Abstract

The spherical search algorithm is an effective optimizer to solve bound-constrained non-linear global optimization problems. Nevertheless, it may fall into the local optima when handling combination optimization problems. This paper proposes an enhanced self-adapting spherical search algorithm with differential evolution (SSDE), which is characterized by an opposition-based learning strategy, a staged search mechanism, a non-linear self-adapting parameter, and a mutation-crossover approach. To demonstrate the outstanding performance of the SSDE, eight optimizers on the CEC2017 benchmark problems are compared. In addition, two practical constrained engineering problems (the welded beam design problem and the pressure vessel design problem) are solved by the SSDE. Experimental results show that the proposed algorithm is highly competitive compared with state-of-the-art algorithms.

Keywords:

differential evolution; opposition-based learning; spherical search algorithm; staged search mechanism MSC:

49-04

1. Introduction

In the field of science and engineering, single-objective optimization problems are often characterized as discontinuities, multi-variable, and non-differentiable [1,2,3,4]. Solutions to these optimization problems are divided into local optima and global optima. Some algorithms may be trapped in local optima and cannot find the global optima, while other algorithms can find the global optima [5]. Deciding how to design an algorithm that can find the global optima for an optimization problem more efficiently has become a hot research topic [6].

In the literature, there are usually two ways to solve optimization problems. One is to use deterministic methods and the other is to employ stochastic algorithms. Most deterministic methods find solutions by utilizing derivative information of the objective functions [7,8,9]. However, not all problems’ objective functions are differentiable. Examples are economic dispatch problems [10,11], unit commitment problems [12], electromagnetic optimization problems [13], job shop problems [14], industrial scheduling problems [15,16,17,18], and disassembly line balancing problems [19,20,21,22,23]. As a result, stochastic optimization algorithms have received a lot of attention recently [24,25,26,27]. These algorithms do not require objective functions to be differentiable, instead, they use the ability of exploration and exploitation to search multiple randomly selected spaces [28]. Specifically, during the exploration, the goal is to explore a promising region in the search space, and for exploitation, the goal is to excavate the previous promising region carefully.

Over the past few decades, researchers have designed many stochastic optimization algorithms by mimicking the lifestyles or activities of natural creatures. Some well-known algorithms, such as the genetic algorithm (GA) [29], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [30], differential evolution (DE) [31], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [32], grey wolf optimizer (GWO) [33], artificial bee colony optimization (ABC) [34], salp swarm algorithm (SSA) [35], polar bear optimization (PBO) [36], moth-flame optimization algorithm (MFO) [37], and dragonfly algorithm (DA) [38] have been proposed. In addition, some researchers have also improved the performance of stochastic optimization algorithms. Rizk-Allah et al. [39] integrated the ant colony optimization and firefly algorithm, and firefly worked as a local search to refine the positions found by the ants. Liang et al. [40] proposed a comprehensive learning PSO to improve the global search ability of PSO. Ghosh et al. [41] presented a novel, simple, and efficient mutation formulation by archiving and reusing the most promising difference vectors from past generations to disturb the base individual. Singh et al. [42] presented WOA–differential evolution and genetic algorithm (WOADEGA), appending DE and GA with WOA, and solved the unit commitment scheduling problem. Sumit et al. [43] proposed and investigated a novel, simple, and robust decomposition-based multi-objective heat transfer search for solving real-world structural problems. Betul et al. [44] proposed a new metaheuristic dubbed as the chaotic lévy flight distribution algorithm, to address physical world engineering optimization problems that incorporate chaotic maps in the elementary lévy flight distribution. In addition, a novel hybrid metaheuristic algorithm [45] based on the artificial hummingbird algorithm and simulated annealing problem is proposed to improve the performance of the artificial hummingbird algorithm. The reason for the new variety of stochastic algorithms is out of the no free lunch (NFL) theorem [46], which points out that no single algorithm can perfectly solve all optimization problems.

A spherical search (SS) algorithm [47] was introduced by Kumar, Das, and Zelinka in 2019. To solve global optimization problems more efficiently, a self-adaptive spherical search algorithm (SASS) is proposed [48]. The SASS is a swarm-based meta-heuristic algorithm and has been applied in solving non-linear bound-constrained global optimization problems. SASS has a rigorous mathematical derivation process, and it exhibits some good characteristics similar to other popular algorithms. For example, it is swarm-based; it checks for the stop condition; it has no special requirements for objective functions; and it is not restricted to specific issues. SASS uses a successful history-based parameter adaptation tuning procedure, which enhances the performance of the algorithm.

As an optimization algorithm proposed in recent years, the SASS has the following advantages: (a) a few parameters that need to be debugged, (b) strong exploitation capacity, and (c) high diversity during the search process [48]. However, due to the weak exploration ability of the SASS, it is easy for the algorithm to fall into local optimal in the late iteration [49]. The motivation of this work is to enhance the exploration capability of the SASS so that the algorithm can better balance global exploration and local mining throughout the search process. Thus, in this paper, we propose an enhanced self-adaptive spherical search algorithm with differential evolution (SSDE). The contributions of this paper are as follows:

- The opposition-based learning strategy is used in the initialization phase, which can enhance the quality of the initial solution.

- To balance the exploration and exploitation of the algorithm in the search process, we divide the whole search process into three stages. In addition, we propose three search strategies, with individuals using different search strategies at different stages.

- To effectively prevent the algorithm from falling into local optimal, we propose a non-line parameter.

- According to the mutation strategy in DE, we propose a new mutation strategy. The mutation strategy can help the algorithm achieve a faster convergence speed and find the optimal solution more effectively.

- Experimental results on 29 functions from the standard IEEE CEC 2017 test functions and four constrained practical engineering problems show that the performance of the SSDE is significantly superior to SASS and other state-of-the-art algorithms.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the original SS and the SASS. Section 3 describes the issues with SASS and presents the novel SSDE. Experiments testing the performance of the SSDE are discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes this paper and discusses future work.

2. Spherical Search Algorithm

2.1. Original Spherical Search Algorithm

The spherical search (SS) algorithm is a swarm-based meta-heuristic proposed to solve non-linear bound-constrained global optimization problems [47]. In the SS, the search space is represented in the form of vector space in which the location of each individual is a position vector representing a candidate solution to the problem.

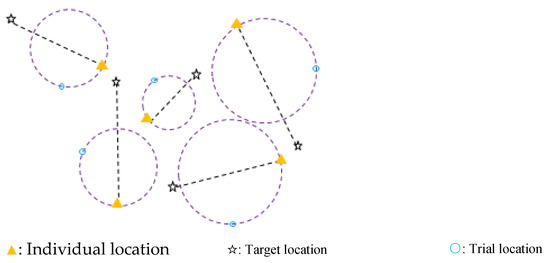

In a D-dimensional search space, for each individual, before generating its trial location, spherical boundaries are created in advance depending on the individual’s destination direction in every iteration. Here, the destination direction is the main axis of the spherical boundary, and the individual lies on the surface of the spherical boundary [47]. An example of a two-dimensional search space is depicted in Figure 1. The spherical boundary for each individual is drawn as “–”, the target location is drawn as “☆”, and each spherical boundary is generated using the axis obtained by the individual locations and the target locations. Trial solutions appear on the spherical boundary. Thus, in each iteration, the trial location for each individual is generated on the surface of the spherical boundary.

Figure 1.

Demonstrating the spherical (circular) boundary of the SS in a two-dimensional search space.

In the SS, the initial population is randomly generated in the search space. Let

where is the population at the kth iteration, N is the number of individuals, and is the value of the jth element (parameter) of the ith solution. At the kth iteration, is initialized as follows:

where xuj and xlj represent the upper and lower bounds of the jth constituent, respectively.

In the SS, the following equation is used to generate a trial solution corresponding to the ith solution.

where is a projection matrix, which decides the value of on the spherical boundary [47], is a step-size control parameter. At the start of the kth iteration, the value of is selected randomly in the range of [0.5, 0.7] [47]. represents the search direction. The SS calculates the search direction in two ways, namely towards-rand and towards-best. With towards-rand, the search direction for the ith solution at the kth iteration is calculated by using the following equation:

While with towards-best, the search direction is calculated as:

In Equations (5) and (6), represents the current individual position, a, b, and c are randomly selected indices from 1 to N such that a ≠ b ≠ c ≠ i, and represents the randomly selected individual among a certain number of top solutions searched so far.

The projection matrix is used in Equation (4) to generate the trial solution . Here, , A and are the orthogonal matrix and binary vector, respectively. represents the binary diagonal matrix formed by placing the elements of the vector at the diagonal position. The binary diagonal matrix is generated randomly, such that

The pseudo code of the SS is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: SS | ||||

| 1 | Inputs: The population size N and maximum number of calculations T; | |||

| 2 | Outputs: The global optima and its fitness; | |||

| 3 | Initialize N D-dimensional individuals and calculate their fitness; | |||

| 4 | while t < T do | |||

| 5 | A Compute Orthogonal Matrix; | |||

| 6 | for i = 1 to N do | |||

| 7 | c = rand; | |||

| 8 | rk = rand; | |||

| 9 | for j = 1 to D do | |||

| 10 | if rand < rk then | |||

| 11 | = 1; | |||

| 12 | else | |||

| 13 | = 0; | |||

| 14 | end | |||

| 15 | end | |||

| 16 | if i < 0.5 × N then | |||

| 17 | ; | |||

| 18 | else | |||

| 19 | ; | |||

| 20 | end | |||

| 21 | ; | |||

| 22 | ; | |||

| 23 | ; | |||

| 24 | ; | |||

| 25 | end | |||

| 26 | end | |||

| 27 | Return the global optima | |||

2.2. Self-Adaptive Spherical Search Algorithm

To more effectively reach globally optimal solutions, Kumar, Das, and Zelinka propose the SASS algorithm [48], in which they use the successful history-based strategy to reset the parameters in the SS.

The success history-based parameter adaptation (SHPA) method [50] is proposed to adapt two control parameters, rk and c. As shown in Table 1, a historical memory that deserves H historical value of rk and c is set. In each generation, rk and c randomly select an element Lrk,j and Lc,j from Lrk and Lc, respectively, with j ∈ [1, H], which are calculated by Equations (8) and (9), respectively.

Table 1.

The historical memory of Lrk and Lc.

In the beginning, the values of Lrk,s and Lc,s (s = 1, 2, …, H) are all initialized to 0.5. The rk and c values used by successful individuals are recorded in Sr and Sc, and at the end of the generation, the contents of memory are updated as follows:

Here, an index h (h = 1, 2, …, H) determines the position in the memory to update, and h is increased progressively. If the value of h exceeds H, h is reset to 1. Furthermore, h is used to update the mean values by using the Lehmer mean () as follows.

where and are the length of vectors and , respectively.

3. Proposed Algorithm

Compared with other swarm-based meta-heuristic algorithms, the SASS is very efficient in exploring the new search regions of the solution space. However, it has weak exploration capability, and in some cases, its ability to escape from local optima is limited. Based on an in-depth study of the SASS, the following modifications are introduced to improve its search performance.

3.1. Population Initialization

The opposition-based learning (OBL) strategy [51] is an optimization technique to improve the quality of initial solutions by diversifying them, which has been used by many studies [52,53,54,55,56,57]. The OBL strategy is to search in two directions in the search space, including an original solution and its opposite solution. Finally, the OBL strategy takes the fittest solutions from all solutions. To enhance population diversity and improve the quality of solutions, the OBL strategy is used in the proposed algorithm.

The opposite number of x is, denoted by , calculated as:

where x is defined as a real number over the interval x ∈ [l, u]. Equation (17) is also applicable to multi-dimensional search space. Therefore, to generalize it, every search-agent position and its opposite position can be represented as

The values of all elements in can be determined by

The procedure for integrating the OBL with the SASS is summarized as follows:

- Step 1. Initialize the population P as xi, i = 1, 2, …, n.

- Step 2. Determine the opposite population as using Equation (20), i = 1, 2, …, n.

- Step 3. Select the n fittest individuals from {P ∪ OP}, which represents the new initial population of the SSDE.

3.2. Modifying the Search Direction

Assume that in the entire search process, we evaluate the objective function for T times. The proposed SSDE divides the search process into three phases based on the times of objective evaluation.

Phase 1 The first one-third of the calculation times of the objective evaluations constitutes the first phase. To prevent the algorithm from converging too fast and falling into local optima, the following search direction is proposed to improve the exploration performance of the algorithm:

where , , and are three different individuals randomly selected from the current population, and represents the randomly selected individual from the top p% solutions searched so far. The parameter R changes linearly, and is expressed by the following equation:

where t is the times of objective evaluation conducted so far. In this phase, the value of R is small (not greater than 1/3). Therefore, the difference item has less effect.

Phase 2 The middle one-third of the calculation times of the objective evaluations constitute the second phase. We hope that the algorithm can find the optima and balance the global exploration and the local exploitation in the search space. Therefore, the search direction is represented as follows:

In this phase, the value of R is between 1/3 and 2/3. Therefore, Equation (23) can help the algorithm better balance global exploration and local exploitation.

Phase 3 This phase corresponds to the last one-third of the calculation times of the objective evaluations. In this phase, we improve the exploitation ability and accelerate the convergence of the algorithm. Hence, we update the search direction as follows:

where is the best individual in the current population. The difference item has a great impact, which can help the algorithm converge fast and find the global optima.

3.3. Non-Linear Transition Parameter

In the SASS, the step-size control parameter c is generated from the Cauchy distribution at each iteration. However, a lot of problems require the parameter to change non-linearly changes in the exploratory and exploitative behaviors of an algorithm to avoid local optimal solutions [58,59,60,61]. An appropriate selection of this parameter is necessary to balance global exploration and local exploitation. To spend more time on the exploration phase than exploitation in the proposed algorithm, a non-linear self-adapting parameter c is used and given by

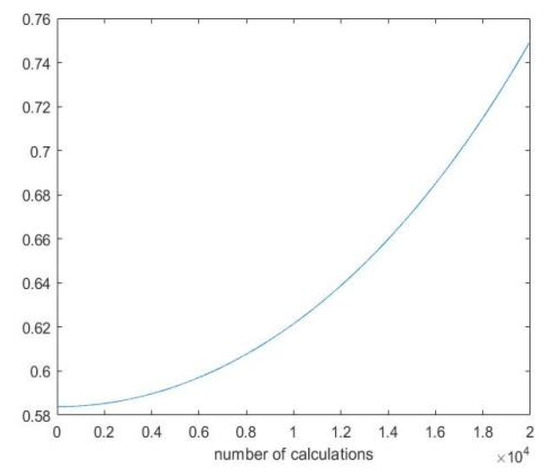

Figure 2 shows the change of c when the total times of objective function evaluation are set to 20,000. In fact, c controls the diameter of the spherical boundary. A slightly larger c at the later stage of iteration means that the spherical boundary becomes larger, and the individual can get closer to the global optima faster.

Figure 2.

The change of c when the total times of objective function evaluation are set to 20,000.

3.4. Mutation and Crossover Strategies

Inspired by DE, we add the mutation and crossover strategies to the SSDE.

- (1)

- Mutation strategy. For each individual in the current population, a mutation individual is produced through a mutation operation. Inspired by common mutation strategies, a new mutation strategy is introduced, represented by the following equation:where , , and are three different individuals randomly selected from the current population. The parameter R is a scale factor given by Equation (22), and is the optimal solution for the current population.

- (2)

- Crossover strategy. For the target individual and its associated mutation individual , a trial individual is generated using the binomial crossover:where PCR ∈ [0, 1] is a crossover probability, and j0 is a randomly generated index from {1, 2, …, N}.

Due to the impact of mutation, it is possible that some elements of trial individual may deviate from the feasible solution space. Therefore, the infeasible elements should be reset as follows.

In the SASS, if the offspring value is not as good as the parent solution, the algorithm does not replace its parent solution with the offspring solution, and the offspring solution is discarded. This will slow the convergence of the search process. To overcome this shortcoming, we add the above mutation and crossover strategies to the SSDE. In the proposed algorithm, if an offspring solution is worse than its parent solution, the algorithm uses mutation and crossover strategies to produce a new one. It will replace the parent solution if it is better than the parent. Otherwise, the parent solution will be reserved for the next iteration. In this way, the SSDE can find the optimal solution more efficiently and has a faster convergence speed.

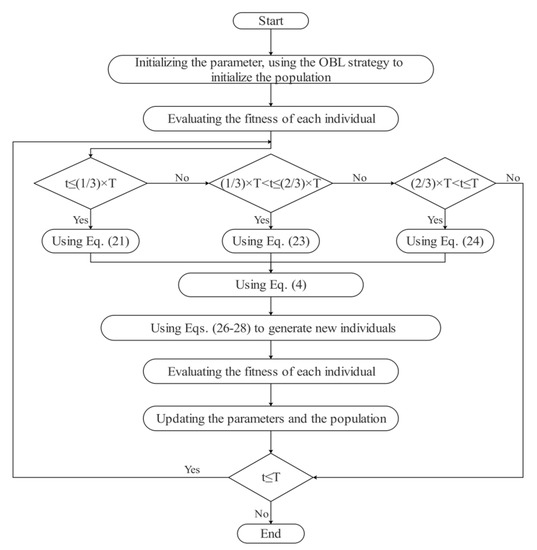

The flowchart of the proposed SSDE with all the above-mentioned strategies is shown in Figure 3, and the pseudo code is presented in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: SSDE | ||||||

| 1 | Inputs: The population size N and maximum number of calculations T; | |||||

| 2 | Outputs: The global optima and its fitness; | |||||

| 3 | Initialize N D-dimensional individuals with the OBL strategy and calculate their fitness; | |||||

| 4 | Set all values in Lrk to 0.5, h = 1; | |||||

| 5 | while t < T do | |||||

| 6 | Sr = ϕ; | |||||

| 7 | ; | |||||

| 8 | A Compute Orthogonal Matrix; | |||||

| 9 | for i = 1 to N do | |||||

| 10 | j = select from [1, H] randomly; | |||||

| 11 | rk = Binornd(D, Lrk,j); | |||||

| 12 | for k = 1 to D do | |||||

| 13 | if rand < rk then | |||||

| 14 | = 1; | |||||

| 15 | else | |||||

| 16 | = 0; | |||||

| 17 | end | |||||

| 18 | end | |||||

| 19 | if t < (1/3) × T then | |||||

| 20 | Using Equation (21); | |||||

| 21 | else if (1/3) × T < t < (2/3) × T then | |||||

| 22 | Using Equation (23); | |||||

| 23 | else | |||||

| 24 | Using Equation (24); | |||||

| 25 | end | |||||

| 26 | ; | |||||

| 27 | ; | |||||

| 28 | ; | |||||

| 29 | if then | |||||

| 30 | New solution is produced using Equations (26)–(28); | |||||

| 31 | ; | |||||

| 32 | ; | |||||

| 33 | ; | |||||

| 34 | else | |||||

| 35 | rk is recorded in Sr; | |||||

| 36 | end | |||||

| 37 | ; | |||||

| 38 | end | |||||

| 39 | if Sr ≠ ϕ | |||||

| 40 | update Lrk,h; | |||||

| 41 | h = h + 1; | |||||

| 42 | if h > H then, h is set to 1; end | |||||

| 43 | end | |||||

| 44 | = top p% solution searched so far; | |||||

| 45 | = best solution searched so far; | |||||

| 46 | end | |||||

| 47 | Return | |||||

Figure 3.

The flowchart of the SSDE.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

To test and verify the performance of the SSDE, a variety of experiments are conducted. Given the randomness of the optimization algorithm, to ensure that the superior results of the proposed algorithm do not happen by accident, we use the standard IEEE CEC 2017 [62] and two practical engineering problems to test the SSDE. In addition, to evaluate the strength of the SSDE, we compare the SSDE with the SASS and seven state-of-the-art algorithms: WOA, DE, PSO, SSA, SCA [63], GWO, and MSCA [59].

4.1. Experimental Analysis of Standard IEEE CEC2017 Benchmark Functions

The well-known 29 benchmark functions from a special session of IEEE CEC 2017 [62] are considered to analyze the performance of the SSDE and for comparison with the other state-of-the-art algorithms. Detailed information and characteristics of these problems are available in [64]. The CEC 2017 test functions are categorized into four groups: unimodal (F1–F3), multimodal (F4–F10), hybrid (F11–F20), and composite (F21–F30).

For any benchmark test function, each algorithm runs 30 times independently and the population size is set to 25. The algorithm will stop when the times of function evaluation reach 20,000, i.e., T = 20,000. Other parameters are the same as the original algorithm to ensure the fairness of comparison. The obtained results on these test functions corresponding to 10-dimensional search space are recorded in Table 2. The Wilcoxon sign rank test is also utilized to judge whether the improvements are significant in Table 3. The experimental results of 30 and 50 dimensions on these test functions are shown in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

Experimental results of IEEE CEC 2017 test problems with 10 dimensions.

Table 3.

The calculated p-values for the SSDE algorithm versus other competitors on CEC2017.

Table 4.

Experimental results of IEEE CEC 2017 test problems with 30 dimensions.

Table 5.

Experimental results of IEEE CEC 2017 test problems with 50 dimensions.

In 0, we can see that the SSDE achieves the best accuracy on all test functions except F1 and F23. This shows that the SSDE has strong competitiveness in unimodal functions, multimodal functions, hybrid functions, and composite functions. Specifically, the SSDE uses the OBL strategy, staged search mechanism, and non-linear self-adapting parameters to explore the wider unknown area of the search space. These strategies help the SSDE avoid premature convergence and accelerate convergence by taking full advantage of the global optimal individual’s information at the later search stage. From Table 3, it can be seen that most of the p-values are less than 0.05, indicating that the performance of the SSDE on all the test functions is significantly improved compared with SASS and other competitors.

We can see from Table 4 that the SSDE remains very competitive with other algorithms at 30 dimensions. Results show that the SSDE is significantly better than PSO, SASS, GWO, SCA, DE, MSCA, SSA, and WOA on a total of 29, 22, 29, 29, 29, 29, 29, and 29 test functions, respectively. The competitive results on all functions reveal that the SSDE can find the optimal solution more effectively. In addition, from Table 5, the SSDE performs better than all of the compared algorithms on F4, F6–7, F9, F11–F15, F17–F20, F23–24, F26, F29, and F30. On F1 and F3 the SSDE is slightly lower than that of some compared algorithms and ranks third and second, respectively. As for the multimodal functions, the SSDE shows good performance, while it obtains no-best results only on F5, F8, and F10. On all 20 hybrid and composite functions, the SSDE obtains the optimal solution on all 14 functions. Compared with the SASS, the SSDE ranks first on 11 functions while SASS ranks first on five functions. It indicates that the proposed algorithm can deal with the combination functions more effectively.

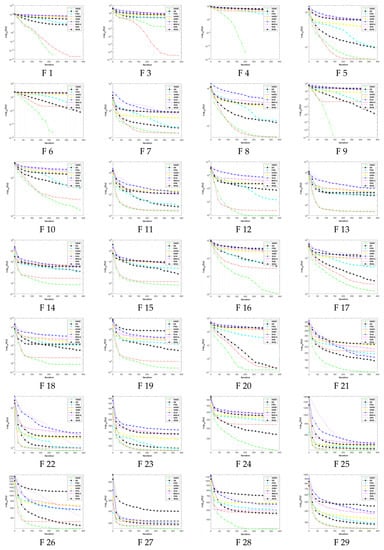

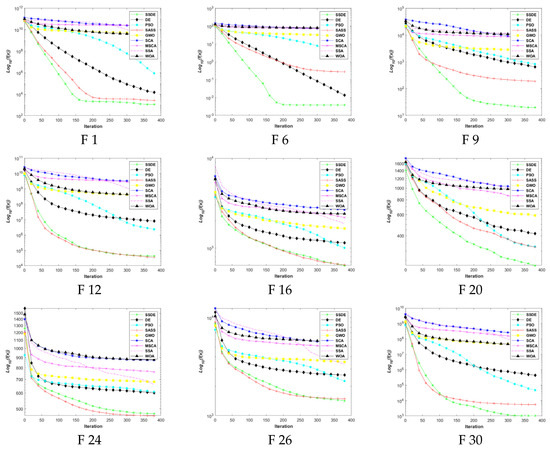

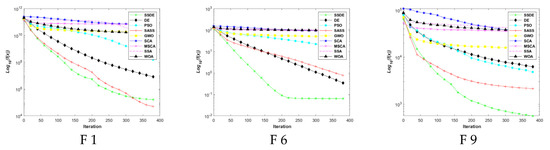

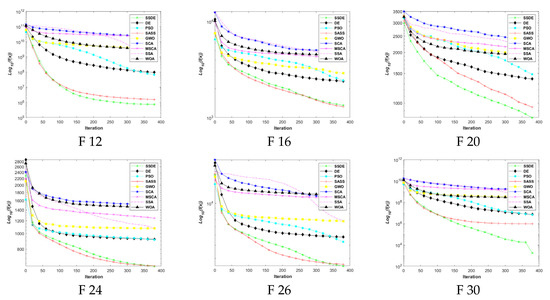

Thus, from the results presented in these tables, we conclude that all employed strategies in Section 3 have shown their impact on improving the search mechanism of the SASS for obtaining better solution accuracy. Furthermore, to analyze the convergence rates of WOA, DE, PSO, SSA, SCA, GWO, and MSCA, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 plot the evolution curve of the best value.

Figure 4.

Evolutionary curves of SSDE, DE, PSO, SASS, GWO, SCA, MSCA, SSA, and WOA on the CEC 2017 test functions in 10 dimensions.

Figure 5.

Evolutionary curves of SSDE, DE, PSO, SASS, GWO, SCA, MSCA, SSA, and WOA on the CEC 2017 test functions in 30 dimensions.

Figure 6.

Evolutionary curves of SSDE, DE, PSO, SASS, GWO, SCA, MSCA, SSA, and WOA on the CEC 2017 test functions in 50 dimensions.

The convergence diagrams of 10 dimensions on the CEC2017 test functions for the SSDE and other comparison algorithms are shown in Figure 4. These diagrams show that the SSDE has much higher accuracy than SASS, indicating that the optimization capability of SASS has been improved considerably with the introduction of the OBL, phased search, mutation and crossover strategies, and the non-linear parameter. Figure 4 shows that the SSDE with the fastest convergence speed outperforms all other optimizers in dealing with F3, F5–F11, F13–F21, F24, and F26–F30.

In Figure 5 and Figure 6, we select some representative functions and expose a convergence diagram of the SSDE and the algorithms for comparison. These representative functions come from all four types of CEC2017 test functions. It can be found that the SSDE converges on F3 at 50 dimensions second only to the SASS. However, the initial solution of the SSDE is better at the beginning. In other functions, SSDE has a much faster convergence speed than SASS and the other competitors. The obtained results show that the SSDE is competitive in dealing with multi-dimensional problems.

4.2. Practical Engineering Design Problem

In this section, we study the performance of the SSDE in solving practical engineering problems. Two constrained practical engineering problems are considered, namely a welded beam design problem and a pressure vessel design problem. The optimization results with the SSDE are to be compared with the results of several well-regarded algorithms for an unbiased conclusion. Since the two engineering problems are constrained problems, a classic penalty method is used to handle the constraints [64].

4.2.1. Welded Beam Design

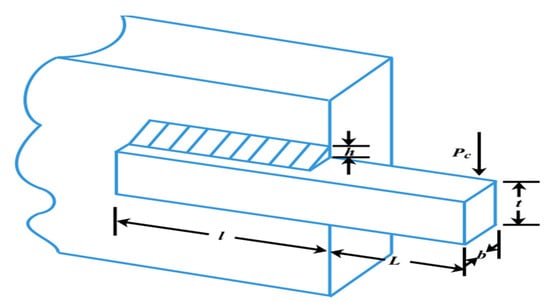

The goal of this problem is to minimize the manufacturing cost of the welded beam under four constraints including shear stress (), bending stress (), buckling load (), and deflection () [65]. As shown in Figure 7, there are four variables involved in this problem: welding seam thickness (), welding joint length (), beam width (), and beam thickness (). The mathematical model can be described as follows:

where

P = 6000lb, L = 14in, E = 30 psi, G = 12 psi, = 30,600 psi, = 30,000, = 0.23in.

| Consider | |

| Minimize | |

| Subject to | |

| Variable ranges: |

Figure 7.

Design of a welded beam problem.

On this subject, Goello and Montes [66], Deb [65,67] use GA to solve it. Lee and Geem [68] use HS to optimize this problem. Radgsdell and Phillips [69] employ mathematical approaches including Richardson’s random method, Simplex method, Davidon–Fletcher–Powell, Griffith, and Stewart’s successive linear approximation. The results are provided in Table 6, which show that the SSDE algorithm finds a solution with the minimum cost compared with others. We conclude that the SSDE algorithm solves the welded beam design problem brilliantly.

Table 6.

Comparison of results of the welded beam design problem.

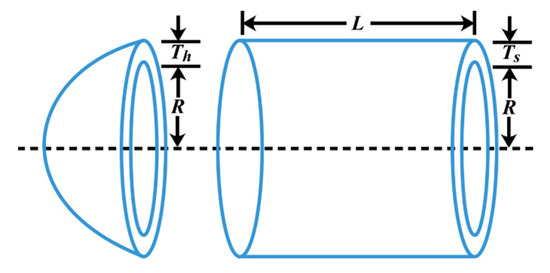

4.2.2. Pressure Vessel Design

The goal of this problem is to minimize the total cost consisting of material, forming, and welding of a cylindrical vessel. As shown in Figure 8, there are four decision variables involved in this problem: the thickness of the shell (), the thickness of the head (), inner radius (), and length of the cylindrical section of the vessel (). The mathematical model is described as follows:

| Consider | |

| Minimize | |

| Subject to | |

| Variable ranges: |

Figure 8.

Design of a pressure vessel problem.

This optimization problem has been well studied. He and Wang [71] use PSO to solve this problem while Deb [72] uses GA. In addition, ES [73], DE [31], and two mathematical methods in [74,75], are all adopted to crack this problem. The results are provided in Table 7. The SSDE outperforms all the other algorithms. The results prove that the SSDE is a highly competitive candidate for solving the welded beam design problem.

Table 7.

Comparison of results of the pressure vessel design problem.

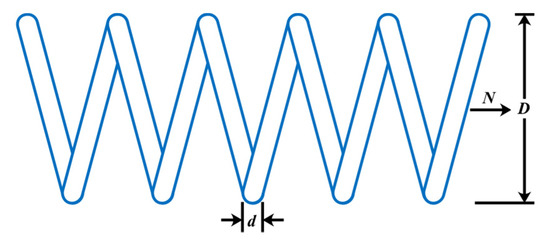

4.2.3. Tension/Compression Spring Design

This problem is described in [33]. The goal of this problem is to minimize the weight of the spring. As shown in Figure 9, there are three decision variables in this problem, which are wire diameter (d), mean coil diameter (D), and the number of active coils (N). This problem has four inequality constraints, which are mathematically expressed as follows:

| Consider | |

| Minimize | |

| Subject to | |

| 0.05 ≤ x1 ≤ 2.00, 0.25 ≤ x2 ≤ 1.30, 2.00 ≤ x3 ≤ 15.0 | |

Figure 9.

Design of a tension/compression spring problem.

The comparison results between SSDE and other state-of-art algorithms are given in Table 8. From this table, it is clear that SSDE achieves the best results with x* = (0.051785958, 0.3590533, 11.15334) and object function f(x) = 0.012665403. Compared with the results obtained by other algorithms, SSDE can deal with this problem well.

Table 8.

Comparison of results of the tension/compression spring problem.

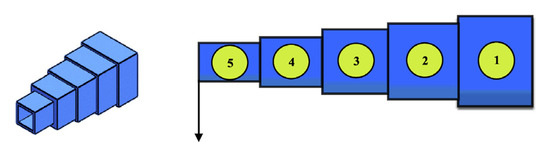

4.2.4. Cantilever Beam Design

The cantilever beam problem is shown in Figure 10. This problem includes five hollow blocks, so the number of variables is five [32]. The objective is to minimize the weight of the beam. The problem formulation is as follows:

| Consider | |

| Minimize | |

| Subject to | |

| 0 ≤ xi ≤ 100, i = 1, 2, …, 5 | |

Many algorithms have been used to solve the cantilever beam design problem, and the results of the comparison are shown in Table 9. From Table 9, we can see that SSDE achieves the best results. Thus, SSDE is a better optimizer for solving this problem.

Table 9.

Comparison of results of the cantilever beam problem.

Table 9.

Comparison of results of the cantilever beam problem.

| Algorithm | Optimum Variables | Optimal Cost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | x5 | ||

| SSDE | 6.016016 | 5.30917382 | 4.4943296 | 3.50147497 | 2.1526653 | 1.33995636 |

| ISA (Jahangiri) [79] | 6.0246 | 5.2958 | 4.4790 | 3.5146 | 2.1600 | 1.33996 |

| WOA (Mirjalili) [32] | 5.5638 | 6.0809 | 4.6858 | 3.2263 | 2.2467 | 1.36055 |

| ABC (Karaboga) [34] | 5.9638 | 5.3312 | 4.5122 | 3.4744 | 2.1952 | 1.34004 |

| GWO (Mirjalili) [33] | 6.0189 | 5.3173 | 4.4922 | 3.5014 | 2.1440 | 1.33997 |

| AEO (Zhao) [78] | 6.02885 | 5.31652 | 4.46265 | 3.50846 | 2.15776 | 1.33997 |

| GBO (Ahmadianfar) [80] | 6.0124 | 5.3129 | 4.4941 | 3.5036 | 2.1506 | 1.33996 |

Figure 10.

Design of a cantilever beam problem [80].

4.3. Computation Cost of the SSDE

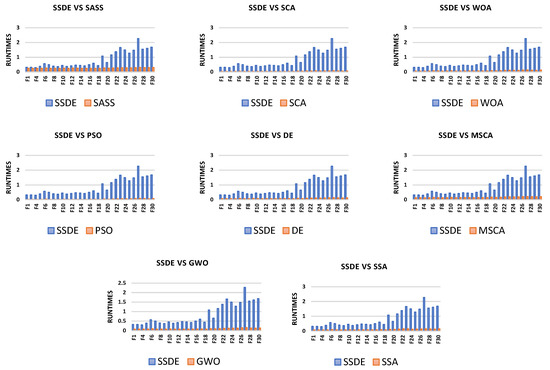

The running time of the SSDE and the algorithms for comparison on the 29 benchmark problems at 10 dimensions are shown in Figure 11. It is clear that the computation cost of the SSDE is higher than those of the other eight algorithms. Specifically, the average running time that the SSDE spends at 10 dimensions is 0.84, and the average running time of SASS, PSO, GWO, SCA, DE, SSA, WOA, and MSCA are 0.268, 0.04, 0.102, 0.052, 0.092, 0.111, 0.085, and 0.166, respectively. The reason for the longer running time of the SSDE is that its search process is divided into three stages, and the mutation and crossover strategies are applied at the end of the algorithm. However, although the SSDE takes more time than other algorithms, it can find optimal solutions.

Figure 11.

Running time comparison in 10 dimensions.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a new swarm-based heuristic algorithm named SSDE. It divides the search process in search space into three phases. Each phase uses a different search rule. A non-linear self-adapting parameter is proposed. These strategies help the SSDE algorithm find the optimal solution more effectively. To verify its performance, we test 10 dimensions, 30 dimensions, and 50 dimensions of objective functions on the CEC 2017 test functions. Numerical results show that the SSDE is a competitive SASS variant in most functions. Compared with the other seven most popular algorithms, the SSDE exhibits stronger performance. In addition, the SSDE is also used to solve two popular practical engineering design problems, including the welded beam design problem and the pressure vessel design problem, which further demonstrate the power of the proposed algorithm in solving these kinds of engineering problems.

In future work, we will further enhance the performance of the SSDE algorithm. Orthogonal learning, levy flight, ranking-based schemes, multi-population structures, and their various combinations may be applied. We will use the SSDE in various applications, such as constrained optimization, parameter optimization, and feature selection. In addition, the proposed algorithm can also be reconstructed as a multi-objective technique based on the Pareto condition to further improve its performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z. and J.Z.; methodology, B.Z. and J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, B.Z., J.Z. and Z.L.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Z., J.Z., X.G., L.Q. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, B.Z., J.Z., X.G., L.Q. and Z.L.; visualization, B.Z.; supervision, B.Z., J.Z. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1731128), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province, PR China (Grant No.2019-MS−174), and the Foundation of Liaoning Province Education Administration, PR China (Grant Nos. 2019LNJC12, 2020LNQN05, LJKZ0279).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhou, F.; Yang, S.; Fujita, H.; Chen, D.; Wen, C. Deep learning fault diagnosis method based on global optimization GAN for unbalanced data. Knowl. Based Syst. 2019, 187, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Qi, L.; Wang, Y. Hybrid Scatter Search Algorithm for Optimal and Energy-Efficient Steelmaking-Continuous Casting. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1814–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhou, M.; Yu, Y. A multi-layered gravitational search algorithm for function optimization and real-world problems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2020, 8, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, L. Lexicographic Multiobjective Scatter Search for the Optimization of Sequence-Dependent Selective Disassembly Subject to Multiresource Constraints. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 3307–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, F.A.; Houssein, E.H.; Hussain, K.; Mabrouk, M.S.; Al-Atabany, W. Honey Badger Algorithm: New metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Math. Comput. Simul. 2022, 192, 84–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Chan, W.S.; Tang, K.S.; Zheng, S.Y. Adaptive strategy in differential evolution via explicit exploitation and exploration controls. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 107, 107494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelblau, D.M. Applied Nonlinear Programming; McGraw-Hill: NewYork, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.; Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S. Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms; Academic Press: Pittsburgh, PE, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niknam, T. A new fuzzy adaptive hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm for non-linear, non-smooth and non-convex economic dispatch problem. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Guo, X.; Qi, L. Modified cuckoo search algorithm to solve economic power dispatch optimization problems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2018, 5, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Guo, X.; Qi, L. An Improved Binary Cuckoo Search Algorithm for Solving Unit Commitment Problems: Methodological Description. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 43535–43545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaccia, F.; Mussetta, M.; Zich, R.E. Genetical Swarm Optimization: Self-Adaptive Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Electromagnetics. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2007, 55, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Lin, C.; Zhou, M. A Knowledge-Based Cuckoo Search Algorithm to Schedule a Flexible Job Shop With Sequencing Flexibility. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Abusorrah, A. Dual-Objective Mixed Integer Linear Program and Memetic Algorithm for an Industrial Group Scheduling Problem. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2021, 8, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; You, D.; Guo, X. Heuristic Scheduling of Batch Production Processes Based on Petri Nets and Iterated Greedy Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, M.; Liu, S. Iterated Greedy Algorithms for Flow-Shop Scheduling Problems: A Tutorial. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 1941–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Qi, L. A Hybrid MIP–CP Approach to Multistage Scheduling Problem in Continuous Casting and Hot-Rolling Processes. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2019, 16, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, L.; Liu, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Stochastic Hybrid Discrete Grey Wolf Optimizer for Multi-Objective Disassembly Sequencing and Line Balancing Planning in Disassembling Multiple Products. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 1744–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, M.; Liu, S.; Qi, L. Multiresource-Constrained Selective Disassembly With Maximal Profit and Minimal Energy Consumption. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 804–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, M.; Abusorrah, A.; Alsokhiry, F.; Sedraoui, K. Disassembly Sequence Planning: A Survey. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2020, 8, 1308–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Tian, G. Dual-Objective Program and Scatter Search for the Optimization of Disassembly Sequences Subject to Multiresource Constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Tian, G. Disassembly Sequence Optimization for Large-Scale Products With Multiresource Constraints Using Scatter Search and Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 46, 2435–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parejo, J.A.; Ruiz-Cortés, A.; Lozano, S.; Fernandez, P. Metaheuristic optimization frameworks: A survey and benchmarking. Soft Comput. 2012, 16, 527–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Qu, B.-Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.-Z.; Suganthan, P.N.; Zhang, Q. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: A survey of the state of the art. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2011, 1, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Luan, W. A dynamic road incident information delivery strategy to reduce urban traffic congestion. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2018, 5, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Luan, W.; Lu, X.S.; Guo, X. Shared P-Type Logic Petri Net Composition and Property Analysis: A Vector Computational Method. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34644–34653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Deep, K.; Engelbrecht, A.P. A memory guided sine cosine algorithm for global optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 93, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence. In Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory, MHS′95. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution—A simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey Wolf Optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: Artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2007, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Gandomi, A.H.; Mirjalili, S.Z.; Saremi, S.; Faris, H.; Mirjalili, S.M. Salp Swarm Algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2017, 114, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Połap, D.; Woz´niak, M. Polar Bear Optimization Algorithm: Meta-Heuristic with Fast Population Movement and Dynamic Birth and Death Mechanism. Symmetry 2017, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Moth-flame optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired heuristic paradigm. Knowl. Based Syst. 2015, 89, 228–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. Dragonfly algorithm: A new meta-heuristic optimization technique for solving single-objective, discrete, and multi-objective problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk-Allah, R.; Zaki, E.M.; El-Sawy, A.A. Hybridizing ant colony optimization with firefly algorithm for unconstrained optimization problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 224, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Qin, A.K.; Suganthan, P.N.; Baskar, S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Das, S.; Das, A.K.; Gao, L. Reusing the Past Difference Vectors in Differential Evolution—A Simple But Significant Improvement. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 50, 4821–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Khamparia, A. A hybrid whale optimization-differential evolution and genetic algorithm based approach to solve unit commitment scheduling problem: WODEGA. Sustain. Comput. Informatics Syst. 2020, 28, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jangir, P.; Tejani, G.G.; Premkumar, M. A Decomposition based Multi-Objective Heat Transfer Search algorithm for structure optimization. Knowl. -Based Syst. 2022, 253, 109591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, B.S.; Kumar, S.; Pholdee, N.; Bureerat, S.; Sait, S.M.; Yildiz, A.R. A new chaotic Lévy flight distribution optimization algorithm for solving constrained engineering problems. Expert Syst. 2022, 39, e12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, B.S.; Mehta, P.; Sait, S.M.; Panagant, N.; Kumar, S.; Yildiz, A.R. A new hybrid artificial hummingbird-simulated annealing algorithm to solve constrained mechanical engineering problems. Mater. Test. 2022, 64, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Misra, R.K.; Singh, D.; Mishra, S.; Das, S. The spherical search algorithm for bound-constrained global optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 85, 105734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Das, S.; Zelinka, I. A self-adaptive spherical search algorithm for real-world constrained optimization problems. In Proceedings of the 2020 Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Cancún, Mexico, 8–12 July 2020; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, C.; Todo, Y.; Gao, S. A Hybrid Spherical Search and Moth-flame optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 12th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics (IHMSC), Hangzhou, China, 22–23 August 2020; pp. 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A. Success-history based parameter adaptation for Differential Evolution. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizhoosh, H.R. Opposition-Based learning: A new scheme for machine intelligence. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation and International Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce, Vienna, Austria, 28–30 November 2005; pp. 1695–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Song, E.; Li, H. A Self-Adaptive Differential Evolution Algorithm Using Oppositional Solutions and Elitist Sharing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 20035–20050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Ding, R.; Liu, W. An enhanced differential evolution algorithm with a new oppositional-mutual learning strategy. Neurocomputing 2021, 435, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhargupta, S.; Ghosh, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Sarkar, R. Selective Opposition based Grey Wolf Optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 151, 113389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X. A multi-strategy enhanced sine cosine algorithm for global optimization and constrained practical engineering problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 369, 124872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubishat, M.; Idris, N.; Shuib, L.; Abushariah, M.A.; Mirjalili, S. Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm based on opposition based learning and novel local search algorithm for feature selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 145, 113122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Fang, X. ESSAWOA: Enhanced Whale Optimization Algorithm integrated with Salp Swarm Algorithm for global optimization. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Deep, K.; Mirjalili, S.; Kim, J.H. A modified Sine Cosine Algorithm with novel transition parameter and mutation operator for global optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 154, 113395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Gao, S.; Gupta, S.; Cheng, J.; Yang, G. An aggregative learning gravitational search algorithm with self-adaptive gravitational constants. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 152, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, L. Bare-Bones Based Sine Cosine Algorithm for global optimization. J. Comput. Sci. 2020, 47, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E.; Öztürk, N.; Arya, Y. Advancement of the search process of salp swarm algorithm for global optimization problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 182, 115292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2017 Competition and Special Session on Constrained Single Objective Real-Parameter Optimization. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guohua-Wu-5/publication/317228117_Problem_Definitions_and_Evaluation_Criteria_for_the_CEC_2017_Competition_and_Special_Session_on_Constrained_Single_Objective_Real-Parameter_Optimization/links/5982cdbaa6fdcc8b56f59104/Problem-Definitions-and-Evaluation-Criteria-for-the-CEC-2017-Competition-and-Special-Session-on-Constrained-Single-Objective-Real-Parameter-Optimization.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2020.).

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: A Sine Cosine Algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl. Based Syst. 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A.C. Theoretical and numerical constraint-handling techniques used with evolutionary algorithms: A survey of the state of the art. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2002, 191, 1245–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Optimal design of a welded beam via genetic algorithms. AIAA J. 1991, 29, 2013–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, C.A.C.; Montes, E.M. Constraint-handling in genetic algorithms through the use of dominance-based tournament selection. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2002, 16, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. An efficient constraint handling method for genetic algorithms. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2000, 186, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Geem, Z.W. A new meta-heuristic algorithm for continuous engineering optimization: Harmony search theory and practice. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 3902–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdell, K.M.; Phillips, D.T. Optimal Design of a Class of Welded Structures Using Geometric Programming. J. Eng. Ind. 1976, 98, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Hatamlou, A. Multi-Verse Optimizer: A nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural. Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, L. An effective co-evolutionary particle swarm optimization for constrained engineering design problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2007, 20, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. GeneAS: A Robust Optimal Design Technique for Mechanical Component Design. In Evolutionary Algorithms in Engineering Applications; Dasgupta, D., Michalewicz, Z., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 497–514. [Google Scholar]

- Mezura-Montes, E.; Coello, C.A.C. An empirical study about the usefulness of evolution strategies to solve constrained optimization problems. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 2008, 37, 443–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgren, E. Nonlinear Integer and Discrete Programming in Mechanical Design Optimization. J. Mech. Des. 1990, 112, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, B.; Kramer, S.N. An augmented Lagrange multiplier based method for mixed integer discrete continuous optimization and its applications to mechanical design. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, N.H.; Ali, M.Z.; Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P.N. An improved differential evolution algorithm using efficient adapted surrogate model for numerical optimization. Inf. Sci. 2018, 451–452, 326–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z. Artificial ecosystem-based optimization: A novel nature-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 9383–9425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, M.; Hadianfard, M.A.; Najafgholipour, M.A.; Jahangiri, M.; Gerami, M.R. Interactive autodidactic school: A new metaheuristic optimization algorithm for solving mathematical and structural design optimization problems. Comput. Struct. 2020, 235, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Chu, X. Gradient-based optimizer: A new metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2020, 540, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).