Abstract

Accountability in education is an important legal, professional and ethical consideration for all teachers in their practice, as it leads to deep reflections about educational outcomes for their students. However, in respect of inclusive education, a constellation of implementation barriers has led to difficulties with understanding and ensuring accountability of outcomes for students with special educational needs (SENs). Additionally, there is very little discussion or research about accountability in special and inclusive education (SIE) in many educational systems around the world. Drawing on extant literature, this paper explores the diverse disciplinary (e.g., policy making, organisational management) understandings of accountability to illuminate the field of educational accountability. It then proposes a model for inclusive education accountability—informed by human rights—that outlines the roles, obligations of policy makers, principals, teachers, and allied professionals to enable accountable practices and outcomes for students with SENs. The proposed model suggests accountability types and obligations at different levels that can be implemented in diverse practice contexts.

1. Introduction

One of the enduring issues facing inclusive schools across the globe is the notion of being accountable to students with special educational needs (SENs). Pincelli (2012) observed that post-school outcomes for students with disabilities have been stagnant for decades and that many were “…. not expected to be gainfully employed, live independently, be self-satisfied, and have a social life” (p. 3). Across the decades and within diverse published research, evidence suggests that there is frustration with limited or less than desired educational outcomes for students with special educational needs (SENs) in inclusive settings (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2019; Kuyini et al., 2022; Roberts, 2020). Researchers such as Li and Ruppar (2021), and Kuyini et al. (2022) have pointed to the failure of instruction, lack of resourcing, low teacher efficacy, and lack of policy vision as contributing to lower educational outcomes or negatively impacting educational outcomes of students with SENs. In most school jurisdictions, including in resource rich countries such as the USA, principals, teachers and parents may not have the agency to institute and implement accountability measures for all groups (Harr-Robins et al., 2015). This situation challenges schools to find ways to enact accountability mechanisms that are not limited to the high-stakes testing-based performance culture (Li & Ruppar, 2021), but equitable outcomes for students with SENs.

Educational accountability and accountability in education are not new concepts and have been the focus of research prior to the advent of inclusive education. In general, governments and schools have implemented policies of accountability for school systems that target specific aspects of school processes and outcomes, but with limited or no focus on inclusive education. In the last two decades, education researchers (e.g., Anderson, 2005; Brill et al., 2018; McLaughlin & Rhim, 2007; Roberts, 2020; Starbuck, 2020) have also written about educational accountability, its parameters and its limited use to potentially impact school outcomes, including for students with SENs. However, a thorough search of the literature shows that most accountability research is focused on international competitiveness to calibrate market competitiveness and school choice (Parcerisa et al., 2022). Acknowledging this trend, Brill et al. (2018) noted that motivation for change in national accountability for education systems is often strongly related to a country’s performance in international surveys such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Corroborating the above, Baird et al. (2016) concluded that policy changes are driven by such negative international competitive outcomes in many countries. These reports hardly talk about outcomes for students with SENs in special schools or inclusive settings. Undoubtedly, it is important to state that inclusive education, which rests on a human rights and social justice framework requires that outcomes for students with SENs must also be part of the focus of educational accountability. It is also important to expand research about how to strengthen accountability in relation to school experiences and outcomes for this cohort of students.

More than a decade ago the enthusiasm surrounding the notion of accountability and education appeared to suggest efforts would be made to drive research in this area to ensure that schools’ practices are adequate in relation to mechanisms for achieving better outcomes for all students. The USA, Australia and European countries began setting standards for educational participation and practices to ensure students with SENs achieve the same outcomes as their peers without special needs. For example, in Australia, the Disability Standards for Education 2005 were set up to clarify the obligations of education and training providers, ensuring that students with disability can access and participate equally in education (Australian Government, 2005, 2024). Similarly, The European Union’s Raising the Achievement of All Learners in Inclusive Education project (2014–2017) aimed to provide evidence of effective practice in raising achievement and building the capacity of schools and communities to include and support all learners (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2019). In the USA, the No child left behind policy is geared towards equitable outcomes in education for all students, leading to a range accountability approaches (Harr-Robins et al., 2015). And in England, the Department of Education set out a reform of the school accountability system, instituting better monitoring of standards, identifying and providing support to schools that need it and as a way to ensure all students receive quality education (Brill et al., 2018).

Aside from these examples, extant educational literature shows limited research on the subject and in many countries inclusive education implementation faces problems with accountability in relation to students with SENs. Many students with SENs still do not achieve at the same level as other students, and governments in most countries are challenged to push current practices in directions that will enable improved outcomes for such students (Kuyini et al., 2022; Roberts, 2020). In essence, it appears that despite policy and resourcing differences, many educational systems are struggling to implement practices that allow for efficient delivery of education to achieve equitable outcomes for all students in inclusive classrooms (Starbuck, 2020). The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016) acknowledged this failing and urged action by stating: “The high cost of school failure and inequity for individuals—and for society more widely—is increasingly being recognised across Europe. Raising the achievement of all learners is seen not just as a policy initiative, but as an ethical imperative” (p. 1). In line with this recognition, it is essential to explore the concept of accountability from different perspectives and to propose a model that can be adopted to reform and improve accountability practices in inclusive education, irrespective of the contexts and specific local policies.

2. Aim

This paper aims to analyse the nature of accountability frameworks from the perspective of fields such as public policy, organisational management, and education to inform accountability in inclusive education. It will also propose a model for improved accountability practices in inclusive education at the policy-making and school levels. This is an important undertaking to broaden educational professionals’ and researchers’ understanding of the facets and ingredients of accountability which can be deployed for policy re-framing, direct research, and teaching practices and enable better student outcomes.

2.1. Guiding Questions

- (1)

- What is the nature of accountability as articulated by different disciplinary perspectives (such as public policy, organisational management, and education)?

- (2)

- How can the diverse accountability perspectives be integrated into a model for inclusive education?

- (3)

- How can the model derived from the identified accountability perspectives be deployed in inclusive education settings?

2.2. Nature of Accountability as Articulated by Different Disciplinary Perspectives

The definition of accountability in the existing literature is diverse, reflecting theoretical, disciplinary and pragmatic application of the term in practice. The disciplinary perspectives captured in this paper include governance, organisational and management theory, and education. However, despite the seeming differences in definitions, they all point to measures for ensuring responsible use of resources and conscious staff performance that can lead to quality outcomes.

From the organisational and management theory perspectives, Hall et al. (2003) and McGrath and Whitty (2018) explain accountability as a mechanism or set of procedures that aim to ensure that the performance and operations of organisations and individuals are assessed and evaluated based on specific standards. Accountability denotes a readiness to take responsibility or to be accountable for decisions (Tamvada, 2020), a state or quality of being accountable (McGrath & Whitty, 2018). It is related to stewardship with liability for the creation and use of resources, and answerable for how the resources are used (Doyle et al., 2022). Being accountable implies an expectation of office holders to enact behaviours and provide an explanation of how they meet their duties and responsibilities, as an integral part of the legal, social and ethical requirements (McGrath & Whitty, 2018). Accountability plays a key role in organisational improvement, supporting organisations and individuals to carry out their responsibilities, obligations, and achieve target outcomes (Tamvada, 2020).

In the education literature, Brill et al. (2018) define accountability as “…a government’s mechanism for holding educational institutions to account for the delivery of high-quality education” (p. 1). School accountability can be understood in terms of holding educational systems responsible for the quality of their products, with respect to knowledge, skills and behaviours of students and graduates, like governments schools should equally be held to account for how they use the allocated government resources. In this regard, Roberts (2020) stated that accountability is a useful mechanism for creating powerful systems, imposing control, giving meaning to actions in ways that can have real impact on public endeavours such as education.

2.3. Forms and Parameters of Accountability

Emanating from the different definitions of accountability, several domains of accountability are discernible in the literature. In 1974, Levin proposed a framework for accountability, which included performance process, technical process, a political process and an institutional process (Levin, 1974). Brill et al. (2018), writing about impact of accountability on school curriculum, standards and engagement, identified four types of accountabilities—financial, integrity, individual and governance accountability. On their part, Parcerisa et al. (2022), in their work on form accountability employed in education systems across the world, suggested that there are two discernible main forms of accountability—performance-based and bureaucratic accountability. They stated that bureaucratic accountability is linked to governance, and in the field of education, it enables or reinforces performance and professional accountability. Performance accountability on the other hand reflects professional accountability as it emphasises meeting the ethical requirements of the profession by all staff.

In the management space, the literature identifies other forms of accountability such as vertical, horizontal and diagonal accountability (Carrington et al., 2008). Vertical accountability refers to the power of oversight held by the government or other governance entity to ensure individuals and institutions act in accordance with standards and their obligations. Horizontal accountability refers to staff and teams’ power to review the conduct of their peers to determine whether they are acting properly through evaluating or investigating compliance. Diagonal accountability, according to Carrington et al. (2008), refers to situations where stakeholders (in a vertical relationship with other organisations) use the horizontal-accountability mechanisms to exercise their power of oversight.

Furthering our understanding of accountability, with a focus on leadership and ethics, Dubnick (2006), outlined what he called “Orders of Accountability”, proposing four accountability types, namely the following:

- Performative accountability: arising in face-to-face relations involving direct and explicit acts of account giving.

- Regulatory accountability: the “control of conduct” characterised by how well one follows the guidance, rules and operating standards set by a resource giver, often on the basis of law and constrained and directed by the “code” and dominant rationale of the task environment.

- Managerial accountability: the use of accountability as a means to motivate and elicit purposive behaviour, such as better service and effectiveness, performance and quality in the production of goods and services.

- Embedded accountability: centred on the internalisation of the norms, values and expectations to a degree that the embedded sense of “being accountable” will guide behaviour without necessarily having to resort to the orders of performative, regulatory or managerial accountability.

Finally, Bovens (2006) conceptualised accountability within social relationships, which is a more comprehensive format. It encompasses the different accountability types already described above and by others in relation to staff behaviours and relations. In this framing, Bovens described accountability around four key dimensions or types, which are (a) The Forum, (b) The Actor, (c) The Conduct, and (d) The Obligation (See Table 1). These four platforms generate distinct accountability requirements. He then explains how accountability will occur based on seven constitutive elements (Table 2) as part of an evaluation framework for public accountability.

Table 1.

Types of accountability; based on (Bovens, 2006).

Table 2.

Accountability as a social relation (Bovens, 2006).

According to Bovens’s conceptualisations, organisations such as government departments and schools are forums (Table 1). In these forums, accountability can be political, legal, administrative, professional and social. In terms of their conduct, organisations can have financial, procedural and product accountability. In terms of actors, organisations have individual, collective, hierarchical and corporate accountability. In terms of obligations, organisations will have vertical, diagonal and horizontal accountability (Bovens, 2006). Summing up the obligations under this broader accountability framework, Bae (2018) noted that based on the political, social, legitimate, or moral mandate created for organisations, stakeholders are expected to commit to give an account of how their organisations meet defined standards. Actors have a relationship with the forum (Table 2), which is bound by some policy and/or regulation intended to achieve outcomes for beneficiaries. This applies to all stakeholders in inclusive education, where schools, principals and teachers should act for the benefit of students with SENs. Teachers have horizontal accountability to parents.

The above outlined constellation of perspectives on accountability, together with Bovens’s (2006) classifications could be useful for proposing a model that would support inclusive education accountability in diverse policy and practice contexts. Bovens’s framework is particularly important for inclusive education because it conceptualises accountability within the framework of social relationships. Since inclusive education is about different actors working together within diverse institutions of policy-making, implementation, and evaluation, Bovens’s framework is considered highly pertinent to a more comprehensive model of accountability.

2.4. Towards an Accountability Model for Inclusive Education

Although accountability has been a central feature for policy makers and organisations, its influence in education remains an area of limited interest for academics and researchers (Doyle et al., 2022). In educational systems, accountability could be understood from the work of Anderson (2005) and McLaughlin and Rhim (2007), who framed the parameters of accountability in two similar and yet different ways. Anderson (2005) stated that an accountability framework in education comprises three systems: (a) compliance with regulations, (b) adherence to professional norms, and (c) being results-driven. McLaughlin and Rhim (2007) on the other hand suggest that there are only two dominant forms of accountability—standard-driven accountability and market-driven accountability.

Kogan (1986) acknowledged Anderson’s (2005) idea of results-driven accountability by advocating for adherence to professional norms, and compliance with regulations. And Holloway et al. (2017), Verger et al. (2019) along with Bjerke et al. (2025) have promoted the notion of performance-based accountability and professional accountability, which are reported as the main forms of accountability across several educational systems in recent times, according to Parcerisa et al. (2022). Although these accountability approaches are being implemented more broadly in schools, they are criticised for lack of focus on achieving accountability for students with SENs. Confirming this criticism, Verger et al. (2019) noted that performative or test-based accountability, which has gained attention and manifests in practices of standardised testing, ranking and actions to enhance performance at the individual, organisational and system levels, largely excludes students with SENs. This exclusion is particularly important to highlight here because, from a human rights perspective, national governments and schools have accountability obligations to all students. Specifically, the human rights obligation, as per the UN Convention of the Rights of People with Disabilities, requires schools and teachers to be proactive in meeting their accountability obligations to students with SENs. In alignment with this obligation, Verger et al. (2019) made a point that performance and professional accountability ought to be enacted within school contexts, and the actors in schools (e.g., teachers, principals) are those who must give meaning inclusiveness. Therefore, schools should embrace and deploy performance and professional accountability to serve the access and outcomes rights or needs of students with SENs. Deriving from the above, performance and professional accountability, as promoted by researchers (Bjerke et al., 2025; Bovens, 2006; Holloway et al., 2017; Verger et al., 2019), ought be conceptualised in any proposed model as context-sensitive, recognising that due to diversity of national policies, school-level professional accountability will vary depending on prescriptions, leadership, resourcing, on-going professional development, and the expectations of teachers and other staff. However, the recognition of human rights as a cornerstone of accountability means that there could be near-similar policy prescriptions, which are pivotal to better outcomes in any model of inclusive education accountability.

2.5. Proposed Accountability Model for Inclusive Education

Slee (2018) defines inclusive education (IE) as the process of “… securing and guaranteeing the right of all children to access, presence, participation and success in their local regular school. Inclusive education calls upon neighbourhood schools to build their capacity to eliminate barriers to access, presence, participation, and achievement in order to be able to provide excellent educational experiences and outcomes for all children and young people” (p. 8). The philosophical basis of inclusion focuses on ethics, rights, access, participation, and equitable social and academic outcomes for all. IE promotes the idea that “every learner matters and matters equally” (UNESCO, 2017, p. 12), and incorporating the principles of equity into education policy is indispensable to ensuring accountability. This process requires placing firm value on the presence, participation and achievement of all learners, and evaluating evidence of barriers to access, participation and achievement (UNESCO, 2017). These inclusive prescriptions align with the ideas of Qvortrup and Qvortrup (2017) who see inclusion as consisting of three dimensions—different levels of inclusion, different types of social communities from which a child may be included or excluded, and different degrees of being included in and/or excluded.

This diversity of needs in inclusive schools imply that the different forms of accountability outlined in the model above are essential for achieving the goals of education. It is anticipated that governance, financial, vertical and horizontal accountability will operate at the policy-making level (department of education), the financing and resourcing level (department of finance) and the school level. However, in determining which accountability forms will be useful, guidance and consideration should be given to human rights, the underpinning philosophy of inclusive schools, the literature on accountability in education, and the teaching–learning processes that enable equitable outcomes for all students.

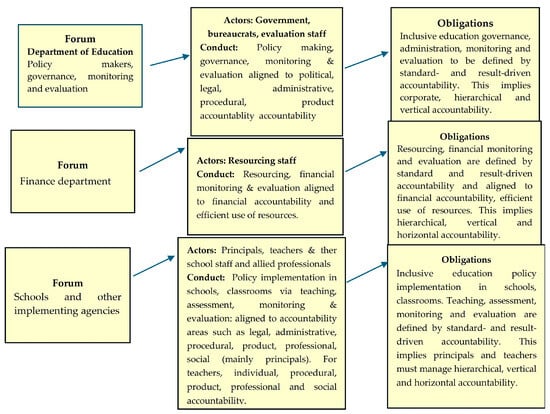

Considering this, the model of accountability proposed for Inclusive Education (Figure 1) will situate Bovens’s accountability categories at the apex/spine of the model and integrate the other principles—standard-driven and result-driven accountability (Anderson, 2005; McLaughlin & Rhim, 2007) and Dubnick’s (2006) “Orders of accountability” to encapsulate or highlight the richness of the accountability. In doing so accountability ranges from the policy level (department of education) to the school level. In essence, this kind of model will largely mirror a normative model of accountability, as it is based on propositions of what ought to be, focuses more on the client (student), the teachers, the school and the local authorities (Kogan, 1986). However, it incorporates the political dimension, focusing on policy-making and policy review which belong to the governance and the participative doctrines, such as responsive accountability and professional accountability. It will therefore be a useful and comprehensive guide across contexts (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Model for inclusive education accountability.

In the proposed model (Figure 1), Bovens’s accountability categories are essential in prescribing roles, responsibilities and obligations for agencies and stakeholders within policy documents, ensuring they are detailed and comprehensive enough to cover the scope and features of inclusive education as envisioned by national governments. At the upper level of Forums, two key state government institutions (the policy-making department, such as the department of education, and the finance department) are indispensable to accountability. The actors in the education department, as policy makers, and finance department, as the pedestal for resource allocation, have specific accountability obligations relating to governance and resourcing, which should be prescribed in the IE policy. These prescriptions should encompass the legal dimensions, including human rights, governance stipulations, resourcing and principles of standard-driven and result-driven accountability (Anderson, 2005; McLaughlin & Rhim, 2007).

The human rights obligations emanate from the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and other conventions such as UNCPR and UNCESCR. As a result, inclusive education policies in many countries reflect the right to education in terms of access, equity, respect for unique developmental needs, outcomes, and societal participation. In an accountability framework, these rights will become the basis for creating mechanisms for access, resourcing, teaching, and ensuring equitable outcomes in line with social justice principles (Kuyini et al., 2022). With these rights in mind, students with SENs should be able to access education, optimally actualising human rights and social justice. Social justice is about schools “providing an education which gives the less privileged access to the knowledge they need to succeed” (Whittaker, 2020, p. 157). Most inclusive education policies explicitly address recognitive and distributive justice; however, “… outcome justice requires vigilance and rigour on the part of policy makers, schools, and teachers.…, and if schools are to meet their social justice obligations, access rights should match or mirror outcome rights (Kuyini et al., 2022, p. 31). Therefore, embedding a strong human rights accountability dimensions in policies will support both result-driven accountability and standard-driven goals.

The model envisions that the departments of education, finance, and the schools, will have implementation, monitoring and evaluation obligations. These state departments will constitute the first tier of obligated agencies and schools will be the second tier (though frontline) of agencies in monitoring and evaluation. The Actors in each institution are the staff of these institutions, which include education policy makers, frontline implementors of inclusion such as principals and teachers. Their conduct and obligations are envisioned to be prescribed in policy and informed by standard- and/or result-driven accountability approaches which obligate all Actors to enact specific accountability functions. The Actors in each agency should be identified in policy, their roles, and the corresponding actions/behaviours (conduct) should be articulated, as will be their obligations to implement inclusive education. In this regard, policy makers, finance staff, school principals and teachers’ must act in defined ways to meet their administrative, legal, financial, procedural, professional and product obligations. And monitoring teams can identify roles, obligations and to assign blame or seek improvements.

At the school level, these proposals should work in practice by aligning the principles of standard and result-driven accountability principles with categories of accountability (Bovens, 2006) when implementing inclusive education. It is envisaged that in standard-driven accountability, a key feature for inclusive education is the legal requirement to uphold human rights of people with SENs to education. Underpinned by human rights, a standard-driven accountability requires schools to ensure that there is equal opportunity for students with SENs to access the curriculum in local policy and practice. It entails the application of administrative/governance, professional and other accountability approaches to ensure (1) adequate provision of resources in line with IEP-determined needs of students with SENs and (2) adapting instruction by principals and teachers, respectively. In meeting their individual, legal, governance/administrative, procedural and professional accountability obligations to students with SENs, schools will enable equity of educational outcomes, and social justice.

In a result-driven accountability approach, the focus on an inclusive education setting is geared towards access to learning environments and curriculum access via teachers’ adaptive instructional practices, a key ingredient to optimal educational outcomes. Achieving these goals requires accountability practices that enable achievement progression for all students towards set standards. Schleicher (2018) insists that the overarching accountability requirement for teachers, apart from the administrative is professional accountability. Schleicher (2018) emphasised that teachers’ accountability should involve a move towards ‘professional accountability’ which, […] refers to systems in which teachers are accountable not so much to administrative authorities but primarily to their fellow teachers and school principals… to other members of their profession….., also includes the kind of personal responsibility that teachers feel towards their peers, their students and their students’ parents (pp. 115–116). In this regard, teacher administrative and professional accountability will ensure staff access to teaching and teaching-related resources and their efficient deployment to facilitate learning.

In this proposed model, which mirrors existing practices in countries such as Finland, Japan and Singapore, the school level accountability will be school-wide, at multiple levels within the school, and allow student progress and outcomes to be tracked separately at multiple levels. Its implementation outcome could reflect the position of Theoharis et al. (2016) that tracking students by ability or achievement level is essential in an era of high-stakes accountability because it allows inclusion to be seen as a school-wide philosophy, driving inclusive service delivery, resulting in equity, social justice and improved achievement. In this way “…schools (can) demonstrate the reality that equity/inclusion as well as increased excellence can happen together” (Theoharis et al., 2016, p. 23).

2.6. Deploying the Model in Inclusive Education Systems

The implementation gap in relation to the inclusive education philosophy and practice on the one hand, and outcomes and accountability on the other, has been reported in many studies (e.g., Norwich, 2022; Slee & Tomlinson, 2018; Van Mieghem et al., 2020), highlighting issues with policy, structures and staff behaviour. The whole school approach to inclusive education (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010), the notion of school change (Fullan, 2007) and instructional adaptation should be integral to the process of implementing this accountability model. In deploying the model, school principals and staff should be guided by Roberts (2020)’s salient statement that accountability systems, as structures of meaning, signalling, incentive, and constraint, can cause changes in stakeholder behaviour.

Therefore, beginning at the policy level, the proposed model seeks to create meaning and signal Actors (staff) at all levels to what needs to change for accountability to take hold. It will also incentivise actors and outline parameters of constraints about behaviour within the organisational structures of inclusive schools. Local policy prescriptions should be communicated to staff by sending strong accountability signals about organisational structures and functions, which ought to change through the principals’ transformative leadership, culminating in enduring change in teachers’ perceptions and behaviour. Such changes in perceptions and behaviour, Choong et al. (2020) conclude, can affect self-efficacy through building trust in organisational systems and the leadership. According to these researchers, a well-designed and implemented accountability structures influence professional/personal accountability.

Based on the above, in employing the proposed model in schools, there is merit in being able isolate the different Forums (governance institutions, e.g., department of education or schools, support agencies such as health services) and various Actors (policy makers, teachers), and to assess their relationship and performance against key accountability obligations as outlined in Figure 1 and Table 1 and Table 2. Through enacting vertical and horizontal accountability, elements can be measured and enable provision of authentic evidence for pursuing policy amendments, direct policy change and craft mechanisms for holding identified actors responsible for failures and successes. These measures are foundational to success at the school level.

In many countries a lack of clearly defined roles and prescriptions within inclusive education policy has led to gaps in understanding the level of effectiveness of inclusive education practices (Kuyini et al., 2022; Das et al., 2013). Some literature (for example Armstrong et al., 2010; Sharma, 2020) laments the paradox of well-articulated policy statements that have no evidence in practice in schools and which inadvertently serve to exclude students with SENs with no real accountability (Harr-Robins et al., 2015). The model therefore highlights the legal and governance dimensions advocating that policy makers clearly articulate human rights and other statutory obligations, which schools must fulfil in principle and at the pragmatic level in classroom routines and instructional processes. As Rosenblatt (2017) observes, school accountability is the expectation that schools’ academic achievements are transparent and officially reported, resulting in performance assessment and consequent rewards or sanctions (p. 18). In utilising this approach, school change behaviours require that staff adhere to policy prescriptions about key roles, responsibilities, obligations of agencies and stakeholders’ groups.

From a practical standpoint schools should also employ evidence-based ideas when implementing accountability processes designed to improve achievements of students. The European Agency report 2019 called for national policies and policy makers to enable school leaders to raise achievement for all learners by “prioritising equitable high-quality education for all; encourage schools to innovate and develop a flexible curriculum to secure high-quality education for all; articulate the benefits of strong classroom practice among curricular and support teachers to take account of the diversity; enable specialist staff to support inclusive practices, and support further professional development; empower school leaders to operate with a wider set of monitoring and measurement tools that take account of valued outcomes for all learners” (pp. 16–17).

In their 2019 follow up study the agency emphasised that policy makers should achieve the following:

- Ensure that inclusive schools are well-resourced with support staff and staff from specialist settings/resource centres.

- Develop and deploy national annual plans for inclusive education that focus on curriculum development and pedagogy for all, which will allow for more informed monitoring and evaluation using both qualitative and quantitative data on the achievement of valued outcomes for all learners.

- Promote effective practice in teacher and support staff collaboration, since class teachers and support teachers recognise the value of high-quality collaboration to meet diverse needs (p. 21).

From a school quality perspective, the model will be seeking to inject quality into schools. UNESCO (2009) emphasises the reciprocity of inclusion, school access and quality and maintains that inclusion implies access to school environment and quality learning opportunities to produce quality outcomes. Therefore, access and quality are linked, mutually reinforcing and indispensable to better inclusive education outcome, which raises national standards of achievement (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2010). Since quality of inclusive school experiences and outcomes are important, Cheng’s (2003) Stages of Quality are useful at the level of school accountability. Cheng proposed that internal quality which relates to internal school performance (e.g., teaching and learning) along with interface quality accountability to the public (or stakeholders’ satisfaction) and future quality (demanding changes in the larger context systems) are all important. In this regard, school level accountability will include the internal and interface quality reflecting the idea that the measurable criteria for education quality concern not only test or exam scores, but the comprehensive process of inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes.

If educational accountability is to be pursued as per the proposed model, principals must demonstrate administrative and professional accountability by initiating and entrenching the essential characteristics of schools seeking improved performance of students with SENs. According to Harr-Robins et al. (2015), such characteristics include providing adequate staffing, facilitating enrolments, allocating more extra teaching time for specific subjects depending on IEP and encouraging collaborations between teaching teams and with parents. In this accountability framework, principals will set the tone for teacher accountability by exhibiting transformative leadership that enables instructional inclusion which can improve school achievement for all students. The European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education’s (2019) report emphasised that to increase achievement outcomes for all students, school level leadership teams should involve all stakeholders and (1) consider annual plans for inclusion as part of all school improvement programmes; (2) set up inclusion working groups that consider evidence of progress across key focus areas in raising achievement and improving inclusive education for all as such groups enable staff to collaborate in practical activities to meet the learners’ needs and improve pedagogy for all; (3) consider how teachers might work to improve collaboration and co-operative teaching in classrooms to raise achievement; (4) plan to increase the involvement of parents and families in ways that support raising learner achievement. Parents can be more fully involved in a school’s progress by including and raising the achievements of all learners (p. 22). The above are essential steps because school effectiveness is driven by strong principal leadership, effective instruction, high expectations of all students, positive school environments, enabling development of requisite skills, and monitoring progress, positive school culture, parental involvement, effective student learning (Sammons et al., 1995; Scheerens, 2013).

On their part, teachers should be an integral part of these school structures and process through which they demonstrate individual, procedural, product, professional and social accountability to collectively contribute to better school outcomes for all students. As noted by Schleicher (2018), teachers are accountable not so much to administrative authorities but primarily to their fellow teachers, their students and their students’ parents. Within the school’s ‘administrative accountability’ lies the use of students’ performance and school evaluation data to make decisions about school quality. The teachers’ effort and success are contingent on the principals setting high staff expectations to meeting established standards (Kuyini & Paterson, 2013) and meeting their own accountability obligations, which will increase the likelihood of teachers being able to provide effective instruction, support administrative decisions, liaise with parents and work with other professionals in meeting IEP requirements of students. The lack of resources and administrative support from principals erodes school quality, can undermine teachers’ sense of efficacy to fulfil their accountability obligations as it limits their ability to adapt instruction, persist in solving teaching–learning problems and provide other learning supports (Choong et al., 2020; Chow et al., 2023; Das et al., 2013; Opoku & Nketsia, 2025; Vanderpuye et al., 2020). Teachers are accountable in terms of curriculum access, instruction, appropriateness of assessments and ensuring all students are achieving optimally. The model therefore holds teachers accountable in relation to curriculum access, quality interaction, effective instructions, and meaningful achievement.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper explored the accountability concept and dimensions from different perspectives and presented a model which emphasises a human rights-based approach to accountability for students with SENs to achieve equitable school outcomes. It does not lean towards having a high-stakes to accountability in inclusive education, within which staff careers could be at stake. In high-stake systems, teachers’ careers are more directly connected to students’ performance, resulting in low performing schools risking closure. Neither does the model advocate a low-stake system of accountability, in which the administrative consequences of accountability for school actors are more symbolic (Brill et al., 2018). Instead, a middle ground is sought, combining elements of both approaches, which accentuates human rights, professionalism, and centres students’ needs, self-actualization and social justice at the core of teachers’ practices and ambitions.

The proposed model also eliminates extreme focus on a market-driven accountability approach which seems to dominate contemporary education practices in most countries (Brill et al., 2018; Parcerisa et al., 2022). The need to avoid a market approach is justified against the potential for it to perpetuate unequal access, provisions and outcomes for students with SENs. A market-driven approach is informed by the neo-liberal agenda of the centrality of markets, profits, and meritocracy. Therefore, its adoption as a format for accountability in the already unequal education systems around the world could perpetuate unequal access and outcomes (Kuyini et al., 2022).

The model deployment is contingent upon several factors and if designed and implemented successfully, can be a forceful driver of improvement. According to Roberts (2020), “The purposes of accountability systems are to hold responsible, incentivise and constrain, seek service improvement, control and signal to policy makers, build confidence and empowerment, and dialogue with parents and other stakeholders about educational performance” (p. 150). In these inclusive settings, accountability should also focus on building confidence and empowerment, and dialogue with parents and other stakeholders. Therefore, a strong principal leadership is required to institute and entrench accountability via effective instruction, positive school environments and culture, enabling parental involvement, professional development of staff, high expectations for all students and monitoring progress of students (Sammons et al., 1995).

The implementation of these methods of accountability is context-related as it may be efficient in certain contexts and disadvantageous in other educational settings. Context-specific measures are essential in the design of accountability as they acknowledge the diversity of educational contexts and specific population needs, as in the case in Columbia (Angarita et al., 2022). In essence, although the broad accountability model would apply to all contexts, specific areas of difference between countries and educational jurisdictions should be respected for efficiency of process and outcomes. Scholars within education reform and change such as Fullan (2007) recommend placing emphasis on local contextual realities to avoid the notion of “one-size-fits all”. In the policy implementation literature, standards are in-principle requirements, but with room for contextual variations to meet locally defined and expressed needs.

As widely acknowledged by many scholars and practitioners, no single accountability approach is always internationally effective (Gottlieb & Schneider, 2020); therefore, the proposed model should be considered an instrument to achieve better outcomes rather than an end itself. As a comprehensive concept, accountability backed by strong policy -making and implementation processes could be used to improve educational achievements of students with SENs, ensure value-for-money and raise the professional accountability of practitioners (Cochran-Smith et al., 2018). Accountability in inclusive education is about removing the barriers for students with SENs to be present, to participate and achieve (Ainscow, 2020), and unless these barriers are removed for all learners through personalised educational responses, equitable outcomes will be difficult to realise.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J. A. (2005). Accountability in education (IIEP education policy series). UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140986 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Angarita, M. M., Kamenopoulou, L., & Grech, S. (2022). Colombia and the struggle for social justice. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10193995/1/Kamenopoulou_Colombia%20and%20the%20struggle%20for%20social%20justice_chapter_AAM.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Armstrong, A. C., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2010). Inclusive education: International policy and practice. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S. (2018). Redesigning systems of school accountability: A multiple measures approach to accountability and support. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J., Johnson, S., Hopfenbeck, T. N., Isaacs, T., Sprague, T., Stobart, G., & Yu, G. (2016). On the supranational spell of PISA in policy. Educational Research, 58(2), 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, A. H., Dalland, C., Mausethagen, S., & Knudsmoen, H. (2025). Negotiating performative and professional accountability in inclusive mathematics education in Norway. International Journal of Educational Research, 129, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. (2006). Analysing and assessing public accountability. A conceptual framework. In European governance papers (Vol. 86, No. C-06-01). Eurogov. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, F., Grayson, H., & Kuhn, L. (2018). What impact does accountability have on curriculum, standards and engagement in education? A literature review. NFER. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, W., DeBuse, J., & Lee, H. J. (2008). The theory of governance and accountability. The University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180501185202id_/http://cprid.com/pdf/Course%20Material_political%20science/4-Governance_&_Accountability-Theory.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Cheng, C. Y. (2003). Quality assurance in education: Internal, interface, and future. Quality Assurance in Education, 11(4), 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y. O., Ng, L. P., Ai Na, S., & Tan, C. E. (2020). The role of teachers’ self-efficacy between trust and organisational citizenship behaviour among secondary school teachers. Personnel Review, 49(3), 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W. S. E., de Bruin, K., & Sharma, U. (2023). A scoping review of perceived support needs of teachers for implementing inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(13), 3321–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., Carney, M. C., Keefe, E. S., Burton, S., Chang, W. C., Fernandez, M. B., Miller, A. F., Sanchez, J. G., & Baker, M. (2018). Reclaiming accountability in teacher education. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A. K., Kuyini, A. B., & Desai, I. P. (2013). Inclusive education in india: Are the teachers prepared? International Journal of Special Education, 28(1), 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, M. W., Prantl, J., & Wood, M. J. (2022). Principles for responsibility sharing: Proximity, culpability, moral accountability, and capability. California Law Review, 110, 935–965. Available online: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/3775 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Dubnick, M. J. (2006, April 9–11). Orders of accountability. World Ethics Forum on Leadership, Ethics and Integrity in Public Life, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. (2016). Early school leaving and learners with disabilities and/or special educational needs: A review of the research evidence focusing on europe (A. Dyson, & G. Squires, Eds.). European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. (2019). Raising the achievement of all learners in inclusive education: Follow-up study (D. Watt, V. J. Donnelly, & A. Kefallinou, Eds.). European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (Ed.). (2007). Fundamental change: International handbook of educational change (Vol. 3). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, D., & Schneider, J. (2020). Educational accountability is out of step—Now more than ever. Phi Delta Kappan, 102(1), 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A. T., Frink, D. D., Ferris, G., Hochwarter, W., Kacmar, C., & Boven, M. (2003). Accountability in human resources management. In L. L. Neider, & C. Schriesheim (Eds.), New directions in human resource management (pp. 29–63). Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Harr-Robins, J., Song, M., Garet, M., & Danielson, L. (2015). School practices and accountability for students with disabilities (NCEE 2015-4006). National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U. S. Department of Education. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED553421 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Holloway, J., Sørensen, T. B., & Verger, A. (2017). Global perspectives on high-stakes teacher accountability policies: An introduction. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25(85), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M. (1986). Educational accountability: An analytical overview. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyini, A. B., Mangope, B., Major, T. E., Koyabe, B., & Spar, M. (2022). Students with intellectual and developmental disability in Botswana: How can accountability framework support better educational outcomes? MOSENODI: International Journal of the Educational Studies, 25(2), 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyini, A. B., & Paterson, D. (2013). School principals’ expectations of teachers to implement inclusive education and teachers’ understanding of those expectations in Australian schools. Special Education Perspectives, 22(2), 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, H. (1974). A conceptual framework for accountability in education. School Review, 82(3), 363–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Ruppar, A. (2021). Conceptualizing teacher agency for inclusive education: A systematic and international review. Teacher Education and Special Education, 44(1), 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S. K., & Whitty, S. J. (2018). Accountability and responsibility defined. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 11(3), 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M. J., & Rhim, L. M. (2007). Accountability frameworks and children with disabilities: A test of assumptions about improving public education for all students. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 54(1), 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwich, B. (2022). Research about inclusive education: Are the scope, reach and limits empirical and methodological and/or conceptual and evaluative? Frontiers in Education, 7, 937929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M. P., & Nketsia, W. (2025). Teachers’ access to professional development in inclusive education: An exploration of the ghanaian context. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcerisa, L., Verger, A., Martín, M. P., & Browes, N. (2022). Teacher autonomy in the age of performance-based accountability: A review based on teaching profession regulatory models (2017–2020). Education Policy Analysis Archives, 30, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincelli, M. (2012). Post-school outcomes for students with an intellectual disability [Unpublished Master’s thesis, St. John Fisher College]. Available online: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1278&context=education_ETD_masters (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Qvortrup, A., & Qvortrup, L. (2017). Inclusion: Dimensions of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(7), 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. (2020). Thinking about accountability, education and SEND. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(2), 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, Z. (2017). Personal accountability in education: Measure development and validation. Journal of Educational Adminsistration, 55(1), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammons, P., Hillman, J., & Mortimore, P. (1995). Key characteristics of effective schools: A review of school effectiveness research. Inst. of Education and Office for Standards in Education. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED389826 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Scheerens, J. (2013). What is effective schooling? A review of current thought and practice. Available online: https://research.utwente.nl/files/5142494/WhatisEffectiveSchoolingFINAL.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Schleicher, A. (2018). World class: How to build a 21st-century school system, strong performers and successful reformers in education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U. (2020). Inclusive education in the pacific: Challenges and opportunities. Prospects, 49, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, R. (2018). Defining the scope of inclusive education. In Paper commissioned for the 2020 global education monitoring report, inclusion and education. Available online: https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12799/5977/Defining%20the%20scope%20of%20inclusive%20education.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Slee, R., & Tomlinson, S. (2018). Inclusive education isn’t dead, it just smells funny. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, J. (2020). Should accountability for SEN/Disabilities be separate or embedded within a general accountability framework? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(2), 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tamvada, M. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and accountability: A new theoretical foundation for regulating CSR. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 5(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G., Causton, J., & Tracy-Bronson, C. P. (2016). Inclusive reform as a response to high-stakes pressure? Leading toward inclusion in the age of accountability. Teachers College Record, 118(14), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2017). A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002482/248254e.pd (accessed on 9 May 2009).

- Vanderpuye, I., Kwesi Obosu, G., & Nishimuko, M. (2020). Sustainability of inclusive education in Ghana: Teachers’ attitude, perception of resources needed and perception of possible impact on pupils. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(14), 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(6), 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A., Parcerisa, L., & Fontdevila, F. (2019). The growth and spread of large-scale assessments and test-based accountabilities: A political sociology of global education reforms. Educational Review, 71(1), 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, N. (2020). Education inspection framework 2019—Inspecting the substance of education. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(2), 156–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).