Abstract

The increasing use of automated feedback in education highlights the need for rigorous validation of AI-based assessment tools, particularly in performance-based domains such as dance. This study examined the validity of the Real-time Augmented Feedback in Learning Tool (ReAL-T), an AI-based scoring engine designed to support screen-based learning and assessment for beginner dancers. Twelve adult beginners completed a learning protocol involving four choreographies, generating 96 recall performances. Three expert choreographers independently rated each performance on a 1–5 scale for body line and form and precision, while ReAL-T generated parallel scores using the same criteria. Inter-rater reliability among choreographers was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W). Agreement between expert ratings and ReAL-T was examined using ICCs and Kendall’s W on a combined overall score. Expert ratings demonstrated excellent agreement across both categories (single-rater ICCs ≥ 0.85; Kendall’s W ≥ 0.87). When ReAL-T was included as an additional rater, agreement remained high (single-measure ICC = 0.84; Kendall’s W = 0.89). These findings indicate that the ReAL-T minimum viable product produces automated scores that closely align with expert judgement, supporting its use as a validated automated feedback component for beginner dance education.

1. Introduction

Interactive learning environments (ILE) increasingly incorporate emerging technologies such as adaptive learning systems, intelligent tutoring, and automated feedback (Wangoo & Reddy, 2021), to make learning more interactive, personalised, and effective (Strielkowski et al., 2025). Within this agenda, automated feedback mechanisms are foundational for real-time guidance, personalisation, and scalable assessment. Across higher education, AI-driven learning tools are being deployed to provide real-time feedback, recommendations, and assessment. However, studies found that many tools function as black boxes, with limited reporting on how their scores are validated against expert judgement (Bates et al., 2020; Glikson & Woolley, 2020; Prinsloo, 2020). This concern extends to automated feedback in online learning environments more broadly, where the design and evaluation of feedback engines have not consistently been grounded in explicit validation frameworks (Luo et al., 2025).

In dance and movement-related disciplines, AI-assisted systems are beginning to support skills teaching, automated evaluation, and visual feedback. Recent work on AI-assisted dance teaching reports positive effects on performance, motivation, and self-efficacy when AI-based evaluation and visual feedback are integrated into instruction (Xu et al., 2025). More broadly, AI-driven feedback systems are being explored in dance education as a means to provide objective, fine-grained analysis of movement (Li, 2025). However, the validity of automated scores in these systems is often only partially documented, with limited systematic comparison to expert choreographers’ ratings.

The Real-time Augmented Feedback in Learning Tool (ReAL-T) was developed as a novel screen-based technology for dance learning and assessment in adult beginner dancers. ReAL-T used pose estimation and algorithmic comparison between learner and expert videos to generate performance scores and exoskeletal overlays that are central to its automated feedback capabilities within a screen-based ILE.

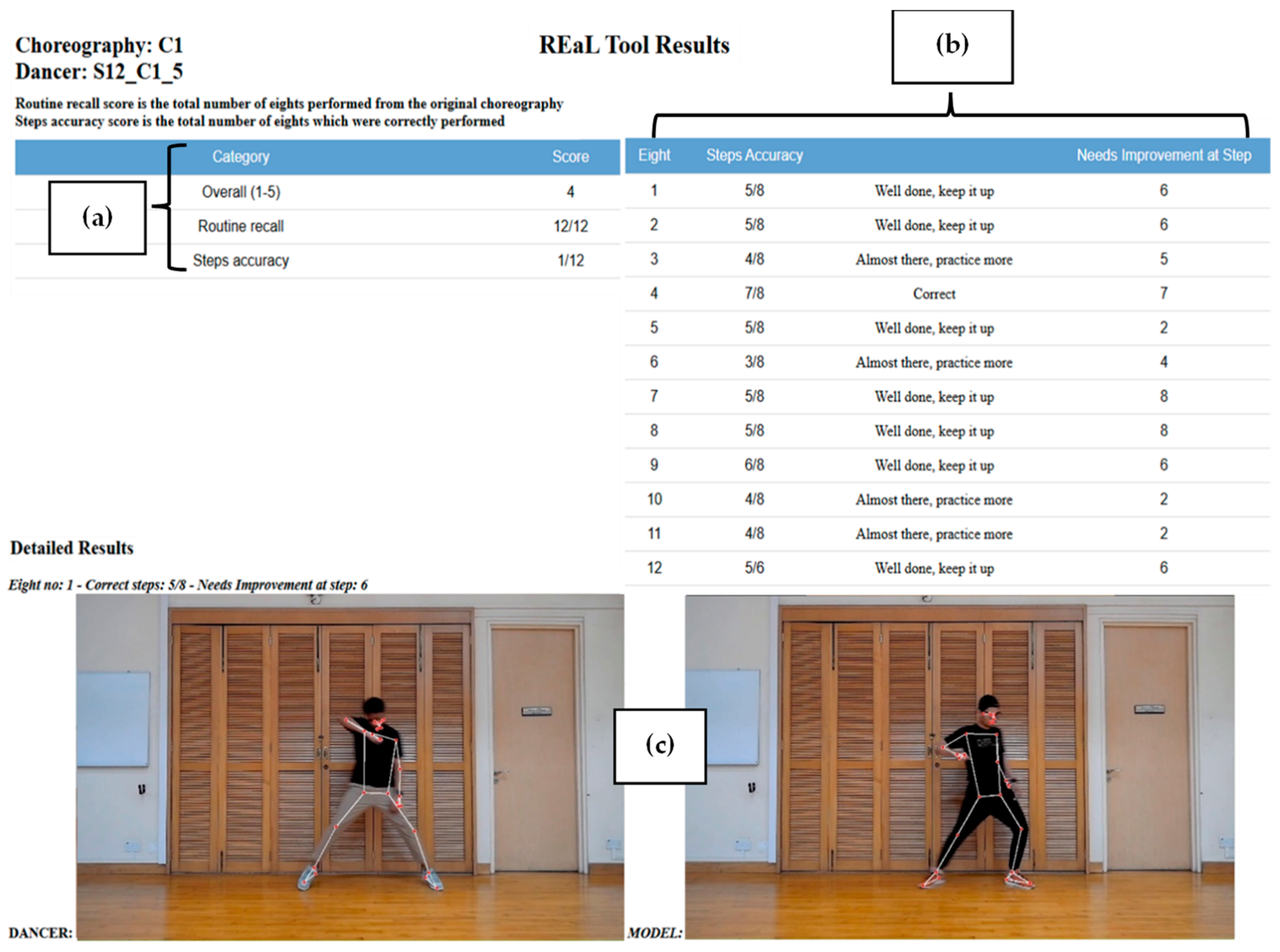

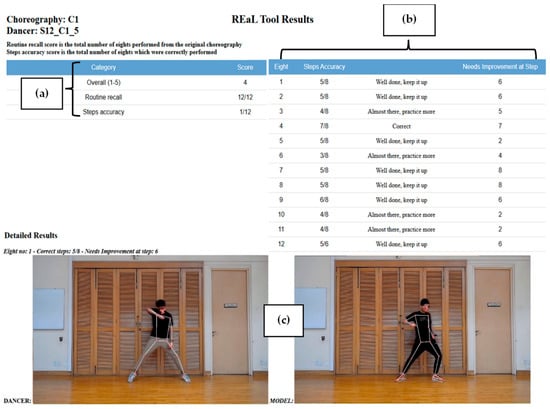

Figure 1 illustrates a screengrab of the ReAL-T interface used during the intervention phase of the study.

Figure 1.

ReAL-T Interface Output. (a) Summary Score Table, (b) Step-by-Step Performance Table and (c) Visual Feedback Comparison. Detailed descriptions of panels (a–c) are provided immediately after Figure 1 below.

The interface provides comprehensive, real-time feedback to learners across multiple dimensions:

- (a)

- Summary Score Table (top left): This section reports the dancer’s overall performance on a 5-point scale, total recall of choreography (measured in 8-beat segments or eighths), and cumulative steps performed accurately. These metrics offer a snapshot of technical accuracy and routine memory.

- (b)

- Step-by-Step Performance Table (top right): Each row corresponds to one eighth of the choreography. This table displays the following:

- i.

- Steps Accuracy: The number of steps correctly performed (5/8 = 5 out of 8 steps correct).

- ii.

- Feedback Comment: A qualitative message encouraging or directing the participant (e.g., “Well done, keep it up”).

- iii.

- Needs Improvement at Step: Pinpoints the specific step within the segment that requires correction.

- (c)

- Visual Feedback Comparison (bottom panel): The left image shows the participant’s performance, overlaid with pose estimation markers; the right image shows the model (teacher) frame for direct comparison. This enables learners to align their body posture, rhythm, and coordination visually with the correct model.

As part of the underlying doctoral research programme, the ReAL-T was developed through iterative design and testing phases that examined its feasibility for supporting short-term learning, assessment accuracy, and personalised feedback in beginner dance contexts. The present article focuses on a specific question: to what extent can ReAL-T’s automated scores be considered valid approximations of expert choreographers’ judgements at the MVP stage of this instrument?

To address this, this article adopted Williamson et al.’s (2012) framework for evaluating automated scoring of constructed-response tasks. Within that framework, one central emphasis area is the empirical performance of automated scoring in relation to human scores, involving the quality of human scoring and the agreement between automated and human scores. Further, the present article focuses exclusively on this emphasis area and addresses two research questions:

- How strongly do three expert choreographers agree when rating beginner dance recall performances using a common rubric?

- To what extent do the ReAL-T’s automated scores align with the experts’ composite scores for the same performances?

By anchoring the analysis in Williamson et al.’s (2012) framework and focusing on human–machine agreement, this article contributes a concrete model of how automated feedback in an AI-driven ILEs can be empirically validated against expert judgement in a motor-skill domain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Dataset

The data for this study were drawn from a broader doctoral investigation that involved the design, development, and evaluation of a novel screen-based system for dance learning and assessment in adult beginner dancers (Johari, 2024); however, the present manuscript reports only the validation analyses relevant to the ReAL-T automated scoring component. Twelve adult beginners completed a structured dance programme involving four dance choreographies of similar difficulty across a 20-day period. Each participant performed a series of learning and recall tasks. For the purposes of the present analysis, only recall scores were considered.

Each participant produced eight recall performances distributed across the four choreographies and specified recall points, resulting in 96 distinct recall videos (12 participants × 8 recall performances). All videos were recorded in a studio with consistent camera placement, lighting, and audio. The ReAL-T system processed each recall performance and stored the corresponding automated score.

Ethical approval IRB 2022-843 was obtained from the Nanyang Technological University’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent for their performances to be used in research and system development.

2.2. Expert Choreographers and Rating Procedure

Three expert choreographers served as human raters. Each had more than 10 years of teaching and performing experience on local and international platforms, including extensive work with beginner-level adults. None of the experts were involved in designing ReAL-T’s algorithm.

All 96 recall videos were presented to the choreographers in randomised order using a secure online interface. Experts worked independently, without access to the ReAL-T scores or to each other’s ratings. For each video, they rated the following:

- Body line and form (clarity of shapes, joint extension, posture)

- Movement precision (accuracy of sequences)

Ratings were recorded on Likert-type scales with descriptors tailored to beginner performance. For analysis, item scores were aggregated into a single composite score per video per expert, yielding 288 expert composite scores (96 videos × 3 experts).

2.3. The ReAL-T Algorithm as an Automated Feedback Engine

The ReAL-T functions as an automated feedback engine within a screen-based ILE.: It is designed to support educational assessment and formative feedback rather than to serve as a general-purpose motion analysis or dance visualisation system. Accordingly, the system prioritises rubric alignment, interpretability, and classroom compatibility, enabling automated scores to be meaningfully compared with expert judgement and used in teaching and learning contexts. In its MVP implementation, the process for each learner’s performance is as follows:

- Video capture. The learner’s performance is captured via a webcam, while an expert reference performance of the same choreography is pre-recorded and stored. This approach enables the system to operate in typical learning environments without specialised hardware.

- Pose estimation and feature extraction. A pose estimation model extracts exoskeletal keypoints from learner and expert videos, from which joint-angle trajectories and related kinematic features are computed in real time. Feature extraction focuses on movement characteristics relevant to dance assessment, such as body configuration and movement trajectories, rather than fine-grained biomechanical modelling.

- Movement alignment and comparison. For each recall performance, the learner’s and expert’s joint-angle trajectories are temporally aligned and compared using a proprietary sequence-comparison algorithm developed for the ReAL-T. The alignment process employs a dynamic time-alignment approach conceptually similar to dynamic time warping, allowing non-linear temporal correspondence between learner and expert trajectories. This approach accommodates natural variability in execution timing among beginner dancers while preserving sensitivity to deviations in movement structure. The algorithm integrates timing correspondence and joint-level kinematic similarity into a single similarity index.

- Score generation. The similarity index is transformed into a performance score on a 1–5 scale, with higher values indicating closer alignment to the expert reference performance. Mapping from the similarity index to the ordinal score is performed using predefined, rubric-aligned cut-points derived through pilot calibration against expert ratings, ensuring consistency with the human assessment scale. This scale is deliberately matched to the 1–5 rubric used by the expert choreographers to facilitate direct comparison between automated and human ratings. Within the ILE, the ReAL-T score, together with visual overlays and side-by-side playback, is presented to learners as automated feedback after each trial.

In contrast to screen-based dance systems that primarily provide visual feedback or AI-based approaches that focus on movement recognition or classification, the ReAL-T is explicitly designed as an assessment-aligned automated feedback engine. Its validation against expert choreographers’ ratings reflects a deliberate emphasis on measurement quality and interpretability, positioning the system to complement, rather than replace, human judgement in dance education.

2.4. Validation Framework

The ReAL-T validation was conceptualised using Williamson et al.’s (2012) framework for evaluation and use of automated scoring. The framework identifies several emphasis areas, including the fit between scoring capability and assessment purpose, associations between automated and human scores, associations with independent measures, generalisability across tasks, and consequences for different populations.

At the MVP stage, this study focuses on a single emphasis area: empirical performance in terms of association with human scores. Within this emphasis area, Williamson et al. (2012) highlight the need to (a) establish the quality and consistency of human scoring, and (b) evaluate the agreement between automated and human scores, including patterns of convergence and divergence.

Accordingly, the present validation proceeds in two steps:

- Human scoring quality. Inter-rater agreement among the three expert choreographers was examined to ensure their scores provide a defensible reference standard.

- Human–machine agreement. ReAL-T’s automated scores were compared with the experts’ composite scores for the same performances, focusing on association and agreement.

Other emphasis areas in Williamson et al.’s (2012) framework, such as generalisability, fairness, and consequences of use, were acknowledged as important but lie beyond the scope of this MVP validation and are reserved for future research.

2.5. Analytic Approach

Analyses were conducted at the level of recall performances, treating each of the 96 recall videos as a separate item (N = 96). The focus was on (a) inter-rater reliability among the three expert choreographers and (b) agreement between the choreographers and the ReAL-T.

2.5.1. Agreement Among Expert Choreographers Scores

To evaluate inter-rater reliability among the three choreographers, Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) were computed on the 1–5 scores for each performance. Inter-rater reliability was estimated using a two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement, reported as ICC(2, 1) for single measures and ICC(2, k) for average measures, in line with established guidelines for reliability studies (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979; Koo & Li, 2016). ICCs were calculated separately for the body line and form scores and the precision scores. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) was also calculated for each scoring category as a non-parametric index of agreement in the rank ordering of performances across the three choreographers.

2.5.2. Agreement Between Expert Consensus and ReAL-T Scores

To examine human–machine agreement, a combined score was created for each rating source by computing the unweighted mean of the body line and form score and the precision score, resulting in a single overall performance score on the common 1–5 scale. This combined score was computed for each of the three choreographers and for the ReAL-T across all 96 recall videos. To facilitate comparability of score levels, ReAL-T combined scores were linearly rescaled post hoc to align with the mean and standard deviation of expert ratings while preserving the original rank ordering of performances used in agreement analyses.

Agreement among the three choreographers and the ReAL-T on the combined score was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients estimated with a two-way mixed-effects model, reported as ICC(3, 1) for single measures and ICC(3, k) for average measures. Both absolute agreement and consistency coefficients were reported to capture complementary aspects of human–machine agreement (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979; Koo & Li, 2016). Although the scores were recorded on a 1–5 rubric, they were treated as approximately interval for ICC estimation, consistent with common practice in educational measurement (Norman, 2010); a complementary ordinal agreement analysis using quadratic-weighted Cohen’s κ is reported in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1 and S2; Cohen, 1968). Kendall’s W was also calculated on the combined scores to evaluate agreement in the rank ordering of performances when the ReAL-T was included alongside the human experts.

3. Results

3.1. Agreement Among Expert Choreographers

The ICC and Kendall’s W values are illustrated in Table 1. For body line and form, the ICC for absolute agreement among the three choreographers was 0.85 for a single rater, 95% CI [0.79, 0.89], and 0.94 for the average of three raters, 95% CI [0.92, 0.96]. Single-measure ICCs for consistency were 0.85, 95% CI [0.79, 0.89], and average-measure ICC = 0.94, 95% CI [0.92, 0.96]. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance also showed strong concordance in rank ordering for body line and form, W = 0.87, p < 0.01.

Table 1.

Kendall’s W test of concordance for the two categories from the three choreographers.

For precision, the ICC for absolute agreement was 0.89 for a single rater, 95% CI [0.85, 0.93], and 0.96 for the average of three raters. Single-measure ICCs for consistency were 0.89, 95% CI [0.86, 0.93], and average-measure at 0.96, 95% CI [0.95, 0.98]. Kendall’s W for precision indicated strong concordance, W = 0.91, p < 0.01.

Overall, the ICC and Kendall’s W values indicated a strong agreement among the three expert choreographers for both body line and form, and precision scores, supporting the use of their ratings as a reliable human reference standard.

Within the Kendall’s W analysis, the mean rank table for the three choreographers, presented in Table 2, further supports the conclusion of strong agreement. For body line and form, the mean ranks were 1.97 (Choreographer 1), 1.96 (Choreographer 2), and 2.07 (Choreographer 3), indicating that none of the raters were consistently much more lenient or severe than the others. A similar pattern emerged for precision, where mean ranks were 1.81, 2.07, and 2.11, respectively. These values are closely clustered around 2 across both categories, suggesting only minimal systematic differences in leniency and severity among the choreographers and reinforcing the interpretation that their ratings reflect a shared underlying judgement of performance quality.

Table 2.

Mean ranks for body line and form and precision across the three choreographers.

3.2. Agreement Between Expert Choreographers and ReAL-T

Illustrated in Table 3 are the combined scores (aggregating body line and form and precision on the 1–5 scale). Absolute agreement ICC among the four raters was 0.84 for a single measure, 95% CI [0.67, 0.91], and 0.95 for the average of four raters, 95% CI [0.89, 0.97]. Single-measure ICC for consistency was 0.91, 95% CI [0.88, 0.93], and an average-measure ICC of 0.98, 95% CI [0.97, 0.98].

Table 3.

Kendall’s W test of concordance between 4 raters (3 choreographers and ReAL-T).

Kendall’s coefficient of concordance for the combined score across the three choreographers and the ReAL-T was W = 0.89, p < 0.01, indicating strong concordance in the rank ordering of performances when the automated feedback engine is considered alongside human raters.

In Table 4, Choreographer 1 had the lowest mean rank (1.76), indicating a tendency to give the strictest ratings, followed by Choreographer 2 (2.17) and Choreographer 3 (2.39). The ReAL-T had the highest mean rank (3.10), suggesting that, while it generally preserved the same ordering of performances as the experts, it tended to assign comparatively higher scores. This pattern is consistent with the view that the automated system is slightly more generous than the human raters, yet still aligned with their overall judgement structure.

Table 4.

Mean ranks of overall scores for the three choreographers and ReAL-T.

Overall, these results show that the ReAL-T MVP achieves a level of agreement with expert choreographers that is only slightly lower than expert–expert agreement, providing a strong empirical basis for using its combined score as automated feedback within the intended beginner dance context.

4. Discussion

This study examined the validity of automated feedback generated by the minimum viable product of the ReAL-T, an AI-based scoring engine embedded in a screen-based interactive learning environment for beginner dance learners. Guided by Williamson et al.’s (2012) framework for automated scoring, the validation focused on the empirical association between automated scores and human scores, addressing two questions: the degree of agreement among expert choreographers and the degree of agreement between expert choreographers and ReAL-T.

4.1. Expert and Automated Scores as Validity Evidence

The first research question asked how strongly the three expert choreographers agreed when rating beginner performances on body line and form and precision. The ICCs for absolute agreement and consistency (0.85–0.89 for single raters; 0.94–0.96 for the average of three raters), together with high Kendall’s W coefficients (0.87–0.91), indicate good to excellent reliability (Koo & Li, 2016). The results show that, given a clearly specified rubric and a shared understanding of beginner expectations, expert choreographers can provide highly consistent ratings even in a domain that is often considered subjective. Methodologically, this aligns with long-standing guidance on ICC use for rater reliability studies, which emphasises matching the ICC model to the design and then interpreting coefficients in light of the intended use of scores (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979).

This level of expert agreement compares favourably with other performance-based assessments. Reviews of AI-related motor-skill assessment, for example, note that human raters of children’s basic motor skills frequently achieve only moderate agreement, with variability introduced by differences in training, experience, and interpretation of movement criteria (Lander et al., 2017; Figueroa-Quiñones et al., 2025). Similarly, recent surveys of pose-estimation systems for movement feedback report that human–human reliability can be a limiting factor when such systems are evaluated (Tharatipyakul et al., 2024). Against this background, the present ICC and W values suggest that the choreographers’ scores in this study provide a comparatively strong and stable human reference standard for validating ReAL-T.

The second research question concerned the extent to which the ReAL-T’s automated scores align with expert judgment. When the ReAL-T was added as a fourth rater on the combined score, ICCs for absolute agreement and consistency remained high (0.84 and 0.91 for single measures; 0.95 and 0.98 for average measures), and Kendall’s W for the four raters was 0.89. These magnitudes are similar to those reported in established automated essay scoring systems, where human–machine agreement is typically indexed by weighted kappa or correlation, often approaching human–human agreement when models are trained and evaluated carefully (Ramineni & Williamson, 2013). Syntheses of automated writing evaluation likewise highlight human–machine agreement as a central psychometric criterion and note that coefficients in the 0.80–0.90 range are generally considered acceptable for formative or mixed human–machine use (Shi & Aryadoust, 2023). From this standpoint, the present expert–ReAL-T agreement is in line with what is regarded as adequate in other education contexts, albeit in a different domain.

In the emerging literature on AI-driven movement and posture assessment, similarly high levels of agreement have been reported between AI systems and expert raters when algorithms are carefully tuned to the evaluation task. For example, an AI model evaluating ergonomic postures achieved near-perfect agreement with calibrated human evaluators on categorical posture scores (Khanagar et al., 2025). Further reviews of pose-estimation-based feedback systems observe that many prototypes are evaluated on small datasets, with limited reporting of reliability and validity metrics (Roggio et al., 2024). The present study contributes to this space by offering explicit, rater-level agreement statistics for an AI-based dance tool using a shared scale and rubric with experts, and by positioning those statistics within an established automated scoring framework.

Overall, the expert–expert and expert–ReAL-T coefficients support a validity argument in which ReAL-T’s combined score is interpreted as a reasonable approximation of expert assessment of beginner performance quality. The modest reduction in reliability when the automated rater is included is consistent with Williamson et al.’s (2012) expectation that automated scoring will typically show some degradation relative to human-only reliability, but that this can be acceptable if agreement remains high and if the construct measured by the algorithm is well aligned with the human rubric. At the same time, the fact that ReAL-T is grounded in pose-estimation and kinematic similarity implies that its strengths lie in temporal and spatial accuracy, whereas choreographers also incorporate more holistic qualities such as expressiveness and musical interpretation, an asymmetry that underpins the complementary role of automated and human feedback rather than a simple substitution of one for the other.

4.2. Implications for Automated Feedback in Interactive Learning Environments

The validation evidence for the ReAL-T MVP has several implications for the design and use of automated feedback in ILEs, particularly in complex, performance-based domains such as dance. At a broad level, the findings reinforce that automated systems can approximate expert judgement to a degree that is pedagogically useful, aligning with wider literature showing that automatic feedback often supports improved performance in online learning contexts (Cavalcanti et al., 2021).

First, the observed agreement patterns between the ReAL-T scores and expert choreographers’ ratings speak directly to the role of automated feedback as a credible surrogate for human evaluation. Research on ILEs suggests that formative feedback is most effective when it is timely, specific, and perceived as trustworthy by learners Goldin et al. (2017). The ability of ReAL-T to generate scores on the same scale and using the same criteria as human experts (i.e., body line and form, and precision) can help preserve this sense of credibility. When learners observe that automated evaluations align with how experts judge quality, they are more likely to treat the feedback as a legitimate input for self-regulation rather than as an arbitrary numerical score.

Second, the ReAL-T adds to emerging work on AI-supported dance learning systems that integrate real-time performance evaluation and visual feedback. Studies in AI-assisted dance training and visual feedback systems have shown that such tools can enhance performance, motivation, and self-efficacy when feedback is closely tied to learners’ motor execution and task goals (Xu et al., 2025). Similarly, reviews of AI-based feedback in dance education highlight the importance of aligning computational measures with pedagogically meaningful constructs, rather than using opaque metrics that are difficult for teachers and students to interpret (Miko et al., 2025). The present validation work supports this direction by showing that a computational representation of dance performance, when carefully designed, can be mapped onto rubric-based criteria that experts already use in practice.

Third, the ReAL-T contributes to the ongoing efforts to conceptualise dance as part of the broader family of interactive learning systems, where motion capture, pose estimation, and multimodal interfaces enable embodied forms of learning. Prior analyses of dance interactive learning systems emphasise that feedback design is central: how movement is visualised, how discrepancies are represented, and how learners are prompted to refine their performance across iterations (Raheb et al., 2019). By providing both quantitative scores and visual overlays that highlight divergence from the expert performance, ReAL-T exemplifies a feedback design that connects algorithmic evaluation with embodied experience. This fusion of numeric and visual cues is particularly important in domains where the quality of movement is inherently spatial, temporal, and expressive.

From the perspective of AI-based learning tools more generally, the validation of ReAL-T’s scoring function highlights the need to treat measurement quality as a core design parameter, not an afterthought. Systematic reviews of AI-based tools in higher education have pointed out that many systems report learning gains without offering rigorous evidence that the underlying automated assessments are valid and reliable (Luo et al., 2025). This multi-source evaluation approach, comparing automated scores against multiple expert raters, and examining both agreement and association, aligns with recent calls for stronger validity arguments around AI-mediated assessment and feedback.

At the same time, the findings highlight that validity is not merely a technical issue but also a social one. Trust has emerged as a critical factor in learners’ willingness to adopt AI-powered educational technologies, particularly when systems provide feedback (Nazaretsky et al., 2025). Demonstrating that ReAL-T’s scores correspond closely to expert judgements is therefore a foundational step in building such trust. However, work on fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics (FATE) in AI for higher education cautions that alignment with expert judgement is only one component of responsible design (Memarian & Doleck, 2023). Transparent communication about the capabilities and limitations of the system, how scores are generated, and appropriate use cases (i.e., formative practice rather than assessment) is equally important.

In practical terms, the validation results suggest several concrete design and implementation considerations for ILEs that incorporate ReAL-T or similar tools:

- Positioning within the feedback ecosystem. Automated scores should be framed as augmenting rather than replacing teacher feedback. In dance education, instructors can use ReAL-T outputs to triage where attention is needed, to illustrate specific technical issues using overlays, and to support reflective dialogue with learners rather than to delegate judgment entirely to the system.

- Scaffolding learner interpretation. Even when automated scores are valid, learners may misinterpret them. Interface design should therefore guide learners to connect the score with observable aspects of their performance (i.e., segment-by-segment breakdowns or linked video segments), consistent with principles for effective formative feedback in interactive learning environments (Goldin et al., 2017).

- Context-sensitive deployment. Evidence from AI-assisted dance and other arts education tools suggests that the impact on motivation and learning depends on how feedback is embedded in the broader pedagogy. For example, whether it is used to encourage experimentation, reflection, and iterative refinement rather than to enforce error-free reproduction (Nazaretsky et al., 2025). The ReAL-T is best conceptualised as a resource for iterative practice and self-assessment, particularly for adult beginners who may benefit from additional, private opportunities to rehearse and refine movements between classes.

- Ongoing monitoring and re-validation. Finally, validations such as the present study should be treated as a continuous quality assurance process rather than a one-time certification. As the tool is deployed with different learner populations, choreography styles, and instructional contexts, further evidence will be needed to monitor whether its scoring remains well-calibrated and equitable, echoing broader recommendations for responsible AI use in higher education (Memarian & Doleck, 2023).

Overall, the ReAL-T MVP illustrates how automated feedback engines can be integrated into interactive learning environments in a way that is both pedagogically meaningful and empirically grounded. By explicitly linking algorithmic scores to expert judgement, and by embedding them in a rich, visual feedback interface, the tool moves beyond generic performance metrics towards domain-sensitive, trustworthy support for dance learning.

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Work

A key strength of this study is the high-density expert rating dataset: 96 recall performances rated independently by three experienced choreographers, yielding 288 expert scores for human–machine comparison. The performances were produced in a real instructional context with adult beginner dancers, ensuring ecological relevance for the intended use of ReAL-T.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The number of learners was modest, and all performances came from adult beginners in a particular stylistic context, limiting generalisability. The MVP algorithm focuses primarily on kinematic and temporal features; expressive and stylistic aspects are less explicitly modelled and may contribute to some divergences from expert judgement. Finally, the validation addressed only one emphasis area of the Williamson et al. (2012) framework: association with human scores. Other areas, such as generalisability across tasks, fairness across subgroups, and consequences of use, remain to be explored.

Future work can extend this MVP validation by including larger and more diverse samples, additional expert raters, and choreographies in different styles and difficulty levels. Methodologically, more detailed analyses of bias and limits of agreement such as Bland–Altman plots could further characterise the relationship between expert and automated scores.

Substantively, subsequent studies can investigate how learners and teachers interpret and act on ReAL-T’s feedback within the ILE, and how automated feedback can be orchestrated with human feedback to optimise learning and motivation, building on emerging research in AI-assisted dance education and automated feedback systems (Xu et al., 2025).

5. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence that the MVP of the ReAL-T generates automated scores that are broadly aligned with expert choreographers’ ratings of beginner dance performances. By demonstrating both substantial convergence and interpretable divergences between expert and algorithmic scores, the study establishes a defensible basis for using ReAL-T’s outputs as automated feedback in an AI-driven ILE. More broadly, it offers an example of how designers of emerging ILEs can systematically validate automated feedback components against expert judgement, thereby strengthening the reliability, transparency, and educational value of automated feedback in performance-oriented domains.

6. Patents

A technology disclosure related to the work reported in this manuscript has been filed with the author’s institution (Technology Disclosure ID: TD 2025-364). The disclosure covers the Real-time Augmented Feedback in Learning Tool (ReAL-T), a screen-based feedback system that integrates pose estimation and motion analysis to support learning and assessment in beginner dance education. No patents have been granted at the time of submission.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci16020211/s1, Table S1: Quadratic-weighted Cohen’s κ for pairwise agreement among expert choreographers (body line and form). Table S2: Quadratic-weighted Cohen’s κ for pairwise agreement among expert choreographers (precision).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.J. and S.M.; Methodology, M.R.J. and S.M.; Software, M.R.J.; Validation, M.R.J. and S.M.; Formal analysis, M.R.J. and S.M.; Investigation, M.R.J. and S.M.; Resources, M.R.J. and S.M.; Data curation, M.R.J. and S.M.; Writing—original draft, M.R.J.; Writing—review & editing, S.M.; Visualization, M.R.J. and S.M.; Supervision, S.M.; Project administration, M.R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institutional Review Board of Nanyang Technological University (protocol code IRB 2022-843 and date of approval 19 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study, detailing the nature of the study, the procedures involved, the voluntary nature of their involvement, any potential risks and benefits, the confidentiality measures in place to safeguard their personal information, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their heartfelt gratitude to the individuals who generously contributed their time and effort to the experiments in this research. Special thanks go to the three expert choreographers. Their invaluable participation and dedication were integral to this study’s practical validation and success.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bates, T., Cobo, C., Mariño, O., & Wheeler, S. (2020). Can artificial intelligence transform higher education? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, A. P., Barbosa, A., Carvalho, R., Freitas, F., Tsai, Y.-S., Gašević, D., & Mello, R. F. (2021). Automatic feedback in online learning environments: A systematic literature review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70(4), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Quiñones, J., Ipanaque-Neyra, J., Gómez Hurtado, H., Bazo-Alvarez, O., & Bazo-Alvarez, J. C. (2025). Development, validation and use of artificial-intelligence-related technologies to assess basic motor skills in children: A scoping review. F1000Research, 12, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, E., & Woolley, A. W. (2020). Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, I., Narciss, S., Foltz, P., & Bauer, M. (2017). New directions in formative feedback in interactive learning environments. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 27, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, M. R. (2024). A novel screen-based technology for dance learning and assessment in adult beginner dancers [Ph.D. thesis, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University]. [Google Scholar]

- Khanagar, S. B., Alshehri, A., Albalawi, F., Kalagi, S., Alghilan, M. A., Awawdeh, M., & Iyer, K. (2025). Development and performance of an artificial intelligence-based deep learning model designed for evaluating dental ergonomics. Healthcare, 13(18), 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, N., Morgan, P. J., Salmon, J., Logan, S. W., & Barnett, L. M. (2017). The reliability and validity of an authentic motor skill assessment tool for early adolescent girls in an Australian school setting. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(6), 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. (2025). AI-based dance evaluation systems and personalized instruction: Possibilities and boundaries of dance education in the intelligent era. Journal of Education, Humanities, and Social Research, 2(4), 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J., Zheng, C., Yin, J., & Teo, H. H. (2025). Design and assessment of AI-based learning tools in higher education: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 22(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, B., & Doleck, T. (2023). Fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics (FATE) in artificial intelligence (AI) and higher education: A systematic review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miko, H., Frizen, R., & Steinberg, C. (2025). Using AI-based feedback in dance education: A literature review. Research in Dance Education. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaretsky, T., Mejia-Domenzain, P., Swamy, V., Frej, J., & Käser, T. (2025). The critical role of trust in adopting AI-powered educational technology for learning: An instrument for measuring student perceptions. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsloo, P. (2020). Of ‘black boxes’ and algorithmic decision-making in (higher) education—A commentary. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 2053951720933994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheb, K. E., Stergiou, M., Katifori, A., & Ioannidis, Y. (2019). Dance interactive learning systems: A study on interaction workflow and teaching approaches. ACM Computing Surveys, 52(3), 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramineni, C., & Williamson, D. M. (2013). Automated essay scoring: Psychometric guidelines and practices. Assessing Writing, 18(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggio, F., Trovato, B., Sortino, M., & Musumeci, G. (2024). A comprehensive analysis of the machine learning pose estimation models used in human movement and posture analyses: A narrative review. Heliyon, 10(21), e39977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H., & Aryadoust, V. (2023). A systematic review of automated writing evaluation systems. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), 771–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strielkowski, W., Grebennikova, V., Lisovskiy, A., Rakhimova, G., & Vasileva, T. (2025). AI-driven adaptive learning for sustainable educational transformation. Sustainable Development, 33(2), 1921–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharatipyakul, A., Srikaewsiew, T., & Pongnumkul, S. (2024). Deep learning-based human body pose estimation in providing feedback for physical movement: A review. Heliyon, 10(17), e36589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangoo, D. P., & Reddy, S. R. N. (2021). Artificial intelligence applications and techniques in interactive and adaptive smart learning environments. In Artificial intelligence and speech technology (pp. 427–437). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D. M., Xi, X., & Breyer, F. J. (2012). A framework for evaluation and use of automated scoring. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 31(1), 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-J., Wu, J., Zhu, J.-D., & Chen, L. (2025). Effects of AI-assisted dance skills teaching, evaluation and visual feedback on dance students’ learning performance, motivation and self-efficacy. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 195, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.