Teaching Justice-Oriented Picturebooks Through Collaborative Discussion and ‘Slow Looking’: Implications for Initial Teacher Education Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ITE and Picturebook Research

1.2. Theoretical Framing: ‘Slow Looking’ at Justice-Oriented Picturebooks

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context and Focus Participant

2.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Research Positionality and Limitations to the Study

3. Presentation of Themes and Findings

3.1. Theme 1: Entering Visual Storyworlds: The Significance of Teacher Guidance During Immersive and Collaborative Picturebook Experiences with Justice-Oriented Picturebooks

- Teacher:

- How can you tell [she’s a grandma] if you didn’t read this page or [know] that these are her grandkids?

- Jamaila:

- All the girls I can tell by their hair. They have the same thickness.

- Teacher:

- Mmm!

- Jamaila:

- And so, your mom usually tells you that families pass that, and they have the same skin color. I think.

- Teacher:

- Yeah. And the fact that they all have the same thickness of hair and color of hair, and their facial features are the same and their skin color is similar to hers, we can infer that they’re family. Now, is that how families always work?

- All Girls:

- No.

- Teacher:

- No, but that helps us understand.

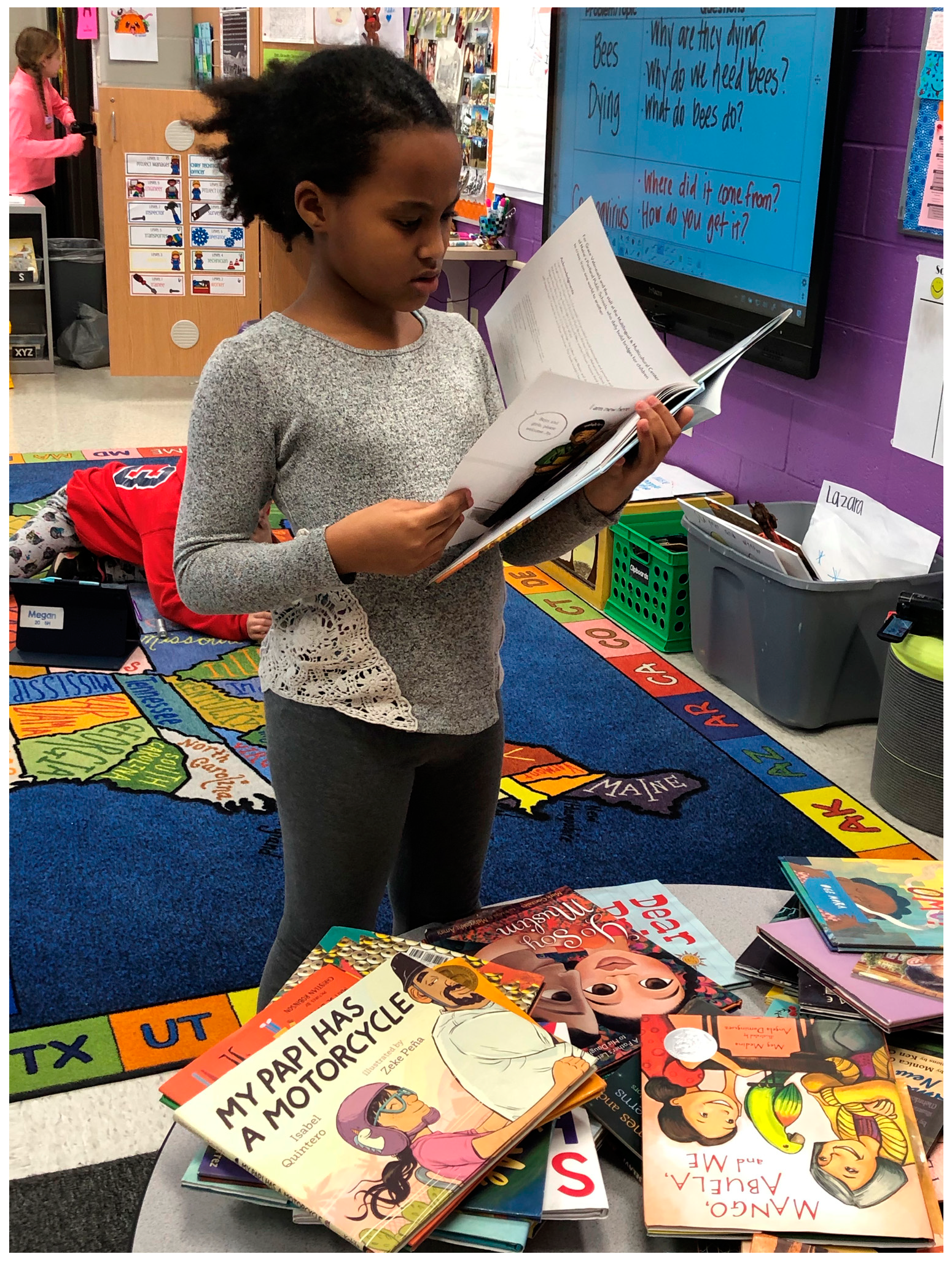

We’re trying to find pictures that are maybe a little bit different than our identity. Because then, we can look at the things that are a little bit harder to talk about, like where people live and the language they speak that’s different than our own and if their skin color is different than our own. Because we’re kind of taught sometimes to not talk about those things. It’s more respectful to not notice that. … It’s okay to notice that when you’re reading Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut (Barnes, 2017) [to] notice that people are African American in this book and [to] ask myself, “Well, why? Why did the author and illustrator include African American people in this book?” … Sometimes different people are left out of books, or different people are left out of stories … and that’s what we’re going to start asking ourselves, “Why do illustrations look like this? Why does the language sound like this?”

3.2. Theme Two: Exploring Visual Storyworlds: Engaging in ‘Slow Looking’ Across Modes of Meaning

- Jamaila:

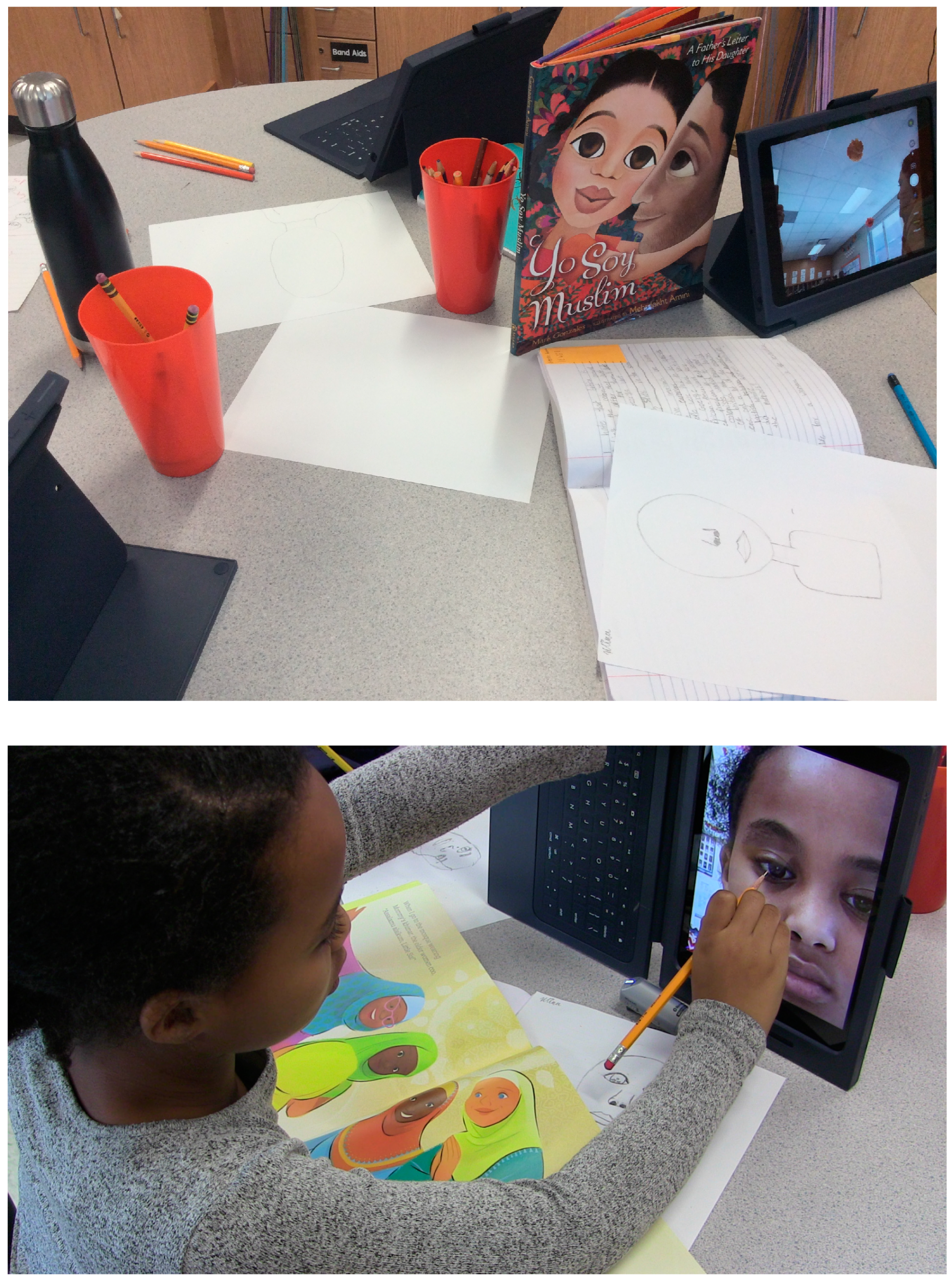

- Can I … do the nose like she did? [She touches the illustrator’s name on the cover of the book.]

- Teacher:

- Okay. Do you see your nose in that picture?

- Jamaila:

- Yeah.

- Teacher:

- Let’s see. [Whitney holds the book up next to a picture of Jamaila on her iPad.]

- Jamaila:

- Her nose [pointing to the daughter’s nose] is more bent down, as you can see. Mine is like this.

- Teacher:

- So, yours is maybe going to be a little more rounded than bent.

- Jamaila:

- Mmm hmm. …

- Teacher:

- Yeah. That’s such a good detail to think about. … We’ll put them [the book and the iPad] physically next to each other so you have one location to look. It’s hard to look at two places.

- Teacher:

- [Jamaila] started comparing her nose [that] she found on the cover.

- Jamaila:

- [nods head]

- Teacher:

- [holds up the book] An example that she thought was kind of similar to her. Would you agree?

- Jamaila:

- Mmm hmm. [nods head]

- Teacher:

- She used the illustrations as a mentor to help her draw herself. … She has the way another illustrator, another artist would show eyes, or the nose and lips. And here’s what I saw when I was walking past Jamaila. She is trying to look at that nose so closely and then she’s actually touching her face and looking at how her nose is made.

- Teacher:

- Does it look exactly like this? [Holds the book next to Jamaila’s face.] Okay, what do you think? Is that exactly Jamaila’s nose?

- Class:

- No. But it’s really close.

- Teacher:

- It’s close. And what did we notice about [the daughter’s] nose [that is] different from yours?

- Jamaila:

- [The daughter’s] is bigger and wider and mine is more like not as wide.

- Teacher:

- She realized, “Okay. I could draw it sort of like this, but I need to change it up just a bit”. So that it looks more like your nose. But to do that she looked at an artist and she also looked at herself.

Although the teacher describes how a picturebook could become an artistic mentor text, she challenged her fifth graders to move beyond conventional student interactions with a mentor text (i.e., imitation). She emphasized the need for a more complex, focused, and creative engagement that entails not only attending to artists’ styles and how they portray people’s physical features, such as skin shade, but to also consider how it can be refined and shifted to serve their own compositions. If Jamaila had duplicated the daughter’s nose in Yo Soy Muslim precisely, she would not have authentically represented her own identities in her self-portrait. Instead, Jamaila used her observations from ‘slow looking’ at the illustration, paired them with her observations from the digital photograph, and refined a design to serve her own self-portrait. What resulted from the ‘slow looking’ is a more demanding meaning-making process that not only deepened her reading and composing practice but also affirmed her identity and physical attributes.Teacher: So, today what you could do, and it might work, and it might not, but if you’re looking at yourself and you’re thinking, “Okay, how do I get my nose and lips just right? How do I get my skin shade just right?” Then maybe you could also look on our table for picturebooks and or an artist that has a similar style to you, a similar language to you, a similar nose to you that you want to use as a mentor, or you want to use as an example? … Jamaila used the cover of Yo Soy Muslim because she noticed that “Oh! That kind of looks like my nose … and maybe I need to change it a little bit.”

4. Implications for Teacher Education

- Offering access, exemplars of practice (such as those presented in this paper), and immersive experiences with justice-oriented picturebooks;

- Supporting conditions of reading that nurture slow looking at justice-oriented picturebooks;

- Nurturing the practice of reading justice-oriented picturebooks as picturebook makers who examine and collaboratively discuss the sociocultural features observed.

Ethics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arizpe, E. (2021). The state of the art in picturebook research from 2010 to 2020. Language Arts, 98(5), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizpe, E., Noble, K., & Styles, M. (Eds.). (2023). Children reading pictures: New contexts and approaches to picturebooks (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi-Moreno, L., & Quiñones, R. (2022). “Those books are not mirror books to me”: Learning from children about how to engage in identity work through picturebooks in a dual-language bilingual classroom. Journal of Children’s Literature, 48(1), 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D. (2017). Crown: An ode to the fresh cut. Agate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, K. (2017). Fundamentals of qualitative research: A practical guide. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R. S. (1990, March 5). Windows and mirrors: Children’s books and parallel cultures. California State University Reading Conference: 14th Annual Conference Proceedings (pp. 3–12), San Bernadino, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M., & Palacios, S. (2018). Marisol McDonald doesn’t match. Library Ideas, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Ching, S. H. (2005). Multicultural children’s literature as an instrument of power. Language Arts, 83(2), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, W. A. (1984). A handbook of social science methods, volume 2: Qualitative methods (R. B. Smith, & P. K. Manning, Eds.; 333p). Ballinger. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, N., & Blakeney-Williams, M. M. (2015). Picturebooks in teacher education: Eight teacher educators share their practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 40(3), 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, N., & Kelly-Ware, J. (2024). Using picturebooks to support student teachers to address complex social justice issues in early childhood education settings. Early Years, 45, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, N., & Short, K. G. (2022). Preservice teachers’ encounters with dual language picturebooks. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 47(7), 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeds, M., & Peterson, R. (1991). Teacher as curator: Learning to talk about literature. The Reading Teacher, 45(2), 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, J., & Simpson, A. (2024). Pre-service teacher knowledge of children’s literature and attitudes to Reading for Pleasure: An international comparative study. Literacy, 58(2), 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, T. T., Vlach, S. K., & Lammert, C. (2019). The role of children’s literature in cultivating preservice teachers as transformative intellectuals: A literature review. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 214–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R. P. (2017). Language arts lessons: Discussing racial trauma using visual thinking strategies. Language Arts, 94(5), 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, M. (2017). Yo Soy Muslim: A father’s letter to his daughter. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Hammett, R., & Bainbridge, J. (2009). Pre-service teachers explore cultural identity and ideology through picture books. Literacy, 43(3), 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikida, M., Chamberlain, K., Tily, S., Daly-Lesch, A., Warner, J. R., & Schallert, D. L. (2019). Reviewing how preservice teachers are prepared to teach reading processes: What the literature suggests and overlooks. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 177–195. [Google Scholar]

- Isadora, R. (2007). Yo, Jo! Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrim, J., & Moss, G. (2019). The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: International evidence from the OECD PISA study. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, E., Beneke, M. R., & Love, H. R. (2024). “So that I may hope to honor you”: Centering wholeness, agency, and brilliance in qualitative research with multiply marginalized young children. Educational Researcher, 53(4), 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, E., & Hartman, P. (2021). “It took us a long time to go here”: Creating space for young children’s transnationalism in an early writers’ workshop. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(4), 693–714. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M., Harmon, J., Hillburn-Arnold, M., & Wilburn, M. (2020). An investigation of color shifts in picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 46(1), 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M. A. (2014). Storyworld possible selves and the phenomenon of narrative immersion: Testing a new theoretical construct. Narrative, 22(1), 110–131. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Y. (2003). Just a minute!: A trickster tale and counting book. Chronicle Books. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, A. S. (2015). I’m new here. Charlesbridge Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo, S. (2018). Learning about and through picturebook artwork. The Reading Teacher, 71(5), 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, S. (2020). Slow looking: “reading picturebooks takes time”. Literacy, 54(1), 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, M. (2019). Between us and abuela: A family story from the border. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR). [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A., & Gonzalez, M. C. (2000). My very own room. Children’s Book Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, R. E., & Jackson, T. O. (2022). Who will remember?: Racial identity and civil rights literature for Black children at Freedom School. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 22(4), 481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, L. M. (1969). Towards a transactional theory of reading. Journal of Reading Behavior, 1(1), 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, F. (2024). The complex relationship of words and images in picturebooks. Journal of Visual Literacy, 43(3), 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K. G. (2018). What’s trending in children’s literature and why it matters. Language Arts, 95(5), 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., & Cremin, T. M. (2022). Responsible reading: Children’s literature and social justice. Education Sciences, 12(4), 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, L. R. (2008). Storytime: Young children’s literary understanding in the classroom. Teacher’s College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sipe, L. R. (2011). The art of the picturebook. In Handbook of research on children’s and young adult literature (pp. 238–252). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E. E. (2016). Research & policy: Stories still matter: Rethinking the role of diverse children’s literature today. Language Arts, 94(2), 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Tishman, S. (2017). Slow looking: The art and practice of learning through observation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy, M. (2019). Pre-service teachers as authors and elementary school students as readers of self-published picturebooks: A formative experiment. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(6), 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, M. (2020). Pre-service teachers as creators and students as viewers of children’s literature-related digital stories: A formative experiment. International Journal of Progressive Education, 16(6), 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, A., Minton, S., & Martinez, M. (2015). Child illustrators: Making meaning through visual art in picture books. The Reading Teacher, 69(3), 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissman, K. K. (2022). Crossing thresholds and becoming vitally attached: Bringing an affective lens to reading culturally sustaining picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 48(2), 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zambo, D. (2005). Using the picture book Thank You, Mr. Falker to understand struggling readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(6), 502–512. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, A. (2022). (Re)Animating children’s aesthetic experiences with/through justice-oriented literature: Critically curating picturebooks as sociopolitical art. The Reading Teacher, 76(1), 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, A. (2023). Deepening student engagement with diverse picturebooks: Powerful classroom practices for elementary teachers (C. Fleisher, Ed.). Principles in Practice Series. National Council of Teachers of English. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, A., Franks, D., & Moss, D. (2017). Awakening socially just mindsets through visual thinking strategies and diverse picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 43(2), 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, A., González Ybarra, A., & Adu-Gyamfi, M. (2024). Deepening explorations of racial and linguistic representation in picturebooks through critical translingual literacies. The Reading Teacher: Special Issue on Emancipatory Pro-Black, Latinx and Indigenous Reading Research and Teaching, 78(5), 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, A., Kleekamp, M., Rodriguez, N., & Crisp, T. (2023). Children’s literature in K-12 and higher education settings. In The Handbook of research on teaching the english language arts. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zapata, A.; Reid, S.; Adu-Gyamfi, M. Teaching Justice-Oriented Picturebooks Through Collaborative Discussion and ‘Slow Looking’: Implications for Initial Teacher Education Settings. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040447

Zapata A, Reid S, Adu-Gyamfi M. Teaching Justice-Oriented Picturebooks Through Collaborative Discussion and ‘Slow Looking’: Implications for Initial Teacher Education Settings. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040447

Chicago/Turabian StyleZapata, Angie, Sarah Reid, and Mary Adu-Gyamfi. 2025. "Teaching Justice-Oriented Picturebooks Through Collaborative Discussion and ‘Slow Looking’: Implications for Initial Teacher Education Settings" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040447

APA StyleZapata, A., Reid, S., & Adu-Gyamfi, M. (2025). Teaching Justice-Oriented Picturebooks Through Collaborative Discussion and ‘Slow Looking’: Implications for Initial Teacher Education Settings. Education Sciences, 15(4), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040447