Abstract

The transmission of a vertex v of a graph G is the sum of distances from v to all the other vertices of G. A transmission irregular graph (TI graph) has mutually distinct vertex transmissions. In 2018, Alizadeh and Klavžar posed the following question: do there exist infinite families of regular TI graphs? An infinite family of TI cubic graphs of order , , was constructed by Dobrynin in 2019. In this paper, we study the problem of finding TI cubic graphs for an arbitrary number of vertices. It is shown that there exists a TI cubic graph of an arbitrary even order . Almost all constructed graphs are contained in twelve infinite families.

Keywords:

cubic graph; graph invariant; vertex transmission; transmission irregular graph; Wiener complexity MSC:

05C12; 05C09

1. Introduction

All graphs considered in this paper are simple, i.e., they are finite, connected, undirected and without loops or multiple edges. The cardinality of the vertex set of a graph G is called the order of G. The degree of a vertex v is the number of edges adjacent to v. A graph is regular if every vertex has the same degree. All vertices of a cubic or 3-regular graph have degree 3. The class of cubic graphs is especially interesting for theoretical studies and applications because various problems in graph theory remain difficult for this class. Cubic graphs are suitable models for chemical structures, in particular, for fullerenes that form carbon polyhedral cages [1]. If u and v are vertices of G, then the number of edges in a shortest path connecting them is the distance between u and v. The sum of distances from a vertex v to all the other vertices of a graph is called the transmission of v. Vertex transmissions are often used for designing various distance-based topological indices that have found numerous applications in organic chemistry and in the analysis of complex networks. For example, the Wiener index is a half of the sum of all vertex transmissions. It is used as a structural descriptor for molecular graphs of chemical compounds [2,3]. The measure of transmission diversity in a graph is the Wiener complexity, which is defined as the number of pairwise distinct transmissions of graph vertices [4,5,6,7,8]. The Wiener complexity was studied for various classes of graphs. In particular, the Wiener complexity of molecular graphs of fullerenes was considered in [5,9]. A transmission irregular graph (TI graph) has maximum Wiener complexity. It was shown that almost all graphs are not transmission irregular [10]. Infinite families of TI graphs for trees, 2-connected graphs, homeomorphic graphs, and other classes of graphs were constructed in [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The following problem was formulated in [10]: do there exist infinite families of regular TI graphs? An infinite family of transmission irregular cubic graphs of order , , was presented in [16]. The number of vertices of graphs in this family increases by 72.

In this paper, we deal with the problem of constructing a TI cubic graph with an arbitrary even order. It is shown that TI cubic graphs of order can be generated by twelve infinite families except for twenty graphs.

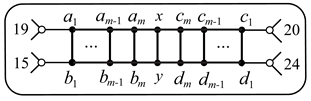

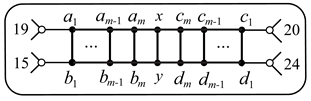

2. Constructions of Graphs

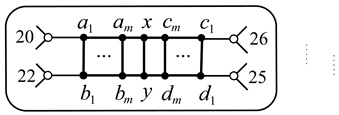

Transmission irregular cubic graphs with a small number of vertices can be found by computer search. There are no such graphs up to 20 vertices. Cubic graphs with 22, 24, 26, 28, and 30 vertices contain 1, 34, 329, 3579, and 41,171 TI graphs, respectively. Examples of cubic TI graphs of order 22 and 24 are shown in Figure 1. Their vertex transmissions are (56, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 67, 70, 71, 73, 74, 77, 78, 80, 81, 85, 86, 88, 89, 93) and (66, 67, 70, 71, 72, 74, 75, 77, 78, 81, 83, 84, 87, 88, 89, 91, 92, 93, 95, 98, 99, 105, 108, 117).

Figure 1.

Transmission irregular cubic graphs with 22 and 24 vertices.

To solve our problem, we find twenty infinite families of TI cubic graphs and show that orders of these graphs cover the set of all even integers except twenty numbers. A TI graph of any constructed family is obtained by connecting a some TI graph H of small order and a growing graph L with a periodic structure depending on some increasing parameter k. Therefore, the method for solving this problem can be divided into four stages:

(s1). finding small finite sequences of growing graphs that could be initial parts of infinite sequences of TI cubic graphs. The orders of graphs of these families depend on k and they must cover almost the entire set of even numbers;

(s2). derivation of analytical expressions for vertex transmissions of graph corresponding to every family in terms of k;

(s3). verification of the property of transmission irregularity by comparing the analytical formulas of vertex transmissions for every ;

(s4). confirmation of the correctness of the analytic formulas by computer calculations of vertex transmissions for graphs of large orders.

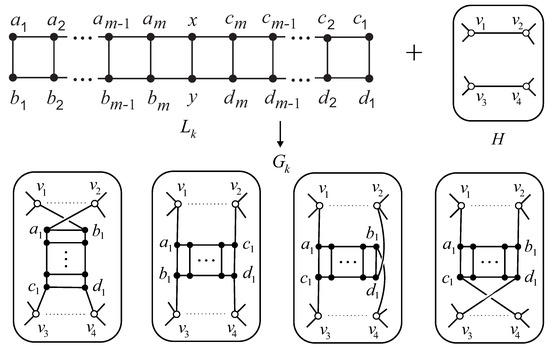

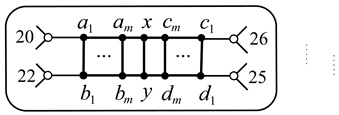

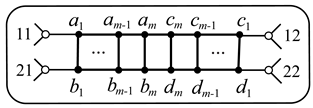

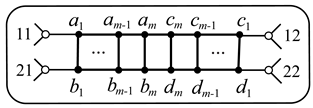

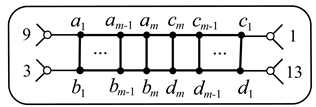

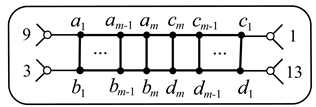

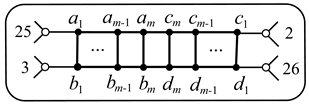

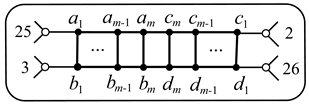

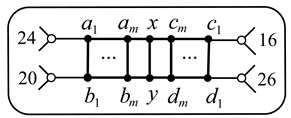

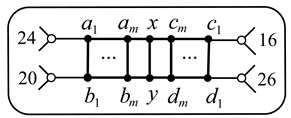

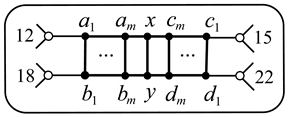

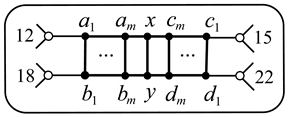

The simplest growing graph suitable for insertion into cubic graphs is the ladder. The ladder of length k consists of two paths in which k pairs of opposite vertices are joined by edges. In other words, is the Cartesian product of paths and . An example of ladder of odd length is depicted in Figure 2, , . For convenience, the vertex numbering of the ladder will go from the vertices of degree 2 to the middle of the ladder. For a ladder of odd length, an edge equidistant from vertices of degree 2 will be denoted as . If , then the corresponding ladder of length 1 consists of edge .

Figure 2.

Examples of inserting ladder into graph H.

The computing search algorithm for finding the initial parts of the infinite families contains the following steps:

(a1). Remove two arbitrary disjoint edges and of a suitable TI cubic graph H of small order n, i.e., vertices , , , and have degree 2 in H;

(a2). Insert edges , , between vertices of ladder and the graph H. The resulting cubic graph has order (see examples in Figure 2 where removed edges are depicted by dotted lines in H). If H and are connected, say, by edges , , , and , then we will use the notation ;

(a3). Check the periodicity of the occurrence of transmission irregular graphs of order while increasing k. If k has a fixed increment, then put k to set K;

(a4). Select such that integers form the set of all even numbers except for a finite subset.

We do not find suitable initial TI graphs of small order among TI cubic graphs of order 24. The required graphs H were selected in the set of TI cubic graphs of order 26 (12 graphs). By attaching growing ladders to all pairs of disjoint edges in all twelve TI graphs H, one may construct the initial parts of possible infinite families.

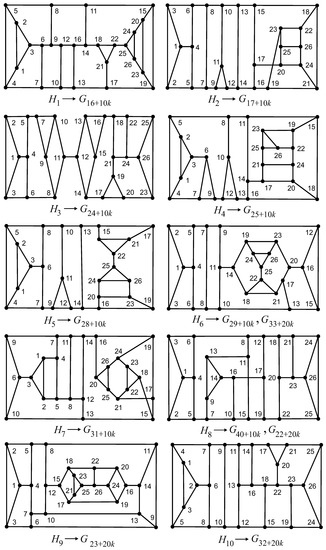

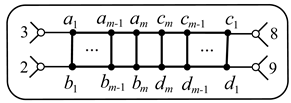

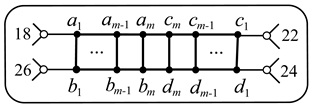

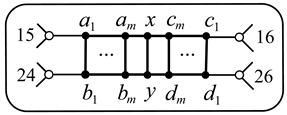

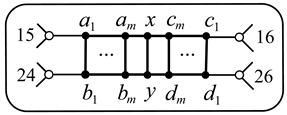

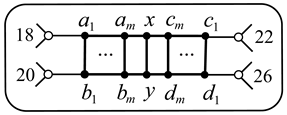

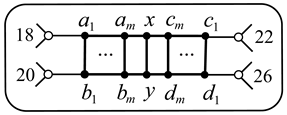

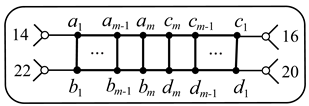

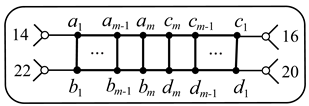

Consider TI cubic graphs of order 26 shown in Figure 3 (graphs , , and are non-planar). By inserting ladders of various lengths to these graphs, one can construct the following twelve infinite families of cubic graphs, :

Figure 3.

Transmission irregular cubic graphs of order 26.

Since the length of the growing parts of ladders is divisible by 10, it is easy to check the following property.

Proposition 1.

The union of infinite sets and , , covers the set of all positive integers except for , .

Twenty numbers outside the infinite families of Proposition 1 determine the length of ladders to be inserted into cubic graphs H of order 26. Therefore, the corresponding twenty cubic TI graphs will have orders .

To construct such graphs, it is sufficient to consider graphs and in Figure 3. Namely, it can be verified that the following cubic graphs are transmission irregular:

Computer calculations confirm that these graphs are transmission irregular. Their ordered vertex transmissions are presented in Appendix B. Note that cubic graphs always have an even number of vertices. Graphs together with two graphs of Figure 1 and graphs from infinite families lead to the following result.

Proposition 2.

A transmission irregular cubic graph of order n exists for all even .

3. Vertex Transmissions of Cubic Graphs

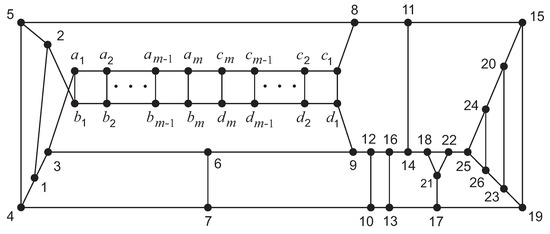

To prove Proposition 2, we find analytical expressions for vertex transmissions of every growing graph of Figure 3 as polynomials in k and then compare them with each other. The basic idea of analytic calculation of transmissions is to study how the shortest paths go through vertices of ladders. The shortest paths from graph vertices can enter the ladder through four vertices , and . This rather cumbersome method is described in detail for regular graphs of degree 3 and 4 in [16,17].

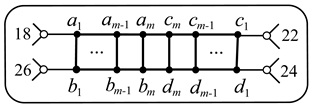

As an illustration, consider graph of Figure 4 obtained from cubic graph of Figure 3 and calculate transmission of vertex 6. Denote by the sum of distances from a vertex v to vertices of a set U. Let and . Then . It is easy to see that the sum of distances from vertex 6 to all vertices of does not depend on the length of ladder . We have . The shortest paths from vertex v to vertices of pass through the cycle of length with vertex set . Then , where is the transmission of vertex 6 in cycle . The shortest paths from vertex v to vertices of pass through the cycle with vertex set . Hence, . As a result, we obtain .

Figure 4.

Graph with a growing ladder, .

Graph has the following vertex transmissions, :

To check that there are no pairs of vertices with the same transmissions, one can examine k and i as solutions of the corresponding equalities. Note that the coefficients at k of transmissions of vertices form a non-decreasing sequence, while the sequence of constant terms strictly increases. Therefore, the equality of any two transmissions implies . The other possible equalities of transmissions lead to various invalid expressions. For example, or , etc. Transmissions of vertices , and have the same incremental value and coinciding coefficients at and k. The pairwise difference of these transmissions is provided by the difference in the remaining constant terms.

Expressions for vertex transmissions of TI cubic graphs of the infinite families are collected in Appendix A. These expressions have been additionally verified by computing vertex transmissions of all graphs using their adjacency matrices for ladders with . The ordered vertex transmissions of twenty TI cubic graphs outside the constructed infinite families are presented in Appendix B.

4. Conclusions

It is shown that transmission irregular cubic graphs can have an arbitrary even number of vertices . A full list of TI cubic graphs with up to 30 vertices is also obtained (available upon request to the authors). The next natural step is to find TI quartic or 4-regular graphs for an arbitrary order. Regular graphs of degree 4 are also of interest for chemical applications. An infinite family of TI quartic graphs of order , , with a quite complicated structure is known [17]. The question of the existence of a transmission irregular fullerene graph is still open [9]. For computer calculations, the authors have developed software tools in programming languages Python, C++ and Delphi.

Author Contributions

Methodology and theoretical study, A.A.D.; software and computational support, A.Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the state contract of the Sobolev Institute of Mathematics (grant FWNF-2022-0017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Vertex Transmissions of TI Cubic Graphs of Twelve Infinite Families

1. Graphs , , .

2. Graphs , , .

3. Graphs , , .

4. Graphs , , .

5. Graphs , , .

6. Graphs , , .

7. Graphs , , .

8. Graphs , , .

9. Graphs , , .

10. Graphs , , .

11. Graphs , , .

12. Graphs , , .

Appendix B. Vertex Transmissions of TI Cubic Graphs Outside of Infinite Families

- Graph (28 vertices)82, 84, 87, 88, 91, 94, 95, 96, 98, 99, 101, 104, 105, 108, 109, 111, 112, 113, 115, 120, 121, 124, 125, 126, 133, 136, 146, 155

- Graph (30 vertices)89, 90, 92, 95, 97, 99, 100, 102, 103, 105, 106, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 122, 123, 129, 130, 131, 132, 135, 141, 142, 144, 150, 155

- Graph (32 vertices)105, 108, 110, 111, 112, 114, 116, 118, 119, 120, 121, 124, 127, 129, 133, 134, 135, 137, 138, 146, 147, 148, 152, 153, 155, 157, 167, 168, 169, 173, 175, 177

- Graph (34 vertices)107, 110, 111, 117, 119, 120, 123, 124, 125, 127, 128, 130, 132, 133, 135, 136, 137, 138, 140, 141, 143, 148, 149, 150, 151, 153, 160, 161, 163, 165, 169, 173, 174, 184

- Graph (36 vertices)126, 127, 133, 134, 135, 141, 143, 145, 146, 147, 148, 150, 151, 158, 159, 160, 165, 166, 167, 169, 172, 179, 180, 186, 188, 189, 190, 192, 193, 200, 204, 208, 209, 214, 215, 219

- Graph (38 vertices)127, 130, 131, 132, 133, 135, 139, 140, 146, 147, 148, 149, 151, 155, 156, 160, 162, 167, 169, 170, 171, 172, 175, 177, 178, 179, 183, 186, 187, 190, 191, 195, 197, 200, 204, 213, 214, 223

- Graph (40 vertices)147, 152, 155, 158, 163, 165, 166, 170, 172, 173, 175, 177, 180, 181, 182, 186, 191, 193, 196, 198, 199, 201, 204, 206, 212, 214, 217, 219, 220, 228, 230, 231, 233, 234, 240, 245, 248, 259, 260, 264

- Graph (42 vertices)148, 154, 155, 156, 159, 160, 161, 164, 168, 171, 175, 176, 181, 186, 188, 189, 190, 195, 196, 203, 204, 205, 207, 208, 210, 212, 214, 217, 220, 222, 224, 225, 227, 228, 229, 233, 235, 237, 246, 255, 256, 265

- Graph (44 vertices)172, 179, 181, 182, 183, 185, 186, 192, 193, 194, 197, 198, 200, 201, 203, 204, 206, 211, 215, 216, 219, 224, 228, 229, 230, 232, 237, 240, 242, 245, 249, 252, 255, 260, 261, 263, 265, 272, 276, 285, 297, 300, 322, 335

- Graph (46 vertices)176, 180, 185, 186, 187, 190, 192, 194, 195, 196, 200, 201, 206, 211, 214, 215, 217, 218, 221, 222, 226, 229, 234, 235, 236, 237, 241, 242, 244, 246, 249, 255, 260, 263, 264, 268, 269, 274, 275, 278, 279, 283, 289, 303, 304, 319

- Graph (48 vertices)191, 200, 202, 204, 211, 218, 220, 223, 224, 228, 229, 233, 234, 239, 241, 243, 246, 249, 250, 252, 255, 261, 262, 265, 268, 271, 275, 277, 280, 282, 283, 284, 289, 292, 297, 298, 303, 304, 307, 313, 314, 315, 316, 318, 333, 351, 352, 356

- Graph (50 vertices)205, 210, 215, 216, 219, 223, 224, 225, 230, 231, 232, 234, 235, 242, 244, 247, 249, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 261, 264, 268, 273, 274, 275, 278, 280, 285, 287, 288, 294, 295, 299, 306, 309, 310, 313, 314, 318, 323, 324, 325, 326, 332, 348, 349, 366

- Graph (52 vertices)229, 238, 243, 246, 253, 255, 258, 262, 265, 267, 268, 275, 276, 278, 280, 282, 284, 287, 290, 292, 300, 304, 306, 307, 308, 309, 312, 326, 328, 331, 334, 337, 343, 345, 348, 350, 353, 356, 370, 372, 373, 375, 377, 381, 382, 385, 392, 397, 413, 422, 423, 427

- Graph (54 vertices)256, 259, 261, 262, 267, 270, 276, 277, 278, 279, 280, 287, 294, 298, 299, 301, 305, 308, 314, 316, 319, 321, 323, 329, 331, 337, 340, 343, 345, 350, 361, 363, 365, 367, 371, 374, 376, 382, 387, 389, 392, 401, 403, 409, 410, 411, 414, 415, 418, 431, 443, 457, 458, 462

- Graph (56 vertices)262, 272, 275, 280, 282, 285, 287, 288, 293, 295, 298, 299, 300, 301, 303, 307, 308, 309, 311, 313, 315, 316, 320, 326, 328, 331, 335, 340, 345, 347, 348, 353, 355, 360, 364, 366, 371, 375, 380, 383, 385, 393, 394, 400, 402, 404, 409, 414, 416, 418, 420, 423, 430, 462, 465, 479

- Graph (62 vertices)338, 339, 343, 344, 346, 348, 351, 352, 354, 355, 368, 369, 371, 373, 374, 376, 390, 391, 392, 393, 397, 398, 407, 411, 412, 413, 418, 420, 431, 433, 434, 442, 450, 451, 453, 456, 461, 464, 471, 473, 478, 486, 491, 493, 495, 499, 500, 506, 508, 510, 511, 513, 521, 522, 530, 541, 545, 546, 557, 559, 581, 608

- Graph (64 vertices)350, 354, 356, 359, 360, 364, 368, 374, 376, 377, 379, 381, 382, 383, 386, 390, 392, 393, 395, 398, 399, 402, 404, 407, 408, 412, 419, 423, 430, 433, 434, 439, 440, 444, 452, 456, 461, 465, 466, 474, 478, 480, 482, 483, 486, 496, 500, 503, 507, 509, 518, 522, 524, 528, 533, 539, 540, 544, 554, 562, 587, 590, 619, 645

- Graph (66 vertices)375, 380, 391, 392, 398, 399, 401, 403, 404, 406, 411, 414, 419, 421, 433, 434, 436, 437, 441, 443, 455, 458, 463, 465, 468, 471, 474, 477, 480, 485, 487, 499, 500, 502, 507, 509, 518, 521, 524, 529, 531, 543, 544, 546, 551, 553, 565, 567, 568, 569, 573, 575, 587, 590, 594, 595, 597, 609, 617, 619, 620, 623, 648, 674, 675, 679

- Graph (68 vertices)388, 391, 399, 400, 409, 415, 416, 419, 423, 424, 425, 427, 429, 431, 432, 433, 434, 436, 439, 441, 448, 449, 451, 452, 456, 459, 469, 471, 472, 476, 479, 489, 490, 491, 496, 499, 509, 511, 516, 519, 523, 527, 529, 531, 536, 539, 541, 545, 549, 551, 556, 559, 569, 571, 576, 579, 580, 582, 589, 591, 594, 596, 597, 598, 607, 611, 628, 637

- Graph (86 vertices)666, 672, 675, 680, 681, 685, 686, 687, 688, 689, 695, 701, 703, 704, 707, 708, 709, 718, 719, 721, 723, 727, 728, 740, 741, 743, 747, 748, 750, 761, 763, 767, 768, 781, 783, 787, 788, 801, 803, 806, 807, 808, 813, 821, 823, 827, 828, 841, 843, 847, 848, 861, 863, 867, 868, 870, 872, 881, 882, 883, 887, 888, 901, 903, 907, 908, 921, 923, 927, 928, 935, 941, 943, 947, 948, 957, 961, 963, 967, 968, 982, 1010, 1033, 1036, 1089, 1113

References

- Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E. An Atlas of Fullerenes; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, I.; Polansky, O.E. Mathematical Concepts in Organic Chemistry; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Trinajstić, N. Chemical Graph Theory; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Abiad, A.; Brimkov, B.; Erey, A.; Leshock, L.; Martínez-Rivera, X.; Suil, O.; Williford, J. On the Wiener index, distance cospectrality and transmission-regular graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 2017, 230, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Andova, V.; Klavžar, S.; Škrekovski, R. Wiener dimension: Fundamental properties and (5,0)-nanotubical fullerenes. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2014, 72, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Klavžar, S. Complexity of topological indices: The case of connective eccentric index. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2016, 76, 659–667. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Estaji, E.; Klavžar, S.; Petkovšek, M. Metric properties of generalized Sierpiński graphs over stars. Discrete Appl. Math. 2019, 266, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavžar, S.; Jemilet, D.A.; Rajasingh, I.; Manuel, P.; Parthiban, N. General transmission lemma and Wiener complexity of triangular grids. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 338, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A.; Vesnin, A.Y. On the Wiener complexity and the Wiener index of fullerene graphs. Mathematics 2019, 7, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alizadeh, Y.; Klavžar, S. On graphs whose Wiener complexity equals their order and on Wiener index of asymmetric graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 328, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yakoob, S.; Stevanović, D. On transmission irregular starlike trees. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 380, 125257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yakoob, S.; Stevanović, D. On interval transmission irregular graphs. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 68, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of 2-connected transmission irregular graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 340, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of transmission irregular trees of even order. Discrete Math. 2019, 342, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Klavžar, S. Constructing new families of transmission irregular graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 2021, 289, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrynin, A.A. Infinite family of 3-connected cubic transmission irregular graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 2019, 257, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezhaev, A.Y.; Dobrynin, A.A. On quartic transmission irregular graphs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 399, 126049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).