Abstract

In biomedical studies involving time-to-event data, a subject may experience distinct types of events. We consider the problem of estimating the transition functions for a semi-competing risks model under illness-death model framework. We propose to estimate the intensity functions by maximizing a B-spline based sieve likelihood. The method yields smooth estimates without parametric assumptions. Our proposed approach facilitates easy computation of the covariance of the model parameters and yields direct interpretation. Compared with existing approaches, our proposed method requires neither the subjective specification of the frailty distribution nor the Markov or semi-Markov assumption which may be unmet in real applications. We establish the consistency, the convergence rate, and the asymptotic normality of the proposed estimators under some regularity conditions. We also provide simulation studies to assess the finite-sample performance of the proposed modeling and estimation strategy. A real data application is further used to illustrate the proposed methodology.

Keywords:

asymptotics; B-spline; illness-death model; Markov model; proportional hazards; semi-competing risks data MSC:

46N30; 65C60

1. Introduction

In survival analysis, a subject may experience several distinct types of failures. If apart from censoring, the follow up period ends upon the occurrence of the first event, such data are often referred to as competing risks data. This framework consists of survival data where failure may be due to one of a number of competing causes. In some application, with additional information, this notion can be extended to accommodate that of semi-competing risks ([1,2]), where one type of event (terminal event, e.g., death) may censor the other events (non-terminal event, e.g., relapse of the disease), but not vice versa. The framework of semi-competing risk data have been previously discussed in [1,3]. Furthermore, competing risks data can also be regarded as a special type of multitask prediction problem, which simultaneously predicts multiple outcomes from the same set of predictors. A stacking algorithm borrowing information among multiple prediction tasks to improve multivariate prediction performance (MTPS) is recently proposed by [4]. The MTPS is shown to outperform existing multivariate prediction methods.

Recently [5] suggests that semicompeting risks data can also be analyzed using the conventional illness–death compartment model by a subjective specification of the frailty distribution and postulating the Markov or semi-Markov assumption for the conditional transition functions given the covariates and the frailty ([6,7]). However, the subjective specification of the frailty distribution or the Markov or semi-Markov assumption may be unmet in some practical applications, leading to inconsistent estimators. In such cases, alternative (non-Markov) estimators are needed. Furhthemore, their nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation approach may be computational demanding when the sample size is large.

To address the theoretical and numerical challenges in the semiparametric estimation of semi-competing risks model, we employ the B-spline based sieve maximum likelihood approach to simultaneously estimate the regression parameters and transition functions. Covariates are incorporated naturally via proportional hazards assumptions. This approach facilitates easy calculation of the covariance of the model parameters. The proposed spline estimation algorithm requires much less computation than the isotonic type algorithm used in [5] since the size of the step function is much larger than the number of parameters in our proposed B-spline based approach. Under certain regularity conditions, we are able to prove that the estimators of regression parameters is root-n consistent, asymptotically normal and semiparametric efficient.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we will introduce our proposed model and estimating approach. In Section 3, we study the asymptotic properties of the proposed estimators. In Section 4, we provide simulation results. An application to colon cancer data is given in Section 5. We then conclude with some discussion in Section 6. All proofs are relegated to the Appendix A.

2. Methodology

2.1. Model and Likelihood Function

For the ith subject, let , , , and denote the censoring, covariate vector, non-terminal event time, and terminal event time, respectively. Define , and . We observe . The hazard functions are defined as below.

where . In general, can depend on both and (see Remark 1 for more detailed discussions). Let and . Specifically, the probability measure P refers to the joint distribution of in the unconditional case. In the conditional case, the probability measure P refers to the joint distribution of given X. For the unconditional case, the likelihood function then takes the form

where will be specified as follows.

For the case with q dimension covariates X, the conditional transition rate functions are defined as follows:

Note that both x and X refer to the covariates where X denote the random variable and x refers to its observed values. The Equations (5)–(7) are the conditional transition functions of and (given ) while the Equations (1)–(3) are the unconditional transition functions of and .

To simplify the notation, denote Note that in our modeling approach, depends on two parameters t and s.

2.2. Sieve Space for the Parameters

We propose a sieve space consisting of B-splines for in maximizing (4). We suppose that and have compact supports (say ) and that for a known constant Rewrite . Let and A sieve space consisting of B-splines is defined for these new parameters as follows: First, we obtain an extended partition with equal length for the interval

where m (independent of the sample size n) and are two integers to be chosen later. Note that m and are two parameters often used in B-spline modeling where m indicates the smoothness of the basis function. Let and be a normalized B-spline basis associated with (see [8]). Then the sieve space for the parameters is defined as

where with a constant arbitrarily close to m.

For any we define a distance

Remark 1.

Here we assume that the transition intensity depends on both and . A semi-Markov process specifies that However, it is important to note that in either Markov or semi-Markov approaches, depends on only one parameter, corresponding to the special cases of our modeling approach where can flexibly depend on two parameters.

2.3. Maximization

Let P denote the empirical measure and the true probability measure of respectively. We maximize the function

over the sieve space

For the knot selection, we let and use the Bayesian information criterion

to choose which minimizes the criterion function.

3. Theoretical Properties

In this section, we establish the theoretical properties of our spline-based modeling strategy under the following regularity conditions.

Assumptions

- (A1) and have compact supports (say ) and X has bounded support in where q is the dimension of Moreover, if there exists a constant and a constant vector such that almost surely, then and

- (A2) where is a compact set of with nonempty interior. and and

- (A3) where satisfies the restrictions

- (A4) where r is the measure of smoothness of in definitions of and

We first establish the strong consistency for the estimated model parameters.

Theorem 1.

Under Assumptions A1–A3, are strong consistent estimators of the true coefficients and almost surely.

Next, we obtain the convergence rates for the proposed estimators.

Theorem 2.

Under Assumptions A1–A3, it holds that

This theorem implies that if which is the optimal convergence rate in the non-parametric regression setting for bivariate function estimation by [9].

To derive the limiting distribution of the proposed estimators, establish the asymptotic normality, we calculate the directional derivative of the log-likelihood in the associate functional spaces as follows.

Denote V as the linear span of where denote the true value of and denote the true parameter space. Let be the log-likelihood for a sample of size one and For any define the first order directional derivative of at the direction as

and the second order directional derivative as

Define the Fisher inner product on the space V as

and the Fisher norm for as Let be the closed linear span of V under the Fisher norm. Then is a Hilbert space.

Define the smooth functional of as

where b is any vector of dimension with For any we denote

whenever the right hand-side limit is well defined and assume:

- (A5) for any is continuously differentiable in near and

Note that Under Assumption A5, by the Riesz representation theorem, there exists such that for all and

Theorem 3.

Suppose suppose and assumptions A1–A3, A5 hold, then in distribution and and is semiparametrically efficient.

Remark 2.

Inference about .Theorem 3 offers ease of inference procedure, especially for the regression parameter β. Set , then Theorem 3 yields that and thus

by Gramer-Wold device, one can establish semiparametricefficiency of where can be consistently estimated using the inverse of the Hessian matrix.

Remark 3.

Inference about . For let and then Theorem 3 yields that

where can be consistently estimated by using the delta method or some resampling methods. Similarly inference can be done for : Let then Theorem 3 yields that

where can be consistently estimated by using the delta method or some resampling methods. The above results can be used to check the linear (quadratic) effect of , or to check whether is an additive form of and

4. Simulation Study

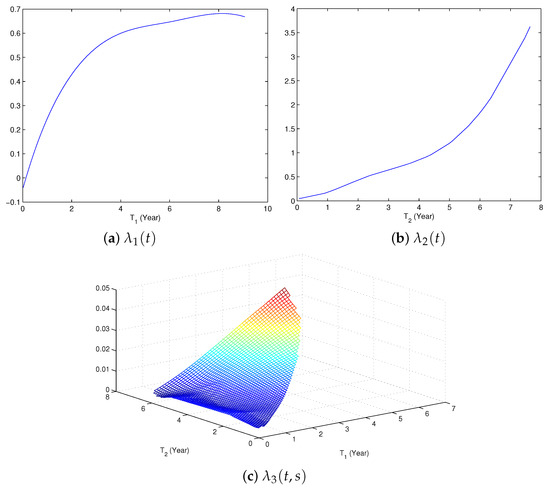

We conducted simulations to investigate finite sample performance of the proposed estimator. In the simulation, we let

By calculation, it is clear that the stipulated transition functions do not follow the transition functions from the models involving the frailty distribution and Markov or semi-Markov modells ([1,5]). It is therefore of interest to examine whether the proposed spline-based estimation procedure still yields reliable and accurate estimates for this scenario which cannot be tackled by existing approaches. We report results with one covariate, X, having a uniform. distribution between 0 and We consider and and The censoring time was simulated from from a uniform distribution on with We compute the spline based semiparametric maximum likelihood estimate using the cubic B-spline and estimate the standard error of the estimated regression parameter using the inverse of the Hessian matrix. For the B-spline, the number of knots or equivalently is chosen using BIC defined in Section 2.3. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 presents the estimation bias (BIAS), standard deviations (STD), the mean of the estimated standard error of the estimated regression parameter(ESE) and the coverage proportion of the 95 percent confidence intervals (CP) based on 500 replicates.

Table 1.

Simulation results for .

Table 2.

Simulation results for .

Table 3.

Simulation results for .

From Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, we can see (a) the proposed estimates have very small biases; (b) standard deviations of the estimates shrink at approximately the rate; (c) the estimated standard deviations are very close to those of the original estimates; the 95 percent confidence intervals provide adequate coverage probabilities. It can be seen that the proposed modeling strategy and estimation procedure can yield reliable and accurate estimates and exhibit direct and good interpretation in practice.

5. A Real Data Example

As our proposed B-spline based modeling strategy does not involve the subjective specification of the frailty distribution and do not require the Markov or semi-Markov assumption which may be unmet in real applications, it is hence more flexible than existing approaches in practice. To illustrate this point, we now apply the illness-death model presented in Section 2 to the colon cancer data. It is of interest to examine whether the time spent in state 1 (past) is related to the transition function from state 2 into state 3. For answering this question, we consider a working model . It translates to test This can be done using the usual likelihood ratio statistic. The results obtained for the colon cancer study show that the effect of time spent in state 1 is significant (p-value ). This allows us to conclude that the Markov assumption may be unsatisfactory for the colon cancer data set. This further demonstrate the stringent assumptions required by existing approaches may be unmet in practice which calls for the need of our proposed methodology.

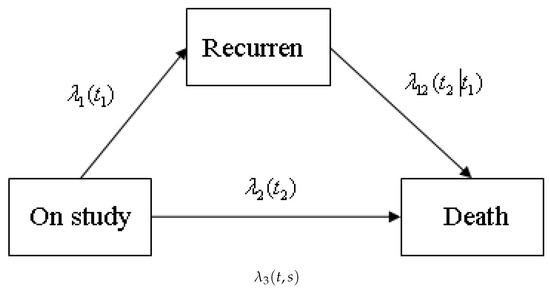

For illustrative purposes, we only consider one covariates: Lev+5-FU treatment. Our interest centers on understanding the effect of Lev+5-FU treatment and nonparametricall modelling transition functions in different states. Table 4 reports the estimates of the regression coefficients along with standard errors and p-values. From Figure 1 and Figure 2, we can see our proposed model and estimation procedure yield the estimated transition functions with direct and good interpretation. It stipulates quantitatively how the hazard functions of the time to terminal event and the time to non-terminal event evolves over time and shed lights on the disease progression and death risks for colon cancer patients with and without relapse of the cancer. We plot the estimated the transition functions in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Estimated regression coefficients and their standard errors for the colon data.

Figure 1.

Compartment model for semicompeting risks data.

Figure 2.

Estimated transition functions for the colon cancer data.

Furthermore, to illustrate the computational advantage of our proposed approach, for the real data application, the existing frailty-model approach will require the number of parameters . However, our proposed B-spline approach only require parameters. Hence, the computational cost is substantially reduced while our approach is more flexible than existing approaches because it does not require the subjective specification of the frailty distribution and the Markov or semi-Markov assumption.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we proposed an spline-based sieve semiparametric maximum likeli- hood method for semi-competing risks data. This method reduces the dimensionality of the estimation problem using the splines and therefore releases the numerical burden of the computation. This approach allow essily infer for both regression parameters and transition functions. It should be a straightforward task to apply the method presented here to allow for non-linear relationships between continuous predictors and survival in the multi-state framework ([6,10] and others). Simulations showed that the new estimator may behave very good. For illustration purposes we used a real dataset from a clinical trail for colon cancer. Competing risks data can also be regarded as a special type of multitask prediction problem. In such a field, the most state-of-the-art method is MTPS [4], which currently does not support predicting survival outcomes. Following their approaches, it would be worthwhile studying the stacked algorithm for prediction with multivariate survival outcomes including competing risks and semi-competing risks data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X.; methodology, X.H. and J.X.; software, X.H.; formal analysis, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proofs of Theorem 1, Theorem 2, and Theorem 3

This section contains the proofs for Theorems 1–3. Some empirical process theorems developed in [11] will be repeatedly used. Throughout the following proofs, we denote and the empirical process indexed by function

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 1

By applying the inequality (31) in [12] (p. 31), we have

Let

Denote

If we have

By condition A3, we obtain that It completes the proof.

Appendix A.2. Proof of Theorem 2

Noticing

where The right-hand side of (A6) yields It is easy to see that decreasing in and where Hence by Theorem 3.2.5 of [11]. This, together with (see Theorem 12.7 in [8], yields that . This completes the proofs.

Appendix A.3. Proof of Theorem 3

Let be any positive sequence satisfying For any by [8], Theorem 12.7, there exists such that and Also define Then by definition of we have

By (A1) and Chebyshev inequality, independent and identical distribution data, and we have

For we have

where lies between and It follows that is Donsker class. Therefore, by Theorem 2.11.23 of [11], we have

It follows that and Combing the above facts, together with we can establish that

Therefore, we obtain where the asymptotic normality is guaranteed by Central limits Theorem and the the asymptotic variance being equal to This, together with A5 imply in distribution. The semiparametric efficiency can be established by applying the result of [13].

References

- Fine, J.P.; Jiang, H.; Chappell, R. On semi-competing risks data. Biometrika 2001, 88, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Estimating the association parameter for copula models under dependent censoring. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. Stat. Methodol. 2003, 65, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Bryant, J.; Lefkopoulou, M. Adaptation of bivariate frailty models for prediction, with application to biological markers as prognostic indicators. Biometrika 1997, 84, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Lesperance, M.L.; Zhang, X. Simultaneous prediction of multiple outcomes using revised stacking algorithms. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kalbfleisch, J.D.; Tai, B. Statistical analysis of illness–death processes and semicompeting risks data. Biometrics 2010, 66, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andersen, P.K.; Borgan, O.; Gill, R.D.; Keiding, N. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbfleisch, J.D.; Prentice, R.L. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker, L. Spline Functions: Basic Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C.J. Optimal global rates of convergence for nonparametric regression. Ann. Stat. 1982, 10, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira-Machado, L.; de Uña-Álvarez, J.; Cadarso-Suárez, C.; Andersen, P.K. Multi-state models for the analysis of time-to-event data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2009, 18, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wellner, J. Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes: With Applications to Statistics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, D. Convergence of Stochastic Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, P.J.; Kwon, J. Inference for semiparametric models: Some questions and an answer. Stat. Sin. 2001, 11, 863–886. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).