Abstract

The growing prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among students highlights the urgent need for school-based strategies that promote psychological well-being and timely intervention. This study explores the use of artificial intelligence (AI) as a scalable and data-driven tool to support institutional mental health initiatives in higher education. Using synthetic and real datasets derived from validated psychometric instruments (the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)), we trained and evaluated 32 deep neural network architectures for the early detection of emotional distress. Optimized three- and four-layer dense models achieved classification accuracies exceeding 95%, demonstrating the feasibility of deploying AI-based screening tools in educational settings. Beyond prediction, this approach can support counselors and educators in identifying at-risk students and informing proactive, school-based interventions to improve mental health and resilience in post-pandemic academic environments.

1. Introduction

Mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and stress have significantly increased in prevalence over the past decade, raising major concerns among public health institutions worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022). In Mexico, the 2021 National Self-Reported Wellbeing Survey reported that 15.4% of the adult population exhibits symptoms of depression (19.5% among women), 19.3% report severe anxiety symptoms, and 31.3% experience anxiety to some degree. It is estimated that 3.6 million adults live with depression, reflecting an upward trend, particularly for anxiety and depression (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2021).

Early detection is crucial, and standardized instruments such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Levant & Shapiro, 2002), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1996), and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) (Cohen et al., 1983) have proven reliable for assessing these conditions. These tools are widely used in clinical and research contexts; however, their length and reliance on manual scoring can reduce completion rates and introduce variability or diagnostic errors (Bradford et al., 2024; Tutun et al., 2023). Artificial intelligence (AI) offers a promising solution by automating assessment and interpretation. While AI has already demonstrated strong performance in oncology (Hosny et al., 2018), neurology (Patel et al., 2021), and dermatology (Liopyris et al., 2022), its adoption in mental health remains limited, despite clear opportunities to improve diagnostic accuracy, reduce professional workload, and expand access to timely care (Lee et al., 2021).

Recent studies confirm the potential of machine learning in this domain. Shatte et al. reported that algorithms can predict psychological states with high accuracy using questionnaire data, clinical records, and digital behaviors (Shatte et al., 2019). Yoo et al. (2024) achieved AUC values above 0.90 when classifying anxiety and depression symptoms using neural networks. A wide range of models, including Convolutional Neural Networks, Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and Extreme Learning Machines, have been tested for mental health prediction (Madububambachu et al., 2024). For instance, Sun et al. developed an electrodermal-activity-based deep learning system that detected depression severity in university students with an accuracy above 92% (Sun et al., 2025). These findings highlight the importance of architectural design and hyperparameter selection in maximizing classification performance.

University students represent a particularly vulnerable group, as the transition to higher education coincides with critical phases of psychological, social, and biological development. Without timely intervention, emerging conditions may evolve into chronic, treatment-resistant illnesses associated with comorbidities, academic failure, and a reduced quality of life (McGorry et al., 2011). Recent evidence indicates that young people, especially women, face higher rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm than previous generations (Duffy, 2023). In a cross-national study of 21 countries, including Mexico, 20.3% of university students met the diagnostic criteria for at least one mental disorder, yet only 16.4% had received treatment in the past year (Auerbach et al., 2016). Given the limited availability of mental health specialists, early identification of at-risk students is essential.

To address this need, we propose an intelligent system for detecting anxiety, depression, and stress among university students. The system is based on artificial neural networks trained using validated psychometric scales (BAI, BDI, and PSS-14). Exhaustive experiments were conducted to determine optimal architectures and hyperparameters, and performance was evaluated using datasets of varying sizes. The results demonstrate that appropriate architectural selection enables classification accuracy of up to 95%, confirming the feasibility of AI-based support tools for mental health in academic contexts.

Objectives and Research Questions

Main Objective

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the feasibility and performance of deep learning-based models as early screening tools for anxiety, depression, and stress among university students using validated psychometric instruments (BAI, BDI, and PSS-14).

Specific Objectives

This research aims to:

- Systematically evaluate the impact of neural network architectural design (number of layers, neurons per layer, and training epochs) on classification performance for mental health risk detection.

- Assess the transferability and generalization capability of models trained with synthetic data when applied to real university student datasets.

- Determine whether optimized dense neural networks can achieve classification accuracy ≥ 95%, suitable for deployment in educational wellbeing and early intervention contexts.

- Identify the optimal architecture–hyperparameter configuration that balances model complexity, training efficiency, and predictive performance.

Research Questions

This study addresses the following research questions:

- RQ1:

- Can deep neural networks accurately classify severity levels of anxiety, depression, and stress based solely on standardized psychometric scale scores from BAI, BDI, and PSS-14?

- RQ2:

- How do architectural design choices (layer depth, neuron configuration) and training parameters (epochs, dataset size) influence classification accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score?

- RQ3:

- To what extent are models trained with synthetic datasets transferable and applicable to real-world university student data without significant performance degradation?

Hypotheses

Based on existing literature and preliminary experiments, we hypothesize that:

H1:

Dense neural network architectures with 3–4 hidden layers and appropriate neuron configurations (e.g., 128–64–16, 64–32–16–4) will achieve classification accuracy exceeding 95% on mental health risk detection tasks.

H2:

Training models with 200 epochs will yield superior and more stable performance compared to 100 epochs across all evaluated architectures.

H3:

Models pre-trained on synthetic data will maintain high performance (≥90% accuracy) when validated with real student data, demonstrating effective transferability.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 describes the methodology and network configurations; Section 3 presents the experimental results; Section 4 discusses the findings, implications, and limitations; and Section 5 concludes with the main contributions and directions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

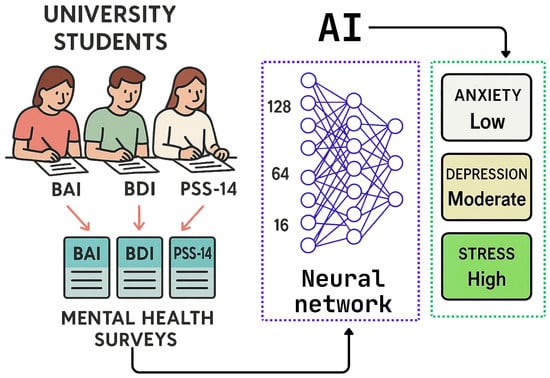

This section describes the procedure used to predict symptoms associated with mental health risks, specifically stress, depression, and anxiety, through the development and application of an artificial intelligence system designed to detect at-risk university students based on their psychological assessment score, as shown in Figure 1, in the first stage, synthetic data obtained from the BAI, BDI, and PSS14 scales are used to train a neural network and quantify levels of anxiety, depression, and stress. In the second stage, these same scales are administered to a group of students, allowing a comparison between the results obtained from synthetic data and those derived from real data.

Figure 1.

Methodology used to evaluate the risk of health disorders in university students: data obtained from the BAI, BDI, and PSS-14 surveys are processed by a neural network that determines levels of anxiety, depression, and stress.

2.1. Data Set

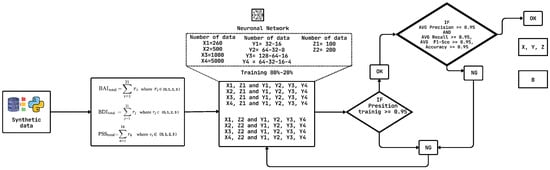

The first dataset was generated synthetically using Python (https://www.python.org/, accessed on 14 October 2025). Different scenarios were created by varying the number of simulated students (X), each of whom completed three psychological scales: BAI, BDI, and PSS-14. In addition, the number of layers (Y) and the number of training epochs (Z) were varied, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology used for selecting the best architectures with the synthetic dataset.

The second dataset was obtained from real students who completed the three questionnaires (BAI, BDI, and PSS-14). The participants were randomly selected from the University, following the procedures of the university’s ethics committee.

2.2. Architecture Selection

Selecting the optimal architecture and hyperparameters of a neural network remains a critical and challenging task in machine learning. Model performance is highly sensitive to design choices such as the number of layers, number of neurons per layer, learning rate, batch size, and activation functions. These decisions are often made through trial and error, grid search, or heuristic approaches, which can be computationally expensive and may not guarantee optimal results. In prediction tasks involving real-world data, which can be noisy or limited, improper tuning may lead to overfitting, underfitting, or poor generalization. Despite ongoing research, no universal method currently exists for selecting architectures and hyperparameters that ensures optimal performance across different datasets.

In this study, the architecture selection process was divided into two stages. In the first stage, several neural network configurations were tested using the synthetic dataset, which allowed filtering out architectures with poor performance. The neural network received three input features: stress level, anxiety score, and depression score. A total of 32 architectures were tested, resulting from the combination of the variables and values shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables modified for architecture testing.

Python was used to train the neural networks. Within this framework, the TrainModel function was implemented to build and train a neural network that classifies questionnaire responses into four severity levels (0, 1, 2, or 3). The model consists of four dense layers: the first three use ReLU activation functions with 64, 32, and 8 neurons, respectively, while the final layer uses a softmax activation function to classify the input into four categories. The Adam optimizer was employed together with the sparse_categorical_crossentropy loss function. Training was performed for either 100 or 200 epochs, using 80% of the data for training and validation.

The creation of multiple models with variations in epochs, number of participants, number of layers, and number of neurons per layer enabled the evaluation of accuracy and training loss. Extensive testing across these combinations identified promising architectures based on precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy. The complete selection process is summarized in Figure 2.

Architectures meeting the following criteria were retained: training accuracy greater than or equal to 95% and training loss less than or equal to 5%. Only those networks with evaluation metrics (Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy) above 95% were selected. A total of 32 architectures were built and assessed using this methodology.

The surviving architectures from stage one (Figure 2) were then trained and evaluated again using real data. In this second stage, the network processed data retrieved from an external database containing the student responses, and the same performance metrics were re-evaluated as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Methodology used for selecting the best architectures with the real dataset.

3. Results

This section reports the results of the neural networks obtained by systematically varying their architectures and conducting exhaustive tests on the two proposed datasets.

3.1. Results with Synthetic Data

Synthetic data were generated for the BAI, BDI, and PSS-14 questionnaires. For each dataset, 80% of the data were used for training and 20% for validation. To evaluate the proposed intelligent system, 32 neural network architectures were initially developed and trained using this synthetic dataset.

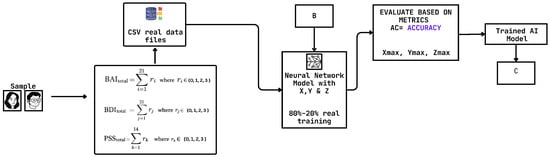

The primary performance metric was training accuracy, which was required to reach at least 95%. The initial experiments were conducted with 100 epochs for each questionnaire, and the resulting accuracy curves showed similar values to those obtained with 200 epochs. Therefore, in the following analysis, we focus mainly on the accuracy graphs generated with 200 epochs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Accuracy for the BAI questionnaire, applied to 260 students with a 200-epoch architecture. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

3.1.1. Training and Validation Results

- (A)

- BAI questionnaireFor the BAI questionnaire, the training and validation results are presented in Figure 4. The three-layer architecture (128-64-16) in Figure 4a reaches stability after 50 epochs. In Figure 4b, with the same number of students (260) but a two-layer architecture (32-16), stability is achieved after 150 epochs. Figure 4c presents the four-layer architecture (64-32-16-4), where training accuracy reaches 90% and validation accuracy 100%, both stabilizing after 100 epochs. Finally, Figure 4d illustrates the three-layer architecture (64-32-8), where both training and validation accuracies are close to 100% with stability reached after 100 epochs.

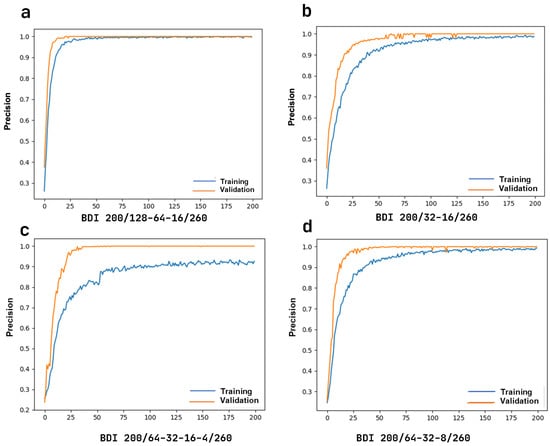

- (B)

- BDI questionnaireThe accuracy results for the BDI questionnaire are shown in Figure 5. The three-layer architecture (128-64-16) in Figure 5a reached stability in both training and validation after 50 epochs. In contrast, the two-layer architecture (32-16), illustrated in Figure 5b,c, achieved stability in validation after 75 epochs and in training after 125 epochs. The four-layer architecture in Figure 5d showed slight instability between 50 and 75 epochs but stabilized after 150 epochs.

Figure 5. Accuracy for the BDI questionnaire, applied to 260 students with a 200-epoch architecture. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d)Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

Figure 5. Accuracy for the BDI questionnaire, applied to 260 students with a 200-epoch architecture. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d)Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes. - (C)

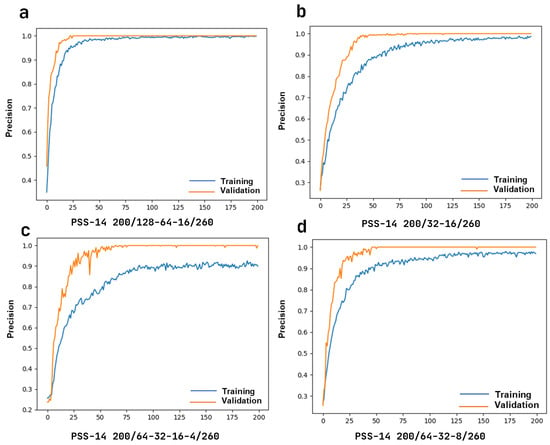

- PSS-14 questionnaireFigure 6 summarizes the results for the PSS-14 questionnaire. In general, the evaluated architectures showed similar behavior to those used for the other questionnaires, achieving stable and high accuracy in both training and validation after 100 to 150 epochs.

Figure 6. Accuracy for the PSS-14 questionnaire, applied to 260 students with a 200-epoch architecture. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

Figure 6. Accuracy for the PSS-14 questionnaire, applied to 260 students with a 200-epoch architecture. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

3.1.2. Evaluation of Different Architectures

- (A)

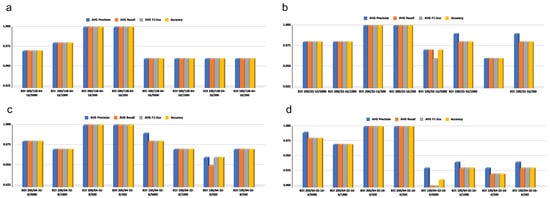

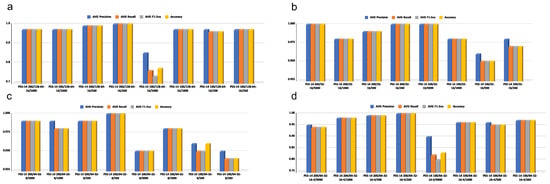

- BAI architecturesFigure 7 presents the evaluation of different architectures applied to the BAI questionnaire, varying the number of data points (260, 500, 1000, and 5000) and training epochs (100 and 200). The top-performing architectures were:

Figure 7. Evaluation of architectures for BAI using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes. (d) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes.

Figure 7. Evaluation of architectures for BAI using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes. (d) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes.- 128-64-16/260 data points/200 epochs, which achieved 1.0 in precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy.

- 64-32-16-4/260 data points/200 epochs, which also achieved 1.0 in all four metrics.

- 64-32-8/260 data points/200 epochs, which showed similarly optimal performance across all metrics.

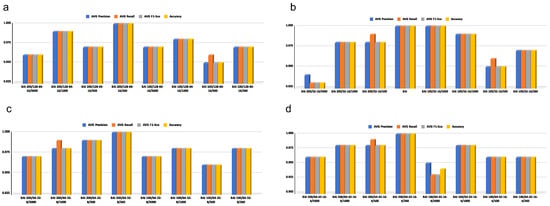

Figure 8 and Figure 9 present comparable results for the BDI and PSS-14 questionnaires, confirming that the 128-64-16 architecture with 260 data points and 200 epochs consistently outperformed the others, reaching perfect values (1.0) for all metrics. Figure 8. Evaluation of architectures for BDI using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

Figure 8. Evaluation of architectures for BDI using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes. Figure 9. Evaluation of architectures for PSS-14 using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes.

Figure 9. Evaluation of architectures for PSS-14 using synthetic data. Metrics include Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy, with the following sample sizes: 260, 500, 1000, and 5000, using 8 architectures. (a) Three layers with 128, 64, and 16 nodes. (b) Two layers with 32 and 16 nodes. (c) Four layers with 64, 32, 16, and 4 nodes. (d) Three layers with 64, 32, and 8 nodes. - (B)

- BDI architecturesFigure 8 shows the impact of the number of epochs on the performance metrics for different architectures. The 128-64-16 architecture (Figure 8a) reached perfect performance with 260 and 500 surveys using 200 epochs, but performance decreased slightly with larger datasets. Similar patterns were observed for the other tested architectures, with 200 epochs consistently yielding the best results.

- (C)

- PSS-14 architecturesFigure 9 presents the results of architectures trained with synthetic PSS-14 data. Performance was more variable in the largest dataset (5000 samples), but for smaller datasets (260 and 500 samples), the best configurations consistently achieved 1.0 across all metrics when trained for 200 epochs.

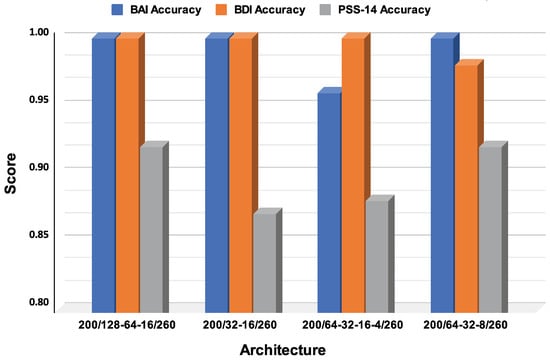

3.2. Results with Real Data

Once the optimal architectures were identified using synthetic data, their performance was evaluated with real data from 260 students. The pre-trained neural networks were applied to responses from the BAI, BDI, and PSS-14 questionnaires. The results with synthetic data suggested that the highest metric values were achieved using 200 epochs.

Figure 10 shows the accuracy results obtained with real data using the best-performing architecture (128-64-16, 200 epochs, 260 participants). The results are consistent with those obtained using synthetic data, confirming the robustness of the model and its applicability in real-world scenarios.

Figure 10.

Results of neural network training with real data.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to a rapidly expanding literature on the use of artificial intelligence for the early detection of common mental disorders in university students, a population consistently identified as being at high risk for anxiety, depression, and stress (Baran & Cetin, 2025; Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025; de Filippis & Al Foysal, 2025).

This growing interest reflects the sustained increase in prevalence, the limited availability of specialized care, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, and the demand for scalable, personalized interventions (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2021; World Health Organization, 2022). In contrast to many AI applications that rely on complex multimodal inputs, the present work shows that carefully designed deep neural networks trained exclusively on validated psychometric instruments (BAI, BDI, PSS-14) can achieve predictive performance that is comparable to, or even exceeds, that of more data-intensive approaches (Lee et al., 2021; Tutun et al., 2023). These results support the view that robust measurement and deliberate architectural design can be as important as access to large, heterogeneous data streams when developing practical screening tools for educational settings.

Recent research underscores both the promise and fragility of AI-based mental health solutions, showing that machine learning models can achieve high precision in detecting depressive and anxiety symptoms in young people while still suffering from recurrent limitations such as small, non-representative samples, limited external validation, and heterogeneous reporting of results (Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025; Shatte et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2024). In this context, the systematic exploration of 32 dense architectures using synthetic data, followed by validation on real student data, is a methodological strength because it goes beyond single-model demonstrations and provides an explicit rationale for architectural and hyperparameter choices, although the near-perfect metrics observed in a sample of 260 students must be interpreted with caution in light of the well-documented risk of overfitting, data leakage, and optimism bias in narrowly defined cohorts (Shatte et al., 2019; Yarkoni, 2020). From a technical point of view, the results confirm that moderately deep, well-regularized architectures with three or four hidden layers (128-64-16 and 64-32-16-4) and ReLU activations, trained for an adequate number of epochs, are sufficient to capture the nonlinear relationships between psychometric scores and severity levels of anxiety, depression, and stress (Chatzilygeroudis et al., 2021; Jung, 2022). This aligns with prior work showing that moderately deep networks, such as ResNet-style models with ReLU activations, often optimize training and mitigate saturation problems, while random search strategies can be more efficient than grid search for hyperparameter optimization (He et al., 2015, 2016; Nair & Hinton, 2010).

The findings also contribute to ongoing debates about the relative value of unimodal versus multimodal approaches in the prediction of mental health. Several comparative studies report that models that combine questionnaires with behavioral, physiological, or digital traces can achieve accuracies in the 70–95% range but frequently face challenges related to data integration, sensor availability, user burden, and privacy (Madububambachu et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2025). Our results indicate that, for early screening in university settings, high-quality psychometric input may partially compensate for the absence of additional modalities, as dense architectures trained on BAI, BDI, and PSS-14 scores achieved accuracies above 95%, comparable to or exceeding those of more complex systems (Shatte et al., 2019; Tutun et al., 2023; Yoo et al., 2024). From the authors’ perspective, this supports a pragmatic line of development in which universities first exploit data that are already familiar and acceptable to clinicians and students, before moving to more intrusive or technically demanding sources of information.

At the same time, the performance of the proposed model should not be interpreted as evidence that multimodal or more advanced architectures are unnecessary. Studies using electrodermal activity, speech features, or behavioral logs have shown that physiological and digital markers can improve detection of subclinical and emerging conditions, particularly when combined with self-report data (Sharma et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2025). Future work could therefore explore multimodal extensions of the present approach while explicitly weighing the potential gains in sensitivity against the additional costs in terms of hardware, data governance, and acceptability (Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025). Methodologically, the two-stage strategy adopted here—synthetic data for broad architecture exploration and real data for focused evaluation—offers a manageable path for institutions with limited resources to experiment with deep learning, but it also raises questions about how closely synthetic distributions approximate real symptom patterns and comorbidities, especially in vulnerable subgroups. These issues could be addressed by reporting calibration measures, conducting sensitivity analyses across different synthetic generation schemes, and comparing models trained solely on real data whenever sample sizes permit (Madububambachu et al., 2024; Shatte et al., 2019; Yarkoni, 2020).

Beyond predictive performance, ethical and governance considerations are central to any serious attempt to deploy AI in university mental health services. The broader literature warns that algorithmic bias, limited generalizability, and deficiencies in validation and reporting can translate into systematic disadvantages for certain groups, particularly when race, gender, socioeconomic status, or disability are not adequately considered (Lee et al., 2021; Lițan, 2025; Obermeyer et al., 2019). International guidelines therefore emphasize strict data protection, robust governance, human oversight, and precise definition of application contexts, as reflected in documents such as the WHO guidance on AI in health, CONSORT-AI, and TRIPOD-AI (Collins et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2021). Complementary initiatives, such as the European guidelines for trustworthy AI and reports on AI in health care policy, further stress the need for multidisciplinary collaboration, socio-cultural adaptation, and fairness audits as prerequisites for responsible deployment (European Commission, 2019; Floridi et al., 2018; Matheny et al., 2022).

Within this framework, the present model is conceived not as an autonomous diagnostic authority but as an early-warning and triage mechanism embedded in broader university mental health strategies. The intention is that predicted risk levels based on BAI, BDI, and PSS-14 scores support counseling services in prioritizing outreach, monitoring changes over time, and allocating scarce human resources more efficiently, rather than replacing clinical judgment (Bradford et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2021). To make such use clinically acceptable, explainability methods such as LIME and SHAP can help identify which features—cognitive, somatic, or affective items—drive specific predictions, fostering professional trust and enabling more targeted interventions (Lundberg & Lee, 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2016). In parallel, the incorporation of fairness metrics (e.g., equalized odds, demographic parity) and systematic bias-mitigation strategies is essential to minimize unintended harms in diverse student populations (European Commission, 2019; Obermeyer et al., 2019).

The emerging evidence on digital and conversational interventions helps to position the contribution of this work within a broader ecosystem of AI-enabled mental health tools. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses report that AI-driven chatbots and digital interventions often produce moderate improvements in depressive symptoms and short-term well-being among young people, but effects on anxiety, stress, and long-term outcomes are more modest and heterogeneous (Olawade et al., 2024; Wanniarachchi et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2024). These studies also highlight challenges of adherence, therapeutic alliance, and equity of access, suggesting that such tools are best understood as complements to, rather than replacements for, human-delivered care. In this light, one of the most realistic near-term roles for AI in universities is high-quality early screening, as examined here, coupled with stepped-care models in which automated risk stratification is followed by human or blended interventions of increasing intensity (Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025). The strengths of this study include the systematic testing of 32 candidate architectures, the use of three widely validated psychometric scales, and the explicit reflection on ethical and implementation issues. Nonetheless, several limitations need to be acknowledged: reliance on a single institution, absence of external validation and formal calibration, and dependence on synthetic data that may not fully capture the diversity of real-world student populations. Future research should extend validation to multiple universities and countries, conduct prospective and longitudinal studies, and explore temporal models such as recurrent networks or transformers that can capture trajectories of distress across semesters or academic years (Lee et al., 2021; Shatte et al., 2019). Ensemble methods with uncertainty quantification (e.g., MC-dropout, deep ensembles) and privacy-preserving strategies such as federated learning may further enhance robustness and protect student data while enabling multi-site collaboration (Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025; Matheny et al., 2022). In addition, integrating carefully selected passive data streams—such as smartphone use or sleep patterns—under differential privacy and clear consent frameworks could enrich predictions, provided that any gains in accuracy justify the added ethical and logistical complexity (Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2025; Sun et al., 2025).

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that artificial intelligence, in the form of optimized deep neural networks trained on validated psychometric scales (BAI, BDI, PSS-14), can achieve predictive performance comparable to that of more complex multimodal systems for the early screening of anxiety, depression, and stress in university students. The results suggest that high-quality self-report measures, combined with thoughtful architectural design and hyperparameter tuning, are sufficient to build accurate screening tools that remain feasible for institutions with limited technical and clinical resources. At the same time, the very high accuracies observed in a single university with a relatively small real-world sample indicate that the current model should be regarded as a proof of concept rather than as a deployment-ready system, given the potential for overfitting and optimism bias in this context.

From the authors’ perspective, the main contribution of this work lies not only in its numerical performance but in outlining a pragmatic pathway by which universities can leverage existing psychometric practices to incorporate AI-based screening into their mental health strategies. In practical terms, any implementation of the proposed system should be embedded in a stepped-care model, where automated risk stratification triggers timely human assessment and support, under clear protocols for referral, clinical supervision, and continuous monitoring of performance and equity across student subgroups. Future research should therefore prioritize multicenter and longitudinal validation, formal calibration analyses, and the integration of explainability and fairness metrics, as well as explore temporal and multimodal extensions only when their added complexity is justified by demonstrable gains in clinical utility and acceptability.

Author Contributions

B.J.-S.: Investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and writing of the original draft. K.O.-R.: funding acquisition, review and editing of the manuscript. N.O.-L.: formal analysis, data curation, visualization, review and editing of the manuscript. J.R.-R.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, and editing of the manuscript. J.M.O.-R.: conceptualization, data curation, visualization, validation, review and editing of the manuscript and supervision. O.R.A.: validation, writing, and review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UTSJR (protocol code: SSD-2024-01 and Approval Date: 6 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., Kessler, R. C., Liu, H., Mortier, P., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Demyttenaere, K., … Bruffaerts, R. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2955–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, F. D. E., & Cetin, M. (2025). AI-driven early diagnosis of specific mental disorders: A comprehensive study. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 19(1), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory—II. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, A., Meyer, A. N. D., Khan, S., Giardina, T. D., & Singh, H. (2024). Diagnostic error in mental health: A review. BMJ Quality & Safety, 33(10), 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzilygeroudis, K., Hatzilygeroudis, I., & Perikos, I. (2021). Machine learning basics. In P. Eslambolchilar, A. Komninos, & M. Dunlop (Eds.), Intelligent computing for interactive system design (1st ed., pp. 143–193). ACM. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2136404 (accessed on 21 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Collins, G. S., Moons, K. G. M., Dhiman, P., Riley, R. D., Beam, A. L., Van Calster, B., Ghassemi, M., Liu, X., Reitsma, J. B., van Smeden, M., Boulesteix, A.-L., Camaradou, J. C., Celi, L. A., Denaxas, S., Denniston, A. K., Glocker, B., Golub, R. M., Harvey, H., Heinze, G., … Logullo, P. (2024). TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gonzalez, P., He, A. W.-J., Lam, E. P., Ng, I. M. C., Li, M. W., Hou, R., Chan, J. N.-M., Sahni, Y., Vinas Guasch, N., Miller, T., Lau, B. W.-M., & Sánchez Vidaña, D. I. (2025). Artificial intelligence in mental health care: A systematic review of diagnosis, monitoring, and intervention applications. Psychological Medicine, 55, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Filippis, R., & Al Foysal, A. (2025). AI-driven mental disorder prediction: A machine learning approach for early detection. Open Access Library Journal, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A. (2023). University student mental health: An important window of opportunity for prevention and early intervention. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 68(7), 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2019). Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI | Shaping Europe’s digital future. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., Chatila, R., Chazerand, P., Dignum, V., Luetge, C., Madelin, R., Pagallo, U., Rossi, F., Schafer, B., Valcke, P., & Vayena, E. (2018). AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28(4), 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2015). Deep residual learning for image recognition. arXiv, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016, June 27–30). Deep residual learning for image recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (pp. 770–778), Las Vegas, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H., & Aerts, H. J. W. L. (2018). Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nature Reviews Cancer, 18(8), 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2021). Encuesta nacional de bienestar autorreportado (ENBIARE). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enbiare/2021/#documentacion (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Jung, A. (2022). Machine learning: The basics. Springer Nature. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=1IBaEAAAQBAJ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Lee, E. E., Torous, J., De Choudhury, M., Depp, C. A., Graham, S. A., Kim, H.-C., Paulus, M. P., Krystal, J. H., & Jeste, D. V. (2021). Artificial Intelligence for mental health care: Clinical applications, barriers, facilitators, and artificial wisdom. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging, 6(9), 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levant, R. F., & Shapiro, A. E. (2002). Training psychologists in clinical psychopharmacology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(6), 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liopyris, K., Gregoriou, S., Dias, J., & Stratigos, A. J. (2022). Artificial intelligence in dermatology: Challenges and perspectives. Dermatology and Therapy, 12(12), 2637–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lițan, D.-E. (2025). Mental health in the “era” of artificial intelligence: Technostress and the perceived impact on anxiety and depressive disorders—An SEM analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1600013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Cruz Rivera, S., Moher, D., Calvert, M. J., & Denniston, A. K. (2020). Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: The CONSORT-AI extension. Nature Medicine, 26(9), 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in neural information processing systems (NeurIPS) (Vol. 30). Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/8a20a8621978632d76c43dfd28b67767-Abstract.html (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Madububambachu, U., Ukpebor, A., & Ihezue, U. (2024). Machine learning techniques to predict mental health diagnoses: A systematic literature review. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 20, e17450179315688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, M., Israni, S. T., Ahmed, M., & Whicher, D. (2022). Artificial intelligence in health care: The hope, the hype, the promise, the peril (Vol. 2019). National Academies Press. Available online: https://ehealthresearch.no/files/documents/Rapporter/Andre/2019-12-AI-in-Health-Care.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- McGorry, P. D., Purcell, R., Goldstone, S., & Amminger, G. P. (2011). Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: Implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(4), 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V., & Hinton, G. E. (2010, June 21–24). Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML’10) (pp. 807–814), Haifa, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B., Wada, O. Z., Odetayo, A., David-Olawade, A. C., Asaolu, F., & Eberhardt, J. (2024). Enhancing mental health with Artificial Intelligence: Current trends and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 3, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U. K., Anwar, A., Saleem, S., Malik, P., Rasul, B., Patel, K., Yao, R., Seshadri, A., Yousufuddin, M., & Arumaithurai, K. (2021). Artificial intelligence as an emerging technology in the current care of neurological disorders. Journal of Neurology, 268(5), 1623–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016, August 13–17). “Why should I trust you?”: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 1135–1144), San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. K., Alutaibi, A. I., Khan, A. R., Tejani, G. G., Ahmad, F., & Mousavirad, S. J. (2025). Early detection of mental health disorders using machine learning models using behavioral and voice data analysis. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 16518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatte, A. B. R., Hutchinson, D. M., & Teague, S. J. (2019). Machine learning in mental health: A scoping review of methods and applications. Psychological Medicine, 49(9), 1426–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J., Lu, T., Shao, X., Han, Y., Xia, Y., Zheng, Y., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ravindran, A., Fan, L., Fang, Y., Zhang, X., Ravindran, N., Wang, Y., Liu, X., & Lu, L. (2025). Practical AI application in psychiatry: Historical review and future directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 30(9), 4399–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutun, S., Johnson, M. E., Ahmed, A., Albizri, A., Irgil, S., Yesilkaya, I., Ucar, E. N., Sengun, T., & Harfouche, A. (2023). An AI-based Decision Support System for Predicting Mental Health Disorders. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(3), 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanniarachchi, V. U., Greenhalgh, C., Choi, A., & Warren, J. R. (2025). Personalization variables in digital mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in adolescents and youth: A scoping review. Frontiers in Digital Health, 7, 1500220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance (1st ed.). World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yarkoni, T. (2020). The generalizability crisis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 45, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J. H., Jeong, H., An, J. H., & Chung, T.-M. (2024). Mood disorder severity and subtype classification using multimodal deep neural network models. Sensors, 24(2), 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Zhao, S., Yang, Z., Zheng, H., & Lei, M. (2024). An artificial intelligence tool to assess the risk of severe mental distress among college students in terms of demographics, eating habits, lifestyles, and sport habits: An externally validated study using machine learning. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.