Abstract

Science teaching in early years contexts has been identified as deficient due to poor educator confidence, lack of content knowledge, or minimal opportunities being made available for science experiences. To identify strategies to counteract these factors, this study explored how these deficiencies are enacted in learning contexts by examining the beliefs and practices of educators across three early learning sites. The focus of this study was threefold: to gather the perception of educators in relation to early childhood science; explore the learning environments; and observe the interactions facilitated by the educators to develop scientific knowledge and skills for young children. During the four stages of the research project, a disconnect was identified between the perception held by educators about science, science’s role in the early years, and the educators’ practice. We found that educators did not appear to reflect on the disconnect between their understanding of theory and implementation in practice—their praxis.

1. Introduction

Research into science in early childhood has been conducted since the 1940s, with scholars agreeing that young children can, and should, learn science (e.g., da Silva et al., 2020; Fleer & Robbins, 2003). While discrete subjects or content areas such as those defined as science or mathematics are not the focus of early years curriculum, such as the Early Years Learning Framework V2.0 (EYLF V2.0) (Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE], 2022) or the National Quality Standard (NQS) (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], 2018) in Australia, a focus on the pre-requisite knowledge for science around living things, energy, properties of materials, for example, are common to the experiences of young learners. As such, early childhood science refers to these early explorations of scientific constructs. It is believed that “as soon as children realize they can discover things for themselves, their first encounter with science has occurred” (Tu, 2006, p. 245), and they continue to develop their views on science concepts throughout their lives (Fleer & Robbins, 2003). Science is believed to be “fundamental for young children’s thinking about their world” (Fragkiadaki et al., 2023, p. 18).

Young children also learn from the world around them and are constantly making sense of the world they live in (Larimore, 2020; Reinoso et al., 2019). Children do this through home-based ‘small science’ (Sikder & Fleer, 2015), or everyday investigation within early education contexts. These explorations and children’s questions are the basics of science—content, procedure, and knowledge—that develop in the early years to ensure ongoing learning into the future (Reinoso et al., 2019). Even though children are naturally curious and experiment with everything in their surroundings from birth, the focus on science concepts in early years learning settings is often neglected or stifled through restrictive science practices (Brenneman et al., 2011). Previous research suggests that this is due to poor educator confidence (Oon et al., 2019) or lack of content knowledge (Barenthien et al., 2020; Nilsson & Elm, 2017).

For science learning to happen in formal contexts, Campbell et al. (2015, p. 21) stated that “it depends on the teacher’s awareness, to bring science to the surface, to make it visible for the children, because if they’re not made aware, then it will pass and it doesn’t go anywhere”. Thus, if children are exploring the garden and find insects or plant material that attracts their attention, it is up to the educator to maximise these observations for learning. If educators lack knowledge of scientific concepts and child-centred pedagogies of inquiry, they may fail to capitalise on this opportunity within the environment. Previous research on lack of knowledge and skills (e.g., Brenneman et al., 2011; Barenthien et al., 2020; Nilsson & Elm, 2017) suggests that there is a disconnect between understanding the theory of learning about science and the practice of doing science in the early years classroom. This also suggests praxis is required, where the educator can connect theory and practice in a meaningful way for young children’s learning (Foster & Fleenor, 2019). Therefore, the goal of this research was to examine educator knowledge of science, educator understanding of its place in relation to the science opportunities provided in the environment, and the interactions about science facilitated by the educators in their practice.

2. Literature Review

The project began with a review of the literature to inform the design of an approach to work with educators in the field. The reading of the literature identified that while debate existed over whether young children could and/or should learn science (da Silva et al., 2020), the majority agreed it was important. What was identified in this review, however, was that educators in early years settings appeared to lack confidence and/or knowledge for early science learning to happen (e.g., Oon et al., 2019). Previous research identified that educators are deficient in both content knowledge of science itself (Barenthien et al., 2020) and the pedagogical knowledge to teach science to young children (Abdo & Vidal Carulla, 2020). To address this deficiency, programmes such as Early Learning STEM Australia ([ELSA]; Splat-Maths, 2021) have been developed, and while these have shown some good results, there is little clarity about whether these improved educator practice in the long term.

2.1. Barriers to Early Childhood Science

Brenneman et al. (2011) developed an observation tool to rate science and mathematics in preschools. They found that learning environments conducive to science learning were important, yet most classroom interactions did not support children’s thinking or knowledge-building in science. This highlights the important role of the educator as a key determinant of success for early childhood science programmes and therefore identifies some of the barriers to its inclusion.

2.1.1. Lack of Confidence

Although the previous literature has reiterated the importance of science in the early years, several issues have been identified as barriers to science teaching in early childhood. Edwards and Loveridge (2011) found that educators in the early years lack confidence in teaching science to young children, while Oppermann et al. (2019) aligned this to a lack of self-efficacy in science teaching. Other studies suggest that early childhood teachers may not be predisposed to teach science (Reinoso et al., 2019) or lack confidence in planning and demonstrating some science topics, which reduces their focus in these areas (Oon et al., 2019). Teachers who feel inadequate in their science knowledge may lack efficacy (Oon et al., 2019) or feel unable to adapt content to the early years (Akerson, 2019). Oppermann et al. (2019) suggest that the predominantly female workforce may also be impacted by gender stereotypes in motivational factors to teach science content. Whatever the underlying cause of a lack of confidence in teaching science, it can lead to short, one-off, teacher-directed experiences (Gerde et al., 2018) rather than spontaneous child-led inquiries.

Ravanis and Boilevin (2022) showed that social interaction in science learning is fundamental and requires a strong understanding of children’s developmental progressions for connections between concepts to be made. If the educator is not confident, they cannot freely and openly engage in these spontaneous conversational interactions around science to further children’s learning (Ravanis & Boilevin, 2022). This means that any science learning becomes structured with specific organisation and focus, which keeps control firmly with the educator but also minimises the exploitation of the opportunities for teaching science in children’s daily experiences.

2.1.2. Knowledge

Previous research has also identified a lack of appropriate levels of science content knowledge among early childhood educators which impacts their ability to teach science concepts and skills (e.g., Barenthien et al., 2020; Nilsson & Elm, 2017). For many early years educators, science concepts may be difficult to understand (Abdo & Vidal Carulla, 2020), especially in relation to the underlying constructs related to the Nature of Science itself, which is an important starting point for teaching young children about science (Akerson, 2019). While science concepts in the early years often relate to the biological sciences as children explore their natural world (Larimore, 2020), subject areas such as chemical or physical sciences may be seen as more difficult to understand and teach (Abdo & Vidal Carulla, 2020) despite being significant in young children’s ‘sciencing’ of the material world (Areljung, 2019).

This lack of knowledge is also demonstrated through inappropriate pedagogical strategies used to teach early childhood science. Lee Shulman (1986) is recognised as being the first to identify that effective teaching required not only content knowledge (CK) but pedagogical knowledge (PK), and in fact, the two needed to go together in demonstrating pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). Researchers have since used this concept to examine educators’ abilities in these domains (Nilsson & Elm, 2017). Teachers have been found to lack these two distinct types of knowledge and the ability to combine them in practice, so while some studies have focused on improving knowledge, there may still be a lack of confidence in utilising the full range of PCK for science teaching in early years environments.

Researchers have suggested many ways of improving PCK as an essential element of teaching science to young children. Specifically, Afifah et al. (2019) suggest providing specific knowledge when constructing science projects for young children on concepts such as light; Marian and Jackson (2017) developed science-focused inquiries; and Akerson (2019) used children’s literature to investigate the Nature of Science. Other studies explored increasing PCK through the use of pedagogical prompts in the form of content representations or CoRes that explicitly linked content, teaching, and learning in relation to specific science topics (Nilsson & Elm, 2017), while Mitchell et al. (2017) suggested focusing on the big ideas of science to encourage effective investigations. In addition, Teo (2017) found that some practitioners embedded science in play-based scenarios that utilise sustained shared thinking (Abdo & Vidal Carulla, 2020) or through using creativity-based approaches (Cremin et al., 2015). All these suggestions of improving PCK, however, rely on the educator understanding the importance of their PCK, confidence in PCK, and their ability to set up the learning environment to provide science inquiries for the children.

2.1.3. Learning Environments

In the early years, the environment is seen to be the third teacher (Malaguzzi, 1996). This is highlighted in Australia’s National Quality Standard (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], 2018) in Quality Area 3, which encompasses the importance of the indoor and outdoor space as well as the resources available for play. In addition, the well-known Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale ([ECERS]; Harms et al., 2014) includes specific measures that can be used to examine resources within learning environments. The combination of the physical resources available and the interactions of the educators highlighted within this instrument emphasizes the role of the educator as they provide the resources, the time for exploration, and the interactions required to maximise the learning opportunities available. These key components are seen as determinants of success (Fragkiadaki et al., 2023). To further explore what this looked like in practice, this research aimed to examine educator perceptions of science learning for young children and the roles of these educators in intentional learning environments to support science learning. However, Tu (2006) identified that there are fewer science resources for children to access and utilise than those for other content areas, particularly literacy and numeracy. Further to this, when science resources were made available for children to choose within the learning environment, the educator and child interactions to support science learning with these resources may not be present (Brenneman, 2011). This reduced focus on science resourcing and interactions aligns with the reduced opportunities for science to take place in these environments and highlights a need to evaluate educator praxis as the basis of this study.

3. Current Study

Previous research identified that “education cannot continue to improve without the active participation of teachers in curriculum formation and in curriculum research and evaluation” (Kemmis, 2021, pp. 57–58). Based on this assertion, the researchers chose a participatory action research methodology to encourage educators to participate and collaborate through critically reflecting on their existing practice (Dania & Griffin, 2021; Wright, 2021).

The aim of this research study was to work with educators in three settings to identify what they know and believe about early childhood science learning, and what they did to promote science learning in their early learning environments. Drawing from a social constructivist approach, this project utilised cycles of action research to explore and model early childhood science within case study sites. The planned participatory action research engaged educators in three early learning centres as distinct case studies. The case study sites were chosen from a purposeful sample based on diversity of location, socio-economic status, and the size of the centre, in terms of the number of children and educators within the settings.

3.1. Methodology

Ethics was granted from the researchers’ home university, with consent from each centre manager and each staff member within the three early learning settings in an Australian metropolitan area before the researcher visited. The settings were selected from a convenience sample in relation to the ease of access to the researcher’s home and prior connection of the setting to the broader School of Education research team. Specific staff were selected based on the rooms within the settings where they worked. The participatory action research (PAR) project was implemented across a 10-month timeframe. This project structure was chosen as it emphasised collaboration between researchers and practitioners towards producing knowledge relevant to the stakeholders (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014). Initial questionnaires and observations were collected from educators prior to the researcher site visits. On each visit, the researcher modelled science-focused interactions with children aged three to five years. At the end of the implementation, the environment scales were completed again, and individual interviews with some educators replaced the questionnaire across the three sites. The purpose behind the use of multiple methods was to provide a broad focus to allow more diverse perspectives to be captured and to ensure there were multiple modes in which any gains in practice could be demonstrated. The pre- and post-test process with the scales gave an overview of the learning environment and educator viewpoints prior to the intervention and then after the intervention, thus allowing for any changes to be assessed, while the replacement of the P-TABS questionnaire with the interviews was designed to gain deeper perspectives from those most engaged with the project across the timeframe of implementation.

3.1.1. Instruments Used

The Preschool Teacher Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Science ([P-TABS]; Maier et al., 2013) was chosen due to its focus on educator interactions and how participants view science and because it has been shown to have excellent overall internal consistency (Maier et al., 2013). P-TABS consists of 35 statements relating to three categories: (1) teacher comfort, (2) child benefit, and (3) challenges regarding science. Participants are asked to rate their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with anchors at strongly agree to strongly disagree (Maier et al., 2013), with some items on a negative scale.

The Preschool Rating Instrument for Science and Mathematics (PRISM) (Brenneman et al., 2011), and Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS-3) (science and nature categories) instruments (Harms et al., 2014) were both chosen for their formal measures to evaluate resources in the environment but also to examine the opportunities taken by educators to interact within these early years environments. The PRISM instrument comprises a checklist of items for science and interactions with science materials. PRISM identifies if items are present in the environment during the observation period or if there is evidence of them being provided previously if not on the day. PRISM examines the materials available for biological and non-biological science explorations, resources to read about and represent science, and interactions that focus on the skills of science (i.e., classifying, observing, recording).

The ECERS-3 was also chosen as it has an interrater reliability of 92%, has strong test–retest reliability with moderate internal consistency (Hestenes et al., 2019), it examines a broader range of content areas within learning environments, and has criteria related to science and nature, including rating the availability of games and materials from science/nature categories, the frequency of use of these materials, and the encouragement of children to engage with these resources. The observer determines the level of engagement with the materials on a scale from Inadequate (Level 1) to Excellent (Level 7).

In addition to the questionnaires, the researcher’s observations were collated through the writing of field notes and the collection of photographic evidence.

3.1.2. Contexts

Site 1 was situated in an integrated service within a low socio-economic suburban area that aligned with a local In-Home Care scheme near a small shopping complex, which meant there were public transport options available to families to the site. This small early learning centre (ELC) educated 20 children per day in the 3–5 years room. The educator in the 3–5 years room held a Bachelor’s degree in Primary Teaching (BEd), so they were trained to teach primary-school-aged children (aged 6 to 12 years) and was supported by staff that held Diplomas and/or Certificate III qualifications. During the time of the research, this setting installed a new outdoor learning space designed by a nature-play company.

Site 2 was situated on an inner-city university campus in a medium-to-high socio-economic suburban area with close access to park areas that were accessible for regular walking experiences. This medium-sized ELC educated up to 40 children aged 3–5 years per day in adjoining rooms. The groups spent most of the programme together utilising both classrooms and the outdoor environment in a free-flowing indoor–outdoor style. The two educators in this setting had graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood (BEd) within the previous five years, so they were trained to teach children from birth to 8 years of age. They were supported by two Certificate III-trained assistants.

Site 3 was a large early learning centre, in a high socio-economic area, housed across two sites on the grounds of a K-12 independent school, managed by the church board connected with the school. This site was surrounded by new housing estates, which meant many young families were coming into the growing community and demand for the setting was increasing rapidly. The setting educated 20 children aged 3–5 years per day in a recently renovated building with another larger purpose-built complex on the other side of the carpark housing the remaining age groups of children. This site included purposely designed and created nature-inspired outdoor environments. At the beginning of the project, the educator in the 3–5 years room held a Bachelor’s degree in Primary Teaching (BEd) so they were trained to teach primary-school-aged children (aged 6 to 12 years) with a Certificate III-trained education assistant for support. In addition, there was a visiting artist who worked across all learning areas within the setting at different times across the week. The staff on this site changed across the project implementation, but there were always two educators with similar qualifications assigned to the room that was visited across the stages of the project.

The staff details outlined here are for the main staff within the 3–5 years room at each site who were involved in all stages of the research. For the P-TABS questionnaire implemented in Stage 2, however, some settings requested additional staff who sometimes worked in these rooms to also complete the questionnaire, which is why the number of responses is higher in this instrument’s results.

3.1.3. Method

The research project had four stages:

- (1)

- Preparation: researcher visits exemplary early learning setting to enable the development of professional learning (PL) sessions for staff consenting to the project;

- (2)

- Initial data collection: P-TABS pre-intervention questionnaire (Maier et al., 2013) for educators and completion of PRISM (Brenneman et al., 2011) and ECERS-3 (Harms et al., 2014) rating scales by a researcher at each site through observations;

- (3)

- Action: (a) implementation of PL session with all centre educators on each site (b) ongoing modelling of science experiences once per month (8 visits each) across an 8-month period; and

- (4)

- Follow-up data collection: post-intervention P-TABS questionnaire was replaced with 1:1 interviews and completion of PRISM (Brenneman et al., 2011) and ECERS-3 (Harms et al., 2014) rating scales at each site by a researcher.

3.1.4. Data Collection

Stage 1: A researcher travelled interstate to visit two exemplary early education sites to interview staff and collect observations of both the environments and their practices. These sites were visited because they had appeared as examples of quality practice in textbooks on early childhood science. Setting A was an early years programme on a large rural school site, while Setting B was a member of a larger Bush Kinder organisation (i.e., where educators take children to visit natural environments once per week, come rain, hail, or shine). The visits allowed the researcher to collect information on what worked for educators and thus provide examples for the PL in the case study sites.

Stage 2: Identified a baseline of educator views on science. This was achieved through the administration of P-TABS, PRISM, and ECERS-3.

Stage 3(a): The researcher provided a professional learning (PL) event for all education staff across all three case study sites. These events showcased science learning opportunities gained from observations and teacher interviews from the two interstate sites visited in Stage 1. The events were an important step in the participatory action research (PAR) framework of showcasing what was possible and demonstrating the knowledge of the researcher as holding expertise in the PAR process. The PL was for all staff to maximise science learning for young children in the learning environments, in interactions, and through walking experiences within outdoor learning environments.

Stage 3(b): The researcher visited each of the case study sites every month over an 8-month period. A conscious decision was made by the researcher not to bring additional resources to the case study sites. The researcher modelled science experiences from resources available to the children within the learning environments to demonstrate to participants that additional resources and specialist equipment were not necessary for effective early science learning. Modelling science experiences with the children engaged them in scientific exploration and thinking, while showing the educators how they might adapt their practices in line with the focus of the PAR project. These visits were designed to allow for collaboration and exploration of practice (Wright, 2021). During the final month of visits, the researcher was joined by an additional ‘expert’ in early childhood science, tasked with observing and documenting educator responses while the researcher completed the modelled science experiences. This colleague provided a written report on her observations of science (and STEM—science, technology, engineering, mathematics) that also informed the results of the research.

Stage 4: After the 8 months of visits to model science in the settings, the educators who had been present throughout the modelling within the project were invited to participate in a 30 min, semi-structured individual interview. A semi-structured interview was chosen as this format allows for unstructured responses to a specific set of questions (Cohen & Manion, 1996). Table 1 shows six key questions and several sub-questions asked of the 10 participants who agreed to be interviewed.

Table 1.

Interview questions.

As the modelling process is viewed as the most critical in impacting educator views and practices in improving the level of science learning within the early years classrooms, formal observations of the environment and completion of PRISM and ECERS-3 were repeated in stage 4. This was to identify if any change had occurred in the roles of the educators and the provision of science-based opportunities. This last stage allowed the participants to report on their experience of the PAR and reflect on what had been gained across the process of the research.

3.1.5. Data Analysis

The P-TABS questionnaire (Maier et al., 2013) was analysed for patterns or disparities across the groups of educators using an Excel spreadsheet. The PRISM (Brenneman et al., 2011) and ECERS-3 (Harms et al., 2014) results were compared using pre- to post-datasets. Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts followed the six steps as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). The interview data transcripts from each participant were examined through inductive coding processes, where initial codes were identified (Step 2) and then themes were refined and defined. A participant code (1–10) was assigned to each interviewee to reflect who the quote is from in which interview (I), e.g., I3. The interview findings were then compared to the P-TABS results to identify any overlaps in the ideas presented. The small sample size for each instrument meant that direct comparison could be collated into single documents or spreadsheets.

4. Results

Each case study was unique in the design, provision, and implementation of science experiences; however, there were similarities in how the educators approached science. To reflect these similarities, the findings are discussed by each stage of the project.

4.1. Stage 1

Interstate visits to sites provided insights into the role of the educator in science and the facilitation role needed, but also in the relaxed nature of the interactions where the children were able to explore, experiment, and take risks without the need for direct or close supervision. The science understanding shown by the children was high, with examples of questions, investigations, and data collection seen on multiple occasions. At both sites, the children had opportunities to be experts in areas they were confident in. For example, in Setting B, a 4-year-old was digging a trench in the outdoor area near other children playing with water. When asked what he was doing, he replied: “I am digging a dam for hydro-electivity”. He kept digging until the water began to be captured in his dam. Thus, the concrete examples provided by these centres enabled the researcher to pass on strong models of practice to the educators at the case study sites.

4.2. Stage 2

4.2.1. P-TABS Questionnaire

The P-TABS questionnaire was completed by 22 staff across the three case study sites (Site 1 = 14, Site 2 = 3, and Site 3 = 5). While some variation was present in the results across the 35 statements in P-TABS, 9 specific statements had the highest levels of consensus. Overall, the most variation occurred in statements that asked participants to rate their level of agreement related to confidence in teaching content areas. Levels of confidence contribute to decisions to try science experiences with young children, as staff often avoid content they lack confidence in. Specifically, higher confidence existed around biological content, and in the confidence to teach the scientific method or use scientific tools, which would indicate that these areas are more often the focus of early science experiences.

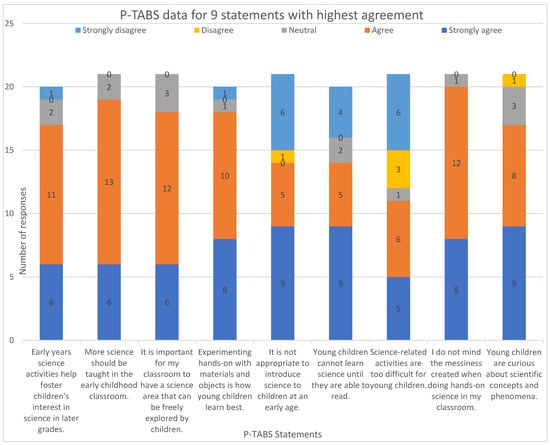

In addition, the P-TABS questionnaire identified a general lack of discussion among teaching teams around science questions (M = 3.00), and neutral responses were provided regarding the enjoyment of teaching science (M = 3.59). Figure 1, however, shows the nine P-TABS statements that had high levels of consensus across the 22 participants.

Figure 1.

P-TABS data on most consistently rated criteria. Note: For Questions (v), (vi), and (vii), questions were negatively worded, so agree and disagree responses have been swapped, i.e., Dark Blue is strongly disagree.

For example, P-TABS, statements reporting strong agreement:

- (i)

- Early years science was important for success in older grades; 18 agreed/strongly agreed (82%; M = 3.91).

- (ii)

- More science should be taught; 20 agree/strongly agree (91%; M = 4.18).

- (iii)

- Having areas available for exploration was important; 19 agree/strongly agree (86% M = 4.18).

- (iv)

- 18 participants agreed/strongly agreed (82% M = 3.91) that young children are curious about science.

For the negatively worded statements, where scores were reversed, results indicated the following:

- (v)

- Science being inappropriate; 19 disagree/strongly disagree (86% M = 4.18).

- (vi)

- Too difficult for young children; 18 disagree/strongly disagree (59% M = 1.59).

- (vii)

- Young children cannot do science before they can read; 19 participants disagree/strongly disagree (86% M = 4.18).

4.2.2. Rating Scales

Table 2 provides an overview of the PRISM rating scale results for each case study site during the initial data collection. Overall, the results demonstrate that while all settings provided materials for science, as well as reading and reporting on science, staff interactions were found to be lacking at Site 1, as they were not observed as having any interaction around science concepts.

Table 2.

PRISM data for the three case study sites from the initial visit.

In contrast to the PRISM data, the ECERS-3 data uses elements relating to science and nature. Table 3 identifies, on the continuum, which elements were observed at each case study site in the initial visit. Site 1 had minimal science/nature materials accessible; however, the encouragement by educators was also missing. In contrast, Sites 2 and 3 had appropriate science games as well as interactions by educators on display during the observation period.

Table 3.

ECERS-3 rating for the three case study sites on the initial observation visit.

4.3. Stage 3

Throughout the modelling period, the researcher visited each case study site monthly. On each visit, the researcher spontaneously interacted with the children using the materials available in the environment. Examples included the following: categorising leaves in the outdoor environment, building rockets with construction materials, examining space concepts in the block corner, and exploring dinosaurs in a small-world setup. During these visits, the children reported their science learning to the educators and the educators occasionally posed questions to the researcher. Reports of other science-based experiences that occurred between the researcher’s visits were collected in field notes. Only the educators at Site 2 keenly shared what had happened since the researcher’s previous visit and asked questions about what learning the researcher was completing with the children on this visit.

Expert Visits

From a visit to each site through the final month of the modelling visits, a visiting ‘expert’ colleague provided a report on the numerous science (and more broadly STEM) teaching opportunities available. At Site 1, the ‘expert’ report noted a curriculum and well-resourced environment with well-maintained areas for learning. However, they also noted that an overall disorganisation existed within the setting. Specifically, the ‘expert’ identified 11 teaching points or missed opportunities not explored by the educators in the room at the time of the visit. The report stated the following:

Science ideas appeared to happen by osmosis and without time to ‘report’ actions at mat-time. Critical reflection time is an essential pedagogy. This highly active early learning centre had ample opportunities to engage in Science activities and learning, however, overt support for these disciplines was not visible.

In terms of engaging with the ‘expert’ during the visit, the ‘expert’ reported that “At no time did an educator ask what I was doing. When I tried to catch the head educator for a chat, I found she thought she was doing much of what I was talking about”. These findings were consistent with the experiences of the researcher, who identified that staff within the rooms were not engaging with opportunities within the classroom or those being modelled within the setting.

At Site 2, the visiting ‘expert’ reported the environment as well maintained, uncluttered with “a sense of purpose and place for resources that encourage deep learning experiences (as opposed to superficial experiences)”. When engaging with the children with some props that the ‘expert’ had brought with them, they identified four teaching points that were not acted upon during the timeframe of the visit. In conversations with the educators, the expert found the following:

Both [educators] were interested in how scientific investigations could happen within the classroom using what was already there. Here are enthusiastic educators who are loving the idea of their nature excursions and had thought about using what was ‘here’ (i.e., the everyday resources that opened up opportunities for exploration, such as the air-conditioner, door hinges, elastic, twine). Listening to children’s questions and evoking interest in things surrounding them seemed natural enough and released the pressure to contrive science ‘things’.

The ‘expert’ described this response as refreshing and enjoyed the opportunity to extend the educators’ thinking beyond the biological focus. This feedback also aligned with the observations made across the researcher’s visits.

At Site 3, the visiting ‘expert’ found the following:

A rich perspective of science… learning was in action at this centre. Children were busily engaged in activities and generally had little time for visitors. This demonstrated how independent, collaborative and engaged the children were. They knew what they had to look for, or do, and got on at their own direction.

Discussions with the educators were limited as they were “very busy working with small groups and totally engaged with their task”:

There was certainly a lot happening at [this centre] that reflected science (and indeed math, engineering and technology). The children had choices and each choice appeared to have a direct connection to science learning. Resources on view offered scientific knowledge or skill building and were available for quiet contemplation, individual testing or collaborative work with an educator or peers.

These available opportunities, however, were not always taken up, as staff were always busy following the routine, including cleaning, toileting, and mealtime tasks. This feedback also aligned with the observations made across the researcher’s visits.

4.4. Stage 4

After months of modelling and a visit by the ‘expert’, post-intervention measures were completed, with the P-TABS replaced by individual interviews with the educators.

4.4.1. Comparison of Pre- and Post-Data

Table 4 and Table 5 present the post-intervention results of the PRISM and ECERS-R scales. A comparison between the PRISM data in Table 2 and Table 4 shows the following:

Table 4.

PRISM data for the three case study sites from the final visit.

Table 5.

ECERS-3 rating for the three case study sites on the final visit.

- Site 1 did not change, especially in the areas of staff interactions,

- Site 2 stayed the same (although it started high), and

- Site 3 improved.

4.4.2. Interviews

Data collection for Stage 4 included interviews with 10 educators (coded I1-I10) who had been present during the modelling across the three sites (Site 1 = 3, Site 2 = 1, and Site 3 = 6). Question 1 revealed that four participants (40%) identified science as experiments, e.g., “like science experiments and learning new things by seeing it” (I2), while three (30%) responded that science was messy play and sensory play. Two participants (20%) stated that science was “everything for me” (I8) and everywhere. While there were some references to hands-on, discover, and explore, the focus remained on specific experiences being required.

When exploring the concept of confidence to teach science with the educators, variation clearly existed, which could not be linked directly to the educators’ level of qualification. It was clear that a lack of confidence reduced the provision of science opportunities or the ability to follow science through. For instance, four participants (40%) referred to their own learning, such as “learning at the same time as the kids” (I4) or to science engagement being “more of a discovery process” (I5). While seven participants (70%) identified that children could learn a lot of science (and maths) through play, only two participants (20%) stated that they felt confident in following the children’s interests and learning alongside the children in the process.

Barriers to teaching science were noted by nine participants (90%), with key comments being coded into shared areas:

- Five (50%) mentioned time, e.g., “just time to set it up, I guess, time to be intentional about it” (I5); two (20%) mentioned resources, e.g., “Resources. Not having all of it, or what you want to make” (I4);

- Two (20%) mentioned the importance of educator knowledge, particularly in the areas of making the most of opportunities and knowing how to make science age appropriate across the diverse range in the contexts, e.g., “just knowing what to do, like, science isn’t a strong issue with me” (I7); and “sometimes it’s the age and translating different things to different age groups” (I9);

- Two (20%) mentioned making it interesting enough for the children or finding something that engaged everyone; and

- Two (20%) noted other staff not liking science or wanting to engage with it because of the mess and “you need to like messy play, so if you don’t like it then that’s it” (I8).

All educators felt that science could be integrated with other subject areas, including cooking, making playdough, in the sandpit, with water (mud pits), and through art. This was summed up well by I5, “It’s about a holistic approach”, and I6, who acknowledged that often the science that was happening was not identified until after the experience had ended “you don’t realise until you kind of sit back and naturally think about it”. Three (30%) identified opportunities as science was everywhere and could be part of everything, with I2 summing it up as “it usually does end up integrating somehow”.

When questioned about integration, seven participants (70%) aligned it with the opportunities available within the observed environments, e.g., “It kind of just fits into everything that you’re already doing in the space” (I1). Some contradictions existed, however, with four participants (40%) stating that more resources and specific spaces were required. For example, I6 contradicted themselves by saying that science was in any area but then later responding that “you need a specific time and a specific place for them” (I6). Sand play and outdoors were identified the most for science opportunities (six participants—60%), e.g., “The outdoor areas there’s a lot of different areas you can actually promote the learning of science in all of their playing” (I7). This aligned with the sensory and messy focus of multiple educators as well as their preference for biological sciences.

When asked what additional support was required for teaching science, only educator I7 specifically mentioned formal professional learning, saying, “probably PDs you’d need to do so that you can find out”. Five educators (50%) noted that they wanted more ideas for science and to participate in additional sharing of what other educators do across settings. Two (20%) felt that they needed specialist items, e.g., “Maybe stuff like a microscope, you know, where they can see things under it” (I10), while another two (20%) suggested that resource books with specific experiences and diagrams would be beneficial e.g., “having some kind of a booklet or something like that, or a book that specifically says you can do this with that age group” (I6). Overall, the interview responses alluded to more use of science in the early years environments than was observed in practice.

5. Discussion

This project aimed to explore what factors impact introducing science learning in ELCs and identify if ongoing on-site professional learning could counteract these identified concerns. Findings reinforced the importance of the educator in the science learning process but also highlighted the difficulties associated with changing perceptions and practices of the educators. The educators engaging with the research all reported the importance of science and the need for young children to engage in scientific learning; however, this study found that their practice did not always support these views. In practice, many of the educators still expected to see structured and formal science learning experiences and had not identified the multiple opportunities available for science learning identified during the visits by the researcher and the ‘expert’. This disparity between the perception of science reported by the educators and the practices within the settings led to the identification of praxis as being the missing link in the process.

The notion of children being able to do science is supported by the literature (da Silva et al., 2020; Fleer & Robbins, 2003; Tu, 2006), and the importance of the environment is also emphasised in studies into early childhood science programmes (Brenneman et al., 2011). It was clear from the results of this study, however, that awareness of these constructs was not enough to recognise good practice in the case study sites. While science materials were available in the environments in the case study sites, in most cases, the children were mostly expected to interact with these resources alone and develop their own knowledge through their play. Thus, in two of the case study sites, this did not reflect the social processes important for praxis (Brendel et al., 2019) or the use of social interaction needed for the development of cognitive operations (Ravanis & Boilevin, 2022). In both Sites 1 and 2, staff were more focused on routines and monitoring, thus no praxis occurred. Specifically, Site 1 educators continued to focus on supervision, monitoring, and completing routine tasks rather than engaging with the learners in the spaces, and Site 3 educators were often more concerned with monitoring and meeting administrative requirements than following up on the science modelling due to inconsistent staffing and adjusting to new room routines.

The findings for Sites 1 and 3 are consistent with previous research (e.g., Tu, 2006), where minimal interactions within the environment were targeted towards science-focused interactions. Contrary to this, however, Site 2 had educators who asked the researcher about the experiences completed on the modelling visits. These educators appeared to connect with the information presented in the professional learning and the theoretical ideas behind place-based pedagogies and embraced the idea of the nature walks to engage their children in the practice of exploring their local environment—praxis in action.

5.1. Praxis: Theory to Practice Disconnect

This study highlights that there is still a lack of connection between science learning theory, perception of its importance, and the practice of educators engaging children with science learning through intentional science-focused opportunities. One of the key ingredients for educators putting theory into action as a process of supporting praxis is the ability to engage in dialogue to self-assess (Brendel et al., 2019). This lack of praxis or reflective dialogue in connecting perception to practice was demonstrated by I5, who responded that in early childhood, “there is science everywhere” and it has “an element of facilitation [when children] pose their own questions”, yet there were several times where I5’s actions were in opposition to these beliefs. For example, I5 asked children, who had taken buckets from the sandpit and spent an entire morning collecting natural materials and engaging in discussions about the natural materials amongst themselves, to “tip them back to the garden and put the bucket away” with no thought to extend this science learning.

This study also showed a clear disconnect between participants’ spoken understanding and their practice. Participants did not recognise that the modelled science activities in the intervention visits were designed specifically to give them ideas for incidental science learning by utilising only materials already on hand at each site. This was demonstrated by participants at the end of the intervention who stated that science was “teacher led experiments like the volcano activity” (I2) or “looking through microscopes or blue lights at germs on children’s hands at mat time” (I10). Previous research has shown that this lack of content knowledge often leads to one-off experiments (Gerde et al., 2018) rather than having confidence to explore what is already available (Oon et al., 2019). The lack of understanding meant praxis was not supported (Brendel et al., 2019).

5.2. Research Limitations

Due to the limited number of case studies, broad generalisations cannot be made. What this research does identify, however, is that the modelling of the science experiences needs to be more explicit, as the educators did not focus on the science that was being demonstrated by the researcher during the visits. Although the research was based on PAR models, the majority of educators did not embrace their role in this and therefore did not change their practice during/after the intervention.

The second limitation was the use of researcher-assessed environmental scales that had scope for misrepresentation of the results. When noting the improvement in the ratings of the sites against the PRISM and ECERS-3 criteria, consideration must be given to whether the improvement was due to the researcher knowing that these checklist items were available more often through visiting sites more regularly, rather than being based on a one-off evaluation visit.

Finally, an additional concern with the small sample means that the research team could not identify if qualifications influenced engagement in the process. It was noted that the tertiary early childhood-qualified educators at Site 2 engaged more with the researcher and appeared to adapt their practice, while those with tertiary primary school qualifications in the other sites did not. This disparity warrants further investigation.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to identify barriers to using informal/incidental science-related activities during children’s play experiences in early education settings. This study reinforced the importance of the role of the educator as a facilitator of science learning, not only through the provision of science materials but through interactions and following children’s interests in the learning process. Most educators engaged in the project appeared unable to connect what they understood early childhood science to be, in terms of exploration and hands-on activities, to the implementation of inquiries, and using children’s interests or asking open-ended questions as a way for science to happen. Although some educators appeared to understand that science was everywhere and that young children can do science, this understanding did not translate to practice. In addition, despite demonstrations of science in everyday activities with minimal specialist equipment, many educators still believed scientific equipment and/or specific spaces were required for children to do science. This highlights that an understanding of the processes of learning science, and knowledge of science in daily life, is important for educators to change their practice. Further, self-reflection is required to make changes to practice and for praxis to happen. Thus, the link from theoretical science ideas to science practice presented a barrier.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R.; methodology, P.R.; formal analysis, P.R. and P.R.C.; investigation, P.R.; resources, P.R.; data curation, P.R. and P.R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R.; writing—review and editing, P.R. and P.R.C.; project administration, P.R.; funding acquisition, P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Edith Cowan University through an Early Career Researcher grant (G1002218). Although the first author has since moved to SCU, the research was conducted while at ECU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Edith Cowan University (Project code 14046: ROBERTS and date of approval 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study is not available due to the conditions of the Ethics approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge the work of the educators involved in the project and Elaine Blake for taking on the role of the expert visitor within the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdo, K., & Vidal Carulla, C. (2020). Learning about science in preschool: Play-based activities to support children’s understanding of chemistry concepts. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(1), 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifah, R. N., Syaodih, E., Setiasih, O., Suhandi, A., Maftuh, B., Hermita, N., Samsudin, A., & Handayani, H. (2019). An early childhood teachers teaching ability in project based science learning: A case on visible light. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1157(2), 022049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerson, V. L. (2019). Teaching and learning science in early childhood care and education. In The Wiley handbook of early childhood care and education (p. 355). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Areljung, S. (2019). How does matter matter in preschool science? In Material practice and materiality: Too long ignored in science education (pp. 101–114). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2018). National quality standard. Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/national-quality-standard (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Australian Government Department of Education (AGDE). (2022). Belonging, being and becoming, the early years learning framework for Australia V2.0 (EYLF V2.0). Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Barenthien, J., Lindner, M. A., Ziegler, T., & Steffensky, M. (2020). Exploring preschool teachers’ science-specific knowledge. Early Years, 40(3), 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, M., Siry, C., Haus, J. M., & Breedijk-Goedert, F. (2019). Transforming praxis in science through dialogue towards inclusive approaches. Research in Science Education, 49, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenneman, K. (2011). Assessment for preschool science learning and learning environments. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 13(1), n1. [Google Scholar]

- Brenneman, K., Stevenson-Garcia, J., Jung, K., & Frede, E. (2011). The preschool rating instrument for science and mathematics (PRISM). Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C., Jobling, W., & Howitt, C. (2015). Science in early childhood. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (Eds.). (2014). Participatory action research. In The SAGE encyclopedia of action research (Vol. 2, pp. 583–588). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1996). Research methods in education (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cremin, T., Glauert, E., Craft, A., Compton, A., & Stylianidou, F. (2015). Creative little scientists: Exploring pedagogical synergies between inquiry-based and creative approaches in early years science. Education 3-13, 43(4), 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dania, A., & Griffin, L. (2021). Using social network theory to explore a participatory action research collaboration through social media. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(1), 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J. C. S., Lucas, L. B., & Sanzovo, D. T. (2020). Science teaching in early childhood education: A systematic review of teaching journals, theses and dissertations. Research, Society and Development, 9(5), 81953142. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, K., & Loveridge, J. (2011). The inside story: Looking into early childhood teachers’ support of children’s scientific learning. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 36(2), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleer, M., & Robbins, J. (2003). “Hit and run research” with “hit and miss” results in early childhood science education. Research in Science Education, 33(4), 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S. L. G., & Fleenor, S. J. (2019). The power of praxis: Critical thinking and reflection in teacher development. In S. P. A. Robinson, & V. Knight (Eds.), Research on critical thinking and teacher education pedagogy (pp. 91–106). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkiadaki, G., Fleer, M., & Rai, P. (2023). Science concept formation during infancy, toddlerhood, and early childhood: Developing a scientific motive over time. Research in Science Education, 53(2), 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerde, H. K., Pierce, S. J., Lee, K., & Van Egeren, L. A. (2018). Early childhood educators’ self-efficacy in science, math, and literacy instruction and science practice in the classroom. Early Education and Development, 29(1), 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2014). Early childhood environment rating scale (ECERS-3) (3rd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hestenes, L. L., Rucker, L., Wang, Y. C., Mims, S. U., Hestenes, S. E., & Cassidy, D. J. (2019). A comparison of the ECERS-R and ECERS-3: Different aspects of quality? Early Education and Development, 30(4), 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S. (2021). Action research for change and development. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Larimore, R. A. (2020). Preschool science education: A vision for the future. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(6), 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M. F., Greenfield, D. B., & Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J. (2013). Development and validation of a preschool teachers’ attitudes and beliefs toward science teaching questionnaire. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguzzi, L. (1996). The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Ablex Publishing Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, H., & Jackson, C. (2017). Inquiry-based learning: A framework for assessing science in the early years. Early Child Development and Care, 187(2), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, I., Keast, S., Panizzon, D., & Mitchell, J. (2017). Using ‘big ideas’ to enhance teaching and student learning. Teachers and Teaching, 23(5), 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P., & Elm, A. (2017). Capturing and developing early childhood teachers’ science pedagogical content knowledge through CoRes. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 28(5), 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oon, P.-T., Hu, B. Y., & Wei, B. (2019). Early childhood educators’ attitudes toward science teaching in Chinese schools. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(4), 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, E., Brunner, M., & Anders, Y. (2019). The interplay between preschool teachers’ science self-efficacy beliefs, their teaching practices, and girls’ and boys’ early science motivation. Learning and Individual Differences, 70, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanis, K., & Boilevin, J.-M. (2022). What use is a precursor model in early science teaching and learning? Didactic perspectives. In Precursor models for teaching and learning science during early childhood. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Reinoso, R., Delgado-Iglesias, J., & Fernández, I. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ views on science teaching in early childhood education in Spain. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(6), 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikder, S., & Fleer, M. (2015). Small Science: Infants and toddlers experiencing science in everyday family life. Research in Science Education, 45(3), 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splat-Maths. (2021). Early learning STEM Australia (ELSA) program. Available online: https://elsaprogram.com.au/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Teo, T. W. (2017). Editorial on focus issue: Play in early childhood science education. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, T. (2006). Preschool science environment: What is available in a preschool classroom? Early Childhood Education Journal, 33(4), 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. (2021). Transforming mathematics classroom practice through participatory action research. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 24, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.