Abstract

The fanasváhter is a special tool used by boatbuilders to determine how steeply the boatboards should be positioned. Sámi mathematics teacher educators, together with Sea Sámi boatbuilders and a pre-service mathematics teacher, present a descriptive case study of a Sea Sámi boatbuilder’s use of this tool. The aim is to reveal mathematical understanding that might be relevant for vocational school teaching. Firstly, we analyze a semi-structured interview with a skilled boatbuilder with respect to knowledge and values embedded in the use of the fanasváhter. Because the Sea Sámi boatbuilding tradition was almost extinct after the Nazis’ devastation in World War II, there is a need for some creativity in the boatbuilders’ regeneration of Sea Sámi boatbuilding. An analysis of the use of the fanasváhter with respect to creativity reveals how creativity is important in Sea Sámi boatbuilding. The analysis further reveals that Sea Sámi boatbuilders compare angles, but they do not refer to any angles measured in degrees. This contrasts with traditional school mathematics. Thus, the Sea Sámi boatbuilders’ mathematics is less abstract and more intuitive than traditional school mathematics.

Keywords:

boatbuilding; Sea Sámi; angles; creativity; fanasváhter; duodji; spatial geometry; steepness 1. Introduction

Sámi University of Applied Sciences (SUAS) is an Indigenous higher education institution located in northern Scandinavia. According to its strategy document, SUAS (2022) strengthens and promotes Sámi languages and traditional knowledge through interdisciplinary education and research. This article presents an example of how SUAS mathematics teacher educators, together with Sea Sámi boatbuilders and a pre-service mathematics teacher, investigate how to prepare the ground for designing a teaching unit about the fanasváhter (boat spirit level), a special tool used in building the spissá, a traditional wooden rowboat (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The fanasváhter is an instrument for measuring the boatboards’ slope, “... neavvu mainna mihtida man állut fanasfiellut galget lea” (Nilsen, 2021, p. 37). Explanations of Sámi terms appear throughout the text, and a list of definitions is included in the Appendix A.

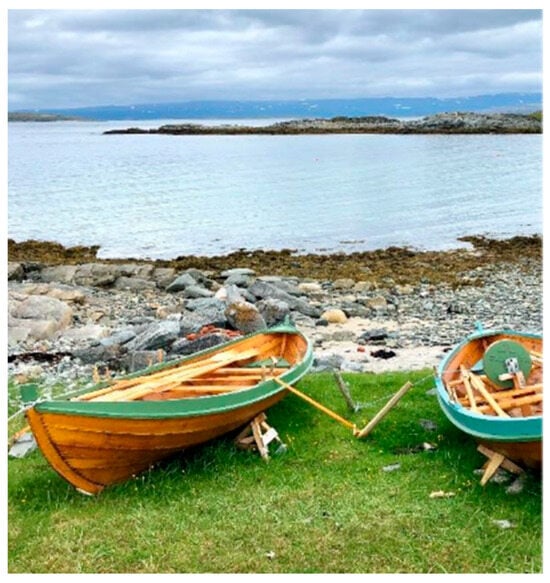

Figure 1.

Mearrasiida spissát by the shore in Porsanger, Norway. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

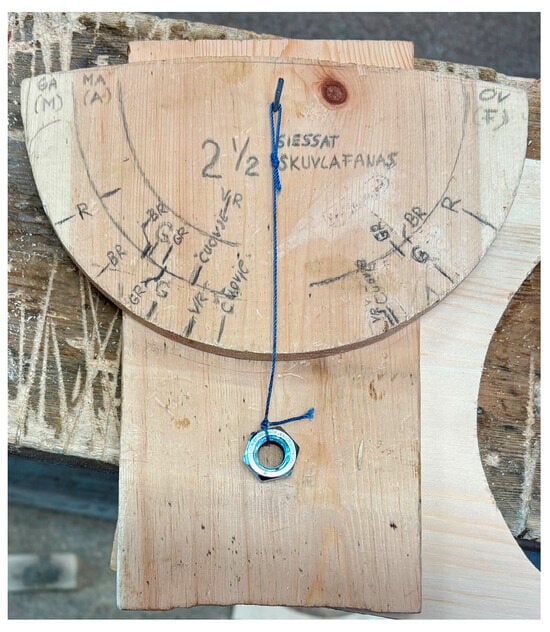

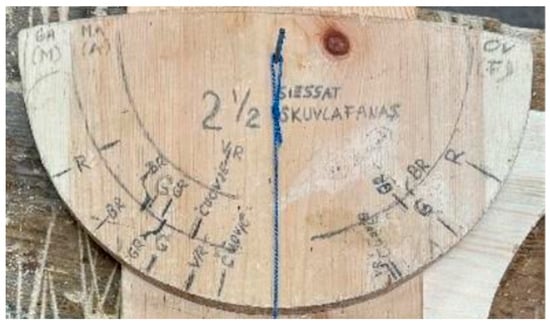

Figure 2.

How the fanasváhter reflects the steepness of a boatboard. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

The Sámi are an Indigenous people of the Arctic who traditionally inhabit northern areas of Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula of Russia (Berg-Nordli & Gaski, 2023). There are nine Sámi languages still in use (Duolljá et al., 2025). In this article, Sámi language refers to North Sámi unless otherwise specified. The Sea Sámi are a coastal people whose traditional livelihoods include fishing, hunting, and smallholding (Nordlige folk, 2025). Blom (1830/1977) describes the Sea Sámi as enterprising fishermen who were persistent, capable, and fearless sailors. The Sea Sámi center Mearrasiida in Porsanger, Norway, keeps the Sea Sámi boat tradition alive (Mearrasiida, n.d.) by passing down knowledge about boatbuilding in a traditional way. The boatbuilding awakens an interest in boats and their usefulness, “fanasdahkan moriha beroštumi sihke fatnasiidda ja daid ávkkásteapmái” (Hans Oliver Hansen, personal communication, 24 September 2025) through Mearrasiida’s offering of spissát for rent to the local population and through their cooperation with the local school. During the winter of 2024/2025, Mearrasiida built a traditional spissá for the school, and the students participated in parts of the practical work on a weekly basis.

The fanasváhter is made of a semicircular piece of wood fastened to a plank, as shown in Figure 2. From a nail in the semicircle’s center hangs a string with a plumb tied to its end (in this case, the plumb is a nut). When you tilt the fanasváhter (or just váhter) sideways, the string moves correspondingly along the semicircular arc. The steepness of each board is marked at the point where the váhter’s string crosses the arc. Mathematicians treat steepness as something that can be measured in degrees. Thus, an intuitive interpretation of the use of the fanasváhter from a Western mathematical perspective is that it is somehow related to ‘angles’.

The Sea Sámi boatbuilding tradition became almost extinct after World War II because when the Soviets liberated the eastern part of Finnmark, the Nazis used so-called scorched-earth tactics (Rein, 2024); they burned down everything in Finnmark and North Troms during their withdrawal. This caused a situation with a break in the continuous development of the Sea Sámi boatbuilding tradition. Today, Mearrasiida works with investigations of the Sámi boats that more or less completely disappeared in the areas from Tana to North Troms. Contemporary Sea Sámi boatbuilders like those at Mearrasiida are now regenerating the Sea Sámi boatbuilding tradition. Before designing any teaching unit, there is a need to identify and describe the knowledge embedded in the use of the fanasváhter. The first research question is: What is the knowledge embedded in the use of the fanasváhter? Because the aim of this study is to prepare the ground for a mathematics teaching unit, mathematical knowledge is central here.

The Mearrasiida project for the regeneration of the local Sea Sámi spissá boatbuilding tradition started in 2017 and has developed into a systematic investigation of how to build boats in accordance with the old traditions. Therefore, they must include some creative reasoning in their work. Guttorm (2011b) describes creativity in the work of a Sámi duojár (handcrafter), and Sriraman (2008) describes how creativity is important in the work of professional mathematicians. Their findings support our idea to see creativity as a central issue in a project where mathematics educators participate in studying the use of the fanasváhter in Sea Sámi boatbuilding. Therefore, we investigate how creativity comes to the surface in the use of the fanasváhter. The use of the fanasváhter can be described from different perspectives, where the role of creativity may vary. The second research question is: How does creativity come to the surface through different perspectives on the use of the fanasváhter? To shed light on the research questions, we first present the skilled Sea Sámi boatbuilder Hans Oliver Hansen’s description of knowledge related to the fanasváhter. This choice aligns with Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) point that to come up with creative thinking within a domain, you need thorough knowledge of that domain.

Pre-service mathematics teachers at SUAS have previously visited Mearrasiida. One outcome of that visit was a video about Sea Sámi boatbuilders’ ways of measuring when making a spissá (Karlsen et al., 2023). The video also shows the fanasváhter in use. Those pre-service teachers studied how to use the video as a basis for teaching about measuring (Fyhn et al., 2024a), and the focus of their study concerned length measuring. The video gave rise to the idea of the fanasváhter project, to carry out a separate study on whether the fanasváhter could serve as a basis for a mathematics teaching unit in vocational school.

According to Norway’s Core Curriculum, teaching and training must “seek a balance between respect for established knowledge and the explorative and creative thinking required to develop new knowledge” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 7). This supports our approach, where the analysis in the second step concerns how the different perspectives relate to creativity. We are seeking a foundation for including a new element in mathematics education; we are not aiming to design a teaching unit that fits into a mathematics curriculum.

In culture-based mathematics education, there is a risk that culture is used merely as a tool for teaching mathematics and that the outcome is a devaluation of culture (Pais, 2011). To avoid such risks, the Māori mathematics education community developed the framework ‘cultural symmetry’ (Meaney et al., 2022), in which cultural activities and language are identified and valued before any mathematics is considered. To ensure that the fanasváhter is valued for its own sake and not reduced to a tool for teaching mathematics, we use cultural symmetry as the framework for our analysis. Our focus is on the use of the fanasváhter in a Sámi context, and Sea Sámi boatbuilders own this knowledge. Thus, two Sea Sámi boatbuilders are co-authors of this article.

The fanasváhter project starts with a visit to the Mearrasiida boatbuilders’ workshop, this time with new pre-service teachers and two teacher educators. Because the project’s context is Sea Sámi boatbuilding, we first present Sámi traditional knowledge and our reasons for choosing the term ‘regeneration’ instead of the more established ‘revitalization’ of boatbuilding. This is followed by a subsection about traditional boatbuilding in Norway and a subsection about creativity. Finally, before the methods section, we present different perspectives on mathematics, followed by a subsection about ethnomathematics.

1.1. Sámi Traditional Knowledge and Knowledge Transfer

Sámi traditional knowledge is “the collective wisdom and skills that the Sámi people used to enhance their livelihood for centuries. It has been passed down from generation to generation both orally and through work and practical experiences” (Porsanger & Guttorm, 2011, p. 18). Traditional knowledge is experience-based; it relies on long-term observations and is often focused on practical applications (Turi, 2013). This contrasts with the traditional, deductive Western school mathematics, where the teacher gives lessons by introducing and explaining rules to the students, who are then expected to carry out exercises or tasks to practice these rules. The Sámi way of learning aspects of their culture has been neglected over the years, but we now see a change in that. The curricula now include Sámi matters and provide opportunities to strengthen Sámi perspectives. Balto (2005) points out that this is not an easy task, as it is a process of decolonization. There is a need for a change not only in the curricula but also in the minds of the Sámi themselves and the teachers. Norwegian ways of teaching are still very strong, even in Sámi schools.

Guttorm (2011a) distinguishes between two different aspects of knowledge: while the Sámi concept diehtit (to know about something) is primarily associated with theoretical knowledge, máhttit (to know something or to master something) is linked to practical knowledge or skills. Regarding boatbuilding, diehtit refers to any material you can find in a book; it means the knowledge you can describe, discuss, and talk about; to know it from a theoretical perspective. Máhttit refers to the practical skills, the knowledge that is in the boatbuilders’ hands and heart. Sámi traditional knowledge develops over time as part of the culture. Sámi culture is not static, and neither is Sámi traditional knowledge.

Duodji, Sámi traditional handcraft, is part of Sámi traditional knowledge. It is part of Sámi cultural heritage. Duodji thinking is an integrated part of the intellect for those who are born and raised in the culture. Duodji is both culture and livelihood, and duodji is an important identity marker of Sámi society (Sámediggi, n.d.). Nature influences where, when, and why you make duodji items for practical use. The Sámi cultural way of living includes duodji items, as well as the creation of duodji; the way of living is reflected in duodji. According to Guttorm (2011a), duodji artisans and Sámi craftspeople know what to do (diehtit) and how to do it (máhttit), and they add their personal style to create a product that is useful in contemporary society. A Sámi boatbuilder is a fanasdahkki (boatbuilder) or a duojár. Some boatbuilders can be both.

Sámi traditional knowledge transfer is a process in which children are prepared for life by participating in practical traditional activities already as small children. According to Balto (2005), knowledge transfer is a way of developing independent individuals who can survive in a given environment and achieve self-esteem, trust, joy, and a zest for life. Children are given the opportunity to try out things and do things wrong and then are encouraged to try again; the idea is that failure is also good learning. Learning by doing practical things, learning to see solutions in different ways, and finding one’s own ways are central parts of Sámi child-rearing.

1.2. Reversing, Revitalization, and Regeneration of Knowledge

Regarding work with endangered Indigenous languages, Hohepa (2006) distinguishes between the three terms reversing, revitalization, and regeneration in relation to her work with the Māori language. Reversing involves going backwards, returning to where or what was before, while revitalization reflects notions of life and of the essentiality of language to the existence of human cultures. To her, neither reversing nor revitalizing language reflects enough of a sense of development and growth. Therefore, she prefers to term the process of intervention language regeneration, because regeneration speaks to her more of growth and regrowth, development, and redevelopment.

Regarding the survival and regeneration of language, she refers to four roles for print literacy. One is validating the contemporary relevance of the language and giving it status. Another one is supporting the preservation of traditions of the past for future generations. A third role of print literacy is to ensure a wider variety of functions for a language. A fourth role is to recreate the language within a changing culture, within a changing society. We find these roles relevant for the Sea Sámi regeneration of boatbuilding as well.

Applying Hohepa’s (2006) four roles to Sea Sámi boatbuilding means that we replace print literacy with Sea Sámi boatbuilders, while Sea Sámi boatbuilding replaces language. One role is that Sea Sámi boatbuilders validate the contemporary relevance of Sea Sámi boatbuilding by offering the population opportunities to rent boats at a low cost and by arranging a local rowing regatta during the national cultural heritage week (Kulturvernforbundet, n.d.). By creating a boat for the school in which students participate, they support the preservation of knowledge for future generations, which represents the second role. They also support the preservation of knowledge by having built a three-room motorboat together with staff from the Kokelv Sea Sámi Museum (RiddoDuottarMuseat, n.d.), which is located 55 km away. This motorboat is now in use at the Kokelv Museum, together with other rowboats built by Mearrasiida. The third role is that the boatbuilders ensure a wider variety of functions for the Sea Sámi language by contributing to Nilsen’s (2021) book about the sea boat, mearrafanas. Finally, they recreate boatbuilding within a changing culture by creating boats that are appropriate for use in contemporary Sea Sámi society, for instance, the school’s boat and the Kokelv museum’s motorboat.

1.3. Traditional Boatbuilding in Norway

The boat was the “nerve” of the older coastal societies in Norway, as well as in areas with lakes and rivers. The boat was crucial for survival (Hole, 2002). Traditionally, small wooden boats with one or two fishermen constituted the backbone of the coastal societies (Maurstad, 2010). People rowed and sailed these boats. According to Eldjarn and Godal (1990), the basic concepts for open boats along the coast of Norway are mainly the same nowadays as they were 1200 years ago.

Boats have been central to the Sea Sámi way of living, and the Sámi were renowned as skilled boatbuilders (Nilsen, 2021). Klepp (1984) refers to a report from the period 1840–1845, which shows that a considerable number of boats were built in the areas of Senja, Tromsø, Alta, and Porsanger. Hans Oliver Hansen (personal communication, 7 March 2025) claims that Porsanger had a tradition of building larger boats until the 18th century, when the forest started to disappear. According to Blom (1830/1977), the Sea Sámi were capable craftsmen, and among these were many skilled boatbuilders. More than 400 years ago, Friis (1545–1614) pointed out that the Sea Sámi were skilled carpenters who built ships, yachts, and boats (Friis, 1881). According to the Sea Sámi author Larsen (1949/2014), the Sea Sámi have been skilled boatbuilders since ancient times. The sagas of the Viking kings of Norway (Sturlasson, ca. 1230/1959) also refer to the Sámi as skilled boatbuilders. In 1138, Sigurd Slembe escaped from a fight in the south, and during the following winter, he lived in hiding under a rock at the bottom of a fjord on Hinnøy in Northern Norway. During that winter, some Sámi boatbuilders made him pine-tree ships, tied together with tendons. According to the quatrain, these ships were so fast that others could not follow (Sturlasson, ca. 1230/1959).

The term nordlandsbåt is used as an overarching term for boats made along the coast of Northern Norway (Klepp, 1984). A nordlandsbåt is made of wooden planks that overlap lengthwise. The planks are joined with nails that go through the overlaps. This method of construction is called ‘clinker-built’ (Eldjarn & Godal, 1990; Nilsen, 2021). The North Sámi verb for ‘to clink’ is duorrat. Traditional Sea Sámi boats are clinker boats (Nilsen, 2021). After World War II, motorboats took over the nordlandsbåt’s role as the main fishing boat along the Norwegian coast. However, during the 1970s in Norway, a coastal culture movement or awakening took place, and the nordlandsbåt assumed a new role as a carrier of culture and tradition (Hole, 2002). Eldjarn and Godal (1990) document and describe how the nordlandsbåt was built. Their descriptions are based on several informants.

Today, boatbuilders can be found at Gunnar Eldjarn’s boatbuilding business (Eldjarn et al., 2025) in Tromsø, at Båtskott Trebåtbyggeri (Museet Kystens Arv, n.d.) in Trøndelag, at Hardanger Maritime Center (n.d.), at Hardraade Viking Ship Center (Hardraade, n.d.) on Lake Tyrifjorden, at Hvaler Kulturvernforening (n.d.), and in other places. These boatbuilders build boats by following strict and detailed descriptions of how boats were built in the old days. This way of boatbuilding is based on thorough studies such as those by Eldjarn and Godal (1990), where the aim is to make exact copies of old boats. Many of these were built a long time ago. This way of boatbuilding contrasts the Mearrasiida way, because the Sea Sámi boatbuilders’ aim is not to make copies of old boats, but to regenerate an old boatbuilding tradition.

1.4. Creativity

Creativity is the ability to produce work that is novel (i.e., original and unexpected) but also appropriate, useful, and adaptive in relation to task constraints (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). According to these requirements, the idea of an original and special boat that can be considered novel but useless is not a creative idea. Likewise, the idea of a boat that seems to be very useful but is neither unique nor original is not a creative idea. According to Csikszentmihalyi (1996), creativity can be observed only in the interrelations within a system made up of three main parts: the domain, the field, and the individual person. From a Sámi perspective, Sámi traditional knowledge is an example of a domain, and at a finer resolution, Sea Sámi boatbuilding can also be seen as a domain. According to Csikszentmihalyi (1996), domains are in turn nested within what we usually call culture, or the symbolic knowledge shared by a particular society. The field includes all the individuals who act as gatekeepers to the domain; regarding Sea Sámi boatbuilding, the field consists of Sámi boatbuilders. They decide whether a new idea or a new product should be included in the domain. They select which new works deserve to be recognized, preserved, and remembered. The individual person is the third component of the creative system.

Creativity occurs when a person, using the symbols of a given domain such as music, engineering, business, or mathematics, has a new idea or sees a new pattern, and when this novelty is selected by the appropriate field for inclusion into the relevant domain.(Csikszentmihalyi, 1996, p. 28)

If the field chooses to include some novelty, it finds this novelty to be useful, which aligns with Sternberg and Lubart’s (1999) criterion for creativity. Csikszentmihalyi (1996) refers to three requirements for being an original (and creative) thinker. First, you must truly know the domain, like having some kind of large internal database. This means that simply being super interested is not enough. Second, you must be interested in coming up with something new. Third, you must have the ability to get rid of trash ideas, because no one can come up with smart ideas constantly. To truly know the domain of Sámi traditional knowledge means that both the máhttit (to master something) and the diehtit (to know about something) parts of knowledge are included and considered important.

Sriraman (2008) points out that an individual’s personal background and her/his position within a domain naturally influence the likelihood of the individual’s contribution. Regarding research in the domain of mathematics, he claims that a mathematician working within the culture of a research university is likely to produce research papers. Such an individual is immersed in a culture where ideas flourish, and she/he has time available for thinking.

From a Sámi perspective, duodji is an example of a domain. According to Guttorm (2011b), traditional duodji changes as people, their living conditions, needs, and relationships change. Thus, even traditional crafts involve creative solutions. She investigates cultural expressions in the domain of duodji, where the starting point is Sámi traditional knowledge. Guttorm (2011b) provides an example in which one skilled person creates a new approach that is accepted by the field because the outcome works within the cultural context. She refers to Eira (2004), who explains how she used gámasgotturiid, fur from reindeer legs, in making fur shoes for winter use. She faced a problem when the butcher cut the harvested fur at the knee instead of using the traditional cutting method, where the fur from the entire leg was kept in one piece. The duojár had a thorough knowledge of the domain, which means, among other things, that she knew how the fur could be used and how it could not be used. Her knowledge of the domain includes the máhttit as well as the diehtit aspects of knowing. She solved the problem by using the fur in a new way, and as a result, something new emerged in fur-shoe sewing. Sewing smaller parts of fur into a whole had been done before, but this particular method was new to her. The way she used the fur could fit the traditional Sámi sewing pattern. From the perspective of Sternberg and Lubart (1999), her work was both novel and useful and was therefore creative.

Referring to Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) terms, we focus on the domain of Sea Sámi boatbuilding, while Sea Sámi boatbuilders constitute the field. The Sea Sámi boatbuilders Hans Oliver Hansen and Ove Stødle are two individual persons who operate within this domain. Regarding our study of creativity in boatbuilding, truly knowing the domain is fundamental for the ability to come up with something that can be novel and/or useful. Sea Sámi boatbuilding is practical work, and we aim to show how knowing the domain involves both the diehtit and the máhttit aspects of knowing. In particular, mathematical knowledge is focused on in our study.

1.5. Perspectives of Mathematics

The concepts of mathematics have developed throughout history. People have had thoughts, ideas, meanings, and presuppositions about what mathematics is and should be, and Western societies have shared the idea of mathematics as something unambiguous and universal (Barton, 2008). This may explain why Norway in 2025 has no Sámi mathematics curriculum, despite the fact that most other subjects received Sámi curricula 30 years ago (Fyhn et al., 2024b). Russell (2004) claims that the mathematics we use is a Western invention; mathematics as a demonstrative, deductive system with mathematical proofs is an inheritance from Pythagoras. Sriraman (2013) shows how the Chinese approach contrasts with this; the Chinese published several major works on mathematics long before the Greek heyday. However, the Chinese did not care about proofs; they were concerned with whether a formula worked or not.

In contrast to the Western perspective of mathematics as something unambiguous and clear, Lakoff and Núñez (2000, p. 365) argue that “[h]uman mathematics is embodied; it is grounded in bodily experience in the world.” They distinguish between two different conceptions of space: Natural Continuous Space (NCS) and Space as a Set-of-Points (SSP). NCS is the three-dimensional space in which we live our lives and move our bodies. This space is such a natural part of our daily lives that we do not question its existence. The conception of Space as a Set-of-Points is related to the Cartesian coordinate system, a 17th-century invention by Descartes. School mathematics mainly relates to SSP; SSP allows us to make precise calculations.

During the 1980s, D’Ambrosio (1999) introduced the term ethnomathematics: each culture has developed its own ways, styles, and techniques for performing and responding to the search for explanations, understanding, and learning. Western mathematics is one of these. Sriraman’s (2013) example shows how ancient Chinese mathematics is another. Barton (2008) underlines the importance of considering language, as different languages and cultures express concepts such as numbers and location in different ways. In Polynesian languages, for instance, reference is much less egocentric than in English. These languages take greater account of the listener’s point of view when explaining where something is placed.

Bishop (1988) explains mathematics as a cultural product that has developed as a result of six fundamental activities: counting, locating, measuring, playing, designing, and explaining. Regarding explaining, the Chinese way of accounting for the existence of a rule is that it works, while the Western mathematical approach relies on a ‘scientific’ proof. According to Keskitalo et al. (2017), there is no proof in Sámi traditional knowledge. Like in ancient China, the Sámi do not prove their cultural claims; these claims are experience-based.

1.6. Ethnomathematics in Education

Many early studies of ethnomathematics in education were outsider perspectives from well-meaning researchers. Doolittle (2006) points out the risk of oversimplification, like in the well-meaning utterance ‘the tipi is a cone’.

[T]he tipi is not a cone. Just look at a tipi with open eyes. It bulges here, sinks in there, has holes for people and smoke and bugs to pass, has a floor made of dirt and grass, and has various smells and sounds and textures. There is a body of tradition and ceremony attached to the tipi, which is completely different from and rivals that of the cone.(Doolittle, 2006, p. 19)

Oversimplifications like calling the tipi a cone may lead Indigenous students away from their culture because the culture is reduced to a mere starting point for mathematics. Vithal and Skovsmose (1997) point out challenges related to introducing ethnomathematics if the situation becomes one where each cultural group is expected to have its own culture-based mathematics. During the apartheid period in South Africa, the government stated that each population group should have its own schools and its own education authority. The outcome was that schools reproduced inequalities.

Mellin-Olsen (1986) warned about the Norwegian school’s “equity idea”, the idea that “equal opportunities” means “equal curriculum” or “equal content”. This way of thinking led to the notion that “[t]he carpenter’s son should rather learn about equations than digging into carpentry geometry” (Mellin-Olsen, 1986, p. 104). This represents the opposite challenge to the one pointed out by Vithal and Skovsmose (1997).

‘Cultural symmetry’ is a three-step framework developed over several years to support Indigenous students’ opportunities to value their cultural traditions and practices when working with culture-based mathematics (Meaney et al., 2022). Step 1 is to describe the cultural knowledge in focus and to identify the cultural values connected to the actual practices and artifacts. Step 2 is to examine the cultural practices and discuss them from a range of perspectives, one of which is mathematics. The third and final step involves considering how mathematics can add value to cultural artifacts and practices without detracting from the cultural understandings.

Fyhn et al. (2017) describe how a group of researchers and Sámi teachers together investigated opportunities for including ruvden, a Sámi braiding, in mathematics education. First, two teachers, one researcher, and two schoolgirls demonstrated, explained, and valued ruvden; this represents Step 1 in cultural symmetry. Then the cultural practice of braiding was discussed from a duodji perspective, from an algebra perspective, and from a combinatorics perspective; Step 2 in cultural symmetry. As part of the ruvden project, two schoolgirls participated in making a video about ruvden and mathematics (Fyhn et al., 2014). The algebra perspective focused on ruvden with four, eight, twelve, and sixteen threads. It turned out that over the summer vacation; the girls experimented with using the ruvden procedure for braiding with 40 threads. They knew the number of threads had to be divisible by four. This experimentation is an example of Step 3 in cultural symmetry; investigating whether and how Western mathematics can increase the value of the actual cultural tradition or practice.

2. Materials and Methods

When the secondary school mathematics teacher Ann-Kristine started working at SUAS, she was searching for ideas for teaching mathematics in Sámi vocational schools. This was welcomed by the first author, Anne, who supervised the pre-service teachers who made the boatbuilding video (Karlsen et al., 2023) together with the boatbuilders Hans Oliver and Ove. Anne suggested studying opportunities for using the fanasváhter, and Ann-Kristine agreed.

2.1. The Fanasváhter

Figure 3 shows a detailed photo of a fanasváhter in which the plumb is replaced by a nut. The nut hangs on a string from a nail, and because of gravity, the string remains vertical even when the fanasváhter is tilted.

Figure 3.

A fanasváhter. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

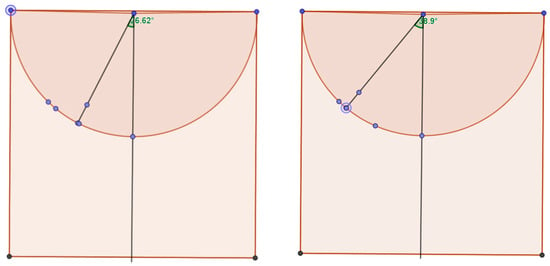

The reason for suggesting the fanasváhter as an approach to vocational school mathematics is that each student can experience how the angle between the plumb string and the line perpendicular to the boatboards increases when she or he increases the boatboards’ steepness. The comparison of angles can be done without referring to any angle size in degrees. This is shown in Figure 4. The approach aligns with Freudenthal’s (1983) warning against the measure approach: “angles will be distinguished as different or equal before measuring angles is discussed” (Freudenthal, 1983, p. 323). You do not need to know any formal mathematics to experience this relation between the angle and the boatboards’ steepness, but you must have experienced the force of gravity.

Figure 4.

The angle between the plumb string and the line perpendicular to the boatboard increases when the boatboard is steeper.

2.2. The Authors

Anne is a researcher in the field of mathematics education. She grew up in Northern Norway and learned how to maneuver a rowboat before she learned any English at school. Anne worked as a mathematics teacher and school vice principal at the school near Mearrasiida before she entered teacher education and research. She knew about Mearrasiida’s competence beforehand, so the idea of cooperation with them was a natural choice for her. Ann-Kristine is a mathematics teacher in vocational school as well as a mathematics teacher educator. Two pre-service mathematics teachers joined the teacher educators on a visit to Mearrasiida’s boatbuilders Hans Oliver and Ove to take a closer look at the fanasváhter and how they use it. Pre-service teacher Nils Ailo volunteered to participate in writing an article about this study. Before visiting Mearrasiida, the pre-service teachers participated in a lesson at SUAS focusing on how the fanasváhter works and on possible mathematical interpretations of it. Because the number of pre-service mathematics teachers at SUAS is low, teacher educators can invite pre-service teachers to participate in developing new approaches to teaching. This opportunity for pre-service teachers to participate in research and developmental work is an advantage of a small institution.

Ann-Kristine, Nils Ailo, and Hans Oliver are native speakers of North Sámi; Ove is a second language learner, while Anne has completed some courses. Three of the authors have competences in duodji. The professional duojár and boatbuilder Ove grew up in a Sea Sámi community. He studied Indigenous art and duodji at the university level and completed a one-year study in garraduodji (hard duodji) at the Sámi education center in Johkamohkki/Jokkmokk, Sweden. In addition to developing his own style, Ove highlights the importance of regenerating traditional materials and techniques in duodji, for example, through his work with seal fur, in which sustaining the craft depends on passing on both the knowledge (diehtu) and the practice (máhttu). The pre-service teacher Nils Ailo is a certified reindeer herder who participates in the daily work of his siida (reindeer herding community). Because of his reindeer herding background, duodji has been an integrated and important part of his life since early childhood. Nils Ailo also completed a one-year duodji program at SUAS as part of his teacher education. He chose duodji studies to utilize his reindeer herding background in his education. Ann-Kristine is a dálon (a permanent resident Sámi) who grew up learning traditional dipmaduodji (soft duodji) from her grandmother and her mother. Her mother’s birthplace is on Finnmarksvidda (the Finnmark mountain range), without any nearby roads. Many reindeer herders pass through this area, which is a hub during the reindeer migration. So duodji, fish, and meat were important trade goods. To survive in the harsh wilderness, it was also important to make duodji for sale as a source of income; these items were sold to local craftsmen in the towns around. Today, Ann-Kristine has her own small duodji company in addition to her job as a teacher. The following subsection provides a presentation of the author Hans Oliver.

2.3. The Mearrasiida Boatbuilder Hans Oliver

The fanasdahkki (boatbuilder) Hans Oliver is a Sea Sámi carpenter who also builds boats. He built his first boat around forty years ago and continued building some more boats while working as a carpenter. Since Mearrasiida applied to the Sámi parliament for funding for their first boatbuilding project in 2017, Hans Oliver has been central to their systematic regeneration of the local Sea Sámi boatbuilding tradition. Mearrasiida’s boatbuilding projects have attracted attention from boatbuilders and cultural workers from many parts of the north. Today, Hans Oliver is central to this boatbuilding work. His expertise has been crucial for the boatbuilding projects’ development and visibility. The Mearrasiida boatbuilding projects have been important to the local community by strengthening the local cultural heritage and creating local pride. The boatbuilding projects have also contributed to the development of traditional competences that would otherwise be in danger of being lost.

Hans Oliver has supervised several apprentices who have built boats at Mearrasiida; his first apprentice was the duojár Ove, who later built more boats in addition to his other duodji work. In the school year 2024–2025, Hans Oliver is leading the process of building a spissá for the local school. Figure 5 shows the miniature spissá he made for them. The schoolchildren play a game about using the spissá in Sea Sámi seasonal activities related to gathering food and other resources from nearby nature.

Figure 5.

Miniature spissá in use at Billefjord School/Billávuona skuvla. The spissá game was designed by teacher Marte Eliassen. Printed with permission. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

2.4. A Descriptive Case Study

Our study focuses on a Sea Sámi boatbuilder’s description of a central tool in his work. This aligns with Cohen et al.’s (2011) explanations of a case study: a case study can be a detailed examination of a small sample or the study of an instance in action. According to Yin (2018), a case study is an empirical method that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-world context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context may not be evident. The contemporary phenomenon we study is the Sea Sámi use of the fanasváhter, mainly represented by the Sea Sámi boatbuilder Hans Oliver’s responses to several interview questions. The real-world context is Sea Sámi boatbuilding. Because the phenomenon is intertwined with its context, there are no clear boundaries between them. Yin (2018) points out that the more your questions seek to explain how or why a social phenomenon works, the more relevant case study research becomes. Our second research question is a ‘how’ question. The analysis provides a description of the phenomenon ‘Sea Sámi use of the fanasváhter’ in the context of ‘Sea Sámi boatbuilding’, viewed from different perspectives. Our study is a descriptive case study.

2.5. Indigenous Versus Western Methodologies in Research

There is a difference between research conducted within an Indigenous context using Western methodologies and research conducted using Indigenous methodologies, which integrate Indigenous voices (Louis, 2007). Indigenous methodologies are ways of thinking about research processes, aiming to ensure that research on Indigenous issues is carried out in a way that is respectful and ethically sound from an Indigenous perspective. In our study, the research focus is on how Sea Sámi use of the fanasváhter can contribute to vocational school mathematics. Different perspectives on how the fanasváhter works are central to our study. To carry out the research in a respectful and ethically sound way, the boatbuilders Hans Oliver and Ove were invited to be co-authors of this article.

2.6. Preparation for the Visit to Mearrasiida

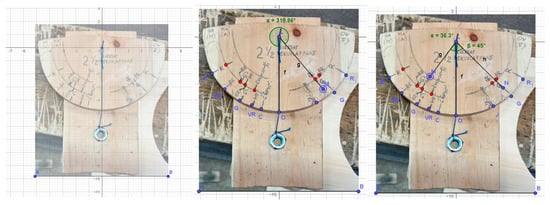

The preparatory lesson was led by the first author. It included sections from Karlsen et al.’s (2023) video, in which the boatbuilder holds the fanasváhter at three different sections of the boat to show how the pendulum moves in accordance with the steepness of the boatboards. The lesson also included the illustrations in Figure 6, where the boatbuilder Ove explains a drawn profile of a boat on the workshop wall. The focus of the lesson was how to create the boat profile.

Figure 6.

(Left) The boatbuilder Ove discusses the fanasváhter with a visitor. (Right) A closer look at details in the photo. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

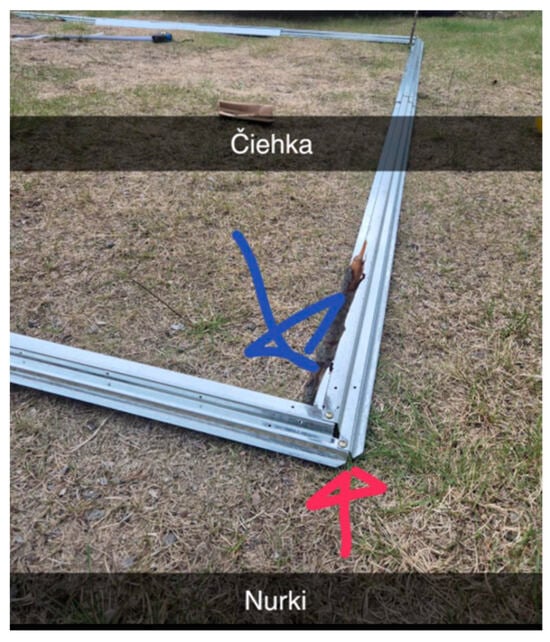

Because ‘angle’ is the mathematical focus, Sámi terms for angle were highlighted. The Sámi mathematics teaching tradition in Norway is largely based on the Norwegian language. There is no Sámi mathematics curriculum, so the textbooks are merely translations from Norwegian. The Norwegian word for ‘angle’ is ‘vinkel’, which is a Norwegianization of the German ‘Winkel’. The word does not offer Norwegian or Sámi students any opportunity to link the term to their previous experiences; it is just an abstract term. The Sámi word for angle is čiehka, which also means ‘internal corner’. The Sámi language distinguishes between internal and external corners; the word nurki refers to an external corner, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Nils Ailo’s illustration of a shed frame’s internal and external angles, čiehka and nurki, respectively. Photo: Nils Ailo Anti.

Anne explained how to use the fanasváhter in creating a boat profile. This explanation was from a traditional mathematical perspective, constructed as a geometrical proof based on knowledge of vertical angles. The approach was abstract and theoretical. From a retrospective perspective, she should have chosen an approach that invited the audience to listen to their intuitive ideas of angles. The proof did not seem to contribute to any deeper understanding.

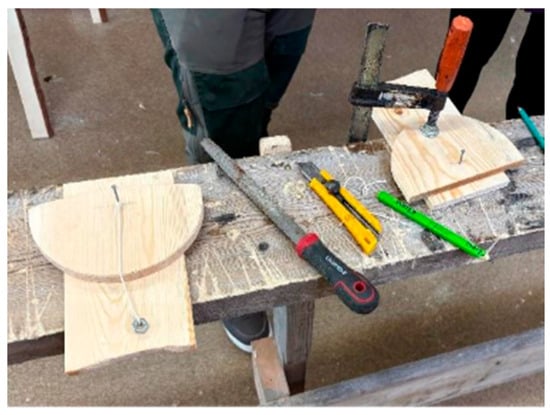

2.7. The Visitors Made Their Own Fanasváhters

Hans Oliver and Ove showed the guests how the fanasváhter works. The váhter in Figure 8 belongs to the nearby school’s new boat, which is 2 ½ rooms in size (2 ½ siessat skuvlafanas—‘2 ½ rooms school boat’). This fanasváhter has three double arches marked with a pen; each double arch represents a scale, as shown in Figure 8. At the top of each double arch, some letters are written. The letters refer to where on the boat the fanasváhter is placed when using the scales; the letters in parentheses indicate the Norwegian translations. The leftmost arch is GA (M) gaskarapmu (the band in the middle, Norwegian: ‘midtrem’), the next one is MA (A) maŋŋerággu (the stern band, stern is ‘akterende’ in Norwegian), and the arch to the right is marked OV (F) ovdarággu (the front band, Norwegian: ‘fremste band’).

Figure 8.

Enlarged detail of the fanasváhter’s semicircle. Detail from Figure 3. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

Hans Oliver and Ove told the names of each boatboard and showed how the marks for each board’s steepness are placed along the scales. The boards are, from top to bottom, respectively: R—riipofiellu (the brim board), BR—badjerapmu (the upper board), GR—gaskarapmu (the middle board), VR—vuollerapmu (the lower board), Č—čoavjefiellu (the board nearest the keel board) and G—giellabordi (the keel board). The boards’ steepness decreases as you move downward toward the bottom of the boat, except that the giellabordi, the keel board in the bottom, is steeper than its predecessor. In Figure 8, the letter G is placed between BR and GR for the front and stern bands, while it is placed between GR and VR for the middle band. We leave the explanation of this detail to curious readers.

Each visitor could make their own fanasváhter, as shown in Figure 9. This provided some insight into how the tool works, because every detail had to be considered during the process. One such detail is the fanasváhter’s curved end; this allows the váhter to reflect the steepness of the boatboards even when they are slightly bent. This detail ensures that the intended boards can achieve precisely the desired steepness; accuracy in steepness is important even though it is not measured in degrees. The curved end is visible at the bottom of the fanasváhter in Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Two SUAS visitors’ fanasváhters under production. Photo: Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

2.8. The Boatbuilder Interview

After reading about and discussing the use of the fanasváhter, the first three authors agreed on five questions for a semi-structured interview with the boatbuilder Hans Oliver. The interview aimed to describe aspects of the boatbuilder’s perspective on the fanasváhter’s usefulness and value. A semi-structured interview was chosen to allow for other additional information to emerge from the boatbuilder. The interview questions were:

- How did you learn about the use of the fanasváhter?

- How do you imagine that schoolchildren or apprentices can see that this is a useful tool?

- What do you think is the value of the váhter, that tool?

- Have you used the fanasváhter for purposes other than boatbuilding? For work outside of boatbuilding?

- Why don’t you use standardized measures? If you used standardized measures instead, could it have made your work easier?

The first author carried out the interview through a phone call. Before the interview, Hans Oliver agreed to be a co-author of this article, and he was prepared for an interview about his use of the fanasváhter. The interview lasted six and a half minutes.

2.9. Data and Analysis

The data consist of an audio recording of an interview with boatbuilder Hans Oliver on 30 June 2025. Supporting materials include Karlsen et al.’s (2023) video about traditional measuring, the Mearrasiida book about boatbuilding (Nilsen, 2021), observations at the Mearrasiida boatbuilding workshop during the visit on 7 March 2025, and the first author’s handwritten notes from communications with Hans Oliver.

The cultural symmetry framework (Meaney et al., 2022) forms the basis of the analysis. Step 1: We describe the cultural knowledge and values related to the fanasváhter and its use, based on the interview with Hans Oliver and the supporting material. Because Hans Oliver is an experienced boatbuilder, we expect the interview data to be particularly useful for the analysis in this step. The Sámi language is also considered to some extent, as aspects of the knowledge may be linked to linguistic terms that are no longer in common use. Step 2: We examine and discuss the use of the fanasváhter from a range of perspectives: Sea Sámi boatbuilding, duodji, Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilding, and Western school mathematics. Because Hans Oliver is a co-author of this article, he has added background information that supports some of the interpretations in the analysis. For each perspective, the use of the fanasváhter is analyzed with respect to whether it shows novelty and usefulness, which, according to Sternberg and Lubart (1999), are required for something to be considered creative. The use of the fanasváhter is also analyzed with respect to the three requirements for being a creative thinker, explained by Csikszentmihalyi (1996). Step 3: We consider how the mathematical understandings, whether they are derived from Sámi mathematical practice or from Western school mathematics, can deepen and enrich the cultural meanings already present in the use of the fanasváhter.

2.10. Representativity

In Step 2, four different cultural practices are chosen as perspectives for the analysis. Sea Sámi boatbuilding and duodji are two obvious perspectives, as boatbuilding is the focus of the paper and duodji is closely related to Sámi boatbuilding. Because Hans Oliver is a co-author of this paper, he represents the main voice of the Sea Sámi boatbuilder perspective. In addition, there are very few Sea Sámi boatbuilders overall. Regarding the duodji perspective, Ove is the main voice, as he is both a duojár and a co-author of this paper. In addition, we chose to include theoretical perspectives from Gunvor Guttorm because she is one of the very few professors in duodji, and she was the first. Regarding the choice of the Norwegian (non-Sámi) perspective, we chose Eldjarn and Godal (1990) because the boatbuilding of Eldjarn et al. (2025) is located in Troms in the north, and their studies of clinker-built boatbuilding are extensive. These three choices are considered highly representative of the three practices.

The perspective of Western school mathematics is chosen because it is based on the first author’s teaching unit about the fanasváhter for pre-service teachers. Even though Anne is a skilled teacher educator, she found herself trapped in the old-school geometry culture. She was also the first to realize that the approach was a classic deductive way of teaching that had very limited value for the audience. Thus, this example could be replaced by a more inductive approach that is based on recent research. We are aware that our choice of Western school mathematics perspective may be open to discussion and that other researchers might choose differently. However, since this teaching unit took place in the fanasváhter project, we decided to include it.

3. Results

This section has three subsections, one devoted to the analysis in each step of cultural symmetry.

3.1. Step 1: Knowledge and Values Related to the Fanasváhter

Hans Oliver says that his boatbuilding follows his heart and is grounded in how he has learned this craft. Regarding the fanasváhter, the principle is that it is based on the force of gravity and a string. According to Meaney et al. (2022), recognizing the importance of the Indigenous language in the cultural symmetry model acknowledges the close relationship between mathematical activity, language, and thought. These relations come to the surface when Hans Oliver says that boatbuilding is based on principles such as that the boat must look vuogas čalbmái, ‘pleasant to the eye’, and that the measures are hui sullii, ‘very roughly’/’very approximately’ (Karlsen et al., 2023). This statement includes the angle measures as well, not only the length measures. Aesthetics are in focus to a higher degree than detailed measuring and following strict rules.

The fanasváhter is used to measure how steep the boatboards should be, “... mihtida man állut fanas fiellut galget leat” (Nilsen, 2021, p. 15). Hans Oliver uses the Sámi word álli for the Norwegian legg (a term used in coastal boatbuilder language for slope). The legg has to be equal on both sides. The legg influences how the boat “swallows” water and releases it behind the boat; the idea is to achieve a boat that is easy to row (Hans Oliver, personal communication, 7 March 2025, author’s translation). Each time you make a new boat, you also make a new fanasváhter, based on a few basic rules. When you use the fanasváhter to measure how steep the boatboards should be, you do not come up with any number that refers to the steepness; you do not measure the steepness in degrees.

In the interview, Hans Oliver said he did not remember how he learned about the fanasváhter. His profession is carpentry. He explained that in the past, plumb bobs were used when you started as a carpenter. You used all kinds of plumb bobs before modern tools appeared, and in a variety of situations. So, the fanasváhter, “... is very simple when you can see it like this. Two seconds, and it will hang like this, and then you know... and you know what it is about” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025, author’s translation). His explanation is an example of how a skilled carpenter replies when asked to explain his know-how (the máhttit part of knowledge) in words. He understands intuitively how the string will hang due to his experience with the force of gravity, so his reply is that it is easy to see. This is what we show in Figure 4. When the first author commented that the relations between the fanasváhter and school mathematics are interesting, Hans Oliver replied, “A piece of wood, some string, and a nut as a plumb. That is mathematics” (Hans Oliver, personal communication, 1 December 2025).

His knowledge of how the fanasváhter works is experience-based, grounded in his carpentry knowledge of using a variety of plumb bobs. This way of knowing how to use plumb bobs represents the máhttit part of knowledge, while the experience-based knowledge of how it works corresponds to the diehtit part of knowledge, as explained by Guttorm (2011a). Hans Oliver also referred to those who built telegraph poles and telephone poles after World War II. Some men lifted, while one man stood with a string, perhaps 100 m away. A plumb hung from the string, and the man shouted directions to the others about how to move the pole.

Regarding question 2, how he imagines that schoolchildren or apprentices can see the fanasváhter as a useful tool, Hans Oliver provides a clear reply. “They see it immediately, in five seconds... They see that quickly; it is so very logical...” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025, author’s translation). This is how he experienced apprentices encountering the fanasváhter. However, he added that they were all grown-ups. Regarding the value of the fanasváhter, he said that it is useful for building boats.

Hans Oliver clearly replied that standardized measures would not make his job easier in clinker building. They would only cause him problems, because “... then you will always follow the standardized measures, try to press the boards and planks to be accurate. And that is just nonsense” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025, author’s translation). He believed in the old boatbuilders; he had read that they used to say that “it becomes just what it becomes” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025, author’s translation)1.

The interview was semi-structured, so it was open to more than just replies to the given questions. Anne remembered Hans Oliver’s father as well-respected and knowledgeable, so at the end of the interview, she asked whether his father had used the fanasváhter when building boats. Hans Oliver replied that his father used to repair boats and that he was skilled at doing so, but he did not need any váhter for that purpose. He continued:

The postwar generation, they repaired. They never built, because they never had time to start building boats. They had more than enough to do with rebuilding... Their, their whole generation, and far into the next, had more than enough to raise, to rebuild Troms and Finnmark... They worked themselves to death from that.(Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025)

Hans Oliver said that all the rebuilding after World War II was extremely time-consuming and that the Norwegian state provided money for new boats to replace the large fleet of small boats that had existed before the war. So, the state supported the production of boats further south, where boats were already being produced. Down in Rana (in Nordland), they had standardized boats, which were built and sent northwards so that people could have boats quickly. “Because they [the population in Finnmark and North Troms] had to build houses and barns and quays, … and roads, … and all infrastructure. Everyone had to build, so there was no time for building fun things like boats” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025). After a short pause, he added, “Therefore, the boat culture also disappeared with Nazism” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025).

3.2. Step 2: The Use of the Fanasváhter from Different Perspectives

In this section we analyze the use of the fanasváhter from four perspectives rooted in four different domains, all of which are cultural practices: Sea Sámi boatbuilding, duodji, non-Sámi Norwegian boatbuilding, and Western school mathematics. Sternberg and Lubart’s (1999) two requirements for creativity are central to the analysis, in addition to Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) three requirements for being a creative thinker.

3.2.1. A Sea Sámi Boatbuilding Perspective

The interview showed, as expected, that Hans Oliver knows the domain of boatbuilding. The way he talks about repairing boats versus building new boats shows that he values novelty, which is one of the requirements for creativity set up by Sternberg and Lubart (1999). Hans Oliver explained how the rebuilding after World War II forced people to do the opposite of being creative; they were prevented from pursuing original and new ideas.

Hans Oliver points out that each new boat gets its own fanasváhter, like the one in Figure 8 and those on the wall in Figure 6. In each boat, the angles may vary slightly. In one boat, you may know that some of the angles must be a bit larger than the marks show, for instance. When the Mearrasiida boatbuilders started making the skuvlafanas, the local school’s boat, they used the previous boat’s fanasváhter as a model, but they made slight adjustments. They wanted to decrease the steepness of the lower boards to create a wider boat. This would result in a more stable boat, since it was intended for use by schoolchildren. Because they valued the new boat’s usefulness, they searched for new ideas in order to create a boat that would be as useful as possible. The outcome was a novel boat that is useful for its purpose; building this boat aligns with the requirements for creativity provided by Sternberg and Lubart (1999).

The fanasváhter is identifiable as a specialized tool, characterized by its specific utility and purpose in the boatbuilding process. Its primary function is to ensure that the álli (Norwegian: legg), the board steepness, on both sides of the vessel is identical. In this way, the fanasváhter contributes to the boat’s structural symmetry and seaworthiness. This is part of the fanasdahkki’s deep knowledge of the domain.

As Hans Oliver explained in the interview, “So, it is useful for its purpose. Useful for its purpose, plain and simple” (Hans Oliver, personal interview, 30 June 2025, author’s translation). This statement implies that the tool’s primary application lies in shaping and aligning the álli (board steepness or legg) of the boat. The boatbuilders did not refer to the steepness of the boatboards in terms of any exact number of degrees. Hans Oliver pointed out that deciding how much they will change the boat’s álli or legg when making a new boat is something that is impossible to explain in words. This is an example of the máhttit part of boatbuilder knowledge, as described by Guttorm (2011a). In Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) terms, this is an example of why knowledge about the domain is necessary for generating creative ideas. We conclude that from a Sea Sámi boatbuilder perspective, the fanasváhter is a useful tool for creating new boats, depending on the purpose of the boat. For Hans Oliver, the construction of a fanasváhter is not incidental but arises from necessity, directly tied to its intended function. The tool itself is useful, which satisfies one of the criteria provided by Sternberg and Lubart (1999). When it is used in creating boats with new shapes for new purposes, it fulfills the second criterion for creativity.

During the work with the analysis, Hans Oliver (personal communication, 25 September 2025) referred to an old boat that he had recently seen. The boat was built in 1947, and it was partly destroyed. This is an example of old Porsanger boats, a style that was built before World War II. The boat was made for use in the very shallow areas of this fjord. “The ebb zone can be up to 600 m, so people built boats that could float in ankle-deep water, goartil čázis, which means a water depth of one hand span. These boats may be called tide models; the tidewater determined which boats you ordered from the fanasdahkki.” (Hans Oliver, personal communication, 25 September 2025, author’s translation). A boat like this is definitely useful, and the idea of boats like this was novel when they first appeared. Thus, the creation of this Porsanger boat is an example of what Sternberg and Lubart (1999) call creativity.

3.2.2. A Duodji Perspective

When Ove learned to make a fanasváhter, he copied what Hans Oliver had made. After a while, he made some adjustments and found his fanasváhter to be an outcome of his personal style, adapted to his understanding of duodji and his sense of form. He explains that it is difficult to copy another person’s duodji because within the given norms of duodji, everyone has their own understanding of how to do it. Two individuals have different eyes, and therefore they also have different perceptions of what is pleasant to their eyes. Knowledge (diehtu) of the given norms is necessary before you can (máhttit) develop your own style. This shows the need for knowledge of the domain, which Csikszentmihalyi (1996) points out as important. The development of personal style is an example of a search for originality, which is one of the two requirements for creativity set up by Sternberg and Lubart (1999). Ove is a boatbuilder as well as a duojár, and we find that the duodji perspective is, to a large extent, similar to the Sea Sámi boatbuilder perspective. Thus, we find no clear way to distinguish between the two perspectives on the use of the fanasváhter.

3.2.3. A Norwegian (Non-Sámi) Boatbuilder Perspective

The perspective presented by Eldjarn and Godal (1990) is chosen for this part of the analysis because they describe the building of a nordlandsbåt. Their older informants emphasized that the difficulty was not in making a boat, but in making it a nordlandsbåt: there is more to building a nordlandsbåt than merely following drawings and instructions. Like the Sea Sámi boatbuilders, they are very aware that the steepness of each board in different parts of the boat is crucial for how the boat moves in the sea and how much force is required by those who row the boat. This tradition aligns with Csikszentmihalyi’s (1996) point that, to be an original (and creative) thinker, one needs thorough knowledge of the domain.

Old traditional Norwegian boatbuilders used body measurements, and clinker building is a common old tradition. Mikalsen (1987) explains that hand span is an old measurement that was used in clinker building. He uses the verb in past tense. Hans Oliver explains how goartil (English: hand span) still is used in Sea Sámi boatbuilding (Karlsen et al., 2023). Eldjarn and Godal (1990) describe the leggfjøl (steepness plank), a tool for controlling the steepness (legg) of the boatboards. They also refer to other names for this tool: loddfjøl (plumb plank), båtlodd (boat plumb), and leggpasser (steepness compass). The leggfjøl is a circular plank with two short feet and with a plumb hanging from a string attached to the circle’s center. The plank has a baseline represented by the two legs that the plank is standing on while in use, like the tool presented in Figure 10. The plumb hangs 90° to this baseline when the baseline is horizontal. Each board’s inclination angle is represented by a mark on the string’s periphery. The description continues: “The keel board must lie down more in the middle, and it must stand up more in the rear end than in the front. In the middle it must lie 41°, in the front 46°, and in the rear end 48°” (Eldjarn & Godal, 1990, p. 39). The Norwegian Hardraade Vikingskipforening (Hardraade, 2024) uses the term loddmåler (plumb measurer), as shown in Figure 10, when building a hybrid replica of a 20 m long Viking ship from 998 AD. On this tool, every ten degrees is clearly marked.

Figure 10.

Loddmåler. Screenshot from Norwegian Broadcasting nrk1 Kveldsnytt 26 August 2025. Reprinted with permission from Hardraade.

The leggfjøl is similar to the fanasváhter, but at first glance the two tools may appear slightly different because their shapes differ. The leggfjøl has two legs, as does the loddmåler shown in Figure 10. These two legs serve the same function as the curved end of the fanasváhter. Eldjarn and Godal’s (1990) reference to exact angles contrasts with the Mearrasiida way of using the fanasváhter, where no exact size of any angle is referred to at all. So, while the Sea Sámi use of the fanasváhter focuses on non-standardized measures to make boats for different purposes, Norwegian boatbuilders concentrate on standardized measures because they build copies of standardized boats. The aim of the Norwegian boatbuilding described by Eldjarn and Godal (1990) is not to develop new ideas or new ways of doing things. This means that the work is not creative according to the requirements set up by Sternberg and Lubart (1999). We conclude that, from this Norwegian boatbuilder’s perspective, the leggfjøl is a useful tool for creating copies of previously built boats.

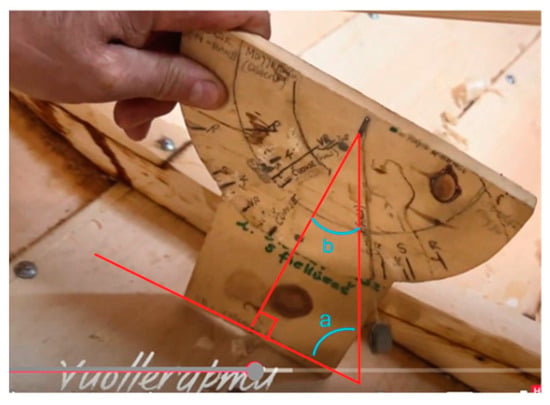

3.2.4. A Western School Mathematics Perspective

Anne’s lecture before the visit to Mearrasiida is an example of a Western school mathematics approach by a well-meaning teacher educator. Through the lecture she experienced how easy it is for someone educated within the Western school mathematics teaching tradition to be trapped in it when teaching about something new. This is an example of Weigand et al.’s (2025) point that most of the contemporary secondary geometry teaching concerns proofs. After watching the video, the fanasváhter was introduced as a tool to achieve the correct boat profile or to achieve the desired steepness of each board. The presentation then turned to the picture in Figure 11, which is a screenshot from Karlsen et al.’s (2023) video, where a triangle has been added. The task given here is to describe the angles a and b. From this perspective, one can prove that the sum of angles a and b is 90°, so as angle a increases, angle b decreases correspondingly.

Figure 11.

Illustration from the lecture. Screenshot and drawing by Anne Birgitte Fyhn.

Here the fanasváhter is reduced to merely a tool for explaining certain mathematical relations, and the mathematics is introduced before the learners have had a closer look at the actual cultural practice. This is what Meaney et al. (2022) warned against when they developed the framework of cultural symmetry. To explain the relations between the angles in Figure 11, one needs to know enough mathematics to recognize that the point is to use the rule stating that the sum of the internal angles of a triangle equals 180°. There is no focus on novelty at all, which means that this perspective does not fulfill the requirements for creativity by Sternberg and Lubart (1999). This approach also does not build on the students’ intuitive ideas. They were not expected to come up with any new ideas; the aim was to guide them toward recognizing formal relations between angles a and b. Figure 11 does not support an experience-based understanding of what happens to a plumb that is hanging from a string, as Hans Oliver described. While his explanation was experience-based, like Sámi traditional knowledge is, Anne’s approach was deductive, as explained by Russell (2004). We conclude that from this Western school mathematics perspective, there is a risk that mathematics may suppress culture, but also that the fanasváhter is a tool rich in possibilities for demonstrating geometrical proofs.

3.3. Step 3: How Mathematical Understandings Can Contribute

This section presents how mathematical understandings, whether they are derived from Sámi cultural practice or from Western school mathematics, can deepen and enrich the cultural meanings already present. The analysis reveals (a) no differences between the values of the domains duodji and Sea Sámi boatbuilding, and (b) that the three domains (i) Sea Sámi boatbuilding, (ii) Norwegian (non-Sámi) traditional boatbuilding, and (iii) Western school mathematics rely on different values. Those who practice Sea Sámi boatbuilding as well as duodji, value sullii, ‘roughly’ in combination with the final product’s functionality and vuogas čalbmái, ‘pleasant to the eye’. Vuogas čalbmái means that the eye is assessing the final product, while álli and the fanasváhter serve as supervisors along the way toward the finished product. In contrast, within Norwegian (non-Sámi) traditional boatbuilding and Western school mathematics, standardized and accurate measurements are valued. Awareness of this difference may cause deeper understanding of the knowledge embedded in the fanasváhter. This difference in values explains the situation that the boatbuilder Hans Oliver experiences, in which the use of standardized measures causes him nothing but trouble, while such measures are necessary for Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilders. Both traditional Sea Sámi and traditional Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilding result in solid boats that individuals can row and use for fishing.

The two Sámi mathematical understandings of the fanasváhter are located in what Lakoff and Núñez (2000) call NCS, the Natural Continuous Space. According to Hans Oliver, the fanasváhter principle involves a string and a plumb and the existence of gravity. This understanding is based on each individual boatbuilder’s intuitive sense of how much each boatboard should be tilted in relation to the string’s direction. From a Sea Sámi boatbuilding perspective, this is not about any angle measured in degrees. However, from a Norwegian boatbuilding perspective, the exact angle measures are a useful tool for making exact copies of old boats. We do not see that Western school mathematics contributes to the understanding of how the fanasváhter works. Traditional boatbuilding, regardless of whether it is Sámi or Norwegian (non-Sámi), is an experience-based handicraft, while the deductive approach of Western mathematics that is common in geometry is an inheritance from Pythagoras (Russell, 2004). We conclude that Sámi mathematical understanding can contribute to the cultural meanings embedded in the use of the fanasváhter by explicitly articulating Sámi mathematical understanding, which highlights work in the NCS, the inclusion of sullii, and assessment by individual vuogas čalbmái.

3.4. Summing up the Analysis

The analysis is a three-step study of the use of the fanasváhter, based on the framework of cultural symmetry (Meaney et al., 2022). Step 1: The knowledge related to the fanasváhter includes three central terms that show relations between Indigenous language, activity, and thought: álli, vuogas čalbmái, and sullii. Álli (Norwegian: legg) refers to the steepness of the boatboards, that is, how aslant each board should be in different sections of the boat. Vuogas čalbmái, ‘pleasant to the eye’, refers to the aesthetics; the assessment of the final product is that the boat must appear pleasant to the eye. Therefore, the measures cannot be forced to fit a detailed description; the measures will be hui sullii, ‘very roughly’, as planned. Because every boatbuilder has their own eyes, they do not experience vuogas čalbmái identically. In a duodji context, Guttorm (2013) explains this through the example of a duojár making a guksi, a cup or ladle: “[t]he shape of the guksi is closely tied to the duojár’s experience with the guksi” (Guttorm, 2013, p. 39). In the context of boatbuilding, the fanasdahkki shapes the boat according to his or her own experiences with boatbuilding.

Step 2: Different perspectives on how and why the fanasváhter works and how creativity is part of using this tool. Table 1 presents an overview of these findings, summed up as five different values that are embedded in the use of the fanasváhter. Non-standardized units of measuring and thorough knowledge of the domain (diehtit as well as máhttit) represent knowledge of how and why the fanasváhter works. The last four values: thorough knowledge (diehtit and máhttit) of the domain, novelty, and usefulness represent creativity.

Table 1.

Summing up the analysis.

The Sea Sámi boatbuilder’s use of the fanasváhter does not refer to any angle measures that are represented by numbers; their use of the fanasváhter takes place in NCS, the Natural Continuous Space, as explained by Lakoff and Núñez (2000). This contrasts with Eldjarn and Godal’s (1990) reference to angles measured in degrees when using the similar leggfjøl. In their boatbuilding domain the use of the leggfjøl takes place within SSP, the Space as a Set-of-Points. Moreover, there is reason to believe that boatbuilders used the fanasváhter before the 17th century and that this practice developed independently of measuring sticks.

Csikszentmihalyi (1996) points to three conditions that are necessary to be creative. Regarding boatbuilding, a boatbuilder must have knowledge about boats, boatbuilding, and the use of these boats. The second condition is to be interested in developing new ideas related to boatbuilding. The third condition is to have the ability to discard trash thoughts and avoid being stranded in dead ends. It turns out that the first condition is fulfilled for all four practices. From the Sea Sámi boatbuilder perspective, the second condition is also fulfilled. The domain here is Sea Sámi boatbuilding. From a Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilder perspective, the domain is making boats in accordance with a detailed description. Here, the second condition is not fulfilled, because there is no need for new ideas in replication, and mathematics functions merely as a practical tool. From a Western school mathematics perspective, the domain is mathematical tools and examples of mathematics. There is no need for new ideas, and thus the second condition is not fulfilled. Regarding the third condition, we could not find any information in any of the practices.

Creativity is the ability to produce work that is both novel (i.e., original and unexpected) and also appropriate, useful, and adaptive to the task constraints (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). According to their outline, the idea of an original and special boat that can be considered novel but useless is not a creative idea. Likewise, the idea of a boat that seems very useful but is neither unique nor original is not a creative idea.

Regarding Step 3: Sea Sámi boatbuilding values non-standardized measures that are hui sullii (very aproximate), while Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilding and Western school mathematics value standardized and exact measures. Sea Sámi boatbuilding relies on NCS mathematics, while Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilding and Western school mathematics rely on SSP mathematics. This means that while the first perspective value mathematical reasoning within NCS, the latter two value mathematical reasoning within SSP. The mathematical knowledge that is represented by a number line, like for instance angles measured in degrees, belongs to the SSP knowledge. On the other hand, knowledge that is not represented by numbers belongs to NCS. Both approaches result in appropriate and useful boats; there is no reason to claim that one approach is better than the other.

4. Discussion

The first research question in this study is: What is the knowledge embedded in the use of the fanasváhter? The second research question in this study is: How does creativity come to the surface through different perspectives on the use of the fanasváhter? The analysis reveals five values that are embedded in the Sea Sámi boatbuilder’s use of the fanasváhter: non-standardized units of measuring, thorough knowledge of the domain of boatbuilding regarding the máhttit and the diehtit aspects of knowledge, novelty, and usefulness. The Sea Sámi use of the fanasváhter, without referring to any standardized units of measuring, for instance by using degrees, shows how non-standardized units of measuring are valued. In addition, Fyhn et al. (2024a) show examples of how a Sea Sámi boatbuilder values non-standardized units of length measurment. Non-standardized units of measuring are not valued in Norwegian (non-Sámi) boatbuilding nor in Western school mathematics. Novelty is valued in the Sea Sámi regeneration of traditional boatbuilding, while it is not valued in Norwegian (non-Sámi) copying of traditional old boats. Western (traditional) school mathematics does not need novelty, but some studies, like the one by Haavold and Sriraman (2021), open up for new approaches. Thorough knowledge of the máhttu part of the domain (the know-how, or practical knowledge) is valued in both ways of boatbuilding, but this is not necessary in Western school mathematics.

In this section, we discuss educational perspectives on the use of the fanasváhter based on the findings from the analysis.

4.1. Angles in Spatial Geometry Education

From a mathematics education perspective, the fanasváhter is a tool that is used in three-dimensional spatial geometry. The Greek word geometry is composed of the two words ‘ge’ (earth, land) and ‘metron’ (measure). The term ‘geometry’ is still used in mathematics curricula worldwide. The longitudinal research project Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) (OECD-PISA, 1999), chose from its beginning to replace the term ‘geometry’ with ‘space and shape’. Still, the term ‘geometry’ is well established, and more than 25 years of using the term ‘space and shape’ has not caused ‘geometry’ to disappear from Norwegian mathematics curricula. In Norway, the geometry component of the compulsory school curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2019) mainly concerns geometrical shapes, while the spatial aspect of geometry is very limited. The importance of spatial geometry, but also the difficulties in this area, has long been emphasized (Weigand et al., 2025). They point to the need for good strategies for developing spatial thinking.

The educational challenges with teaching spatial geometry may be the reason why work with ‘angles’ in compulsory school is primarily related to the properties of geometrical figures. The basic concepts of point, line, ray, and angle are not explicitly mentioned in the early years’ mathematics in the Norwegian curriculum. Concepts such as the steepness of a slope or changes in direction are not included in compulsory school geometry.

According to Lakoff and Núñez (2000), there are concepts of number that are not geometric, yet the number line is one of the most central concepts in mathematics. Trigonometry would not exist without the number line. “The fundamental metaphor that defines the field of trigonometry conceptualizes angles as numbers” (Lakoff & Núñez, 2000, p. 387). However, angles themselves are nonnumerical, as the fanasváhter shows. Sea Sámi boatbuilders have shown that to compare angles, or to copy an angle, you do not need any angle measurement in degrees. This aligns with Freudenthal’s (1983) point about comparing angles before the teacher introduces measuring angles.

4.2. Insight—Not Limited to the Outcome of Thorough Knowledge

According to Csikszentmihalyi (1996), there are three requirements for being a creative thinker. The first one is to have thorough knowledge of the domain. This is one of the requirements chosen for this article’s creativity criteria. To be interested in coming up with something new is number two. In the field of mathematics education, Haavold and Sriraman (2021) investigated creativity in problem solving, with a focus on insight. They consider insight to be a perceptual and conceptual restructuring of a problem in a productive way. From their perspective, insight is an outcome of thorough knowledge but also the result of unconscious processes that come about after entering a dead-end street.