Abstract

This study examines the impact of a Science–Technology–Society–Environment (STSE) educational intervention on the teaching of acid–base reactions to 11th-grade students (n = 17). The didactic sequence combined laboratory experiments, real-data analysis, and an interdisciplinary role-play debate, designed to connect chemical concepts with pressing socio-environmental challenges such as ocean acidification, acid rain, and acid mine drainage. Data collection included a pre- and post-test on environmental awareness and semi-structured interviews, enabling the assessment of both conceptual learning and attitudinal change. Significant conceptual gains were observed, with five of eleven test items reaching a normalized Hake gain ≥ 0.70, alongside increased environmental awareness. Qualitative findings further revealed that students valued the real-world context and interdisciplinary integration, reporting enhanced motivation, civic responsibility, and a more meaningful engagement with science. Overall, the results suggest that STSE-based chemistry instruction not only strengthens students’ understanding of acid–base equilibria but also fosters sustainability competencies essential for responsible and informed citizenship in the 21st century.

1. Introduction

Acid–base reactions play a central role in environmental processes, with profound implications for ecosystems, public health, and the global economy. The release of acidic or basic substances into the environment can disrupt the chemical balance of water, soils, and the atmosphere, leading to large-scale ecological degradation. Among the most critical acid–base phenomena are acid rain, ocean acidification, and water pollution from industrial effluents, all of which are directly linked to anthropogenic activity (Grennfelt et al., 2020; Ibrahim et al., 2024; Mohajan, 2019; L. Zhang et al., 2024). Acid rain, for instance, results from the atmospheric transformation of sulfur and nitrogen oxides into sulfuric and nitric acids, which alter the pH of lakes, rivers, and soils, reducing biodiversity and damaging agriculture and cultural heritage (Doney et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2025). Similarly, ocean acidification, caused by the absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and the consequent formation of carbonic acid, undermines the calcification capacity of marine organisms, threatening marine ecosystems and food security (Jia et al., 2024; Meenakshipriya et al., 2009). Mining activities and industrial discharges further contribute to water acidification, mobilizing toxic heavy metals with severe consequences for aquatic life (Pedretti & Nazir, 2011; Sharma & Ahammed, 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2021). These global challenges highlight the need for sustainable strategies to monitor, prevent, and mitigate acid–base related environmental impacts.

In this context, science education plays a crucial role in fostering scientific literacy and preparing students to critically engage with sustainability challenges. The Science–Technology–Society–Environment (STSE) approach, rooted in the early 20th century and developed extensively in recent decades, seeks to integrate scientific knowledge with technological, social, and environmental dimensions (Pedretti & Bellomo, 2013; Silva, 2020). However, environmental education and chemistry education often evolve as parallel strands, despite their shared aim of enabling students to understand and act upon complex environmental problems. To strengthen this connection, several authors argue that chemistry education must explicitly embrace environmental education principles, promoting not only conceptual understanding but also environmentally responsible behaviors. The connection between environmental education and chemistry education has been increasingly emphasized in recent literature (Kortam et al., 2025; Gunbatar et al., 2025). Environmental issues provide authentic and socially relevant contexts for learning core chemical concepts and for strengthening students’ scientific literacy. Chemistry teachers frequently report that topics such as air and water pollution, global warming, and energy use naturally bridge disciplinary content with real-world challenges, making chemistry more meaningful and engaging for students (Kortam et al., 2025). Recent systematic reviews of green and sustainable chemistry education indicate that sustainability-oriented curricular approaches can enhance both conceptual understanding and instructional effectiveness (Gunbatar et al., 2025). Integrating environmental perspectives within chemistry instruction not only promotes environmental awareness but also reinforces the relevance and social value of chemistry as a discipline (Kortam et al., 2025). These insights support the pedagogical rationale underlying the present study.

Closely related to the STSE perspective, socioscientific issues (SSI) have emerged as a prominent and well-established approach in science education. Within this line of research, SSI-based education is conceived as a way of engaging students with complex, real-world problems that are scientifically informed yet socially, ethically, and politically contested, such as climate change, environmental pollution, and sustainability challenges (Newton & Zeidler, 2020; Lee et al., 2020). Empirical studies further indicate that SSI approaches can foster argumentation skills, science interest, and students’ self-efficacy in participating in science-related societal debates (Smit et al., 2025). Although STSE and SSI are sometimes treated as distinct traditions, recent scholarship emphasizes their strong conceptual convergence. Both approaches are grounded in a “science-in-context” orientation that seeks to situate scientific knowledge within broader societal and environmental frameworks and to support the development of informed and responsible citizenship (Bencze et al., 2020). While SSI typically foregrounds structured engagement with specific controversial issues and explicit ethical reasoning, STSE adopts a broader systemic lens that highlights the interrelationships among Science, Technology, Society, and the Environment. In this sense, SSI can be understood as a complementary pedagogical approach that operates within, and enriches, the wider STSE framework. In the present study, the STSE approach provides the primary conceptual grounding, as it allows acid–base chemistry to be contextualized within interconnected environmental and societal systems rather than through a single socioscientific controversy. Nevertheless, insights from SSI research (Bencze et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Newton & Zeidler, 2020; Smit et al., 2025) inform the design and interpretation of the intervention, especially regarding the importance of engaging students in reflective thinking about environmental problems and their civic and ethical dimensions.

In line with these perspectives, instead of presenting science as a static body of knowledge, the STSE approach promotes a dynamic, socially relevant practice, encouraging students to reflect on ethical implications, policy decisions, and the societal impact of scientific innovation (Ayres-Pereira et al., 2024; Giffoni et al., 2020). Research in chemistry education has shown that STSE-based methodologies enhance student motivation, critical thinking, and the ability to connect abstract concepts with real-world problems (F. Araújo & Sampaio, 2022; Martins, 2009). The promotion of positive attitudes towards the environment has been recognized as a central axis of science education, since environmental awareness fosters responsible and sustainable behaviors (Liu & Chen, 2019; Milfont & Duckitt, 2010). Several studies highlight that environmental education should address not only the cognitive domain but also the affective one, strengthening emotional connections with nature, stimulating motivation, and fostering pro-environmental behaviors (J. L. Araújo et al., 2023a, 2023b; Korkmaz, 2018). In this sense, developing pedagogical approaches that articulate scientific knowledge with concrete environmental problems is an effective way to raise students’ awareness of global issues and prepare them for informed and responsible decision-making. Along the same lines, the chemistry education literature highlights the limitations of traditional expository practices, which tend to promote passivity and reinforce the perception of the discipline as abstract and decontextualized (Cardellini, 2012; Gulacar et al., 2018). As a response, several authors advocate context-based learning, using real and socially relevant situations as a starting point for knowledge construction. These methodologies have proven effective not only in increasing chemical literacy but also in stimulating enthusiasm and perceived relevance, as they allow students to transfer learning to new problems close to their reality (J. L. Araújo et al., 2023a; Swirski et al., 2018; Wiyarsi et al., 2020).

Thus, both in environmental education and in chemistry, there is consensus that the integration of real and meaningful contexts promotes not only conceptual understanding but also the development of positive attitudes and competences essential for responsible citizenship. This is particularly relevant for acid–base chemistry, where contextualized problems such as acid rain, ocean acidification, and wastewater treatment provide meaningful opportunities for inquiry-based learning, and where inquiry-based approaches have also been shown to enhance students’ oral and written communication skills through authentic and problem-based activities (Vilela et al., 2025).

Several studies have confirmed the benefits of STSE-oriented acid–base instruction. Carvalhosa (Carvalhosa, 2015) demonstrated that Portuguese secondary students improved both conceptual understanding and process skills through STSE-based activities such as role-play and laboratory investigations. Priyambodo et al. (2021) found that Indonesian students in an experimental STSE group achieved significantly higher motivation and engagement than those taught through traditional instruction. Other investigations highlight the value of integrating the history and nature of science, fieldwork related to acid mine drainage, or structured pedagogical models such as REACT or 5Es (Ültay & Çalik, 2016). Additional contributions emphasize innovative approaches in chemistry education, such as the use of poetry and the arts to challenge disciplinary boundaries (J. L. Araújo et al., 2015; Paiva et al., 2013), the involvement of families through technology (Paiva et al., 2017), simulation-based activities to foster submicroscopic reasoning (Spitha et al., 2024), or inquiry practices with low-cost, remote experiments like acid–base titration (Cachichi et al., 2025). Together, these diverse strategies point to deeper learning, stronger engagement, and in some cases, greater environmental awareness. Despite these advances, traditional transmissive teaching methods still dominate classroom practice, limiting the potential for education to meaningfully address sustainability (Jiménez-Liso et al., 2020).

Building on this framework, the present study aimed to investigate the impact of implementing an STSE approach in the teaching of acid–base reactions. Specifically, it sought to examine how the integration of scientific content with real socio-environmental issues can influence students’ learning, motivation, and perceptions of science and its role in society. More concretely, the study pursued to answer the following questions:

RQ1.

To what extent does an STSE approach improve students’ conceptual understanding of acid–base reactions compared to their pre-instruction knowledge?

RQ2.

How does STSE-based instruction influence students’ environmental awareness and sense of civic responsibility?

RQ3.

What are students’ perceptions and preferences regarding the STSE approach compared to traditional expository teaching?

2. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted within the field of science education and adopted a mixed-methods design, in order to balance the strengths and limitations of both methods (Towns, 2008). The study followed a reflective pedagogical intervention logic, addressing a concrete educational problem: students’ difficulties in learning and contextualizing acid–base reactions. The intervention sought to implement, monitor, and reflect on an innovative teaching strategy in a real classroom setting, combining quantitative assessment tools with in-depth qualitative exploration. The study was carried out in a secondary school in Portugal with a class of 17 students from the 11th grade Science and Technology track, aged 15 to 18 years. The research followed the ethical principles of educational research. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians for participation and for the recording of interviews. Only students who participated in all activities and guardians provided formal authorization were included in the study. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured through alphanumeric identifiers (e.g., A1, A2).

Due to attendance and informed consent constraints, a total number of 13 students completed both the pre- and post-test on chemistry conceptual understanding and environmental awareness, while 10 students participated in the final interviews.

2.1. Description of the Intervention

The intervention was developed over two weeks and consisted of a structured didactic sequence based on the STSE approach. Three main activities were implemented:

- Critical reading of an adapted news article on acid rain, designed to introduce the theme, promote questioning and reflection, and situate acid–base reactions in social and environmental contexts.

- Laboratory activity on acid neutralization, simulating acid mine drainage (typically occurs when rainwater interacts with exposed rocks in mining areas, producing acidic water that can contaminate rivers and soils). Students, working in small groups, tested the neutralization of an artificially prepared acidic solution equivalent to water typically found in mining areas. Using different basic substances (both solid and aqueous), they monitored pH variations with a digital probe. This activity not only aimed to reinforce the chemical concept of neutralization, but also to reproduce on a small scale an environmental remediation process commonly applied to mitigate the harmful effects of acidified waters on ecosystems. At the same time, it fostered the development of experimental, analytical, and collaborative skills.

- Interdisciplinary role-play debate on ocean acidification, where students represented specialists from Chemistry, Biology, and Social/Economic domains. They researched, presented arguments, and defended mitigation proposals. Afterwards, mixed groups synthesized findings in a scientific poster, consolidating the concepts and transversal skills developed.

This design combined reading and interpretation, hands-on experimentation, debate, and collaborative synthesis, fostering interdisciplinarity and student engagement. To clarify the structure of the intervention and the distribution of activities across the two-week period, Figure 1 presents a schematic representation of the sequence of tasks, including environmental awareness pre- and post-tests, the adapted news reading, the laboratory neutralization activity, the debate, and the final interviews. Interview and Test Protocols can be seen in Supplementary Material S1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the instructional sequence implemented during the two-week intervention.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis Instruments

The pre- and post-test instrument was developed by the first author. To ensure content and face validity, the full test was reviewed by an experienced chemistry teacher and one researcher in chemical education, who examined the clarity, scientific accuracy, and alignment of each item with the intended learning outcomes. Minor revisions were made based on their feedback before classroom implementation. The same 13-item instrument was administered as both the pre-test and the post-test, ensuring direct comparability of students’ responses before and after the intervention and allowing the assessment of both chemistry conceptual understanding and environmental awareness.

The test included:

- A set of 11 conceptual open-ended questions (Q1–Q10, Q13), structured according to Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom & Krathwohl, 1969), ranging from basic comprehension to critical analysis and real-world application. These questions encouraged students not only to explain chemical processes (e.g., acid neutralization in the context of mine drainage) but also to reflect on the seriousness of environmental issues, the societal and economic impacts of acidification, and their own role as citizens in addressing these challenges.

- Two questions related to attitudes and values (Q11, Q12): three multiple-choice questions on fundamental acid–base concepts and related environmental phenomena (e.g., ocean acidification, acid rain) and a Likert-scale item measuring the degree of environmental concern, using a 5-point scale ranging from “not concerned at all” (1) to “very concerned” (5), aimed at capturing students’ affective engagement with sustainability issues. For instance, students were asked to rate their level of concern about problems such as acid rain or ocean acidification.

A semi-structured interview protocol comprising 13 open-ended questions was administered after the intervention to explore students’ perceptions of the STSE approach, their evaluation of the activities, and their reflections on the value of interdisciplinary and contextualized teaching (IQ1–IQ13). The interviews were conducted individually by the first author in a neutral, non-evaluative manner and had an average duration of approximately 10 min. All interviewees were 11th-grade students (n = 10) from the same class that participated in the intervention. Each interview was audio-recorded and fully transcribed, and the resulting data were examined through qualitative thematic analysis conducted by the first author. Since the qualitative coding was performed solely by the researcher, interrater reliability is not applicable in this context.

Quantitative data (pre- and post-tests) were analyzed by direct comparison of results, descriptive statistics (relative frequencies), and the calculation of normalized gain of Hake (1998) (g) according to Equation (1):

where values are classified as low (g < 0.30), medium (0.30 ≤ g < 0.70), or high (g ≥ 0.70).

For the attitudinal questions (Q11 and Q12), a Global Environmental Concern Level was created specifically for this study to allow a multifactor evaluation of students’ attitudinal responses. This classification integrates three dimensions: (i) the self-reported level of concern on a 5-point Likert scale, (ii) whether students indicated an intended or declared pro-environmental action (Yes/No), and (iii) the relevance and quality of their written justification. Based on the combination of these criteria, responses were coded into five categories (Very Low, Low, Moderate, High and Very High) following a decision matrix developed by the authors. Table 1 provides the operational criteria used for each level.

Table 1.

Criteria developed by the author for classifying the Global Environmental Concern Level, considering the Likert scale responses, the reported action (Yes/No), and the relevance of students’ justifications.

Qualitative data (interviews) were analyzed using content analysis (Table 2). A coding grid with five predefined categories (scientific understanding, environmental awareness, STSE approach, pedagogical experience, and personal/future impact) was developed and later refined according to emerging evidence. Representative quotations were selected to illustrate students’ perspectives, maintaining fidelity to their original wording (ellipses were used only to shorten passages without altering meaning).

Table 2.

Categories of analysis of the interview questions (IQ) conducted with students and respective description.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Chemistry Conceptual Understanding and Environmental Awareness Pre- and Post-Test

A pre- and post-test composed of 13 questions was administered to evaluate the impact of the STSE-based intervention on students’ chemistry conceptual understanding and environmental awareness. The test included 11 conceptual questions (Q1–Q10, Q13) and two questions related to attitudes and values (Q11, Q12).

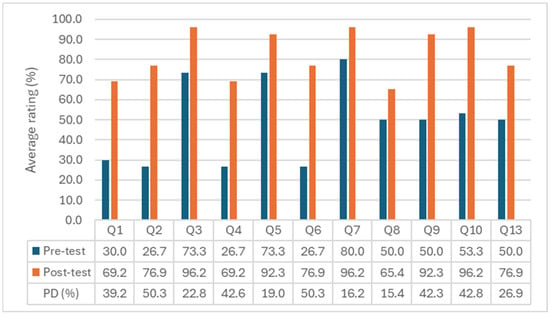

Figure 2 shows the percentage of correct answers per question in the pre- and post-test. All questions revealed improvements, with particularly notable gains in Q2, Q6, Q10, Q4, and Q9, where the percentage differences between pre- and post-test responses were 50%, 50%, 43%, 43%, and 42%, respectively. Questions Q3, Q5, Q7, Q9, and Q10 already showed satisfactory performance in the pre-test but still improved in the post-test, reaching values close to or above 90%.

Figure 2.

Mean scores (%) obtained in the pre- and post-test of environmental awareness per question (Q1 to Q10 and Q13), including the percentage difference (PD) between them.

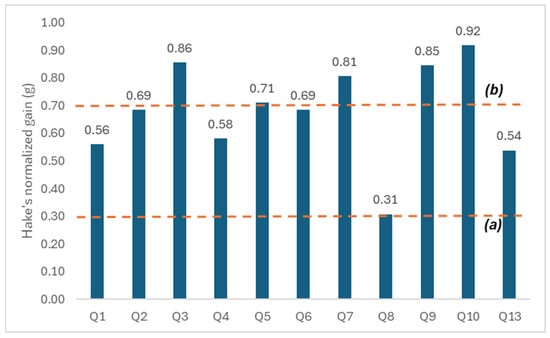

Hake’s normalized gain (g) was calculated to quantify learning progress. According to Figure 3, five questions (Q3, Q5, Q7, Q9, Q10) showed high gains (g ≥ 0.70), while another five (Q1, Q2, Q4, Q6, Q13) showed intermediate gains (0.30 ≤ g < 0.70). Only Q8 registered a lower gain (g = 0.31).

Figure 3.

Hake’s normalized gains (g) per question of the environmental awareness test (Q1–Q10 and Q13). Line (a) indicates the threshold for low gain (g = 0.3) and line (b) the threshold for high gain (g = 0.7), according to Hake’s classification (Hake, 1998).

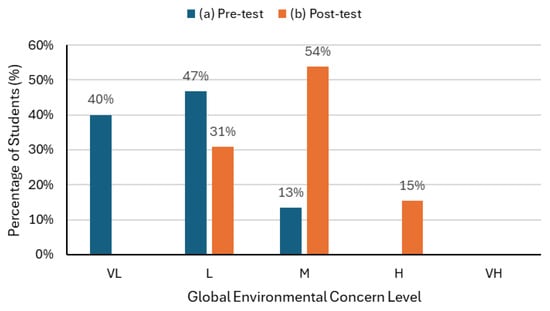

For the attitudinal questions (Q11 and Q12), students were assigned a Global Environmental Concern Level.

The attitudinal dimension was assessed through two complementary questions: a Likert-scale item (Q11) asking students to rate their concern with the environmental impacts of acid–base phenomena (acid rain, water pollution, ocean acidification; 1 = no concern, 5 = very high concern), and an open-ended question (Q12) inquiring whether they had ever taken personal or collective action to reduce such impacts, requiring justification.

The analysis of students’ responses revealed a clear evolution in environmental attitudes after the intervention (Figure 4). In the pre-test, 40% of students were classified with very low concern and 47% with low concern, while only 13% showed a moderate concern. Following the didactic sequence, the very low category disappeared, 54% of students were reclassified as moderate, and 15% reached the high concern level.

Figure 4.

Percentage distribution of students’ Global Environmental Concern Level in (a) the pre-test and (b) the post-test, according to the qualitative scale (VL—Very Low, L—Low, M—Moderate, H—High, VH—Very High).

Beyond the quantitative shift, Q12 also provided qualitative insights into students’ reasoning and attitudes. In the pre-test, most answers were limited to short statements such as “No” or general remarks like “I never thought about it,”. After the intervention, however, several students expressed a clear intention to change their habits and act more responsibly. For instance, some mentioned walking or using public transport more often and encouraging others to be environmentally conscious: “After hearing in class about the problems this can cause in the future, I started thinking about changing my habits” (S7); “I think it’s up to each of us, not just the government, to solve this” (S4); “I want to be more careful and also help others to understand these issues” (S5).

3.2. Qualitative Results from Student Interviews

The qualitative analysis of student interviews provided deeper insights into students’ perceptions of the STSE-based intervention and its impact on their learning, attitudes, and motivation.

In relation to scientific understanding (Category A), students generally demonstrated solid comprehension of the phenomena addressed. Several were able to articulate the chemical processes involved in ocean acidification, such as when one student explained that “ocean acidification occurs when atmospheric CO2 is absorbed by seawater, forming carbonic acid, which increases H+ concentration and decreases pH” (S6). Others noted that their understanding of neutralization was strengthened by hands-on experimentation, with one stating that “we used a basic substance to neutralize the mine water, measuring the pH until it reached between 6.5 and 7.5” (S5).

The intervention also fostered environmental awareness and civic reflection (Category B). Students acknowledged the seriousness of acidification and its multiple consequences, as illustrated by one who noted that it “affects the economy, since coastal populations depend on fishing (…) and it also impacts tourism and biodiversity through coral destruction” (S5). For some, this awareness led to intentions of personal change: “I think I need to change after hearing in class about the problems this could cause in the future” (S7). Perspectives on responsibility varied, with some emphasizing individual agency and others pointing to structural causes such as industry.

When reflecting on the STSE approach itself (Category C), students stressed the value of applying Chemistry to real problems and the benefit of interdisciplinarity. As one explained, “we used a practical example, the mine water; it’s easier to understand than just hearing the theory” (S1). Another highlighted that “I understood the seriousness of the situation because it combined all those disciplines” (S2).

In terms of pedagogical experience and motivation (Category D), the laboratory activity and the interdisciplinary debate were the most valued, as they allowed direct engagement with the phenomena and collaborative discussion. One student remarked, “by handling the materials and being closer to the phenomenon, I understood much better” (S7), while another commented that the debate was “a good summary of what we had learned, with several people explaining in different words” (S1). In contrast, reading tasks were seen as less engaging, although students acknowledged their importance for contextualization. A minority expressed preference for more traditional teaching, particularly in the context of exam preparation, reflecting a tension between innovative methods and curricular demands.

Finally, students emphasized the personal impact and future relevance of the project (Category E). One noted that “school should provide environmental education (…) these things help us understand the real world and the link between subjects and life” (S5), while another stressed the transversal competences developed, including “communication, research, experimentation, debates, posters (…) not only content” (S8). Although overall feedback was highly positive, suggestions for improvement included smaller laboratory groups and more time allocated for debate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Analysis—Environmental Awareness Test (Pre- and Post-Test)

The quantitative results demonstrate both conceptual and attitudinal progress. High Hake gains in Q2, Q6, and Q9 (focused on acid–base reactions, pH, and ion formation) indicate that although students initially struggled with new concepts, the intervention enabled substantial understanding. This confirms that STSE strategies—especially laboratory work and guided problem-solving, facilitate the construction of meaningful knowledge. Similar outcomes have been observed in context-based and inquiry-oriented chemistry education (Cachichi et al., 2025), where accessible laboratory experiences promoted engagement and conceptual reinforcement even in resource-limited settings.

Although Q8 exhibited only a modest gain (g = 0.31), this outcome is noteworthy given that the concept assessed was not explicitly addressed during the intervention. This suggests that students may have benefited from indirect learning or the spontaneous transfer of newly acquired knowledge to related contexts.

Higher-order cognitive questions such as Q4 and Q10 (Bloom’s taxonomy: application and analysis) also improved markedly. Students moved from low pre-test scores to strong post-test performance, suggesting that interdisciplinary activities and debates encouraged deeper analytical thinking.

Persistent misconceptions, such as confusing acid rain with ocean acidification (Q1), highlight the challenge of differentiating abstract but related phenomena. This aligns with findings from Carvalhosa (Carvalhosa, 2015), who also reported conceptual overlap in students’ explanations.

The integration of scientific concepts with real-world environmental issues (Q3, Q7, Q10) resulted in consistently strong post-test performance, which supports previous studies (Priyambodo et al., 2021; Spitha et al., 2024; Ültay & Çalik, 2016) showing that STSE approaches enhance students’ ability to connect chemistry to social and environmental contexts.

The increase in environmental concern observed in the Likert scale items reinforces the attitudinal impact of the intervention. The analysis of results reveals a positive and notable shift in students’ concern level, characterized by the disappearance of the “very low” concern level and the emergence of “high” concern levels in the post-test. This suggests that engaging with authentic problems (e.g., acidification, neutralization of mining effluents) sensitized students to broader sustainability issues. These findings echo Ayres-Pereira et al. (2024) and Giffoni et al. (2020), who emphasize STSE’s role in fostering active citizenship and environmental awareness.

In summary, the convergence of conceptual gains and attitudinal changes indicates that STSE-based teaching not only strengthens content knowledge but also promotes responsible citizenship, critical thinking, and motivation, validating its pedagogical effectiveness in acid–base education.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis of Students Interviews

The qualitative analysis of the interviews corroborated the quantitative conceptual gains, showing that students developed a more solid understanding of scientific phenomena when these were contextualized in real-world issues (e.g., ocean acidification and neutralization).

These findings reflect the potential of STSE-based teaching to promote conceptual understanding, as students were able to articulate the underlying chemical processes with greater depth and confidence. This outcome aligns with the finding of Carvalhosa (2015) and Priyambodo et al. (2021), who demonstrated that embedding acid–base concepts in authentic socio-environmental contexts enhances both comprehension and engagement.

The qualitative interview analysis also revealed a heightened awareness of environmental and civic responsibility, with students often linking the severity of acidification to its ecological, economic, and social impacts, and reflecting on their own role in mitigating such problems. This depth of reflection, which encompassed both the need for individual behavioral change and institutional responsibility, demonstrates that STSE goes beyond conceptual learning. These perspectives resonate with Ültay and Çalik (2016), who found that STSE fosters not only conceptual learning but also attitudinal and ethical development, and with Jiménez-Liso et al. (2020), who stresses its role in building socially responsible scientific literacy.

Another strong theme was the relevance and motivational value of contextualization and interdisciplinarity. Students emphasized that working with real cases, such as acid mine drainage or ocean acidification, made chemistry “more useful and realistic,” and that integrating perspectives from Biology, Economy, and Society provided a broader understanding of environmental issues. This convergence with studies by Ayres-Pereira et al. (2024) and Giffoni et al. (2020) confirms the effectiveness of interdisciplinary STSE strategies in promoting meaningful learning and critical thinking.

Students consistently valued the hands-on and collaborative nature of the activities, particularly the laboratory neutralization experiment and the interdisciplinary debate, which they reported as the most engaging components of the project.

These experiences helped them consolidate knowledge and develop transversal competences such as argumentation, communication, and teamwork. This pattern resonates with research on SSI, which highlights the role of argumentation, perspective taking, and engagement with complex and contested environmental problems in science education (Newton & Zeidler, 2020; Lee et al., 2020). Such experiences have also been shown to strengthen students’ interest and confidence in participating in science-related societal debates (Smit et al., 2025). This interpretation is further supported by F. Araújo and Sampaio (2022), who emphasize that STSE methodologies enhance motivation and foster skills that extend beyond content knowledge. Likewise, creative and cross-disciplinary practices, as demonstrated by J. L. Araújo et al. (2015), strengthen conceptual understanding and communication by linking science to cultural and social contexts. The participatory and inquiry-based structure of the project also parallels the benefits observed in simulation-based and low-cost experimental environments (Cachichi et al., 2025; Spitha et al., 2024), which have been shown to enhance reasoning, engagement, and the ability to connect scientific theory with real-world application. Overall, these findings confirm that STSE-oriented learning promotes more than conceptual mastery: it nurtures personal reflection, collaborative learning, and the development of transversal competences, which are essential foundations for sustainability-oriented science education.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of an STSE-based (Science–Technology–Society–Environment) instructional sequence on students’ learning of acid–base reactions, their environmental awareness, and their perceptions of this pedagogical approach. The intervention, which combined laboratory work, interdisciplinary debate, and the production of a scientific poster, was designed to connect chemical concepts with authentic socio-environmental issues. The results provide coherent answers to the three research questions guiding the study.

Regarding students’ conceptual understanding of acid–base reactions (RQ1), the pre-/post-test results showed clear and consistent learning gains. Five of the eleven conceptual questions achieved high normalized Hake gains (g ≥ 0.70), and the remaining questions presented intermediate gains, indicating substantial improvement. These findings suggest that the STSE framework promoted meaningful conceptual development, enabling students not only to learn the underlying chemistry of neutralization and pH changes but also to apply this knowledge to real-world contexts. This interpretation is reinforced by the interview data, where students articulated informed explanations of phenomena such as ocean acidification and acid mine drainage and proposed scientifically grounded mitigation strategies.

Concerning the influence of the STSE approach on students’ environmental awareness and civic responsibility (RQ2), both quantitative and qualitative evidence indicate a positive shift. The Likert-scale results showed that “very low” levels of concern disappeared in the post-test, and a subset of students (15%) reached a “high” level of environmental concern. Interview responses revealed increased reflection on personal and collective responsibility, with students describing intentions to adopt more sustainable habits—such as walking more frequently, using public transportation, or encouraging others to act responsibly. These findings suggest that linking scientific content with social, ethical, and environmental dimensions fostered a more critical and engaged stance toward sustainability issues.

Finally, in relation to students’ perceptions of the STSE approach compared with traditional instruction (RQ3), the qualitative data highlight a predominantly positive reception. Students valued the practical and collaborative nature of the activities, describing them as more motivating, relevant, and connected to real life than conventional expository lessons. Many emphasized that working with concrete environmental problems helped them understand why acid–base chemistry matters beyond the classroom. Even students who expressed a preference for traditional teaching due to exam-related pressures acknowledged the benefits of the STSE approach in promoting participation and deepening understanding. Overall, the findings indicate that this pedagogical approach enhanced students’ engagement and offered a more meaningful learning experience.

In conclusion, the convergence of evidence across the three research questions demonstrates that the STSE-based instructional sequence contributed to strengthening students’ conceptual understanding, increasing their environmental awareness, and improving their motivation and perceptions of chemistry learning. By integrating sustainability-related issues such as ocean acidification and acid mine drainage into acid–base instruction, this study shows that contextualized, interdisciplinary, and student-centered approaches can prepare learners to engage critically and responsibly with contemporary socio-environmental challenges. These results support the inclusion of STSE frameworks as a promising pathway toward more relevant, participatory, and sustainability-oriented chemistry education.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The study presents limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample size was small (n = 17, with 13 completing both tests and 10 participating in interviews). This limited the possibility of conducting more robust statistical analyses and constrains the generalizability of the findings beyond this classroom context. While small samples are common in exploratory research, the results should be interpreted with caution. Regarding data analysis, the study relied on descriptive statistics and Hake’s normalized gain to characterize students’ conceptual progress. Inferential statistical tests were not applied because the final sample offered insufficient power for reliable hypothesis testing, increasing the risk of Type II errors. As this was an exploratory mixed-methods study implemented with a single intact class, the manuscript avoids claims of statistical significance and interprets improvements as descriptive patterns that reflect observable learning gains within this context.

Second, the study did not include a control group receiving traditional instruction. Because all students participated in the STSE intervention, it is not possible to attribute observed gains solely to the instructional approach. Although implementing a parallel control group would introduce pedagogical or contextual constraints, future research could explore quasi-experimental alternatives such as delayed-treatment or matched comparison groups.

Third, the contextualized nature of the study limits transferability. The intervention took place in a single school with one 11th-grade class. Larger and more diverse samples across different types of schools and student profiles would allow for broader conclusions.

Finally, future studies should examine how contextualized, problem-based learning can be integrated more systematically without conflicting with curricular pacing, particularly in years with high-stakes examinations.

Overall, these limitations position the study as an exploratory case study that demonstrates the feasibility and promise of STSE-based instruction, while highlighting the need for larger-scale and controlled investigations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci16010038/s1. Supplementary Material S1. Interview and Test Protocols.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G. and C.M.; Methodology, G.G. and C.M.; Software, G.G.; Validation, G.G. and C.M.; Formal analysis, G.G. and C.M.; Investigation, G.G.; Resources, G.G.; Data curation, G.G.; Writing—original draft, G.G.; Writing—review and editing, C.M.; Visualization, G.G. and C.M.; Supervision, C.M.; Funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work is funded by National Funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I. P., under projects UID/00081/2025, from the Chemistry Research Center of the University of Porto (CIQUP), and LA/P/0056/2020, from the Institute of Molecular Sciences (IMS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

As indicated in the manuscript under the section Institutional Review Board Statement, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Direction of the Inês de Castro Secondary School, Portugal. Informed consent was obtained from all participants’ parents or guardians involved in the study (Informed Consent Statement). This approval was granted at the beginning of the 2024/2025 academic year, and no formal approval code is associated with it.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subject’s parents/guardians involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in this study for their engagement and thoughtful contributions throughout the intervention and interviews. The authors also acknowledges the support of the school administration for authorizing the implementation of the project and facilitating the research procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STSE | Science-Technology-Society-Environment |

| g | Hake’s normalized gain |

| REACT | Relate, Experience, Apply, Cooperate, Transfer |

| 5Es | Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate. |

References

- Araújo, F., & Sampaio, C. (2022). Formação continuada de professores em ensino de química à luz da abordagem CTSA: Uma análise bibliográfica. Research, Society and Development, 11, e21111931844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J. L., Morais, C., & Paiva, J. C. (2015). Poetry and alkali metals: Building bridges to the study of atomic radius and ionization energy. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 16(4), 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J. L., Morais, C., & Paiva, J. C. (2023a). Citizen science in promoting chemical-environmental awareness of students in the context of marine pollution by (micro)plastics. Revista Electrónica Educare, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J. L., Morais, C., & Paiva, J. C. (2023b). Students’ attitudes towards the environment and marine litter in the context of a coastal water quality educational citizen science project. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 39(4), 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres-Pereira, T. I., Marcondes, M. E. R., & do Carmo, M. P. (2024). Training needs and conceptions about context-based teaching of a group of chemistry teachers. São Paulo University, Encontro Nacional de Pesquisa em Educação em Ciências. [Google Scholar]

- Bencze, L., Pouliot, C., Pedretti, E., Simonneaux, L., Simonneaux, J., & Zeidler, D. (2020). SAQ, SSI and STSE education: Defending and extending “science-in-context”. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15, 825–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B. S., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1969). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. David McKay. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books?id=VhScAAAAMAAJ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Cachichi, R., Camejo, I., Barbosa, M., Morais, C., Girotto Junior, G., & Galembeck, E. (2025). A new proposal for inquiry activity using a low-cost remote acid–base titration. Journal of Chemical Education, 102, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, L. (2012). Chemistry: Why the subject is difficult? Educación Química, 23(1–6), 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhosa, I. (2015). Aprendizagem do tema ácidos e bases através de uma abordagem CTSA [Master’s thesis, Universidade de Lisboa]. [Google Scholar]

- Doney, S. C., Busch, D. S., Cooley, S. R., & Kroeker, K. J. (2020). The impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and reliant human communities. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 83–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffoni, J. d. S., Barroso, M. C. d. S., & Sampaio, C. d. G. (2020). Significant learning in chemistry teaching: A science, technology and society approach. Research, Society and Development, 9(6), e13963416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grennfelt, P., Engleryd, A., Forsius, M., Hov, Ø., Rodhe, H., & Cowling, E. (2020). Acid rain and air pollution: 50 years of progress in environmental science and policy. Ambio, 49(4), 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulacar, O., Zowada, C., & Eilks, I. (2018). Bringing chemistry learning back to life and society. In Building bridges across disciplines for transformative education and a sustainable future (pp. 49–60). Shaker. [Google Scholar]

- Gunbatar, S. A., Kiran, B. E., Boz, Y., & Oztay, E. S. (2025). A systematic review of green and sustainable chemistry training research with pedagogical content knowledge framework: Current trends and future directions. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 26(1), 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hake, R. (1998). Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: A six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. American Journal of Physics, 66, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M. H., Kasim, S., Ahmed, O. H., Mohd. Rakib, M. R., Hasbullah, N. A., & Islam Shajib, M. T. (2024). Impact of simulated acid rain on chemical properties of Nyalau series soil and its leachate. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R., Yin, M., Feng, X., Chen, C., Qu, C., Liu, L., Li, P., & Li, Z.-H. (2024). Ocean acidification alters shellfish-algae nutritional value and delivery. Science of The Total Environment, 918, 170841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Liso, M. R., López-Banet, L., & Dillon, J. (2020). Changing how we teach acid-base chemistry: A proposal grounded in studies of the history and nature of science education. Science and Education, 29(5), 1291–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M. (2018). Effects of nature training projects on environmental perception and attitudes. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 16, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortam, N., Basheer, A., Abu Much, R., & Hamed, Y. (2025). High school chemistry teachers’ attitudes toward incorporating environmental education topics into the chemistry curriculum in Israel. Chemistry Teacher International, 7(4), 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Lee, H., & Zeidler, D. L. (2020). Examining tensions in the socioscientific issues classroom: Students’ border crossings into a new culture of science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57, 672–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Chen, J. (2019). Modified two major environmental values scale for measuring Chinese children’s environmental attitudes. Environmental Education Research, 26(1), 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F. (2009). Desenvolvimento e implementação de uma abordagem CTSA do conceito de acidez no ensino da física e química. Universidade de Évora. [Google Scholar]

- Meenakshipriya, B., Saravanan, K., Shanmugam, R., & Sathiyavathi, S. (2009). Study of pH system in common effluent treatment plant. Modern Applied Science, 2, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T., & Duckitt, J. (2010). The environmental attitudes inventory: A valid and reliable measure to assess the structure of environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H. (2019). Acid rain is a local environment pollution but global concern. Open Science Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, M. H., & Zeidler, D. L. (2020). Developing socioscientific perspective taking. International Journal of Science Education, 42(8), 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, J., Morais, C., & Moreira, L. (2013). Specialization, chemistry, and poetry: Challenging chemistry boundaries. Journal of Chemical Education, 90, 1577–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, J., Morais, C., & Moreira, L. (2017). Activities with parents on the computer: An ecological framework. Journal of Education Technology & Society, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pedretti, E., & Bellomo, K. (2013). A time for change: Advocating for STSE education through professional learning communities. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 13(4), 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, E., & Nazir, J. (2011). Currents in STSE education: Mapping a complex field, 40 years on. Science Education, 95, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyambodo, E., Fitriyana, N., Primastuti, M., & Aquarisco, F. (2021). The role of collaborative learning based STSE in acid base chemistry: Effects on students’ motivation. In Proceedings of the 7th international conference on research, implementation, and education of mathematics and sciences (ICRIEMS 2020). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., & Ahammed, M. M. (2023). Application of modified water treatment residuals in water and wastewater treatment: A review. Heliyon, 9(5), e15796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F. (2020). As abordagens CTS/CTSA e alguns desafios atuais do ensino de ciências. In Educação para a ciência e CTS: Um olhar interdisciplinar (p. 11). Texto e Contexto. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, R., Rietz, F., & Büchel, D. (2025). Using the socioscientific issue approach to foster secondary students’ argumentation skills, science self-efficacy beliefs and science interest. International Journal of Science Education, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitha, N., Zhang, Y., Pazicni, S., Fullington, S., Morais, C., Buchberger, A., & Doolittle, P. (2024). Supporting submicroscopic reasoning in students’ explanations of absorption phenomena using a simulation-based activity. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 25(1), 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. A., Williams, B., LaVigne, M., Wanamaker, A. D., Strong, A. L., Jellison, B., Whitney, N. M., Thatcher, D. L., Robinson, L. F., Halfar, J., & Adey, W. (2025). Delayed onset of ocean acidification in the Gulf of Maine. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swirski, H., Baram Tsabari, A., & Yarden, A. (2018). Does interest have an expiration date? An analysis of students’ questions as resources for context-based learning. International Journal of Science Education, 40, 1136–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towns, M. H. (2008). Mixed methods designs in chemical education research. In Nuts and bolts of chemical education research (Vol. 976, pp. 135–148). American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ültay, N., & Çalik, M. (2016). A comparison of different teaching designs of ‘acids and bases’ subject. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 12, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M., Morais, C., & Paiva, J. C. (2025). Inquiry-based science education in high chemistry: Enhancing oral and written communication skills through authentic and problem-based learning activities. Education Sciences, 15(3), 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiyarsi, A., Pratomo, H., & Priyambodo, E. (2020). Vocational high school students’ chemical literacy on context-based learning: A case of petroleum topic. Journal of Turkish Science Education, 17, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wang, J., Wang, S., Wang, C., Yang, F., & Li, T. (2024). Chemical characteristics of long-term acid rain and its impact on lake water chemistry: A case study in Southwest China. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 138, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, S., Fan, S., Wu, Y., Hu, H., Feng, Z., Huang, Z., Liang, J., & Qin, Y. (2021). A stepwise processing strategy for treating highly acidic wastewater and comprehensive utilization of the products derived from different treating steps. Chemosphere, 280, 130646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.