Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Generated Summaries on Video-Based Learning: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cognitive Load Theory’s Guidance for Online Video Learning Design

2.2. Forms and Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Assisted Video Learning

3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- Pedagogical Agent-Generated Mind Map Summary Group (PA-MMS): Presenting knowledge relationships in a graphical format;

- Pedagogical Agent-Generated Text Summary Group (PA-TS): Presenting core knowledge points following principles of conciseness;

- Non-Pedagogical Agent Summary Generation Group (NPA): Presenting only original video content.

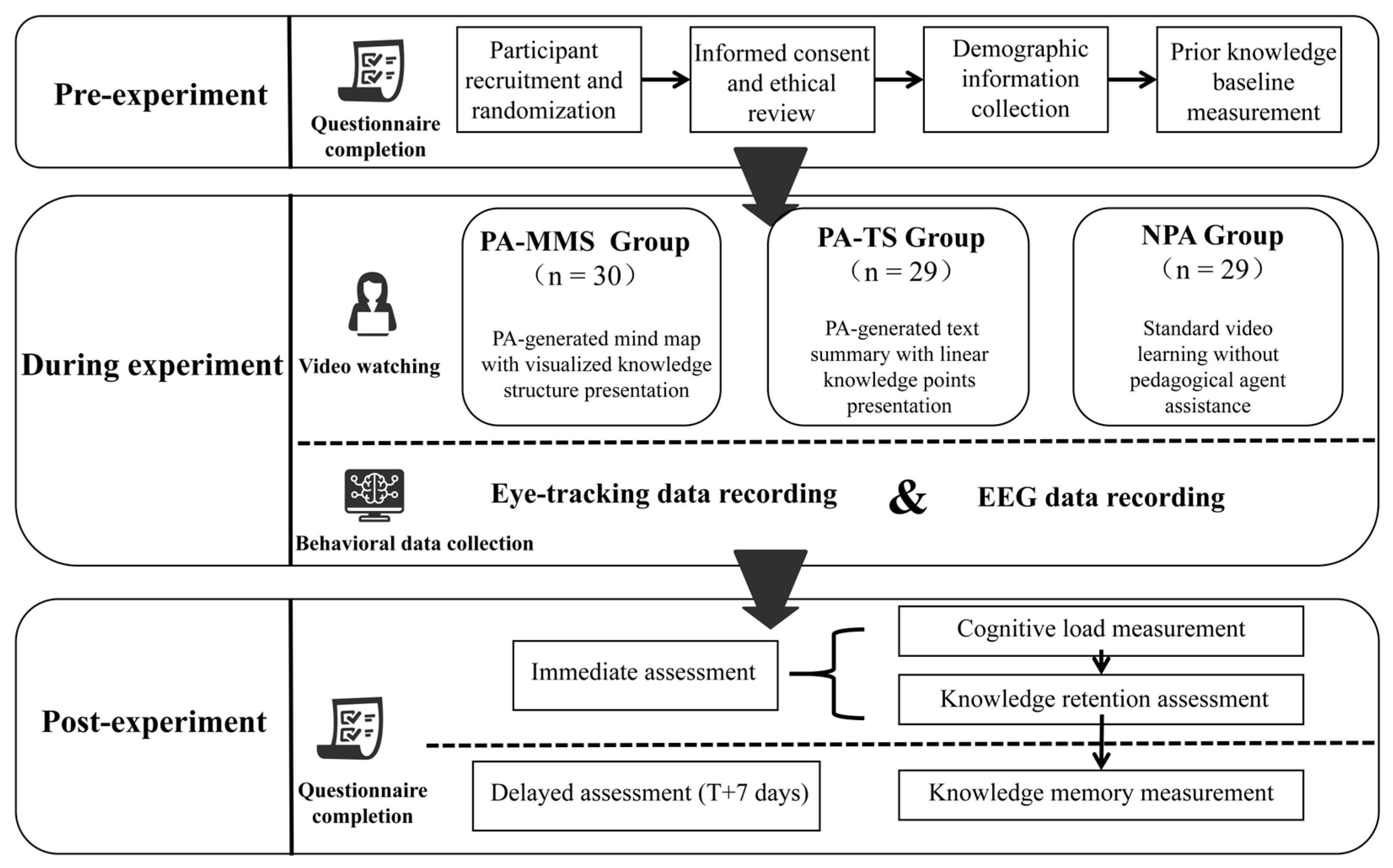

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measurement Indicators

4.3. Experimental Procedure

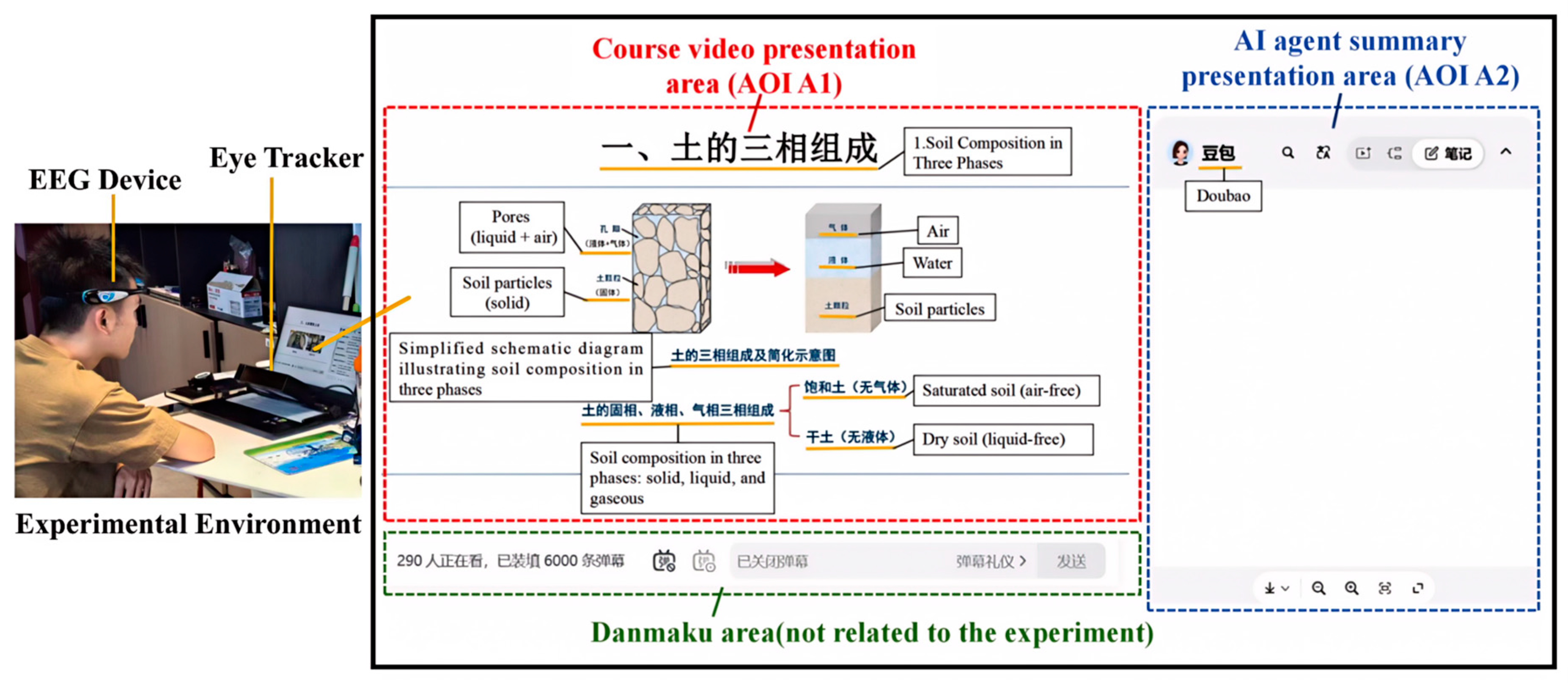

4.3.1. Experimental Materials and Pedagogical Agent System Setup

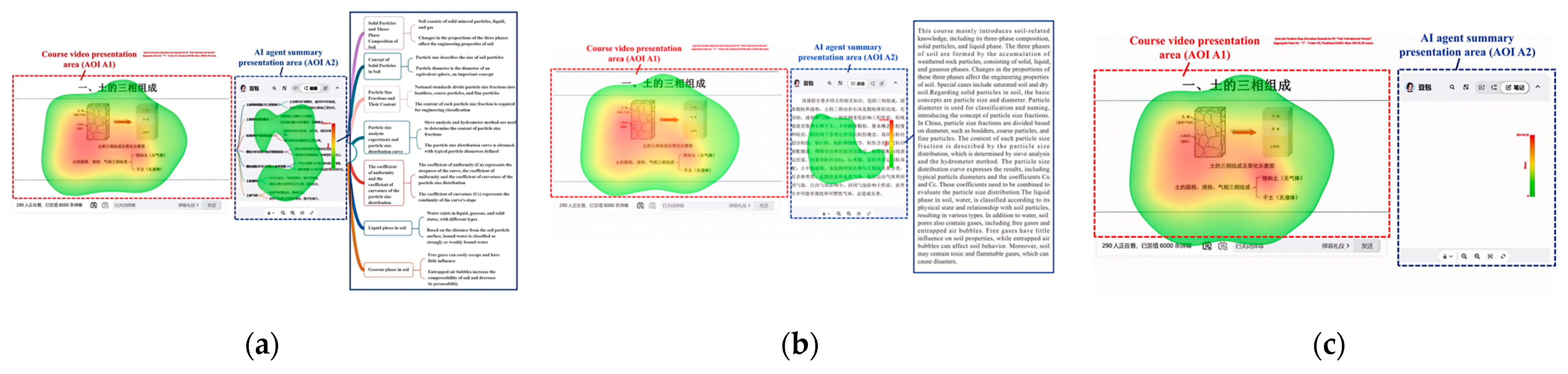

- PA-MMS Group: While participants watched the video, the right side of the interface synchronously displayed the pedagogical agent-generated mind map summary, visualizing logical relationships between knowledge points through hierarchical structures and node connections (Figure 2a).

- PA-TS Group: While participants watched the video, the right side of the interface synchronously displayed the pedagogical agent-generated text summary, presenting the same knowledge points in a linear paragraph format (Figure 2b).

- NPA Group: Participants only watched the video content, with the right side of the interface remaining blank, providing no supplementary summary.

4.3.2. Experimental Implementation and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Learning Performance

5.2. Cognitive Load Analysis

5.3. Neurophysiological Indices

5.3.1. EEG Activity Patterns

5.3.2. Visual Attention Allocation

5.4. Multivariate Correlation Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Mechanisms of Pedagogical Agents’ Impact on Learning Performance

6.2. Optimization Mechanisms and Differentiated Regulation of Cognitive Load

6.3. Attention Allocation Patterns and Information Processing Strategies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AlShaikh, R., Al-Malki, N., & Almasre, M. (2024). The implementation of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning in the design and evaluation of an AI educational video assistant utilizing large language models. Heliyon, 10(3), e25361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonenko, P., Paas, F., Grabner, R., & Van Gog, T. (2010). Using electroencephalography to measure cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22(4), 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, M., Ochs, M., & Régner, I. (2022). The impact of pedagogical agents’ gender on academic learning: A systematic review. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 5, 862997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R., Harley, J., Trevors, G., Duffy, M., Feyzi-Behnagh, R., Bouchet, F., & Landis, R. (2013). Using trace data to examine the complex roles of cognitive, metacognitive, and emotional self-regulatory processes during learning with multi-agent systems. In R. Azevedo, & V. Aleven (Eds.), International handbook of metacognition and learning technologies (pp. 427–449). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Baidoo-Anu, D., & Ansah, L. O. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Journal of AI, 7(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen, M., Magyari, L., & Hagoort, P. (2012). Syntactic unification operations are reflected in oscillatory dynamics during on-line sentence comprehension. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(7), 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromik, M., Eiband, M., Völkel, S. T., & Buschek, D. (2019, March 20). Dark patterns of explainability, transparency, and user control for intelligent systems. IUI Workshops (Vol. 2327), Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y., Liu, A., & Lim, C. P. (2023). Reconceptualizing ChatGPT and generative AI as a student-driven innovation in higher education. Procedia CIRP, 119, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L., Tang, X., & Wang, J. (2025). Different types of textual cues in educational animations: Effect on science learning outcomes, cognitive load, and self-efficacy among elementary students. Education and Information Technologies, 30(3), 3573–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X., & Cukurova, M. (2023). Exploring the effects of “AI-generated” discussion summaries on learners’ engagement in online discussions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, Tokyo, Japan, July 3–7 (pp. 155–161). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyönä, J., Lorch, R. F., Jr., & Rinck, M. (2003). Eye movement measures to study global text processing. In J. Hyönä, R. Radach, & H. Deubel (Eds.), The mind’s eye: Cognitive and applied aspects of eye movement research (pp. 313–334). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Jamet, E. (2014). An eye-tracking study of cueing effects in multimedia learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 32, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarodzka, H., Van Gog, T., Dorr, M., Scheiter, K., & Gerjets, P. (2013). Learning to see: Guiding students’ attention via a model’s eye movements fosters learning. Learning and Instruction, 25, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. L., & Lester, J. C. (2016). Face-to-face interaction with pedagogical agents, twenty years later. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory: How many types of load does it really need? Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., Hüllermeier, E., Krusche, S., Kutyniok, G., Michaeli, T., Nerdel, C., Pfeffer, J., Poquet, O., Sailer, M., Schmidt, A., Seidel, T., … Kasneci, G. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. (1999). EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Research Reviews, 29(2–3), 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M. L., Tsai, M. J., Yang, F. Y., Hsu, C. Y., Liu, T. C., Lee, S. W. Y., Lee, M. H., Chiou, G. L., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2013). A review of using eye-tracking technology in exploring learning from 2000 to 2012. Educational Research Review, 10, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, W., & Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory, modality of presentation and the transient information effect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(6), 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppink, J., Paas, F., Van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Van Gog, T., & Van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2013). Development of an instrument for measuring different types of cognitive load. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutner, D., Leopold, C., & Sumfleth, E. (2009). Cognitive load and science text comprehension: Effects of drawing and mentally imagining text content. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Ji, Y., & Zhan, Z. (2024). Expert or machine? Comparing the effect of pairing student teachers with in-service teachers and ChatGPT on their critical thinking, learning performance, and cognitive load in an integrated STEM course. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 44(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Chen, S., Cheng, H., Liu, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2024, May 11–16). How AI processing delays foster creativity: Exploring research question co-creation with an LLM-based agent. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–25), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q., Shen, H., Koedinger, K., & Tomkins, S. (2024). How to teach programming in the AI era? Using LLMs as a teachable agent for debugging. In Proceedings of the international conference on artificial intelligence in education (pp. 265–279). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Mangaroska, K., Sharma, K., Gašević, D., & Giannakos, M. (2022). Exploring students’ cognitive and affective states during problem solving through multimodal data: Lessons learned from a programming activity. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2017). Using multimedia for e-learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 33(5), 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2013). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. U.S. Department of Education.

- Mutlu-Bayraktar, D., Cosgun, V., & Altan, T. (2019). Cognitive load in multimedia learning environments: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 141, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H. K., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2013). Reducing transience during animation: A cognitive load perspective. Educational Psychology, 33(7), 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J. D. (2010). Learning, creating, and using knowledge: Concept maps as facilitative tools in schools and corporations. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. R., Koka, R. S., Shah, S. K., & Subramanian, V. (2024). Enhancing lecture video navigation with AI generated summaries. Education and Information Technologies, 29(6), 7361–7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiter, K., & Eitel, A. (2015). Signals foster multimedia learning by supporting integration of highlighted text and diagram elements. Learning and Instruction, 36, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. M., Marcus, N., & Ayres, P. (2012). The transient information effect: Investigating the impact of segmentation on spoken and written text. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(6), 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M., Kelly, A., & McLaughlan, P. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowska, A., Ragni, V., Szkriba, S., & Gerber-Morón, O. (2024). Watching subtitled videos with the sound off affects viewers’ comprehension, cognitive load, immersion, enjoyment, and gaze patterns: A mixed-methods eye-tracking study. PLoS ONE, 19(10), e0306251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursutiu, D., Samoilă, C., Drăgulin, S., & Auer, M. E. (2018). Investigation of music and colours influences on the levels of emotion and concentration. In M. E. Auer, & D. G. Zutin (Eds.), Online engineering & internet of things (pp. 910–918). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gog, T., & Scheiter, K. (2010). Eye tracking as a tool to study and enhance multimedia learning. Learning and Instruction, 20(2), 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahn, B., Schmitz, L., Gerster, F. N., & Weiss, M. (2023). Offloading under cognitive load: Humans are willing to offload parts of an attentionally demanding task to an algorithm. PLoS ONE, 18(5), e0286102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C. D. (2002). Multiple resources and performance prediction. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 3(2), 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A., Leahy, W., Marcus, N., & Sweller, J. (2012). Cognitive load theory, the transient information effect and e-learning. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. H., & Viberg, O. (2024). Unpacking students’ interaction patterns in asynchronous online discussions: A learning analytics approach. Computers & Education, 199, 104785. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, M., & Jennings, N. R. (1995). Intelligent agents: Theory and practice. The Knowledge Engineering Review, 10(2), 115–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R., & Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G. (2023). The effect of generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based tool use on students’ computational thinking skills, programming self-efficacy and motivation. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Zhao, J. L., Zhou, L., & Nunamaker, J. F., Jr. (2006). Can e-learning replace classroom learning? Communications of the ACM, 47(5), 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | PA-MMS Group (M ± SD) | PA-TS Group (M ± SD) | NPA Group (M ± SD) | F(2, 77) | p | qFDR | η2 | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttest Score | 11.85 ± 1.09 | 10.39 ± 1.23 | 7.10 ± 1.41 | 42.37 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.524 | 3.78 [3.05, 4.51] |

| Learning Gain | 8.15 ± 1.52 | 6.56 ± 1.68 | 3.24 ± 1.94 | 36.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.489 | 2.81 [2.18, 3.44] |

| Posttest Accuracy Rate (%) | 84.60 ± 7.80 | 74.20 ± 8.80 | 50.70 ± 10.10 | 50.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.566 | 3.78 [3.05, 4.51] |

| Retention Test Score | 12.30 ± 0.80 | 10.20 ± 1.40 | 8.30 ± 1.50 | 42.80 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.526 | 3.21 [2.53, 3.89] |

| Retention Rate (%) | 96.80 ± 6.00 | 92.20 ± 8.00 | 87.00 ± 9.00 | 6.52 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.145 | 1.28 [0.71, 1.85] |

| Forgetting Amount | 0.55 ± 0.83 | 1.18 ± 1.32 | 1.92 ± 1.48 | 21.40 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.357 | 1.09 [0.53, 1.65] |

| Category | PA-MMS Group (M ± SD) | PA-TS Group (M ± SD) | NPA Group (M ± SD) | F(2, 77) | p | qFDR | η2 | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICL | 2.85 ± 0.71 | 3.18 ± 0.68 | 3.52 ± 0.63 | 7.32 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.160 | 0.99 [0.44, 1.54] |

| ECL | 2.42 ± 0.59 | 2.78 ± 0.64 | 3.25 ± 0.72 | 10.47 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.214 | 1.26 [0.70, 1.82] |

| GCL | 3.68 ± 0.52 | 3.45 ± 0.58 | 3.02 ± 0.61 | 8.21 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.176 | 1.15 [0.59, 1.71] |

| ATT | 3.75 ± 0.48 | 3.82 ± 0.51 | 3.31 ± 0.55 | 4.12 | 0.020 | 0.008 | 0.097 | 0.81 [0.26, 1.36] |

| TIME | 2.88 ± 0.66 | 3.34 ± 0.71 | 3.65 ± 0.78 | 9.85 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.204 | 1.08 [0.52, 1.64] |

| Category | PA-MMS Group (M ± SD) | PA-TS Group (M ± SD) | NPA Group (M ± SD) | F(2, 77) | p | qFDR | η2 | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theta Wave Ratio (%) | 14.35 ± 3.28 | 15.87 ± 3.51 | 18.92 ± 3.86 | 10.28 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.211 | 1.28 [0.71, 1.85] |

| Alpha Wave Ratio (%) | 18.76 ± 4.15 | 16.42 ± 3.89 | 14.38 ± 3.72 | 7.84 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.169 | 1.10 [0.54, 1.66] |

| Beta Wave Ratio (%) | 15.23 ± 3.42 | 17.68 ± 3.78 | 13.85 ± 3.21 | 6.54 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.145 | 0.42 [−0.11, 0.95] |

| Gamma Wave Ratio (%) | 2.58 ± 1.12 | 3.50 ± 1.35 | 2.31 ± 0.98 | 5.89 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.133 | 0.25 [−0.28, 0.78] |

| Category | PA-MMS Group (M ± SD) | PA-TS Group (M ± SD) | NPA Group (M ± SD) | F(2, 77) | p | qFDR | η2 | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOI A2 Fixation Time Percentage (%) | 12.40 ± 5.70 | 14.80 ± 6.90 | 0.80 ± 0.90 | 43.90 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.533 | 2.56 [1.89, 3.23] |

| AOI A2 Fixation Time (ms) | 56,318 ± 25,914 | 65,129 ± 31,206 | 3320 ± 3710 | 38.45 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.500 | 2.43 [1.77, 3.09] |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttest Score | — | ||||||||||

| Learning Gain | 0.95 *** | — | |||||||||

| Retention Test Score | 0.89 *** | 0.82 *** | — | ||||||||

| Forgetting Amount | −0.76 *** | −0.68 *** | −0.84 *** | — | |||||||

| ICL | −0.52 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.45 *** | 0.41 ** | — | ||||||

| ECL | −0.61 *** | −0.58 *** | −0.52 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.68 *** | — | |||||

| GCL | 0.54 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.58 *** | −0.49 *** | −0.42 ** | −0.51 *** | — | ||||

| Theta Wave Ratio (%) | −0.46 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.41 ** | 0.51 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.64 *** | −0.38 ** | — | |||

| Theta Wave Ratio (%) | 0.39 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.42 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.41 ** | 0.47 *** | −0.52 *** | — | ||

| AOI A2 Fixation Time (ms) | 0.68 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.59 *** | −0.54 *** | −0.45 *** | −0.53 *** | 0.56 *** | −0.48 *** | 0.44 *** | — | |

| TIME | −0.55 *** | −0.51 *** | −0.48 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.71 *** | −0.44 *** | 0.59 *** | −0.38 ** | −0.49 *** | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, L.; Xu, J.; Zhan, Z. Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Generated Summaries on Video-Based Learning: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010039

Yuan L, Xu J, Zhan Z. Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Generated Summaries on Video-Based Learning: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Lei, Jiyuan Xu, and Zehui Zhan. 2026. "Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Generated Summaries on Video-Based Learning: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010039

APA StyleYuan, L., Xu, J., & Zhan, Z. (2026). Effects of Pedagogical Agent-Generated Summaries on Video-Based Learning: Evidence from Eye-Tracking and EEG. Education Sciences, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010039