Abstract

Teachers’ language assessment literacy (LAL) encompasses the knowledge and competencies required to design and implement assessment practices that support learning. Although prior research has documented general trends in LAL development, less is known about how individual teachers, particularly student teachers, interpret, appropriate, and negotiate formative assessment (FA) task design within the context of initial teacher education (ITE). Adopting an in-depth qualitative case study approach, this study examines how a single student teacher in a Chinese initial teacher education developed her cognition and classroom practice related to FA tasks across a teaching methodology course and a practicum. Drawing on thematic analysis of semi-structure interviews, lesson plans, classroom observations, stimulated recall interviews, and reflective journals, the study traces developmental changes and the contextual factors shaping the student teacher’s LAL in relation to FA tasks. Findings show that the sustained engagement with FA task design supported more sophisticated understandings of FA, including (1) an increased recognition of the pedagogical necessity of incorporating authentic FA tasks into lesson planning, (2) a growing aspiration to implement FA-oriented instruction that promotes higher-order thinking, (3) an enhanced awareness of the empowering role of FA tasks in fostering students’ self-regulated learning, and (4) a more nuanced understanding of the challenges inherent in implementing FA practices. Meanwhile, the case illustrates how pre-existing assessment conceptions, school culture norms, and limited targeted mentoring can constrain LAL development in relation to FA. By providing a fine-grained account of developmental processes, this study offers insights into how ITE can mediate student teachers’ engagement with FA task design. The findings have implications for teacher education programs in other similar educational contexts, particularly regarding the integration of FA task design into assessment courses and the provision of sustained, context-sensitive support during teaching practicum.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the concept of assessment literacy has become increasingly complex and dynamic due to a paradigm shift from cognitive views of learning and psychometric testing to social–constructivist views of learning and authentic assessment (Stiggins, 2017; Shepard, 2000). In language teaching and learning, it is increasingly acknowledged that without appropriate language assessment literacy (LAL), the quality of language teaching is affected (L. Gan & Lam, 2022; Giraldo, 2018). One aspect of LAL, the skills to develop formative assessment (FA) tasks, has been recognized as a key component in professional development for language teachers (K. H. Koh, 2011). Given the crucial role of language teachers in the development of assessments within their local curricular contexts, it is essential to examine how teachers acquire the competencies necessary for creating effective assessments (Dimova et al., 2020; Jin, 2010; Taylor, 2013). This concern is particularly salient for student teachers, who are expected to engage with innovative teaching and assessment approaches in increasingly complex and challenging teaching environments (Giraldo & Murcia Quintero, 2019; Pardo et al., 2024). While prior research has documented generally insufficient levels of student teachers’ assessment literacy, including limitations in their assessment knowledge and self-efficacy for implementing effective assessment practices (Xie & Cui, 2021; Xu & He, 2019), comparatively little scholarly attention has been devoted to the development of their LAL, particularly with regard to their engagement in the design of FA tasks (J. D. Brown & Bailey, 2008).

Against this backdrop, scholars have issued a clear call to action, underscoring that initial teacher education (ITE) represents a formative period during which assessment conceptions, knowledge, and practices can be systematically shaped (Giraldo & Murcia Quintero, 2019; Z. Yan et al., 2021). Supporting student teachers’ engagement with FA during ITE is arguably timelier than introducing it later in their career when they may have become accustomed to established school practices. Their direct experiences with innovative pedagogy and assessment approaches could exert a lasting influence on their professional development (Xie & Cui, 2021). Accordingly, there is growing recognition that ITE should move beyond an exclusive focus on theoretical foundations to incorporate practical, experience-based training alongside sustained engagement with assessment practice (Allen & Wright, 2014; Levy-Vered & Alhija, 2018). Such training includes opportunities for student teachers to design, implement, and reflect on assessment activities, as well as to examine the sociocultural, institutional, and personal factors that shape assessment practices (Fernández Ruiz et al., 2021).

Recent research on student teachers’ LAL has revealed notable gaps in both their theoretical understanding of assessment and their skills in implementing effective assessment practices (Maclellan, 2004; Pastore, 2024). It has been argued that many student teachers are insufficiently prepared to integrate assessment meaningfully into their teaching (K. H. Koh, 2011; Allen & Wright, 2014). Consequently, several theoretical frameworks for teacher assessment competence have been proposed, emphasizing not only the necessity of a solid theoretical foundation in key assessment principles but also the influence of contextual and individual factors on assessment practices (Giraldo, 2018; Xie & Cui, 2021). Developing advanced assessment literacy in ITE is therefore essential for student teachers, as it enables them to effectively bridge the gap between assessment theory and classroom practice upon entering the profession (Pastore, 2024). Consequently, it becomes imperative to examine how ITE programs and teaching practicum experiences influence the development of student teachers’ assessment conceptions and the enactment of their assessment practices (Charteris & Dargusch, 2018; Chen & Cowie, 2016).

Previous research examining student teachers’ LAL has focused on two interrelated strands. First, a number of studies have highlighted student teachers’ strong desire to acquire the theoretical knowledge and skills necessary to design effective language assessments (K. H. Koh, 2011; Xie & Cui, 2021; Pardo et al., 2024). Second, there is increasing evidence that student teachers express an urgent need for classroom-based assessment practices that are both practical and contextually relevant (Giraldo, 2018; Konadu, 2025; Lin et al., 2021). While some studies have provided valuable insights into the theoretical gains achieved through formal instruction, relatively little attention has been directed toward understanding the development of the task design aspect of LAL (K. H. Koh, 2011). This gap is particularly significant given that the ability to design valid, reliable, and pedagogically meaningful assessment tasks is a critical component of teachers’ professional competence. Addressing this underexplored area is essential for bridging the divide between assessment theory and classroom practice in ITE. As such, the present study seeks to contribute to this body of research by investigating how a EFL student teacher engaged in the design of FA tasks for K-12 learners, with particular attention to the assessment conceptions, processes, practices and challenges involved. There are two questions guiding the research.

- How does the student teacher experience FA task design and how does this experience relate to LAL development?

- What personal, contextual and institutional factors influence the student teacher’s LAL development?

2. Student Teachers’ Language Assessment Literacy

LAL has emerged as a critical area of focus in teacher education, reflecting the growing recognition that teachers require a well-rounded understanding of assessment principles to make informed pedagogical decisions (Cirocki et al., 2025; Tsagari & Vogt, 2017). Broadly defined, LAL encompasses a combination of knowledge, skills, and principles that enable teachers to design, implement, and interpret language assessments effectively (DeLuca & Braund, 2019). While existing conceptualization of LAL have provided valuable insights into the competencies required of language teachers, they tend to offer generalized representations that may not fully capture the developmental needs of student teachers (Chen & Cowie, 2016). For those teacher candidates, the development of LAL is not only foundational to their future professional competence, but also instrumental in fostering a deeper understanding of the pivotal role assessment plays in effective teaching (Lin et al., 2021). A well-developed LAL enables student teachers to appreciate assessment as an integral component of instruction—one that supports potential student learning and progress through the application of valid, formative, and pedagogically sound assessment practices (Lin et al., 2021; G. T. L. Brown & Remesal, 2012; Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000; Pastore & Andrade, 2019).

Much of the existing literature on student teachers’ LAL has shown that assessment-related courses can enhance conceptual assessment knowledge and foster more positive beliefs about the role of assessment in language learning (Levy-Vered & Alhija, 2018). For instance, Giraldo and Murcia designed and implemented a course grounded in stakeholder perspectives, which drew attention to national assessment policies and facilitated the development of both theoretical and practical dimensions of LAL, particularly in relation to task design (Giraldo & Murcia Quintero, 2019). Similarly, Lam advocated for practicum-based coursework that explicitly targets LAL knowledge, skills, and principles, suggesting the use of observation protocols and reflective portfolios as mechanisms to support student teachers’ engagement with and reflection on assessment practices (Lam, 2015). Restrepo further demonstrated that reflective tools such as learning journals enabled student teachers to conceptualize and critically reflect on the various components of LAL, thereby promoting a more comprehensive understanding of language assessment concepts and classroom applications (Restrepo, 2020).

However, compared to in-service teachers, student teachers often face greater challenges in translating abstract theoretical knowledge into effective classroom assessment practices, particularly within the complex and dynamic realities of real-world teaching (Xu & He, 2019; Cirocki et al., 2025). These challenges are heightened when addressing diverse learner needs, navigating institutional expectations, and managing time constraints (Tsagari & Vogt, 2017; Looney et al., 2018). This suggests that foundational knowledge of assessment principles and frameworks does not necessarily lead to the successful implementation of formative assessment in practice (Shao, 2025). This gap between conceptual understanding and situated practice can result in a relatively narrow conception of assessment, particularly among Chinese student teachers who often enter teacher education programs with deeply ingrained, test-oriented perceptions shaped by their own assessment experiences (Xie & Cui, 2021; Chen & Cowie, 2016; Chen & Brown, 2013). In the absence of practical engagement, student teachers may find it difficult to appreciate the complexity of aligning assessment practices with instructional goals and learner needs. Therefore, it is a pressing priority in teacher education to support student teachers in internalizing the dynamic and context-dependent nature of assessment processes, while simultaneously fostering the pedagogical intentionality necessary for conducting effective assessment (K. Koh et al., 2017).

Another notable limitation in the literature is the lack of attention to how student teachers learn to design their own assessment tasks. While some studies have examined the use of pre-designed tools or rubrics (Scarino, 2013), few have addressed how student teachers conceptualize and construct FA activities that align with instructional goals and learner needs. Designing assessment tasks requires not only knowledge of content and pedagogy but also the ability to make context-sensitive decisions regarding purpose of assessment and instructional goals (Brookhart, 2011). For student teachers in particular, these decisions are often complicated by limited classroom experience, a lack of confidence, and competing curricular expectations (Coombs et al., 2020). As such, task design represents a key but under-researched area of LAL development that deserves more focused inquiry.

In response to these challenges, recent scholarship has begun to advocate for more practice-informed approaches to fostering LAL among student teachers. This includes integrating opportunities for authentic task development (Xu & He, 2019; K. Koh et al., 2017), collaborative feedback (Shao, 2025), and critical reflection on the relationship between assessment and instruction (Looney et al., 2018; X. Yan & Fan, 2020). In the context of FA, the capacity to design effective FA tasks should be recognized as a core component of student teachers’ LAL, given the pivotal role that FA plays in promoting learner self-regulation and engagement (Pastore et al., 2019). As the field of teacher education continues to evolve, there is a growing need for empirical research to investigate how ITE can meaningfully scaffold the development of this complex and practice-oriented dimension of LAL.

3. Understanding Formative Assessment Task

FA has been widely acknowledged as a critical element in effective teaching and learning, particularly for its potential to support students’ ongoing development and inform instructional decision-making (Black & Wiliam, 2009; Carless, 2007). Unlike summative assessment (SA), which primarily aims to evaluate learning outcomes at the end of an instructional unit, FA is embedded in the learning process and emphasizes continuous feedback, student involvement, and instructional adjustment (Heritage, 2007). Guided by Gu’s FA framework, FA can be conceptualized as a cyclical process, comprising planning assessment, collecting evidence, interpreting evidence, providing feedback and adjusting teaching (Gu & Lam, 2023). In the current study, greater emphasis is placed more on the planning stage, as for student teachers the first and potentially most critical step in developing their LAL in relation to FA may lie in learning to design appropriate FA tasks and integrate them into their instructional practices.

The design and implementation of FA tasks require student teachers to possess a relatively deep understanding of assessment principles and strategies that align with pedagogical goals and learner needs (Atjonen et al., 2024). However, most Chinese student teachers have been educated in an environment where assessment is predominantly associated with large-scale, high-stakes examinations (Xu & He, 2019; Shao, 2025). Such an assessment culture positions these student teachers at a disadvantage, as their prior experiences have been shaped by SA practices. Consequently, they are likely to encounter greater difficulties when expected to conceptualize, design and implement FA in teaching contexts (Lin et al., 2021).

While FA has gained increasing recognition for its potential to enhance student learning and support instructional decision-making, existing literature reveals that insufficient attention has been paid to the quality and design of the assessment tasks themselves (Bennett, 2011; Villarroel et al., 2018). Much of the emphasis in both research and practice has focused on broader aspects of FA such as feedback, learner engagement, and assessment for learning (AfL) principles, while the actual construction of tasks that elicit meaningful evidence of learning has remained underexplored (Pastore et al., 2019).

In the context of language assessment, the integration of authenticity into language assessment design has long been emphasized (Bachman, 2024). Authentic assessment typically incorporates open-ended performance tasks that allow students to demonstrate capabilities such as knowledge production, extended communication, higher-order thinking and creative problem solving (K. Koh et al., 2017). Building on Bachman’s framework, two interrelated dimensions of authenticity—situational authenticity and interactional authenticity—are particularly relevant to the design of FA tasks. Situational authenticity pertains to the degree of correspondence between the features of a language task and the conditions of real-world language use, often referred to as the “fit” between the assessment task and the target language situation. Interactional authenticity refers to the extent to which learners can meaningfully engage with a task using their full range of language abilities (Lewkowicz, 2000). It involves not only the activation of linguistic skills but also the cognitive and affective engagement of the learner in task performance (Bachman, 2024).

In the context of FA in language teaching, teachers are therefore expected to design authentic FA tasks that enable students to meaningfully apply their linguistic knowledge, proficiency and communicative competence in anticipated real-world uses of the target language (Park, 2024; Z. Gan & Leung, 2020). From this perspective, authentic assessment tasks need to be designed to be realistic and contextually grounded, replicating the kinds of communicative or problem-solving situations that learners may encounter in professional or everyday contexts (K. Koh et al., 2017). However, authenticity in assessment extends beyond the surface simulation of real-world tasks. It also involves the deliberate creation of learning experiences that require students to engage actively and meaningfully with content, thereby fostering deeper cognitive and metacognitive engagement. Empirical studies show student teachers reported practical challenges with task design and implementation (Atjonen et al., 2024; Xie & Cui, 2021). These challenges include difficulties in aligning assessment tasks with instructional objectives, operationalizing formative assessment principles in classroom practice, and responding effectively to learners’ needs in real time. Given mounting evidence that this group experiences substantial difficulties in designing and implementing FA tasks, research focusing on their task design and implementation is both necessary and timely.

4. Methodology

As Ebneyamini and Sadeghi Moghadam (2018) suggest, case studies serve as a valuable methodological approach for examining complex educational practices within authentic classroom contexts. This study employed a single-case study design (R. K. Yin, 2014), focusing on the design and implementation of FA tasks and the development of the student teacher’s LAL. A single-case study was selected to allow for an in-depth, contextually rich exploration of how one student teacher conceptualized, designed, adapted and implemented FA tasks over time. While broader patterns across teachers are informative, a single-case design enables a nuanced analysis of the specific developmental trajectory, challenges, and contextual factors shaping one individual’s engagement with FA practices. This approach facilitated a detailed understanding of the evolving nature of the participant’s assessment task design and implementation, as well as the contextual influences that affected her LAL development. By concentrating on one case, the study captured the intricate interplay between FA tasks, LAL, and the real-world constraints encountered during student teachers’ initial teacher education experience.

4.1. Research Context

The study was conducted in a university that offers a four-year program designed to prepare EFL teachers for future employment in Chinese K-12 schools. The author was the English teaching methodology course instructor. The course was strategically positioned prior to a teaching practicum and was specifically designed for student teachers who possessed limited prior knowledge of pedagogical theories and little or no experience teaching in a classroom setting. In addition to introducing contemporary theories in second language education and historical developments in language pedagogy, the course afforded students the opportunities to engage in the practical application of FA-related concepts through a variety of instructional activities, including microteaching sessions, simulations, lesson planning and guided reflective journals.

In the present study, both the teaching methodology course and the teaching practicum were identified as the primary focal contexts for investigation. As summarized in Table 1, these two components were designed to equip the student teacher with the knowledge and skills necessary for FA implementation, including the conceptual understanding of FA and the ability to design and integrate FA tasks into instructional practice. The 16-week teaching methodology course comprised two interrelated parts. The theoretical part aimed to develop student teachers’ foundational understanding of FA, focusing on core concepts, task design principles, and the integration of FA into lesson planning. The practical component involved micro-teaching sessions through which student teachers designed and implemented FA tasks, followed by reflective discussions on their assessment practices. The subsequent five-week teaching practicum provided student teachers with opportunities to observe classroom instruction and conduct their own teaching in a field school setting, thereby aiming to apply their FA knowledge and skills in authentic educational contexts. Prior to data collection, the researcher sought ethics approval from the university’s ethics committee and obtained informed consent from Tracy.

Table 1.

Summary of the teaching methodology course and practicum.

4.2. Participant

Tracy (pseudonym) was chosen as the focus of the current study for the following reasons. First, she exhibited a sustained and explicit interest in exploring FA. This interest was evident in her willingness to experiment with FA tasks during her micro-teaching session. Notably, during her micro-teaching session, she actively integrated FA tasks into her lesson plans. Second, Tracy’s professional goals made her an appropriate choice for this study. She was committed to becoming an EFL teacher in K–12 settings, and had taken steps to prepare for this career path. Prior to the course, she participated in a school-level teaching competition and was awarded second prize, demonstrating her instructional competence and her motivation for professional growth. Third, Tracy’s personal learning experiences also played a role in shaping her orientation toward FA. As a former language learner, she expressed dissatisfaction with the predominant reliance on SA in her own educational background. This stance informed her determination to adopt FA tasks in her future teaching.

4.3. Data Collection

The data collection process lasted approximately 5 months, from September 2023 to January 2024. An overview of the data collection procedure is summarized in Table 2. Different instruments were employed to gather data for tracing Tracy’s changes in FA conceptions and design and use of FA tasks including semi-structured interviews, lesson plans, teaching observations, stimulated recall interviews, and reflective journals.

Table 2.

An overview of data collection.

Semi-structured interviews were the primary source of data for this study (see Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D). Four semi-structured interviews were conducted in Chinese: before and after the teaching methodology course, before and after the practicum. Based on Gu’s FA framework, the interviews were guided by a set of open-ended questions designed to explore Tracy’s FA conceptions and practices, including (a) her understanding of FA principles, such as “What principles of FA inform your approach to assessment?”; (b) planning and design of FA tasks, such as “When planning your lessons, what factors do you take into account?”; (c) underlying intentions and rationales for task design, such as “What intentions guide your decisions when designing FA tasks?”; (d) emotional responses during task implementation, such as “How did you feel while implementing FA tasks in your classroom?”; (e) reflection of her FA practice, such as “How do you evaluate FA task and practice?”. Each interview lasted approximately ninety minutes to ensure depth of expression and clarity of thought. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For the purposes of analysis and reporting, only excerpts relevant to FA design, implementation and interpretation of FA tasks, were translated into English and used as evidence to support the study’s findings.

Tracy’s lesson plans constituted another crucial data source, offering detailed documentation of her instructional intentions and FA design and implementation. These plans outlined key elements such as lesson objectives, the sequencing and integration of FA tasks, and the anticipated use of assessment evidence to inform her teaching. Analysis of the lesson plans enabled the researcher to examine how Tracy’s FA conceptions were operationalized during the planning phase, the extent to which FA tasks were purposefully embedded within the instructional flow and the strategies she employed to facilitate their effective implementation.

Two unstructured observations were conducted during the micro-teaching session and the practicum. The researcher’s focus was on student teacher’s FA decision-making, implementation and reactions to unexpected situations. No predetermined categories and classifications were used. Observation data supplemented other data sources to enable the researchers to gain a deeper understanding on the implicit understandings that guide the participant’ FA design and practice, which could not be obtained solely by interviews.

Two stimulated recall interviews were conducted in Chinese within 48 h of lesson teaching to facilitate the participant in more accurately recalling her thoughts and decision-making processes (Gass & Mackey, 2016). Tracy reviewed the recordings of her teaching, pausing at points she identified critical in lessons, to discuss her intentions and provide additional reflections. In addition, critical points that needed further confirmation or clarification were prompted by the interviewer. These focused on the rationale for Tracy’s on-the-spot decision-making, her judgment on the lesson plan and evaluations of her FA tasks design and practice.

Reflective journals were collected twice, following the course and the teaching practicum, serving as a supplementary data source (see Appendix E). Tracy completed two written reflective journals, guided by prompts related to FA task design, instructional decision-making and personal challenges. The corpus comprised two journal entries (4281 Chinese characters) for each data collection point. Tracy documented her evolving understanding and enactment of FA, modifications to task design, and insights from authentic classroom experiences. All data were returned to Tracy for verification as part of the member-checking process. Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D and Appendix E present selected interview questions and guiding prompts for the reflective journals.

4.4. Data Analysis

An inductive approach was employed for data analysis because it enables the large dataset to be reduced to analytically manageable units directly aligned with the research questions, while maintaining a systematic yet flexible procedure that accommodates both concept-driven and data-generated categories (Miles et al., 2019). The author engaged in a systematic process of reading and re-reading the interview transcripts, lesson plans and reflection to generate preliminary codes through constant comparison, re-examination, and re-evaluation. To develop a robust understanding of the collected data, the author extensively reviewed the data multiple times and invited a PhD student in applied linguistics to serve as a co-coder. Each coded independently roughly 20% of the data. The inter-coder reliability for coding FA conception and practice was assessed using Nviv11.0, achieving 90% and 87%, respectively. Discrepancies in coding were addressed through collaborative discussion among the coders to reach consensus. Some of the codes with excerpts are provided in Table 3. To ensure analytical depth and prevent the omission of significant dimensions, the coding process was further informed by existing literature on FA conceptions and practice. This iterative process helped identify critical elements such as the authenticity of FA tasks, the participant’s emotional responses to FA, and the development of LAL.

Table 3.

Sample codes and Instances.

To answer RQ1, three main themes were finally generated to best represent the essence of the meaning of the whole data set (more details in Table 3): (1) recognizing the pedagogical necessity of adopting authentic FA tasks in lesson plan; (2) aspiring to FA-oriented class that emphasizes higher-order thinking skills; (3) perceiving the empowering role of FA tasks in cultivating students’ self-regulated learning. The resultant codes were triangulated with lesson plans and reflective journals. To answer RQ2, the author relied on the interview transcripts. Initial coding of the data was guided by the interview questions which served as the coding categories. For instance, coding of the transcripts with the student teacher has the following categories: challenges in FA conceptions, mentors’ expectations and specific FA implementation stages.

4.5. Researcher Positionality

As a researcher, the author shares certain experiential commonalities with Tracy in relation to the research context; specifically, they are both EFL language learners and teachers. This shared background afforded an emic perspective, enabling a nuanced understanding of the participant’s lived experience and her engagement with FA tasks design and implementation. However, the researcher’s dual role as both investigator and lecturer in the participant’s teaching methodology course may have contributed to an imbalanced power relationship. To mitigate this risk, the researcher deliberated positioned herself as a learner, seeking experiential insights rather than adopting an evaluative stance. To address this imbalance, efforts were made to address this potential imbalance by providing pedagogical guidance aimed at supporting the participant’s professional growth and enhancing her understanding and practice of FA, rather than directing or prescribing specific actions. These strategies helped foster a more collaborative research relationship, enabling both the researcher and the participant to feel empowered throughout the research process.

5. Findings

5.1. Recognizing the Pedagogical Necessity of Incorporating Authentic FA Tasks into Lesson Planning

Through her engagement in this teaching methodology course, Tracy experienced a notable conceptual shift regarding the role and implementation of FA in classroom instruction. Prior to her participation in the course, she held relatively limited views of assessment, often perceiving it primarily as “a means of grading or testing student knowledge at the conclusion of instruction” (IT1). She seldom questioned the pedagogical rationale underpinning the selection and design of assessment tasks, nor did she link these tasks to clearly articulated learning objectives in their lesson plans (RJ). She argued that “I know that SA is not sufficient, but I have no clear understanding of how FA contributes to teaching” (IT1).

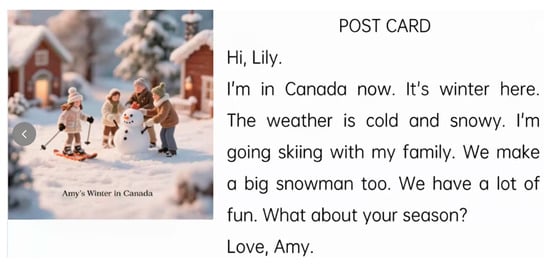

During her engagement with the course activities, particularly the FA-related lectures and guided reflections, she gradually developed a more sophisticated understanding of FA tasks as an integral component of instructional planning rather than a separate or add-on process. Specifically, she came to acknowledge that the effectiveness of FA lies in “its alignment with learning goals” (IT2) and its capacity to generate evidence that can “inform ongoing instructional decisions” (IT4). This deeper understanding became visible in her design of an imitation writing task (see Figure 1), which was positively evaluated by her peers and the course instructor as “more authentic and comprehensive” (RJ). This FA task required students accurately comprehend the content of a postcard sent by Amy. By engaging students in a realistic interpersonal communication scenario, the task effectively integrated formative assessment with instructional focus on genre-based writing. Tracy expressed that the formative value of this task lay in its capacity to “generate evidence of students’ understanding of writing conventions within an authentic learning context (SR).” She planned to draw on this evidence to determine students’ readiness for subsequent writing instruction and provide targeted feedback to guide improvement (IT2). This example illustrated her emerging recognition of the pedagogical necessity of incorporating FA tasks into lesson planning. She began to acknowledge the value of aligning assessment with instructional objectives and the potential of well-designed FA tasks to generate meaningful student learning.

Figure 1.

Formative Writing Task example from Tracy’s lesson plan.

Furthermore, Tracy’s imitation writing task demonstrated both situational authenticity and interactional authenticity, key criteria for designing meaningful FA (K. Koh et al., 2017). From the perspective of situational authenticity, the FA task required students to respond to a postcard from Amy by composing a reply that incorporated contextual information such as the current season, weather and local activities. This mirrors real-life situations in which individuals exchange postcards while traveling, making the FA task purpose-driven and contextually grounded. In terms of interactional authenticity (Bachman & Palmer, 1996), the task engaged learners in genuine language use, as they needed to interpret a written message and respond appropriately, thereby simulating real communicative exchanges. Through this design, students would not merely be required to produce language; rather they would be engaged in an interactional FA task that would call for attention to communicative intent, relevance, and audience. The incorporation of authenticity enhanced the pedagogical value of the FA task, supporting Tracy’s emerging understanding of how well-designed FA can promote meaningful learning.

Beyond the design of FA tasks, Tracy’s evolving conceptual understanding suggests a concomitant development in her LAL through engagement with FA tasks. She began to systematically integrate FA as a core component of instructional design, guided by the belief that such formative tasks could “inform and shape subsequent writing instruction” (RJ). It suggests that she gradually developed a more informed understanding of how assessment can be linked to pedagogical improvement. As she noted in an interview, “FA can steer language learning toward intended instructional goals, so it needs to be embedded into lesson planning from the outset” (IT2).

5.2. Aspiring to Design FA-Oriented Tasks That Promote High-Order Thinking Skills

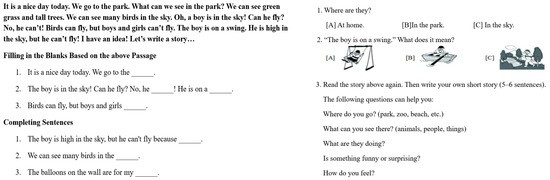

Changes in Tracy’s assessment design are also evident in a clear progression from traditional, form-focused tasks to more cognitively demanding activities aligned with FA principles that she had learned through the course. In Figure 2, her initial FA task comprises two conventional sections—gap-filling and sentence completion—designed to assess lower-order language skills such as vocabulary recall and syntactic accuracy. These two exercises reflect common assessment practice commonly adopted in Chinese English learning classrooms, where the primary objective is often to confirm learners’ ability to reproduce discrete linguistic items (Bachman & Palmer, 1996). While such assessment tasks may efficiently assess surface-level knowledge, they offer limited opportunities for students to engage in meaningful communication or exercise higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, reflection and metacognitive awareness of language use.

Figure 2.

A screenshot of FA tasks from Tracy’s reading lesson plan.

In contrast, by the end of the course, Figure 2 demonstrates a clear shift in Tracy’s assessment design, reflecting the integration of FA principles aimed at supporting and extending student learning. The revised task incorporates a story-based framework that combines reading comprehension, contextual interpretation, and inferential reasoning. Drawing on a text excerpt and accompanying higher-order multiple-choice questions, the FA task requires students to move beyond literal comprehension and engage in relatively deeper cognitive processing. For example, students are asked not only to comprehend surface-level textual content but also to interpret meaning (e.g., understanding the use of “the boy is on a swing”), infer situational context, and generate output (e.g., “write your own story”). This progression aligns with higher-order thinking skills outlined in Bloom’s taxonomy, including analyzing, evaluating, and creating (Chandio et al., 2016). Through this redesigned FA task, Tracy demonstrates a growing understanding of how FA can be used not merely to assess learning, but to actively foster deeper intellectual engagement and reflective thinking in language learning.

Tracy’s recognition of the potential of FA tasks to foster higher-order thinking was further evidenced in her interview responses and reflective journal entries. In one stimulated recall interview, she remarked, “I used to think assessment was just checking answers or seeing if students remembered the words. But now I realize that a good FA task can actually make them think more deeply, like connecting ideas or imagining situations (SR).” Similarly, in her journal, Tracy noted that “designing FA tasks that ask students to explain, infer, or create something helped me see what they were really thinking, not just what they memorized.” These reflections indicate an emerging understanding of the value of FA tasks in activating students’ cognitive engagement, moving beyond rote recall to tasks that challenge learners to analyze, evaluate, and construct meaning. Through this process, Tracy began to see FA not only as a pedagogical tool for monitoring progress, but also as a catalyst for deeper learning and intellectual development.

5.3. Acknowledging the Empowering Role of FA Tasks in Fostering Students’ Self-Regulated Learning

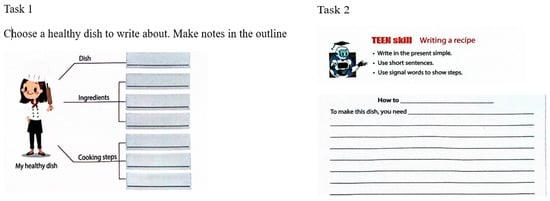

In addition to emphasizing authenticity and high-order thinking, Tracy deliberately incorporated students’ self-regulated learning (SRL) into her FA tasks design. It can be seen from the two FA tasks in her writing class, both of which reflect an intentional effort to engage learners in SRL processes through goal-directed activities (see Figure 3). In FA Task 1, students are required to outline a healthy dish by specifying the dish name, ingredients, and cooking steps. This task serves as a structured pre-writing activity that facilitates planning and goal setting—two key dimensions of SRL (Brandmo et al., 2020). By prompting students to generate notes prior to writing, the FA task fosters metacognitive engagement, encouraging learners to organize their ideas and anticipate the language and content demands of the upcoming task. FA Task 2 extends the formative cycle by moving students from planning to performance, aligning closely with the SRL phase of self-performing. The FA task 2 requires students to compose a recipe using present simple tense, short sentences, and signal words. These clear and explicit instruction and design features enable students to monitor their writing process and evaluate the extent to which their writing aligns with the expectations.

Figure 3.

A screenshot of FA tasks from Tracy’s writing lesson plan.

Tracy’s reflective journal and interview data elucidate her emphasis on fostering SRL in the design of FA tasks. She explained that requiring students to plan and organize their work heightened their focus, noting, “When I designed FA tasks, I paid close attention to getting students to plan and think about how to organize their ideas. Doing so helped them stay more focused on the task” (IT4). In the process of FA designing, Tracy appeared to place more emphasis on actively involving students in goal setting, planning and ongoing process monitoring of their learning processes. It seemed that Tracy demonstrated a more sophisticated understanding of FA that viewing assessment as a process-oriented practice rather than one focused solely on evaluating final language output.

Similarly, in her reflective journal, she expressed that “the FA task provided students with opportunities to plan prior to writing and offered clear goals during the writing process, thereby encouraging greater learner responsibility” (RJ). These accounts suggest that Tracy conceptualized FA tasks not solely from an assessment-oriented perspective but also as pedagogical tools to support SRL from the learners’ standpoint. This shift from viewing assessment primarily as a teacher-led evaluative activity to understanding it as a learner-centered process reflects a developmental advancement in her LAL, characterized by a more integrated alignment of teaching, learning, and assessment (Xiao & Yang, 2019; Brandmo et al., 2020).

5.4. Interpreting the Challenges to FA Tasks Designing and Implementation

5.4.1. Conceptions of Assessment

Although Tracy engaged in the design of different FA tasks, she occasionally expressed reservations about the pedagogical value of FA tasks, particularly in relation to grammar instruction. In her reflective journal, she noted, “I’m concerned that FA tasks might not effectively support grammar learning. None of the activities seem directly related to teaching grammatical concepts. When I was a student, I learned grammar mainly through doing lots of test items” (RJ). It reveals that Tracy’s underlying belief about effective assessment remains influenced by her prior learning experiences, in which explicit evaluation of grammatical knowledge played a central role, with grammatical accuracy continuing to hold a dominant position in her understanding of instructional effectiveness. However, Tracy also acknowledged that her participation in the teaching methodology course and practicum prompted her to reexamine these conceptions. As she reflected in a later interview, “I realized how strongly my engagement with FA tasks in this class have shaped my assessment beliefs this year” (IT4). This reflection signals an emerging openness to revisiting and reconstructing her pre-existed FA conceptions and practices.

Tracy’s initial skepticism toward FA tasks can be better understood within the context of her assessment background. Her experiences as a language learner were largely shaped by SA-driven approaches that emphasized “discrete-point testing and the mastery of grammatical structures” (IT1). Given this context, her hesitation toward FA is unsurprising. However, the course and practicum played a pivotal role in reshaping Tracy’s conceptual understanding of FA. These experiences encouraged her to critically reflect on her prior assumptions and engage with alternative perspectives on FA. Through exposure to theory-informed FA tasks design in teaching methodology course and teaching experience in the practicum, she gradually developed a more nuanced and reflective view of FA, contributing to the development of her LAL.

5.4.2. Cultural Norms

The present study has also found that Tracy’s implementation of FA tasks during her practicum was limited by prevailing cultural and institutional norms in Chinese K–12 education, where FA is often viewed as supplementary. Following her five-week practicum in a field school, Tracy reflected critically on how contextual and cultural expectations shaped her assessment choices. She acknowledged that the importance of conforming to prevailing school norms, particularly the expectation that student teacher must first demonstrate competence through structured and conventional teaching and assessment activities. As she noted: “I think the most important thing is to let students know I am competent, so sometimes FA tasks play a relatively small part in designing the class. I tend to adopt more traditional and structured activities” (IT4). In order to establish her professional legitimacy as a new teacher, Tracy felt the need to prioritize more controlled and teacher-centered activities over FA tasks.

Beyond the broader institutional expectations placed on her, the specific teaching context further constrained Tracy’s FA implementation. She was assigned to a mentor teacher who adhered strictly to SA, regularly administering monthly paper-and-pencil tests to diagnose areas for student improvement. The mentor was resistant to FA tasks, expecting Tracy to follow established routines. As Tracy explained, “The mentor did the same things in each class, and so it is very structured. I didn’t really feel I had much room to change because she was so organized and had everything set out, and they had a pattern, and all of her students were used to it (IT4).” In an effort to avoid confrontation, Tracy adopted SAs that were similar to those used by her mentor in most of her classes. In doing so, she avoided challenging her mentor’s competence and damaging her relationship with the mentor who would assess her performance. It can also be seen from her reflective journal “My mentor expected me to follow her routine closely. I did not want to challenge her way of teaching. Besides, I didn’t want to seem inexperienced. I felt that using traditional assessments made me appear more ‘in control’ and professional (RJ).”

Faced with these constraints, Tracy consciously aligned her assessment practices with those of her mentor to preserve relational harmony and avoid conflict. Adopting familiar assessment approaches allowed her to sidestep potential challenges to the mentor’s authority and ensured a smoother evaluation of her practicum performance. Tracy’s experience highlights how institutional expectations and relational dynamics could shape and even constrain the enactment of innovative FA practices, particularly in practicum contexts where innovation may be perceived as risk-laden or inappropriate.

5.4.3. Absence of Targeted Support

A third factor that significantly constrained Tracy’s implementation of FA tasks was the perceived absence of sustained instructional and institutional support for assessment task design. Although the teaching methodology coursework introduced her to the theoretical underpinnings and pedagogical value of FA, the opportunities for applying these principles in authentic teaching contexts remained limited. This finding aligns with observations from many teacher education programs, where assessment training is often decontextualized, and student teachers are typically provided with pre-designed or overly prescriptive assessment templates. Consequently, they frequently lack the confidence and pedagogical scaffolding required to engage meaningfully in the complex process of designing FA tasks that are responsive to their specific classroom contexts.

From Tracy’s perspective, the process of designing FA tasks that were both “authentic and cognitively engaging posed a substantial challenge” (IT3). In contrast to standardized SA, which follow fixed formats and are relatively straightforward to administer and score, FA tasks require careful alignment with specific learning objectives and a nuanced sensitivity to learner readiness and the dynamics of the classroom context. In one of her reflective journals, she wrote: “It’s hard to know if the FA task I designed really helps with learning or just looks creative. I often wasn’t sure how to connect the task to what I wanted students to take away from the lesson (RJ).” This reflection points to an emerging sensitivity to the complexity of FA task design, particularly the need to align task features with learning needs, while underscoring the tensions Tracy experienced when attempting to enact FA in practice.

Tracy’s uncertainty about the quality and pedagogical function of her FA tasks indicates a clear need for more targeted support and formative feedback from the teacher educator. As a student teacher, she had limited access to opportunities for collaborative task design with mentors and peers. She remarked, “We talked about FA in class, but we need more discussion on how to improve the tasks we design together with teacher and peers (IT4).” This observation underscores the iterative nature of FA task development, which typically requires multiple rounds of design, implementation, and refinement. It highlights the need for more interactive, practice-oriented support within teacher education program to help student teachers strengthen their LAL in relation to FA tasks through ongoing dialog, feedback, and collaborative reflection.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The findings of this single-case study suggest that Tracy’s engagement with FA tasks could contribute to the development of her LAL across the teaching methodology course and practicum. This development was manifested in three interrelated dimensions: (1) recognizing the pedagogical necessity of adopting FA tasks into lesson planning; (2) aspiring to design FA-oriented tasks that promote high-order thinking skills; and (3) acknowledging the empowering role of FA tasks in fostering students’ self-regulated learning. Tracy’s active engagement in the design, implementation, and reflection of FA enabled her to critically examine both the pedagogical value and practical use of FA in real classroom contexts, thereby contributing to her incremental development of LAL.

Overall, Tracy’s experiences indicated that assessment-related coursework and practicum engagement may play complementary roles in supporting her LAL development. Specifically, the course appeared to support Tracy’s conceptual understanding of FA principles and their pedagogical purposes, while the practicum provided situated opportunities to experiment with, reflect on, and refine FA task implementation. This finding is consistent with prior research, which has evidenced that active involvement of student teachers in assessment design processes substantially contributes to the development of their LAL (Pardo et al., 2024; X. Yin & Buck, 2019; L. Gan & Lam, 2024). When involved in such tasks, student teachers tend to engage in reflective decision-making and demonstrate increased awareness of the pedagogical and evaluative implications of their assessment choices (K. Koh et al., 2017; Shao, 2025).

Moreover, Tracy appeared to develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between language teaching and assessment through her engagement in FA task design, particularly by attending to authenticity, higher-order thinking, and students’ self-regulated learning. While these observations are drawn from a single case, they lend support to the view that practical, hands-on engagement with FA can serve as a meaningful resource for the development of student teachers’ LAL (Pastore et al., 2019; Park, 2024). This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that greater attention to the practical dimensions of assessment may be beneficial for student teachers’ learning (L. Gan & Lam, 2024; Fernández Ruiz et al., 2021; Xie & Cui, 2021; Atjonen et al., 2024). As for ITE, the study tentatively suggests the value of balancing theoretical instruction with opportunities for contextually grounded, practice-oriented assessment experiences, rather than focusing exclusively on abstract theoretical frameworks alone.

Despite recognizing the pedagogical benefits of FA, Tracy’s prior assessment conception, cultural norms in the field school and lack of targeted support appeared to constrain her willingness to fully implement tasks. Concerns about the effectiveness of FA tasks, together with the need to maintain harmonious relationships with her mentor and conform to established classroom routines led her, at times, to prioritize conventional assessment practices. These findings underscore that LAL development is not solely an individual cognitive process but is shaped by contextual, relational, and cultural factors within school settings (Pardo et al., 2024; Xu & He, 2019; Looney et al., 2018).

This case study illustrates that the combination of assessment-related courses and practicum experiences could help student teacher acquire a more comprehensive view of FA and support the development of LAL. These insights, in turn, can inform the design of ITE curricula and instructional practices. Specifically, teacher educators can incorporate opportunities for FA task design and reflection into coursework and practicum experiences, using sustained and guided reflection as a framework to support student teachers’ ongoing development of LAL in relation to FA practices.

The study was limited in scope and design. Its findings may not be generalizable because of its focus on a single student teacher. In addition, although deliberate strategies were employed to mitigate potential bias, the dual role of the author as both researcher and course instructor may still have influenced the participant’s response. Future research should extend this line of inquiry by including a larger and more diverse group of student teachers with different backgrounds and levels of assessment experience, thereby enabling a more comprehensive examination of LAL from multiple perspectives.

Funding

This research was funded by the Education and Scientific Research Project of Shanghai [C2026189].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai International Studies University (protocol code SISUGJ2024003 and date of approval 28 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the participant, Tracy, for her valuable assistance and support in this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Guiding Points for Semi-Structured Interview One.

- How were you assessed in your English learning prior to the course?

- What principles of FA informed your approach to assessment?

- What did you think of FA tasks in the class?

- What did you think of FA design?

- How would you design FA tasks?

Appendix B

Guiding Points for Semi-Structured Interview Two.

- When planning your lessons, what factors did you take into account?

- Did you implement FA task in your micro-teaching?

- What did you think of FA tasks in your class?

- How did you integrate FA in your teaching?

Appendix C

Guiding Points for Semi-Structured Interview Three.

- What intentions guided your decisions when designing FA tasks?

- How did you feel while implementing FA tasks in your classroom?

- After the course, how did you view the role and value of FA in language teaching?

- What difficulties did you encounter in designing FA tasks, and how did you respond to it?

Appendix D

Examples of Guiding Questions for Semi-structured Interview Four.

- How did you evaluate FA task and practice in the practicum?

- What activity in relation to FA did you think you did the best? Why did you think that went well?

- Which FA task did you think worked well? Why did you think it was successful?

- Which FA task did you think was less successful? Why factors did you think contributed to this?

- What did you think is the most challenging part in designing and implementing FA tasks in teaching practicum?

Appendix E

Key Questions for Reflective Journals.

After the course

- Write down key words that link to your understanding about assessment literacy in general and specific aspects in FA tasks design and implementation.

- What have you learned about FA strategies and principles in the course?

- Briefly describe the things that you think are most important in FA tasks design and implementation.

After the teaching practicum

- What did you feel about your FA in teaching practicum? Describe and explain your feelings.

- What do you think is the most challenging in FA task design and implementation? Why?

- Are there any differences between what you have learned from the course and from your real teaching experiences?

- After the practicum, what do you think of your LAL in relation to FA?

References

- Allen, J. M., & Wright, S. E. (2014). Integrating theory and practice in the pre-service teacher education practicum. Teachers and Teaching, 20(2), 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atjonen, P., Kontkanen, S., Ruotsalainen, P., & Pöntinen, S. (2024). Pre-service teachers as learners of formative assessment in teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(2), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L. F. (2024). What does language testing have to offer? In L. F. Bachman (Ed.), The writings of Lyle F. Bachman (pp. 367–399). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1996). Language testing in practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R. E. (2011). Formative assessment: A critical review. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandmo, C., Panadero, E., & Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2020). Bridging classroom assessment and self-regulated learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(4), 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational assessment knowledge and skills for teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. T. L., & Remesal, A. (2012). Prospective teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A cross-cultural comparison. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. D., & Bailey, K. M. (2008). Language testing courses: What are they in 2007? Language Testing, 25(3), 349–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabaroglu, N., & Roberts, J. (2000). Development in student teachers’ pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. System, 28(3), 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D. (2007). Conceptualizing pre-emptive formative assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(2), 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, M. T., Pandhiani, S. M., & Iqbal, S. (2016). Bloom’s taxonomy: Improving assessment and teaching-learning process. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 3(2), 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charteris, J., & Dargusch, J. (2018). The tensions of preparing pre-service teachers to be assessment capable and profession-ready. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 46(4), 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Brown, G. T. L. (2013). High-stakes examination preparation that controls teaching: Chinese prospective teachers’ conceptions of excellent teaching and assessment. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(5), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Cowie, B. (2016). Chinese preservice teachers’ beliefs about assessment. Educational Practice and Theory, 38(2), 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocki, A., Anam, S., Drajati, N. A., & Soden, B. (2025). Assessment literacy among Indonesian pre-service English language teachers: A mixed-methods study. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 13(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, A., DeLuca, C., & MacGregor, S. (2020). A person-centered analysis of teacher candidates’ approaches to assessment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 87(1), 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, C., & Braund, H. (2019). Preparing assessment literate teachers. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dimova, S., Yan, X., & Ginther, A. (2020). Local language testing: Design, implementation, and development. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ebneyamini, S., & Sadeghi Moghadam, M. R. (2018). Toward developing a framework for conducting case study research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Ruiz, J., Panadero, E., García-Pérez, D., & Pinedo, L. (2021). Assessment design decisions in practice: Profile identification in approaches to assessment design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(4), 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L., & Lam, R. (2022). A review on language assessment literacy: Trends, foci and contributions. Language Assessment Quarterly, 19(5), 503–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L., & Lam, R. (2024). Unveiling classroom assessment literacy: Does teachers’ self-directed development play out? Education Sciences, 14(9), 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z., & Leung, C. (2020). Illustrating formative assessment in task-based language teaching. ELT Journal, 74(1), 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A. (2016). Stimulated recall methodology in applied linguistics and L2 research. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, F. (2018). Language assessment literacy: Implications for language teachers. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(1), 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, F., & Murcia Quintero, D. (2019). Language assessment literacy and the professional development of pre-service language teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 21(2), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y., & Lam, R. (2023). Developing assessment literacy for classroom-based formative assessment. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 46(2), 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, M. (2007). Formative assessment: What do teachers need to know and do? Phi Delta Kappan, 89(2), 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. (2010). The place of language testing and assessment in the professional preparation of foreign language teachers in China. Language Testing, 27(4), 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K., Burke, L. E. C. A., Luke, A., Gong, W., & Tan, C. (2017). Developing the assessment literacy of teachers in Chinese language classrooms: A focus on assessment task design. Language Teaching Research, 22(3), 264–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K. H. (2011). Improving teachers’ assessment literacy through professional development. Teaching Education, 22(3), 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konadu, B. O. (2025). Pre-Service Teachers’ Understanding and perceptions toward assessment literacy: A systematic review. Psycho-Educational Research Reviews, 14(1), 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R. (2015). Language assessment training in Hong Kong: Implications for language assessment literacy. Language Testing, 32(2), 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Vered, A., & Alhija, F. N.-A. (2018). The power of a basic assessment course in changing preservice teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 59, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewkowicz, J. A. (2000). Authenticity in language testing: Some outstanding questions. Language Testing, 17(1), 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L., Li, G. Y., & Guo, X. (2021). Pre-service Chinese language teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A person-centered perspective. Language Teaching Research, 28(1), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., & Harris, K. (2018). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: Teacher assessment identity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(5), 442–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclellan, E. (2004). How convincing is alternative assessment for use in higher education? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(3), 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, R., García-Pérez, D., & Panadero, E. (2024). Shaping the assessors of tomorrow: How practicum experiences develop assessment literacy in secondary education pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. (2024). The exploration of EFL preservice teachers’ self-perceived importance of assessment literacy. Language Teaching Research Quarterly, 45, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, S. (2024). Institutionalising formative assessment through school reform: When educational policy and teacher education are misaligned. Cogent Education, 11(1), 2428075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, S., & Andrade, H. L. (2019). Teacher assessment literacy: A three-dimensional model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 84(1), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, S., Manuti, A., & Scardigno, A. F. (2019). Formative assessment and teaching practice: The point of view of Italian teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, E. M. (2020). Monitoring preservice teachers’ language assessment literacy development through journal writing. Malaysian Journal of ELT Research, 17(1), 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Scarino, A. (2013). Language assessment literacy as self-awareness: Understanding the role of interpretation in assessment and in teacher learning. Language Testing, 30(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S. (2025). Developing language assessment literacy: Formative assessment practice from pre-service teacher to novice teacher. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 34(4), 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiggins, R. (2017). The perfect assessment system. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L. (2013). Communicating the theory, practice and principles of language testing to test stakeholders: Some reflections. Language Testing, 30(3), 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagari, D., & Vogt, K. (2017). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers around Europe: Research, challenges and future prospects. Studies in Language Assessment, 6(1), 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., Bruna, C., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., & Yang, M. (2019). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: How formative assessment supports students’ self-regulation in English language learning. System, 81, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., & Cui, Y. (2021). Preservice teachers’ implementation of formative assessment in English writing class: Mentoring matters. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & He, L. (2019). How pre-service teachers’ conceptions of assessment change over practicum: Implications for teacher assessment literacy. Frontiers in Education, 4, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X., & Fan, J. (2020). “Am I qualified to be a language tester?”: Understanding the development of language assessment literacy across three stakeholder groups. Language Testing, 38(2), 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Li, Z., Panadero, E., Yang, M., Yang, L., & Lao, H. (2021). A systematic review on factors influencing teachers’ intentions and implementations regarding formative assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 28(3), 228–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, X., & Buck, G. A. (2019). Using a collaborative action research approach to negotiate an understanding of formative assessment in an era of accountability testing. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80(1), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.