Abstract

The Polish diaspora’s commitment to maintaining its cultural and linguistic heritage in foreign environments not only enriches their communities but also deepens the understanding of diaspora dynamics in cultural preservation. This article analyzes the narrative development of Polish-speaking children as a means of supporting the maintenance of the Polish heritage language (HL) in Finland. The case study focuses on a family with a visually impaired father and three children. The material was drawn from interviews with the parents, books created by the children on their own initiative, and picture book narratives. Using an ecological approach and narrative analysis, the study explores how children naturally expand their competence in Polish through storytelling. By fostering storytelling skills, children strengthen their linguistic, cultural, and emotional connection to their HL. Narratives enable them to use Polish in meaningful, everyday contexts, creating a natural environment for language practice. Through stories that incorporate elements from Polish, Finnish, and international settings, children develop intercultural awareness, adaptability, and a deeper appreciation for their Polish roots. Storytelling between parents and children in Polish also fosters emotional closeness and reinforces the family’s linguistic bond. It encourages children to communicate with Polish-speaking relatives, such as grandparents, thereby supporting intergenerational language transmission.

1. Introduction

Assessing children’s oral narratives is of great interest to both researchers and practitioners, as narrative proficiency is a vital skill throughout life. Oral narrative abilities are emphasized in most school curricula, and numerous studies highlight their importance for both academic and social success, particularly for children with typical development as well as those with language and learning disabilities. Scionti et al. (2023) remark that the development of narrative abilities is a dynamic and interactive process that plays an important role in children’s linguistic, cognitive, and social development. The use of narratives marks a crucial milestone in the study of language development, with storytelling providing a real and contextualized way for children to express themselves. As a result, many researchers consider it a naturalistic method for exploring language acquisition (e.g., Dobinson & Dockrell, 2021; Gagarina et al., 2012; Gagarina & Bohnacker, 2022).

Research consistently shows that strong narrative skills are positively linked to structural language, literacy, and social abilities (Andreou & Lemoni, 2020; Pauls & Archibald, 2021; Zanchi et al., 2019). An investigation into the associations between three types of parental linguistic support—reading, storytelling, and singing—and children’s language skills found that these activities, particularly reading and storytelling, are positively linked to higher levels of expressive lexical, phonological, grammatical, and general language abilities in young children (Mustonen et al., 2024).

The development of narrative abilities in children is a crucial aspect of their overall language development and cognitive growth (Cleave et al., 2010). Narrative abilities refer to the capacity to understand, create, and retell stories, which includes organizing events in a coherent sequence, using appropriate language structures, and engaging in creative expression (Boudreau, 2008; Moran et al., 2021). In early childhood, narrative abilities begin with simple descriptions of events or experiences, often in the form of “scripts” related to daily routines. Children start by recalling and describing familiar events, like what they did during the day, forming the foundation for more complex narratives. As children grow, they begin to understand the basic structure of stories, including the introduction, development, and conclusion. They learn to connect events logically and chronologically, using language to express cause and effect, sequence, and time (Kao, 2015, pp. 33–51; Stadler & Ward, 2005).

According to Del Negro (2014), narrative development begins as early as age 2. At 2–3 years, children may string together unrelated ideas around a central theme. By 3–4 years, they produce primitive narratives centred on a character, topic, or setting, often incorporating facial expressions or body postures, with a problem and resolution. By 6–7 years, children produce true narratives with logical progression, and by 8–10, they manage structural components effectively and adapt their storytelling to listeners. After age 10, narratives become more complex, detailed, and engaging, with varied linking devices and audience awareness (Del Negro, 2014). In bilingual institutions, educators rarely have time to support these skills (e.g., Chen, 2015).

Studies show that good narrative skills in preschool and early elementary school are predictive of literacy and reading comprehension later in academic life. Children with language impairments tend to have difficulties with producing and comprehending narratives (O’Connor & Hayes, 2019). Bilingual children’s narrative development can be enhanced or impeded by cultural traditions (e.g., Gagarina & Bohnacker, 2022; Protassova, 2021). Conversations with grandparents in the family language play an important role (e.g., Istanbullu, 2024).

In discussing children’s language use, this study also differentiates between errors (systematic deviations from target forms measurable against normative standards), non-standard forms (variants reflecting pluricentric norms or contact influence), and developmental approximations (emergent features typical of bilingual acquisition). Clarifying these categories is essential for accurate interpretation of data on children’s narrative development.

Narratives can be assessed at the macrostructure level (overall story structure) and microstructure level (specific language features) (Scionti et al., 2023). During development, there is a remarkable increase in macrostructural narrative skills, particularly in the transition from preschool to school-age. If a child seems to have difficulty with developmentally appropriate narrative tasks, caregivers should contact the child’s primary educators and/or a certified speech–language pathologist for assessment (Lindgren et al., 2023; Yaari et al., 2024).

Interaction with adults and peers is vital for narrative development (Bitetti & Hammer, 2016, 2021; Vilà-Giménez et al., 2021). Through conversations, reading, and storytelling activities, children receive feedback, model more complex narrative forms, and practice their skills. This interaction helps them refine their ability to construct and share stories. As children’s cognitive abilities mature, they engage more deeply in creative and imaginative storytelling. They invent fictional characters, create fantasy worlds, and experiment with various genres and narrative styles, which fosters creativity and cognitive flexibility.

Developing narrative abilities requires an expanding vocabulary and mastery of grammatical structures (Berman & Slobin, 1994; Tilstra & McMaster, 2007; Verhoeven & Stromqvist, 2004). Children learn to use descriptive language, dialogue, and varied sentence forms to make their stories more engaging and understandable. Advanced narrative skills involve understanding and conveying different perspectives within a story. Children begin to develop characters, describe their emotions and motivations, and present conflicts and resolutions, which helps them in social understanding and empathy. The mother’s decision to correct narratives is influenced by their cultural background and the social environment. Storytelling practices within families and communities, exposure to books and media, and the encouragement of creativity all play a role in shaping narrative abilities.

Purpose of the study is to analyze the development of narrative abilities, which is crucial for Polish-speaking children in Finland as it supports their heritage language (HL) acquisition and cognitive growth. For bilingual children, including those in Finnish educational settings, cultural traditions and interactions with family members play a significant role in enhancing narrative skills. Assessing narratives helps identify areas where children may need support. Interaction with adults and peers through storytelling activities offers feedback and models complex narrative forms, aiding skill refinement.

This study addresses the following research questions:

- -

- How do parents support their children’s narrative skills through oral and written storytelling?

- -

- How might insights into children’s narrative abilities contribute to assessing their overall language development?

- -

- What influences children’s maintenance of their HL?

By addressing these questions, I aim to contribute to the understanding of narrative development in bilingual contexts and its implications for language acquisition and cognitive growth.

2. Background of the Study: The Polish Diaspora and Heritage Language Maintenance

Research on HLs has long emphasized the challenges of intergenerational transmission and the crucial role of educational, familial, and community contexts in maintaining minority languages (e.g., Fishman, 1991; Valdes, 2017). For Polish communities abroad, these dynamics are particularly salient, as the global Polish diaspora—estimated at 18–20 million people—grapples with language maintenance in contexts where Polish is often invisible in the public sphere and opportunities for formal instruction are limited (Polonia Statistics, 2024; Romanowski & Seretny, 2024; Wojdon & Skotnicka-Palka, 2021). While extensive work has explored Polish migration to larger European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany, less attention has been paid to smaller diaspora communities, such as those in Finland, where different demographic, educational, and sociocultural conditions shape HL practices. Being a Pole abroad is not a new phenomenon, with Polish children’s language acquisition in the multilingual environment of the Tsarist Russia documented by J. N. I. Beaudouin-de Courtenay as early as in late 19th–early 20th centuries (e.g., Smoczyńska, 2000).

HL research has established several key insights relevant to this study. First, family language policies are central in shaping children’s linguistic repertoires: parents’ decisions—whether conscious or unconscious—strongly influence children’s HL competence (King et al., 2008; Curdt-Christiansen & Palviainen, 2023). Second, educational structures, particularly home language (or mother-tongue) instruction, have been shown to support bilingual development and reinforce identity (Cummins & Swain, 2014; Schwartz & Verschik, 2013). Third, religious institutions and community networks provide important cultural anchors, especially in diasporic settings where institutional support is limited (Banasiak & Olpińska-Szkiełko, 2021; Djundeva & Ellwardt, 2020; Vickrey et al., 2019).

This study uses the terms mother tongue, home language, and HL interchangeably. The term mother tongue is used in Finnish educational policy to denote the language a child first learns or uses at home, which may or may not coincide with the HL. Home language (HL in the Finnish policy sense) refers to the language spoken within the family and supported by supplementary classes. HL, following international scholarship (e.g., Montrul, 2016; Polinsky, 2018), designates a minority language learned in the home environment and maintained to varying degrees across generations. The distinction is important for analyzing policy documents and family practices, as these terms carry different institutional and scholarly meanings.

Within Polish diaspora (Polonia, 2017) studies specifically, prior research has documented the role of cultural organizations, schooling, and Catholic parishes in supporting HL transmission (Dębski, 2016; Gerhardt, 2005; Lesińska, 2018; Zielińska et al., 2014). However, much of this scholarship has focused on large-scale diasporas, leaving smaller communities underexplored. The Polish community in Finland is relatively small: in 2024, 6428 Polish nationals were registered as residents (Statistics Finland, 2024). This number underestimates the total population, as children of mixed Polish–Finnish parentage may be registered as Finnish nationals. Migration flows have remained modest—around 300–500 individuals per year, with a slightly higher number of men than women. Compared with the United Kingdom or Germany, Finland has not become a major destination for Polish migrants after EU accession in 2004, but it offers a distinctive environment where HL support is institutionalized.

Scholarship on Finnish HL education highlights the relatively progressive system in which municipalities provide mother-tongue instruction to multilingual pupils as a supplement to basic education (Helsinki, 2025). Yet, few studies have examined how Polish-speaking families in Finland engage with these provisions, how they conceptualize the Polish language in relation to Finnish, and how narrative practices within families mediate HL maintenance. A study showed that the majority of parents are satisfied with how their children speak Polish (Jakubek-Głąb, 2024). However, not all approach this process consciously or know what to do to develop the language.,maintaining the Polish language helps preserve their identity, creating a sense of pride and connection to their roots. However, this can conflict with the need to assimilate into the Finnish language and culture. Finding a balance between these identities is a central issue in language maintenance, as linguistic competence often dictates the strength of cultural ties. The majority pass on the language spontaneously, simply because they communicate in it. The conscious decision to pass on the language to the next generation on a high level is not widespread. The role of the church is significant, although the fact that Catholic services are conducted in several languages shows that families have to choose in which language to attend the mass (Jakubek-Głąb, 2024).

Building on prior research on Polish diaspora communities and HL maintenance, this study contributes to the field in three ways: It shifts attention to a small, underexplored Polish community in Finland, thereby broadening our comparative understanding of HL maintenance across different migration contexts; It examines how Polish-speaking families overcome the tension between spontaneous HL transmission at home and formal support through Finnish educational policy; It accentuates the role of narrative practices in children’s HL development, demonstrating how storytelling within families and exposure to Polish media foster both linguistic competence and cultural identity. Situating the study within HL research, and focusing on the specific Finnish context, this article advances our understanding of how HL maintenance operates in smaller diasporas and what this reveals about broader processes of bilingual development and identity formation.

3. Materials and Methods

We selected one family for analysis because they were open to collaboration and because the children demonstrated a clear interest in maintaining the Polish language. Focusing on a single family—including a visually impaired father and three children—provides an intimate case study that illuminates the natural, home-based development of Polish language skills through everyday narrative practices. Case study methodology remains a valuable approach in heritage language research, as it allows for a detailed exploration of the particularities of family language policy and the lived experiences of individual households, rather than abstracting these dynamics into broad generalizations.

Turning to ecological approach in understanding multilingual upbringing (e.g., Brown, 2022; Schwartz, 2024), the study explores everyday linguistic practices of one Polish-speaking family in Finland. The ecological perspective adopted here, together with narrative analysis, is well suited to capturing the complexity of language use in a multilingual and multicultural family context. This approach enables attention to the interaction of multiple factors—family routines, parental attitudes, sibling relationships, and community resources—that shape how heritage language is maintained. Furthermore, the family in question has preserved informal records of their children’s speech development. While not systematic, these materials offer retrospective insights into the process of language acquisition and enrich the longitudinal depth of the case.

The family discussed here has been living in Finland since 2010. They are a nuclear family consisting of a husband (a medicine worker), wife (a teacher), and their three children: Jonatan, aged 12, and two daughters, Helena, aged 9, and Dobrawa, aged 6. The children’s names are pseudonyms. All three children were born in Finland. The parents moved to Finland for career reasons. Both parents are Polish, and Polish is the home language for the entire family, as well as the language spoken at home. Finnish and English are used outside the home. Additionally, the father is proficient in Italian, and the mother in Russian.

The children first attended a Finnish kindergarten, where some members of staff were Polish-speaking, although the primary language of instruction was Finnish. At the outset, limited use of Polish facilitated communication, but this was quickly replaced by exclusive use of Finnish. By the age of four to five, English had been introduced as part of the regular afternoon programme. They subsequently enrolled in a Finnish school, where their grades in Finnish are consistently at the highest level. All three children study English, and the two eldest additionally study Swedish. The eldest son also participates in choral singing in Latin and German. Their individual interests reflect a wide range of intellectual and cultural engagements. Jonatan demonstrates a strong orientation toward technology, computer science, mathematics, and chemistry. Helena is interested in knitting, literature, handicrafts, nature, and animals, and also engages in music and performance through playing the kantele—a traditional Finnish string instrument—and contemporary dance. Dobrawa’s interests include nature, horses, ballet, climbing, and violin.

Although the children’s overall language development has been documented comprehensively through diaries, artefacts, storytelling examples, and interviews with their parents, this study focuses specifically on the distinctive features of their narratives in Polish. By narrowing the scope to the Polish-language narratives, I aim to highlight how the children use their HL in storytelling, shedding light on the linguistic, cultural, and emotional aspects of HL maintenance. This focus allows me to explore in depth the ways in which narrative practices contribute to sustaining and developing Polish as a HL in the family context, without attempting to cover the entirety of their bilingual or multilingual development. A written consent from parents grants permission to record interviews and allow children to share stories in Polish. The children also consented to the publication of their images.

The narratives were analyzed within the specific social, cultural, and educational context (Clandinin, 2007; Mukherji & Albon, 2010). This allowed the study to explore how bilingual children interact with their environment and adapt to linguistic and cultural challenges. The structural analysis allowed to extract specific features of the oral texts as reflecting children’s personal and linguistic experiences (e.g., Ovchinnikova, 2005; Tappe & Hara, 2013). Palekha et al.’s (2018) work provided additional methodological insights into analyzing how educational practices interact with participants’ linguistic and cultural experiences.

4. Results

4.1. Interviews with Parents

In examining the language preservation practices of the Polish language within one family, the significant role of storytelling emerged as a key factor. The family makes different choices, including attendance at a Polish school and alternative schooling methods, reflecting diverse approaches towards language and education. The family being studied has one distinctive feature: due to the father’s blindness, the children are accustomed to constantly describing to him everything they see. Parents incorporated storytelling into daily routines, such as driving a car, going on a bus, bedtime stories, sharing family history, or creating new stories together. They encourage the use of home-language books, films, cartoons, and apps that are engaging for children. Attending language festivals, theater performances, or folklore events provides children with a broader context for their narratives especially if they recall the events for somebody who was not present there. Parents encourage storytelling in both oral and written forms, using diverse materials such as books, pictures, and prompts that inspire creative thinking. Parents nurture their children’s narrative skills by engaging in regular reading, asking open-ended questions about stories, and encouraging imaginative play that involves storytelling. Understanding a child’s narrative abilities can be an important part of assessing their language development. Early identification of difficulties in narrative skills can lead to timely interventions that support language and cognitive development.

The father tells the children many stories and characterizes their storytelling in the following way:

Concrete, technical descriptions—this is a specific feature of my son’s speech; when he sees the need for a detailed description, he will give it. If there is no need—no word (even if he knows the words). Our daughter speaks passionately and with emotion, focusing on the details that are important to her. She is talkative in both languages: Polish and Finnish. The youngest daughter is observant and has a keen eye for detail. She is organised and able to articulate her observations using appropriate language.

This prompted an inquiry into the children’s narrative abilities. Observations made during visits to the family revealed distinct personality differences: the eldest child exhibited reserved behavior, while the daughters were more talkative and open to communicating with a stranger.

The adults interrogated for the study think that when families tell each other many stories, their narratives become more detailed. The children learn to take into account their listeners’ perspective and clarify some aspects that are particularly important for them or remained vague for the listeners. All oral productive speech abilities are integrated into the narratives, which, of course, is not their only achievement. Sharing their knowledge with others fills them with pride in their heritage. The fact that others want to learn more about Poland and the Polish language can play a positive role.

Books are also highly valued in this family. There are many of them, in various languages, and they are looked at and read many times. The parents mentioned the importance of the books in their family. The mother’s reflections highlight the dynamic and evolving process of language development within a bilingual context, particularly in a Polish-speaking family in Finland. The parents’ reluctance to correct mistakes underscores a supportive environment that encourages self-expression and experimentation with language. However, the father is often asked about orthographic rules and explains grammar.

The children’s engagement with writing in Polish, even while growing up in a Finnish-dominant environment, reflects a strong intrinsic motivation to maintain their HL. Their choice to write voluntarily in Polish suggests not only a sense of personal connection and identity tied to the language, but also a desire to actively preserve and develop their skills in it. This willingness to use Polish in written form, despite the pervasive presence and social dominance of Finnish, highlights their internalized value of the HL and their resilience in sustaining it as part of their everyday lives. Such engagement demonstrates that HL maintenance is not merely a result of parental encouragement or external reinforcement, but also driven by the children’s own agency, creativity, and emotional attachment to their cultural and linguistic roots.

Each child’s creative initiatives—writing books in Polish, telling stories, and even producing phonetic approximations—showcase an active engagement with both languages. These activities not only foster literacy skills but also contribute to the maintenance of their cultural identity. The mother explains that

The children themselves create books in Polish. The elder wrote a cookbook, the middle one many stories: about teddy bear (in Polish), witches (in Finnish), animals (dictated book at a time when she could not yet write) while the younger, at six years old, composed a book about insects. She made multiple copies of the book and organized its presentation, detailing its contents. The writing had a phonetic nature, and when she began to read aloud, she realized there were errors in the writing. This initiative was so pleasing to me that I didn’t want to correct the mistakes, waiting for the older children to notice if something was amiss. In principle, she asks how to write, and Dad tells her, but she doesn’t know how to write nasal vowels. She thinks he is wrong because she writes nasal consonants separately, as two letters, and becomes very upset. Therefore, Dad decided to let her write as she wants, and wouldn’t correct her. The older children also write with mistakes, but fewer. The middle girl wants to learn everything properly. In general, she sees how it should be written, she has intuition. Not many mistakes influenced by the Finnish language, where writing almost always corresponds to oral pronunciation, rather it looks the same as with all children who write in Polish. The children read a lot in Polish themselves, quite in line with their age. Another case where children need to write in Polish is exchanging messages on WhatsApp with their grandparents and other members of Polish family. They sometimes come up and ask if they wrote correctly, if they can send it. According to preschool and school tests, Finnish language development is normal.

The mother’s decision not to correct the younger child’s errors, preferring to allow natural development and self-correction, aligns with a constructivist approach to learning, where children are given autonomy to explore and learn from their mistakes (e.g., Yan, 2024; Zajda, 2021, pp. 35–50). This approach encourages independence and critical thinking. By allowing mistakes to remain until the children themselves recognize them, the family supports the organic development of both phonetic awareness and writing skills in Polish. Something compels these children, so different in character, to feel a deep sense of belonging to their family, language, culture, and religion. Holding on to one another, helping each other, and taking joy in each other’s achievements become a shared and paramount task.

The children’s independent creation of Polish-language books reflects their initiative and engagement with language and literacy. The most prolific artist was the middle child, who produced a considerable number of stories. These included tales about teddy bears (in Polish), witches (in Finnish), animals (dictated books at a time when she could not yet write), as well as daily newspapers. These publications appeared intermittently and touched on everyday family life, as well as detective stories and even advertisements for imaginary places. The initiative for the publications always came from the children, yet the parents were eager to participate as readers of the books and newspapers (a home library with the option of borrowing copies was even established). Parents were occasionally involved in the selection of topics for home publications and as proofreaders of language accuracy and initial reviewers.

4.2. A Self-Made Book

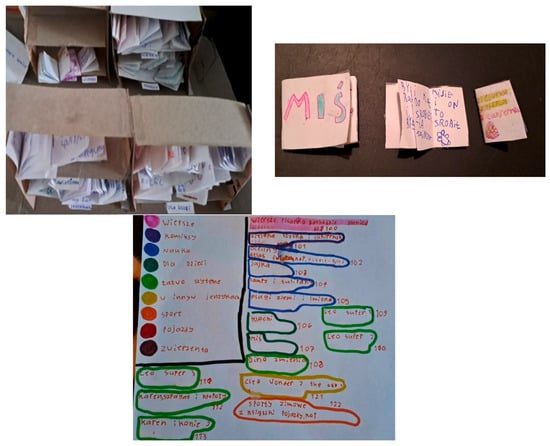

Dobrawa likes insects, and, at the age of six, she composed her own book about insects (Figure 1). She even produced multiple copies of the book and arranged for its presentation. In what follows, her mistakes in Polish are explained.

Figure 1.

The book made by Dobrawa: cover and two pages.

Kśonszka z owadami—the correct version should be Książka z owadami. Dobrawa makes a typical mistake—typical of children living in Poland and in a second language environment—phonetically transcribing the word książka replacing si by ś, the nasal vowel ą by on and finally, ż by sz. The letter Z appears as its mirror image.

On the next pages Dobrawa gives names of the insects. BIEDRONKA is a correct version, MRUFKA should be mrówka, ów is perceived as uf. SZUK should be żuk, ż is replaced by sz (the letter s is a mirror image). PSZĆOŁA appears instead of pszczoła where cz is replaced by ć. BONK should be bąk, again, the nasal vowel ą is spelled phonetically as on, which is phonetically correct because before the consonant k, ą sounds as on. DŻDŻOWNIDŻDŻA should be dżdżownica. Hypercorrectness can occur when relying heavily on spell-checking and trying to recall memorised word. It happened here that the child asked her father for help, and he showed her the correct pattern of the word, whereas the child was trying to memorise and reproduce it. MUHA should be mucha, so, here we deal with a typical orthographic mistake when h and ch are confounded. KONISKA MUHA should be końska mucha, ń is transcribed as ni, and the same typical orthographic mistake is repeated.

It is important to note that typical difficulties in Polish spelling affect all children mastering the language, whether it is their native or HL. Moreover, they are difficult for adults learning Polish as a foreign language. These include incorrectly transcribed nasal vowels ą, ę, of the silent/soft alveolo-palatals ś, ź, ć, dź, humming of the postalveolar sounds sz, ż, cz, dż, and hissing sounds, alveolar series s, z, c, dz, as well as orthography rules of the use of rz/ż, ó/u, ch/h. So, there is nothing special in Dobrawa’s spelling as compared to other children of the same age (Maliszewski, 2020).

Recently, Helena (aged 11) and Dobrawa (aged 8) undertook a substantial project by creating a mini-library (Figure 2). The collection consists of 28 books in Polish and one in Finnish, which they either authored themselves or adapted, with permission, from existing Polish publications. Notably, despite the original intention to include books in several languages, the children chose to produce the library predominantly in Polish. In addition, four English-language books contributed by a friend are also included. The library is organised with a cataloguing system, and books may be borrowed; parents and friends have even been issued library cards.

Figure 2.

A mini-library and a part of its catalogue (with a few orthographic errors).

Polish orthography differs significantly from Finnish. Finnish generally exhibits a fairly consistent correspondence between letters and sounds, with long vowels indicated by double letters. In contrast, Polish includes digraphs, diacritical marks (both above and below letters), and nasalized vowels, resulting in a more complex orthographic system. These differences can pose challenges for bilingual children learning to read and write in both languages, as they must navigate distinct phoneme–grapheme correspondences and develop separate literacy strategies. Awareness of these orthographic contrasts is therefore essential for parents and educators supporting heritage language maintenance, particularly in fostering reading fluency, spelling accuracy, and written expression in Polish.

4.3. Narratives of the Three Children in Polish

Research on HL narrative development focuses on understanding how individuals construct and express their understanding of the situation through the narratives associated with their HL (e.g., Minkov et al., 2019; Rodina et al., 2023). This area of study employs various methodologies, including narrative ethnography and life history analysis, to explore the complexities of language acquisition and identity formation across different contexts. Each of the children was separately asked to tell a story based on the book “Knock, knock, knock!” which they have read (Tidholm, 1992). The English text did not disturb the storytelling. All children’s narratives were recorded, transcribed and analysed.

In employing picture book narratives as a primary method for eliciting linguistic material, I relied on two ecologically valid considerations. First, storytelling and shared book reading, including reading aloud, are well-established practices within the family, which ensured that the elicitation task was naturalistic and aligned with their everyday language use (Heath, 1983; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2002). Second, the book itself is deliberately open-ended: while it contains an introduction and a conclusion, it lacks both a climax and an explicit moral. This structural indeterminacy creates space for multiple interpretations and thus provides a productive context for examining how children construct narratives, negotiate meaning, and mobilize their linguistic resources in a heritage language setting (Berman & Slobin, 1994; McCabe & Bliss, 2003).

The book was unfamiliar to the children. Each child was interviewed individually, during which they explored the book and narrated its content. Subsequently, the youngest girl chose to retell the story independently. Participation was entirely voluntary, and the children engaged in the task willingly, demonstrating intrinsic motivation for the activity.

4.3.1. Child I, Dobrawa (6 Years Old)

In her first storytelling session (Appendix A), Dobrawa focused on the guiding element of the book—the doors, in Polish drzwi—that lead to and open up other spaces presented in the book. The speaker—Dobrawa omits or minimises descriptions of the elements that inhabit the spaces. For this reason, the child was asked to add some other stories in order to show better the six-6-year-old’s real potential of language imagery and verbal description. Later, Dobrawa proposed to repeat her story.

In her second narrative session (Appendix B), Dobrawa chooses words efficiently, which improved the fluency of her utterances. She enumerates all the elements of the pictures which she previously omitted and uses very good grammatical and lexical forms, with two exceptions: Na bębienie—instead of na bębnie (locative form of bęben = drum); the incorrect form kwiatka in the connotation with the verb podlewać (to water) + acc, should be kwiatek. We see the incompatibility of grammatical gender in the phrase jakaś… nocnik. Perhaps the latter mistake is caused by the choice of the correct word, which turned out not to be a bowl/thing (in the feminine gender), but a pot is in the masculine.

There were two instances where she hesitated a little bit before choosing the right word for the picture. In the first story, she had trouble deciding on the name of the monkeys’ play area, whether it is a bedroom or something else, and the word remains unpronounced until the end and is replaced by the little house. In the second story, in the description of the teddy-bears’ bedroom, Dobrawa experienced difficulty in naming the activity that her parents were engaged in. The child hesitates between choosing the word they brush their teeth/apply toothpaste or they put the brushes in the cups. The choice falls on the last expression, which is the most accurate description of what is shown in the picture. The hesitation is therefore not due to unfamiliarity with the lexicon, but to reflections on the correct choice of the word(s).

4.3.2. Child II, Helena (9 Years Old)

Helena (see Appendix C) demonstrates cause and effect thinking by constructing long statements. For example, she remarks that one of the rooms in the house she talks about serves as a laundry because there is a washing machine there. This may be because the room is the only large space available, rather than being part of a larger house.

The narrator not only recounts what she sees but also provides explanations about the construction of the book. The book features a different family behind each door, and Helena pays attention to details such as the slanted window and different colored teddy bear cots. Additionally, the interpreter notes the imbalance of proportions between the plant and human, with the huge flower being particularly noteworthy (She mentions it twice).

Helena also observes the similarity between the first and last pages of the book and questions the author ‘s intention. Finally, she wonders why the house is placed in relation to the road and tree in a strange way. She emphasizes that the house should be located where it is comparing with the first picture.

Helena’s story is free of lexical or grammatical errors. However, a certain shortcoming is an excessive use of the informal word no in Polish, an equivalent to well in English, which may indicate uncertainty or hesitation or a nervous attitude, especially at the beginning of the recording. According to her parents’ observations, in everyday speech, Helena does not overuse this interjection.

4.3.3. Child III, Jonatan (12 Years Old)

Jonathan (Appendix D) expresses himself concisely and strives to complete tasks quickly. He does not get emotional about the book which was discussed; rather he emphasises that nothing about it is out of the ordinary, e.g., ee takie normalne (‘yeah’ so normal’). The words takie, jakieś, w ogóle, and no i tyle (‘normal’, ‘such’, ‘some’, ‘in general’) highlight the laconic nature of the narration and the speaker’s reluctance to develop descriptions. Perhaps for a boy of his age, the book discussed was too simplistic, that is why he did not want to sound childish while narrating. Interestingly, he does not use any terms related to colours (which appears to be significant in the story for Child I and Child II; it van be age-related, gender-related, or something else). It is most probable that the issue is related to age, gender or character. Jonathan’s father has noted that the boy’s speech is focused on practical matters, and it is likely that the colours are not a part of this. The recurring motif of the door is taken in a tongue-in-cheek manner, reflected by the use of the word wrota ‘gate’ instead of a ‘door’, which adds a sense of humour to his speech. In Polish the word ‘wrota’ is used only to the buildings such as castle, temple or to describe the huge entrance to the old house.

Jonathan’s narrative has traces of cause-and-effect reasoning. Thus, somebody spilled some water, possibly indicating that the water jumped or was knocked over by the child—Jonathan concluded. Additionally, he mentions monkeys and their disruptive behaviour, suggesting that something was causing them to shout and play around. He omits certain details that he deems less important, such as the presence of teddy bears in the bedroom. Instead, he focuses on presenting the functions of the room. Similarly, he briefly mentions the kitchen and its contents, such as a bucket and a washing machine, without going into details unnecessary, in his opinion, e.g., he does not mention rabbits. His speech is flawless both lexically and grammatically. One shortcoming of the text is the overuse of expressions such as jakiś, jakaś, and jakieś (“some”, ”those”, without making clear what they refer to).

4.3.4. Summary

After collecting the children’s stories, feedback from colleagues who are native Polish speakers and the specialist indicated that the narratives aligned with the appropriate developmental characteristics for their age. Before, this book was already used to explore the early literacy practices in multilingual settings, stressing how preschools can actively utilize resources from diverse linguistic communities to foster communication and learning opportunities (Samuelsson, 2023).

In her initial story, Dobrawa focused mainly on the book’s key element, the doors, while minimizing the elements within the spaces. In a supplementary story, she provided more detailed descriptions, using correct grammatical and lexical forms with just a few minor errors. Her storytelling showed efficient word choice and fluency, reflecting a thoughtful approach to language (the evaluation of fluency was conducted on the basis of the author’s knowledge of the Polish language, as she is a native speaker and specialist). Helena demonstrated cause-and-effect thinking and provided detailed explanations about the book’s construction, noting elements like slanted windows and teddy bear cots. Her narrative was free of lexical or grammatical errors, though she overused the informal Polish word ‘no’, which could be a sign of hesitation. She observed similarities between the beginning and the end of the book, questioning the author’s intentions. Jonathan’s narration was concise and focused on the ordinariness of the objects appearing in the book, possibly finding the book too simplistic for his age. He resorts to humour when referring to doors as ‘gates’ and displayed cause-and-effect reasoning. His speech was grammatically flawless but lacked detail, often using vague terms like ‘some’ and ‘those’ without specifying referents. All three narrators use informal, though elaborate language and fillers; they convey a basic visual and functional understanding of the domestic environment. The improvised narratives contribute to a sense of spontaneity and attempt to find meaning in an absurd story.

Table 1 compares children’s texts in terms of length and lexical variety.

Table 1.

The characteristics of children’s texts.

The youngest girl was able to expand upon her initial version and performed better in the second attempt. The older sister tends to speak at greater length, whereas the eldest brother, for example, may condense the story by omitting details. These characteristics are typical of their respective ages. The narratives demonstrate their readiness to use Polish, at least orally. The book created by the youngest child is evidence of her desire to use Polish creatively in written form as well.

5. Discussion

Although motivation is often treated as a single construct, even superficial reflection suggests that people are moved to action by very different factors, encounter different experiences and consequences. People can be motivated because they value a particular activity or because there is a strong external compulsion. The question of whether individuals act in accordance with their own interests and values or are driven by external factors is an important topic in any culture (e.g., Johnson, 1993). It represents a fundamental aspect through which individuals make sense of their own and others’ behaviour (de Charms, 1968; Heider, 1958; R. Ryan & Connell, 1989). People can be motivated because they value a particular activity or because there is a strong external compulsion.

Narrative elicitation is particularly valuable in HL research because it captures spontaneous, extended language production rather than decontextualized vocabulary or grammar drills. It enables analysis of how children draw on multiple linguistic repertoires, how they organize discourse, and how they express identity through storytelling (Montrul, 2016; Pavlenko, 2007). In addition, narratives are sensitive to both linguistic and cultural dimensions of bilingual development, offering insight into how heritage speakers integrate structural competence with culturally embedded modes of expression.

The children’s storytelling in this study can be discussed through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (R. M. Ryan & Deci, 2000), focusing on the psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are crucial for language learning. The concept of relatedness—the sense of being connected and valued by others—played a pivotal role in the children’s storytelling, as seen in their willingness to share their inherited Polish language through narratives with their family and community. This relational aspect underpins their engagement with the language, fostering a deeper connection to their Polish heritage.

In terms of competence, the children’s storytelling activities demonstrate their growing ability to convey stories effectively, reinforcing their identity as Polish speakers. Their sense of mastery over the language, even when sharing it within a predominantly Finnish and English-speaking environment, shows that they see themselves as capable and confident in their linguistic abilities. This aligns with studies such as Montrul (2016); Polinsky and Scontras (2020); Rodina et al. (2023), which emphasize the importance of early exposure to a HL for developing lexical, grammatical, and phonological skills.

Autonomy is also key in the children’s narrative development. Their independent engagement with storytelling, whether in written or oral form, reflects their intrinsic motivation to explore and express themselves in Polish, without external pressure. Autonomy is vital for maintaining sustained interest and creativity in language use (R. M. Ryan & Deci, 2000). Comparisons between individuals whose motivation is authentic (i.e., self-induced or endorsed) and those who are merely externally controlled for an action typically reveal that the former, are more involved, interested, and confident than the latter. This, in turn, is manifested both in enhanced performance, persistence in reaching the goal, and creativity (Deci & Ryan, 1995). Sheldon et al. (1997) and Nix et al. (1999) found that intrinsic motivation was associated with heightened vitality, self-esteem, and general well-being. By allowing children to create and control their own narratives, parents support their self-directed language learning. The pattern is clearly observed in this study: Dobrawa clearly rephrases and restructures her text making it more concise and logical.

These cognitive abilities are essential for processing and producing coherent language and highly motivating for learners while providing a context that makes language learning exciting and meaningful, encouraging sustained effort and interest (Rezende Lucarevschi, 2016). Narratives facilitate communication skills by requiring learners to organize their thoughts, convey messages clearly, and respond to listeners’ feedback; thus, fostering effective conversational abilities. That is why narrative development is integral to language acquisition. For instance, Helena’s cause-and-effect reasoning (about laundry, kitchen) adds to the understanding of her inner connectedness to the story and her assessment of events in the picture book.

Moreover, storytelling plays a significant role in the children’s linguistic and cognitive development. For example, we see how the details are becoming more and more important for Dobrawa. As children construct and share stories, they practice using varied grammatical structures and tenses, thereby enhancing their overall language proficiency, as observed by Flores et al. (2022) in bilingual Portuguese-German children. This narrative practice also supports the development of cognitive skills such as sequencing and inferencing, which are critical for both storytelling and language acquisition (Mar et al., 2021; Navas & Vianna, 2024). As the stories illustrate, narratives require a wide range of words, from concrete objects to abstract concepts, helping children practice more complex language forms. Storytelling pushes children to use more advanced grammar, such as tenses, sentence structure, and connectors, fostering linguistic development in Polish.

Finally, these narratives are not only linguistic exercises but also cultural ones, helping the children capture and represent their Polish heritage. As noted by Barglowski (2019) and Wieczorek (2018), storytelling is deeply tied to cultural identity, and by engaging in storytelling, the children are preserving and sharing their cultural roots. Thus, the combination of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their narrative activities supports both their linguistic and cultural development, offering insights into how intrinsic motivation and narrative competence drive HL maintenance.

This study has some limitations. It focuses on a single Polish-speaking family in Finland, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The experiences and practices observed may not represent those of other multilingual families or Polish families in different sociocultural contexts (cf. Moin et al., 2013). While primarily examining Polish language preservation, it potentially overlooks interactions with other languages (Finnish and English) and cultural influences that may affect multilingual upbringing. It lacks longitudinal data, which could provide insights into the long-term effects of the family’s language practices on children’s language development and cultural identity. The narrative analysis relies heavily on subjective interpretations of storytelling and language use, which could introduce bias or overlook nuanced linguistic and cultural dynamics.

6. Conclusions

This study has examined the maintenance of Polish as a HL among families in Finland in a case study of one family, with particular attention to the role of storytelling practices in supporting children’s linguistic and cultural development. By highlighting how narratives foster both language proficiency and a sense of identity, the findings contribute to broader HL research that emphasizes the importance of family language policy, intergenerational practices, and educational support (e.g., Spolsky, 2012). The study shows that while institutional and community provisions create favourable conditions for Polish language transmission, parents’ conscious engagement remains the decisive factor in sustaining children’s proficiency and attachment to their heritage language. Children’s self-determination and autonomous learning, fostered within a supportive family environment, emerge as key factors motivating the maintenance of the HL.

The study demonstrates that storytelling can serve as an effective tool for heritage language maintenance. By engaging children in reading, analyzing, and narrating picture books and folktales, parents and educators can foster the development of fluent speech, rich vocabulary, and logical narrative structure in Polish. Such practices not only reinforce children’s emotional connection to the language but also support broader cognitive functions—including memory, critical thinking, and imagination—which in turn contribute to academic achievement. Developing narrative skills orally further encourages engagement with written Polish, enhancing literacy and strengthening the use of the home language as an intellectual and cultural resource.

The Polish diaspora’s commitment to preserving their cultural and linguistic heritage in foreign environments not only enriches their own communities but also deepens the broader understanding of how diasporas contribute to cultural preservation. A strong sense of belonging motivates children—regardless of age or individual character—to engage in producing texts in Polish, which fosters the highest possible level of language development. These efforts exemplify the resilience of diaspora communities as they navigate the challenges of living abroad while striving to keep their heritage alive.

Future research could include a larger and more diverse sample of multilingual families from different cultural backgrounds and regions to enhance the generalizability of findings. Conducting longitudinal studies to track language development and cultural identity over time would provide deeper insights into the impacts of multilingual upbringing. Other instrumental devices can be involved (e.g., Yang et al., 2025). Comparing the linguistic practices and narrative abilities of children in multilingual households with those in monolingual environments could highlight challenges and advantages of multilingual upbringing.

In sum, this study underscores the significance of everyday storytelling as a resource for maintaining Polish in the diaspora. It advances our understanding of how HLs can be supported not only through formal instruction but also through intimate, family-based practices that nurture children’s linguistic, cognitive, and cultural development. In doing so, it contributes to ongoing debates in heritage language studies about the conditions under which minority languages can be sustained across generations in multilingual settings.

Funding

No extra funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human samples in accordance with the Ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland issued by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK) in 2019 because the study did not involve intervening in the physical integrity of research participants, did not expose research participants to exceptionally strong stimuli, and does not entail a security risk to the participants or their family members.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and methods in the manuscript are presented with sufficient detail. Other researchers can replicate the procedure. However, the data is not publicly available due to ethical reasons. If the readers have any questions, they can address the author per e-mail.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the family who participated in the project, especially the children who generously shared their valuable materials and creations. Thank you for letting me into your lives. Dziękuję serdecznie!

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Dobrawa 1

Domek i dróżka i tak samo na górze jest… niebo i trawa na dole. Tutaj są drzwi… z klamką! Potem jest dziecko, które…hmmpotem jest pokój, w którym jest też, też są drzwi. Potem drugie drzwi z klamką. Potem jest kuchnia i… drugie drzwi z klamką. Potem jest ma…do,d…yyy…. sypial… domek—i znów drzwi z klamką. I dom i drzwi z klamką. Potem jest sypialnia i drzwi z klamką. A potem jest noc z trawą, księżycem i niebem. KONIEC

The English translation: The house and the pathway and so at the top is… (small pause) sky and grass below. Here is a door (pause)… with (! heavily accented) handle. Then there is a child who…hmm (This is likely to be the moment when the speaker changes the focus of attention from the persons and objects presented in the story to the main element—the door) then there is a room where there is also, also there is a door. Then a second door with a handle. Then there is a kitchen and …a second door with a handle. Then there is a ma… do, d… yyy … Bedroom… (the child doesn’t finish the word, but replaces it with the word: cottage)—and again a door with a handle. And a house and a door with a handle. Then there is a bedroom and a door with a handle. And then there is night with grass, moon and sky. END

Appendix B. Dobrawa 2

Tutaj jest pokój, w którym jest dywan, drzwi, łóżko, obraz, dziecko, które gra na bębienie, piłka, wanna, szczotka i obraz, i samochód, i ten jakaś… nocnik. Potem jest kuchnia, w której jest pralka, rozwieszone pranie na sznurku; też drzwi, krzesła, stół, króliki, które jedzą obiad, lampa, wiaderko i kuchenka i ten… garnek. Potem są małpy, które są/ bawią się poduszkami, i tam też są drzwi i jest też drzewo. Potem jest domek, dom, w którym jest jedzenie dla kota, kot, krzesło, stół, woda, dywan, drzwi. Dziadek podlewa kwiatka, i okno i miska—w misce picie dla kota i jedzenie dla kota. Potem jest sypialnia, gdzie są misie. Trzy małe misie śpią w łóżkach, potem jest też tam drzwi w tej sypialni, potem jest dywanik. Tata i mama myy… nak… myy,… yyy… wkładają szczotki do kubków. I są jeszcze dwa łóżka, i lampa i umywalka i i …i… tyle. A tutaj jest droga, drzewo, i ten… księżyc, niebo i yyy ta …trawa. KONIEC

The English translation: Here is a room with a carpet, a door, a bed, a painting, a child who plays the drum, a ball, a bathtub, a brush and a painting, and a car, and this yak potty. Then there is the kitchen, in which there is a washing machine, hanging laundry on a string; also a door, chairs, a table, rabbits that eat dinner, a lamp, a bucket and a cooker, and this… pot. Then there are monkeys that are/play with cushions, and there is a door and there is also a tree. Then there is a house, a house where there is food for the cat, a cat, a chair, a table, water, a carpet, a door. Grandpa watering a flower, and a window and in a bowl—a bowl drinking for the cat and food for the cat. Then there is the bedroom, where the bears are. Three little teddies are sleeping in beds, then there is also a door in that bedroom, then there is a rug. Dad and mum myy…nak…myy,…yyy….. they put the brushes in the cups. And there are two more beds, and a lamp and a washbasin and and…and… so much. And there’s a road, a tree, and this… moon, sky and yyyy this… grass. END

Appendix C. Helena

No… No tu jest taki malutki domek z ogromnym drzewem i z malutkim drzewem—no taki dom, a nie. No i za nim są góry. Wygląda jakby był sam w tych wszystkich górach—trochę. No tu są niebieskie drzwi, a tu jest jakiś chłopiec, który jest w pokoju, który wygląda trochę jakby właśnie wyszedł z mycia. Tu jest fajne, nie?—pokazuje wanienkę z rozchlapaną wodą—tu jest łóżko, no i ma zabawki tu. Tu są drugie drzwi tylko czerwone. Tu wygląda jakby wszystkie króliki… tutaj mają pranie, tu pralkę—pewnie dlatego tu jest pranie, bo, tak jakby, może mają tylko taki jeden wielki pokój—a nie taki wielki dom—tu mają kuchnię, a tu chyba jedzą wszyscy -cała rodzina przy stole, jedzą marchewki. Tu są zielone drzwi. I tu jest znowu—za każdymi drzwiami jest inna rodzina—i tu jest rodzina małp, które wiszą na drzewie i rzucają się poduszkami. Tu są żółte drzwi i to wygląda jakby była rodzina, wiesz- takiego pana i kota. Tu jest karma, tu jest woda i takie, to okno jest na pewno według mnie tak przechylone i kwiatek ogromny. No i taki zegar i ogromny kwiatek i krzesło. To są białe drzwi i tu jest rodzina misi—to jest chyba, jest ich taki malutki pokój, gdzie śpią i takie malutkie te drzwiczki, ale dobra, tu są trzy misie, które śpią. A tu mama i tata myją jeszcze zęby i pójdą spać. Każdy ma inne łóżeczko kolorowe, oprócz tego- ich rodziców. Tu są niebieskie drzwi (chyba już były). I tu jest ta droga—tu nie powinien być ten domek? Bo tu jest to drzewo—samo. Tu chyba powinien być ten domek.

No taka droga. I koniec książki.

The English translation: Well (I read about the first page with the text…—whispered). Well, there’s a tiny house with a huge tree and a tiny tree—well a house, isn’t it? Well, and there are mountains behind it. He looks like it’s alone in all those mountains—a bit. Well here’s a blue door, and here’s some boy who’s in a room that looks a bit like he’s just come out of the wash. Here’s cool, isn’t it?—the speaker is pointing to a tub and splashed water—here’s a bed, well he’s got toys here (shows the right picture). Here is the other door, only red. Here it looks like all the rabbits… here they have laundry, here they have a washing machine—that’s probably why there’s laundry here, because, like, maybe they only have this one big room—not this big house—here they have a kitchen, and here I think they all are eating—the whole family at the table, they are eating carrots. Here is the green door. And here it is again—there is a different family behind each door—and here is a family of monkeys, who are hanging from a tree and throwing the pillows. Here’s the yellow door and it looks like there’s a family, you know-such a gentleman and a cat. There’s cat’s food here, there’s water and such, this window is definitely, in my opinion, so tilted and a huge flower. And such a clock and a huge flower and a chair. This is the white door and here’s a family of teddy bears—this is, I think, there’s their kind of tiny room where they sleep and this kind of tiny this door, but okay, here’s three teddy bears that sleep. And here’s mummy and daddy brushing their teeth still and going to bed. Everyone has a different coloured cot, except this one- their parents’ ones. Here’s the blue door (I think it’s been there before). And here is this road—shouldn’t this house be here? Because here is the tree—alone (compares with the first picture). Here, I think there should be this house (adds with emphasis). Well, this is the road. And the end of the book.

Appendix D. Jonatan

Jest tu jakiś domek, takie drzewko, tam jakieś chmury, jakaś droga. Tu są jakieś drzwi, klamka, nie? Tu jakieś dziecko z jakimś bębnem, tu jakaś woda—woda się rozlała (pewnie skakało /w domyśle dziecko) tu jest jakieś tam łóżko -ee (wyraża dezaprobatę)takie normalne. To są znów jakieś wrota no i potem jest jakaś—chyba to kuchnia—tu jakieś wiadro, jakaś pralka czy co tam, ubrania—no i tyle. Tu są jakieś drzwi i jakieś małpy—coś tam rozrabiają, krzyczą i w ogóle. Tu są znowu jakieś drzwi no i tam jest jakiś mały ludzik i jakiś kot coś tam je hmmm też jakieś małe drzwi, jakiś zegar, takie. Tu są znowu drzwi no i potem jest tam jakaś sypialnia, gdzie tam ludzie śpią, myją zęby. Tam są znowu jakieś drzwi i jest jakaś droga i to koniec.

The English translation: There’s a house here, a tree like this, some clouds there, some road. Here is some door, a handle, isn’t it? Here some child with some kind of drum, here some water—water spilled (probably jumped/implied a child) here there is some kind of bed -ee (shows a little disapproval) such a normal one. Here are some gates again, aren’t they? And then there’s some—I guess it’s a kitchen—here some bucket, some washing machine or whatever, clothes—and that’s it. There’s a door and some monkeys—they’re messing around, shouting and stuff. Here’s another door and then there’s a little man and a cat eating something hmmm also some little door, some clock, that kind of thing. There is another door and then there is a bedroom, where people sleep, brush their teeth. There’s a door again and then there’s a road and that’s it.

References

- Andreou, G., & Lemoni, G. (2020). Narrative skills of monolingual and bilingual pre-school and primary school children with developmental language disorder (DLD): A systematic review. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 10(5), 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banasiak, I., & Olpińska-Szkiełko, M. (2021). Sociolinguistic determinants of heritage language maintenance and second language acquisition in bilingual immigrant speakers. Glottodidactica, 47(2), 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, K. (2019). Cultures of transnationality in European migration: Subjectivity, family and inequality. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, R., & Slobin, D. (Eds.). (1994). Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bitetti, D., & Hammer, C. S. (2016). The home literacy environment and the English narrative development of Spanish-English bilingual children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(5), 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitetti, D., & Hammer, C. S. (2021). English narrative macrostructure development of Spanish-English bilingual children from preschool to first grade. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(3), 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudreau, D. (2008). Narrative abilities: Advances in research and implications for clinical practice. Topics in Language Disorders, 28(2), 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. (2022). Linguistic ecology and multilingual education. Estonian Journal of Education, 10(2), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. (2015). The development of bilingual children’s narrative skills: A report of the “Looking Glass Neighborhood” Program. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 38(3), 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. J. (Ed.). (2007). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cleave, P. L., Girolametto, L. E., Chen, X., & Johnson, C. J. (2010). Narrative abilities in monolingual and dual language learning children with specific language impairment. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43(6), 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J., & Swain, M. (2014). Bilingualism in education: Aspects of theory, research and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Curdt-Christiansen, X. L., & Palviainen, Å. (2023). Ten years later: What has become of FLP? Language Policy, 22, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Charms, R. (1968). Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behaviour. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1995). Human autonomy: The basis for trueself-esteem. In M. Kemis (Ed.), Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem (pp. 31–49). Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Del Negro, J. M. (2014). Folktales aloud: Practical advice for playful storytelling. American Library Association. [Google Scholar]

- Dębski, R. (2016). Dynamika utrzymania języka polskiego w Australii. Postscriptum Polonistyczne, 17(1), 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Djundeva, M., & Ellwardt, L. (2020). Social support networks and loneliness of Polish migrants in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(7), 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobinson, K. L., & Dockrell, J. E. (2021). Universal strategies for the improvement of expressive language skills in the primary classroom: A systematic review. First Language, 41(5), 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J. (1991). Reversing language shift: Theory and practice of assistance to threatened languages. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C., Rinke, E., Torregrossa, J., & Weingärtner, D. (2022). Language separation and stable syntactic knowledge: Verbs and verb phrases in bilingual children’s narratives. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagarina, N., & Bohnacker, U. (2022). Storytelling in bilingual children: How organization of narratives is (not) affected by linguistic skills and environmental factors. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 12(4), 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagarina, N., Klop, D., Kunnari, S., Tantele, K., Välimaa, T., Balčiūnienė, I., Bohnacker, U., & Walters, J. (2012). Multilingual assessment instrument for narratives (MAIN). ZAS. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, S. (2005). Beyond Warsaw: Polish policy towards Polish communities abroad. Osteuropa, 55(2), 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Helsinki. (2025). Childhood and education. Curriculum, school subjects and assessment/Mother tongue studies. Available online: https://www.hel.fi/en/childhood-and-education/basic-education/comprehensive-school-studies/curriculum-school-subjects-and-assessment (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Istanbullu, S. (2024). Agency through conversational alignment in transnationalfamilies: Shaping family language policy. SN Social Sciences, 4, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubek-Głąb, I. (2024). Polish language maintenance and transmission in Finnish diaspora: A study of family dynamics and cultural influence. Languages, 9(12), 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F. (1993). Dependency and Japanese socialization. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, S. M. (2015). Narrative development of school children. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- King, K. A., Fogle, L., & Logan-Terry, A. (2008). Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(5), 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesińska, M. (2018). Polska diaspora, polonia, emigracja. Spory pojęciowe wokół skupisk polskich za granicą. Polski Przegląd Migracyjny, 1(3), 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, J., Tselekidou, F., & Gagarina, N. (2023). Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives: Recent developments and new language adaptations. ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 65, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewski, B. (2020). Uczyć się „od błędów”—Analiza uchybień w pisemnych pracach uczniów szkół polonijnych w USA. Półrocznik Językoznawczy Tertium, 5(1), 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Mar, R. A., Li, J., Nguyen, A. T. P., & Ta, C. P. (2021). Memory and comprehension of narrative versus expository texts: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, A., & Bliss, L. S. (2003). Patterns of narrative discourse: A multicultural life span approach. Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Minkov, M., Kagan, O., Protassova, E., & Schwartz, M. (2019). Towards a better understanding of a continuum of heritage language proficiency: The case of adolescent Russian heritage speakers. Heritage Language Journal, 16(2), 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, V., Schwartz, L., & Leikin, M. (2013). Immigrant parents’ lay theories of children’s preschool bilingual development and family language ideologies. International Multilingual Research Journal, 7(2), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2016). The acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, L., Reilly, K., & Brady, B. (Eds.). (2021). Narrating childhood with children and young people diverse contexts, methods and stories of everyday life. Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji, P., & Albon, D. (2010). Research methods in early childhood. An introductory guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen, R., Torppa, R., & Stolt, S. (2024). Parental linguistic support in a home environment is associated with language development of preschool-aged children. Acta Paediatrica, 113(8), 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navas, D., & Vianna, M. D. P. (2024). Contemporary literature for children and youngsters: Plural space(s). Revista De Estudos Do Discurso, 19(3), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K. M., & Hayes, B. (2019). A real-world application of Social Stories as an intervention for children with communication and behaviour difficulties. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(4), 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikova, I. (2005). Variety of children’s narratives as the reflection of individual differences in mental development. Psychology of Language and Communication, 9(1), 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Palekha, E. S., Bastrikov, A. V., Bastrikova, E. M., & Zharkynbekova, S. K. (2018). The objective methods of linguistic analysis. In Dilemas contemporáneos: Educación, política y valores VI (Special) (pp. 1–11). Art. 52. Asesorías y Tutorías para la Investigación Científica en la Educación Puig-Salabarría S.C. [Google Scholar]

- Pauls, L. J., & Archibald, L. M. (2021). Cognitive and linguistic effects of narrative-based language intervention in children with developmental language disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, M., & Scontras, G. (2020). Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonia. (2017). Ogół Polaków, którzy wyjechali za granicę lub już urodzili się za granicą, jednak pielęgnują polskie tradycje, interesują się polską kulturą i przejawiają zrozumienie dla polskich spraw. Available online: https://wsjp.pl/haslo/podglad/87282/polonia (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Polonia Statistics. (2024). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/polonia/historia (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Protassova, E. (2021). Dynamics of stories of bilingual children: Problems and practice. Preschool Education Today, 5(15), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende Lucarevschi, C. (2016). The role of storytelling on language learning: A literature review. Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle of the University of Victoria, 26(1), 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rodina, Y., Bogoyavlenskaya, A., Mitrofanova, N., & Westergaard, M. (2023). Russian heritage language development in narrative contexts: Evidence from pre- and primary-school children in Norway, Germany, and the UK. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanowski, P., & Seretny, A. (Eds.). (2024). Polish as a heritage language around the world: Selected diaspora communities. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R., & Connell, J. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, L. E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, R. (2023). Creating a web of multimodal resources: Examining meaning-making during a children’s book project in a multilingual community. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 25(3), 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M. (2024). Ecological perspectives in early language education: Parent, teacher, peer, and child agency in interaction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M., & Verschik, A. (Eds.). (2013). Successful family language policy: Parents, children and educators in interaction. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Scionti, N., Zampini, L., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2023). The relationship between narrative skills and executive functions across childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children, 10(8), 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J.-A. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73(2), 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Rawsthorne, L. J., & Ilardi, B. (1997). Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the Big Five traits and its relations with authenticity and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoczyńska, M. (2000). The case of Sławuś: An atypical development of first person self-reference in Jan Baudouin de Courtenay’s Polish diary data. Psychology of Language and Communication, 4(2), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. (2012). What is language policy? In B. Spolsky (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of language policy (pp. 3–15). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M. A., & Ward, G. C. (2005). Supporting the narrative development of young children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33(2), 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Finland. (2024). Available online: https://pxdata.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/Maahanmuuttajat_ja_kotoutuminen/Maahanmuuttajat_ja_kotoutuminen__Maahanmuuttajat_ja_kotoutuminen/maakoto_pxt_11vv.px/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Tappe, H., & Hara, A. (2013). Language specific narrative text structure elements in multilingual children. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, 42, 297–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidholm, A.-C. (1992). Knacka på! [Knock, knock, knock! 2000] (G. Berggren, Trans.). Alfabeta. [Google Scholar]

- Tilstra, J., & McMaster, K. (2007). Productivity, fluency, and grammaticality measures from narratives: Potential indicators of language proficiency? Communication Disorders Quarterly, 29(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, G. (2017). From language maintenance and intergenerational transmission to language survivance: Will “heritage language” education help or hinder? International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 243, 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, L., & Stromqvist, S. (Eds.). (2004). Relating events in narrative: Typological and contextual perspectives. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vickrey, R., Tyson, B., & Nicholas, V. (2019). Strategies for promoting Polish identity in the northeastern United States. European Journal of Transformation Studies, 7(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà-Giménez, I., Dowling, N., Demir-Lira, Ö. E., Prieto, P., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2021). The predictive value of non-referential beat gestures: Early use in parent–child interactions predicts narrative abilities at 5 years of age. Child Development, 92, 2335–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, A. X. (2018). Migration and (Im)Mobility: Biographical experiences of polish migrants in Germany and Canada. Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Wojdon, J., & Skotnicka-Palka, M. (2021). Migracje z ziem polskich w XIX wieku we współczesnych podręcznikach do historii dla szkoły podstawowej. Migration Studies—Review of Polish Diaspora, 1(179), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaari, H., Fichman, S., Osher, P., Dorokhov, F., & Altman, C. (2024). Disfluencies as a window to macrostructure performance in the narrative of bilingual children. Ampersand, 13, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L. (2024). Constructivism learning theory. In Z. Kan (Ed.), The ECPH encyclopedia of psychology (pp. 311–313). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Zeng, H., Collins, P., & Warschauer, M. (2025). Exploring the direct and indirect relations of e-book narration and bilingual parent–child talk to children’s learning outcomes in EFL shared reading. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(3), 1134–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]