Abstract

Two nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton (NZP) models for a closed ecosystem that incorporates a delay in nutrient recycling, obtained using the gamma distribution function with one or two degrees of freedom, are analysed. The models are described by systems of ordinary differential equations of four and five dimensions. The purpose of this study is to investigate how the mean delay of the distribution and the total nutrients affect the stability of the equilibrium solutions. Local stability theory and bifurcation theory are used to determine the long-time dynamics of the models. It is found that both models exhibit comparable qualitative dynamics. There are a maximum of three equilibrium points in each of the two models, and at most one of them is locally asymptotically stable. The change of stability from one equilibrium to another takes place through a transcritical bifurcation. In some hypotheses on the functional response, the nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton equilibrium loses stability via a supercritical Hopf bifurcation, causing the apparition of a stable limit cycle. The way in which the results are consistent with prior research and how they extend them is discussed. Finally, various application-related consequences of the results of the theoretical study are deduced.

Keywords:

plankton; nutrient recycling; delay; gamma distribution; closed ecosystem; dynamics; bifurcation MSC:

37N25; 35G10; 34D20

1. Introduction

Plankton are floating organisms that provide a food source for other organisms ranging from shellfish to whales. As such, they play a crucial role in aquatic foodwebs [1]. Phytoplankton are organisms, such as algae, which carry out photosynthesis and are an important means of carbon storage in the ocean [2]. Zooplankton feed on phytoplankton or other zooplankton and include insect larvae and jellyfish. Due to their fundamental role in aquatic ecosystems and their influence on the global carbon cycle, it is important to understand the temporal dynamics of plankton ecosystems.

A variety of different models have been proposed for plankton ecosystems, emphasizing different aspects of these complex systems [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Here, we study a model due to Kloosterman et al. [12], which focussed on two aspects. The chemical nutrients in the system are recycled, thus the system is closed—the total amount of nutrient remains constant. This recycling takes time (e.g., due to decomposition of dead organisms) and thus the model should include a time delay. Both are important features of plankton ecosystems that lead to interesting mathematics.

The model of Kloosterman et al. [12] is called an NPZ model as it is a system with three compartments, representing the dissolved nutrient (N ), the amount of phytoplankton (P), and the amount of zooplankton (Z). It is described by the following equations:

Here, and g are positive parameters representing biological properties while is an appropriate distribution representing the time delay in nutrient recycling.

The function f stands for the phytoplankton nutrient uptake as a function of the available nutrient and it has the following properties [4]:

Similarly, the function h stands for the available phytoplankton and it must satisfy conditions [13,14]:

Kloosterman et al. [12] investigated how this model for a planktonic ecosystem is affected by the quantity of biomass it contains and by the delay distribution. They described the existence of the equilibrium points and gave some stability results for a general distribution function, using methods as in [15]. Other stability results considered particular cases of the distribution function and relied primarily on numerical work.

In this study, we assume that the delay follows a gamma distribution function, with either one or two degrees of freedom, as these numbers of freedom degrees correspond to the biological data. We derive two models, described by systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), and analyse how the local stability and local bifurcation of the equilibrium points depend on the amount of total nutrients and on the mean delay of the distribution.

For the numerical simulations we have used a Holling type II functional response for f,

with For function h, we used either a Holling Type II functional response

or a Holling Type III response

with

Using this delay, we have extended the results obtained in [12].

2. The Models

Consider the gamma distribution of mean , with k degrees of freedom:

Starting from system (1) and using the gamma distribution function for the cases and , and some appropriate new variables, we derive two models, described by systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), without explicit delay. This reduction is often called the linear chain trick [16,17,18].

For the case , we obtain a 4-dimensional system of ODEs, which is then reduced to a three-dimensional one. This will be called the weak model.

For , we obtain a five-dimensional system of ODEs that can be reduced to a four-dimensional system, which will be called the strong model.

2.1. The Weak Model

If we have for Denoting

the equation describing the evolution of the dissolved nutrient N can be written as:

In addition, using the change of variable we have:

It follows:

With the change of variable we have

Thus, we obtain a 4D model (), called “the weak model” in the following, described by

Since the conservation law is fulfilled, we obtain The substitution leads to the following reduced 3D system:

with the phase space

2.2. The Strong Model

If the number of freedom degrees is we have for Denoting

the equation describing the evolution of the dissolved phytoplankton nutrient from (1) reads:

In addition, using the change of variable we have

Denoting by

it follows:

Thus, we obtain the following 5D model , also called “the strong model”:

Obviously, the conservation law

is fulfilled, so we can substitute leading to the following reduced 4D system of ordinary differential equations (ODE):

with the phase space

Also, for consistency, the initial conditions of the ODE model must satisfy

2.3. The Model without Delay

In the absence of delay, the model (1) is described by the following equations:

Using conservation law this system can be reduced to the following 2D system:

with the phase space

In the following, shall denote the biomass of the model. Thus, when referring to the model without delay , for the weak model , while for the strong model .

3. Equilibrium Solutions

In this section, we determine the stationary solutions of the two reduced systems (7) and (15), for the NPZ model with delayed gamma distribution, with one or two degrees of freedom. These solutions correspond to the equilibrium points of the corresponding dynamical systems.

Each of the three systems has at most three equilibrium points în the region of interest, namely:

- -

- A trivial equilibrium , with no phytoplankton and no zooplankton;

- -

- An equilibrium with phytoplankton and no zooplankton, denoted ;

- -

- An equilibrium with both phytoplankton and zooplankton, denoted .

These equilibria may coexist for certain values of the total nutrients. The same property is valid for the reduced 2D system (18) for the NPZ model without delay.

3.1. Equilibrium Points for the System without Delay

3.2. Equilibrium Points for the Reduced Weak System (7)

The system (7) possesses at most three equilibria with the first three coordinates non-negative, solutions of the system

It follows that the trivial equilibrium is

The equilibrium with only phytoplankton is with Taking into account the properties of if the condition

is satisfied (that is the growth rate of the plankton must be greater than the death rate), then there exists an unique namely satisfying this condition. From the first equation we obtain

while from the conservation law we obtain

This equilibrium is in the domain of interest if and only if Note that if then

The equilibrium with both phyto- and zooplankton is with from the third equation in (23). If condition

is satisfied, then there exists an unique such that namely

and

The condition must be satisfied in order to have As f is an increasing function, it follows that and using the first equation of system (23) we have

To show that there exists an such that

is satisfied, consider the function

It follows that and As F is an increasing function, there exists an unique value such that

Denote, as in [12], Remark that . As a consequence, the third equilibrium point exists in and is uniquely determined by (30) if the conditions and (20) are satisfied. Note that if then The transitions between the equilibrium points will be discussed further in Section 5.

Finally, we note that if is an equilibrium of system (7), then with is an equilibrium point for system solution of system (6) and conversely.

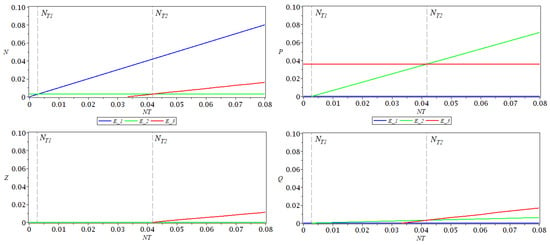

In Figure 1, the coordinates of the three equilibrium points are represented as functions of the total nutrient , for a fixed . As function h, a type II functional response was considered. The values of the parameters used for simulations are , , , , , , , as in [12]. For these values of the parameters, the following values where obtained for thresholds: , .

Figure 1.

as functions of , for fixed , for the equilibrium points (blue line), (green line), (red line), using a type II response.

3.3. Equilibria for the Reduced Strong Model (15)

The equilibria of system (15) correspond to the solutions of the system

Substituting

from the first equation into the last equation in (31), the remaining three equations coincide with system (23). Consequently, we obtain the same expressions for and Z as for system (23). Taking into account (32), we obtain the following equilibrium points for system (15):

- (1)

- The trivial equilibrium for all

- (2)

- The equilibrium with no zooplankton withfor all , with if ;

- (3)

- The equilibrium , withfor all with if and .

Note that if is an equilibrium of system (15), then is an equilibrium point for system solution of system (13) and conversely.

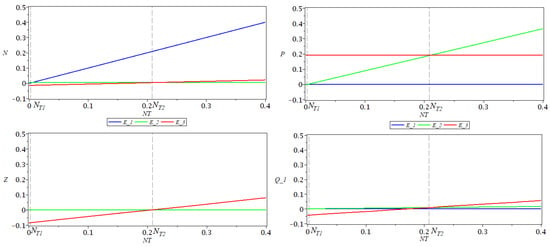

In Figure 2, there are represented the coordinates of the three equilibrium points as functions of the total nutrient , for a fixed . As function h, a type III functional response was considered. The values of the parameters used for simulations are , , , , , , , as in [12]. For these values of the parameters, the following values were obtained for stability thresholds: , , . Remark that at and at .

Figure 2.

as functions of , for fixed , for the equilibrium points (blue line), (green line), (red line), using a type III response.

Comparing the systems with and without delay, we see the following.

- The equilibrium point is unaffected by the delay.

- For the equilibrium point , the value of P is reduced by the delay.

- For the equilibrium point , the values of N and Z are reduced by the delay.

- The first transition point is unaffected by the delay, while the second transition point is increased by the delay, if

4. Local Stability

For all three systems (7), (15) and (18), we find that at each value of the total nutrient at most one of the equilibrium points is locally asymptotically stable. More precisely,

- for the only equilibrium point is and it is asymptotically stable,

- for the equilibrium is asymptotically stable, while is unstable,

- and, finally, as the equilibrium is asymptotically stable either for all or there exists an such that is asymptotically stable for , and unstable for depending on the response function while the other two equilibria are unstable.

Note that for the system without delay (18), is equal to . Our results for and reproduce the results of [12] for the system with general delay (1), while our results for improve those of [12].

Note that, for the two-dimensional reduced system without delay (18), the local stability of the equilibria on the boundary of the domain can be extended to global stability [12]. Those arguments cannot apply for systems (7) and (15). Results on the global stability could be obtained using Lyapunov functions, if they can be constructed.

4.1. The System without Delay

In [12], it is shown that the equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable on if the equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable on except for the z axis, if while the stability of the equilibrium point depends on the sign of the quantity denoting the trace of the Jacobi matrix at

Here, to simplify the expression, we denoted ,

They proved that if then the equilibrium point is stable for all This is valid for a type III zooplankton grazing response function While if then there exists a unique value of the total nutrient, such that the equilibrium point is asymptotically stable for all and unstable if The value is found as the unique solution of the equation with

For the Jacobi matrix has the purely imaginary eigenvalues with Close to we have Consequently,

and thus the transversality condition in the Hopf bifurcation theorem is satisfied. A Hopf bifurcation takes place for if the Lyapunov coefficient is non-zero.

4.2. The Weak Model Case

We analyse here the stability of the equilibrium points for the system (7) corresponding to the gamma distribution delay, with one degree of freedom.

Proposition 1.

For the equilibrium point of system (7), the following statements hold:

- (i)

- If , then is locally asymptotically stable in ;

- (ii)

- If , then is a (2,1) type saddle point;

- (iii)

- If , then is a fold singularity.

Proof.

As two eigenvalues are negative, the topological type of is determined by the sign of Thus, the equilibrium point is an attractor if , i.e., As f is an increasing function, we have if □

Proposition 2.

The equilibrium point of system (7) is locally asymptotically stable in if and only if

In addition,

- (i)

- if or then is a fold singularity;

- (ii)

- if then is a saddle point of type (2,1);

- (iii)

- if then is not in

Proof.

For the equilibrium we obtain the Jacobi matrix

and the characteristic equation

with

Thus, one eigenvalue is and we have if (that is as h is an increasing function). Consequently, iff

and if .

The other two eigenvalues are solutions of the equation Further, if it follows that both solutions of this equation have negative real parts. As a consequence, if , all eigenvalues have negative real parts, hence the equilibrium point is an attractor.

Note that if then thus and The equilibrium point is a fold singularity both at and . □

For the equilibrium point of system (7), the Jacobi matrix reads

where, to simplify computation, we denoted:

Thus, the characteristic polynomial of reads

with

Using the Routh–Hurwitz criterion [19], all the roots of the characteristic polynomial have negative real parts if and only if the following conditions are satisfied:

Thus, the equilibrium point is asymptotically stable if all these conditions are fulfilled. In [12], one result on the stability of with the weak gamma distributed delay was obtained. For completeness and for comparison with the strong gamma distribution case, we repeat that result here with proof.

Proposition 3.

Proof.

The equilibrium point is stable if all conditions in (38) are fulfilled. To simplify computation, denote

Note that, . With these notations, we can write

As all parameters are positive, it follow that As conditions and are satisfied. As

condition (iii) in (38) is satisfied. Consequently, all eigenvalues have negative real parts, and is an attractor for all □

Proposition 4.

- (i)

- For close to the equilibrium point is an attractor.

- (ii)

- If , then is locally asymptotically stable.

- (iii)

- If then is a Hopf singularity.

- (iv)

- If then is a (1,2) saddle point. In addition, for each τ there exists a value given by

such that is locally asymptotically stable for all and unstable for close to

Proof.

(i) The coefficient is equal to 0 if and only , which occurs when The discussion following (29) then shows that at and for

For the other two coefficients of the characteristic equation associated to ,

have positive values, and also As the expressions are continuous functions of they remain positive for in a neighbourhood of Hence (i).

(ii) Considering as a function of we obtain

Also,

Differentiating with respect to in (30), we obtain

hence As and , it follows that thus is a decreasing function of Consequently, The result follows by applying the Routh–Hurwitz criterion [19].

(iii) The characteristic polynomial (36) has a pair of purely imaginary roots if conditions

As for all if then . Thus, is a Hopf singularity.

(iv) As for all and it follows that is the minimum value of for which condition is not satisfied. □

For the type II response function h, we have

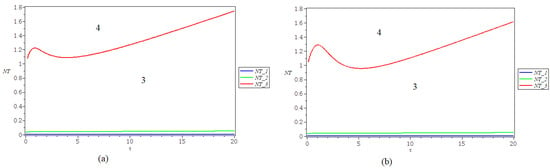

In this case, Proposition 4 applies for the stability of the equilibrium point See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Regions in the plane that exhibit different behaviours for the equilibrium , using the Type II response for: (a) the weak model; (b) the strong model. Region 3 is where the and is stable, but where , are unstable. For parameters on the curve separating regions 3 and 4, is a Hopf singularity, while in region 4, is unstable. A Hopf bifurcation may take place when parameters cross from region 3 to region 4.

For the type III response function h, we obtain

In this case, if (i.e., then and the equilibrium point is stable for all If then Proposition 4 applies for the stability of the equilibrium point

4.3. The Strong Model Case

Proposition 5.

The following assertions hold for the equilibrium point of system (15).

- (i)

- If , then is locally asymptotically stable in

- (ii)

- If , then is a (3,1) type saddle point.

- (iii)

- If , then is a fold singularity.

Proof.

For the equilibrium , we obtain the Jacobi matrix

and the characteristic polynomial Thus, has the eigenvalues

As three eigenvalues are negative, the topological type of is determined by the sign of Thus, the equilibrium point is an attractor if , i.e., As f is an increasing function, we obtain if □

Proposition 6.

The equilibrium of system (15) is locally asymptotically stable in if and only if

In addition,

- (i)

- If or , then the equilibrium is a fold singularity;

- (ii)

- If , then the equilibrium is a saddle point of type (3,1);

- (iii)

- If , then the equilibrium is not in

Proof.

For the equilibrium we obtain the Jacobi matrix

and the characteristic equation

with

Thus, one eigenvalue is and we have if (that is as h is an increasing function). Consequently, if

and as The other three eigenvalues are solutions of the equation According to the Routh–Hurwitz criterion, all solutions of this equation have negative real parts if conditions

are fulfilled. As all parameters are positive, if the first two conditions are satisfied. A simple computation shows that the third condition is also satisfied if As a consequence, if all eigenvalues have negative real part, hence the equilibrium point is an attractor.

Note that if then thus and The equilibrium point is a fold singularity both at and . □

For the equilibrium of system (15), the Jacobi matrix reads

and the characteristic polynomial is

with

Using the Routh–Hurwitz criterion [19], all the roots of the characteristic polynomial have negative real parts if and only if the following conditions are satisfied:

Thus, the equilibrium point is stable if all these conditions are fulfilled.

Proposition 7.

For the equilibrium point of system (15), the following assertions hold.

- (i)

- For close to the equilibrium point is an attractor.

- (ii)

- If one of the conditions , in (44) is not satisfied, then is unstable. In addition, for each τ there exists a value given by

such that is locally asymptotically stable for all

Proof.

The coefficient is equal to 0 if and only Thus, we have at and for

At the other three coefficients of the characteristic equation associated with have the following values:

In addition, we have

As the expressions are continuous functions of they remain positive for in a neighbourhood of Hence (i). Obviously, is the minimum value of for which one of the conditions (44) is not satisfied. □

Remark 1.

As for we have none of the eigenvalues can be 0. Thus, the topological type of could change only with the appearance of a pair of purely imaginary eigenvalues. Using the Viète relations, if conditions

are satisfied, then the equilibrium point is a Hopf singularity. If

then the equilibrium point has two pairs of purely imaginary eigenvalues and it is a double-Hopf singularity.

Proposition 8.

Assume

- (i)

- If then the equilibrium of system (15) is locally asymptotically stable for all

- (ii)

- If then is a Hopf singularity.

- (iii)

- If then is unstable. In addition, for each τ, there exists a value given by

such that is locally asymptotically stable for all

Proof.

The equilibrium point is stable if all conditions in (38) are fulfilled. To simplify computation, denote:

Note that, . With these notations, we can write:

As all parameters are positive, it follow that As conditions are satisfied if the hypothesis (47) is true. As

condition is satisfied if (47).

Consequently, if then all eigenvalues have negative real parts, thus is an attractor.

If at least two eigenvalues have negative real parts, thus is unstable. As for we have

the expression continue to be positive for close to Obviously, is the minimum value of for which □

In Figure 3, there are represented the strata in the plane that exhibit different behaviours for the three equilibrium points, obtained in the case of a type II response . The curve denoted NT_1 (blue line) separates the strata where changes stability with . The equilibrium is stable for parameters in the stratum limited by the curves NT_1 (blue line) and NT_2 (green line). The equilibrium is stable for parameters in region 3, in the stratum limited by the curves NT_2 (green line) and NT_3 (red line), and loses stability in region 4. The other two equilibria are unstable in regions 3 and 4.

The values of the parameters used for simulations are , , , , , , . The results are consistent with the ones obtained in [12].

5. Local Bifurcations

In the previous section, we proved that at each value of the total nutrients at most one of the equilibrium points is locally asymptotically stable. In this section, we show that the change of stability is realized either through a transcritical bifurcation or a Hopf bifurcation that may occur at a fold singular point or at a Hopf singularity, respectively.

5.1. Transcritical Bifurcations

Two transcritical bifurcations undergo for both the weak and the strong models, namely:

- (i)

- at the equilibrium points and collide and interchange stability;

- (ii)

- at the equilibrium points and collide and interchange stability.

We prove these results by using the Sotomayor theorem [20], ([21], p. 338).

5.1.1. Transcritical Bifurcations for the Weak Model

Proposition 9.

A transcritical bifurcation takes place at the equilibrium of system (7) as .

Proof.

As we have and the equilibrium is a fold singularity. We consider as the bifurcation parameter, and the bifurcation value is It follows and at we have The normal form on the centre manifold is determined using Sotomayor theorem [20,21]. In order to carry this out, consider first two eigenvectors such that and As for we obtain that and Then, we compute the quantities C in Sotomayor theorem, where

with and and is the vector field associated with system (7). As and vector w has only one non-zero component, we need only the second component of the vector field which can be written as

We obtain

and

Consequently, a transcritical bifurcation takes place as i.e., . □

In a similar way we prove that a transcritical bifurcation takes place when the equilibria and coincides, as

Proposition 10.

A transcritical bifurcation takes place at the equilibrium of system (7) as .

Proof.

As we have , with

, and the equilibrium is a fold singularity. We consider as the bifurcation parameter, and the bifurcation value is Apply the Sotomayor theorem [21] as above. Consider two eigenvectors such that and As we obtain that and with As and vector w has only one non-zero component, we need only the third component of the vector field which can be written as

We obtain

and

Consequently, a transcritical bifurcation takes place as i.e., . □

Remark 2.

At the bifurcation, point the two equilibria and have the same eigenvalues, with for and As a consequence of the transcritical bifurcation, the eigenvalues these two eigenvalues change signs when passing through the bifurcation values, while the real parts of the other three pairs of eigenvalues remain negative close to the bifurcation value, due to continuity. Thus, the two equilibria exchange stability. Consequently, close to , if the equilibrium point is an attractor and is a saddle of type (2,1), while if the equilibrium point is a saddle of type (2,1) and is an attractor.

5.1.2. Transcritical Bifurcations for the Strong Model

Proposition 11.

A transcritical bifurcation takes place at the equilibrium of system (15) as .

Proof.

As , we have and the equilibrium is a fold singularity. We consider as the bifurcation parameter, and the bifurcation value is It follows and at we have Consider two eigenvectors such that and As we obtain that and Then compute the quantities C in Sotomayor theorem. As and vector w has only one non-zero component, we need only the second component of the vector field associated with system (15), which can be written as

We obtain

and

Consequently, a transcritical bifurcation takes place as i.e., . □

In a similar way, we prove that a transcritical bifurcation takes place when the equilibria and of system (15) coincides, as

Proposition 12.

A transcritical bifurcation takes place at the equilibrium of system (15) as .

Proof.

As , we have , with and the equilibrium is a fold singularity. We consider as the bifurcation parameter, and the bifurcation value is Apply the Sotomayor theorem [21] as above. Consider two eigenvectors such that and As we obtain that and with As and vector w has only one non-zero component, we need only the third component of the vector field which can be written as

We obtain

and

Consequently, a transcritical bifurcation takes place as i.e., . □

Remark 3.

At the bifurcation point the two equilibria and have the same eigenvalues, with for and As a consequence of the transcritical bifurcation, the eigenvalues these two eigenvalues change signs when passing through the bifurcation values, while the real parts of the other three pairs of eigenvalues remain negative close to the bifurcation value, due to continuity. Thus, the two equilibria exchange stability. Consequently, close to , if the equilibrium point is an attractor and is a saddle of type (3,1), while if the equilibrium point is a saddle of type (3,1) and is an attractor.

5.2. Hopf Bifurcations

A Hopf bifurcation may occur at a Hopf singularity. As we proved in Section 4, only the equilibrium point is a Hopf non-hyperbolic point, in certain conditions (see Propositions 4, 7 and 8). At such a singular point, a Hopf bifurcation takes place if the conditions of the Hopf bifurcation theorem [22] are fulfilled.

5.2.1. Hopf Bifurcations for the Weak Model

As a consequence of Proposition 3, if then the equilibrium point of system (7) is locally asymptotically stable for all , so there can be no Hopf bifurcation in this case.

If then equilibrium point is a Hopf sigularity for parameters in the bifurcation stratum defined by the equation

with given by (37). Consequently, for each such that (48), a Hopf bifurcation may occur, and a branch of periodic solutions may emerge around

Note that the eigenvalues of the Jacobi matrix associated with are with Thus, as , the centre manifold of is attractive. As a consequence, if the conditions of the Andronov–Hopf bifurcation theorem [22] are satisfied and a supercritical Hopf bifurcation takes place (i.e., the first Lyapunov coefficient is negative), then the stable limit cycle born through this bifurcation on the extended centre manifold is locally asymptotically stable.

For the type II response function h, in the hypotheses of Proposition 4, a Hopf bifurcation may take place for each at the bifurcation value

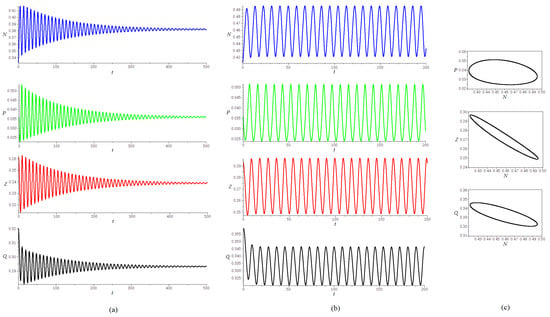

The numerical simulations in Figure 4 show the existence of a stable limit cycle for values of The values of the parameters used for simulations are , , , , , , . The results are consistent with the ones obtained in [12]. For , the approximate value of for the Hopf bifurcation is The simulations show time series for an initial point closed to the equilibrium , proving an evolution towards the steady state for and to a limit cycle for .

Figure 4.

Simulations for the weak model, using a type II response : (a) , , showing an evolution towards ; (b) , , showing a periodic behavior; (c) projections of the attractor, for , , . The stable limit cycle may appear through a supercritical Hopf bifurcation at .

For the type III response function h, for the values of the parameters considered for simulations we have so there are no Hopf bifurcations at as

5.2.2. Hopf Bifurcation for the Strong Model

According to Proposition 8, if the equilibrium point of system (15) is a Hopf singularity if condition

with given by (43), is satisfied.

If the equilibrium point is a Hopf singularity for parameters in the bifurcation stratum defined by the conditions (45). Consequently, for each such that (45), a Hopf bifurcation may occur.

For the type II response function h, Proposition 8 does not apply. For the considered values of the parameters, , , , , , , , we have found that, for on the curve defined by (49) in the parameter plane, the equilibrium is a Hopf singularity. This curve separates regions 3 and 4 in Figure 3b, and a Hopf bifurcation may take place when the parameters cross this curve.

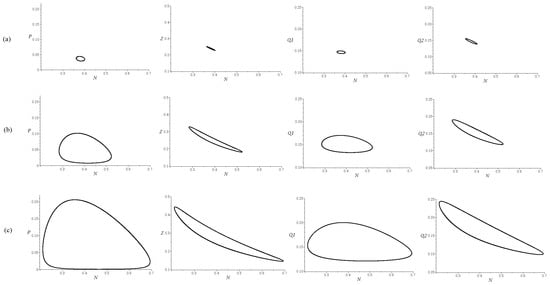

For , the approximate value of for the Hopf bifurcation is . The simulations in Figure 5, show the projections of parts of the trajectories for an initial point near the equilibrium , proving an evolution towards a stable limit cycle, for (a) , (b) and (c) .

Figure 5.

Simulations for the strong model, using a type II response . Projections of the attractor for and (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; . The stable limit cycle may appear through a supercritical Hopf bifurcation at .

The trajectories in Figure 4 and Figure 5 were obtained using the DEtools package in MAPLE 18, applying the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method, with a stepsize 0.01.

Remark 4.

As the parameters vary away from the Hopf bifurcation curve, the limit cycle born through the Hopf bifurcation may disappear, may double the period, etc. Since the dimensions of both the weak and the strong models are greater than three, strange attractors may also exist. Nevertheless, as the domains for each of the two models are bounded, the ω-limit set for each model is also bounded, and so are their attractors.

6. Discussion

In this study, we have analysed two NPZ models for a closed ecosystem with three compartments, dissolved nutrient, phytoplankton and zooplankton, incorporating a delay in nutrient recycling. The models were obtained starting from a NPZ model introduced in [12], by using the gamma distribution function with one or two degrees of freedom. The aim of the paper was to study how the stability and bifurcation of the equilibrium solutions depend on the total amount of nutrient and the delay.

We have shown that each of the two models have at most three equilibrium points in the region of interest, and that at most one of the equilibrium points is locally asymptotically stable at each value of the total nutrients. More precisely,

- (1)

- For there is only one equilibrium point with no phytoplankton and no zooplankton (, which is asymptotically stable;

- (2)

- For the equilibrium with phytoplankton and no zooplankton is asymptotically stable, while is unstable;

- (3)

- As the first two equilibria are unstable, while the equilibrium with both phytoplankton and zooplankton is asymptotically stable either for all or there exists an such that is stable for , and unstable for close to depending on the response function

Further, we have proven that the changes of stability at and occur through transcritical bifurcations. Finally, we have shown that the change of stability at is a Hopf singularity and the associated bifurcation will lead to stable limit cycles if it is supercritical. Numerical simulations show the existence of stable limit cycles for each delay close to the bifurcation value

Thus, for each of the two considered models, the -limit sets contains at most one equilibrium point. In specific hypotheses on the response function h, the -limit sets may contain a limit cycle for certain values of the parameters and . However, as the dimension of both models is greater than 2, the -limit sets may also contain strange attractors.

Our results on the existence of equilibria are consistent with those of [12] for the system with a general distribution (1), who showed the equilibrium values of are only affected by the mean delay and not the form of the distribution. The stability result (1) above reproduces that of [12] for the general distribution case. The stability result (2) is stronger than that of [12] for a general distribution, and thus is likely a consequence of our choice of distributions. In fact, [12] showed that if the system has a discrete delay (Dirac distribution), then the equilibrium may undergo a Hopf bifurcation; however, we show that it is not possible for the distributions we consider. Our results extend those of [12] by proving the stability result (3) for the two systems studied and by proving the types of bifurcations that occur as the stability of the equilibrium points changes. Further, we showed the possibility of a codimension-two double Hopf bifurcation in the system with the two-degrees of freedom gamma distribution.

To conclude, we discuss the implications of our work for application. The general trend of bifurcations of the equilibrium points as the total amount of nutrients is increased is as follows: first, the phytoplankton only equilibrium point, , appears and then the coexistence equilibrium point, . This is is biologically plausible: as more nutrients are available, the system can support more organisms. Our work highlights the fact that a delay in the recycling can be stabilizing: the amount of nutrients needed for the transcritical bifurcation leading to the emergence of to occur increases with the size of the mean delay. We also showed, for a given amount of total nutrients, the delay decreases the equilibrium size of at least one of . This is because some of the nutrients are stored in the other compartments of the system, which represent the nutrients that are being recycled. Both these results were identical for the weak and strong models. Where these models differ was in the effect of the delay on the Hopf bifurcation of the equilibrium point. For both models, as the delay is increased we observe the same qualitative effect: the Hopf bifurcation value increases, then decreases, then increases. However, the variation is larger for the strong model than for the weak model. Thus, the for the weak model is less than that for the strong model for small enough delay, with the reverse for large enough delay.

Author Contributions

M.S., C.R., R.E. and S.A.C. have contributed equally in writing this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Horizon2020-2017-RISE-777911 project. S.A.C. is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fenchel, T. Marine plankton food chains. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1988, 19, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Mackey, K.R. Phytoplankton as key mediators of the biological carbon pump: Their responses to a changing climate. Sustainability 2018, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M. Adding detritus to a nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton model: A dyna mical-systems approach. J. Plankton Res. 2001, 23, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J. NPZ models of plankton dynamics: Their construction, coupling to physics, and application. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, F.J.; Franks, P.J. Size-structured planktonic ecosystems: Constraints, controls and assembly instructions. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 32, fbp145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, S. Turing instability and travelling waves in diffusive plankton models with delayed nutrient recycling. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1998, 61, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S. Oscillations in plankton models with nutrient recycling. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 208, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, T. Material recycling in a closed aquatic ecosystem. II. Bifurcation analysis of a simple food-chain model. Bull. Math. Biol. 1996, 58, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Baglama, J. Nutrient-plankton models with nutrient recycling. Comput. Math. Appl. 2005, 49, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Z.; Ruan, S. Global stability in chemostat-type plankton models with delayed nutrient recycling. J. Math. Biol. 1998, 37, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Campbell, S.A.; Poulin, F.J. Dynamics of a diffusive nutrient-phytoplankton-zooplankton model with spatio-temporal delay. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2021, 81, 2405–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, M.; Campbell, S.A.; Poulin, F.J. A closed NPZ model with delayed nutrient recycling. J. Math. Biol. 2014, 68, 815–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentleman, W.; Neuheimer, A. Functional responses and ecosystem dynamics: How clearance rates explain the influence of satiation, food-limitation and acclimation. J. Plankton Res. 2008, 30, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. The functional response of invertebrate predators to prey density. Mem. Entomol. Soc. Can. 1966, 98, 5–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Kharitonov, V.; Chen, J. Stability of Time-Delay Systems; Control Engineering; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fargue, D. Réducibilité des systèmes héréditaires à des systèmes dynamiques. CR Acad. Sci. Paris B 1973, 277, 471–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Y. Delay Differential Equations: With Applications in Population Dynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, J.M. An Introduction to Structured Population Dynamics; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz, A. On the conditions under which an equation has only roots with negative real parts. In Selected Papers on Mathematical Trends in Control Theory; Bellman, R., Kalaba, R., Eds.; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 72–82. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor, J. Generic bifurcations of dynamical systems. In Dynamical Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 561–582. [Google Scholar]

- Perko, L. Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, Y.A. Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 112. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).