Abstract

In this paper, we introduce the notion of infinity branches and approaching surfaces. We obtain an algorithm that compares the behavior at the infinity of two given algebraic surfaces that are defined by an irreducible polynomial. Furthermore, we show that if two surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior, the Hausdorff distance between them is finite. All these concepts are new and represent a great advance for the study of surfaces and their applications.

Keywords:

algebraic surfaces implicitly defined; infinity branch; convergent branch; asymptotic behavior; approaching surfaces MSC:

14J29; 14J70; 14Q10; 65D17

1. Introduction

Algebraic curves and surfaces are essential entities for practical applications (see, for example [1,2]). In fact, one may find a lot of literature dealing with different problems related to curves defined by irreducible polynomials (see, e.g., [3,4]). In this paper, we introduce the concept of infinity branches for surfaces. Intuitively speaking, an infinity branch represents the behavior of an algebraic surface at the points with “sufficiently large coordinates”. Informally speaking and generalizing the situation of algebraic curves, an infinity branch is associated with a projective “place” centered at an “infinity point”, and it can be “parametrized” by means of “Puiseux series” (the formal definition of these notions can be seen in Section 2 and Section 3).

Infinity branches are necessary and essential for the study of surfaces since they reveal the behavior at a point at infinity of a real algebraic surface. For instance, the infinity branches of an implicit algebraic plane curve are an important tool to sketch its graph as well as to analyze its topology (see e.g., [5,6,7,8,9]). It should be mentioned that for the case of curves, in [10], the notion of a g-asymptote is introduced. A g-asymptote generalizes the well-known notion of linear asymptotes, and these asymptotes can be computed from the infinity branches. More precisely, we say that a curve is a generalized asymptote (or g-asymptote) of an input curve if approaches at some infinity branch. Furthermore, the input curve cannot be approached by a new curve having a lower degree. In this paper, we generalize some of these notions introduced previously for curves in [5] to the case of surfaces.

The notion of an infinity branch allows us to define convergent branches and approaching surfaces (see Section 4). More precisely, we say that two infinity branches converge if they get closer as they tend to infinity. Furthermore, an algebraic surface approaches at its infinity branch B if has another infinity branch such that is convergent with B. We obtain important results that characterize whether two algebraic surfaces are approaching.

Using these results, we obtain an algorithm that compares the the behavior of two surfaces at infinity (see Section 5). Finally, it is shown that if two algebraic surfaces defined implicitly have the same asymptotic behavior, then the Hausdorff distance between them is finite.

The results that we obtain in this paper (and also for the case of curves) are essential for some applications in the framework of computer-aided geometric design (CAGD) as, for instance, in the approximate parametrization problem (see [11]). This problem can be stated as follows: we are given a non-rational affine surface (we assume that it is a perturbation of a rational surface), and we would like to compute, if it exists, a parametrization of a new rational affine surface denoted by , which is near to the input surface. The effectiveness of the algorithm depends on the closeness of and , and then, here, one needs to show that the Hausdorff distance between V and is finite.

This paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, we present the notions and preliminaries that will be used throughout the paper. Section 3 introduces the concept of infinity branch, and here, we prove some important properties. Section 4 provides the notions of convergent branches and approaching surfaces. Additionally, we characterize whether or not two algebraic surfaces approach each other. The results presented in this section will be used in Section 5, where an algorithm to compare the asymptotic behavior of two algebraic surfaces is designed. Finally, we prove that if two given algebraic surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior, the Hausdorff distance between them is finite. We finish with a section for conclusions and future work (Section 6).

2. Preliminaries and Terminology

In the following, we present some concepts and notions that will be used throughout the paper. In particular, we introduce some previous results concerning local parametrizations and Puiseux series. For further details, one may see for instance, Section 2.5 in [3], Chapter 4 (Section 2) in [4], [12,13,14,15], etc.

We represent by the domain of formal power series in the variable t with coefficients in the field of complex numbers . That is, is the set of all the sums , . The quotient field of is the field of a formal Laurent series, which is denoted by . Every non-zero formal Laurent series can be written in the form Furthermore, the field is the field of a formal Puiseux series. By Puiseux’s Theorem, one gets that the field is algebraically closed. Observe that Puiseux series are power series with fractional exponents. Furthermore, given a Puiseux series, , one has a bound for the denominators of exponents with non-vanishing coefficients of . This bound is known as the ramification index of , and we represent it as (see [13]).

The order of a (Puiseux or Laurent) series A is the smallest exponent of a term with a non-vanishing coefficient in A. We represent it by , and we say that the order of 0 is ∞.

Let be a Puiseux series solving , , and let n be the least integer for which (i.e., ). We set , and then is a local parametrization with center at the origin. The solutions of of order 0 are places with a center on the y-axis different from the origin. The solutions of negative order are places at infinity (that is, places with center at an infinity point).

Let be a Puiseux series with . The series , are defined as the conjugates of Y, where The set of all the conjugates of Y is called the conjugacy class of Y. The number of different conjugates of Y is . Two Puiseux series provide the same place if they belong to the same conjugacy class (see [13,16]).

For the case of Puiseux power series in several variables, one may use the notation introduced in [14]. More precisely, let us fix a vector of variables , and an integer . We will use the lexicographic order on , which can be defined as follows: since we can assign to every monomial the vector of its exponents, we consider the lexicographic order of the group of monomials by writing

This extension will also be called the lexocographic order for monomials, and it is a group order. The same argument follows for the group , of monomials with vectors of exponents in .

Let be the set of all the functions ; then is an abelian group with respect to the usual addition of functions. If we fix a vector x of variables, we may write every as a formal sum where and, if , then . In this case, we set . We call the support of f the set

Finally, let us denote by the subgroup of , which is a field constructed by induction (see [14]). Under these conditions, if , then if is a well-ordered subset of for the lexicographic order. The elements of will be called generalized Puiseux power series.

In the next definition, we introduce the concept of projective local parametrization for a projective algebraic surface.

Definition 1.

Let be a projective algebraic surface defined by the homogeneous polynomial . Let be series in such that: (i) (where the three series converge), and (ii) there is no such that . Then is called a projective local parametrization of .

One can always find such a parametrization such that , and the point is called the center of .

For a given affine surface, the previous notion can be stated as follows:

Definition 2.

Let be a real algebraic surface over implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial . Let be series in such that: (i) (where the series converge), and (ii) not A and B and C, are constants. Then is called an (affine) local parametrization of . If , and the point is called the center of .

In the following, we deal with affine surfaces. The results and notions presented can be adapted easily for projective algebraic surfaces.

For our purposes, we will need a generalization of the above definition. More precisely, we will be in the conditions of Definition 2, but the place will be the center of .

Definition 3.

An equivalence class of irreducible local parametrizations of the surface is called a place of . The common center of the local parametrizations (if it exists) is the center of the place.

Now, we introduce the notion of a branch of a surface.

Definition 4.

Given a local parametrization of a surface , the set of all points obtained by allowing to vary within some neighborhood of 0 where and and converge is called a branch of .

It can be proved that two equivalent local parametrizations provide the same branch. Hence, one gets a branch for each place of the input surface.

Furthermore, the center of a local parametrization of is a point on . Reciprocally, from the following theorems, we also get that every point on is the center of at least one place of .

Theorem 1.

Let be a surface defined by . To each root of with there corresponds a unique place of with a center at the origin. Conversely, to each place of with a center at the origin, there correspond roots of , each of order greater than zero.

3. Infinity Branches

In the following, we define an infinity branch (see Definition 5), and we get some important properties which will be essential for the results we will obtain.

For this purpose, let be an algebraic affine surface over implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial . Let be its corresponding projective surface defined by the homogeneous polynomial . In addition, let , where be a local parametrization of an infinity curve of implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial that divides (see Definition 2). Observe that , and by abuse of notation, we refer to as an infinity point of the input surface .

We compute the series expansion for the solutions of w.r.t in some neighborhood of . We obtain solutions given by different Puiseux series that can be grouped into conjugacy classes. Let one of these solutions be given by the Puiseux series :

where, for , , , , , and the lexicographic order for monomials is considered. We have that in some neighborhood of where converges. Then, there exists some such that

where and which implies that

for and . We set , and we obtain that

where

for .

Since , we get that there are different series in its conjugacy class (with respect to the variable ). Let be these series, and

where are the complex roots of . Similarly, one reasons for . Now, we introduce the notion of an infinity branch.

Definition 5.

The set where

is called an infinity branch of the affine surface . The subsets are called the leaves of the infinity branch B.

Remark 1.

- Note that, up to conjugation, an infinity branch is uniquely determined from one leaf. That is, if , where , andthen , up to conjugation; i.e.,where , and . Similarly, one reasons for .

- Let . In the following, we consider .

Let be a series expansion for a solution of . We consider and we observe that is a local projective parametrization, with a center at , of the projective surface .

Thus, from ( are the different series in the conjugacy class of ). We obtain equivalent local projective parametrizations, (note that they are equivalent since belong to the same conjugacy class). Therefore, the leaves of B are all associated to a unique infinity place.

Conversely, from a given infinity place defined by a local projective parametrization , we obtain Puiseux series, , , that provide different expressions . Hence, the infinity branch B is defined by the leaves

From the previous disquisitions, we conclude that there exists a one-to-one relation between infinity places and infinity branches, and we may say that each infinity branch is associated with a unique infinity point (which is given by the center of the corresponding infinity place). Reciprocally, from the previous construction, we obtain that every infinity point has associated, at least, one infinity branch. Thus, every algebraic surface has, at least, one infinity branch. Furthermore, every algebraic surface has a finite number of branches.

The above process can be applied to an infinity point of the form that provides a local parametrization of an infinity curve. For the case that , we may reason similarly by considering the surface implicitly defined by the polynomial . Observe that where , is a local parametrization of an infinity curve of implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial that divides . In this case, , and by abuse of notation, we refer to as an infinity point of the input surface. In this situation, we get that there exists such that

for and , where for

, , (and the lexicographic order for monomials is considered) is a series expansion for a solution of with respect to in some neighborhood of . We set , and we get that

where for .

Thus, we obtain an infinity branch whose leaves have the form:

Observe that we may apply this construction to any infinity point of the form .

Finally, for the case , we may consider the surface implicitly defined by the polynomial . Observe that where , is a local parametrization of an infinity curve of implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial that divides . In this case, , and by abuse of notation, we refer to as an infinity point of the input surface. In this situation, we get that there exists such that

for and , where for

, , (and the lexicographic order for monomials is considered) is a series expansion for a solution of . We set and we get that

for .

Thus, we obtain an infinity branch whose leaves have the form:

Observe that we may apply this construction to any infinity point of the form .

Definition 6.

Let be an affine surface over defined by an irreducible polynomial .

- An infinity branch of of type 1 associated with the infinity point is a set , where , , , and are the conjugates of(similarly for );

- An infinity branch of of type 2 associated with the infinity point is a set , where , , , and are the conjugates of(similarly for );

- An infinity branch of of type 3 associated with the infinity point is a set , where , , , and are the conjugates of(similarly for ).

Remark 2.

- In the following, we work with the type 1 infinity branches of a given algebraic surface . Similarly, one can reason for the other infinity branches;

- We will say that is the ramification index of the branch B with respect to , and we will write it as . Note that B has leaves.

In the following examples, we compute the infinity branches for some given surfaces.

Example 1.

Let be the a surface implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial

The corresponding projective surface is defined by

Note that is an infinity point of .

We determine the infinity branches associated with P. For this purpose, we consider the curve defined by the irreducible polynomial , and we observe that where is a rational parametrization of the curve defined implicitly by . Note that in this case, we have more than a local parametrization of but a rational parametrization of .

Now, we compute the series expansion for the solutions of with respect to around . In this case, since is rational over , we compute a parametrization and we get that:

Observe that , and . Note that , which implies that we only have one Puiseux series in the conjugacy class of . Thus, we obtain one infinity branch:

Example 2.

Let be the surface implicitly defined by the irreducible polynomial

The corresponding projective surface is defined by

Note that and are the two infinity points of . We determine the infinity branches associated with and . For this purpose, we consider the curve defined by , and we observe that where . Note that in this case, we have more than a local parametrization of but a rational parametrization of .

Now, we compute the series expansion for the solutions of with respect to around . In this case, is not rational over ; thus, we compute a local parametrization, and we get two different solutions:

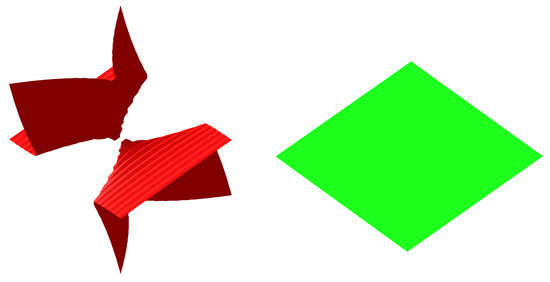

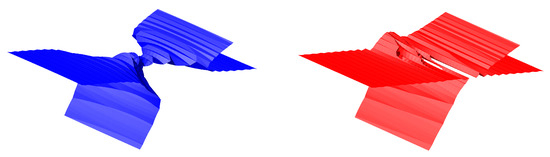

- First, we get that , whereObserve that , and . Note that , which implies that we only have one Puiseux series in the conjugacy class of . Thus, we obtain one infinity branch:In Figure 1, we plot the surface and a surface, , constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (see Section 4);

Figure 1. Surface (left), and surface (right).

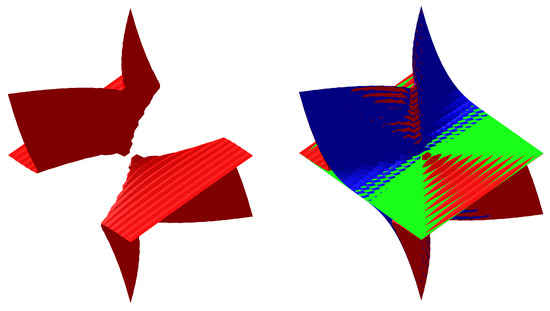

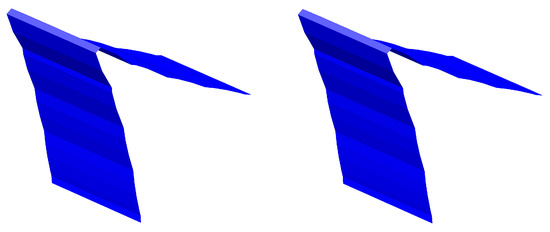

Figure 1. Surface (left), and surface (right). - We also get that , whereObserve that , and . Note that , which implies that we only have one Puiseux series in the conjugacy class of . Thus, we obtain one infinity branch:In Figure 2, we plot the surface and a surface, , constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (see Section 4). In Figure 3, we plot the surface and the surfaces and together.

Figure 2. Surface (left), and surface (right).

Figure 2. Surface (left), and surface (right). Figure 3. Surface (left), surface and surfaces and (right).

Figure 3. Surface (left), surface and surfaces and (right).

Remark 3.

The computation of is not an easy question. In some cases, this problem can be easily solved as in Examples 1 and 2. For a more general cases, and also for the case of surfaces parametrically defined, we will deal with this question in a future work.

In the following, we prove that any point of the surface with sufficiently large coordinates belongs to some infinity branch. For this purpose, we recall that if h is a complex-valued function of a complex variable, , we say that the limit of as approaches ∞ is L, written . If whenever is a sequence of points with , it holds that (see, e.g., [17] or [18]).

Lemma 1.

Let be an algebraic surface. There exists such that for every with , it holds that , where is an infinity branch of .

Proof.

Let us assume that the lemma does not hold, and we consider a sequence such that . Then, for every , there exists a point such that , and does not belong to any infinity branch of .

Let . Since , then . Thus, we distinguish the following different cases:

- (a)

- If there exist two not-bounded monotone subsequences, and , we have thatand then and Hence, where , which implies that is an infinity point of ;

- (b)

- If there exist a not-bounded monotone subsequence and a bounded monotone subsequence , we have that and , and then and (if ). Hence,where , which implies that is an infinity point of .Note that if , then we consider . Hence,where , which implies that is an infinity point of ;

- (c)

- If there exist two bounded monotone subsequences and , we have that and(if ). Thus,where , which implies that is an infinity point of .If , that is, , since (we assume that ), we get that . Thus,where , which implies that is an infinity point of .If , that is, , then or . Let us assume that . Then, since , we get thatwhere , which implies that is an infinity point of .

- (d)

- If there exist a bounded monotone subsequence and a not-bounded monotone subsequence , we have thatandThus,where , which implies that is an infinity point of .Note that if , then since , we get that . Thus,where , which implies that is an infinity point of .

From both situations, we deduce that there exists a sequence that approaches to an infinity point P as n tends to infinity; i.e., there exists such that for . Therefore, one may conclude that can be determined by a place centered at P. Thus, belongs to some infinity branch of , which contradicts the hypothesis. □

Remark 4.

Reasoning as in Lemma 1; one gets that there exists satisfying that for every , , it holds that , where is an infinity branch of . The reasoning is similar if .

4. Convergent Branches and Approaching Surfaces

In the following, we define convergent branches and approaching surfaces. We say that two infinity branches converge if they get closer as they tend to infinity. This notion will allow us to analyze whether two surfaces approach each other at the infinity.

The results obtained in this section will be used in Section 5. In Section 5, we present a method that compares the asymptotic behavior of two surfaces implicitly defined.

Definition 7.

Given two leaves, and , we say that they are convergent if for .

Lemma 2.

Two leaves and are convergent if and only if the monomials on the variable that have a non-negative exponent in the series and are the same (for ).

Proof.

Let

, and

. Then,

Note that if and only if has no monomials having a non-negative exponent. This situation holds if the monomials on the variable that have a non-negative exponent in both series, and , are the same.

One reasons similarly for and . □

Remark 5.

- From Lemma 2, we deduce that and then, L and are associated with the same infinity point;

- Note that the number of monomials with regard to that have a positive exponent in both series is finite.

Definition 8.

Two infinity branches, B and , are convergent if there exist two convergent leaves and .

Remark 6.

Statement 1 in Remark 5 implies that two convergent infinity branches are associated with the same infinity point.

Proposition 1.

Two infinity branches B and are convergent if and only if for each leaf there exists a leaf convergent with L, and reciprocally.

Proof.

The proof follows reasoning similarly as in Proposition 4.6 in [5]. □

Remark 7.

Two convergent infinity branches may have different ramification indexes; that is, they may have different numbers of leaves. However, , which is obtained by simplifying the non-negative exponents in the variable , is the same in both branches. We refer to it as the degree of the infinity branch with respect to . Note that from the proof of Proposition 1, we get that two convergent infinity branches have the same degree with respect to .

Two convergent infinity branches may be contained in the same surface or they may belong to different surfaces. In this second case, we will say that those surfaces approach each other. In order to define this concept in a more formal way, we first introduce the following distance:

Definition 9.

Given an algebraic surface over and a point , we define the distance from p to as

Remark 8.

We should note that since is a closed set, this minimum exists.

Definition 10.

Let be an algebraic surface over with an infinity branch B. We say that a surface approaches at its infinity branch B if there exists one leaf such that

We will show that this condition is satisfied for one leaf of B if and only if it is satisfied for every leaf of B. It will be derived as a consequence of the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Let be an algebraic surface over with an infinity branch B. An algebraic surface approaches at B if and only if has an infinity branch, , such that B and are convergent.

Proof.

The proof follows reasoning similarly as in Theorem 4.11 in [5]. □

Remark 9.

- Theorem 2 implies that “proximity” is a symmetric relation. More precisely, the surface approaches the surface at some infinity branch B if and only if approaches at some infinity branch . In the following, we say that and approach each other or that they are approaching surfaces ;

- From Theorem 2 and Remark 6, we get that two approaching surfaces have a common infinity point;

- Theorem 2 and Proposition 1 imply that approaches at an infinity branch B if for every leafit holds that

Corollary 1.

Let be an algebraic surface with an infinity branch B. Let and be two different surfaces that approach at B. Then, and approach each other.

Proof.

From Theorem 2, there exist two infinity branches and , convergent with B. Thus, for each leaf , there exist two leaves and such that and . Then

(one reasons similarly for ). Therefore, and approach each other. □

In Example 3, we illustrate the above results.

Example 3.

Let and be two surfaces implicitly defined by the polynomials

respectively. Let us prove that and approach each other at the infinity branch associated with the infinity points

(note that both surfaces have and as infinity points). Reasoning as in Example 2, we get that the infinity branch of associated with is given by

where

The infinity branch of associated with is given by

where

On the other hand, the infinity branch of associated with is given by

where

The infinity branch of associated with is given by

where

From Lemma 2, we conclude that both branches converge, since the terms with non-negative exponent in both series, and , are the same.

Remark 10.

In the above example, the surfaces and are approaching surfaces, since approaches at one of its infinity branches reciprocally.

In fact, approaches at all of its infinity branches and reciprocally. In this case, we say that both surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior. We focus on this special relation in the next section.

5. Asymptotic Behavior

From the results obtained previously, we obtain an algorithm that compares the asymptotic behavior of two surfaces implicitly defined. Two surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior if they approach each other at all of the infinity branches. Furthermore, we show that if two algebraic surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior, the Hausdorff distance between them is finite.

The algorithm developed, as well as the results presented in this section, provide essential tools in the frame of practical applications in computer-aided geometric design (CAGD) such as, for instance, the problem of the approximate parametrization (see Section 1).

To start with, we first introduce the following definition.

Definition 11.

We say that two algebraic surfaces, and , have the same asymptotic behavior if every infinity branch of converges to another branch of and does so reciprocally.

Remark 11.

From Theorem 2, we get that and have the same asymptotic behavior if approaches at all its infinity branches and does so reciprocally.

Now, we recall the notion of Hausdorff distance.

Definition 12.

Given a metric space and two subsets , the Hausdorff distance between them is defined as:

If and d is the Euclidean distance, the Hausdorff distance between two surfaces and can be expressed as:

Proposition 2.

Let and be two algebraic surfaces having the same asymptotic behavior.

Then, the Hausdorff distance between them is finite.

Proof.

The proof follows reasoning similarly as in Proposition 5.4 in [5]. □

The following algorithm allows us to compare the asymptotic behavior of two surfaces and .

We assume that we have prepared and such that by means of a suitable linear change of coordinates (the same change applied to both surfaces), is not a curve of infinity of and .

In Example 4, we illustrate the performance of Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Asymptotic Behavior. |

|

Example 4.

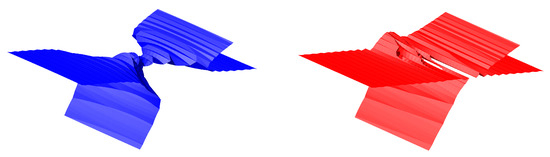

Figure 4.

(left) and (right).

We apply Algorithm 1 to decide whether and have the same asymptotic behavior:

- Step 1: Compute the infinity points of and . We obtain that and have the same infinity points that correspond to the curves defined implicitly by and .We start by analyzing the infinity branches associated with :

- Step 2.1: We reason similarly as in Example 1, and we get that the only infinity branch associated with in is given by

- Step 2.2: We also have that there exists only one infinity branch associated with these curves of infinity in . It is given by

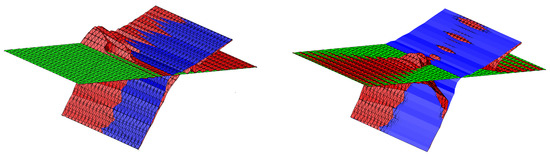

- Step 2.3 and Step 2.4: and have the same terms with a non-negative exponent with respect to . Thus, and converge.In Figure 5, we plot the surfaces constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (left), we plot the surfaces constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (right).

Figure 5. Surface (left), and surface (right).Now we analyze the infinity branches associated with :

Figure 5. Surface (left), and surface (right).Now we analyze the infinity branches associated with : - Step 2.1: Reasoning as in Example 1, we get that the only infinity branch associated with in is given by

- Step 2.2: The only infinity branch associated with in is given by

In Figure 6, we plot the surfaces constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (left), and we plot the surfaces constructed from the infinity branch that approach the input surface (right).

Figure 6.

Surface (left), and surface (right).

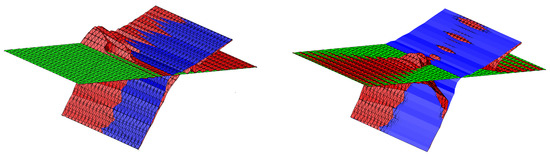

- Step 2.3 and Step 2.4: and have the same terms with non-negative exponent s with regard to . Thus, and converge.

Since every infinity branch of converges to another branch of , and reciprocally, the algorithm returns that and have the same asymptotic behavior.

In Figure 7, we plot the surfaces and together (left), and the surfaces and together (right).

Figure 7.

Surfaces and (left), and surfaces and (right).

Remark 12.

- Once we have the infinity branches, we can compute surfaces having the same asymptotic behavior as the given surface at each of the infinity points. For this purpose, one simply has to remove the terms with negative exponents in the variable from and . However, this problem, which will be dealt with in a future work, has to be carefully analyzed. Note that if we remove terms with negative exponents in the variable , we could be removing necessary terms in the variable ;

- If we remove the terms with negative exponents in the variable from the series and defining the branch B, we obtain . In a future work, we will analyze whether one may compute the surface defined by the local parametrizationIn this case, and would have the same asymptotic behavior at B;

- For the computation of the series we are considering and solving z by using Puiseux series (see Examples 1 and 2). This is not the best solution for some surfaces, and thus, this question should be deeply analyzed in a future work (see Remark 3).

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduce the notion of infinity branches and approaching surfaces for the case of a given algebraic surface implicitly defined. From these notions and the obtained properties, we present an algorithm that compares the behavior at the infinity of two algebraic surfaces defined implicitly. As a consequence and taking into account the case of curves (see [5]), we prove that if two algebraic surfaces have the same asymptotic behavior, the Hausdorff distance between them is finite.

As in the case of curves, this first paper opens some important questions that should be answered. In particular, the computation of surfaces having the same asymptotic behavior as the given surface at each of the infinity branches, the definition of a perfect surface, and the properties as well as the computation of the generalized asymptotes for implicitly and parametrically defined surfaces are important points that should be analyzed in a future work (see [10]).

Finally, we should remind the reader that, as we state in Remark 12, for the computation of the series we are considering and solving z by using Puiseux series (see Examples 1 and 2). This is not the best solution for some surfaces, and thus, this question for the general case (and also for the case of surfaces defined by a rational parametrization) should be deeply analyzed in a future work (see Remark 3).

Author Contributions

E.C.-M., M.F.d.S. and S.P.-D. contributed equally to this work and they worked together through the whole paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades—Agencia Estatal de Investigación/ PID2020-113192GB-I00 (Mathematical Visualization: Foundations, Algorithms and Applications).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author S. Pérez-Díaz belongs to the Research Group ASYNACS (Ref. CT-CE2019/683).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hoffmann, C.M.; Sendra, J.R.; Winkler, F. Parametric Algebraic Curves and Applications. J. Symb. Comput. 1997, 23, 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoschek, J.; Lasser, D. Fundamentals of Computer Aided Geometric Design; Peters, A.K., Ed.; Wellesley Ltd.: Wellesley, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sendra, J.R.; Winkler, F.; Perez-Diaz, S. Rational Algebraic Curves: A Computer Algebra Approach; Series: Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.J. Algebraic Curves; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, A.; Pérez-Díaz, S. Asymptotic behavior of an implicit algebraic plane curve. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2014, 31, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Chen, Y. Finding the Topology of Implicitly defined two Algebraic Plane Curves. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2012, 25, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vega, L.; Necula, I. Efficient Topology Determination of Implicitly defined Algebraic Plane Curves. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2002, 19, 719–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. An Effective Method for Analyzing the Topology of Plane Real Algebraic Curves. Math. Comput. Simul. 1996, 42, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G. Computing the Asymptotes for a Real Plane Algebraic Curve. J. Algebra 2007, 316, 680–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, A.; Pérez-Díaz, S. Asymptotes and Perfect Curves. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2014, 31, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez–Díaz, S.; Sendra, J.; Sendra, J.R. Parametrization of Approximate Algebraic Surfaces by Lines. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2005, 22, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrovic, D.; Verschelde, J. Computing Puiseux Series for Algebraic Surfaces. In Proceedings of the 37th International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (ISSAC 2012), Grenoble, France, 22–25 July 2012; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, D. Rational Puiseux Expansion. Compos. Math. 1989, 70, 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, M.J.; Vicente, J.L. The Newton Procedure for several variables. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2011, 435, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmeyer, P. On the Computational Complexity of Resolving Curve Singularities and Related Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, The Johannes Kepler University Linz, Linz, Austria, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Verger-Gaugry, J.-L. Beta-Conjugates of Real Algebraic Numbers as Puiseux Expansions. Integers: Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory. In Proceedings of the Leiden Numeration Conference, Leiden, The Netherlands, 7–18 June 2010; Volume 11B. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlfors, L.V. Complex Analysis, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.B. Functions of One Complex Variable I. Graduate Texts in Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).