Abstract

The following problem was studied: let be a sequence of i.i.d. d-dimensional random vectors. Let F be their probability distribution and for every consider the sample Then was called a “leader” in the sample if and was an “anti-leader” if . The comparison of two vectors was the usual one: if then means while means Let be the probability that has a leader, be the probability that has an anti-leader and be the probability that has both a leader and an anti-leader. Sometimes these probabilities can be computed or estimated, for instance in the case when F is discrete or absolutely continuous. The limits were considered. If it was said that F has the leader property, if they said that F has the anti-leader property and if then F has the order property. In this paper we study an in-between case: here the vector has the form where and X is a random variable. The aim is to find conditions for in order that or . The most examples will focus on a more particular case with X uniformly distributed on the interval .

MSC:

52A22; 53C65; 60D05; 60E05; 60E15

1. Introduction

In a previous paper [1], the following problem was studied: what is the probability that a “leader” exists in a set of n i.i.d. d-dimensional random vectors, . Various formulae were established. In most cases, as If , it is said that “ has the leader property”. This property is, rather, an exception, not a rule, among the d-dimensional probability distributions.

The problem was prompted by the relevance of various rankings, which are fashionable today and which are obtained by the unidimensionalization of a data set using different algorithms. For instance: the ranking of the countries by HDI—human development index or by corruption index, of musical hits, of universities, of researchers, or of scientific journals by various ISI factors.

The topic the Pareto maxima or minima in random sets is approached in several articles, such as [2,3].

A series of papers study the expected number of maximal vectors in a set of n elements from a d-dimensional space: in [4], this is derived a recurrence relation for computing the average number of maximal vectors under the assumption that all relative orderings are equally probable, while in [5], the expected number of maximal vectors is determined explicitly for any n and d assuming that the vectors are distributed identically and that the d components of each vector are distributed independently and continuously. See other similar results in [6].

The asymptotic behaviour of this quantity as n tends to infinity has also been investigated. For instance, in [7], the authors proved that the number of maximal points is approximately normally distributed, under given conditions. In addition, see [4] or [8].

On the other hand, in [9] is presented an exact expression for the variance in the number of maxima in a three-dimensional cube.

In [10], the authors derive a general asymptotic formula for the variance in the number of maxima in a set of independent and identically distributed random vectors in , where the components of each vector are independently and continuously distributed.

However, the authors in [1] were not interested in finding Pareto maxima or minima but in the existence of real maximum or minimum in a finite random set. That is, in the existence of a first or last element.

In [1], the focus was on discrete or absolutely continuous vectors .

Here, we consider an in-between case: suppose that there exists an imponderable (meaning that it cannot be measured) uni-dimensional random variable which determines the ranking.

Next, suppose that we can measure various effects of X assumed to be functions In this case, the vector becomes . We may hope that now it is easier to compute the probabilities and to decide their limits

It is well-known (see [11]) that we can always replace the random variable X by where U is uniformly distributed on and is the quantile of the distribution function of X. Thus, there is no restriction if we consider that X itself is uniformly distributed.

The challenge is to determine the properties of for which has a leader.

2. Stating of the Problem

Let be a random variable uniformly distributed on let be a measurable function and let We shall denote by the same letter F both the probability distribution of (which is a measure on the borelian subsets of ) and its distribution function. Thus

for any

There should be no danger of confusion since in an integral of the form the first F is a function an the last F is a measure. Moreover, the integral is a Lebesgue integral.

Let us denote

for any and

If the function is one to one, then F is a continuous distribution, meaning that for any, at most, countable Borel set C from For continuous distributions, the general formulae established in [1] were

Remark 1.

It is important to notice that means the probability that two i.i.d. F-distributed vectors and are comparable.

Remark 2.

Clearly, is the probability that a set of three random vectors are ordered.

Remark 3.

Recall that a function is called strongly increasing (see [1]) if if and only if Of course, in the one-dimensional case, “strongly increasing" and “non-decreasing" is the same thing. Obviously, remain the same if we replace by

In our special case, when X is uniformly distributed on the integration formula becomes

E E for any integrable function ; hence,

Let with interval and arbitrary. We denote

and let be the Lebesgue measure.

Proposition 1.

If X is uniformly distributed on

Proof.

With one can easily find the probability:

□

Next, if and , define the functions and using

Therefore, we can rewrite relations (7), (8), (9) as

Let us denote

Thus, the problem is: compute If not, find conditions for such that the limits are positive.

3. General Results

Here we show some results that hold without any restrictions on the dimension d of the space. The function is supposed to be bounded measurable and injective.

Definition 1.

A partially ordered set C has the property L if it has a last element, that is, if there exists such that for every We say that C has the property F if it has a first element, that is, if there exists an element such that for every Finally, the set C has the property FL if it has both a first element and a last element.

One of the results from [1], namely, Proposition 2, p. 5, is that: if a distribution F has the leader/anti-leader/order property, its support must have the properties L/F/FL.

The support of the distribution F, denoted by is defined to be the intersection of all closed sets M with

In our case, if , it is more or less obvious that the support of F is the closure of the image of :

Thus,

Proposition 2.

Let is a random variable uniformly distributed on , let be a bounded measurable function. Let F be the distribution of Then, the following assertions hold:

- If then there exists such that for all If then there exists such that for all In the particular case when is increasing then Otherwise written, the function must have a global maximum. If is increasing, this is at

- If then there exists such that for all If then there exists such that for all In the particular case when is increasing then Otherwise written, the function must have a global minimum. If is increasing, this is at

- If then there exists such that for all If then there exist such that for all Otherwise written, the function must have both a global maximum and a global minimum. In the particular case when is increasing then

Proof.

Obvious. The set has a last element if there exists such that for all However, that is equivalent to the fact that for all or, which is the same thing, that for all Now, if then for some □

The next result establishes some relations between the functions defined in (15).

Proposition 3.

For an arbitrary function , consider the functions defined by relation (15). Then, the following hold:

- 1.

- where is a constant.

- 2.

- for any The equality is possible if and only if a.s.

Proof.

Let the constant and arbitrarily. Then:

- Write relations (15) as , with Remark that and that is all. The equality occurs if and only if a.s. or if a.s. for all

Let such that is an increasing function. The following are obvious:

Remark 4.

Remark 5.

Ifandthen

Remark 6.

If then has the same as for instance and so on.

Remark 7.

Obviously, if f is non-decreasing then

Actually, this is a good opportunity to check formulae (4)–(6):

Indeed,

In the same way,

In addition, according to Proposition 3 (2),

Thus, and

If we are interested only in and not in , then the following result may help.

Proposition 4.

Suppose that has the property that is an increasing function. Then for every the following are true

Proof.

Obvious. If is increasing then and As the probabilities defined in and verify with and and as , it is obvious that

The same holds for b and □

Finally, we will need the following result ([1], Lemma 5, p. 18).

Proposition 5.

- 1.

- Let be continuous at . Then for any

- 2.

- Let be increasing and differentiable such that and let g be as above. Then for any

- 3.

- Let be continuous.

Then for any

Now we can prove the general result.

Theorem 1.

Let be measurable bounded function with the properties: is increasing; is differentiable, increasing in a neighborhood of and such that is continuous is differentiable, decreasing in a neighborhood of and such that its derivative is continuous. The following assertions hold.

- (i)

- If If then

- (ii)

- If If then

- (iii)

- Always

- (iv)

- If there exists such that for then

Proof.

or,

If then we may choose an small enough such that thus,

If then let be small enough so that on the interval the mapping is an increasing differentiable, and on the interval , the function is a decreasing differentiable.

Then Let ; hence,

It follows that according to Proposition 5 (2).

Next Let ; hence, The same trick.

Finally, If or there is nothing to prove.

If and , then according to Proposition 3 (2). For any we shall denote

If then let be fixed. Let be small enough such that the mapping is increasing and differentiable on the interval and for every , the function is decreasing, and differentiable on the interval . We shall denote

Let Thus, and . As then . It follows that

As it results that

But thus,

and it remains that According to (ii), these inequalities can be written as:

As is arbitrarily small, we infer that

To conclude,

(iv). An immediate consequence of the proof of (iii). □

Remark 8.

In the above theorem, it is important that at least one of the components of is increasing. Otherwise, all the assertions fail to be true. Consider for example the case when is measurable non decreasing and is any measurable function. If all the quantities are always equal to 1. The reason is that the image of is an increasing curve: if then Many similar examples could be constructed.

4. The Bidimensional Case

We study the case with as a uniformly distributed random variable and a measurable function. Therefore, the function from the previous section is and

We shall consider the functions defined in relations More exactly, let

for each .

Let us denote

for each

The next result is a consequence of Proposition 1.

Lemma 1.

Let λ be the Lebesgue measure and the functions defined according to (31), (32) and (33).

Then

where the sets and are defined by notation and

Proof.

As X is uniformly distributed, it follows that for any borel set Therefore, Next

proving the assertion (34).

The proof of (35) is the same.

Regarding (36),

. □

Definition 2.

Let be a measurable function and the functions defined according to (31), (32), (33). We shall say that

f is L-acceptable

if

f is F-acceptable

if

f is F, L-acceptable

if

In words, if with then f is L-acceptable if the distribution function of , has the leader property. In addition, f is F-acceptable if F has the anti-leader property and f is F, L-acceptable if F has the order property.

Obviously, if f is L-acceptable then because otherwise if then . In the same way, if f is F-acceptable then and if f is F,L-acceptable then

According to Proposition 2, if f is L-acceptable then must have a last element.

Remark 9. Let us mention the following interesting fact:

- A function f is F,L-acceptable if and only if f is both F-acceptable and L -acceptable.

- Indeed, if f is F-acceptable then and if f is L-acceptable then

- According to Theorem 1 (3), . Therefore, if f is both F-acceptable and L-acceptable it results that and by definition this means that f is F,L-acceptable.

It is known (see [1]) that implies that has a last element. Thus, a natural question is:

If has a last element is it true or not that f is L-acceptable?

For general distribution functions F we know from [1] that the answer is no. However, this is a particular case and one could expect that in particular cases the answer is yes.

The answer is still no.

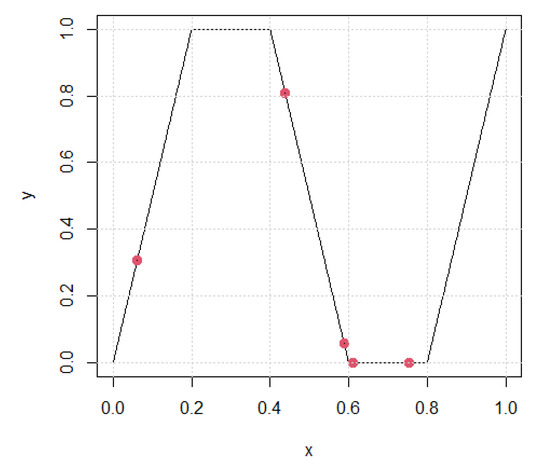

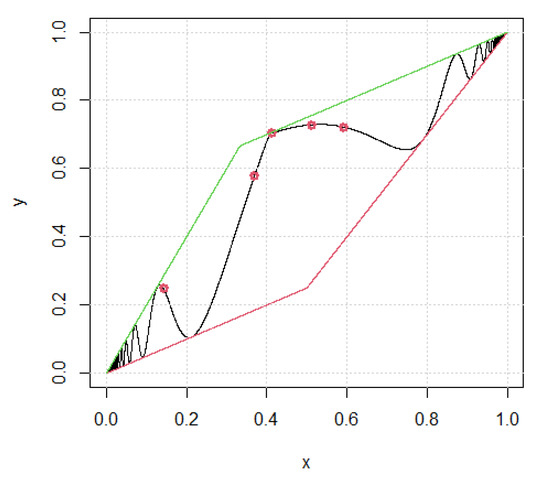

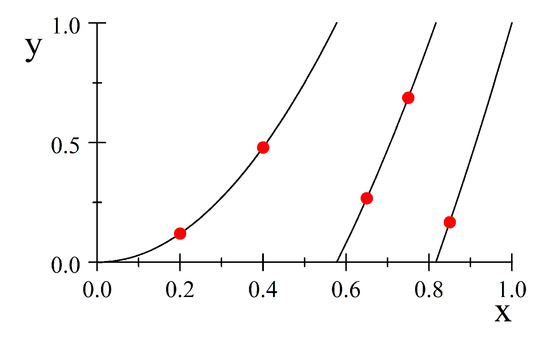

Counterexample 1.

Let defined by

In this case, has as last element and as first element (see Figure 1), but f is neither F-acceptable nor L-acceptable.

Figure 1.

has as last element and as first element, but f is not F,L-acceptable. The marked set of five points has neither first nor last element.

Indeed, writing the functions (29), (30) and (31) as

It follows that

Thus meaning that f is not L-acceptable neither F-acceptable. The fact that should be obvious due to the symmetry of the graph of f with respect to the point

The probability that and are comparable is equal to and the probability that are ordered is equal to

After all, this is not surprising because

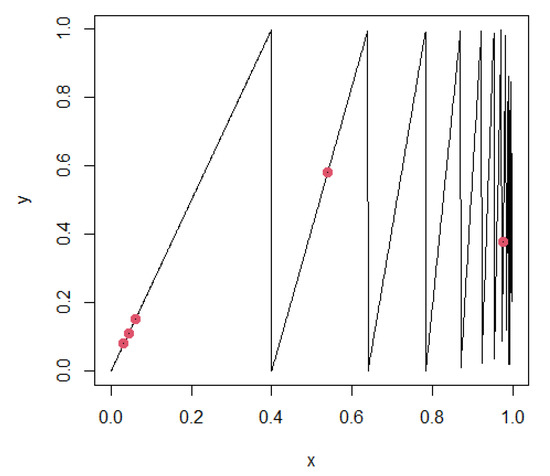

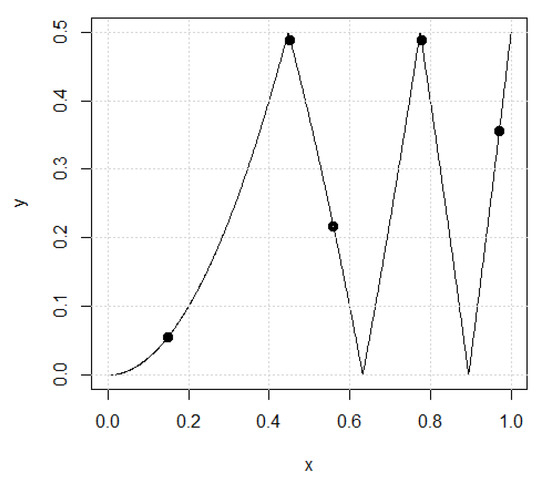

Counterexample 2.

We define the function f as follows:

Let let the sequence with

Let defined by

for each

In this case, contains the segment ; hence, it has a last element: the point (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

f is not L-acceptable. The set of marked points has a first element, but does not have a last element.

After some calculus, the value of the function for and becomes

Then,

.

Let us notice that Indeed, this inequality is equivalent to

, which is obvious.

Notice that and Thus

It follows that

Moreover, the sequence of functions defined by is decreasing to 0 as . It follows that the sequence itself is decreasing and

According to the monotone convergence theorem ( Beppo Levi),

To conclude, although has a last element and f is not L-acceptable.

The following simple result gives necessary conditions for f to be L (or F or F,L)-acceptable.

Proposition 6.

Let be a measurable function and defined in (31)–(33).

- (a)

- If and there exists an with the property that is differentiable and increasing, then If then f is L-acceptable.

- (b)

- If and there exists an with the property that is differentiable and decreasing, then If then f is F-acceptable.

- (c)

- If there exists an with the property then hence, according to Theorem 1,

Proof. (a) We shall find the exact value of the limit a.

According to (22), Notice that since, according to our hypothesis, for all

Let us change the variable to We can write

Let

As thus, according to Proposition 5 (1)

The proof for (b) is similar.

(c) Let and be fixed.

We have

Denote

Then and According to Proposition 3 (2), in order to check that , it is enough to verify that

Let If we take into account that , it follows that ; thus, and

In the same way we obtain that

Let Then either or because otherwise, we have that which is a contradiction of the hypothesis It follows that □

Example 1.

f is L-acceptable but is not F-acceptable.

Let The support of F (meaning the graph of f) has the last element but it does not have a first element since Here, Regarding it can be calculated.

Elementary computations yield

Thus

and On the other hand, hence

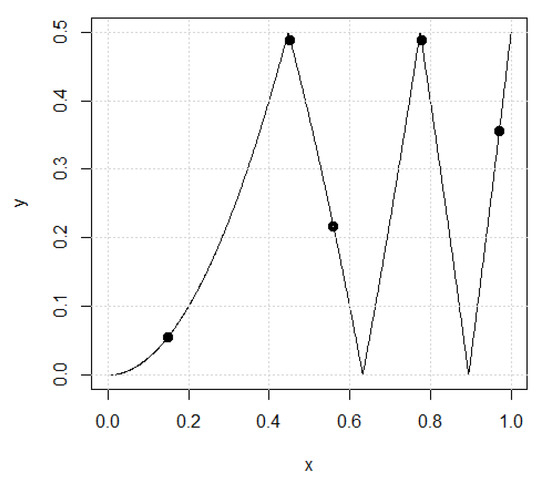

Example 2.

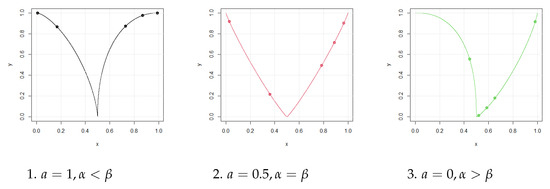

A family of functions where all cases may occur.

Let and the function be defined as:

In order to compute , let be small enough.Then

and with

If we put it follows that

Change the variable to Then,

There are two cases:

A. and are commensurable: are natural numbers. Then, If the limit becomes

Thus, in this case,

B. and are not commensurable. In that case, there exist positive integers such that

For we get

If then hence and the result is the same.

To conclude, (see Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Example 2.

Therefore if F has no leader even if has the last element and f is not L- acceptable. What is interesting is that if then meaning that, in the long run, the occurrence of a leader is sure.

If the function f is not increasing, but it lies in-between two increasing differentiable functions , the following result might help.

Theorem 2.

Let and be increasing and derivable functions such as .

1. If then

2. If then

Proof.

1. Let be fixed and such that The relation implies that ; thus, Then

However, ; therefore,

(since are increasing and ) It results that

and, if we denote

with

According to Proposition 5 (2) mentioned above, It follows that

2. Let be fixed and such that . Then and

It follows that

and, if we denote

with and

Thus (see Proposition 5 (2)) □

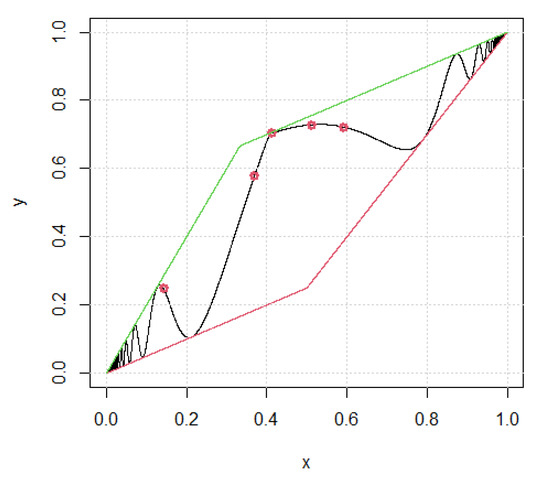

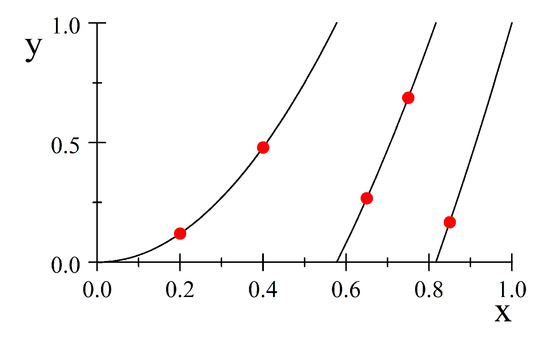

Example 3.

Let where α is the solution of the equation , more exactly

(see Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Example 3.

Then while

Next, we present a class of functions having the property F,L-acceptable.

5. Functions with the Property F, L-Acceptable: Piecewise Monotonous Functions

Definition 3.

The function is called piecewise monotonous if there exist such that the restrictions of f on the interval denoted by are monotonous;

We study two extreme cases.

The first one: alternate monotonicity.

All the restrictions are non-decreasing, while all are non-increasing, with an odd number.

Proposition 7.

Let such that . Suppose that there exists with such that the functions , are differentiable, increasing for odd i and decreasing for even Let then, as long as the formulae (38)–(40) make sense,

Proof.

Let and be fixed. We want to calculate and

For let be such that or, equivalent, Then

For the derivative is

As is odd, is increasing; hence, Moreover, lies between and and j is odd. As on the interval the function is increasing it follows that

On the other hand, lies between and and j is odd. On the interval the function is decreasing hence Therefore

We have Let The integral becomes

According to Proposition 5 (2),

On the other hand where is fixed.

We shall follow the same procedure: for let such as Then

and the derivative is

With the change in variable the integral becomes

According to Proposition 5 (2), we find that

Next, in order to prove that one should check that for x and small enough and that is true according to Proposition 6 (c). □

Example 4. In the particular case that are affine, it is easy to see that and with ,

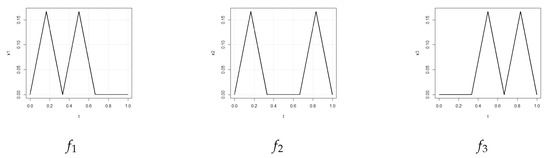

Another example (see Figure 5): . Here ={2,4}

Figure 5.

.

The second case: the same monotonicity.

Proposition 8.

Let such that . Suppose that there exist such that the functions , are differentiable, increasing for every If then, as long as the formulae (41)–(43) make sense,

Proof.

Let and be fixed.

We want to calculate

For let be such that or, equivalent, Then

For the derivative is

As is increasing Therefore,

We have Let The integral becomes

In the same way as in the previous proposition

On the other hand where is fixed.

We shall follow the same procedure: for let such as Then

and the derivative is

With the change in variable the integral becomes

Therefore

The fact that is motivated in the same way as in proposition 7. □

Example 5.

In the particular case that are affine, it is easy to see that and with ,

Another example (see Figure 6): .

Figure 6.

Here ={2}.

Remark 10.

Actually, we do not need all the functions to be differentiable, or even continuous. The only functions that matter are for

Remark 11.

In general, various situations may occur: some of the functions could be increasing, others could be decreasing. Moreover, some of them could be non-increasing or non-decreasing. In all these situations, formulae can be computed but they are very cumbersome and we decided not to consider them.

6. Conclusions and Open Problems

In the paper [1], the authors tried to characterize the d-dimensional distributions F that have the leader property. Some sufficient conditions or necessary conditions were found, but only in two cases: if F is either discrete or continuous. In the unidimensional case, any probability distribution is a mixture between a discrete and an absolutely continuous one. However, in the d-dimensional case, things are much more complicated. Here, we tried to perform a characterization of the distributions with the leader property that are quasi-unidimensional. We found necessary (Proposition 2) or sufficient conditions (Theorem 1, Theorem 2, Proposition 7, Proposition 8). As usual, many open problems appeared:

- We were not able to find examples with c different to .

- How to find a computable criterion to decide if f is L (F, F-L) acceptable. More generally, we say that is L (F,F-L)-acceptable if has the leader, first element, or order property.

- How to characterize the set of L-acceptable functions? A sufficient condition is that is continuous and for some in .

Let with as in the next Figure 7.

Figure 7.

An example of functions such as the pairs , , have leader, but the vector has no leader.

Then the functions , , are as follows (Figure 8):

Figure 8.

Comparison between pairs of functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and A.M.R.; methodology, G.Z.; software, G.Z.; validation, G.Z. and A.M.R.; resources, G.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and A.M.R.; writing—review and editing, G.Z. and A.M.R.; supervision, G.Z. and A.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Răducan, A.M.; Rădulescu, C.Z.; Rădulescu, M.; Zbaganu, G. On the Probability of Finding Extremes in a Random Set. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanin, V.M. Estimate of the mathematical expectation of the number of elements in a Pareto set. Cybernetics 1975, 1975 11, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B. The number of outcomes in the Pareto-optimal set of discrete bargaining games. Math. Oper. Res. 1980, 6, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bentley, J.L.; Kung, H.T.; Schkolnick, M.; Thompson, C.D. On the average number of maxima in a set of vectors and applications. J. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 1978, 25, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchta, C. On the average number of maxima in a set of vectors. Inform. Process. Lett. 1989, 33, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golin, M.J. How many maxima can there be? Comput. Geom. 1993, 2, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, A.D.; Xia, A. The number of two-dimensional maxima. Adv. Appl. Probab. 2001, 33, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bai, Z.D.; Hwang, H.K.; Liang, W.Q.; Tsai, T.H. Limit theorems for the number of maxima in random samples from planar regions. Electron. J. Probab. 2001, 6, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsund, A. Notes on the variance of the number of maxima in three dimensions. Random Struct. Algorithms 2003, 22, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.D.; Chao, C.C.; Hwang, H.K.; Liang, W.Q. On the variance of the number of maxima in random vectors and its applications. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1998, 8, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.D. Stochastic Simulation; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).