Abstract

In this work, we consider a classic international trade model with two countries and one firm in each country. The game has two stages: in the first stage, the governments of each country use their welfare functions to choose their tariffs either: (a) competitively (Nash equilibrium) or (b) cooperatively (social optimum); in the second stage, firms competitively choose (Nash) their home and export quantities under Cournot-type competition conditions. In a previous publication we compared the competitive tariffs with the cooperative tariffs and we showed that the game is one of the two following types: (i) prisoner’s dilemma (when the competitive welfare outcome is dominated by the cooperative welfare outcome); or (ii) a lose–win dilemma (an asymmetric situation where only one of the countries is damaged in the cooperative welfare outcome, whereas the other is benefited). In both scenarios, their aggregate cooperative welfare is larger than the aggregate competitive welfare. The lack of coincidence of competitive and cooperative tariffs is one of the main difficulties in international trade calling for the establishment of trade agreements. In this work, we propose a welfare-balanced trade agreement where: (i) the countries implement their cooperative tariffs and so increase their aggregate welfare from the competitive to the cooperative outcome; (ii) they redistribute the aggregate cooperative welfare according to their relative competitive welfare shares. We analyse the impact of such trade agreement in the relative shares of relevant economic quantities such as the firm’s profits, consumer surplus, and custom revenue. This analysis allows the countries to add other conditions to the agreement to mitigate the effects of high changes in these relative shares. Finally, we introduce the trade agreement index measuring the gains in the aggregate welfare of the two countries. In general, we observe that when the gains are higher, the relative shares also exhibit higher changes. Hence, higher gains demand additional caution in the construction of the trade agreement to safeguard the interests of the countries.

Keywords:

international trade; international duopoly; tariff game; prisoner’s dilemma; social optimum; welfare; trade agreements MSC:

91B14; 91B15; 91B60; 91B64; 91B74; 91A80

1. Introduction

The strategic nature of international trade, for instance in the choice of tariffs, makes it a fertile ground for the use of game theory. There is a large body of literature on international trade using game theoretic models with both complete and incomplete information (see [1]). For a theoretical analysis in the framework of the Austrian School of Economics, see [2]. An analysis of the concept of strategic trade policy and a review of such aspects is provided in [3] and [4], respectively. In [5], the authors proposed a model including government R&D subsidies to firms. In [6], a model is studied where governments subsidise firms over the produced quantities to help them in competition against foreign producers as well as a supra-game between governments. Reference [7] extends this work to study export subsidies and export tariffs under incomplete information. Regarding the related subject of export promotion, see also [8,9] for a model and a critique, respectively. In [10], the authors studied dynamic patterns of trade policy, namely protection concerning trade volumes. Furthermore, on the subject of trade patterns and gains, see [11]. In [12], the authors studied price competition (inspired by Bertrand competition) between two international firms with tariffs. Other works in multimarket/international trade models under oligopoly are, for instance, [13,14,15]. In [16], a model for intra-industry trade is proposed and analysed and in [17] an oligopolistic model with trade restrictions is analysed.

The issue of the enforcement of trade agreements is also a very active research topic. For a review of contributions to this topic, see [18]. Enforcement has two important features: firstly, one country may have incentives to deviate unilaterally from the cooperative tariff to its competitive tariff and will likely do so if there is no punishment. Therefore, trade agreements should present a mechanism to punish such deviations. Secondly, since there is no supra-national authority to enact the punishment mechanism, there is a need for international agreements to be self-enforcing. These characteristics lead to the study of enforcement issues in some specific contexts such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), then replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) [19,20]. A typical approach is through the study of certain repeated games that possess a good deal of self-enforcing mechanisms. In [21], the authors adopted this approach and studied alternative instruments in agreements between two symmetric countries. They compared the efficacy of retaliatory tariffs with that of financial compensations through monetary fines. In their model, monetary fines generally yield the same cooperative outcome as tariff retaliation. When the deviation of one of the country is due to an unanticipated shock in model parameters, monetary fines are preferable to tariff retaliation. Moreover, in their model, other possibilities such as the exchanging of bonds yield the same cooperation power as tariff retaliation. In [22], they introduced size inequality between countries. There is a large country and several small countries forming a region with the same market size as the large country. In the second region, countries are individually small, which makes it impossible to threaten with tariff retaliation in a credible way, although they can do so if the whole region acts as a group. These coordination externalities generate asymmetric outcomes in trade agreements based on retaliation through tariffs. In [23], the author considers a two-country asymmetric model. In the mode, trade agreement efficiency does not necessarily imply free-trade. The author then studies various types of transfers between countries: financial compensations/ monetary fines, foreign aid and side payments. The influence of asymmetry on trade agreements and transfers is further studied in [24]. Furthermore, within the framework of repeated games, the authors of [25] considered a model with two firms competing in the same country and they studied the effects of dumping practices. They interpret deviations from collusion by the foreign firm as dumping, followed by a punishment period through the imposition of a tariff blocking exports from the other country during the period of punishment. The authors studied two possibilities after the deviation and punishment periods: competing in a Cournot way or the repetition of the deviation and punishment cycle. In [26], the authors considered a model where there is a monopolistic firm in the home market, but that is in duopoly competition in the foreign country with a firm from that country. They study deviation from collusion in the foreign market by the international firm by increasing production abroad to lower the prices and so practising a kind of dumping, or by increasing production in both countries, lowering prices in both markets, and so deviating without practising dumping.

In this work, we consider a classic duopoly international trade model. There are two countries and a firm in each country that sells in its own country and exports to the other one (as we considered previously in [27] and, for instance, [28]). The model is a two-stage game: in the first stage, the governments simultaneously choose their tariff rates on imports from the other country; in the second stage, firms observe the tariff rates and simultaneously choose their quantities for home consumption and exports. In other words, in the second stage firms have a Cournot–type competition after observing the tariffs chosen by the governments. In the first stage, the decisions of the governments regarding tariffs are seen as the actions of a game specified by the welfare functions of each country. We considered two situations for the government choice: one in which they choose the Nash (competitive) tariffs that competitively maximise their welfares; and another where they choose the tariffs that maximise their joint or aggregate welfare, i.e., the sum of the welfares of the two countries. In this last case, we will say that the governments choose tariffs cooperatively. In other words, a social optimum. In [27], we analysed the tariff game between governments considering the welfare as the utility functions of the governments, as well as other quantities. The welfare function condenses, in a certain way, the utility of the country since it includes the direct gains of the government from tariffs through customs. It also includes the utility associated with its productive sector through the profits of the firms, and the surplus of the consumers. By definition of the cooperative tariffs, the joint or aggregate welfare is bigger with the cooperative tariffs, i.e., the cooperative tariffs benefit the two countries together. We observed that there are two game outcomes: a prisoner’s dilemma (PD), where both welfares are bigger at the social optimum tariffs than at the Nash equilibrium tariffs—this is a usual scenario whereas the Nash equilibrium outcome is Pareto-dominated by another outcome; or a lose–win dilemma (LW) where the welfare of one of the countries is bigger at the social optimum tariffs than at the Nash equilibrium tariffs, whereas the welfare of the other country is bigger at the Nash equilibrium tariffs. In each of these two scenarios, at least one of the countries can improve its welfare if the cooperative tariffs are enforced. However, which one of these outcomes occurs presents qualitatively different scenarios for the countries. In the first case, governments can agree to enforce the cooperative tariffs to improve the utilities of both countries. In the second case, the situation is different as one of the countries is injured by the change to the cooperative tariffs while the other country benefits Thus, to enforce cooperation, there is a need to compensate that country, for instance, through financial compensation or in other terms stated in the agreement. Moreover, in the first case, both countries may improve their welfare but these gains may jeopardise the dominant country’s position in international trade, albeit both welfares are improved. This may also occur in the asymmetric case where only one country undergoes an improvement in welfare. This may occur, for instance, in situations where the country’s welfare is improved, but other aspects such as their output in produced quantities may decrease while other components of the welfare increase, such as, for instance, the consumer’s surplus due to an increase in imports. Thus, even when an agreement is put in place, there might be some internal economic consequences that may distort the relations between the countries.

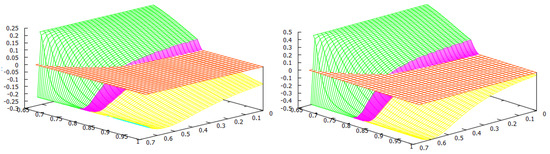

The novelty in this work is that it proposes and discusses a welfare-balanced international trade agreement. The trade agreement has two features: (i) welfare efficiency,whereby the trade agreement implements the cooperative tariffs maximising the aggregate welfare of the two countries, hence increasing the aggregate competitive welfare of the countries when they used the competitive Nash equilibrium tariffs; (ii) competitive fairness, this agreement redistributes the aggregate cooperative welfare according to their relative competitive welfare shares. In other words, the redistribution of the aggregate cooperative welfare that the trade agreement operates is such that the relative share of welfare between the two countries after the trade agreement is the same as when they were using the competitive Nash equilibrium tariffs. Thus, in the welfare-balanced trade agreement, the balance of forces of each country in terms of welfare remains the same, although each one obtains an absolute increase in welfare. However, as we argued above, this trade agreement might exhibit some difficulties since collateral effects occur in the process. They are mainly due to the effects of the enforcement of the cooperative tariffs in some aspects of the country’s economy such as the surplus of its consumers, their revenues from tariffs (which tend to be lower or zero when the cooperative tariffs are enforced), or the profits of its firms and their outputs, which relate to the productive or industrial sectors of the country. These can be analysed through changes in the relative shares of relevant economic quantities such as profits of the firms, consumer’s surplus, and custom revenues before and after the trade agreement, i.e., when the competitive Nash equilibrium tariffs are practiced and when the cooperative tariffs are enforced by the trade agreement. We define these shares and we describe them according to the model parameters. We describe in detail the regions where, according to our model, some of these negative externalities and difficulties in the construction of trade agreements may occur. As such, we analyse the impact of the welfare-balanced trade agreement in the relative shares of these relevant economic quantities. Furthermore, this analysis may also allow us to identify which additional features and conditions can and should be included in the trade agreement such that the effects of the cooperative tariffs in these relative shares can be mitigated. Finally, we also defined and studied the trade agreement index that measures the gains in the aggregate welfare of the two countries. This index is given by the ratio of the aggregate welfare with the cooperative tariffs and the aggregate welfare with the competitive Nash equilibrium tariffs. As we observed above, this ratio is always greater than 1. The redistribution of the aggregate welfare made by the welfare-balanced trade agreement is made proportionally to the trade agreement index. We observe that this index is higher, and hence the gains from the cooperative tariffs are higher when the changes in the relative shares are higher, meaning higher externality effects in other economic quantities. We also relate the index with the game type classification described above. The conclusion is that higher potential gains from cooperation using the welfare-balanced trade agreement require additional caution in the construction of the trade agreement to mitigate the aforementioned deleterious effects and to safeguard the interests of the countries.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we present the international duopoly model and we summarise the main results regarding the game type obtained in [27]. In Section 3, we graphically define and analyse the shares of welfares, profits and consumer surpluses of the countries at the Nash and social tariffs. In Section 4, we propose the welfare-balanced trade agreement. We analyse the shares of the countries in the Nash and social optimum tariffs for the relevant economic quantities in the context of the trade agreement. We analyse the gains of the trade agreement given by the trade agreement index that we computed and analysed. We discuss some of the effects of the trade agreement on the economic quantities and we discuss some forms to mitigate those effects. We present the conclusions of the paper in Section 5.

2. International Duopoly Model

There is a vast literature in applied game theory (see some recent advances in [29,30,31,32,33]). In this section, we introduce the international trade model. We summarise the results previously obtained in [27] for the solutions of the game for the welfare functions of the two countries and that will be used in the subsequent analysis in Section 3 and Section 4.

The international duopoly model is a game with two stages (sub-games). In the first stage, both governments simultaneously choose their Nash or social tariffs relative to their welfare; in the second stage, the firms simultaneously choose their home and export quantities to competitively maximise their profits.

The home consumption is the quantity produced by the firm and consumed in its own country . The export is the quantity produced by the firm and consumed in the country of the other firm , where with . The tariff rate is determined by the government of country on the import quantity from country .

The total quantity produced by firm is

The aggregate quantity sold on the market in the country is

The inverse demand in the country is

where is the demand intercept of country .

The profit of firm is

where is the firm ’s unitary production cost such that , and is the tariff fixed by the government of country .

The custom revenue of the country is given by

The consumer surplus in the country is given by

The welfare of the country is

The welfare function is usually considered to be the objective function of the government. It may take other forms since the government may consider different weights to the components of the total welfare of the country (see, for instance [21,22,28]). In this work, we do not explore this issue and we consider the total welfare to be the sum of the surplus of the consumers with the firm’s profits (which may be seen as producer’s surplus) and with the tariff revenue collected by the government, i.e., consumers, producers, and direct government gains from taxation, respectively.

We define the maximal tariffs by

These are called the maximal tariffs that can be (competitively) imposed by a country such that it has a positive amount of imports. In other words, tariffs higher than the maximal tariffs block the exports of the other country. This will be clear from Equations (10) below.

We also define

Assumption 1.

, , and .

As usual in games with more than one stage, we first solve the second stage sub-game, taking the choices of the first stage game (i.e., tariff choices of the governments) as given (see [28] for more details). We then plug the solution of the second stage sub-game into the first stage sub-game, which we then study.

In the second sub-game, firms competitively maximise their profits in Cournot–type competition. For and , the home and exports of the Nash equilibrium quantities for the firms are given by:

In order to simplify the analysis, we shall define the home production index of country i:

where is the home production of country i when it sets no tariffs, i.e., there are tariff-free exports from country j to country i, and is the monopoly home production of country i when it sets its maximal tariff and hence j does not export. Analogously, we define as the home production index of country . The indexes and satisfy , and furthermore

We will only study this case since the opposite case is symmetrical. The case wherein , which is equivalent to , meaning that and will be studied separately. We observe that in the case we consider, country is the one whose home production index is closer to 1 and so is the country that faces a lower decrease in terms of the ratio between their home production quantities while changing from a monopoly situation to a tariff-free situation where the other country exports freely. On the other hand, country is the one that has a higher decrease in terms of this ratio of home quantities when changing from the maximal tariffs to a tariff-free situation. We shall make the subsequent analysis of the welfares of the countries and other quantities using these two indexes encapsulating the four original parameters of the model, the costs and the demand intercepts.

Now consider the welfare functions of the two countries and after plugging in Equation (7), the Nash home and export quantities that are the solutions of the second stage sub-game. We will denote by the Nash equilibrium welfare, i.e., the welfare at the Nash equilibrium tariffs, and by , the social optimum welfare, i.e., the welfare at the social optimum tariffs maximising the joint welfare of the two countries. Two situations may occur:

- (PD)

- Prisoner’s dilemma:In this case, the game is a Prisoner’s dilemma-type game: the Nash tariffs lead to a lower outcome for both countries than if they would agree with one another (through a trade agreement) to opt for the social optimum.

- (LW)

- Lose–win dilemma:orWhen the game is of lose–win type, there are two possible outcomes that we will denote, respectively, by and . The first indicates that the country has a welfare loss and country has a welfare gain while enforcing the social tariffs, and the second indicates the opposite situation.

The computation of the equilibria tariffs and the analysis of the situations that may occur was performed in [27]. We define the following quantities for country (the quantities for country are symmetric to these ones):

Table 1.

Comparison between the welfares of the two countries with the Nash tariffs and with the social tariffs, where and are the home production indexes satisfying (see Equation (11)). Reproduced from [27].

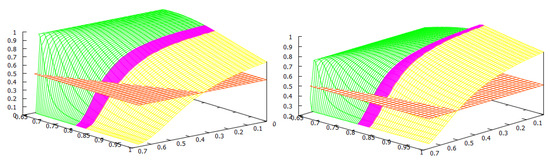

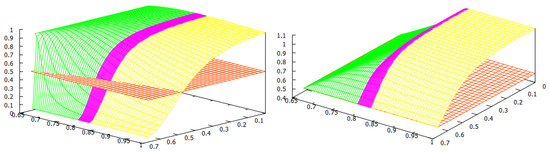

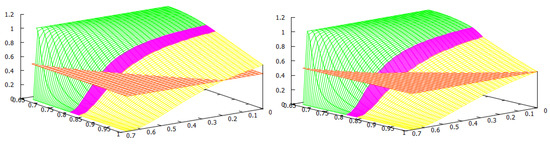

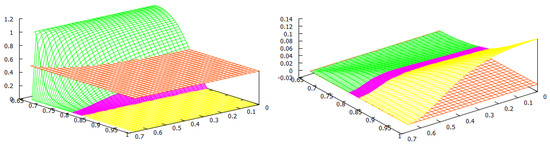

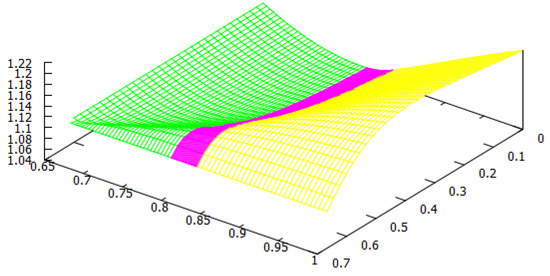

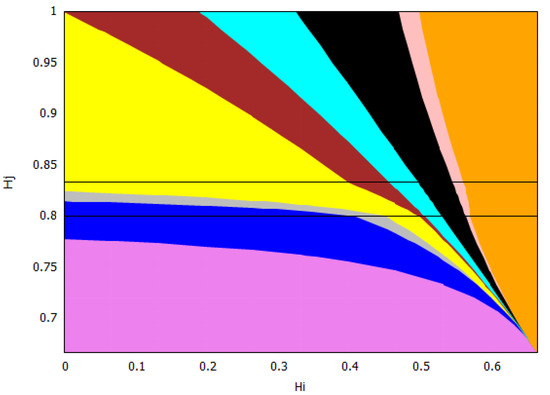

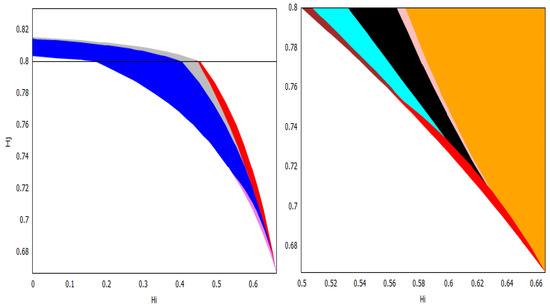

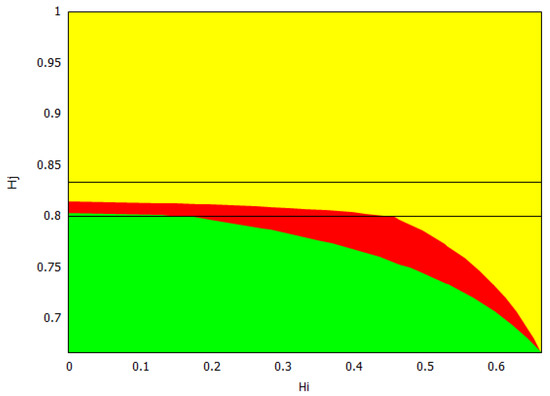

Figure 1.

The welfare game type: Green—; Red—PD; Yellow—. Reproduced from [27].

For the welfare of the countries, we found two thresholds for the home production index : the social-monopoly threshold and the social free-tariff threshold (see Figure 1). For both countries, the social tariffs are lower than the Nash tariffs, and they are lower for both countries except when , where blocks imports in both situations. Thus, any trade agreement that enforces the social tariffs will therefore lower the tariffs used at a competitive (Nash) equilibrium. For all the values of the home production indexes and , country always chooses the Nash tariff and its tariff vanishes at the social optimum.

When is above the social-monopoly threshold , then country blocks imports by setting the maximal tariff at both the Nash and social, and hence in its own market, there is a monopoly by its home firm. Furthermore, the game is of type, and country has a welfare gain. When is below the social-monopoly threshold , the game has three possible outcomes: the prisoner’s dilemma PD or both types of lose–win: and . In this case, the Nash tariff for country is . If its social tariff is , and if , its social choice is to make its tariff disappear. We observe from Figure 1 that when the index is between the two thresholds, the majority of the parameters yield either a PD or a -type game. This means that country has a welfare gain except for a small parameter region where country has a welfare loss (). When is lower and closer to (this means that the home production of is lower in comparison to the home quantity in a monopoly situation), it becomes more likely that the game type is with country losing welfare. For lower values of , does not need to be so low to have a lose–win -type game, and there is a threshold in (approximately ) such that the game is always of this type when is below the social free-tariff threshold. Even for low values of , if the index of country is sufficiently big, i.e., the eventual loss in the ratio that defines is small, then the game is of type, and so country wins welfare. Observe that in this case, due to this greater competitiveness of , it is better at the social optimum for to choose its maximal tariff and block imports and so be monopolistic in its market.

We remark that all the frontiers of the three regions leave from the corner . This observation makes sense once we study this corner separately. In this case, we have , so we have that and which only depends on the maximal tariffs and the game has three outcomes: (1) If the maximal tariffs and are sufficiently close to each other (more precisely ), the game is of Prisoner’s dilemma (PD) type; (2) when one of the maximal tariffs, say , is sufficiently larger than the other maximal tariff, , (more precisely ), the outcome is ; (3) when is sufficiently larger than (more precisely ), the outcome is .

5. Conclusions

We considered an international trade model with two countries and two stages. In the first stage of the game, governments impose their tariffs on imports from the other country. In the second stage of the game, firms in each country choose their home and export quantities competitively in a Cournot–type game. In the tariffs sub-game (first stage game) between governments, they can choose competitive tariffs (Nash) or cooperative tariffs (social) to maximise their joint welfare.

In this context, we proposed and analysed a welfare-balanced trade agreement between the two countries. In such an agreement, the social cooperative tariffs are enforced and the cooperative aggregate welfare of the countries is distributed in a way such that the relative shares of welfare between the two countries are maintained. We discussed some of the effects that present major difficulties for the establishment of the welfare-balanced trade agreement by both parties, and the parameter regions where they occur. These effects are measured through changes in the relative shares of the countries regarding quantities such as the firm’s profits, consumer’s surplus and custom revenues when the cooperative social tariffs are enforced instead of the competitive Nash equilibrium tariffs. We have analysed the gains of the trade agreements through the trade agreement index that we explicitly computed and analysed.

The following questions, among others, can be raised about the trade agreement: (a) what additional measures should be part of the trade agreement to mitigate the negative externalities of the country that has a decrease in its production and/or the profits of its firm, its custom revenue or the surplus of its consumers. These measures may include an R&D swap between both countries and financing to industry and other sectors, among others. We note that countries that can make balanced trade agreements in more than one economic sector such that the total compensation of the agreements is not relevant might be in a better position to negotiate; (b) what additional measures should be part of the trade agreement to force both countries to agree to set the social tariffs in such a way that the agreement is theoretically durable and sustainable in time, preferably rendering it self-enforcing.

The main contribution from the present work is the analysis of the effects regarding the aforementioned economic quantities. They play a very relevant role in the establishment of the trade agreement. More precisely, in the context of this standard classic model, the establishment of the welfare-balanced trade agreement might be very difficult since it may change the country’s relative position in terms of production, consumption, or both.

The present study has an obvious limitation in that the international trade model under consideration is a very simplified and unrealistic one, with only two countries and one firm in each country producing the same good. On the one hand, it allows a full description of the economic quantities of the model, but it shows significant complexity driven by the interplay between these quantities. Our main conclusions and observations concern the complexity and difficulty of the prediction and analysis of international trade outcomes.

Future work can consist, for instance, in introducing some of the features mentioned above, such as studying conditions for the self-enforcing of the agreement, studying the effects of R&D investment sharing and swapping between the two firms to decrease their production costs, foreign industrial investment, merging and shutting-down of firms, the effects of subsidies, fines and other types of transfers between countries. The inclusion of some of these features into the trade agreement may be a way to overcome some of the externality effects that we discussed throughout the paper.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Filipe Martins was partially supported by CMUP, member of LASI, which is financed by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project with reference UIDB/00144/2020. Filipe Martins also thanks the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through a PhD. grant of the MAP–PDMA program with reference PD/BD/105726/2014, when this work began, and the financial support of Instituto de Matemática Pura e Aplicada—IMPA at the occasion of the 16th SAET Conference on Current Trends in Economics held in Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, where part of this work was developed and an incipient version was presented. Alberto A. Pinto thanks the financial support of LIAAD—INESC TEC and national funds through the Portuguese funding agency, FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, within project “Modelling, Dynamics and Games”, with reference PTDC/MAT-APL/31753/2017, and within project LA/P/0063/2020. Jorge Passamani Zubelli was supported by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) [grant number: E-26/202.927/2017], Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) [grant numbers: 305544/2011-0 and 307873/2013-7], and Khalifa University [grant number: FSU-2020-09].

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Francis Bloch and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments which greatly helped to improve the paper. Part of this work was performed during visits of the authors to Instituto de Matemática Pura e Aplicada (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, whose hospitality is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- McMillan, J. Game Theory in International Economics; Harwood Academic Publishers: Chur, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Haberler, G. The Theory of International Trade with Its Application to Commercial Policy; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1937; Available online: https://mises.org/library/international-trade (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Brander, J.A. Strategic trade policy. In Handbook of International Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, Chapter 27; pp. 1395–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A. Strategic aspects of trade policy. In Advances in Economic Theory; Bewley, T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; Chapter 9; pp. 329–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.J.; Brander, J.A. International R&D Rivalry and Industrial Strategy. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1983, 50, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, J.A.; Spencer, B.J. Export subsidies and international market share rivalry. J. Int. Econ. 1985, 18, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.C. Rivalry between exporting countries and an importing country under incomplete information. Acad. Econ. Pap. 2004, 32, 605–630. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Grossman, G.M. Targeted export promotion with several oligopolistic industries. J. Int. Econ. 1986, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M. Strategic export promotion: A critique. In Strategic Trade Policy and the New International Economics; Krugman, P., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Chapter 3; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W. A Theory of Managed Trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 1990, 80, 779–795. [Google Scholar]

- Helpman, E. Increasing Returns, Imperfect Markets, and Trade Theory. In Handbook of International Economics Volume I; Jones, R.W., Kenen, P.B., Eds.; North Holland Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; Chapter 7; pp. 325–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.O.; Wilson, C.A. Price competition between two international firms facing tariffs. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1995, 13, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bulow, J.I.; Geanakoplos, J.D.; Klemperer, P.D. Multimarket Oligopoly: Strategic Substitutes and Complements. J. Political Econ. 1985, 93, 488–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; Grossman, G.M. Optimal Trade and Industrial Policy Under Oligopoly. Q. J. Econ. 1986, 101, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A. International Trade Policy for Oligopolistic Industries. Econ. J. 1984, 94, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, J.A. Intra-industry trade in identical commodities. J. Int. Econ. 1981, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K. Trade restrictions as facilitating practices. J. Int. Econ. 1989, 26, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiger, R. International rules and institutions for trade policy. In Handbook of International Economics Volume III; Jones, R.W., Kenen, P.B., Eds.; North Holland Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984; Chapter 29; pp. 1495–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W. Enforcement, Private Political Pressure, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade/World Trade Organization (GATT/WTO) Escape Clause. J. Leg. Stud. 2005, 34, 471–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, K.; Staiger, R.W. An Economic Theory of GATT. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 215–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limão, N.; Saggi, K. Tariff retaliation versus financial compensation in the enforcement of international trade agreements. J. Int. Econ. 2008, 76, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Limão, N.; Saggi, K. Size inequality, coordination externalities and international trade agreements. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2013, 63, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilolo, J.M.M. Country Size, Trade Liberalization and Transfers; MPRA Paper; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kilolo, J.M.M. Country asymmetry, trade agreements, and transfers. Econ. Politics 2021, 33, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, N.; Ferreira, F.A.; Martins, J.; Pinto, A.A. An Economical Model For Dumping by Dumping in a Cournot Model. In Dynamics, Games and Science II, DYNA 2008, in Honour of Maurício Peixoto and David Rand; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics; Peixoto, M.M., Pinto, A.A., Rand, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Banik, N.; Pinto, A.A. A Repeated Strategy for Dumping. In Discrete Dynamical Systems and Applications, ICDEA 2012; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics, & Statistics; Alseda, L., Cushing, J.M., Elaydi, S., Pinto, A.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 180, pp. 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Pinto, A.A.; Zubelli, J.P. Nash and social welfare impact in an international trade Model. J. Dyn. Games 2017, 4, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R. A Primer in Game Theory; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Corchon, L.C. Trade and growth: A simple model with NOT-SO-Simple implications. J. Dyn. Games 2017, 4, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, R.; Jin, J.Y.; Troege, M. On the limits of free trade in a Cournot world: When are restrictions on trade beneficial? Can. J. Econ./Rev. Can. D’économique 2022. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrik, G.; Bobrik, P.; Sukhorukova, I. The sensitivity of commodity markets to exchange operations such as swing. J. Dyn. Games 2021, 8, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibaud, S.; Weibull, J. The dynamics of fitness and wealth distributions—A stochastic game-theoretic model. J. Dyn. Games 2022, 9, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokumacı, E.; Sandholm, W.H. Schelling redux: An evolutionary dynamic model of residential segregation. J. Dyn. Games 2022, 9, 373–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).