Abstract

This paper studies a parameter estimation problem for the non-linear diffusion equation within multiphase porous media flow, which has important applications in the field of oil reservoir simulation. First, the given problem is transformed into an optimization problem by using optimal control framework and the constraints such as well logs, which can restrain noise and improve the quality of inversion, are introduced. Then we propose the widely convergent homotopy method, which makes natural use of constraints and incorporates Tikhonov regularization. The effectiveness of the proposed approach is demonstrated on illustrative examples.

Keywords:

non-linear diffusion problem; inversion; parameter estimation; constrained homotopy method; porous media flow MSC:

60J60; 65H20; 65M32; 76S05

1. Introduction

The non-linear diffusion equation, which can approximatively describe the multiphase porous media flow processes, has received considerable attention in recent years due to increasing applications in science and engineering. An oil reservoir simulation based on the inverse problem for this equation has many important applications in fields, such as oil and gas exploration and management of petroleum reservoirs. For example, it can help reservoir engineers make important decisions about the type of the recovery method, fluid production and injection rates, and well locations. From then on, a variety of effective numerical methods have appeared in the literatures of the inverse problem for non-linear diffusion problems [1,2,3,4,5,6]. This inverse problem can be viewed as a parametric data-fitting problem. It is possible to formalize such a problem in the optimal control framework where a control functional defined in terms of discrepancy between measurement and computed data is minimized over a model space. Generally speaking, this inverse problem is very difficult to solve, because of its own ill-posedness and non-linearity. The ill-posed property makes the parameter field susceptible to the noise in the measurement data, while the non-linear dependence of the measurement data with respect to the parameter field causes the presence of numerous local minima. For the non-linear ill-posed problem, conventional linearized methods, such as the Gauss–Newton method [7], Landweber method [8], Levenberg–Marquardt method [9], are locally convergent. The recent popular methods (e.g., trust region algorithm [10], neural networks algorithm [11], genetic algorithm [12], simulated annealing algorithm [13]) have global convergence properties, but the efficiency is much worse than before, along with the searching space decreasing. When the level of the noise in the measurement data is high, all these methods fail to converge. Consequently, the shortcomings of the above methods motivate us to construct a globally convergent, efficient, and stable algorithm.

The novel and effective homotopy method has been successfully used to solve non-linear problems, such as time- or space-fractional heat equations [14], fractional-order convection–reaction–diffusion equations [15], fractional-order Kolmogorov and Rosenau–Hyman equations [16], second kind integral equations [17], and so on. A remarkable advantage of this method is that it exhibits global convergence under certain weak assumptions [18]. Lately, the homotopy method has also been extended for dealing with inverse problems. Many authors studied the homotopy solution of geophysical inverse problems [19,20,21]. Słota et al. [22,23] and Hetmaniok et al. [24] presented the applications of the homotopy method for solving inverse Stefan problems. Hu et al. [25] considered the homotopy algorithm to improve PEM identification of ARMAX models. Zhang et al. [26] proposed the non-linear and non-convex image reconstruction algorithm based on the homotopy method. Biswal et al. [27], Hetmaniok et al. [28,29], and Shakeri and Dehghan [30], respectively, considered the Jeffery–Hamel flow inverse problem, the inverse heat conduction problem and the diffusion equation inverse problem by the homotopy perturbation method. Liu [31,32] formulated the multigrid-homotopy approach directly in a framework of non-linear inverse problems, and formulated the wavelet multiscale-homotopy algorithm for the solution of partial differential equation parameter identification problems.

Generally speaking, a parameter inversion for non-linear diffusion problems estimates parameters only using the measurement data, which usually have a low signal-to-noise ratio. In order to restrain the noise and improve the quality of inversion, the constraint condition has a wide application in the inversion fields, such as atmospheric research [33], petrophysics [34], remote sensing of environment [35], and geological exploration [36]. This is because the constraint condition, recorded from the interior of the object to be measured, has a high signal-to-noise ratio.

In this article, a well-log constraint is introduced for the parameter estimation for non-linear diffusion problems, and an optimization problem is formed by the finite difference discretization. This problem is a typical ill-posed problem, so the Tikhonov regularization needs to be imposed. In order to overcome the weakness of the local convergence of conventional methods, the homotopy method is applied to the normal equation of the regularized control functional, and then the constrained homotopy method is constructed. Numerical simulations conducted with two synthetic examples illustrate the effectiveness of this method.

2. Mathematical Model

The non-linear diffusion equation, describing, approximatively, the multiphase porous media flow processes, has one of the following two forms

or

where is the concentration at and at time t, is the permeability at in the medium, is a piecewise smooth source function, N is the positive non-linear function of or u, which is used to model the main characteristics of the non-linearity associated with the permeability parameter in the multiphase porous media flow. For simplicity, the problem is studied in the unit square domain under the initial-boundary conditions

3. Parameter Estimation Framework

, are the spatial step sizes, and is the time step size. The concrete expression for is not the focus of this article, so we do not describe it here. For interested readers, see [37].

Let denote the measurement data and form the vector in the same sequence as , and let

where is the permeability from the well logs of a well located at point in the direction. Now we define the admissible set

and the optimal control problem as follows. Find satisfying

It is difficult to solve this problem directly so usually one transforms it into another easier-to-solve form.

Let us assume

Obviously

Therefore, the above optimal control problem can be rewritten, without constraint, as

where is a constraint parameter to determine the strength of the constraint. This unconstrained optimal control problem (7) will be used to approximate the solution of the original constrained optimal control problem. The minimum of Equation (7) and are close to each other when is large enough, and consequently in the specific inversion process, must be specified large enough, such that the solution of Equation (7) can well approximate .

4. Inversion Method

4.1. Basic Iterative Method

Due to the ill-posed property of Equation (7), Tikhonov regularization needs to be imposed

where , are the regularization parameters, , are, respectively, the second-order smooth matrices in the and direction (see [37]), and is an initial estimate.

It is obvious that Equation (8) is equivalent to the corresponding normal equation

where represents derivative of A with respect to . The second derivative appears in the Newton iterative method, so we use a successive linearization method to solve Equation (9).

If we make the hypothesis that the kth approximation of has been obtained, then in order to avoid the impact of the second derivative, the linear function is used to replace , where is the linear approximation of at point . The regularized control functional in Equation (8) is transformed into

and its normal equation is

the solution of which is exactly the next approximation to :

This iterative method is actually a variant of the iteratively regularized Gauss–Newton method [38], and has the same fast convergence speed and good stability as the latter, however it is a locally convergent method.

4.2. Homotopy Method

To improve the local convergence of Equation (12), the homotopy method is introduced to solve Equation (9). We take into account the following fixed-point homotopy equation

where is the homotopy parameter.

To obtain , we first rearrange Equation (13) as

and then divide the interval into . For , the iterative method similar to Equation (12) is applied to Equation (14) in sequence from to . For , the initial estimate can be chosen as , which is already known. The initial estimate of is chosen as , which is obtained by solving . Therefore, we can have the iterative formula

The stopping point is defined here as the point at which the modification is equal to or less than a threshold value.

Equation (15) has a fast convergence rate similar to the variant of the regularized Gauss–Newton method (12), so a good approximation to can be obtained by only one iteration when is small enough. In order to save unnecessary computational cost, we can let

where means that we use Equation (15) to iterate one step to obtain , and then have . In this way, Equation (15) is simplified as follows:

Then, consider the iterative result of Equation (16) as the initial estimate for Equation (12), and compute the solution of Equation (9) by iterating Equation (12). That is, Equations (16) and (12) are combined into the constrained homotopy method, which has not only fast convergence speed and good stability, but also a global region of convergence.

When , Equation (8) is the habitual parameter inversion for non-linear diffusion problems, and Equations (16) and (12) can, respectively, be re-expressed as

and

From the expressions of Equations (17) and (18) (Equation (18) is just the iteratively regularized Gauss–Newton method), we can see that Equation (17) has the same calculation amount and storage requirement as Equation (18) at each step. What is important is the application of the first-order derivative, the evaluation of the adjoint operator, and the forward-modeling run. However, the most important is that Equation (17) has a wider convergence region than Equation (18).

4.3. Global Convergence of Homotopy Method

Equation (13) can actually be seen as the normal equation of the following optimal control problem:

Let

then our next result, similar to the Theorem 3.1 of [39], gives certain conditions that validate the global convergence of homotopy method.

Theorem 1.

For any , assume that is the global minimum of and is differentiable with respect to χ. Assume, also, that there exist a such that has no local minimum in the region . Then, all the global minima of can be computed by sequentially minimizing , with a sufficiently small .

Proof of Theorem 1.

Since is differentiable with respect to , denote , where L is a positive constant.

Then

with .

It follows from the assumption that the initial estimate is in a region where there is no additional local minimum. □

5. Numerical Experiments and Results

We have performed two numerical experiments to test the merits of our method. In all experiments, some basic parameters are

where the values of the regularization parameters , are chosen by trial and error.

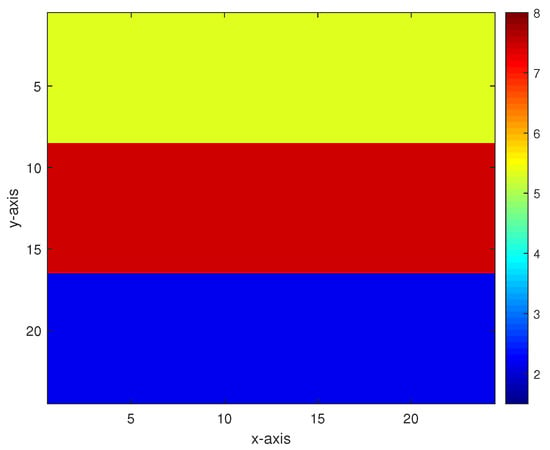

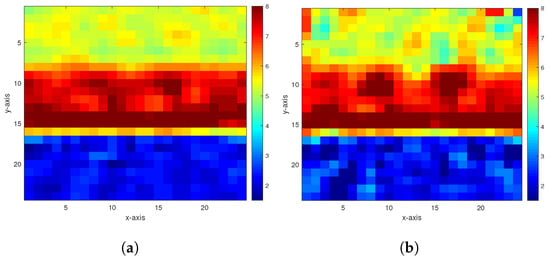

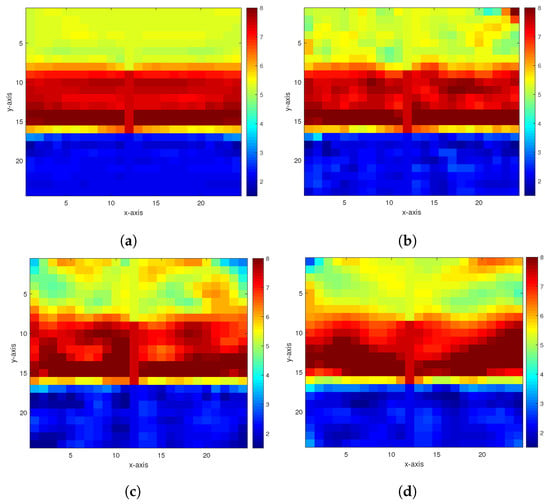

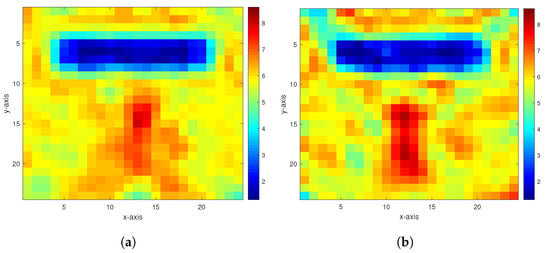

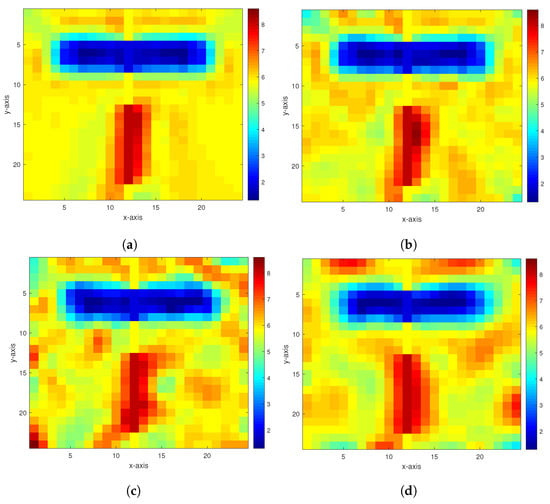

In the first numerical experiment, we consider a horizontal stratified medium containing two interfaces, as shown in Figure 1, and take . To illustrate the noise sensitivity, 40, 30, 20, and 10 dB Gaussian noises are, respectively, added to the measurement data, and then, the parameter is estimated from noisy data. The inversion results of the homotopy method with 40 and 30 dB Gaussian noises added are shown in Figure 2, and the inversion results of the constrained homotopy method with 40, 30, 20, and 10 dB Gaussian noises added are shown in Figure 3. To compare differences among the three methods, the constrained homotopy method (Equations (12) and (16)), the homotopy method (Equations (17) and (18)), and the constrained method (Equation (12)), Table 1 tabulates the relative errors and CPU times of the inversion results by these methods.

Figure 1.

True model in the first experiment.

Figure 2.

The inversion results of the homotopy method in the first experiment. (a,b) are the inversion results with 40 and 30 dB Gaussian noises, respectively.

Figure 3.

The inversion results of the constrained homotopy method in the first experiment. (a–d) are the inversion results with 40, 30, 20, and 10 dB Gaussian noises, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of the three methods in the first experiment.

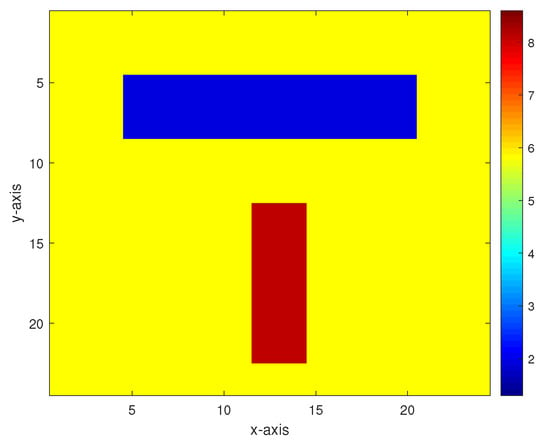

In the second numerical experiment, we take , and consider the model of two anomalous bodies in a homogeneous medium with a permeability of 5.82. The anomalous bodies have the permeability of 1.88 and 8.13, respectively. Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively, show this model and inversion results of the homotopy method with 40 and 30 dB Gaussian noises added. Figure 6 shows the inversion results of the constrained homotopy method with 40, 30, 20, and 10 dB Gaussian noises added. For comparison, Table 2 tabulates the relative errors and CPU times of the inversion results by the constrained homotopy method, the homotopy method, and the constrained method.

Figure 4.

True model in the second experiment.

Figure 5.

The inversion results of the homotopy method in the second experiment. (a,b) are the inversion results with 40 and 30 dB Gaussian noises, respectively.

Figure 6.

The inversion results of the constrained homotopy method in the second experiment. (a–d) are the inversion results with 40, 30, 20, and 10 dB Gaussian noises, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of the three methods in the second experiment.

- (1)

- The constrained homotopy method has global convergence, fast convergence speed, and good stability;

- (2)

- Both the constrained homotopy method and the homotopy method have wider region of convergence than the constrained method;

- (3)

- The constrained homotopy method has a stronger noise suppression ability than the homotopy method.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents an application of constrained homotopy method to the parameter estimation for non-linear diffusion problems. Numerical results shows the feasibility and effectiveness of this method. Compared with the constrained method and the homotopy method, our approach has wider region of convergence and stronger noise suppression ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; methodology, T.L., Z.D. and J.Y.; software, T.L., Z.D. and J.Y.; validation, T.L., Z.D. and J.Y.; formal analysis, T.L., Z.D. and J.Y.; investigation, T.L., Z.D. and J.Y.; resources, W.Z.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L. and Z.D.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and Z.D.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, T.L.; project administration, T.L.; funding acquisition, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China (A2020501007), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N2123015), the Open Fund Project of Marine Ecological Restoration and Smart Ocean Engineering Research Center of Hebei Province (HBMESO2321), the Technical Service Project of Eighth Geological Brigade of Hebei Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Exploration (KJ2022-021).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nilssen, T.K.; Mannseth, T.; Tai, X.C. Permeability estimation with the augmented Lagrangian method for a nonlinear diffusion equation. Comput. Geosci. 2003, 7, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, M.; Tinaztepe, R.; Tatar, S.; Ulusoy, S.; Al-Hajj, R. Determination of a nonlinear coefficient in a time-fractional diffusion equation. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerngar, N.; Nane, E.; Tinaztepe, R.; Ulusoy, S.; Van Wyk, H.W. Simultaneous inversion for the fractional exponents in the space-time fractional diffusion equation. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2021, 24, 818–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brociek, R.; Wajda, A.; Słota, D. Inverse problem for a two-dimensional anomalous diffusion equation with a fractional derivative of the Riemann–Liouville type. Energies 2021, 14, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brociek, R.; Wajda, A.; Słota, D. Comparison of heuristic algorithms in identification of parameters of anomalous diffusion model based on measurements from sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brociek, R.; Chmielowska, A.; Słota, D. Parameter identification in the two-dimensional Riesz space fractional diffusion equation. Fractal Fract. 2020, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, G.; Giri, A.K. Convergence rates for iteratively regularized Gauss–Newton method subject to stability constraints. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 400, 113744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahdawi, H.K.I.; Alkattan, H.; Abotaleb, M.; Kadi, A.; El-kenawy, E.-S.M. Updating the Landweber iteration method for solving inverse problems. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergou, E.H.; Diouane, Y.; Kungurtsev, V. Convergence and complexity analysis of a Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm for inverse problems. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2020, 185, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, E.; Grepl, M.; Veroy, K.; Willcox, K. A certified trust region reduced basis approach to PDE-constrained optimization. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2017, 39, S434–S460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Schwab, J.; Antholzer, S.; Haltmeier, M. NETT: Solving inverse problems with deep neural networks. Inverse Probl. 2020, 36, 065005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochud, N.; Vallet, Q.; Bala, Y.; Follet, H.; Minonzio, J.G.; Laugier, P. Genetic algorithms-based inversion of multimode guided waves for cortical bone characterization. Phys. Med. Biol. 2016, 61, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.S.; Sato, A.K.; Martins, T.C.; Lima, R.G.; Tsuzuki, M.S.G. GPU acceleration of absolute EIT image reconstruction using simulated annealing. Biomed. Signal Process. 2019, 52, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brociek, R.; Wajda, A.; Błasik, M.; Słota, D. An application of the homotopy analysis method for the time- or space-fractional heat equation. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, H. Application of Aboodh homotopy perturbation transform method for fractional-order convection-reaction-diffusion equation within Caputo and Atangana-Baleanu operators. Symmetry 2023, 15, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, H.; Alshehry, A.S.; Saeed, A.M.; Shah, R.; Nonlaopon, K. Application of the q-homotopy analysis transform method to fractional-order Kolmogorov and Rosenau-Hyman models within the Atangana-Baleanu operator. Symmetry 2023, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noeiaghdam, S.; Araghi, M.A.F.; Sidorov, D. Dynamical strategy on homotopy perturbation method for solving second kind integral equations using the CESTAC method. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2022, 411, 114226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.T. Globally convergent homotopy methods: A tutorial. Appl. Math. Comput. 1989, 31, 369–396. [Google Scholar]

- Jegen, M.D.; Everett, M.E.; Schultz, A. Using homotopy to invert geophysical data. Geophysics 2001, 66, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, P.; Chu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Q. A homotopy inversion method for Rayleigh wave dispersion data. J. Appl. Geophys. 2023, 209, 104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanati, R.; Müller-Petke, M. A homotopy continuation inversion of geoelectrical sounding data. J. Appl. Geophys. 2021, 191, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słota, D.; Chmielowska, A.; Brociek, R.; Szczygieł, M. Application of the homotopy method for fractional inverse Stefan problem. Energies 2020, 13, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słota, D. Homotopy perturbation method for solving the two-phase inverse Stefan problem. Numer. Heat Transf. A-Appl. 2011, 59, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetmaniok, E.; Słota, D.; Wituła, R.; Zielonka, A. Solution of the one-phase inverse Stefan problem by using the homotopy analysis method. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 6793–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Hirasawa, K.; Kumamaru, K. A homotopy approach to improving PEM identification of ARMAX models. Automatica 2001, 37, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Tan, C.; Dong, F. Non-linear reconstruction for ERT inverse problem based on homotopy algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 10404–10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, U.; Chakraverty, S.; Ojha, B.K. Application of homotopy perturbation method in inverse analysis of Jeffery-Hamel flow problem. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2021, 86, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetmaniok, E.; Nowak, I.; Słota, D.; Wituła, R. Application of the homotopy perturbation method for the solution of inverse heat conduction problem. Int. Commun. Heat Mass 2012, 39, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetmaniok, E.; Nowak, I.; Słota, D.; Wituła, R.; Zielonka, A. Solution of the inverse heat conduction problem with Neumann boundary condition by using the homotopy perturbation method. Therm. Sci. 2013, 17, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, F.; Dehghan, M. Inverse problem of diffusion equation by He’s homotopy perturbation method. Phys. Scr. 2007, 75, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. A multigrid-homotopy method for nonlinear inverse problems. Comput. Math. Appl. 2020, 79, 1706–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. A wavelet multiscale-homotopy method for the parameter identification problem of partial differential equations. Comput. Math. Appl. 2016, 71, 1519–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enting, I.G.; Pearman, G.I. Description of a one-dimensional carbon cycle model calibrated using techniques of constrained inversion. Tellus B 1987, 39, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolon, L.; Mohaghegh, S.D.; Ameri, S.; Gaskari, R.; McDaniel, B. Using artificial neural networks to generate synthetic well logs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2009, 1, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzberger, C.; Richter, K. Spatially constrained inversion of radiative transfer models for improved LAI mapping from future Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemon, B.; Auken, E.; Christiansen, A.V. Laterally constrained inversion of helicopter-borne frequency-domain electromagnetic data. J. Appl. Geophys. 2009, 67, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, S. Identification of space-dependent permeability in nonlinear diffusion equation from interior measurements using wavelet multiscale method. Inverse Probl. Sci. Eng. 2014, 22, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakushinskii, A.B. The problem of the convergence of the iteratively regularized Gauss–Newton method. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 1992, 32, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, G.; Liu, J. Numerical solution of inverse scattering problems with multi-experimental limited aperture data. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2003, 25, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).