Abstract

Let be a non-orientable surface of genus g with n punctures and one boundary component. In this paper, we describe multicurves in making use of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, and give explicit formulae for the action of crosscap transpositions and their inverses on the set of multicurves in in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates. This provides a way to solve on non-orientable surfaces various dynamical and combinatorial problems that arise in the study of mapping class groups and Thurston’s theory of surface homeomorphisms, which were solved only on orientable surfaces before.

Keywords:

non-orientable surfaces; multicurves; geometric intersection; crosscap transpositions; mapping class group MSC:

57K20; 57M50; 57M60

1. Introduction

Mapping class groups have been one of the most extensively studied topics in low-dimensional topology for over a century since the work of Dehn. Given a surface S, the mapping class group is the group of isotopy classes of all homeomorphisms (orientation preserving if S is orientable) of S and is generated by Dehn twists in the case where S is orientable [1]. However, Lickorish [2] showed that when S is non-orientable, is not generated by Dehn twists alone but Dehn twists about two-sided simple closed curves and crosscap slides [2]; see, for instance [1,3], for the descriptions of generators of . An element of is called a mapping class. A crosscap transposition is a mapping class of a non-orientable surface represented by a homeomorphism supported on a Klein bottle minus a disk interchanging two crosscaps [3]. Because a crosscap transposition is the product of a crosscap slide and a Dehn twist, crosscap transpositions can be used instead of crosscap slides as a generator of the mapping class group [3]. When S is orientable, the natural action of on the boundary of Teichmüller space [4,5] of S (and hence on the set of multicurves on S) has been given in [4] making use of Dehn–Thurston coordinates, and in [6] making use of triangulation coordinates. However, for the case where S is non-orientable, no description of in terms of a coordinate system has been introduced so far. In this paper, we give explicit formulae (Theorem 2) for the action of crosscap transpositions and their inverses on the set of multicurves in in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, providing the first results in the literature regarding the action of a mapping class of a non-orientable surface in terms of global coordinates (by global coordinates we mean a coordinate system that describes multicurves in a unique way such as Dehn–Thurston coordinates [4,5]). The formulae can be considered as the analogue of the update rules that describe the action of the n-braid group on the set of multicurves on the n-punctured disk in terms of Dynnikov coordinates [7], which works much faster and is more direct than the usual train-track approach [4], and hence has several useful combinatorial and dynamical applications [7,8,9,10]. The analogy between the formulae in Theorem 2 and the update rules provides a way for studying such problems regarding the action of crosscap transpositions also on non-orientable surfaces in an efficient way.

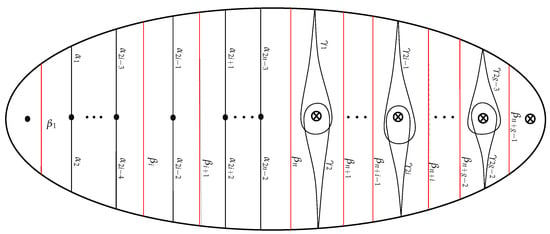

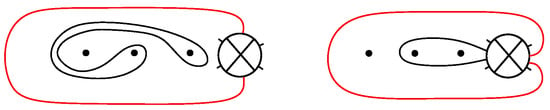

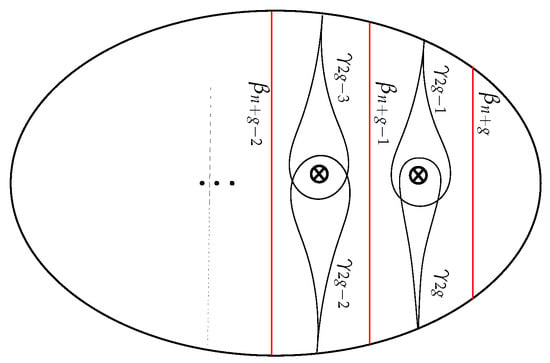

Let () be a non-orientable surface of genus g with n punctures and one boundary component. In all figures of this paper, each disk labelled with a cross on represents a crosscap, a model for a Möbius band [3,11], which is constructed by removing an open disk from the surface and identifying the antipodal points on the boundary component of the resulting disk. Throughout we shall use a standard model of as depicted in Figure 1, where the punctures and the crosscaps lie on the horizontal diameter of the surface.

Figure 1.

The arcs , , and the core curves of the crosscaps on .

We say that a simple closed curve in is essential if it does not bound an unpunctured disk, once punctured disk, or an unpunctured annulus. If a regular neighborhood of an essential simple closed curve in is an annulus, it is called 2-sided, and if it is a Möbius band it is called 1-sided. We say that a curve is a Möbius curve if it is the core curve (the 1-sided center curve of a crosscap) or a double cover of the core curve of a crosscap. A multicurve in is a disjoint union of finitely many essential simple closed curves in modulo isotopy. We write to denote the set of multicurves in .

Multicurves on orientable surfaces are usually described by techniques such as the Dehn–Thurston coordinate system or train tracks [4,5,12]. An alternative way to describe multicurves on finitely punctured disks is to use the Dynnikov coordinate system [5]. In 2016, Papadopoulos and Penner [11] provided analogues for non-orientable surfaces of several results from the Thurston theory of surfaces [5,12], including the Dehn–Thurston coordinate function. Following their work, the generalized Dynnikov coordinate system was introduced in [13] for multicurves in , which provides an explicit bijection between and a certain subset of . Here, we give a modified version of the generalized Dynnikov coordinate system together with the formulae in Theorem 1 (a corrected version of Theorem 2.14 in [13]) for the inverse of the Dynnikov coordinate function. Furthermore, with a slight modification, we also describe generalized Dynnikov coordinates for multicurves in , which was not covered in [13]. Let . The generalized Dynnikov coordinates can be described as follows:

Let be the set of arcs (), (), and () as depicted in Figure 1: the arcs and () join the i-th puncture to the boundary, the teardrops and encircle the i-th crosscap and have endpoints on the boundary, and the arc has endpoints on the boundary and passes between the i-th and -th punctures, passes between the n-th puncture and the first crosscap, and passes between the i-th crosscap and the -th crosscap. Finally, () denotes the core curve of the i-th crosscap, which we denote throughout.

Given , let L be a minimal representative of (that is, L intersects each of the arcs and curves minimally). For the sake of brevity, let , also denote the number of intersections of L with the corresponding arcs. We write if contains the i-th core curve, if contains m disjoint copies of the double cover of the i-th core curve, and if contains m disjoint copies of the double cover of the i-th core curve plus the core curve itself. Otherwise, denotes the number of intersections of L with the core curve of the i-th crosscap . It will always be clear from the context whether the symbols , and refer to arcs and curves rather than to integers. We write for the collection of these integers associated with . Let throughout the text.

Let the function be defined by

where

We say that are the generalized Dynnikov coordinates of .

Notation 1.

Let (the use of this parameter will be explained later) and .

Remark 1.

Note the special case where there is no coordinate, and the special case where there is no coordinate.

The intersection numbers (and hence the multicurve ) can be recovered from the generalized Dynnikov coordinates . Theorem 1 gives the inverse of the generalized Dynnikov coordinate function by presenting a formula that describes multicurves from given generalized Dynnikov coordinates.

Theorem 1.

Let . Then corresponds to a unique multicurve in , which has

where

Here denotes the smallest integer that is not less than x.

The main goals of this paper are first to prove Theorem 1 (correcting the proof of Theorem 2.14 in [13]) and then give the derivation of the formulae in Theorem 2 that describes how generalized Dynnikov coordinates change under the action of crosscap transpositions and (). Here the i-th crosscap transposition exchanges crosscaps and in the counterclockwise direction. Therefore, Theorem 2 computes for each mapping class written as a word of crosscap transpositions, given by We note that, although the formulae in Theorem 1 and Theorem 2 seem to have a complicated form, the method we use to obtain them is transparent as it purely relies on algebraic calculations and the properties of multicurves in terms of their associated intersection numbers . In addition, the formulae are ideally suited for computer implementation. For computational and notational convenience, we use the notations in Notation 2 and Notation 3 in Theorem 2.

Notation 2.

For computational and notational convenience, we will work in the max-plus semiring and write .

To prove Theorem 2, we shall make use of particular arc systems called clovers and scales, each of which is associated with an exceptional parameter, certain linear combinations of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, denoted and described in Section 3.

Notation 3.

For notational convenience, we write (i.e., ) in Theorem 2.

Theorem 2.

Let where is as described in Notation 1, and write and . Then , for all ; and for ; and for we have

In the special case the formulae above is interpreted as

In all other cases , and .

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives background material and contains a detailed study of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, giving proofs of Theorem 1 and Theorem 3. In Section 3, we introduce the notions of clovers and scales, certain collections of adjacent arcs in and their images under and , from which we obtain clover and scale equalities given in Lemmas 5, 9, 12 and 13, which play key roles in the derivation of the formulae in Theorem 2.

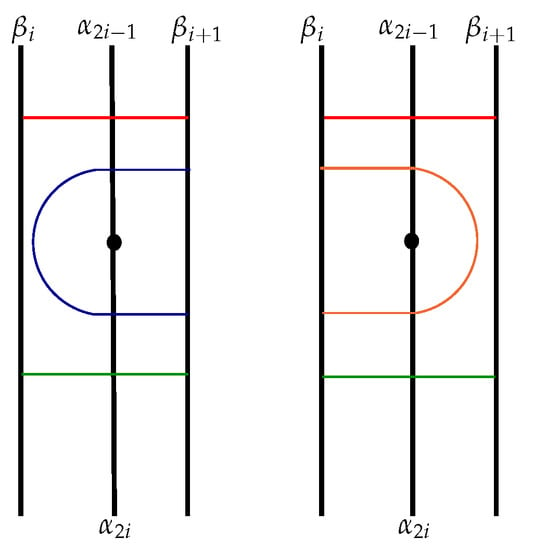

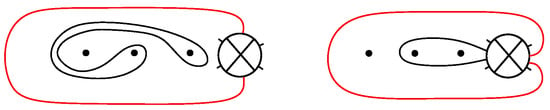

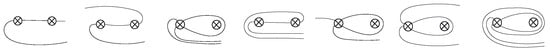

2. Constructing Multicurves from Generalized Dynnikov Coordinates

Let L be a minimal representative of . In this section we prove Theorem 1, recalling basic properties of L in terms of the intersection numbers . Let and denote the region bounded by the arcs and containing puncture . We denote by the left most region bounded by and the boundary containing the first puncture. Now, let , and denote the region bounded by the arcs and containing ; denotes the right most region bounded by and the boundary containing . Because L is minimal, there are finitely many connected components of [10] and [13], as depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Above, below, left loop, and right loop components of are depicted red, green, blue, and orange, respectively, in Figure 2. In , above, below, and straight components are depicted in red, green, and purple respectively; left core and non-core loop components are depicted in blue, and right core and non-core loop components are depicted in orange, where a loop component of is called a core loop if it intersects , and a non-core loop if it doesn’t. Finally, Möbius curves are depicted in black. Observe that there can only be left loop components in , and only right loop components in . The following lemma gives two important equalities, which are obvious from Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Connected components of .

Figure 3.

Connected components of .

Lemma 1.

Let L be a minimal representative of a multicurve with intersection numbers . Let denote the number of straight components of . Then,

Remark 2.

Given a minimal representative L of , we can initially observe that every component of L intersects each and hence each and an even number of times. Therefore , and are integers.

Lemma 2.

For each let . Then there are loop components in ( ) and loop components in (. If , the loop components are right, and if (), the loop components are left.

Proof.

We prove the statement for (the argument for is identical). Let . We first note that there cannot be both left loop and right loop components in , as the curves are mutually disjoint. Assume without loss of generality that . Observe from Figure 2 that the additional intersections on come from left loop components in , as above and below components intersect both and the same number of times. Because each left loop intersects twice, it follows that there are left loop components in . Same argument holds for right loop components in . □

Remark 3.

There are only left loop components of and only right loop components of , number of which are respectively given by and . It immediately follows that there are core loops and hence non-core loops of .

Lemma 3.

Let , and , , and denote the number of non-core loop, core loop and straight components of respectively. Then,

Proof.

If there can be no straight or core loop components of . Assume that i.e. . Observe from Figure 3 that we have

If , there exist components of other than core loop components that intersect the crosscap. Such components can only be straight components and hence and , as non-core loops and straight components cannot exist at the same time. Then, and hence by (13) and (14). If , then there exist non-core loop components as well as core loop components. That is, and hence . Therefore, and so by (13) and (14). Therefore, we get and as required. We immediately get from (14) that . □

Remark 4.

There are right loops and left loops in . Similarly, there are right loops and left loops in .

The following Lemma is obvious because each above and below component in intersects and , and each above and below component in intersects and , respectively (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Lemma 4.

Let there be and above and below components of ; and and above and below components of , respectively. Then,

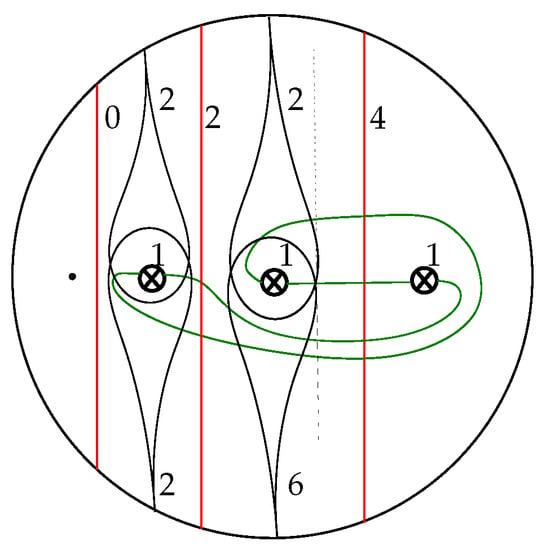

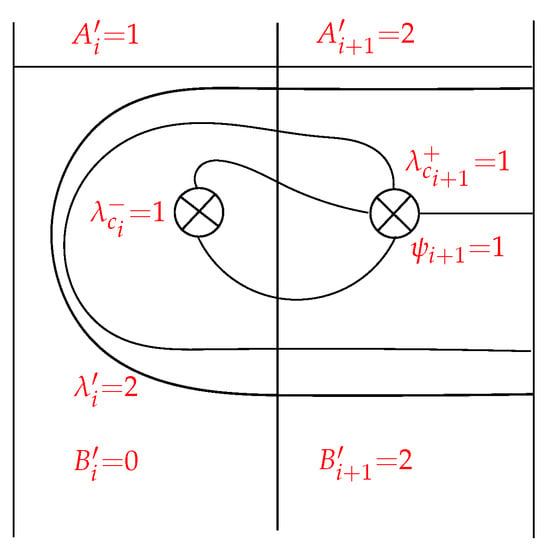

The curve in Figure 4 has generalized Dynnikov coordinates and satisfies ; . These parameters will frequently be referred to throughout the paper.

Figure 4.

A curve in with generalized Dynnikov coordinates .

The generalized Dynnikov coordinate function is a bijection: to describe its inverse, it is sufficient to describe a function from to , which sends each to the intersection numbers associated with a multicurve with . This is established in the proof of Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let L be a minimal representative of with generalized Dynnikov coordinates . We first note that and give the difference between below and above components in and , respectively, by Lemma 4. In addition, and give the number of loop components in and respectively by Lemma 2. Let and be the smaller of above and below components of and , respectively. From Figure 2 and Figure 3, it is straightforward to compute and :

For ,

For

from which we get

As is even from Remark 2, equality (20) implies that should be even. That is, is even by Lemma 3.

Now, consider a subarc of L that intersects the last crosscap exactly once, has zero intersection with the other crosscaps, and intersects the horizontal diameter of the surface only between the first puncture and the boundary exactly once, as shown in Figure 5. Each such arc intersects each and twice, and each exactly once. We say that such arcs are almost boundary parallel, and write R for the number of almost boundary parallel arcs.

Figure 5.

Two multicurves oin with .

One crucial fact is that for some or for some as otherwise there would be both above and below components in each of the and except for those that arise from almost boundary arcs, but this would mean L contains boundary parallel curves, which is impossible. Then,

When ;

When ;

When ;

When ;

Therefore, setting

we get

and hence

as required. Next, we compute R. Let

By (24), . By Remark 4, . It follows that when , we have and hence . Therefore, since almost boundary parallel arcs and non-core loop components of cannot exist at the same time, and when we have and hence and , which implies that is . Therefore, .

To compute and , we make use of the equalities in Lemma 1:

As (), we get from (25) that

If (i.e., )

If (i.e., )

That is to say:

Similarly, as for each , we get from (26) that

If (i.e., )

If (i.e., )

That is to say:

as required. □

Remark 5.

We note that the generalized Dynnikov coordinates for multicurves can be extended in a natural way to generalized Dynnikov coordinates of measured foliations. The construction is similar to the case of Dynnikov coordinates of measured foliations on finitely punctured disks [9].

Generalized Dynnikov Coordinates on

Let be the standard model of a non-orientable surface of genus g with one boundary component as shown in Figure 6, and denote by the set of multicurves on . Let . Let the function be defined by

where

Figure 6.

The arcs , and the core curves on .

Remark 6.

For , , and are as given in Lemma 3. For we have , , and . Similarly, for we have , , and as each component of and intersecting the core curves should be core loop components.

The inverse of the coordinate function is described similarly. However, we need to extend the definition of almost boundary parallel arcs, as they could also arise from the first crosscap as shown in Figure 7. That is, an almost boundary parallel arc associated with crosscap g is a subarc of L that intersects crosscap g exactly once, has zero intersection with crosscaps 2 through ; and intersects either crosscap 1 or the diameter between crosscap 1 and the boundary exactly once, as shown in Figure 7a,b. An almost boundary parallel arc associated with crosscap 1 is described similarly.

Figure 7.

Almost boundary arcs on : (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

We write and for the number of almost boundary parallel arcs associated with crosscap 1 and crosscap g, respectively. Observe from Figure 7 that there are almost boundary components in total. By the same argument as in the proof of Theorem 1, we have where

as there are no coordinates. Then, and . We have and yielding . The computation of intersection numbers on the arcs is as in the proof of Theorem 1. Therefore, we get Theorem 3 where again denotes the smallest integer that is not less than x.

Remark 7.

Note the special case where there are only and coordinates.

Theorem 3.

Let . Then corresponds to a unique multicurve in that has

where

Theorem 4.

Let have generalized Dynnikov coordinates . Let and be the generalized Dynnikov coordinates of and , respectively. Then and for ; and for and are as given in Equation (7), replacing the subscript i with ; for are as given in Equation (8) replacing the subscripts and with ; and for we have

In all other cases , and .

3. Action of Crosscap Transpositions

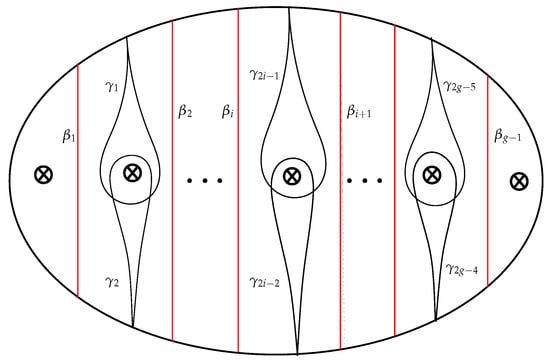

The goal of this section is to prove Theorem 2, which describes how generalized Dynnikov coordinates change under the action of and (). The key ingredient for the derivation of the formulae in Theorem 2 is a set of equalities associated with particular arc systems that we call clovers and scales. These equalities are given in Lemmas 5, 9, 12, and 13.

3.1. Clovers and Scales

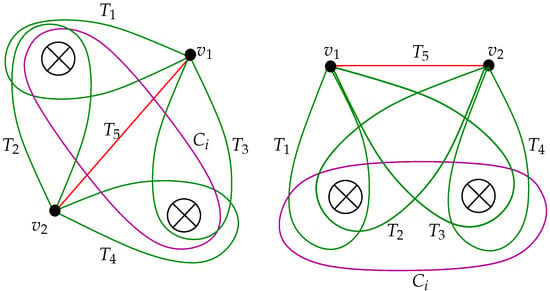

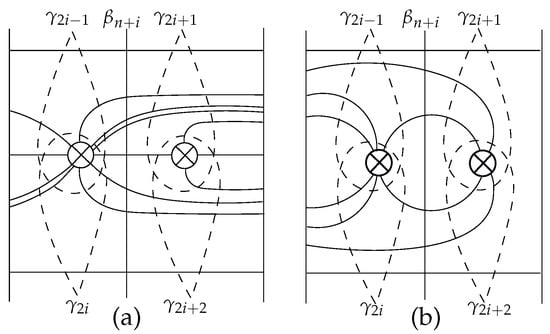

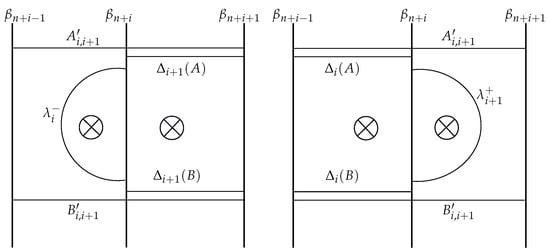

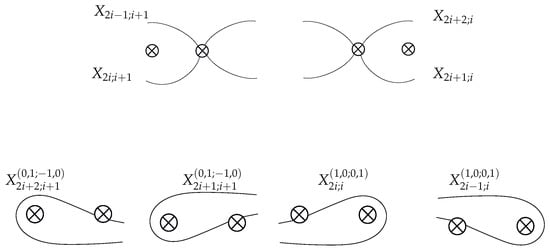

A clover and a scale about crosscaps and are two different configurations consisting of two vertices at (identified to the puncture at ∞), five arcs with end points , and a curve such that the teardrops and encircle , the teardrops and encircle , joins and ; and is the essential simple closed curve bounding crosscaps i and , as shown in Figure 8. We say that the clover has leaves, and ; diagonal arc , and diagonal curve . The scale has leaves , and , and diagonal teardrops and .

Figure 8.

A clover and a scale.

To compute the action of and its inverse () in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, we will make use of certain equalities associated with clovers and scales in , which we shall call clover and scale equalities throughout. We shall consider three types of clovers and four types of scales to obtain clover and scale equalities. These clovers and scales are depicted in Section 3.1.2 and Section 3.1.3 respectively.

Clover and scale equalities can be considered as a generalization of a well known equation commonly known as the flip move, which lets us change coordinates from one triangulation to another on punctured orientable surfaces [14]. Namely, if Q is a rectangle in a surface S and , and are the number of intersections on the four edges and the diagonals of Q with all of its corners at the punctures and containing no punctures in its interior, and denotes the number of arcs joining edge to then there are two possibilities: either or is zero, as the curves are non intersecting. This yields the well-known equation

The method here will be similar and use case by case analysis for components of intersecting the clovers and the scales. In what follows, we will again denote by L a minimal representative of a multicurve with and intersection numbers where (i.e. we omit Möbius curves).

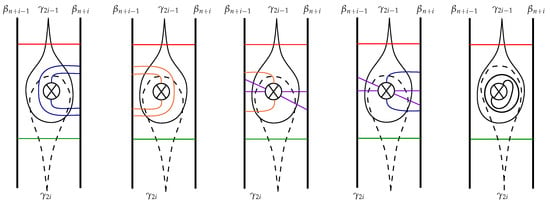

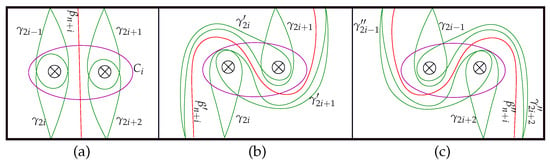

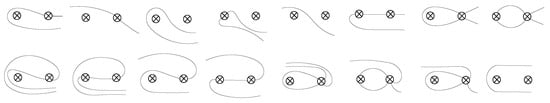

3.1.1. Components of

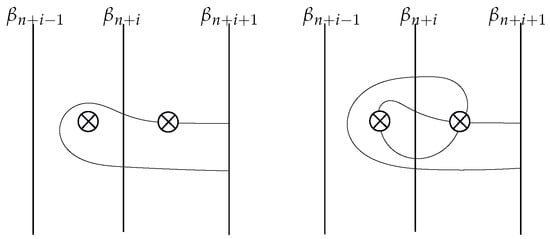

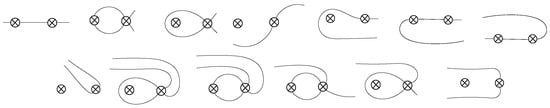

We can list all topological possibilities for connected components of (), up to isotopy, making use of their intersections with the core curves and , and the arcs () and () (and hence from their generalized Dynnikov coordinates). Let and denote crosscap i and crosscap , respectively. Given a connected component X of we associate with it a signature vector such that and give the number of intersections between X and the core curves of and , respectively, and for

where denote the number of intersections of X with .

Remark 8.

Note that each signature vector must satisfy Equation (10) of Lemma 1, and the inequality as X is a connected component of .

Then each connected component of is either a simple closed curve supported in or one of the following arcs described in Notation 4.

Notation 4.

Let and .

- :

- (a)

- If it passes above (resp. below) if (resp. ), and it passes above (resp. below) if (resp. ). It has one end point on and the other on .

- (b)

- If it passes both above and below , and it has both end points on . The case is described similarly.

- (c)

- If it passes above (resp. below) if (resp. ) and has both end points on . The case is described similarly.

- : it passes above (resp. below) if (resp. ). It has and both end points on . The cases and are described similarly.

- , , , , and : none of these components pass above or below and ; and have both end points on with and , respectively; and are described similarly; has one end point on and the other on .

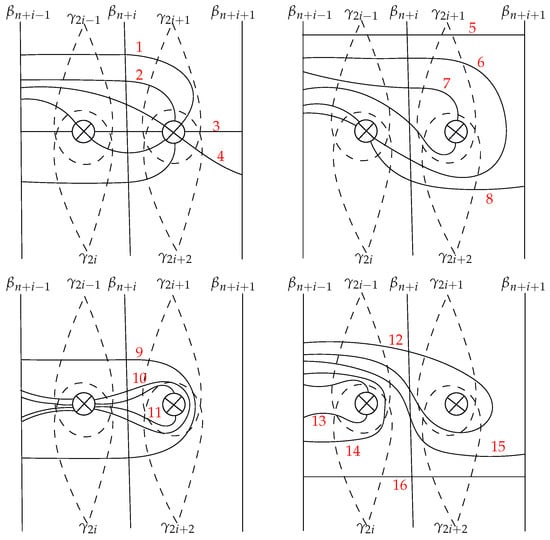

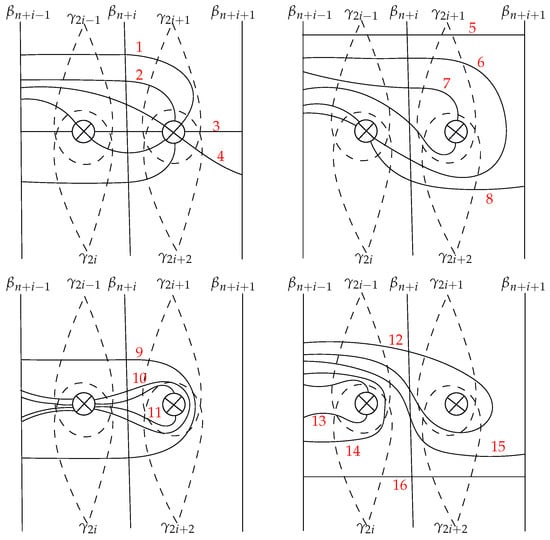

See, for example, the arcs 5, 15, 16 for item 1(a); 2, 9, 14 for item 1(b); 7, 12 for item 1(c); 1,4, 6, 8 for item 2; and 3, 10, 11, 13 for item 3 in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

Notation 5.

We shall omit the superscript for when . See, for example, the arcs 3, 4, 5, 8, 15, and 16 in Figure 9. We write for the set of simple closed curves in , and , , and for the set of arcs described in item 1, item 2, and item 3, respectively.

Notation 6.

Here and in what follows, we write to denote the arc system for convenience.

Definition 1.

Let X be a component of with signature vector . We say that X is a standard arc if at least one of and equals zero (Figure 9). We say that X is twisted if and .

Definition 2.

We say that a component of is a positive arc if it satisfies , it is negative if , and it is neutral if .

Figure 9 depicts examples of negative and neutral standard components of . Other standard components can be obtained by symmetry, reflecting them in the arc or the diameter of the surface.

Remark 9.

As and , and for a simple closed curve in , we regard each such curve neutral and twisted.

Definition 3.

A twisted component of is called a negatively (resp. positively) half twisted arc if it is the (resp. ) image of a standard arc. A negative (resp. positive) twisted component of that is not half twisted is called negatively (resp. positively) highly twisted. Each simple closed curve and twisted neutral component of is called neutrally twisted.

Notation 7.

Let denote the number of non-core loop components of (). We denote

We describe and similarly. Elsewhere denotes .

Let and be the number of above and below components of given in Lemma 4.

Notation 8.

Let and . We write

Remark 10.

Geometrically, and give the number of components of that lie entirely above and below the diameter of the surface, respectively. Therefore, and . Then, (resp. ) is the number of above (resp. below) components of that are not contained in the arcs (resp. ); and are interpreted similarly.

Figure 10 illustrates these parameters, which we will refer to later to describe other parameters.

Figure 10.

.

Remark 11.

The condition in Definition 2 implies that either or holds for a positive component. Then, is positive if or . Similarly, () is positive if or . Similar arguments hold for negative components. Similarly, the condition implies that a neutral component in item 1(a) (i.e. and ) and item 2 has (). A neutral component in item 1(b) has either and (i.e. ) or and (i.e. ).

Definition 4.

We say that two arcs in are compatible if they can be embedded disjointly in .

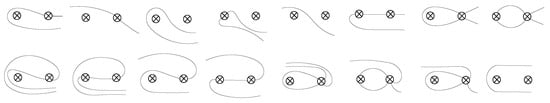

A positive and a negative arc are compatible only when they form the arc systems scissors, anchors, or ribbons.

Definition 5.

Scissors at consist of the arcs and (Figure 11a), and scissors at consist of the arcs and .

Figure 11.

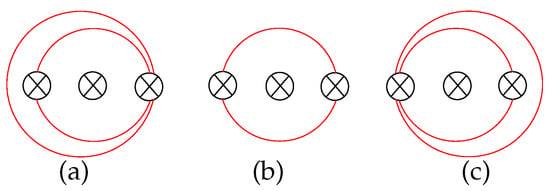

(a) Scissors at with and , (b) a left anchor with and ; (c) a left ribbon with and .

A left anchor consists of and (see Figure 11b), and a right anchor consists of and .

A left ribbon consists of arcs from the sets and (arcs of a ribbon are twisted and can have different signature vectors)(Figure 11c). A right ribbon consists of elements from the sets and . Note that scissors, ribbons, and anchors may contain multiple copies of the same arc.

The positive and negative arcs of given scissors are respectively called positive and negative arms for the scissors. For example, and are negative and positive arms of the scissors, respectively. Positive and negative arms of anchors and ribbons are described similarly.

Remark 12.

Note that scissors, anchors, and ribbons are not compatible with each other. If a component of is compatible with any scissors, anchors, or ribbons, it must be a neutral arc.

Definition 6.

If comprises standard arcs it is called standard, and if it contains at least one twisted arc it is called twisted. If it contains positive arcs possibly with neutral arcs it is called positive. The case when is negative is described similarly. If contains only neutral arcs it is called neutral, and if it contains both positive and negative arcs it is called mixed.

Therefore, is mixed if and only if it contains either scissors or an anchor or a ribbon, and that the only case where is both twisted and mixed is when it contains ribbons.

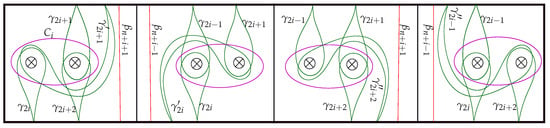

3.1.2. Clover Equalities

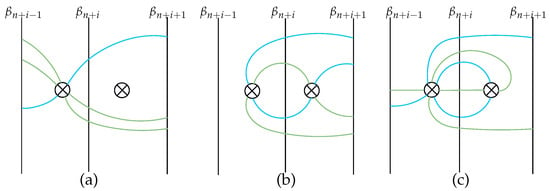

Let and . A clover of type I has leaves , , the diagonal arc , and the diagonal curve (Figure 12a). A clover of type II and a clover of type III are the images of a clover of type I under the mapping classes and , respectively, and hence are as depicted in Figure 12b and Figure 12c, respectively.

Figure 12.

(a) A clover of type I, (b) a clover of type II, and (c) a clover of type III.

We present equalities associated with a clover of type I, type II, and type III given in Lemma 5, Lemma 9, and Lemma 12, respectively. Here and in what follows we abuse notation again using the symbols in Notation 4 to denote the number of corresponding components of , and the symbols to denote the number of intersections. First, we fix some notation that will be necessary in the proof of Lemma 5.

Notation 9.

Given scissors at and scissors at let and , respectively. Given a right and a left anchor in let and , respectively. Given a left and a right ribbon in let and , respectively. Finally, let and denote the sum of all neutral arcs from the sets and , respectively, described in 1(b) in Notation 4 except for the standard components and (i.e., those with zero intersection with the crosscaps). For each we set where and .

Remark 13.

If then , and that only one of and can be different than zero by Remark 12. Similarly, if then and only one of and is nonzero.

Lemma 5

(Equality for a clover of type I). Given a clover of type I in we have

where is as given in Notation 9.

Proof.

Let , , and be the sets of neutral components of described in item 1(b) and item 3. of Notation 4, respectively. For with and , write for the set of components described in item 1(a), item 1(c), and item 2 of Notation 4, and for the set of simple closed curves supported in . By Remark 12 we have the following cases:

- Case 1:

- is either positive or negative or neutral:

- (i)

- and ;

- (ii)

- and ;

- (iii)

- and ;

- Case 2:

- is mixed, that is, either scissors or an anchor or a ribbon exists. There are two subcases:

- (i)

- and ;

- (ii)

- and ;

For Case 1 we have () because is not mixed. Suppose first that Case 1(i) holds. Then, is negative by Remark 11 and Definition 4 (see, for example, Figure 13a), and we have . First assume that is standard. It is easy to check that each negative standard component in , each curve in and each neutral component except for and satisfies

Figure 13.

(a) Case 1(i) where is standard; (b) Case 1(i) where is twisted, and (c) Case 1(iii).

Suppose that and hence (note that elements of and are not compatible). We check that satisfies , and

That is,

A similar argument holds for the case and , and we get

Equalities (37)–(39) are also satisfied for corresponding twisted components; given a standard component of with intersection numbers , , and , the twisted component has the same number of intersections on and increases the number of intersections on each and (and hence ) by the same amount determined by its signature vector (Figure 13b). Therefore, equality (37) is also satisfied for each . A similar argument holds for other twisted components. Then we have , and

as required. Case 1(ii) follows by symmetry. For Case 1(iii), we note that as consists of only neutral components and each neutral component satisfies except for and as shown above, we get either or as and are not compatible. Therefore, , and

as required.

Case 2(i) is divided into three subcases. Either contains scissors at or a left anchor or a left ribbon by Definition 5 and Remark 12. Assume that contains scissors at . Then we have , and hence where (twisted neutral components are not compatible with scissors). We obtain

as shown in Figure 14a. Observe that if and only if . Then from Equations (41) and (42) we get

as required. Similarly, if contains a left anchor, it contains no scissors, no ribbons, and no right anchor. We have and Equation (36) is verified analogously. The case when there is a left ribbon is proved similarly. Case 2(ii) is also divided into three subcases: Either contains scissors at or a right anchor or a right ribbon by Definition 5 and Remark 12 (see for instance Figure 14b). Then Case 2(ii) follows immediately from Case 2(i) by symmetry. □

Figure 14.

(a) Example for Case 2(i) and (b) example for Case 2(ii).

The proof of Lemma 5 shows that each component of except for certain arcs and arc systems satisfies

We shall call these arcs and arc systems exceptional arcs and arc systems with respect to a clover type I; and the exceptional parameter for a clover of type I.

Definition 7.

Each neutral arc in and is called an exceptional arc with respect to a clover type I at and , respectively (for example, in Figure 9, the arc labeled 2 is an exceptional arc at , whereas the arc labeled 9 is not); scissors, ribbons, and anchors in are called exceptional arc systems with respect to a clover of type I.

Let and be as described in Notation 8. The proof of Lemma 6 follows immediately from the definition of exceptional arcs and arc systems.

Lemma 6.

and if and only if there exists at least one of the following arc or arc systems in : an arc from the set , scissors at , a left anchor, or a left ribbon. Similarly, and if and only if at least one of the following exists in : an arc from the set , scissors at , a right anchor, or a right ribbon.

Then, we can compute the exceptional parameter in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates. We first give the following preliminary lemma.

Lemma 7.

Let and be as given in Notation 4. Then,

Proof.

The proof follows from Remark 10 and Figure 15 (also see [10]). □

Figure 15.

Computation for and .

Lemma 8.

Let ) be as described in Notation 9. Then where

and and are as given in Lemma 7.

Proof.

We compute ; is computed analogously reflecting in the arc . If at least one of and is equal to zero then by Lemma 6. Suppose that and .

- Case 1:

- There exists no exceptional arc system with respect to a clover type I in which case there must be exceptional arcs from the set .

- Case 2:

- There exists an exceptional arc system with respect to a clover type I, which can be either scissors at or a left anchor or a left ribbon possibly with compatible exceptional arcs from the set .

We have two subcases in Case 1: (a) and (b) . Assume that we are in Case 1(a). Then there exist negative but no positive arcs in as only negative components increase the difference by Remark 11 and that there is no exceptional arc system with respect to a clover type I in by assumption. As each element of increases and by 1, and of those are exceptional we have

(recall that is the only element of that is not exceptional). Because we get as required. Case 1(b) is proved similarly. Now assume that we are in Case 2. Assume that there exists scissors at . As the only element of that is compatible with the scissors is the standard exceptional arc , we have , and hence . By Remark 12, every other arc compatible with the scissors is neutral and has no affect on and . Therefore,

As , and we obtain

as required. In the cases when there is a left anchor and a left ribbon, we note that there may exist both twisted and standard exceptional arcs in . In addition, if there exists a left ribbon and if there exists a left anchor. Again, as each positive (resp. negative) arm of a left anchor or a left ribbon increases (resp. ) by 1, and only neutral arcs are compatible with exceptional arc and arc systems, the proof follows similarly. □

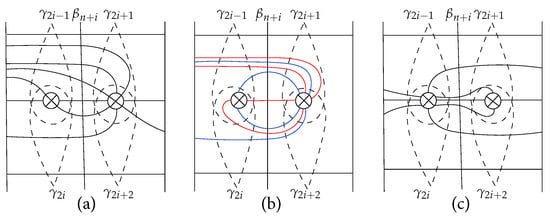

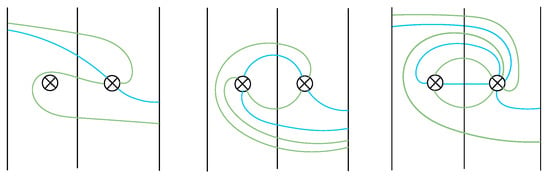

Taking the images of exceptional arcs with respect to a clover type I in , we obtain elements of and , which are called exceptional arcs with respect to a clover of type II in (Figure 16). Similarly, taking the images of scissors, anchors, and ribbons in we get negatively half twisted scissors, anchors, and ribbons, which are called exceptional arc systems with respect to a clover type II in (see Figure 17). This leads us to the equality in Lemma 9. First we introduce some notation for the parameters associated with exceptional arc and arc systems with respect to a clover type II.

Figure 16.

images of exceptional arcs of type I give exceptional arcs of type II.

Figure 17.

images of scissors, anchors, and ribbons, ordered from left to right, are exceptional arc systems with respect to a clover of type II.

Notation 10.

Let where where and denote the number of exceptional arcs of type II that are from the sets and , respectively, and

The value is called the exceptional parameter for a clover of type II.

Lemma 9

(Equality for a clover of type II). Given a clover of type II we have

where the exceptional parameter is as given in Notation 10.

We require the following parameters to compute and the other exceptional parameters in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates.

Notation 11.

Let X be a component of with . Write

Definition 8.

We define as follows:

We note that if X is neutral, for each .

Geometrically, gives information about the amount of twist of X and reveals whether X is positive, negative, or neutral by Remark 11. Observe that a standard component X of either has or . The possibilities for the latter case are given in Remark 14.

Remark 14.

Let X be standard. When X is negative, if and only if

See, for instance, in Figure 18. Similarly, when X is positive, if and only if

Figure 18.

The set .

Remark 15.

Note that a standard arc cannot be compatible with a highly twisted arc X with . Furthermore, if an arc X has , it is either a standard arc or a highly twisted arc from the sets or . A similar argument holds for an arc X with .

Definition 9.

Suppose that is not mixed. We define for by replacing X with and removing all hats from the symbols given in Notation 11.

Notation 12.

Let and be as given in Lemma 7. For notational simplicity we shall denote and

We also introduce the following components for twisted components of :

Geometrically, denotes the number of loop components of that are not contained in below components of for a twisted component of . The interpretation of the other parameters is similar.

To understand these parameters better, let us consider Figure 10 again where consists of three components: , and . Because and are neutral . Additionally, is a negative twisted component with and .

Lemma 10.

Let be negative. Then, where

Proof.

Here we only prove . The formula for is obtained similarly. We first note that each exceptional arc in and negatively half twisted scissors at , left anchor and left ribbon increases each by 1 (see Figure 16 and Figure 17). Therefore if at least one of equals zero for we get . For convenience, let us say that a subset of has property P if it satisfies , and . The proof is based on constructing all possible configurations of arcs (i.e., compatible sets) satisfying property P, and verifying that Equation (48) holds for each such collection of arcs. Let have property P. The constraint provided by property P and Remark 11 imply that each element of belongs to one of the two sets described as follows: The first set I is the subset of whose elements affect none of the values , and yet are compatible with those satisfying property P. The second set S contains negative components affecting at least one of , , . Furthermore, S is partitioned into two subsets and such that if then and X is one of the following arcs depicted in Figure 18; and if then and X is compatible with an arc with . In particular, if with it has and it is one of the arcs depicted in Figure 19; and if , it is a highly twisted exceptional arc from the set such as and , as depicted in Figure 19. Let be the family of k-element subsets of (i.e., possible configurations of exactly k arcs from the sets and ) satisfying property P. Again, by abuse of notation the symbols we use to indicate these arcs will also denote the number of corresponding arcs.

Figure 19.

The case where each arc X in has .

First, observe from Figure 16 and Figure 17 that is a standard exceptional arc with respect to a clover type II. In addition, are examples for twisted exceptional arcs and , , and form exceptional arc systems with respect to a clover type II.

- : Each component of belongs to where ; and for every other in . As to be explained later in Remark 16, we need another parameter . For simplicity, we list the 4–tuples in Table 1 corresponding to the arcs in . Observe from Table 1 that is the only element satisfying property P alone hence . Furthermore, it increases each , and by 1, yielding as required. In order to construct ), we make use of another set , which is the set of k-tuples for the compatible components where . We chose to use the star symbol here to indicate that is the only arc that is not compatible with any exceptional arc or arc system (in fact it is compatible with only , and ). We get, , whereand obtain that where

Table 1. for the arcs of .

Table 1. for the arcs of .

First consider . Recall that to compute the parameters associated with a compatible set, we simply add the corresponding components of arcs. For example, from Table 1 we compute that for . We immediately check that for each we have , and and therefore (note that taking multiple copies of arcs does not change the formula). We continue with . The set contains no exceptional arc or arc systems with respect to a clover type II, and observe from Table 1 as above that . Therefore, as required. Similarly, we check . This set contains negatively half twisted scissors (Figure 17) but no exceptional arcs hence we have . We check that and . Therefore, . Furthermore, is increased by 1 by both and . This implies yielding as required. Similarly, is a negatively half twisted left anchor (Figure 17) and hence . We check that yielding as required. Finally, none of contains an exceptional arc or arc system. Since we get yielding as expected. The formula can be verified similarly for elements of as follows.

We have where and and

Hence, where and

First consider . If we get , and the proof is similar to that of . If we get (, ). We compute from Table 1 that for each k with we have that . For we get that . Similarly for we compute that ( contains half twisted scissors ). If we have since for each corresponding ; and for we have ( contains half twisted anchor ).

Finally, for we similarly verify from Table 1 that for ; for ; for , and for . Similarly, we have where

and .

We get where

In addition, where and as there is no 5 element compatible set that does not contain but satisfies property P. And finally, . We note that there is no with . The verification of the formula for is analogous.

- 2.

- : At least a component of belongs to the set . There are two subcases depending on whether or not contains a highly twisted arc X with .

- (a)

- No component X of has : Then contains a highly twisted arc X that has (Figure 19). Let denote the set of arcs that are compatible with the arc . Then,Any compatible set containing is constructed from elements of such that property P is satisfied. Therefore, a compatible set can contain the standard exceptional arc (which is compatible with each element of ) and the twisted exceptional arcs and . The only exceptional arc system can contain is the negatively half twisted ribbon, which is the arc system . Consider, for example, the compatible sets containing . Each such set is constructed from in such a way that it contains at least one of , and so that (the other two assumptions and are satisfied by each element in ). We immediately check that for each such compatible set we have and where . Therefore, as required.

- (b)

- Some component X of has : Then , by Remark 15 as each exceptional arc system with respect to a clover type II contains a standard arc. Because by assumption, there exists a highly twisted exceptional arc (such arcs are the only highly twisted arcs with and satisfying property P), each of which increases by 1. As for any other arc compatible with X we get as required.

□

Remark 16.

The proof of Lemma 10 shows that there exists compatible sets satisfying property P yet containing no exceptional arcs or arc systems. Such arc systems either contain or the arc together with an arc that satisfies such as (note that contributes to both and ). Using parameter and subtracting from and rules out such arc systems, giving a way to compute only exceptional arcs or arc systems.

Remark 17.

Reflection in the horizontal diameter of the surface conjugates each crosscap transposition to . Therefore, a clover of type III is the reflection of a clover of type II along the horizontal diameter, and the corresponding transformation of generalized Dynnikov coordinates in max-plus notation is given by . For example, for

By Remark 17 we conclude that exceptional arcs with respect to a clover of type III can be obtained by reflecting exceptional arcs with respect to a clover of type II in the horizontal diameter. Therefore, replacing with in Notation 10, we obtain the exceptional parameter for a clover of type III as given in Lemma 11 and Lemma 12.

Lemma 11.

Let be positive. Then where

Lemma 12

(Equality for a clover of type III). Given a clover of type III we have

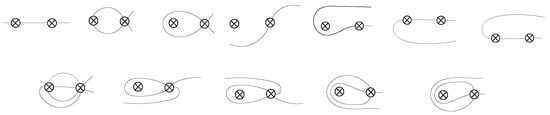

3.1.3. Scale Equalities

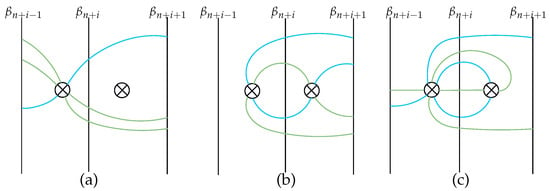

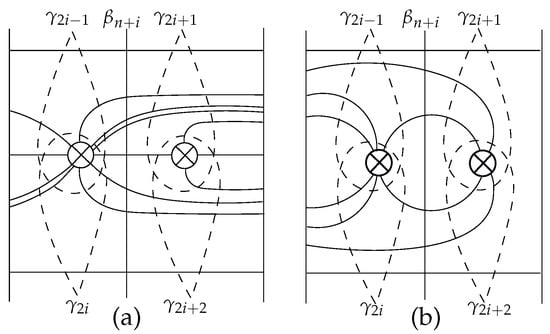

Let and . A scale of type I has leaves , , , ; diagonals and ; and a scale of type II has leaves , , , ; and diagonals and . Reflecting these two scales along the horizontal diameter we respectively obtain a scale of type III and a scale of type IV (Figure 20). Observe that this is natural, as a scale of type III and a scale of type IV are the images of a scale of type I and a scale of type II, respectively (see Remark 17).

Figure 20.

A scale of type I, type II, type III, and type IV from left to right.

Notation 13.

Let X be a component of . In what follows we shall write () to denote the number of non-core, core, and straight components of a given component X of .

The key idea in the proof of Lemma 13 is that it is easy to find out which standard arcs satisfy equalities (52), (53), (54), and (55) as there are only finitely many standard arcs to check. Similarly, we call arcs that do not satisfy equalities (52), (53), (54), and (55) exceptional with respect to a scale of type I, type II, type III, and type IV, respectively.

We say that X is straight in () if . Similarly, we say that X is –straight in if for some . The definition for –straight arc in is similar.

Analysis of exceptional arcs with respect to a scale of type I shows that each standard component X of that is not straight in (i.e., those with ) satisfies equality (52). An analogous statement for a twisted component in the class of X is also true as each such component has the same number of intersections with as X, and increases the number of intersections on each , and (and hence ) by the same amount. In addition, the only standard straight arcs in that satisfy equality (52) are and . That is, each standard straight arc in apart from and is exceptional with respect to a scale of type I (top row of Figure 21). The only twisted arcs that are straight in are in the class of () and (examples of which are as given on the bottom row of Figure 21). Each such exceptional arc X satisfies

Figure 21.

Standard arcs (top row) and examples for twisted arcs (bottom row) that are straight in .

As a scale of type III is the image of a scale of type I, it follows from Remark 17 that each arc X with apart from and is exceptional with respect to a scale of type III. For the same reason, each –straight arc X in (Figure 22) apart from and is exceptional with respect to a scale of type I (Figure 23a,b show straight and –straight arcs in which are not exceptional with respect to a scale of type I). Let us write and . Then for each –straight arc X in we get

Write and for a given .

Figure 22.

Examples for –straight arcs in .

Figure 23.

(a) Straight and (b) –straight arcs in that are not exceptional with respect to a scale of type I.

Then, setting

we obtain equality (60) given in Lemma 13. We call the exceptional parameter for a scale of type I. The exceptional arcs and hence the associated parameters for a scale of type II, type III, and type IV follow from symmetry:

Hence, computing in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates will require separate consideration of the arcs depicted in Figure 24 and given in Lemmas 14 and 15. We first state scale equalities in Lemma 13.

Figure 24.

Arcs that are used in the computation of exceptional parameters .

Lemma 13.

Lemma 14.

Proof.

We prove . The other equalities can be proved in a symmetric way. The proof is similar to the proof of Lemma 10, and is based on the following facts:

- (1)

- increases and by 1.

- (2)

- If X is compatible with then .

Therefore, by fact if or , then . Similarly, by fact if then . Suppose that and , and that , which is guaranteed by the assumption of the lemma. Let us say that an arc X has property Q if it satisfies , and , and that an arc is compatible with property Q if it is compatible with an arc that satisfies property Q. Figure 25 illustrates all arcs apart from that are compatible with property Q. As for each of these arcs by fact . □

Figure 25.

Arcs compatible with property Q.

Lemma 15.

Consider the arcs () in Figure 24. Let

Then

Proof.

We compute , which is a standard exceptional arc with respect to a clover of type II. Again, the other equalities can be proved in a symmetric way. To compute this arc separately, we need modification on the formulae given in Lemma 10 to eliminate the values , , , which are parameters related with exceptional arc systems of type II, and the number of highly twisted exceptional arcs in the set . Using the value in rules out the possibility of scissors and hence guarantees that . Similarly, as for anchors and ribbons we get . Finally, for each highly twisted exceptional arc in we have (see, for instance, and ). As increases and by one we conclude that is as given in Equation (66). □

If is mixed, by Remark 12. Otherwise they are as given in Lemma 15.

Lemma 16.

Let and () denote the number of straight components of and , respectively.

Let be negative. Then

Let be positive. Then,

Proof.

To compute the number of straight components of , we need to determine which arcs are -straight in . In order to do this, we first list all standard arcs that are straight in (there are finitely many of those) and take their inverse images under from which we obtain the arcs depicted in Figure 26. Using Notation 11, we write the following facts:

Figure 26.

-straight arcs in .

- Each -straight arc X is negative with and (i.e., X has a left core-loop in ). The converse is also true.

- equals the number of left core loops of that are entirely contained in below components of .

We have the following cases:

- If , contains , which satisfies , is not -straight and not compatible with any highly twisted component. Therefore, by (1) and (2) we obtain . It is easy to show that from which we get . Clearly, if , is some collection of arcs depicted in Figure 26, each of which satisfies by (2).

- If , contains a highly twisted component X, and only left core loops of that do not join right loop components of (i.e., those that are contained in ) can be mapped to a straight component of . That is, for each such arc we have .

□

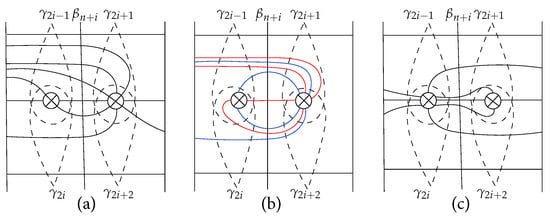

Proof of Theorem 2.

Let and denote the set of arcs in Figure 1. acts on both and , and hence for any and . We also recall that the arcs () and () are not affected by crosscap transpositions. For the crosscap transposition , our approach is to compute the number of intersections of and with instead of computing the number of intersections of with and . We have

We shall make use of clover and scale equalities given in Lemmas 5, 9, and 13. For computational convenience, we set (), (), and , , , (), and work in the max-plus semiring as indicated in Remark 2. Therefore,

and from the clover of type I equality (36),

We now consider the two separate cases of the statement.

Suppose that . Observe that for and for and . Therefore, except for and ; and except for and . Next we compute , , , and .

- We shall first compute . We have . To compute we use the scale of type I equality (60) and obtainDividing both sides of the equation by 2, we get

- We shall now compute . We have . To compute we use the scale of type II equality (61) and obtainHence, from (71) we get

- We proceed with . We have and from the clover of type II equality (47),Since andfrom which we get

- Now we shall compute . We haveTherefore, . Multiplying the numerator and denominator by gives . That is,

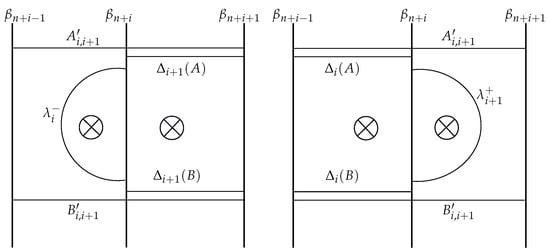

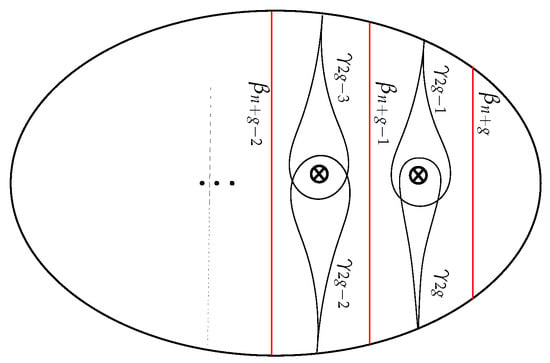

Now, suppose that (Figure 6). Observe as before that for all and for all . As there are no teardrops encircling the last crosscap, our approach to compute and is to add dummy teardrops , , and as depicted in Figure 27, which enables us to make similar calculations as in the previous statement. We first note that and hence we have and . Similar calculations give

Figure 27.

Dummy teardrops are used to compute and .

Now let . The formulae for are obtained similarly, replacing i with . For , we add two dummy punctures around the first crosscap. Similar arguments give that

For , we note that rotation through about the center of the surface conjugates each crosscap generator to , and the corresponding transformation of generalized Dynnikov coordinates in max-plus notation is given by

hence we get

By Remark 17, we obtain the rules for and for each case by symmetry, conjugating the rules for by the involution (17). □

4. Conclusions

The method introduced in this paper can be used to provide an efficient way to solve on non-orientable surfaces many combinatorial and dynamical problems that were previously solved only on orientable surfaces [4,6,9,10]. However, to solve such problems not only for sequences of crosscap transpositions but also for any element of the mapping class group, we need to describe the action of of the other generators of the mapping class group [3] on in terms of generalized Dynnikov coordinates, which require similar techniques to those introduced in this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed during a visit of the author at Columbia University as a Fulbright scholar. The author would like to thank the Fulbright Scholar Program for their support and Columbia University for their warm hospitality.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Farb, B.; Margalit, D. A Primer on Mapping Class Groups; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lickorish, B.R. Homeomorphisms of non-orientable two-manifolds. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soe. 1963, 59, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M. Mapping Class Groups of Nonorientable Surfaces. Geom. Dedicata 2002, 89, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, R.C.; Harer, J.L. Combinatorics of Train Tracks, Volume 125 of Annals of Mathematics Studies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, W.P. On the geometry and dynamics of diffeomorphisms of surfaces. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1988, 19, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, M.C. Recognising Mapping Classes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Warwick, Warwick, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dynnikov, I. On a Yang-Baxter mapping and the Dehornoy ordering. Uspekhi Mat. Nauk. 2002, 57, 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Dehornoy, P. Efficient solutions to the braid isotopy problem. Discrete Appl. Math. 2008, 156, 309–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, T.; Yurttaş, S.Ö. On the topological entropy of families of braids. Topol. Appl. 2009, 156, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, T.; Yurttaş, S.Ö. Intersections of multicurves from Dynnikov coordinates. Bull. Aust. Math. Soc 2018, 98, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Penner, R.C. Hyperbolic metrics, measured foliations and pants decompositions for non-orientable surfaces. Asian J. Math. 2016, 20, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fathi, A.; Laudenbach, F. Poenaru. In Seminairé Orsay, The V. Travaux de Thurston sur les Surfaces, Volume 66 of Astérisque; Société Mathématique de France: Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, M.; Yurttaş, S.Ö. Integral laminations on non-orientable surfaces. Turkish J. Math. 2018, 42, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, D. Geometric Intersection of Curves on Surfaces. Available online: https://dpthurst.pages.iu.edu/DehnCoordinates.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).