipping the bit in position . We call this edge an edge of dimension edges, so the total number of edges is .

Given two vertices and , we define the Hamming distance as the number of positions where their corresponding binary strings differ. We also define the complement of a vertex , denoted by , as the vertex obtained by flipping all bits in . Finally, we define the operation as the vertex obtained from u by flipping the -th bit of . In other words, if , then for all and , and .

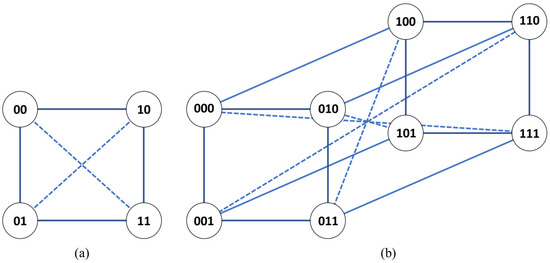

is an extension of where every pair of vertices that have the maximum distance between them in are connected by a complementary edge. As a result, has complementary edges denoted by the set . The set of regular edges in that belong to are denoted by . Specifically, is the union of i-dimensional edge sets for , that is . Therefore, the set of edges in is given by which contains all the edges such that or . Figure 1 illustrates instances of and .

Figure 1.

Graphs (a) and (b) , complementary edge set is depicted as dashed lines.

Given a regular hypercube , we can divide it into two subcubes along dimension i, where . These subcubes are denoted as and , where the i-th bit of vertices in and are 0 and 1 respectively. To simplify notation, we can denote and as and respectively.

Definition 1 ([12]).

A partition of into two subcubes, and , along a specific dimension i is called an i-partition, where . Furthermore, all complementary edges in connect a vertex in to a vertex in . To simplify, we use and as brief notations for and , respectively.

According to Definition 1, we can partition the set of faulty vertices in into two subsets by executing an i-partition. This partition results in the formation of two -cubes, denoted as and . We can then define the subsets of within each -cubes as for . Finally, we can use to represent the cardinality of for each .

For the rest of this section, we will examine certain outcomes that have been documented in or , and which are beneficial to our primary argument.

Lemma 1 ([7]).

Assuming , it can be shown that for , any fault-free edge in can lie on a cycle of even length l within the range of . Similarly, for every even and , every fault-free edge in can also be a part of a cycle of odd length l within the range of .

The subsequent corollary can be obtained directly by referring to Lemma 1.

Corollary 1.

Suppose . Then, for , any fault-free edge in can lie on a cycle with any even length l satisfying . Additionally, for every even , any fault-free edge in an also be a part of a cycle with any odd length l satisfying .

Lemma 2 ([9]).

Consider , where and let and represent two adjacent faulty vertices. It is possible to find a path of length within , where x and y are fault-free vertices belonging to the same partite set.

Lemma 3 ([13]).

Let represent faulty vertices and faulty edges in . For any two fault-free vertices x and y in , with and , there exists a fault-free path with length l such that , provided is divisible by 2.

Lemma 4 ([14]).

For any two vertices x and y in , where , there is a path of length l, where . Moreover, the difference is always a multiple of 2.

Lemma 5.

Suppose

and

are two adjacent faulty vertices in

, where

. Then, for any fault-free edge

, it is possible for e to be a part of a cycle of length

in

.

Proof.

We will prove the lemma by using mathematical induction on n. Let us consider the base case, where . has a symmetric structure, thus we can assume without any loss of generality that and . In Table 1, every fault-free edge can be obtained in at least one of these cycles of length 14. The lemma is verified for . Assuming that the lemma holds for all integers where , where , we aim to demonstrate that it also holds for . We consider the case where and are adjacent in . Without loss of generality, we may assume that . Then, we can partition into two subcubes and along dimension i, where , such that or . We can make the assumption that and , without it affecting the general nature of the argument. Given that be any fault-free edge in , then we have the following subcases. □

Table 1.

Lemma 5 is being applied to the base case where n = 4.

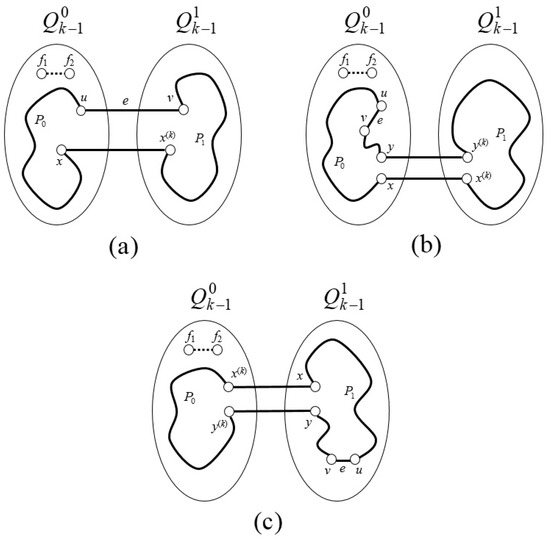

- Case 1. and are in different subcubes. Assuming and , we can make the following argument without losing generality. Let be a neighbor of in that is free of faults and is not one of or . (Note that since , must have more than four neighbors in .) By the induction hypothesis, can lie on a fault-free cycle of length in , which can be represented as . Observe that is the neighbor of in , and . As per Lemma 4, there is a path of length in . Consequently, the cycle comprising of the sequence has a length of , and it contains the edge in (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. The proof of Case 1 (a) Case 2 (b) and Case 3 (c) in Lemma 5 are illustrated.

Figure 2. The proof of Case 1 (a) Case 2 (b) and Case 3 (c) in Lemma 5 are illustrated. - Case 2. and both are in . Using the induction hypothesis, we assume that edge belongs to a fault-free cycle in with length . We consider another edge in and express as . Since and belong to and their Hamming distance is 1, Lemma 4 implies there exists a path with length in . Therefore, the cycle has length and includes edge in (Figure 2b).

- Case 3. and both are in . Given in , by Lemma 4, we know that there exists a path of length in . Since , the length of is more than 15 in , so there must exist an edge in such that in . Since in , by induction hypothesis, can lie on a fault-free cycle of length in . We can express as . Now, we can express as . Therefore, the cycle has length and includes edge in (Figure 2c).

We have completed the proof by combining the above cases. Thus, we have shown that the lemma holds for . Q.E.D.

3. Every Cycle of Contains Any Edge

Let us assume that is an edge free from faults, and define the set as the collection of faulty extreme vertices, denoted by and , that belong to any four-cycle ring in . In this section, we will demonstrate the following results regarding in : (1) For , can lie on a cycle of any even length between 4 and , inclusive; (2) For every even , can lie on a cycle of any odd length between and , inclusive.

Lemma 6.

When , any edge that is free of faults can lie on a cycle of even length l with in . The set represents the scope of faulty vertices at the extreme ends of any four-cycle ring in .

Proof.

The scenarios are evaluated separately for three cases of n: , , and . □

- Case 1. For . Since the structure of is symmetric. Without loss of generality, the scope faulty four-cycle F4 can be categorized into two types: those that do not contain complement edges and those that contain complement edges . With this assumption, we can observe that every fault-free edge in Table 2 and Table 3 can be found in at least one even cycle with a length between 4 to 12 in and , respectively. Hence, the case satisfies the lemma.

Table 2. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 6, where .

Table 2. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 6, where . Table 3. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 6, where .

Table 3. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 6, where . - Case 2. For . Assuming the symmetry of the structure of , we can, without loss of generality, consider as either or . By using Definition 1, we can apply the 2-partition on to generate two 4-dimensional subcubes, and , such that and . For any fault-free edge in , we can investigate its distribution using the following scenarios.

- Case 2.1. or . Assuming no loss of generality, we can consider . In this case, we need to account for the fact that can be found in every even cycle of length l with in . Consequently, the following subcases emerge.

- Case 2.1.1. Even length l with . By Lemma 3, since and , there exists a fault-free path of every odd length 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 in , respectively. Thus, can form the cycle of every even length l with which obtains the edge in . Without loss of generality, we may select a cycle with length 12 and let be any edge in such that in . Then, can be expressed as . Since is fault-free in , forms a cycle of even leng which obtains the edge in . Note that , and in . By Lemma 3, there exists a fault-free path of every odd length 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 in , respectively. Then, forms a cycle of every even length l with which obtains the edge in .

- Case 2.1.2. Even length l with . Given that and are adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , by Lemma 5, can be on a cycle of length 14 in . We select an edge from such that in . Then, can be expressed as . This gives rise to the following subcases.

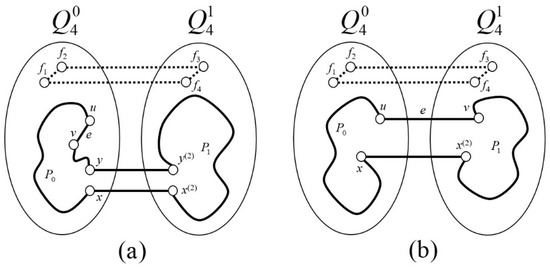

- Case 2.1.2.1. . Lemma 3 guarantees that a fault-free path of odd length 11 exists in , where . Therefore, the cycle can be expressed as , which has even length , and includes the edge in (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Figure showing the proof of subcases Case 2.1.2.1 (a) and Case 2.2.2.1 (b) in Lemma 6.

Figure 3. Figure showing the proof of subcases Case 2.1.2.1 (a) and Case 2.2.2.1 (b) in Lemma 6. - Case 2.1.2.2. . Given that and are two adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , by Lemma 5, can be on a cycle of even length 14 in . We note that can be represented as . Hence, forms a cycle of even length , which obtains the edge in .

- Case 2.2. . Assuming without loss of generality, and . We must then consider that can be obtained in any even cycle of length l with in . This gives rise to the following subcases.

- Case 2.2.1. Even length l with . Let be a fault-free neighbor of in such that in . This is possible as the neighbor of in are 4 vertices and at most one of them belongs to or , by the hypercube structure. Therefore, there exists at least one vertex that meets this condition. Without loss of generality, assume and . Note that and in and , respectively. Thus, forms a cycle of even length that contains the edge in . Moreover, since and , by Lemma 3, there exists a fault-free path of every odd length 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 in , respectively. Therefore, can form the cycle of every even length l with that contains the edge in . To construct every cycle of even length l with , we select a path with length 11 in . Then, in , since and , by Lemma 3, there exists a fault-free path of every odd length 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 in , respectively. Therefore, forms a cycle of every even length l with that contains the edge in .

- Case 2.2.2. Even length l with . Given that and are two adjacent faulty vertices and is an edge without faults in , according to Lemma 5, can exist on a cycle that has a length of 14 in after removing vertices and . The cycle can be expressed as . Based on this, the following subcases arise.

- Case 2.2.2.1. . Given that and , we can use Lemma 3 to conclude that there exists a fault-free path of odd length 11 in . Using this information, we can construct a cycle of even length by considering the path This cycle obtains the edge in (Figure 3b).

- Case 2.2.2.2. . According to Lemma 5, since and are two adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , the edge can lie on a cycle of even length 14 in . This cycle can be expressed as . Therefore, forms a cycle of even length that includes the edge in .

- Case 2.3. . Assuming without loss of generality, is in and is in . Next, we select a fault-free neighbor of in such that is not equal to either or in . It should be noted that the Hamming distance between and is one in , and the Hamming distance between and is one in . Using this approach, an edge can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in can be constructed similar to that in Case 2.2 of Lemma 6.

- Case 3. For . Suppose we have a fault-free edge in . Our goal is to show that can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in . Since and , by using Corollary 1, we can conclude that can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in . However, we also need to show that can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in . Here, be the set of faulty extreme vertices, taken from any four cycles in . As per Definition 1, since , the edges of the cycle are contained within two dimensions i and j, where and . As a result, a k-partition of exists such that one pair of adjacent vertices of the quadrilateral belongs to and the other pair belongs to . Here, we can select , and , without any loss of generality. After partition, we can explore the distribution of the edge and show that it can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in .

- Case 3.1. or . Let us assume without loss of generality that . Since and are two adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , we can use Lemma 5 to show that edge can lie on a cycle of length in that does not contain . We can then select any edge in such that in . Then, can be expressed as . We can then consider the following subcases.

- Case 3.1.1. . Given that and , we can use Lemma 3 to conclude that a fault-free path of odd length exists in . This path, combined with the paths and between vertices and , and vertices and respectively, can be used to form a cycle of even length . This cycle obtains the edge in . The cycle is given by .

- Case 3.1.2. . Assuming and are two adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , then by Lemma 5, we know that can lie on a cycle of even length in after removing faulty vertices and . The cycle can be expressed as . Therefore, we can conclude that is a cycle with even length . This cycle includes the edge and can be found in .

- Case 3.2. . Assuming without loss of generality, and , we can choose a fault-free neighbor of in such that in . Since and are two adjacent faulty vertices and be a fault-free edge in , by applying Lemma 5, we know that can lie on a cycle of length in after removing faulty vertices and . The cycle can be expressed as , which leads to the following subcases.

- Case 3.2.1. . Using Lemma 3, we can show that there exists a fault-free path of odd length in since and . Therefore, the cycle has an even length of and it contains the edge in .

- Case 3.2.2. . Using Lemma 5, we know that since and are adjacent faulty vertices and is a fault-free edge in , edge can lie on a cycle of even length in . We can express as . As a result, forms a cycle of even length , which obtains the edge in .

- Case 3.3. . Assuming and without loss of generality, we can choose a fault-free neighbor of in such that . In and , we have and , respectively. The process of constructing the edge lying on a cycle of every even length and in is similar to that described in Case 3.2 of Lemma 6.

The proof is completed by considering all the cases mentioned above. Q.E.D.

Lemma 7.

For every even , consider the set which consists of four faulty extreme vertices, namely , , , and , found within any four-cycle ring in . If is a fault-free edge in then can belong to a cycle of every odd length l with .

Proof.

We examine the scenarios for as well as every even . □

- Case 1. For . Since the structure of is symmetric. Without loss of generality, the scope faulty four-cycle F4 can be categorized into two types: those that do not contain complement edges and those that contain complement edges . Then, using Table 4 and Table 5, we can observe that every fault-free edge can be found in at least one cycle of odd length ranging from 5 to 11 in and , respectively. Hence, the lemma holds for the case .

Table 4. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 7, where .

Table 4. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 7, where . Table 5. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 7, where .

Table 5. The justification for Case 1 in Lemma 7, where . - Case 2. For every even . Suppose that is an edge in that is free of faults. Our goal is to show that can lie on a cycle of every odd length l such that in . Here, , , , } be the set of faulty extreme vertices, taken from any four cycles in . Note that for every even . Therefore, by Corollary 1, we know that can lie on a cycle of every odd length l with in . We also need to consider the case where can lie on a cycle of every odd length l such that in . For every even , the edges of the cycle , , , } are contained within two dimensions i and j, where and . According to Definition 1, a k-partition of exists such that one pair of adjacent vertices of the quadrilateral belongs to and the other pair belongs to . Here, we can select and . After partition, we can explore the distribution of the edge and show that it can lie on a cycle of every even length l with in .

- Case 2.1. or . It is permissible to assume that . This assumption results in the following subcases.

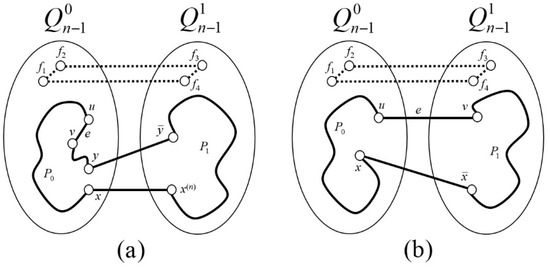

- Case 2.1.1. . According to Lemma 3, in , there exists a fault-free path of odd length in , since and . Let be an edge in such that in . Since for every even , it is not difficult to find such an edge . By Lemma 2, there exists a fault-free path of even length in , since and are two adjacent faulty vertices and in . Note that is even for every even , which means that vertices and are in the same partite set. Then, the cycle forms a cycle of odd length , which obtains the edge in (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Figure showing the proof of subcases Case 2.1.1 (a) and Case 2.2.1 (b) in Lemma 7.

Figure 4. Figure showing the proof of subcases Case 2.1.1 (a) and Case 2.2.1 (b) in Lemma 7. - Case 2.1.2. . Since is a fault-free edge in and and are two adjacent faulty vertices, Lemma 5 implies that can lie on a cycle with even length in . Let be any edge in such that in . We can express as . Since and are two adjacent faulty vertices and in , Lemma 2 implies that there exists a fault-free path of even length in . Then, the cycle has an odd length of , which contains the edge in .

- Case 2.2. . Assuming without loss of generality, we can take to be an element of and to be an element of . We can then find a neighbor of in that is free from faults and satisfies the condition in . This gives rise to the following subcases.

- Case 2.2.1. . By utilizing Lemma 3, it can be observed that a fault-free path of odd length exists in since and in . Moreover, as per Lemma 2, a fault-free path of even length exists in because and are two adjacent faulty vertices and in . Therefore, the cycle of odd length obtains the edge in (Figure 4b).

- Case 2.2.2. . Given that and are two adjacent faulty vertices, and is a fault-free edge in , we can apply Lemma 5 to conclude that can lie on a cycle of even length in . We can represent this cycle as . Note that and are two adjacent faulty vertices and in . By applying Lemma 2, we can find a fault-free path of even length in . We can then construct a cycle of odd length obtains the edge in .

- Case 2.3. . We can assume, without loss of generality, that is a vertex in and is a vertex in . Let be a fault-free neighbor of in such that in . Note that and in and , respectively. The construction of the edge lying on a cycle of odd length or in is similar to that described in Case 2.2 of Lemma 7.

The proof is completed by considering all the cases mentioned above. Q.E.D.

Applying Lemmas 6 and 7, we can derive the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Suppose be any fault-free edge, and let enote the set which consists of four faulty extreme vertices, namely , , , and , found within any four-cycle ring in . Then, for , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of even length from 4 to in . Moreover, for every even , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of odd length from to in .

4. Concluding Remarks

In a large network, processors or links can experience failures due to either natural calamities or human-induced factors, such as meteorite drops, earthquakes, hacker attacks, and bomb attacks, which can result in regional or scope damage and potentially paralyze the network. Therefore, analyzing the reliability of networks in the field of fault-tolerant embedding research has become an important research topic.

This paper addresses the reliability analysis problem in the context of the folded hypercube network . Specifically, for any fault-free edge in , we consider the set of faulty extreme vertices , , , } in any four-cycle ring of . We show that, for , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of even length from 4 to in . Furthermore, for every even , every fault-free edge can lie on a cycle of odd length from to in . In future works, we will further investigate the problem of path embedding between any two vertices in .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, C.-N.K.; validation, C.-N.K. and Y.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-N.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.-H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan (under grant no. 111-2221-E-432-001, 112-2221-E-432-002, 112-2218-E-005-010, 111-2218-E-005-009, 111-2622-E-324-004, and 111-2821-C-324-001-ES).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tien, S.; Raghavendra, C.; Sridhar, M. Generalized Hypercubes and Hyperbus structure for a computer network. In Hawaii International Conference on System Science; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- El-Amawy, A.; Latifi, S. Properties and performance of folded hypercubes. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 1991, 2, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Xu, J.; Du, Z. Edge-fault-tolerant hamiltonicity of folded hypercubes. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. China 2006, 36, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.-M.; Ma, M.; Du, Z. Edge-fault-tolerant properties of hypercubes and folded hypercubes and folded hypercubes. Australas. J. Comb. 2006, 35, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.-S. Fault-free cycles in folded hypercubes with more faulty elements. Inf. Process. Lett. 2008, 108, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-Y. Some edge-fault-tolerant properties of the folded hypercube. Networks 2007, 51, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Hao, R.-X.; Feng, Y.-Q. Cycles embedding on folded hypercubes with faulty nodes. Discret. Appl. Math. 2013, 161, 2894–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Hao, R.-X.; Feng, Y.-Q. Embedding even cycles on folded hypercubes with conditional faulty edges. Inf. Process. Lett. 2015, 115, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-N.; Cheng, Y.-H. Fault-free cycles embedding in folded hypercubes with F4. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2020, 820, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-N.; Cheng, Y.-H. Every edge lies on cycles of folded hypercubes with a pair of faulty adjacent vertices. Discret. Appl. Math. 2021, 294, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Lin, C.-K. Graph Theory and Interconnection Networks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.-Y.; Kuo, C.-N. Hamiltonian-connectivity and strongly Hamiltonian-laceability of folded hypercubes. Comput. Math. Appl. 2007, 53, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, G.; Pan, X. Path embedding in faulty hypercubes. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 192, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.-K.; Tsai, C.-H.; Tan, J.J.; Hsu, L.-H. Bipanconnectivity and edge-fault-tolerant bipancyclicity of hypercubes. Inf. Process. Lett. 2003, 87, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).