Abstract

This study examines how Artificial Intelligence (AI) can enhance Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) through embodied, multimodal instruction in secondary Physical Education (PE). Drawing on Fernández Fontecha’s Content and Language Processing Sequence (CLPS) model, four AI-supported CLIL modules were designed and partially implemented in a Spanish secondary school. The exploratory, design-based study involved 25 students (aged 13–14) enrolled in second-year secondary education (2° ESO). Data were collected through a student perception survey and structured teacher observations to examine learners’ perceived content understanding, language use, engagement, and embodied participation in AI-supported CLIL tasks. Results indicate high levels of student engagement and positive perceptions of learning, particularly regarding vocabulary use, task comprehension, and the integration of physical movement with language use. Students reported that AI tools such as NaturalReader and Gliglish supported pronunciation practice, comprehension, and interactive language use when embedded within guided CLIL tasks. The findings highlight the pedagogical potential of AI as a mediating scaffold in embodied CLIL contexts, while underscoring the importance of teacher guidance and task design. The study contributes to emerging research on AI-enhanced CLIL by offering empirically grounded insights into the affordances and limitations of integrating AI in Physical Education.

1. Introduction

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) has rapidly evolved into a leading methodology in European multilingual education, blending subject content with language learning to foster both linguistic and disciplinary proficiency (Coyle et al., 2010a; Marsh, 2002). Empirical evidence indicates robust gains in students’ language competence, motivation, and learner autonomy, encouraging widespread adoption across school curricula (Dalton-Puffer, 2008; Hartiala, 2000). However, practical challenges in balancing content and language goals persist, underscoring the complex demands of CLIL lesson design (Dinham, 2024).

The pedagogical landscape has shifted further with advances in Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and, more recently, Artificial Intelligence (AI). ICTs are well-established catalysts of learner motivation and differentiated instruction in content-based classrooms; their integration supports multimodal, collaborative, and authentic language use (Montes Borrego, 2020). AI marks a new pedagogical phase, introducing adaptive feedback, personalised pathways, and forms of scaffolding previously unattainable with conventional digital tools (Holmes et al., 2019; Luckin et al., 2016; Tai et al., 2025). Recent systematic reviews demonstrate that digital-intelligent technologies—including AI-driven applications, virtual and augmented reality, and wearable analytics—facilitate real-time instructional feedback and richer embodied learning experiences, particularly in Physical Education (PE) (Zhong et al., 2025; Cui et al., 2025).

Despite these advances, the intersection of CLIL, AI, and embodied learning—especially within PE—remains severely underexplored (Zhong et al., 2025; Dinham, 2024). This gap is both theoretical and practical: while emerging research underscores AI’s potential to enhance adaptive and embodied instruction, it also exposes unresolved issues related to equity, privacy, and teacher training (Zhong et al., 2025). There is thus an urgent need for empirically grounded frameworks that integrate AI-based personalisation and multimodal engagement into CLIL environments in a pedagogically coherent manner.

To address these critical gaps, the present study explores the following research questions:

- How can AI-enhanced, ICT-integrated CLIL modules—specifically following the Content and Language Processing Sequence (CLPS)—improve learning outcomes in secondary school PE?

- What are the implications of combining digital personalisation, embodied activity, and real-world communication for both language and physical skill development?

- What challenges and opportunities emerge for teachers, institutions, and learners as AI extends the CLIL model in practice?

To operationalise these questions, four modular CLPS–CLIL lessons were designed, embedding diverse AI tools such as NaturalReader, Gliglish, and adaptive WebQuests to scaffold language and procedural knowledge through both classroom and playground activities. This study, situated within Spanish Secondary Education, offers an empirical examination of how AI-infused CLIL instruction can bridge theory and practice in embodied learning contexts.

2. Theoretical Background and Framework

2.1. CLIL and the 4Cs: Evolving Foundations

CLIL originated from Canadian immersion frameworks and has steadily gained global and European prominence as a flexible, dual-focused pedagogical model that promotes simultaneous content and language learning (Coyle et al., 2010a; Marsh, 2002; Dinham, 2024). Extensive empirical evidence demonstrates that when well implemented, CLIL surpasses traditional EFL approaches by fostering integrated linguistic and disciplinary development, stronger communicative competencies, and deeper intercultural awareness (Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2009; Marsh, 2002; Tai et al., 2025).

The 4Cs framework—Content, Communication, Cognition, and Culture—remains foundational to CLIL pedagogy, guiding lesson planning and curricular sequencing to balance linguistic and disciplinary aims (Coyle et al., 2010a). Content concerns conceptual and procedural knowledge; Communication emphasises language as a tool for learning, encompassing language of learning (key terminology), for learning (functional discourse), and through learning (emergent interaction). Cognition develops learners’ Higher- and Lower-Order Thinking Skills (Bloom et al., 1956), and Culture fosters intercultural awareness and reflective engagement with diverse perspectives.

Despite its widespread application, the literature identifies persistent challenges and inequities in CLIL implementation (Tai et al., 2025). Linguistic demands in CLIL contexts may lead to the simplification of subject content, potentially reducing cognitive depth if tasks are not carefully designed (Coyle et al., 2010a; Dalton-Puffer, 2007; Llinares et al., 2012); selective CLIL programmes can marginalise less proficient learners, threatening inclusivity; and many teachers report limited preparation for addressing CLIL’s dual focus (Pérez-Cañado, 2012; Ball & Lindsay, 2010; Nguyen et al., 2023). Recent scholarship emphasises that achieving both inclusion and cognitive challenge requires participatory, authentic, and multimodal environments where content and language reinforce one another dynamically (Dinham, 2024; Akay et al., 2025). These insights are now driving CLIL innovation beyond traditional academic disciplines and into more embodied domains such as the arts and PE (Hu et al., 2025).

2.2. ICT and Artificial Intelligence: Transforming CLIL

ICT integration in CLIL has long been recognised for expanding learning modalities, differentiating instruction, and bridging school-based learning with real-world communication (Montes Borrego, 2020; Stoller et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2025). The use of interactive digital materials, online collaboration, and language-data analytics enhances motivation, vocabulary acquisition, and communicative competence (Coyle et al., 2010b). PE, in particular, benefits from physical engagement that supports kinaesthetic and experiential forms of language learning (Coral et al., 2017).

The emergence of AI and other digital-intelligent technologies (DITs) represents a paradigm shift in this trajectory. Systematic reviews identify three transformative domains: (1) adaptive feedback and formative assessment using machine learning and computer vision; (2) personalised instruction through user modelling and physiological or behavioural data tracking; and (3) immersive, gamified learning environments employing VR/AR systems, intelligent wearables, and multimodal feedback (Zhong et al., 2025; Cui et al., 2025). Collectively, these affordances enable dynamic alignment among learner needs, pedagogical goals, and embodied experience (Holmes et al., 2019; Luckin et al., 2016).

Nonetheless, significant challenges persist regarding accuracy, accessibility, privacy, and the pedagogical coherence of integrating DIT into embodied learning contexts (Zhong et al., 2025). Within PE specifically, AI-enhanced tools are only beginning to address the synergy between language, content, and physical performance outcomes. This gap underscores the need for models that translate technological innovation into sustainable pedagogical practice.

2.3. Integrating AI, CLIL, and Embodied Learning: Framework for This Study

This research adopts Fernández Fontecha’s Content and Language Processing Sequence (CLPS) as a modular, learner-centred framework for structured digital integration (Fontecha, 2010, 2012). CLPS offers a systematic blueprint for sequencing content and language objectives while incorporating ICT and AI tools that promote interactivity and inclusion. Grounded in recent findings that highlight the importance of personalisation and multimodality for deep learning (Hu et al., 2025), the present study extends CLPS to examine AI’s role in supporting embodied CLIL instruction in PE.

By developing and testing four AI-enhanced CLPS modules in Spanish secondary education, this study contributes to both theory and practice by:

- Leveraging cutting-edge AI affordances for real-time feedback, adaptive learning, and engagement.

- Positioning Physical Education as a domain for embodied and multimodal CLIL innovation;

- Responding to ongoing equity, privacy, and teacher-training challenges highlighted in recent scholarship (Zhong et al., 2025; Dinham, 2024).

Together, these principles establish a conceptual and empirical foundation for investigating how AI-driven CLIL design can advance inclusive, interactive, and embodied learning across educational settings.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed an action research case study to investigate the pedagogical potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools integrated within a CLIL framework following the Content and Language Processing Sequence (CLPS) model (Fontecha, 2010, 2012). The design sought to measure both quantitative and qualitative learning outcomes related to linguistic performance, motivation, and engagement, as well as students’ perceived experiences with AI-supported embodied learning.

The intervention comprised four CLPS-based modules delivered over four weeks in a secondary-school PE setting. Each module integrated physical activity with English-language use through AI-enhanced CLIL tasks. Quantitative data were collected via pre- and post-tests measuring vocabulary and content knowledge, while qualitative data were drawn from reflective journals and semi-structured interviews to explore learner perceptions and engagement. Although several data collection instruments were designed as part of the teaching proposal (including preparatory tasks and reflective activities), the empirical analysis reported in this study focuses primarily on students’ perception survey responses and structured teacher observations. These instruments were selected to capture learners’ perceived linguistic development, content understanding, engagement, and embodied participation within the AI-supported CLIL context. While several instruments were employed during the implementation phase (diagnostic activities, reflective prompts, and informal interviews), only those data sources directly aligned with the research questions and consistently applied across participants were included in the reported analysis. The survey items were formulated using consistent wording and response scales to ensure comparability across dimensions related to language use, content understanding, engagement, and perceptions of AI support. Diagnostic tasks and reflective activities were used formatively to support instructional design and scaffolding rather than for summative evaluation. Consequently, the empirical analysis focuses on post-implementation student perception data and structured teacher observations, allowing an exploratory examination of learners’ perceived content understanding, language use, and engagement within the AI-supported CLIL intervention.

3.2. Procedure

The teaching proposal Improving Physical Performance through a Warm-Up Routine applies Fernández Fontecha’s CLPS approach (Fontecha, 2010, p. 49; 2012, p. 324) to create four modules focused on warm-up routines and physical health: the Introductory, Core-Knowledge, Case, and Awareness Modules. These modules guide students in progressively developing their understanding of the topic and subtopic.

Targeting 25 s-year Spanish Secondary Education students (2º de la ESO), each 55 min lesson is structured around a CLILQuest—an ICT-based task central to the model. The proposal includes a variety of ICT resources, with a special emphasis on Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools as scaffolding for students. AI, increasingly recognised for its educational benefits, enhances oral performance, accuracy, fluency, and interaction in foreign-language learning (Kang, 2022).

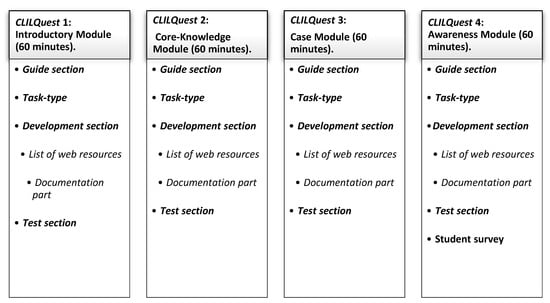

Each module is divided into four sections: the guide, the task type, the development, and the test. The development section comprises two subsections: a list of web resources with relevant links and a documentation section that provides additional scaffolding materials, such as templates and discourse markers. Given the proposal’s ICT focus, AI tools are integrated into the web resources to support students throughout the tasks. These tools have been shown to enhance personalised learning, create interactive learning environments, and boost motivation, benefiting both teachers and students (Patty, 2024, p. 647).

The AI tools adopted in this proposal are as follows:

- NaturalReader: Free AI tool that converts text formats into spoken audio, which can help students practice pronunciation and intonation.

- Gliglish: Free AI tool specifically designed to learn languages. It allows learners to speak with a virtual teacher and practice role-playing real-life situations, which can help students improve their listening and speaking skills, as well as their language accuracy.

- Wowzer: Multi-model AI tool for image generation. By introducing the desired prompts, students can generate, explore, and compare multiple images, fostering their creativity and imagination.

- QuillBot: Free AI tool that allows learners to condense articles and documents, by paragraphs or down to the key points, while maintaining the original context. This tool can help students improve grammar accuracy and reading skills.

The four lessons will be developed in class, and students will be allowed to use their personal Chromebooks throughout the four modules. All materials and resources will be uploaded to an Open-Source Learning Management System (LMS), Google Classroom, where students will log in to complete the CLILQuests. Sessions will take place both in the classroom and on the playground, where learners will put into practice the knowledge they have acquired throughout the modules. Hence, digital strategies will be combined with classroom practice so that pupils get as much input on content and language as possible. Figure 1 shows the structure adopted for the four modules or lessons.

Figure 1.

Modular structure of the teaching proposal.

3.3. Targeted Students

The present teaching proposal, Improving Physical Performance through a Warm-Up Routine, has been designed for a group of 25 students currently in their second year of Spanish Secondary Education (2º de la ESO). Eighteen of these learners are 13 years old, and twelve are 14 years old. This group receives a total of four hours of formal English instruction per week, in addition to three hours per week of Physical Education instruction, which is taught in English. Although some learners have acquired greater proficiency than others over the years, the class as a whole generally has an A2 or Pre-intermediate level of English according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). Students’ English proficiency was estimated at approximately A2 level according to institutional records and the English teacher’s continuous assessment, following the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). No additional standardised placement test was administered specifically for this study. All participants were enrolled in the same intact class group, and no additional comparison or control group was involved in the implementation.

3.4. Competencies

The current Teaching Proposal follows Coyle et al.’s (2010b, p. 53) 4Cs Framework, which emphasises content, communication, cognition, and culture. In terms of content, students will acquire knowledge of warm-up routines and physical health, deepening their understanding of warm-up strategies, their health benefits, and practical implementation. By the end of the module, students will create and apply an effective warm-up routine for Physical Education.

Communication focuses on language use, divided into language of learning, language for learning, and language through learning (Escobar Urmeneta & Sánchez Sola, 2009, p. 86). The language of learning encompasses essential vocabulary and grammar, including verbs (stretch, move), adjectives (dynamic, flexible), and structures such as the imperative (stretch your muscles, stay hydrated). Language for learning involves skills necessary for functioning in a foreign language context, such as research, teamwork, and discussion, developed through CLILQuests. Receptive (listening, reading) and productive (speaking, writing) skills are also emphasised, with scaffolding provided to support appropriate language use. Language through learning emerges organically from students’ active engagement in tasks, allowing them to communicate effectively and build on previously introduced skills (Ó Ceallaigh et al., 2017, p. 58).

Cognition addresses the skills students develop in both content and language, often expressed as can-do statements aligned with module objectives (Coyle et al., 2010b, p. 55). These will be reflected in a post-module survey where students will respond to statements like “I can apply the warm-up routine described in the text” on a 5-point Likert Scale. Students will also engage with Bloom et al.’s (1956) Lower-Order Thinking Skills (LOTS)—remembering, understanding, and applying—and Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS)—analysing, evaluating, and creating. The Introductory Module emphasises LOTS, while the Awareness Module centres on HOTS. However, each lesson is designed to progressively develop both LOTS and HOTS, fostering a balanced skill set across modules.

3.5. Modules’ Objectives

This proposal is part of the Physical Education curriculum. It has four main objectives, one per module (see Table 1): to carry out research into the concept of warm-up and how to implement it in a physical routine (Introductory Module), to identify the best warm-up strategies for different movement sequences (Core-Knowledge Module), to analyse the importance of warm-up routines in Physical Education (Case Module) and to design an efficient warm-up routine for Physical Education and reflect upon its effects on physical performance (Awareness Module).

Table 1.

Modules and objectives of the teaching proposal.

3.6. Materials

The materials and resources in this teaching proposal are tailored for second-year Secondary Education students at Colegio Hermes but can be easily adapted for other ages or English proficiency levels. These resources support both English and Physical Education learning, requiring students to engage in metacognitive, cognitive, and social skills to complete each CLILQuest. The four modules include tools like online dictionaries, glossaries, note-taking templates, discourse markers, relevant digital links, and AI resources to facilitate meaningful learning. Students work in groups on the CLILQuests to encourage communication and opinion exchange, with some individual work in preparation, note-taking, and self-reflection stages. The modules are structured to support the development of all language skills, with the first two focusing on receptive skills and the latter two on productive skills.

For the Awareness Module, specific materials were created to align with students’ prior knowledge of warm-up routines and physical health. Vocabulary had been reviewed in a previous English lesson, and scaffolding materials minimised potential learning gaps. Students were also provided with a sample warm-up routine to clarify the task’s final product. Each module can be adapted to the specific needs of different student groups, focusing on product-based tasks that apply the content and language knowledge in practical contexts. This proposal serves as a flexible guide, offering a range of resources to enrich students’ learning. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these materials to maximise engagement and comprehension for their particular group of students.

3.7. Lesson Planning

The current teaching proposal is divided into four interconnected modules (Introductory Module, Core-Knowledge Module, Case Module, and Awareness Module), each developed through a CLILQuest, a type of WebQuest specifically designed for Content and Language Integrated Learning (Muñoz Acevedo et al., 2013, p. 14). As previously mentioned, the four lessons are largely based on an ICT component and will be delivered through a blended approach. In other words, technology and digital media will be used to aid face-to-face instruction and classroom activities (Gerbic, 2011, p. 222).

Students are the agents of their own learning process. Consequently, each CLILQuest will be required to assume different roles, work collaboratively, and discuss findings to complete a series of tasks. For these purposes, scaffolding will be provided throughout the four modules. Each CLILQuest is organised into four sections, as shown below. At the end of the fourth CLILQuest or Awareness module, students will complete a survey to self-evaluate the knowledge acquired throughout the modules and their overall satisfaction with the lessons.

- The guide section aims to introduce the students’ roles, the main goal(s), and the expected outcomes, and some pre-tasks to engage learners and raise schematic knowledge.

- The task type involves the main tasks or quests.

- The development section integrates a list of web resources and a documentation part to help accomplish the quests. This section serves as scaffolding.

- The test section is designed to evaluate learners’ knowledge of the topic and its subtopics.

- A student survey (Awareness Module) is included, designed for students’ self-evaluation (see Section 4).

Thus, the four-module programme entitled Improving Physical Performance through a Warm-Up Routine and designed for second-year Secondary Education students as described above.

4. Post-Implementation Results and Discussion

The results presented in this section are reported according to the items of the student perception survey administered after the implementation of the AI-supported CLIL modules. While the analysis follows this item-based structure, the interpretation of the findings is guided by the study’s three research questions. Specifically, the survey items collectively inform students’ perceived content and language learning within an AI-supported CLIL framework (RQ1), the role of embodied physical activity combined with digital scaffolding in supporting engagement and understanding (RQ2), and the pedagogical opportunities and challenges associated with integrating AI tools into CLIL practice in Physical Education (RQ3). After the final module was delivered, pupils were given a survey to encourage post-class reflection. This survey featured six can-do statements on a 5-point Likert scale to gauge students’ perceptions of their own learning as a result of the CLIL class (1 = I can’t do it, 2 = I need help, 3 = I’m competent, 4 = I’m good, 5 = I’m excellent):

- I can understand and analyse a short warm-up routine.

- I can apply the warm-up routine described in the text.

- I can understand the vocabulary related to physical exercise.

- I can design and write a warm-up routine.

- I can use the words learned in the lesson to write my routine.

- I can apply a warm-up routine designed and written by me.

The survey also featured two other questions on a 5-point Likert scale designed to consider students’ overall satisfaction with the lesson and the methodology employed (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much, 5 = extremely):

- How satisfied are you with the teaching methods used in this lesson?

- How much do you think this lesson will help you remember information about warm-up routines?

The items included in the post-implementation perception survey were designed to operationalise the study’s three research questions at the construct level. Items related to task comprehension, vocabulary use, and confidence in using English primarily addressed students’ perceived content and language learning (RQ1), while items focusing on engagement, participation, and language use during physical activity informed the role of embodied learning and digital scaffolding (RQ2). Items targeting students’ perceptions of AI tools and overall satisfaction contributed mainly to identifying pedagogical affordances and challenges associated with AI integration in CLIL Physical Education (RQ3). Although some overlap between constructs was expected, each item was associated with a dominant analytical focus aligned with the study’s research objectives.

The last item of the survey was an open-ended question in which students could write any comments or suggestions regarding the lesson, the teacher, or other relevant factors (Do you have any suggestions or comments about this lesson?). Although it was not mandatory to complete this part of the survey, learners were encouraged to write their answers freely to provide as much input as possible on class development and students’ concerns about CLIL.

This analysis seeks to provide a general understanding of students’ perceptions of their learning from the CLIL class, as well as pupils’ overall satisfaction with the lesson and the methodology employed. Quantitative survey data were collated and analysed in Microsoft Excel, which was also used to graphically represent the findings. There were 25 student responses. No differentiation between male and female learners was established because this factor did not affect the study. Also, all data was anonymised to ensure transparency and privacy. Findings from the perception survey were triangulated with teacher observation notes to contextualise students’ self-reported experiences and enhance interpretative reliability.

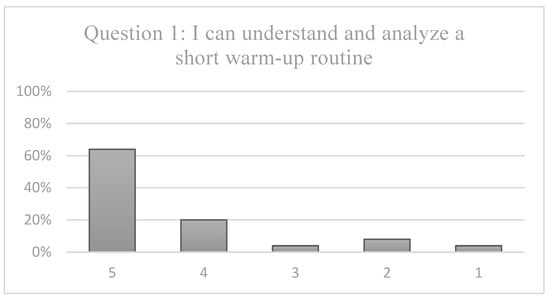

Regarding the first item of the survey (I can understand and analyse a short warm-up routine), the findings point towards a notable success of the CLIL-in-PE lesson in teaching warm-up routines. Sixty-four per cent of students selected 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = I’m excellent), indicating they had no difficulty comprehending the vocabulary and movement sequences required to complete the lesson successfully. Twenty per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = I’m good), four per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = I’m competent), eight per cent of pupils selected number 2 (2 = I need help), and four per cent of learners felt that they could not do it (1 = I can’t do it); as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Question 1.

The average score for this survey item was 4.32 (out of 5), and the SD (Standard Deviation) was 1.12. This CLIL-in-PE lesson offered students the opportunity to practice vocabulary and sentence structure within a real and less formal environment than that of a regular English lesson, which also seemed to increase their willingness to take risks in terms of speaking and writing and engage in active physical movement (Lamb & King, 2020, p. 516). Hence, results suggest that the vast majority of students understood the vocabulary of the lesson, which, according to Ramos and Ruíz Omeñaca (2011, pp. 166, 167) allowed them to analyse the given warm-up routine to put it into practice later, activating their background knowledge and practising Lower- and Higher-Order Thinking Skills (LOTS and HOTS).

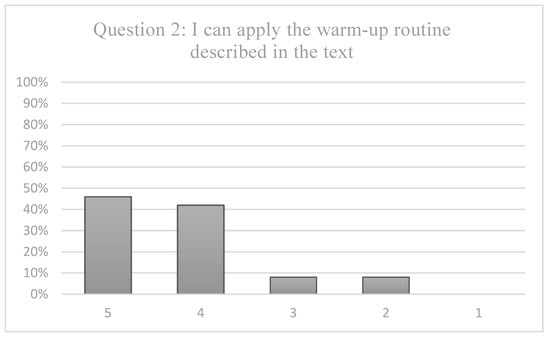

Regarding the second survey item (I can apply the warm-up routine described in the text), students scored an average of 4.2 out of 5 points, with an SD of 0.9. Hence, this item also indicates positive results. Overall, students showed no difficulty implementing the warm-up routine described in the sheet handed out (also posted on Google Classroom). Pictures were included to ensure that even learners at lower levels could understand the different steps. Forty-six percent of students chose number 5 (5 = I’m excellent), forty-two percent of students selected number 4 (4 = I’m good), eight percent of learners picked number 3 (3 = I’m competent), another eight percent of pupils chose number 2 (2 = I need help), and no learners felt that they could not do it (1 = I can’t do it); as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Question 2.

We believe the use of visual aids helped pupils understand the content and kept their attention focused on the process, as Salvador-García et al. (2020) suggest (p. 1135). Similarly, combining text and images may enhance students’ imagination, which could lead to the development of skills such as critical thinking (Macwan, 2015, p. 93), a key element of the CLPS approach. Students’ reaction to the task was positive, and the vast majority of them seemed to have a favourable attitude toward it, even though, for some learners, Physical Education can be quite challenging due to a lack of natural sporting abilities (Asbury, 2000, p. 2). Nonetheless, no significant difficulties were encountered by any pupils when applying the warm-up routine described in the text. We assume this is because combining tasks that integrate language and motor skills has been shown to reinforce understanding and language acquisition (Coral et al., 2017, p. 47).

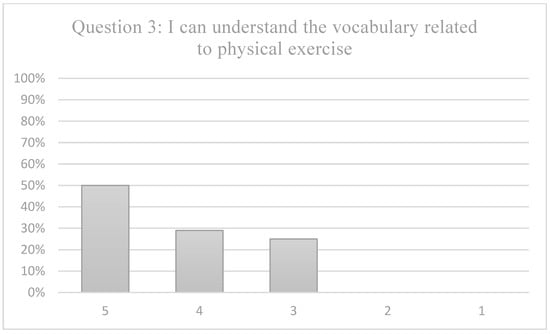

The third item of the survey concerns the specific language used in the lesson (I can understand the vocabulary related to physical exercise). Although findings also indicate positive results, students’ responses are more varied. Fifty per cent of students chose number 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = I’m excellent), twenty-nine per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = I’m good), and twenty-five per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = I’m competent). No students felt like they needed help or were incapable of accomplishing the task. Thus, the learners’ average score for this survey item was 4.24 (out of 5), and the SD was 0.81; as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Question 3.

The target language was introduced in a previous lesson, as presenting the vocabulary beforehand is crucial for facilitating understanding and providing pupils with meaningful context (Fernández-Costales, 2023, p. 130), which may have contributed to the positive results. In addition, we believe the scaffolding tools available throughout the module may have promoted gradual skill development in a supportive environment (Watts-Taffe & Truscott, 2000, p. 260), thereby facilitating easy comprehension of vocabulary related to physical exercise. Pre-teaching specific vocabulary also diminishes students’ anxiety and helps create a safe, non-judgemental learning environment where learners can experiment with language without fear of judgement or repercussions (Lamb & King, 2020, p. 533). Hence, we believe this CLIL-in-PE lesson was developed in an appropriate environment for pupils to widen their vocabulary related to physical exercise.

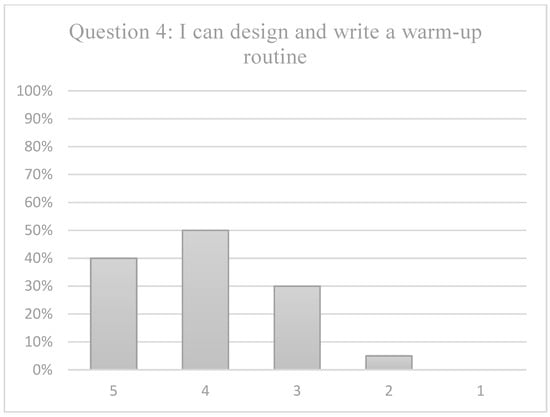

The fourth item of the survey (I can design and write a warm-up routine) is related to cognition, a key component of the 4Cs Framework proposed by Coyle (2007) and around which the current CLPS teaching proposal is structured. The previous items were mostly aimed at developing Lower-Order Thinking Skills (LOTS), especially the basic competencies of understanding and applying. The current item targets higher-order thinking Skills (HOTS), which address, in this case, the competencies of remembering and applying. Thus, this lesson focuses on language, meaning, and communication within a PE context (Heras & Lasagabaster, 2015, p. 72).

Forty per cent of students selected 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = I’m excellent). Fifty per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = I’m good), thirty per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = I’m competent), five per cent of pupils picked number 2 (2 = I need help), and no learners felt that they could not do it (1 = I can’t do it). Findings point toward positive results, and we can observe a change from the previous items. Now, the majority of learners felt they were good at completing the task, whereas in the first three items, the majority of pupils felt they were excellent. We believe this change is related to the fact that learners usually find productive skills, such as writing, more challenging than receptive skills (Fareed et al., 2016, p. 92). Overall, the results indicate that students might have gained new knowledge and abilities by reflecting upon the previously developed Lower-Order Thinking Skills (LOTS) to subsequently acquire Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS), which allowed them to design and write a warm-up routine remembering and applying the vocabulary of the lesson (Fernández-Costales, 2023, p. 130), as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Question 4.

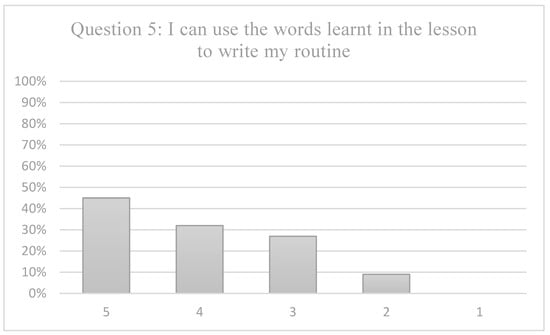

The fifth item of the survey relates to the real language students use when writing their warm-up routine (I can use the words learned in the lesson to write my routine). Here, the results also seem overall positive. Forty-five per cent of students selected number 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = I’m excellent). Thirty-two per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = I’m good), twenty-seven per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = I’m competent), nine per cent of pupils picked number 2 (2 = I need help), and no learners felt that they could not do it (1 = I can’t do it), as illustrated in Figure 6. The warm-up routines were written in groups to maximise students’ possible outcomes through collaborative work (Coral i Mateu, 2013, p. 45). The content and language teachers ensured each team included both strong and weak students in both content and language to enhance learners’ participation and confidence (Salvador-García et al., 2020, p. 1133).

Figure 6.

Question 5.

The specific language required to complete this task successfully went beyond the typical dialogue in which students would engage in a traditional English class (Ito, 2019, p. 45). The majority of learners seem to have reflected on the previously acquired Lower Order Thinking Skills (LOTS), which enabled them to remember the lesson vocabulary and subsequently use it appropriately, thereby developing Higher-Order Thinking Skills (HOTS) (Fernández-Costales, 2023, p. 130). With an average score of 4 out of 5 points and an SD of 0.98, we believe this CLIL-in-PE lesson might have helped students use language in a free and productive way, which has been shown to reduce feelings of anxiety and increase participation rates (Olson, 2021, p. 13). All learners seemed engaged in the lesson and motivated to work together. Grammatical and lexical errors were mainly limited to minor issues such as verb tense omission (e.g., “we warm up” instead of “we are warming up”) and occasional lexical substitutions (e.g., “make exercise” instead of “do exercise”), which did not impede task comprehension or communication during activities. In addition, the sample text provided might have helped draw students’ attention toward specific vocabulary, developing pupils’ writing skills (Danilov et al., 2018, p. 1977).

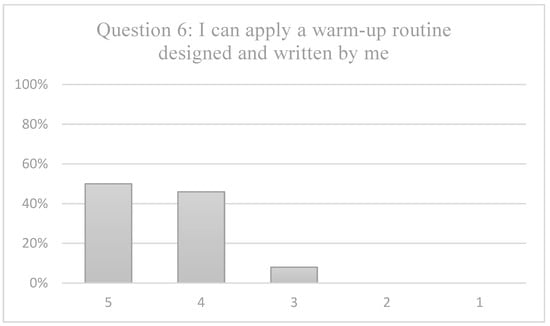

The last item in this section of the perception survey concerns the content subject and the physical movement students engaged in after designing their warm-up routines (I can apply a warm-up routine designed and written by me). Here, learners had an average score of 4.4 out of 5, with an SD of 0.63. Fifty per cent of students selected five on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = I’m excellent). Forty-six per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = I’m good), eight per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = I’m competent), and no pupils felt like they needed help (2 = I need help) or they could not do it (1 = I can’t do it), as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Question 6.

This survey item points towards positive results. Once each group had written their warm-up routines, learners put them into practice in front of their classmates so that everyone could follow their movements. Collaborative work is central to CLIL (Goris et al., 2019, p. 690), and learners were encouraged to be imaginative and to practise before showing their routine to the rest of the class, which supports learners’ development of communicative abilities and content competencies (Maggi, 2012, p. 60). Students with lower initial confidence in using English, as observed by the teacher during early sessions, were particularly eager to participate in group-based physical tasks and oral interactions when supported by AI tools and peer collaboration. As Mosston and Mueller (1974, p. 101) note, this may be because ‘the nature of the practical environment makes it very difficult for pupils to choose not to participate in the lesson; unlike a classroom that may allow a certain level of conscious non-engagement in tasks without necessarily being noticed’. Thus, it seems everyone felt confident enough to perform their warm-up routine because they had designed it according to their physical condition.

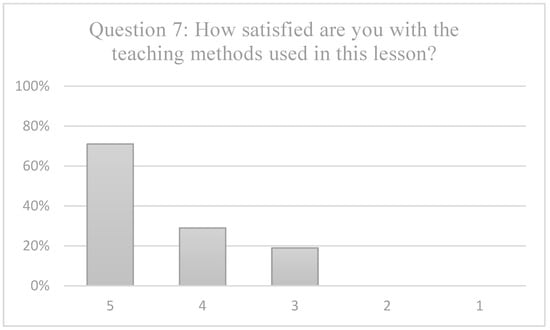

The second part of the perception survey consists of two questions designed to assess students’ overall satisfaction with the lesson and the methodology used, rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The first item (How satisfied are you with the teaching methods used in this lesson?) points toward highly positive results. Pupils had an average score of 4.08 out of 5, with an SD of 0.63. Seventy per cent of students selected number 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = Extremely). Twenty-nine per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = Very much), nineteen per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = Quite a bit), and no pupils felt like they were not satisfied at all (1 = Not at all) or just a little (2 = A little), as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Question 7.

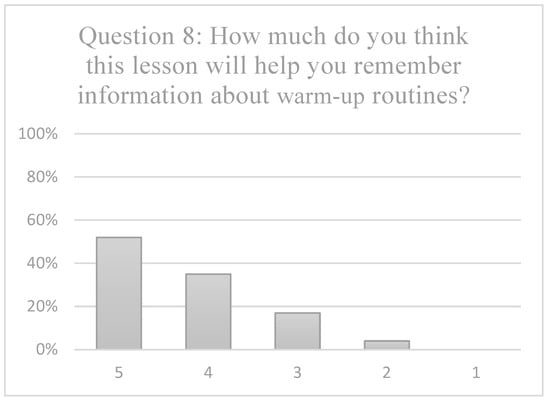

The second item also suggests positive results (How much do you think this lesson will help you remember information about warm-up routines?). Pupils had an average score of 4.24 out of 5, with an SD of 0.86. Fifty-two per cent of students selected number 5 on the 5-point Likert scale (5 = Extremely). Thirty-five per cent of students chose number 4 (4 = Very much), seventeen per cent of learners selected number 3 (3 = Quite a bit), four per cent of pupils picked number 2 (2 = A little), and no students selected number 1 (1 = Not at all), as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Question 8.

Consequently, we believe this CLIL-in-PE lesson prompted students to develop knowledge in a safe, non-judgmental learning environment, allowing them to feel free to experiment with language and movement patterns, thereby promoting language awareness, independent learning, and peer interaction (Reiko et al., 2015, p. 19). It also seems that the vast majority of learners were satisfied with the methodology employed during the class and found the information to be useful and relevant, probably because the PE framework provided a more flexible context than that of traditional English lessons, creating an authentic and situated learning environment (Sulyman et al., 2022, p. 183). Similarly, we believe this practical environment favoured tolerance for language variation and errors, encouraging what Brumfit (1984, p. 29) calls guilt-free participation, making learners feel comfortable sharing their ideas and participating actively in class.

Finally, the last section of the survey concerns an open-ended question for students to write any comments or suggestions regarding the lesson (Do you have any suggestions or comments about this lesson?). This part of the survey was not mandatory, so not every learner completed it. However, some pupils wrote highly positive comments, as seen below (Figure 10). Thus, we believe this CLIL-in-PE lesson helped create a favourable atmosphere and provided opportunities for meaningful communication where students felt safe and enjoyed the learning process, which is one of the basic principles of the CLPS approach (Fontecha, 2012, p. 324). Students’ outcomes were successful overall because tasks and materials were adapted to their needs, preventing them from striving for unattainable goals (Moate, 2010, p. 35).

Figure 10.

Question 9 Example.

Overall, we believe this was an effective lesson in terms of content and language. Nonetheless, we would also like to highlight that, although participation and motivation seemed high, students’ behaviour was rather disruptive at some points. This might have happened because having a lesson in the playground predisposes students to adopt a more “playful” attitude (Sulyman et al., 2022, p. 181). This problem was overcome with the cooperation of both the language and content educators. Hence, we would like to emphasise the importance of close collaboration between content and language teachers to ensure learners’ development of communicative abilities and content competencies in an environment conducive to learning (De la Barra et al., 2018, p. 112; Maggi, 2012, p. 62).

Despite these minor drawbacks, the lesson proceeded smoothly, and learners seemed to acquire the necessary motor and language skills. Results indicate that students developed their English knowledge effectively while engaging in healthy physical movement. This might be because pupils’ participation in physical activities can positively impact their English language skills (Fazio et al., 2015, p. 918). Implementing a CLIL approach in a Physical Education lesson, as Lamb and King (2020, p. 520) emphasise, has the potential to integrate motor and language contents in a stimulating and situated context. Thus, teaching a Physical Education lesson through a CLIL approach is possible and definitely worth of further research, as it favours embodied learning and can enhance academic performance (Kosmas et al., 2019, p. 70).

With respect to the research questions guiding this study, the findings provide several insights. Regarding Research Question 1, the results suggest that AI-supported CLIL tasks designed using the CLPS framework can support students’ perceived understanding of subject content and related language in a Physical Education context. Students reported confidence in understanding, applying, and producing language associated with warm-up routines while engaging in physical activity. They also reported that NaturalReader supported pronunciation and listening comprehension by providing consistent auditory models of key vocabulary and task instructions. Several learners indicated that the ability to replay audio input helped them notice stress patterns and word pronunciation before using the language during physical activities. This tool was particularly valued during warm-up explanations and task preparation, when students could independently access oral input without interrupting the flow of the lesson.

Regarding Research Question 2, the combination of embodied movement and digital scaffolding appeared to foster high levels of engagement and motivation, with learners valuing the opportunity to use language in action-oriented, collaborative tasks. In this context, Gliglish was perceived as particularly useful for interactive language practice, enabling students to rehearse short spoken exchanges and receive immediate feedback during task preparation. Learners reported increased confidence in using English in group-based physical activities after interacting with the tool.

Finally, in relation to Research Question 3, the findings highlight opportunities and challenges associated with integrating AI into CLIL practice, particularly when AI tools were used to support pronunciation modelling and interactive language practice within embodied tasks. AI tools were perceived as supportive mediators for pronunciation practice, comprehension, and interaction; however, their effectiveness depended strongly on task design, teacher guidance, and classroom management. Importantly, students did not perceive AI tools as replacing teacher guidance but as complementary supports embedded within the CLIL tasks. AI use was most effective when combined with clear instructions, peer collaboration, and physical engagement. Although the findings are exploratory and perception-based, they provide empirical insight into how AI can function as a pedagogical scaffold in embodied CLIL environments.

Taken together, these findings suggest that AI served as a mediating scaffold rather than an autonomous instructional agent. Tools such as NaturalReader and Gliglish supported specific micro-processes of CLIL, including pronunciation modelling, repeated exposure to language input, and low-stakes interactive practice. Their pedagogical value lay not in the technology itself but in its integration into embodied, task-based activities characteristic of Physical Education. This highlights AI’s potential to enrich cognitive, linguistic, and physical interaction when aligned with CLIL principles and guided by intentional task design.

5. Conclusions and Future Lines of Research

This study presented a teaching proposal for Physical Education grounded in Fernández Fontecha’s Content and Language Processing Sequence (CLPS) framework (Fontecha, 2010, p. 49; 2012, p. 324), with the aim of enhancing syllabus design in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) contexts. The four-module framework, focused on warm-up routines and physical health, offers adaptable resources for managing language demands during content selection and task planning. Its modular structure allows lessons to be implemented either independently or sequentially, depending on instructional needs and contextual constraints. The prior introduction of key vocabulary in the English classroom contributed to coherence between language and content instruction within the CLIL-in-PE lessons.

Due to time and logistical constraints, only one module of the framework was implemented, which limits the generalisability of the findings. Future research should aim to implement the full sequence of modules, involve larger samples or multiple groups, and examine the framework’s applicability across diverse educational contexts and learner profiles. Although access to ICT resources (e.g., Chromebooks, interactive whiteboards, and audio equipment) enabled the integration of AI tools in this study, such conditions may not be universally available. Nevertheless, the flexible design of the proposal allows teachers to adapt materials to their institutional realities, and future studies could explore differentiation strategies to better address diverse learner preferences and needs.

Another limitation of the study is the absence of a control group. Comparative designs involving CLIL and non-CLIL Physical Education groups would allow for a more precise examination of the specific contribution of CLIL approaches. Future research should also consider the systematic use of pre- and post-instruments alongside perception-based measures in order to strengthen the evaluation of learning outcomes. Within these constraints, the CLPS-based proposal showed promising potential for supporting students’ perceived content understanding, language use, and engagement, particularly when ICTs and AI tools were embedded as pedagogical scaffolds within embodied, task-based activities.

Overall, the study suggests that a coherent and flexible CLIL framework, supported by ICT-mediated tasks, can foster peer interaction, learner autonomy, and meaningful language use in Physical Education settings. While further research is needed to explore long-term effects and causal relationships, the proposal contributes to ongoing discussions on how digitally mediated CLIL practices can support diverse educational outcomes in PE contexts (Coral i Mateu, 2013, p. 20).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.R.-A.; methodology, C.R.-A. and A.J.; validation, A.J.; formal analysis, C.R.-A. and A.J.; investigation, C.R.-A.; resources, A.J.; data curation, C.R.-A. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.-A. and A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J.; visualization, A.J.; supervision, A.J.; funding acquisition, A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was conducted as part of normal classroom practice within the school’s regular Physical Education curriculum. The study did not involve any medical or clinical intervention, and it posed no risk or experimental treatment beyond standard educational activities. The research is considered an instance of pedagogical innovation within regular teaching and assessment practices. The data collected were fully anonymised and consisted solely of students’ survey responses and classroom observations with no identifiable information. Verbal authorization for the study was obtained from the school authorities and the classroom teacher prior to implementation.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on work originally developed as a Trabajo Fin de Máster within the official master’s program Máster en Formación del Profesorado de Educación Secundaria, Bachillerato, Formación Profesional y Enseñanza de Idiomas (Master’s in Teacher Training for Secondary Education, Upper Secondary, Vocational Training, and Language Teaching) at the Universidad Católica de Valencia. We thank the program coordinators and faculty for their guidance and academic support. We are grateful to Colegio Hermes for welcoming the internship and providing a supportive environment for this research, and we extend our thanks to the entire school community, especially Laura García Peláez, Head of Studies, for her guidance and continuous support, and Marcos, the Physical Education teacher, for his collaboration and professionalism, as well as the students of 2º de ESO, whose participation and enthusiasm made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akay, E., Yılmaz, B., & Yüncü, H. R. (2025). A CLIL-based model proposal for a solution to English-speaking anxiety of gastronomy and culinary arts students. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 36, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbury, B. (2000). Why I hated school PE. PE & Sport Today, 4(4). [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P., & Lindsay, D. (2010). Teacher training for CLIL in the Basque country: The case of the Ikastolas—In search of parameters. In D. Lasagabaster, & Y. Ruiz de Zarobe (Eds.), CLIL in Spain: Implementations, results and teacher training (pp. 162–187). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Brumfit, C. (1984). Communicative methodology in language teaching. Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Coral, J., Esquerda, G., & Benito, J. (2017). Design and validation of a tool to evaluate physical education and language integrated learning tasks. Didacticae: Revista de Investigación en Didácticas Específicas, (2), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coral i Mateu, J. (2013). Physical education and English integrated learning: How school teachers can develop PE-in-CLIL programmes. Temps d’educació, (45), 41. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D. (2007). Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010a). Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010b). The CLIL tool kit: Transforming theory into practice. In CLIL: Content and language integrated learning (pp. 45–73). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B., Jiao, W., Gui, S., Li, Y., & Fang, Q. (2025). Innovating physical education with artificial intelligence: A potential approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1490966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2007). Discourse in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton-Puffer, C. (2008). Outcomes and processes in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Current research from Europe. In W. Delanoy, & L. Volkmann (Eds.), Future perspectives for English language teaching (pp. 139–157). Carl Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Danilov, A., Salekhova, L., & Yakaeva, T. (2018). Designing a dual focused CLIL-module: The focus on content and foreign language. In INTED2018 Proceedings (pp. 1972–1978). IATED. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Barra, E., Veloso, S., & Maluenda, L. (2018). Integrating assessment in a CLIL-based approach for second-year university students. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 20(2), 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, J. (2024). The arts as the content-subject for content and language integrated learning (CLIL): How the signature pedagogies of arts education align to CLIL aims. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 18(4), 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Urmeneta, C., & Sánchez Sola, A. (2009). Language learning through tasks in a content and language integrated learning (CLIL) science classroom. Porta Linguarum, 11, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, M., Ashraf, A., & Bilal, M. (2016). ESL learners’ writing skills: Problems, factors and suggestions. Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 4(2), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, A., Isidori, E., & Bartoll, Ó. C. (2015). Teaching physical education in English using CLIL methodology: A critical perspective. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Costales, A. (2023). Cognitive development in CLIL. In D. L. Banegas, & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 127–140). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fontecha, A. F. (2010). The CLILQuest: A type of language WebQuest for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). CORELL: Computer Resources Language Learning, 3, 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fontecha, A. F. (2012). CLIL in the foreign language classroom: Proposal of a framework for ICT materials design in language-oriented versions of content and language integrated learning. Alicante Journal of English Studies, 25, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbic, P. (2011). Teaching using a blended approach–what does the literature tell us? Educational Media International, 48(3), 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goris, J. A., Denessen, E. J. P. G., & Verhoeven, L. T. W. (2019). Effects of content and language integrated learning in Europe. A systematic review of longitudinal experimental studies. European Educational Research Journal, 18(6), 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartiala, A. (2000). Acquisition of teaching expertise in content and language integrated learning [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Turku]. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2015). The impact of CLIL on affective factors and vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 19(1), 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning (1st ed.). Center for Curriculum Redesign. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D., Chen, J., Li, Y., & Wang, M. (2025). Technology-enhanced content and language integrated learning: A systematic review of empirical studies. Educational Research Review, 47, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y. (2019). The effectiveness of a CLIL basketball lesson: A case study of Japanese junior high school CLIL. English Language Teaching, 12(11), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. (2022). Effects of artificial intelligence (AI) and native speaker interlocutors on ESL learners’ speaking ability and affective aspects. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 25(2), 9–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, P., Ioannou, A., & Zaphiris, P. (2019). Implementing embodied learning in the classroom: Effects on children’s memory and language skills. Educational Media International, 56(1), 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, P., & King, G. (2020). Another platform and a changed context: Student experiences of developing spontaneous speaking in French through physical education. European Physical Education Review, 26(2), 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J. M. (2009). Language attitudes in CLIL and traditional EFL classes. International CLIL Research Journal, (2). Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-202504083116 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Llinares, A., Morton, T., & Whittaker, R. (2012). The roles of language in CLIL. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R., Holmes, W., Griffiths, M., & Forcier, L. B. (2016). Intelligence unleashed: An argument for AI in education. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Macwan, H. J. (2015). Using visual aids as authentic material in ESL classrooms. Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL), 3(1), 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, F. (2012). Evaluation in CLIL. In F. Quartapelle (Ed.), Assessment and evaluation in CLIL (pp. 57–74). Ibis Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D. (2002). CLIL/EMILE–The European dimension. Action, trends and foresight potential. UNICOM, Continuing Education Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Moate, J. (2010). The integrated nature of CLIL: A sociocultural perspective. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(3), 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Borrego, M. M. (2020). The role of ICT in CLIL. Video as a didactic material [Master’s dissertation, Universidad de Jaén; Universidad de Córdoba]. [Google Scholar]

- Mosston, M., & Mueller, R. (1974). Mission, omission and submission in physical education. In Issues in physical education and sports (pp. 91–107). National Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Acevedo, R., Marco, L., & José, M. (2013). WebQuests and the development of the reading skill [Master’s thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza]. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H. T. M., Nguyen, H. T. T., Gao, X., Hoang, T. H., & Starfield, S. (2023). Developing professional capacity for content language integrated learning (CLIL) teaching in Vietnam: Tensions and responses. Language and Education, 38(1), 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N. (2021). Tools for team-taught CLIL implementation. The Journal of the Japan CLIL Pedagogical Association (JJCLIL), 3, 10–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Ceallaigh, T. J., Ní Mhurchú, S., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Balancing content and language in CLIL: The experiences of teachers and learners. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 5(1), 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patty, J. (2024). The use of AI in language learning: What you need to know. Journal Review Pendidikan dan Pengajaran (JRPP), 7(1), 642–654. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cañado, M. L. (2012). CLIL research in Europe: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 15(3), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F., & Ruíz Omeñaca, J. V. (2011). La educación física en centros bilingües de primaria inglés-español: De las singularidades propias del área a la elaboración de propuestas didácticas prácticas con AIBLE. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 24, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Reiko, Y., Hideo, T., & Katsuaki, O. (2015). Students’ perceptions of CLIL and topics in EFL University classrooms. Journal of Humanities and Sciences, Nihon University, 21(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-García, C., Capella-Peris, C., Chiva-Bartoll, O., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2020). A mixed methods study to examine the influence of CLIL on physical education lessons: Analysis of social interactions and physical activity levels. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, F. L., Anderson, N. J., Grabe, W., & Komiyama, R. (2013). Instructional enhancements to improve students’ reading abilities. English Teaching Forum, 51, 2. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1014068 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sulyman, H. T., Olaosebikan, A. S., Olosunde, J. O., & Oladoye, E. O. (2022). Primary school playground and pupils physical skill acquisition. Indonesian Journal of Sport Management, 2(2), 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K. W., Wei, L., & Loh, E. K. Y. (2025). Enhancing students’ content and language development: Implications for researching multilingualism in CLIL classroom context. Learning and Instruction, 96, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts-Taffe, S., & Truscott, D. M. (2000). Focus on research: Using what we know about language and literacy development for ESL students in the mainstream classroom. Language Arts, 77(3), 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q., Jiang, J., Bai, W., Yin, Z., Liao, Z., & Zhong, X. (2025). Application of digital-intelligent technologies in physical education: A systematic review. Frontiers Public Health, 13, 1626603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.